Abstract

Objective

To determine if people receiving opioid agonist treatment (OAT), a long-term treatment approach, are also receiving high-quality primary care.

Design

Retrospective cohort study.

Setting

Ontario.

Participants

Recipients of public drug benefits who had at least 6 months of continuous use of methadone or buprenorphine between October 1, 2012, and September 30, 2013.

Main outcome measures

Rates of cancer screening and diabetes monitoring among those who had at least 6 months of continuous OAT were compared with matched controls. Conditional logistic regression models were used to assess differences after adjusting for confounders. In secondary analyses, outcomes by type of OAT and factors related to health care delivery were compared.

Results

A cohort of 20 406 OAT patients was identified; they had a mean (SD) of 31 (15) physician clinic visits during the 6-month study period. Compared with the control group, OAT patients were less likely to receive screening for cervical cancer (48.7% vs 62.6%; adjusted odds ratio [AOR] of 0.34, 95% CI 0.31 to 0.36), breast cancer (23.3% vs 49.1%; AOR = 0.19, 95% CI 0.16 to 0.24), and colorectal cancer (32.5% vs 49.0%; AOR = 0.34, 95% CI 0.30 to 0.38), and less likely to have monitoring for diabetes (11.7% vs 28.5%; AOR = 0.16, 95% CI 0.13 to 0.21). Patients receiving OAT who were taking buprenorphine, enrolled in a medical home, or seeing a low-volume prescriber were generally more likely to receive cancer screening and diabetes monitoring.

Conclusion

Patients receiving OAT were less likely to receive chronic disease prevention and management than matched controls were despite frequent health care visits, indicating a gap in equitable access to primary care.

Résumé

Objectif

Déterminer si les patients qui sont traités à long terme avec des agonistes des opiacés (AO) profitent aussi de soins primaires de qualité.

Type d’étude

Une étude de cohorte rétrospective.

Contexte

L’Ontario.

Participants

Des patients bénéficiaires d’un régime public d’assurance médicaments qui ont utilisé de la méthadone ou de la buprénorphine entre le 1er octobre 2012 et le 30 septembre 2013.

Principaux paramètres à l’étude

On a comparé les taux de dépistage du cancer et celui de la surveillance du diabète chez les patients qui avaient pris des AO de façon continue pendant au moins 6 mois à ceux de témoins appariés. On s’est servi de modèles de régression logistique conditionnelle pour vérifier les différences après un ajustement pour les variables confondantes. Dans une analyse secondaire, on a comparé les issues selon la nature de l’AO utilisé et les facteurs relatifs aux soins de santé prodigués.

Résultats

On a utilisé une cohorte de 20 406 patients recevant des AO; Ils avaient visité en moyenne 31 (DS = 15) cliniques médicales au cours des 6 mois de l’étude. Par rapport aux témoins, les patients traités aux AO étaient moins susceptibles d’avoir fait l’objet d’un dépistage pour le cancer du col (48,7 % c. 62,6 %; rapport de cotes ajusté [RCA] = 0,34, IC à 95 % 0,31 à 0,36), pour le cancer du sein (23,3 % c. 49,1 %; RCA = 0,19, IC à 95 % 0,16 à 0,24) et pour le cancer colorectal (32,5 % c. 49,0 %; RCA = 0,34, IC à 95 % 0,30 à 0,38), en plus d’être moins susceptibles d’avoir fait l’objet d’une surveillance du diabète (11,7 % c. 28,5 %; RCA = 0,16, IC à 95 % 0,13 à 0,21). Les patients qui prenaient de la buprénorphine comme traitement, qui étaient inscrits dans un centre de médecine familiale ou qui étaient suivis par un médecin prescrivant peu de médicaments étaient généralement plus susceptibles d’avoir bénéficié d’un dépistage pour le cancer ou d’une surveillance du diabète.

Conclusion

Par rapport à ceux du groupe témoin, les patients qui prenaient des AO étaient moins susceptibles de faire l’objet d’une prévention des maladies chroniques et d’une prise en charge que ne l’étaient les témoins appariés, malgré de fréquentes visites en soins de santé, ce qui indique un accès inéquitable aux soins primaires.

Opioid use disorder currently affects 15.5 million people worldwide.1 Rates have soared in Canada and the United States (US) as a result of an increase in opioid prescribing for chronic noncancer pain.2–4 Opioid agonist treatment (OAT) with methadone or buprenorphine is the first-line treatment for those with opioid use disorder.5,6 Opioid agonist treatment leads to increased retention in treatment programs and a reduction in use of illicit substances compared with psychosocial treatment alone.7,8 Opioid agonist treatment is also associated with reductions in risky behaviour, criminal activity, and mortality,9,10 and an improvement in health and social function.11 The number of people accessing OAT has more than doubled in the past decade and is likely to continue to expand.2,4,12

Patients receiving OAT have frequent interactions with the health care system. In Canada and the US, regulators require that providers see patients prescribed methadone at least weekly for monitoring and urine drug testing.13–16 Once patients are more stable (ie, no longer using addictive substances and attending treatment regularly for several months), regulators permit a gradual reduction in visit and urine drug test frequency. Even very stable patients, however, are required to have a visit and urine drug test at least every 1 to 3 months depending on the jurisdiction. In the US and in most Canadian jurisdictions, buprenorphine is subject to fewer regulations because of the lower risk of overdose death.17 Most guidelines still recommend weekly visits initially with a gradual reduction in frequency as patients achieve stability.18,19

Despite these frequent health care interactions, it is unclear if patients receiving OAT are accessing high-quality primary care. Opioid agonist treatment is a long-term treatment approach,11 and the population receiving OAT will have an increasing need for chronic disease prevention and management as they get older and their numbers increase.20–22 Many patients receiving OAT, however, attend specialized OAT clinics and it is unclear whether these clinics integrate or provide access to primary care.23–27 To date, there is little literature measuring the quality of primary care, particularly chronic disease prevention and management, for the OAT population.

Our study objective was to understand whether patients receiving OAT were receiving recommended screening for cervical, breast, and colorectal cancer, and evidence-based testing for diabetes. We sought to compare these quality-of-care measures between patients receiving OAT and patients not receiving OAT. We also sought to determine the effects of factors related to OAT prescribing and health care delivery on these rates.

METHODS

Design

We conducted a retrospective, population-based cohort study of recipients of public drug benefits in Ontario who received methadone or buprenorphine continuously for at least 6 months between October 1, 2012, and September 30, 2013. The Research Ethics Board of Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre in Toronto, Ont, approved this study.

Setting

Ontario had a population of 13.4 million in 2012.28 Ontarians have publicly funded coverage for all essential clinic and emergency department visits, medical procedures, hospitalizations, and laboratory testing through the Ontario Health Insurance Plan. The publicly funded Ontario Drug Benefit program provides prescription drug coverage based on age (65 years and older), receipt of social assistance, high prescription drug costs relative to net household income, receipt of disability benefits, residence in a long-term care facility, and receipt of home care.

Most Ontarians receive primary care services from a physician practising in a medical home.29 Medical homes were introduced in Ontario in 2002, and involve a blend of fee-for-service and capitation payments, formal patient enrolment, and incentives to provide chronic disease prevention and monitoring. Approximately 18% of patients attend medical homes that receive funding to pay for nonphysician health professionals.29

Data sources

To identify recipients of public drug benefits, we used the Ontario Drug Benefit claims database. We determined patient demographic characteristics using the Registered Persons Database, which captures vital statistics for all residents of Ontario who have ever received a health card. We determined enrolment in a medical home using the Client Agency Program Enrolment data set. We used the Statistics Canada Postal Code Conversion File to determine neighbourhood income quintile and rurality.30 We used the Ontario Health Insurance Plan database to determine laboratory, physician, and optometrist services used, and validated databases to determine diagnoses of congestive heart failure,31 asthma,32 hypertension,33 acute myocardial infarction,34 diabetes,35 and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.36 Finally, we used the Ontario Cancer Registry to determine cancer diagnosis information and the Ontario Breast Screening Program database to identify breast cancer screening. We linked and analyzed the data sets using unique, encoded identifiers at ICES in Toronto, Ont.

Sample frame and selection of participants

We defined the OAT cohort as recipients of public drug benefits who had at least 6 months of continuous use of methadone or buprenorphine during our study period. Because methadone prescription duration is not captured in the database, we defined continuous use of methadone as the receipt of a subsequent prescription within 30 days of the previous prescription (30 days is the maximum prescription length that regulators typically recommend).15,16 As buprenorphine prescription duration is captured, we defined continuous use of buprenorphine on the basis of receipt of a subsequent prescription within 1.5 times the day’s supply of the previous prescription. To be consistent with our methadone definition, we applied a window of 30 days to follow forward for a subsequent buprenorphine prescription. For the descriptive analysis, we matched each individual in the OAT cohort with up to 10 age- and sex-matched controls from the population of recipients of public drug benefits. For our analyses of receipt of cancer screening and diabetes monitoring, we identified subsets of the OAT cohort who were eligible for each screening or monitoring outcome and randomly selected up to 10 age- and sex-matched controls receiving public drug benefits who were similarly eligible. In our sensitivity analyses, we used consistent methods to match the OAT group to controls sourced from the general population in Ontario. In all analyses, the index date for the OAT cohort was defined as 180 days following their first OAT prescription in our study period to ensure that each person had been receiving OAT for at least 6 months, and screening outcomes were defined using differential look-back windows specific to the outcome. The index date for controls was defined as March 31, 2013.

Outcome definition

We studied 4 key screening and monitoring outcomes as indicators of chronic disease prevention and management: cervical cancer screening (in the past 3 years), breast cancer screening (in the past 2 years), colorectal cancer screening (in the past 10 years), and optimal diabetes monitoring (in the past 2 years). For each outcome, we determined patient eligibility at the index date, the look-back window, and optimal screening and monitoring practice using guidelines from Cancer Care Ontario and the Canadian Diabetes Association (Table 1).37,38

Table 1.

Eligibility and optimal screening and monitoring definitions for study outcomes

| OUTCOME | ELIGIBILITY* AND EXCLUSIONS† | OPTIMAL SCREENING OR MONITORING DEFINITION‡ |

|---|---|---|

| Cervical cancer screening | Women aged 21 to 69 y, excluding those with hysterectomy or previous gynecologic cancer | Papanicolaou test in the past 3 y |

| Breast cancer screening | Women aged 50 to 74 y, excluding those with breast cancer or a mastectomy | Mammogram in the past 2 y |

| Colorectal cancer screening | Adults aged 50 to 74 y, excluding those with inflammatory bowel disease or with colorectal and anal cancer | Fecal occult blood test in the past 2 y, or barium enema or sigmoidoscopy in the past 5 y or colonoscopy in the past 10 y |

| Optimal diabetes monitoring | Diagnosis of diabetes | Retinal eye examination in the past 2 y, cholesterol test in the past 2 y, and hemoglobin A1c test in the past 6 mo |

We determined eligibility using clinical practice guidelines from Cancer Care Ontario37 and the Canadian Diabetes Association.38

We used physician billing data and information from the Ontario Cancer Registry to help determine which adults should be excluded from screening calculations.

We determined cancer screening using physician and laboratory billing data as well as data from the Ontario Breast Screening Program. We obtained data on hemoglobin A1c and cholesterol testing from laboratory claims and determined eye examination rates using physician and optometrist service claims.

Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to compare basic demographic and clinical characteristics between the cohort and the matched controls. We used standardized differences as a measure of clinically meaningful differences between groups. Generally a standardized difference greater than 0.10 is considered to be suggestive of a meaningful difference.39

In our primary analysis, we compared crude cancer screening and diabetes monitoring rates between OAT patients meeting screening eligibility criteria and matched controls. We then created multivariable conditional logistic regression models to explore whether differences remained after accounting for potential confounders. We selected confounders based on the medical literature, clinical expertise, and standardized differences of greater than 0.10 between groups in the descriptive analysis. In our sensitivity analysis, we compared rates between OAT patients and matched controls from the general population in Ontario.

In our secondary analyses, we explored the effects of several prespecified covariates on our outcome rates among OAT patients. These covariates included the type of OAT, OAT physician prescribing volume, and enrolment in a medical home. We defined physician prescribing volume based on the total days supplied for OAT during the study period for all recipients of public drug benefits in a physician’s OAT practice. We defined low-volume prescribers as those responsible for the lower 90% of prescriptions and high-volume prescribers as for those responsible for the top 10% of prescriptions. Patients were then assigned to the physician who prescribed most of their OAT during their 6 months of continuous use. We categorized enrolment in a medical home as patients not enrolled in a medical home, those enrolled in a team-based (ie, family health team) medical home, and those enrolled in a non–team-based medical home (ie, family health groups, the comprehensive care model, family health networks, and non–family health team family health organizations). We included each of these variables in a multivariable logistic regression model to determine their independent effect on screening and monitoring rates.

RESULTS

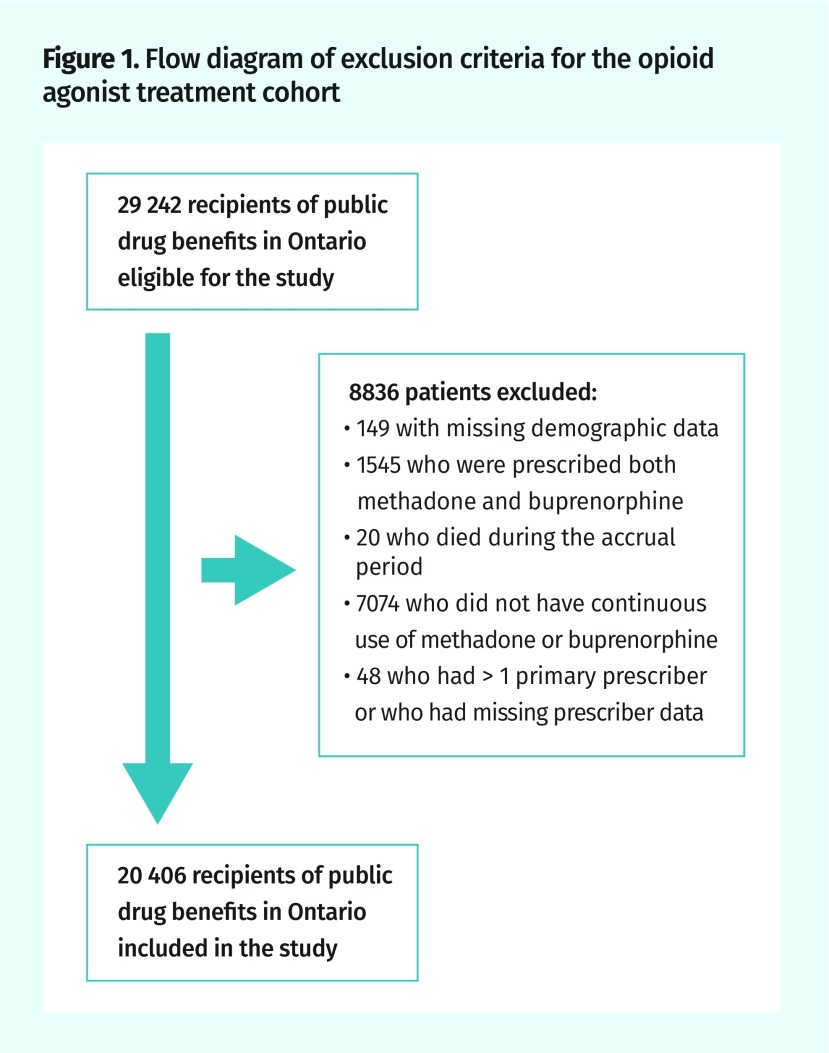

After exclusions, we identified a cohort of 20 406 OAT patients who met our eligibility criteria (Figure 1). They were age- and sex-matched to 201 822 controls (Table 2). Among the OAT cohort, 94.9% received methadone and 5.1% received buprenorphine. The OAT patients lived predominantly in urban areas and resided in neighbourhoods in the lowest income quintile. They were less likely to be enrolled in a medical home. During the 6-month study period, patients in the OAT cohort had a mean (SD) of 31 (15) physician visits compared with only 5 (6) visits among controls.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of exclusion criteria for the opioid agonist treatment cohort

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of the OAT cohort and their age- and sex-matched controls

| VARIABLE |

OAT COHORT, N = 20 406 |

AGE- AND SEX-MATCHED CONTROLS, N = 201 822 |

STANDARDIZED DIFFERENCE* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median (IQR) age, y | 36 (29–47) | 37 (29–47) | 0.01 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 11 674 (57.2) | 114 497 (56.7) | 0.01 |

| Urban residence, n (%) | 18 191 (89.1) | 179 986 (89.2) | 0.00 |

| Income quintile, n (%) | |||

| • 1 (lowest income) | 8804 (43.1) | 78 969 (39.1) | 0.08 |

| • 2 | 4728 (23.2) | 45 267 (22.4) | 0.02 |

| • 3 | 3032 (14.9) | 32 682 (16.2) | 0.04 |

| • 4 | 2218 (10.9) | 25 547 (12.7) | 0.06 |

| • 5 (highest income) | 1502 (7.4) | 18 365 (9.1) | 0.06 |

| • Missing | 122 (0.6) | 992 (0.5) | 0.01 |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | |||

| • Diabetes | 1407 (6.9) | 29 417 (14.6) | 0.25 |

| • Congestive heart failure | 169 (0.8) | 2349 (1.2) | 0.03 |

| • Asthma | 4979 (24.4) | 44 585 (22.1) | 0.05 |

| • Acute myocardial infarction | 169 (0.8) | 2646 (1.3) | 0.05 |

| • Hypertension | 2526 (12.4) | 39 265 (19.5) | 0.19 |

| • COPD | 2410 (11.8) | 15 266 (7.6) | 0.14 |

| • Psychotic disorders | 1401 (6.9) | 24 450 (12.1) | 0.18 |

| Received methadone, n (%) | 19 367 (94.9) | NA | NA |

| Treated by a high-volume OAT prescriber, n (%) | 15 979 (78.3) | NA | NA |

| Enrolled in a medical home, n (%) | 8948 (43.8) | 147 759 (73.2) | 0.62 |

| Mean (SD) no. of physician visits in 6-mo study period | 31 (15) | 5 (6) | 2.36 |

COPD—chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, IQR—interquartile range, NA—not applicable, OAT—opioid agonist treatment.

A standardized difference > 0.10 is considered to be suggestive of a meaningful difference.

In our primary analysis (Tables 3 and 4) we found that, compared with age- and sex-matched controls, the OAT cohort was less likely to receive screening for cervical cancer (48.7% vs 62.6%), breast cancer (23.3% vs 49.1%), and colorectal cancer (32.5% vs 49.0%), and less likely to have optimal monitoring for diabetes (11.7% vs 28.5%). We found consistent results in a sensitivity analysis (Tables 3 and 4) that compared OAT patients with matched controls from the general population.

Table 3.

Crude rates of cancer screening and diabetes monitoring for the OAT cohort and age- and sex-matched controls

| SCREENING OR MONITORING | OAT COHORT | AGE- AND SEX-MATCHED CONTROLS |

SENSITIVITY ANALYSIS: AGE- AND SEX-MATCHED GENERAL POPULATION CONTROLS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cervical cancer screening | |||

| • Eligible, n | 7823 | 78 230 | 78 230 |

| • Screened, n (%) | 3812 (48.7) | 49011 (62.6)* | 50 332 (64.3)* |

| Breast cancer screening | |||

| • Eligible, n | 1185 | 11 850 | 11 850 |

| • Screened, n (%) | 276 (23.3) | 5820 (49.1)* | 6483 (54.7)* |

| Colorectal cancer screening | |||

| • Eligible, n | 3644 | 36 440 | 36 440 |

| • Screened, n (%) | 1184 (32.5) | 17847 (49.0)* | 18 161 (49.8)* |

| Optimal diabetes monitoring | |||

| • Eligible, n | 1407 | 14 070 | 14 070 |

| • Screened, n (%) | 164 (11.7) | 4015 (28.5)* | 3286 (23.4)* |

OAT—opioid agonist treatment.

Indicates standardized difference > 0.10 compared with the OAT cohort.

Table 4.

Odds of individuals in the OAT cohort receiving cancer screening and diabetes monitoring compared with age- and sex-matched controls (recipients of public drug benefits) and general population age- and sex-matched controls, after adjustment for potential confounders

| SCREENING OR MONITORING | PRIMARY ANALYSIS*: OAT COHORT VS AGE- AND SEX-MATCHED CONTROLS, OR (95% CI) | SENSITIVITY ANALYSIS†: OAT COHORT VS AGE- AND SEX-MATCHED GENERAL POPULATION CONTROLS, OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Cervical cancer screening | 0.34 (0.31–0.36) | 0.20 (0.18–0.23) |

| Breast cancer screening | 0.19 (0.16–0.24) | 0.13 (0.10–0.18) |

| Colorectal cancer screening | 0.34 (0.30–0.38) | 0.25 (0.22–0.29) |

| Optimal diabetes monitoring | 0.16 (0.13–0.21) | 0.11 (0.09–0.15) |

COPD—chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, OAT—opioid agonist treatment, OR—odds ratio.

Adjusted for income quintile, presence of a psychotic disorder, COPD, diabetes, hypertension, enrolment in a medical home, and physician clinic visits.

Adjusted for income quintile, presence of a psychotic disorder, COPD, asthma, enrolment in a medical home, and physician clinic visits.

In our secondary analyses (Table 5) among the OAT cohort, those who received buprenorphine were more likely to receive screening for cervical cancer and colorectal cancer and optimal monitoring for diabetes compared with those treated with methadone. Patients enrolled in team-based and non–team-based medical homes were more likely to receive cervical cancer screening and colorectal cancer screening than those not enrolled. Those cared for by a high-volume OAT prescriber were less likely to receive breast cancer screening, and colorectal cancer screening than those seeing a low-volume prescriber.

Table 5.

Crude rates and odds of cancer screening and diabetes monitoring for the OAT cohort stratified by type of OAT, enrolment in a medical home, and physician prescribing volume

| SCREENING OR MONITORING | TYPE OF OAT | ENROLMENT IN MEDICAL HOME | PHYSICIAN PRESCRIBING VOLUME | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| METHADONE | BUPRENORPHINE | NOT ENROLLED | ENROLLED IN NON–TEAM-BASED HOME | ENROLLED IN TEAM-BASED HOME | LOW | HIGH | |

| Cervical cancer screening | |||||||

| • Eligible, n | 7398 | 425 | 4215 | 2577 | 1031 | 1619 | 6204 |

| • Screened, n (%) | 3552 (48.0)* | 260 (61.2) | 1924 (45.6) | 1302 (50.5)* | 586 (56.8)* | 824 (50.9) | 2988 (48.2) |

| • Adjusted OR (95% CI)† | Reference | 1.67 (1.35–2.07) | Reference | 1.19 (1.08–1.32) | 1.48 (1.29–1.71) | Reference | 0.85 (0.76–0.96) |

| Breast cancer screening | |||||||

| • Eligible, n | 1095 | 90 | 638 | 410 | 137 | 304 | 881 |

| • Screened, n (%) | 249 (22.7)* | 27 (30.0) | 144 (22.6) | 93 (22.7) | 39 (28.5)* | 86 (28.3) | 190 (21.6)* |

| • Adjusted OR (95% CI)† | Reference | 1.04 (0.58–1.87) | Reference | 0.95 (0.70–1.29) | 1.30 (0.85–1.99) | Reference | 0.71 (0.52–0.97) |

| Colorectal cancer screening | |||||||

| • Eligible, n | 3413 | 231 | 2013 | 1243 | 388 | 1036 | 2608 |

| • Screened, n (%) | 1069 (31.3)* | 115 (49.8) | 563 (28.0) | 456 (36.7)* | 165 (42.5)* | 371 (35.8) | 813 (31.2)* |

| • Adjusted OR (95% CI)† | Reference | 1.84 (1.35–2.49) | Reference | 1.38 (1.19–1.62) | 1.74 (1.38–2.19) | Reference | 0.84 (0.71–0.98) |

| Optimal diabetes monitoring | |||||||

| • Eligible, n | 1332 | 75 | 713 | 527 | 164 | 371 | 1036 |

| • Monitored, n (%) | 148 (11.1)* | 16 (21.3) | 71 (10.0) | 70 (13.3)* | 23 (14.0)* | 41 (11.1) | 123 (11.9) |

| • Adjusted OR (95% CI)† | Reference | 2.20 (1.15–4.19) | Reference | 1.39 (0.97–2.00) | 1.46 (0.87–2.45) | Reference | 1.21 (0.82–1.80) |

COPD—chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, OAT—opioid agonist treatment, OR—odds ratio.

Indicates standardized difference > 0.10 compared with the reference group.

Adjusted for age, sex (where appropriate), income quintile, presence of a psychotic disorder, COPD, physician clinic visits, type of OAT, enrolment in a medical home, volume of prescriber’s practice, and new-OAT-user status.

DISCUSSION

In this large population-based study of recipients of public drug benefits, we found that individuals who received OAT were less likely to receive cancer screening and optimal diabetes monitoring compared with matched controls. Of importance, the low rates of cancer screening and diabetes monitoring in the OAT cohort occurred despite patients visiting a physician (either the OAT provider or another physician) on average at least once a week. Furthermore, among our OAT cohort, those who received buprenorphine, those enrolled in a medical home (particularly a team-based medical home), and those who saw a low-volume OAT prescriber were generally more likely to receive cancer screening and diabetes monitoring.

Our findings are consistent with the results of 2 American studies that reported poor access to primary care40 and low rates of chronic disease prevention and monitoring41 for patients cared for in specialized OAT clinics. Both of these studies were small and focused on a single setting, whereas our study included all recipients of publicly funded OAT in Canada’s largest province. The explanation for the low rates is likely multifactorial. First, the effects of opioid use disorder itself might impair patients’ ability to access health care.42,43 In addition, the frequent visits to OAT clinics place a high burden of care on patients and might limit their capacity to attend primary care visits.44 Similarly, the lack of integration between primary care and OAT provision might play a substantial role.43,45,46 The American study that reported low rates of chronic disease prevention and monitoring for patients who accessed OAT at specialized clinics supports this hypothesis: the researchers found much higher rates among patients who instead received OAT from their primary care physicians.41 Unfortunately, few patients in Canada and the US receive OAT in a primary care clinic.24–27 A recent American study found that only 3% of primary care physicians had waivers to prescribe buprenorphine.26 A final factor might be the nature of the specialized OAT clinics. Overwhelmingly, they are private, fee-for-service clinics, a model that incentivizes high patient volumes rather than high-quality care.2,24,26 This hypothesis is supported by the lower rates of chronic disease prevention and monitoring found in patients seeing high-volume prescribers in our study.

The reason for higher rates of screening and monitoring among those receiving buprenorphine is unclear. Health care delivery differences might play a role, as buprenorphine is subject to less-stringent monitoring than methadone is.47 Additionally, the higher rates might be the result of underlying patient characteristics, which we were unable to measure, associated with better adherence to screening and monitoring. Patients started on buprenorphine are more likely to have used prescription opioids, not heroin, and have fewer years of opioid dependence.48–52 Therefore, the buprenorphine group in our study might be a less vulnerable population that has fewer difficulties accessing primary care in a fragmented system compared with the methadone group.

We found that enrolment in a medical home, particularly a team-based medical home, was associated with higher rates of cancer screening and diabetes monitoring. Other studies have found that, in the general population, rates of chronic disease prevention and management are higher in team-based medical homes29 and gaps in care are widest for those not enrolled in a medical home.53 Team-based medical homes include social workers, nurses, pharmacists, and dietitians who can help address the complex needs of patients receiving OAT. We found, however, that rates of enrolment in a team-based model, or any medical home, were much lower among OAT patients than in matched controls. Low enrolment might be related to financial incentives, including a capitation formula that compensates physicians based on patient age and sex but not on complexity.54 It is also possible that provider discrimination and patient factors, such as difficulty attending appointments, play a role in access to a medical home.42,43,55

Strengths and limitations

Our study has several strengths, including its large, population-based nature, use of a control group, and our evaluation of several different measures of chronic disease prevention and monitoring. However, our study also has limitations. First, we are unable to capture OAT paid for through private drug plans, out of pocket, or via Canada’s Non-Insured Health Benefits plan for Indigenous people. However, approximately 72% of patients in Ontario receive OAT through the Ontario public drug program, so we anticipate that our findings are highly representative of the broader population of OAT patients.56 Second, we were limited in our assessment of primary care quality measures to those that can be measured in health administrative databases.

Conclusions and future directions

This study demonstrates that OAT patients have low rates of chronic disease prevention and management despite frequent physician clinic visits. This suggests that the current model of delivering OAT in specialized clinics does not meet the comprehensive health care needs of this vulnerable patient population. Our findings that patients who received buprenorphine, those enrolled in a medical home, and those who saw a low-volume prescriber had higher rates of chronic disease prevention and management identifies modifiable practices that could lead to improved quality of care in this population. As the OAT population has frequent interactions with the health care system, models of integrated primary and OAT care might improve access to high-quality primary care.

Acknowledgments

Dr Spithoff was supported by a graduate research award from the Department of Family and Community Medicine at the University of Toronto.

Editor’s key points

▸ This study demonstrates that patients receiving opioid agonist treatment (OAT) have low rates of chronic disease prevention and management despite frequent physician clinic visits. This suggests that the current model of delivering OAT in specialized clinics does not meet the comprehensive health care needs of this vulnerable patient population.

▸ Patients who received buprenorphine, those enrolled in a medical home, and those who saw a low-volume prescriber had higher rates of chronic disease prevention and management; these findings identify modifiable practices that could lead to improved quality of care in this population.

▸ The explanation for the low rates of chronic disease prevention and management is likely multifactorial: effects of opioid use disorder might impair patients’ ability to access health care; the frequent visits to OAT clinics place a high burden of care on patients and might limit their capacity to attend primary care visits; and the lack of integration between primary care and OAT provision might play a substantial role.

Points de repère du rédacteur

▸ Cette étude montre que les patients qui sont traités avec des agonistes des opiacés (AO) font l’objet de peu de prévention et de prise en charge des maladies chroniques, et ce, même s’ils consultent souvent des cliniques médicales. Cela donne à croire que la façon actuelle de prodiguer ce genre de traitement dans les cliniques spécialisées ne répond pas adéquatement aux besoins en santé de ces patients particulièrement vulnérables.

▸ Les patients qui recevaient de la buprénorphine, ceux qui étaient inscrits dans un centre de médecine familiale et ceux qui consultaient un médecin prescrivant moins de médicaments avaient davantage fait l’objet d’une prévention et d’une prise en charge des maladies chroniques; ces constatations ont permis de cerner des pratiques modifiables susceptibles d’améliorer la qualité des soins à ces patients.

▸ Les faibles taux de prévention et de prise en charge des maladies chroniques sont probablement multifactoriels : les effets de la dépendance aux opiacés pourraient réduire la capacité des patients à accéder aux soins de santé; les visites fréquentes aux cliniques où ils reçoivent les AO leur imposent beaucoup de démarches susceptibles de limiter leur capacité à se rendre aux rendez-vous en soins primaires; et le manque d’intégration entre les soins primaires et le traitement aux AO pourrait jouer un rôle considérable.

Footnotes

Contributors

All authors contributed to the concept and design of the study; data gathering, analysis, and interpretation; and preparing the manuscript for submission.

Competing interests

None declared

This article has been peer reviewed.

Cet article a fait l’objet d’une révision par des pairs.

References

- 1.Degenhardt L, Charlson F, Mathers B, Hall WD, Flaxman AD, Johns N, et al. The global epidemiology and burden of opioid dependence: results from the global burden of disease 2010 study. Addiction. 2014;109(8):1320–33. doi: 10.1111/add.12551. Epub 2014 Apr 24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fischer B, Kurdyak P, Goldner E, Tyndall M, Rehm J. Treatment of prescription opioid disorders in Canada: looking at the ‘other epidemic’? Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2016;11:12. doi: 10.1186/s13011-016-0055-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nelson LS, Juurlink DN, Perrone J. Addressing the opioid epidemic. JAMA. 2015;314(14):1453–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.12397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality . Treatment episode data set (TEDS) 2003–2013. National admissions to substance abuse treatment services. Rockville, MD: Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dunlap B, Cifu AS. Clinical management of opioid use disorder. JAMA. 2016;316(3):338–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.9795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Volkow ND, Frieden TR, Hyde PS, Cha SS. Medication-assisted therapies—tackling the opioid-overdose epidemic. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(22):2063–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1402780. Epub 2014 Apr 23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mattick RP, Breen C, Kimber J, Davoli M. Methadone maintenance therapy versus no opioid replacement therapy for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(3):CD002209. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002209.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mattick RP, Breen C, Kimber J, Davoli M. Buprenorphine maintenance versus placebo or methadone maintenance for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(2):CD002207. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002207.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marsch LA. The efficacy of methadone maintenance interventions in reducing illicit opiate use, HIV risk behavior and criminality: a meta-analysis. Addiction. 1998;93(4):515–32. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.9345157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sordo L, Barrio G, Bravo MJ, Indave BI, Degenhardt L, Wiessing L, et al. Mortality risk during and after opioid substitution treatment: systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMJ. 2017;357:j1550. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j1550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garcia-Portilla MP, Bobes-Bascaran MT, Bascaran MT, Saiz PA, Bobes J. Long term outcomes of pharmacological treatments for opioid dependence: does methadone still lead the pack? Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;77(2):272–84. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rotondi NK, Rush B. Monitoring utilization of a large scale addiction treatment system: the Drug and Alcohol Treatment Information System (DATIS). Subst Abuse. 2012;6:73–84. doi: 10.4137/SART.S9617. Epub 2012 Jun 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.College of Pharmacists of Manitoba. Manitoba methadone and buprenorphine maintenance: recommended practice. Winnipeg, MB: College of Pharmacists of Manitoba; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 14.British Columbia Centre on Substance Use. British Columbia Ministry of Health . A guideline for the clinical management of opioid use disorder. Vancouver, BC: British Columbia Centre on Substance Use; 2017. Available from: www.bccsu.ca/care-guidance-publications. Accessed 2019 Mar 28. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . Federal guidelines for opioid treatment programs. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2015. Available from: http://cdn.atforum.com/wp-content/uploads/SAMHSA-2015-Guidelines-for-OTPs.pdf. Accessed 2019 Mar 28. [Google Scholar]

- 16.College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario . Methadone maintenance treatment program standards and clinical guidelines. 4th ed. Toronto, ON: College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bell JR, Butler B, Lawrance A, Batey R, Salmelainen P. Comparing overdose mortality associated with methadone and buprenorphine treatment. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;104(1–2):73–7. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.03.020. Epub 2009 May 13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Handford C, Kahan M, Srivastava A, Cirone S, Sanghera S, Palda V, et al. Buprenorphine/naloxone for opioid dependence: clinical practice guideline. Toronto, ON: Centre for Addiction and Mental Health; 2011. Available from: www.cpso.on.ca/uploadedFiles/policies/guidelines/office/buprenorphine_naloxone_gdlns2011.pdf. Accessed 2019 Mar 28. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Center for Substance Abuse Treatment . Clinical guidelines for the use of buprenorphine in the treatment of opioid addiction. Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) 40. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reece AS, Hulse GK. Lifetime opiate exposure as an independent and interactive cardiovascular risk factor in males: a cross-sectional clinical study. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2013;9:551–61. doi: 10.2147/VHRM.S48030. Epub 2013 Oct 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosen D, Smith ML, Reynolds CF., 3rd The prevalence of mental and physical health disorders among older methadone patients. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;16(6):488–97. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e31816ff35a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peles E, Schreiber S, Adelson M. 15-Year survival and retention of patients in a general hospital-affiliated methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) center in Israel. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;107(2–3):141–8. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.09.013. Epub 2009 Nov 14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wickersham ME, Basey S. The “regulatory fog” of opioid treatment. J Public Manage Soc Policy. 2016;22(3):6. Available from: http://digitalscholarship.tsu.edu/cgi/vviewcontent.cgi?article=1034&context=jpmsp. Accessed 2019 Mar 28. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luce J, Strike C. A cross-Canada scan of methadone maintenance treatment policy developments. A report prepared for the Canadian Executive Council on Addictions. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Executive Council on Addictions; 2011. Available from: www.ceca-cect.ca/pdf/CECA%20MMT%20Policy%20Scan%20April%202011.pdf. Accessed 2019 Mar 28. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bachhuber MA, Southern WN, Cunningham CO. Profiting and providing less care: comprehensive services at for-profit, nonprofit, and public opioid treatment programs in the United States. Med Care. 2014;52(5):428–34. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stein BD, Gordon AJ, Dick AW, Burns RM, Pacula RL, Farmer CM, et al. Supply of buprenorphine waivered physicians: the influence of state policies. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2015;48(1):104–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2014.07.010. Epub 2014 Aug 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosenblatt RA, Andrilla CH, Catlin M, Larson EH. Geographic and specialty distribution of US physicians trained to treat opioid use disorder. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13(1):23–6. doi: 10.1370/afm.1735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Statistics Canada . Population by year, by province and territory (number). Ottawa, ON: Government of Canada; 2016. Available from: www.statcan.gc.ca/tables-tableaux/sum-som/l01/cst01/demo02a-eng.htm. Accessed 2017 Jan 4. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kiran T, Kopp A, Moineddin R, Glazier RH. Longitudinal evaluation of physician payment reform and team-based care for chronic disease management and prevention. CMAJ. 2015;187(17):E494–502. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.150579. Epub 2015 Sep 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kralj B. Measuring “rurality” for purposes of healthcare planning: an empirical measure for Ontario. Ontario Med Rev. 2000;67:33–52. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schultz SE, Rothwell DM, Chen Z, Tu K. Identifying cases of congestive heart failure from administrative data: a validation study using primary care patient records. Chronic Dis Inj Can. 2013;33(3) Available from: www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/publicat/hpcdp-pspmc/33-3/ar-06-eng.php. Accessed 2017 Jan 4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gershon AS, Wang C, Guan J, Vasilevska-Ristovska J, Cicutto L, To T. Identifying patients with physician-diagnosed asthma in health administrative databases. Can Respir J. 2009;16(6):183–8. doi: 10.1155/2009/963098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tu K, Chen Z, Lipscombe LL, Canadian Hypertension Education Program Outcomes Research Taskforce Prevalence and incidence of hypertension from 1995 to 2005: a population-based study. CMAJ. 2008;178(11):1429–35. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.071283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Austin PC, Daly PA, Tu JV. A multicenter study of the coding accuracy of hospital discharge administrative data for patients in admitted to cardiac care units in Ontario. Am Heart J. 2002;144(2):290–6. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2002.123839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hux JE, Ivis F, Flintoft V, Bica A. Diabetes in Ontario: determination of prevalence and incidence using a validated administrative data algorithm. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(3):512–6. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.3.512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gershon AS, Wang C, Guan J, Vasilevska-Ristovska J, Cicutto L, To T. Identifying individuals with physician diagnosed COPD in health administrative databases. COPD. 2009;6(5):388–94. doi: 10.1080/15412550903140865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cancer Care Ontario. Guidelines and advice. Toronto, ON: Cancer Care Ontario; Available from: www.cancercareontario.ca/en/guidelines-advice. Accessed 2019 Mar 28. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Canadian Diabetes Association Clinical Practice Guidelines Expert Committee. Cheng AYY. Canadian Diabetes Association 2013 clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and management of diabetes in Canada. Introduction. Can J Diabetes. 2013;37(Suppl 1):S1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjd.2013.01.009. Epub 2013 Mar 26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mamdani M, Sykora K, Li P, Normand SL, Streiner DL, Austin PC, et al. Reader’s guide to critical appraisal of cohort studies: 2. Assessing potential for confounding. BMJ. 2005;330(7497):960–2. doi: 10.1136/bmj.330.7497.960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rajaratnam R, Sivesind D, Todman M, Roane D, Seewald R. The aging methadone maintenance patient: treatment adjustment, long-term success, and quality of life. J Opioid Manag. 2009;5(1):27–37. doi: 10.5055/jom.2009.0004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Haddad MS, Zelenev A, Altice FL. Buprenorphine maintenance treatment retention improves nationally recommended preventive primary care screenings when integrated into urban federally qualified health centers. J Urban Health. 2015;92(1):193–213. doi: 10.1007/s11524-014-9924-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Palepu A, Gadermann A, Hubley AM, Farrell S, Gogosis E, Aubry T, et al. Substance use and access to health care and addiction treatment among homeless and vulnerably housed persons in three Canadian cities. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e75133. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ross LE, Vigod S, Wishart J, Waese M, Spence JD, Oliver J, et al. Barriers and facilitators to primary care for people with mental health and/or substance use issues: a qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract. 2015;16:135. doi: 10.1186/s12875-015-0353-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Boehmer KR, Shippee ND, Beebe TJ, Montori VM. Pursuing minimally disruptive medicine: disruption from illness and health care-related demands is correlated with patient capacity. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;74:227–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.01.006. Epub 2016 Jan 11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Druss BG. Improving medical care for persons with serious mental illness: challenges and solutions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(Suppl 4):40–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and Health Resources and Services Administration Centre for Integrated Health Solutions. Innovations in addictions treatment. Addiction treatment providers working with integrated primary care services. Washington, DC: National Council for Community Behavioral Healthcare; 2013. Available from: www.integration.samhsa.gov/clinical-practice/13_May_CIHS_Innovations.pdf. Accessed 2019 Mar 28. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sohler NL, Weiss L, Egan JE, López CM, Favaro J, Cordero R, et al. Consumer attitudes about opioid addiction treatment: a focus group study in New York City. J Opioid Manag. 2013;9(2):111–9. doi: 10.5055/jom.2013.0152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sullivan LE, Chawarski M, O’Connor PG, Schottenfeld RS, Fiellin DA. The practice of office-based buprenorphine treatment of opioid dependence: is it associated with new patients entering into treatment? Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;79(1):113–6. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fingerhood MI, King VL, Brooner RK, Rastegar DA. A comparison of characteristics and outcomes of opioid-dependent patients initiating office-based buprenorphine or methadone maintenance treatment. Subst Abus. 2014;35(2):122–6. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2013.819828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Baxter JD, Clark RE, Samnaliev M, Leung GY, Hashemi L. Factors associated with Medicaid patients’ access to buprenorphine treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2011;41(1):88–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2011.02.002. Epub 2011 Apr 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hansen HB, Siegel CE, Case BG, Bertollo DN, DiRocco D, Galanter M. Variation in use of buprenorphine and methadone treatment by racial, ethnic and income characteristics of residential social areas in New York City. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2013;40(3):367–77. doi: 10.1007/s11414-013-9341-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Oliva EM, Harris AH, Trafton JA, Gordon AJ. Receipt of opioid agonist treatment in the Veterans Health Administration: facility and patient factors. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;122(3):241–6. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.10.004. Epub 2011 Nov 23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kiran T, Kopp A, Glazier RH. Those left behind from voluntary medical home reforms in Ontario, Canada. Ann Fam Med. 2016;14(6):517–25. doi: 10.1370/afm.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Glazier RH, Redelmeier DA. Building the patient-centered medical home in Ontario. JAMA. 2010;303(21):2186–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rao H, Mahadevappa H, Pillay P, Sessay M, Abraham A, Luty J. A study of stigmatized attitudes towards people with mental health problems among health professionals. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2009;16(3):279–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2008.01369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zaric GS, Brennan AW, Varenbut M, Daiter JM. The cost of providing methadone maintenance treatment in Ontario, Canada. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2012;38(6):559–66. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2012.694518. Epub 2012 Jul 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]