Abstract

Background

Maintaining care for ill persons in the community is heavily dependent on support from unpaid caregivers. Many caregivers, however, find themselves in a caring role for which they are ill prepared and may require professional support. The telephone is an easily accessible method of providing support irrespective of geographical location.

Objectives

The objective of this review was to evaluate the effectiveness of telephone support interventions, delivered by healthcare professionals, when compared to usual care or non‐telephone‐based support interventions for providing education and psychosocial support for informal caregivers of people with acute and chronic diagnosed illnesses, and to evaluate the cost‐effectiveness of telephone interventions in this population.

Search methods

We searched the following databases from inception to 16 November 2018: the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL); MEDLINE; Embase; PsycINFO; ProQuest Dissertations and Theses A&I; and CINAHL Complete. We also searched 11 caregiver‐specific websites, three conference links, and two clinical trial registries.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) (including cluster‐RCTs) and quasi‐RCTs. We excluded cross‐over trials because of the high risk of carry‐over effects from one intervention to another.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently screened citations against the review's inclusion criteria, extracted data, and assessed the included studies using the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool. The review's prespecified primary (quality of life and burden) and secondary outcomes (skill acquisition, psychological health, knowledge, health status and well‐being, family functioning, satisfaction, and economic outcomes), where reported, were assessed at the end of intervention delivery and at short‐term (≤ 3 months), medium‐term (> 3 to ≤ 6 months) and longer‐term time points (> 6 to 12 months) following the intervention. Where possible, meta‐analyses were conducted, otherwise results were reported narratively.

Main results

We included 21 randomised studies involving 1,690 caregivers; 19 studies compared telephone support interventions and usual care, of which 18 contributed data to the analyses. Two studies compared telephone and non‐telephone professional support interventions. Caregiver ages ranged from 19 years to 87 years across studies. The majority of participants were female (> 70.53%), with two trials including females only. Most caregivers were family members, educated beyond secondary or high school level or had the equivalent in years of education. All caregivers were based in the community. Overall risk of bias was high for most studies.

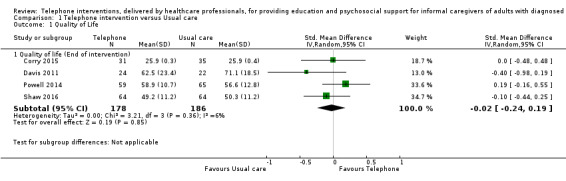

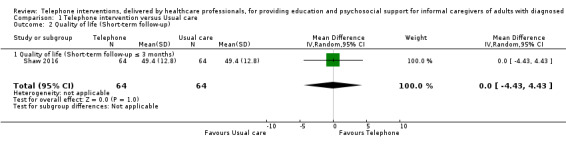

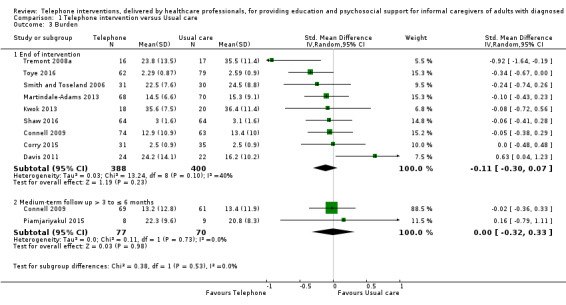

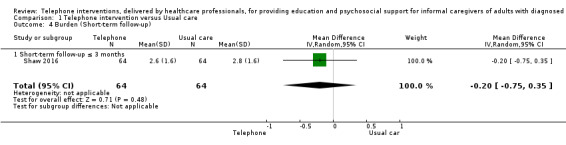

The results demonstrated that there is probably little or no difference between telephone support interventions and usual care for the primary outcome of quality of life at the end of intervention (SMD ‐0.02, 95% CI ‐0.24 to 0.19, 4 studies, 364 caregivers) (moderate‐certainty evidence) or burden at the end of intervention (SMD ‐0.11, 95% CI ‐0.30 to 0.07, 9 studies, 788 caregivers) (low‐certainty evidence). For one study where quality of life at the end of intervention was reported narratively, the findings indicated that a telephone support intervention may result in slightly higher quality of life, compared with usual care. Two further studies on caregiver burden were reported narratively; one reported that telephone support interventions may decrease burden, the other reported no change in the intervention group, compared with usual care.

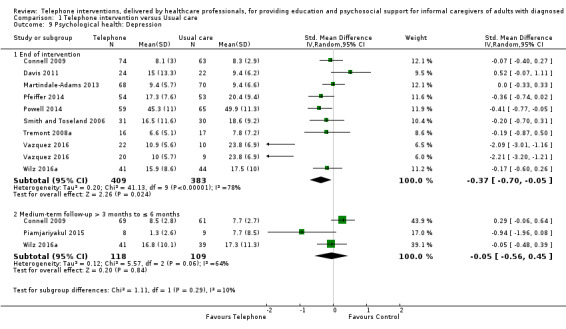

We are uncertain about the effects of telephone support interventions on caregiver depression at the end of intervention (SMD ‐0.37, 95% CI ‐0.70 to ‐0.05, 9 studies, 792 caregivers) due to very low‐certainty evidence for this outcome. Depression was reported narratively for three studies. One reported that the intervention may reduce caregiver depression at the end of intervention, but this effect was not sustained at short‐term follow‐up. The other two studies reported there may be little or no difference between telephone support and usual care for depression at the end of intervention. Six studies measured satisfaction with the intervention but did not report comparative data. All six reported high satisfaction scores with the intervention. No adverse events, including suicide or suicide ideation, were measured or reported by any of the included studies.

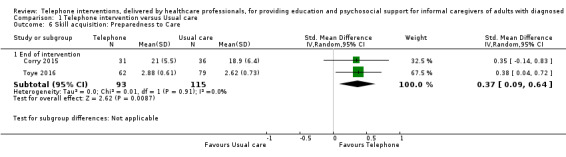

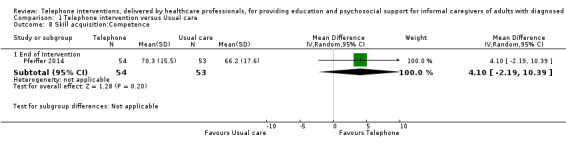

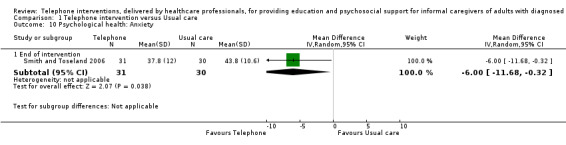

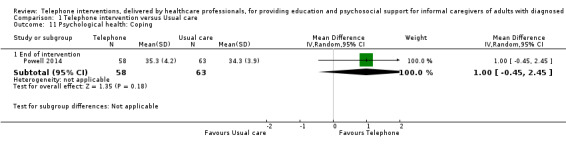

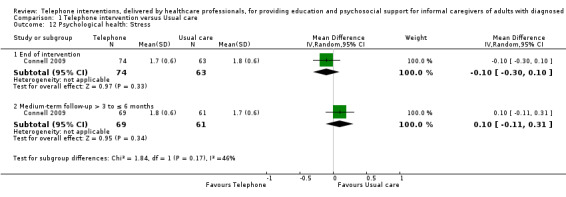

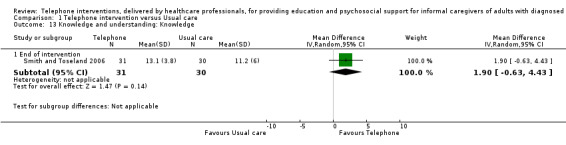

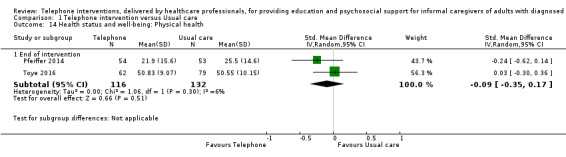

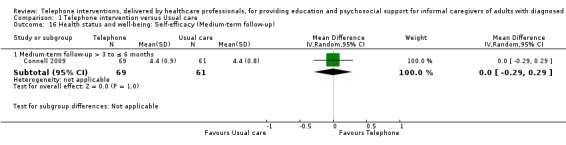

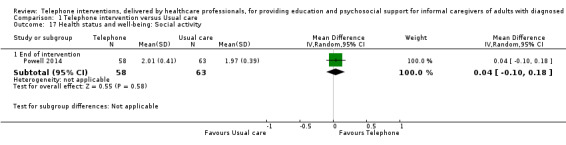

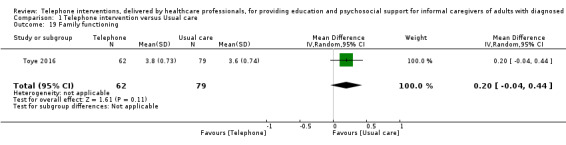

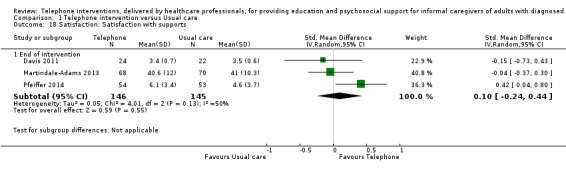

Our analysis indicated that caregiver anxiety may be slightly reduced (MD ‐6.0, 95% CI ‐11.68 to ‐0.32, 1 study, 61 caregivers) and preparedness to care slightly improved (SMD 0.37, 95% CI 0.09 to 0.64, 2 studies, 208 caregivers) at the end of intervention, following telephone‐only support interventions compared to usual care. Findings indicated there may be little or no difference between telephone support interventions and usual care for all of the following outcomes at the end of intervention: problem‐solving, social activity, caregiver competence, coping, stress, knowledge, physical health, self‐efficacy, family functioning, and satisfaction with supports (practical or social). There may also be little or no effect of telephone support interventions for quality of life and burden at short‐term follow‐up or for burden and depression at medium‐term follow‐up.

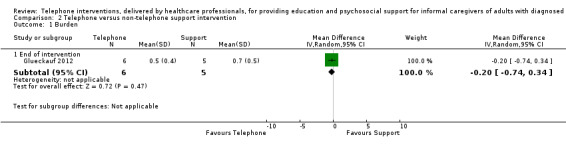

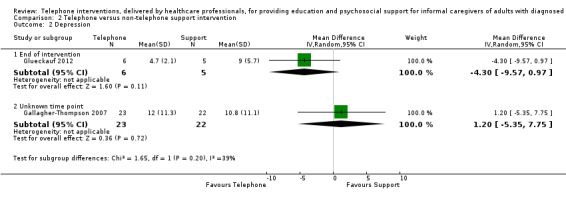

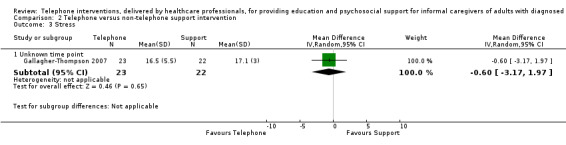

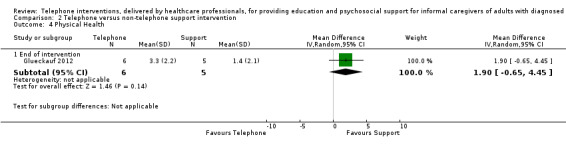

Litttle or no difference was found between groups for any of the reported outcomes in studies comparing telephone and non‐telephone professional support interventions. We are uncertain as to the effects of telephone support interventions compared to non‐telephone support interventions for caregiver burden and depression at the end of intervention. No study reported on quality of life or satisfaction with the intervention and no adverse events were reported or noted in the two studies reporting on this comparison.

Authors' conclusions

Although our review indicated slight benefit may exist for telephone support interventions on some outcomes (e.g. anxiety and preparedness to care at the end of intervention), for most outcomes, including the primary outcomes, telephone‐only interventions may have little or no effect on caregiver outcomes compared to usual care. The findings of the review were mainly based on studies with overall high risk of bias, and few participants. Further high‐quality trials, with larger sample sizes are required.

Keywords: Adult; Aged; Aged, 80 and over; Female; Humans; Male; Middle Aged; Young Adult; Chronic Disease; Chronic Disease/psychology; Psychosocial Support Systems; Telephone; Adaptation, Psychological; Anxiety; Anxiety/psychology; Caregivers; Caregivers/psychology; Depression; Depression/psychology; Family; Mental Health; Quality of Life; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Stress, Psychological; Stress, Psychological/psychology

Plain language summary

[Telephone interventions for providing education and psychosocial support to caregivers]

Background

Caregivers providing care to a family member, friend, or neighbour experience the role in differing ways. Some caregivers may find themselves in a caring role for which they are ill prepared and professional support is essential. This review examined whether telephone support interventions delivered by healthcare professionals had positive benefits on a range of outcomes including quality of life, burden (the experience of strain or load), skill acquisition (e.g. problem‐solving), psychological health (e.g. depression), knowledge, physical health, family functioning, satisfaction, or cost, for unpaid caregivers in the community. A telephone support intervention is one that is delivered via the telephone and designed to provide knowledge, advice, or help to caregivers to enable them to manage their own well‐being or that of the person they care for. It is an easily accessible method of providing support irrespective of geographical location. Studies that compared telephone support to usual care or to non‐telephone‐based professional support interventions were included.

Study characteristics

We included 21 studies involving 1,690 caregivers caring for persons with a range of diagnosed conditions. Caregiver ages ranged from 19 years to 87 years. Most were female and caring for a family member. The majority were spouses, in particular wives, except for one study that mainly focused on adult children. Most caregivers had greater than secondary school education. Eighteen studies reported funding from reputable sources.

Key results

Nineteen studies (18 studies contributing data) compared telephone support interventions and usual care. Telephone support interventions probably have little or no effect on caregiver quality of life (4 studies, 364 caregivers) and may have little effect on burden (9 studies, 788 caregivers) compared to usual care on completion of the intervention. Although anxiety may be slightly reduced and preparedness to care slightly improved following the intervention, we are uncertain about the effects on depression and overall, telephone interventions may have little or no effect on the outcomes assessed by this review. High satisfaction with the intervention was reported in six studies that measured this outcome, but no comparative data from usual care groups was reported.

Two studies compared telephone and non‐telephone‐based support interventions. There may be little or no evidence of an effect of telephone support when compared non‐telephone‐based support interventions for any reported outcome. No adverse events were measured or reported in any of the included studies.

Quality of evidence

The quality of the evidence was assessed as very low to moderate across outcomes, thus reducing confidence in the findings. Many of the results were based on data from single studies with few participants. Larger well‐designed studies are required to determine the effects of telephone support interventions.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Telephone support intervention compared to Usual care for providing education and psychosocial support for informal caregivers of adults with diagnosed illnesses.

| Telephone intervention compared to Usual care for providing education and psychosocial support for informal caregivers of adults with diagnosed illnesses | ||||

| Patient or population: Informal caregivers of adults with diagnosed illnesses Setting: Community Intervention: Education or psychosocial telephone support Comparison: Usual care | ||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

| Risk with Telephone intervention | ||||

|

Quality of Life End of intervention Assessed with: WHOQoL Brief instrument (26‐item), SF‐36 (0‐100 scale), SF‐12, and Adapted BKOS (15‐item, 0‐7 scale) For all scales, higher scores indicated higher QoL. |

The mean score for QoL in the intervention group was 0.02 standard deviations lower (0.24 lower to 0.19 higher) | 364 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1,2 | One further study reported that caregivers receiving a telephone intervention may have slightly higher QoL at end of intervention, compared with usual care. Overall, at the end of intervention, telephone interventions probably have little or no effect on caregiver QoL |

|

Burden End of intervention Assessed with: Revised Memory and Behaviour Problem Checklist (0‐24 range), 24‐ and 26‐item Caregiver Reaction Assessment, Family Appraisal of Caregiving Questionnaire (Caregiver Strain subscale – Palliative Care), Burden Interview (22‐ and 12‐item inventories; 0‐4 scale), Modified BKOS scale (22‐item, 5‐point scale) For all scales, higher scores indicated higher burden. |

The mean score for Burden in the telephone group was 0.11 standard deviations lower (0.3 lower to 0.07 higher) | 788 (9 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 2,3 | Two further studies reported caregiver burden. One reported that telephone interventions may decrease burden; the other reported no change in the intervention group, compared with usual care. Overall, at the end of intervention, telephone interventions may have little or no effect on caregiver burden. |

|

Psychological health: Depression End of intervention Assessed with: Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale 11‐item SF, 10‐item and, 20‐item measures (including German version) (0‐3 scales), Brief Symptom Inventory (18‐item, 5‐point scale), and the Geriatric Depression Scale (30‐item, score range 0‐30) For all scales, higher scores were associated with increased depression/symptoms of depression. |

The mean score for depression in the telephone group was 0.37 standard deviations lower (0.7 to 0.05 lower ) | 792 (9 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 2,4 | Three further studies reported caregiver depression. One reported that telephone interventions may decrease depression; the other two reported no change in the intervention group, compared with usual care. Overall, we are uncertain of the effects of telephone interventions on caregiver depression at the end of intervention. |

|

Satisfaction with the intervention End of intervention |

See comment | ‐ | ‐ | No study was found that assessed this outcome comparatively. Six studies measured satisfaction with the intervention in the intervention group only. All six reported high levels of satisfaction with the intervention (i.e. 'mostly', 'very much so', 'good' or 'excellent'). |

| Adverse events including suicide and suicide ideation | See comment | ‐ | ‐ | No studies measured these outcomes. |

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||

1 Although participant numbers were relatively few at n = 364, they were deemed sufficient for studies evaluating these types of intervention in a population of informal caregivers; we therefore did not downgrade on sample size (imprecision) for this reason.

2 Most information was from studies at low or unclear risk of bias on most items in the 'risk of bias' tool, although in some studies, one or two risk of bias criteria were assessed as having high risk of bias. We therefore downgraded by 1 level for plausible risk of bias that could seriously alter the results.

3 Some variation in the effect estimates and moderate heterogeneity; evidence downgraded by 1 level (serious inconsistency).

4 Variation in the effect estimates across studies and substantial heterogeneity; evidence downgraded by 2 levels (very serious inconsistency).

BKOS: Bakas Caregiver Outcomes Scale QoL: Quality of life SF: Short Form SF‐12: Short Form ‐12 items SF‐36: Short Form ‐ 36 items WHOQoL: World Healthcare Organisation Quality of Life

Summary of findings 2. Telephone support compared to non‐telephone support intervention for providing education and psychosocial support for informal caregivers of adults with diagnosed illnesses.

| Telephone compared to non‐telephone support intervention for providing education and psychosocial support for informal caregivers of adults with diagnosed illnesses | ||||

| Patient or population: Informal caregivers of adults with diagnosed illnesses Setting: Community Intervention: Education or psychosocial telephone support Comparison: Education or psychosocial non‐telephone support | ||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

| Risk with Telephone | ||||

| Quality of Life | No studies measured this outcome | ‐ | ‐ | |

|

Burden End of intervention Assessed with: the subjective burden subscale of the Caregiver Appraisal Inventory Higher scores indicated greater burden. |

The mean score for burden in the telephone group was 0.2 lower (0.74 lower to 0.34 higher) | 11 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1,2 | We are uncertain of the effects of telephone interventions on caregiver burden at the end of intervention. |

|

Psychological health: Depression: End of intervention Assessed with: Center for Epidemiological Studies Survey‐Depression scale (20‐item, 0‐3 scale) Higher scores indicated higher levels of depression. |

The mean score for depression in the telephone group was 4.3 lower (9.57 lower to 0.97 higher) | 11 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1,2 | We are uncertain of the effects of telephone interventions on caregiver depression at the end of intervention |

| Satisfaction with the intervention | No studies measured this outcome | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Adverse events including suicide and suicide ideation | No studies measured these outcomes | ‐ | ‐ | |

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||

1 Most information from the 1 included study indicated low or unclear risk of bias on most items on the 'risk of bias' tool, although risk of bias was high for selective reporting. We therefore downgraded by 1 level for plausible risk of bias that could seriously alter the results.

2 Participant numbers were deemed insufficient at 11 and the upper and lower CI limits were > 0.5 from the effect size (downgraded by 2 levels for imprecision).

Background

Many people with diagnosed medical conditions are dependent upon family members and informal caregivers (that is, a caregiver who is not paid (Levine 2010)), to provide support and care, usually in the home of the person needing care (Care Alliance Ireland 2015; International Alliance of Carer Organisations 2016). The care provided varies according to individuals' needs, with care categories defined as low (mainly companionship, with some caring assistance), medium (instrumental care such as cooking and shopping), medium with personal assistance (such as washing and dressing) and high (including low and medium level caring when the person receiving care cannot provide much assistance to the caregiver) (Care Alliance Ireland 2015). In many instances, informal carers find themselves in a caring role for which they are ill prepared (Coleman 2015; Levine 2013; Nalder 2012). Providing care may impact negatively on the caregiver from an emotional, physical, social, and financial perspective (Care Alliance Ireland 2010; Glendinning 2009; OECD 2011). Internationally, the focus of health care is to have people cared for in the community for as long as is possible. The aim is to shift to community‐based and patient‐centred paradigms of care for the treatment of chronic diseases (WHO 2006); and, where possible, prevent admission to secondary healthcare facilities. Unpaid or informal caregivers have been described as the backbone of the healthcare system (Care Action Network 2013; Levine 2010; OECD 2013); and worldwide they play a key role in the provision of care, saving billions in healthcare expenditure (Levine 2010; Navine‐Waliser 2002).

Description of the condition

The international literature suggests that caregiving impacts similarly on caregivers irrespective of geographical location or of the illness being experienced by the care‐recipient. In a UK study, Golics 2013 reported that caregivers caring for family members with a range of illnesses experienced worry, frustration, anger, and guilt. For some, adjustment to the role is difficult and requires significant emotional and life changes. This is reflected across the world with national studies from Japan (Oshio 2015), South Korea (Do 2015) and Canada (Penning 2015) highlighting the negative effects of caregiving on informal caregivers.

Family members providing unpaid care have been described “…as a hidden 'patient' group…” (Golics 2013, p.795). The need for professional support for caregivers has been reported and highlighted across a range of acute (i.e. time‐bound and responsive to treatment) and chronic (i.e. not time‐bound, non‐curable and susceptible to remission and exacerbation) conditions (Murrow 1996). This includes support for caregivers of people surviving complex illnesses (Czerwonka 2015), patients with cancers ( Heese 2013; Merckaert 2013; Mosher 2013), mental health problems (Gavois 2006), stroke (Cameron 2013), Parkinson’s disease (Oguh 2013), dementia ( Lilly 2012; Van Mierlo 2012b; Zwaanswijk 2013) and multiple sclerosis (Corry 2009). Golics 2013 argues that having access to people with the knowledge and skill to provide support, in particular emotional support, may ease the burden of caring. Burden is a multidimensional concept that can be viewed objectively, in terms of externally observable phenomena, such as the financial impact of caring, or subjectively, in terms of how it is perceived by the individual (Buhse 2008). This may include the experience of strain, stress, or load as a result of the caring role (Buhse 2008).

Although the impact of caregiving may be similar, how it is experienced by caregivers differs. Within caregiver groups such as caregivers of older persons (Unson 2016), intensive care survivors (ICU) (Foster 2003), and people with schizophrenia (Roick 2007), researchers have noted that gender, relationship to the patient (Foster 2003; Roick 2007; Unson 2016) level of contact with the patient (Roick 2007; Unson 2016), younger age (Unson 2016) and unemployment (Roick 2007) all influence how caregivers experience burden. McCabe 2009 further reported lower mood and quality of life in caregivers of people with motor neurone disease and Huntington’s disease compared to caregivers of people with Parkinson's disease and multiple sclerosis. Adjusting to the role of caregiver has been described as a non–linear or oscillating process (Greenwood 2010; Robinson 2005) that is continual (O’Shaughnessy 2010), gradual and occurs over time (Hasson 2010; Robinson 2005), with the adjustment process differing for caregivers within and across conditions (Cameron 2016; Davidson 2012; Smith 2004).

Description of the intervention

Healthcare professionals commonly communicate with care‐recipients and their family members by telephone. A number of research studies have evaluated use of the telephone only (Bakas 2009; Hartke 2003; Van Mierlo 2012b), or the telephone as a component of an intervention (Borman 2009; Piamjariyakul 2013; Sepulveda 2008; Tremont 2008; Van Mierlo 2012b). Some of the interventions are delivered by healthcare professionals and others are delivered by peers (Goodman 1990), or co‐facilitated by befriending volunteers (Charlesworth 2008). In this review, the focus is on evaluating the telephone only, as a means of delivering a support intervention, by healthcare professionals for caregivers of people with acute and chronic conditions. In this review, a telephone intervention is defined as an intervention that enables healthcare professionals to verbally communicate remotely with caregivers. A healthcare professional is a trained healthcare person who has received specific healthcare education and training in the management and care of people with diagnosed conditions, their family members, significant others or caregivers (e.g. nurses, medical doctors, social workers, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, counsellors/psychologists, and dieticians/nutritionists).

How the intervention might work

Professional support

Healthcare professionals provide services to patients and families/caregivers that includes direct care to people with diagnosed illnesses and indirect care, in the form of supportive advice, professional information, and psychosocial/educational support. In general, the benefits of professional support are likely to be dependent on the issues being addressed (Rosland 2008), and the readiness and receptivity of the person receiving the support (Hogan 2002; Toseland 1989). Reinhard 2008 demonstrated that professional support selectively reduces caregiver burden for those caring for people with mental health problems. Specific types of professional support, such as practical advice in managing behaviours, were found to be helpful in reducing objective burden (family arguments, missing days at work, household disruptions) (Reinhard 2008). Deek 2016 also reported favourably on family‐centred self‐care interventions, delivered by trained personnel, for adults living with chronic conditions and concluded that appropriate education and support should be provided by healthcare professionals (Deek 2016). Professionals have the education and training to provide emotional support to caregivers, helping ease the social isolation and emotional demands of caregiving (Mittelman 1996).

Strategies to improve caregiver outcomes

Caregiver support programmes help promote caregiver health by providing psychological support, information, and education to caregivers, while taking cognisance of caregivers’ limited time and resources (Gendron 2013). These psychoeducational programmes help carers develop skills in identifying signs of distress, managing symptoms, coping strategies/skills, and provide help with finding and accessing social support services (Riess‐Sherwood 2002). The telephone has been described as a good means of exchanging information, providing health education and advice, managing symptoms, recognising complications early, giving reassurance, and providing quality service (Thompson 2007).

Strategies to improve caregiver outcomes include providing education or information, assisting carers with problem‐solving, learning coping skills/behaviours, effective use of resources, seeking out social support, and identification of signs of distress (Riess‐Sherwood 2002). Coping strategies have been effective in improving the psychological health of caregivers of people with dementia (Selwood 2007). Likewise preparedness to care was found to reduce caregiver burden for caregivers of older persons (Zwicker 2010), and those with cancer (Scherbring 2002; Zwicker 2010). It was also found to ameliorate some aspects of role strain (Archbold 1990), and was the strongest predictor for lowering caregiver stress in stroke caregivers (Ostwald 2009). Failure to help caregivers master the skills and ability to manage their own health and well‐being during the early phases of caregiving may lead to greater difficulty integrating strategies, such as coping strategies, into daily life in later stages of the caregiving process (Riess‐Sherwood 2002). All of these strategies are amenable to delivery via the telephone. Reinhard 2008 contends that "...even a simple one‐to‐one telephone call may be effective in helping the caregiver..." (p.345). In this review, any strategy involving education or psychosocial support, or a combination of these, that focused on improving caregiver outcomes (see 'Types of outcome measures' for further detail) was considered.

Barriers to supporting caregivers

Many factors mitigate against the delivery of strategies to provide support for caregivers. Professional support services in the community often lack funding and availability; and, when available, may be insufficient to meet the needs of people with chronic illnesses (Rosland 2010). The large numbers of caregivers means that face‐to‐face interventions are unlikely to be feasible (Wilz 2016), because of distance (Hartke 2003) or cost, time, and inconvenience (Hartke 2003; Wilz 2016).

Factors that help overcome barriers to supporting caregivers

When distance, inconvenience, being homebound, or reluctance to leave the care‐recipient hinder face‐to‐face interventions (Hartke 2003), telecommunications and other media can be used (Badr 2016). Wilz 2016 concluded that the telephone is highly acceptable to family carers and reported on two qualitative studies which indicated that such interventions may meet caregivers' needs in respect of information, guidance, professional, and emotional support. Badr 2016 also suggested that telecommunications and other media interventions would enable caregivers to manage their own feelings and promote their ability to care. These findings support earlier qualitative research which reported that telephone support was a convenient and trouble‐free means of providing support to caregivers of people with dementia (Salfi 2005).

Reported benefits of telephone support interventions for caregivers

Previous research indicated that caregiver telephone interventions lead to positive outcomes (Chi 2015; Topo 2009). In a systematic review of telehealth tools and interventions to support caregivers, 20 of the 65 included studies reported on telephone‐based interventions (Chi 2015). Detailed results from individual telephone‐based studies were not reported in the review, rather, a collective summary of the findings of all technology‐based interventions, such as videoconferencing, telemetry and remote monitoring were presented, with the authors stating that 62 of the 65 included studies (95%) reported that caregivers had significantly improved outcomes (Chi 2015). In a systematic review of social support interventions for caregivers of people with dementia, Dam 2016 reported mixed findings from telephone interventions, but further analysis of the included studies revealed that various research designs, including the 'pre‐test post‐test' design, were used, and, in some instances, the telephone was only a component of the intervention upon which the conclusions were formed.

The benefits of any intervention are dependent on timing, readiness of the recipient, and the nature of the issues that need to be addressed. Research indicated that support may only be effective when the recipient perceived a need for the support (Melrose 2015). In this sense, the appropriateness of professional support is likely to be dependent on the required effects. Although we could not find any studies that explicitly explored the differences between the effectiveness of professional and peer support for caregivers, a study by Rosland 2008 found that support from family and friends impacted on different self‐management behaviours for people with diabetes to those impacted upon by professionals. This suggests that, for some self‐management behaviours, family support may be required; but professional support is more appropriate for others and that the type of support offered should be guided by the desired outcomes. In general, professionals are more likely than non‐professionals to affect outcomes that require therapeutic intervention (e.g. psychological functioning and personal change), while non‐professionals are more likely to positively change participation in informal social support networks (Toseland 1989).

Why it is important to do this review

The number of caregivers internationally varies according to overall population with figures varying from 60,000 in Finland to 43.5 million in the USA (International Alliance of Carer Organisations 2016). It is estimated that across the Organisation for Economic Co‐Operation and Development (OECD) countries, more than one in 10 adults provide informal care. Across the European Union (EU), 19 million people provide care of which 9.6 million provide at least 35 hours' care a week (Glendinning 2009). This number is expected to grow by 2030 (Glendinning 2009). While the financial contribution of informal caregivers to international reduction in healthcare expenditure is unknown, it is estimated that informal caregivers contribute an annual estimated national reduction in healthcare expenditure varying from EUR 20 billion in Sweden to USD 470 billion in the USA (International Alliance of Carer Organisations 2016). This is likely to reflect the contribution of estimated care hours provided by informal caregivers.

The contribution of family members is being increasingly recognised as important to the provision and management of care in chronic illness (Rosland 2010), and across the spectrum of illnesses (Coleman 2015; Haines 2015). However, uptake of the support provided may not be feasible for caregivers owing to geographical location, time, and cost. A report on a survey of eight European countries highlighted that, while the availability of support for caregivers of people with dementia was high, uptake was low, and utilisation may depend on the degree of accessibility of the support and caregivers' ability to perceive, seek, reach out, pay, and engage with the services (Lethin 2016). The telephone provides a mode of intervention delivery that has the potential to increase accessibility and affordability of support programmes.

Distribution of caregivers and telephone availability

As caregivers live in the community, are regionally and nationally dispersed, and are often in paid employment in addition to their unpaid caregiving role (International Alliance of Carer Organisations 2016; OECD 2011), face‐to‐face contact with people who can provide emotional support and advice is not always feasible. Attendance‐based interventions can be time‐consuming and expensive for the caregiver (Kaltenbaugh 2015; Ravenson 2016). Telephone communication is widely available internationally, with almost everyone having some form of access to a telephone including individuals living in remote settings (Lavender 2013). Pew Research Centre 2015 reported a median of 84% mobile phone ownership in emerging and developing countries with mobile phone ownership rates ranging from 47% to 97% in Pakistan and China, respectively. In 2011, of the 5.3 billion users of mobile phones worldwide, 3.5 billion were from developing countries (Shozi 2013), and it is projected that 70% of the world population will use smartphones by 2020 (Williams 2015), which will equate to more than 6.1 billion users (Lunden 2015). However, 10% of the world's population do not have access to mobile phones, with the majority of these from the rural areas of Asia and sub‐Saharan Africa (Consumer Technology Association 2015). Seventeen percent of people in sub‐Saharan Africa do not own a mobile phone but more than half of those people have, at times, access to a fixed line phone (Pew Research Centre 2015). Despite this, the mobile market growth rate in sub‐Saharan Africa is one of the highest worldwide (Deloitte 2012); and the growth in mobile phone networks has transformed communications in sub‐Saharan Africa, an area with the highest disease burden (Vos 2015).

Feasibility of technology‐based interventions

Research studies, in particular studies in stroke, dementia, and human immunodeficiency virus, indicate that technology‐based interventions can be feasibly implemented for caregivers of people with many different conditions (Brereton 2007; Herman 2006). Integrating telephone/mobile technology into current healthcare strategies provides a potential means for new ways for healthcare professionals to deliver care to patients and their caregivers (Deloitte 2014). Finkel 2007 argued that "...technology offers a cost effective and practical method for delivering interventions to caregivers” (p.443). Despite this assertion, there is little evidence currently of economic advantage (an aspect explored in this review) other than the suggestion that the need for healthcare professionals and caregivers to travel is eliminated, and caregiver access to existing resources and programmes is enhanced (Finkel 2007).

Factors that mitigate against implementation of findings to date

A number of factors mitigate against the usefulness of the findings from existing literature reviews and individual studies that included a telephone component. For example, in a literature review on technology studies to meet the needs of people with dementia and their caregivers, in which 15 of the included studies focused on caregiver interventions (Topo 2009), most of the interventions were complex interventions with the telephone as one component. As outcomes from the specific components of the intervention were not isolated or presented individually, the benefit of the telephone alone was difficult to determine. Failure to isolate or present findings from individual components of a multicomponent intervention can limit the application of such interventions. If the benefits from a multicomponent intervention could be realised with the application of any one component of the intervention, this needs to be highlighted so that healthcare resources are applied in an efficient and effective manner. Likewise, the potential benefits of telephone‐only support interventions, delivered by healthcare professionals to individuals or groups, need to be established. There is little empirical evidence to support the effectiveness of group interventions over interventions delivered to participants individually (Toseland 1989). While studies evaluated the effects of different modes of delivering interventions to groups, e.g. telephone versus face‐to‐face, we were unable to find any studies that evaluated the effects of a telephone group versus telephone one‐to‐one approach to intervention delivery, although these studies may be conducted in the future.

No Cochrane review was found that focused on telephone‐only support interventions for informal caregivers across a range of medical conditions. We found one Cochrane review that used the telephone for delivering a counselling intervention by healthcare professionals to caregivers of people with dementia only (Lins 2014). In a meta‐analysis of three trials in this review, depressive symptoms from telephone counselling alone were reduced and potential positive effects of other outcomes, including distress, burden, anxiety, quality of life, self‐efficacy, satisfaction, and social support, were also suggested. While the studies included in Lins 2014 were likely to be included in this review, we planned to analyse them along with telephone support interventions for a range of conditions, so improving our knowledge on the telephone's effectiveness as a means of delivering psychosocial support or education to caregivers of people across a broad spectrum of conditions. This Cochrane review differs from other Cochrane reviews on caregiver interventions (Aubin 2012; Chan 2011; Ellis 2010; Forster 2012; Legg 2011; Vernooij‐Dassen 2011), as, unlike these reviews, the main objective of our review was to determine whether or not the telephone alone as a mode of delivering a support intervention to caregivers of diagnosed illnesses was effective. Other Cochrane reviews that differ from our review include those by Candy 2011 and Lavender 2013. Candy 2011, who evaluated peer‐support interventions for caregivers, did not report any findings specific to the telephone. Lavender 2013 concluded that there was insufficient evidence to recommend routine telephone support for women accessing maternity services.

Two Cochrane protocols where telephone interventions were likely to be included as part of the review were identified (González‐Fraile 2015; Santin 2012). González‐Fraile 2015 focused on the provision of information, support, and training for informal caregivers of people with dementia and indicated that the telephone is a potential format for administering the intervention. Santin 2012 focused on psychosocial interventions for informal caregivers of people living with cancer, stating that interventions that included telephone counselling would be included. Although there may be some overlap between these two reviews and our review, the overall scope of this review is broader and has a specific focus on the telephone only as the mode of intervention delivery across a range of conditions.

In summary, the need for professional support for caregivers across a range of conditions is well established. As difficulties for caregivers attending face‐to‐face interventions have been highlighted (Badr 2016; Wilz 2016), telephone‐based interventions across caregiver groups provide a potentially important alternative. To date, there is no Cochrane review on the effectiveness of telephone support interventions alone, delivered by healthcare professionals, for caregivers across a range of medical conditions. It is therefore important to determine whether or not support interventions delivered by telephone are effective so that healthcare professionals can make informed decisions about whether or how to use the telephone in providing support to caregivers, should it be shown to be effective. Consequently, this review set out to determine the effectiveness of education or psychosocial support interventions, or a combination of both, delivered exclusively by telephone and by healthcare professionals, for informal caregivers of people with diagnosed illness. The results of this review have the potential to inform strategy on the use of the telephone as an easily accessible, low‐cost method to provide high‐quality care with the potential to benefit hundreds of thousands of informal caregivers worldwide. It can also contribute to the primary care agenda by delivering healthcare to caregivers and patients in remote and rural areas. In addition, the findings will assist with research, resource allocation, and future planning for the promotion and optimisation of the health and well‐being of informal caregivers.

Objectives

To evaluate the effectiveness of telephone support interventions, delivered by healthcare professionals, when compared to usual care or non‐telephone‐based support interventions for providing education and psychosocial support to informal carers of people with acute and chronic diagnosed illnesses, on these carers' quality of life, psychosocial, and physical well‐being. We aim, additionally, to evaluate the cost‐effectiveness of telephone interventions.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) (including cluster‐RCTs) and quasi‐RCTs. We included multi‐arm studies that used a pairwise comparison of groups that otherwise met the inclusion criteria for this review (Higgins 2011), and where data specific to the telephone component of the intervention could be extracted in isolation. We excluded studies where the caregivers and care‐recipients received the intervention together or caregivers were only included if they chose to take part in the intervention which was offered to the care‐recipient. We also excluded cross‐over trials as there is a high risk of carry‐over effects from one intervention to another (Higgins 2011).

Types of participants

We included informal adult caregivers, defined as persons aged 18 years or over, caring for adult individuals with a diagnosed illness and in receipt of telephone intervention support from a healthcare professional. For the purpose of this review, a caregiver was defined as a person (family member, friend, or significant other) who provides personal help (support or care) for a person with an acute or chronic illness, and was not a paid healthcare provider. Caregivers are also commonly referred to as 'carers' in the literature, and are used interchangeably in this review. An acute illness was defined as a diagnosed condition lasting less than six months and a chronic illness was defined as a diagnosed condition lasting for six months or more. We included caregivers of people with both acute and chronic illnesses because categorisation of conditions can be difficult. Acute conditions can become chronic and chronic conditions can have acute episodes of illness. Many patients have multiple conditions and may have an acute condition superimposed upon a previously diagnosed chronic condition. In this context, separation of diseases into acute and chronic categories, or exclusion of one category from the review, did not seem appropriate, as the experiences and needs of caregivers were not likely to be neatly divided along these lines. The inclusion of both acute and chronic conditions therefore enabled us to capture and consider studies across the range of illnesses impacting on caregivers in the community.

We included telephone support interventions delivered by healthcare professionals to caregivers of people with a range of diagnosed illnesses who were living in a hospital, residential care, or in the community. The following provides an indicative list of examples, based on author familiarity with the subject area and referenced sources, as available. These examples of condition categories are intended to be illustrative rather than exhaustive.

Complex critical illness survivors (i.e. people who need caregivers on the path to recover from the intensive care unit to the home environment).

Mental health: severe mental illnesses (e.g. schizophrenia, depression, bipolar affective disorders) (Vermeulen 2015).

Neurological conditions (e.g. dementia, epilepsy, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson's disease, stroke, traumatic brain injuries, Huntington's disease, headache disorders, neuro‐infections, pain associated with neurological disorders) (WHO 2006).

Respiratory conditions (e.g. asthma, chronic obstructive airways disease).

Cardiac conditions (e.g. congestive heart failure, myocardial infarction).

Renal conditions (e.g. renal failure).

Orthopaedic conditions (e.g. hip fractures, spinal injuries).

Musculoskeletal (e.g. degenerative osteoarthritis).

Infections (e.g. HIV/AIDS).

Haematological conditions (e.g. post‐bone marrow transplant).

Endocrine (e.g. diabetes 1 and 2).

Alcohol, drug or substances issues/misuse.

Cancer: any category.

Terminal illness: due to any of the above conditions.

Older persons: frail older persons or older persons with any of the above conditions.

People with comorbidity or multimorbidity.

Types of interventions

We included all telephone support interventions delivered by healthcare professionals that provided education or psychosocial support or a combination of these for informal caregivers. Telephone interventions where the first session was an introductory session either delivered by telephone or face‐to‐face and where all remaining sessions were delivered by telephone were included. Accordingly, we excluded all caregiver interventions that were not telephone‐based, telephone interventions delivered by non‐healthcare professionals and telephone interventions targeted towards paid caregivers, patients, people living in the community who were not informal caregivers, and healthcare professionals. Neither did we include interventions that included the telephone as a component of a multicomponent intervention where the findings for the telephone component of the interventions could not be isolated. Telephone interventions with more than one face‐to‐face session or where the first face‐to‐face session followed an overall introductory session to the intervention were also excluded.

We included trials that compared a telephone support intervention delivered by a healthcare professional with either ‘usual’ care (as defined by the study's authors, and described in the Characteristics of included studies table), or a support intervention delivered by a healthcare professional that was not telephone‐based (for example, online or face‐to‐face delivery at the individual or group level), analysing these comparisons separately. Educational, psychosocial, and combined psychosocial educational interventions were included. The term 'psychosocial interventions' refers to the cognitive, behavioural and/or social mechanisms of action, e.g. counselling, psychoeducation, behavioural and cognitive intervention and social support, that aim to improve the psychosocial and physical well‐being of carers of people with chronic conditions.

Educational interventions, which in many instances include information provision, are often more difficult to pin down and define. For the purposes of this review, we categorised an education intervention as one in which information was provided for the purpose of increasing the carer's factual knowledge, as well as interventions that included a component that ensured that the carer understood the information given and could put it into action (Mahan 1963), and/or where the intervention was defined or described as an education intervention by the trial/study authors. The following operational definitions were used to identify papers for inclusion in our review:

A healthcare professional was defined as a registered healthcare practitioner, who might or might not be a member of the wider clinical team, who had received an education or training qualification and who provided telephone education and psychosocial support to caregivers. This included nurses, social workers, medical doctors, counsellors, psychologists, and other related allied healthcare professionals.

A telephone intervention referred to any intervention, delivered via the telephone, with an education or psychosocial (mental, emotional, social, or spiritual) focus, or a combination of these, that was designed to provide knowledge, advice, or help to caregivers in order to enable them to manage their own well‐being or that of the person they cared for. This support could be provided individually or in group format. For the purpose of this review, telephone interventions included calls from any device that enabled audio communication between healthcare professionals and caregivers, including calls made using landlines, mobile phone devices, and devices that enabled the use of Skype or other applications that facilitated verbal communication between healthcare professionals and caregivers. Telehealth interventions that provided online education or interventions other than telephone calls between healthcare professionals and caregivers were excluded.

Types of outcome measures

The following outcomes, where reported, were assessed at several time points, reflecting the possible changes in caregiver outcomes over time. All outcomes were assessed at the end of intervention delivery and at short‐term (≤ 3 months), medium‐term (> 3 to ≤ 6 months) and longer‐term time points (> 6 to 12 months) following intervention delivery.

Primary outcomes

Caregiver quality of life (QoL) as measured by the trial/study authors or using a standardised/validated measurement instrument (e.g. SF 36, WHOQoL or caregiver QoL index).

Caregiver burden as measured by the trial/study authors or using a standardised/validated measurement instrument (e.g. Caregiver Reaction Assessment, Carer Burden Inventory, or Caregiver Strain Index).

Secondary outcomes

The following secondary outcomes, where reported, were measured.

Skill acquisition (preparedness to care, caregiver competence, problem‐solving).

Psychological health (depression, anxiety, stress, coping).

Knowledge and understanding (knowledge).

Health status and well‐being (physical health, self‐efficacy, social activity).

Family functioning.

Satisfaction (satisfaction with the intervention, perceived satisfaction with practical or other supports such as technical aids, peer support, or self‐help groups).

Economic outcome data as reported from cost benefit analysis, cost‐effectiveness analysis, cost utility analysis.

Unintended outcomes that could be attributed to the intervention were considered adverse events. These included any worsening of the above outcomes in the intervention group, as reported by the study authors or as evident in worsening at the end of intervention from baseline (pre‐intervention) measurement, where provided in the included studies, in particular, anxiety and depression. Reported incidents of suicide ideation and suicide were also considered adverse events.

Outcomes reported in the included studies were categorised to the groupings above by two authors working independently. Had any differences in categorisation occurred, they would have been resolved by involvement of a third author, but this was not necessary.

The results of the following outcomes, where reported are presented in a 'Summary of findings' table (Table 1 and Table 2).

Caregiver quality of life.

Caregiver burden.

Psychological health (depression, anxiety, stress, coping).

Satisfaction (satisfaction with the intervention).

Suicide ideation and suicide.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following electronic databases using a combination of appropriate keywords and controlled vocabulary terms.

The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in the Cochrane Library (searched on 3 April 2017, updated 16 November 2018);

MEDLINE [Ovid] (1946 to 3 April 2017, updated 16 November 2018);

Embase [Ovid] (1947 to 3 April 2017, updated 16 November 2018);

PsycINFO [Ovid] (1597 to 3 April 2017, updated 16 November 2018);

ProQuest Dissertations and Theses A&I [ProQuest] (1743 to 18 April 2017, updated 16 November 2018);

CINAHL Complete [Ebsco] (1937 to 3 April 2017, updated 16 November 2018).

The strategy for MEDLINE [Ovid] is presented in Appendix 1. This strategy was tailored to the other databases, as appropriate, and provided in Appendix 2; Appendix 3; Appendix 4; Appendix 5; Appendix 6; Appendix 7; and Appendix 8. No language or date restrictions were applied.

Searching other resources

To identify any further potentially eligible studies that might not have been captured in our search of the electronic databases, we searched the grey literature database Open Grey and manually searched the reference lists of the studies included in our review. We also searched online trial registers, including the World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP), searched on 18 April 2017, and ClinicalTrials.gov, searched on 6 June 2017, for ongoing and recently completed studies. We contacted experts in the field and authors of included studies for advice as to other potentially relevant studies. In addition, we searched the following websites: Grey Matters, primarily for details of international Health Technology Assessment agencies; RIAN, for Irish open access research; various caregiver associations (Care Alliance Ireland, Canadian Caregiver Coalition, Carers UK, Carers Friends UK, Crossroads, Eurocarers, Family Caregiver Alliance (US), New Zealand Carers, Patient View, The Princess Royal Trust for Carers, International Caregivers Association); and conference links (Dementia Care Events ‐ International Caregivers Association, Caregiver Intervention database – The Rosalynn Carter Institute for Caregiving and the US Department of Veteran Affairs, Health Services Research & Development).

Data collection and analysis

Data collection was conducted in accordance with the published protocol (Corry 2017). Due to the small number of studies identified for each intervention type, duration, and caregiver group, data were analysed by outcome at each outcome time point following intervention delivery (end of intervention, short‐term (≤ 3 months), medium‐term (> 3 to ≤ 6 months) and longer‐term time points (> 6 to 12 months)).

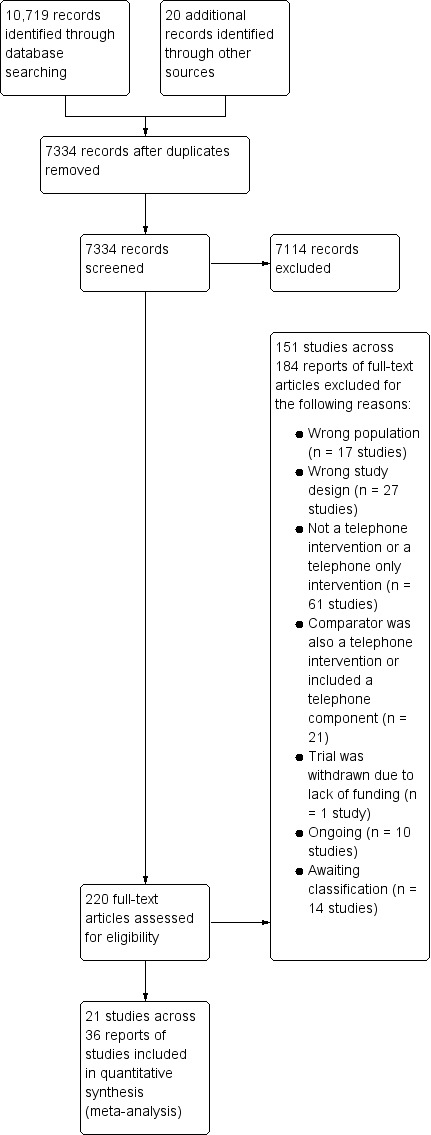

Selection of studies

All database search results were merged using reference management software EndNote and duplicate citations were removed. Two pairs of two review authors (MC & KN and MC & SB) screened the titles and abstracts identified from the searches to determine those that met the inclusion criteria. Each pair independently screened half of the selected titles and abstracts, with MC screening all citations. We retrieved the full text of any papers identified as potentially relevant by at least one author. The same pairs of reviewers independently screened full‐text articles for inclusion or exclusion, with discrepancies resolved by discussion and by consulting a third reviewer (VS) as was necessary, to reach consensus. Studies were not excluded on the basis of non‐measurement/reporting of our reviews’ prespecified outcomes, where all other inclusion criteria were fulfilled. All potentially relevant papers excluded from the review at this stage are listed, with reason(s) for exclusion, in the 'Characteristics of excluded studies' table. We also provided citation details and any available information about ongoing studies, and collated and reported details of duplicate publications, as each study (rather than each report) was the unit of interest in the review. We reported the screening and selection process in an adapted PRISMA flow chart (Mohler 2009) (Figure 1).

1.

Study flow diagram.

Data extraction and management

The same pairs of review authors extracted data independently from the included studies. For the included study conducted by one of the review authors (Corry 2015), data extraction was undertaken by other review authors. Clear decision rules based on participants, interventions, comparators, and outcomes were developed to assist the reviewers prior to commencing data extraction. Any discrepancies were resolved by discussion until consensus was reached, or through consultation with a third reviewer (VS) as was necessary. If disagreements had remained unresolved, the study authors would have been contacted for study details that would lead to a resolution of the disagreement; however, this was not necessary.

We developed and piloted a data extraction form using the Cochrane Consumers and Communication Review Group Data Extraction Template (available at: cccrg.cochrane.org/author‐resources). We extracted the following data: aim of study, location, study design and methods, medical condition of care‐recipient, intervention type and detail, comparison, number and detail of participants, ethical approval, risk of bias, outcomes of interest, data and results, and funding sources.

As recommended by Herbert 2005, we noted and recorded any reported quality descriptions or rating by the study authors. We modified Section 5 of the data extraction form to ensure that we extracted data that allowed us to evaluate the quality of the intervention in terms of the framework used to develop the intervention, stated aim/goal of the intervention, match between intervention and stated goal, intensity of the intervention in terms of frequency of delivery/receipt (weekly, bi‐weekly, two‐weekly, monthly) and duration (in months), and fidelity to the intervention in terms of the extent to which it was delivered in a consistent manner (Bellg 2004; Mars 2013), and in accordance with the intervention trial protocol (Gearing 2011; Mars 2013). The extent to which contamination was minimised and monitored, the selection and standardisation of training the interventionists, standardisation and monitoring the delivery of the intervention, monitoring receipt of the intervention and the ability of participants to use the skills are all important aspects of fidelity which were evaluated (Bellg 2004; Mars 2013; Resnick 2005). We devised and piloted a quality‐assessment instrument based on Section 5 of the data extraction form, which enabled us to categorise the interventions as low‐, medium‐, or high‐quality based on the extent to which it was developed and delivered in accordance with best practice guidelines (Bellg 2004; Corry 2010; Gearing 2011; Mars 2013; MRC 2008).

One review author (MC) entered all extracted data into Review Manager 5 (RevMan 2014), and a second review author (VS) working independently, checked it for accuracy against the data extraction sheets.

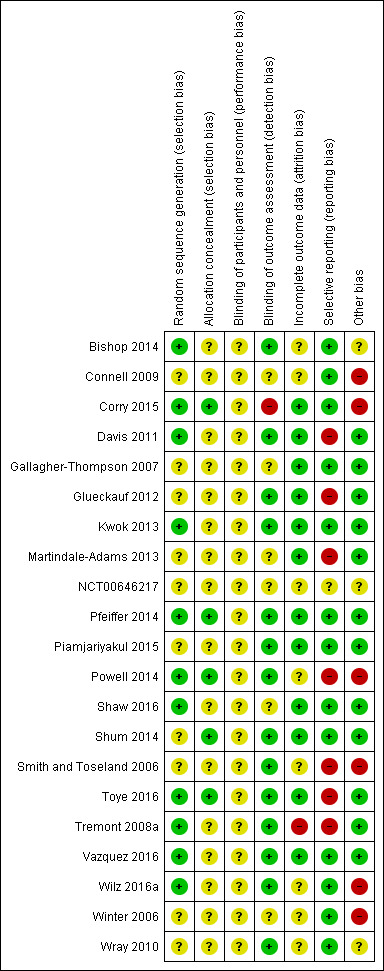

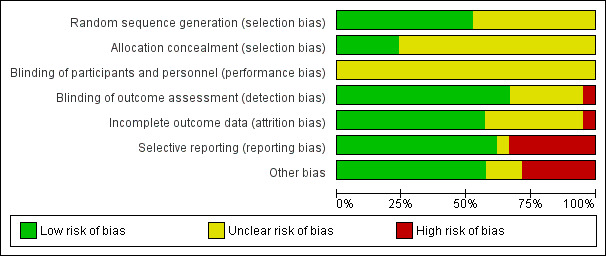

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed and reported on the methodological risk of bias of included studies in accordance with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011a) and the guidelines of the Cochrane Consumers and Communication Group (Ryan 2013), which recommend the explicit reporting of the following individual elements for RCTs: random sequence generation; allocation sequence concealment; blinding (participants, personnel); blinding (outcome assessment); completeness of outcome data; selective outcome reporting; and other sources of bias such as unbalanced groups and risk of contamination. We considered the 'risk of bias' domains separately for the different outcomes, and judged each outcome as high, low, or unclear risk of bias using the guidance provided by Higgins 2011a, and provided a quote or used information from the study reports to support our judgements for each domain provided in the 'Risk of bias' tables.

Studies were deemed to have the highest risk of bias if they were scored as high or unclear risk of bias on both sequence generation and allocation concealment and high or unclear on either risk of contamination, selective outcome reporting, or attrition bias domains, based on growing empirical evidence that these factors are particularly important potential sources of bias (Higgins 2011a). Blinding is not always possible at the point of intervention delivery and receipt due to the nature of the intervention, and, for this reason, lack of blinding of participants and personnel was not considered as a critical source of bias in this review and this domain was not rated as at high risk of bias.

In all cases, two review authors (MC & KN or MC & SB) independently assessed the risk of bias of included studies, with any disagreements resolved by discussion to reach consensus. For the lead review author's included study (Corry 2015), two other reviewers (KN & SB) assessed the study's risk of bias. We contacted study authors for additional information about the included studies, or for clarification of the study methods, as required. Had quasi‐RCTs been included in the review, we would have assessed and reported quasi‐RCTs as being at high risk of bias on random sequence generation; this was not necessary, however, as no quasi‐RCTs were included. If cluster‐RCTs had been included in the review, we would have assessed and reported the risk of bias associated with an additional domain: selective recruitment of cluster participants; this was not necessary, however, as no cluster‐RCTs were included in the review. For the one multi‐arm trial included in the review (Vazquez 2016), had the outcomes not been reported for each arm of the trial separately, we would have evaluated the risk of selective reporting of comparisons of intervention arms; this, however, was not necessary. 'Risk of bias' judgements for the included studies are presented in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

3.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Measures of treatment effect

For dichotomous outcomes, such as those that may have been reported on the Caregiver Strain Index (CSI)/Caregiver Burden Scale (CBS‐M), we had planned to analyse data based on the number of events and the number of people assessed in the intervention and comparison groups, and use these to calculate the risk ratio (RR) and 95% confidence interval (CI). As none of the included studies reported any of the review's prespecified outcomes in this way, RRs were not reported in the review. For continuous measures, we analysed data based on the mean, standard deviation (SD), and number of people assessed for both the intervention and comparison groups to calculate mean difference (MD) and 95% CI. If the MD was reported without individual group data, we used this to report the study results. Where more than one study measured the same outcome but used a different measurement scale, we calculated the standardised mean difference (SMD) and 95% CI using the inverse variance method in RevMan 2014.

Where a study reported on more than one outcome from an outcome category, and the outcomes were included in a meta‐analysis, we selected the outcome that the study authors had identified as being their primary outcome. Where no primary outcome had been identified, we selected the one specified in the study's sample size calculation. If there were no sample size calculations, we ranked the effect estimates of the outcomes (as presented in the study’s results) and selected the median effect estimate. Where there was an even number of outcomes, the outcome whose effect estimate was ranked n/2, where n is the number of outcomes, was selected. Results, where feasible, were reported at different follow‐up times: end of intervention, short‐term (following end of intervention to ≤ 3 months), medium‐term (> 3 to ≤ 6 months) and long‐term (> 6 to 12 months).

Unit of analysis issues

For multi‐arm trials, we extracted data from comparisons relevant to our review; i.e. we extracted data from study arms that compared the effects of telephone‐only interventions delivered by healthcare professionals to usual care or a support intervention delivered by healthcare professionals that was not telephone‐based, for caregivers of persons with diagnosed acute illness who were living in a hospital, residential care, or the community. To avoid a unit of analysis error, in accordance with Higgins 2011a guidelines, in the one multi‐arm trial included in the review (Vazquez 2016), because the intervention groups' data were analysed separately, we divided the numbers for the comparator group by half prior to analysis to avoid over‐counting of data. Although no cluster‐RCTs were included in the review, for future updates, where cluster‐RCTs are included, we will check for unit of analysis errors. If errors are found, and sufficient information is available, we will re‐analyse the data using the appropriate unit of analysis, by taking account of the intracluster correlation (ICC). We will obtain estimates of the ICC by contacting authors of included studies, or impute the ICC using estimates from external sources. If it is not possible to obtain sufficient information to re‐analyse the data, we will report effect estimates and annotate unit of analysis errors. If necessary, we will seek further expert statistical advice when analysing data from cluster trials in any future update of this review.

Dealing with missing data

We contacted study authors to obtain missing data (participant, outcome, or summary data), where it was necessary and appropriate to do so. For participant data, where possible, we conducted analyses on an intention‐to‐treat basis; otherwise, data were analysed as reported and noted as a potential source of bias in our 'Risk of bias' assessments. Studies of telephone interventions for caregivers are likely to have high loss to follow‐up, with attrition rates of up to 45% reported in intervention groups (Tremont 2008) and 65% for control groups (Glueckauf 2007). We reported on the levels of loss to follow‐up and assessed this as a source of potential bias where more than 40% loss to follow‐up on primary outcomes was reported and considered this high risk of bias. Following attempts to contact study authors, where we failed to obtain missing outcome data, the denominator for each outcome in each trial was the number randomised minus any participants whose outcomes were known to be missing; that is, we used the numbers as reported in the included study. For continuous data, where measures of central tendency and variance, for example, medians and standard errors, were sufficiently provided in a study report, we converted these to means and SDs where possible, using the appropriate formulae, and inputted these values accordingly. If means only were available, we used the SD from another study in the review for the same outcome, where it was appropriate to do so (Higgins 2008).

Assessment of heterogeneity

The included studies were analysed by outcome, irrespective of care‐recipients' condition or duration of the intervention, and by follow‐up time‐frames (end of intervention, short‐term follow‐up to ≤ 3 months, medium‐term > 3 to ≤ 6 months and long‐term > 6 to 12 months). Where studies were considered similar enough in terms of populations, intervention, outcome measures, and timing of outcome assessment to allow pooling of data using meta‐analysis, we assessed the degree of heterogeneity by visual inspection of forest plots and by examining the Chi² test for heterogeneity. Heterogeneity was quantified using the I² statistic. An I² value of 50% or more was considered to represent substantial levels of heterogeneity, but this value was interpreted in light of the size and direction of effects and the strength of the evidence for heterogeneity, based on the P value from the Chi² test (Higgins 2011a). Where there are few trials included in a meta‐analysis, the Chi² test has little power to detect heterogeneity. In such instances, a non‐significant result was interpreted with care and was not taken as evidence of no heterogeneity. Where we detected substantial clinical, methodological or statistical heterogeneity across included studies, we did not report pooled results from meta‐analysis but, instead, used a narrative approach to data synthesis. In this event, we attempted to minimise clinical or methodological heterogeneity by grouping studies that were similar in terms of populations, intervention features, and timing of outcome assessment in the analyses.

Assessment of reporting biases

We assessed reporting bias qualitatively based on the characteristics of the included studies (e.g. if only small studies that indicated positive findings were identified for inclusion), and if information that we obtained from contacting experts and authors of studies suggested that there were relevant unpublished studies. Had we identified sufficient studies (at least 10) for inclusion in a meta‐analysis for an outcome, we would have constructed a funnel plot to investigate small‐study effects, which may indicate the presence of publication bias; this, however, was not required. Had it been necessary, we would have formally tested for funnel plot asymmetry, with the choice of test made based on advice in Sterne 2011 and bearing in mind, when interpreting the results, that there may be several reasons for funnel plot asymmetry; we will consider this in any future updates, as necessary.

Data synthesis

Decisions on whether to meta‐analyse data were based on whether the included studies were similar enough in terms of populations, intervention, outcome measures, and timing of outcome assessment to ensure meaningful conclusions from a statistically pooled result. Owing to the observed variability in the caregiver groups, intervention types, duration of intervention delivery, and timing of outcome measurements, we used a random‐effects model for the meta‐analyses. Within the data categories, the main comparisons of the review were telephone support interventions delivered by healthcare professionals versus usual care and telephone support interventions delivered by healthcare professionals versus an alternative support intervention delivered by a healthcare professional that was not telephone‐based, for persons caring for adults with diagnosed illness. For outcomes that could not be meta‐analysed, we reported the results narratively according to timing of outcome assessment (end of intervention, short‐term completion of the intervention to ≤ 3 months; medium‐term > 3 to ≤ 6 months; and long‐term > 6 to 12 months).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Potential explanatory factors included type of condition (acute or chronic), caregiver group (diagnosis), intervention type (education or psychosocial support) and form of delivery (individual or group). There were insufficient included studies providing data for subgroup analyses; however, had there been sufficient studies, we would have conducted subgroup analyses separately on the primary outcomes for the following groups.

Intervention type (education, psychosocial, education and psychosocial combined).

Approach to telephone intervention delivery (group, one‐to‐one).

Caregiver characteristics (condition of the person being cared for grouped by category of condition (e.g. cardiac, cancer, or respiratory), gender, age (young/older caregivers), relationship to the care‐recipient).

Acute versus chronic illnesses.

Intervention duration (≤ 6 weeks, 7 to 12 weeks, 13 to 23 weeks, ≥ 24 weeks).

Sensitivity analysis

We had planned to examine the impact of studies that were categorised as high risk of bias on the outcomes in the overall meta‐analyses. However, most studies were rated as at high risk of bias overall, and, in many cases, meta‐analyses did not include a large enough number of studies to make such analysis meaningful. Similarly, we did not explore the influence of excluding unpublished studies and large studies on the overall effect size as planned, as this was not possible due to limited study numbers in meta‐analyses; we will, however, consider these methods for future updates.

‘Summary of findings’ table

We prepared a 'Summary of findings' table to present the results based on the methods described in chapter 11 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Schünemann 2011) and the guidelines of the Cochrane Consumers and Communication Group (Ryan 2016; Ryan 2016a). We presented the results for the major comparisons of the review, for each of the primary outcomes (quality of life and burden), psychological health (depression), satisfaction (with the intervention) and the potential harms/adverse events, as outlined in the Types of outcome measures section. Where more than one outcome was reported per category we used the methods described above to select outcomes for reporting in the ‘Summary of findings’ tables. We used the GRADE system to rank the quality of the evidence using the GRADEprofiler (GRADEpro) software (Schünemann 2011). In future updates, if necessary, we will provide a source and rationale for each assumed risk cited in the table(s), as needed. For outcomes where a meta‐analysis was not possible, we presented the results narratively.

Ensuring relevance to decisions in health care

The protocol and the review received feedback from at least one consumer referee in addition to a health professional as part of the Cochrane Consumers and Communication Group’s standard editorial process. During the development of the review, a caregiver provided comment; no changes were made to the review on receipt of the comments.

Results

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of ongoing studies; Characteristics of excluded studies and Characteristics of studies awaiting classification.

Results of the search

Electronic searches generated a total of 10,719 citations, of which 3,405 were duplicate citations across databases and were removed, resulting in 7,314 records. Searching of additional sources identified twenty further records for potential inclusion, resulting in 7,334 records for assessing for relevance on title and abstract. Of these, 7,114 citations were excluded following title and abstract screening, resulting in 220 for full‐text screening. Following full‐text review, a further 184 were excluded primarily because the comparator also included the telephone or a component of the comparator was telephone‐based, the intervention was patient‐focused, both the caregivers and care‐recipients received the intervention together, or the study did not use a randomised design (see Characteristics of excluded studies). Fourteen citations are awaiting classification (Au 2014; Bass 2017a; Chodosh 2015a; Chwalisz 2017; Gitlin 2018; Mavandadi; NCT00031265; NCT00183781; NCT00416078; NCT00869739; NCT02152033; NCT02215187; NCT02505425; NCT03260608) and ten are classified as ongoing studies (Gitlin 2013; Gopinah 2017; Heckel 2015; Mavandadi 2017; Nasiriani 2017; NCT00646074; NCT02505737; NCT02806583; Soellner 2015; Wilz 2018).

Included studies