Abstract

Most research to date in the area of head and neck cancer has focused on the efficacy of treatment modalities and the assessment and management of treatment side effects and toxicities. Little or no attention has been directed toward understanding patients’ experience of receiving radiation treatment for the management of their cancer.

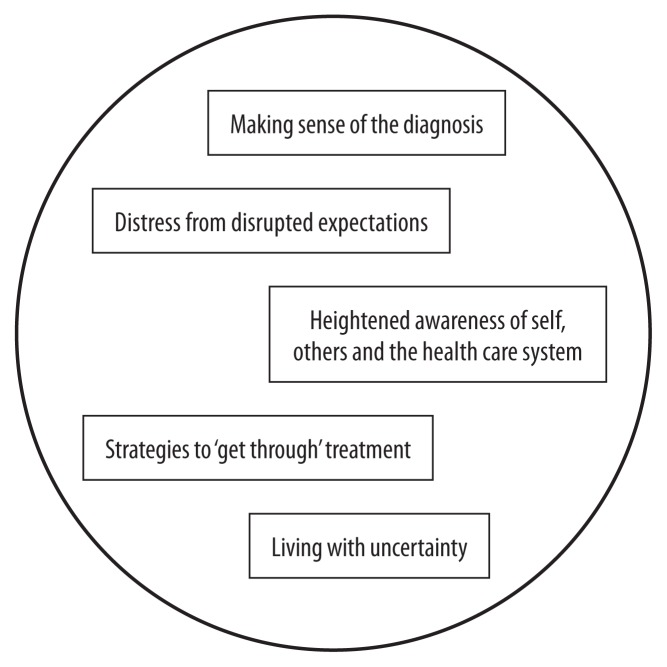

The purpose of this qualitative study was to explore the experience of individuals receiving radiation treatment for a cancer of the head and neck. Face-to-face interviews were conducted with 17 individuals. Thorne’s (1997) approach of interpretive description along with Giorgi’s analytical technique for analysis were used. Experiences across interviews revealed five main themes: 1) making sense of the diagnosis, 2) distress from disrupted expectations, 3) heightened awareness of self, others and the health care system, 4) strategies to ‘get through’ treatment, and 5) living with uncertainty. Findings from the study have contributed to the development of head and neck cancer-specific patient support and education programs for patients and families.

INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND

There are approximately 5,500 new cases of oral and laryngeal cancer diagnosed annually in Canada, and about 1,600 deaths attributed to head and neck cancers (HNC) (Canadian Cancer Society Canadian Cancer Statistics, 2015). Cancers of the head and neck account for less than five percent of all adult cancers, but the diagnosis, treatment and ongoing effects can be overwhelming for patients. About 60 percent are diagnosed with advanced disease. The incidence is twice as high in men as in women. Traditionally, patients with head and neck cancers tend to develop the disease after decades of chronic alcohol use and/or smoking. However, over the past several years, patient populations are increasingly heterogeneous with significant minorities of non-English-speaking patients, the very elderly, and now, younger patients with virally associated (HPV) cancers (Fakhry & D’Souza, 2013).

Primary radiation treatment is used in early stage disease and often combined with chemotherapy or targeted agents in more advanced cancers. Advances in treatment has resulted in patients living longer and being cured of their disease, although the statistics are positively skewed by the HPV-related cancers that show improved treatment outcomes (Ang et al., 2010; Ringash, 2015). Patients have to face a new and potentially life-threatening diagnosis, while at the same time learning to interact with a health care system that may be foreign and frightening. Patients receive a great deal of information at the time of diagnosis and start of treatment and are expected to take on many new self-management activities as an outpatient. The period following the completion of therapy is another change for these patients and may also be difficult because ongoing support is not as accessible or frequent as during the treatment interval (Eades, Chasen & Bhargava, 2009).

Treatment can be particularly debilitating and patients can suffer a host of short- and long-term physical, functional and psychosocial problems including pain, fatigue, difficulties with xerostomia, chewing and eating, dysphagia, odynophagia, loss of taste and appetite, malnutrition, candidiasis, weight loss, changes in speech, trismus, dental issues, facial disfigurement, skin reactions and fibrosis, reduced activity and participation in enjoyable activities, poorer quality of life, anxiety and depression, body image disturbance, changes to social functioning, sense of self and other psychosocial challenges (Cartmill, Cornwell, Ward, Davidson, Porceddu et al., 2012; Lang, France, Williams, Humphries, Wells et al., 2013; Molassiotis & Rogers, 2012; Nund et al., 2014; Penner, 2009; Wells et al., 2015). The impact on patients and families is profound and relatively fewer resources are available for ongoing support and rehabilitation, as compared to patients with more common types of cancer for which strong advocacy groups exist.

Literature provides support that the diagnosis and treatment of HNC is associated with significant changes, symptomatology and impact on quality of life both during and after treatment. While there is increased understanding of treatment outcomes and the physical and functional sequelae of treatment, less is known about the overall experience of individuals with HNC receiving radiation therapy and dealing with the transitions over the course of treatment, recovery, and post-treatment survivorship.

The literature identifies the significant changes and symptomology associated with HNC, but many studies have used predefined variables or defined the patients’ experience from the researcher’s perspective. What is missing is the holistic understanding of the experience of receiving radiation for HNC from the perspective of those experiencing it. Thus, the purpose of this study was to gain an understanding of what it was like to receive radiation treatment for head and neck cancer from the perspective of those who had undergone treatment. Ethical approval was obtained from the research ethics boards prior to beginning this work.

METHODS

Design

This study utilized the interpretive descriptive approach based on the methodological work by Thorne (Thorne, 1997; Thorne, Reimer Kirham, & O’Flynn-Magee, 2004). Interpretive description is an inductive analytic methodological approach that can be applied to complex human problems in order to inform practice and produce knowledge for clinical understanding and direct application (Thorne, 1997; Thorne, et al., 2004). Like other qualitative methodologies this approach emphasizes: 1) an exploration into the understanding of the phenomenon from the participant’s viewpoint or insider perspective, 2) a contextual inquiry, and 3) acknowledging the participation of the researcher in the research (Streubert & Carpenter, 1999).

Sample and setting

The participants in this study were accrued from the group of patients attending the ambulatory HNC clinic in a large urban comprehensive cancer centre for follow-up care after completing their radiation treatment. Purposive sample selection was used to seek participants representing demographic variation (men, women, younger and older participants, etc.), but whose experience and perspectives would have elements that are shared by others. Seventeen participants were accrued for the study, sufficient to permit the information-rich, case-oriented analysis of qualitative inquiry (Sandelowski, 1995; Thorne, 2008). While the sample included patients receiving varying lengths of treatment, the participants were interviewed at approximately the same phase of care, three to four months following the completion of treatment. All participants were 18 years of age or older, had received their full course of radiation treatment, were able to read and verbally communicate in English, and resided within 50 miles of the cancer centre.

Procedure

The interviews were conducted either in the participant’s home or in the researcher’s office, depending on the choice of the participant. Participants were encouraged to tell the story about their experience of receiving radiation treatment for their cancer diagnosis. The initial question was, “What has it been like for you to experience radiation treatment for your cancer”? An interview guide with prompts was used based on the chronology of diagnosis, planning, and treatment to ensure covering all ideas of interest and facilitate patients talking about their experience.

The majority of interviews took approximately one hour to complete. An additional 10–15 minutes was taken at the beginning of the interview to confirm and obtain written voluntary consent, set up recording equipment, and ensure that the participant felt comfortable.

Data analysis

All interviews were transcribed verbatim in preparation for data analysis. Giorgi’s (1985) analytical technique was chosen as the method of analysis for the study since it supported a repeated immersion into the data prior to coding, classifying, or creating linkages. Entire descriptions of the participants’ experience, or all of the interviews, were read to get a sense of the whole story prior to beginning to code. This was followed by identifying transition units or units of description and extracting significant statements or phrases from the transcript that reflected the beginning and ending of an expression of a thought and directly pertained to the participant’s experience. This process in the analysis constituted discrimination of the data through describing the events without changing the participant’s language. The statements surrounding the identified transition units, within the individual interview, are also examined to maintain context of the constituent. The transitions or meaning units were then linked together within each interview and examined for what they revealed about the experience through relating constituents to each other and to the whole. Analysis was done within interviews and then across interviews, to transform the concrete language of the participant into a consistent descriptive statement about the experience of participants. Descriptive statements were used to illustrate the situated description while retaining the meaning of the treatment experience for individual participants. Interpretative analysis included cognitive processes of comprehending, synthesizing, theorizing and recontextualizing (Morse, 1994) resulting in the development of the themes which were conceptualized from the descriptive statements across interviews and supported with representative quotes (Thorne, 2008).

Rigour was ensured through the four criteria of credibility, fittingness, auditability, and confirmability (Sandelowski, 1986, 1993). Strategies included investigator responsiveness and reflexivity, methodological coherence, purposeful sampling, an active analytic stance and thematic saturation (Morse, 2003; Sandelowski, 2000; Thorne, 1997). Additionally strategies included a review of existing literature for “fittingness” of the results, and tracking analytical and process decisions in a research journal.

Following initial analysis of the data, a single 90-minute focus group was held during an evening at the hospital. This was done to ensure that the themes reflected participant experiences.

RESULTS

Twenty-six participants were approached in clinic and given information about the study. All agreed to be contacted by the researcher for further information. Seventeen participated in an interview while five declined after contact by the researcher, two could not be reached by telephone, and two were assessed by the researcher as ineligible to participate. Nine interviews took place in the researcher’s office and eight in the home of the participant.

Twelve of the 17 people interviewed indicated interest in being contacted about the focus group. Between the time of the original interview, and the time of the focus group, two of the 12 had been diagnosed with a new primary lung cancer and one had a recurrence of the head and neck cancer. One participant was out of the country and four were unable to attend due to travel distance. Four individuals were able to participate in the focus group. The focus group took approximately 90 minutes to complete. All attending individuals participated and provided feedback about whether the themes and quotes reflected their experience. No changes were made to the themes since participants agreed that the themes and quotes reflected their experiences.

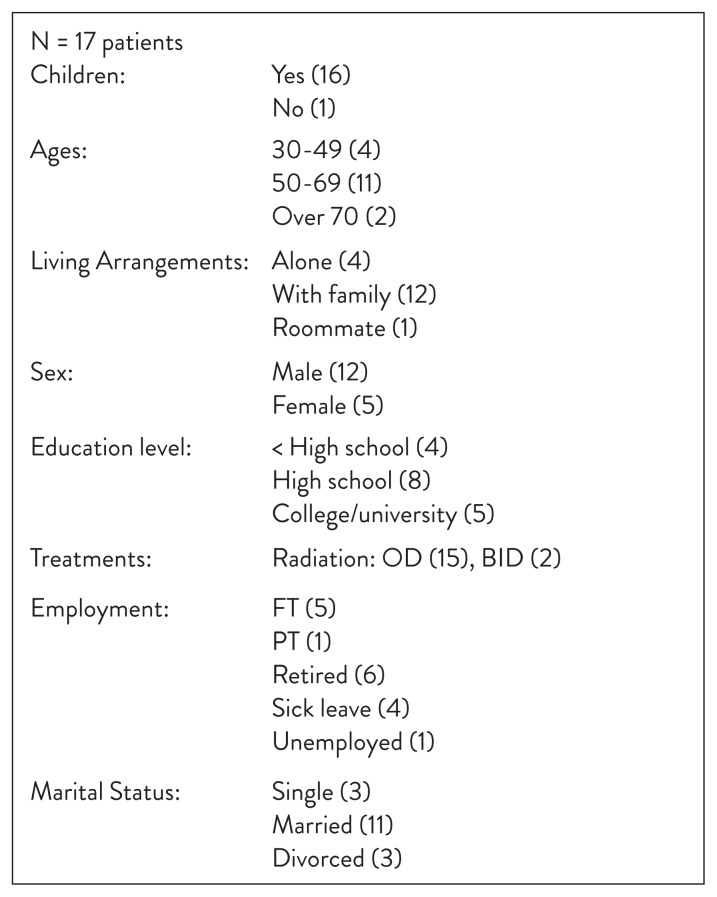

Demographics

The demographic results are presented in Figure 1. Twelve males and five females were interviewed, most (11) were 50–69 years of age, and received once-daily radiation treatment. Two were treated with a hyperfractionation (twice daily) treatment protocol. The majority of participants (11) were married and living with family (12). While five participants had college or university education, the remainder had some high school (8) and four participants had less than high school education. Five participants had recent distressing life events within the previous six months, including the death of an immediate family member, a spouse having been diagnosed with cancer at the same time or shortly before, or friends who had been recently diagnosed with cancer.

Figure 1.

Demographic Results

Interview Data—Themes

Five significant themes were derived from the data and are identified in a conceptual map in Figure 2. Themes do not reflect a linear conceptualization by the participants’ or by the researcher, and do not reflect a hierarchical order. While the themes may initially appear to reflect a chronology of participants’ experience, there is fluidity within and between themes. Pseudonym or fictitious initials are used to ensure the confidentiality of each participant.

Figure 2.

Themes

All participants in the focus group indicated that the themes were reflective of, and captured the essence of their experience during treatment. There was full agreement and support for the themes. No new perspectives about the data emerged from the focus group.

Theme 1—Making sense of the diagnosis

Participants talked about being overwhelmed, shocked, worried, and associating cancer with death and their own fear of dying. A future once assumed full of promise was now changed to one of potentially facing their own mortality. The initial search for meaning (i.e., understanding what happened) led participants to reflect on attributes of causation (why), as well as ‘why me’ and to later reflect upon questions of personal responsibility for their current situation (risks related to diet, work, smoking, lifestyle).

The majority of participants sought consultation with a physician because they experienced intermittent or ongoing symptoms such as sore throat, irritation when swallowing, or felt a lump in their neck and suspected something was wrong. While the majority were suspicious something was wrong, no one initially thought of cancer as a possible reason for the symptoms. Despite two-thirds being smokers at the time of seeking consultation, none of the participants made a connection between their symptoms and a possible diagnosis of cancer. Many attributed their symptoms to causes such as a cold or infection, the weather, or a previous benign condition. All participants expressed feeling completely shocked by the suggestion that a biopsy was needed and upon hearing the subsequent diagnosis of cancer.

Uhm, and he’s (family doctor) sitting in his chair and he says ‘biopsy’, and that’s when I thought I had a fatal heart attack, cause it was the farthest thing from my mind. He took a biopsy, and then three days later he says, ‘guess what’? And that’s where it started. … And when he said those words (cancer), I mean, that was another ballgame altogether. It’s all over. You know, uh, ok, let’s get it together. I couldn’t believe it. I mean the word to me at 57, at my age, and growing up with that word, well, get your act together. I was in a state of tunnel vision when he was talking to me. I didn’t hear a damn thing he said. It’s overwhelming. It’s absolutely overwhelming. (AS)

The confirmation of the cancer diagnosis elicited emotional reactions such as worry, reflections questioning ‘why me’, thoughts of death, and questions about the reality of the diagnosis. Cancer was first and foremost equated with dying. Participants described trying to appraise the situation and make sense of their cancer diagnosis and its implications. They expressed feeling brought up short by the shock of diagnosis, halting the normal expected flow of their life. Panic and worry emerged, as they started to think about having cancer. Participants questioned ‘why me’ and tried to find explanations for having cancer. Worry led participants to think about the meaning of their situation.

Once I found out I was positive, that kind of took the wind out of my sails and put me on a kind of an emotional roller-coaster for about a week. We’re now fighting an enemy that we couldn’t fight in the traditional ways, so like I say, it took me about a week to really come to grips with what I was dealing with. (HH)

The diagnosis had a profound disruption on participants’ sense of self and their emotional well-being. Participants felt overwhelmed both in terms of receiving the diagnosis and what it meant to them in terms of their past and their now uncertain future. They experienced fear and terror, as they began to integrate having received a diagnosis of cancer and understand what it meant to them. The impact of hearing the diagnosis in the doctor’s office and having time to reflect prior to being seen at the cancer centre left people on their own to deal with their worries. This led to sleeplessness, anxiety, not being able to eat, and making conclusions that the cancer meant it was all over and they were going to die.

Some days my mind was really in another place, when I kind of worked myself into these little cycles where I played out a worst case scenario and what would happen. (GG)

Only one individual was able to identify a formal resource or support person outside of the family from whom they could receive support during this period of time.

Many did not have any reference point for comparison, not having known anyone with cancer of the head and neck. While most individuals may know someone or certainly hear about someone with an acute or chronic illness such as heart disease, or breast cancer, and smokers may even know someone with lung disease, participants certainly did not make the connection between smoking and head and neck cancer. Attribution of cause was not associated with smoking or self-identified risk factors. While no one spoke about punishment or getting cancer directly from something they had done, some participants’ reflected upon other causes such as work, lack of sleep, poor eating habits or the impact of how they had lived their life. This early phase following diagnosis was marked by a halting of their current reality; an abrupt disruption in normal routines including sleeping and eating, and being left to their own thoughts, interpretations and meanings without adequate resources or supports.

Theme 2—Distress from disrupted expectations

The second theme included feelings about what life should be like, changes in routines (waiting, side effects disruption, the loss of independence) and the changed meaning of food (McQuestion, Fitch & Howell, 2011). Participants described a disruption in their expectations about their lives or a halting of life, as they had thought it would unfold. Life was expected to have taken a particular course or path and suddenly that path was disrupted. The changes led them to reflect and search for an explanation about why this had happened to them, as well as reflect upon past events or unresolved issues in their life. They talked about what they “should” be doing in terms of work, focusing on family, plans for retirement, retiring or starting a new business. They struggled to make sense of the changes to their everyday life and what was no longer a taken-for-granted plan or set of activities and behaviours.

I could have retired in October. I’m still at it a bit, you know…thinking [about] the plans I had, well a year prior with my wife’s cancer, and that was a prelude to me. (AS)

Coincident with this were changes in normal life routines and the need to adapt to new routines dictated by the diagnosis and subsequent treatment. Participants described feeling over-whelmed with so many changes happening all together. Waiting, coping with side effects and loss of independence emerged as significant aspects of the way people had to manage their lives. Waiting between diagnoses and being seen at the cancer centre, waiting for treatment to start, waiting due to treatment machine delays, waiting for appointments and transportation all impacted on their experience of long days during the treatment period. During the diagnostic phase they described feeling in limbo and having thoughts that fluctuated between the worst-case and best-case scenarios. Once they were in the cancer system participants felt some relief. The feelings and self-determined interpretations of the waiting, led to increased anxiety.

So there was actually a period of time that all I knew was that I had cancer. Although they told me it was “X” cell carcinoma, I didn’t have it written down, so all I had was a medical term describing my cancer. And I guess, in the back of my mind, I thought it could be as bad as terminal to really being nothing, something very treatable. (GG)

Participants describe a range of side effects. Their experience was one of feeling the impact of multiple side effects together. While they had expected side effects based on the information they had received from care providers or in written material, they described discrepancies between what they were told and what the that information meant to them.

It’s because after 21 days, whatever, suddenly everything hurts, and it burns out, you know. Everything is dead inside, I don’t know, like raw meat or whatever. I was miserable and because there is much pain and I couldn’t swallow. I mean when it’s written SORE, it just means sore throat, like getting a cold. That was what I thought it would be, didn’t dawn on me to wake up one morning, you swallow and it’s a nightmare. (SH)

Side effects were constant reminders of what they ‘couldn’t’ do. Participants talked about not truly realizing what the impact of treatment was going to be like. More than just being a hassle, participants described side effects in terms of a loss of something they had loved or enjoyed as a normal part of their life. For many, taste changes and mouth sores prevented the enjoyment of food and difficulties eating, leading to weight loss. Participants talked about difficulties of multiple side effects occurring together. While they knew cognitively what to do to manage side effects, such as regular oral rinsing to manage the thick saliva and oral dryness, the magnitude of that impact was not expected.

But you get the information but you can’t imagine that you’re going to go through that. You can’t imagine…like when Dr. X said ‘you won’t have any more saliva’, oh I thought, well that’s ok, I’ll manage. But I never thought my mouth and throat will be that dry. I never realized all the problems I would have with eating. (EG)

Side effects continued for several weeks after the completion of treatment. Most participants stated they expected the side effects to resolve faster than they did. Although they had been told to expect a long recovery, the actual course of recovery was perceived as being extremely slow. Participants frequently described hoping that each day would bring improvement.

I always thought to myself, things will get better, next week, next week, but next week never comes. But I was always hoping (for the) next day, next week. (CKY)

Difficulties with loss of taste, appetite and difficulties with eating were associated with physical, social and emotional losses. This included the loss of favourite or enjoyable foods they could no longer eat, the loss of the pleasure and enjoyment of eating, as well as the impact on social interactions related to symptoms or the amount of time it would take to eat. Food was no longer a taken-for-granted pleasure and a normal part of life. Food had taken on new meanings. Participants described the short-term and longer-term impact on their social lives because of the changes in eating and food.

Participants experienced a loss of independence and were not able to engage in their usual activities to maintain independence. Many struggled with needing to accept help from others and described the loss of independence in terms of a loss of control. Needing help contrasted or challenged their perception of what it was to be strong and not wanting to be disruptive or a burden to others.

Theme 3—Heightened awareness of self, others and the health care system

Participants described experiencing an increased awareness of their surroundings, of cancer and of themselves, as a cancer patient, after their diagnosis. Their attention was caught and drawn to cancer through observing or being exposed to cancer in the media (i.e., newspaper or magazines) or being exposed to fundraising initiatives. They found themselves comparing their situation with that of others, seeing others at the cancer centre they thought were worse off than themselves, and being aware of others in the community who had survived cancer or were living with cancer. This awareness meant they were not the “only one” going through the same experiences. The isolation of being alone was reduced and the notion of others having survived the disease was comforting.

Okay, it’s not as bad as when you first hear the word cancer and you start to recognize and you start looking for examples in society. Just because you’re given a cancer diagnosis doesn’t mean that that’s a death sentence. There are many people that beat cancer and are walking amongst us, are working amongst us, and living amongst us. (GG)

Participants made comparisons between themselves and other patients receiving treatment. Many talked about how things could have been worse for themselves. Recognizing how their own situation could have been more difficult helped them appreciate their own situation in coping with and adapting to cancer and the associated disruptions. They also talked about others being worse off, seeing themselves in a more favourable perspective or position in comparison to others. It reinforced that they were not as bad off as they might have thought.

Life is life. I’m alive today. I’m going to live today. And that’s sort of where my mind is. It comes from because I saw little children with cancer that are much younger than I and have not experienced all the things that I’ve experienced, having been so lucky to experience, and they may get taken early. How fair is that? (DP)

Participants described noticing stories or the mention of cancer in the media more since their diagnosis. This was not a function of actually seeking out specific information, but rather being more aware of the number of times cancer is mentioned in everyday life. In the past, prior to their own personal exposure, they had not noticed these references to cancer. The personal experience had heightened their awareness and made these references more relevant. As participants became more aware of the disease and its treatment they found themselves reflective about and thankful for the highly skilled individuals in the health care system. A number expressed comments about being lucky to be in Canada and being able to receive their treatment in this country. Those who had lived in other parts of the world and had experienced other health care systems identified that other countries do not have the resources Canada has for health care or cancer care.

I’m also aware that, you know, in a lot of countries you wouldn’t get the treatment at all. It’s easy to assess or criticize things from an outsider, but it becomes much different when you become actually part of it. You have a whole different perspective once you’re part of it and once you’ve integrated into it. You have a different outlook, and I think that whole learning experience was a positive experience for me. (HH)

Theme 4—Strategies to ‘get through’ treatment

Participants identified a variety of activities, strategies or approaches they used to ‘get through treatment’ and cope with the diagnosis and treatment. Listening to advice from the doctors and nurses, staying focused on the day-to-day while being attentive to tomorrow and a positive outcome of treatment, being positive and mentally tough, maintaining a routine, engaging in activities that would distract, using humour, and accessing support from others were strategies identified by many participants. Participants indicated that some of these strategies were similar to those that were helpful during other stressful situations or events in the past, or had been suggested by friends who had gone through cancer treatment.

Throughout the whole thing, from when they first told me I needed radiation. Then I’m going to get radiation you know, because I want to get better. I don’t want to have this disease go any further than it has now. So I think that’s a positive thing for people to pick up on and use as a tool. (DP)

Maintaining routines of exercise, such as walking to treatment and work, was an important focus for many. Their routines served as reminders of what was important to them, what was valued, and who they really were. Staying with a routine acknowledged and reflected a capacity on their part to fight over the cancer. They could set goals about what they were doing day by day and how they would exert control over their day.

Listening to music, reading, knitting, and doing crossword puzzles were activities that participants used to cope with waiting and getting through the daily routine of coming for treatment. These activities could be seen as distractions, or as ways to fill the time, keep busy or doing something enjoyable. During the actual treatment, mental imagery was often used as a distraction to get through the time in the radiation treatment unit. Imagery was helpful for several people during the treatment episode while lying on the table with the mask bolted down to prevent any movement.

There were a couple of days where the mask felt like it was too tight. But what I did, I listened to music each time I went in there. They have a CD player and you can listen to music while you’re getting treatment. So I’d go away to a different place that way, or I would just go away to a different place mentally. That’s why I said it’s good to be. Mental toughness is really a huge thing. (DP)

The use of humour helped participants with the day-to-day routine of treatment, managing side effects, and coping with treatment in general. Recognizing and accessing support from others including family, friends, colleagues, support groups and church members provided an important way of expressing feelings and maintaining hope. Spiritual and religious beliefs were powerful strategies used by some participants both for personal strength as well as a venue for seeking support from others.

Theme 5—Living with uncertainty

All participants saw the future as uncertain and the majority spoke about it with a cautious optimism. They were cognizant of the potential for recurrence, but at the same time were starting to move forward with their lives. Many talked about getting back to the normal activities of their life before cancer. They struggled with knowing and believing the cancer had been cured, yet they also expressed a strong desire to move beyond the cancer experience and to leave it behind. Their challenge was to find a way to live with the uncertainty that the cancer could come back.

I’ll say that, in my mind, I haven’t resolved the fact that I’m cured. I go for my MRI, I know that there’s a possibility that the scan will show something, and if it doesn’t I know there is the possibility that in a year from now or two years from now, that a scan may show something. I know that based on this type of cancer that maybe if within X number of years something doesn’t show up and in all likelihood nothing will show up after that, but those are probabilities. Although, in my mind, I would like to say that I have a clean bill of health. I know I’m not going to, and so, I’d be lying if I said that that’s not going to impact me. That has impacted me. But I don’t want that to affect me. … In many ways our lives are back to normal. This is something that I can’t say I’m past that obstacle, that hurdle in my life and I’ve cleared it. Well I may have cleared the majority of it, but I haven’t cleared it entirely. So, I still approach things cautiously. (GG)

Many participants were thinking about the future, making adjustments and making beginning transitions to a new normal. They were assessing their life, what they still had in their life that was meaningful to them and what was and what wasn’t important. A few participants were pragmatic about the future, as well as life and death. They talked about the possibility of dying from the cancer, but they could also die from something else. Several participants talked about how the cancer and treatment experience had changed their perspective on the priorities in their lives. For most, they recognized they were living without guarantees and it was important to live for today. They found they became more philosophical about life. The brush with mortality had forced them to take stock of what was important to them.

No matter how much money you have, you cannot change yesterday. It’s a poem. It’s excellent. You cannot change yesterday, you can’t. It’s done. It’s a done deal. You have no control of tomorrow. The sun will come up and go down and the moon will come up and go. You have no control. You have control of this moment right now. Live for today and that’s what we do. Enjoy today, it’s a beautiful poem. (SH)

Despite treatment being completed, uncertainty continued to have a disruptive and emotionally stressful impact on participants. Even though acute side effects from treatment were resolving for many and individuals began to resume some normal routines, the concern and burden of recurrence was a haunting reminder of an uncertain future. Participants were likely still grappling with changes, trying to figure out what was temporary or permanent and working through a process of adjustment. They were beginning to learn to live with uncertainty. The lack of control over an unknown future led many to rethink their priorities in life and to live for today.

DISCUSSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS

Making sense of the diagnosis

The diagnosis of cancer can have a devastating impact on a person’s life, leading the individual to question the direction of their life, as they confront their own mortality, sometimes for the first time. Having a diagnosis of any type of cancer brings crisis, change and disruption, uncertainty, and loss to the forefront of one’s life (Björklund, Sarvimaki, & Berg, 2010; Lang et al., 2013). Findings from this study are consistent with existing literature. Some authors have identified that the initial response to the impact of a diagnosis of cancer is that of ‘existential plight’ where there is a focus on the meaning of one’s life and illness as well as thoughts and fears of death (Howell, 1998; Lee, 2008). The diagnosis is a catastrophic event associated with feelings of shock and distress as people strive to integrate the devastating information they have received from their physicians and try to make sense of it (Lang et al., 2013). The diagnosis causes individuals to be “immediately shocked out of the complacency of their assumed futurity of their existence and their whole conception of themselves, their life and their world” (Crossley, 2002, p. 440). Individuals experience a sense of disbelief, denial, and despair as a new reality is slowly recognized (Holland, 1977; 2011).

Despite acknowledging personal risk factors for cancer (i.e., smoking), none of the current study participants made a connection between their symptoms and a diagnosis of cancer. Hence, they were shocked upon hearing the diagnosis. People typically make the connection between smoking and lung cancer, but not to other types of cancer including cancers of the head and neck region. This may be, in part, due to the focus of media attention on smoking as a cause for lung cancer with little attention to other smoking-related cancers.

Distress from disrupted expectations

Disrupted expectations and the associated distress experienced by participants in this study related to the practical day-to-day events associated with waiting for treatment to start, waiting for appointments, changes in work, transportation needs and altered routines required by treatment, dealing with side effects and the physical and functional effects of treatment. Disrupted expectations were also associated with changes to life plans, future directions, and the psychological impact of the cancer diagnosis. Several authors have identified similar impacts of disruptions to daily life experienced by patients and families and the impact on uncertainty, well-being, and being left to their own devices (Björklund et al., 2010; Larsson, Hedelin, & Athlin, 2007; McQuestion et al., 2011).

Many studies related to ‘waiting’ reflect systems issues associated with standard wait times, waiting lists for treatment, the impact on medical outcomes related to treatment delays, or watchful waiting instead of treatment (Belyea et al., 2011; Dimbleby et al., 2013; van Harten et al., 2014). Very little attention has specifically been paid to cancer patients’ descriptions of the impact of waiting. Irvin (2001) synthesized the literature and performed a concept analysis of the term “waiting”. He defined waiting as “a stationary, dynamic, yet unspecified time-frame phenomenon in which manifestations of uncertainty regarding personal outcomes remain in suspension for a limited time” (Irvin, p. 133). The current study gives recognition to the distress that patients experience at the time of diagnosis of cancer and gives voice to the difficult period of waiting between receiving a diagnosis and referral to a cancer treatment centre. For patients with cancer, but specifically patients with head and neck cancer, the current study highlights their experience of not having adequate information, referral to resources in their own community or someone to talk to after receiving the diagnosis. Waiting was marked by a sense of uncertainty, loss of control and isolation, consistent with previous studies (Björklund et al., 2010; Lang et al., 2013; Larsson et al., 2007).

Heightened awareness of self, others and the health care system

Research has shown that people with serious illness may use downward comparisons to enhance self-perception, upward comparisons to seek inspiration and information, or lateral comparison to those who have experienced similar stressors or situations for emotional or information reasons and as a means of coping. (Bellizzi et al., 2006). Festinger (1954) initially described the theory of social comparison processes proposing that individuals would obtain a subjective feeling of meaning and accuracy in their own self-evaluation through comparisons with others. Downward comparison is a coping process and normal pattern of adaptation used by many people in comparing themselves with another who is less fortunate (Bellizzi, et al., 2006). The majority of patients in the current study used downward or lateral comparison in contrasting themselves with others. This may have been because people were reflecting upon their experience during treatment. They were still early in the disease experience, having recently completed treatment, and still living with uncertainty. During the focus group, patients responded that comparing themselves with others who might be worse off was not to find themselves better than someone else but to appreciate where they were. They were coping with the diagnosis and managing through treatment.

Upward comparison with others who are doing well or are more fortunate may provide inspiration or ideas for coping rather than providing direct evaluations. Comparison with others may be particularly beneficial for those who perceive their own health or situation more negatively (Bennenbroek, et al., 2002). The use of upward and downward comparison is not mutually exclusive. Downward comparison may provide the yardstick for an improved self-evaluation and perspective, while at the same time, provides input for coping through seeking information from someone more fortunate.

Strategies to get through treatment

Several authors have studied the psychosocial adaptation to cancer, including the variety of coping styles and strategies used by patients to reduce the emotional distress associated with the diagnosis and treatments. Pioneering work by Lazarus and Folkman (1984) described a cognitive approach to coping that involves primary and secondary appraisal of a situation or event, and use of emotion-focused and problem-focused strategies to cope with the emergent stress. Identified strategies have included engagement coping strategies (e.g., problem solving, planning, information seeking, positive reinterpretation, seeking social support), disengagement coping strategies (e.g., denial, fantasy thinking, problem avoidance, self-blame, social withdrawal, substance abuse), seeking religion, and acceptance of one’s condition. While the literature has focused on the identification and quantification of coping strategies, the frequency or number of strategies used does not always suggest improvement in coping or the outcome of using various strategies over time (Nail, 2001). Interventions using psychoeducational approaches have been shown to improve outcomes when the degree and type of information is linked to an individual’s coping style, degree of self-monitoring and perceived health threat (Roussi & Miller, 2014).

Haisfield-Wolfe et al. (2012) interviewed 21 patients with oropharyngeal or laryngeal cancer in order to describe their coping in the context of uncertainty during radiation treatment with or without chemotherapy. Side effects were distressing but the majority of patients perceived themselves as coping with an upsetting or rough experience. The symptoms as well as fear and anxiety influenced their coping. Social support was utilized as well as strategies of ventilation, disengagement and a broad range of coping strategies to manage throughout the course of treatment.

Participants in the current study identified many of the engagement coping strategies as being used and as helpful: stay focused and positive, information seeking from and listening to the doctor, seeking social support, using humour, getting feelings out, and utilizing religious beliefs and practices. Some strategies were identified for use during the day-to-day routines of waiting or getting through the procedure of the radiation treatment, while other strategies were used to staying positive and focused while getting through the course of treatment and reinforcing their sense of well-being.

Living with uncertainty

Uncertainty has been identified as a significant aspect of living with cancer although the nature of uncertainty varies from diagnosis to treatment to post treatment recovery (Ness, et al., 2013). It is present oriented and is grounded in a person’s perception of the meaning and outcome of a situation (Mishel, 2000). For patients with cancer, uncertainty may be associated with an unconfirmed diagnosis or an ambiguous prognosis, being required to navigate the health care system, dealing with the complexity and unpredictability of the disease and treatment, having insufficient information, the risk of or actual recurrence of disease, perceiving setbacks related to care and treatment, unmanaged physical or emotional symptoms, adjustments required in the individual’s personal and work life, as well as lifestyle, all of which are correlated with a reduced quality of life (Haisfield-Wolfe et al., 2012; Suzuki, 2012). Uncertainty may be related to one’s inability to foretell the future, fears of recurrence, not feeling secure, being in doubt, not being in control or being undecided about an event or decision or feeling a sense of being in captivity (Björklund et al., 2010).

Authors have also written about the temporal orientation of humans in daily life routines and how that future orientation is halted upon receiving a diagnosis of cancer and further challenged with the ongoing existential uncertainty related to fear of recurrence (Blows et al., 2012). Participants in the current study also talked about the disruptions in life expectations and the uncertainty they felt about an expected future. While uncertainty pervades all phases of the cancer experience, participants in the current study talked predominantly about the phase immediately following treatment and learning to live with cautious optimism. They were aware of the potential for recurrence but were hopeful that life would get back to normal, even if they were not sure if that would happen or what that normal would be. The experience of cancer had changed their perspective on priorities in life. They expressed an appreciation of living for today without guarantees.

In a group of patients with head and neck cancer (Wells, 1998), uncertainty was associated with distress, having time to reflect on their experience after having completed treatment, but not having anyone to talk to about their feelings. Clinicians were also less readily available for patients to share their experience and concerns or to gain understanding of what to expect following treatment. Sources and triggers of uncertainty about recurrence may include learning about someone else’s cancer or disease progression; experiencing new aches and pains; exposure to environmental triggers such as sights, sounds and smells that reminded them of their cancer experience; and information seen in the media. Contact with other patients can reduce feelings of uncertainty through social contact, emotional comfort and support (Egestad, 2013).

Compared to other types of cancers, there is limited research in how patients and families living with head and neck cancer experience or manage uncertainty. Current strategies to support patients may include information provision or psychoeducation to reduce stress; screening and early intervention for support and connecting patients with others who have gone through treatment themselves.

STUDY LIMITATIONS

Participants were recruited from follow up clinics in the head and neck cancer clinic. While purposeful sampling was utilized, it is acknowledged that the sample lacks broad variation since most patients had once daily treatment and no one had concurrent chemotherapy. It might be suggested that a study interviewing patients receiving concurrent radiation and chemotherapy or adjuvant chemotherapy may reflect different or unique experiences related to enhanced side effects and symptoms from treatment, hospitalization for part of their treatments, etc. Interviewing participants from a diversity of cultures may also provide other additional perspectives of the experience of receiving radiation treatment for a head and neck cancer.

IMPLICATIONS FOR NURSING PRACTICE, EDUCATION AND RESEARCH

Practice

The results of this study have important implications for patient care and nursing practice. Findings from this study will provide a detailed, rich description of HNC patients’ perspectives regarding the experience of receiving radiation treatment for cancer of the head and neck. This understanding is necessary to develop meaningful and appropriate interventions. The results of this study will provide information to prepare and support future patients undergoing treatment and improve quality of care for this group of patients.

Information and symptom management

Participants identified discrepancies between what they were told and their perceptions of what that information meant to them (e.g., “when it’s written SORE, it just means a sore throat, like getting a cold”). While it is important to provide both written and verbal information, it is critical for nurses and other health care professionals to assess what the patient wants to know, their readiness to learn, and what their understanding is of the information. Reinforcement and clarification of information can prevent misconceptions as well as construed meanings. Preparing patients for what to expect over the course of treatment needs to be individually tailored to the person’s learning style and preference for information. The information needs to be presented in a realistic way without creating fear or anxiety about future events. Utilizing thematic areas in the development of patient education materials may provide insight into what the experience is like from the perspective of an informed participant. Patients would gain an understanding of what to expect through presenting information from an affective as well as cognitive paradigm of education.

Symptoms are often experienced as multiple side effects occurring together rather than as isolated symptoms with a linear presentation. Patient education materials for symptom management are often written as individual symptoms without any discussion of the impact of the symptoms on the individual or how one symptom impacts another. Patients may benefit from patient education materials being written to include the notion of symptom clusters, both in their presentation and interaction as well as their management. For example, mucositis, thick ropey saliva, pain, and difficulty eating often occur as a symptom cluster. Written materials addressing how oral care and pain management can facilitate comfort and eating may assist the patient with utilizing interventions in a more effective way. This also has implications for future research addressing patient education and symptom clusters.

Participants also talked about the difficulty with symptoms continuing longer than anticipated and not knowing when improvements would occur or things get better. It is important to support patients during the transition following treatment when they are at home recovering from treatment. Further attention needs to be paid to better preparing patients for that post treatment phase and the slow recovery. Realistic expectations about the pace of recovery and ways to self-monitor need to be included in the discharge plan.

Support

Improved support ought to be incorporated for patients newly diagnosed, dealing with the shock of diagnosis, and waiting to be seen at the treatment centre. Participants identified that following diagnosis they felt shocked, overwhelmed, that the wind had been taken out of their sails and that they associated cancer with death. They were left on their own to create their own meanings. For many individuals, contact with a specialized oncology registered nurse (SON-RN) may not occur until the time of the first referral appointment at the cancer centre. RNs are well positioned to dialogue with patients about their experience receiving the diagnosis and then provide support in anticipation of meeting them at the cancer centre. Telephone contact with the patient prior to attending the cancer centre would serve to gain an understanding of the patient’s experience and concerns, level of anxiety, the patient’s and family coping styles, and determine preferences for information, as well as language, transportation and other support needs. It would also provide an opportunity for the nurse to acknowledge the patient’s concerns and worries and provide a resource or contact person at the cancer centre or in the community prior to attending the first referral clinic appointment. The model of ambulatory nursing and the nursing role within the clinic setting would require review and modification in order to support nurses to address the needs of patients prior to contact at the first appointment at the cancer centre. Assessment of the individual’s experience would provide a patient centred approach to care in addition to the problem-oriented assessments often done in clinics that predominantly focus on medical history, physical symptoms and what information the patient ‘needs to know’ to start the treatment process.

Participants identified multiple strategies that were used and found to be helpful with coping with treatment and its disruptions. While the recommendation of specific strategies needs to be tailored to the individual, patients also benefit from hearing about strategies that other patients have found helpful. Registered nurses need to be aware of what patients are identifying as helpful and to stay current with the literature in order to best support patients during and after treatment.

It is important to develop and evaluate transitional care models that would support the patient between the community and the treatment centre, both before and after the treatment phase as well as during transitions between providers and care areas within the treatment centre. Models of care following treatment should include ongoing contact with the cancer centre as well as community based programs. Currently few support groups or programs exist specifically for patients with head and neck cancer. International online community support groups exist that focus on the patients who have had disfiguring surgical procedures (About Face - www.about-face.org) or for those living with laryngectomies (International Association of Laryngectomees [IAL] generally known as Lost Cord or New Voice Clubs - www.theial.com). In Ontario, both Wellspring (www.wellspring.ca) and Gilda’s Club (www.gildasclubtoronto.org) have developed general support groups that patients and families living with HNC can attend, and more recently a Men’s Group has been developed to address the needs of male survivors and male partners of people living with cancer. Most community resources are located in urban rather than rural settings, further limiting access. While general support groups and programs may assist patients with living with cancer and concerns that cross populations, specific support programs and resources needs to be developed to meet the unique needs of patients with head and neck cancer, including ongoing difficulties with eating and swallowing and the associated social challenges. In response to this challenge, a site specific cancer survivorship program was developed at the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre to address the needs of patients and families living with head and neck cancer, focusing on program development and research conduct. Two programs were developed to support patients, with one designed at the beginning of treatment through reinforcement of education in a group setting (Prehab Class – Supporting You Through Treatment). A second and a two-part program was also developed to support patients following treatment (Getting Back on Track Following Treatment for Head and Neck Cancer) as they go through various transitions related to the slow improvement of symptoms and changes related to eating and swallowing. A cancer survivorship “map” was created to provide patients and families an understanding of what to expect before, during and after treatment along with information and support resources that can be accessed at specific phases or throughout the cancer journey (http://www.uhn.ca/PrincessMargaret/PatientsFamilies/Clinics_Tests/Head_Neck/Documents/My_Survivorship_Map.pdf).

Health Services and Clinician Education

Despite personal risk factors, none of the participants made the connection between those risk factors and cancer of the head and neck. Tertiary care facilities often focus on treatment and follow up and provide little attention to prevention and education. Despite Canadian accreditation processes incorporating standards addressing health promotion, illness prevention and early detection, the attention of care consistently focuses on treatment and follow up for early detection of recurrence. While facilities need to fiscally allocate resources, cancer centres could collaborate with community agencies to develop and implement educational initiatives addressing risk factors and prevention related to head and neck cancer. Registered nurses and other health care professionals need to be more proactive with addressing risk factors, and in particular smoking and alcohol use, with family members as well. Organization-wide smoking cessation programs are beginning to develop for patients, families and staff.

Research

There are multiple opportunities for future research resulting from the current study. It is important to develop and evaluate transitional care models that would support patients with head and neck cancer both in the community and attending the cancer centre. Patients spend their life in their own community and would benefit from programs and interventions with the focus of care in their own settings. Research is required to address the needs of patients during the period from diagnosis to referral as well as needs following treatment. Identification of needs following treatment would guide appropriate interventions to be either implemented during the treatment experience to better support individuals in preparation for the transition period following treatment, or in the community setting as part of ongoing support.

Understanding of what it means to wait is an important underdeveloped area of research in this group of patients. Traditionally wait times have focused on schedules and waiting for diagnostic services or treatment to commence. It is important to expand this limited perspective of waiting and to provide a voice for patients. A better understanding is needed about what it means to wait and the impact that waiting has on patients, before, during and after treatment.

The geographic referral area, like many large treatment centres in urban settings, has a multicultural population. Do the experiences of participants reflected in this study also reflect the experiences of people from other cultures or communities, for example, Asian patients with nasopharyngeal (NPC) cancer? They may have unique experiences as a result of the genetic link to NPC, cultural meanings and interpretations in the way they may experience the health care system, access to information, and whether individuals are new immigrants versus first generation Canadians.

Research is beginning to address symptom clusters. Research should be directed toward the assessment of how individual symptoms, including oral dryness, mucositis, pain, and difficulty eating impact on each other and the cluster. Cognitive, behavioural and physiological interventions to manage the clusters of symptoms need to be developed and evaluated in order to reduce the disruption and distress from symptoms. Additionally we need to better understand how patients with head and neck cancer cope with changes in expectations around how the body functions and performs.

There is little research describing the experience or impact of uncertainty and fear of recurrence on the lives of those undergoing HNC treatment or living in the months and years following treatment. It is also not clear whether patients with head and neck cancer experience similar triggers for uncertainty and threats of recurrence, or the impact in contrast to other groups of patients.

CONCLUSIONS

This study adds to the present knowledge, describing what it is like to receive treatment, but it also reflects what it is like to live with a diagnosis of head and neck cancer, as experienced and shared by the men and women in this study. It is recognized clinically and in the literature that this group of patients often lacks social support and resources between diagnosis and referral to the treatment centre, as well as during the recovery period and moving into survivorship. Support groups and community resources are limited. The study results provide nurses and other health care professionals with a deeper understanding of patients’ experiences as they face a new diagnosis and the associated treatment. While this study focused on patients with head and neck cancer, the findings related to the feelings of shock, worry, multiple disruptions and changes in routines, the use of multiple coping strategies, heightened awareness of self and others as well as living with uncertainty can be applicable to other patient populations.

REFERENCES

- Ang KK, Harris J, Wheeler R, Weber R, Rosenthal DI, Nguyen-Tan PF, Gillison ML. Human papillomavirus and survival of patients with oropharyngeal cancer. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;363:24–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0912217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellizzi KM, Blank TO, Oakes CE. Social comparison processes in autobiographies of adult cancer survivors. Journal of Health Psychology. 2006;11:777–786. doi: 10.1177/1359105306066637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belyea J, Ribby M, Jaggi R, Hart RD, Trites J, Mark TS. Wait times for head and neck cancer patients in the Maritime Provinces. Journal of Otolaryngology – Head & Neck Surgery. 2011;40:318–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennenbroek FTC, Buunk BP, van der Zee KI, Grol B. Social comparison and patient information: What do cancer patients want? Patient Education and Counseling. 2002;47:5–12. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(02)00018-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Björklund M, Sarvimäki A, Berg A. Living with head and neck cancer: A profile of captivity. Journal of Nursing and Healthcare of Chronic Illness. 2010;2:22–31. [Google Scholar]

- Blows E, Bird L, Seymour J, Cox K. Liminality as a framework for understanding the experiences of cancer survivorship: A literature review. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2012;68:2155–2164. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2012.05995.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Cancer Society Statistics. Government of Canada. Canadian Cancer Society, Statistics Canada, Public Health Agency of Canada, Provincial/Territorial Cancer Registries. 2015. cancer.ca/statistics.

- Cartmill B, Cornwell P, Ward E, Davidson W, Porceddu S. Long-term functional outcomes and patient perspective following altered fractionation radiotherapy with concomitant boost for oropharyngeal cancer. Dysphagia. 2012;27:481–490. doi: 10.1007/s00455-012-9394-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crossley M. Let me explain: Narrative emplotment and one patients’ experience of oral cancer. Social Science and Medicine. 2002;56:439–448. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00362-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimbleby G, Golding LA, Hamarneh O, Ahmad I. Cutting cancer waiting times: Streamlining cervical lymph node biopsy. Journal of Laryngology & Otology. 2013;127(10):1007–1011. doi: 10.1017/S0022215113002004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eades M, Chasen M, Bhargava R. Rehabilitation: Long-term physical and functional changes following treatment. Seminars in Oncology Nursing. 2009;25:222–230. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egestad H. The significance of fellow patients for head and neck cancer patients in the radiation treatment period. European Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2013;17:618–624. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2013.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fakhry C, D’Souza G. Discussing the diagnosis of HPV-OSCC: Common questions and answers. Oral Oncology. 2013;49:863–871. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2013.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Festinger L. A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations. 1954;7:117–40. [Google Scholar]

- Giorgi A. Sketch of a phenomenological method. In: Giorgi A, editor. Phenomenology and Psychological Research. Pittsburgh, PA: Pittsburgh Duquesne University Press; 1985. pp. 8–22. [Google Scholar]

- Haisfield-Wolfe ME, McGuire DB, Soeken K, Geiger-Brown J, De Forge B, Suntharalingam M. Prevalence and correlates of symptoms and uncertainty in illness among head and neck cancer patients receiving definitive radiation with or without chemotherapy. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2012;20:1885–1893. doi: 10.1007/s00520-011-1291-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland J. Psychological aspects of oncology. Medical Clinics of North America. 1977;61:737–748. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(16)31293-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland J, Watson M, Dunn J. The IPOS new International Standard of Quality Cancer Care: integrating the psychosocial domain into routine care. Psycho-Oncology. 2011;20:677–80. doi: 10.1002/pon.1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell D. Reaching to the depths of the soul: Understanding and exploring meaning in illness. Canadian Oncology Nursing Journal. 1998;8:12–16. 22–23. doi: 10.5737/1181912x811216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irvin SK. Waiting: Concept analysis. Nursing Diagnosis. 2001;12:128–136. [Google Scholar]

- Lang H, France E, Williams B, Humphries G, Wells M. The psychological experience of living with head and neck cancer: A systematic review and meta-synthesis. Psycho-Oncology. 2013;22:2648–2663. doi: 10.1002/pon.3343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson M, Hedelin B, Athlin E. Needing a hand to hold: Lived experiences during the trajectory of care for patients with head and neck cancer treated with radiotherapy. Cancer Nursing. 2007;30:324–334. doi: 10.1097/01.NCC.0000281722.56996.07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, Appraisal and Coping. New York: Springer Publishing Co; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Lee V. The existential plight of cancer: meaning making as a concrete approach to the intangible search for meaning. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2008;16:779–785. doi: 10.1007/s00520-007-0396-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQuestion M, Fitch M, Howell D. The changed meaning of food: Physical, social and emotional loss for patients having received radiation treatment for head and neck cancer. European Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2011;15:145–151. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2010.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishel MH. Reconceptualization of the Uncertainty in Illness Theory. Image: Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2000;22:256–262. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.1990.tb00225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molassiotis A, Rogers M. Symptom experience and regaining normality in the first year following a diagnosis of head and neck cancer. A qualitative longitudinal study. Palliative & Supportive Care. 2012;10:197–204. doi: 10.1017/S147895151200020X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morse JM. Emerging from the data: The cognitive process of analysis in qualitative inquiry. In: Morse JM, editor. Critical issues in qualitative research methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Morse JM. Editorial: The significance of standards. Qualitative Health Research. 2003;13:1187–1188. doi: 10.1177/1049732303257231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nail LM. I’m coping as fast as I can: Psychosocial adjustment to cancer and cancer treatment. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2001;28:967–970. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ness S, Kokal J, Fee-Schroeder K, Novotny P, Satele D, Barton D. Concerns across the survivorship trajectory: Results from a survey of cancer survivors. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2013;40:35–42. doi: 10.1188/13.ONF.35-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nund RL, Ward EC, Scarinci NA, Cartmill B, Kuipers P, Porceddu SV. The lived experience of dysphagia following non-surgical treatment for head and neck cancer. International Journal of Speech Language Pathology. 2014;16:282–289. doi: 10.3109/17549507.2013.861869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penner J. Psychosocial care of patients with head and neck cancer. Seminars in Oncology Nursing. 2009;25:231–241. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2009.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ringash J. Survivorship and quality of life in head and neck cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2015;33:1–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.61.4115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roussi P, Miller SM. Monitoring style of coping with cancer related threats: A review of the literature. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2014;37:931–954. doi: 10.1007/s10865-014-9553-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M. The problem of rigour in qualitative research. Advances in Nursing Science. 1986;8:27–37. doi: 10.1097/00012272-198604000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M. Rigour or rigour mortis: The problem of rigour in qualitative research revisited. Advances in Nursing Science. 1993;16:1–8. doi: 10.1097/00012272-199312000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M. Focus on qualitative methods. Sample size in qualitative research. Research in Nursing & Health. 1995;18:179–183. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770180211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M. Focus on research methods: Whatever happened to qualitative description? Research in Nursing & Health. 2000;23:334–340. doi: 10.1002/1098-240x(200008)23:4<334::aid-nur9>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streubert HJ, Carpenter DR, editors. Qualitative Research in Nursing: Advancing the Humanistic Imperative. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki M. Quality of life, uncertainty, and perceived involvement in decision making in patients with head and neck cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2012;39:541–548. doi: 10.1188/12.ONF.541-548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorne S. Focus on Qualitative Methods. Interpretive description: A non-categorical qualitative alternative for developing nursing knowledge. Research in Nursing & Health. 1997;20:169–177. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-240x(199704)20:2<169::aid-nur9>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorne S. Interpretive Description. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press, Inc; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Thorne S, Reimer Kirham S, O’Flynn-Magee K. The analytic challenge in interpretive description. International Journal of Qualitative Methods. 2004;3:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- van Harten MC, Hoebers FJ, Kross KW, van Werkhoven ED, van den Brekel MW, van Dijk BA. Determinants of treatment waiting times for head and neck cancer in the Netherlands and their relation to survival. Oral Oncology. 2015;51:272–278. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2014.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells M. The hidden experience of radiotherapy to the head and neck: A qualitative study of patients after completion of treatment. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1998;28:840–848. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1998x.00714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells M, Swartzman S, Lang H, Cunningham M, Taylor L, Thomson J, Philp J, McCowan C. Predictors of quality of life in head and neck cancer survivors up to 5 years after end of treatment: A cross-sectional survey. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2015;24(6):2463–72. doi: 10.1007/s00520-015-3045-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]