Abstract

The existence of evolutionary conservation in base pairing is strong evidence for functional elements of RNA structure, although available tools for rigorous identification of structural conservation are limited. R-scape is a recently developed program for statistical prediction of pairwise covariation from sequence alignments, but it initially showed limited utility on long RNAs, especially those of eukaryotic origin. Here we show that R-scape can be adapted for a more powerful analysis of structure conservation in long RNA molecules, including mammalian lncRNAs.

Keywords: Long non-coding RNAs, Covariation analysis, Conserved structure, lncRNA structure, RNAalifold

Introduction

Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) are well accepted as crucial regulators of gene expression and disease progression1. Despite the ubiquity and significance of lncRNAs, our understanding of structure-function relationships within this class of molecules is extremely limited2. Studies of ribozymes, riboswitches, viral RNAs, mRNA UTRs and even coding sequences have shown that conserved RNA secondary and tertiary structures are vital for RNA function3; 4. It has therefore been of interest to determine whether lncRNA molecules contain regions of functional structure and whether these structures are conserved. If conservation in base pairing could be established, it would provide one powerful indicator that RNA structure plays a role in aspects of lncRNA function. Several empirical studies have demonstrated the existence of structured regions within lncRNAs, and multiple sequence alignments were found to support the empirically-determined structures5; 6; 7. Indeed in at least two cases, these modules of RNA structure were flanked by highly conserved sequences that are consistent with a biological role for lncRNA substructures6; 7.

However, a powerful new method for stringent determination of nucleotide covariation, known as R-scape, failed to support base pairing conservation in well-studied functional lncRNAs such as Xist and HOTAIR8, casting doubt on the importance of the empirically determined structures of those lncRNAs to their associated functions. Like many tools for phylogenetic analysis, the performance of R-scape was evaluated on a test set of mostly small, highly structured RNA molecules for which many sequences are available (such as bacterial riboswitches). We reasoned that, at least in its current form, R-scape might not be equipped to confront the challenges posed by large, multidomain eukaryotic RNA molecules.

We therefore set out to test the limitations of R-scape covariation analysis and to determine whether the approach could be improved in order to evaluate the presence of conserved structures in large mammalian RNAs, especially long noncoding RNAs. An inherent issue is that the amount of covariation support for conserved RNA structures is highly dependent on the number and phylogenetic diversity of aligned sequences, and we found that this can considerably limit the analytical power of R-scape. To address this and other issues, we propose an adapted strategy that both improves the applicability of R-scape analysis to mammalian lncRNAs and facilitates exploration of locally conserved structural motifs in other long RNAs.

Results and Discussion

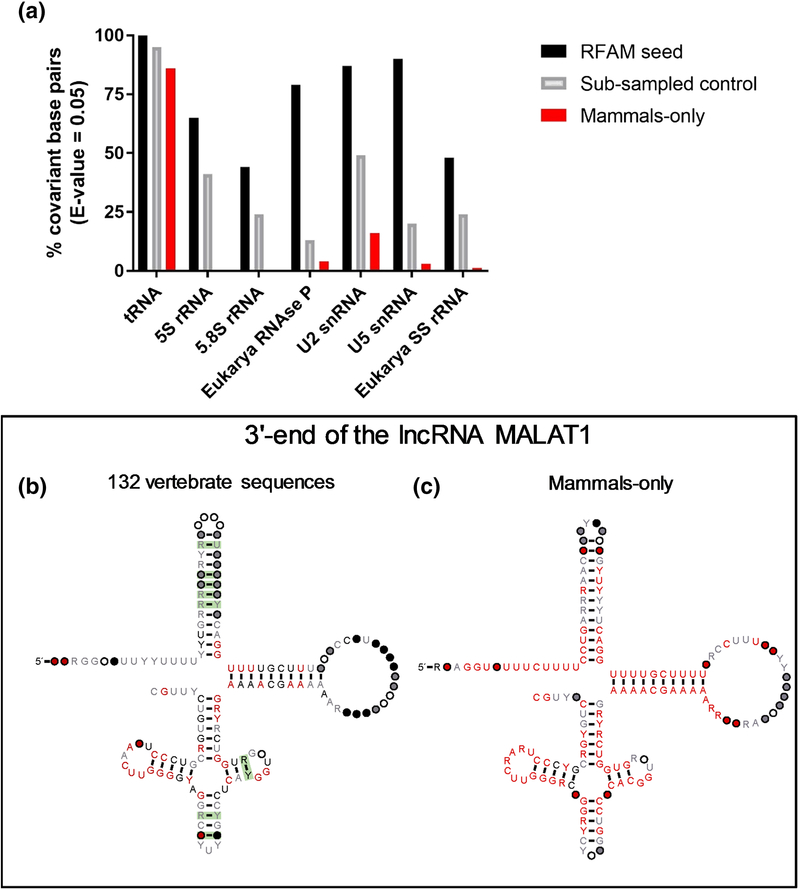

The predictive power of R-scape is significantly reduced when the alignment is restricted to mammalian sequences

A major challenge for the analysis of eukaryotic lncRNAs is the severe limitation in available sequences9. We reasoned that this limitation, rather than any inherent lack of evidence for lncRNA structure, might explain the reported inability of R-scape to identify conserved structure in mammalian lncRNAs. To test this hypothesis, we analyzed the ability of R-scape to detect base pair covariation in seven well-characterized, highly structured RNA molecules (tRNA, 5S ribosomal RNA, 5.8S ribosomal RNA, eukaryotic RNase P, U2 snRNA, U5 snRNA and the eukaryotic small subunit ribosomal RNA) using input alignments that were restricted in three different ways: 1) Inclusion of the original RFAM seed alignment 2) Sub-sampled alignments and 3) Restriction to mammalian sequences. In the sub-sampled RFAM alignments, we limited the number of sequences and the average pairwise identity to control for effects arising solely from restrictions in these parameters (See Methods, Fig. 1a). The alignments restricted to mammalian sequences represent the currently available alignments that have been built for most lncRNAs. Not surprisingly, there is a precipitous drop in covariation support for most of these test RNAs in both the ‘sub-sampled’ and ‘mammalian sequence’ conditions. Eukaryotic RNase P (> 300 nt) is the most dramatic example, as only 13% of the base pairs can be flagged as covariant by R-scape in the sub-sampling analysis (Fig. 1a). It is also worth highlighting the particular case of 5.8S rRNA, for which the RFAM seed alignment already has a relatively high pairwise sequence identity (~68%). Predictably, R-scape finds covariation support for only 44% of the base pairs in the 5.8S rRNA structure, and no support (0%) upon restriction of the analysis to mammalian sequences. In fact, with the exception of tRNA, for which even mammalian sequences have high nucleotide diversity, R-scape was unable to detect the majority of covarying base pairings in these model RNAs when the input alignments were limited to mammals. These results indicate that R-scape fails to support structure conservation not just in lncRNAs, but in most of the structurally complex, well-characterized functional RNA molecules that have been tested.

Fig. 1.

(a) Restriction in alignment characteristics (number of sequences, average pairwise sequence identity and phylogenetic diversity) significantly impair the ability of R-scape to detect covariation in highly conserved structured RNAs. The percentage of covariant base pairs flagged by R-scape is shown in the graph for each type of tested RNA alignment. (b) R-scape analysis of the 3’-end of the lncRNA MALAT1. When the alignment is expanded to include sequences across vertebrates, R-scape detects covariant base pairs in this lncRNA. (b) R-scape fails to detect covariation when the alignment is restricted to sequences from mammals. The figure shows the graphical output of each analysis generated by R-scape using R2R drawing notation. Green boxes indicate covariant base pairs. Consensus nucleotide letters are colored according to their relative degree of sequence conservation in the alignment (75% identity in gray; 90% identity in black; 97% identity in red). Individual nucleotides are represented by circles according to their positional conservation and percent occupancy thresholds (50% occupancy in white; 75% occupancy in gray; 90% occupancy in black; 97% occupancy in red).

Given these findings, we wondered whether R-scape might detect structural conservation in lncRNAs if the alignment were expanded to include sequences from more diverse species. Indeed, as part of a recent study, the Spector lab in collaboration with the Eddy lab implemented the RNA sequence and structure-based homology detection approach Infernal and identified a region in the 3’-end of lncRNA MALAT1 that is conserved across vertebrates10. We therefore analyzed whether R-scape can detect conservation in this region using the 132 vertebrate sequences provided within the supplementary material from the Spector study10. This alignment includes sequences from multiple MALAT1-like genomic loci identified by a homology search in 32 vertebrates (thirteen mammals, nine fish, six reptiles, three birds, and one amphibian). With this diverse data set of vertebrate sequences, R-scape succeeds in detecting covarying base pairs in three out of six MALAT1 substructural helices (Fig. 1b). However, when the alignment was restricted only to mammalian sequences, R-scape did not predict any covarying base pairs (Fig. 1c) and thus, did not support conservation for the same structure. It is therefore important to be cautious in drawing conclusions that are based solely on R-scape analysis of mammalian sequence alignments for which sequence diversity is limited.

It is important to note that RFAM alignments are hand-curated and refined11, and deviations from RFAM’s ideal heuristics may bias R-scape results. This phenomenon was shown to be true for other covariation algorithms when RFAM alignments were compared to emulated genomic alignments as inputs12. Multiple sequence-based alignments from datasets like the TBA/Multiz (UCSC genome browser) can be used to build covariation models and generate structural alignments for lncRNAs, but these alignments lack the quality of RFAM alignments, which can then affect R-scape prediction sensitivity. Finally, since genomic alignments may not accurately reflect the regions of lncRNA loci that are actively expressed, there is a consistent need for direct characterization and annotation of lncRNA transcripts across species in order to improve identification of conserved sequence and structure motifs, as described elsewhere13; 14.

In addition to the issues discussed up to this point, an important general limitation of purely phylogenetics-based methods for studying noncoding RNA (ncRNA) structural conservation is that these methods disregard inherent features of the folding thermodynamics. Indeed, several groups have shown that combining folding free energy calculations and phylogenetic information improves identification of conserved ncRNA structures15; 16; 17. That said, the majority of tools that couple both methods lack a convenient system for scoring user-provided secondary structure models. It is of great interest to evaluate the thermodynamic propensity of homologous sequences to adopt a conserved fold, as implemented in several structural alignment and prediction tools18; 19. This approach was recently used to identify conserved structures in lncRNA-MEG3 that were obtained in conjunction with chemical probing data20.

Adjacent RNA sequences can impair R-scape function in the absence of a consensus secondary structure

R-scape has been suggested to improve the structural annotation of several RNAs, including ribosomal RNAs and riboswitches, and now RFAM RNA families include an R-scape optimized structure along with their accepted consensus secondary structures11. Given that R-scape uses the entire length of an RNA sequence for analysis, it is possible that the presence of regions outside the RNA structured core negatively impacts the ability of R-scape to identify structural conservation in the absence of a consensus annotation.

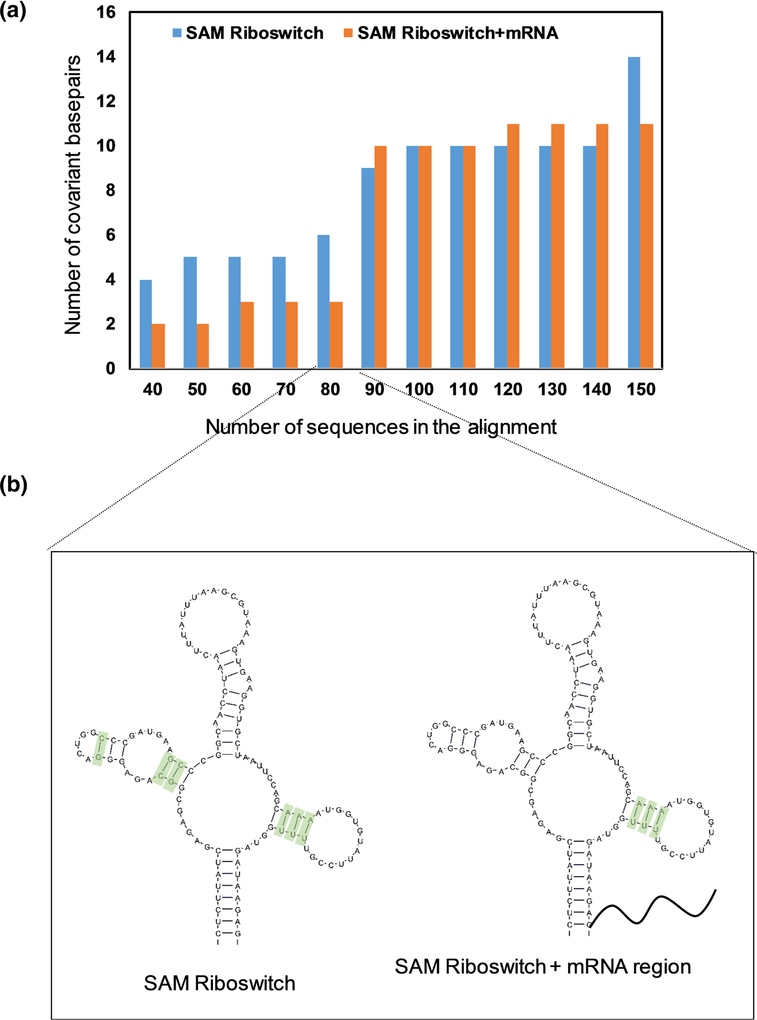

To test this, we analyzed the ability of R-scape to predict covariation when additional sequence is included in an alignment with no structural annotation, which is a common scenario in real life genomic analysis where the structured functional core of a molecule is not exactly known. Since R-scape reportedly optimizes the structure of the SAM-I riboswitch (RF00162), we chose it as an example, but now included the surrounding mRNA regions from the alignment. The mRNA regions were aligned using MAFFT21, and the alignment for the SAM-I riboswitch region was aligned based on secondary structure using RFAM seed alignment and Infernal. We then compared R-scape predictions by varying the number of sequences in the alignment. In the case of the SAM-I riboswitch alone, R-scape predicted significant covariation (two out of four helices have significant covarying base pairs) even with only 40 sequences in the alignment (Fig. 2a), as previously suggested, even in the absence of a user-provided consensus structure. However, inclusion of the flanking mRNA in the alignment caused a striking decrease in R-scape performance: Even when 80 sequences are included in the alignment, R-scape could identify covarying base pairs in only one helix (Fig. 2b), indicating that the presence of RNA regions outside the riboswitch structured core influence R-scape analysis output. Since a consensus structure was not used to restrict the R-scape search to a proposed set of base pairs, the presence of additional sequences downstream of the riboswitch core have a diluting effect on the covariation signal, resulting in fewer base pairs that pass the significance threshold (E-value = 0.05). However, as the number of sequences in the alignment increases (along with the number of covariation events), R-scape can identify more covarying base pairs, even when the mRNA regions are included.

Fig. 2.

The ability of R-scape to identify covariation within the SAM-I riboswitch (RF00162) in the absence of structural annotation is affected by the presence of additional flanking sequences in the alignment. (a) Sensitivity of R-scape to the presence of adjacent mRNA regions, as a function of the number of sequences in the alignment. (b) Influence of an adjacent mRNA region on predicted covariation in the SAM-I riboswitch, using 80 sequences in the alignment. Green boxes indicate covariant base pairs, manually drawn on a representive SAM riboswitch.

This suggests that R-scape may ultimately be able to predict an accurate consensus structure that maximizes covariation, provided that a sufficient number of sequences are included (> 90 for SAM-I riboswitch). However, since current alignments for many human lncRNA genes have a rather limited number of sequences (usually 30–60 for mammalian lncRNAs), we advise against using R-scape without an experimentally validated structural annotation, particularly in the context lncRNA covariation analysis.

A windowing approach can improve the performance of R-scape on long RNA alignments

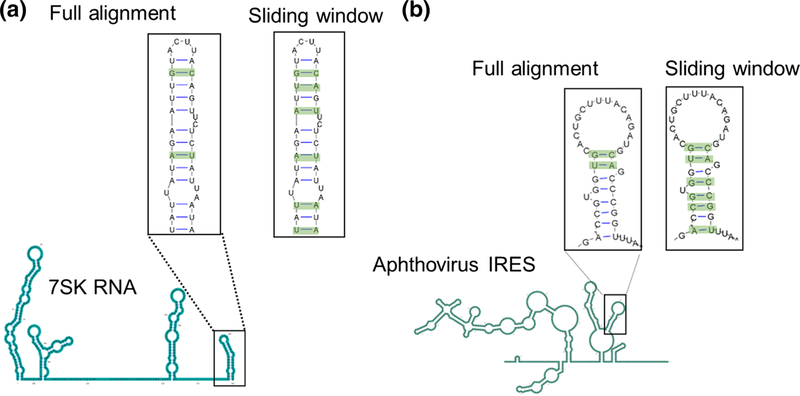

Another feature that is expected to influence the performance of any covariation analysis is the length of an RNA molecule and of its corresponding structural alignment. Long noncoding RNAs are typically very large and many exceed 1kb22. However, R-scape was benchmarked on a test set consisting predominantly of small RNAs. Of the 104 RNAs in that test set8, there are only 21 RNAs with an average length greater than 200 nts and only seven that exceed 1kb, and all the seven are ribosomal RNAs. It is therefore unlikely that the published R-scape default parameters (see Methods) are appropriate for analysis of large RNAs. To test this, we asked whether R-scape performs better when the analysis is broken down in short overlapping windows tiling the entire RNA rather than when given a long whole-length alignment. We examined alignments (see methods) of two long RNAs using sliding windows: 1) 7SK RNA (RFAM ID:00100) and 2) Aphthovirus internal ribosome entry site (RFAM ID: 00210). For both RNAs, each of which contains known regions of conserved structure, R-scape reported more base pair conservation when the analysis was run in sliding windows than when given the full-length alignment (Fig. 3), indicating that R-scape default parameters are likely to work better on short alignments, either as aligned sequences of inherently small RNAs or long RNA alignments that have been analyzed in a set of sliding windows.

Fig. 3.

Sliding windows analysis can improve R-scape performance on long alignments. In both model cases tested in this study, 7SK RNA (a) and Aphthovirus IRES (b), R-scape identified four additional base pairs when the analysis was run in sliding windows. The consensus secondary structure of each RNA is shown in cartoon form (below), and insets (above) show the covariation predictions for specific domains. Predicted covariant base pairs are highlighted in green.

These observations can be understood if we consider the enhanced signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) in R-scape analyses when it is run on shorter RNA motifs: By breaking down the alignment in windows that capture individual RNA substructures, a smaller set of base pairs is searched by R-scape during each run, thereby potentially improving R-scape sensitivity on highly structured long RNAs for which a single full-length search would have operated with decreased S/N. In practical exploratory cases, experimentally-guided secondary structure models can be coupled with information content analysis (Shannon entropy) to identify well-determined structured regions embedded in long RNAs7; 23; 24. These regions constitute the sections of interest for R-scape analysis and can thus be examined independently, naturally maximizing the signal to noise ratio by restricting the search to the most relevant motifs.

R-scape detects covariation in the RepA section of lncRNA Xist

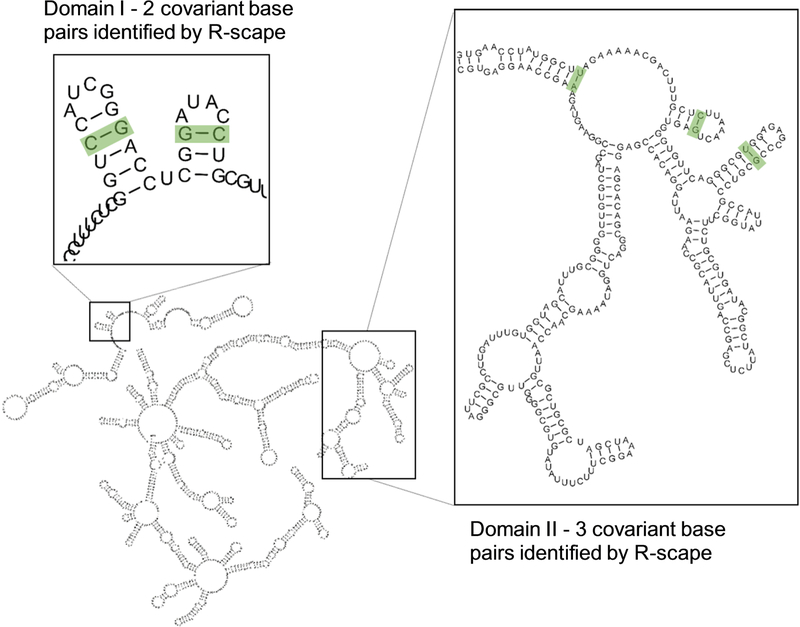

Taken together, the previous results suggest that one might be able to increase the signal-to-noise ratio for detecting RNA base pair covariation by maximizing the number of sequences (increasing alignment depth) and running R-scape analysis in short windows. Here, we applied both conditions to analyze the RepA region of lncRNA Xist. In a previous study, R-scape identified no significant base pair covariation in RepA structure8. However, the input alignment in that study was limited to ten sequences, which was beneath an empirical threshold value (~40 sequences) suggested in the very same paper. We therefore reanalyzed RepA using a recent, experimentally determined secondary structure7 and we included significantly more sequences in the alignment. As expected, just by adding more sequences we were able to identify covariation in RepA, but it was limited to a single base pair. Interestingly, this base pair is located within the functionally important repeat-five region25. To further improve the signal-to-noise ratio, we ran R-scape on short (500-nt) overlapping windows, tiling the entire RNA. Using this procedure, R-scape identified five statistically significant covariant base pairs: two in domain I and three in domain II of the lncRNA RepA (Fig. 4). Notably, each of the covariant base pairs detected are in the regions of high structural confidence (low Shannon entropy, see Liu et al.,7 and Supplementary Fig. S2), suggesting that conserved sub-structures are most likely to be found within these regions. It is also worth highlighting that the three base pairs in domain II identified by R-scape are in proximity to long-range crosslink sites identified by Liu et al. 20177, and to a stretch of conserved base sequence, suggesting that even though R-scape identified only five base pairs, they are consistent with experimental studies and are likely to be functionally important. This result effectively invalidates suggestions that R-scape does not identify conserved structure in lncRNAs8 and reinforces the need for a more careful analysis of conservation of lncRNA structures that considers the intrinsic characteristics of this class of genes.

Fig. 4.

R-scape analysis on the empirically-determined secondary structure of lncRNA RepA (Liu et al. 2017). The use of an alignment containing 57 sequences was coupled with a sliding windows approach in order to improve covariation analysis by R-scape. The experimentally determined secondary structure of the lncRNA is represented in the figure with insets showing the covariant base pairs (green boxes) identified by R-scape on specific motifs of RepA domain I and domain II (left and right insets, respectively).

Up to this point, our analysis suggests that the default mode in R-scape may not be sufficiently sensitive to detect RNA structure conservation with reduced alignment depth and low phylogenetic diversity, which are features inherent to most current lncRNA alignments (Xist, HOTAIR, SRA, etc). Most telling, when faced with similar alignments, R-scape failed to support conservation even for well-structured RNAs such as ribosomal RNAs, snRNAs and the eukaryotic ribozyme RNAseP, suggesting that more sequencing data is required to provide sufficient alignment depth for lncRNA structural conservation analysis on R-scape. Given the plethora of lncRNA genes and their implicated roles in human diseases, there is an urgent need for better tools and metrics to identify conserved structures and the associated functions of these complex molecules.

The RAFS statistic greatly increases the analytical power of R-scape and reveals conserved structures in lncRNAs

Based on the tests conducted above, it is clear that the default R-scape statistical metric (the G-test statistic) is not readily applicable to cases where sample size and phylogenetic diversity are severely limited, and this fundamentally reduces its utility in analyzing alignments with high sequence conservation and reduced depth, as in the case of lncRNAs. We therefore asked whether other statistical metrics could improve the performance of R-scape on alignments of lncRNAs and other related long RNA molecules. RNAalifold with stacking26 (Bsi,j renamed in Rivas et al., as RAFS) was previously shown to be among the best performing statistical metrics available and it has been extensively validated in several RNA structure prediction platforms, where it is frequently combined with structural stability metrics27; 28; 29. However, Rivas et al.8 have argued that the G-test statistic (GT) performs better than RAFS in terms of positive predictive value (PPV) and thus would be less prone to false positive discovery. To get a sense of the tradeoff between sensitivity and PPV within these two metrics, we reanalyzed the original R-scape test set (104 RFAM alignments annotated with their accepted consensus structures) using default parameters. We used average product correction (APC) as it was shown to improve the performance of both GT and RAFS (both renamed, then, as APC-GT and APC-RAFS)8. First, we measured the difference in sensitivity and PPV of these two metrics by varying the E-value threshold (Supplementary Fig. S3). At the default E-value threshold of 0.05, APC-RAFS resulted in much higher sensitivity (~84%) relative to APC-GT (~64%), with a PPV compromise of less than 4% (or null compromise for E-values < 0.01). This minor drop in PPV is not surprising because there is usually a trade-off between sensitivity and false discovery rate. For a better evaluation, we compared the sensitivity of both metrics at a fixed PPV threshold, i.e., within the same specificity level. At default E-value (0.05), APC-GT resulted in ~94% PPV and ~64% sensitivity. At 94% PPV, APC-RAFS showed ~13% higher sensitivity (~77%) than APC-GT, which suggests that APC-RAFS might be in fact a more robust metric. In this case, a PPV value of 94% is obtained by lowering the E-value threshold to 0.01: at this E-value, APC-RAFS shows higher sensitivity (~77%) and a PPV value (~94%) comparable to APC-GT at the default threshold (Supplementary Fig. S3a), suggesting that APC-RAFS has overall superior discriminative power than APC-GT.

To further test the predictive power of APC-RAFS in comparison to APC-GT, we tested both methods on the SAM riboswitch alignment including the flanking mRNA region, in the absence of structural annotation (also analyzed in Fig. 2). We varied the number of sequences in the alignment from 40 to 150 sequences and ran R-scape with APC-GT or APC-RAFS using exactly the same alignment as input for both metrics. In addition, we tested the predictions at two different E-value thresholds. At any given number of sequences in the alignment, APC-RAFS predicted more significant base pairs (Supplementary Fig. S4). It is worth pointing out that this alignment consists of 4000 columns and only the first 400 belong to the structured riboswitch region. At E-value = 0.01, with 60 sequences as the input (the number of sequences commonly available for lncRNAs), both metrics predicted zero false positives for the SAM-I structure. However, APC-RAFS resulted in 12 true positives and APC-GT predicted only 3 true positives. At E-value = 0.05, APC-RAFS resulted in 20 true positives and 2 false positives, while APC-GT resulted in 3 true positives and 0 false positives. These results agree with our benchmarking tests and suggest that APC-RAFS performs better than the default APC-GT on R-scape even in the absence of a consensus structural annotation, with much increased sensitivity and, importantly, similar specificity.

The RNAalifold algorithm30 scores alignment columns by assigning a high score to covariant base pairs (two compensatory mutations), a lower score to consistent half-flips (a single mutation that preserves the pairing) and a score of zero to identical pairs (see Methods and Supplementary Methods). In addition, RNAalifold penalizes positions where a base pair cannot form by adding a penalty term that decreases the score of column pairs containing inconsistent mutations and/or gaps. Finally, in its stacking-modified version (RAFS), the metric considers the stacking contribution of neighboring base pairs and calculates scores within the appropriate helical arrangement of each base pair. In the specific context of R-scape, the RAFS metric (or its APC-corrected form, APC-RAFS) produces informative scores even in cases of alignments with low mutation rates by considering how consistent a proposed structure is with the aligned sequences in addition to computing a stacking factor for each base pair. By contrast, the G-test only flags base pairs as conserved if they appear to be covariant and it disregards other alignment features that might either support or oppose individual base pairs, which becomes particularly problematic in cases with little sequence variation. It is therefore unsurprising that the G-test showed poorer predictive sensitivity than RAFS on the benchmarking tests, which is well in line with the previously reported superior performance of the RAFS algorithm in RNA structure conservation analysis when compared to mutual information metrics (closely related to the G-test statistic)26.

Next, we tested the performance of APC-GT and APC-RAFS on R-scape by varying the number of sequences in the input alignment (Supplementary Fig. S3). Strikingly, APC-RAFS achieved 63% sensitivity with only 20 sequences in the alignment compared to APC-GT, which resulted in only 40% sensitivity with the same input. We then used APC-RAFS to score the same alignments from Fig. 1 (Supplementary Fig. S5 and Fig. S6) and observed a significant improvement in detection of conserved base pairs under restricted conditions (fewer sequences, increased average pairwise identity and decreased phylogenetic diversity), relative to the original analysis using APC-GT. The eukaryotic RNAse P case showed a dramatic 45% sensitivity increase upon subsampled alignment analysis with APC-RAFS relative to APC-GT, and an even higher improvement (49%) on the mammalian sequence alignment. Remarkably, in the MALAT1 3’-end case, APC-RAFS identified conserved base pairs in four out of six helices from the mammals-only alignment (Supplementary Fig. S5b and S5c) although APC-GT failed to detect any conservation when given the same input alignment (Fig.1c). In all cases, the use of APC-RAFS on restricted alignments improved R-scape performance when compared to APC-GT with no compromise to specificity as given by PPV (Supplementary Fig. S6), indicating that APC-RAFS is able to at least partly overcome the negative effects of lncRNA-like restrictions on R-scape predictive power while preserving statistical rigor. These results indicate that APC-RAFS can be used on R-scape to identify conserved structured positions in RNA alignments and provides a more powerful alternative to alignments with reduced sequence variation where the APC-GT produces essentially non-informative results. All these observations suggest that APC-RAFS is a robust metric for evolutionary analysis of RNA structure with R-scape (null-model based statistical test) and, most importantly, the most suitable of the two evaluated methods for alignments with the restrictions normally found in lncRNAs.

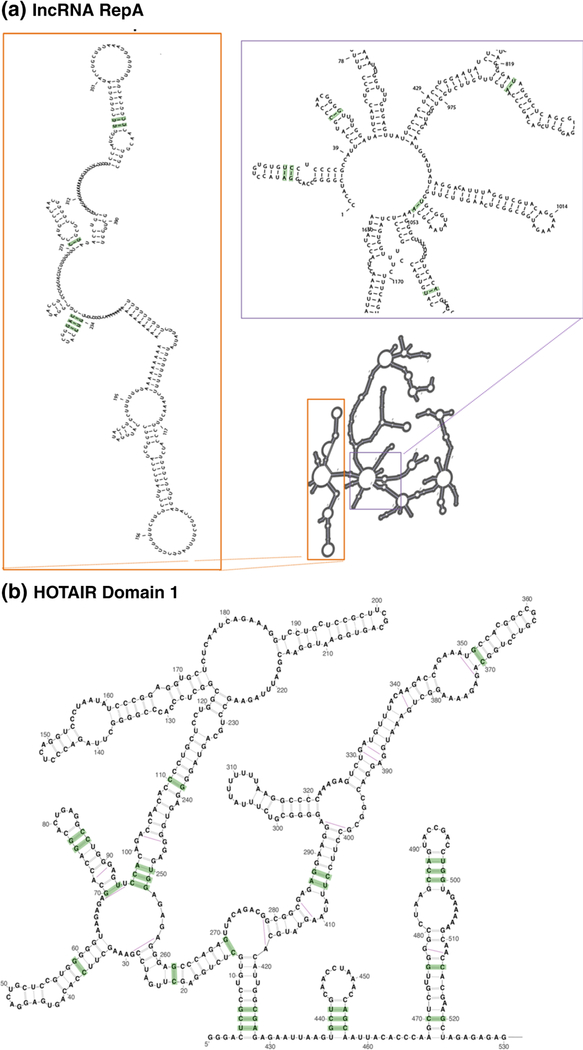

Based on the above observations, we utilized APC-RAFS to analyze the published structural alignments for full-length lncRNA RepA and Domain I of lncRNA HOTAIR6 (Fig. 5) and found that R-scape is now able to support conservation of numerous base pairs in both RNAs. We identified 16 conserved base pairs within the full-length lncRNA RepA when the alignment was analyzed in overlapping 500-nt windows tiling the RNA every 100 nt. In this case, 9 out of 10 helical motifs with base pairs flagged by R-scape/APC-RAFS were also suggested to be conserved in previous empirical studies7. When we looked at domain I of HOTAIR, 24 conserved base pairs were found by R-scape/APC-RAFS within 10 helical segments of this region. Also, in this case, the majority of base pairs identified as conserved by APC-RAFS are located within helices that had been implied as conserved by previous reports6. It is important to note, however, that APC-RAFS did not support base pairing conservation for other regions of HOTAIR, with the exception of three base pairs in domain IV (data not shown). Although the four domains of HOTAIR have similar levels of primary sequence conservation, only domains I and IV show evidence for base pairing conservation and, not by coincidence, these are the two regions of this lncRNA that were found to interact with its protein partners6. These results suggest that APC-RAFS can be used within R-scape to improve the analysis of lncRNA structure conservation and highlight the presence of conserved structured regions in lncRNAs HOTAIR and RepA.

Fig. 5.

R-scape analysis on lncRNAs RepA and HOTAIR using APC-RAFS as the covariation statistic. (a) The experimental secondary structure map of full-length lncRNA RepA is shown and evolutionarily conserved base pairs identified on specific motifs by R-scape using APC-RAFS are indicated in green boxes. (b) The experimental secondary structure of HOTAIR domain I is represented in the figure and evolutionarily conserved base pairs identified by R-scape using APC-RAFS are shown in green boxes.

In conclusion, we show that the R-scape default parameters as defined in Rivas et al.8 are not readily applicable to large RNAs, but that R-scape can operate with increased sensitivity when appropriately parameterized. We suggest that increased alignment depth, a sliding windows approach and a more appropriate statistical metric, the APC-RAFS, can help R-scape to identify conserved structural elements in large molecules such as lncRNAs. By combining these approaches, we were able to detect conserved structural motifs in the empirically-determined secondary structures of lncRNAs MALAT1, HOTAIR and RepA. We hope that the results and approaches reported here provide improved tools for meeting the challenges inherent to studying lncRNA molecules and that they facilitate future studies and method development in the field.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Alignments

Seed alignments for tRNA, 5S ribosomal RNA, 5.8S ribosomal RNA, eukaryotic RNase P, U2 snRNA, U5 snRNA, small subunit ribosomal RNA (SS rRNA), 7SK, Aphthovirus IRES and SAM-I Riboswitch were downloaded from the RFAM database (RFAM v13.0). To obtain alignments restricted to mammals, mammalian sequences were manually extracted from each RNA family in the Rfam database and then aligned with Infernal (version 1.1.2) using the cmsearch program with default parameters and the corresponding Rfam covariance model. All the alignments used in this study are available as supplementary data.

MALAT1 3’-end alignment

We downloaded the sequences (supplementary file 9 (SF9), MALAT1–3h-tRNAlike.132.fa), and the covariation model (SF4, MALAT1–3h-tRNAlike.cm) was provided within the supplementary data of Zhang et al.10. We built the alignment of 132 vertebrate sequences using Infernal version 1.1.2 with the command ‘cmalign -o vertebrates-output.sto SF4.cm SF9.fa’. We built the alignment of sequences from mammals-only using the command ‘cmalign -o mammals-only.sto SF4.cm mammals-only.fa’. The file mammals-only.fa was created from the file SF9 by removing the sequences from species other than mammals and including one sequence per mammalian genome. The resulting file consists of thirteen sequences from thirteen mammalian species.

SAM-I riboswitch alignment

We randomly selected more than 150 SAM riboswitch sequences from the Rfam database (Rfam ID: RF00162). These sequences are selected such that there are at least 1000 or more nucleotides (mRNA regions) next to the 3’-end of the SAM riboswitch. We extracted the mRNA regions using NCBI BLAST. The mRNA regions were aligned using MAFFT webserver version 7 (https://mafft.cbrc.jp/alignment/server/) with default parameters. The riboswitch region was aligned using Infernal version 1.1.2 and the SAM riboswitch seed alignment downloaded from the Rfam database (RF00162). Briefly, we built a covariation model using the ‘cmbuild’ program, followed by calibration using ‘cmcalibrate’ and then we aligned the resulting 150 sequences using ‘cmalign’ program. The alignment with Riboswitch+mRNA region was created by manually concatenating the outputs from Infernal and MAFFT using a text editor.

R-scape analysis

All analyses using R-scape were carried out at the default E-value (0.05), unless otherwise specified in the text. Sub-sampling analysis was performed by randomly selecting sequences using the ‘submsa’ option. The average pairwise identity (Fig. 1a) was controlled using the ‘maxid’ option. The parameters and RFAM family IDs for all original and derived alignments are listed in Supplementary Fig. S1.

Sliding window analyses were carried out with the “window” and “slide” options on R-scape, to define window size and sliding step of the R-scape search, respectively. Window size was varied between 50 – 500 nt, depending on the RNA length and structure, thereby ensuring that intact helices could be contained within the chosen window size. The parameters used in Fig. 3 for the Aphthovirus IRES and 7SK analyses were “--window 100 --slide 25” and “--window 50 --slide 10”, respectively.

The R-scape software (version 0.2.1) and the alignment test-set were downloaded from the Eddy lab website (http://eddylab.org/R-scape/).

The average product corrected RNAalifold with stacking (APC-RAFS) and G-test (APC-GT) statistics were compared using the “RAFSp” and “GTp” options in R-scape version 0.2, by varying E-value thresholds and the number of sequences in the alignment.

Brief descriptions of the default search parameters on R-scape and the two evaluated covariation metrics (the G-test and RNAalifold with stacking) are given in Supplementary Methods, along with the statistical terminology employed on benchmarking tests. The sequence alignments, R-scape software and command line options used in this work are available as Supplementary Data

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Identifying conserved RNA structures in alignments with less diverse sequences is a challenging task.

The detection of conserved structures in well-studied mammalian lncRNAs has been challenging with existing statistical tools.

Here, we report strategies and improved parameters that allow identification of conserved structures in lncRNAs.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Thayne Dickey (Pyle lab, Yale) and Professor T.F. Chan (School of Life Sciences, Chinese University of Hong Kong) for critical evaluation and thoughtful comments on the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute; the National Institutes of Health [RO150313 to A.M.P.]; start-up funds from Drexel University College of Medicine and a CURE grant from the Pennsylvania Department of Health [to S.S.]. Funding for open access charge: Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Abbreviations

- R-scape

RNA Structural Covariation Above Phylogenetic Expectation

- HOTAIR

HOX transcript antisense RNA

- lncRNA

long non-coding RNA

- MALAT1

Metastasis Associated Lung Adenocarcinoma Transcript 1

- APC

average product correction

- RAFS

RNAalifold with stacking

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Schmitt AM & Chang HY (2017). Long Noncoding RNAs: At the Intersection of Cancer and Chromatin Biology. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pyle Anna M. (2014). Looking at LncRNAs with the Ribozyme Toolkit. Molecular Cell 56, 13–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mustoe AM, Busan S, Rice GM, Hajdin CE, Peterson BK, Ruda VM, Kubica N, Nutiu R, Baryza JL & Weeks KM (2018). Pervasive Regulatory Functions of mRNA Structure Revealed by High-Resolution SHAPE Probing. Cell 173, 181–195 e18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pirakitikulr N, Kohlway A, Lindenbach BD & Pyle AM (2016). The Coding Region of the HCV Genome Contains a Network of Regulatory RNA Structures. Mol Cell 62, 111–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Novikova IV, Hennelly SP & Sanbonmatsu KY (2012). Structural architecture of the human long non-coding RNA, steroid receptor RNA activator. Nucleic Acids Research 40, 5034–5051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Somarowthu S, Legiewicz M, Chillón I, Marcia M, Liu F & Pyle Anna M. (2015). HOTAIR Forms an Intricate and Modular Secondary Structure. Molecular Cell 58, 353–361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu F, Somarowthu S & Pyle AM (2017). Visualizing the secondary and tertiary architectural domains of lncRNA RepA. Nature Chemical Biology 13, 282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rivas E, Clements J & Eddy SR (2016). A statistical test for conserved RNA structure shows lack of evidence for structure in lncRNAs. Nature Methods 14, 45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nitsche A & Stadler PF (2017). Evolutionary clues in lncRNAs. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: RNA 8, e1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang B, Mao YS, Diermeier SD, Novikova IV, Nawrocki EP, Jones TA, Lazar Z, Tung C-S, Luo W, Eddy SR, Sanbonmatsu KY & Spector DL (2017). Identification and Characterization of a Class of MALAT1-like Genomic Loci. Cell reports 19, 1723–1738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kalvari I, Argasinska J, Quinones-Olvera N, Nawrocki EP, Rivas E, Eddy SR, Bateman A, Finn RD & Petrov AI (2018). Rfam 13.0: shifting to a genome-centric resource for non-coding RNA families. Nucleic Acids Research 46, D335–D342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith MA, Gesell T, Stadler PF & Mattick JS (2013). Widespread purifying selection on RNA structure in mammals. Nucleic Acids Research 41, 8220–8236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hezroni H, Koppstein D, Schwartz MG, Avrutin A, Bartel DP & Ulitsky I (2015). Principles of long noncoding RNA evolution derived from direct comparison of transcriptomes in 17 species. Cell Rep 11, 1110–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chillon I & Pyle AM (2016). Inverted repeat Alu elements in the human lincRNA-p21 adopt a conserved secondary structure that regulates RNA function. Nucleic Acids Res 44, 9462–9471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gruber AR, Findeiss S, Washietl S, Hofacker IL & Stadler PF (2010). RNAz 2.0: improved noncoding RNA detection. Pac Symp Biocomput, 69–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ruzzo WL & Gorodkin J (2014). De novo discovery of structured ncRNA motifs in genomic sequences. Methods Mol Biol 1097, 303–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fu Y, Xu ZZ, Lu ZJ, Zhao S & Mathews DH (2015). Discovery of Novel ncRNA Sequences in Multiple Genome Alignments on the Basis of Conserved and Stable Secondary Structures. PLoS One 10, e0130200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harmanci AO, Sharma G & Mathews DH (2011). TurboFold: iterative probabilistic estimation of secondary structures for multiple RNA sequences. BMC Bioinformatics 12, 108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tan Z, Fu Y, Sharma G & Mathews DH (2017). TurboFold II: RNA structural alignment and secondary structure prediction informed by multiple homologs. Nucleic Acids Res 45, 11570–11581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sherpa C, Rausch JW & Le Grice SF (2018). Structural characterization of maternally expressed gene 3 RNA reveals conserved motifs and potential sites of interaction with polycomb repressive complex 2. Nucleic Acids Res 46, 10432–10447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuraku S, Zmasek CM, Nishimura O & Katoh K (2013). aLeaves facilitates on-demand exploration of metazoan gene family trees on MAFFT sequence alignment server with enhanced interactivity. Nucleic Acids Research 41, W22–W28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Palazzo AF & Lee ES (2015). Non-coding RNA: what is functional and what is junk? Frontiers in Genetics 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Siegfried NA, Busan S, Rice GM, Nelson JA & Weeks KM (2014). RNA motif discovery by SHAPE and mutational profiling (SHAPE-MaP). Nat Methods 11, 959–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smola MJ, Christy TW, Inoue K, Nicholson CO, Friedersdorf M, Keene JD, Lee DM, Calabrese JM & Weeks KM (2016). SHAPE reveals transcript-wide interactions, complex structural domains, and protein interactions across the Xist lncRNA in living cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113, 10322–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pintacuda G, Young AN & Cerase A (2017). Function by Structure: Spotlights on Xist Long Non-coding RNA. Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences 4, 90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lindgreen S, Gardner PP & Krogh A (2006). Measuring covariation in RNA alignments: physical realism improves information measures. Bioinformatics 22, 2988–2995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Washietl S, Hofacker IL & Stadler PF (2005). Fast and reliable prediction of noncoding RNAs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102, 2454–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hofacker IL (2007). RNA consensus structure prediction with RNAalifold. Methods Mol Biol 395, 527–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bernhart SH, Hofacker IL, Will S, Gruber AR & Stadler PF (2008). RNAalifold: improved consensus structure prediction for RNA alignments. BMC Bioinformatics 9, 474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hofacker IL, Fekete M & Stadler PF (2002). Secondary structure prediction for aligned RNA sequences. J Mol Biol 319, 1059–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.