Abstract

Significant efforts have been made to treat bone disorders through the development of composite scaffolds utilizing calcium phosphate (CaP) through additive manufacturing techniques. However, the incorporation of natural polymers with CaP during 3D printing is difficult and remains a formidable challenge in bone and tissue engineering applications. The objective of this study is to understand the use of a natural polymer binder system in ceramic composite scaffolds using a ceramic slurry-based solid freeform fabricator (SFF). This was achieved through the utilization of naturally sourced gelatinized starch with hydroxyapatite (HA) ceramic in order to obtain high mechanical strength and enhanced biological properties of the green part without the need for cross-linking or post processing. The parametric effects of solids loading, polycaprolactone (PCL) polymer addition, and designed porosity on starch-HA composite scaffolds were assessed through mechanical strength, microstructure, and in vitro biocompatibility utilizing human osteoblast cells. It was hypothesized that starch incorporation would improve the mechanical strength of the scaffolds and increase proliferation of osteoblast cells in vitro. Starch loading was shown to improve mechanical strength from 4.07 ± 0.66 MPa to 10.35 ± 1.10 MPa, more closely resembling the mechanical strength of cancellous bone. Based on these results, a reinforcing mechanism of gelatinized starch based on interparticle and apatite crystal interlocking is proposed. Morphological characterization utilizing FESEM and MTT cell viability assay showed enhanced osteoblast cell proliferation in the presence of starch and PCL. Overall, the utilization of starch as a natural binder system in SFF scaffolds was found to improve both green strength and in vitro biocompatibility.

Keywords: Solid Freeform Fabrication (SFF), Natural polymers, Starch, Hydroxyapatite (HA), Scaffolds, Bone and tissue engineering

Graphical abstract:

a) Ceramic slurry preperation of starch and hydroxyapaitite (HA) utilized for fabrication of bone scaffolds without the need for post processing. b) Schematic of Solid Freeform Fabricator. c) Reprensentation of scaffold model utilizing solidworks file and CURA program and final scaffold prints d) In vitro cell work regarding the proliferation of osteoblast cells utilizing starch based composite HA scaffolds, ultimately aquiring sufficient mechanical integrity and enhanced biactivity to be utilized in bone repair.

1. Introduction

Millions of people suffer every year from bone defects due to tumor onset, trauma, or bone related diseases [1]. Major advances in bone tissue engineering have led to the development of bioresorbable scaffolds in order to enhance bone formation and vascularization. Bone scaffolds are implanted where bone is damaged or missing, which will initially provide both a physical and chemical means for new bone formation to take place. As the body naturally heals, the scaffold slowly breaks down, deteriorates, and is absorbed and replaced by the physiological environment with new bone growth. New developments in 3D printed scaffolds are being researched in order to provide suitable mechanical and biological environments to promote osteoblast proliferation and osteogenesis [2-4].

Traditional scaffold fabrication methodologies including solvent casting and particle leaching pose many challenges in the creation of bioresorbable scaffolds, including the utilization of toxic organic solvents, long fabrication times, and incomplete removal of residual particles and agents within the polymer matrix, among other challenges [5]. New additive manufacturing techniques have been developed to mitigate these challenges, including Solid Freeform Fabrication (SFF), robocasting, and nScrypt [6]. SFF is the production of a solid object directly from a computer model without the need for tooling or human intervention [7]. Recent work has been directed towards the development of ceramic composite SFF structures with the aim of combining enhanced biological properties through controlled, reproducible, and customizable architecture, particularly in the field of bone and tissue engineering [8]. This includes the utilization of slurry-based SFF techniques in order to print ceramic materials [9].

Hydroxyapatite (HA) has been widely investigated as a biocompatible and osteoconductive biomaterial [10]. HA, although a common bone construct, is hard and brittle, which limits its utilization in load bearing applications as well as its manufacturing into complex shapes and manipulation into defect specific sites [11, 12]. To overcome these challenges, HA can be combined with natural polymers to create composite scaffolds. Natural biomaterial usage has gained impetus in the biomedical field due to its biocompatibility and chemical stability, particularly in wound management, drug delivery, and tissue engineering applications. While promising, natural products as materials possess major limitations due to their immunogenic response, variability, and incapability to be incorporated into traditional processing techniques, particularly those that require high temperatures [13].

Starch-based biomaterials have been among several scaffold compositions proposed for biomedical applications. Previously, drug delivery and hydrogel systems remain the standard application for starch as a biomedical material [3, 14, 15]. Like most natural polymers, starch can guide cellular growth and development due to its highly organized structure [16]. Preliminary studies show that the utilization of starch in the preparation of bone cements and scaffold design requires the implementation of other conjugated polymers, such as dextran and gelatin in the binder phase, with post processing methodology in order to enhance the mechanical and chemical properties of these scaffolds [17, 18]. In these studies, ceramic powder particles are bonded based on the deposition of a naturally sourced binder resin. Other studies on natural materials utilizing SFF implement chitosan and chitosan/HA composites [19, 20]. The characterization of slurries with starch binder systems have shown high viscosity and excellent stability, but poor solids loading and packing fraction compared to other binders such as PVA and latex make them difficult to process using advanced additive manufacturing techniques [21]. Other binder preparations have combined starch with cellulose acetate blends and PCL acetate blends through complicated polymerization methods [17]. Weaknesses attributed to starch include its high water uptake and low mechanical strength depending on the source, where compressive strengths have been reported as low as 4 MPa [2].

Additive manufacturing methods such as SFF have led to the advancement of new composite scaffold systems which have overcome many drawbacks to bulk ceramic structures. However, many limitations still exist regarding the addition of naturally sourced polymeric materials in current 3D printing technologies. Synthetic polymer incorporation in SFF ceramic structures have shown high biocompatibility, porosity, and mechanical viability but little has been studied regarding the implementation of natural polymers [22]. The objective of this study is to understand the implementation of a natural polymer binder system in ceramic composite scaffolds using a ceramic slurry-based SFF. The parametric effects of solids loading, polycaprolactone (PCL) polymer addition, and designed porosity on starch-HA composite scaffolds were assessed through mechanical strength, microstructure, and in vitro biocompatibility utilizing human osteoblast cells. It was hypothesized that starch incorporation would improve the mechanical strength of the scaffolds and increase proliferation of osteoblast cells in vitro.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Design of ceramic slurry SFF

The print head module of the ceramic slurry SFF was designed with overall dimensions of 244 mm height × 88 mm length × 94 mm width and mounted on a gantry of a conventional 3D printer (Figure 1b and 1c). This module works on the principle of positive displacement, driven by a lead screw linear actuator system, as shown in Figure 1a. A standard Nema 17 stepper motor with holding torque of 64oz-in (45Ncm) is coupled to a gear train with gear ratio 1:5, with the addition of a double helical gear teeth profile to minimize backlash. In order to withstand high pressure, the piston-cylinder unit is made from high strength polycarbonate material and stainless steel. The stroke of the piston is 62 mm, and cylinder bore 23 mm. The cylinder has a nozzle lock mechanism on which several nozzles with diameters ranging from 0.5 mm to 0.9 mm can be attached.

Figure 1.

a) Solidworks linear actuator system. b) Schematic of Ceramic 3D Printer c) Print-head assembly (Design), and the print-head mounted on a conventional 3D printer gantry (TAZ 5).

The extruder motor (Nema 17 stepper motor) through the drive train impacts a high torque on the lead screw and a corresponding linear force on the traveling block which slides on a guide rail. This axial force is exacted on the piston-cylinder unit on which the ceramic slurry is loaded, and a bead of ceramic slurry is deposited via the nozzle on the build bed. Figure 1a shows the SolidWorks model of the ceramic slurry print head, and Figures 1b and c show the schematic and fabricated print head assembly mounted on a conventional 3D printer gantry (Lulzbot TAZ 5). The control system of the print head assembly is based on the gantry’s three axis motion (X, Y, Z) that is controlled through Cura software. The control program was modified and optimized during test operations. Processing program parameters include machine setting (E-steps/1 mm filament) which specifies the extruder motor speed, the layer height (mm) which defines the distance z-axis moves during each layer deposition, the fill density (%) which specifies the hatch distance between each layer and defines the processing porosity, the printing speed (mm/s) which specifies the speed for the x-y axes movement, and the flow (%) which defines the multiplying factor of the extruder speed.

The fabrication process of a ceramic scaffold from the ceramic slurry is based on layer-by-layer deposition of the slurry bead which cures with little or no deformation to hold successive ceramic layers. A complete understanding of the slurry rheology is critical, and process parameters were coordinated based on the ceramic slurry characteristic behavior in order to achieve a quality build.

2.2. Raw materials and powders

All composite scaffolds built utilized a similar starch binder system that was processed from commercial corn starch (Great Value) and commercial grade HA powder (Monsanto, USA). Polycaprolactone pellets (PCL, MW 14,000, Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) were also used to create two of the scaffold preparations. Acetone (J.T. Baker, Phillipsburg, NJ) and deionized water were also used during slurry preparation.

2.3. Ceramic slurry

2.3.1. Preparation

An optimized ceramic slurry with gelatinized corn starch was first prepared and used to optimize the parameters of the 3D printer as described in Table I. This procedure involves the dissolution of a starch in cold water, where boiling water is then added to create gelatinized starch. Varying amounts of starch slurry were then added to milled Monsanto commercial-grade HA powder to create compositions 1 and 2, corresponding to low and high HA solids loading preparations, with PCL addition and designed porosity as further parameters for each composition, as described in Figure 2. The ceramic powder was prepared by ball milling 6-8 hours with 2:1 ball ratio in ethanol, where the mixture was left to dry for 12 hours and sieved through a 212 mm sieve. Further scaffold slurry preparations involved the incorporation of PCL. A 5% PCL solution dissolved in acetone was obtained utilizing a 60 °C water bath. This solution was added to DI water and commercial corn starch, and then gelatinized and utilized in compositions 1 and 2. Final slurry compositions are given in Table I by weight percent of each component.

Table I.

Composition and printing parameters for slurries

| Composition | Composition 1 |

Composition 2 |

Composition 1 with PCL |

Composition 2 with PCL |

Composition 1 with designed porosity |

Composition 2 with designed porosity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Composition in wt% | 37.7 wt% HA 5.1 wt% corn starch 57.2 wt% water |

54 wt% HA 3.8 wt% corn starch 42.2 wt% water |

37.7 wt% HA 5.1 wt% corn starch 54.6 wt% water 2.6 wt% PCL (5% in acetone) |

52 wt% HA 3.93 wt% corn starch 1.97% (5% PCL/acetone) 42.1 wt% water |

37.7 wt% HA 5.1 wt% corn starch 57.2 wt% water |

54 wt% HA 3.8 wt% corn starch 42.2 wt% water |

| Nozzle Diameter (mm) | 0.7 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.9 |

| Print Speed (mm/s) | 40 | 40 | 40 | 70 | 70 | 40 |

| Fill Density (%) | 40 | 40 | 40 | 30 | 24 | 22 |

| Flow % | 70 | 70 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 67 |

| Layer Height (mm) | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 |

Figure 2.

Parameters tested for scaffold preparation utilizing natural polymer binder system

2.3.2. Characterization of ceramic slurry preparations:

The density of each ceramic slurry composition was calculated by loading the slurry in a graduated syringe and measuring its mass and volume. The extrusion rate of each slurry was measured based on the amount of material extruded through the nozzle over a specific period of time. Extrusion rate was also measured based on volume flow rate, where an initial layer of the scaffold was printed and timed, and the diameter of the cross section and programed layer height were measured. At each process parameter combination and slurry preparation, these measurements were performed in triplicate (n = 3).

2.4. SFF ceramic composite scaffolds

2.4.1. Preparation

Approximately 45 g of the final ceramic slurry was added to the printer piston. Printer parameters were optimized based on a 0.7 and 0.9 mm nozzle for low and high solids loading compositions, with layer height of 1.5 mm, shell thickness of 0.5 mm, and initial thickness of 0 mm. Operating program parameters were optimized for each composition with and without PCL and designed porosity. Infill and printing speeds were varied from 40-70% as well as 40-70 mm/s respectively depending on the viscosity of the ceramic slurry and the amount of designed porosity of the scaffold. These parameters are shown in Table I. Scaffold were designed with a 1.5-2 height to diameter ratio. The scaffold was designed in Solidworks at a height of 20 mm and a diameter of 11 mm.

2.4.2. Characterization of composite scaffolds

Three samples were prepared separately for apparent density, bulk density, and mechanical evaluation for each process parameter combination. Bulk density of the samples was determined by measuring the physical dimensions and the mass of the samples. Since the diameter of the scaffolds was not even throughout the preparation due to layer loading and swelling, the top and bottom diameters of the scaffold were averaged. Apparent density was measured in ethanol using Archimedes principle. Bulk and apparent densities were utilized in order to calculate fraction of open and closed pores. Open porosity was taken as the programmed fill density.

X-ray diffraction (XRD) methodology was performed on HA starch scaffold preparations and milled HA for phase analysis with a Siemens D-500 Diffractometer system operating at 35.0 kV and 30.0 mA with a Cu and Co Kα radiation and Ni filter at a scan rate of 0.02°s−1. Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra of samples were obtained using an ATR-FTIR spectrophotometer (Nicolet 6700 FTIR, Madison, WI, USA) in the 400–4000 cm−1 wave number range.

Images for surface morphology of horizontal and vertical cross sections of dense and porous HA starch scaffolds were taken using a field-emission scanning electron microscope (FESEM) (FEI Inc., Hillsboro, OR, USA) and gold sputter-coating (Technics Hummer V, CA, USA). Horizontal and vertical cross sections were prepared utilizing a mini hack saw blade (6’ length, 24 T.P.I) and hand vice. Optical images were also obtained for cross sectioned compositions 1 and 2 with designed porosity.

Compressive strength analysis was performed to compare the mechanical properties between low and high solids loading scaffolds with and without the addition of PCL or porosity. Compressive strengths of the scaffolds were measured using a screw-driven universal testing machine (AG-IS, Shimadzu, Tokyo, Japan) with a constant crosshead speed of 0.33 mm/min, and the calculation was performed based on the maximum load at failure and initial scaffold dimensions. Three samples (n = 3) were used from each composition for compressive strength analysis.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Data is presented as mean ± standard deviation and statistical analysis was performed on compressive strength results using student’s t-test, where a p value <0.05 was considered significant.

2.6. In vitro cell material interactions

2.6.1. Osteoblast cell culture

For the cell culture study, all starch-based samples were cross-sectioned horizontally and sterilized in 100% ethanol for 1 hour and placed under UV for 2 hours. Pure HA samples were prepared utilizing a three-step sintering process, where samples were heated up to 1250 °C. All samples were then moved to a biosafety cabinet. Sample composition and properties utilized for cell culture are given in Table II.

Table II.

Compositions prepared for in vitro osteoblast cell culture study

| Composition Name |

Composition weight percentage |

Average Mass (g) |

Average Diameter (mm) |

Average Height (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pure HA | 100% HA | 0.66 ± 0.01 | 0.66 ± 0.02 | 2.95 ± 0.13 |

| Composition 1 | 37.7 wt% HA 5.1 wt% corn starch 57.2 wt% water |

0.54 ± 0.07 | 12.00 ± 0.37 | 4.22 ±0.42 |

|

Composition 1 +PCL |

37.7 wt% HA 5.1 wt% corn starch 54.6 wt% water 2.6 wt% PCL (5% inacetone) |

0.48 ± 0.03 | 11.27 ±0.26 | 4.26 ± 0.25 |

| Composition 2 | 54 wt% HA 3.8 wt% corn starch 42.2 wt% water |

0.87 ± 0.06 | 13.80 ± 0.38 | 5.06 ± 0.39 |

Human fetal osteoblast cells (hFOB 1.19, ATCC, Manassas, VA) were grown to passage 7 and were then seeded to samples at a density of 20×103 cells/sample. The basal medium was prepared by dissolving 1:1 mixture of Ham’s F12 Medium and Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM/F12, Sigma, St. Louis, MO), with 2.5 mM L-glutamine (without phenol red) in filter sterilized DI water. The medium was then supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, ATCC, Manassas, VA) and 0.3 mg/mL G418 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Cultures were kept in an incubator at 34 °C under an atmosphere of 5% CO2 and the study was carried out for 2 days.

2.6.2. Cellular morphology

After 1 and 2 days, samples were removed from culture to study the effect of different composition and time on morphology of osteoblast cells. Samples were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde/2% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer overnight at 4 °C. All samples were then rinsed with 0.1 M phosphate buffer, followed by post fixation with 2 % osmium tetroxide (OsO4) for 2 h at room temperature. Samples were rinsed again with 0.1 M phosphate buffer followed by dehydration in ethanol series (30, 50, 70, 95, and 100 % three times). Hexamethyldisilane (HDMS) was used for the final dehydrating step. Samples were kept in a vacuum desiccator for overnight drying. A gold sputter coater was used to apply a layer of coating with thickness of 3-4 nm. The morphology of samples was then studied using FESEM.

2.6.3. Proliferation of osteoblast cells

The osteoblast cell viability was measured using MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5- diphenyl tetrazolium bromide) assay after 1 and 2 days of culture. Samples were moved to a new 24-well plate and 100 μL of MTT (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) solution was added on top of each sample, followed by the addition of 900 μL of cell media. After 2 hours of incubation at 34 °C, the solution was removed from each well and 600 μL of solubilizer solution (composed of 10 % Triton X-100, 0.1N HCl and isopropanol) was added to each sample to dissolve formazan crystals. Formazan is a purple colored compound produced after reduction of MTT by cellular enzymes. 100 μL of this solution was transferred to 96-well plate and read by UV–Vis spectroscopy (BioTek) at 570 nm.

3. Results

3.1. Ceramic slurry characterization

The density and extrusion rate of each slurry are given in Table III. Extrusion rates, regardless of printing parameter or slurry composition were not found to be significantly different, ranging from 0.01-0.02 g/s and 0.31-0.39 ml/min in both cases. Densities of slurries varied from 1.43-1.76 g/ml where PCL addition was found to densify composition 2.

Table III.

Density, designed porosity, and extrusion rates for ceramic slurry preparations

|

Composition 1 |

Composition 2 |

Composition 1 with PCL |

Composition 2 with PCL |

Composition 1 with designed porosity |

Composition 2 with designed porosity |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extrusion rate (g/s) | 0.01 ± 0.00* | 0.01 ± 0.00* | 0.01 ± 0.00* | 0.02 ± 0.00* | 0.01 ± 0.00* | 0.01 ± 0.01* |

| Extrusion rate (ml/min) | 0.33 ± 0.01* | 0.37 ± 0.02* | 0.31 ±0.01* | 0.39 ± 0.00* | 0.36 ± 0.04* | 0.37 ± 0.02* |

| Apparent Density (g/ml) | 1.76 ± 0.11* | 1.85 ± 0.26* | 1.83 ± 0.18* | 1.96 ± 0.07* | 1.24 ± 0.01* | 1.34 ± 0.14* |

| Bulk Density (g/ml) | 1.10 ± 0.02* | 1.14 ± 0.02* | 1.16 ± 0.05* | 1.21 ± 0.05* | 0.10 ± 0.06* | 0.98 ± 0.02* |

| Total Designed | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 55 | 60 |

| Open Porosity (%) |

n=3

3.2. SFF scaffold characterization

As shown in Table III, bulk densities are much lower than expected. This is likely due to small changes in radius due to swelling of the ceramic slurry irrespective of layer height. Thus, apparent density is the true density of the scaffolds, and accounts for closed porosity within the scaffold walls. Since bulk densities are much lower than the apparent density and should account for closed and open porosities of the scaffold, total open porosity was measured as a percentage of fully dense scaffolds with a fill density of 40%.

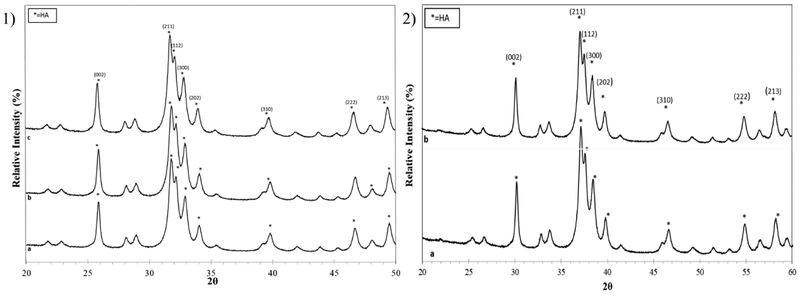

Figures 3a and b show XRD patterns for compositions 1 and 2 without and with PCL addition in comparison to milled HA powder. All scaffold preparations show the characteristic sharp peaks of the pure HA phase, which matches well with JCPDS # 09-0432, while accounting for a small peak shift in PCL containing scaffolds due to the change from Cu to Co source that results from greater 2ϴ positioning based on cobalt’s higher wavelength.

Figure 3.

XRD patterns of powders from prepared scaffolds 1) a) Monsanto HA, b) composition 1, c) composition 2. 2) a) composition 1 with PCL b) composition 2 with PCL. Overall, all scaffold preparations show the characteristic sharp peaks of the pure HA phase, which matches well with JCPDS # 09-0432.

FTIR spectra of corn starch, milled Monsanto HA, and prepared scaffolds were obtained utilizing an ATR-FTIR spectrophotometer. In the corn starch spectrum in Figure 4, the characteristic band at 2,919 cm−1 is attributed to C-H bond stretching. Another strong broad band appears at 3,000-3,600 cm−1 due to hydroxyl bond stretching associated with complex vibrational stretches of free, inter- and intra- molecular bound hydroxyl groups that make up a large part of the starch structure [23]. A mild characteristic band representing C=O stretching is present at 1661-1623 cm−1. This demonstrates that some molecular chains of amylopectin or amylose present in natural corn starch may have been fractured upon treatment [23]. A strong adsorption band around 990 cm−1 is representative of C-O-C bond.

Figure 4.

FT-IR spectra of corn starch.

The most characteristic chemical groups in the FTIR spectrum of HA are PO43− and OH- [24]. In high and low solids loading preparations as well as the Monsanto HA powder (Figure 5a, b, c), PO4 2− peaks are present which can be categorized into antisymmetric and symmetric stretching modes of HA phosphate groups. The antisymmetric (v3) P-O stretching modes can be seen between 1,085 and 1,012 cm−1. In addition, the P-O (v1) symmetric stretching mode appears at 960 cm−1. The anti-symmetric (v4) P-O bending modes of the phosphate group were found in the region of 540-650 cm−1 [25, 26]. OH- is present at around 3,571 cm−1 in all spectrums. HA clearly dominates all scaffold composition spectrums, which is to be expected due to its higher solids loading and the lack of post processing of the scaffolds [24]. As can be seen in Figure 5c, some noise is present around 1,800 to 2,400 cm−1. In these cases, a band with varying intensity occurs around 2,349 cm−1, together with 667 cm−1. This is typically due to the presence of CO2 in the beam, which is caused by poor background correction.

Figure 5.

FT-IR spectra of a) Monsanto HA b) composition 1 c) composition 2.

PCL FTIR bands are presented in Figure 6d with bands at 2,950 cm−1 and 2,870 cm−1 representing asymmetric and symmetric CH2 stretching modes [27]. A clear band at 1,720 cm−1 is indicative of carbonyl stretching. In addition, the band at 1,293 cm−1 represents C–O and C–C stretching in the crystalline phase, and the asymmetric COC stretching mode was signified by the 1240 cm−1 band [27]. No clear bands can be attributed to PCL or acetone in scaffolds prepared with 5% PCL except an OH− band around 3,500 cm−1. The absence of a band at 1,750 cm−1, corresponding to an ester group suggests that PCL did not affect the general chemical structure of the scaffold.

Figure 6.

FT-IR spectra of a) Monsanto HA b) composition 1 with PCL c) composition 2 with PCL d) PCL

Surface morphology for designed dense samples was observed under SEM, where horizontal and vertical cross sections were both imaged. As shown in the SEM micrographs displayed in Figures 7a and b, little to no microporosity is present in either section of these scaffolds and the surfaces are free from any visible cracks in both horizontal and vertical cross sections for compositions 1 and 2.

Figure 7.

SEM micrograph showing a) the microstructure of the dense HA scaffold preparations, cross sectioned horizontally b) cross sectioned vertically. There is little microporosity in both cross sections, suggesting the fabrication of fully dense scaffolds.

Optical images were obtained for cross sections of composition 1 and 2 scaffolds with designed porosity. These images are representative of both low and high solids loading samples with 24% and 22% fill densities respectively, as shown in Figure 8. Surface morphologies for designed porous samples of composition 1 (Figure 9) and composition 2 (Figure 10) were also observed under FESEM, where large pore architecture was present in horizontal cross sections, and interconnected porosity channels were present in vertical cross sections. Composition 1 samples consist of two interconnected channels while composition 2 samples only contain one.

Figure 8.

Stereoscope images of HA, corn starch scaffolds with designed porosity, showing open pore and interconnected pore architecture

Figure 9.

SEM micrograph showing the microstructure of composition 1 HA porous scaffold, cross sectioned horizontally and vertically. Interconnected porous channels are visible with fully dense microstructure surrounding it.

Figure 10.

SEM micrograph showing the microstructure of composition 2 HA porous scaffold cross sectioned horizontally and vertically. An interconnected porous channel is visible with dense microstructure surrounding it.

Compressive strengths of all six scaffold samples are shown in Figure 11. With the addition of approximately 5 wt% starch, it was found that even without post processing, composition 1 scaffolds achieved a maximum strength of 10.35 ± 1.10 MPa which was found to be significantly higher than composition 2 with a maximum compressive strength of 4.07 ± 0.66 MPa. PCL addition significantly decreased the strength of both scaffolds: low and high solids loading compositions from 10.35 ± 1.10 MPa to 5.95 ± 0.20 MPa and 4.07 ± 0.66 MPa to 1.91 ± 0.25 MPa respectively. Compared to fully dense scaffolds, designed porosity decreased the maximum compressive strength of compositions 1 and 2 as well to 6.80 ± 0.10 MPa and 3.06 ± 0.42 MPa respectively.

Figure 11.

Compressive strength comparison of low (composition 1) and high (composition 2) HA loaded scaffold compositions with designed porosity and PCL addition. Composition 1 with lower HA loading and higher starch loading resulted in higher strengths, with a maximum strength of 10.35 ± 1.10 MPa.

3.3. In vitro

Figure 12 shows osteoblast cellular morphology on samples after Day 1 and Day 2 of culture for pure HA, composition 1, composition 2, and composition 1 with PCL. Clear osteoblast cell attachment as well as apatite formation were observed on control samples. All starch compositions at Day 1 showed surface attachment of osteoblast cells with 3D-like morphology and filopodia extensions, as well as apatite formation, indicating favorable cell attachment and spreading. Composition 2 shows some flattened surface presence and attachment of cells suggesting a dense cellular layer at Day 1. Due to dissolution of the scaffolds, Day 2 results showed lower osteoblast attachment with fewer lamellipodia and filopodia extensions. Crystal formation was found in all compositions, which is a key feature of calcium deficient apatite formation.

Figure 12.

Osteoblast morphology on samples after 1 and 2 days of culture, showing cellular attachment on starch-based scaffolds, represented by arrows.

MTT results showed significantly higher optical cell density for all starch preparations compared to control HA samples at Day 1 (Figure 13). Initial optical density measurements suggest the attachment and rapid proliferation of cells on the starch scaffolds. Compositions 1 and 2 showed the highest cell density at Day 1 in comparison to all other preparations. However, Day 2 showed much lower optical density for all starch-based scaffolds, particularly Composition 1 with PCL. This is likely due to apatite formation and degradation or dissolution effects of the scaffolds.

Figure 13.

hFOB optical cell density on starch-based samples after 1, and 2 days of culture (*<0.05), where MTT results are showing significantly higher optical cell density for all starch preparations compared to control HA samples at Day 1.

4. Discussion

Orthopedic injuries remain a major area of research in bone tissue engineering, where bone fractures and bone defects due to trauma-related injuries account for more than 1.3 million procedures in the US alone [28, 29]. Bone tissue engineering research has focused on the creation of novel 3D printed composite scaffolds that can support the formation of new bone. Recent work has been developed in SFF based methods in order to enhance the biological and mechanical properties of resorbable scaffolds [30]. Other additive manufacturing methods have several constraints including the building of scaffolds without sufficient mechanical strength and post sintering microstructure and phase compositional changes. SFF methodology minimizes scaffold surface defects, allows for improved mechanical properties, customizable external geometry, and the ability to optimize pore architecture [31].

The selection of a polymer in the construction of 3D printed scaffolds is critical to the properties of the final scaffold, particularly one that is not post-processed. How polymer systems are implemented can change a scaffold’s surface properties, mechanical and degradation behavior, and biocompatibility [32]. Scaffolds utilizing natural polymers are becoming of greater interest due to their biocompatibility and tailorable structural and chemical properties such as bioresorbability and mechanical strength. Ceramic based structures possess many limitations that can be mitigated by the use of polymers [33, 34]. Starch based scaffold systems in particular are promising candidates in bone and tissue engineering applications. As a naturally sourced polymer, starch has chemical versatility, where specific chemical modifications allow starch to gain functional characteristics [35]. This has limited its utilization in SFF techniques, particularly those that involve melting due to the solubilization of starch based on temperature [36]. Thus, starch as a biomedical material has found wider applications in hydrogel and drug delivery systems [37]. By blending starch with HA, scaffold properties may greatly improve in order to implement calcium phosphate biomaterials with starch as a natural binder system in bone repair, substitution, or augmentation.

Understanding how different parameters effect the biological and mechanical structure of starch-based HA scaffolds is critical to the implementation of starch-based scaffolds in bone and tissue engineering applications. In this study, a solid freeform fabricator was designed and successfully implemented as a means for rapid prototyping of natural polymer-based HA composite scaffolds. In addition, solids loading, PCL addition, and designed porosity were examined in order to determine the effects on HA scaffolds with a starch binder system. Through FTIR and XRD analysis, HA dominated the chemical structure of the scaffold. Also, through optical and FESEM analysis, little to no microporosity was observed for dense scaffold preparations as well as the designed porous scaffolds. Scaffold surfaces were free from any visible cracks in both horizontal and vertical cross sections. The large pore architecture present in the horizontal cross sections as well as the interconnected porosity channels present in the vertical cross sections is particularly important due to its ability to increase cell proliferation and migration for tissue vascularization [38, 39].

It was shown that higher solids loading of HA resulted in lower compressive strengths. With the addition of approximately 5 wt% starch, it was found that even without post processing composition 1 scaffolds achieved a maximum strength of 10.35 MPa which was found to be significantly higher than composition 2 and more closely resembles the compressive strength of cancellous bone. This suggests that a strengthening mechanism exists between HA and gelatinized starch.

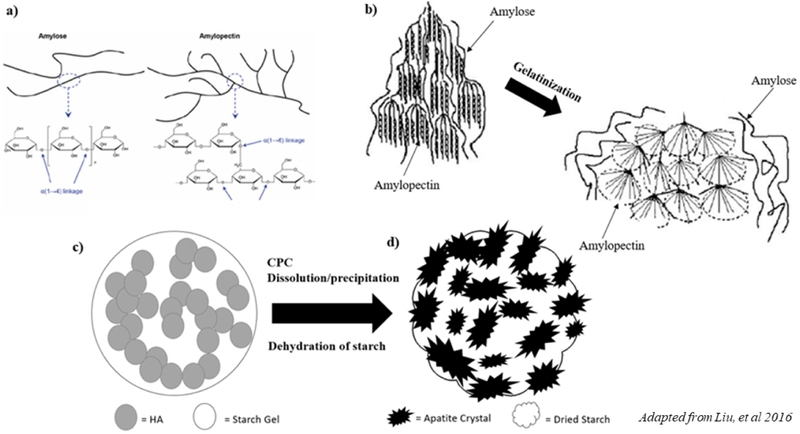

The granular structure of starch consists of two types of alphaglucan: linear and helical amylose and branched amylopectin (Figure 14a) and assembles into semi-crystalline granules [40]. Starch becomes soluble in water, where amylose molecules form a network that retains water as amylopectin swells, increasing the mixture’s viscosity. Ultimately, the disruption in hydrogen bonding during water retention produces what is referred to as a thermoplastic starch [14]. When hot water is applied, flocculation occurs and thermoplastic starch is transformed in a process called gelatinization (Figure 14b). Much has been studied regarding improvement of mechanical strength of composite scaffolds using ceramic components that densify upon post processing methods such as sintering [41, 42]. However, very few studies have proposed that the organic component of the slurry provides the green strength of the part [43]. Gelatinized starch, with proper viscoelastic behavior, has been shown to form a strong and injectable paste that can be utilized to improve the properties of a scaffold [44, 45, 24]. This is due to the fact that gelatinized starch acts as a reinforcing phase for CaP scaffolds, increasing the mechanical stability and the integrity of CaP cements depending on its properties as shown in Figure 14c [45, 37].

Figure 14.

Schematic representation illustrating the proposed mechanism for the reinforcement of calcium phosphate scaffolds by gelatinized starch. a) The granular structure of starch consists of two types of α-glucan: linear and helical amylose and branched amylopectin, and assembles into semi-crystalline granules. b) Gelatinization is the process of the solubilization of starch, where flocculation occurs upon the addition of hot water. Thermoplastic starch is transformed due to the swelling of amylopectin, and the network formation of amylose molecules c) Upon drying, the starch gel acts as a second phase in the ceramic slurry. d) HA converted apatite crystals exhibit tight interlocking in a starch envirnoment.

There are two mechanisms that have been proposed for the interaction between gelatinized starch when mixed with calcium phosphate-based cements (CPC) and water [44]. It is well known that there is a dissolution and precipitation process during setting and hardening of calcium phosphate cements [44]. This process may extract water from the starch gel, converting the gelled starch into a strong reinforcing phase in the cement. If the starch is hydroxyl-rich, it can strongly interact with apatite crystals through interparticle and crystal bonding (Figure 14c, d). Through these mechanisms, the reaction of a second phase of starch with interparticle and apatite crystal interlocking improves the strength of the scaffold and higher compressive strengths were achieved without the need for post processing through the addition of starch. PCL addition significantly decreased the strength of both low and high solids loading compositions. It is likely that acetone or PCL hindered the gelatinization phase of corn starch, disrupting the swelling of amylopectin and cross linking of amylose and ultimately influencing the mechanical strength of the scaffold.

Starch based scaffolds were found to increase cellular attachment at Day 1 compared to pure HA sintered samples. Lower cellular attachment at Day 2 is due to the surface degradation of these samples. Similar results have been shown before related to the importance of a stable cell-material interface to the support of cellular adhesion, which can otherwise also impact subsequent cell proliferation [46, 47]. With respect to bioactive HA and starch-based scaffolds, the surface degradation behavior plays a critical role in the cellular response. The addition of starch showed increased cellular attachment at Day 1 due to favorable cell-material interactions. However, as surface degradation occurred, a decreased proportion of highly spread cells was witnessed by MTT analysis. This was due to a decrease in the cytoplasmic processes for surface degradation that lowered cell anchorage and therefore growth. This mechanism was also seen with PCL addition, where the degradation of these scaffolds occurred at a faster rate due to PCL’s interference with starch’s reinforcing mechanism with HA, resulting in a larger decrease in cellular attachment at Day 2. Upon imaging, there was a confirmation of cellular attachment and in vitro cellular promotion in the developed microstructure of the starch-based scaffolds. This suggests that starch-based polymers allow for increased degradation time and porosity as cellular integration increases, which is optimal for bone tissue engineering.

Overall, the reinforcement mechanism and biocompatibility of starch-HA composite scaffolds can be tailored based on the starch source and the chemical versatility between the amount of starches’ glycoproteins and is being explored in our group’s future work. Through improvements in biocompatibility and enhanced mechanical integrity, as well as a deeper understanding into the composition and in vitro response of starch-based HA scaffolds, the next generation of natural biomaterials can be achieved and advanced material applications made possible through rapid prototyping technology.

5. Conclusions

In this study, HA-composite scaffolds utilizing a gelatinized starch binder system were fabricated in order to understand the influence of starch on mechanical and biological properties as well as assess the implementation of natural based polymers in 3D printing technologies. The utilization of starch in the gelatinized phase allowed for the 3D printing of resorbable bone scaffolds with enhanced bioactivity and mechanical strength using a ceramic-slurry based 3D printer. Higher starch loading was found to improve mechanical strength from 4.07 ± 0.66 MPa to 10.35 ± 1.10 MPa, which more closely resembled the mechanical strength of cancellous bone. Starch and PCL addition were also found to improve human fetal osteoblast proliferation in vitro through MTT and SEM analysis. These results elucidate gelatinized starch as a reinforcement phase for HA composite scaffolds as well as suggest a dissolution mechanism for cellular integration in vitro. SFF was found to constitute a new processing technology for the preparation of ceramic composite scaffolds for bone tissue engineering utilizing natural based polymers.

Acknowledgements

Authors would like to acknowledge financial support from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under grant numbers R01 AR066361, and does not have any possible conflict of interest. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Health. Authors would also like to thank Valerie Lynch-Holm and Dan Mullendore from Franceschi Microscopy & Imaging Center (WSU) as well as Dr. José Marcial and Ms. Emily Neinhuis from the NOME Materials Laboratory (WSU) for experimental assistance.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- [1].Ngiam M, Liao S, Patil AJ, Cheng Z, Chan CK, Ramakrishna S. “The fabrication of nano-hydroxyapatite on PLGA and PLGA/collagen nanofibrous composite scaffolds and their effects in osteoblastic behavior for bone tissue engineering.” Bone. 45 (2009) 4–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Bose Susmita, Vahabzadeh Sahar, Bandyopadhyay Amit. “Bone tissue engineering using 3D printing” Materials Today. 16 (2013) 496–504. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Ine Van Nieuwenhove Achim Salamon, Peters Kirsten, Graulus Geert-Jan, Martins José C., Frankel Daniel, Kersemans Ken, Filip De Vos Sandra Van Vlierberghe, Dubruel Peter. “Gelatin- and starch-based hydrogel. Part A: Hydrogel development, characterization and coating. Carbohydrate Polymers. 152 (2016) 129–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Tarafder Solaiman, Davies Neal M., Bandyopadhyay Amit, Bose Susmita. “3D printed tricalcium phosphate bone tissue engineering scaffolds: effect of SrO and MgO doping on in vivo osteogenesis in a rat distal femoral defect model.” Biomaterials Science. 1 (2013) 1250–1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Lam CXF, Mo XM, Teoh SH, Hutmacher DW. “Scaffold development using 3D printing with a starch-based polymer.” Materials Science and Engineering: C. 20 (2002) 49–56. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Lewis Jennifer A., Smay James E., Stuecker John, Cesarano Joseph III. “Direct Ink Writing of Three-Dimensional Ceramic Structures. Journal of American ceramic Society. 89 (2006) 3599–3609 [Google Scholar]

- [7].Bourell DL, Beaman JJ, Marcus HL, Barlow JW. “Solid Freeform Fabrication: An Advanced Manufacturing Approach.” The Unviersity of Texas Austin 1990. International Solid Freeform Fabrication Symposium. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Turnbull Gareth, Clarke Jon, Picard Frédéric, Riches Philip, Jia Luanluan, Han Fengxuan, Li Bin, Shu Wenmiao.”3D bioactive composite scaffolds for bone tissue engineering.” Bioactive Materials. 3 (2018) 278–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Morisette Sherry L., Lewis Jennifer A., Cesarano Joseph, Dimos Duane B., Baer Tom, “Solid Freeform Fabrication of Aqueous Alumina–Poly(vinyl alcohol) Gelcasting Suspensions.” Journal of the American Ceramic Society. 83 (2004) [Google Scholar]

- [10].Bose Susmita, Roy Mangal, Bandyopadhyay Amit. “Recent advances in bone tissue engineering scaffolds.” Trends in Biotechnology. 30 (2012) 546–554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Habraken Wouter, Habibovic Pamela, Epple Matthias, Bohner Marc. “Calcium phosphates in biomedical applications: materials for the future.” Materials Today/. 19.2 (2016) 69–87. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Bigi Adriana, Boanini Elisa. “Functionalized Biomimetic Calcium Phosphates for Bone Tissue Repair.” Journal of Applied Biomaterials and Functional Materials. 15 (2018) 313–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Susan Cortizo M, Soledad Belluzo M.”Biodegradable Polymers for Bone Tissue Engineering.” Industrial Applications of Renewable Biomass Products Past, Present and Future. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Ahmed EM. “Hydrogel: Preparation, characterization, and applications: A review.” In Journal of Advanced Research. 6 (2015) 105–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Szepes Anikó, Makai Zsolt, Christoph Blümer Karsten Mäder, Péter Kása Piroska Szabó Révész. “Characterization and drug delivery behavior of starch-based hydrogels prepared via isostatic ultrahigh pressure.” Carbohydrate Polymers. 72 (2008) 571–578. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Cheung HY, Lau KT, Lu TP, Hui D. “A critical review on polymer-based bio- engineered materials for scaffold development.” Composites Part B. 38 (2007) 291–300. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Epigares Ismael, Elvira Carlos, Mano Joao F., Vazquez Blanca, Julio San Roman Rui L. Reis. “New partially degradable and bioactive acrylic bone cements based on starch blends and ceramic fillers.” Biomaterials. 23 (2002) 1883–1895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Lam CXF, Mo XM, Teoh SH, Hutmacher DW. “Scaffold development using 3D printing with a starch-based polymer.” Materials Science and Engineering C: Materials for Biological Applications. 20 (2002) 49–56. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Ang TH, Sultana FSA, Hutmacher DW, Wong YS, Fuh JYH, Mo XM, Loh HT, Burdet E, Teoh SH. “Fabrication of 3D chitosan–hydroxyapatite scaffolds using a robotic dispensing system.” Materials Science and Engineering C. 20 (2002) 35–42. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Geng L, Feng W, Hutmacher DW, S Wong Y, Loh HT, H Fuh JY. “Direct writing of chitosan scaffolds using a robotic system.” Rapid Prototyping Journal. 11 (2005) 90–97. [Google Scholar]

- [21].LeBeau James M., Boonyongmaneerat Yuttanant. “Comparison study of aqueous binder systems for slurry-based processing.” Materials Science and Engineering A. 48 (2007) 17–24. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Thavomyutikarn Boonlom, Chantarapanich Nattapon, Sitthiseripratip Kriskrai, Thouas George A., Chen Qizhi. “Bone Tissue Engineering Scaffolding: Computer-Aided Scaffolding Techniques.” Progress in Biomaterials. 3 (2014) 61–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Liga Berzina-Cimdina Natalija Borodajenko. “Research of Calcium Phosphates Using Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy, Infrared Spectroscopy Materials Science, Engineering and Technology, Theophile Theophanides (Ed.) 2012. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Saiz E, Gremillard L, Menendez G, Miranda P, Gryn K, To AP. “Preparation of porous hydroxyapatite scaffolds.” Materials Science and Engineering C. 27 (2007) 546–550. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Roy Mangal, Bandyopadhyay Amit, Bose Susmita. “Induction Plasma Sprayed Nano Hydroxyapatite Coatings on Titanium for Orthopaedic and Dental Implants.” Surface & coatings technology. 205.8–9 (2011) 2785–2792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Roy M, Bandyopadhyay A, Bose S, “Induction plasma sprayed Sr and Mg doped nano hydroxyapatite coatings on Ti for bone implant.” J. Biomed. Mater. Res 99B (2011) 258–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Elzein Tamara, Mohamad Nasser-Eddine Christelle Delaite, Bistac Sophie, Dumas Philippe. “FTIR study of polycaprolactone chain organization at interfaces.” Journal of Colloid and Interface Science. 273 (2004) 381–387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Chim H, Hutmacher DW, Chou AM, Oliveira AL, Reis RL, Lim TC, Schantz JT. “A comparative analysis of scaffold material modifications for load-bearing applications in bone tissue engineering,” International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 35 (2006) 928–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Gibson Ian, Savalani Monica M., Christopher XF Lam Radoslow Olkowski, Ekaputra Andrew K., Kim Cheng Tang Dietmar W. Hutmacher, “Towards a medium/high load- bearing scaffold fabrication system.” Tsinghua Science and Technology. 14 (2009) 13–19. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Zhao WX, Zheng WW, Li JH, Lin HH. “Synthesis and characterization of starch fatty acid esters.” Mod. Chem. Ind 27 (2007) 281–283. [Google Scholar]

- [31].Abarrategi Ander, Carolina Moreno-Vicente Francisco Javier Martínez-Vázquez, Civantos Ana, Ramos Viviana, José Vicente Sanz-Casado Ramón Martínez-Corriá, Fidel Hugo Perera Francisca Mulero, Miranda Pedro, López-Lacomba José Luís “Biological Properties of Solid Free Form Designed Ceramic Scaffolds with BMP-2: In Vitro and In Vivo Evaluation.”. PLoS ONE. 7 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Gomes ME, Salgado A, Reis RL. “Bone Tissue Engineering Using Starch Based Scaffolds Obtained by Different Methods.” Polymer Based Systems on Tissue Engineering, Replacement and Regeneration. NATO Science Series (Series II: Mathematics, Physics and Chemistry). 86 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- [33].Thomson RC, Wake MC, Yaszemski M, Mikos AG. “Biodegradable polymer scaffolds to regenerate organs.” Adv Polym Sci 122 (1995) 247–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Maquet V, Jerome R. “Design of Macroporous Biodegradable Polymer Scaffolds for Cell Transplantation”. Maler Sci Forum 20 (1997) 15–42. [Google Scholar]

- [35].Roslan MR, Nasir NFM, Cheng EM and Amin NAM, “Tissue engineering scaffold based on starch: A review.” 2016 International Conference on Electrical, Electronics, and Optimization Techniques (ICEEOT) (2016) 1857–1860. [Google Scholar]

- [36].Mano JF, Silva GA, Azevedo HS, Malafaya PB, Sousa RA, Silva SS, Boesel LF, Oliveira JM, Santos TC, Marques AP, Neves NM, Reis RL. “Natural Origin Biodegradable Systems in Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine: Present Status and Some Moving Trends.” Journal of the Royal Society Interface. 4 (2007) 999–1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Fengwei Xie, Pollet Eric, Halley Peter J., Averous Luc. “Advanced Nano-biocomposites Based on Starch” Polysaccharides. Springer Iteration Publishing Switzerland; (2014) 1–75. [Google Scholar]

- [38].Qiu Li Loh Cleo Choong. “Three-Dimensional Scaffolds for Tissue Engineering Applications: Role of Porosity and Pore Size.” Tissue Engineering. Part B, Reviews 19 (2013) 485–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Samar Jyoti Kalita Susmita Bose, Hosick Howard L., Bandyopadhyay Amit. “Development of controlled porosity polymer-ceramic composite scaffolds via fused deposition modeling.” Materials Science and Engineering: C. 23 (2003) 611–620. [Google Scholar]

- [40].Riza Roslan M, Mohd Nasir NF, Cheng EM, Amin NAM. “Tissue Engineering Scaffold Based on Starch: A Review. International Conference on Electrical, Electronics, and Optimization Techniques 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [41].Tarafder S, Balla VK, Davies NM, Bandyopadhyay A, Bose S. “Microwave Sintered 3D Printed Tricalcium Phosphate Scaffolds for Bone Tissue Engineering.” Journal of tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. 7 (2013) 631–641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Fielding Gary A., Bandyopadhyay Amit, Bose Susmita. “Effects of SiO2 and ZnO Doping on Mechanical and Biological Properties of 3D Printed TCP Scaffolds.” Dental Materials. 28 (2012) 113–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Baltes Henry, Brand Oliver, Fredder Gary K.. “Microengineering of Metals and Ceramics: Part I: Design, Tooling, and Injection Molding.” Advanced Micro and Nanosystems. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- [44].Liu H, Guan Y, Wei D, Gao C, Yang H, Yang L. “Reinforcement of injectable calcium phosphate cement by gelatinized starches.” J Biomed Mater Res Part B. 104 (2016) 615–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Zhang J, Liu W, Schnitzler V, Tancret F, Bouler JM. “Calcium phosphate cements for bone substitution: Chemistry, handling and mechanical properties.” Acta Biomaterialia. 10 (2013) 1035–1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Banerjee Shashwat S., Bandyopadhyay Amit, Bose Susmita. “Biphasic Resorbable Calcium Phosphate Ceramic for Bone Implants and Local Alendronate Delivery.” Advanced Engineering Materials. 12 (2010) 148–155. [Google Scholar]

- [47].Weichang Xue B., Krishna Vamsi, Bandyopadhyay Amit, Bose Susmita. “Processing and biocompatibility evaluation of laser processed porous titanium.” Acta Biomaterialia. 3 (2007) 1007–1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]