Abstract

Background

Effective oral hygiene measures carried out on a regular basis are vital to maintain good oral health. One‐to‐one oral hygiene advice (OHA) within the dental setting is often provided as a means to motivate individuals and to help achieve improved levels of oral health. However, it is unclear if one‐to‐one OHA in a dental setting is effective in improving oral health and what method(s) might be most effective and efficient.

Objectives

To assess the effects of one‐to‐one OHA, provided by a member of the dental team within the dental setting, on patients' oral health, hygiene, behaviour, and attitudes compared to no advice or advice in a different format.

Search methods

Cochrane Oral Health's Information Specialist searched the following databases: Cochrane Oral Health's Trials Register (to 10 November 2017); the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2017, Issue 10) in the Cochrane Library (searched 10 November 2017); MEDLINE Ovid (1946 to 10 November 2017); and Embase Ovid (1980 to 10 November 2017). The US National Institutes of Health Ongoing Trials Register (ClinicalTrials.gov) and the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform were also searched for ongoing trials (10 November 2017). No restrictions were placed on the language or date of publication when searching the electronic databases. Reference lists of relevant articles and previously published systematic reviews were handsearched. The authors of eligible trials were contacted, where feasible, to identify any unpublished work.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials assessing the effects of one‐to‐one OHA delivered by a dental care professional in a dental care setting with a minimum of 8 weeks follow‐up. We included healthy participants or participants who had a well‐defined medical condition.

Data collection and analysis

At least two review authors carried out selection of studies, data extraction and risk of bias independently and in duplicate. Consensus was achieved by discussion, or involvement of a third review author if required.

Main results

Nineteen studies met the criteria for inclusion in the review with data available for a total of 4232 participants. The included studies reported a wide variety of interventions, study populations, clinical outcomes and outcome measures. There was substantial clinical heterogeneity amongst the studies and it was not deemed appropriate to pool data in a meta‐analysis. We summarised data by categorising similar interventions into comparison groups.

Comparison 1: Any form of one‐to‐one OHA versus no OHA

Four studies compared any form of one‐to‐one OHA versus no OHA.

Two studies reported the outcome of gingivitis. Although one small study had contradictory results at 3 months and 6 months, the other study showed very low‐quality evidence of a benefit for OHA at all time points (very low‐quality evidence).

The same two studies reported the outcome of plaque. There was low‐quality evidence that these interventions showed a benefit for OHA in plaque reduction at all time points.

Two studies reported the outcome of dental caries at 6 months and 12 months respectively. There was very low‐quality evidence of a benefit for OHA at 12 months.

Comparison 2: Personalised one‐to‐one OHA versus routine one‐to‐one OHA

Four studies compared personalised OHA versus routine OHA.

There was little evidence available that any of these interventions demonstrated a difference on the outcomes of gingivitis, plaque or dental caries (very low quality).

Comparison 3: Self‐management versus professional OHA

Five trials compared some form of self‐management with some form of professional OHA.

There was little evidence available that any of these interventions demonstrated a difference on the outcomes of gingivitis or plaque (very low quality). None of the studies measured dental caries.

Comparison 4: Enhanced one‐to‐one OHA versus one‐to‐one OHA

Seven trials compared some form of enhanced OHA with some form of routine OHA.

There was little evidence available that any of these interventions demonstrated a difference on the outcomes of gingivitis, plaque or dental caries (very low quality).

Authors' conclusions

There was insufficient high‐quality evidence to recommend any specific one‐to‐one OHA method as being effective in improving oral health or being more effective than any other method. Further high‐quality randomised controlled trials are required to determine the most effective, efficient method of one‐to‐one OHA for oral health maintenance and improvement. The design of such trials should be cognisant of the limitations of the available evidence presented in this Cochrane Review.

Plain language summary

One‐to‐one oral hygiene advice for oral health

Review question

The aim of this review was to assess the effects of one‐to‐one oral hygiene advice, provided by a member of the dental team within the dental setting, on patients' oral health, hygiene, behaviour, and attitudes compared to no advice or advice in a different format.

Background

Poor oral hygiene habits are known to be associated with high rates of dental decay and gum disease. The dental team routinely assess oral hygiene methods, frequency and effectiveness or otherwise of oral hygiene routines carried out by their patients; one‐to‐one oral hygiene advice is regularly provided by members of the dental team with the aim of motivating individuals and improving their oral health. The most effective method of delivering one‐to‐one advice in the dental setting is unclear. This review's aim is to determine if providing patients with one‐to‐one oral hygiene advice in the dental setting is effective and if so what is the best way to deliver this advice.

Study characteristics

Authors from Cochrane Oral Health carried out this review and the evidence is up to date to 10 November 2017. We included research where individual patients received oral hygiene advice from a dental care professional on a one‐to‐one basis in a dental clinic setting with a minimum of 8 weeks follow‐up.

In total, within the identified 19 studies, oral hygiene advice was provided by a hygienist in eight studies, dentist in four studies, dental nurse in one study, dentist or hygienist in one study, dental nurse and hygienist in one study, and dental nurse oral hygiene advice to the control group with further self‐administration of the intervention in one study. It was unclear in three of the studies which member of the dental team carried out the intervention. Over half of the studies (10 of the 19) were conducted in a hospital setting, with only five studies conducted in a general dental practice setting (where oral hygiene advice is largely delivered).

Key results

Overall we found insufficient evidence to recommend any specific method of one‐ to‐one oral hygiene advice as being more effective than another in maintaining or improving oral health.

The studies we found varied considerably in how the oral hygiene advice was delivered, by whom and what outcomes were looked at. Due to this it was difficult to readily compare these studies and further well designed studies should be conducted to give a more accurate conclusion as to the most effective method of maintaining or improving oral health through one‐to‐one oral hygiene advice delivered by a dental care professional in a dental setting.

Quality of the evidence

We judged the quality of the evidence to be very low due to problems with the design of the studies.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Dental caries and periodontal disease are the two most prevalent dental conditions globally; both are largely preventable. The accumulation of dental plaque, a microbial biofilm on the tooth surface is a primary aetiological factor in both diseases (Löe 1965; Löe 1972).

When the microbial biofilm is exposed to carbohydrate sources via the host's diet it can lead to the localised lowering of the pH which results in the chemical dissolution of the tooth surface (Sheiham 2015). If this process goes undisturbed the caries process can lead to a lesion or 'cavity' in the exposed tooth. Although the affected carious tooth often remains asymptomatic in the early stages of the disease, the longer term consequences can be toothache, sepsis or ultimately tooth loss. Estimates of the prevalence of caries varies worldwide but the 2010 global burden of disease study estimated that untreated caries in permanent teeth was the most prevalent condition worldwide affecting an estimated 2.4 billion people (Kassebaum 2015). Self‐care prevention strategies include: reducing free sugars intake; disruption of plaque biofilm (toothbrushing and interdental cleaning aids); using a fluoride dentifrice or fluoride mouthwash or both (Marinho 2003; Marinho 2004a; Marinho 2004b; Marinho 2016). Self‐care strategies can be supplemented by professional interventions including fluoride gels and varnishes (Marinho 2003; Marinho 2004a; Marinho 2004b).

The accumulation of dental plaque also results in the inflammation of the periodontium (supporting structures) of the teeth. The undisturbed plaque biofilm initially causes swelling, loss of texture, characteristic redness of the gingiva and liability to gingival bleeding (gingivitis). At this early stage the disease is reversible by the disruption of the dysbiotic pathogenic biofilm allowing a return to healthy periodontal tissues. Periodontal disease, like dental caries often goes unnoticed by patients at its earliest stages. If left undisturbed in susceptible patients, gingival inflammation can lead to the irreversible loss of supporting structures (periodontitis), which can present as gingival recession, sensitivity of the exposed root, tooth mobility, drifting of the teeth or ultimately tooth loss. Studies suggest that 50% to 90% of adults in the UK and USA have gingivitis. The global burden of disease study estimated that severe periodontitis affects approximately 11% of the global population or 743 million people worldwide (Kassebaum 2014).

Oral self‐care prevention involves disruption of the plaque biofilm (toothbrushing and interdental cleaning aids) (Poklepovic 2013; Yaacob 2014) and control of systemic risk factors (e.g. smoking) (Tonetti 2017). There is evidence to suggest effective dental plaque control sustained over the longer term can achieve reduced experience of periodontal disease, dental caries and ultimately tooth mortality rates (Axelsson 2004).

Description of the intervention

The patient's own oral self‐care is a crucial component of the prevention strategies for dental caries and periodontal disease. Ultimately the aim of oral hygiene advice (OHA) is to enable a patient to improve their own oral self‐care and consequently their oral health. To improve a patient's oral self‐care, OHA can be delivered in a variety of formats by any appropriately trained member of the dental team. The content of OHA can include: toothbrushing and toothpaste advice, interdental cleaning advice, mouthwash advice, denture hygiene advice and/or orthodontic fixed/removable appliance hygiene advice.

How the intervention might work

OHA may work through improving patient knowledge, attitudes, and behaviours. Helping patients to understand their disease process and the preventative actions required may motivate them to change their oral self‐care behaviours thus reducing their risk of oral disease. In addition, OHA may improve patients' confidence in carrying out oral self‐care and/or highlight barriers and enablers to facilitate improved oral self‐care. Adequate oral hygiene regimens help prevent dental caries and periodontal disease.

Why it is important to do this review

Current clinical guidance recommends that OHA should be reinforced regularly and tailored to individual patients' needs to attain sustainable benefits (NICE 2015). Advice or information regarding toothbrushing is currently not uniformly provided to all patients. In England in 2009, 78% of adults reported receiving advice on cleaning their teeth and gums, an increase from 63% in 1998 (Chadwick 2011). Within the child population, oral health advice varies widely in both content and to whom it is provided (Tickle 2003) with younger children being less likely to receive advice than older children (Tsakos 2015).

Although OHA is taught as an obligatory part of the undergraduate dental curriculum (given OHA frequently forms part of routine dental care), there remains uncertainty as to how, where and by whom OHA should be provided to be effective. Previously, the main focus of preventing oral disease has been to increase patient knowledge and awareness regarding oral health, with the hope that this would lead to improved oral health status (Towner 1993). This has been superceded by oral health promotion, which aims not only to increase public knowledge, but also to utilise a multidisciplinary approach aimed at the underlying determinants of oral health (WHO 1986; WHO 2003). A systematic review of oral health promotion concluded that the evidence for long‐term reduction in plaque and gingival bleeding outcomes, based on mainly short‐term interventions, was limited. There were also conflicting conclusions regarding the relative effectiveness of different types/styles of educational interventions employed (Watt 2005). A recent systematic review of psychological approaches to behaviour change for improved plaque control in periodontal management concluded that interventions based on the use of goal setting, self‐monitoring and planning are effective in improving oral health‐related behaviours as assessed by oral health status (Newton 2015), although these conclusions were based upon observational studies as well as randomised controlled trials.

Although there are a variety of healthcare professionals who may be involved in the delivery of OHA, both within the dental surgery and within the wider community setting, there does not appear to be any systematic reviews published previously which assess the effect of the individual providing OHA.

Objectives

To assess the effects of one‐to‐one oral hygiene advice, provided by a member of the dental team within the dental setting, on patients' oral health, hygiene, behaviour, and attitudes compared to no advice or advice in a different format.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included all randomised controlled trials (RCTs) in which participants who were provided with one‐to‐one oral hygiene advice (OHA) by a member of the dental team in the dental setting were compared to participants not provided with OHA. We also included RCTs which compared different formats (e.g. DVD, leaflet, video, etc.) of one‐to‐one OHA provided within the dental setting or OHA provided by different members of the dental team within the dental setting. We only included studies with a minimum follow‐up period of 8 weeks. The unit of randomisation could be individual participants, clusters of individuals, or dental setting.

Types of participants

We included studies that involved children (with or without guardian/parent) or adult participants who were fit and healthy or groups of individuals who had well defined medical conditions. Studies involving participants who wore a removable prosthesis or orthodontic appliance of any kind were excluded.

Types of interventions

We included studies that involved OHA being provided by any member of the dental team within the dental setting environment (i.e. within a general dental practice, community dental setting or dental hospital setting) on a one‐to‐one basis in which the comparator was no advice or advice in an alternative format or advice from a different member of the dental team. Dental team members included dentist, dental nurse, dental hygienist and dental therapist. Studies were included if the OHA took place alongside an intervention aiming to change dietary behaviour or smoking behaviour, although these multi‐intervention studies were planned to be subjected to a subgroup analysis if any such studies had met the inclusion criteria.

We excluded any studies where additional measures were provided to the intervention group but not the control group (e.g. dental prophylaxis, dental scaling, application or provision of fluoride containing products, provision of toothbrushes, etc.).

Types of outcome measures

Outcome measures considered in this review included clinical status, patient‐centred and economic factors. The outcome measure must have been assessed at least 8 weeks following the intervention.

Primary outcomes

Clinical status factors

Periodontal health (e.g. plaque levels, gingivitis, and probing depths).

Caries (e.g. dmft/DMFT or other indices).

Secondary outcomes

Patient‐centred factors

Patient‐reported behaviour changes (e.g. toothbrushing/flossing/mouthwash use).

Patient satisfaction with advice provided.

Patient‐reported changes in knowledge, attitudes, and quality of life.

Economic factors

Cost effectiveness.

Other outcomes

Any adverse events due to OHA reported in the included trials.

Search methods for identification of studies

Cochrane Oral Health's Information Specialist conducted systematic searches in the following databases for RCTs and controlled clinical trials. There were no language, publication year or publication status restrictions:

Cochrane Oral Health's Trials Register (searched 10 November 2017) (Appendix 1);

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2017, Issue 10) in the Cochrane Library (searched 10 November 2017) (Appendix 2);

MEDLINE Ovid (1946 to 10 November 2017) (Appendix 3);

Embase Ovid (1980 to 10 November 2017) (Appendix 4).

Subject strategies were modelled on the search strategy designed for MEDLINE Ovid. Where appropriate, they were combined with subject strategy adaptations of the highly sensitive search strategy designed by Cochrane for identifying randomised controlled trials and controlled clinical trials as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Chapter 6 (Lefebvre 2011).

Searching other resources

The following trial registries were searched for ongoing studies:

US National Institutes of Health Ongoing Trials Register ClinicalTrials.gov (clinicaltrials.gov; searched 10 November 2017) (Appendix 5);

World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (apps.who.int/trialsearch; searched 10 November 2017) (Appendix 6).

Bibliographic references of identified RCTs and articles identified as relevant to the review retrieved in the electronic search were also searched (e.g. review articles and systematic reviews). In addition, emails were sent to authors of identified potentially eligible RCTs asking them for other known unpublished or ongoing research. Relevant sections of the reports were translated of non‐English publications identified from title, abstract, or keyword, to be of interest.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

The search was designed to be sensitive and included controlled clinical trials, these were filtered out early in the selection process if they were not randomised.

At least two review authors reviewed and analysed independently all reports identified by the search on the basis of title, keywords, and abstract (where this was available) to see if the study was likely to be relevant. Where it was not possible to classify an article based on title, keywords and abstract, we obtained the full article. The full report was obtained of all potentially eligible studies, and also of studies where the title/abstract provided insufficient information to make a decision on eligibility.

The review authors were not blinded with respect to report authors, journals, date of publication, sources of financial support, or results. The inclusion criteria, as outlined above, were applied and those studies deemed suitable for inclusion by at least two review authors were included. We contacted study authors for missing information or clarity regarding methods, results, etc. where required and feasible. We linked multiple publications of the same study under one single study title. Those studies excluded are cited with reasons for exclusion reported.

Two review authors independently and in duplicate assessed the eligibility of the non‐English language reports. Relevant sections of the reports were translated with the assistance of Cochrane Oral Health and non‐English reports that met the inclusion criteria had data extraction and risk of bias completed.

Data extraction and management

A data extraction form was designed and piloted prior to full use. At least two review authors independently extracted data from each of the potentially eligible studies; any disagreements between the two review authors undertaking data extraction was resolved by discussion and if necessary the involvement of a third review author. If necessary we contacted the study author, where possible, to clarify any unclear or inadequate characteristics before a final decision on inclusion was made. Data recorded included the following:

general study information: authors, title, year research completed, year research published, country, ethics and consent process, financial support and conflicts of interest, country, contact address;

methods: research objective, sample size calculation, allocation procedures, follow‐up period, degree of blindness in outcome assessment;

participants: inclusion/exclusion criteria, age, medical factors, baseline periodontal health/caries status/behaviours/knowledge/attitudes/quality of life;

intervention and comparators: type of OHA, format of OHA, advice duration, advice frequency, personnel providing advice;

outcomes: primary and secondary outcomes and outcome measures.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The risk of bias of included trials for the seven domains of random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, and other potential sources for bias was undertaken independently and in duplicate by at least two review authors as part of the data extraction process and in accordance with the guidelines in theCochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions 5.1.0 (Higgins 2011). Where possible, we contacted study authors for missing information or clarification of their study methods. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion between the review authors with Cochrane Oral Health being consulted where there was continuing disagreement.

We allocated the level of bias for each domain as high or low as per the criteria below; for those domains where insufficient information was available or not described in sufficient detail to allow a definitive judgement then the level of bias was recorded as unclear.

Random sequence generation

Low: the investigators describe a random component in the sequence generation process such as referring to a random number table, using a computer random number generator, etc..

High: the investigators describe a non‐random component in the sequence generation process. Usually, the description would involve some systematic, non‐random approach, (e.g. sequence generated by odd or even date of birth, etc.).

Allocation concealment

Low: participants and investigators enrolling participants could not foresee assignment because an appropriate method was used to conceal allocation (e.g. central allocation, etc.).

High: participants or investigators enrolling participants could possibly foresee assignments and thus introduce selection bias, such as allocation based on using an open random allocation schedule, etc..

Blinding of participants and personnel

Low: no blinding or incomplete blinding, but the review authors judge that the outcome is not likely to be influenced by lack of blinding.

High: no blinding or incomplete blinding, and the outcome is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding.

Blinding of outcome assessment

Low: no blinding of outcome assessment, but the review authors judge that the outcome measurement is not likely to be influenced by lack of blinding; blinding of outcome assessment ensured, and unlikely that the blinding could have been broken.

High: no blinding of outcome assessment, and the outcome measurement is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding; blinding of outcome assessment, but likely that the blinding could have been broken, and the outcome measurement is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding.

Incomplete outcome data

Low: no missing outcome data; reasons for missing outcome data unlikely to be related to true outcome (for survival data, censoring unlikely to be introducing bias); missing outcome data balanced in numbers across intervention groups, with similar reasons for missing data across groups; for dichotomous outcome data, the proportion of missing outcomes compared with observed event risk not enough to have a clinically relevant impact on the intervention effect estimate; for continuous outcome data, plausible effect size (difference in means or standardized difference in means) among missing outcomes not enough to have a clinically relevant impact on observed effect size; missing data have been imputed using appropriate methods.

High: reason for missing outcome data likely to be related to true outcome, with either imbalance in numbers or reasons for missing data across intervention groups; for dichotomous outcome data, the proportion of missing outcomes compared with observed event risk enough to induce clinically relevant bias in intervention effect estimate; for continuous outcome data, plausible effect size (difference in means or standardized difference in means) among missing outcomes enough to induce clinically relevant bias in observed effect size; 'as‐treated' analysis done with substantial departure of the intervention received from that assigned at randomisation; potentially inappropriate application of simple imputation.

Selective reporting

Low: the study protocol is available and all of the study's pre‐specified (primary and secondary) outcomes that are of interest in the review have been reported in the pre‐specified way.

High: not all of this study's pre‐specified primary outcomes have been reported; one or more primary outcomes is reported using measurements, analysis methods or subsets of the data (e.g. subscales) that were not pre‐specified; one or more reported primary outcomes were not pre‐specified (unless clear justification for their reporting is provided, such as an unexpected adverse effect); one or more outcomes of interest in the review are reported incompletely so that they cannot be entered in a meta‐analysis; the study report fails to include results for a key outcome that would be expected to have been reported for such a study.

Other potential sources for bias

Low: the study appears to be free of other sources of bias.

High: there is as least one important risk of bias, for example a potential source of bias related to the specific study design used.

We summarised the risk of bias as follows.

| Risk of bias | In outcome | In included studies |

| Low risk of bias | Low risk of bias in all key domains | Most information is from studies at low risk of bias |

| Unclear risk of bias | Unclear risk of bias for one or more key domains | Most information is from studies at low or unclear risk of bias |

| High risk of bias | High risk of bias for one or more key domains | The proportion of information from studies at high risk is sufficient to affect the interpretation of results |

Measures of treatment effect

For continuous outcomes (e.g. plaque/gingivitis scores), where studies used the same scale, we used the mean values and standard deviations reported in the studies in order to express the estimate of effect of the intervention as mean difference (MD) with 95% confidence interval (CI). Where different scales were used, we expressed the treatment effect as standardised mean difference (SMD) and 95% CI.

For dichotomous outcomes (e.g. attachment loss/no attachment loss), we expressed the estimate of effect as a risk ratio (RR) with 95% CI. Had we included any cross‐over studies, we would have extracted appropriate data following the methods outlined by Elbourne 2002, and would have used the generic inverse variance method to enter log RRs or MD/SMD and standard error into Review Manager 5 (Review Manager 2014).

Unit of analysis issues

The participant was the unit of analysis. Had we included any cross‐over studies, these should have analysed data using a paired t‐test, or other appropriate statistical test, to take into account the paired nature of the data. Cluster‐RCTs should have analysed results taking account of the clustering present in the data, otherwise we would have used the methods outlined in Section 16.3.4 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions in order to perform an approximately correct analysis (Higgins 2011).

Dealing with missing data

We attempted, where feasible, to contact the author(s) of studies to obtain missing data or for clarification. We did not use any further statistical methods or carry out any further imputation to account for missing data.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Heterogeneity was assessed by examining the types of participants, interventions and outcomes in each study. It was agreed in advance that meta‐analysis would only be attempted if studies of similar comparisons reporting the same outcome measures were included in the review.

If it had been appropriate to perform meta‐analysis, we would have assessed the possible presence of heterogeneity visually by inspecting the point estimates and CIs on the forest plots; if the CIs had poor overlap then heterogeneity would have been considered to be present. We would also have assessed heterogeneity statistically using a Chi2 test, where a P value < 0.1 would have been considered to indicate statistically significant heterogeneity. Furthermore, we would have quantified heterogeneity using the I2 statistic. A guide to interpretation of the I2 statistic given in Section 9.5.2 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions is as follows (Higgins 2011):

0% to 40%: might not be important;

30% to 60%: may represent moderate heterogeneity;

50% to 90%: may represent substantial heterogeneity;

75% to 100%: considerable heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

Assessment of reporting bias within studies has already been described in the section Assessment of risk of bias in included studies. Reporting biases can occur when reporting (or not reporting) research findings is related to the results of the research (e.g. a study that did not find a statistically significant difference/result may not be published). Reporting bias can also occur if ongoing studies are missed (but that may be published by the time the systematic review is published), or if multiple reports of the same study are published, or if studies are not included in a systematic review due to not being reported in the language of the review authors. If there had been more than 10 studies included in a meta‐analysis, we would have assessed the possible presence of reporting bias by testing for asymmetry in a funnel plot. If present, we would have carried out statistical analysis using the methods described by Egger 1997 for continuous outcomes and Rücker 2008 for dichotomous outcomes. However, we did attempt to limit reporting bias in the first instance by conducting a detailed, sensitive search, including searching for ongoing studies, and any studies not reported in English were translated by a member of Cochrane Oral Health.

Data synthesis

We would only have carried out a meta‐analysis where studies of similar comparisons reported the same outcomes. We would have combined MDs (we would have used SMD where studies had used different scales) for continuous outcomes, and would have combined RRs for dichotomous outcomes, using a fixed‐effect model if there were only two or three studies, or a random‐effects model if there were four or more studies.

We would have used the generic inverse variance method to include data from cross‐over studies in meta‐analyses as described in Section 16.4 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Elbourne 2002; Higgins 2011). Where appropriate, we would have combined the results from cross‐over studies with parallel group studies, using the methods described by Elbourne 2002.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

If it had been required, subgroup analyses would have been undertaken where OHA had taken place alongside an intervention aiming to change dietary behaviour or smoking behaviour, personnel providing advice and frequency of advice.

If there had been a number of similar studies, sensitivity analysis would have been considered to determine whether conclusions reached would be affected by different inclusion criteria. However, given the heterogeneity of studies included this was not required.

Presentation of main results

We produced a 'Summary of findings' table for each comparison. We included gingivitis, plaque and dental caries. We used GRADE methods (GRADE 2004), and the GRADEpro GDT online tool for developing 'Summary of findings' tables (www.guidelinedevelopment.org). We assessed the quality of the body of evidence for each comparison and outcome by considering the overall risk of bias of the included studies, the directness of the evidence, the inconsistency of the results, the precision of the estimates, and the risk of publication bias. We categorised the quality of each body of evidence as high, moderate, low, or very low.

Results

Description of studies

See Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; Characteristics of studies awaiting classification; Characteristics of ongoing studies.

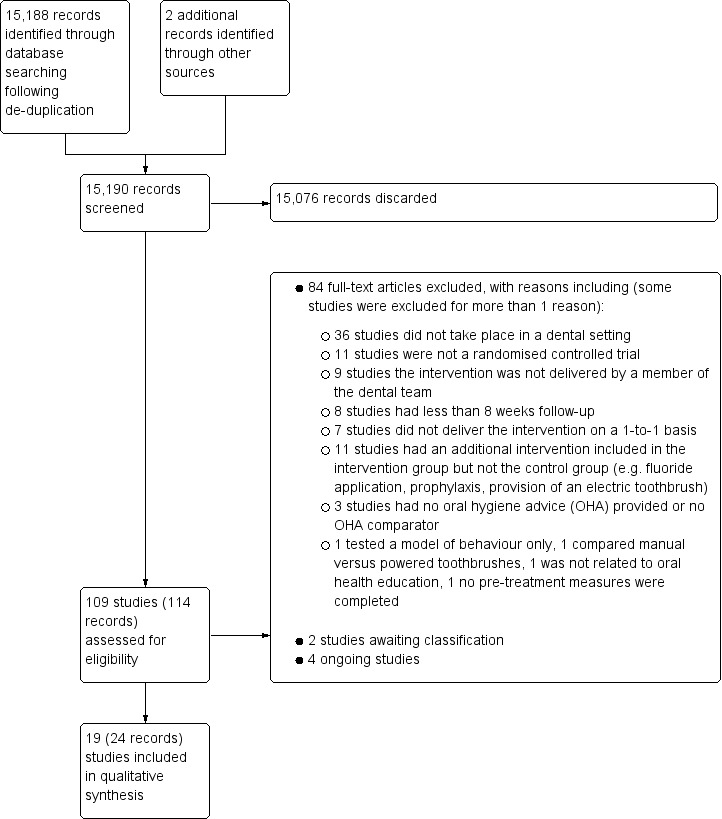

Results of the search

The literature search resulted in 15,188 references following de‐duplication. In addition, we also handsearched the references of seven relevant systematic reviews (Harris 2012; Kay 1998; Kay 2016a; Kay 2016b; Khokhar 2016; Newton 2015; Yevlahova 2009) and two reviews (Pastagia 2006; Watt 2005), identifying two further studies (Hetland 1982; Little 1997). Four review authors screened the titles and abstracts against the inclusion criteria for this review, independently and in duplicate, and 15,076 references were found to be ineligible for this review (including four potentially eligible references but they had abstracts‐only published with no further information regarding the study available). Full‐text copies of the remaining references were obtained and examined independently and in duplicate, excluding 84 studies at this stage. Two studies are awaiting classification and four are ongoing. Nineteen studies reported in 24 papers met the inclusion criteria for this review. Handsearching of the references of included studies and correspondence from authors identified no further studies for inclusion. This process is illustrated in Figure 1 PRISMA flow diagram.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

Characteristics of trial design and setting

Nineteen studies met the inclusion criteria of the review and were included (Characteristics of included studies). All 19 studies were of parallel‐group design, 10 of which had two trial arms (Aljafari 2017; Baab 1986; Bali 1999; Glavind 1985; Jönsson 2006; Jönsson 2009; Lepore 2011; López‐Jornet 2014; Münster Halvari 2012; Tedesco 1992), four of which had three arms (Hetland 1982; Hoogstraten 1983; Memarpour 2016; Söderholm 1982), two of which had four arms (Hugoson 2007; Weinstein 1996), and two of which had six arms (Schmalz 2018; Van Leeuwen 2017). One study was a cluster‐randomised design with oral hygiene advice (OHA) randomised by cluster (routine or personalised OHA) and scale and polish treatment by parallel randomisation with three arms (Ramsay 2018).

Ten of the included studies were conducted in hospital/graduate clinics (Aljafari 2017; Baab 1986; Bali 1999; Jönsson 2006; Jönsson 2009; Lepore 2011; López‐Jornet 2014; Schmalz 2018; Söderholm 1982; Van Leeuwen 2017), four in a dental practice setting (Glavind 1985; Hoogstraten 1983; Münster Halvari 2012; Ramsay 2018), one in public healthcare settings (Memarpour 2016), one study involved one clinic in a public dental setting and the other a general dental practice (Hugoson 2007), one was in a factory which had two dental units and chairs installed for the purpose of the study (Hetland 1982), and two trials did not specify which dental setting they were conducted in (Tedesco 1992; Weinstein 1996).

Fifteen of the studies were single centre with one study reporting two centres (Hugoson 2007), one study with three centres (Glavind 1985), one study with five centres (Memarpour 2016), and one study with 63 centres (Ramsay 2018).

Four studies were conducted in Sweden (Hugoson 2007; Jönsson 2006; Jönsson 2009; Söderholm 1982), three in the USA (Baab 1986; Lepore 2011; Tedesco 1992), two in the Netherlands (Hoogstraten 1983; Van Leeuwen 2017), two in Norway (Hetland 1982; Münster Halvari 2012), one in Germany (Schmalz 2018), and one in Denmark (Glavind 1985), Spain (López‐Jornet 2014), Italy (Weinstein 1996), England (Aljafari 2017), Austria (Bali 1999), Iran (Memarpour 2016), and one study across the United Kingdom in Scotland and North East England (Ramsay 2018).

Only seven studies mentioned sample size calculations (Aljafari 2017; Jönsson 2009; Memarpour 2016; Münster Halvari 2012; Ramsay 2018; Schmalz 2018; Van Leeuwen 2017). Four of these studies achieved their sample sizes and had the required number of participants at follow‐up (Memarpour 2016; Münster Halvari 2012; Ramsay 2018; Schmalz 2018). Jönsson 2009 reported their sample size calculation but noted that they did not recruit or follow up this number of participants; the original examiner could not continue to complete recruitment and a second examiner could not be recruited in time. The authors also noted that the original power analysis was based on an intervention that was less effective than the intervention investigated in their study. Aljafari 2017 reported that only 55% of the recruited sample completed the telephone follow‐up 3 months after the child's dental care under general anaesthetic; the authors recommended the results be interpreted with caution given the sample size calculation deemed a sample of 45 participants in each group would have been required to provide 80% power, at the 5% significance level, to detect effects of 0.6 and above. At 3‐month follow‐up there were 28 patients and 31 patients available from the intervention and control group, respectively (Aljafari 2017). Van Leeuwen 2017 achieved their sample size in five of the six groups at 13 months such that the recruitment target was achieved at the 4‐month review for all groups, but not thereafter.

Eleven studies reported their funding source with six having received some form of public funding (Aljafari 2017; Baab 1986; Hugoson 2007; Münster Halvari 2012; Ramsay 2018; Tedesco 1992), one with dental association research funds (Glavind 1985), one with national health research and development funding (Van Leeuwen 2017 ), one with a university grant (Memarpour 2016), and one study reported joint funding sources between research council, public funding and the Pfizer oral care award (Jönsson 2009). One study acknowledged Philips GmbH (Hamburg, Germany), CP GABA (GmbH, Hamburg, Germany), and GlaxoSmithKline Oral Health Care GmbH (Brühl, Germany) for providing materials for the study (Schmalz 2018).

Characteristics of the participants

A total of 4232 participants were recruited, with numbers included in each trial ranging from 33 to 1877. Three studies investigated children with a mean age of 20 months, 3 years and six years old and age ranges from 1 year to 10 years old (Aljafari 2017; Lepore 2011; Memarpour 2016). In the remaining adult population studies, the age range of the sample was reported in 15 studies with the mean age of adults ranging from 20 years to 58 years old and age range from 15 years to 91 years old (Baab 1986; Bali 1999; Glavind 1985; Hetland 1982; Hoogstraten 1983; Jönsson 2006; Jönsson 2009; López‐Jornet 2014; Münster Halvari 2012; Ramsay 2018; Schmalz 2018; Söderholm 1982; Tedesco 1992; Van Leeuwen 2017; Weinstein 1996).

Two studies restricted their inclusion criteria to participants who were known to have a specific medical condition: diabetes (Bali 1999) and hyposalivation (López‐Jornet 2014).

The dental condition pre‐treatment required participants to be caries free in three studies (Memarpour 2016; Schmalz 2018; Van Leeuwen 2017) and only those with caries were included in another study (Aljafari 2017). Eight studies reported that the included individuals were only those with plaque present (Glavind 1985) or those who had active or previously treated periodontal disease patients (Baab 1986; Glavind 1985; Jönsson 2006; Jönsson 2009; Tedesco 1992; Van Leeuwen 2017; Weinstein 1996). One study reported including those individuals with healthy periodontal status, gingivitis or moderate periodontal disease (Ramsay 2018). One study specified that there were to be no periodontal pockets ≥4.0 mm, as measured by a pocket probe, and/or serious bone loss visualized by digital X rays during the dental examination (Münster Halvari 2012), and another specified there to be no periodontal attachment loss greater than 1.5 mm, radiographic evidence of bone loss greater than 25% (anterior/posterior bite‐wing radiographs or periapical radiographs), or previous periodontal therapy (Tedesco 1992); another specified there to be no pockets of 4 mm to 5 mm in combination with gingival recession or pockets of ≥ 6 mm, as assessed according to the Dutch Periodontal Screening Index (DPSI) scores 3+ and 4 (Van Leeuwen 2017).

Characteristics of the interventions

Intervention type

A variety of interventions were used in the included studies, none of which were entirely identical.

Two studies used self‐inspection/instruction manuals (Baab 1986; Glavind 1985) with a further incorporating self‐assessment as part of the intervention (Weinstein 1996).

One study reported participants received one‐to‐one advice on toothbrushing technique (Schmalz 2018).

One used a computer game (Aljafari 2017), one included instruction and viewing of an educational film (Hoogstraten 1983), and another included showing patients a phase‐contrast slide of their own subgingival flora on a video monitor (Tedesco 1992).

One study reported the intervention group receiving once‐only professional individual oral hygiene instruction (Van Leeuwen 2017), one with a three‐visit oral hygiene instruction program delivered on a once a week basis (Hetland 1982), one with intensive patient education in oral hygiene with additional control examinations (Bali 1999), another providing oral hygiene instruction in addition to a pamphlet and toothbrush (Memarpour 2016), or similar instruction at a variable number of appointments (Söderholm 1982).

One study reported a motivational–behavioural skills protocol designed following principles of self‐efficacy theory (López‐Jornet 2014).

Six studies provided information tailored to the patients needs (Bali 1999; Hugoson 2007; Jönsson 2009; Lepore 2011; Ramsay 2018; Weinstein 1996), one of which was with the addition of cognitive behavioural therapy (Jönsson 2009), another including Social Cognitive Theory and Implementation Intention Theory (Ramsay 2018) and another with the inclusion of positive social reinforcement (Weinstein 1996).

A negotiation and self‐selected goals method described as Client Self‐Care Commitment Model was reported in one study (Jönsson 2006).

A competency enhancing intervention in addition to standard autonomy‐supportive treatment was described in one study (Münster Halvari 2012).

Member of dental team delivering intervention

It was unclear in three of the studies which member of the dental team carried out the intervention (Bali 1999; López‐Jornet 2014; Weinstein 1996) but after reviewing the text the review authors were confident the intervention was undertaken by a member of the dental team. In the remainder of the studies the interventions were delivered by various members of the dental team.

A hygienist delivered the intervention in eight of the studies (Baab 1986; Hoogstraten 1983; Hugoson 2007; Jönsson 2006; Jönsson 2009; Münster Halvari 2012; Tedesco 1992; Van Leeuwen 2017).

A dentist delivered the intervention in four studies (Glavind 1985; Lepore 2011; Memarpour 2016; Schmalz 2018).

A dentist or hygienist delivered the intervention in one study (Ramsay 2018).

A hygienist and dental nurse delivered the intervention in one study (Söderholm 1982).

A dental nurse delivered the intervention in one study (Hetland 1982) and control OHA in another study (Aljafari 2017).

Further self‐administration of the intervention at home took place in one study (Aljafari 2017).

Frequency of intervention

The frequency of the intervention varied with three studies reporting the intervention to be delivered on a one‐off basis (Lepore 2011; Schmalz 2018; Van Leeuwen 2017).The remaining studies reported various intervention frequencies other than one study being unclear (Hoogstraten 1983).

Two studies reported two intervention visits (Glavind 1985; Memarpour 2016).

Two studies reported three intervention visits (Hetland 1982; Jönsson 2006).

Four studies reported four intervention visits (Bali 1999; López‐Jornet 2014; Münster Halvari 2012; Tedesco 1992).

Two studies reported five intervention visits (Baab 1986; Söderholm 1982).

One study reported three or six intervention visits (Hugoson 2007).

One intervention was initially delivered in the clinic and then used at home as per the patients wishes (Aljafari 2017), one study reported a median of nine intervention visits (Jönsson 2009), and one reported reinforcement of OHA was provided at the discretion of the dentist/hygienist during the trial and recorded (Ramsay 2018). The study by Weinstein 1996 varied in the frequency of intervention from three clinical visits with twice weekly phone call to periodontist to report self‐evaluated plaque score, 16 visits with OHA (twice weekly examinations by periodontist) or 16 visits with OHA (twice weekly examinations by periodontist) and daily completion of an oral hygiene task checklist.

Intensity of intervention

The intensity of the intervention was not reported in nine studies (Baab 1986; Bali 1999; Jönsson 2006; Lepore 2011; Ramsay 2018; Schmalz 2018; Tedesco 1992; Weinstein 1996; Van Leeuwen 2017), two were largely administered at home (Aljafari 2017; Glavind 1985), one remained unclear (López‐Jornet 2014), and one varied between patients (Jönsson 2009).

For those studies who did report the intensity of the intervention, the intensity varied considerably.

Approximately 30 minutes to 40 minutes intervention noted in one study (Hoogstraten 1983).

Two intervention appointments of 30 minutes to 40 minutes each in one study (Memarpour 2016).

Forty‐five minutes for the first intervention visit, 30 minutes for the second intervention visit and 15 minutes for the third intervention visit in one study (Hetland 1982).

Approximately 45 minutes intervention was noted in one study (Münster Halvari 2012).

Between 120 minutes and 150 minutes was reported in two studies (Hugoson 2007; Söderholm 1982).

Prophylaxis as part of intervention

Twelve studies reported some form of prophylactic measures at baseline (Baab 1986; Glavind 1985; Hetland 1982; Hoogstraten 1983; Hugoson 2007; Jönsson 2006; Lepore 2011; Münster Halvari 2012; Ramsay 2018; Schmalz 2018; Söderholm 1982; Tedesco 1992). One study reported prophylactic measures throughout (Jönsson 2009) and six did not report any prophylactic measures (Aljafari 2017; Bali 1999; López‐Jornet 2014; Memarpour 2016; Van Leeuwen 2017; Weinstein 1996).

Characterictics of the outcomes

Primary outcomes ‐ Clinical status

Periodontal health

Gingivitis

Fifteen studies reported on the presence of gingivitis (Baab 1986; Bali 1999; Glavind 1985; Hetland 1982; Hugoson 2007; Jönsson 2006; Jönsson 2009; Lepore 2011; López‐Jornet 2014; Münster Halvari 2012; Ramsay 2018; Schmalz 2018; Söderholm 1982; Tedesco 1992; Van Leeuwen 2017).

Of these studies:

the gingival index by Löe and Sillness was used by seven studies (Hetland 1982; Hugoson 2007; Jönsson 2006; Jönsson 2009; Münster Halvari 2012; Schmalz 2018; Tedesco 1992);

bleeding on probing was reported in five studies (Baab 1986; Bali 1999; Glavind 1985; Ramsay 2018; Söderholm 1982);

gingival inflammation evaluated using the Papilla Bleeding Index (PBI) (Lange 1977) was reported in one study (Schmalz 2018);

one study (Van Leeuwen 2017) reported that gingival health was assessed at six sites (mesio‐buccal, mid‐buccal, disto‐buccal, mesio‐lingual, mid‐lingual and disto‐lingual) around the selected quadrants by scoring bleeding on marginal probing (BOMP) on a scale of 0 to 2 (Lie 1998; Van der Weijden 1994);

one study reported that gingival health was recorded but did not specify what scoring system was employed (Lepore 2011);

one study reported a bleeding index was recorded but did not specify what scoring system was employed (López‐Jornet 2014).

Probing depth

Four studies reported on probing depths (Bali 1999; Jönsson 2006; Jönsson 2009; Ramsay 2018). One study reported on Community Periodontal Index of Treatment Needs (CPITN) score (López‐Jornet 2014) with an additional study only reporting pocket depths of > 5 mm (Söderholm 1982), and a further study only reporting on pocket depths > 4 mm (Hetland 1982).

Plaque levels

Fifteen studies reported on plaque levels using various plaque indices (Baab 1986; Bali 1999; Glavind 1985; Hetland 1982; Hugoson 2007; Jönsson 2006; Jönsson 2009; Lepore 2011; López‐Jornet 2014; Münster Halvari 2012; Schmalz 2018; Söderholm 1982; Tedesco 1992; Van Leeuwen 2017; Weinstein 1996).

Of these studies:

three studies (Hugoson 2007; Münster Halvari 2012; Tedesco 1992) used the Löe and Sillness plaque index (Löe 1963; Löe 1967) with a further two studies (Jönsson 2006; Jönsson 2009) reporting the accumulation of plaque being recorded using Silness and Löe (Silness 1964);

one study (López‐Jornet 2014) reported a plaque extension index (PEI) following plaque disclosure using a 2% aqueous erythrosine solution. After rinsing once with water, plaque deposits were assessed using the Quigley and Hein index, modified by Turesky et al (Turesky 1970), with scores from 0 to 5 with another study (Van Leeuwen 2017) reporting a similar process by measuring plaque at six sites after disclosing with Mira‐2‐Ton® with scores also based on the modified Quigley and Hein (Quigley 1962) plaque index (QHPI) with a scale of 0 to 5. One study reported a similar method with plaque extension evaluated using the plaque index by Quigley and Hein (QHI) modified by Turesky et al after using a plaque disclosing agent (Mira‐2‐Ton®, Hager score 5 = plaque extending to the coronal third) in addition to recording the Marginal Plaque Index (MPI) by Deinzer et al to differentiate plaque extension at the gingival margin (Deinzer 2014) (Schmalz 2018). A further study also reported using the Turesky hygiene index (Bali 1999);

two studies (Baab 1986; Weinstein 1996) reported on presence or absence of disclosed plaque at the gingival margin (O'Leary 1972);

two studies reported on the presence of disclosed plaque; one did not refer to a specific index (Glavind 1985) and the other reported the percentage of tooth surfaces (mesial, buccal, distal and lingual) with plaque (Söderholm 1982);

two studies reported that a plaque score was recorded but did not specify what scoring system was employed (Hetland 1982; Lepore 2011).

Dental caries

Two studies reported on DMFT (number of decayed, missing or filled permanent teeth) (Bali 1999; Hetland 1982). One study reported on dmft (number of decayed, missing or filled primary teeth) (Memarpour 2016), and a further study reported on dental caries but appeared to use the terms DMFS (number of decayed, missing or filled permanent surfaces) and dmft interchangeably within the text of the primary paper (Lepore 2011).

Secondary outcomes ‐ Patient‐centred factors

Patient‐reported behaviour changes

Five studies reported on patient‐reported behaviour change regarding:

time spent brushing and the number of oral hygiene aids used (Baab 1986);

child's dietary habits, and the child's self‐reported snacking and toothbrushing practices (Aljafari 2017);

oral health behaviour (Ramsay 2018);

oral self‐care habits (Jönsson 2006);

self‐reported brushing and flossing behaviours and self‐efficacy assessed via Oral Health Behavior Expectation Scale (Tedesco 1992).

One of the studies specifically reported on patient‐reported health indices:

the General Oral Health Assessment Index (GOHAI) and self‐rated oral health (Jönsson 2009).

Patient satisfaction with advice provided

One study reported on patient satisfaction with provider of advice and patient satisfaction with advice format:

parent and child satisfaction with their educational intervention (Aljafari 2017).

Patient‐reported changes in knowledge, attitudes and quality of life

Five studies reported on patient‐reported changes in knowledge, attitudes and quality of life following provision of advice:

child's dietary knowledge (Aljafari 2017);

dental knowledge, attitude, behaviour, and fear of dental treatment (Hoogstraten 1983; Jönsson 2009);

patient‐related dental quality of life and confidence in oral hygiene self‐efficacy (Slade 1997) (Ramsay 2018);

parents' knowledge and performance regarding oral health (Memarpour 2016);

oral health‐related quality of life measure (OHQoL‐UK) (Jönsson 2009).

One study used multiple psychological outcome measures including (Münster Halvari 2012):

autonomy orientation (Dental Care Autonomy Orientation Scale) adapted in the present study from the Exercise Causality Orientations Scale (Rose 2001) and the General Causality Orientations Scale (Deci 1985);

perceived autonomy support (6‐item version of the Health Care Climate Questionnaire (Williams 1996));

autonomous motivation for the dental project (Evaluation of Dental Project Scale (Halvari 2006));

autonomous motivation for dental home care (a 3‐item identified subscale of the Self‐Regulation for Dental Home Care Questionnaire (Halvari 2012));

perceived dental competence (Dental Coping Beliefs Scale (Wolfe 1996)) using the five items with the best factor loadings (Halvari 2006) and two added items from a previous study (Halvari 2010);

dental health behaviour assessed by a 4‐item formative composite scale (Halvari 2010).

A further study (Tedesco 1992) reported on the theory of reasoned action variables assessed via Theory of Reasoned Action Oral Health Scale (Fishbein 1980).

Secondary outcome ‐ Economic factors

Only one study reported on economic net benefits of OHA (Ramsay 2018).

Other outcomes

No adverse events due to OHA were reported in the included trials.

Excluded studies

We excluded 84 studies from the review (see Characteristics of excluded studies). Below is a summary of the reasons for excluding these studies (some studies were excluded for more than one reason).

Thirty‐six studies did not take place in a dental setting.

Eleven studies were not a randomised controlled trial.

Nine studies the intervention was not delivered by a member of the dental team.

Eight studies had less than 8 weeks follow‐up.

Seven studies did not deliver the intervention on a one‐to‐one basis.

Eleven studies had an additional intervention included in the intervention group but not the control group (e.g. fluoride application, prophylaxis, provision of an electric toothbrush).

Three studies had no OHA provided or no OHA comparator.

One study tested a model of behaviour only.

One study compared manual versus powered toothbrushes.

One study was not related to oral health education.

In one study no pre‐treatment measures were completed.

Awaiting classification studies

The authors of two published trial protocols were contacted for further information but no reply was received (Gao 2013; IRCT2014062618248N1).

Ongoing studies

The author of one ongoing trial confirmed that data collection was completed but data analysis was not complete at the current time (ACTRN12605000607673).

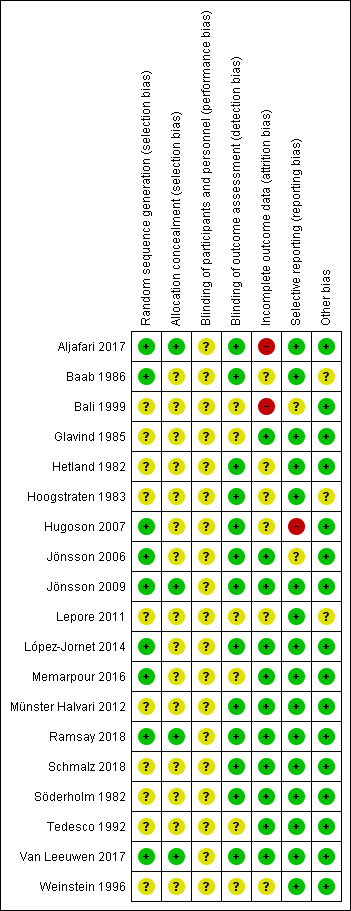

Risk of bias in included studies

We assessed risk of bias based on the information reported in the included studies in the first instance. We subsequently contacted authors for further information for missing information or clarification. Two authors replied and provided information for two studies (Aljafari 2017; Schmalz 2018).

Allocation

Random sequence generation

We assessed nine studies to be at low risk of bias for this domain (Aljafari 2017; Baab 1986; Hugoson 2007; Jönsson 2006; Jönsson 2009; López‐Jornet 2014; Memarpour 2016; Ramsay 2018; Van Leeuwen 2017). There were 10 studies that had insufficient information to make a judgement and we assessed them as at unclear risk of bias (Bali 1999; Glavind 1985; Hetland 1982; Hoogstraten 1983; Lepore 2011; Münster Halvari 2012; Schmalz 2018; Söderholm 1982; Tedesco 1992; Weinstein 1996).

Allocation concealment

We assessed four studies to be at low risk of bias for this domain (Aljafari 2017; Jönsson 2009; Ramsay 2018; Van Leeuwen 2017). None of the studies assessed were deemed to be at high risk of bias for this domain. There were 15 studies that had insufficient information to make a judgement and we assessed them as at unclear risk of bias (Baab 1986; Bali 1999; Glavind 1985; Hetland 1982; Hoogstraten 1983; Hugoson 2007; Jönsson 2006; Lepore 2011; López‐Jornet 2014; Memarpour 2016; Münster Halvari 2012; Schmalz 2018; Söderholm 1982; Tedesco 1992; Weinstein 1996).

Blinding

Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias)

We assessed all 19 studies to be at unclear risk of bias for this domain (Aljafari 2017; Baab 1986; Bali 1999; Glavind 1985; Hetland 1982; Hoogstraten 1983; Hugoson 2007; Jönsson 2006; Jönsson 2009; Lepore 2011; López‐Jornet 2014; Memarpour 2016; Münster Halvari 2012; Ramsay 2018; Schmalz 2018; Söderholm 1982; Tedesco 1992; Van Leeuwen 2017; Weinstein 1996). It is not possible to blind participants to this intervention and it is unclear the influence this would have on the risk of bias for this domain.

Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias)

We assessed 13 studies to be at low risk of bias for this domain (Aljafari 2017; Baab 1986; Hetland 1982; Hoogstraten 1983; Hugoson 2007; Jönsson 2006; Jönsson 2009; López‐Jornet 2014; Münster Halvari 2012; Ramsay 2018; Schmalz 2018; Söderholm 1982; Van Leeuwen 2017). There were six studies that had insufficient information to make a judgement and we assessed them as at unclear risk of bias (Bali 1999; Glavind 1985; Lepore 2011; Memarpour 2016; Tedesco 1992; Weinstein 1996).

Incomplete outcome data

We assessed 11 studies to be at low risk of bias for this domain (Glavind 1985; Jönsson 2006; Jönsson 2009; López‐Jornet 2014; Memarpour 2016; Münster Halvari 2012; Ramsay 2018; Schmalz 2018; Söderholm 1982; Tedesco 1992; Van Leeuwen 2017). We assessed two studies at high risk of bias for this domain (Aljafari 2017; Bali 1999). There were six studies that had insufficient information to make a judgement and we assessed them as at unclear risk of bias (Baab 1986; Hetland 1982; Hoogstraten 1983; Hugoson 2007; Lepore 2011; Weinstein 1996).

Selective reporting

We assessed 16 studies to be at low risk of bias for this domain (Aljafari 2017; Baab 1986; Glavind 1985; Hetland 1982; Hoogstraten 1983; Jönsson 2009; Lepore 2011; López‐Jornet 2014; Memarpour 2016; Münster Halvari 2012; Ramsay 2018; Schmalz 2018; Söderholm 1982; Tedesco 1992; Van Leeuwen 2017; Weinstein 1996). We assessed one study at high risk of bias for this domain (Hugoson 2007). There were two studies that had insufficient information to make a judgement and we assessed them as at unclear risk of bias (Bali 1999; Jönsson 2006).

Other potential sources of bias

We assessed 16 studies to be at low risk of bias for this domain (Aljafari 2017; Bali 1999; Glavind 1985; Hetland 1982; Hugoson 2007; Jönsson 2006; Jönsson 2009; López‐Jornet 2014; Memarpour 2016; Münster Halvari 2012; Ramsay 2018; Schmalz 2018; Söderholm 1982; Tedesco 1992; Van Leeuwen 2017; Weinstein 1996). There were three studies that had insufficient information to make a judgement and we assessed them as at unclear risk of bias (Baab 1986; Hoogstraten 1983; Lepore 2011).

Overall risk of bias

We assessed none of the studies as being at low risk of bias.

We assessed three studies as being at high risk of bias. These studies had at least one domain assessed as high risk of bias (Aljafari 2017; Bali 1999; Hugoson 2007).

We assessed 16 studies as being at unclear risk of bias. These studies had at least one domain judged to be at unclear risk of bias, but no domains judged to be at high risk of bias (Baab 1986; Glavind 1985; Hetland 1982; Hoogstraten 1983; Jönsson 2006; Jönsson 2009; Lepore 2011; López‐Jornet 2014; Memarpour 2016; Münster Halvari 2012; Ramsay 2018; Schmalz 2018; Söderholm 1982; Tedesco 1992; Van Leeuwen 2017; Weinstein 1996).

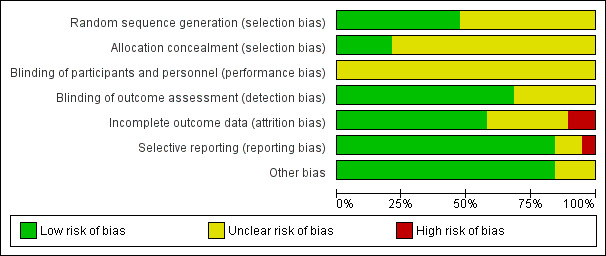

The results of the risk of bias assessments are presented graphically in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

3.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Summary of findings ‐ Any form of one‐to‐one oral hygiene advice (OHA) versus no OHA.

| Any form of 1‐to‐1 OHA versus no OHA in a dental setting for oral health | |||

|

Patient or population: children or adults Settings: dental surgery/office setting Intervention: any form of 1‐to‐1 OHA Comparison: no OHA | |||

| Outcomes | Number of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

| Periodontal health: gingivitis |

477 participants (2 studies); follow‐up: 235 participants | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1 | 1 small study in adults had contradictory results at 3 months and 6 months The other study in adults showed evidence of a benefit for OHA at all time points of 12 months, 24 months, and 36 months |

| Periodontal health: plaque levels |

477 participants (2 studies); follow‐up: 235 participants | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2 | Both studies at all time points consistently showed a benefit in plaque reduction for OHA |

| Dental caries | 377 participants (2 studies); follow‐ up: 244 participants | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low3 | 1 study in adults reported only "small and statistically insignificant changes" but no usable data reported The other study on infants provided very low‐quality evidence of a benefit for OHA at 8 months and 12 months, but not at 4 months |

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate | |||

11 study at high risk and 1 at unclear risk of bias. 1 study small with contradictory results. Inconsistency between studies, unable to pool data. The number of appointments and intensity of the interventions would not be applicable in routine dental practice. Downgraded for risk of bias, inconsistency and indirectness. 21 study at high risk and 1 at unclear risk of bias. The number of appointments and intensity of the interventions would not be applicable in routine dental practice. Downgraded for risk of bias and indirectness. 32 unclear risk of bias studies. Inconsistency between studies, unable to pool data. The number of appointments and intensity of the interventions would not be applicable in routine dental practice. Downgraded for risk of bias and inconsistency and indirectness.

Summary of findings 2. Summary of findings ‐ Personalised one‐to‐one OHA versus routine one‐to‐one OHA.

| Personalised 1‐to‐1 OHA versus routine 1‐to‐1 OHA in a dental setting for oral heath | |||

|

Patient or population: children or adults Settings: dental surgery/office setting Intervention: personalised 1‐to‐1 OHA in a dental setting Comparison: routine 1‐to‐1 OHA in a dental setting | |||

| Outcomes | Number of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

| Periodontal health: gingivitis |

2209 participants (4 studies); follow‐up: 1635 participants | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1 | 1 large study in adults showed little or no difference between groups at 36 months 1 study in adults showed evidence of a benefit for personalised OHA at 3 months and 12 months 1 study in children reported "statistically significant (P < 0.05) improvement" for personalised OHA but did not report usable data 1 study showed little or no difference between groups at 3 months |

| Periodontal health: plaque levels |

332 participants (3 studies); follow‐up: 308 participants | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2 | 1 study in adults showed evidence of a benefit for personalised OHA at 3 months and 12 months 1 study in children reported "statistically significant (P < 0.05) improvement" for personalised OHA but did not report usable data 1 study showed little or no difference between groups at 3 months |

| Dental caries | 69 participants (1 study); follow‐ up: 69 participants | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low3 | 1 study in children between the ages of 1 year and 6 years old reported "statistically significant (P < 0.05) improvement" for personalised OHA but did not report usable data |

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate | |||

14 unclear risk of bias studies. Inconsistency between studies, unable to pool data. Setting of 3 studies is secondary care, and intervention in 1 study (number of appointments and/or intensity required) is not applicable to routine dental practice. Downgraded for risk of bias, inconsistency and indirectness. 23 unclear risk of bias studies. Inconsistency between studies, unable to pool data. Setting of 3 studies is secondary care, and intervention in 1 study (number of appointments and/or intensity required) is not applicable to routine dental practice. Downgraded for risk of bias, inconsistency and indirectness. 31 unclear risk of bias study. No usable data. Setting not applicable to routine dental practice, so downgraded for indirectness.

Summary of findings 3. Summary of findings ‐ Self‐management versus professional OHA.

| Self‐management versus professional OHA in a dental setting for oral heath | |||

|

Patient or population: children or adults Settings: dental surgery/office setting Intervention: self‐management Comparison: professional OHA in a dental setting | |||

| Outcomes | Number of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

| Periodontal health: gingivitis |

185 participants (4 studies); follow‐up: 181 participants | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1 | 1 study in adults reported "significant differences between groups at each observation were not found" but no usable data reported 1 study in adults reported "no statistically significant differences in gingival bleeding scores were found between the 2 treatment groups at any of the 3 examinations" but no usable data reported 1 study in adults showed little or no difference between groups at 3 months 1 study in adults with hyposalivation provided weak evidence of a benefit in gingivitis for professional OHA at 2 months |

| Periodontal health: plaque levels |

185 participants (4 studies); follow‐up: 181 participants | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1 | 1 study in adults reported "mean plaque scores did not differ significantly between groups" but no usable data reported 1 study in adults reported "no statistically significant differences were found between the 2 groups at any of the examination times" but no usable data reported 1 study in adults provided weak evidence of a benefit in plaque reduction at 3 months for self‐management 1 study in adults with hyposalivation provided very weak evidence of a benefit in plaque reduction for professional OHA at 2 months |

| Dental caries | No studies were found that looked at dental caries | ||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate | |||

14 unclear risk of bias studies. Inconsistency between studies, unable to pool data. 3 studies were in secondary care and 3 of the interventions of 3 trials (number of appointments and/or intensity required) are not applicable to routine dental practice therefore we also downgraded for indirectness.

Summary of findings 4. Summary of findings ‐ Enhanced one‐to‐one OHA versus one‐to‐one OHA.

| Enhanced 1‐to‐1 OHA versus 1‐to‐1 OHA in a dental setting for oral heath | |||

|

Patient or population: children or adults Settings: dental surgery/office setting Intervention: enhanced 1‐to‐1 OHA in a dental setting Comparison: 1‐to‐1 OHA in a dental setting | |||

| Outcomes | Number of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

| Periodontal health: gingivitis |

782 participants (5 studies); follow‐up: 430 participants | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1 | 2 studies in adults did not report usable data 1 study in adults provided low‐quality evidence of a benefit in gingivitis reduction at 5.5 months for enhanced OHA 3 studies found little or no difference between groups across all time points |

| Periodontal health: plaque levels |

802 participants (6 studies); follow‐up: 440 participants | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2 | 2 studies in adults did not report usable data 1 study in adults provided low‐quality evidence of a benefit in plaque reduction at 5.5 months for enhanced OHA 1 study in adults found little or no difference between groups at 3 months 1 study in adults found little or no difference between groups across all time points 1 study in adults provided weak evidence of a benefit in plaque reduction for 1 of the enhanced OHA at 2 months |

| Dental caries | 121 participants (1 study); follow‐ up: 70 participants | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low3 | 1 study in adults did not report usable data |

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate | |||

11 study at high and 4 at unclear risk of bias. Unable to pool data. 2 of the included studies were in secondary care. Interventions of 4 trials (number of appointments and/or intensity) are not applicable in routine dental practice. Downgraded for risk of bias, inconsistency and indirectness. 21 study at high and 5 at unclear risk of bias. Unable to pool data. 2 of the included studies were in secondary care. Interventions of 5 trials (number of appointments and/or intensity) are not applicable in routine dental practice. Downgraded for risk of bias, inconsistency and indirectness. 31 high risk of bias study. Did not report usable data. Setting and intervention not applicable to routine dental care, therefore also downgraded for indirectness.

We have included 19 studies that investigated various forms and delivery methods of one‐to one oral hygiene advice (OHA) in a dental setting.

We have summarised data in additional tables, categorising trials to similar interventions groups where possible (Table 5; Table 6; Table 7; Table 8).

1. Comparison 1 ‐ Any form of one‐to‐one oral hygiene advice (OHA) versus no OHA.

| Hetland 1982 | |||||||||

|

Intervention: OHA provided by dental nurse Frequency: 3 intervention visits with OHA, each visit 1 week apart Intensity: 45 minutes first visit, 30 minutes at second visit, 15 minutes at third visit Control: no OHA (Adults; primary care setting) | |||||||||

| Endpoint | Gingivitis (GI) | Plaque (visible plaque after staining) | Caries (DMFT) | ||||||

| OHA | No OHA | OHA | No OHA | No summary statistics or effect estimates reported. Authors report "Only small and statistically insignificant changes occurred in the 3 groups during the experimental period" | |||||

| n Mean (SD) |

n Mean (SD) |

MD (95% CI) |

n Mean (SD) |

n Mean (SD) |

MD (95% CI) |

||||

| 3 months | n = 23 1.63 (0.23) |

n = 25 1.38 (0.41) |

0.25 (0.05 to 0.45) |

n = 23 0.21 (0.19) |

n = 25 0.62 (0.28) |

‐0.41 (‐0.54 to ‐0.28) | |||

| 6 months | 23 0.98 (0.39) |

25 1.36 (0.46) |

‐0.38 (‐0.62 to ‐0.14) |

n = 23 0.22 (0.19) |

n = 25 0.66 (0.24) |

‐0.44 (‐0.56 to ‐0.32) | |||

| Hoogstraten 1983 | |||||||||

|

Intervention: OHA provided by dental hygienist with or without film (combined groups). (For info, the 2 relevant arms of this study also appear in Comparison 4 enhanced OHA) Frequency: not fully reported Intensity: not fully reported Control: no OHA (Adults; primary care setting) | |||||||||

| Endpoint | Gingivitis | Plaque | Caries | ||||||

| 12 months | Outcome not measured | Outcome not measured | Outcome not measured | ||||||

| Hugoson 2007 | |||||||||

|

Intervention: preventive care instruction by hygienist Frequency: OHA provided 3 endpoints in 4 visits Intensity: approximately 125 minutes Control: no OHA (Adults; mixed public dental/primary care setting) | |||||||||

| Endpoint |

Gingivitis (Full mouth number of sites with gingivitis) |

Plaque (Plaque index score) |

Caries | ||||||

| OHA | No OHA | OHA | No OHA | Outcome not measured | |||||

| n Mean (SD) |

n Mean (SD) |

MD (95% CI) | n Mean (SD) |

n Mean (SD) |

MD (95% CI) | ||||

| 12 months | n = 98 22.2 (18.1) |

n = 97 30.2 (16.5) |

‐8.00 (‐12.86 to ‐3.14) |

n = 98 29.9 (25.2) |

n = 97 42.9 (23.9) |

‐13.00 (‐19.89 to ‐6.11) | |||

| 24 months | n = 97 19.0 (17.7) |

n = 96 26.7 (18.2) |

‐7.70 (‐12.77 to ‐2.63) |

n = 97 24.4 (23.1) |

n = 96 39.4 (24.1) |

‐15.00 (‐21.66 to ‐8.34) | |||

| 36 months | 93 19.4 (17.4) |

94 28.5 (17.0) |

‐9.10 (‐14.03 to ‐4.17) |

n = 93 24.5 (23.6) |

n = 94 37.6 (24.3) |

‐13.10 (‐19.97 to ‐6.23) | |||

| Memarpour 2016 | |||||||||

|

Intervention: OHA provided by dentist plus pamphlet Frequency: 2 'intervention' visits and 3 review visits Intensity: 30 minutes to 40 minutes Control: no OHA (Infants; primary care setting) | |||||||||

| Endpoint | Gingivitis | Plaque | Caries (proportion of infants developing caries) | ||||||

| Outcome not measured | Outcome not measured | OHA | No OHA | ||||||

| n events/n participants | n events/n participants | RR (95% CI) | |||||||

| 4 months | 2/97 | 3/96 |

0.66 (0.11 to 3.86) |

||||||

| 8 months | 3/94 | 15/94 |

0.20 (0.06 to 0.67) |

||||||

| 12 months | 4/85 | 29/88 |

0.14 (0.05 to 0.39) |

||||||

CI = confidence interval; DMFT = number of decayed, missing or filled permanent teeth; GI = gingival index (Löe 1963); MD = mean difference; n = number; OHA = oral hygiene advice; RR = risk ratio; SD = standard deviation.

2. Comparison 2 ‐ Personalised one‐to‐one OHA versus routine one‐to‐one OHA.

| Ramsay 2018 | |||||||||||

|

Intervention: personalised 1‐to‐1 OHA provided by the dentist or hygienist Frequency: reinforcement of OHA was provided at the discretion of the dentist/hygienist Intensity: not reported Control: routine 1‐to‐1 OHA provided by dentist or hygienist Frequency: reinforcement of OHA was provided at the discretion of the dentist/hygienist Intensity: not reported (Adults; primary care setting) | |||||||||||

| Endpoint | Gingivitis (GI) | Plaque | Caries | ||||||||

| Personalised | Routine | Outcome not measured | Outcome not measured | ||||||||

| n Mean (SD) |

n Mean (SD) |

MD (95% CI) |

|||||||||

| 36 months | 712 39.2 (23.8) |

615 38.7 (24.9) |

‐2.50 (‐8.30 to 3.30) | ||||||||

| Jönsson 2009 | |||||||||||

|