This article reports on the first approved immunotherapy for acute myeloid leukemia.

Keywords: Acute myeloid leukemia, Mylotarg, Gemtuzumab ozogamicin, Veno‐occlusive disease, European Medicines Agency

Abstract

On February 22, 2018, the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) adopted a positive opinion, recommending the granting of a marketing authorization for the medicinal product gemtuzumab ozogamicin (Mylotarg; Pfizer, New York City, NY), intended for the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia. Mylotarg was designated as an orphan medicinal product on October 18, 2000. The applicant for this medicinal product was Pfizer Limited (marketing authorization now held by Pfizer Europe MA EEIG).

The demonstrated benefit with Mylotarg is improvement in event‐free survival. This has been shown in the pivotal ALFA‐0701 (MF‐3) study. In addition, an individual patient data meta‐analysis from five randomized controlled trials (3,325 patients) showed that the addition of Mylotarg significantly reduced the risk of relapse (odds ratio [OR] 0.81; 95% CI: 0.73–0.90; p = .0001), and improved overall survival at 5 years (OR 0.90; 95% CI: 0.82–0.98; p = .01) [Lancet Oncol 2014;15:986–996]. The most common (>30%) side effects of Mylotarg when used together with daunorubicin and cytarabine are hemorrhage and infection.

The full indication is as follows: “Mylotarg is indicated for combination therapy with daunorubicin (DNR) and cytarabine (AraC) for the treatment of patients age 15 years and above with previously untreated, de novo CD33‐positive acute myeloid leukemia (AML), except acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL).”

The objective of this article is to summarize the scientific review done by the CHMP of the application leading to regulatory approval in the European Union. The full scientific assessment report and product information, including the Summary of Product Characteristics, are available on the European Medicines Agency website (www.ema.europa.eu).

Implications for Practice.

This article reflects the scientific assessment of Mylotarg (gemtuzumab ozogamicin; Pfizer, New York City, NY) use for the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia based on important contributions from the rapporteur and co‐rapporteur assessment teams, Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use members, and additional experts following the application for a marketing authorization from the company. It's a unique opportunity to look at the data from a regulatory point of view and the importance of assessing the benefit‐risk.

Background

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is a heterogeneous disease; the classification is based on morphologic, cytogenetic, molecular, and immunophenotypic features, which, along with baseline patient's characteristics such as age and performance status (PS), influence outcome and treatment recommendations [1]. Among these, baseline cytogenetic risks constitute one of the most significant prognostic markers of disease outcome [2]. Age is the most prominent patient‐specific risk factor, and cytogenetics is the most disease‐specific risk factor.

In AML, leukemic blasts replace normal blood cells in bone marrow and peripheral blood, which leads to anemia, neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia. This is associated with symptoms of fatigue, shortness of breath, disturbed wound healing, infections, and bleeding. If left untreated, AML results in death within a few weeks to months.

Long‐term survival in adult patients with AML is only 35%–40% for patients ≤60 years of age, and drops to 5%–15% in patients who are >60 years of age. Older patients more often have adverse cytogenetic abnormalities, clinically significant coexisting conditions, or both [3]. The majority of patients with AML will have relapsed disease within 3 years [4].

The general therapeutic strategy in patients with AML has not changed substantially in more than 40 years. The standard regimen daunorubicin 3 + cytarabine 7 (DA), established in 1973, consists of three consecutive daily infusions of daunorubicin (DNR) and 7 days of continuous infusion of cytarabine (AraC).

For many years, the standard treatment has consisted of an induction treatment in order to achieve complete remission (CR). When CR has been obtained, two to four courses of consolidation therapy usually are performed, in order to eliminate undetected residual disease. Patients who do not achieve CR after the induction have a poor prognosis. Although some patients older than 60 years, with Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) PS 0–2 and minimal comorbidity, may benefit from standard 3 + 7, the therapeutic options for patients with poor functional status or comorbidities often include low‐intensity therapy such as subcutaneous AraC, azacitidine, or decitabine. A high proportion of patients with AML, whether in CR after induction therapy or not, will have relapsed disease within 4 years. The introduction of allogeneic stem cell transplantation has improved the outcome in a selected group of patients [5], [6], [7].

In the European Union, recently approved agents include decitabine (Dacogen), which is authorized for the treatment of adult patients with newly diagnosed de novo or secondary AML, according to the World Health Organization classification, who are not candidates for standard induction chemotherapy. Azacitidine (Vidaza, Celgene, Summit, NJ) is also authorized for the treatment of adult patients who are not eligible for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) with AML, 20%–30 % blasts, and multilineage dysplasia.

Nonetheless, new therapeutic options that could improve survival of patients and prevent or delay relapse of the disease remain an important unmet medical need for patients with previously untreated de novo AML.

Gemtuzumab ozogamicin (GO) consists of a humanized anti‐CD33 monoclonal antibody linked to calicheamicin, a potent antitumor antibiotic [8]. GO binds to CD33, an antigen expressed on the surface of more than 90% of AML blast cells. Binding of GO is followed by internalization of the GO‐CD33 complex and toxin release intracellularly leading to DNA damage and cell death [9].

In studies of older patients with AML in first relapse, tolerable toxicity and a response rate of 26% was reported following two infusions of GO 9 mg/m2, although full platelet recovery did not occur in roughly half of responders [10].

These results led to regulatory approval of the drug in the U.S. for use in older patients in first relapse for whom standard therapy was unsuitable, setting the stage for its evaluation in patients with newly diagnosed high‐risk AML/myelodysplastic syndrome. However, GO was voluntarily withdrawn from the market in 2010 on the basis of preliminary results from a phase III study by the Southwest Oncology Group (SWOG) that compared the addition of single infusion of 6 mg/m2 on day 4 of the first remission‐induction chemotherapy (DA). The overall efficacy, as measured by the relapse‐free survival (RFS) and the overall survival (OS), was similar in both groups. However, the induction mortality was increased in the DA + GO group, at 5% versus 1% in the DA group [11].

In the National Cancer Research Institute (NCRI) AML17 trial, GO was administered as a single infusion on day 1 of the remission‐induction chemotherapy course with patients randomized to the 3 mg/m2 or the 6 mg/m2 dose [12]. There was no difference in overall response rate (defined as CR or CR with incomplete hematopoietic recovery) between the two evaluated dose levels. All patients received various schedules of chemotherapy without GO after the first remission‐induction course, depending on the risk status after the first remission‐induction course and the presence of fms‐related tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3) abnormalities. The overall survival and relapse risk did not differ. This large randomized study did not show any significant benefit of using GO at the 6 mg/m2 dose; therefore, the outcome of this study suggested that where a single‐dose schedule is used, the 3 mg/m2 dose might be preferred [13].

The question remains as to whether fractionated dosing using the lower dose of 3 mg/m2 results in better outcome or whether addition of GO to the consolidation course(s) may increase the benefit without additional toxicity, which may take advantage of the CD33‐re‐expression that occurs after initial exposure to GO. The French ALFA group used a GO schedule of 3 mg/m2/day on days 1, 4, and 7 during induction chemotherapy, followed by a single dose in each of two postinduction courses, in patients aged 50–70 years with untreated de novo AML. This study was considered pivotal in the assessment of Mylotarg (gemtuzumab ozogamicin; Pfizer, New York City, NY), and its evaluation is discussed under clinical efficacy later in the article. Complete response was 81%, and event‐free survival (EFS) at 2 years was 40.8% compared with 17.1% in the control group (p = .003) [14].

Nonclinical Aspects

The hP67.6(gemtuzumab) antibody exhibited a high affinity for CD33, with an average KD of 0.073 nM. Gemtuzumab ozogamicin had an EC50 value of 11.6 nM (1.69 μg/mL), which was comparable to hP67.6 antibody, indicating that conjugation of the linker‐payload to the hP67.6 antibody does not alter its binding affinity to the cells. Binding and internalization analysis of radioiodinated hP67.6 antibody demonstrated efficient delivery of the cytotoxic payload of the product into CD33‐expressing HL‐60 cells, and payload release was determined at a pH value of 4.5, which is consistent with the pH in the acidic lysosomal vesicular compartment of the cell.

Gemtuzumab ozogamicin exhibited in vitro cytotoxicity in CD33+ cells, and inhibition of colony growth in blood or bone marrow specimens from patients with AML, but not in normal samples.

Gemtuzumab Ozogamicin Activity in Primary Human Leukemic Bone Marrow Samples

In order to assess the ability of gemtuzumab ozogamicin to inhibit cell growth from progenitor cells in patients, colony‐forming cell growth was assessed in diagnostic blood or bone marrow specimens from patients with AML and normal healthy donors (MIRACL‐26757). Inhibition of colony growth was observed in all gemtuzumab ozogamicin‐treated samples. In the 27 samples incubated with 7.0 nM gemtuzumab ozogamicin, 15 had >25% inhibition, of which 12 had >60% inhibition, whereas in samples incubated with 1.4 nM gemtuzumab ozogamicin, 10 had >25% inhibition, of which 4 had >60% inhibition. Normal bone marrow samples (n = 3) were exposed to gemtuzumab ozogamicin of 7–28 nM calicheamicin payload and showed no inhibition of colony growth.

Antitumor Effects of Single‐Dose Gemtuzumab Ozogamicin in the HL‐60 Mouse Xenograft Model

The in vivo antitumor effects of a single i.p. dose of gemtuzumab ozogamicin were studied in a CD33‐positive HL‐60 mouse xenograft model dosed with 30, 60, 90, and 120 mg/m2 of gemtuzumab ozogamicin 8 days after subcutaneous implantation of tumor cells. A single dose of 120 mg/m2 of gemtuzumab ozogamicin resulted in 20% survival. The 30 mg/m2 dose resulted in 100% survival, with 40% of the mice tumor free, whereas at 60 and 90 mg/m2 gemtuzumab ozogamicin, survival was 80%, with 60% of the mice tumor free. Single‐dose gemtuzumab ozogamicin showed antitumor efficacy but had a poor survival rate at higher doses in mice at the doses tested; therefore, a fractionated dosing approach was explored as a possible improvement to the dosing regimen.

Antitumor Effects of Gemtuzumab Ozogamicin in Combination with DA Chemotherapy in AML Xenograft Mouse Model with Leukemic Stem Cell Outgrowth (Study 082753)

High‐dose DA chemotherapy (cytarabine at 15 mg/kg/day subcutaneously for 5 days and daunorubicin at 1.5 mg/kg on days 1, 3, and 5) resulted in elimination of human AML CD33 + CD45+ blasts in the peripheral blood, but residual disease remained in the bone marrow. Combining DA chemotherapy with GO compared with either therapy alone resulted in nearly complete elimination of CD33+/CD45+ human tumor cells from both the peripheral blood and bone marrow [15].

The primary target organ toxicity in rats and/or cynomolgus monkeys included the liver, bone marrow and lymphoid organs, hematology parameters (decreased red blood cell mass and white blood cell counts, mainly lymphocytes), kidney, eye, and male and female reproductive organs. Gemtuzumab ozogamicin does not bind to rat or monkey CD33, and findings were attributed to target‐independent toxicity associated with conjugated and/or unconjugated calicheamicin. The effects on liver, kidney, and male reproductive organs in rats, and on lymphoid tissues in monkeys (approximately 18 times for rats and 36 times for monkeys, the human clinical exposure after the third human dose of 3 mg/m2 based on AUC168), were not reversible after a 4‐week nondosing period in 6‐week toxicity studies.

Clinical Pharmacology

Pharmacokinetic data were obtained from eight phase I and phase II clinical trials with gemtuzumab ozogamicin, including one pediatric phase I study, one phase II trial in elderly patients aged ≥60 years only, and one phase I/II trial conducted in Japanese patients.

In patients, the total volume of distribution of hP67.6 antibody (sum of V1 [10 L] and V2 [15 L]) was found to be approximately 25 L. The terminal plasma half‐life (t½) for hP67.6 was predicted to be approximately 160 hours for a typical patient at the recommended dose level (3 mg/m2) of Mylotarg.

Based on a population pharmacokinetic (PK) analysis, age, race, and gender did not significantly affect gemtuzumab ozogamicin disposition. No dose adjustment is required in elderly patients (≥65 years).

The results of the population modelling showed that the PK behavior of gemtuzumab ozogamicin (hP67.6 antibody and unconjugated calicheamicin) is similar between adult and pediatric patients with AML following the 9 mg/m2 dosing regimen.

Based on the submitted data at the time, safety and efficacy of Mylotarg in patients less than 15 years of age has not been established. Therefore, a recommendation on a posology could not be made at the moment. However, current ongoing pediatric studies would be able to clarify this further in the future.

Population PK analysis was conducted to determine the interaction potential of DNR, AraC, and hydroxyurea with GO. The results showed that concomitant use of DNR, AraC, or hydroxyurea did not impact the PK of GO.

Clinical Efficacy

Dose Response Studies

Mylotarg was initially developed as monotherapy for patients with AML in first relapse. The initial single‐agent dosing recommendation was 9 mg/m2, infused over a 2‐hour period, with a total of two doses with a 14‐day treatment‐free interval [16].

This dosing schedule had been chosen based on the results from the dose escalation phase I study 101, during which the dose was not escalated beyond 9 mg/m2 because of myelosuppression, even though no prospectively defined dose‐limiting toxicity had been encountered.

The MyloFrance 1 study evaluated the fractionated Mylotarg dosing regimen. MyloFrance 1 was a multicenter, phase II uncontrolled trial to assess the safety of fractionated doses of GO, given at a dose of 3 mg/m2 on days 1, 4, and 7 (max of 5 mg per dose) in adult patients aged 18 years and above with CD33‐positive AML in first relapse. There were no signs of prolonged myelosuppression [17].

No grade 3 or 4 liver toxicity was observed. No episodes of veno‐occlusive disease with immunodeficiency (VOD) occurred. The efficacy results were comparable to phase I data using the 9 mg/m2 dose.

The MyloFrance 2 study was a multicenter, phase I/II dose‐escalation study aimed to determine the optimal doses of daunorubicin and cytarabine in combination with fractionated doses of Mylotarg (3 mg/m2 on days 1, 4, and 7) in patients aged 50–70 years with CD33‐positive AML in first relapse and adequate PS (ECOG 0–1) and organ function. The primary endpoint was to determine the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) for DNR and AraC doses in combination with 3 mg/m2 GO on days 1, 4, and 7 (max of 5 mg per dose), among three different dose schedules, namely (45, 100), (60, 100), and (60, 200) mg/m2 [18].

Analyses of the different GO dosing regimens (3 mg/m2 single dose, 3 × 3 mg/m2 fractionated, and 6 mg/m2 single dose) during induction for the following safety endpoint (30‐day and 60‐day mortality, hemorrhage, infections, hepatotoxicity, and hematotoxicity) in the individual patient data (IPD) meta‐analysis showed that the single dose of 6 mg/m2 resulted in a significant increase in early mortality; however, the 3 × 3 mg/m2 fractionated GO regimen showed similar 30‐day and 60‐day mortality rates to the single 3 mg/m2 GO regimen. The risk of grade 3/4 hemorrhage, grade 3/4 infections, and hepatotoxicity seems not increased with the 3 × 3 mg/m2 fractionated Mylotarg regimen compared with single 3 mg/m2 or 6 mg/m2. The risk of persistent neutropenia was not increased by the addition of GO to the intensive chemotherapy, but the risk of persistent thrombocytopenia increased with the 3 × 3 mg/m2 fractionated regimen.

Overall, this confirmed the 3 × 3 mg/m2 fractionated GO dosing regimen in combination with DNR 60 mg/m2 for 3 days and AraC 200 mg/m2 for 7 days to be tolerable, with comparable efficacy results to data using the 9 mg/m2 dose.

Efficacy

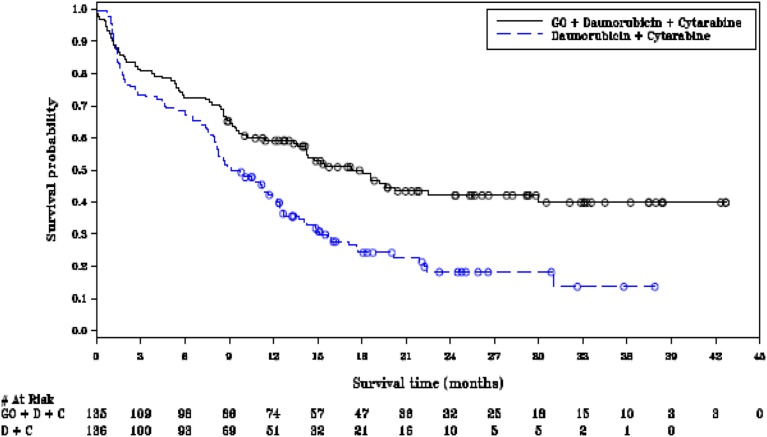

The pivotal phase III ALFA‐0701 study was a multicenter, randomized, comparative phase III study of fractionated doses of the monoclonal antibody gemtuzumab ozogamicin (Mylotarg) in addition to daunorubicin + cytarabine versus daunorubicin + cytarabine alone for induction and consolidation therapy in patients with acute myeloid leukemia aged 50 to 70 years. The study clearly showed an improvement in EFS, through prolongation of remission following initial chemotherapy, rather than increasing the number of patients who achieved complete remission, as confirmed by the absence of a statistically significant difference in the objective response rate (ORR) (Fig. 1). EFS rate at 2 years was 42.1% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 32.9–51.0) in the GO arm and 18.2% (95% CI: 11.1–26.7) in the control, and at 3 years was 39.8% (95% CI: 30.2–49.3) in the GO arm and 13.6% (95% CI: 5.8–24.8) in the control arm.

Figure 1.

Kaplan‐Meier plot of event‐free survival (ALFA‐0701 study, cutoff date August 2011).

Abbreviations: D + C, daunorubicin + cytarabine; GO, gemtuzumab ozogamicin.

A blinded independent review confirmed the investigator‐assessed event‐free survival results (August 1, 2011; hazard ratio [HR] 0.66; 95% CI: 0.49–0.89; two‐sided p = .006), corresponding to a 34% reduction in risk of events in the gemtuzumab ozogamicin versus control arm. Final overall survival (April 30, 2013) favored gemtuzumab ozogamicin but was not significant. No differences were observed between arms in early death rate [19]. The final EFS HR and CI were HR 0.562; 95% CI: 0.415–0.762.

Subgroup analyses of EFS indicated a more encouraging treatment effect with the Mylotarg combination in patients with favorable/intermediate risk cytogenetics (HR 0.460; 95% CI: 0.313–0.676) versus unfavorable (HR 1.111; 95% CI: 0.633–1.949). Reflecting on the differences observed for the different risk groups, it can be hypothesized that patients with adverse cytogenetics who receive fractioned low dose of Mylotarg seem to exhibit less deep responses, translating into shorter, not statistically significant periods of remission. It can be argued that, based on distinct biological characteristics, with the pathophysiological route causes yet to be fully elucidated, the hard‐to‐treat poor cytogenetic patient group is less susceptible to Mylotarg‐based induction chemotherapy. Hence, there is a need to individually consider the benefit/risk profile in patients, particularly with adverse cytogenetics, once results of the cytogenetic test become available.

The first analysis of the ALFA‐0701 study, testing the addition of GO to standard treatment in de novo AML patients aged 50–70 years showed a benefit in EFS (primary endpoint of the study; p = .0018), RFS (p = .0009), and OS (p = .03) [20].

This application was a resubmission. In 2007, the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) considered that the Quality package for Mylotarg was generally acceptable. During development, a significant level of amino acid substitution (AAS) was discovered at multiple sites within the antibody part of GO. Retrospective analyses show that there was a shift toward elevated levels of AAS in more recent batches, although it has been consistently present at low levels in earlier gemtuzumab batches. However, no clinical impact of the shift in the AAS could be observed based on the comparability exercise. No clear efficacy differences were observed in the data submitted.

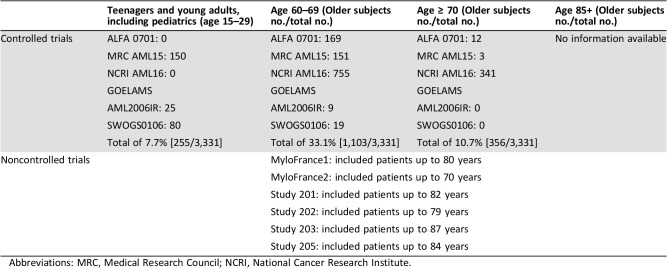

In a meta‐analysis of IPD to assess the efficacy of adding gemtuzumab ozogamicin to induction chemotherapy in adult patients with acute myeloid leukemia, a total of 3,331 patients were included from the following studies (ALFA‐0701, Medical Research Council [MRC] AML15, NCRI AML16, SWOG S0106, and Groupe Ouest Est d'Etude des Leucémies aiguës et Autres Maladies du Sang AML2006IR) [16]. Of these, 1,663 patients (49.9%) were randomized to GO and 1,668 patients (50.1%) were randomized to No GO. There were no postrandomization exclusions from the meta‐analysis. As expected based on the age distribution of AML, the largest age group of patients treated on these studies was ages 60–69 (33% of all patients); those aged 15–29 only made up 7.7% and those aged 70 and older only 10.7% of the included patients. Only 22 patients were younger than age 18. Sensitivity analysis indicated no difference due to age. Slightly more male patients were included (55.4%); 93% of patients had a PS of 0 or 1; 88.1% were treated for de novo AML, with 75.7% having had cytarabine and daunorubicin‐based chemotherapy; the majority were in the favorable/intermediate cytogenetic and European LeukemiaNet (ELN) risk group (MRC cytogenetics 62.3%; ELN 44.9% [62.3% imputed ELN]), with negative FLT3 or nucleophosmin‐1 (NPM1) status; the minority (12.9%) had known CD33 expression <30%. However, the high percentage of data not known needs to be appreciated as well (i.e., ELN risk group 37.6%, imputed ELN 20.3%, FLT3 46.2%, NPM1 50.8%, CD33 positivity 47.5%).

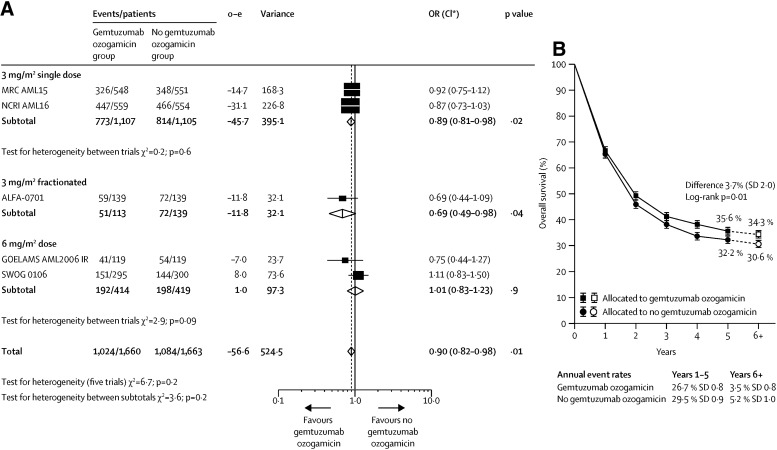

The addition of gemtuzumab ozogamicin did not increase the proportion of patients achieving complete remission with or without complete peripheral count recovery (odds ratio [OR] 0.91; 95% CI: 0.77–1·07; p = .3). However, it did significantly reduce the risk of relapse (OR 0.81; 95% CI: 0.73–0.90; p = .0001) and improved overall survival (OR 0.90; 95% CI: 0.82–0.98; p = .01; Fig. 2) [16]. The secondary endpoint of EFS was prolonged in the GO arm compared with No GO (OR 0.85; 95% CI: 0.78–0.93; two‐sided stratified log‐rank p = .0002), corresponding to a 15% reduction in events, with no heterogeneity by dose or trial within dose group.

Figure 2.

Forest plot. Effect of gemtuzumab ozogamicin on overall survival. Meta‐analysis. (A): Forest plot; the size of the boxes is proportional to the amount of data contained in each data line. (B): Absolute survival; error bars show SDs; dashed lines and white boxes represent projections beyond 5 years. o—e=observed minus expected events. *CIs are 95% CIs for totals and subtotals, and 99% CIs for individual trials.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; MRC, Medical Research Council; NCRI, National Cancer Research Institute; OR, odds ratio.

Reproduced from [16] with permission. © 2014 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

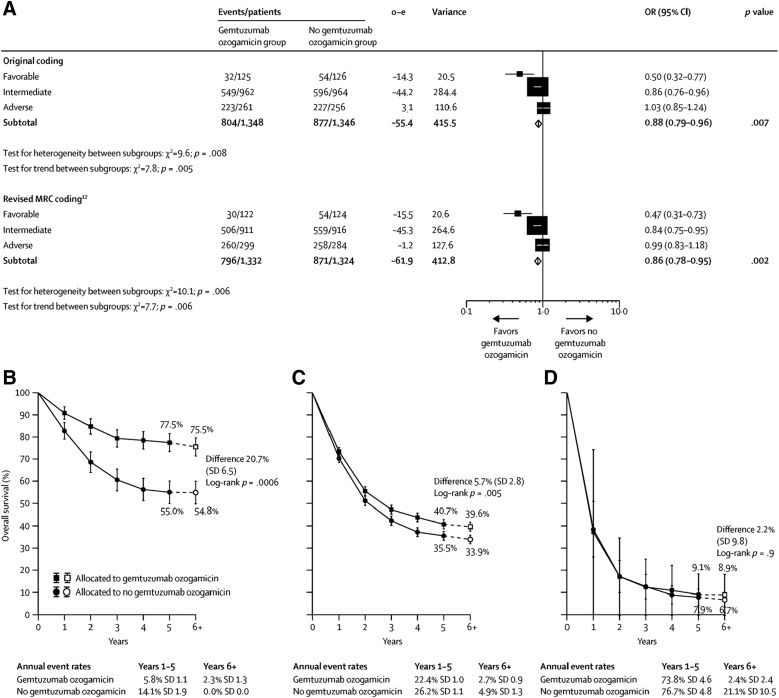

At 6 years, the absolute survival benefit was especially apparent in patients with favorable cytogenetic characteristics (20.7%; OR 0.47; 95% CI: 0.31–0.73; p = .0006) but was also seen in those with intermediate characteristics (5.7%; OR 0.84; 95% CI: 0.75–0·95; p = .005). Patients with adverse cytogenetic characteristics did not benefit (2.2%; OR 0.99; 95% CI: 0.83–1.18; p = .9; Fig. 3). Doses of 3 mg/m2 were associated with fewer early deaths than doses of 6 mg/m2, with equal efficacy [16].

Figure 3.

Meta‐analysis of overall survival stratified by cytogenetic characteristics. (A): Overall survival, stratified by cytogenetic characteristics; the size of the boxes is proportional to the amount of data contained in each data line. (B): Absolute survival for patients with favourable cytogenetic characteristics. (C): Absolute survival for patients with intermediate cytogenetic characteristics. (D): Absolute survival for patients with adverse cytogenetic characteristics. Patients with insufficient karyotype data or fewer than 20 metaphases are classified as unknown and excluded from the stratified analysis. Error bars show SDs. Dashed lines and white boxes represent projections beyond 5 years.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; MRC, Medical Research Council; OR, odds ratio.

Reproduced from [16] with permission. © 2014 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Supportive Studies

Out of the 19 clinical trials submitted, the 5 studies included in the meta‐analysis were considered supportive of the intended indication of treatment of patients with de novo AML, although only the ALFA‐0701 study supports the proposed posology.

The overall results of these trials were that remission rates were not improved, although relapse was reduced in four of five trials, with a significant survival benefit observed in NCRI trial AML16 comparing a single dose of GO (3 mg/m2) to induction chemotherapy, consisting of either DA 3 + 10 in Course 1 and 3 + 8 in Course 2 or DClo (DNR plus clofarabine; data not shown).

Pediatric Data

A randomized study (COG AAML0531) [21] evaluated standard chemotherapy alone or combined with Mylotarg in 1,022 newly diagnosed children (94.3% of patients <18 years of age) and young adults (5.7% of patients); median age was 9.7 years (range: 0–29 years). Patients with de novo AML were randomly assigned to either standard five‐course chemotherapy alone or to the same chemotherapy with two doses of Mylotarg (3 mg/m2/dose) administered once in induction Course 1 and once in intensification Course 2. The study demonstrated that the addition of Mylotarg to intensive chemotherapy improved EFS (3 years: 53.1% vs. 46.9%; HR 0.83; 95% CI: 0.70–0.99; p = .04) in de novo AML owing to a reduced relapse risk, with a trend toward longer OS in the Mylotarg arm, but was not statistically significant (3 years: 69.4% vs. 65.4%; HR 0.91; 95% CI: 0.74–1.13; p = .39). However, it was also found that increased toxicity (postremission toxic mortality) was observed in patients with low‐risk AML, which was attributed to the prolonged neutropenia that occurred after receiving gemtuzumab ozogamicin during intensification Course 2.

Clinical Safety

In the combination ALFA‐0701 study, the most frequent (≥1%) adverse reactions that led to permanent discontinuation in the combination therapy study were thrombocytopenia, VOD, hemorrhage, and infection. However, in the IPD meta‐analysis, the 60‐day mortality rate was similar between the two groups, and there was no interaction between Mylotarg and the combination chemotherapy.

In the combination therapy study (n = 131), VOD was reported in six (4.6%) patients during or following treatment, and two (1.5%) of these reactions were fatal. Five (3.8%) of these VOD reactions occurred within 28 days of any dose of gemtuzumab ozogamicin. One VOD event occurred more than 28 days after last dose of gemtuzumab ozogamicin. One of these events occurred a few days after having started HSCT conditioning regimen. This toxicity limited the use of the drug, especially before allotransplant.

In the ALFA‐0701 study, thrombocytopenia with platelet counts <50,000/mm3 persisting 45 days after the start of therapy for responding patients (CR and incomplete platelet recovery) occurred in 22 (20.4%) patients. The number of patients with persistent thrombocytopenia remained similar across treatment arms during first and second induction. However, a higher proportion of GO patients had prolonged (>59 days) thrombocytopenia (38.1% GO vs. 22.9% No GO) during Intensification II (AAML0531).

Benefit‐Risk Assessment

Several new targeted therapies are studied in AML with meaningful improvement and challenge the role of GO.

The current standard of care for the treatment of de novo AML is based on intensive 3 + 7 (DNR/AraC) induction chemotherapy; in case of remission, this is usually followed by two to four courses of consolidation therapy or transplant in patients eligible based on the individual risk category.

Few improvements have been achieved in the treatment of this disease in the last decades, and survival expectance remains poor. Despite some improvement illustrated by the results obtained in MRC trials in 1970–2009, however it still highlighted the ongoing unmet medical need [22].

Patients’ related factors such as increasing age are an adverse prognostic factor, whereas genetic abnormality classification has also been used to determine the outcome [23]. Any treatment benefit in the de novo setting would be reflected in an increase of patients achieving sustainable first remission rates, allowing more eligible patients proceeding to transplant as per individual risk profile, ultimately translating into improvement in OS. However, any prolongation of remission could be considered of clinical benefit, particularly when looking at first‐line treatment and the benefit patients might gain by having a prolonged time off further therapy in a disease in which relapse usually occurs early. The primary endpoint of EFS, evaluated in the ALFA‐0701 trial, is relevant in this clinical context, and it is agreed that EFS is a clinically meaningful endpoint. An improvement in median EFS of around 6 months and a risk reduction to experience an event of around 30% is of clear clinical relevance. The effect on overall survival was less clear, although, also based on supportive evidence from an IPD meta‐analysis, a small favorable effect seems likely. In any case, a detrimental effect in terms of OS in the whole population can be ruled out.

Study ALFA‐0701 has provided convincing evidence of clinical efficacy of gemtuzumab ozogamicin in combination with daunorubicin + cytarabine compared with daunorubicin + cytarabine alone in terms of the primary endpoint EFS, for induction and consolidation therapy in patients with AML. The primary efficacy analysis (investigator's review—data cutoff August 2011) showed a difference in median EFS of 7.8 months (HR 0.562; 95% CI: 0.415–0.762; two‐sided p = .0002), consistent when stratified by National Comprehensive Cancer Network or ELN classification. The most conservative sensitivity analysis performed (blinded independent review; data set April 2013) confirmed the primary analysis, with an EFS derived from investigator assessment being significantly longer for patients in the GO arm (median 17.3 months; 95% CI: 13.4–30.0) than in the control arm (median 9.5 months; 95% CI: 8.1–12.0; HR 0.56; 95% CI: 0.42–0.76; two‐sided p = .0002). Regarding the secondary endpoint, RFS confirmed a statistically significant difference in favor of the GO arm (28.0 months; 95% CI: 16.3 to not estimable in the GO arm and 11.4 months; 95% CI: 10.0–14.4 in the control arm, corresponding to a 47% reduction in the risk of an event for patients in the GO arm compared with those in the control arm) [19].

Efficacy is supported by the primary endpoint OS of the IPD meta‐analysis. The addition of gemtuzumab ozogamicin significantly reduced the risk of relapse (OR 0.81; 95% CI: 0.73–0.90; p = .0001), and improved overall survival at 5 years (OR 0.90; 95% CI: 0.82–0.98; p = .01). The intended indication was for the treatment of AML in combination with DNR and AraC in adult patients with previously untreated de novo AML. The absolute survival benefit was especially apparent in patients with favorable cytogenetic characteristics (20.7%; OR 0.47; 95% CI: 0.31–0.73; p = .0006) but was also seen in those with intermediate characteristics (5.7%; OR 0.84; 95% CI: 0.75–0.95; p = .005). Patients with adverse cytogenetic characteristics did not benefit (2.2%; OR 0.99; 95% CI: 0.83–1.18; p = .9). Doses of 3 mg/m2 were associated with fewer early deaths than doses of 6 mg/m2, with equal efficacy [16].

Efficacy for the intended indication for patients less than 50 years of age is based on full extrapolation, as the pivotal ALFA‐0701 trial only recruited patients aged 50–70 years. It is agreed that Mylotarg is considered to have a positive benefit/risk in all patients with newly diagnosed CD33‐positive AML aged 18 and above. This is based on disease similarity, acknowledging that any associated (known or unknown) biological differences due to age do not alter the assumed clinically meaningful benefits for this patient group. However, it is difficult to acknowledge why one would consider a treatment benefit in a patient with AML treated with Mylotarg in combination with 3 + 7 induction chemotherapy at the age of 18 years established, but not one at the age of 17 years. The CHMP acknowledged that there are differences in the frequency of AML subtypes and common molecular aberrations between adults and children in general. However, the literature data and efficacy data from the meta‐analyses were considered supportive evidence to bridge efficacy assumptions to patients less than 50 years of age (Table 1). The Teenage and Young Adult (TYA) subgroup of patients (15–29 years of age) showed efficacy trends similar to the overall population, if not slightly better. Regarding safety, it is noted that the 30‐ and 60‐day mortality for TYA patients (15–29 years of age) in the Mylotarg arm was none. Despite the limited number, all of this is reassuring, as it confirms what is already known—younger TYA patients tend to tolerate intensive chemotherapy better than older patients.

Table 1. Number of patients per age included in clinical studies.

Abbreviations: MRC, Medical Research Council; NCRI, National Cancer Research Institute.

Additionally, it must be emphasized that acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) that is treated with another approach—retinoic acid and now arsenic derivatives—was not included in the pivotal trial, which has been reflected in the indication.

There are additional established independent risk factors, such as age, which is a poor risk factor in adults, associated with higher rates of poor‐risk cytogenetics. Subgroup analyses of EFS indicated a more encouraging treatment effect with the Mylotarg combination in patients with favorable/intermediate‐risk cytogenetics. Reflecting on the differences observed for the different risk groups, it can be hypothesized that patients with adverse cytogenetics who receive fractionated dose Mylotarg seem to exhibit less deep responses, translating into shorter, not statistically significant periods of remission. This led to the conclusion that the hard‐to‐treat poor cytogenetic patient group is less susceptible to Mylotarg‐based induction chemotherapy.

The efficacy results from the pivotal trial supported by the IPD meta‐analysis showed that Mylotarg added to induction chemotherapy improved EFS through prolongation of remission following initial chemotherapy, rather than increasing the number of patients who achieve complete remission, as confirmed by the absence of a statistically significant difference in the overall response rate.

The safety concerns associated with GO also need to be emphasized. The number of patients experiencing treatment‐emergent adverse events (TEAEs) leading to permanent discontinuation of study drug in the ALFA0701 study was higher in the GO arm (31.3%) than in the control arm (7.3%), mainly due to thrombocytopenia and VOD.

The 30‐day mortality rate was numerically higher in the GO arm (3.8% vs. 2.2%) but similar across arms at 60 days (GO 5.3% vs. control 5.1%). The increased risk for treatment‐related mortality in the GO arm was driven by increased deaths due to hemorrhage (3.1% vs. 0%) and liver toxicity (VOD; 1.5% vs. 0%).

The incidence rate of antidrug antibody (ADA) development after gemtuzumab ozogamicin treatment was <1% across the four clinical studies with ADA data. Definitive conclusions cannot be drawn between the presence of antibodies and potential impact on efficacy and safety because of the limited number of patients with positive ADAs. Mylotarg will be administered to patients who are going to be immunosuppressed over the course of the treatment; thus, minimal adverse events due to immune response are expected.

Outcome

Based on the review of the quality, safety, and efficacy data, the CHMP considered by consensus that the risk‐benefit balance of Mylotarg is favorable in the following indication:

Mylotarg is indicated for combination therapy with DNR and AraC for the treatment of patients aged 15 years and above with previously untreated, de novo CD33‐positive AML, except APL.

Acknowledgments

The scientific assessment summarized in this report is based on important contributions from the rapporteur and co‐rapporteur assessment teams, CHMP members, and additional experts following the application for a marketing authorization from the company. This publication is a summary of the European Public Assessment Report (EPAR), the summary of product characteristics, and other product information. The EPAR is published on the European Medicines Agency (EMA) website (www.ema.europa.eu). For the most current information on this marketing authorization, please refer to the EMA website. The authors of this article remain solely responsible for the opinions expressed in this publication.

Author Contributions

Conception/design: Francesco Pignatti

Provision of study material or patients: Sinan B. Sarac

Collection and/or assembly of data: Helen‐Marie Dunmore, Dominik Karres, Justin L. Hay, Tomas Salmonsson, Christian Gisselbrecht, Sinan B. Sarac, Ole W. Bjerrum, Doris Hovgaard, Yolanda Barbachano, Nithyanandan Nagercoil, Francesco Pignatti

Data analysis and interpretation: Helen‐Marie Dunmore, Dominik Karres, Justin L. Hay, Tomas Salmonsson, Christian Gisselbrecht, Sinan B. Sarac, Ole W. Bjerrum, Doris Hovgaard, Yolanda Barbachano, Nithyanandan Nagercoil, Francesco Pignatti

Manuscript writing: Helen‐Marie Dunmore, Dominik Karres, Justin L. Hay, Tomas Salmonsson, Christian Gisselbrecht, Sinan B. Sarac, Ole W. Bjerrum, Doris Hovgaard, Yolanda Barbachano, Nithyanandan Nagercoil, Francesco Pignatti

Final approval of manuscript: Helen‐Marie Dunmore, Dominik Karres, Justin L. Hay, Tomas Salmonsson, Christian Gisselbrecht, Sinan B. Sarac, Ole W. Bjerrum, Doris Hovgaard, Yolanda Barbachano, Nithyanandan Nagercoil, Francesco Pignatti

Disclosures

The authors indicated no financial relationships.

References

- 1.Legrand O, Perrot JY, Baudard M et al. The immunophenotype of 177 adults with acute myeloid leukemia: Proposal of a prognostic score. Blood 2000;96:870–877. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Comprehensive Cancer Network . NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines): Acute myeloid leukemia. Fort Washington, PA: National Comprehensive Cancer Network; Version 2. February 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Döhner H, Weisdorf DJ, Bloomfield CD. Acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med 2015;373:1136–1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Verma D, Kantarjian H, Faderl S et al. Late relapses in acute myeloid leukemia: Analysis of characteristics and outcome. Leuk Lymphoma 2010;51:778–782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bornhäuser M, Illmer T, Schaich M et al. Improved outcome after stem‐cell transplantation in FLT3/ITD‐positive AML. Blood 2007;109:2264–2265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burnett AK, Wheatley K, Goldstone AH et al. The value of allogeneic bone marrow transplant in patients with acute myeloid leukaemia at differing risk of relapse: Results of the UKMRC AML 10 trial. Br J Haematol 2002;118:385–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McSweeney PA, Niederwieser D, Shizuru JA et al. Hematopoietic cell transplantation in older patients with hematologic malignancies: Replacing high‐dose cytotoxic therapy with graft‐versus‐tumor effects. Blood 2001;97:3390–3400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hinman LM, Hamann PR, Wallace R et al. Preparation and characterization of monoclonal antibody conjugates of the calicheamicins: A novel and potent family of antitumor antibiotics. Cancer Res 1993;53:3336–3342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Linenberger ML. CD33‐directed therapy with gemtuzumab ozogamicin in acute myeloid leukemia: Progress in understanding cytotoxicity and potential mechanisms of drug resistance. Leukemia 2005;19:176–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Larson RA, Sievers EL, Stadtmauer EA et al. Final report of the efficacy and safety of gemtuzumab ozogamicin (Mylotarg) in patients with CD33‐positive acute myeloid leukemia in first recurrence. Cancer 2005;104:1442–1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Petersdorf S, Kopecky K, Stuart RK et al. Preliminary results of Southwest Oncology Group study S0106: An international intergroup phase 3 randomized trial comparing the addition of gemtuzumab ozogamicin to standard induction therapy versus standard induction therapy followed by a second randomization to post‐consolidation gemtuzumab ozogamicin versus no additional therapy for previously untreated acute myeloid leukemia. Blood 2009;114:790. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burnett A, Cavenagh J, Russell N et al. Defining the dose of gemtuzumab ozogamicin in combination with induction chemotherapy in acute myeloid leukemia: A comparison of 3 mg/m2 with 6 mg/m2 in the NCRI AML17 Trial. Haematologica 2016;101:724–731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Der Velden VH, te Marvelde JG, Hoogeveen PG et al. Targeting of the CD33‐calicheamicin immunoconjugate Mylotarg (CMA‐676) in acute myeloid leukemia: in vivo and in vitro saturation and internalization by leukemic and normal myeloid cells. Blood 2001;97:3197–3204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Castaigne S, Pautas C, Terré C et al. Effect of gemtuzumab ozogamicin on survival of adult patients with de‐novo acute myeloid leukaemia (ALFA‐0701): A randomised, open‐label, phase 3 study. Lancet 2012;379:1508–1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang CC, Yan Z, Pascual B et al. Gemtuzumab ozogamicin (GO) inclusion to induction chemotherapy eliminates leukemic initiating cells and significantly improves survival in mouse models of acute myeloid leukemia. Neoplasia 2018;20:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hills RK, Castaigne S, Appelbaum FR et al. The addition of gemtuzumab ozogamicin to induction chemotherapy in acute myeloid leukaemia: An individual patient data meta‐analysis of randomised trials in adults. Lancet Oncol 2014;15:986–996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taksin AL, Legrand O, Raffoux E et al. High efficacy and safety profile of fractionated doses of Mylotarg as induction therapy in patients with relapsed acute myeloblastic leukemia: A prospective study of the alfa group. Leukemia 2007;21:66–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Farhat H, Reman O, Raffoux E et al. Fractionated doses of gemtuzumab ozogamicin with escalated doses of daunorubicin and cytarabine as first acute myeloid leukemia salvage in patients aged 50‐70‐year old: A phase 1/2 study of the acute leukemia French association. Am J Hematol 2012;87:62–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lambert J, Pautas C, Terré C et al. Gemtuzumab ozogamicin for de novo acute myeloid leukemia: Final efficacy and safety updates from the open‐label, phase 3 ALFA‐0701 trial. Haematologica 2018;104:113–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Castaigne S, Pautas C, Terre C et al. Fractionated doses of gemtuzumab ozogamicin (GO) combined to standard chemotherapy (CT) improve event‐free and overall survival in newly‐diagnosed de novo AML patients aged 50–70 years old: A prospective randomized phase 3 trial from the Acute Leukemia French Association (ALFA). Blood 2011;118:6a.21737608 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gamis AS, Alonzo TA, Meshinchi S et al. Gemtuzumab ozogamicin in children and adolescents with de novo acute myeloid leukemia improves event‐free survival by reducing relapse risk: Results from the randomized phase III Children's Oncology Group trial AAML0531. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:3021–3032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burnett AK. Treatment of acute myeloid leukemia: Are we making progress? Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program 2012;2012:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Döhner H, Estey E, Grimwade D et al. Diagnosis and management of AML in adults: 2017 ELN recommendations from an international expert panel. Blood 2017;129:424–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]