Abstract

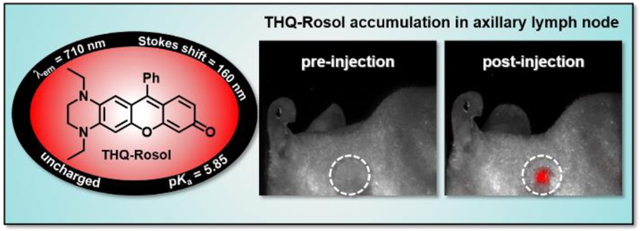

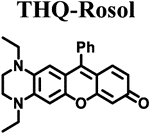

An optical molecular imaging contrast agent that is tailored toward lymphatic mapping techniques implementing near-infrared (NIR) fluorescence image-guided navigation in the planning and surgical treatment of cancers would significantly aid in enabling the real-time visualization of the potential metastatic tumor-draining lymph node(s) for needed surgical biopsy and/or removal, thereby ensuring unmissed disease to prevent recurrence and improve survival rates. Here, the development of the first NIR fluorescent rosol dye (THQ-Rosol) tailored to overcome limitations arising from the suboptimal properties of the generic molecular fluorescent dyes commonly used for such applications is described. In developing THQ-Rosol, we prepared a progressive series of torsionally-restrictive N-substituted non-NIR fluorescent rosol dyes based on DFT calculations, wherein we discerned high correlations amongst their calculated energetics, modeled N-C3’ torsion angles, and evaluated properties. We leveraged these strong relationships to rationally design THQ-Rosol, wherein DFT calculations inspired an innovative approach and synthetic strategy to afford an uncharged xanthene core-based scaffold/molecular platform an aptly-elevated pKa value alongside NIR fluorescence emission (c.a. 700–900 nm). THQ-Rosol exhibited 710 nm NIR fluorescence emission, a 160 nm Stokes shift, robust photostability, and an aptlyelevated pKa value (5.85) for affording pH-insensitivity and optimal contrast upon designed use. We demonstrated the efficacy of THQ-Rosol for lymphatic mapping with in vitro and in vivo studies, wherein it revealed timely tumor drainage and afforded definitive lymph node visualization upon administration and accumulation. THQ-Rosol serves as a proof-of-concept for the effective tailoring of an uncharged xanthene core-based scaffold/molecular platform toward a specific imaging application using rational design.

Graphical Abstract

The favorable prognosis and successful surgical treatment of many cancer types hinge on the accurate preoperative outlining (demarcation) and intraoperative assessment (surgical biopsy), delineation, and surgical removal (resection) of the malignant tumor tissue and potential metastatic tumor-draining lymph node(s) from visually-indistinguishable surrounding normal tissue.1–3 The use of an intratumorally-injected contrast agent that can drain into and accumulate within the sentinel and its down-stream lymph node(s) assists in improving patient survival rates by enabling their visualization in real-time for their needed preoperative demarcation, surgical biopsy, delineation, and potential subsequent complete resection.4,5 Optical molecular imaging contrast agents explored for use in lymphatic mapping applications that implement fluorescence imaging techniques such as fluorescence-guided surgery (FGS) currently involves a limited set of commonly-used generic molecular fluorescent dyes that primarily include fluorescein, methylene blue (MB), and indocyanine green (ICG) (Figure 1A and Table S1).6–10 As re purposed molecules, these generic molecular fluorescent dyes were neither originally designed nor intended for use toward lymphatic fluorescence imaging applications.11–13 As such, fluorescein, MB, and ICG possess inherent photophysical and physical properties that hamper their efficacy toward facilitating the real-time visualization of tumor-draining lymphatics for all stages of their needed pre- and intraoperative treatment, and thereby prevent the accurate identification, surgical biopsy, and complete resection of the potential metastatic tumor-draining lymph nodes that are crucial for ensuring unmissed disease in an effort to prevent recurrence and improve patient survival rates.14–16 In particular, these molecular fluorescent dyes collectively suffer from (i) exhibiting visible wavelength fluorescence emission (ca. 390–700 nm) which provide limited penetration depths in tissue, (ii) displaying a small Stokes shift (ca. < 40 nm) which reduces detection sensitivity due to promoting an elevated instrumentation source background, (iii) maintaining a charge which hinders their prompt tumor diffusion and timely drainage into the lymphatics following their administration, (iv) displaying a pH-sensitive fluorescence or submaximal response within tumor-draining lymphatic pH levels (pH 6.8–7.4), and/or (v) demonstrating poor photostability.4,17 The development of a molecular fluorescent dye designed to overcome these shortcomings could prove invaluable in the lymphatic mapping of applicable cancer types. Accordingly, a molecular fluorescent dye fashioned for this purpose would exhibit fluorescence emission in the near-infrared (NIR) optical imaging window (ca. 700–900 nm), a large Stokes shift (ca. > 80 nm), a pH-insensitive (steady) and maximal fluorescence response within the aforementioned pH levels, robust photostability, excellent water-solubility, and be uncharged, all of which would collectively enhance its efficacy toward affording the real-time visualization of tumor-draining lymphatics.4

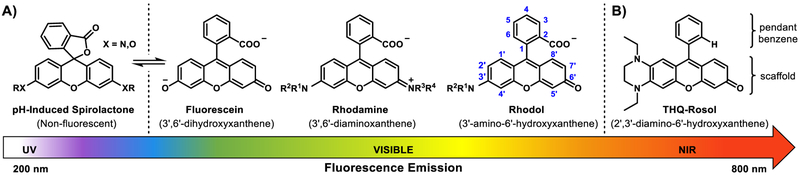

Figure 1.

Progressive exocyclic heteroatom modifications to the xanthene core structure of topologically-equivalent molecular fluorescent dyes that paved the way for the development of the first NIR fluorescent rosol dye, THQ-Rosol. A) General molecular platform of fluorescein-, rhodamine-, and rhodol-based fluorescent dyes, all of which consist of a charged non-NIR fluorescent xanthene core-based scaffold having a pendant benzene moiety with a charged 2-carboxylate group (-COO-) that promotes pH-induced spirolactonization and affords their scaffolds a pH-sensitive fluorescence response at more elevated pH levels than it otherwise demonstrates when without it.18–20 B) Molecular platform of rationally-designed THQ-Rosol, which consists of i) an uncharged NIR fluorescent scaffold that evolves from the non-NIR scaffold that also underlies the rhodol molecular platform and ii) a pendant benzene moiety without a charged 2-carboxylate group to afford an inherently uncharged molecular platform, preclude pH-induced spirolactonization, and afford the scaffold a steady maximal NIR fluorescence response at more elevated pH levels than it would otherwise demonstrate when a charged 2-carboxylate group is present.

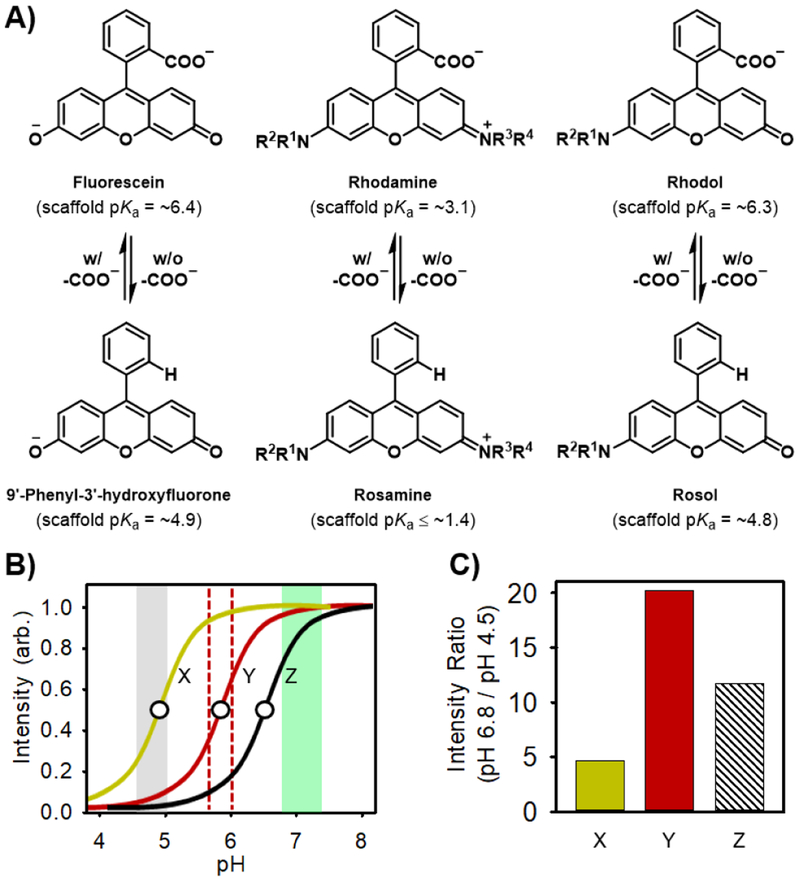

The rhodol molecular platform is a topologically-equivalent hybrid of the fluorescein and rhodamine molecular platforms and serves as an enhanced base structure for the development of fluorescence imaging constructs due to consisting of, in part, an uncharged underlying xanthene core-based scaffold that affords favorable physical and photophysical properties for bioimaging applications, which are much unlike its parent molecular congeners whose charged underlying xanthene core-based scaffolds afford photobleaching, limited cell permeability, and/or permanent intracellular retention (Figure 1A).21–24 All else aside, the rhodol molecular platform is yet similar to the fluorescein and rhodamine molecular platforms in that it too consists of a pendant benzene moiety with a charged 2-carboxylate group (-COŌ), which imparts an increased pKa value of ~1.5 pH units to its respective underlying scaffold (Figure 2A).21,25,26 As such, this physical effect affords its scaffold a pKa value of ~6.3.21,27 The resultant pKa value affords the rhodol molecular platform a pH-sensitive and/or submaximal fluorescence response upon its use in environments having a pH level of less than ~7.4, such as those of tumor-draining lymphatics (pH 6.8–7.4) (Figure 2B). With its identical underlying xanthene core-based scaffold to that which underlies the rhodol molecular platform, but having a pendant benzene moiety without a charged 2-carboxylate group, the rosol molecular platform is well-suited for use in such types of environments because its cross-platform scaffold demonstrates a pH-insensitive and maximal fluorescence response throughout those lower pH levels due to maintaining a lower pKa value of ~4.8.25,28 As an uncharged small-molecule that is water-soluble, the rosol molecular platform could readily lend itself to unrestricted cell permeability and limited intracellular retention. However, its non- NIR fluorescent scaffold and lower pKa value could not afford both the NIR fluorescence emission and contrast levels that are needed for its use in the deep-tissue fluorescence imaging of tumor-draining lymphatics, as non-NIR fluorescence emission wavelengths provide only topical penetration depths and its current pKa value of ~4.8 would provide suboptimal contrast between the significant overlapping background fluorescence response (ca. 50%) it would exhibit between if it demonstrated appreciable residual retention within tumor tissue after being administered (e.g., in acidic subcellular compartments) and after having drained into the lymphatics (Figure 2C).29 Tuning the physical and photophysical properties such that its xanthene core-based scaffold affords both a NIR fluorescence emission wavelength and an aptly-elevated pKa value of ~5.8–6.0 to better situate its off-on fluorescence intensity-pH profile would provide the rosol molecular platform with optimum viability for deep-tissue fluorescence imaging of tumor-draining lymphatics by being tailored to concurrently afford a steady maximal NIR fluorescence response and optimal contrast, as it could provide minimal overlapping background fluorescence response if it demonstrated any appreciable residual retention within tumor tissue shortly after being administered.

Figure 2.

Molecular platform of 9’-phenyl-3’-hydroxyfluorone-, rosamine-, and rosol-based fluorescent dyes, their analogues having a pendant benzene moiety with a charged 2-carboxylate group (-COO-), each respective initial pKa value, and the off-on fluorescence intensity-pH profile of the molecular platforms having a 3’- amino-6’-hydroxyxanthene-based scaffold and the maximum contrast level they would afford upon use toward visualizing tumor- draining lymphatics. A) The presence of the charged 2-carboxylate group imparts an increased pKa value to their respective underlying xanthene core-based scaffold. B) The off-on fluorescence intensity- pH profiles of a generic rosol (X) and rhodol (Z) dye with a pKa value of ~4.8 and ~6.3, respectively, and a proposed rosol dye (Y) designed with a pKa value of 5.8–6.0. The dashed red lines circumscribe the pH level range that a fluorescent molecular dye having a pKa value within them would afford optimal contrast upon use in lymphatic mapping applications. The circle identifies the pKa value. C) Only the proposed rosol dye (Y) designed to have a pKa value of 5.8–6.0 would afford a steady maximal response and optimal contrast. A solid or striped intensity ratio bar indicates that the dye would be either pH-insensitive or pH-sensitive when within tumor-draining lymphatic pH levels (pH 6.8–7.4), respectively.

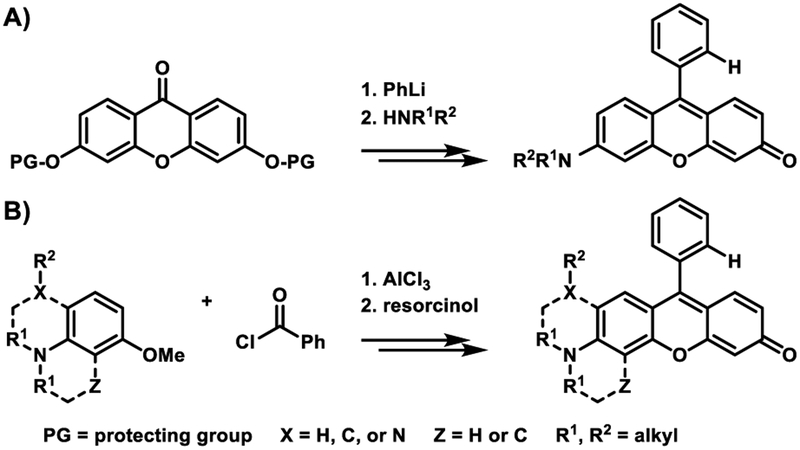

Only scant information involving modifications to the photo- physical and/or physical profile of the xanthene core-based scaffold when underlying the rosol molecular platform is currently available, presumably due to the numerous constraints of the conventional synthetic strategy that allow for its direct preparation (Figure 3A). However, the literature is replete with examples having made use of the limited number of standard approaches for altering the pKa value and/or fluorescence emission wavelength of the xanthene core-based scaffolds that underlie the fluorescein, rhodamine, and rhodol molecular platforms, namely site-specific halogenation, π-system elongation, and endocyclic heteroatom substitution. Unfortunately, none of these approaches i) allow for the direct preparation of an uncharged xanthene core-based scaffold/molecular platform that provides fluorescence emission beyond 700 nm and/or ii) provide a means for directly modifying the xanthene core-based scaffold when as an integrated component of these molecular platforms such that it elevates its pKa value. Moreover, as these approaches largely derive from generalized empirical bases rather than rational design, their use permits only crude and un predictable adjustments to the fluorescence emission wavelength and/or pKa value of their xanthene core-based scaffolds. Taken together, both a new approach and synthetic strategy for directly modifying and allowing for the direct preparation, respectively, of an uncharged xanthene core-based scaffold/molecular platform such that it affords a NIR fluorescence emission wavelength and/or an elevated pKa value that each derive from a quantitative basis could significantly advance both the efficient development and the efficacy of fluorescent rosol dyes toward specific imaging applications.

Figure 3.

Generalized synthetic strategies that allow for the direct preparation of fluorescent rosol dyes. A) Conventional synthetic strategy that affords only non-NIR (3’-amino-substituted) fluorescent rosol dyes of limited diversity. B) Newly-established synthetic strategy that affords non-NIR and NIR (2’,3’-diamino-substituted) fluorescent rosol dyes of broad diversity.

Herein, we describe the design, synthesis, and evaluation of the first NIR fluorescent rosol dye (THQ-Rosol), which serves as a proof-of-concept for the effective tailoring of an uncharged xanthene core-based scaffold/molecular platform toward lymphatic mapping applications using rational design (Figure 1B). As part of our efforts in efficiently developing THQ-Rosol, we designed a small progressive series of rotationally-constrained N-substituted non-NIR fluorescent rosol dyes (3’-amino-substituted) based on density functional theory (DFT) calculations with increasingly torsionally-restrictive alkyl substituents appended to the exocyclic N-heteroatom of their underlying xanthene core-based scaffold in order to examine the relationships amongst their calculated energetics, modeled N-C3’ torsion angles, experimentally-determined pKa values, and measured photophysical properties. DFT calculations provided the energy of the highest occupied and lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (EHOMO and ELUMo) values of each N-substituted fluorescent rosol scaffold, wherein the versatility of our synthetic strategy also allowed for the preparation of the non-NIR fluorescent rosol dyes as designed (Figure 3B). In discerning high correlations amongst their calculated energetics, modeled N-C3’ torsion angles, and evaluated properties, we determined that fluorescent rosol dyes can be designed in a quantitative manner with the fluorescence emission wavelength and pKa value of their scaffolds predetermined and/or finely tuned simply based on their calculated and modeled values. We leveraged those strong relationships to rationally design THQ-Rosol, wherein DFT calculations inspired an innovative approach and synthetic strategy for extending the fluorescence emission wavelength and elevating the pKa value and of an uncharged xanthene core- based scaffold such that it would provide the first NIR fluorescent rosol dye (2’,3’-diamino-substituted) with both a finely- tuned NIR fluorescence emission wavelength and an aptly-elevated pKa value that fittingly situates its off-on fluorescence intensity-pH profile to provide optimal contrast for deep-tissue fluorescence imaging of tumor-draining lymphatics. High correlations between the similarly calculated, modeled, and evaluated properties of THQ-Rosol further bolstered the utility of computationally-efficient DFT calculations and molecular modeling in serving as a simple model that can afford a priori the determination and fine-tuning of the fluorescence emission wavelength and pKa value, respectively, for the efficient development and efficacy of both non-NIR and NIR fluorescent rosol dyes toward specific imaging applications. We performed in vitro and in vivo comparative studies with THQ-Rosol to assess its efficacy in affording timely tumor drainage and definitive lymph node visualization with excellent contrast upon its administration and accumulation, respectively. In all, the development of THQ-Rosol both represents a rationally-designed optical molecular imaging contrast agent based on the rosol molecular platform that is well-suited for lymphatic mapping applications and provides a compelling means to fashion non-NIR and NIR fluorescent rosol dyes toward specific imaging applications that could prove effective for other similar fluorescent molecular platforms having a xanthene core-based scaffold.

Experimental Section

DFT Calculations.

DFT calculations using the hybrid exchange-correlation function B3LYP with the 6–31G(d) basis set as implemented in Gaussian 09W Rev. A.02 were performed on the truncated N-substituted xanthene core-based scaffold underlying each fluorescent rosol dye to best represent the electronic contributions influencing the ground and excited state energies. Many starting geometries were used to ensure the optimized structure corresponds to a global minimum.

Chemicals and Reagents.

Unless noted otherwise, all chemicals were obtained from Aldrich, Fisher, TCI America, Alfa Aesar, or Combi-Blocks and used without further purification. Flash chromatography was performed with 32–63 mm silica gel.

Spectroscopy.

NMR spectra were obtained on an Agilent 400-MR NMR Spectrometer. All HRMS analyses were completed using positive-ion mode electrospray ionization with an Apollo II ion source on a Bruker 12 Tesla Apex Q FTICR-MS. Absorption spectra were recorded using an Agilent 8453 UV- visible Spectrophotometer at 25°C. Steady-state fluorescence spectroscopy was performed on a Horiba Jobin Yvon, Inc. PTI Quantamaster 400 (QM-400) spectrofluorometer.

In Vivo Imagingc.

All experimental procedures involving animals were approved by the Stanford University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). For tumor models, cells (0.5 × 106 cells; 150 μL of serum-free media) were subcutaneously injected on the back of female nu/nu mice (age 17–18 weeks; Charles River Laboratories) and allowed to grow for 6 weeks. Tumor size was monitored by calipers and bioluminescence imaging. Animals were anesthetized with 2% isoflurane in O2 and kept on a heating pad during imaging. Imaging was performed on a CRi, Inc. Maestro™ spectral fluorescent imager with a 503–555 nm excitation filter and 580 nm long-pass emission filter for THQ-Rosol and a 710–760 nm band-pass excitation filter and 800 nm long-pass emission filter for ICG.

Results and Discussion

To efficiently develop an optical molecular imaging contrast agent that is tailored toward lymphatic mapping applications based on the rosol molecular platform using a quantitative basis, we initially designed an appropriate panel of non-NIR fluorescent rosol dyes with the aid of DFT calculations to systematically examine the relationships amongst the calculated energetics and modeled N-C3’ torsion angles of their underlying xanthene core-based scaffolds and accompanying evaluated spectroscopic, photophysical, and physical properties. Although subsequently discussed, we present the relevant results of THQ-Rosol that we later developed and evaluated next to those of the non-NIR fluorescent rosol dyes for easy comparison.

DFT Calculations and Molecular Modeling.

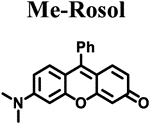

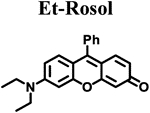

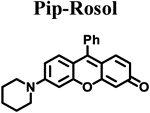

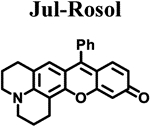

Calculated molecular orbital energy values helped guide the design and selection of an appropriate panel of non-NIR fluorescent rosol dyes. We selected the non-NIR fluorescent rosol dyes having a dimethylamino (Me), diethylamino (Et), piperidino (Pip), and julolidino (Jul) moiety that we denote as Me-Rosol, Et-Rosol, Pip Rosol, and Jul-Rosol, respectively, which provided a general trend of decreasing molecular orbital energy gap (ΔE) values ranging from 0.11314 to 0.11052 hartrees via an accompanying relatively weak general trend of increasing EHOMO values ranging from −0.18814 to −0.18333 hartrees (Table 1). Their modeled N-C3‘ torsion angle (θ) revealed a general trend of increasingly torsionally-restrictive alkyl substituents appended to the exocyclic N-heteroatom of the underlying xanthene core- based scaffold which accompanied their general trend of decreasing molecular orbital energy gap values. Accordingly, Jul- Rosol maintained the smallest modeled N-C3’ torsion angle (7.45°) and molecular orbital energy gap value (0.11052 har trees) amongst the designed non-NIR fluorescent rosol dyes.

Table 1.

Calculated, Modeled, and Measured Properties of Non-NIR Fluorescent Rosol Dyes and THQ-Rosol.

| Compound |  |

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ELUMO (hartrees)a | −0.07500 | −0.07520 | −0.07795 | −0.07281 | −0.06856 |

| EHOMO (hartrees)a | −0.18814 | −0.18811 | −0.19086 | −0.18333 | −0.17245 |

| ΔE (hartrees) | 0.11314 | 0.11291 | 0.11291 | 0.11052 | 0.10389 |

| Torsion angle N-C2’ (θ)b | - | - | - | - | 12.21° |

| Torsion angle N-C3’ (θ)b | 18.57° | 14.86° | 12.01° | 7.45° | 10.34° |

| λabs (nm)c | 520 | 524 | 525 | 540 | 550 |

| λem (nm)d | 557 | 558 | 563 | 574 | 710 |

| Stokes shift (nm) | 37 | 34 | 38 | 34 | 160 |

| Photostability (I/I0)e | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.98 | 0.99 |

| ε (M−1 cm−1) | 46,136 | 42,629 | 42,460 | 30,420 | 29,382 |

| Φflf | 0.182 ± 0.007 | 0.098 ± 0.001 | 0.048 ± 0.001 | 0.414 ± 0.025 | 0.029 ± 0.001 |

| Brightness (M−1cm−1) | 8.4 | 4.2 | 2.0 | 13 | 0.85 |

| pKag | 4.84 | 4.97 | 4.95 | 5.76 | 5.85 |

DFT calculations were performed on the truncated scaffolds of each modeled fluorescent rosol dye to obtain their respective ELUMO and EHOMO values.

The modeled torsion angle is the offset from planarity (in degrees) of the alkyl substituent that is appended to the C2’- or C3’-nitrogen atom in relation to their respective xanthene core-based scaffold.

Measured maximum absorption wavelength of the fluorescent rosol dye (20 μM) in aqueous buffer (50 mM phosphate, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4).

Measured maximum emission wavelength of the fluorescent rosol dye (20 μM) upon exciting it at its respective λabs in aqueous buffer (50 mM phosphate, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4).

I0 is the measured initial fluorescence intensity of the fluorescent rosol dye and I is its measured fluorescence intensity after 30 min of continuous photoirradiation.

Φfl is the measured fluorescence quantum yield.

pKa values were determined using 20 μM of the fluorescent rosol dye in aqueous buffer (50 mM phosphate, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4). Error in Φfl and pKa values are ±5% based on triplicate measurements.

Synthesis.

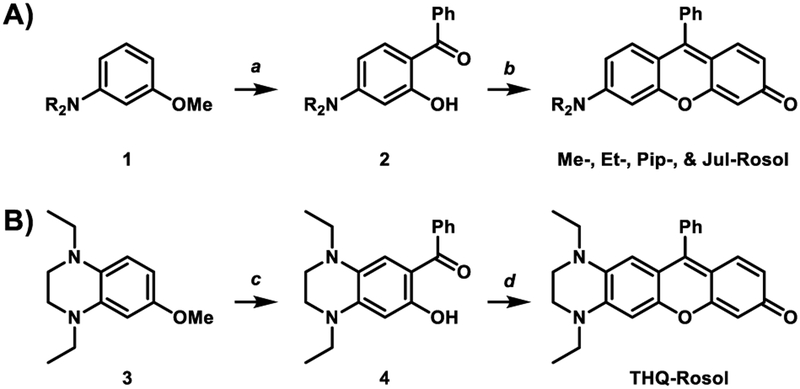

Non-NIR fluorescent rosol dyes were also prepared according to our newly-established synthetic strategy as shown in Scheme 1A. Compounds 1 were acylated under Friedel Crafts conditions, which ultimately provided compounds 2 in high yield by way of additionally demethylating their acylated methoxy-intermediates (byproducts not shown) for the purpose of preserving the initial starting materials. Intermolecular condensation of compounds 2 with resorcinol under acidic conditions and heat gave Me-Rosol, Et-Rosol, Pip-Rosol, and Jul-Rosol ranging from moderate to low yields. Presumably, low-volume solution (1 mL) stirring difficulties and progressive efforts in isolating each non-NIR rosol dye upon work-up and purification account for the varied reaction yields.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of Non-NIR Fluorescent Rosol Dyes and THQ-Rosol.a

aReagents and conditions: (a) 1, benzoyl chloride, AICI3, DCM, 0°C → RT; BBr3, DCM, 0°C → RT; Me-2 (89%), Et-2 (92%), Pip- 2 (94%), Jul-2 (27%); (b) 2, resorcinol, MeSO3H, 100°C, 3 hr, Me- Rosol (69%), Et-Rosol (8%), Pip-Rosol (25%), Jul-Rosol (4%); (c) 3, benzoyl chloride, AlCl3, DCM, 0°C → RT, 2 hr, N2, 85%; (d) 4, resorcinol, MeSO3H, 90°C, overnight, 49%.

Evaluated Spectroscopic, Photophysical, and Physical Properties.

The measured spectroscopic, photophysical, and experimentally-determined physical properties of the prepared non-NIR fluorescent rosol dyes were obtained using standard techniques/methods and are also provided in Table 1. The non- NIR fluorescent rosol dyes revealed general trends of increasing measured maximum absorption wavelength ranging from 520 nm to 540 nm alongside increasing measured maximum emission wavelength ranging from 557 nm to 574 nm for Me-Rosol, Et-Rosol, Pip-Rosol, and Jul-Rosol, respectively. As such, all of these non-NIR fluorescent rosol dyes displayed a small Stokes shift ranging from 34 nm to 38 nm, which are as small as those of fluorescein, MB, and ICG. Despite the non-NIR fluorescent rosol dyes revealing a general trend of decreasing molar absorptivity values for Me-Rosol, Et-Rosol, Pip-Rosol, and Jul-Rosol ranging from 46,136 M−1cm-1 to 30,420 M−1cm−1, respectively, all of these non-NIR fluorescent rosol dyes provided excellent photostability by essentially maintaining their initial fluorescence emission intensity when under continuous photoirradiation. Although Me-Rosol, Et-Rosol, and Pip-Rosol revealed a weak general trend of both decreasing fluorescence quantum yield and brightness values ranging from 0.182 to 0.048 and 8.4 M−1cm−1 to 2.0 M−1cm−1, respectively, Jul-Rosol displayed superior fluorescence quantum yield and brightness value of 0.414 and 13 M−1cm−1, respectively, due to the reduced nonradiative decay afforded by its annulated torsionally restrictive alkyl substituents appended to the exocyclic N-heteroatom of its underlying xanthene core-based scaffold. The non-NIR fluorescent rosol dyes revealed a general trend of increasing experimentally-determined pKa values ranging from 4.84 to 5.76 for Me-Rosol, Et-Rosol, Pip-Rosol, and Jul-Rosol, respectively, due to the progressive decrease in their N-C3’ torsion angle that results from the steric hindrance their increasingly torsionally-restrictive alkyl substituents afford them.

Linear Regression Analyses.

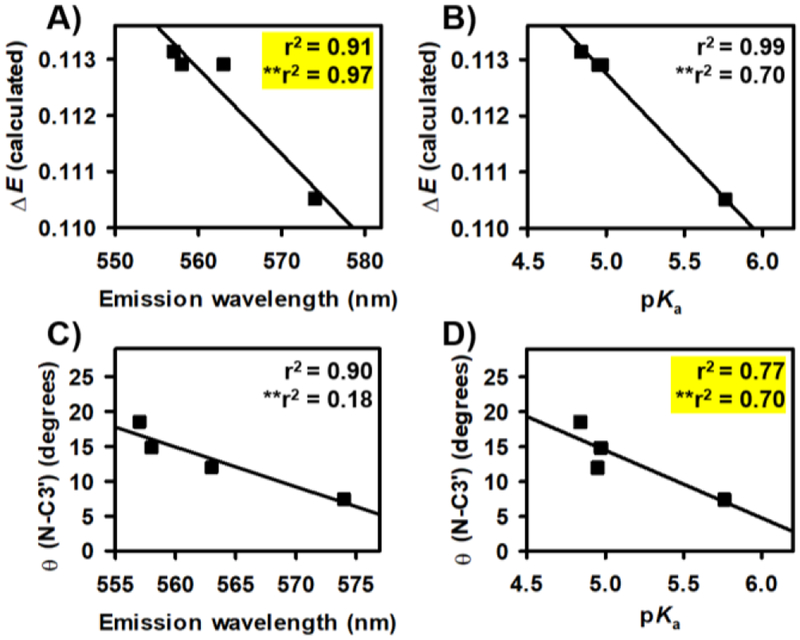

The calculated energetics and the modeled N-C3’ torsion angle of each non-NIR fluorescent rosol dye were separately plotted against their evaluated photo- physical and physical properties, which allowed for statistical measure of a coefficient of determination (r2) from each correlation plot (Figures 4A–D). We discerned high correlations (r2 ≥ 0.64) amongst both their calculated molecular orbital energy gap values and modeled N-C3’ torsion angles when each was interrelated to their measured maximum emission wavelengths and their respective experimentally-determined pKa values, wherein we obtained an r2 value of 0.91, 0.99, 0.90, and 0.77 from their linear regression analyses, respectively. As such, the calculated molecular orbital energy gap value and modeled N- C3’ torsion angle provided a quantitative means for designing THQ-Rosol.

Figure 4.

Linear regression analyses and statistical measure between select set of parameters of the non-NIR fluorescent rosol dyes without and with inclusion of relevant values of THQ-Rosol. Correlation plots interrelating the calculated molecular orbital energy gap (ΔE) value to the A) maximum fluorescence emission wavelength (λem) and B) pKa value of the evaluated fluorescent rosol dyes. Correlation plots interrelating the modeled N-C3’ torsion angle to the C) maximum fluorescence emission wavelength (λem) and D) pKa value of the evaluated fluorescent rosol dyes. The r2 value is the accompanying coefficient of determination of the aforementioned analyzed set of parameters of the evaluated non- NIR fluorescent rosol dyes without and with (**) THQ-Rosol. Yellow highlights that the correlation was maintained between the set of parameters upon inclusion of the relevant values of THQ-Rosol.

THQ-Rosol.

We leveraged the strong relationships that we derived from the correlation plots of the non-NIR fluorescent rosol dyes to rationally design THQ-Rosol, wherein we extrapolated from them that achieving an appropriately small molecular orbital energy gap value and modeled torsion angle could potentially impart a finely-tuned NIR fluorescence emission wavelength and an aptly-elevated pKa value to the rosol molecular platform such that it fittingly situates its off-on fluorescence intensity-pH profile to be optimal for deep-tissue fluorescence imaging of tumor-draining lymphatics. The 2’,3’-diamino-substituted xanthene core-based scaffold in conjunction with ethyl substituents appended to its annulated and adjacently-situated exocyclic N-heteroatoms concurrently afforded its rosol-based molecular platform the optimal combination of i) an appropriate molecular orbital gap value of 0.10389 hartrees via a concomitant increased EHOMO value (−0.17245 har-trees) and a decreased E LUMO value (−0.06856 hartrees) and ii) the smallest modeled N-C2’ and N-C3’ torsion angles (12.21° and 10.34°, respectively) amongst additionally-explored N-substituted THQ-Rosol analogues having appended alkyl substituents with either less or more steric bulk (Table 1 and Figure S1). As DFT calculations inspired an innovative approach of designing a rosol molecular platform with a 2’,3’-diamino-substituted xanthene-based scaffold alongside appending appropriate torsionally-restrictive substituents to its adjacently-situated exocyclic N-heteroatoms, further development of THQ-Rosol required we establish a new synthetic strategy that could allow for its direct preparation because current efforts leading to molecular platforms that have a 3’-amino-6’-hydroxyxanthene-based scaffold either 1) afford a rhodol molecular platform or 2) can- not afford a rosol molecular platform having a 2’,3’-diamino- substituted xanthene-core based scaffold (Figure 3A). As such, we established a synthetic strategy that would allow for directly preparing a NIR fluorescent rosol dye that has a 2’,3’-diamino- substituted xanthene core-based scaffold (Figure 3B). THQ- Rosol was prepared in two steps from known starting materials according to Scheme 1B.30–32 Compound 3 was concurrently acylated and demethylated under Friedel Crafts conditions to give compound 4 in high yield with marginal formation of its acylated methoxy-intermediate (byproduct not shown). Intermolecular condensation of intermediate 4 with resorcinol under acidic conditions provided THQ-Rosol in moderate yield.

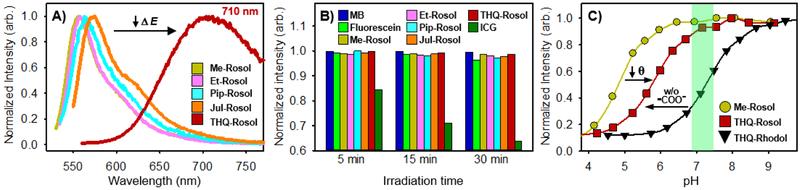

The measured spectroscopic, photophysical, and experimentally-determined physical properties of THQ-Rosol were similarly obtained using traditional techniques/methods and are provided in Table 1. THQ-Rosol maintained the general trend we observed for the non-NIR fluorescent rosol dyes by revealing a maximum absorption wavelength of 550 nm and a noteworthy measured maximum emission wavelength of 710 nm, which is a difference of ≥ 136 nm in the measured maximum emission wavelength when compared to the prepared non-NIR fluorescent rosol dyes Me-Rosol, Et-Rosol, Pip-Rosol, and Jul-Rosol, which can be attributed to its lower molecular orbital energy gap value (Figure 5A). As such, THQ-Rosol represents the first uncharged xanthene core-based scaffold/molecular platform that provides NIR fluorescence emission beyond 700 nm under aqueous conditions (i.e., without any appreciable organic co-solvent also in the media). Accordingly, THQ-Rosol displayed a remarkable Stokes shift of 160 nm, and thereby would better accommodate high detection sensitivity by promoting minimal instrumentation source background upon use when compared to those of fluorescein, MB, and ICG. Moreover, THQ-Rosol also displayed robust photostability via maintaining over 99% of its original fluorescence emission intensity when under continuous photoirradiation and is superior to that of the only generic molecular fluorescent dye commonly used towards lymphatic fluorescence imaging applications having NIR fluorescence emission (i.e., ICG) (Figure 5B). Notably, ICG demonstrated rapid and significant photobleaching by maintaining less than 64% of its original fluorescence emission intensity under identical conditions. In addition, we found that its aptly-elevated pKa value of 5.85 fittingly situates its off-on fluorescence intensity-pH profile such that it could afford minimal overlapping background fluorescence response between if it demonstrated appreciable residual retention within tumor tissue after being administered and having drained into the lymphatics, whereupon THQ-Rosol would then afford a pH-insensitive maximal fluorescence response (Figure 5C). As shown from the comparable r2 values of 0.97 and 0.70, its molecular orbital energy gap value and small N-C3’ torsion angle of THQ-Rosol primarily accounted for its pronounced fluorescence emission of 710 nm and its experimentally-determined pKa value of 5.85, respectively (Figures 4A and 4D). THQ-Rosol also demonstrated excellent stability to standard bioanalytes under their normal biological and elevated concentrations by maintaining its initial NIR fluorescence response (Figure S10). Lastly, based on its absorption-based linearity profile, we determined that THQ-Rosol maintains an apparent solubility of ~15 mg/L (40 μM), which could prove to be effective for clinical applications contingent on the outcomes of additional studies capable of determining its pharmacokinetic, pharmacodynamic, and dose-escalation profile (Figure S11). Given all of its favorable properties, we next assessed its efficacy to afford the real-time visualization of tumor-draining lymphatics by evaluating THQ-Rosol in vitro and in vivo.

Figure 5.

Measured photophysical and experimentally-determined physical properties of the non-NIR fluorescent rosol dyes and THQ- Rosol. A) Fluorescence emission profile of THQ-Rosol accentuating i) the effect of its lower calculated molecular orbital energy gap value and ii) the difference in its maximum fluorescence emission wavelength when compared to those of the non-NIR fluorescent rosol dyes. B) Photostability of the generic molecular fluorescent dyes commonly used for lymphatic mapping applications, non-NIR fluorescent rosol dyes, and THQ-Rosol. C) Experimentally-determined off-on fluorescence intensity pH-profile of a non-NIR fluorescent rosol dye, THQ- Rosol, and its proposed analogue having a pendant benzene moiety with a charged 2-carboxylate group (-COO-), all of which accentuate that by minimizing the N-C3’ torsion angle of a 3’-amino-6’-hydroxyxanthene-based scaffold as an integrated component of a molecular platform having a pendant benzene moiety without a charged 2-carboxylate group a pKa value can be modulated such that it could afford a pH- insensitive and maximal fluorescence response. The green-shaded region identifies tumor-draining lymphatics pH levels (pH 6.8–7.4).

Cellular Analyses.

We evaluated THQ-Rosol for maintaining cellular viability using Calcein-AM as a live-cell stain, wherein the cells maintained their viability across a range of applicable concentrations up to 25 μM (Figure S12). We adopted an appropriate protocol upon applying THQ-Rosol to a cancer cell line and used confocal fluorescence microscopy to assess its ability to i) translocate across the cell membrane, ii) not demonstrate permanent intracellular retention, and iii) afford only a minimal fluorescence response if so. As such, we gleaned from performing subsequent washing steps, the need for an elevated PMT detector gain level, and its punctate staining pattern we observed, that its comparable pKa value allowed THQ-Rosol to i) demonstrate transient intracellular retention in acidic subcellular compartments, and ii) display a minimal fluorescence response when within them (Figure S13). We validated its transient equilibrium-driven lysosomal localization by performing colocalization studies using a standard lysosomal labeling dye alongside THQ-Rosol, wherein we used two different pairs of appropriate excitation and emission channels with different PMT detector gain levels to visualize their fluorescence responses (Figures S13A and S13B). Analysis of the puncta from the images of each respective dye when overlaid provided a Pearson coefficient (r) of 0.70, which strongly supports that THQ-Rosol localizes to lysosomes (Figure S13C).

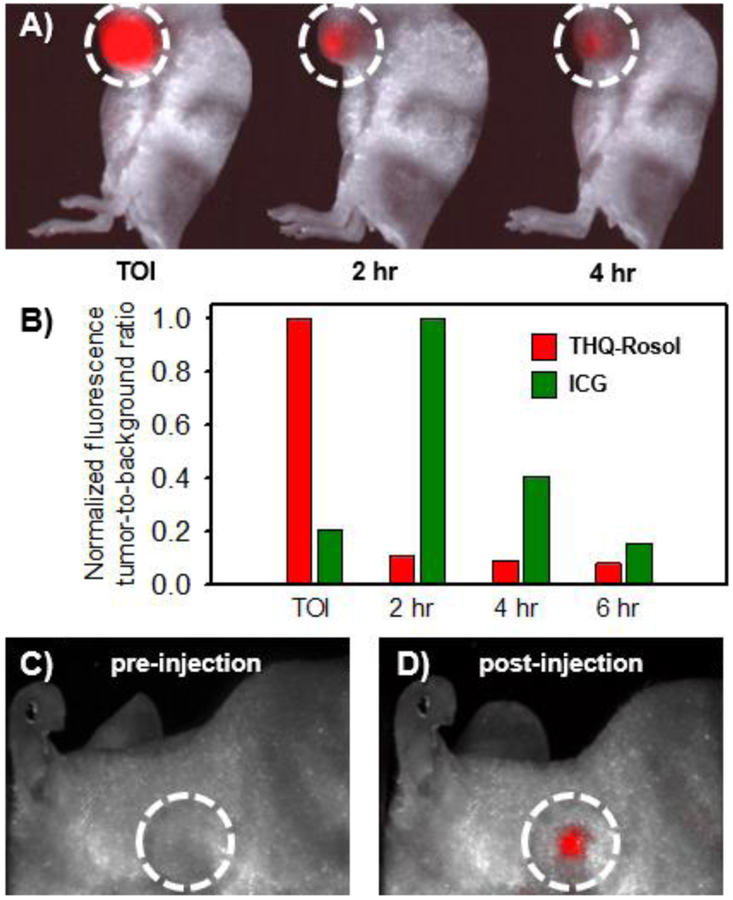

In Vivo Imaging.

We mimicked the standard use of a generic molecular fluorescent dye toward lymphatic mapping applications by administering THQ-Rosol to a xenograft tumor model, wherein we assessed its efficacy to afford prompt diffusion and timely drainage from within a tumor following its administration (Figure 6A). In evaluating its fluorescence tumor-to-background ratio at select time points, we determined that THQ-Rosol outperforms ICG under identical conditions (Figure 6B). Accordingly, we observed that ~90% of THQ-Rosol drained from the tumor in 2 hours post-administration following its prompt diffusion throughout the tumor upon its administration, whereas we observed a 5-fold increase in the fluorescence tumor-to-background ratio of ICG over the first 2 hours post-administration due to its delayed diffusion and only ~60% of ICG drained from the tumor within the subsequent 2 hours. We also observed that only ~5% of THQ-Rosol remained in the tumor tissue throughout the course of 6 hours, whereas over ~40% and ~10% of ICG remained in the tumor tissue throughout the course of 4 hours and 6 hours, respectively. Presumably, the significant difference in the post-administration diffusion and drainage profiles between THQ-Rosol and ICG can be attributed to their uncharged and charged physical properties, respectively, as well as its well-situated pKa value that fosters its transient intracellular retention. As such, these properties could further aid in the visualization of the lymphatics by also affording a minimal overlapping background fluorescence response. Accordingly, we assessed its ability to accumulate within an axillary lymph node, wherein it demonstrated a strong fluorescence response within the axillary lymph node with excellent contrast upon doing so (Figures 6C and 6D).

Figure 6.

In vivo efficacy of THQ-Rosol toward lymphatic mapping applications. A) Representative images of THQ-Rosol following its administration to a GBM39 xenograft mouse model at select time points. B) The accompanying normalized fluorescence tumor-to-background ratio of THQ-Rosol (λem2 = 710 nm) compared to ICG (λem1 = 800–900 nm) at select time points (each 50 μL, 25 μM). Accumulation of THQ-Rosol in the axillary lymph node C) pre and D) post administration. TOI = time of injection. Dashed white circle circumscribes the axillary lymph node region.

Conclusion

We described the development of the first NIR fluorescent rosol dye (THQ-Rosol) tailored with optimal properties for overcoming the limitations arising from those of the generic molecular fluorescent dyes commonly-used for lymphatic mapping applications. We utilized efficient DFT calculations to facilitate the design of both non-NIR and NIR fluorescent rosol dyes, wherein we leveraged the strong relationships that we discerned between select calculated, modeled, and evaluated properties of the former dyes to rationally design an uncharged xanthene core-based scaffold as an integrated component of a rosol molecular platform such that it would have a finely-tuned NIR fluorescence emission wavelength (710 nm) and a pKa value (5.85) that fittingly situates its off-on fluorescence intensity-pH profile to provide optimal contrast for the deep-tissue fluorescence imaging of tumor-draining lymphatics. In doing so, we established a simple model to fashion a priori non-NIR and NIR fluorescent rosol dyes with specific properties. We demonstrated that THQ-Rosol outperforms ICG by affording timely tumor drainage and definitive lymph node visualization with excellent contrast due to its design. As such, THQ-Rosol could significantly aid in the visualization of the potential metastatic tumor-draining lymph node(s) for their pre- and intraoperative treatment.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Tim Doyle (Stanford Small Animal Imaging Facility) and Kitty Lee (Stanford Cell Science Imaging Facility) for technical assistance. The project was supported, in part, by the National Center for Research Resources: S10 0D010580; the National Science Foundation: CHE-1112194 (TEG); the Department of Energy: DE-SC0008397 (FTC); The Ben and Catherine Ivy Foundation (FTC); and the National Cancer Institute: R21 CA205564 (FTC), F32 CA213620 (KSH), and T32 CA118681 (JLK).

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Molecular modeling and calculations, 1H and 13C NMR spectra, UV/vis and fluorescence spectra, pH titrations, cell assays, and animal study protocols. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES

- (1).Xia L; Fang C; Chen G; Sun C Relationship between the Extent of Resection and the Survival of Patients with Low-Grade Gliomas: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Cancer 2018, 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Sun MZ; Ivan ME; Clark AJ; Oh MC; Delance AR; Oh T; Safaee M; Kaur G; Bloch O; Molinaro A; et al. Gross Total Resection Improves Overall Survival in Children with Choroid Plexus Carcinoma. J. Neurooncol 2014, 116 (1), 179–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Wyld L; Audisio RA; Poston GJ The Evolution of Cancer Surgery and Future Perspectives. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol 2015, 12 (2), 115–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Vahrmeijer AL; Hutteman M; van der Vorst JR; van de Velde CJH; Frangioni JV Image-Guided Cancer Surgery Using near-Infrared Fluorescence. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol 2013, 10 (9), 507–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Chi C; Du Y; Ye J; Kou D; Qiu J; Wang J; Tian J; Chen X Intraoperative Imaging-Guided Cancer Surgery: From Current Fluorescence Molecular Imaging Methods to Future Multi-Modality Imaging Technology. Theranostics 2014, 4 (11), 1072–1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Ayestaray B; Bekara F Fluorescein Sodium Fluorescence Microscope-Integrated Lymphangiography for Lymphatic Supermicrosurgery. Microsurgery 2015, 35 (5), 407–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Currie AC; Brigic A; Thomas-Gibson S; Suzuki N; Moorghen M; Jenkins JT; Faiz OD; Kennedy RH A Pilot Study to Assess near Infrared Laparoscopy with Indocyanine Green (ICG) for Intraoperative Sentinel Lymph Node Mapping in Early Colon Cancer. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol 2017, 43 (11), 2044–2051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).He J; Yang L; Yi W; Fan W; Wen Y; Miao X; Xiong L Combination of Fluorescence-Guided Surgery with Photodynamic Therapy for the Treatment of Cancer. Mol. Imaging 2017, 16, 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Nagaya T; Nakamura YA; Choyke PL; Kobayashi H Fluorescence-Guided Surgery. Front. Oncol 2017, 7, 1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).DSouza AV; Lin H; Henderson ER; Samkoe KS; Pogue BW Review of Fluorescence Guided Surgery Systems: Identification of Key Performance Capabilities beyond Indocyanine Green Imaging. J. Biomed. Opt 2016, 21 (8), 80901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Lavis LD Teaching Old Dyes New Tricks: Biological Probes Built from Fluoresceins and Rhodamines. Annu. Rev. Biochem 2017, 86, 825–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Howland RH Methylene Blue: The Long and Winding Road from Stain to Brain: Part 1. J. Psychosoc. Nurs. Ment. Health Serv. 2016, 54 (9), 21–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Schirmer RH; Adler H; Pickhardt M; Mandelkow E Lest We Forget You--Methylene Blue… Neurobiol. Aging 2011, 32(12), 2325.e7–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Mindt S; Karampinis I; John M; Neumaier M; Nowak K Stability and Degradation of Indocyanine Green in Plasma, Aqueous Solution and Whole Blood. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci 2018, 17 (9), 1189–1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Song L; Hennink EJ; Young IT; Tanke HJ Photo- bleaching Kinetics of Fluorescein in Quantitative Fluorescence Micros- copy. Biophys. J 1995, 68 (6), 2588–2600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Choi HS; Nasr K; Alyabyev S; Feith D; Lee JH; Kim SH; Ashitate Y; Hyun H; Patonay G; Strekowski L; et al. Synthesis and In Vivo Fate of Zwitterionic NearInfrared Fluorophores. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2011, 50 (28), 6258–6263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Frangioni JV In Vivo Near-Infrared Fluorescence Imaging. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 2003, 7 (5), 626–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Wen H; Huang Q; Yang X-F; Li H Spirolactamized Benzothiazole-Substituted N,N Diethylrhodol: A New Platform to Construct Ratiometric Fluorescent Probes. Chem. Commun 2013, 49 (43), 4956–4958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Kim HN; Swamy KMK; Yoon J Study on Various Fluorescein Derivatives as PH Sensors. Tetrahedron Lett. 2011, 52 (18), 2340–2343. [Google Scholar]

- (20).Kamiya M; Asanuma D; Kuranaga E; Takeishi A; Sakabe M; Miura M; Nagano T; Urano Y β-Galactosidase Fluorescence Probe with Improved Cellular Accumulation Based on a Spirocyclized Rhodol Scaffold. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2011, 133 (33), 12960–12963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Peng T; Yang D Construction of a Library of Rhodol Fluorophores for Developing New Fluorescent Probes. Org. Lett 2010, 12 (3), 496–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Davis S; Weiss MJ; Wong JR; Lampidis TJ; Chen LB Mitochondrial and Plasma Membrane Potentials Cause Unusual Accumulation and Retention of Rhodamine 123 by Human Breast Adenocarcinoma-Derived MCF-7 Cells. J. Biol. Chem 1985, 260 (25), 13844–13850. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Grimes PA; Stone RA; Laties AM; Li W Carboxyfluorescein: A Probe of the Blood-Ocular Barriers With Lower Membrane Permeability Than Fluorescein. Arch. Ophthalmol 1982, 100 (4), 635–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Saylor JR Photobleaching of Disodium Fluorescein in Water. Experiments in Fluids 1995, 18 (6), 445–447. [Google Scholar]

- (25).Dodani SC; Firl A; Chan J; Nam CI; Aron AT; Onak CS; Ramos-Torres KM; Paek J; Webster CM; Feller MB; et al. Copper Is an Endogenous Modulator of Neural Circuit Spontaneous Activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2014, 111 (46), 16280–16285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Castro JC Rosamine and Fluorescein Derivatives as Donors/Acceptors for “Through-Bond” Energy Transfer Cassettes Dissertation, Texas A&M University: College Station, TX, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- (27).Whitaker JE; Haugland RP; Ryan D; Hewitt PC; Haugland RP; Prendergast FG Fluorescent Rhodol Derivatives: Versatile, Photostable Labels and Tracers. Anal. Biochem 1992, 207(2), 267–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Chang CJ; Nolan EM; Jaworski J; Okamoto K; Hayashi Y; Sheng M; Lippard SJ ZP8, a Neuronal Zinc Sensor with Improved Dynamic Range; Imaging Zinc in Hippocampal Slices with Two-Photon Microscopy. Inorg. Chem 2004, 43 (21), 6774–6779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Ash C; Dubec M; Donne K; Bashford T Effect of Wavelength and Beam Width on Penetration in Light-Tissue Interaction Using Computational Methods. Lasers Med. Sci 2017, 32 (8), 1909–1918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Hettie KS; Glass TE Turn-On Near-Infrared Fluorescent Sensor for Selectively Imaging Serotonin. ACS Chem. Neurosci 2016, 7 (1), 21–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Tian Z; Tian B; Zhang J Synthesis and Characterization of New Rhodamine Dyes with Large Stokes Shift. Dyes Pigm. 2013, 99 (3), 1132–1136. [Google Scholar]

- (32).Jagtap AR; Satam VS; Rajule RN; Kanetkar VR The Synthesis and Characterization of Novel Coumarin Dyes Derived from 1,4-Diethyl-1,2,3,4-Tetrahydro-7-Hydroxyquinoxalin-6-Carboxaldehyde. DyesPigm. 2009, 1 (82), 84–89. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.