Abstract

a) Purpose of review:

Interstitial lung diseases (ILDs) cause unpredictable degrees of fibrosis and inflammation in the lungs leading to functional decline and varying symptom burden for patients. Some patients may live for years and be responsive to therapy and others disease trajectory may be shorter and similar to patients with lung cancer. This ultimately affects the patient’s quality of life as well as their caregiver(s).

b) Recent findings:

Nonpharmacological therapies play an important role in treatment of interstitial lung disease. These include symptom management, pulmonary rehabilitation, oxygen therapy, and palliative care. While ILDs are associated with high morbidity and mortality, different models of care exist globally. New tools help clinicians identify and address palliative care needs in daily practice and specialty nurses and ILD centers can optimize care.

c) Summary:

This paper provides an overview of nonpharmacological therapies available for patients with interstitial lung disease.

Keywords: Interstitial lung disease, nonpharmacological therapy, symptom management, pulmonary rehabilitation, oxygen therapy, palliative care

Introduction:

Interstitial lung disease

Interstitial lung diseases cause varying degrees of fibrosis and inflammation in the lungs of patients (1), and the disease progression leads the patient to experience functional decline and varying symptom burden, ultimately affecting quality of life. It is critical that the clinician is able to make a confident diagnosis of the specific form of ILD and formulate a patient-centered, personalized management plan to achieve remission or stabilization of the disease process when possible (2).

It is important for providers to relay disease information in a timely manner that is easily understood by patients and their caregivers to help them best manage their ILD. The words used to describe the major scarring lung diseases include: Interstitial lung disease, Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (IPF), Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis (HP), etc.; these terms confuse not only patients but also other medical providers (3).

Patients with Interstitial Lung Disease experience a wide range of diagnoses and can benefit most from early evaluation at a center with ILD expertise, such as the Pulmonary Fibrosis Foundation (PFF) Care Center Network (4). Connecting patients with access to clinical trials and support groups can provide additional benefit to participate in research studies to advance knowledge and treatment of ILD’s, provide accurate information about their disease, and help to connect with other patients with similar needs. These measures can help to improve social support and help the patient and caregiver avoid social isolation ultimately improving their quality of life. Early educational programs can help to increase knowledge of the disease so that patients and their caregivers can have a better understanding of the effect and consequences of these relentlessly progressive diseases (3, 5). Participation in support groups offers the patients and their caregiver(s) the opportunity to receive additional education and support outside of the office visit. Support groups offer resources to teach individuals how to cope and adapt to the lifestyle that is often dictated by their illness. The Pulmonary Fibrosis Foundation provides a list of support groups that are local and international, and on-line and telephone based communities (6).

Nonpharmacological therapies play an important role in the treatment plan for patients diagnosed with Interstitial lung disease (ILD).

Symptom Management

Patients with ILD have a wide range of diagnoses and prognoses; some may live many years with a disease that is responsive to treatment, but in those patients with Progressive Idiopathic Fibrotic Interstitial Lung Disease (PIF-ILD), the disease trajectory is shorter and similar to that of lung cancer (7, 8). Despite the varied nature of ILD, patients experience common symptoms related to their chronic lung disease which contribute significantly to their morbidity and impact their quality of life (9). In a quantitative review of patients with PIF-ILD, the overwhelming majority of patients had breathlessness (68.2 – 98%), cough (59 – 94%), heartburn (25–65%), and depression (10–49%) (7). In addition, this review found that patients experience a wide array of constitutional symptoms including sleep disturbances, fatigue and weight loss, and anorexia (7). The psychological stress of having a chronic life-limiting illness can complicate symptom control requiring effective symptom management, best achieved by a multidisciplinary approach that incorporates patient education and self-management to articulate goals of care and treatment plans (9). A number of both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic therapies are available to reduce symptoms in patients with IPF. These include low-dose narcotics, pulmonary rehabilitation (including pursed lip breathing) for treatment of dyspnea, and supplemental oxygen (10, 11). Dyspnea and cough often improves with supplemental oxygen. Cough is challenging to treat, but distressing to patients and caregivers. Treatment options include a range from hot tea, honey, menthol lozenges to treatment of gastroesophageal reflux, postnasal drip medication, benzonatate, and opiate-containing medications (12). Early identification of symptoms and referral for palliative care to alleviate symptom burden and improve quality of life are crucially important treatment goals (13). Pulmonary rehabilitation also plays an important role in symptom management (9).

Pulmonary Rehabilitation

Pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) has demonstrated physiological, symptom reducing, psychosocial, and health economic benefits for patients with chronic respiratory disease (14). Patients with ILD experience reduced functional capacity, dyspnea, and exercise-induced hypoxia (15). Referral to PR includes exercise training that has shown improvement in long-term outcomes in ILD including six-minute walk distance (6MWD), dyspnea, health related quality of life, and peak exercise capacity for patients with ILD (16, 17). In a study of 142 participants with different ILD’s (IPF, asbestosis, connective tissue disease-related ILD and other causes of ILD), participants were randomized to 8 weeks of supervised exercise training or usual care. Those participants who participated in supervised exercise training significantly increased their 6MWD and health related quality of life, with more lasting effects in those with milder disease (16). In another study done at 3 PR centers in North America, PR improved functional capacity and quality of life in patients with a variety of ILDs, with benefits lasting for at least 6 months (17). This group reported that the “consistency and magnitude of benefit across endpoints is substantial and markedly better than pharmacological interventions that have been studied in these diseases” and suggest that pulmonary rehabilitation should be the first line of therapy for patients with ILD (17). Barriers for participation in PR may include distance from patient’s location and reimbursement for attendance. Reimbursement may involve getting authorization from the patient’s payor source. Patients may qualify for Cardiac rehabilitation; while the focus may differ between cardiac and pulmonary, the emphasis is on supervised, safe exercise.

In another study of patients with ILD attending pulmonary rehabilitation, patients wanted ILD-specific content and wanted information about end-of-life planning and most were happy to discuss it in a group. In that same study, clinicians supported discussion of advanced care planning but not necessarily in the pulmonary rehabilitation setting (18). Communication with patients about goals of care is crucial and continued research is needed in this area.

Oxygen Therapy

In the 1980’s, use of supplemental oxygen therapy increased after the NOTT (Nocturnal Oxygen Therapy Trial) and the MRC (Medical Research Council) trials demonstrated survival benefits of providing long-term oxygen therapy to patients with resting arterial partial pressure of oxygen consistently less than 55 mm Hg (19, 20). Today, more than one million people in the United States use long term oxygen therapy, the majority with chronic obstructive lung disease (COPD) (21). Oxygen therapy is the most frequently used treatment for patients with ILD and IPF to treat hypoxemia and halt progression or prevent development of hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension, cardiovascular morbidity, or cognitive dysfunction (22, 23).

Oxygen prescriptions vary greatly for patients with ILD with patients often requiring oxygen with exertion and sleep earlier in the disease process before they require oxygen with rest. In one study, exertional hypoxemia was found to be more severe for patients with fibrotic lung disease than those patients with COPD. This group compared results of a 6-minute walk test (6MW) performed on room air in 134 patients with ILD and 247 patients with COPD. Diffusing capacity (DLco) was the strongest predictor of desaturation in both cohorts with ILD patients experiencing greater oxygen desaturation during the 6MW compared to patients with COPD (24).

Supplemental oxygen has allowed patients who otherwise would be homebound to be more mobile, work, exercise or attend pulmonary rehabilitation, travel, care for family members, and also experience improvement in their symptoms, including dyspnea, ultimately improving their quality of life (25, 26). Patients who require supplemental oxygen, especially those with ILD experience frequent and varied problems with receiving adequate portable systems to meet their dose requirement. Oxygen equipment is bulky and options are limited as oxygen dose increases. In a study of 30 clinically stable ILD patients with varying disease severity, carrying portable oxygen versus using oxygen from a stationary concentrator resulted in significantly greater dyspnea and shorter distances in timed testing (23). Portable systems can deliver continuous flow (CF) and intermittent flow (IF) and, while IF devices are safe and generally effective in correcting hypoxemia, there is variability in delivery and patient response and therefore patients need to be tested on these devices. (26). Use of a pulse oximeter is recommended to allow patients to adjust their oxygen flow to maintain saturations >89% at all times (27).

In a recent ATS survey of 1926 patients with lung disease who used oxygen, individuals with IPF were rarely on oxygen more than 5 years, but frequently used oxygen > 5LPM (28). Patients who received oxygen education had less health care utilization, including emergency visits and hospitalizations (28). Use of “a detailed discussion that includes an educational overview of oxygen, recommendations for how to use oxygen correctly, and disclosure of what hardships and benefits the patient (and their caregiver) might expect from oxygen” is endorsed for patients prescribed oxygen therapy (27). The process of oxygen prescription can be improved by providing patients with clearer expectations and trustworthy educational resources (29).

Palliative Care

ILDs are highly disabling and patients experience a loss of functional ability, resulting in great symptom burden as the disease advances ultimately impacting the patient’s quality of life (11). Patients with ILD often suffer unmet physical and psychological needs as they live with their ILD (30).

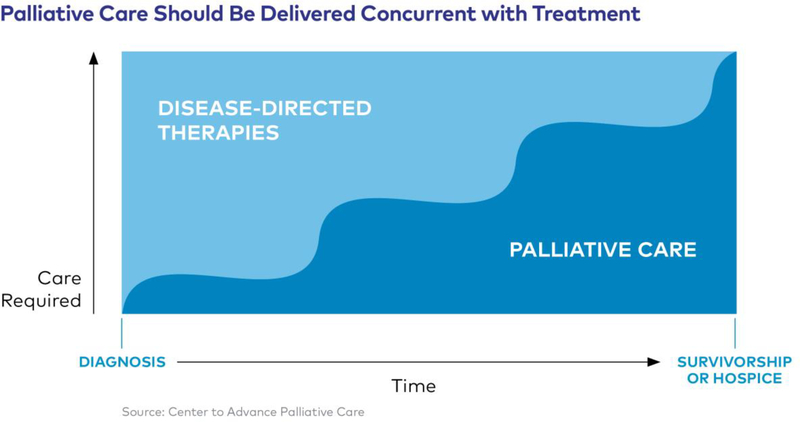

Palliative care is the comprehensive treatment of the discomfort, symptoms, and stress of serious illness and should be started as soon as the patient is diagnosed. Symptom management is relevant even in patients with mild to moderate disease. Traditionally, palliative care was seen as replacing the curative care with palliative or end-of-life care, but the paradigm has shifted and palliative care should be offered alongside all other treatments for the disease (9, 31). See Figure 1. In prior studies, patients with advanced lung disease, including IPF have been found less likely to receive palliative care than malignant diseases and other chronic conditions, including dementia (32, 33). Several reasons for fewer referrals include uncertainty regarding prognosis, lack of provider skill to engage in discussions about PC, fear of using opioids among patients with chronic lung disease, fear of diminishing hope, and perceived and implicit bias against patients with smoking-related lung disease (34).

Figure 1.

Palliative Care’s Place in Serious Illness

Used with permission from Center to Advance Palliative Care.

The main goal of palliative care (PC) for patients with interstitial lung disease (ILD) is to improve and maintain quality of life. Optimal quality of life care includes symptom-centered approaches, best supportive care, caregiver-centred management, disease-stabilizing care, patient-centred management, and end-of-life care (35). PC includes all of the interventions aimed to improve and optimize qualify of life (QoL) in patients affected by progressive disease (36). PC also includes helping the patient and their caregivers with advance care planning through the process for preference of end-of-life care (11). Addressing goals of care early in the disease trajectory is associated with improved patient outcomes and reduced intensity of end-of-life care (37).

Palliative care can be delivered by a member of the clinical care team, referred to as primary palliative care, or an interdisciplinary team, referred to as secondary or specialty palliative care. Optimal PC for patients with chronic lung disease, such as ILD should incorporate both primary and specialty PC (38). Challenges facing specialty palliative care include increased demands on limited resources (39). Supportive care is a term that has been associated with better understanding and more favorable impressions than palliative care (40). Hospice is different from palliative care and should be offered when the patient is not expected to live greater than 6 months (41). Resources are available to find non-hospital based (42) and hospital based palliative care programs (43),

The goals of PC are to prevent and relieve suffering, support the best quality of life for patients facing serious illness and their caregivers, and encourage discussions regarding EOL preferences. Studies have reported that even when patients and their caregivers understand the terminal nature of their disease, they did not appreciate that symptoms could escalate rapidly, resulting in death (30). Because of the unpredictable nature of ILD, especially IPF, early introduction of PC should be considered a standard of care. The mantra “It is wise to hope for the best, but it is also wise to prepare for the worst” can introduce the concept of advance care planning to the patient and their caregiver (44).

Tools to Help Clinicians Identify Palliative Care Needs

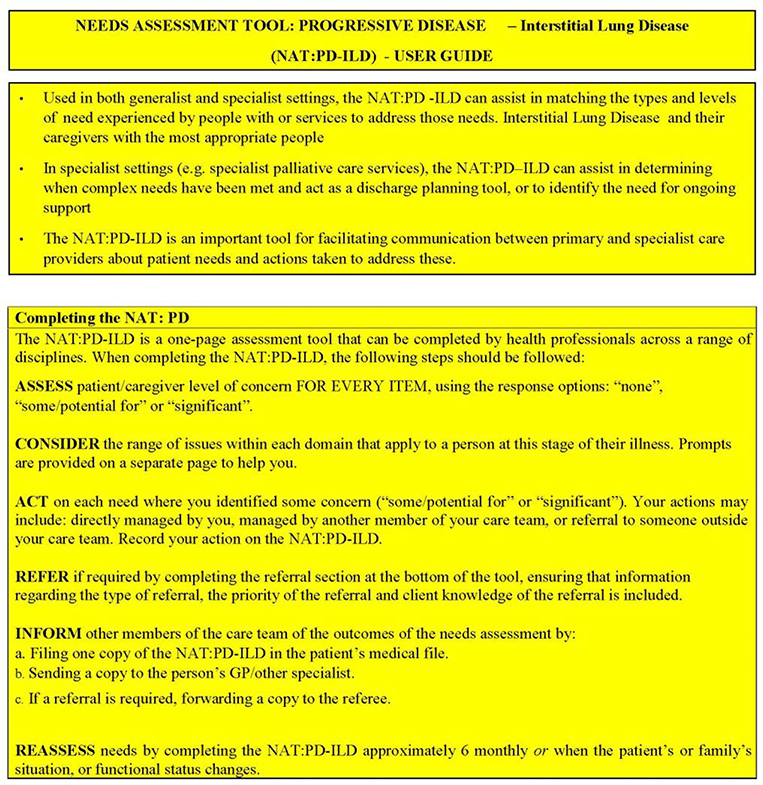

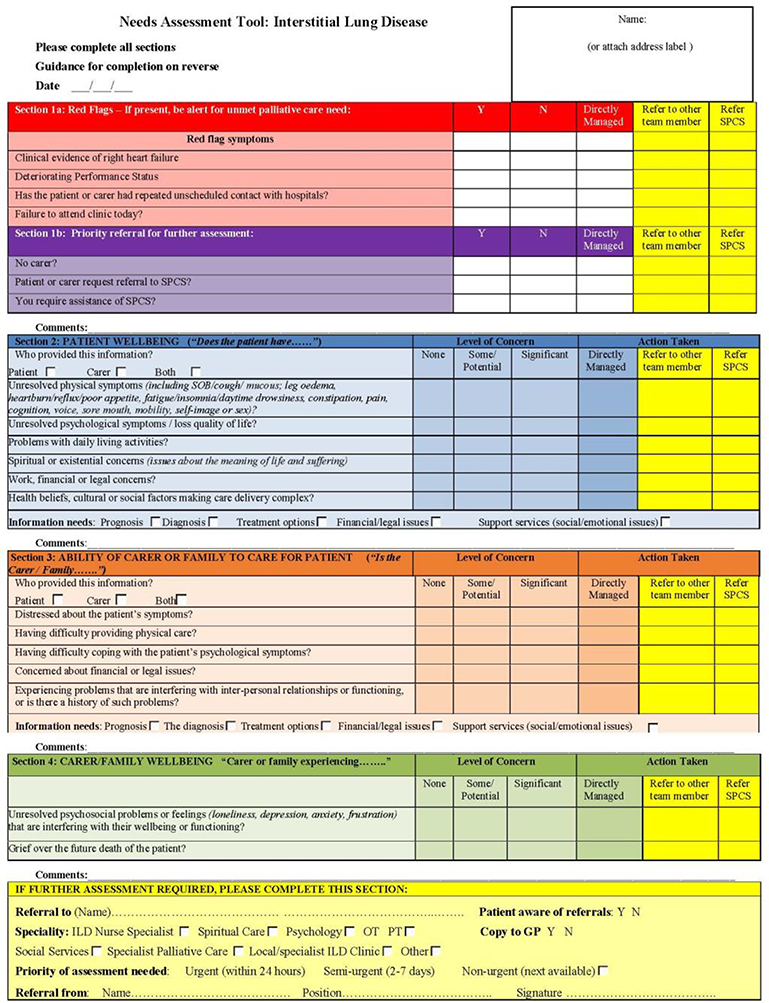

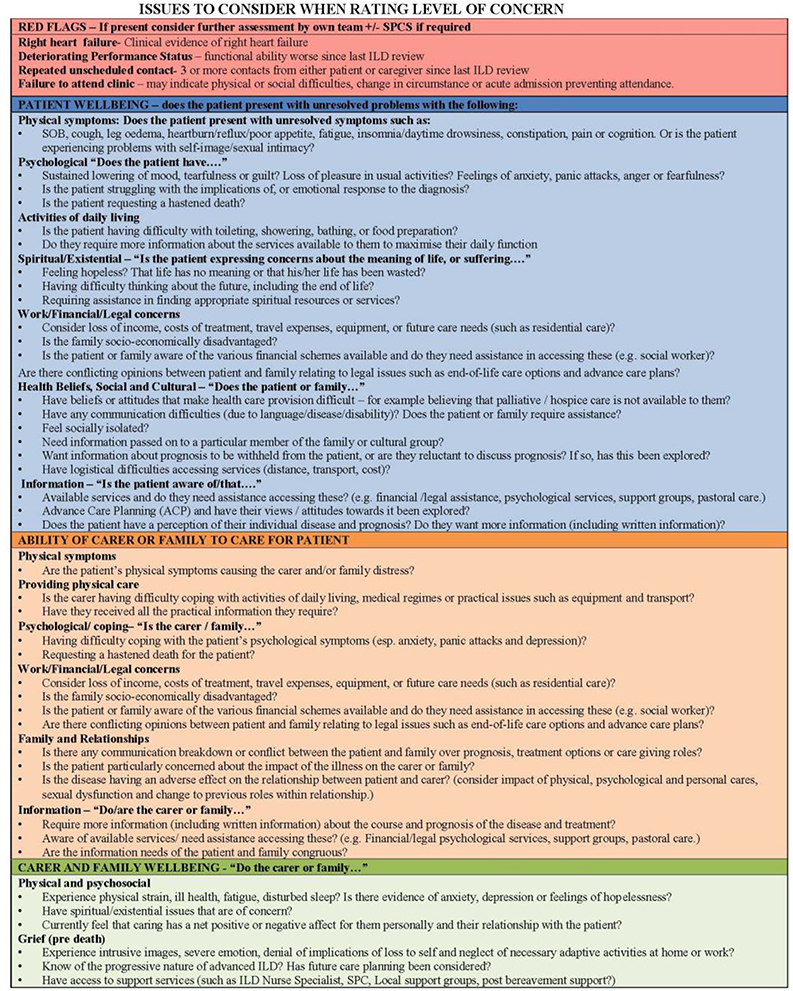

Identification and management of patients’ palliative care needs can be challenging for clinicians. The Needs Assessment Tool: Progressive disease in interstitial lung disease (NAT:PD-ILD) is a single page guide to prompt clinicians to assess patients’ well-being, informal carers’ need and information needs prompting referral for specialty palliative care (45) See Table 1.

Table 1.

The Needs Assessment Tool: Progressive disease in interstitial lung disease (NA:PDILD)

Role of ILD Clinical Nurse Specialist

Nurses are considered to be central to health care provision and highly valued by patients (46). Symptom management and palliative care are the hallmarks of nursing, especially within the realm of the ILD Clinical Nurse Specialist (47). The CNS provides expert knowledge and advice to patients and their families throughout all stages of care and is frequently the main clinical contact for healthcare working in concert with clinical care team. The main focus is on managing symptoms and frequently adjusting the plan of care as the disease progresses. Nurse and interdisciplinary-led research makes important contributions to the evidence base of clinical practice, especially in the non-pharmacological approaches to symptom management. These collaborations work to advance the care provided for patients.

Conclusion

ILDs are complex. Education and clarity of communication are essential for the patient and their caregiver(s) to understand and appreciate the magnitude of the disease. Participating in support groups and research studies offer the patient the ability to actively manage their disease. Different ILDs can have similar symptoms and complications, and it is important to address them with symptom specific treatments including pulmonary rehabilitation and supplemental oxygen therapy. Because the disease course is unpredictable, it is important to initiate palliative care early after diagnosis to optimize symptom management and address advance care planning. These nonpharmacologic therapies are crucial in supporting the patient and their caregiver(s) as they live with their interstitial lung disease.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

Kathleen Lindell declare no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as:

* Of importance

** Of major importance

- 1.Schraufnagel D Interstitial Lung Disease [July 16, 2018]. Available from: https://www.thoracic.org/patients/patient-resources/breathing-in-america/resources/chapter-10-interstitial-lung-disease.pdf.

- 2.Meyer K. Diagnosis and management of interstitial lung disease. Translational Respiratory Medicine. 2014;2(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morisset JDB, Garvey C, Bourbeau J, Collard HR, Swigris JJ, Lee JS. The unmet educational needs of interstitial lung disease patients: setting the stage for tailored pulmonary rehabilitatio. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13:1026–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pulmonary Fibrosis Foundation Care Center Network [Available from: http://www.pulmonaryfibrosis.org/medical-community/pff-care-center-network.

- 5.*.Lindell K, Nouraie M, Klesen MJ, Klein S, Gibson KF, Kass DJ, & Rosenzweig MQ. Randomised clinical trial of an early palliative care intervention (SUPPORT) for patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) and their caregivers: protocol and key design considerations. BMJ Open Resp Res. 2018;5:e000272 This protocol manuscript describes the key considerations for introducing early palliative care for patients with IPF including increasing knowledge of the disease, self-management strategies, and facilitating preparedness with EOL planning. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pulmonary Fibrosis Foundation Support Groups.

- 7.**.Carvajalino S, Reigada C, Johnson MJ, Dzingina M, & Bajwah S. Symptom prevalence of patients with fibrotic interstitial lung disease: a systematic literature review. BMC Pulmonary Medicine. 2018;18(78). This manuscript is the first quantitative review of symptoms in patients with progressive Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrotic Interstitial Lung Diseases. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vancheri C, Failla M, Crimi N, and Raghu G. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a disease with similarities and links to cancer biology. Eur Respir J. 2010;35:496–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garibaldi B, & Danoff SK. Symptom-based management of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonia. Respirology. 2016;21:1357–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Danoff SK, Schonhoft EH. Role of support measures and palliative care. Current opinion in pulmonary medicine. 2013;19(5):480–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lindell K. Palliative and End-of-Life Care in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis In: Collard HR & Richeldi L, editor. Interstitial Lung Disease. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Silhan LD, SK. Nonpharmacologic therapy for Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis Interstitial Lung Disease. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bajwah S, Ross JR, Peacock JL, Higginson IJ, Wells AU, Birring SS, and Patel AS. Interventions to improve symptoms and quality of life of patients with fibrotic interstitial lung disease: a systematic review of the literature. Thorax. 2013;68(9):867–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rochester C, Vogiatzis I, Holland AE, Lareau SC, Marciniuk DD, Puhan MA, Spruit MA, Masefield S, Casaburi R, Clinic EM, Crouch R, Garcia-Aymerich J, Garvey C, Goldstein RS, Hill K, Morgan M, Nici L, Pitta F, Ries AL, Singh SJ, Troosters T, Wijkstra PJ, Yawn BP, & ZuWallack RL on behalf of the ATS/ERS Task Force on Policy in Pulmonary Rehabilitation. An Official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society Policy Statement: Enhancing Implementation, Use, and Delivery of Pulmonary Rehabilitation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;192(11):1373–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dowman L HC, Holland AE. Pulmonary rehabilitation for interstitial lung disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014(10). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dowman L, McDonald CF, Hill CJ, Lee AL, Barker K, Boote C, Glaspole I, Goh NS, Southcott AM, Burge AT, Gillies R, Martin A, & Holland AE. The evidence of benefits of exercise training in interstitial lung disease: a randomised controlled trial. Thorax. 2017;72:610–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ryerson C, Cayou C, Topp F, Hilling L, Camp PG, Wilcox PG, Khalil N, Collard HR, & Garvey C. Pulmonary rehabilitation improves long-term outcomes in interstitial lung disease: a prospective cohort study. Respir Med. 2014;108(1):203–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holland A, Fiore JF, Goh N, Symons K, Dowman L, Westall G, Hazard A, and Glaspole I. Be honest and help me prepare for the future: What people with interstitial lung disease want from education in pulmonary rehabilitation. Chronic respiratory disease. 2015;12(2):93–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Group NOTT. Continuous or nocturnal oxygen therapy in hypoxemic chronic obstructive lung disease: a clinical trial. Ann Intern Med. 1980;93:391–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Long-term domicillary oxygen therapy in chronic hypoxic cor pulmonale complicating chronic bronchitis and emphysema: report of the Medical Research Council Working Party. Lancet. 1981;1:681–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nishi S, Zhang W, Kuo Y-F, Sharma G. Oxygen therapy use in older adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. PLoS ONE. 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Egan JJ. Follow-up and nonpharmacological management of the idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis patient. European respiratory review : an official journal of the European Respiratory Society. 2011;20(120):114–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ramadurai D, Riordan M, Graney B, Churney T, Olson AL, & Swigris JJ. The impact of carrying supplemental oxygen on exercise capacity and dyspnea in patients with interstitial lung disease. Resp Med. 2018;138:32–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.*.Du Plessis J, Fernandes S, Camp JR, Johannson K, Schaeffer M, Wilcox PG, Guenette JA, & Ryerson CJ. Exertional hypoxemia is more severe in fibrotic interstitial lung disease than in COPD. Respirology. 2017. This manuscript is the first to report that hypoxemia is more severe in patients with fibrotic interstitial lung disease as compared to COPD. Previous research has focused on COPD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mussa C, Tonyan L, Chen YF, & Vines D. Perceived Satisfaction With Long-Term Oxygen Delivery Devices Affects Perceived Mobility and Quality of Life of Oxygen-Dependent Individuals With COPD. Respiratory care. 2018;63(1):11–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Christopher KP,P Long-term Oxygen Therapy. Chest 2011;139(2):430–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Swigris J Supplemental Oxygen for Patients with Interstitial Lung Disease: Managing Expectations. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017;14(6):831–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.*.Jacobs S, Lindell KO, Collins EG, Garvey CM, Hernandez C, McLaughlin S, Schneidman A, & Meek PM. Patient perceptions of the adequacy of supplemental oxygen therapy: results of the American Thoracic Society Nursing Assembly Oxygen Working Group Survey. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2018;15:24–32. This manuscript details patient perceptions of oxygen users in the United States and the problems patients with lung disease experience on a daily basis. Patients who received education from the health provider had less healthcare utilization. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Graney BA, Wamboldt FS, Baird S, Churney T, Fier K, Korn M, et al. Looking ahead and behind at supplemental oxygen: A qualitative study of patients with pulmonary fibrosis. Heart & lung : the journal of critical care. 2017;46(5):387–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bajwah S, Yorke J. Palliative care and interstitial lung disease. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2017;11(3):141–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Research NIoN. Palliative Care - The Relief You Need When You Have a Serious Illness 2018. [Available from: https://www.ninr.nih.gov/sites/files/docs/palliative-care-brochure.pdf.

- 32.Beernaert K, Cohen J, Deliens L, Devroey D, Vanthomme K, Pardon K, et al. Referral to palliative care in COPD and other chronic diseases: A population-based study. Respir Med. 2013;107(11):1731–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lindell K, Liang Z, Hoffman L, Rosenzweig M, Saul M, Pilewski J, Gibson K, Kaminski N. Palliative Care and Location of Death in Decedents with Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Chest. 2015;147 (2):423–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brown C, Jecker NS, and Curtis JR. Inadequate Palliative Care in Chronic Lung Disease. AnnalsATS. 2016;13(3):311–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.**.Kreuter M, Bendstrup E, Russell AM, Bajwah S, Lindell K, Adir Y, Brown CE, Calligaro G,, Cassidy N, Corte TJ, Geissler K, Hassan AA, Johannson KA, Kairalla R, Kolb M, Kondoh Y,, Quadrelli S, Swigris J, Udwadia Z, Wells A, & Wijsenbeek M. Palliative care in interstitial lung disease: living well. Lancet Respir Med. 2017. This manuscript details unmet patient and caregiver needs and addresses effective pharmacological and psychosocial interventions to improve quality of life throughout the disease course, sensitive advanced care planning, and timely patient-centred end-of-life care. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ferrara G, Luppi F, Birring SS, Cerri S, Caminati A, Skold M, & Kreuter M. Best supportive care for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: current gaps and future directions. European respiratory review : an official journal of the European Respiratory Society. 2018;27:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Curtis J, Downey L, Back AL, Nielsen EL, Sudiptho P, Lahdya AZ, Treece PD, Armstrong P, Peck R, & Engleberg RA. Effect of a Patient and Clinician Communication-Priming Intervention on Patient-Reported Goals of Care Discussions Between Patients with Serious Illness and Clinicians: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Internal Med. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reinke L, Janssen D, & Curtis JR. Palliative care issues in adults with nonmalignmant pulmonary disease. 2015. In: Up to Date [Internet].

- 39.O’Connor NC,DJ. Which Patients Need Palliative Care Most? Challenges of Rationing in Medicine’s Newest Speciaity. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maciasz RMAR, Chu E, Park SY, White DB, Vater LB, Schenker Y. . Does it matter what you call it? A randomized trial of language used to describe palliative care services. Supportive care in cancer : official journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer. 2013;21:3411–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dahlin C National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care, Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care. 2013(3rd Ed).

- 42.National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization CaringInfo [Available from: http://www.caringinfo.org/i4a/pages/index.cfm?pageid=1.

- 43.Get Palliative Care [Available from: https://getpalliativecare.org/howtoget/find-a-palliative-care-team/.

- 44.Hansen-Flaschen J Advanced lung disease. Palliation and terminal care. Clin Chest Med. 1997;18(3):645–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Johnson MJJA, Ross J, Fairhurst C, Boland J, Reigada C, Hart SP, Grande G, Currow DC, Wells AU, Bajwah S, Papadopoulos T, Bland JM & Yorke J. Psychometric validation of the needs assessment tool: progressive disease in interstitial lung disease. Thorax. 2017;0:1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Duck ASL, Bailey S, Leonard C, Ormes J, Caress AL. Perceptions, experiences and needs of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. J Adv Nurs. 2015;71(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Russell AMOS, Lines S, Murphy A, Hocking J, Newell K, Morris H, Harris E, Dixon C, Agnew S, & Burge G. Contemporary challenges for specialist nursing in interstitial lung disease. Breathe. 2018;14:36–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.