The health care system is broken and it has been broken for a long time. There is an emerging trend for multidisciplinary teams to deliver primary health care (PHC) [1, 2]. This novel approach PHC is proving to be advantageous. Respiratory Therapists (RTs) are working collaboratively within multidisciplinary teams, infusing the health care system with focusing on disease prevention and health promotion versus the dated practice of waiting until the client is at their worst health to intervene. People deserve to live their best life with their illness, and RTs can contribute to making that possible.

Significant changes are needed to improve our broken health care system, specifically it needs to be sensitive and nimble enough to treat clients at the individual level, while also being informed by the social determinants of health. The determinants of health are conditions shaped by the distribution of resources that are experienced by people and influence health outcomes [3]. When this happens, clinicians can respond in a client-centred way that meets specific and overall health needs. Early diagnosis, treatment, and education/support are the cornerstones of effective PHC [4]. Building an equitable partnership between the client and the PHC provider is vital to client-centered and client-driven health care relationships [5–7]. We believe these equitable clinician–client relationships empower and support clients in taking greater control over their own health, and that this approach is vital for improving long-term management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). We also believe this proactive, client-centred approach can be scaled up beyond the treatment of COPD to include improved management of other chronic diseases that are frequently lost in the shuffle, of episodic “sick care”.

The role of RTs is evolving and growing. Historically RTs’ place to shine has been in hospital and notably in critical care. Although this is still absolutely true, and remains relevant, a broadening scope within the profession is emerging. Standing on the shoulders of home care and RTs with the Extra Mural Program (the hospital without walls that provides health care in the home), we are seeing greater expansion of the RT role into the community. RTs are in asthma and COPD clinics, community-based pulmonary rehab, and community health centres. More and more RTs are using their knowledge and expertise in the community with a focus on treatment and support of people living with COPD.

One example of this new and expanded role is an innovative pilot program happening at a health centre in Fredericton, New Brunswick. An upstream approach is being explored for early diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of COPD. Clients of the Downtown Fredericton Community Health Centre who meet specific criteria are offered early access to targeted screening for COPD (spirometry). The criteria include being older than 30 years of age, having a history of smoking or environmental exposure to toxins, or chronic bronchitis. Once a client is found to have COPD, they receive wraparound support from the multidisciplinary team (RT, Registered Nurse (RN), Social Worker, Dietitian, Occupational Therapist, Nurse Practitioner, and Physician) to treat their COPD. This approach recognizes that chronic disease management is most effective when the social determinants of health are concurrently addressed, and the client’s other chronic conditions are considered. The clinical focus broadens beyond just a set of lungs. The foundations of this upstream, multidisciplinary driven approach to COPD care are prevention, health promotion, education, and support within the community. This contrasts “usual” COPD care that often only diagnoses COPD after the first admission to hospital and rarely provides self-management education or psycho-social support.

In this pilot program, RTs and RNs work together to assess, treat, and support people suspected of having and/or living with COPD. The RT and RN review health history and risk factors for COPD, medications and ability to afford the medications, and immunization status as a place to begin the health care relationship. The team approach respects the reality that each and every client’s health depends on more than just their breathing. Our approach also includes a peer-support initiative that offers clients with more experience living with COPD an opportunity to help guide people who are newly diagnosed, thereby capitalizing on client engagement. Peer to peer support and learning reduces the client’s feelings of isolation and fear, as they share their struggles and successes with each other. Confidence builds as the group develops a connection while learning about their chronic illness and how to self-manage. RTs are integral in making it possible to offer pulmonary rehabilitation to more people in the community than has ever been possible and still has room for impressive growth. A client, who is a real success story, explained the benefits he realized when seeing the RT and RN together.

“During my appointments with the RT and the nurse they looked at my whole health. They talked to me about my diabetes and answered questions I had about that too. They treated me like I was a whole person and not just my lungs. That support helped me succeed in making changes to my life that improved my whole health. It moved me from a place of feeling scared and powerless with the diagnosis of COPD and symptoms that kept me from doing the things I loved.” (Client)

Knowledge is power; the ”Know Your Status” [8] campaign that focuses on Hepatitis C and HIV are based on the idea that if you know that you have a certain disease/condition then you can engage in treatment and lifestyle changes that mitigate any damage and may in fact increase ability to maintain or improve a certain level of health. We believe that this also applies to COPD. We believe that the more people who know their lungs are being damaged as a result of undiagnosed COPD the greater the number of people who will be able to engage in activities, education, and treatments that will slow or halt the progression of the disease. Our client experience advisor is just one example of someone who when provided with the knowledge was able to make impressive changes to his life, turn his health status around, is willing to use that experience to support other newly diagnosed with COPD, and inform our practice. We need to stop the burden of disease on both the person and the health care system.

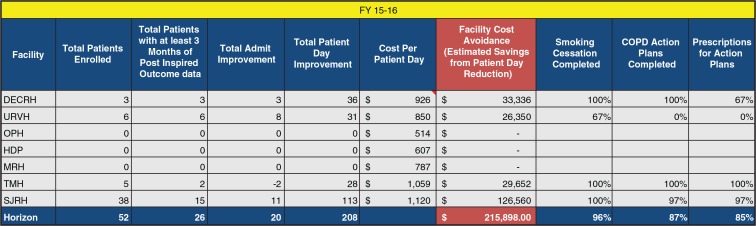

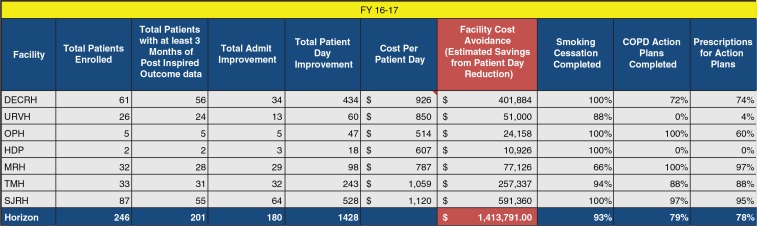

Programs that provide opportunity for intentional health care partnerships need to be funded with sustained long-term funding in a way that demonstrates a clear understanding and acceptance of their value and the importance of preventative/health promotion programs. We know that working in silos hampers our institutional effort to provide comprehensive health and wellness care [9, 10]. Communication and smoother transitions in care between acute care settings and community are fundamental to the overall wellbeing of the client [11]. We need to realize that every client that we interact with lives in the community and enters the hospital when acutely ill, and more importantly, returns to the community when able. If PHC is working well and is sufficiently funded and staffed, clients are supported in remaining at home and in the community longer. Robust PHC will also reduce emergency department utilization and hospital admissions, which is the ultimate goal of both the client and healthcare team (Figures 1 and 2) [12]. Soft savings of 1.6 million dollars was realized by our health network because of reduced hospital usage.

FIGURE 1. INSPIRED* outcome data fiscal year 2015–2016 [12].

*INSPIRED (Implementing a Novel and Supportive Program of Individualized care for patients and families living with REspiratory Disease) is a program focused on improving transitions from hospital to home “by enhancing patient confidence to manage their illness more effectively in their homes and communities.” [11]

Note: DECRH, Dr Everett Chalmers Regional Hospital; URVH, Upper River Valley Hospital; OPH, Oromocto Public Hospital; HDP, Hotel Dieux Perth; MRH, Miramichi Regional Hospital; TMH, The Moncton Hospital; SJRH, Saint John Regional Hospital.

FIGURE 2. INSPIRED* outcome data fiscal year 2016–2017 [12].

*INSPIRED (Implementing a Novel and Supportive Program of Individualized care for patients and families living with REspiratory Disease) is a program focused on improving transitions from hospital to home “by enhancing patient confidence to manage their illness more effectively in their homes and communities.” [11]

Note: DECRH, Dr Everett Chalmers Regional Hospital; URVH, Upper River Valley Hospital; OPH, Oromocto Public Hospital; HDP, Hotel Dieux Perth; MRH, Miramichi Regional Hospital; TMH, The Moncton Hospital; SJRH, Saint John Regional Hospital.

Working in the community has demonstrated that we can provide care that has improved accessibility by offering appointments at various times of the day and closer to home. We have the freedom to think outside the box to deliver the best health care that suits the needs of the client. It might mean accessing services that are not traditionally the responsibility of the RTs, for example initiating Meals on Wheels for the client with COPD who is too short of breath to prepare their meals or broaching the topic of advance care planning with the client and their family. The possibility for delivery of optimal care for the client can be realized if we participate in multidisciplinary caseload management with other therapeutic professions such as social workers, dietitians, physio therapists, and/or occupational therapists.

Additionally, being able to offer appointments and education sessions that include the client and their family/support person acknowledges the importance of these people to the client in their experiences with health, illness, and continued wellbeing. Working in a multidisciplinary team we can enhance the clients’ contributions to the development of personal health goals and care plans.

Looking back to when I was diagnosed, I was in a place of worry and fear about my health. Seeing the surgeon and respirologist did not help me feel better about my health. They gave me the diagnosis without any concrete details or information on how I could make my situation better. Since being seen by my nurse and RT, I feel completely different. I feel well equipped to manage my own health. I know I have lung disease and diabetes, and I know how to take care of them. (Client)

Kitts left a hospital-based position that was extremely fulfilling after becoming frustrated by hearing clients tell the recurring stories and recognizing the same gaps in knowledge and support. What went through Kitts’ mind was a growing understanding that if these clients had access to community-based education and support for their chronic illness even two weeks prior they may not have gotten so sick and had to be admitted to hospital today! We have a deep love and respect for hospitals and their staff; they serve an important role in providing care when communit- based care is no longer sufficient. But we need to understand that hospital and community are two hands that need to come together to care for clients. Everyone can benefit when hospital and community cooperate and collaborate in the provision of PHC that is focused on the needs of the client, putting the client at the center of the health care relationship.

What are the clear and concrete steps that we must engage in to achieve this? While we put a great deal of effort into building the client–provider relationship that is so important, the relationship between disciplines needs greater awareness of, and commitment to, the importance of working together. RTs working in the community can demonstrate what RTs can bring to the health care relationship by stepping outside the box and engaging with practitioners from other disciplines. This movement forward requires intentional curriculum changes within health care professions focusing on improved understanding of multidisciplinary responsibilities and functioning that reflect the role of the RT within the multidisciplinary team in providing excellent PHC [6]. System changes that support the multidisciplinary team approach in the community are also needed to equip RTs and other disciplines to work effectively in PHC, multidisciplinary teams.

REFERENCES

- 1.MacDermid E, Houton G, MacDonald M, et al. Improving patient survival with the colorectal cancer multi-disciplinary team. Colorectal Dis. 2008;11:291–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2008.01580.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim MM, Barnato AE, Angus DC, et al. The effect of multidisciplinary care teams on intensive care unit mortality. Arch Intern Med. 170(4):369–76. doi: 10.1001/arch-internmed.2009.521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. About social determinants of health [Internet]. Geneva: WHO. Available at: www.who.int/social_determinants/sdh_definition/en/ [Accessed 15 November 2018]. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Canadian Nurses Association. Effective healthcare equals PHC. Ottawa: CNA. Available at: https://www.cna-aiic.ca/~/media/cna/page-content/pdf-fr/fs17_effective_health_care_equals_primary_health_care_nov_2002_e.pdf?la=en [Accessed 15 November 2018]. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Housden L, Browne AJ, Wong S, Dawes M. Attending to power differentials: How NP-led group medical visits can influence the management of chronic conditions. Health Expect. 2017;20:862–70. doi: 10.1111/hex.12525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kirsch SR, Schaub K, Aron DC. Shared medical appointments: A political venue for education in interprofessional care. Qual Manag Health Care. 2009;18(3):217–24. doi: 10.1097/QMH.0b013e3181aea27d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson B, Abraham M, Shelton TL. Patient- and family-centered care: Partnerships for quality and safety. NC Med. 2009;70(2):125–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.CATIE. Know your status. Big River, Sask; 2016. Available at: https://www.catie.ca/en/printpdf/pc/elements/know-your-status

- 9.Johnson R, Grove A, Clarke A. It’s hard to play ball: A qualitative study of knowledge exchange and silo effects in public health,. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12913-017-2770-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lau JY-C, Wong EL-Y, Chung RY, et al. Collaborate across silos: Perceived barriers to integration of care for the elderly from the perspectives of service providers. Int J Health Plan Manag. 2018;33:e768–80. doi: 10.1002/hpm.2534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rocker GM, Verma JY. ‘INSPIRED’ COPD outreach programTM: Doing the right things right. Clin Invest Med. 2014;37(5);E311–19. doi: 10.25011/cim.v37i5.22011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Horizon Health Network Data from Discharge Abstract Database (DAD). Facility cost avoidance (estimated savings from patient-day reduction). INSPIRED outcome data fiscal year 2015–2017, Horizon Health Network, Miramichi, NB. [Google Scholar]