Exploring the feasibility of primary care physicians providing follow‐up care for childhood cancer survivors, this two‐stage study focused on the perspectives of survivors and their parents and the perspectives of their primary care physicians, aiming to develop a new model of long‐term shared follow‐up care for childhood cancer survivors.

Keywords: Primary care, Childhood cancer, Follow‐up care, Confidence, Barriers, Transition

Abstract

Background.

Primary care physicians (PCPs) are well placed to provide holistic care to survivors of childhood cancer and may relieve growing pressures on specialist‐led follow‐up. We evaluated PCPs' role and confidence in providing follow‐up care to survivors of childhood cancer.

Subjects, Materials, and Methods.

In Stage 1, survivors and parents (of young survivors) from 11 Australian and New Zealand hospitals completed interviews about their PCPs' role in their follow‐up. Participants nominated their PCP for an interview for Stage 2. In Stage 2, PCPs completed interviews about their confidence and preparedness in delivering childhood cancer survivorship care.

Results.

Stage 1: One hundred twenty survivors (36% male, mean age: 25.6 years) and parents of young survivors (58% male survivors, survivors' mean age: 12.7 years) completed interviews. Few survivors (23%) and parents (10%) visited their PCP for cancer‐related care and reported similar reasons for not seeking PCP‐led follow‐up including low confidence in PCPs (48%), low perceived PCP cancer knowledge (38%), and difficulty finding good/regular PCPs (31%). Participants indicated feeling "disconnected" from their PCP during their cancer treatment phase. Stage 2: Fifty‐one PCPs (57% male, mean years practicing: 28.3) completed interviews. Fifty percent of PCPs reported feeling confident providing care to childhood cancer survivors. PCPs had high unmet information needs relating to survivors' late effects risks (94%) and preferred a highly prescriptive approach to improve their confidence delivering survivorship care.

Conclusion.

Improved communication and greater PCP involvement during treatment/early survivorship may help overcome survivors' and parents' low confidence in PCPs. PCPs are willing but require clear guidance from tertiary providers.

Implications for Practice.

Childhood cancer survivors and their parents have low confidence in primary care physicians' ability to manage their survivorship care. Encouraging engagement in primary care is important to promote holistic follow‐up care, continuity of care, and long‐term surveillance. Survivors'/parents' confidence in physicians may be improved by better involving primary care physicians throughout treatment and early survivorship, and by introducing the concept of eventual transition to adult and primary services. Although physicians are willing to deliver childhood cancer survivorship care, their confidence in doing so may be improved through better communication with tertiary services and more appropriate training.

Introduction

Cancer survivors have complex and ongoing follow‐up care needs [1]. Childhood cancer survivors (CCS) are at risk of treatment‐related health complications affecting their physical and psychological functioning [2], [3], [4]. Survivors' risks of developing morbidities continue to rise as they age [5]. Long‐term follow‐up care is recommended for the surveillance and management of potential lifelong, cancer‐related health conditions [6], [7], [8]. Although hospital‐based, oncologist‐led models of care are generally preferred by survivors and health professionals [9], [10], [11], they are often resource‐intensive and can have insufficient staffing and funding [12], [13]. Survivors report significant barriers to accessing follow‐up, including logistical factors (e.g., costs, distance) and low motivation (e.g., low perceived late effects risk) [14]. As few as 25% of CCS are engaged in specialized cancer survivorship care [15], [16]. Disengagement from follow‐up may be due to a reluctance to transition from pediatric care [17], or low perceived pediatric survivorship experience/knowledge among primary care physicians (PCPs) [18], [19]. Many survivors are therefore lost to follow‐up upon transitioning from family‐focused pediatric to patient‐centered, often PCP‐led adult care, resulting in many survivors with poor knowledge and skills to advocate for their care in the adult system [20].

A reliance on hospital‐based, specialist‐led follow‐up is not ideal, with a lack of resources prompting transition of lower‐risk survivors to follow‐up in primary care [12], [21]. For many survivors, there are advantages to being transitioned to primary care. PCPs are well placed to provide holistic care and appear willing to deliver survivorship care to CCS [22]. Survivors engaged in PCP‐led care compared with oncologist‐led care demonstrate similar physical and emotional outcomes, despite receiving less survivorship‐focused follow‐up [23], [24]. However, PCPs report difficulty caring for CCS, complicated by their rarity in any one PCP practice [22]. There is little literature on survivor‐reported barriers to, and optimal delivery of, PCP‐led childhood cancer survivorship care. Furthermore, it is unclear whether these barriers may affect PCPs' confidence in providing care to this population.

We aimed to explore the feasibility of PCP‐led survivorship care from survivors'/parents' and their PCPs' perspectives through a two‐stage study: Stage one describes survivors' and parents' reported reasons for (not) accessing PCP‐led survivorship care, and Stage two evaluates PCPs' reported needs (e.g., communication, support, and information) for delivering survivorship care and their perceived confidence in delivering care to CCS. The study outcomes, which take into account survivors' and PCPs' preferences and needs, will inform the development of a new, potentially more feasible and sustainable model of long‐term shared follow‐up care for CCS.

Subjects, Materials, and Methods

Design

This cross‐sectional study had two stages and was approved by ethics at each participating hospital. Stage 1 participants from a larger study, the ANZCHOG Survivorship Study, agreed to complete an optional in‐depth interview after completing surveys [25], and nominated their PCP to be interviewed, which formed Stage 2. This study adheres to the COREQ guidelines for qualitative research (supplemental online Fig. 1).

Participants

We identified eligible survivors from electronic hospital records who were diagnosed with cancer before 16 years of age and were treated at one of 11 participating Australian and New Zealand hospitals; were diagnosed at least 5 years prior; had completed active treatment; were English speaking; and were in remission. We invited parents of young survivors under the age of 16 to complete the interview on behalf of their child. We invited Australian PCPs, nominated by Stage 1 participants, by post. We obtained informed consent from all participants.

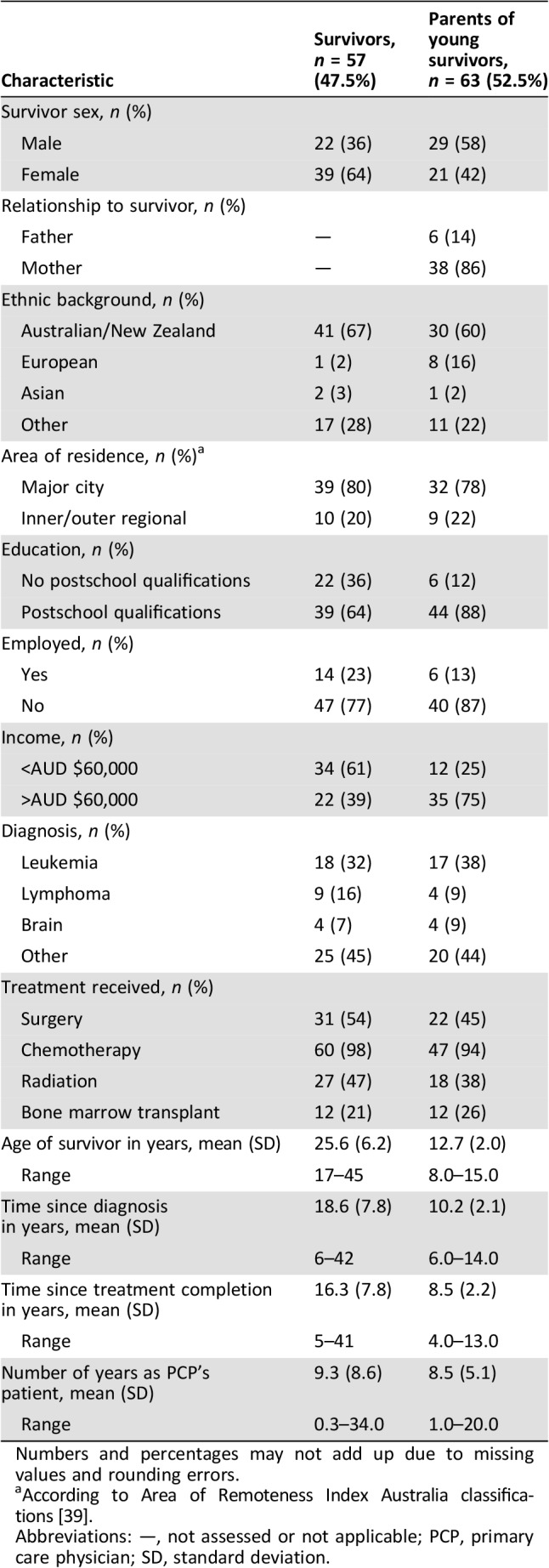

Data Collection

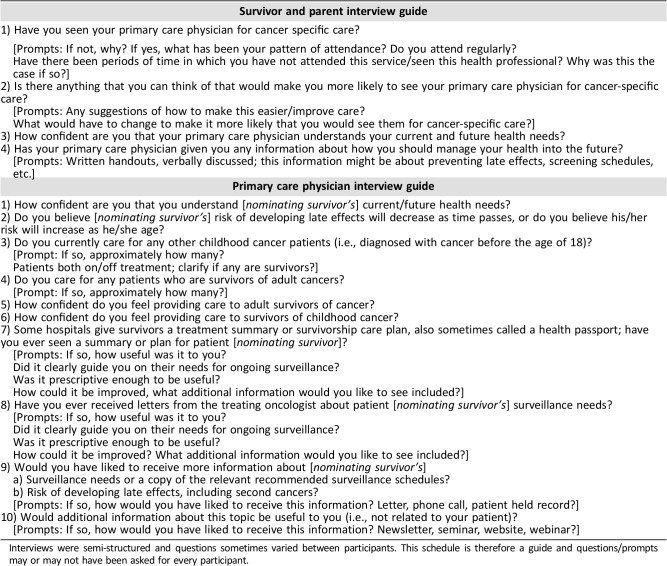

A multidisciplinary team developed the interview guides (Table 1). Clinical psychologists and trained researchers piloted and conducted the semi‐structured telephone interviews. We collected survivors' clinical/demographic data in the survey (Table 2). Survivor/parent interviews included questions on participants’ follow‐up engagement and reasons for accessing/not accessing PCP‐led care. In PCP interviews, we collected PCPs’ demographic and practice‐related data, and asked about PCP receipt and use of survivorship care plans (SCPs) and oncologist letters, information, support and communication needs, and confidence understanding survivors’ current and future follow‐up needs and delivering survivorship care to CCS compared with adult cancer survivors. We audio‐recorded and transcribed all interviews verbatim.

Table 1. Interview schedule for Stage 1 (survivors and parents) and 2 (primary care physicians).

Interviews were semi‐structured and questions sometimes varied between participants. This schedule is therefore a guide and questions/prompts may or may not have been asked for every participant.

Table 2. Clinical and demographic characteristics of adult and young survivor interviewees.

Numbers and percentages may not add up due to missing values and rounding errors.

According to Area of Remoteness Index Australia classifications [39].

Abbreviations: —, not assessed or not applicable; PCP, primary care physician; SD, standard deviation.

Statistical Analysis

We used SPSS 24.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY) to conduct descriptive analysis and chi‐square tests and t test analyses for respondent/nonrespondent and group comparisons. We used NVivo11 (QSR International Pty Ltd) to guide qualitative analysis. We categorized the qualitative data according to predetermined themes guided by our research questions for each Stage. We conducted thematic content analysis, informed by the Miles and Huberman methodology [26], which allowed the thematic organization of participant responses. We used matrix coding to explore themes across participant groups and characteristics (e.g., comparing survivor and parent data). Three researchers (C.S., J.F., A.T.) double coded 30% of interviews for consistency. Given the study size and high concordance (96.8%, k = 0.8), one author (C.S.) coded the remainder of interviews. We resolved disagreements through discussion until consensus was achieved.

Results

Stage 1: Survivor/Parent Perspectives

Sample Characteristics.

Of 612 ANZCHOG Survivorship Study respondents, 358 (58.5%) opted to be interviewed. We interviewed participants until we reached data saturation in each group at 57 adult CCS (48%; average age: 25.6 years, standard deviation [SD] = 6.2; average time since diagnosis: 18.6 years, SD = 7.8) and 63 parents of survivors under 16 years (53%; average child age: 12.7 years, SD = 2.0; average time since diagnosis: 10.2 years, SD = 2.1). Table 2 summarizes interviewees’ demographic/clinical characteristics. Interview respondents were significantly younger (mean age 25.6) than nonrespondents (28.4 years, t(212) = 2.233, p = .003). We observed no other significant differences between interview respondents and nonrespondents in sex, rurality, marital and employment status, education, cancer diagnosis, treatment, and time since diagnosis/treatment completion.

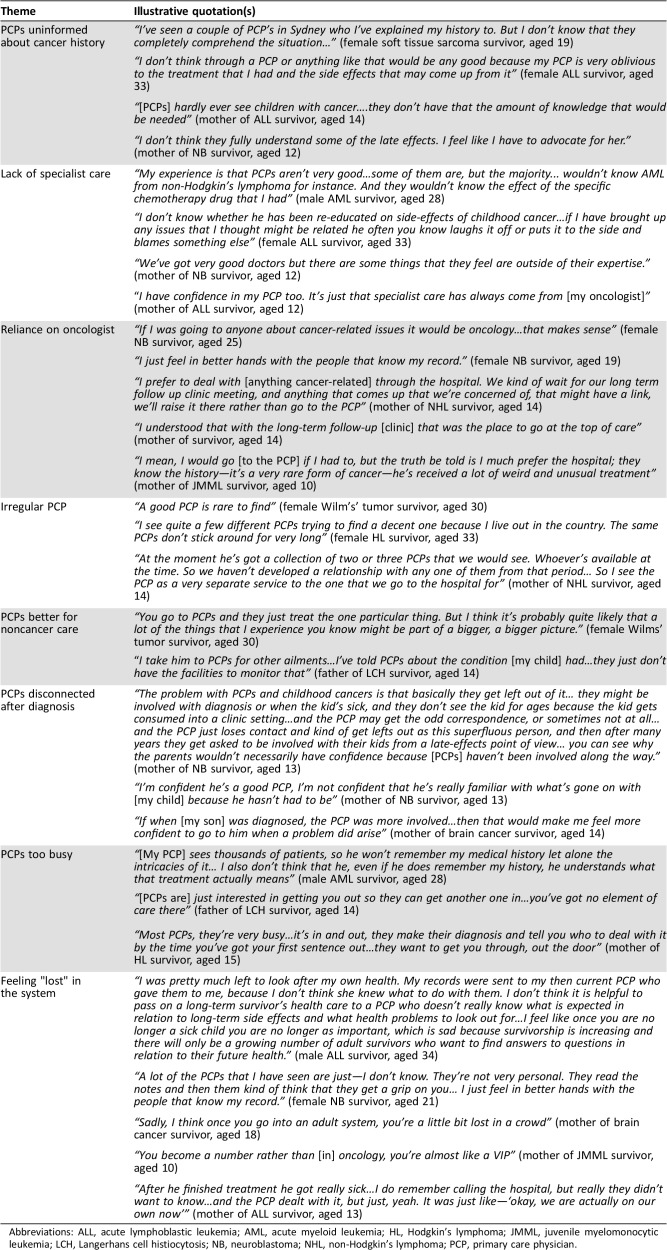

Thirty‐nine percent of older survivors (>16 years) and 81% of young survivors (<16 years) were engaged in oncologist‐led follow‐up, and few had visited their PCP for cancer‐related care since finishing cancer treatment (23% and 10%, respectively). Survivors and parents reported similar reasons for not accessing PCP‐led follow‐up including little perceived PCP cancer knowledge and low confidence in PCPs, associated with PCPs’ limited involvement during the treatment/early survivorship period. We therefore grouped responses for analysis. Table 3 provides illustrative quotations.

Table 3. Survivor and parent reasons for not accessing PCP‐led care and low confidence in PCPs.

Abbreviations: ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; HL, Hodgkin's lymphoma; JMML, juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia; LCH, Langerhans cell histiocytosis; NB, neuroblastoma; NHL, non‐Hodgkin's lymphoma; PCP, primary care physician.

Reasons for (Not) Accessing PCP‐Led Care.

Of the reasons raised by 61 participants for not visiting PCPs for survivorship care, participants most frequently mentioned low perceived PCP knowledge about their cancer history and long‐term survivorship needs (38%). Some perceived PCPs to lack specialist knowledge about cancer survivors (28%), making them less suitable for survivorship care compared with the oncology team who “know what to look for at specific times whereas the PCP doesn't know” (mother of acute lymphoblastic leukemia [ALL] survivor, aged 15). Participants deemed PCPs more suitable for general health care (13%). Participants also cited not visiting PCPs for follow‐up due to difficulty finding a good or regular PCP (31%) to build rapport with and who was familiar with their medical history. However, even some survivors with regular PCPs reported feeling detached (20%) from them following diagnosis: “The PCP that connected us to the hospital had nothing to do with us after that” (mother of ALL survivor, aged 15).

Another barrier was low confidence in PCPs’ ability to deliver survivorship care (48%). Participants’ confidence appeared related to good communication and relationships with the oncology team, and to the time they had known their PCP, as it increased familiarity with their cancer history. Participants who reported confidence in PCPs attributed it to a good rapport, often developed over a long time. Those who did have a good relationship with their PCP described feeling “really lucky” (mother of ALL survivor, aged 13), recognizing the importance and rarity of this relationship. Participants preferring oncologist‐led care (26%) occasionally even delayed seeking medical advice from a PCP (n = 4), instead "saving" it for their next clinic appointment. Participants reported negativity toward PCPs alongside feelings of separation and isolation from the oncology team, with fear of getting "lost" in the system, particularly following transition to adult care.

Other barriers to seeking PCP‐led follow‐up included having an aversion to doctors after treatment (n = 4), perceiving PCPs as too busy (n = 11) for their complex needs, or due to out‐of‐pocket expenses (n = 3). One recurring suggestion to alleviate barriers and low confidence in PCPs was earlier involvement of PCPs: “If when [my son] was diagnosed the PCP was more involved…that would make me feel more confident to go to him” (mother of brain tumor survivor, aged 14).

Stage 2: Physicians’ Perspectives

Sample Characteristics.

Of 160 eligible and contactable PCPs nominated by Stage 1 survivors/parents, 74 opted‐in for an interview (46%). We reached data saturation after interviews with 51 PCPs determined by two authors (C.S., J.F.) conducting analysis alongside data collection. Twenty‐nine (57%) PCPs were male, 33 (65%) worked in practices in major cities, and on average had 28.3 years’ experience (range = 8–60, SD = 11.7) at the time of study participation. On average, PCPs had cared for 2.3 CCS in their career (range = 1–11, SD = 2.1). Nonrespondents were more likely to be male. We observed no other differences between nonrespondents and respondents in PCP‐related factors (i.e., practice location) or survivor‐related factors (i.e., sex, age, diagnosis, years as PCPs’ patient, and years since primary diagnosis or treatment completion) [27].

Many (67%) recalled receiving letters from the survivor's treating oncologist about their cancer history and current medical needs. Few PCPs recalled receiving a treatment summary or SCP for their patients (12%). All PCPs felt confident providing care to adult cancer survivors, whereas only 54% of PCPs reported feeling confident providing care to CCS. Table 4 provides illustrative PCP quotes.

Table 4. PCPs’ perspectives of their role in childhood cancer survivorship care.

Abbreviation: PCP, primary care physician.

PCPs’ Communication/Information Needs.

Twenty PCPs had read/used their survivor's letters since receiving them from oncologists, and 75% found them useful. Letters facilitated communication between the PCP and tertiary treating team, making them “very useful…quite easy to communicate with his treating team and get advice” (male PCP, practicing 17 years). The letters facilitated communication both with the oncology team and with the patient. PCPs noted additional benefits of such letters, including patient education and personal reassurance about the patient's care plan. However, 25% of PCPs did not find oncologist letters useful, criticizing them for lacking information and instruction about the survivor's follow‐up and surveillance needs. Of the six PCPs who reported receiving a summary or care plan, all found them useful, describing them as a “roadmap” for delivering follow‐up care and “essential” (male PCP, practicing 29 years).

PCPs who had not received SCP or oncologist letters attributed nonreceipt to losing SCPs among other paperwork or to patients commonly changing PCPs and practices. For some, the interview was the first time PCPs had sighted the summary or care plan at all, despite it being on file. Many PCPs noted a breakdown in communication during their patient's treatment, as “The hospital tend[ed] to just take over from me, and we don't have much to do…with their treatments” (female PCP, practicing 19 years). Poor communication during the treatment period appeared to translate into a general lack of knowledge about survivors’ ongoing risks and, consequently, about survivors’ ongoing surveillance needs.

Most PCPs reported unmet information needs about their patients’ risk of developing late effects (94%) and recommended surveillance schedule (77%), and about general childhood cancer survivorship information (76%, i.e., not patient‐specific), emphasizing the importance of brevity. The remainder simply admitted “It's not high on my list” (male PCP, practicing 60 years) and noted the clinical utility of more general information undermined its importance, given the small patient load in their practices. PCPs overwhelmingly requested a prescriptive approach with clear directions for care from the treating oncologist, and distinct patient‐specific instructions “in black and white” (male PCP, practicing 43 years) reinforcing oncologist recommendations into a clear plan for care.

Confidence.

Despite all PCPs describing confidence providing follow‐up for adult cancer survivors, PCPs' confidence caring for CCS appeared less robust. Many (63.2%) PCPs reported feeling confident that they specifically understood survivors’ current and future health needs, generally portrayed as having a simple or “basic idea” (male PCP, practicing 57 years) of survivors’ needs. Most PCPs (79%) reported feeling comfortable assuming full responsibility for the follow‐up of CCS, if the survivor stopped attending survivorship clinics. Yet, PCPs’ confidence and willingness to assume full responsibility for CCS appeared to depend on various factors, including being part of a team or having clear direction from oncologists. PCPs’ confidence in survivors’ future health needs was also somewhat superficial, with one PCP commenting about their patient: “If he's not complaining of anything I'm confident that there's nothing wrong” (male PCP, practicing 27 years). Low confidence appeared to be related to poor knowledge about the specific protocols recommended for each survivor, particularly “the kind of routine follow‐up I should do or what sort of anticipatory care [is needed]” (male PCP, practicing 25 years). When asked if they believed survivors’ risk of developing late effects increases or decreases as they age, 14% of PCPs believed it decreased with time. Thirty percent "did not know" and reported “It's never clicked for me that childhood cancer was a high‐risk thing” (male PCP, practicing 43 years).

Qualitatively, PCPs attributed their lack of specific knowledge, and therefore confidence, to their inexperience and the few CCS they had seen in their career compared with adult cancer survivors. PCPs’ confidence was not associated with PCPs’ years of experience practicing (t(46) = −0.808, p = .808) and the number of CCS they had cared for in their career (t(44) = −0.699, p = .488).

Discussion

Although PCPs are best placed to provide holistic care, survivors and parents lack confidence in PCPs and reported many barriers to accessing PCP‐led follow‐up, including lack of involvement from their PCP during treatment and early survivorship. Many PCPs received oncologist letters, but few reported receiving SCPs. Most had unmet information needs regarding survivors’ current/future survivorship needs. PCPs reported lacking confidence in delivering cancer‐related care to CCS, and confidence appeared to depend on receiving very clear instructions for each patient regarding their specific ongoing surveillance needs and late effects risk.

Survivors’/Parents’ Perspective

Fewer survivors in our study engaged with PCPs than those in other studies [24]. Australia's dispersed nature and distance to survivorship clinics further highlights the need to encourage having regular PCPs among this high‐needs population [28]. Consistent with existing literature, survivors reported reluctance in visiting PCPs for cancer‐related care due to low perceived experience and pediatric survivorship knowledge [29], [30], as well as to strong feelings of detachment from PCPs after diagnosis. Strong PCP relationships in adult cancer patients are built on trust and rapport, most notably developing over time [31]. Such relationships may be less common in CCS who develop strong relationships with their oncologist and may prefer never to transition to adult care [12], [17]. Encouraging early involvement of PCPs and better communication with PCPs throughout the treatment and early survivorship phases may facilitate rapport building with the PCP. Increased PCP involvement may also reduce delayed visits among survivors "saving" health concerns for their annual or sometimes bi‐annual clinic visit at the hospital, which can lead to poorer prognoses for otherwise preventable or easily treatable conditions. Encouraging PCP involvement by the oncologist or tertiary hospital multidisciplinary team may improve survivors’ confidence and reduce potential anxiety induced by transition to adult (often primary) care, when many survivors become disengaged from any follow‐up [20], [32]. Disengagement results in missed opportunities to monitor for, and possibly prevent, treatment‐related complications. Feelings of isolation/separation from their oncology team following transition may be negatively projected onto PCPs, which might be alleviated by introducing the concept of transition earlier to families to potentially lessen their reluctance and increase their long‐term engagement and satisfaction with PCP‐led care [19].

PCPs’ Perspective.

PCPs’ small CCS load and the time‐poor nature of PCPs in our sample may explain PCPs’ preference for patient‐specific and prescriptive information, compared with general childhood cancer survivorship information. PCPs in our sample who had previously received SCPs and oncologist letters highly valued their instruction to guide their patient's follow‐up. Improved SCPs and letters directed to PCPs with clear follow‐up plans may assist them in delivering higher‐quality risk‐based care, including referral to specialists where needed and the coordination of survivors’ potentially complex ongoing care [29]. This could be facilitated through the standardization of SCPs, which currently differ nationally and internationally [12]. The crucial nature of good communication for the effective delivery of evidence‐based care has also been emphasized in recent literature [33].

Over half of the PCPs in our study reported feeling confident delivering survivorship care and understanding survivors' health care needs. However many indicated a lack of true understanding of the risks/needs unique to CCS, possibly a consequence of poor communication resulting in high information needs, which may be alleviated by providing PCPs detailed SCPs [34]. PCPs’ poor knowledge of survivors’ follow‐up needs is well documented [19], [35], [36]. Their general‐level knowledge, and low awareness of issues pertinent to pediatric cancer survivorship, may be due to their being less "invested" in this population due to the small number of CCS in any primary care practice. This contrasts with their high self‐reported knowledge and confidence (100%) for adult cancer survivors. A significant minority of PCPs are unwilling to accept exclusive responsibility for cancer survivors, either adult or children [37], [38]. Rather, PCPs prefer a shared care follow‐up model, which evidence suggests helps survivors overcome distrust in providers [32]. Further clarification of primary and tertiary providers’ responsibilities is needed, and may improve the confidence of all parties and the quality of care delivered by reducing overlap or missed opportunities for surveillance [39], [40].

Limitations/Strengths and Future Directions

Stage 1 represented many survivors engaged in specialist‐led follow‐up care. The literature suggests survivors/parents typically prefer the model of care in which they are engaged, possibly influencing the results [41]. Survivors’ and PCPs’ confidence may have also been influenced by other factors not explored in detail here (e.g., survivors’ level of risk), and further systematic evaluation is required. Although we did not observe any notable differences in adult or parent responses based on their sex or time since diagnosis, future studies should more systematically assess these factors and their potential influence on barriers to PCP‐led care. Identifying factors associated with survivors’/parents’ willingness to receive follow‐up from their PCP may assist in identifying more targeted approaches to enhance self‐management and engagement in follow‐up. Future research should target male survivors, who were somewhat underrepresented in our study.

The moderate Stage 2 response rate may be considered a limitation; however, we observed no systematic differences in nonrespondents (besides gender), and we collected data until we achieved a broad sample and reached thematic saturation [42]. Although we collected PCPs’ years practicing, we did not ask their age, which may influence their responses. PCPs’ receipt of SCPs and patient letters may have been subject to potential recall bias and therefore misrepresented. However, we encouraged PCPs to conduct interviews in front of their medical records, and some PCPs admitted to seeing these documents for the first time during interviews. Improving SCP content/format as suggested by PCPs may increase their utility and transfer between health professionals. This highlights the importance of the oncology team educating survivors and equipping them as advocates for their health as they traverse the adult health care system.

Conclusion

Survivors and parents lack confidence in PCPs to provide their ongoing survivorship care. Involving PCPs at all stages, and introducing the notion of transition, with shared‐care, to PCPs to survivors earlier (i.e., during treatment and early survivorship), may improve the familiarity and importance of adult follow‐up while decreasing reluctance to seek PCP‐led care. PCPs are well placed to offer holistic care but also lack confidence. PCPs proposed additional support, more appropriate training, highly personalized and prescriptive instructions, and ongoing liaison from tertiary services to improve their confidence and ability to deliver survivorship care. In turn, this may also increase survivors’/parents’ confidence in them, reducing disengagement particularly after transition from the pediatric setting. Equipping survivors with knowledge and skills to advocate for their care is an important step in the process. Together, these efforts may ultimately reduce the pressure on oncologist‐based follow‐up from the growing population of CCS, while encouraging participation in long‐term, personalized follow‐up for survivors of all levels of risk.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the contribution of Barbora Pekarova, Amanda Tillmann, Vivian Nguyen, Brittany McGill, Janine Vetsch, Kate Hetherington, Rebecca Hill, and Mary‐Ellen Brierley. We also thank the survivors, parents, and primary care physicians that participated as well as each of the recruiting sites for the ANZCHOG Survivorship Study, including Sydney Children's Hospital Randwick, the Children's Hospital at Westmead, John Hunter Children's Hospital, the Royal Children's Hospital Melbourne, Monash Children's Hospital Melbourne, Royal Children's Hospital Brisbane, Princess Margaret Children's Hospital, Women's and Children's Hospital Adelaide, and in New Zealand, Starship Children's Health, Wellington Hospital, and Christchurch hospital.

The members of the ANZCHOG Survivorship Study Group in alphabetical order: Dr. Frank Alvaro, Prof. Richard J. Cohn, Dr. Rob Corbett, Dr. Peter Downie, Karen Egan, Sarah Ellis, Prof. Jon Emery, Dr. Joanna E. Fardell, Tali Foreman, Dr. Melissa Gabriel, Prof. Afaf Girgis, Kerrie Graham, Karen A. Johnston, Dr. Janelle Jones, Dr. Liane Lockwood, Dr. Ann Maguire, Dr. Maria McCarthy, Dr. Jordana McLoone, Dr. Francoise Mechinaud, Sinead Molloy, Lyndal Moore, Dr. Michael Osborn, Christina Signorelli, Dr. Jane Skeen, Dr. Heather Tapp, Tracy Till, Jo Truscott, Kate Turpin, Prof. Claire E. Wakefield, Dr. Thomas Walwyn, and Kathy Yallop.

The Behavioural Sciences Unit is proudly supported by the Kids with Cancer Foundation. C.S. and J.E.F. are supported by The Kids’ Cancer Project. C.E.W. is supported by a Career Development Fellowship from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (APP1067501). A.G. is funded through Cancer Institute NSW grants. The BSU's survivorship research program is funded by the Kids Cancer Alliance, The Kids’ Cancer Project and a Cancer Council NSW Program Grant (PG16‐02) with the support of the Estate of the Late Harry McPaul. These funding bodies did not have any role in the study design, data collection and analysis, manuscript writing, or the decision to publish.

Contributor Information

Christina Signorelli, Email: c.signorelli@unsw.edu.au.

Collaborators: on behalf of the Anzchog Survivorship Study Group, Dr. Frank Alvaro, Prof. Richard J. Cohn, Dr. Rob Corbett, Dr. Peter Downie, Karen Egan, Sarah Ellis, Prof. Jon Emery, Dr. Joanna E. Fardell, Tali Foreman, Dr. Melissa Gabriel, Prof. Afaf Girgis, Kerrie Graham, Karen A. Johnston, Dr. Janelle Jones, Dr. Liane Lockwood, Dr. Ann Maguire, Dr. Maria McCarthy, Dr. Jordana McLoone, Dr. Francoise Mechinaud, Sinead Molloy, Lyndal Moore, Dr. Michael Osborn, Christina Signorelli, Dr. Jane Skeen, Dr. Heather Tapp, Tracy Till, Jo Truscott, Kate Turpin, Prof. Claire E. Wakefield, Dr. Thomas Walwyn, and Kathy Yallop

Author Contributions

Conception/design: Christina Signorelli, Claire E. Wakefield, Joanna E. Fardell, Tali Foreman, Karen A. Johnston, Jon Emery, Elysia Thornton‐Benko, Afaf Girgis, Hanne C. Lie, Richard J. Cohn

Provision of study material or patients: Christina Signorelli, Claire E. Wakefield, Joanna E. Fardell, Richard J. Cohn

Collection and/or assembly of data: Christina Signorelli, Tali Foreman

Data analysis and interpretation: Christina Signorelli, Claire E. Wakefield, Joanna E. Fardell, Richard J. Cohn

Manuscript writing: Christina Signorelli, Claire E. Wakefield, Joanna E. Fardell, Tali Foreman, Karen A. Johnston, Jon Emery, Elysia Thornton‐Benko, Afaf Girgis, Hanne C. Lie, Richard J. Cohn

Final approval of manuscript: Christina Signorelli, Claire E. Wakefield, Joanna E. Fardell, Tali Foreman, Karen A. Johnston, Jon Emery, Elysia Thornton‐Benko, Afaf Girgis, Hanne C. Lie, Richard J. Cohn

Disclosures

The authors indicated no financial relationships.

References

- 1.Signorelli C, Fardell JE, Wakefield CE et al. The cost of cure: Chronic conditions in survivors of child, adolescent, and young adult cancers In: Koczwara B, ed. Cancer and Chronic Conditions. Singapore: Springer, 2016:371–420. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mittal N, Kent P. Long‐term survivors of childhood cancer: The late effects of therapy. In: Wonders K, ed. Pediatric Cancer Survivors. London: IntechOpen; Available at https://www.intechopen.com/books/pediatric‐cancer‐survivors/long‐term‐survivors‐of‐childhood‐cancer‐the‐late‐effects‐of‐therapy. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Phillips SM, Padgett LS, Leisenring WM et al. Survivors of childhood cancer in the United States: Prevalence and burden of morbidity. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2015;24:653–663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schwartz CL. Long‐term survivors of childhood cancer: The late effects of therapy. The Oncologist 1999;4:45–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nathan PC, Ford JS, Henderson T.O. et al. Health behaviors, medical care, and interventions to promote healthy living in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study cohort. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:2363–2373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Research Council . From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Friedman DL, Freyer DR, Levitt GA. Models of care for survivors of childhood cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2006;46:159–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Joseph E, Clark R, Berman C et al. Screening childhood cancer survivors for breast cancer. The Oncologist 1997;2:228–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Michel G, Gianinazzi M, Eiser C et al. Preferences for long‐term follow‐up care in childhood cancer survivors. Eur J Cancer Care 2016;25:1024–1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hudson SV, Miller SM, Hemler J et al. Adult cancer survivors discuss follow‐up in primary care: ‘Not what I want, but maybe what I need’. Ann Fam Med 2012;10:418–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheung WY, Aziz N, Noone AM et al. Physician preferences and attitudes regarding different models of cancer survivorship care: A comparison of primary care providers and oncologists. J Cancer Surviv 2013;7:343–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Signorelli C, Wakefield CE, McLoone JK et al. Models of childhood cancer survivorship care in Australia and New Zealand: Strengths and challenges. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol 2017;13:407–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Warren JL, Mariotto AB, Meekins A et al. Current and future utilization of services from medical oncologists. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:3242–3247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berg CJ, Stratton E, Esiashvili N et al. Young adult cancer survivors' experience with cancer treatment and follow‐up care and perceptions of barriers to engaging in recommended care. J Cancer Educ 2016;31:430–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nathan PC, Greenberg ML, Ness KK et al. Medical care in long‐term survivors of childhood cancer: A report from the childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:4401–4409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller KA, Wojcik KY, Ramirez CN et al. Supporting long‐term follow‐up of young adult survivors of childhood cancer: Correlates of healthcare self‐efficacy. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2017;64:358–363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fardell J, Wakefield C, Signorelli C et al. Transition of childhood cancer survivors to adult care: The survivor perspective. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2017;64(6). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iyer NS, Mitchell HR, Zheng DJ et al. Experiences with the survivorship care plan in primary care providers of childhood cancer survivors: A mixed methods approach. Support Care Cancer 2017;25:1547–1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lie HC, Mellblom AV, Brekke M et al. Experiences with late effects‐related care and preferences for long‐term follow‐up care among adult survivors of childhood lymphoma. Support Care Cancer 2017;25:2445–2454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Henderson TO , Friedman DL, Meadows AT. Childhood cancer survivors: Transition to adult‐focused risk‐based care. Pediatrics 2010;126:129–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Franco B, Dharmakulaseelan L, McAndrew A et al. The experiences of cancer survivors while transitioning from tertiary to primary care. Curr Oncol 2016;23:378–385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nathan PC, Daugherty CK, Wroblewski KE et al. Family physician preferences and knowledge gaps regarding the care of adolescent and young adult survivors of childhood cancer. J Cancer Surviv 2013;7:275–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Signorelli C, Wakefield CE, Fardell JE et al. The impact of long‐term follow‐up care for childhood cancer survivors: A systematic review. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2017;114:131–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kirchhoff AC, Montenegro RE, Warner EL et al. Childhood cancer survivors' primary care and follow‐up experiences. Support Care Cancer 2014;22:1629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vetsch J, Fardell JE, Wakefield CE et al. “Forewarned and forearmed”: Long‐term childhood cancer survivors’ and parents’ information needs and implications for survivorship models of care. Patient Educ Couns 2017;100:355–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Signorelli C, Wakefield CE, Fardell JE et al. Recruiting primary care physicians to qualitative research: Experiences and recommendations from a childhood cancer survivorship study. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2017;65(1). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Daniel G, Wakefield C, Ryan B et al. Accommodation in pediatric oncology: parental experiences, preferences and unmet needs. Rural Remote Health 2013;13:2005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Szalda D, Pierce L, Hobbie W et al. Engagement and experience with cancer‐related follow‐up care among young adult survivors of childhood cancer after transfer to adult care. J Cancer Surviv 2016;10:342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mertens AC, Cotter KL, Foster BM et al. Improving health care for adult survivors of childhood cancer: Recommendations from a delphi panel of health policy experts. Health Policy 2004;69:169–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coindard G, Barrière J, Vega A et al. What role does the general practitioner in France play among cancer patients during the initial treatment phase with intravenous chemotherapy? A qualitative study. Eur J Gen Pract 2016;22:96–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ducassou S, Chipi M, Pouyade A et al. Impact of shared care program in follow‐up of childhood cancer survivors: An intervention study. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2017;64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sadak KT, Neglia JP, Freyer DR et al. Identifying metrics of success for transitional care practices in childhood cancer survivorship: A qualitative study of survivorship providers. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2017;64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meacham LR, Edwards PJ, Cherven BO et al. Primary care providers as partners in long‐term follow‐up of pediatric cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv 2012;6:270–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Berger C, Casagranda L, Faure‐Conter C et al. Long‐term follow‐up consultation after childhood cancer in the Rho^ne‐Alpes region of France: Feedback from adult survivors and their general practitioners. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol 2017;6:524–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Henderson TO , Hlubocky FJ, Wroblewski KE et al. Physician preferences and knowledge gaps regarding the care of childhood cancer survivors: A mailed survey of pediatric oncologists. J Clin Oncol 2009;28:878–883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Del Giudice ME, Grunfeld E, Harvey BJ et al. Primary care physicians' views of routine follow‐up care of cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:3338–3345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nissen MJ, Beran MS, Lee MW et al. Views of primary care providers on follow‐up care of cancer patients. Fam Med 2007;39:477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nandakumar B, Fardell JE, Wakefield CE et al. Attitudes and experiences of childhood cancer survivors transitioning from pediatric care to adult care. Support Care Cancer 2018;26:2743–2750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nass SJ, Beaupin LK, Demark‐Wahnefried W et al. Identifying and addressing the needs of adolescents and young adults with cancer: Summary of an Institute of Medicine workshop. The Oncologist 2015;20:186–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vetsch J, Rueegg C, Mader L et al. Parents' preferences for the organisation of long‐term follow‐up of childhood cancer survivors. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2018;27:e12649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wilmot A. Designing sampling strategies for qualitative social research: With particular reference to the Office for National Statistics' Qualitative Respondent Register. Survey Methodology Bulletin Office For National. Statistics 2005;56:53. [Google Scholar]