Abstract

Background

Trypanosoma cruzi is a zoonotic pathogen of increasing relevance in the USA, with a growing number of autochthonous cases identified in recent years. The identification of parasite genotypes is key to understanding transmission cycles and their dynamics and consequently human infection. Natural T. cruzi infection is present in captive nonhuman primate colonies in the southern USA.

Methods

We investigated T. cruzi genetic diversity through a metabarcoding and next-generation sequencing approach of the mini-exon gene to characterize the parasite genotypes circulating in nonhuman primates in southern Louisiana.

Results

We confirmed the presence of T. cruzi in multiple tissues of 12 seropositive animals, including heart, liver, spleen and gut. The TcI discrete typing unit (DTU) predominated in these hosts, and specifically TcIa, but we also detected two cases of coinfections with TcVI and TcIV parasites, unambiguously confirming the circulation of TcVI in the USA. Multiple mini-exon haplotypes were identified in each host, ranging from 6 to 11.

Conclusions

The observation of multiple T. cruzi sequence haplotypes in each nonhuman primate indicates possible multiclonal infections. These data suggest the participation of these nonhuman primates in local parasite transmission cycles and highlight the value of these naturally infected animals for the study of human Chagas disease.

Keywords: Chagas disease, epidemiology, genotyping, transmission, zoonosis

Introduction

Chagas disease is a neglected zoonosis caused by the protozoan parasite Trypanosoma cruzi. It represents a major public health problem in the Americas, with health care costs of more than US$24 billion.1 In the USA there are an estimated 300 000 human cases, including a growing number of locally acquired cases.2 Autochthonous transmission is thus of growing concern and preliminary analysis of triatomine blood sources suggest a significant rate of vector–human contacts.3–5 Nonetheless, the risk of human infection remains poorly understood in the southern USA, as well as the epidemiology of the disease.

The identification of parasite genotypes in a given region or epidemiological setting is key to understanding overall parasite transmission cycles and their dynamics and consequently human infection.6 Indeed, the genetic diversity of T. cruzi is believed to be associated with a comparable extensive biological diversity, and current hypotheses consider that there are associations among parasite genotypes, vertebrate hosts and transmission cycles, as well as possibly with disease progression in mammalian hosts.6,7

T. cruzi high genetic diversity has led to its subdivision into seven main lineages, referred to as discrete typing units (DTUs) TcI–TcVI and Tcbat.8 This genetic structure is conserved across the entire American continent and appears very stable over time.9,10 Most of the current understanding of T. cruzi genetic structure has been derived from two kinds of studies: extensive population genetic studies using a diversity of genetic markers, including multilocus sequence typing, microsatellites, gene sequence analysis and single-nucleotide polymorphisms, applied to isolated parasite strains and rapid genotyping using polymerase chain reaction (PCR), sometimes coupled to sequencing, applied to direct parasite genotyping in biological samples. The first approach suffers from an important bias from the initial parasite isolation step, as only clones able to grow efficiently in axenic culture media are studied. The second one reflects an attempt to overcome this bias by directly analyzing parasite DNA in samples, but it mostly detects the dominant clone/sequence, so infections with multiple parasite strains are often overlooked.

These technical limitations have considerably hindered our understanding of the geographic distribution of T. cruzi DTUs and the effective identification of the full range of parasite diversity in vectors and hosts. Indeed, so far, most studies have only reported TcI and TcIV in the southern USA,11 but more recent work suggests more extensive parasite diversity in the region. For example, infection with parasites from the group of TcII-TcV-TcVI was detected at high frequency in autochthonous human cases from Texas, although further discrimination of DTUs was not reported,12 and TcII was detected in rodents from Louisiana.13 The development of a metabarcoding approach based on next-generation sequencing further expanded the diversity of T. cruzi parasites detected in these rodents, and TcV and TcVI were also reported for the first time in these hosts in the USA (Pronovost et al., manuscript submitted).

T. cruzi infections have also been identified in multiple nonhuman primate colonies in the USA, where triatomine bugs and zoonotic transmission cycles are known to occur. In particular, the overall prevalence of infection was 1.6% at the Tulane National Primate Research Center (TNPRC) and reached 3.1% in pig-tailed macaques.14 These naturally infected nonhuman primates represent highly valuable models and both acute and chronic stages of Chagas disease have been studied in rhesus macaques and baboons.15 In an effort to further characterize the parasite genotypes circulating in the region, here we investigated T. cruzi genetic diversity in a subset of these animals previously identified as seropositive through a metabarcoding and next-generation sequencing approach.

Materials and methods

Sample collection and T. cruzi diagnostic

We used archived formalin-fixed tissues from 12 nonhuman primates corresponding to Macaca mulatta (n=7 Indian ancestry and 1 Chinese ancestry), Macaca nemestrina (n=2) and Papio spp. (n=2) that had been used in various unrelated studies before and had screened seropositive for T. cruzi using a rapid dipstick assay.14 All macaques had been born and raised at the TNPRC, Covington, LA, USA, while baboons were born at Ohio State University and at the Washington National Primate Center, respectively, and arrived at the TNPRC as adults. DNA was extracted from five to seven sections of 5 μm from heart, spleen, liver and gut samples using the qiaAMP DNA FFPE extraction kit (Qiagen, Venlo, The Netherlands) following the instructions of the manufacturer.16 The presence of T. cruzi DNA in tissue samples was assessed by PCR as reported before using satellite DNA as the target13,17 due to its high copy number.

Mini-exon genotyping PCR

The hypervariable intergenic region of the mini-exon gene or spliced leader (SL) RNA gene promoter18 was used for parasite genotyping. We initially used PCR primers reported by Souto et al.19 and by Fernandes et al.,20 which allow for the differentiation of some of the DTU-based differences in amplicon sizes.

Further genotyping was performed using newly designed PCR primers amplifying the nearly full length of the mini-exon gene (450–500 bp depending on the DTU). These are TcCH: 5′-CCCCCCTCCCAGGCCACACTGGG-3′ and TrypME3: 5′-TTCTGTACTATATTGGTACGCGAAG-3′. PCRs were performed in 25-μL mixtures containing 12.5 μL of an Apex 2.0 Hot Start Master Mix, 1 μL of each primer (10 μM), 6.5 μL of molecular grade water and 100 ng/μL of template DNA. DNA samples purified from cultured T. cruzi reference strains H1Mx (TcI), Esmeraldo (TcII) and CAN III (TcIV) were used as positive controls, as well as a negative control with no template DNA. Amplifications were performed with a C1000 Touch Thermal Cycler with the following cycling conditions: an initial denaturation step of 5 min at 95°C, followed by 45 cycles of 30 s at 94°C, 30 s at 65°C and 30 s at 72°C, followed by a final extension step of 10 min at 72°C. PCR products were separated on a 2.5% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide and analyzed using a Bio-Rad Gel Doc XR+ with Image Lab software (BioRad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA).

Next-generation sequencing and analysis

The PCR products from each sample were purified using a PureLink Quick PCR Purification Kit (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA). Following end-repair and indexing, libraries were prepared and sequenced on a MiSeq sequencing platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). A total of 18 000–86 000 reads were obtained from each primate tissue. Reads were mapped to T. cruzi mini-exon reference sequences representing all parasite DTUs with the software package Geneious version 11. To assess sequence diversity, sequences that matched each reference were trimmed of PCR primer sequences and realigned using the Muscle subroutine implemented in Geneious version 11. The FreeBayes SNP/variant tool21 was used to distinguish sequence variants from sequencing artifacts. Low-abundance sequences (<0.5% of reads) were excluded from further analysis. Novel sequences were deposited in the Genbank database under accession numbers MH629763–MH629841. New Muscle sequence alignments were performed with all newly acquired nonhuman primate T. cruzi haplotypes and additional sequences from reference strains for a precise identification of DTUs (TcI: Pla20cl4 [accession EF576836], Tev91cl1 [EF576832], FcHcl1 [KF220693], Raccoon70 [EF576837], SilvioX10 [CP015667], P/209cl1 [EF576816], P/217cl1 [EF576940]; TcII: Tu18 [AY367125], Esmeraldo [ANOX01015751]; TcIII: M5631 [AY367126], M6241 [AF050522]; TcIV: 92122102r [AY367124], CanIII [AY367123], MT4167 [AF050523]; TcV: MN [AY367128], SC43 [AY367127]; TcVI: CL [U57984], VSC [FJ463159]; Tcbat: TCC949cl3 [KT305873], TCC2477cl1 [KT305884]). We also used parasite sequences from rodents of the New Orleans, LA, area for further comparison (MH316707, MH316663, MH316731, MH316748, MH316711 and MH316668). Separate alignments were elaborated for the analysis of TcI and its subgroups (TcIa–e), TcIV and the TcII-TcV-TcVI DTUs (respectively) to avoid poor alignments from high sequence divergence and to improve comparisons of closely related sequences. Phylogenetic trees based on maximum likelihood were constructed using the Phylogeny.fr suite of tools.22 TCS haplotype networks23 were constructed in PopART to further assess sequence diversity among TcI haplotypes.

Results

T. cruzi diagnostic

Nonhuman primate DNA samples were first tested for the presence of T. cruzi DNA and 11/12 animals were positive for T. cruzi in at least one of the tissues tested (Table 1), corresponding to M. mulatta (n=6 Indian ancestry and 1 Chinese ancestry), M. nemestrina (n=2) and Papio spp. (n=2). Parasite DNA was detected in the liver of 9/11 (82%) non-human primates, in the heart of 7/9 (78%), in the gut of 9/12 (75%) and in the spleen of 4/12 (33%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

T. cruzi PCR diagnostic in nonhuman primate tissues

| Identification no. | Species | Sex | Tissue | T. cruzi |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CM59 | Chinese Macaca mulatta | M | Heart | Positive |

| Spleen | Positive | |||

| Liver | Positive | |||

| Gut | Positive | |||

| BJ49 | Indian M. mulatta | M | Spleen | Negative |

| Liver | Positive | |||

| Gut | Positive | |||

| CC19 | Indian M. mulatta | F | Spleen | Positive |

| Liver | Positive | |||

| Gut | Positive | |||

| CD02 | Indian M. mulatta | F | Heart | Negative |

| Spleen | Negative | |||

| Liver | Negative | |||

| Gut | Negative | |||

| EB28 | Indian M. mulatta | F | Heart | Positive |

| Spleen | Negative | |||

| Liver | Positive | |||

| Gut | Positive | |||

| EM04 | Indian M. mulatta | M | Heart | Positive |

| Spleen | Negative | |||

| Liver | Positive | |||

| Gut | Positive | |||

| T874 | Indian M. mulatta | F | Heart | Positive |

| Spleen | Negative | |||

| Liver | Positive | |||

| Gut | Positive | |||

| V830 | Indian M. mulatta | F | Heart | Positive |

| Spleen | Negative | |||

| Liver | Positive | |||

| Gut | Positive | |||

| CH77 | Macaca nemestrina | F | Heart | Negative |

| Spleen | Negative | |||

| Liver | Negative | |||

| Gut | Positive | |||

| ED93 | M. nemestrina | F | Heart | Positive |

| Spleen | Positive | |||

| Liver | Positive | |||

| Gut | Negative | |||

| BI97 | Papio spp. | F | Heart | Positive |

| Spleen | Positive | |||

| Liver | Positive | |||

| Gut | Negative | |||

| AN52 | Papio spp. | F | Spleen | Negative |

| Gut | Positive |

T. cruzi genotyping

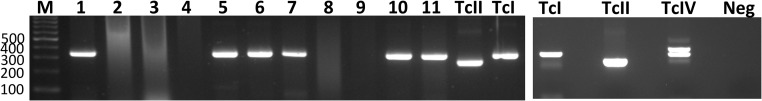

PCR genotyping using both Fernandes and Souto primers was successful in 11/29 T. cruzi–positive samples, corresponding to six animals. In all cases it indicated the presence of TcI parasites in all samples and no other DTUs were detected (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

T. cruzi PCR genotyping in nonhuman primates. A partial T. cruzi mini-exon sequence was PCR amplified using previously described primers19 to provide amplicons of different sizes for TcI and non-TcI parasite DTUs. Lane M: molecular weight marker, with sequence length indicated on the left (bp); lanes 1–11: nonhuman primate samples; lanes TcII, TcI and TcIV: control strains. Samples from lanes 1, 5, 6, 7, 10 and 11 presented bands corresponding to TcI, while samples in lanes 2, 3, 4, 8 and 9 could not be genotyped successfully.

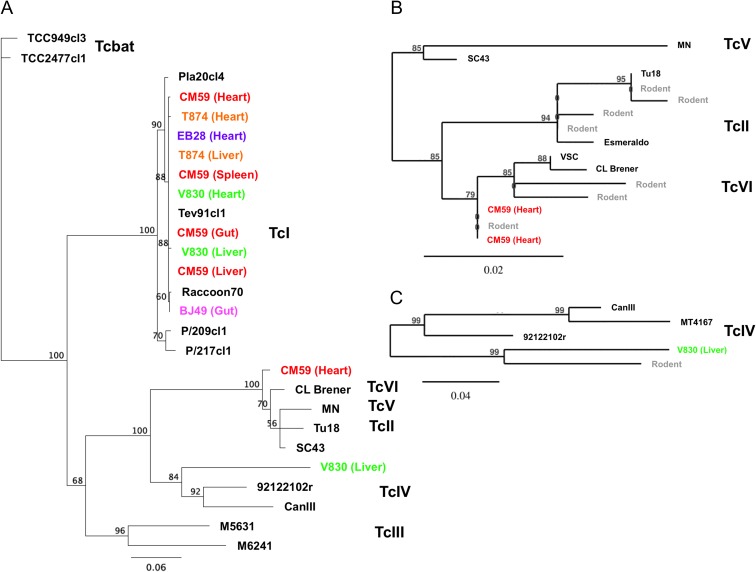

Because direct PCR genotyping is biased by only detecting the dominant parasite haplotype present in samples, we also amplified a longer fragment (about 500 bp) of the mini-exon gene using newly designed primers and performed deep sequencing to detect sequence diversity in a subset of samples. Multiple mini-exon haplotypes were identified in each sample, ranging from 6 to 11, corresponding to an average of 7.2±0.4 per sample. Haplotypes varied in abundance, with frequencies ranging from 91.6 to 0.5%, but a dominant haplotype representing >48% of sequences was detected in each sample. Phylogenetic analysis of the mini-exon sequences confirmed the extensive presence of TcI haplotypes in all samples (Figure 2). However, coinfections with TcVI and TcIV were detected in two animals, with two and one haplotypes, respectively. The two TcVI haplotypes were detected in the heart of a M. mulatta, and were closely related, but not identical, to TcVI haplotypes observed in rodents from the New Orleans area (Pronovost et al., manuscript submitted). The TcIV haplotype was detected in the liver of another M. mulatta, and it similarly clustered with a TcIV haplotype previously reported in rodents from the New Orleans area. These were more closely related to a North American reference sequence than with South American ones (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic analysis of T. cruzi mini-exon sequences. Mini-exon sequences from nonhuman primate tissue samples (color coded by individuals) were compared with sequences from reference T. cruzi strains (black labels) as well as with T. cruzi sequences previously detected in rodent samples from New Orleans, LA (gray labels) using maximum likelihood. Because of the large number of TcI haplotypes, only the most abundant sequence per animal/tissue is shown. Numbers on nodes indicate bootstrap support. (A) Global analysis including all seven T. cruzi DTUs (TcI–TcVI and Tcbat). (B) Analysis of TcII, TcV and TcVI DTUs. (C) Analysis of TcIV DTU. This figure is available in black and white in print and in color at Transactions online.

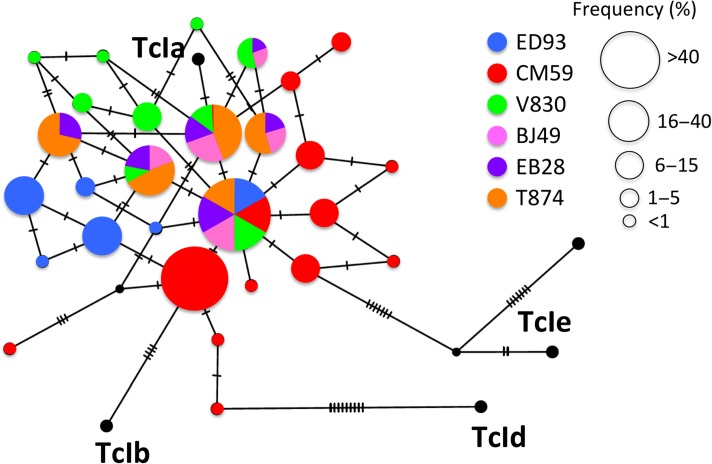

We further analyzed TcI sequence diversity through a TCS network. There were 5–11 TcI haplotypes per sample and all the sequences clustered with TcIa reference sequences, while TcIb, TcId and TcIe were not detected (Figure 3). While a few haplotypes were shared among animals, most others were only detected in different individuals, indicating that they had been infected with different mixtures of parasite. For the three animals in which we were able to obtain sequences from different tissues, most haplotypes were shared among tissues, but a few were also tissue specific (5/7 shared haplotypes among tissues in M. mulatta CM59, 5/5 in T874 and 1/6 in V830).

Figure 3.

Haplotype network of TcI diversity in nonhuman primates. Mini-exon sequences from individual monkeys (color coded) were used to construct a TCS network. Nodes represent distinct sequence haplotypes, with their size proportional to their frequency. Ticks on the edges linking nodes indicate the number of mutations from one haplotype to the next. This figure is available in black and white in print and in color at Transactions online.

Discussion

T. cruzi has been known for a long time to present extensive genetic diversity, which has led to its subdivision into multiple DTUs. While it is assumed that this diversity can be associated with the specific geographic distribution of DTUs, distinct transmission cycles and biological properties,6,8 strong evidence is still lacking to support such associations. Parasite genotyping in diverse samples from vertebrate hosts and triatomine vectors provides a key tool to assess these potential associations, and we report here on parasite genotypes present in naturally infected nonhuman primates from a large colony in southern Louisiana in the USA.

As observed before in samples from rodents (Pronovost et al., manuscript submitted) and triatomines,24 our approach based on metabarcoding and next-generation sequencing was much more sensitive to detect a great diversity of parasite haplotypes than direct electrophoresis of PCR products, which only detected the dominant TcI parasites. Direct molecular genotyping from biological samples provides a more complete description of parasite diversity than genotyping from isolated parasites, which is biased by the initial culture selection of parasites. In addition, next-generation sequencing further overcomes the limitation of detecting the dominant haplotype by PCR and conventional Sanger sequencing and provides detailed information on parasite diversity. Thus we were able to not only assess TcI diversity in these samples, but also to detect two cases of coinfections with TcVI and TcIV parasites. While the circulation of TcI and TcIV has been extensively described in the USA, including infections that have been documented in nonhuman primates,25,26 our results unambiguously confirmed the presence of TcVI, detected for the first time in the USA in rodents from the New Orleans area (Pronovost et al., manuscript submitted). Similarly, the initial genotyping of T. cruzi from a large cohort of autochthonous human cases from Texas indicated a high frequency of infections with parasites from the TcII-TcV-TcVI group, although the exact DTU assignment could not be resolved due to insufficient sequence data.12 TcVI and TcV DTUs have often been described in human infections in the southern cone countries, but more rarely in Ecuador and Colombia.27,28 The presence of TcVI in the USA raises the question of why other studies failed to detect it in vertebrate hosts and vectors,11,29,30 and a likely explanation is a bias from previous genotyping approaches. While TcVI haplotypes we identified in nonhuman primates clearly clustered with the TcVI reference sequences from Brazil, they also showed marked differences, suggesting some degree of local differentiation, in agreement with a long evolutionary history of TcVI in the USA. This is similar to what has been observed for TcIV strains, which appear to present significant geographic differentiation between North and South America.31

Importantly, the sequence haplotypes of TcI, TcIV and TcVI we observed in nonhuman primates were closely related, but not identical, to haplotypes previously detected in rodents from southern Louisiana. Since most of these animals were born and raised in Louisiana (except the baboons, which came from Ohio and Washington), it is most likely that infection occurred locally. These results suggest on the one hand that there may be some degree of spatial structuration of T. cruzi strains in the region and on the other hand that these nonhuman primates and rodents may be involved in a common parasite transmission cycle. However, TcId has been reported in rodents, but not in nonhuman primates so far. Further studies in additional hosts and vectors should help reconstruct more precise transmission cycles.

The observation of multiple T. cruzi sequence haplotypes in each nonhuman primate sample is also of interest, as it may indicate multiclonal infections. As mentioned before, the mini-exon gene is a multicopy sequence, so some diversity may be due to paralogous variants within a single parasite clone (Pronovost et al., manuscript submitted).24 In the case of the detection of infections with TcI+TcVI and TcI+TcIV in nonhuman primates, coinfections are the most likely interpretation. The number of clones present when only TcI was detected is more difficult to establish. Compared with the diversity of haplotypes detected before in rodents, which covered TcI, TcII, TcIV, TcV and TcVI DTUs, and up to 32 haplotypes per individual (Pronovost et al., manuscript submitted), parasite diversity seems to be lower in nonhuman primates, in which an average of 7.2 haplotypes was detected. Taking into account the widespread presence of T. cruzi infection in rodents from different areas in the southern USA (76% in urban Louisiana,13 11% in rural Louisiana [Herrera and Blum, in preparation], 3.8–18% in Texas32,33) and the low prevalence of infection reported before in these nonhuman primates (0.5%),14 we can hypothesize that multiple infections are frequent in rodents, while they are much less frequent in nonhuman primates. This in turn suggests different roles for these hosts in parasite transmission cycles, with rodents being a more central host contributing to parasite circulation and nonhuman primates being a spillover host. This would contrast with observations at another primate center in Texas, where infection with T. cruzi was not detected in rodents.34

Taken together, these data shed light on the diversity of T. cruzi circulating in the southern USA and warrant further exploration of this diversity in other hosts and vectors, which can lead to a better understanding of T. cruzi epidemiology and transmission cycles in the region. They also highlight the value of these naturally infected animals for the study of human Chagas disease.

Authors’ contributions

CH and ED conceived the study and designed the study protocol. PD and KPF provided animal data and samples. AM, ED and CH carried out the molecular analysis and interpretation of the data. All authors drafted the manuscript and critically revised the manuscript for intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. CH and ED are guarantors of the paper.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Dawn Wesson and Dr. Samuel Jameson (Department of Tropical Medicine, Tulane University, New Orleans, LA, USA) for their technical assistance.

Funding

This work was funded in part by the Louisiana Board of Regents through the Board of Regents Support Fund [contract number LESASF (2018-21)-RD-A-19] to ED, the Carol Lavin Bernick Faculty Grant Program-Tulane University and to CH, the Tulane National Primate Center-TNPRC Base Grant P51 OD010425 through the Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (ORIP) of National Institutes of Health-NIH, and National Institutes of Health-NIH grant U42 OD024282.

Competing interest

None declared.

Ethical approval

Not required.

References

- 1. Lee BY, Bacon KM, Bottazzi ME, et al. Global economic burden of Chagas disease: a computational simulation model. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13(4):342–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Montgomery SP, Parise ME, Dotson EM, et al. What do we know about Chagas disease in the United States? Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2016;95(6):1225–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Klotz SA, Schmidt JO, Dorn PL, et al. Free-roaming kissing bugs, vectors of Chagas disease, feed often on humans in the Southwest. Am J Med. 2014;127(5):421–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Waleckx E, Suarez J, Richards B, et al. Triatoma sanguisuga blood meals and potential for Chagas disease, Louisiana, USA. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20(12):2141–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gorchakov R, Trosclair LP, Wozniak EJ, et al. Trypanosoma cruzi infection prevalence and bloodmeal analysis in triatomine vectors of Chagas disease from rural peridomestic locations in Texas, 2013–2014. J Med Entomol. 2016;53(4):911–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zingales B. Trypanosoma cruzi genetic diversity: something new for something known about Chagas disease manifestations, serodiagnosis and drug sensitivity. Acta Trop. 2017;184:38–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Messenger LA, Miles MA, Bern C. Between a bug and a hard place: Trypanosoma cruzi genetic diversity and the clinical outcomes of Chagas disease. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2015;13(8):995–1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zingales B, Andrade SG, Briones MR, et al. A new consensus for Trypanosoma cruzi intraspecific nomenclature: second revision meeting recommends TcI to TcVI. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2009;104(7):1051–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tibayrenc M, Ayala FJ. The population genetics of Trypanosoma cruzi revisited in the light of the predominant clonal evolution model. Acta Trop. 2015;151:156–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Flores-Ferrer A, Marcou O, Waleckx E, et al. Evolutionary ecology of Chagas disease; what do we know and what do we need? Evol Appl. 2017;11(4):470–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Roellig DM, Brown EL, Barnabe C, et al. Molecular typing of Trypanosoma cruzi isolates, United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14(7):1123–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Garcia MN, Burroughs H, Gorchakov R, et al. Molecular identification and genotyping of Trypanosoma cruzi DNA in autochthonous Chagas disease patients from Texas, USA. Infect Genet Evol. 2017;49:151–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Herrera CP, Licon MH, Nation CS, et al. Genotype diversity of Trypanosoma cruzi in small rodents and Triatoma sanguisuga from a rural area in New Orleans, Louisiana. Parasit Vectors. 2015;8:123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dorn PL, Daigle ME, Combe CL, et al. Low prevalence of Chagas parasite infection in a nonhuman primate colony in Louisiana. J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci. 2012;51(4):443–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Grieves JL, Hubbard GB, Williams JT, et al. Trypanosoma cruzi in non-human primates with a history of stillbirths: a retrospective study (Papio hamadryas spp.) and case report (Macaca fascicularis). J Med Primatol. 2008;37(6):318–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Campos PF, Gilbert TM. DNA extraction from formalin-fixed material. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;840:81–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Moser DR, Kirchhoff LV, Donelson JE. Detection of Trypanosoma cruzi by DNA amplification using the polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27(7):1477–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Briones MR, Souto RP, Stolf BS, et al. The evolution of two Trypanosoma cruzi subgroups inferred from rRNA genes can be correlated with the interchange of American mammalian faunas in the Cenozoic and has implications to pathogenicity and host specificity. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1999;104(2):219–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Souto RP, Fernandes O, Macedo AM, et al. DNA markers define two major phylogenetic lineages of Trypanosoma cruzi. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1996;83(2):141–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fernandes O, Santos SS, Cupolillo E, et al. A mini-exon multiplex polymerase chain reaction to distinguish the major groups of Trypanosoma cruzi and T. rangeli in the Brazilian Amazon. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2001;95(1):97–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Garrison E, Marth G. 2012. Haplotype-based variant detection from short-read sequencing. arXiv:1207.3907 [q-bio.GN].

- 22. Dereeper A, Guignon V, Blanc G, et al. Phylogeny.fr: robust phylogenetic analysis for the non-specialist. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36(Web Server issue):W465–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Templeton AR, Crandall KA, Sing CF. A cladistic analysis of phenotypic associations with haplotypes inferred from restriction endonuclease mapping and DNA sequence data. III. Cladogram estimation. Genetics. 1992;132(2):619–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dumonteil E, Ramirez-Sierra MJ, Pérez-Carrillo S, et al. Detailed ecological associations of triatomines revealed by metabarcoding based on next-generation sequencing: linking triatomine behavioral ecology and Trypanosoma cruzi transmission cycles. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):4140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bern C, Kjos S, Yabsley MJ, et al. Trypanosoma cruzi and Chagas’ disease in the United States. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2011;24(4):655–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hodo CL, Wilkerson GK, Birkner EC, et al. Trypanosoma cruzi transmission among captive nonhuman primates, wildlife, and vectors. EcoHealth. 2018;15(2):426–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Guhl F, Ramirez JD. Retrospective molecular integrated epidemiology of Chagas disease in Colombia. Infect Genet Evol. 2013;20:148–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Garzon EA, Barnabe C, Cordova X, et al. Trypanosoma cruzi isoenzyme variability in Ecuador: first observation of zymodeme III genotypes in chronic chagasic patients. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2002;96(4):378–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Shender LA, Lewis MD, Rejmanek D, et al. Molecular diversity of Trypanosoma cruzi detected in the vector Triatoma protracta from California, USA. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10(1):e0004291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Curtis-Robles R, Auckland LD, Snowden KF, et al. Analysis of over 1500 triatomine vectors from across the US, predominantly Texas, for Trypanosoma cruzi infection and discrete typing units. Infect Genet Evol. 2018;58:171–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yeo M, Mauricio IL, Messenger LA, et al. Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) for lineage assignment and high resolution diversity studies in Trypanosoma cruzi. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011;5(6):e1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Charles RA, Kjos S, Ellis AE, et al. Southern plains woodrats (Neotoma micropus) from southern Texas are important reservoirs of two genotypes of Trypanosoma cruzi and host of a putative novel Trypanosoma species. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2013;13(1):22–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Aleman A, Guerra T, Maikis TJ, et al. The prevalence of Trypanosoma cruzi, the causal agent of Chagas disease, in Texas rodent populations. EcoHealth. 2017;14(1):130–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hodo CL, Bertolini NR, Bernal JC, et al. Lack of Trypanosoma cruzi infection in urban roof rats (Rattus rattus) at a Texas facility housing naturally infected nonhuman primates. J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci. 2017;56(1):57–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]