Abstract

In 2012, the provincial cancer agency in Alberta initiated a provincial quality improvement (QI) project to develop, implement, and evaluate a provincial Cancer Patient Navigation (CPN) program spanning 15 sites across over 600,000 square kilometres. This project was selected for two years of funding (April 2012–March 2014) by the Alberta Cancer Foundation (ACF) through an Enhanced Care Grant process (ACF, 2015). A series of articles has been created to capture the essence of this quality improvement (QI) project, the processes that were undertaken, the standards developed, the education framework that guided the orientation of new navigator staff, and the outcomes that were measured. The first article in this series focused on establishing the knowledge base that guided the development of this provincial navigation program and described the methodology undertaken to implement the program across 15 rural and isolated urban cancer care delivery sites. The second article delved into the education framework that was developed to guide the competency development and orientation process for the registered nurses who were hired into cancer patient navigator roles and how this framework evolved to support navigators from novices to experts. This third and final article explores the evaluation approach used and outcomes achieved through this QI project, culminating with a discussion section, which highlights key learnings, and subsequent steps that have been taken to broaden the scope and impact of the provincial navigation program.

Developing, implementing, and evaluating a provincial navigation program spanning 15 sites across more than 600,000 square kilometres is no small feat, but that is what was undertaken within Alberta’s provincial cancer agency. Work on this provincial quality improvement (QI) project began in April 2012, and is ongoing. However, the grant-funded portion of the work occurred from 2012–2014 and is the focus of this series of articles. Capturing the essence of this program work, the processes that were undertaken, the standards developed, the education framework that guided the orientation of new navigator staff, and the outcomes that were measured in the initial two-year grant funded project, has required the development of a series of articles.

The intention of this series of articles is to share the learnings gleaned from the multiple stages of this project with others who may be considering the implementation of a similar program. As well, these articles will contribute to the knowledge base regarding the impact that a cancer patient navigator program such as this can have on the patient experience, team functioning, care coordination, and health system utilization. In the first article, the focus was on establishing the knowledge base that guided the development of the navigation program and describing the methodology undertaken to implement the program (Anderson, Champ, Vimy, DeIure, & Watson, 2016). The second article delved into the education framework established to guide the competency development and orientation for registered nurses who were hired into cancer patient navigator roles and how this framework evolved to support navigators from novices to experts (Watson, Anderson, Champ, Vimy, & DeIure, 2016). This third and final article will explore the evaluation data and outcomes that were achieved through this QI project. This article also includes key learnings and subsequent steps that have been taken to broaden the scope and impact of the provincial navigation program.

BACKGROUND

Cancer patient navigation (CPN) can be defined as a “proactive, intentional process of collaborating with a person and his or her family to provide guidance as they negotiate the maze of treatments, services and potential barriers throughout the cancer journey” (Canadian Partnership Against Cancer [CPAC], 2012, p. 5). Enhancing navigation supports has been identified as a key driver to improving the experiences of cancer patients while also improving the efficiency of the health care system (Cook et al., 2013). As such, navigation is not an end by itself, but rather navigation supports must be integrated as a core component of quality services and supports across the health system (Alberta Health Services [AHS], 2011). In alignment with the provincial goal of creating a comprehensive and coordinated cancer care system in Alberta (Alberta Health [AH], 2013), and through the generous support of the Alberta Cancer Foundation (ACF), funding was secured in 2012 to implement a provincial CPN program in Alberta.

The Alberta CPN program revolved around the introduction of the Cancer Patient Navigator (CPN) role into the 15 isolated urban and rural ambulatory care settings in Alberta over a two-year period. Role implementation, professional development, and evaluation of outcomes were provided by a provincial navigation coordination team. The implementation of this program was a direct effort to improve rural Albertans’ access to navigation supports, as well as improve system efficiency. The Alberta program implemented a professional navigation model (CPAC, 2012) with specially trained registered nurses providing a variety of clinical supports and services including psychosocial interventions, coordination of care, health education, case management, and facilitation of communication between health systems and the patient (Pedersen & Hack, 2010; Wells et al., 2008).

Several guiding principles influenced the evolution of the Alberta CPN program. First, the CPN should be available to support a cancer patient and/or their family as a single point of contact at any point throughout their cancer journey. Secondly, the CPN role needed to be integrated into the cancer care interdisciplinary team to promote effective care coordination. Thirdly, the CPN served as a bridge between health systems and, as such, was responsible to develop and nurture local relationships with primary care teams, community agencies, and other care providers who provided supportive care within their community. Based on these guiding principles, the following goals for this program were set:

Improving the patient and family’s experience of seamless care across their care trajectory.

Enhancing integration with primary care.

Improved access for rural patients to psychological, physical, and supportive care services.

Contributing to system efficiency.

Developing a strong cancer workforce to meet the needs of cancer patients and their families in Alberta.

PROJECT METHODOLOGY

This implementation project was designed as a continuous quality improvement (QI) project. The core goal was to integrate the cancer patient navigator role into the existing clinical environment at each setting and evaluate its impact. The implementation guide for CPN developed by the CPAC (2012) was utilized as a guiding document, as it is well established that successful QI requires a comprehensive and effective change management strategy (Langley, Moen, Nolan, Norman, & Provost, 2009). Fillion et al.’s (2012) Professional Navigation Framework was also used as a guiding document.

The implementation strategy included several key elements including: a current state review, provincial program coordination and standards, co-design of the CPN role with cancer care operational leaders, development and utilization of a standardized training and coaching program, identification of barriers in each setting with associated strategies to manage them, the development of program metrics, and evaluation of outcomes. The approach for optimizing the navigator role, once implemented, included routine small-scale, site specific Plan, Study, Do, Act (PSDA) cycles as per the QI methodology (Langley et al., 2009). This project complied with the Helsinki Declaration (World Medical Association, 2008) and the Alberta Research Ethics Community Consensus Initiative (ARECCI) ethics guidelines for QI and evaluation (ARECCI, 2012). A project screen established by ARECCI identified this project as within the scope of QI and waived the need for a full Research Ethics Board review. No harm was anticipated or actually reported in relation to this project.

PROGRAM EVALUATION

The purpose of this QI evaluation was to collect feedback from a variety of sources through different means to understand the impact of the CPN program on three key outcomes including: (a) the impact of CPN care on the patient and family experience, (b) understanding the experience of being a CPN, and (c) the impact of the CPN role on the health care system and collaboration among the interdisciplinary team. How the programmatic approach to implementing a navigation program impacted outcomes, and what improvements could further enhance the program’s capacity to influence the three key outcomes, were also areas of inquiry within the evaluation process; these aspects were reported in Part One in this series of articles (Anderson, Champ, Vimy, DeIure & Watson, 2016) and so are not included in this article.

DATA COLLECTION

As there were several areas of impact anticipated, a multiple methods approach to data collection was utilized. Table 1 presents the variety of ways data were collected. Patient survey data were the only data collected pre- and post-CPN implementation, as it was gathered as part of the evaluation of a larger model of care redesign to enhance the person-centred nature of care delivery within Cancer Control Alberta (CCA) (Tamagawa et al., 2016; Watson, Groff, et al., 2016). The initial patient survey was administered prior to implementation of the CPN role, and the post evaluation survey occurred approximately 10 months after the CPN role was implemented at each site. All other focus groups, health professional surveys and interviews were conducted in the last six months of the grant period (Oct 2013–March 2014). Navigator workload data were collected routinely across the program implementation phase and continues to be collected.

Table 1.

Outcomes and data sources

| Outcomes | Data Source |

|---|---|

| Impact on patient and family experience |

|

| Experience of being a CPN |

|

| Impact on health system and collaboration among interdisciplinary team |

|

ANALYSIS

As the QI data were collected through a variety of mechanisms, the method for data analysis needed to be flexible enough to manage data gathered in different ways. A combination of inductive and deductive thematic analyses were utilized based on Schutz’s (1967) social phenomenology. Schutz’s theory is both interpretive and descriptive and aims to explore the subjective experience of individuals within the taken-for-granted commonsense world of daily life (Fereday & Muir-Cochrane, 2006). This methodological approach was well suited for our QI evaluation, as it positioned the evaluation in the everyday world of delivering clinical care to patients and families living with cancer. It also allowed for a balance between deductive interpretation generated by quantitative data and the program team’s familiarity with the theoretical tenets of cancer patient navigation, and inductive knowledge generation through emergence of themes from the participants’ particular input.

FINDINGS

Findings from this evaluation indicate that the introduction of the navigator role has had numerous positive effects. The findings are discussed in terms of the three key outcomes previously outlined.

Impact on Patient and Family Experience

Focus groups and surveys were utilized to better understand how the introduction and integration of the CPN impacted patient and family experiences of receiving care.

Focus groups

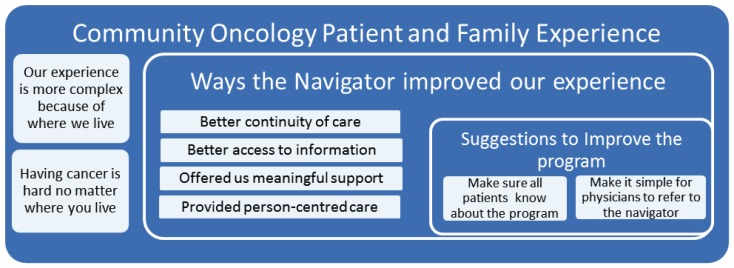

Two focus groups were conducted with patients and family members in the fall of 2013. Patients and family members who had received care from a CPN were invited to participate. A total of five patients and family members participated and provided written consent. Group discussion was audio recorded and transcribed. Thematic analysis including deductive and inductive coding was conducted (Fereday & Muir-Cochrane, 2006). Three themes emerged: (a) having cancer is hard, (b) accessing a navigator made a difference, and (c) how to improve the program (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Patient and family experience themes

Having cancer is hard

Participants expressed that their experience is rendered more complex because of where they lived in rural or isolated urban settings. These challenges included: the repeated need to travel far distances to receive care; the financial implications of paying for travel and being away from work for long periods of time to attend appointments; the emotional impacts of being away from home and not being able to fulfill usual family responsibilities in that absence; and perceiving they did not have the same level of access to resources/services/treatment options as they would have if they lived in a larger centre. One participant stated, “…every treatment you have in the big city that you can’t have here tacks on another two days of travel and at least another $1,000.”

Participants also recognized more general challenges of having cancer that were not necessarily related to their geographical location. Participants shared a sense that healthcare providers often made assumptions about what patients and families needed to know or already knew, which left them feeling that care was not always responsive to their actual needs. Participants reported that information was not clearly communicated, and that they had a hard time anticipating what was going to happen next. One participant stated, “You shouldn’t have to be the one that has to try and figure it out for yourself.” Participants also spoke of the difficulty accessing the supports they needed because it was difficult to contact the people who could answer their questions. For example, one participant stated, “You don’t have anybody to talk to. You can’t get through to them, you can’t talk to the doctor, you have to go through their admin and you can’t get past them and so who do you talk to?”

Accessing a navigator made a difference

Patients and family members shared the perspective that being cared for by the navigator had a positive impact on their experience as it improved the continuity of care, their ability to access information about cancer, and provided them with access to meaningful support. One participant stated, “… because you need that one point of contact… I had so many names and numbers and to me that was the overwhelming part. To have one name, one phone number that you can just phone and say 'help' was huge.”

Participants also spoke about the comfort of knowing they could always call the navigator, even if something went wrong in the future. One participant stated, “I didn’t have a whole lot of knowledge or information on what happened next and that’s what [the navigator] really did, she provided an idea of what the whole process would be, you know the chemo, the radiation, who I could expect to talk to and laid it all out.” Participants also shared a sense that the navigator offered a level of support that they did not think they would have received without the navigator being involved in their care; for example, “I’m just glad that the navigator is here to help us, my god if it wasn’t for this program where would I be?”

Although the participants did not use the language of person-centred care, they clearly articulated how the navigator embodied the principles of person centredness. One participant stated, “It is a great feeling to be recognized – I mean I’m not just a number, I am a person and she knows me.” Another participant spoke about how care from the navigator is individualized, and that makes the type of care they provide more meaningful.

Ways to improve the navigator program

Although participants did not voice any concerns with the program or the services provided by navigators, they did identify ways that the program could be improved. These included ensuring that all patients, no matter where they are on their cancer journey, are aware of the program and that family physicians know how to refer patients to the navigator and actively supported the connection of new cancer patients to a CPN.

Patient surveys

Patient surveys were collected as part of the larger provincial model of care evaluation (Watson, Groff, et al., 2016). As CPN roles were only implemented in CO sites, surveys from other sites were excluded from this secondary analysis. The data analyzed included 81 patient pre-surveys and 33 post-surveys from CO sites. Of the 33 patient post-surveys that were received, 28 (85%) patients indicated that they had been cared for by a cancer patient navigator. To explore the data, specific questions related to care that could potentially be influenced by the navigator role were selected, frequencies of responses for these questions were calculated, and the data were graphed to facilitate pre-post comparisons.

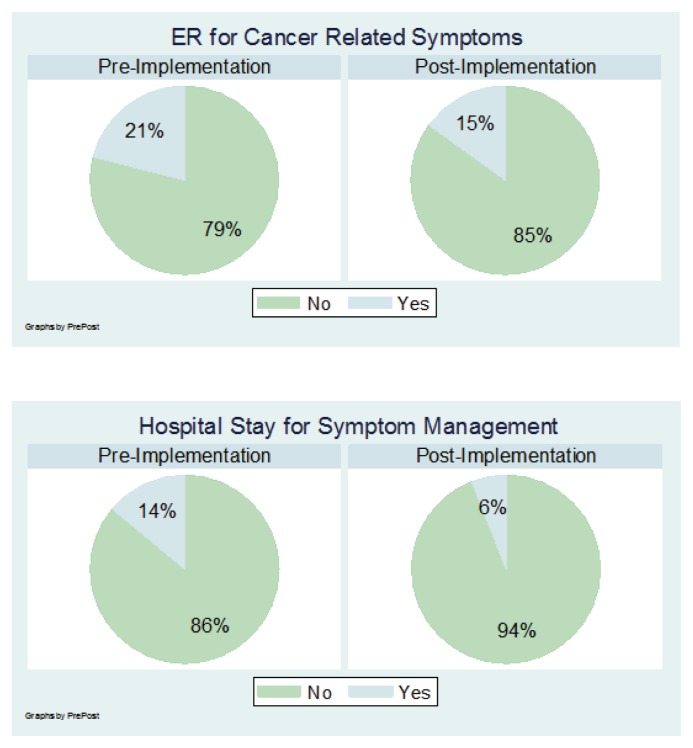

The questions regarding whether patients required an urgent visit to the ER or admission to hospital over the last 4 weeks to manage their cancer related symptoms were of particular interest to this evaluation. As shown in Figure 2, both indicators decreased after the implementation of CPN.

Figure 2.

Patient-reported utilization of emergency room and hospital stays: Pre and post navigation implementation

Additionally, when asked specifically about their experience with the cancer patient navigator, patients reported being very satisfied. Of the 28 patients who indicated they were cared for by a patient navigator, the majority (84%) contacted the navigator between one and five times. The most commonly cited ways in which the navigator provided support were: providing information on treatment and side effects (20%), providing information on local resources (16%), providing emotional support (15%), helping the patient understand their diagnosis (15%), helping to book/coordinate appointments (14%), and helping to find support to pay for drugs/supplies (10%).

Overall, this patient and family experience data suggest the introduction of the navigator role has had numerous positive effects on the patient experience including reduced hospital and emergency room visits, improved support for emotional and practical concerns, and improved care coordination. Taken together, the focus groups and survey data shed light on the impact of the CPN program on patients and families as they go through their cancer journey. Patients clearly expressed that the navigator helped achieve continuity in their care, was able to provide meaningful information, and enhanced the support they received.

Experience of Being a Cancer Patient Navigator

Evaluation of the navigator role focused on understanding the navigators’ experiences in their role and understanding the navigator role through analysis of their workload data.

CPN reflective practice survey

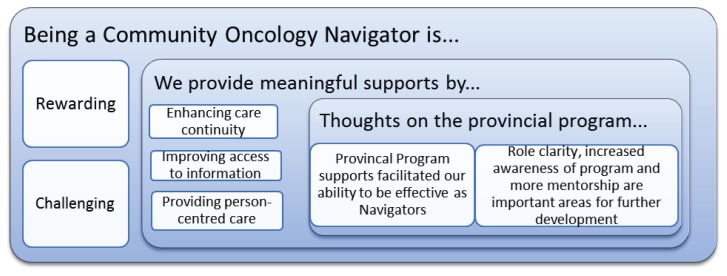

To understand the navigators’ experiences in their roles, an open ended reflective survey was circulated to all the navigators near the end of the grant period (January, 2014). All 13 active navigators at the time completed the survey, responses were compiled, and a thematic analysis was conducted. Three themes emerged from the data (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Schematic of navigator experience themes

Being a CPN is rewarding and challenging

All participants felt being a navigator was mostly rewarding. They felt appreciated by both patients and families as well as by other healthcare providers. From their perspective, being a navigator allowed them to address a broad range of patient needs more comprehensively than clinic staff or other healthcare providers. Navigators recognized they had developed deeper relationships with patients than they had been able to do previously in other nursing roles. In their navigator role, they thought they were able to make a significant difference in the experience of patients and families living with cancer. All of the navigators reported that they would be interested in continuing in the navigator role.

Participants also spoke of various challenges they experienced, with most occurring during the early stages of role implementation. One common challenge was promoting awareness and utilization of the role with community partners, especially family physicians. Participants reported this was sometimes due to lack of consistency or turnover in physicians and care providers within their communities. Defining the navigator role within the cancer clinics was another challenge identified. Participants reported having struggles with finding their place in the clinic settings and making efforts to enhance the care already provided by staff rather than duplicating it or taking over roles of other providers. Another challenge identified was using an electronic charting system. Some participants had no previous experience with electronic charting and had to learn the new skill. They also had to incorporate their electronic charting into the clinic’s method of documentation, which in many cases was still paper. This led to some confusion.

Providing meaningful supports

All navigators spoke about how their role enabled them to provide general support to patients and families. Navigators recognized how they assisted with specific needs, as well as helping patients by just being there for them or, as one navigator wrote, by “being a listening ear when people are scared and confused.” All navigators felt that they had been able to reduce patient and/or family anxiety during times of high stress and uncertainty. One navigator stated, “I love that I have the ability to reach out to patients very early on in their diagnosis, and let them know that there is somebody there for them, to listen to their fears, help them find their answers.” The navigators also valued the ability to build relationships with patients and families and let them know “there is always someone they can call or meet with to assist them with anything they are faced with.” Navigators reported there were several specific types of support that were particularly helpful to patients and families: enhancing continuity of care, improving access to information, and providing person-centred care. One navigator reported that the most important part of her job was to help the patient “know they are not just a number in the system.”

Thoughts on the provincial program

All of the navigator participants identified that the provincial program support was an essential part of the success of the CPN program. The program coordinator/educator was a valued resource in terms of providing tangible support to the navigators at an individual level as well as at a group level. Participants reported the coordinator supported them individually throughout their orientations and with struggles and issues specific to their community sites as they worked to integrate their role. As one participant described, the coordinator was beneficial in “clarification of [the] navigator role, offering direction to complex issues, problem solving, [and] identifying resources.” At the group level, the coordinator was recognized as providing important leadership around standardization across the provincial program, and providing a sense of cohesion across navigators which prevented individual navigators from feeling isolated within their communities. In addition, participants thought the coordinator role would play an important role in the next steps of designing and supporting program improvements along with creating and optimizing awareness of the program at a provincial level and across primary care.

Some suggestions about how the program could be improved included having more clarity around the navigator role in relation to other staff within the cancer clinic and increasing the awareness and utilization of the program by community partners such as primary care providers. Another suggestion was to promote supportive activities between navigators, such as having navigators spend more one-on-one time with each other during orientation or having a buddy system where navigators have a partner with whom they can rely on for support, information, and guidance.

Navigation Workload Data

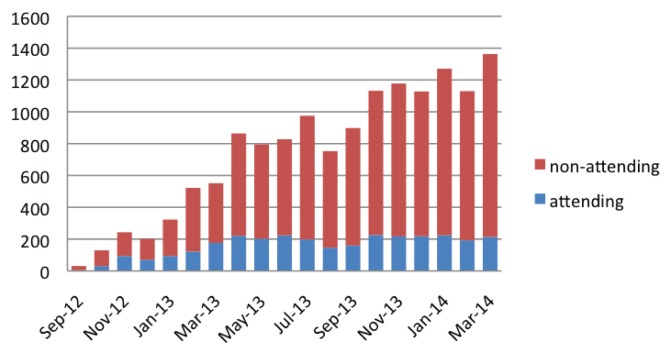

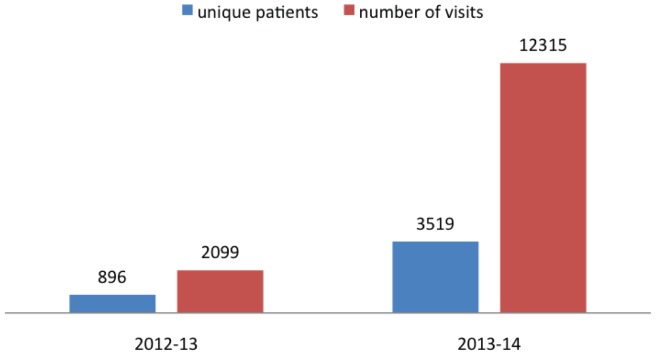

To ensure workload measures were collected in a similar manner across all sites, training and manuals included data definitions and were provided to each CPN during orientation (Watson, Anderson, Champ, Vimy & DeIure, 2016). The first CPNs who were hired through this program started their orientation in September, 2012. Since then, as CPN positions have been filled, there has been a steady increase in the number of patients and visits across sites (CPN Dashboard, 2016). Figure 4 illustrates the growth of the navigator program through aggregate monthly CPN visits (both attending and non-attending). It is important to note that the number of visits captures all interactions the navigator had, which may include multiple interactions with the same patient, or actions that were taken on behalf of the patient, such as following up on blood work, or clarifying information with primary care or the cancer care team. There was a slight decline in the number of patients seen by navigators during the summer holiday season as, when the navigator is away, there is currently no formal approach to covering the role. The second graph (Figure 5) shows the number of unique patients cared for by a CPN in comparison to the number of CPN visits recorded (either attending or non-attending).

Figure 4.

CPN visits per month during original grant period (April 2012–March 2014)

Figure 5.

CPN program volumes during grant period (April 2012–March 2014)

Impact on Health System and Collaboration among Interdisciplinary Team

To evaluate the impact the CPN role had on collaboration among the interdisciplinary team and the function of the system, open-ended surveys and targeted telephone interviews were used. Additionally, health system utilization data were obtained.

Surveys and telephone interviews

Surveys were sent to each CPN for distribution to key stakeholders (clinic staff, clinic managers, other health care providers in the hospital, and community partners). Surveys were returned to the project staff for thematic analysis. Ninety-four surveys were collected in this manner. In addition, 14 telephone interviews were conducted with a variety of key stakeholders including family physicians, community support agencies, breast health navigators, primary care providers, tumour triage nurses in the tertiary sites, social workers, and home care nurses. The survey questions were used to guide the interview discussions. Project staff conducting the interviews took notes during the conversations.

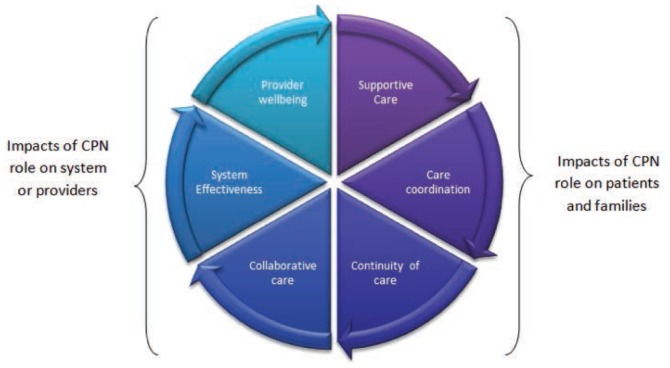

Data analysis revealed six themes under two broad concepts: how CPN care impacted patients and families, and how having a CPN as a team member impacted the functioning of the system and team (represented as two halves of the whole circle in Figure 6). Healthcare professionals who participated in this evaluation did not perceive the impact of the navigator as being in a single area; rather they recognized the impact of the navigator as multi-faceted and inter-related.

Figure 6.

Health care professionals’ (HCP) perception of the impact of the CPN role

Supportive care

Health care professionals (HCPs) reported feeling the navigator role provided important aspects of individualized supportive care to patients and families including: financial, practical, emotional, psychosocial, informational, and physically targeted care. One HCP noted the navigator treats “the whole person instead of just the symptoms.” HCPs emphasized how being able to contact the navigator at any point in their cancer experience was a key benefit for patients. One HCP noted, “For patients to know they have a navigator to go to throughout the whole process and that the navigator is there to answer any questions or deal with any concerns is very valuable even if they don’t need much actual support.” Numerous HCPs communicated a common message that, “the navigator has been a fabulous resource for information as well as support for patients and families.”

Coordination of care

HCP’s recognized the importance of the CPN role in coordination of care across the journey. Examples shared by HCPs included arranging appointments in a way to minimize travel and expense and connecting patients with services and resources as close to home as possible. HCPs appreciated and trusted that the navigator had knowledge of available resources and how to connect patients to these services. HCPs thought that connecting the patient to the navigator promoted quicker access to care, earlier interventions, and the prevention of further complications. As one HCP commented, “We are aware of patients so much sooner now because of the navigator and we can intervene before there is a crisis.”

Continuity of care

HCPs perceived CPNs as providing an added value for the patients because of having one person that patients could go to for help at any point in their cancer journey. HCPs thought knowing they had one consistent contact person who knew their story gave patients peace of mind. One HCP noted, “Navigators play an important role in creating a level of accessible support for patients over their entire journey with cancer.” HCPs also identified a professional benefit to themselves: having one person they could contact who knew the entire patient situation rather than having to piece together information from many different sources saved them time. Many HCP’s thought that the navigator role prevented patients from “falling through the cracks,” especially when patients had to travel outside their own community for different aspects of care. One HCP commented that the navigator “greatly enhanced patient care,” and there was “better organization of care, less errors and missed tests, etc., and better understanding of the care plan.”

Collaborative care

HCPs consistently articulated that the navigator promoted effective team functioning. HCPs provided examples of effective collaboration with the navigator such as, “we have met with patients together and [the navigator] can speak to any issues that I don’t have knowledge about. What I don’t know about cancer, she does.” HCPs acknowledged that navigators having specific oncology nursing knowledge such as a patient’s diagnosis, symptoms they may experience, side effect management strategies, and treatment plans, was a key benefit to effective collaboration. One HCP noted it was “nice to be able to go to a person with professional experience with cancer specific issues instead of looking something up online or talking to someone who only knows a little bit.” The navigators were viewed as a trusted resource for medical information by their colleagues. Some feedback also indicated staff felt less anxious about managing patients in distress because they knew they could refer the patient to the navigator if the patient had complex concerns beyond their ability to address within their clinical setting.

One of the areas for improvement identified by HCPs was improved role clarity. One HCP stated, “It would be helpful to have more awareness about what the navigator can help with, what they want to take on and what they don’t want to take on.” This aligns with published evidence around collaborative care which stresses the importance of all team members clearly understanding each other’s roles (Suter et al., 2009). The newness of the navigator role complicates this. Concern was also brought up regarding inconsistencies between navigator roles across the province.

System effectiveness

HCPs reported they felt the overall effectiveness of the cancer clinics improved with the implementation of the navigator role. CCA staff felt the workload on the rest of the health care team had decreased and less clinic time was being spent on non-treatment related issues. As one HCP commented, the clinic “can now focus on treatment because the navigator takes care of appointments, counselling, questions, and complex supportive care issues.” Another HCP stated, “We used to spend hours arranging appointments, connecting patients to services, and now we just pick up the phone and refer the complex ones to the navigator.” Physician feedback revealed they were “appreciative of less phone calls and interruptions during busy clinic times.” As mentioned in the collaborative care theme, many comments were made regarding HCPs appreciating the ability to go straight to the navigator for information instead of having to go to multiple sources. The time this saved for staff was highly valued by HCPs and was perceived to have improved their clinic efficiency and focus. However, HCPs articulated a general concern that there was not enough awareness of the navigator role both within their hospital setting and within the community. As one HCP noted, “Family physician referrals are minimal, the navigator has engaged physicians but it just doesn’t seem to have shifted their practice. I think there is a lot we could do to improve awareness and utilization of the role.”

Provider well-being

Having a CPN as a member of the clinical team had a positive impact on the overall well-being of HCPs. Clinic staff members described feeling less overwhelmed and felt they had lower stress levels after the navigator role was integrated into their team. This was demonstrated through comments such as, “The navigator decreases my anxiety and provides another safety net for patients,” “I feel more confident in our clinic’s ability to help the patients and family,” and “The navigator takes the burden off.” In general, HCPs reported increased confidence in their clinic’s ability to provide meaningful care for their patients and this resulted in improved job satisfaction for HPCs. HCPs were comforted by knowing that even if they could not spend a lot of time with a patient who had concerns, they could refer the patient to the navigator who could further develop a plan of care. Two statements from HCPs that emphasized this were, “knowing that there is someone who can provide patients with support and information that I cannot, makes me feel that patients are getting the best care possible” and “I feel strongly that navigators are able to enhance and complete the care that we start for patients. It makes my role more satisfying to know that patients have this kind of support.”

Although the well-being of clinic staff seemed to have improved, there was feedback from HCPs that revealed their concern over the well-being of the navigator. HCPs were concerned that the navigator had a heavy workload and they worried that this may lead to navigator burnout. As one participant noted, “The navigator can get overwhelmed with workload. We need more staff to do this role.” Another comment made was, “The navigator plays many roles and she may not be able to support all needs.” Another concern that was raised was the lack of coverage when the navigator is on vacation or away sick; during these times patients may not receive the same level of care. HCPs shared their views that the loss of the CPN role at their site would negatively impact patients and the health care system. They shared comments such as, “Patients will get lost in the system”, “it would be a terrible loss for patients; I don’t know what we would do”, “it would be devastating to lose the navigator”, “we will have some serious morale problems if something happens to the program”, One provider stated, “I would consider quitting.”

Health system utilization data

Published research suggests that introduction of additional navigation supports such as a community based CPN role may reduce emergency room (ER) visits, primary care physician (PCP) visits, the number of diagnostic tests ordered, admissions/re-admissions to hospital, as well as time intervals to access care across the cancer care trajectory (Fillion et al., 2009; Guadagnalo, Dohan & Raich, 2011; Pratt-Champman & Willis, 2013). In order to understand the impact our CPN program would have on health system utilization, a QI data request was submitted to the CCA Cancer Measurement Outcomes Research and Evaluation (CMORE) program. This baseline sample would contextualize how cancer patients in Alberta utilized the health care system (i.e., ER visits, PCP visits, and hospitalizations including length of stay) within one year of their diagnosis prior to the introduction of the CPN role. The sampling period for this baseline data was 2009–2010. The plan was to repeat this QI health system data request for any patients diagnosed in 2014, as by then the CPN program was a standard of care at all Community Oncology (CO) sites. However, at the time of writing this article, the post implementation health system utilization data were not yet available. Therefore, it will be reported in subsequent publications.

Even without the post implementation health system utilization data, there is cause for optimism regarding potential system savings from improved navigation support. Provincially, the baseline utilization data revealed that 10% of cancer patients had more than 15 cancer related PCP visits in their first year post diagnosis. Given there were 28,545 cancer patients in the two year baseline measure, simple calculations reveal that 2,854 Albertan cancer patients had more than 15 cancer related primary care visits in that time period, or 1,427 patients in one year. As each PCP visit costs the health system approximately $234 (AHS, 2011), if improved navigation supports could prevent even two PCP visits for each of these high system utilizers, over $650,000 would be saved annually. This does not include any savings that could be gained by decreasing emergency room visits, or hospital admissions/re-admissions or decreasing the number of PCP visits of cancer patients who were not in the highest utilization category of over 15 visits per year.

DISCUSSION

Findings from this evaluation demonstrated that a provincially standardized CPN program was feasible and could provide tangible, real-time improvements to the patient and family experience, system functioning, and healthcare teams’ ability to collaborate. As a result of the evaluation and outcomes achieved in the two-year grant period, the provincial CPN program was operationalized in 2014 and continues to provide care to cancer patients who live outside Edmonton and Calgary.

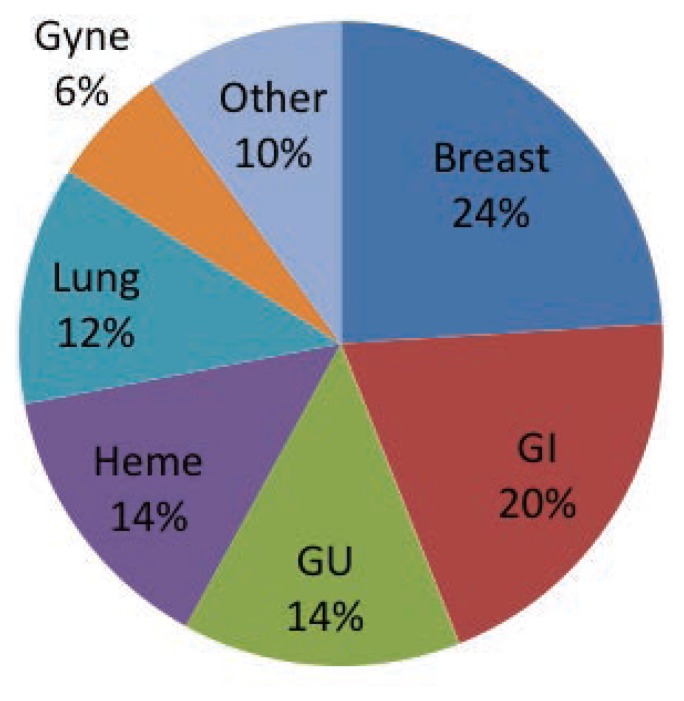

The primary goal of this evaluation was to demonstrate the impact of the CPN role on patient and family experience. The examination of workload data collected demonstrates that the CPN role has been utilized by thousands of patients since its inception. The upward trend in CPN utilization has continued since the CPN program was operationalized, with the most recent workload data revealing that over 16,000 CPN visits (3,200 attending and 12,800 non-attending) occurred in the 2015–2016 fiscal year (CPN Dashboard, 2016). During this time period, over 4,400 unique patients received care from a CPN (CPN Dashboard, 2016). CPNs in this program are generalists and provide care to all types of cancer patients (see Figure 7). In addition to this current quantitative data, the qualitative data gathered in the grant period demonstrated that patients appeared to be very satisfied with their experience with their interactions with CPNs as a whole, and indicated that they felt that the navigator provided them valuable continuity, information, and person-centred supportive care.

Figure 7.

Distribution of patients cared for by CPN by cancer type (2015–16)

Secondary areas of evaluation revolved around understanding the experience of being a navigator in the program and the impact that introduction of the navigator role had on the broader health care team, health system, and health system utilization. Although the post implementation quantitative health system data are not yet available, there was a high degree of consistency and agreement across all other areas of evaluation data (patients/families, navigators, healthcare professionals-co-workers, managers, community partners, primary care). The CPN role enhanced the amount of available support in community settings as well as improved team function and system effectiveness. Navigators perceived that they had a positive effect on the experience of patients and families, and identified very similar areas of impact as the patients and families identified. Other healthcare professionals reported integration of the navigator role improved supportive care for patients, collaborative practice within the team, and system effectiveness. Furthermore, team members recognized that the navigator role had a direct benefit on their own well-being as they were comforted by knowing the navigator could help their patients if needed. A consistent theme across all sources of data was that the navigator role provided meaningful support because the navigator was able to focus their interventions on what was an issue for the patient/family and was available when needed across the cancer trajectory. This reinforces that navigation is a key driver towards building a more person-centred system (CPAC, 2012).

The baseline health system utilization data offer a glimpse of the burden cancer places on the health care and primary care systems across Alberta. However, it only represents the system utilization of newly diagnosed cancer patients within the first year post diagnosis. This does not acknowledge how those patients will utilize health services related to survivorship issues, follow-up, chronic care, or long term surveillance. Nor does it address health system utilization resulting from recurrence, late effects of treatment, or the utilization of the system by family members who are impacted by cancer. Even within this limited scope, the baseline data identified some cancer patients are high utilizers of healthcare services (i.e., more than 15 visits in year post diagnosis). This contributes to the strain on the health care system, to the point where sustainability is one of the top priorities for the government and the citizens of Alberta. Evidence suggests that by addressing the navigational needs of individuals in a timely manner, health system utilization will be decreased (AHS, 2011). Unfortunately, this decrease could not be demonstrated quantitatively in this evaluation due to time delays in accessing health system utilization data for the 2014 calendar year. However, according to patient self-reported data, there was a noticeable reduction in both ER visits and admissions in the post implementation survey responses from patients who had received care from a CPN.

Current workload measures since the CPN program was operationalized demonstrate that program utilization continues to grow as the navigator roles become more established and integrated. These measures also highlight that, although navigators care for patients at multiple time points across their journey, the majority of the navigators’ work has been focused on caring for patients in the pre-treatment phase of their journey (35%), supporting patients with complex care needs during curative treatment (20%), and treatments for ongoing disease control (26%) (CPN Dashboard, 2016). Currently, CPNs do a relatively small amount of work in the areas of post treatment transitioning, survivorship, recurrence, or palliation. Current workload data viewed on the CPN Dashboard (2016) also reveals the most common area of CPN intervention is providing access to information (24% of care interactions), which aligns with areas of meaningful supports that were identified by both the patients and the navigators. This is followed closely by care interactions, which facilitate continuity (23%), care coordination (18%), referrals (15%), and the provision of supportive care (12%). Resolving practical issues (5%) and system issues (3%) were less common.

Navigators found the provincial professional development support offered to implement and optimize the role helpful, but indicated that there was more work to do around role clarity, program awareness and utilization, and further role development. Similar areas for program improvement were identified by other groups that provided feedback. At the end of the grant period all navigators were interested in remaining as their community navigator. As a result of feedback gathered in the program evaluation, work is currently underway to improve awareness of the CPN program and the CPN role in primary care settings. Additionally, there are ongoing efforts to further support optimized CPN role integration within the provincial cancer system, specifically within the ambulatory care settings in each rural and isolated urban site where CPN roles exist.

CONCLUSION

In 2012, the provincial cancer care agency in Alberta undertook a daunting task to develop, implement, and evaluate the impact of a provincial CPN program spanning 15 isolated urban cancer care delivery centres. In order to achieve this goal, a provincial plan was required, followed by an implementation phase and a robust program evaluation. The focus of this third and final article in this series was to highlight the outcomes achieved and report on the program evaluation findings. The knowledge shared through this series of articles adds to the knowledge base regarding how to implement, evaluate, and support a large scale CPN program and highlights the impact such a program can have on the patient experience, team functioning, care coordination, and health system utilization. Much collective learning has occurred as a result of the implementation of this provincial CPN program. It is hoped that through sharing these learnings, similar programs will have evidence upon which to base their program design decisions, as well as a more informed starting place to begin program planning and development, thus leveraging health system transformation and person-centred care delivery forward.

REFERENCES

- Alberta Cancer Foundation (ACF) Annual progress report. 2015. Retrieved from http://albertacancer.ca/progress-report/spring-2015/patient-navigators.

- Alberta Health (AH) Changing our future: Alberta’s cancer plan to 2030. 2013. Retrieved from http://www.health.alberta.ca/documents/Cancer-Plan-Alberta-2013.pdf.

- Alberta Health Services (AHS) Navigation supports in Alberta’s Health Care System [Internal Document] 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Alberta Research Ethics Community Consensus Initiative (ARECCI) ARECCI guidelines for quality improvement and evaluation projects. 2012. Retrieved from http://www.aihealthsolutions.ca/initiatives-partnerships/arecci-a-project-ethics-community-consensus-initiative/ [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Anderson J, Champ S, Vimy K, DeIure J, Watson L. Developing a provincial cancer patient navigation program utilizing a quality improvement approach: Part one-designing and implementing. Canadian Oncology Nursing Journal. 2016;26(2):122–128. doi: 10.5737/23688076262122128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Partnership Against Cancer (CPAC) Navigation: A guide to implementing best practices in Person-Centred Care. 2012. Retrieved from http://www.cancerview.ca/idc/groups/public/documents/webcontent/guide_implement_nav.pdf.

- Cancer patient navigator workload data. CPN Dashboard. 2016. Retrieved from https://tableau.albertahealthservices.ca/#/workbooks/15481/views [Internal website/document]

- Cook S, Fillion L, Fitch MI, Veillette AM, Matheson T, Aubin M, Rainville F. Core areas of practice and associated competencies for nurses working as professional cancer navigators. Canadian Oncology Nursing Journal/Revue Canadienne de soins infirmiers en oncologie. 2013;23(1):44–52. doi: 10.5737/1181912x2314452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fereday J, Muir-Cochrane E. Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. International Journal of Qualitative Methods. 2006;5(1):1–11. Retrieved from https://sites.ualberta.ca/~iiqm/backissues/5_1/PDF/FEREDAY.PDF. [Google Scholar]

- Fillion L, Cook S, Veillette A, Aubin M, de Serres M, Rainville F, Doll R. Professional navigation framework: Elaboration and validation in a Canadian context. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2012;39(1):58–69. doi: 10.1188/12.ONF.E58-E69A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillion L, de Serres M, Cook S, Goupil RL, Bairati I, Doll R. Professional patient navigation in head and neck cancer. Seminars in Oncology Nursing. 2009;25:212–221. doi: 10.1016/soncn.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guadagnalo AB, Dohan D, Raich P. Metrics for evaluating patient navigation during cancer diagnosis and treatment. Cancer. 2011;117(5):3565–3574. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langley G, Moen R, Nolan K, Nolan T, Norman C, Provost L. The Improvement Guide: A Practical Approach to Enhancing Organisational Performance. San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen A, Hack T. Pilots of oncology health care: A concept analysis of the patient navigator role. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2010;37(1):55–60. doi: 10.1188/10.ONF.5560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt-Chapman M, Willis A. Community cancer center administration and support for navigation services. Seminars in Oncology Nursing. 2013;29(2):141–148. doi: 10.1016/soncn.2013.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schutz A. In: The phenomenology of the social world. Walsh G, Lehnert F, translators. Evanston, IL: North Western University Press; 1967. (Original German work published 1932) [Google Scholar]

- Suter E, Arndt J, Arthur N, Parboosingh J, Taylor E, Deutschlander S. Role understanding and effective communication as core competencies for collaborative practice. Journal of Interprofessional Care. 2009;23(1):41–51. doi: 10.1080/13561820802338579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamagawa R, Groff S, Anderson J, Champ S, DeIure A, Looyis J, Watson L. The effects of a provincialwide implementation of Screening for Distress on healthcare professionals’ confidence and understanding of person-centred care in oncology. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2016;14:1259–1266. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2016.0135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson L, Anderson J, Champ S, Vimy K, DeIure A. Developing a provincial cancer patient navigation program utilizing a quality improvement approach: Part two-—Developing a navigation education framework. Canadian Oncology Nursing Journal. 2016;26(3):194–202. doi: 10.5737/23688076262194202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson L, Groff S, Tamagawa R, Looyis J, Farkas S, Scheitel B, Bultz B. Evaluating the impact of provincial implementation of screening for distress on quality of life, symptom reports, and psychosocial well-being in patients with cancer. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2016;14(2):164–72. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2016.0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells KJ, Battaglia TA, Dudley DJ, Garcia R, Greene A, Calhoun E, Raich PC. Patient navigation: State of the art or is it science? Cancer. 2008;113(8):1999–2010. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Medical Association (WMA) Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. 2008. Retrieved from http://www.wma.net/en/30publications/10policies/b3/17c.pdf. [PubMed]