Abstract

Background.

A range of endophenotypes characterise psychosis, however there has been limited work understanding if and how they are inter-related.

Methods.

This multi-centre study includes 8754 participants: 2212 people with a psychotic disorder, 1487 unaffected relatives of probands, and 5055 healthy controls. We investigated cognition [digit span (N = 3127), block design (N = 5491), and the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (N = 3543)], electrophysiology [P300 amplitude and latency (N = 1102)], and neuroanatomy [lateral ventricular volume (N =1721)]. We used linear regression to assess the interrelationships between endophenotypes.

Results.

The P300 amplitude and latency were not associated (regression coef. −0.06, 95% CI −0.12 to 0.01, p = 0.060), and P300 amplitude was positively associated with block design (coef. 0.19, 95% CI 0.10–0.28, p < 0.001). There was no evidence of associations between lateral ventricular volume and the other measures (all p > 0.38). All the cognitive endophenotypes were associated with each other in the expected directions (all p < 0.001). Lastly, the relationships between pairs of endophenotypes were consistent in all three participant groups, differing for some of the cognitive pairings only in the strengths of the relationships.

Conclusions.

The P300 amplitude and latency are independent endophenotypes; the former indexing spatial visualisation and working memory, and the latter is hypothesised to index basic processing speed. Individuals with psychotic illnesses, their unaffected relatives, and healthy controls all show similar patterns of associations between endophenotypes, endorsing the theory of a continuum of psychosis liability across the population.

Keywords: Lateral ventricular volume, P300, schizophrenia, verbal memory, unaffected relatives, working memory

Introduction

Psychotic disorders, including schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, have considerable heritability with estimates ranging between 60 and 85% (Cardno et al. 1999; Smoller & Finn, 2003; Sullivan et al. 2012), and there is evidence of significant genetic overlap between these disorders (Lee et al. 2013). Psychoses are complex genetic disorders where many common variants contribute small increments of risk, and rare variants contribute greater risks (Gratten et al. 2014; Geschwind & Flint, 2015). While many common loci and some rare variants have now been identified (Stefansson et al. 2008; Stone et al. 2008; Walsh et al. 2008; Xu et al. 2008; Purcell et al. 2009; Grozeva et al. 2011; Sklar et al. 2011; Lee et al. 2013; Ripke et al. 2013, 2014; Green et al. 2015), little is known about their functional roles and the mechanisms through which they lead to the disease (Geschwind & Flint, 2015; Harrison, 2015).

Endophenotypes could help us gain a better understanding of the underlying neurobiology (Gottesman & Gould, 2003; Cannon & Keller, 2006; Gur et al. 2007). These are biological markers which are heritable, co-segregate with a disorder within families, are observed in unaffected family members at a higher rate than in the general population, and are expressed in an individual whether or not the illness is active (Gottesman & Gould, 2003). Endophenotypes could thus be used to better understand the mechanisms underlying the associations between genetic variants and the disorder (Hall & Smoller, 2010; Braff, 2015).

Although there is an extensive literature identifying and validating endophenotypes for psychosis, fewer studies have examined the relationships between different endophenotypes. Studies conducted so far have mainly analysed the associations between different cognitive measures (Toomey et al. 1998; Dickinson et al. 2002, 2006; Sullivan et al. 2003; Gladsjo et al. 2004; Sheffield et al. 2014; Seidman et al. 2015), but there is a lack of literature examining brain structural-cognitive and electrophysiological–cognitive pairings. Moreover, the inclusion of unaffected relatives in these studies has been rare, yet examining relatives – who carry increased genetic risk but have no illness or treatment confounding factors – is crucial for establishing the utility of these markers for genetic research.

This study seeks to investigate the relationships between the following electrophysiological, neurocognitive, and neuroanatomical endophenotypes for psychosis:

P300 event-related potential: Reduced amplitude and prolonged latency of the P300 wave have consistently been found in patients with psychotic illnesses as well as in unaffected relatives, compared with controls (Blackwood et al. 1991; Weisbrod et al. 1999; Pierson et al. 2000; Winterer et al. 2003; Bramon et al. 2005; Price et al. 2006; Schulze et al. 2008; Bestelmeyer et al. 2009; Díez et al. 2013; Light et al. 2015; Turetsky et al. 2015). The P300 amplitude is thought to be a correlate of attention and working memory (Naatanen, 1990; Ford, 2014). Although the latency has been less precisely characterized, it is thought to index classification speed (Polich, 2007, 2011).

Cognitive performance: Deficits on cognitive tests such as digit span (measuring working memory), block design (measuring working memory and spatial visualisation), and the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Task (RAVLT) immediate and delayed recall (measuring short- and long-term verbal memory, respectively) are common and persistent across psychotic disorders (Heinrichs & Zakzanis, 1998; Gur et al. 2007; Bora et al. 2009; Stone et al. 2011; Bora & Pantelis, 2015; Kim et al. 2015b; Lee et al. 2015). Abnormalities are often observed before the onset of the illness as well as in unaffected relatives (Glahn et al. 2006; Saperstein et al. 2006; Snitz et al. 2006; Birkett et al. 2008; Horan et al. 2008; Forbes et al. 2009; Reichenberg et al. 2010; Ivleva et al. 2012; Park & Gooding, 2014; Gur et al. 2015).

Lateral ventricular volume: Increased ventricular volume is a highly replicated finding in patients with psychosis compared with controls (Sharma et al. 1998; Fannon et al. 2000; Wright et al. 2000; Shenton et al. 2001; McDonald et al. 2002, 2006; Strasser et al. 2005; Boos et al. 2007; Crespo-Facorro et al. 2009; Kempton et al. 2010; Fusar-Poli et al. 2013; Haijma et al. 2013; Kumra et al. 2014). This enlargement has been attributed to neurodevelopmental difficulties, disease progression, and/or the effects of antipsychotic medications (Pilowsky et al. 1993; Gogtay et al. 2003; McDonald et al. 2006).

This multi-centre study, seeking to investigate the relationships between multi-modal endophenotypes, includes the largest sample yet of individuals with psychosis, their unaffected first-degree relatives, and controls. The main objective is to facilitate the use of endophenotypes for genetic research into psychosis, which requires well defined and characterised measures. The aim of this study was therefore to examine the relationships between different endophenotype pairs, and in particular, to characterise the P300 event related potential in the context of well-defined cognitive markers.

Methods and materials

Sample and clinical assessments

The total sample included 8754 participants: 2212 individuals with a diagnosis of a psychotic disorder (see Table 1 for a breakdown of diagnoses), 1487 of their unaffected first-degree relatives (with no personal history of psychosis), and 5055 healthy controls (with no personal or family history of psychosis). Relatives and controls were not excluded if they had a personal history of non-psychotic disorders (such as depression or anxiety), provided they were well and off psychotropic medication at the time of testing and for the preceding 12 months.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics (N = 8754)

| Patients with psychosis | Unaffected relatives | Controls | Total sample | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size, N (%) | 2212 (25.3%) | 1487 (17.0%) | 5055 (57.7%) | 8754 |

| Age, mean years (S.D.)a | 33.6 (10.6) | 46.0 (15.8) | 45.5 (16.2) | 42.6 (15.8) |

| Age range (years) | 16–79 | 16–85 | 16–89 | 16–89 |

| Gender (% female)a | 32.1% | 58.0% | 51.5% | 47.7% |

| Diagnoses; N (%) | ||||

| Schizophrenia | 1396 (63.1%) | - | - | 1396 (15.9%) |

| Bipolar I disorder | 135 (6.1%) | - | - | 135 (1.5%) |

| Psychosis NOS | 168 (7.6%) | - | - | 168 (1.9%) |

| Schizophreniform disorder | 158 (7.1%) | - | - | 158 (1.8%) |

| Schizoaffective disorder | 124 (5.6%) | - | - | 124 (1.4%) |

| Brief psychotic disorder | 56 (2.5%) | - | - | 56 (0.6%) |

| Other psychotic illness | 175 (7.9%) | - | - | 175 (2.0%) |

| Depression | 246 (16.5%) | 232 (4.6%) | 478 (5.5%) | |

| Anxiety | 47 (3.2%) | 24 (0.5%) | 71 (0.8%) | |

| Other non-psychotic illness | 62 (4.2%) | 106 (2.1%) | 168 (1.9%) | |

| No psychiatric illness | 1132 (76.1%) | 4693 (92.8%) | 5825 (66.5%) | |

| Endophenotypes N=sample size, Mean (SD) of raw scores unadjusted for covariates | ||||

| N = 397 | N = 379 | N = 313 | N =1089 | |

| 10.5 (6.1) | 11.0 (6.7) | 13.7 (7.0) | 11.6 (6.7) | |

| N = 401 | N = 386 | N = 315 | N =1102 | |

| 382.6 (55.3) | 390.8 (56.1) | 356.9 (39.1) | 378.2 (53.3) | |

| N = 700 | N = 337 | N = 684 | N =1721 | |

| 17.9 (9.9) | 18.7 (11.2) | 15.8 (8.8) | 17.1 (9.8) | |

| N = 850 | N = 895 | N = 3746 | N = 5491 | |

| 49.9 (27.9) | 47.4 (25.6) | 60.4 (21.2) | 56.6 (23.8) | |

| N = 460 | N =136 | N = 2531 | N = 3127 | |

| 47.4 (15.9) | 40.0 (4.5) | 51.5 (14.5) | 50.4 (14.9) | |

| N = 1232 | N = 934 | N = 1377 | N = 3543 | |

| 7.6 (2.2) | 8.4 (2.1) | 8.7 (2.0) | 8.2 (2.2) | |

| N = 1224 | N = 927 | N = 1358 | N = 3509 | |

| 2.1 (1.0) | 2.9 (1.0) | 2.9 (0.9) | 2.6 (1.0) |

S.D., standard deviation; NOS, not otherwise specified; RAVLT, Rey auditory verbal learning task.

Missing data for age (717 subjects) and gender (6 subjects).

The group differences in endophenotype performance adjusted by covariates are reported in Table 2.

To confirm or rule out a DSM-IV (APA, 1994) diagnosis, all participants underwent a structured clinical interview with either the Comprehensive Assessment of Symptoms and History (Andreasen et al. 1992), the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Disorders (Spitzer et al. 1992), the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (Endicott & Spitzer, 1978) or the Schedule for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry, Version 2.0 (Wing et al. 1990). Participants were excluded if they had a history of neurologic disease or a loss of consciousness due to a head injury.

Recruitment took place across 11 locations in Australia and Europe (Germany, Holland, Spain, and the UK) (see online Supplementary Table S1 in the supplement). Participants provided written informed consent, and the study was approved by the respective ethical committees at each of the 11 participating centres.

The main focus of this paper is an analysis of the associations between different endophenotype domains, which represents new and unpublished data. Some centres have previously published comparisons in endophenotype performance between groups (patients, relatives, and controls) (Weisbrod et al. 1999; Hulshoff Pol et al. 2002; McDonald et al. 2002; Steel et al. 2002; Bramon et al. 2005; Johnstone et al. 2005; Hall et al. 2006b; Price et al. 2006; Schulze et al. 2006; González-Blanch et al. 2007; Crespo-Facorro et al. 2009; Waters et al. 2009; Wobrock et al. 2009; Toulopoulou et al. 2010; Collip et al. 2013). Here we also present results of a mega-analysis of the combined multi-centre sample.

Neuropsychological assessments

The Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, revised version (Wechsler, 1981) or third edition (Wechsler, 1997), were administered to participants. Performance on two subtests was used for analyses: the combined forward and backward digit span (measuring attention and working memory) and block design (measuring spatial visualisation). The Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (Rey, 1964), including both immediate and delayed recall (assessing short- and long-term verbal memory, respectively), was also administered. Higher scores on the cognitive tasks indicate better performance. Full methodology for each contributing site is reported elsewhere (Johnstone et al. 2005; Crespo-Facorro et al. 2007; González-Blanch et al. 2007; Waters et al. 2009; Toulopoulou et al 2010; Walters et al. 2010; Korver et al. 2012).

EEG data collection and processing

Electrophysiological data were obtained from three sites (online Supplementary Table S1). EEG data acquisition and processing methods varied slightly between sites as summarised below. The full methods for each site are reported elsewhere (Weisbrod et al. 1999; Bramon et al. 2005; Hall et al. 2006b; Price et al. 2006; Waters et al. 2009).

In summary, EEG was collected from 17 to 20 electrodes placed according to the International 10/20 system (Jasper, 1958). The P300 event related potential was obtained using a standard two-tone frequency deviant auditory oddball paradigm, with standard (‘non target’) tones of 1000 Hz and rare (‘target’) tones of 1500 Hz. The number of tones presented varied from 150 to 800, the tones were 80 dB or 97 dB, lasted for 20–50 ms, and the inter-stimulus interval was between 1 and 2 s. The majority of participants (93.4%) were asked to press a button in response to ‘target’ stimuli, but a subset were asked to close their eyes and count ‘target’ stimuli in their head.

The data were continuously recorded in one of three ways: 500 Hz sampling rate and 0.03–120 Hz band pass filter; 200 Hz sampling rate and 0.05–30 Hz band pass filter; or 400 Hz sampling rate and 70 Hz low-pass filter. Linked earlobes or mastoids were used as reference and vertical, and in most cases also horizontal, electro-oculographs were recorded at each site and used to correct for eye-blink artefacts using regression based weighting coefficients (Semlitsch et al. 1986). After additional manual checks, artefact-free epochs were included and baseline corrected before averaging. The averaged waveforms to correctly detected targets were then filtered using 0.03 or 0.05 Hz high-pass and 30 or 45 Hz low-pass filters. The peak amplitude and latency of the P300 were measured at electrode location PZ ( parietal midline), within the range of 250–550 ms post-stimulus.

MRI data collection and processing

MRI data acquisition and image processing varied between sites; see previous publications and the supplementary materials for an outline of the methods used for each centre (Barta et al. 1997; Frangou et al. 1997; Hulshoff Pol et al. 2002; McDonald et al. 2002, 2006; McIntosh et al. 2004, 2005a, b; Schulze et al. 2006; Crespo-Facorro et al. 2009; Dutt et al. 2009; Mata et al. 2009; Wobrock et al. 2009; Habets et al. 2011; Collip et al. 2013). Field strengths included 1, 1.5 or 3 Tesla. Lateral ventricular volumes were measured using automatic or semi-automatic region of interest analyses, and included the body, frontal, occipital, and temporal horns.

Statistical methods

Mega-analysis of group comparisons

Endophenotype measures were first standardised for each site separately using the mean and standard deviation within each site. Linear regression analyses for each measure were used to establish whether endophenotype performance differed according to group (patients, relatives, and controls). The outcome in each regression model was the endophenotype measure and the main predictor was group. These analyses were adjusted for age, gender, clinical group, study site and, where significant, group x site

Associations between endophenotypes

Linear regression models were used to investigate associations between each pair of endophenotypes. Potential effect modification by group membership was assessed by specifying in the statistical model a term for the interaction between the predictor of the endophenotype pair and group (patient, relative, control). Where we found evidence that the relationship between a pair of endophenotypes differed according to group, associations are reported separately for patients, relatives, and controls. Where there was no evidence of effect modification, the interaction term was dropped from the model, and associations are reported for the whole sample adjusted for group. These analyses were adjusted for age, gender, clinical group, and study site.

In all analyses, we accounted for correlations between individuals within families using robust standard errors. 63% of the participants had no other family member taking part, but the study also included 1056 families of 2–11 members each (85% of the families had only two members included in the sample). This family clustering violates the independence of observations assumption in linear regression. To account for this clustered structure in the dataset we created a new variable ‘family ID’ that was shared by all individuals in each family. Then we used the variance estimator with the robust cluster option in all the linear regression models. This allowed us to account for the within-family correlations and maintain correct type-1 error rates. This is a standard approach in family studies (Shaikh et al. 2013; Bramon et al. 2014; Ranlund et al. 2014).

We examined the distribution of residuals and plots of residuals v. fitted values for all models and were able to rule out departures from normality and heteroscedasticity. Lateral ventricular volume showed a positively skewed distribution and to account for this we used bootstrap methods for analyses where this is the outcome variable. Heteroscedasticity was not found to be a concern for ventricular volumes. P values are not presented for the models which used bootstrapping; instead, we examined the 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals to check for statistical significance at the 5% level (p = 0.05).

Although we tested seven endophenotypes, we expect measurements within domains to be correlated and thus a correction of p values by seven tests through Bonferroni or other methods was deemed too stringent for a hypothesis-driven study such as this (Rothman, 1990; Savitz & Olshan, 1995; Perneger, 1998). We therefore corrected for associations between three domains (EEG, MRI, cognition), with a corrected significance threshold of 0.05/3 = 0.0167, that we rounded to the slightly more stringent cut-off of p <0.01. Statistical analyses were conducted using STATA version 13.

Results

Sample characteristics

The sample characteristics are summarised in Table 1. Patients were on average 12.4 years younger than relatives (95% CI: 11.4–13.4; p < 0.001) and 11.9 years younger than controls (95% CI: 11.1–12.7; p < 0.001). There was no evidence of any age difference between relatives and controls. There was a lower proportion of females than males among patients than among relatives and controls (32.1%, 58.0%, and 51.5% respectively; global p < 0.001).

Group comparisons on endophenotype performance

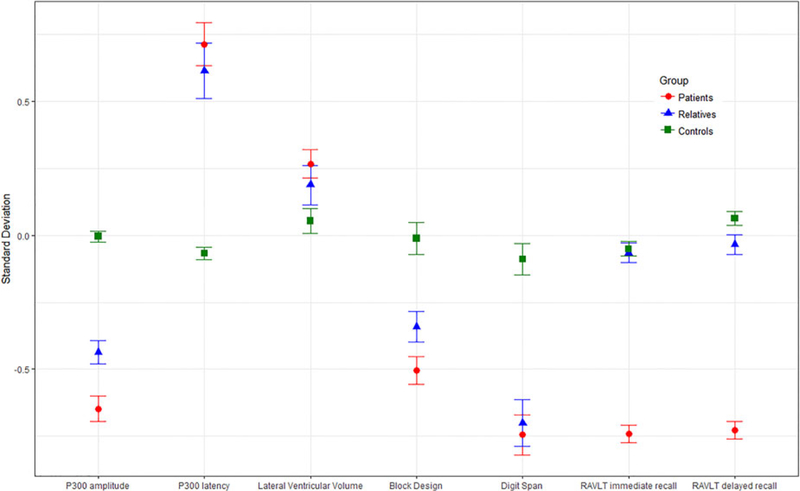

As shown in Fig. 1 and Table 2, differences between the three participant groups on the endophenotypes followed the expected pattern with performance improving from patients through to relatives and controls. We found evidence that patients’ scores differed significantly from those of controls with smaller P300 amplitudes, delayed P300 latency, larger lateral ventricular volumes and deficits in digit span, block design and RVLT immediate recall. When compared with controls, the unaffected relatives showed reduced P300 amplitude, delayed P300 latency and poorer performance in digit span and block design.

Fig. 1.

Estimated marginal means (adjusted for average age, gender, and study site) of standardised endophenotype scores by group (patients, relatives, and con- trols). Error bars represent standard errors of the means. RAVLT, Rey auditory verbal learning task.

Table 2.

Endophenptype performance comparison across clinical groups

| Total sample | Patients - controls | Patients - relatives | Relatives - controls | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endophenotype | Global, p value* | Mean difference (95% CI) | Mean difference (95% CI) | Mean difference (95% CI) |

| P300 amplitude | <0.001 | −0.50 (−0.71 to −0.29) p <0.001 | −0.16 (−0.32 to −0.01) p = 0.061 | −0.34 (−0.54 to −0.14) p = 0.001 |

| P300 latency | <0.001 | 0.47 (0.33–0.61) p <0.001 | 0.03 (−0.14–0.19) p = 0.749 | 0.44 (0.29–0.60) p <0.001 |

| Lateral ventricular volume | 0.20 (0.08–0.32) | 0.09 (−0.06 to 0.23) | 0.11 (−0.04 to 0.25) | |

| Digit span | <0.001 | −0.72 (−0.88 to −0.55) p < 0.001 | −0.14 (−0.32 to 0.05) p = 0.141 | −0.58 (−0.77 to −0.39) p <0.001 |

| Block design | <0.001 | −0.91 (−1.07 to −0.75) p <0.001 | −0.08 (−0.21 to 0.04) p = 0.190 | −0.83 (−0.97 to −0.69) p <0.001 |

| RAVLT immediate recall | <0.001 | −1.32 (−2.29 to −0.37) p = 0.007 | −1.24 (−2.22 to −0.27) p = 0.012 | −0.08 (−0.24 to 0.07) p = 0.286 |

| RAVLT delayed recall | =0.123 | −0.98 (−2.21 to 0.25) p = 0.118 | −0.94 (−2.18 to 0.30) p = 0.136 | −0.03 (−0.20 to 0.13) p = 0.669 |

Linear regression models investigating group differences on endophenotype performance. Endophenotype data were standardised for each site using the mean and standard deviation within each site. The main predictor was clinical group (patients, relatives, and controls). All models included age, gender, study site and, where significant, group × centre interactions. We used robust standard errors to account for correlations within families in all models.

P value for the overall test of a group effect; Note that p values were not produced for the models that include lateral ventricular volume since we used bootstrapping, which is a percentile-based method; therefore we looked at the bias-corrected confidence intervals to check for significance.

RAVLT, Rey auditory verbal learning task; CI, confidence interval.

Associations between endophenotype pairs

Associations which do not differ according to clinical group

Associations between endophenotype pairs where there was no evidence of effect modification by group are reported in Table 3. There was no evidence of an association between the P300 amplitude and latency at the 1% level of statistical significance (coef. −0.06, 95% CI −0.12 to 0.01, p = 0.06). The P300 amplitude was positively associated with digit span (coef. 0.15, 95% CI 0.04–0.26, p = 0.009) and block design (coef. 0.19, 95% CI 0.10–0.28, p < 0.001) performances, but not with either of the RAVLT measures. The P300 latency showed weak evidence of a negative association with digit span (coef. −0.15, 95& CI −0.28 to −0.03, p = 0.017). Lateral ventricular volume showed no evidence of an association with any of the other measures. All cognitive pairings were significantly positively associated (all p <0.001).

Table 3.

Adjusted associations between endophenotypes in the whole sample

| P300 latency | Lateral ventricular volume | Digit span | Block design | RAVLT immediate recall | RAVLT delayed recall | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P300 amplitude | N =1083 | N = 428 | N = 340 | N = 426 | N = 255 | N = 255 |

| −0.06 (−0.12 to 0.01) | 0.05 (−0.07 to 0.15) | 0.15 (0.04–0.26) | 0.19 (0.10–0.28) | 0.11 (−0.02 to 0.25) | 0.08 (−0.06 to 0.22) | |

| p = 0.060 | p = 0.009 | p <0.001 | p = 0.102 | p = 0.281 | ||

| P300 latency | - | N = 434 | N = 346 | N = 437 | N = 254 | N = 254 |

| 0.02 (−0.08 to 0.15) | −0.15 (−0.28 to −0.03) | −0.04 (−0.12 to 0.04) | 0.03 (−0.09 to 0.15) | 0.03 (−0.07 to 0.14) | ||

| p = 0.017 | p = 0.333 | p = 0.699 | p = 0.501 | |||

| Lateral ventricular volume | - | N = 468 | N =1001 | N = 498 | N = 492 | |

| −0.01 (−0.09 to 0.09) | 0.02 (−0.04 to 0.09) | −0.04 (−0.14 to 0.06) | −0.02 (−0.11 to 0.09) | |||

| Digit Span | - | N = 2754 | N = 291 | N = 291 | ||

| 0.33 (0.30–0.36) | 0.39 (0.28–0.49) | 0.31 (0.20–0.42) | ||||

| p <0.001 | p <0.001 | p < 0.001 | ||||

| Block Design | - | N = 2169 | N = 2137 | |||

| 0.26 (0.21–0.30) | 0.24 (0.20–0.29) | |||||

| p <0.001 | p <0.001 | |||||

| RAVLT immediate recall | - | N = 3505 | ||||

| 0.76 (0.74–0.78) | ||||||

| p < 0.001 |

RAVLT, Rey auditory verbal learning task.

Regression models using standardised scores, adjusted for age, gender, study site and group using robust standard errors to account for correlations within families and, where significant, group × by centre interactions.

Statistics reported are sample sizes, regression coefficients (95% confidence intervals), and p values. Note that p values were not produced for the models that include lateral ventricular volume since we used bootstrapping, which is a percentile-based method; therefore we looked at the bias-corrected confidence intervals to check for significance.

Associations which differ according to clinical group

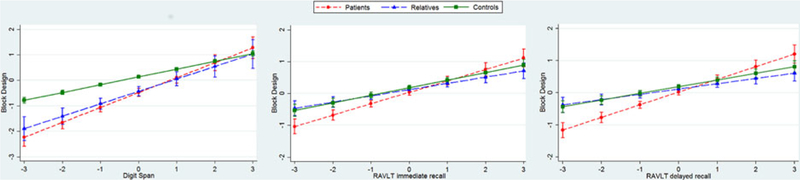

For three pairs of cognitive endophenotypes, we found evidence of an interaction with group. This indicates that the association between these endophenotype pairs differs between patients, relatives, and controls, as reported in Fig. 2 (and online Supplementary Table S3 in the Supplement). In all three cases, the relationship between endophenotype pairs was in the same direction for the three groups, differing only in magnitude.

Fig. 2.

Interactions between group (patient, relative, and control) and endophenotype pairs (standardised scores). Graphs are adjusted for covariates (age, gender, and study site), and include 95% confidence intervals. RAVLT, Rey auditory verbal leaming task

There was strong evidence that digit span and RAVLT immediate and delayed recall were positively associated with scores on the block design task in all three groups (patients, relatives, and controls). The magnitude of each association was greater among patients than controls (all p < 0.01), but there was no evidence that the strength of the relationship among relatives was different from that among controls (all p > 0.03). See online supplementary Table S3 for full results.

Discussion

This study examined the relationships between different multimodal psychosis endophenotypes in a large multi-centre sample of patients, their unaffected first-degree relatives, and controls.

Our mega-analysis confirms that both patients and relatives showed reduced amplitudes and prolonged latencies of the P300, compared with controls, replicating past findings and providing further evidence that these are endophenotypes for psychosis (Turetsky et al. 2000; Bramon et al. 2005; Price et al. 2006; Schulze et al. 2008; Thaker, 2008; Bestelmeyer et al. 2009; Díez et al. 2013). We found no evidence of association between the P300 amplitude and latency, indicating that these are independent measures. To examine whether variability on P300 amplitude and latency could potentially affect the correlations between these, we tested for heteroscedasticity between clinical groups. The standard deviations between the patient, relative, and control groups did not vary significantly and are thus unlikely to explain the lack of correlation between P300 amplitude and latency performance. In contrast to our results, Hall et al. (Hall et al. 2006a) and Polich et al. (Polich, 1992; Polich et al. 1997) found a negative correlation between the amplitude and latency. Notably however, these past studies included only small samples (up to 128 participants) compared with our study (N = 1083), and they did not take into account covariates such as age and gender that are known to influence both P300 parameters (Goodin et al. 1978; Polich et al. 1985; Conroy & Polich, 2007; Chen et al. 2013). Furthermore, in the studies by Polich et al. (Polich, 1992; Polich et al. 1997) the amplitude – latency correlation was strongest over frontal electrodes, and not parietal as investigated in our current study. More recently, Hall et al. (2014) found a negative correlation between the amplitude and latency in a sample of 274 patients with psychosis and controls after controlling for age and gender effects. Further research is thus needed to clarify the relationship between the P300 amplitude and latency. However, our findings in this large sample suggest that the measures are independent, indexing separate brain functions.

We found associations between the P300 amplitude and both digit span and block design, as in previous smaller studies (Souza et al. 1995; Polich et al. 1997; Fjell & Walhovd, 2001; Hermens et al. 2010; Kaur et al. 2011; Dong et al. 2015b). According to the context-updating theory (Heslenfeld, 2003; Kujala & Naatanen, 2003), the P300 amplitude is an attention-driven, context-updating mechanism, which subsequently feeds into memory stores (Polich, 2007, 2011). Hence, one would expect the amplitude to be associated with cognitive tasks that require attention and working memory, such as digit span and block design (Näätänen, 1990; Baddeley, 1992; Ford, 2014). The context-updating theory provides a possible explanation for the association between P300 amplitude and block design, since this task requires a constant update of the mental representation of the blocks, in order to complete the target pattern (Polich, 2007, 2011). The lack of evidence for associations between P300 amplitude and the RAVLT tests support the idea that the neurobiology of verbal memory is distinct from the attentional and working memory processes linked to the P300 amplitude (Polich, 2011).

The P300 latency showed evidence of a trend-level association with digit span, and no evidence of an association with the other measures. Previous studies have provided conflicting results, with some reporting associations with attention and working memory (Polich et al. 1983), while others have not (Fjell & Walhovd, 2001; Walhovd & Fjell, 2003; Dong et al. 2015b). The P300 latency has been conceptualised as a measure of classification speed (Polich, 2011; van Dinteren et al. 2014). Investigating the relationship between behavioural reaction times (i.e. the speed of button press in the task) and the P300 latency, some have found associations (Bashore et al. 2014) while others have not (Ramchurn et al. 2014). Furthermore, there is a substantial body of research showing that the P300 latency as well as reaction times increase (that is they slow down) with ageing in healthy participants (Polich, 1996; Chen et al. 2013). Based on our findings we hypothesise that the P300 latency is a specific measure of processing speed at a basic neuronal level. In contrast, block design and the RAVLT task – while influenced by processing speed – reflect wider cognition including spatial abilities and verbal memory. The more complex elements to these tasks may therefore obscure effects of a simple processing speed, and hence explain the lack of association with P300 latency. The trend-level association with digit span performance – a task dependent on attention and short-term working memory – is in line with this interpretation too.

In terms of lateral ventricular volume, there was no evidence of a relationship with any other endophenotype investigated. Enlargement of cerebral ventricles remains the best replicated biological marker in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, according to several meta-analyses (Kempton et al. 2010; Olabi et al. 2011; De Peri et al. 2012; Fusar-Poli et al. 2013; Fraguas et al. 2016; van Erp et al. 2016; Huhtaniska et al. 2017; Moberget et al. 2017). Our hypothesis that ventricular volumes would correlate with other endophenotypes of a functional nature was not confirmed by our data. Of course for such analyses our sample size was modest ranging 428–1001 and lack of statistical power could be a potential reason. Keilp et al. (Keilp et al. 1988) found an association with verbal memory and others have found enlarged lateral ventricles to be associated with poorer motor speed (Antonova et al. 2004; Hartberg et al. 2011; Dong et al. 2015a). A limitation of our study is the heterogeneity of the MRI methodology between study sites, which might have obscured any true associations. We conclude that ventricular volumes do not seem to exert a detectable influence on brain function in terms of cognition or cortical neurophysiology, however association studies of structural-functional biomarkers in larger samples are needed.

With regard to group comparisons, although patients showed enlarged lateral ventricles compared with controls, a very well supported finding (Wright et al. 2000; Steen et al. 2006; Cahn et al. 2009; Kempton et al. 2010), having adjusted by age and sex we observed no volume differences between relatives and controls. This is consistent with the latest meta-analysis of brain structure in relatives of patients with schizophrenia (Boos et al. 2007), and suggests that enlarged ventricles in patients are less heritable than previously thought. Instead, they might be related to illness progression, or to environmental effects or antipsychotic medication, as seen in both animal models of antipsychotic exposure (Dorph-Petersen et al. 2005; Konopaske et al. 2007), and in human studies (Ho et al. 2011; Fusar-Poli et al. 2013; Van Haren et al. 2013).

For all cognitive measures, patients performed less well than controls, consistent with extensive literature (Ayres et al. 2007; Horan et al. 2008; Bora et al. 2010, 2014; Fusar-Poli et al. 2012; Bora & Murray, 2014; Fatouros-Bergman et al. 2014; Stone et al. 2015). For the digit span and block design, there were also statistically significant differences between relatives and controls, suggesting a possible effect of increased genetic risk for psychosis. However, this was not seen for the immediate or delayed recall of the RAVLT task, where controls and relatives had similar performance. While some have reported verbal memory impairments in relatives of patients (Sitskoorn et al. 2004; Wittorf et al. 2004; Massuda et al. 2013), other studies have not (Üçok et al. 2013; Kim et al. 2015a). These findings suggest that working memory and spatial visualisation might represent more promising endophenotypes for genetic research into psychosis than verbal memory.

The associations between pairs of cognitive measures were strong and in the expected directions, as per previous findings (Dickinson et al. 2002; Sullivan et al. 2003; Gladsjo et al. 2004; Sheffield et al. 2014; Seidman et al. 2015). It is interesting to note that for some cognitive measures, the relationships interacted with group; however, the direction of the effect remained the same across patients, relatives, and controls. The interaction effects with group were found exclusively amongst the cognitive measures, and not in any of the other domains. This is possibly due to the larger sample sizes for the cognitive measures, yielding greater statistical power and enabling the detection of subtle interaction effects.

Both the lack of interaction effects for most associations investigated, and the gradient effects identified (where there was an interaction), are consistent with the notion that endophenotype impairments characterising psychosis represent a continuum that includes both relatives and the general population. Ultimately this continuum reflects the underlying variation in genetic liability of developing the disease (Johns & van Os, 2001; Wiles et al. 2006; Allardyce et al. 2007; Esterberg & Compton, 2009; Ian et al. 2010; DeRosse & Karlsgodt, 2015).

This study has several limitations: Firstly, association analyses could only be done for those participants with data available for pairs of endophenotypes and this led to relatively smaller samples for some of the associations. Secondly, there was a mismatch in age and gender between patients and relatives. The group of relatives has older individuals and more females compared with the group of patients who are younger and include more males. This is a common occurrence in psychosis family studies because the onset of psychosis in typically in youth. Most of the families who participated in the study include unaffected parents (with greater participation of mothers) and their affected and unaffected offspring. Family studies in psychosis are less likely to recruit affected parents. Because of this, we recruited a control group with a wider age range than either the other groups and with a balanced gender distribution so as to improve the age and sex matching across the two key comparisons (controls v. patients, controls v. relatives). Furthermore, since age and sex remains a potential confounder, we included age and sex as co-variates in the models throughout the study. As shown in online Supplementary Table S4 in the supplement, there was no evidence of model instability based on the estimates and confidence interval width between the models with and without age and sex.

Another limitation of this study is that we were unable to account for potential moderators such as tobacco, other drug use and medication. Also, information about participants’ socioeconomic status was not available. These clinical and demographic variables could have a potentially important influence on how the three clinical groups perform on endophenotypes. However, the main analyses, which was to investigate associations between endophenotypes are all done within-individuals and are thus less likely to be influenced by exposure to drugs and medication. As for clinical variables such as depression, the sample included 5.5% of individuals with a history of depression. Depression did not constitute an exclusion criterion for our study because it is such a prevalent disorder that if excluded it would probably make our findings hard to generalize. We have re-analysed the group comparisons excluding all participants with a history of depression and the overall findings are unchanged.

A further potential limitation was the heterogeneity of methods between study sites; differences in cognitive test versions and variation on the EEG and MRI protocols all introduced greater variability into the data. All measures were standardised within centres to minimise this variability. Despite this challenge, it is precisely through this multi-centre effort that we were able to achieve a very large sample, the key strength of this study. As the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium’s work shows, large international collaborations are essential in genetic studies of common diseases and traits (Sklar et al. 2011; Lee et al. 2013; Smoller et al. 2013; Ripke et al. 2014). A further strength of this study is the use of regression models as opposed to the correlation approach frequently seen in the literature (Brewer et al. 1970; Polich et al. 1983, 1997; Breteler et al. 1994; Brillinger, 2001; Kim et al. 2003), which allowed us to account for somme important confounding factors, such as ageing effects. Not only did this approach reduce vulnerability to spurious correlations, but it allowed the examination of interesting interaction effects across groups.

In summary, this study has investigated the relationships between endophenotypes for psychosis, including measures of cognition, electrophysiology, and brain structure. We have shown that cognitive measures are associated with each other as expected, and we have provided support for the notion that the amplitude and latency of the P300 are independent endophenotypes. The P300 amplitude is an index of spatial visualisation and working memory, while the latency is hypothesised to be a correlate of basic speed of processing. Individuals with psychotic illnesses, their unaffected relatives, and healthy controls all have similar patterns of associations between all pairs of endophenotypes, endorsing the theory of a continuum of liability of developing psychosis across the population.

Co-authors who are members of the Psychosis Endophenotypes International Consortium (PEIC):

Maria J. Arranz1,2, Steven Bakker3, Stephan Bender4,5, Elvira Bramon6,2, David Collier7,2, Benedicto Crespo-Facorro8,9, Marta Di Forti2, Jeremy Hall10, Mei-Hua Hall11, Conrad Iyegbe2, Assen Jablensky12, René S. Kahn3, Luba Kalaydjieva13, Eugenia Kravariti2, Stephen M Lawrie10, Cathryn M. Lewis2, Kuang Lin2,14, Don H. Linszen15, Ignacio Mata16,9, Colm McDonald17, Andrew M McIntosh10,18, Robin M. Murray2, Roel A. Ophoff19, Marco Picchioni2, John Powell2, Dan Rujescu20,21, Timothea Toulopoulou2,22,23, Jim Van Os24,2, Muriel Walshe6,2, Matthias Weisbrod25,5, and Durk Wiersma26.

PEIC affiliations:

1Fundació de Docència i Recerca Mútua de Terrassa, Universitat de Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain.

2Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience, King’s College London, De Crespigny Park, London SE5 8AF, UK.

3University Medical Center Utrecht, Department of Psychiatry, Rudolf Magnus Institute of Neuroscience, The Netherlands.

4Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, University of Technology Dresden, Fetscherstrasse 74, 01307 Dresden, Germany.

5General Psychiatry, Vossstraße 4, 69115 Heidelberg, Germany.

6Division of Psychiatry & Institute of Cognitive Neuroscience, University College London, UK.

7Discovery Neuroscience Research, Lilly, UK.

8University Hospital Marqués de Valdecilla, IDIVAL, Department of Psychiatry, School of Medicine, University of Cantabria, Santander, Spain.

9CIBERSAM, Centro Investigación Biomédica en Red Salud Mental, Madrid, Spain.

10College of Biomedical and Life Sciences, Cardiff University, CF24 4HQ Cardiff, UK.

11Mclean Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Belmont MA, USA.

12Centre for Clinical Research in Neuropsychiatry, The University of Western Australia, Perth, Australia.

13Western Australian Institute for Medical Research and Centre for Medical Research, The University of Western Australia, Perth, Australia.

14Nuffield Department of Population Health, University of Oxford, Ocford, UK.

15Academic Medical Centre University of Amsterdam, Department of Psychiatry, Amsterdam The Netherlands.

16Fundacion Argibide, Pamplona, Spain.

17The Centre for Neuroimaging &Cognitive Genomics (NICOG) and NCBES Galway Neuroscience Centre, National University of Ireland Galway, Galway Ireland.

18Centre for Cognitive Ageing and Cognitive Epidemiology, University of Edinburgh, UK.

19UCLA Center for Neurobehavioral Genetics, 695 Charles E. Young Drive South, Los Angeles CA 90095, USA.

20University of Munich, Dept. of Psychiatry, Munich, Germany.

21University of Halle, Dept. of Psychiatry, Halle, Germany.

22Department of Psychology, Bilkent University, Main Campus, Bilkent, Ankara, Turkey.

23The State Key Laboratory of Brain and Cognitive Sciences and the Department of Psychology, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China.

24Maastricht University Medical Centre, South Limburg Mental Health Research and Teaching Network, EURON, Maastricht, The Netherlands.

25General Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, SRH Klinikum Karlsbad-Langensteinbach, Guttmannstrasse 1, 76307 Karlsbad, Germany.

26University Medical Center Groningen, Department of Psychiatry, University of Groningen, The Netherlands.

Co-authors who are members of the Genetic Risk and Outcome of Psychosis (GROUP) consortium:

Richard Bruggeman, MD, PhD, Department of Psychiatry, University Medical Center Groningen, University of Groningen; Wiepke Cahn, MD, PhD, Department of Psychiatry, Rudolf Magnus Institute of Neuroscience, University Medical Center Utrecht; Lieuwe de Haan, MD, PhD, Department of Psychiatry, Academic Medical Center, University of Amsterdam; René S. Kahn, MD, PhD, Department of Psychiatry, Rudolf Magnus Institute of Neuroscience, University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht, the Netherlands; Carin Meijer, PhD, Department of Psychiatry, Academic Medical Center, University of Amsterdam; Inez Myin-Germeys, PhD, South Limburg Mental Health Research and Teaching Network, EURON, Maastricht University Medical Center; Jim van Os, MD, PhD, South Limburg Mental Health Research and Teaching Network, EURON, Maastricht University Medical Center, Maastricht, the Netherlands, and King’s College London, King’s Health Partners, Department of Psychosis Studies, Institute of Psychiatry, London, England; and Agna Bartels, PhD, Department of Psychiatry, University Medical Center Groningen, University.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements.

We would like to thank all the patients, relatives, and controls who took part in this research, as well as the clinical staff who facilitated their involvement. This work was supported by the Medical Research Council (G0901310) and the Wellcome Trust (grants 085475/B/08/Z, 085475/Z/08/Z). We thank the UCL Computer Science Cluster team for their excellent support. This study was supported by the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre at University College London (mental health theme) and by the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre for Mental Health at the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and Institute of Psychiatry Kings College London.

E. Bramon thanks the following funders: BMA Margaret Temple grants 2016 and 2006, MRC- Korean Health Industry Development Institute Partnering Award (MC_PC_16014), MRC New Investigator Award and a MRC Centenary Award (G0901310), National Institute of Health Research UK post-doctoral fellowship, the Psychiatry Research Trust, the Schizophrenia Research Fund, the Brain and Behaviour Research foundation’s NARSAD Young Investigator Awards 2005, 2008, Wellcome Trust Research Training Fellowship.

Further support: The Brain and Behaviour Research foundation’s (NARSAD’s) Young Investigator Award (Grant 22604, awarded to C. Iyegbe). The BMA Margaret Temple grant 2016 to Johan Thygesen. European Research Council Marie Curie award to A Díez-Revuelta.

The infrastructure for the GROUP consortium is funded through the Geestkracht programme of the Dutch Health Research Council (ZON-MW, grant number 10–000-1001), and matching funds from participating pharmaceutical companies (Lundbeck, AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Janssen Cilag) and universities and mental health care organizations (Amsterdam: Academic Psychiatric Centre of the Academic Medical Center and the mental health institutions: GGZ Ingeest, Arkin, Dijk en Duin, GGZ Rivierduinen, Erasmus Medical Centre, GGZ Noord Holland Noord. Maastricht: Maastricht University Medical Centre and the mental health institutions: GGZ Eindhoven en de kempen, GGZ Breburg, GGZ Oost-Brabant, Vincent van Gogh voor Geestelijke Gezondheid, Mondriaan Zorggroep, Prins Clauscentrum Sittard, RIAGG Roermond, Universitair Centrum Sint-Jozef Kortenberg, CAPRI University of Antwerp, PC Ziekeren Sint-Truiden, PZ Sancta Maria Sint-Truiden, GGZ Overpelt, OPZ Rekem. Groningen: University Medical Center Groningen and the mental health institutions: Lentis, GGZ Friesland, GGZ Drenthe, Dimence, Mediant, GGNet Warnsveld, Yulius Dordrecht and Parnassia psycho-medical center (The Hague). Utrecht: University Medical Center Utrecht and the mental health institutions Altrecht, GGZ Centraal, Riagg Amersfoort and Delta.).

The sample from Spain was collected at the Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla, University of Cantabria, Santander, Spain, under the following grant support: Carlos III Health Institute PI020499, PI050427, PI060507, Plan Nacional de Drugs Research Grant 2005-Orden sco/3246/2004, SENY Fundació Research Grant CI 2005–0308007 and Fundación Marqués de Valdecilla API07/011. We wish to acknowledge Biobanco HUMV-IDIVAL for hosting and managing blood samples and IDIVAL Neuroimaging Unit for imaging acquirement and analysis.

Footnotes

Supplementary material. The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291717002860.

All authors declare that they have no financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

References

- Allardyce J, Suppes T, van Os J (2007) Dimensions and the psychosis pheno-type. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 16, S34–S40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen NC, Flaum M, Arndt S (1992) The Comprehensive Assessment of Symptoms and History (CASH) An instrument for assessing diagnosis and psychopathology. Archives of General Psychiatry 49, 615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonova E, Sharma T, Morris R, Kumari V (2004) The relationship between brain structure and neurocognition in schizophrenia: a selective review. Schizophrenia Research 70, 117–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- APA (1994) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edn. American Psychiatric Association: Washington. [Google Scholar]

- Ayres AM, Busatto GF, Menezes PR, Schaufelberger MS, Coutinho L, Murray RM, McGuire PK, Rushe T, Scazufca M (2007) Cognitive deficits in first-episode psychosis: a population-based study in Sao Paulo, Brazil . Schizophrenia Research 90, 338–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baddeley A (1992) Working memory. Science (New York, N.Y.) 255, 556–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barta PE, Dhingra L, Royall R, Schwartz E (1997) Improving sterological estimates for the volume of structures identified in three-dimensional arrays of spatial data. Journal of Neuroscience Methods 75, 111–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bashore TR, Wylie SA, Ridderinkhof KR, Martinerie JM (2014) Response-specific slowing in older age revealed through differential stimulus and response effects on P300 latency and reaction time. Neuropsychology, Development, and Cognition. Section B, Aging, Neuropsychology and Cognition 21, 633–673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bestelmeyer PEG, Phillips LH, Crombie C, Benson P, Clair DS (2009) The P300 as a possible endophenotype for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: evidence from twin and patient studies. Elsevier Ireland Ltd. Psychiatry Research 169, 212–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birkett P, Sigmundsson T, Sharma T, Toulopoulou T, Griffiths TD, Reveley A, Murray R (2008) Executive function and genetic predisposition to schizophrenia - the Maudsley family study. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part B: Neuropsychiatric Genetics 147B, 285–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackwood DH, St Clair DM, Muir WJ, Duffy JC (1991) Auditory P300 and eye tracking dysfunction in schizophrenic pedigrees. Archives of General Psychiatry 48, 899–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boos HBM, Aleman A, Cahn W, Hulshoff Pol H, Kahn RS (2007) Brain volumes in relatives of patients with schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Archives of General Psychiatry 64, 297–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bora E, Lin A, Wood SJ, Yung AR, McGorry PD, Pantelis C (2014) Cognitive deficits in youth with familial and clinical high risk to psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 130, 1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bora E, Murray RM (2014) Meta-analysis of cognitive deficits in ultra-high risk to psychosis and first-episode psychosis: do the cognitive deficits progress over, or after, the onset of psychosis? Schizophrenia Bulletin 40, 744–755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bora E, Pantelis C (2015) Meta-analysis of cognitive impairment in first-episode bipolar disorder: comparison with first-episode schizophrenia and healthy controls. Schizophrenia Bulletin 41, 1095–1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bora E, Yucel M, Pantelis C (2009) Cognitive functioning in schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder and affective psychoses: meta-analytic study. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science 195, 475–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bora E, Yucel M, Pantelis C (2010) Cognitive impairment in affective psychoses: a meta-analysis. Schizophrenia Bulletin 36, 112–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braff DL (2015) The importance of endophenotypes in schizophrenia research. Elsevier B.V. Schizophrenia Research 163, 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bramon E, McDonald C, Croft RJ, Landau S, Filbey F, Gruzelier JH, Sham PC, Frangou S, Murray RM (2005) Is the P300 wave an endopheno-type for schizophrenia? A meta-analysis and a family study. NeuroImage 27, 960–968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breteler MM, van Amerongen NM, van Swieten JC, Claus JJ, Grobbee DE, van Gijn J, Hofman A, van Harskamp F (1994) Cognitive correlates of ventricular enlargement and cerebral white matter lesions on magnetic resonance imaging. The Rotterdam Study. Stroke; A Journal of Cerebral Circulation 25, 1109–1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer MB, Campbell DT, Crano WD (1970) Testing a single-factor model as an alternative to the misuse of partial correlations in hypothesis-testing research. Sociometry 33, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Brillinger DR (2001) Does anyone know when the correlation coefficient is useful? A study of the times of extreme river flows. Technometrics 43, 266–273. [Google Scholar]

- Cahn W, Rais M, Stigter FP, van Haren NEM, Caspers E, Hulshoff Pol HE, Xu Z, Schnack HG, Kahn RS (2009) Psychosis and brain volume changes during the first five years of schizophrenia. European Neuropsychopharmacology: The Journal of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology 19, 147–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon TD, Keller MC (2006) Endophenotypes in the genetic analyses of mental disorders. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology 2, 267–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardno AG, Marshall EJ, Coid B, Macdonald AM, Ribchester TR, Davies NJ, Venturi P, Jones LA, Lewis SW, Sham PC, Gottesman II, Farmer AE, McGuffin P, Reveley AM, Murray RM (1999) Heritability estimates for psychotic disorders: the Maudsley Twin psychosis series. Archives of General Psychiatry 56, 162–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen KC, Lee IH, Yang YK, Landau S, Chang WH, Chen PS, Lu RB, David AS, Bramon E (2013) P300 waveform and dopamine transporter availability: a controlled EEG and SPECT study in medication-naive patients with schizophrenia and a meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine 44, 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collip D, Habets P, Marcelis M, Gronenschild E, Lataster T, Lardinois M, Nicolson NA, Myin-Germeys I (2013) Hippocampal volume as marker of daily life stress sensitivity in psychosis. Psychological Medicine 43, 1377–1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conroy MA, Polich J (2007) Normative variation of P3a and P3b from a large sample. Journal of Psychophysiology 21, 22–32. [Google Scholar]

- Conroy MA, Polich J (2007) Normative variation of P3a and P3b from a large sample. Journal of Psychophysiology 21, 22–32. [Google Scholar]

- Crespo-Facorro B, Roiz-Santiáñez R, Pelayo-Terán JM, Rodríguez-Sánchez JM, Pérez-Iglesias R, González-Blanch C, Tordesillas-Gutiérrez D, González-Mandly A, Díez C, Magnotta VA, Andreasen NC, Vázquez-Barquero JL (2007) Reduced thalamic volume in first-episode non-affective psychosis: correlations with clinical variables, symptomatology and cognitive functioning. NeuroImage 35, 1613–1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crespo-Facorro B, Roiz-Santiáñez R, Pérez-Iglesias R, Tordesillas-Gutiérrez D, Mata I, Rodríguez-Sánchez JM, de Lucas EM, Vázquez-Barquero JL (2009) Specific brain structural abnormalities in first-episode schizophrenia. A comparative study with patients with schizo- phreniform disorder, non-schizophrenic non-affective psychoses and healthy volunteers. Schizophrenia Research 115, 191–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Peri L, Crescini A, Deste G, Fusar-Poli P, Sacchetti E, Vita A (2012) Brain structural abnormalities at the onset of schizophrenia and bipolar dis- order: a meta-analysis of controlled magnetic resonance imaging studies. Current Pharmaceutical Design 18, 486–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeRosse P, Karlsgodt KH (2015) Examining the psychosis continuum. Current Behavioral Neuroscience Reports 2, 80–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson D, Iannone VN, Gold JM (2002) Factor structure of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-III in schizophrenia. Assessment 9, 171–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson D, Ragland JD, Calkins ME, Gold JM, Gur RC (2006) A compari- son of cognitive structure in schizophrenia patients and healthy controls using confirmatory factor analysis. Schizophrenia Research 85, 20–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Díez Á, Suazo V, Casado P, Martín-Loeches M, Molina V, Díez A, Suazo V, Casado P, Martín-Loeches M, Molina V (2013) Spatial distribution and cognitive correlates of gamma noise power in schizophrenia. Psychological Medicine 43, 1175–1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong C, Nabizadeh N, Caunca M, Cheung YK, Rundek T, Elkind MSV, DeCarli C, Sacco RL, Stern Y, Wright CB (2015a). Cognitive correlates of white matter lesion load and brain atrophy: the Northern Manhattan Study. Neurology 85, 441–449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong S, Reder LM, Yao Y, Liu Y, Chen F (2015b). Individual differences in working memory capacity are reflected in different ERP and EEG patterns to task difficulty. Brain Research 1616, 146–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorph-Petersen K-A, Pierri JN, Perel JM, Sun Z, Sampson AR, Lewis DA (2005) The influence of chronic exposure to antipsychotic medications on brain size before and after tissue fixation: a comparison of haloperidol and olanzapine in macaque monkeys. Neuropsychopharmacology: Official Publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology 30, 1649–1661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutt A, McDonald C, Dempster E, Prata D, Shaikh M, Williams I, Schulze K, Marshall N, Walshe M, Allin M, Collier D, Murray R, Bramon E (2009) The effect of COMT, BDNF, 5-HTT, NRG1 and DTNBP1 genes on hippocampal and lateral ventricular volume in psych- osis. Psychological Medicine 39, 1783–1797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endicott J, Spitzer RL (1978) A diagnostic interview. The schedule for affect- ive disorders and schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry 35, 837–844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esterberg ML, Compton MT (2009) The psychosis continuum and categorical versus dimensional diagnostic approaches. Current Psychiatry Reports 11, 179–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fannon D, Tennakoon L, Sumich A, O’Ceallaigh S, Doku V, Chitnis X, Lowe J, Soni W, Sharma T (2000) Third ventricle enlargement and devel- opmental delay in first-episode psychosis: preliminary findings. The British Journal of Psychiatry 177, 354–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatouros-Bergman H, Cervenka S, Flyckt L, Edman G, Farde L (2014) Meta-analysis of cognitive performance in drug-naïve patients with schizo- phrenia. Schizophrenia Research 158, 156–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fjell AM, Walhovd KB (2001) P300 and neuropsychological tests as measures of aging: scalp topography and cognitive changes. Brain Topography 14, 25–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes NF, Carrick LA, McIntosh AM, Lawrie SM (2009) Working memory in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine 39, 889–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford JM (2014) Decomposing P300 to identify its genetic basis. Psychophysiology 51, 1325–1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraguas D, Díaz-Caneja CM, Pina-Camacho L, Janssen J, Arango C (2016) Progressive brain changes in children and adolescents with early-onset psychosis: a meta-analysis of longitudinal MRI studies. Schizophrenia Research 173, 132–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frangou S, Sharma T, Sigmudsson T, Barta P, Pearlson G, Murray RM (1997) The Maudsley Family Study. 4. Normal planum temporale asym- metry in familial schizophrenia. A volumetric MRI study. The British Journal of Psychiatry 170, 328–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fusar-Poli P, Deste G, Smieskova R, Barlati S, Yung AR, Howes O, Stieglitz R-D, Vita A, McGuire P, Borgwardt S (2012) Cognitive function- ing in prodromal psychosis: a meta-analysis. American Medical Association. Archives of General Psychiatry 69, 562–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fusar-Poli P, Smieskova R, Kempton MJ, Ho BC, Andreasen NC, Borgwardt S (2013) Progressive brain changes in schizophrenia related to antipsychotic treatment? A meta-analysis of longitudinal MRI studies. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 37, 1680–1691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geschwind DH, Flint J (2015) Genetics and genomics of psychiatric disease.Science 349, 1489–1494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gladsjo JA, McAdams LA, Palmer BW, Moore DJ, Jeste DV, Heaton RK (2004) A six-factor model of cognition in schizophrenia and related psych- otic disorders: relationships with clinical symptoms and functional capacity. Schizophrenia Bulletin 30, 739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glahn DC, Bearden CE, Cakir S, Barrett JA, Najt P, Serap Monkul E, Maples N, Velligan DI, Soares JC (2006) Differential working memory impairment in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia: effects of lifetime history of psychosis. Bipolar Disorders 8, 117–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gogtay N, Sporn A, Clasen LS, Greenstein D, Giedd JN, Lenane M, Gochman PA, Zijdenbos A, Rapoport JL (2003) Structural brain MRI abnormalities in healthy siblings of patients with childhood-onset schizo- phrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 160, 569–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Blanch C, Crespo-Facorro B, Álvarez-Jiménez M, Rodríguez-Sánchez JM, Pelayo-Terán JM, Pérez-Iglesias R, Vázquez-Barquero JL (2007) Cognitive dimensions in first-episode schizo- phrenia spectrum disorders. Journal of Psychiatric Research 41, 968–977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodin DS, Squires KC, Henderson BH, Starr A (1978) Age-related varia- tions in evoked potentials to auditory stimuli in normal human subjects. Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology 44, 447–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottesman II, Gould TD (2003) The endophenotype concept in psychiatry: etymology and strategic intentions. American Journal of Psychiatry 160, 636–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratten J, Wray NR, Keller MC, Visscher PM (2014) Large-scale genomics unveils the genetic architecture of psychiatric disorders. Nature Research. Nature Neuroscience 17, 782–790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green EK, Rees E, Walters JTR, Smith K-G, Forty L, Grozeva D, Moran JL, Sklar P, Ripke S, Chambert KD, Genovese G, McCarroll SA, Jones I, Jones L, Owen MJ, O’Donovan MC, Craddock N, Kirov G (2015) Copy number variation in bipolar disorder. Macmillan Publishers Limited. Molecular Psychiatry 21, 89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grozeva D, Conrad DF, Barnes CP, Hurles M, Owen MJ, O’Donovan MC, Craddock N, Kirov G (2011) Independent estimation of the frequency of rare CNVs in the UK population confirms their role in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research 135, 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gur RE, Calkins ME, Gur RC, Horan WP, Nuechterlein KH, Seidman LJ, Stone WS (2007) The consortium on the genetics of schizophrenia: neuro- cognitive endophenotypes. Schizophrenia Bulletin 33, 49–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gur RERCRE Braff DL, Calkins ME Dobie DJ, Freedman R Green MF, Greenwood TA Lazzeroni LC, Light GA Nuechterlein KH, Olincy A Radant AD, Seidman LJ, Siever LJ, Silverman JM, Sprock J, Stone WS, Sugar CA, Swerdlow NR, Tsuang DW, Tsuang MT, Turetsky BI, Gur RERCRE (2015) Neurocognitive performance in family-based and case-control studies of schizophrenia. Elsevier B.V. Schizophrenia Research 163, 17–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habets P, Marcelis M, Gronenschild E, Drukker M, Van Os J (2011) Reduced cortical thickness as an outcome of differential sensitivity to envir- onmental risks in schizophrenia. Biological Psychiatry 69, 487–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haijma SV, Van Haren N, Cahn W, Koolschijn PCMP, Hulshoff Pol HE, Kahn RS (2013) Brain volumes in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis in over 18 000 subjects. Schizophrenia Bulletin 39, 1129–1138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall M-H, Levy DL, Salisbury DF, Haddad S, Gallagher P, Lohan M, Cohen B, Öngür D, Smoller JW, Ongür D, Smoller JW (2014) Neurophysiologic effect of GWAS derived schizophrenia and bipolar risk variants. American Journal of Medical Genetics. Part B, Neuropsychiatric Genetics 165B, 9–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall MH, Schulze K, Bramon E, Murray RM, Sham P, Rijsdijk F (2006a). Genetic overlap between P300, P50, and duration mismatch negativity. American Journal of Medical Genetics, Part B: Neuropsychiatric Genetics 141, 336–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall MH, Schulze K, Rijsdijk F, Picchioni M, Ettinger U, Bramon E, Freedman R, Murray RM, Sham P (2006b). Heritability and reliability of P300, P50 and duration mismatch negativity. Kluwer Academic Publishers-Plenum Publishers. Behavior Genetics 36, 845–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall MH, Smoller JW (2010) A new role for endophenotypes in the GWAS era: functional characterization of risk variants. Harvard Review Psychiatry 18, 67–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison PJ (2015) Recent genetic findings in schizophrenia and their therapeutic relevance. Journal of Psychopharmacology (Oxford, England) 29, 85–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartberg CB, Sundet K, Rimol LM, Haukvik UK, Lange EH, Nesvåg R, Melle I, Andreassen OA, Agartz I (2011) Subcortical brain volumes relate to neurocognition in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder and healthy con- trols. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry 35, 1122–1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrichs RW, Zakzanis KK (1998) Neurocognitive deficit in schizophrenia: a quantitative review of the evidence. Neuropsychology 12, 426–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermens DF, Ward PB, Hodge MAR, Kaur M, Naismith SL, Hickie IB (2010) Impaired MMN/P3a complex in first-episode psychosis: cognitive and psychosocial associations. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry 34, 822–829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heslenfeld DJ (2003) Visual mismatch negativity In Detection of Change: Event-Related Potential and fMRI Findings (ed. Polich J), pp. 41–59.Springer US: Boston. [Google Scholar]

- Ho B-C, Andreasen NC, Ziebell S, Pierson R, Magnotta V (2011) Long-term antipsychotic treatment and brain volumes: a longitudinal study of first- episode schizophrenia. American Medical Association. Archives of General Psychiatry 68, 128–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horan WP, Braff DL, Nuechterlein KH, Sugar CA, Cadenhead KS, Calkins ME, Dobie DJ, Freedman R, Greenwood TA, Gur RE, Gur RC, Light GA, Mintz J, Olincy A, Radant AD, Schork NJ, Seidman LJ, Siever LJ, Silverman JM, Stone WS, Swerdlow NR, Tsuang DW, Tsuang MT, Turetsky BI, Green MF (2008) Verbal working memory impairments in individuals with schizophrenia and their first- degree relatives: findings from the consortium on the genetics of schizo- phrenia. Schizophrenia Research 103, 218–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huhtaniska S, Jääskeläinen E, Hirvonen N, Remes J, Murray GK, Veijola J, Isohanni M, Miettunen J (2017) Long-term antipsychotic use and brain changes in schizophrenia – a systematic review and meta-analysis. Human Psychopharmacology: Clinical and Experimental 32, e2574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulshoff Pol HE, Schnack HG, Bertens MGBC, van Haren NEM, van der Tweel I, Staal WG, Baaré WFC, Kahn RS (2002) Volume changes in gray matter in patients with schizophrenia. The American Journal of Psychiatry 159, 244–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ian K, Jenner JA, Cannon M (2010) Psychotic symptoms in the general popu- lation – an evolutionary perspective. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science 197, 167–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivleva EI, Morris DW, Osuji J, Moates AF, Carmody TJ, Thaker GK, Cullum M, Tamminga CA (2012) Cognitive endophenotypes of psychosis within dimension and diagnosis. Elsevier B.V. Psychiatry Research 196, 38–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasper H (1958) Report to the committee on methods of clinical examination in electroencephalography. Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology 10, 371–375. [Google Scholar]

- Johns LC, van Os J (2001) The continuity of psychotic experiences in the gen- eral population. Clinical Psychology Review 21, 1125–1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnstone EC, Ebmeier KP, Miller P, Owens DGC, Lawrie SM (2005) Predicting schizophrenia: findings from the Edinburgh High-Risk Study. The British Journal of Psychiatry 186, 18–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur M, Battisti RA, Ward PB, Ahmed A, Hickie IB, Hermens DF (2011) MMN/p3a deficits in first episode psychosis: comparing schizophrenia-spectrum and affective-spectrum subgroups. Elsevier B.V. Schizophrenia Research 130, 203–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keilp JG, Sweeney JA, Jacobsen P, Solomon C, Louis L St, Deck M, Frances A, Mann JJ (1988) Cognitive impairment in schizophrenia: specific relations to ventricular size and negative symptomatology. Biological Psychiatry 24, 47–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kempton MJ, Stahl D, Williams SCR, DeLisi LE (2010) Progressive lateral ventricular enlargement in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of longitudinal MRI studies. Schizophrenia Research 120, 54–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D, Kim J, Koo T, Yun H, Won S (2015a). Shared and distinct neurocog- nitive endophenotypes of schizophrenia and psychotic bipolar disorder. Clinical Psychopharmacology and Neuroscience 13, 94–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M, Seo H-J, Yun H, Jung Y-E, Park JH, Lee C-I, Moon JH, Hong S-C, Yoon B-H, Bahk W-M (2015b). The relationship between cognitive decline and psychopathology in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Clinical Psychopharmacology and Neuroscience 13, 103–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M-S, Kang S-S, Youn T, Kang D-H, Kim J-J, Kwon JS (2003) Neuropsychological correlates of P300 abnormalities in patients with schizophrenia and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging 123, 109–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konopaske GT, Dorph-Petersen KA, Pierri JN, Wu Q, Sampson AR, Lewis DA (2007) Effect of chronic exposure to antipsychotic medication on cell numbers in the parietal cortex of macaque monkeys. Neuropsychopharmacology 32, 1216–1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korver N, Quee PJ, Boos HBM, Simons CJP, de Haan L (2012) Genetic Risk and Outcome of Psychosis (GROUP), a multi site longitudinal cohort study focused on gene-environment interaction: objectives, sample characteristics, recruitment and assessment methods. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 21, 205–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kujala A, Naatanen R (2003) Auditory environment and change detection as indexed by the mismarch gegativity (MMN) In Detection of Change: Event-Related Potential and fMRI Findings (ed. Polich J), pp. 1–22. Springer US: Boston. [Google Scholar]

- Kumra S, Giedd JN, Vaituzis AC, Jacobsen LK, McKenna K, Bedwell J, Hamburger S, Nelson JE, Lenane M, Rapoport JL (2014) Childhood-onset psychotic disorders: magnetic resonance imaging of volu- metric differences in brain structure. American Journal of Psychiatry 157, 1467–1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Green MF, Calkins ME, Greenwood TA, Gur RERC, Gur RERC, er LJ, Silverman JM, Sprock J, Stone WS, Sugar CA, Swerdlow NR, Tsuang DW, Tsuang MT, Turetsky BI, Braff DL(2015) Verbal working memory in schizophrenia from the Consortium on the Genetics of Schizophrenia (COGS) Study: the moderating role of smoking status and antipsychotic medications. Elsevier. Schizophrenia Research 163, 24–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SH, Ripke S, Neale BM, Faraone SV, Purcell SM, Perlis RH, Mowry BJ, Thapar A, Goddard ME, Witte JS, Absher D, Agartz I, Akil H, Amin F, Andreassen OA, Anjorin A, Anney R, Anttila V, Arking DE, Asherson P, Azevedo MH, Backlund L, Badner JA, Bailey AJ, Banaschewski T, Barchas JD, Barnes MR, Barrett TB, Bass N, Battaglia A, Bauer M, Bayés M, Bellivier F, Bergen SE, Berrettini W, Betancur C, Bettecken T, Biederman J, Binder EB, Black DW, Blackwood DHR, Bloss CS, Boehnke M, Boomsma DI, Breen G, Breuer R, Bruggeman R, Cormican P, Buccola NG, Buitelaar JK, Bunney WE, Buxbaum JD, Byerley WF, Byrne EM, Caesar S, Cahn W, Cantor RM, Casas M, Chakravarti A, Chambert K, Choudhury K, Cichon S, Cloninger CR, Collier DA, Cook EH, Coon H, Cormand B, Corvin A, Coryell WH, Craig DW, Craig IW, Crosbie J, Cuccaro ML, Curtis D, Czamara D, Datta S, Dawson G, Day R, De Geus EJ, Degenhardt F, Djurovic S, Donohoe GJ, Doyle AE, Duan J, Dudbridge F, Duketis E, Ebstein RP, Edenberg HJ, Elia J, Ennis S, Etain B, Fanous A, Farmer AE, Ferrier IN, Flickinger M, Fombonne E, Foroud T, Frank J, Franke B, Fraser C, Freedman R, Freimer NB, Freitag CM, Friedl M, Frisén L, Gallagher L, Gejman PV, Georgieva L, Gershon ES, Geschwind DH, Giegling I, Gill M, Gordon SD, Gordon Smith K, Green EK, Greenwood TA, Grice DE, Gross M, Grozeva D, Guan W, Gurling H, De Haan L, Haines JL, Hakonarson H, Joachim Hallmayer J, Hamilton SP, Hamshere ML, Hansen TF, Hartmann AM, Hautzinger M, Heath AC, Henders AK, Herms S, Hickie IB, Hipolito M, Hoefels S, Holmans PA, Holsboer F, Hoogendijk WJ, Hottenga JJ, Hultman CM, Hus V, Ingason A, Ising M, Jamain S, Jones EG, Jones I, Jones L, Jung-Ying T, Kähler AK, Kahn RS, Kandaswamy R, Keller MC, Kennedy JL, Kenny E, Kent L, Kim Y, Kirov GK, Klauck SM, Klei L, Knowles JA, Kohli MA, Koller DL, Konte B, Korszun A, Krabbendam L, Krasucki R, Kuntsi J, Kwan P, Landén M, Långström N, Lathrop M, Lawrence J, Lawson WB, Leboyer M, Ledbetter DH, Hyoun Lee P, Lencz T, Lesch KP, Levinson DF, Lewis CM, Li J, Lichtenstein P, Lieberman JA, Lin DY, Linszen DH, Liu C, Lohoff FW, Loo SK, Lord C, Lowe JK, Lucae S, MacIntyre DJ, Madden PAF, Maestrini E, Magnusson PKE, Mahon PB, Maier W, Malhotra AK, Mane SM, Martin CL, Martin NG, Mattheisen M, Matthews K, Mattingsdal M, McCarroll SA, McGhee KA, McGough JJ, McGrath PJ, McGuffin P, McInnis MG, McIntosh A, McKinney R, McLean AW, McMahon FJ, McMahon WM, McQuillin A, Medeiros H, Medland SE, Meier S, Melle I, Meng F, Meyer J, Middeldorp CM, Middleton L, Milanova V, Miranda A, Monaco AP, Montgomery GW, Moran JL, Moreno-De-Luca D, Morken G, Morris DW, Morrow EM, Moskvina V, Muglia P, Mühleisen TW, Muir WJ, Müller-Myhsok B, Murtha M, Myers RM, Myin-Germeys I, Neale MC, Nelson SF, Nievergelt CM, Nikolov I, Nimgaonkar V, Nolen WA, Nöthen MM, Nurnberger JI, Nwulia EA, Nyholt DR, O’Dushlaine C, Oades RD, Ann Olincy A, Guiomar Oliveira G, Olsen L, Ophoff RA, Osby U, Owen MJ, Palotie A, Parr JR, Paterson AD, Pato CN, Pato MT, Penninx BW, Pergadia ML, Pericak-Vance MA, Pickard BS, Pimm J, Piven J, Posthuma D, Potash JB, Poustka F, Propping P, Puri V, Quested DJ, Quinn EM, Ramos-Quiroga JA, Rasmussen HB, Raychaudhuri S, Rehnström K, Reif A, Ribasés M, Rice JP, Rietschel M, Roeder K, Roeyers H, Rossin L, Rothenberger A, Rouleau G, Ruderfer D, Rujescu D, Sanders AR, Sanders SJ, Santangelo S, Sargeant JA, Schachar R, Schalling M, Schatzberg AF, Scheftner WA, Schellenberg GD, Scherer SW, Schork NJ, Schulze TG, Schumacher J, Schwarz M, Scolnick E, Scott LJ, Shi J, Shilling PD, Shyn SI, Silverman JM, Slager SL, Smalley SL, Smit JH, Smith EN, Sonuga-Barke EJS, St Clair D, State M, Steffens M, Steinhausen HC, Strauss JS, Strohmaier J, Stroup TS, Sutcliffe J, Szatmari P, Szelinger S, Thirumalai S, Thompson RC, Todorov AA, Tozzi F, Treutlein J, Uhr M, van den Oord EJCG, Van Grootheest G, Van Os J, Vicente AM, Vieland VJ, Vincent JB, Visscher PM, Walsh CA, Wassink TH, Watson SJ, Weissman MM, Werge T, Wienker TF, Wiersma D, Wijsman EM, Willemsen G, Williams N, Willsey AJ, Witt SH, Xu W, Young AH, Yu TW, Zammit S, Zandi PP, Zhang P, Zitman FG, Zöllner S, International Inflammatory Bowel Disease Genetics Consortium (IIBDGC), Devlin B, Kelsoe JR, Sklar P, Daly MJ, O’Donovan MC, Craddock N, Sullivan PF, Smoller JW, Kendler KS, Wray NR (2013) Genetic relationship between five psychiatric disorders estimated from genome-wide SNPs. Nature Genetics 45, 984–994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Light GA, Swerdlow NR, Thomas ML, Calkins ME, Green MF, Greenwood TA, Gur RE, Gur RC, Lazzeroni LC, Nuechterlein KH, Pela M, Radant AD, Seidman LJ, Sharp RF, Siever LJ, Silverman JM, Sprock J, Stone WS, Sugar CA, Tsuang DW, Tsuang MT, Braff DL, Turetsky BI (2015) Validation of mismatch negativity and P3a for use in multi-site studies of schizophrenia: characterization of demographic, clin- ical, cognitive, and functional correlates in COGS-2. Elsevier B.V. Schizophrenia Research 163, 63–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massuda R, Bücker J, Czepielewski LS, Narvaez JC, Pedrini M, Santos BT, Teixeira AS, Souza AL, Vasconcelos-Moreno MP, Vianna-Sulzbach M, Goi PD, Belmonte-de-Abreu P, Gama CS (2013) Verbal memory impairment in healthy siblings of patients with schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research 150, 580–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mata I, Perez-Iglesias R, Roiz-Santiañez R, Tordesillas-Gutierrez D, Gonzalez-Mandly A, Vazquez-Barquero JL, Crespo-Facorro B (2009) A neuregulin 1 variant is associated with increased lateral ventricle volume in patients with first-episode schizophrenia. Society of Biological Psychiatry. Biological Psychiatry 65, 535–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald C, Grech A, Toulopoulou T, Schulze K, Chapple B, Sham P, Walshe M, Sharma T, Sigmundsson T, Chitnis X, Murray RM (2002) Brain volumes in familial and non-familial schizophrenic probands and their unaffected relatives. American Journal of Medical Genetics 114, 616–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald C, Marshall N, Sham PC, Bullmore ET, Schulze K, Chapple B, Bramon E, Filbey F, Quraishi S, Walshe M, Murray RM (2006) Regional brain morphometry in patients with schizophrenia or bipolar dis- order and their unaffected relatives. The American Journal of Psychiatry 163, 478–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]