Abstract

Background

The outcome of patients with relapsed-refractory (R-R) acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is poor. Inotuzumab ozogamicin and blinatumomab have single-agent activity in R-R ALL. Their additions to low-intensity chemotherapy may further improved outcomes in ALL in first relapse.

Methods

The chemotherapy was lower intensity than conventional hyper-CVAD and referred to as mini-hyper-CVD. Inotuzumab was given on Day 3 of each of the first 4 cycles at 1.8–1.3 mg/m2 for cycle 1 followed by 1.3–1.0 mg/m2 for subsequent cycles. From Patient #39 and onwards, inotuzumab dose was reduced and fractionated into biweekly doses (0.6 mg/m2 and 0.3 mg/m2 during Cycle 1 and 0.3 mg/m2 and 0.3 mg/m2 during subsequent cycles), and blinatumomab for up to 4 cycles after inotuzumab therapy was administered.

Results

Forty-eight patients with Philadelphia chromosome-negative ALL in first relapse with a median age of 39 years were treated. Overall, 44 patients (92%) responded, 35 of them (73%) achieving complete response. The overall MRD negativity rate among responders was 93%. Twenty-four patients (50%) received ASCT. Veno-occlusive disease (VOD) of any grade occurred in 5 patients (10%). With a median follow-up of 31 months, the median PFS and OS were 11 and 25 months, respectively. The 2-year PFS and OS rates were 42% and 54%, respectively. Of the 24 patients (50%) who underwent ASCT, 14 patients are alive [13 (54%) in remission]. Of the remaining 20 responding patients who did not receive subsequent ASCT, 6 (30%) remain in remission at the last follow-up. Using the propensity score matching, the combination of mini-HCVD and inotuzumab +/− blinatumomab conferred better outcome than intensive salvage chemotherapy or inotuzumab alone.

Conclusions

The combination of inotuzumab with low-intensity mini-hyper-CVD chemotherapy +/− blinatumomab shows encouraging results in patients with ALL in first salvage.

Trial Registration

Clinicaltrials.gov Identifier NCT01371630

Keywords: inotuzumab ozogamicin, first relapse, salvage, ALL

Precis

The immunochemotherapy combination of inotuzumab with mini-hyper-CVD +/− blinatumomab was safe and effective in patients with ALL in first salvage. New strategies, including a weekly schedule of lower doses of inotuzumab, the sequential use of blinatumomab, and selection of least hepatotoxic transplant preparative regimens may further improve outcomes.

Introduction

Significant progress has been accomplished in acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). With modern intensive combination chemotherapy, the complete response (CR) rate in adults with ALL is 80–90% but cure rate is 40–50%.1–2 Outcome of patients who experience relapse is poor. Few patients can bridge to allogeneic stem cell transplantation (ASCT), the ultimate treatment with durable remissions.2–4 Salvage cytotoxic chemotherapy results in modest CR rates of 30–40% in first salvage, and the outcome is poor with a median survival of 6 months and a 5-year survival rate of less than 7%.3–4

Modern innovative approaches including new antibody therapies such as inotuzumab ozogamicin,5 the bispecific antibody construct blinatumomab,6 and the chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapies7–8 have recently shown promise for patients with relapsed or refractory (R-R) ALL, improving outcomes compared with conventional chemotherapy.

Inotuzumab ozogamicin, a CD22 monoclonal antibody bound to calicheamicin, resulted in an overall response rate of 80% and a median survival of 7.7 months among patients with R-R ALL.5 Blinatumomab, a bi-specific T-cell engaging CD3-CD19 antibody construct, also resulted in an overall response rate of 44% and a median survival of 7.7 months in a similar R-R ALL population.6 Better results were obtained in patients treated earlier (Salvage 1 versus Salvage 2 or later) and in patients with minimal disease burden; these patients can experience long-term survival.8–11

The addition of targeted immunotherapy inotuzumab ozogamicin to effective low-intensity chemotherapy in patients with R-R ALL has shown promising results with an overall response rate of 80% and a median survival of 11 months compared with 6 months with single-agent inotuzumab ozogamicin in similar patients population.10 Such strategy may translate into significant long-term survival benefit when used in patients in first salvage. Herein we report the results of an ongoing phase II study that evaluates the efficacy and safety of this combination in patients with ALL in first salvage.

Methods

Study design and participants

Patients with Philadelphia chromosome-negative CD22-positive ALL in first salvage were eligible. Patients had to have an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 3 or less, normal cardiac function (defined by ejection fraction above 50%), and adequate organ functions (serum bilirubin ≤ 1.5 mg/dL and serum creatinine ≤ 2.0 mg/dL). Patients were excluded if they had an active infection not controlled by antibiotics, clinical evidence of grade 3 to 4 heart failure as defined by the New York Heart Association criteria, or second malignancy. All patients signed an informed consent form in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. The trial was registered on clinicaltrials.gov with the identifier NCT01371630.

Treatment

The chemotherapy was lower intensity than conventional hyper-CVAD and referred to as mini-hyper-CVD.10, 12 Briefly, odd cycles included cyclophosphamide (150 mg/m2 every 12 hours on Days 1 to 3) and dexamethasone (20 mg per day on Days 1 to 4 and 11 to 14) given at 50% dose reduction; no anthracycline was administered. Vincristine (2 mg flat dose) was given on Day 1 and 8. Even cycles included methotrexate 250 mg/m2 on Day 1 (75% dose reduction) and cytarabine given 0.5 g/m2 given every 12 hours on Day 2 and 3 (83% dose reduction). Inotuzumab was administered on Day 3 of each of the first 4 cycles. Inotuzumab was given at 1.8–1.3 mg/m2 for cycle 1 followed by 1.3–1.0 mg/m2 for subsequent cycles. Cycles were administered every 4 weeks for a total of 8 cycles.

Rituximab was administered on days 1 and 11 of Cycles 1 and 3 and on days 1 and 8 of Cycles 2 and 4 in patients with CD20 expression ≥ 20%.13 Central nervous system (CNS) prophylaxis consisted of intrathecal therapy with methotrexate and cytarabine given alternately on Days 2 and 7 of each cycle for a total of 8 doses. Order of intrathecal chemotherapy was reversed with the even cycles: cytarabine on Day 2 and methotrexate on Day 7, to avoid simultaneous systemic and intrathecal methotrexate, which was previously suspected to cause rare demyelination and neurotoxicity. For patients presenting with active CNS disease, confirmed by cytologic examination of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), the intrathecal regimen was repeated twice weekly until the CSF became clear of leukemic cells and the CSF cell count normalized. Patients then received intrathecal therapy once a week for 4 weeks or until initiation of the next cycle of chemotherapy, when the regimen was resumed.

Maintenance therapy was given for 3 years with monthly vincristine at 2 mg for 1 year, prednisone 50 mg daily for 5 days every month for 1 year, 6-mercaptopurine 50 mg twice daily for 3 years, and methotrexate 10 mg/m2 orally weekly for 3 years (POMP regimen). Initiation of maintenance due to treatment-related toxicity prior to completion of the consolidation phase was allowed. Dose reductions of the cytotoxic agents according to the type and degree of side effects or toxicity were permitted and followed previously published guidelines.13–15 The decision to proceed with ASCT was at the discretion of the treating physician after discussion with the patient. Factors taken into account were usually the salvage status (S1 versus S2), the achievement of negative MRD status, and the lack of prior ASCT performed in CR1 (lower risk of VOD).

In order to reduce the risk of veno-occlusive disease (VOD) and further improve the outcome, the protocol was amended in February 2017 to use lower doses of weekly inotuzumab and to add to the consolidation phase 4 cycles of blinatumomab. This amendment affected first salvage patient #39 and onwards. The weekly lower dose schedule of inotuzumab was found to be safe and as effective as the single monthly schedule. Favorable outcomes correlated with lower clearance rate and better area under the curve (AUC) provided by the weekly lower dose schedule than with higher loading doses obtained with the single monthly schedule.16 After this amendment, inotuzumab (2 weekly fractioned doses) was given at a total of 0.9 mg/m2 during cycle 1 fractionated into 0.6 mg/m2 on Day 2 and 0.3 mg/m2 on Day 8 of cycle 1, and a total of 0.6 mg/m2 during cycles 2, 3, and 4 fractionated into 0.3 mg/m2 on Day 2 and 0.3 mg/m2 on Day 8 of the subsequent 3 cycles. Only 4 cycles of hyper-CVD plus inotuzumab were given (i.e. cycles 1–4). Blinatumomab was administered after the inotuzumab-based cycles, for a total of 4 cycles, and before the initiation of the maintenance therapy (i.e. cycles 5–8). Blinatumomab was administered by continuous infusion at a standard dose of 9 mcg/day in the first four days of the first cycle then the dose was escalated to 28 mcg/day by for the rest of the cycle and then at 28 mcg/day for 4 weeks in the subsequent cycles. Cycles were 6 weeks with 4 weeks on and 2 weeks off.

Supportive care

Supportive care measures were implemented according to standard guidelines. Tumor lysis prophylaxis with allopurinol, or alternatives such as rasburicase, and appropriate intravenous hydration were administered in the first course to all patients. Prophylactic antimicrobial therapy was administered to all patients during periods of neutropenia beginning in induction. Pegfilgrastim 6 mg subcutaneously was administered on Day 4–5 (+ 2 days) of each of the induction/consolidation cycles. Ursodiol 300 mg orally three times daily as VOD prophylaxis was systematically administered since September 2015.

Outcomes

The primary endpoints of the analysis were the overall response rate (including CR, CR with incomplete platelet recovery [CRp], and CR with incomplete hematologic recovery [CRi]) and overall survival (OS). Secondary endpoints included safety measures, progression-free survival (PFS), the rate of subsequent ASCT, and the MRD negativity rate of patients who achieved CR or CRp. CR was defined as the presence of ≤5% blasts in the bone marrow, with more than 1 × 109/L neutrophils, more than 100 × 109/L platelets in the peripheral blood, and no extramedullary disease. CRp was defined as CR except for platelets less than 100 × 109/L. CRi was defined as CR but with an absolute neutrophil count of less than 1 × 109/L and platelets less than 100 × 109/L.

MRD assessment by 6-color flow cytometry was performed on whole bone marrow specimens as previously described.17 A distinct cluster of at least 20 cells that showed altered antigen expression was regarded as an aberrant population, which yielded a sensitivity of 1 in 10,000 cells (for adequate specimens in which 2 × 105 cells could be collected). Relapse was defined by recurrence of more than 5% lymphoblasts in a bone marrow aspirate unrelated to recovery, or by the presence of extramedullary disease. PFS was calculated from the time of response until relapse or death. OS was calculated from the time of treatment initiation until death.

Adverse events were defined as any event that occurred between the first dose and 2 months after the last dose, all treatment-related events that occurred after the last dose, and all cases of VOD (of any cause) that occurred within 2 years after inotuzumab therapy. VOD was assessed and diagnosed by the investigators and evaluated according to previously defined clinical criteria.

Statistical analysis

This is a phase II study in R-R Philadelphia chromosome-negative ALL, in which 79 consecutive patients were treated. This report is of the 48 patients treated in first salvage. The trial was continuously monitored, with an early stopping rule in place if it was ever likely that the trial’s OS was less than that of previous similar trials. No stopping rules were met. Survival curves were plotted by the Kaplan-Meier method and compared with the log-rank test. Differences in subgroups by different covariates were evaluated with the χ2 test or Fisher exact test for nominal values and the Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables.

For a comparison with a historical cohort of patients treated with inotuzumab ozogamicin and with standard salvage chemotherapy, a 1:1 propensity score matching was performed to balance covariates in first salvage including age, gender, performance status, Salvage 1 status (primary refractory; CR duration < 12 months; CR duration ≥12 months), prior ASCT, white blood cell count, the percentage of blasts in bone marrow aspirate, karyotype, the percentage of CD20 and CD22 by flow cytometry between cohorts for the evaluation of response and survival.18 Multiple imputations were performed before the calculation of propensity scores for missing data to reduce bias.19 Censoring at the time of ASCT was performed to remove the effect of ASCT on survival for the comparison between propensity score matched cohorts. Significance was defined as a p-value <0.05.

Results

Patient characteristics and treatment

From November 2012 to January 2018, 48 patients in first salvage were treated. The patients’ baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Their median age was 39 years (range, 18 to 87 years). Thirty-eight patients (79%) received mini-HCVD and inotuzumab and 10 patients (21%) received the combination of mini-HCVD and inotuzumab followed by blinatumomab. Five patients (10%) were primary refractory and 23 (48%) had a first CR duration of more than 12 months. Seven patients (15%) had failed prior ASCT. Thirteen patients (27%) had diploid karyotype and 6 (13%) had 11q23 abnormalities, 4 (8%) of whom had t(4;11). The median CD22 expression was 95% (range, 20 to 100%). The median CD19 expression was 99.9% (range, 46.5 to 100%). Nine patients (19%) were CD20-positive and received rituximab during the first 4 cycles. There was no difference in patients’ baseline characteristics between those who received the original treatment and those who received the modified one including the weekly inotuzumab followed by blinatumomab (data not shown). No patients had received prior therapy with inotuzumab or blinatumomab before the enrollment in the study.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics (N=48)

| Characteristic | Category | N (%)/ Median [range] |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 39 (18–87) | |

| Gender | Male | 20 (42) |

| ECOG performance status | ≥2 | 7 (15) |

| WBC (× 109/L) | Median | 4.4 (0.5–129.9) |

| ≥50 | 2 (4) | |

| BM blasts ≥50% | 34 (71) | |

| Karyotype | Diploid | 13 (27) |

| MLL | 6 (13) | |

| Miscellaneous | 19 (40) | |

| ND/IM | 10 (21) | |

| CD22 expression | Median | 95.2 (20–100) |

| CD20 expression | ≥20% | 9 (19) |

| Prior ASCT | 7 (15) | |

| Salvage 1 status | Salvage 1, primary refractory | 5 (10) |

| Salvage 1, CRD1 <12 months | 20 (42) | |

| Salvage 1, CRD1 ≥12 months | 23 (48) |

ECOG= Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; BM=bone marrow; WBC=White blood cell; PB=peripheral blast; ND=not determined; IM=insufficient metaphases; CRD=complete remission duration

Response

Overall 44 of the 48 patients responded for an overall response rate of 92% (Table 2). Thirty-five patients (73%) achieved CR, 8 patients (17%) had CRp, and 1 patient (2%) had CRi. Three patients (6%) had resistant disease and 1 patient (2%) died within 4 weeks of start of therapy. All patients with primary refractory disease (n=5) and those with a first CR duration of more than 12 months (n=23) responded for an overall response rate of 100%. The response rate in patients with first CR duration less than 12 months was 80%. Overall, patients received a median of 3 cycles of therapy (range, 1 to 8 cycles). Twenty four patients (50%) underwent ASCT after a median of 3 months in second CR (CR2; range, <1 to 9 months).

Table 2.

Best overall response

| Response | N | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Morphologic response | ||

| CR | 35 | 73 |

| CRp | 8 | 17 |

| CRi | 1 | 2 |

| ORR | 44 | 92 |

| MRD negativity | ||

| At response | 28/41 | 68 |

| Overall | 38/41 | 93 |

| No response | 3 | 6 |

| Early death | 1 | 2 |

| Response by salvage 1 status | ||

| Salvage 1, primary refractory | 5/5 | 100 |

| Salvage 1, CRD1 <12 months | 16/20 | 80 |

| Salvage 1, CRD1 ≥12 months | 23/23 | 100 |

CR=complete response; CRp=CR with incomplete platelet recovery; CRi=CR with incomplete hematologic recovery; ORR=overall response rate; MRD=minimal residual disease; CRD= complete remission duration

Among patients who responded, 41 patients were assessed for MRD status at the time of morphologic response. The MRD negativity rates at the time of morphologic response and at any time within 3 cycles were 68% and 93%, respectively. The overall complete cytogenetic response among the 21 patients with morphologic response and abnormal cytogenetic available for assessment was 90% (19/21 responses).

Survival Outcomes

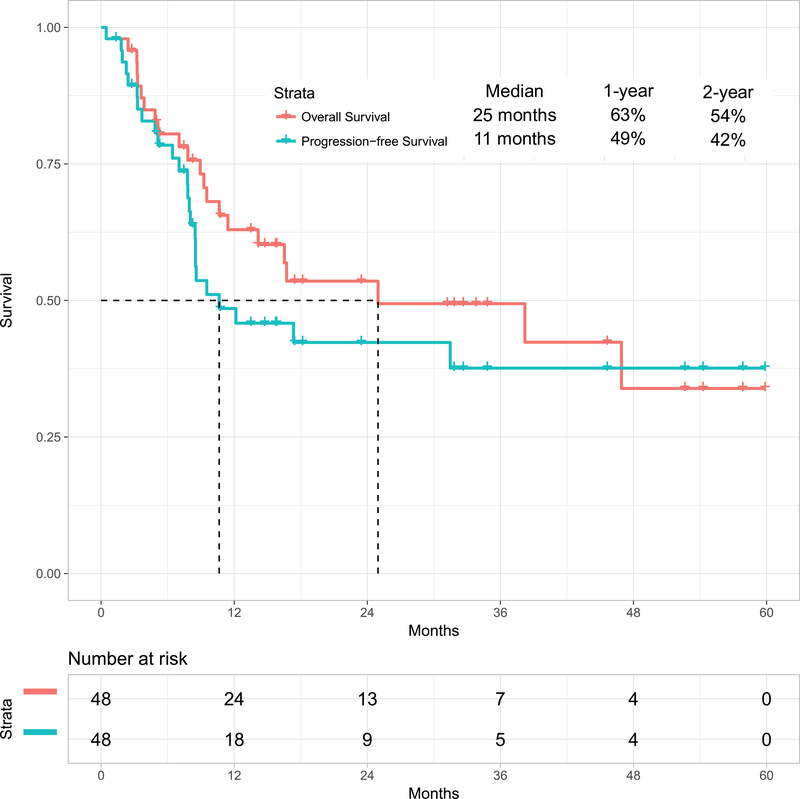

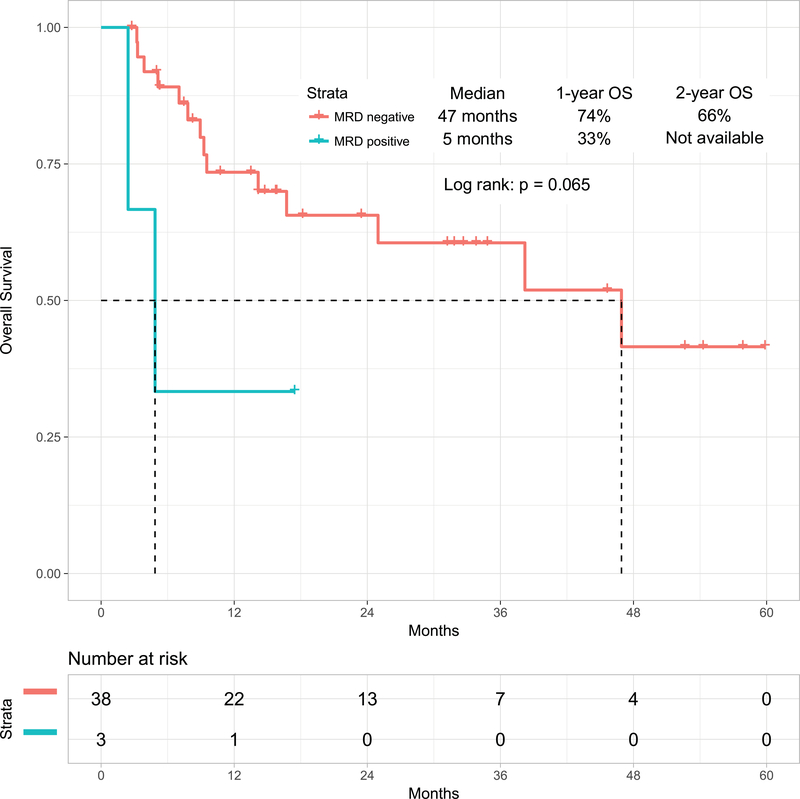

With a median follow-up of 31 months (range, 1 to 60 months), 26 patients (54%) were alive, 23 of whom (48%) were in CR (13 post-ASCT). The estimated 2-year OS rate was 54% (95% confidence interval [CI], 37%−68%)) and PFS rate was 42% (95% CI, 27%−58%). The median OS and PFS were 25 months and 11 months respectively (Figure 1A). The 1-year OS rates for patients treated with the original combination (n=38) versus the modified one including weekly lower dose of inotuzumab followed by blinatumomab (n=10) were 63% (95% CI, 46%−76%) and not available, respectively. Survival by MRD status is shown in Figure 1B for the 41 patients assessed for MRD. Patients achieving MRD negativity had better outcomes. The 1-year OS rates were 74% (95% CI, 55%−85%) for patients with MRD-negative status (n=38) versus 33% (95% CI, 1%−77%) for patients with MRD-positive status (n=3) (median OS: 47 months versus 5 months, respectively; p=0.06). Six patients (13%) achieved durable MRD-negative second remission without subsequent ASCT.

Figure 1A:

Overall survival for the whole cohort and progression-free survival

Figure 1B:

Overall survival by minimal residual status

Feasibility of Subsequent Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplantation

Among the 48 patients treated, 24 patients (50%) were able to proceed to ASCT in CR2 (5 related donors; 9 match unrelated donors, 10 haploidentical). At present, 13 of 24 patients remain in remission and alive after ASCT. The 2-year OS rate of patients who underwent ASCT in Salvage 1 was 65% (95% CI, 44%−86%) with a median OS of 38 months. The median time from start of therapy to ASCT was 18 weeks (range 8 to 34 weeks). In a landmark analysis at week 15, the 2-year OS rates for patients who received subsequent ASCT and those who did not were 64% (95% CI, 44%−86%) and 52% (95% CI, 25%−80%), respectively (p=0.8317) (Figure 2). The median OS were 38 months and not reached, respectively. The median time from the end of inotuzumab therapy to ASCT was 10 weeks (range 4 to 40 weeks). VOD was observed in 3 of 24 patients (13%) who received subsequent ASCT versus 2 of 24 patients (8%) who did not; these 2 patients had failed prior ASCT. VOD was observed in 5 of 38 patients (13%) treated with mini-hyper-CVD-inotuzumab compared with 0 of 10 patients (0%) treated with mini-hyper-CVD-inotuzumab-blinatumomab (4 of the 10 received a subsequent ASCT). Of the 24 patients who underwent ASCT in second remission, 10 patients died (2VOD; 8 relapse); 14 patients are alive (13 CR; 1 alive after relapse).

Figure 2:

Overall survival with or without subsequent allogeneic stem cell transplantation

Safety

All 48 patients were evaluable for safety analyses. The treatment was well-tolerated with most side effects being Grade 1 to 2. Early mortality defined as death within 4 weeks was observed in 1 patients (2%). Overall, patients received a median of 3 cycles of induction-consolidation therapy (range, 1 to 8 cycles). Of the 142 induction/consolidation cycles received by all the patients, 41% were delivered within 4 weeks, 53% were delivered within 4 to 8 weeks, and 6% were delivered over 8 weeks interval. Ten patients (21%) received a median of 2 cycles of blinatumomab (range, 1 to 4 cycles). Of the 5 patients who received later maintenance, 3 patients switched to maintenance before completing their full induction-consolidation therapy [median number of cycles was 4 (range, 4 to 5 cycles)] for myelosuppression (n=1), deconditioning (n=1), and infections (n=1). Twelve patients (25%) received all four planned cycles of inotuzumab and 2 (4%) received all four planned cycles of blinatumomab. Five patients (10%) had inotuzumab dose reduction (1 thrombocytopenia, 2 liver dysfunction, 1 sepsis, 1 intractable nausea) after a median of 2 cycles (range, 2 to 4 cycles).

Median time to platelet and neutrophil recovery for Cycle 1 was 26 and 17 days, respectively, and 22 and 15 days for subsequent cycles. Overall, 79% of the patients had prolonged thrombocytopenia beyond 6 weeks either during induction in 17/48 patients (35%) or subsequent courses in 47/94 (50%). Infections occurred in 32 patients (67%); 9 patients (19%) had Grade 3–4 hyperglycemia; 6 (13%) had Grade 3–4 increased bilirubin; 8 (17%) had Grade 3–4 increased liver function tests; 8 (17%) had Grade 3 hypokalemia; and 4 (8%) had Grade 3 hemorrhage (Table 3). VOD occurred in 5 patients (10%) (median age 39; range, 26 to 50) after a median of 3 cycles (range, 1 to 5). All 5 patients were exposed to ASCT, 2 received ASCT prior to inotuzumab therapy; 3 received ASCT after inotuzumab therapy.

Table 3.

Non-hematologic toxicities including all grade 3/4 toxicities and all grade toxicities encountered in ≥10% regardless of causality

| Toxicity | All Grade, N (%) | Grade3/4, N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Hyperglycemia | 25 (52) | 9 (19) |

| Increased liver function tests | 44 (92) | 8 (17) |

| Hypokalemia | 17 (35) | 8 (17) |

| Increased bilirubin | 36 (75) | 6 (13) |

| Anemia | 48 (100) | 40 (83) |

| Veno-occlusive disease | 5 (10) | 5 (10) |

| Hemorrhage | 19 (40) | 4 (8) |

| Headache | 26 (54) | 3 (6) |

| Constipation | 17 (35) | 3 (6) |

| Mucositis | 11 (23) | 3 (6) |

| Dehydration | 5 (11) | 3 (6) |

| Nausea | 32 (67) | 2 (4) |

| Fatigue | 25 (52) | 2 (4) |

| Neuropathy | 14 (29) | 2 (4) |

| Ocular symptoms | 5 (10) | 1 (2) |

| Vomiting | 15 (31) | 0 |

| Hypomagnesemia | 9 (19) | 0 |

| Skin rash | 6 (13) | 0 |

| Edema | 6 (13) | 0 |

| Arthralgias | 5 (10) | 0 |

After the emergence of VOD, the study was amended: the inotuzumab dose was reduced to 0.9 mg/m2 during the first cycle and 0.6 mg/m2 during subsequent cycles and fractionated into 2 weekly doses. In addition, blinatumomab was introduced with the aim to distant ASCT from the last dose of inotuzumab without compromising the efficacy of the regimen. There was a significant decrease in the VOD rates. The rates were 13% (5/38) with the original schedule and 0% (0/10) after the protocol amendment. Five of the 5 cases of VOD were fatal, 2 being directly attributed to VOD (Table 4).

Table 4.

Patients and VOD characteristics

| Patients | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | #1 | #2 | #3 | #4 | #5 |

| Age, (years) | 26 | 31 | 39 | 46 | 50 |

| Prior ASCT | No | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Conditioning | NA | Flu/Clo | NA | Bu/Flu/Clo | NA |

| # cycles | 5 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| Subsequent ASCT | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Conditioning | Bu/Clo | NA | Bu/Flu/Clo/SAHA | NA | Bu/Flu post transplant Cy |

| Dose | 1.3/1/1/1 | 1.8/1.3/1.3 | 1.8/1.3 | 1.3/1/1 | 1.3/1/1 |

| Status | Died | Died | Died | Died | Died |

VOD=veno-occlusive disease; ASCT=allogeneic stem cell transplantation; Y=yes; N=no; Flu=fludarabine; Clo=clofarabine; Cy=cyclophosphamide; Bu=busulfan; SAHA = suberoylanilide hydroxamine; NA=not applicable

Propensity Score Matching with Historical Cohorts

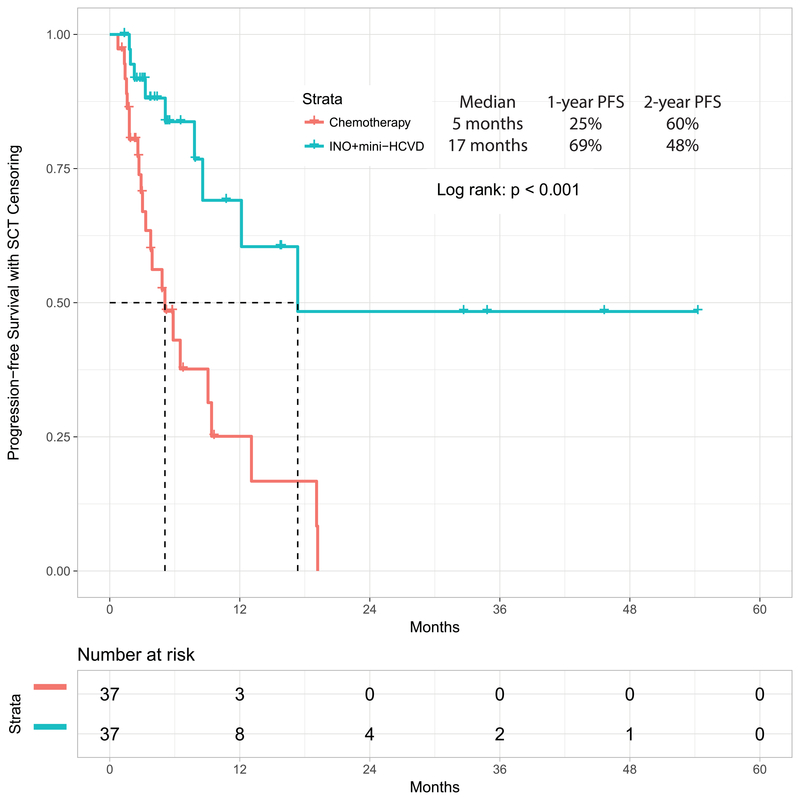

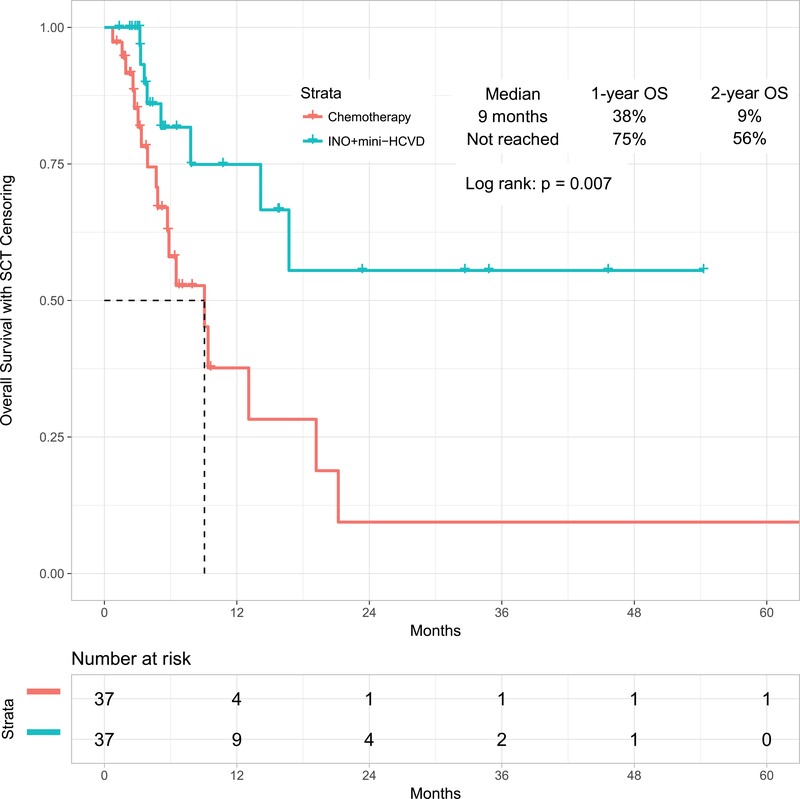

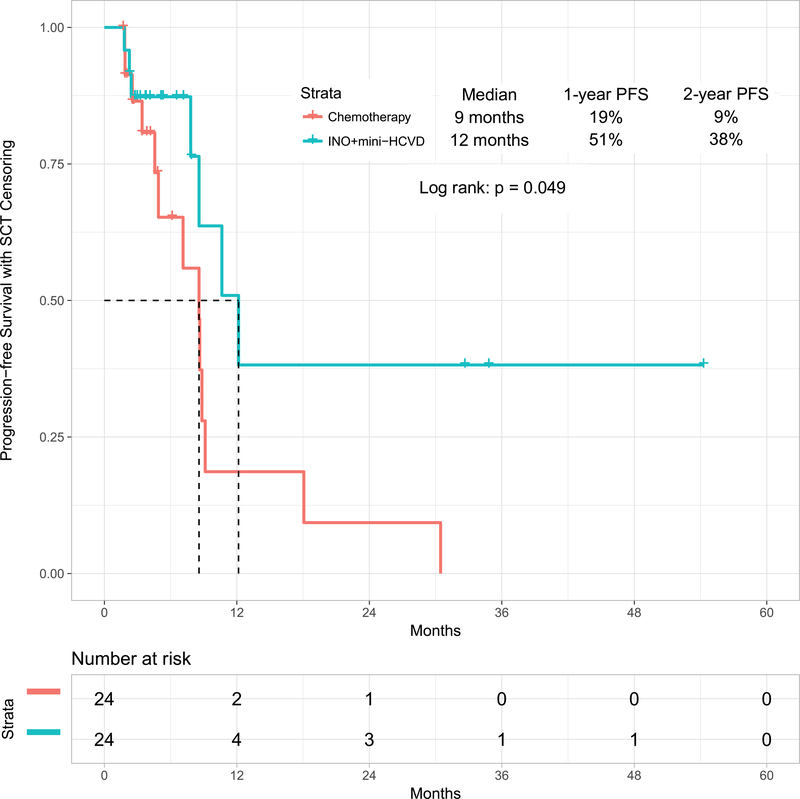

In a post-hoc analysis, we compared the outcomes obtained with the mini-hyper-CVD in combination with inotuzumab with or without blinatumomab with our previous experience in similar patients treated with standard salvage chemotherapy (n=89) or with inotuzumab monotherapy (n=29). When comparing standard salvage chemotherapy with the combination of mini-hyper-CVD and inotuzumab, the propensity score matching identified 37 patients in each cohort (Supplemental Table 1). The overall response rates for standard chemotherapy versus the combination of mini-HCVD inotuzumab with or without blinatumomab were 68% (95% CI, 52%−83%) and 97% (95% CI, 92%−100%), respectively (p=0.010). The median PFS were 5 months (95% CI, 2.4–7.8), and 17 months (95% CI, not available), respectively (p<0.001) (Figure 3A). The median OS were 9 months (95% CI, 5.3–12.9) and not reached (95% CI, not available), respectively (p=0.007) (Figure 3B).

Figure 3A:

Progression-free survival by therapy: mini-HCVD plus inotuzumab +/− blinatumomab versus standard chemotherapy using propensity score matching

Figure 3B:

Overall survival by therapy: mini-HCVD plus inotuzumab +/− blinatumomab versus standard chemotherapy using propensity score matching

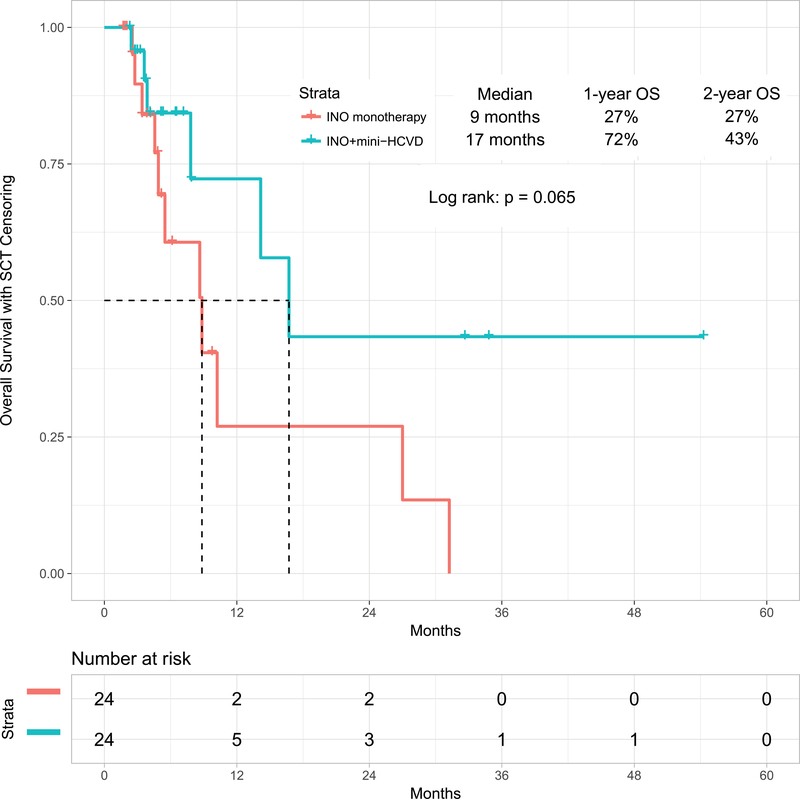

When comparing inotuzumab monotherapy with the combination of mini-hyper-CVD and inotuzumab with or without blinatumomab, the propensity score matching identified 24 patients in each cohort (Supplemental Table 2). The overall response rates for inotuzumab alone versus the combination of mini-HCVD inotuzumab with or without blinatumomab were 79% (95% CI, 62%−97%) and 92% (95% CI, 80%−100%), respectively (p=0.018). The median PFS were 9 months (95% CI, 6.3–10.8) and 12 months (95% CI, 7.6–16.8), respectively (p=0.049) (Figure 3C), (p=0.049). The median OS were 9 months (95% CI, 4.1–13.6) and 17 months (95% CI, 10.6–22.9), respectively (p=0.065) (Figure 3D).

Figure 3C:

Progression-free survival by therapy: mini-HCVD plus inotuzumab +/− blinatumomab versus inotuzumab monotherapy using propensity score matching

Figure 3D:

Overall survival by therapy: mini-HCVD plus inotuzumab +/− blinatumomab versus inotuzumab monotherapy using propensity score matching

Discussion

In this phase II study, the immunochemotherapy combination of inotuzumab with minihyper-CVD +/− blinatumomab was safe and effective in patients with ALL in first salvage. The overall response rate was 92%, and 2-year PFS and OS rates were 42% and 54%, respectively. The results are encouraging and compare favorably with our historical data in Salvage 1 with standard chemotherapy (median survival 4 months) and single-agent inotuzumab (median survival 9 months) or blinatumomab (median survival 11 months).5–6 This benefit was obtained without increased myelosuppression or other significant adverse events.

Until recently, the outcome of patients with relapsed ALL was poor, with only 7% alive at 5 years.4 Innovative approaches including new monoclonal antibody therapies (the anti-CD22 antibody-drug conjugate inotuzumab ozogamicin), the bispecific antibody construct blinatumomab, and the chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapies have recently shown promise for patients with R-R ALL. But the improvements observed remain modest, and the cure rates are below 20%.5–8 Our study shows that a significant and safe improvement can occur by combining low-intensity chemotherapy with these new agents, particularly in Salvage 1. The median survival of 25 months appears superior to standard chemotherapy and to the use of either blinatumomab or inotuzumab as monotherapy in Salvage 1.

ASCT is still considered the only curative treatment option in R-R ALL, with salvage therapies being used as a bridge to ASCT.20–21 This is particularly true in Salvage 1. In this study, almost half of the patients treated received subsequent ASCT. The favorable outcome of these patients is in line with our previous report which showed that ASCT in patients with morphologic and flow MRD response in Salvage 1 results in the best outcome, with a cure rate approaching 50%.9 This is in contrast to the outcome of patients treated in Salvage 2, where the achievement of flow MRD response and subsequent ASCT had no impact on survival.

The combination of low-intensity chemotherapy with inotuzumab was safe with a low rate of early mortality (4%) and did not result in an increased myelosuppression; most cycles being delivered within 3 to 5 weeks as designed. Liver toxicities and VOD are known to occur with inotuzumab treatment. In this study, these rates were 17% and 10%, respectively, similar to what was previously reported.6, 16,22 Several modifications were implemented to decrease this rate, including the use of lower weekly doses of inotuzumab and the sequential use of blinatumomab during the consolidation phase and before ASCT (longer time interval between the last inotuzumab dose and ASCT). We have previously reported fewer hepatic adverse events and VOD with the weekly schedule of inotuzumab;21 these adverse events were probably related to the peak levels of inotuzumab. Lower weekly dose schedule was associated with lower clearance rate, lower loading peak, and better AUC, and consequently better safety profile. The addition of blinatumomab allowed distancing ASCT from the last dose of inotuzumab without compromising efficacy. Although the follow-up is short and these results are preliminary, this strategy appears to be successful, with a decrease in the VOD rates (0% versus 13%), but longer follow-up is needed. Further improvement of outcome might be achieved with optimal selection of the transplant preparative regimen to minimize further hepatotoxicity and the use of VOD-preventive measures (e.g. ursodiol, defibrotide).

CAR T-cell therapies are an exciting development in cancer treatment. In a recent report of 83 adults treated with CD19 CAR T-cells, the CR rate was 83% (56% among all enrolled patients), and median event-free and overall survival were 6.1 months and 12.9 months, respectively.8 The rates of Grade ≥3 cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and neurologic events were 26% and 42%, respectively. Thus, while a direct comparison cannot be made with our results (Salvage status, disease burden, safety profile, etc..) a safe and effective combination of low- intensity chemotherapy with inotuzumab +/− blinatumomab compares favorably to the CAR T-cell strategy, particularly since the best outcomes with CAR T-cells were obtained in patients with minimal disease (marrow blasts <5%), whereas our regimen was used in patients with full relapse. Therefore, the lower-intensity regimen seems currently preferable in first relapse. However, these treatment modalities are not competitive but rather complementary, and could be administered sequentially to produce the deepest and most sustainable remissions possible. The rational combination of monoclonal antibodies, bispecific antibody constructs and CAR T-cells may reduce the need for long-term intensive chemotherapy and may obviate the need for ASCT in many patients.

In summary, the combination of low-intensity chemoimmunotherapy is safe and highly effective in patients with ALL in first salvage. The new strategies, including a weekly schedule of lower doses of inotuzumab, the sequential use of blinatumomab, and selection of least hepatotoxic transplant preparative regimens may further improve outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors received research grants from Pfizer and Amgen. Pfizer provided free drug from the Pfizer Investigator Sponsored Trial program. The authors declare no other conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Jabbour E, O’Brien S, Konopleva M, Kantarjian H. New insights into the pathophysiology and therapy of adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer. 2015;121(15):2517–2528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kantarjian HM, Thomas D, Ravandi F, et al. Defining the course and prognosis of adults with acute lymphocytic leukemia in first salvage after induction failure or short first remission duration. Cancer. 2010;116(24):5568–5574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gökbuget N, Dombret H, Ribera JM, et al. International reference analysis of outcomes in adults with B-precursor Ph-negative relapsed/refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Haematologica. 2016;101(12):1524–1533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fielding AK, Richards SM, Chopra R, et al. Outcome of 609 adults after relapse of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL); an MRC UKALL12/ECOG 2993 study. Blood. 2007;109(3):944–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kantarjian HM, DeAngelo DJ, Stelljes M, et al. Inotuzumab ozogamicin versus standard therapy for acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(8):740–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kantarjian H, Stein A, Gokbuget N, et al. Blinatumomab versus Chemotherapy for Advanced Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(9):836–847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maude SL, Laetsch TW, Buechner J, et al. Tisagenlecleucel in children and young adults with B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med 2018;378:439–448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park JH, Rivière I, Gonen M, et al. Long-term follow-up of CD19 CAR therapy in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med 2018;378:449–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jabbour E, Short NJ, Jorgensen JL, et al. Differential impact of minimal residual disease negativity according to the salvage status in patients with relapsed/refractory B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer. 2017;123(2):294–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jabbour E, Ravandi F, Kebriaei P, et al. Salvage chemoimmunotherapy with inotuzumab ozogamicin combined with mini-hyper-CVD for patients with relapsed/refractory Philadelphia chromosome-negative acute lymphoblastic leukemia. JAMA oncology. 2018;4(2):230–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dombret H Survival by salvage status in the Tower trial. Haematologica. 2017;102(s2):179 Abstract S478. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kantarjian H, Ravandi F, Short NJ, et al. Inotuzumab ozogamicin in combination with low-intensity chemotherapy for older patients with Philadelphia chromosome-negative acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: a single-arm, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19(2):240–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jabbour E, Kantarjian H, Ravandi F, et al. Combination of hyper-CVAD with ponatinib as first-line therapy for patients with Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: a single-centre, phase 2 study. The Lancet Oncology. 2015;16(15):1547–1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thomas DA, Faderl S, Cortes J, et al. Treatment of Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphocytic leukemia with hyper-CVAD and imatinib mesylate. Blood. 2004;103(12):4396–4407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kantarjian H, Thomas D, O’Brien S, et al. Long-term follow-up results of hyperfractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone (Hyper-CVAD), a dose-intensive regimen, in adult acute lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer. 2004;101(12):2788–2801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ravandi F, Jorgensen JL, O’Brien SM, et al. Minimal residual disease assessed by multi-parameter flow cytometry is highly prognostic in adult patients with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. British journal of haematology. 2016;172(3):392–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Austin PC. An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies. Multivariate Behav Res. 2011. May;46(3):399–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sterne JA, White IR, Carlin JB, et al. Multiple imputation for missing data in epidemiological and clinical research: potential and pitfalls. BMJ. 2009. June 29;338:b2393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goldstone AH, Richards SM, Lazarus HM, et al. In adults with standard-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia, the greatest benefit is achieved from a matched sibling allogeneic transplantation in first complete remission, and an autologous transplantation is less effective than conventional consolidation/maintenance chemotherapy in all patients: final results of the International ALL Trial (MRC UKALL XII/ECOG E2993). Blood. 2008;111(4):1827–1833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marks DI, Wang T, Perez WS, et al. The outcome of full-intensity and reduced-intensity conditioning matched sibling or unrelated donor transplantation in adults with Philadelphia chromosome-negative acute lymphoblastic leukemia in first and second complete remission. Blood. 2010;116(3):366–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kantarjian H, Thomas D, Jorgensen J, et al. Inotuzumab ozogamicin, an anti-CD22-calecheamicin conjugate, for refractory and relapsed acute lymphocytic leukaemia: a phase 2 study. The Lancet Oncology. 2012;13(4):403–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kantarjian H, Thomas D, Jorgensen J, et al. Results of inotuzumab ozogamicin, a CD22 monoclonal antibody, in refractory and relapsed acute lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer. 2013;119(15):2728–2736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.