Abstract

Background

Initial goal‐directed resuscitation for hypotensive shock usually includes administration of intravenous fluids, followed by initiation of vasopressors. Despite obvious immediate effects of vasopressors on haemodynamics, their effect on patient‐relevant outcomes remains controversial. This review was published originally in 2004 and was updated in 2011 and again in 2016.

Objectives

Our objective was to compare the effect of one vasopressor regimen (vasopressor alone, or in combination) versus another vasopressor regimen on mortality in critically ill participants with shock. We further aimed to investigate effects on other patient‐relevant outcomes and to assess the influence of bias on the robustness of our effect estimates.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2015 Issue 6), MEDLINE, EMBASE, PASCAL BioMed, CINAHL, BIOSIS and PsycINFO (from inception to June 2015). We performed the original search in November 2003. We also asked experts in the field and searched meta‐registries to identify ongoing trials.

Selection criteria

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing various vasopressor regimens for hypotensive shock.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors abstracted data independently. They discussed disagreements between them and resolved differences by consulting with a third review author. We used a random‐effects model to combine quantitative data.

Main results

We identified 28 RCTs (3497 participants) with 1773 mortality outcomes. Six different vasopressors, given alone or in combination, were studied in 12 different comparisons.

All 28 studies reported mortality outcomes; 12 studies reported length of stay. Investigators reported other morbidity outcomes in a variable and heterogeneous way. No data were available on quality of life nor on anxiety and depression outcomes. We classified 11 studies as having low risk of bias for the primary outcome of mortality; only four studies fulfilled all trial quality criteria.

In summary, researchers reported no differences in total mortality in any comparisons of different vasopressors or combinations in any of the pre‐defined analyses (evidence quality ranging from high to very low). More arrhythmias were observed in participants treated with dopamine than in those treated with norepinephrine (high‐quality evidence). These findings were consistent among the few large studies and among studies with different levels of within‐study bias risk.

Authors' conclusions

We found no evidence of substantial differences in total mortality between several vasopressors. Dopamine increases the risk of arrhythmia compared with norepinephrine and might increase mortality. Otherwise, evidence of any other differences between any of the six vasopressors examined is insufficient. We identified low risk of bias and high‐quality evidence for the comparison of norepinephrine versus dopamine and moderate to very low‐quality evidence for all other comparisons, mainly because single comparisons occasionally were based on only a few participants. Increasing evidence indicates that the treatment goals most often employed are of limited clinical value. Our findings suggest that major changes in clinical practice are not needed, but that selection of vasopressors could be better individualised and could be based on clinical variables reflecting hypoperfusion.

Plain language summary

Vasopressors for hypotensive shock

Review question

This review seeks unbiased evidence about the effects of different drugs that enhance blood pressure on risk of dying in critically ill patients with impaired blood circulation.

Background

● Circulatory shock is broadly defined as a life‐threatening condition of impaired blood flow resulting in inability of the body to maintain blood delivery to body tissue and to meet oxygen demands.

● Typical signs of shock include low blood pressure, rapid heartbeat and poor organ perfusion indicated by low urine output, confusion or loss of consciousness.

● Death in the intensive care unit ranges from 16% to 60%, depending on the underlying condition: treatment includes fluid replacement followed by use of vasopressor agents, if necessary.

● A vasopressor agent is a drug that causes a rise in blood pressure. Six vasopressor drugs are available and are used successfully to increase blood pressure to reverse circulatory failure in critical care. Differences in their effects on survival are discussed with controversy and must be investigated.

● This review aims to discover whether any of the drugs given alone or in combination were better or worse than the others.

Search date

Evidence is current to June 2015.

Study characteristics

Review authors identified 28 randomized controlled trials involving 3497 critically ill patients with circulatory failure, among whom 1773 died. Patients were followed up to one year.

The following drugs, given alone or in combination, were studied in 12 different comparisons: dopamine, norepinephrine, epinephrine, phenylephrine, vasopressin, and terlipressin.

Key results

In summary, researchers found no significant differences in risk of dying in any comparisons of different drugs given alone or in combination when latest reported death was considered.

Disturbances in the rhythm of the heart were observed more frequently in people treated with dopamine than in those treated with norepinephrine.

Quality of the evidence

The quality of the evidence was high for the comparison of norepinephrine and dopamine, and was very low to moderate for the other comparisons.

Findings were consistent among the few large studies and studies of different quality.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Shock is a state of severe systemic deterioration in tissue perfusion, characterized by decreased cellular oxygen delivery and utilization, as well as decreased removal of waste byproducts of metabolism. Hypotension, although common in shock, is not synonymous with shock. Individuals can have hypotension and normal perfusion, whereas patients who have a history of hypertension can have shock without hypotension in the early phase of cardiogenic shock. Shock is the final pre‐terminal event in many diseases. Progressive tissue hypoxia results in loss of cellular membrane integrity, reversion to a catabolic state of anaerobic metabolism and loss of energy‐dependent ion pumps and chemical and electrical gradients. Mitochondrial energy production begins to fail. Multiple organ dysfunction follows localized cellular death, and this is followed by death of the organism (Young 2008). A widely used classification for mechanisms of shock consists of hypovolaemic, cardiogenic, obstructive and distributive (Hinshaw 1972). Septic shock, a form of distributive shock, is the most common form of shock among patients admitted to the intensive care unit, followed by cardiogenic and hypovolaemic shock; obstructive shock is rare. As an example, in a trial of 1600 patients with undifferentiated shock, septic shock occurred in 62%, cardiogenic shock in 16%, hypovolaemic shock in 16%, other types of distributive shock in 4% (e.g. neurogenic shock, anaphylaxis) and obstructive shock in 2% (De Backer 2010).

Currently, the definition of septic shock is more pragmatic because hypotension instead of hypoperfusion is the main clinical criterion. The current standard definition for septic shock (Dellinger 2008) in adults refers to a state of acute circulatory failure characterized by persistent arterial hypotension that is not explained by other causes. Hypotension is defined by systolic blood pressure < 90 mm Hg, mean arterial pressure < 60 mm Hg or a reduction in systolic blood pressure > 40 mm Hg despite adequate volume resuscitation in the absence of other causes for hypotension (Levy 2003). A large study defined shock even more pragmatically, as haemodynamic compromise necessitating administration of vasopressor catecholamines (Sakr 2006).

Estimates of the incidence of shock in the general population vary considerably. From an observational study, 31 cases of septic shock per 100,000 population/y (Esteban 2007) were reported. Many patients develop shock from severe sepsis, which has an incidence of 25 to 300 cases per 100,000 population/y (Angus 2001; Blanco 2008; Sundararajan 2005); among those, 30% are expected to develop septic shock (Esteban 2007).

The frequency of shock at healthcare facilities is somewhat better described. In the large observational study of sepsis occurrence in acutely Ill patients (SOAP), among 3147 critically ill participants from 198 intensive care units (ICUs), 34% had shock; of those, 15% had septic shock (Sakr 2006). Recently a large French observational study published similar numbers indicating that among 10,941 patients admitted to participating ICUs between October 2009 and September 2011, 1495 (13.7%) presented with inclusion criteria for septic shock (Quenot 2013). In another large European ICU cohort study, 32% were found to have septic shock. In a prospective observational study of 293,633 participants with ST‐elevation myocardial infarction from 775 US hospitals, 9% developed cardiogenic shock (Babaev 2005). From an observational study on 2445 participants admitted to a trauma level I centre, 22% were reported to already have shock on admission to the emergency department (ED) (Cannon 2009).

Hospital mortality is high, at around 38% (Sakr 2006), among patients with shock but seems to depend much on shock type. For patients with septic shock, mortality ranges from 46% (Esteban 2007; Sakr 2006) to 61% (Alberti 2005). Mortality in patients with traumatic shock was somewhat lower, at 16% (Cannon 2009). Whereas the incidence of cardiogenic shock was almost constant between 1995 and 2004, mortality has decreased from 60% in 1995 to 48% over the years (Babaev 2005).

Description of the intervention

Vasopressors are a heterogeneous class of drugs with powerful and immediate haemodynamic effects. Vasopressors can be classified according to their adrenergic and non‐adrenergic actions.

Catecholamines are sympathomimetics that act directly or indirectly on adrenergic receptors. Their haemodynamic effects depend on their varying pharmacological properties. They may increase the contractility of myocardial muscle fibres and heart rate (via beta‐adrenergic receptors), but they may also, and sometimes exclusively, increase vascular resistance (via alpha‐adrenergic receptors). Many good textbooks have outlined the detailed mechanisms of action (e.g. see Hoffman 1992; Zaritsky 1994).

The haemodynamic properties of vasopressin, a neurohypophysial peptide hormone, were first reported in 1926 (Geiling 1926). Vasopressin and analogues like terlipressin display their vasopressor effects via vasopressin receptors and serve as newer treatments for patients with shock (Levy 2010).

Utilisation of different vasopressors was described recently in a large European multi‐centre cohort study conducted in 198 ICUs (Sakr 2006). The most frequently used vasopressor was norepinephrine (80%), followed by dopamine (35%) and epinephrine (23%), given alone or in combination. Single‐agent use was reported for norepinephrine (32%), dopamine (9%) and epinephrine (5%). A combination of norepinephrine, dopamine and epinephrine was used in only 2% of patients with shock. Vasopressin and terlipressin were not described in this report. Currently the choice of vasopressors seems to be based mainly on physicians' preferences (Leone 2004). Additionally, clinical guidelines suggest norepinephrine as the first‐line vasopressor in shock states, such as septic shock (Dellinger 2013).

How the intervention might work

Initial goal‐directed resuscitation to support vital functions is essential in the management of shock. First‐line treatment for the manifestation of circulatory failure usually consists of administration of intravenous fluids. If fluid treatment does not restore circulatory function, vasopressors such as norepinephrine, dopamine, epinephrine and vasopressin are recommended.

Why it is important to do this review

Effects of vasopressors on the cardiovascular system are largely undisputed. However, it remains unclear whether a vasopressor of choice is known for the treatment of patients with particular forms of shock or for the treatment of patients with shock in general. We are conducting this systematic review to explore uncertainty arising from conflicting results reported by several studies in this area.

Objectives

Our objective was to compare the effect of one vasopressor regimen (vasopressor alone, or in combination) versus another vasopressor regimen on mortality in critically ill participants with shock. We further aimed to investigate effects on other patient‐relevant outcomes and to assess the influence of bias on the robustness of our effect estimates.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) undertaken to investigate the effects of vasopressors in the treatment of patients with any kind of circulatory failure. For simplicity, we refer to circulatory failure as 'shock' (see also search terms for shock). We were exclusively interested in patient‐relevant outcomes (see below). Such endpoints, particularly death, can be assessed only through parallel‐group trials. Therefore, we excluded cross‐over trials.

Types of participants

We included trials with acutely and critically ill adult and paediatric participants. We excluded trials looking at pre‐term infants with hypotension, as this patient group is covered in another Cochrane review (Subhedar 2003). We excluded animal experiments. The definition of 'hypotensive shock' used was that given by study authors.

Types of interventions

The intervention consisted of administration of different vasopressors, vasopressors versus intravenous fluids and vasopressors versus placebo with or without non‐protocol vasoactive drugs (NPVDs).

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

We looked at total mortality (in the ICU, in hospital and at one year) as the main endpoint. If mortality was assessed at several time points in a study, we used data derived from the latest follow‐up time.

Secondary outcomes

Other pre‐defined outcomes included the following.

-

Morbidity, given as:

ICU length of stay (LOS);

hospital LOS;

duration of vasopressor treatment;

duration of mechanical ventilation;

renal failure (as defined by study authors, such as oliguria or need for renal replacement therapy); and

other.

Measures of health‐related quality of life at any given time, and measures of anxiety and depression (together or separately) at any given time.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following databases: the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2015, Issue 6) (see Appendix 1, Search filter for CENTRAL); MEDLINE (1966 to June 2015) (see Appendix 2); EMBASE (1989 to June 2015) (see Appendix 3, Search filter for EMBASE); PASCAL BioMed (1996 to June 2015); and BIOSIS (1990 to June 2015) (see Appendix 4 and Appendix 5, Search filter for PASCAL BioMed, CINAHL and BIOSIS); PsycINFO (1978 to June 2015) (see Appendix 6, Search filter for PsycINFO) using the Ovid platform. We searched CINAHL (1984 to June 2015) via EBCSO.

We searched for key words describing the condition or describing the intervention and combined the results by using a methodological filter (RCT filter).

We used a validated RCT filter for MEDLINE and EMBASE (Higgins 2011).

We applied no language restrictions.

Searching other resources

We searched ongoing clinical trials and unpublished studies via the Internet (date of latest search, 24 June 2015) on www.controlled‐trials.com by using the multiple database search option metaRegister of Controlled Trials. This register includes International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN) Register, Action Medical Research, Leukaemia Research Fund, Medical Research Council (UK), NHS Research and Development HTA Programme, ClinicalTrials.gov, Wellcome Trust and UK Clinical Trials Gateway.

Further, we searched textbooks and references of papers selected during the electronic search to look for relevant references. Finally, we contacted experts in the field to identify additional trials (see Acknowledgements).

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

We entered all search results into bibliographic software (Endnote X7, The Thomson Corp, USA); we then removed duplicates. At least two review authors (GG, CH, JA, HL, HH) independently screened the studies by title and abstract for exclusion using a template that included inclusion and exclusion criteria. We recorded reasons for exclusion. For the remaining studies, we retrieved full papers. Two review authors independently recorded the inclusion and exclusion criteria in the first section of the data extraction form. We resolved all disagreements through arbitration by a third review author (GG, CH, JA, HL, HH).

Data extraction and management

At least two review authors (GG, CH, JA, HL, HH) abstracted data independently onto a pre‐defined data extraction form and entered the data into RevMan 5.3. We compared results and resolved disagreements by discussion amongst at least three review authors (GG, CH, JA, HL, HH).

Besides data on intervention and outcome, we recorded study and participant characteristics such as age; gender; severity of illness, as given (e.g. acute physiology and chronic health evaluation (APACHE), multiple organ failure (MOF) score, simplified acute physiology score (SAPS)); underlying diagnosis and particular type of shock, given definition of shock; duration of ICU stay before enrolment into study; duration of mechanical ventilation before enrolment; and study setting.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently abstracted data onto a pre‐defined data extraction form. We abstracted whether adequate methods were used to generate a random sequence, whether allocation to treatment was concealed, whether inclusion and exclusion criteria were explicit, if data had been analysed by intention‐to‐treat, whether participant descriptions were adequate, whether care provided during the study period was identical in both groups, whether the outcome description was adequate, whether involved clinical staff were blinded to the intervention and whether the assessor of the outcome was blinded to the intervention. Noteworthy, for some interventions, is that performance bias is inevitable. We compared results and resolved disagreements by discussion amongst at least three review authors. We then entered data into RevMan. We produced a risk of bias graph and a risk of bias table.

Measures of treatment effect

For binary outcomes, we used risk ratio as the standard effect measure. For continuous outcomes, we used the difference in means as the standard effect measure.

Unit of analysis issues

We did not include cluster‐randomized or cross‐over trials in any of the analyses; in the case of multiple treatment groups, we refrained from combining groups to create a single pair‐wise summary comparison; and we declared studies as multi‐arm comparisons to allow for adequate network meta‐analyses.

Dealing with missing data

We did not replace missing data by using any algorithm, but we contacted study authors if we considered missing data essential.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed clinical and methodological heterogeneity by performing an informal inspection of study characteristics and clinical judgement. We measured statistical heterogeneity with the I2 statistic and heterogeneity with Cochrane Q tests. We did not use a specific threshold of I2 to judge heterogeneity, but as a general rule, we considered an I2 statistic greater than 50% as showing substantial heterogeneity (Higgins 2011).

Assessment of reporting biases

We planned to assess reporting bias and small‐study effects graphically by using funnel plots of standard errors versus effect estimates for the primary outcome. We also planned to formally test funnel plot asymmetry by using the arcsine test (Rücker 2008) if 10 or more studies per comparison were available for the primary outcome.

Data synthesis

We combined data quantitatively only if clinical heterogeneity was assumed to be negligible. For standard meta‐analyses, we used RevMan 5.3. We used a random‐effects model to combine risk ratios by default because we expected several different comparisons to show at least some heterogeneity. In two trials (Dünser 2003; Martin 1993), some participants crossed over to the other treatment; these participants were analysed according to the intention‐to‐treat principle, that is, according to the group to which they were initially assigned.

In this update, we decided to add a network meta‐analysis to demonstrate direct and indirect effects simultaneously (Salanti 2014). For the analysis, we used the R package netmeta version 0.7 (R Core Team 2014). Network meta‐analysis is a generalization of pair‐wise meta‐analysis, whereby all pairs of treatments are compared on the basis of the graph‐theoretical method originally developed in electrical network theory. This method is considered equivalent to the frequentist approach to network meta‐analysis (Rücker 2012). For network meta‐analyses, we estimated both fixed‐effect and random‐effects models.

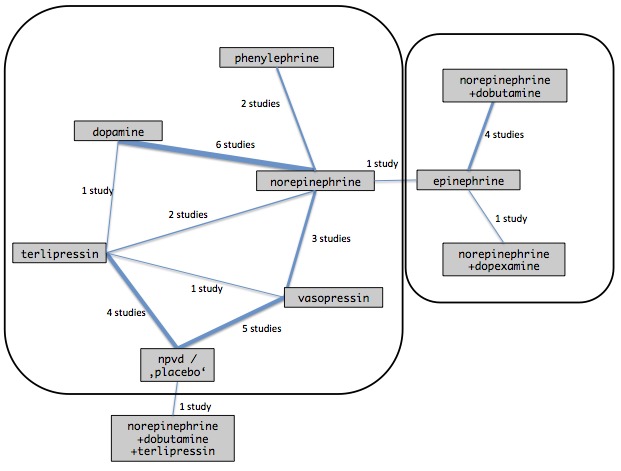

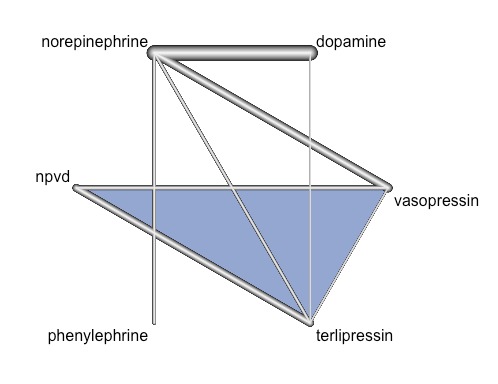

Conceptually, we identified two networks: one comparing different vasopressors or combinations of vasopressors (Figure 1, left‐hand side), and the other comparing vasopressors in combination with otherwise vasoactive catecholamines (Figure 1, right‐hand side). In both networks, the reference group was norepinephrine. We produced network plots indicating available direct comparisons, calculated effects relative to a baseline intervention and present network forest plots.

1.

Comparisons including vasopressors identified from the systematic review. The 10 interventions with 31 direct comparisons were derived from 28 studies. Line thickness is proportional to the number of included participants. Boxes indicate the two networks that we formally assessed in our network meta‐analysis. npvd/'placebo' denotes non‐protocol vasoactive drugs or placebo.

We calculated metrics for consistency/homogeneity. Using Rücker's frequentist approach, we derived this content from decomposition of the Q statistic and from the net heat plot (Krahn 2013). We also present analyses on the strength of evidence obtained from matrices derived by the netmeasures function in R (König 2012).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned no a priori subgroup analyses. We performed a post hoc subgroup analysis of participants with septic shock. We included studies performed in participants with septic shock and studies for which estimates were available for subgroups with septic shock. For this subgroup, we performed a network meta‐analysis comparing different vasopressors or combinations of vasopressors. We used norepinephrine as the reference group because it is currently considered the vasopressor of first choice (Dellinger 2013). We did not perform a subgroup analysis for the network including otherwise vasoactive catecholamines because of the limited number of available studies.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to perform a sensitivity analysis to assess the influence of risk of bias on the main effects of interventions, and thereby on the robustness of our estimates. We classified studies as 'low risk of bias' and 'no low risk of bias'. We classified studies as having low risk of bias if they had adequate allocation concealment, and if the other bias items in the summary were not believed to have a major influence on the robustness of the single study effect. Unclear or inadequate allocation concealment in any case resulted in classification as a 'study with no low risk of bias'. Our primary outcome was mortality, which was generally considered robust against outcome assessor knowledge of treatment allocation. Lack of blinding of outcome assessors therefore had less influence on assessment of risk of bias for this outcome. On the contrary, this risk of bias item had a strong effect on outcomes for which assessment included individual judgement, as for measures of quality of life. In the sensitivity analysis, we grouped studies according to our classification of 'low risk of bias' and 'no low risk of bias' in a forest plot.

We also performed a post hoc sensitivity analysis to investigate the influence of different time points on mortality outcome assessment.

'Summary of findings'

We used the principles of the GRADE (Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) approach (Guyatt 2008) to grade the quality of the body of evidence assessed in our review and constructed a 'Summary of findings' (SOF) table using GRADE software. The GRADE approach appraises the quality of a body of evidence according to the extent to which one can be confident that an estimate of effect or association reflects the item being assessed. The quality of a body of evidence considers within‐study risk of bias (methodological quality), directness of the evidence, heterogeneity of the data, precision of effect estimates and risk of publication bias.

We constructed ‘Summary of findings’ tables that included information about (1) populations (including specification of medium‐risk populations), interventions and comparisons for the standard meta‐analysis of norepinephrine versus dopamine on mortality and for results of the network meta‐analysis on mortality; (2) the source of external information used in the ‘Assumed risk’ column; (3) the GRADE approach to assess the quality of the body of evidence as briefly described above; and (4) any departures from standard methods. We included information on the primary outcome (total mortality) and on arrhythmia within 28 days.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

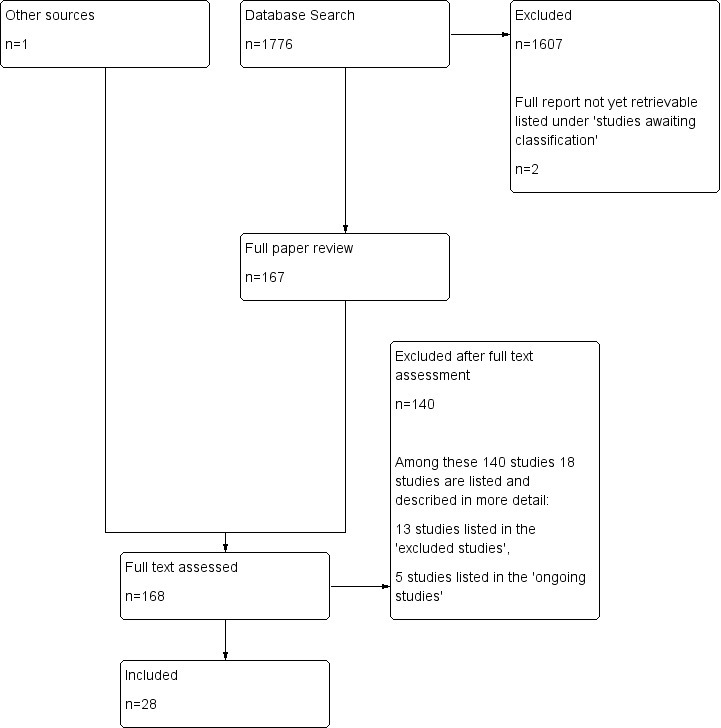

Search result

The electronic search resulted in 1776 hits after removal of duplicates with bibliographic software and one reference from other sources (Figure 2). We identified and retrieved 168 potentially relevant articles (this number included 12 articles identified by reading the references of potentially relevant articles and writing to 14 specialists in the field, five of whom replied; see Acknowledgements). Two trials were not retrievable (Hai Bo 2002; Singh 1966; see Characteristics of studies awaiting classification). Of these 168 articles, 140 did not meet our inclusion criteria after closer inspection for the following reasons.

2.

Search flow diagram.

54 trials involved other interventions.

49 were not randomized.

24 were cross‐over trials.

Three were animal studies.

Two trials were duplicates (abstract was presented at a scientific meeting and the report was subsequently published (Martin 1993)).

-

Four other publications (Russell 2008) did not meet criteria.

Two were systematic reviews.

Two eligible RCTs provided none of the pre‐defined outcomes (Morelli 2011; Morelli 2011a).

Of these 140 excluded reports, we identified 13 potentially relevant studies (see Characteristics of excluded studies). Finally, we included 28 studies in our review (Characteristics of included studies).

Included studies

In our original review (Müllner 2004), we included eight studies. In the updated review (Havel 2011), we included 15 new studies. This current update adds five new studies. In total, we have included 28 studies investigating several comparisons among 3497 participants (Figure 1). Six different vasopressors, alone or in combination, were studied in 12 different comparisons. Details are presented in the table Characteristics of included studies. Among these studies, eight were multi‐centre studies (Annane 2007; Choong 2009; De Backer 2010; Han 2012; Lauzier 2006; Malay 1999; Myburgh 2008; Russell 2008) and all but five (Annane 2007; Han 2012; Malay 1999; Myburgh 2008; Svoboda 2012) were performed at university hospitals only.

Eighteen studies were performed in participants with septic shock (Albanese 2005; Annane 2007; Han 2012; Jain 2010; Lauzier 2006; Malay 1999; Marik 1994; Martin 1993; Morelli 2008a; Morelli 2008b; Morelli 2009; Patel 2010; Ruokonen 1993; Russell 2008; Seguin 2002; Seguin 2006; Yildizdas 2008; Svoboda 2012). Three studies included participants with peri‐operative shock (Boccara 2003; Dünser 2003; Luckner 2006). Two studies were performed in paediatric participants (Choong 2009; Yildizdas 2008).

Seventeen studies provided norepinephrine as an intervention (Albanese 2005; Boccara 2003; De Backer 2010; Dünser 2003; Han 2012; Jain 2010; Lauzier 2006; Luckner 2006; Marik 1994; Martin 1993; Mathur 2007; Morelli 2008a; Morelli 2008b; Myburgh 2008; Patel 2010; Ruokonen 1993; Russell 2008); another four studies examined the combination of norepinephrine + dobutamine (Annane 2007; Levy 1997; Levy 2011; Seguin 2002); and one study used the combination of norepinephrine + dopexamine (Seguin 2006).

Nine studies used dopamine (De Backer 2010; Han 2012; Hua 2013; Jain 2010; Marik 1994; Martin 1993; Mathur 2007; Patel 2010; Ruokonen 1993), and six studies used epinephrine (Annane 2007; Levy 1997; Levy 2011; Myburgh 2008; Seguin 2002; Seguin 2006). Eight studies used vasopressin (Choong 2009; Dünser 2003; Han 2012; Lauzier 2006; Luckner 2006; Malay 1999; Morelli 2009; Russell 2008), and another seven studies used terlipressin (Albanese 2005; Boccara 2003; Hua 2013; Morelli 2008a; Morelli 2009; Svoboda 2012; Yildizdas 2008). Two studies used phenylephrine (Jain 2010; Morelli 2008b), and five studies compared vasopressors versus placebo or non‐protocolized vasopressors as add‐on therapy (Choong 2009; Malay 1999; Morelli 2008a; Svoboda 2012; Yildizdas 2008).

Excluded studies

In total, we excluded 140 studies after full‐text assessment, among which 13 studies are listed by reference. We have presented some details of the 13 excluded studies in the table Characteristics of excluded studies. We excluded 10 studies because they reported not on any of our pre‐defined endpoints but on haemodynamic variables and other surrogate endpoints instead (Argenziano 1997; Hentschel 1995; Kinstner 2002; Levy 1999; Majerus 1984; Morelli 2011; Morelli 2011a; Patel 2002; Totaro 1997; Zhou 2002). We excluded one trial in which investigators looked at pre‐term infants with hypotension (Rozé 1993), as this topic is covered in another Cochrane review (Subhedar 2003). One study was a non‐randomized multi‐centre prospective cohort study and therefore was excluded (Sperry 2008). Another study compared low‐dose dopamine versus dopexamine and versus placebo added to norepinephrine with the intention of improving renal and splanchnic blood flow. Low‐dose dopamine at 3 µg/kg/min is not considered to have relevant vasopressor properties; therefore we also excluded this study (Schmoelz 2006).

Studies waiting to be assessed

We have not yet been able to retrieve two particular studies. One, which was published in 1966 (Singh 1966), is a 'comparative study of angiotensin and norepinephrine in hypotensive states', according to the title. As no abstract is available, we do not know how many participants were enrolled. The second study, published in the journal Critical Care Shock in 2002 (Hai Bo 2002), also could not be retrieved. This paper is on the 'renal effect of dopamine, norepinephrine, epinephrine, or norepinephrine‐dobutamine in septic shock'. We do not know whether this study contained original data from human experiments, whether it was randomized and, if so, whether researchers reported relevant outcomes.

Ongoing studies

Our search resulted in 52 potentially relevant ongoing studies. We considered five ongoing studies (Choudhary 2013; Cohn 2007a; Fernandez 2006; Gordon 2014; Lienhart 2007) as relevant (Characteristics of ongoing studies).

Risk of bias in included studies

Methodological quality of included studies

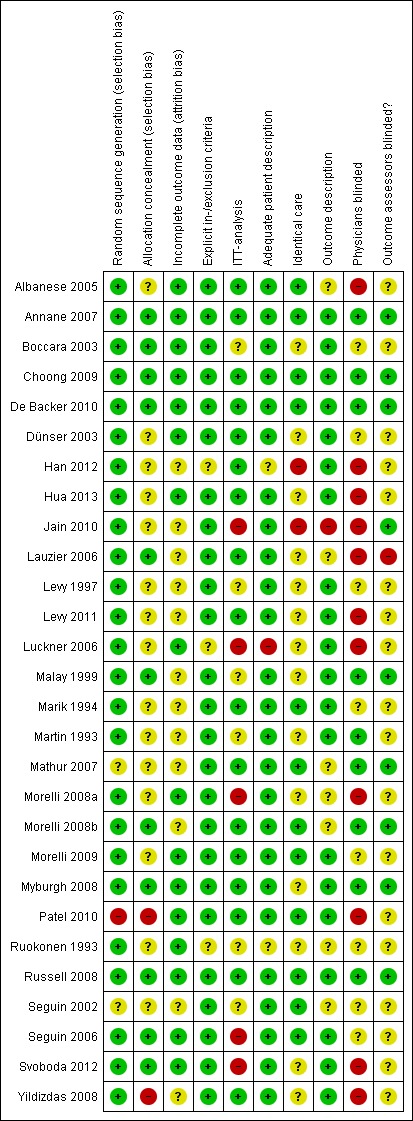

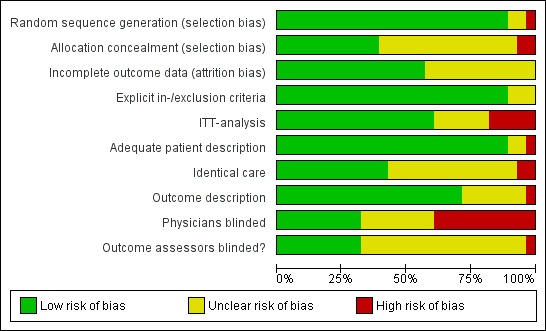

We have presented risk of bias in Figure 3 and Figure 4.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

4.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

GRADE evidence quality varied considerably between comparisons and ranged from high to very low.

Generally, risk of bias in the included studies was moderate. For the comparison of norepinephrine versus dopamine, risk of bias was low, but for the other comparisons, risk of bias was moderate to high. We classified 11 studies as having low risk of bias for the primary outcome of mortality (Annane 2007; Boccara 2003; Choong 2009; De Backer 2010; Lauzier 2006; Malay 1999; Morelli 2008b; Myburgh 2008; Russell 2008; Seguin 2006; Svoboda 2012); only four studies fulfilled all trial quality items (Annane 2007; Choong 2009; De Backer 2010; Russell 2008).

Allocation

Random sequence generation was reported in all but four studies (Levy 2011; Mathur 2007; Patel 2010; Seguin 2002). Allocation concealment was appropriate in 11 studies (Annane 2007; Boccara 2003; Choong 2009; De Backer 2010; Lauzier 2006; Malay 1999; Morelli 2008b; Myburgh 2008; Russell 2008; Seguin 2006; Svoboda 2012) and was not appropriate in three studies (Han 2012; Patel 2010; Yildizdas 2008).

All but eight studies presented intention‐to‐treat analyses; for six studies this item was unclear (Boccara 2003; Levy 1997; Malay 1999; Martin 1993; Ruokonen 1993; Seguin 2002), and for four studies this was not fulfilled (Jain 2010; Luckner 2006; Morelli 2008a; Svoboda 2012).

Blinding

From the available information, identical care for the intervention group and the control group could be assumed for 12 studies (Albanese 2005; Annane 2007; Choong 2009; De Backer 2010; Marik 1994; Mathur 2007; Morelli 2008b; Morelli 2009; Patel 2010; Russell 2008; Seguin 2002; Seguin 2006). An appropriate outcome description was present in 20 studies; for the remaining eight studies, this was unclear (Albanese 2005; Jain 2010; Lauzier 2006; Mathur 2007; Morelli 2008a; Morelli 2008b; Ruokonen 1993; Seguin 2002). Treating personnel were blinded in nine studies (Annane 2007; Choong 2009; De Backer 2010; Malay 1999; Martin 1993; Mathur 2007; Morelli 2008b; Myburgh 2008; Russell 2008). In the same nine studies, outcome assessors were blinded too. In one study, only outcome assessors were blinded (Jain 2010).

Incomplete outcome data

Generally, studies included critically ill participants, for whom follow‐up usually is not of major concern.

Selective reporting

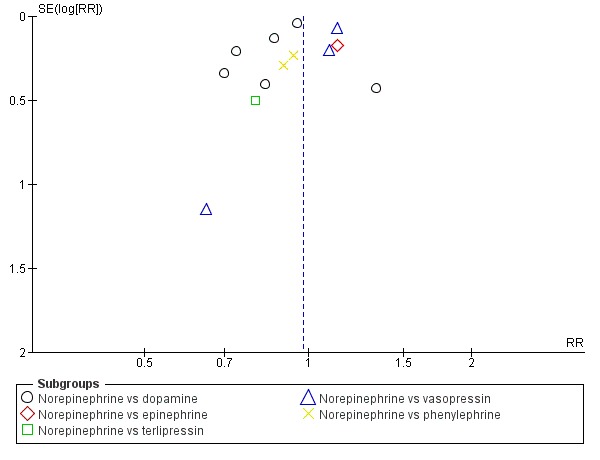

Given the large number of comparisons, each with a few studies only, proper assessment of between‐study reporting bias was not possible. However, when looking at the funnel plot in Figure 5, we could not spot major asymmetry. Within‐study reporting bias: Many of the included studies were performed several years ago, when it was not standard to publish trial protocols. Accordingly, we could not systematically assess selective outcome data reporting because protocols were not available. However, for the primary outcome of 'mortality', we assumed that selective omission of this outcome was unlikely in the ICU setting because this is one of the standard clinical outcomes. Choice of outcome usually is determined by the design (short‐term haemodynamic studies vs longer‐term studies with clinical outcomes).

5.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 norepinephrine, outcome: 1.1 mortality.

Other potential sources of bias

All but two studies explicitly described inclusion and exclusion criteria (Boccara 2003; Ruokonen 1993). Participants were adequately described in all but three studies (Han 2012; Luckner 2006; Ruokonen 1993).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4; Table 5

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Dopamine compared with norepinephrine for hypotensive shock.

| Dopamine compared with norepinephrine for hypotensive shock | ||||||

| Patient or population: hypotensive shock Settings: critical care units Intervention: dopamine Comparison: norepinephrine | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Norepinephrine | Dopamine | |||||

| Total mortalitya | Moderateb | RR 1.07 (0.99 to 1.16)c | 1400 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGHd,e | ||

| 380 per 1000 | 407 per 1000 (376 to 441) | |||||

| Arrhythmia < BR/> follow‐up: range 28 days | Moderatef,g | RR 2.33 (1.45 to 3.85) | 1931 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGHh | ||

| 76 per 1000 | 177 per 1000 (110 to 293) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aThe largest study reported 12‐month mortality, one study reported 28‐day mortality and one hospital mortality. For the remaining 3 studies, the time point of mortality assessment was undetermined. A sensitivity analysis indicates no influence on effects by differences in mortality definition bSakr 2006

cEstimate from the network meta‐analysis integrating direct and indirect comparisons dFour smaller studies included up to 50 participants, each of whom did not fulfil some of the quality criteria and one high risk of bias study that contributed 252 participants. However, the summary result is mainly made up by the largest study of more than 1000 participants that fulfils all low risk of bias criteria eThe main outcomes of the four smaller studies are haemodynamics and metabolic measures. Mortality is reported only at the end of the results and often is unclear timepoint‐wise. However, the study by De Backer 2010 (which contributes mainly to the summary result) clearly defines mortality endpoints fReinelt 2001 gAnnane 2008 hInformation was obtained from 992 participants, 86% of whom were studied in a low risk of bias study (De Backer 2010); remaining participants were included in a high risk of bias study (Patel 2010). Effects show into the same direction

Summary of findings 2. Terlipressin compared with norepinephrine for hypotensive shock.

| Terlipressin compared with norepinephrine for hypotensive shock | ||||||

| Patient or population: hypotensive shock Settings: critical care units Intervention: terlipressin Comparison: norepinephrine | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Norepinephrine | Terlipressin | |||||

| Total mortalitya | Moderateb | RR 0.93 (0.69 to 1.26)c | 231 (7 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOWd | ||

| 380 per 1000 | 353 per 1000 (262 to 479) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI) CI: Confidence interval | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate | ||||||

aDirect comparisons based on in‐hospital mortality and mortality at an undetermined point in time. A sensitivity analysis indicates no influence on effects by differences in mortality definition. bSakr 2006

cEstimate from the network meta‐analysis integrating direct and indirect comparisons

dRisk of bias was serious with adequate allocation concealment in one small study that contributed to the estimates only; imprecision of the estimates was very serious, as direct comparisons are based on two small studies only, whereas only one contributed to the estimates

Summary of findings 3. Vasopressin compared with norepinephrine for hypotensive shock.

| Vasopressin compared with norepinephrine for hypotensive shock | ||||||

| Patient or population: hypotensive shock Settings: critical care units Intervention: vasopressin Comparison: norepinephrine | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Norepinephrine | Vasopressin | |||||

| Total mortalitya | Moderateb | RR 0.90 (0.78 to 1.03)c | 1108 (8 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATEd | ||

| 380 per 1000 | 342 per 1000 (296 to 391) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI) CI: Confidence interval | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate | ||||||

aFor the direct comparison, the largest study reported 90‐day mortality, and 2 studies contributed ICU mortality. A sensitivity analysis indicates no influence on effects by differences in mortality definition bSakr 2006

cEstimate from the network meta‐analysis integrating direct and indirect comparisons

dThe effect is based mainly on 1 moderately large RCT, and direct evidence comes from 3 RCTS including 812 individuals overall

Summary of findings 4. Phenylephrine compared with norepinephrine for hypotensive shock.

| Phenylephrine compared with norepinephrine for hypotensive shock | ||||||

| Patient or population: hypotensive shock Settings: critical care units Intervention: phenylephrine Comparison: norepinephrine | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Norepinephrine | Phenylephrine | |||||

| Total mortalitya | Moderateb | RR 1.08 (0.76 to 1.55)c | 86 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOWd,e | ||

| 380 per 1000 | 410 per 1000 (289 to 589) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI) CI: Confidence interval | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate | ||||||

aFor the direct comparison, one study measured ICU mortality; for the other study, the time point of mortality assessment was undetermined bSakr 2006

cEstimate from the network meta‐analysis integrating direct and indirect comparisons

dTwo small studies, with 1 having unclear allocation concealment and an open intervention

eTwo small studies with 86 individuals overall for the direct comparison

Summary of findings 5. Epinephrine compared with norepinephrine for hypotensive shock.

| Epinephrine compared with norepinephrine for hypotensive shock | ||||||

| Patient or population: hypotensive shock Settings: critical care units Intervention: epinephrine Comparison: norepinephrine | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Norepinephrine | Epinephrine | |||||

| Total mortalitya | Moderateb | RR 0.88 (0.63 to 1.25) | 269 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWc | ||

| 380 per 1000 | 334 per 1000 (239 to 475) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI) CI: Confidence interval | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate | ||||||

a90‐Day mortality bSakr 2006

cEffect from only 1 moderately large single RCT

In total, six vasopressors were compared in several combinations and directions (Figure 2). Therefore, we have organized our comparisons to present each vasopressor against all comparators in a separate analysis per outcome. Vasopressors that were used in both study arms were considered as constant between groups and generally were not explicitly described in analyses. For studies with more than two study arms, we used each comparison separately. We refrained from including overall summary effects within analyses to address considerable clinical heterogeneity due to major differences in comparators and,when applicable, to avoid a unit of analysis error.

Main analyses

Primary outcomes

Total mortality

Total mortality was assessed in all included studies. If mortality was assessed at several time points in a study we used data from the latest follow‐up time. Mortality was assessed at an undetermined time point in seven studies (Boccara 2003,; Jain 2010; Levy 1997,; Marik 1994,; Mathur 2007,; Seguin 2002,; Ruokonen 1993).

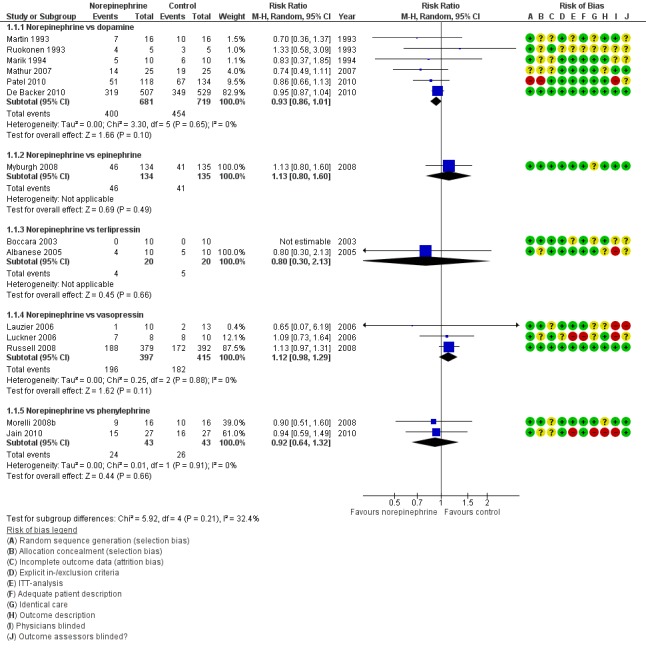

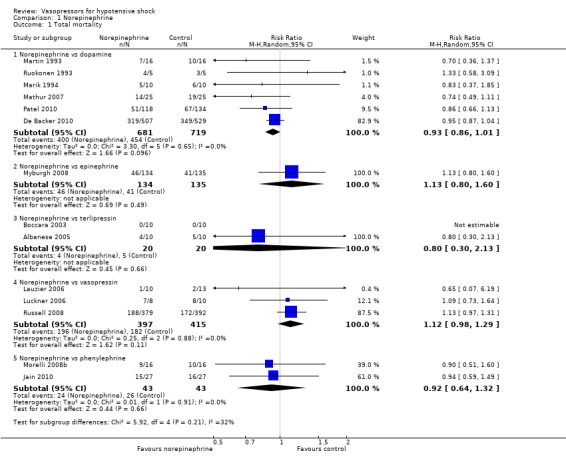

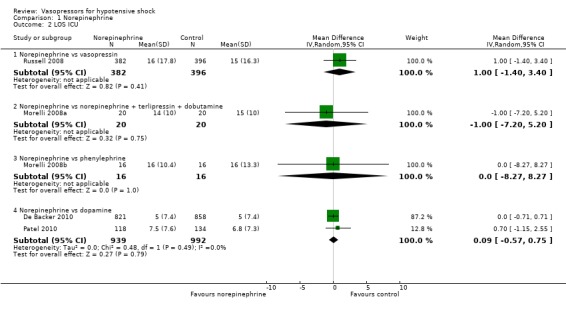

Norepinephrine was compared with dopamine, epinephrine, terlipressin, vasopressin, phenylephrine and norepinephrine + terlipressin + dobutamine (14 studies; 2607 participants) (Figure 6). In addition, Morelli 2009 compared norepinephrine versus norepinephrine + vasopressin and norepinephrine versus norepinephrine + terlipressin and found no differences in both comparisons (risk ratio (RR) 1.25, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.69 to 2.26; and RR 1.43, 95% CI 0.75 to 2.70 ‐ data from the single study not presented in analyses). Studies were performed in participants with septic shock (Albanese 2005; Jain 2010; Lauzier 2006; Levy 1997; Marik 1994; Martin 1993; Mathur 2007; Morelli 2008a; Morelli 2008b; Morelli 2009; Patel 2010; Ruokonen 1993; Russell 2008; Seguin 2002; Seguin 2006), in critically ill participants (De Backer 2010; Myburgh 2008), in participants with refractory hypotension after anaesthesia (Boccara 2003) and in adult post‐operative participants (Luckner 2006). None of the comparisons revealed significant differences. Morelli 2008a compared NPVD (including norepinephrine) versus norepinephrine + terlipressin + dobutamine and found no differences in mortality (14/20 vs 14/20; RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.67 to 1.50). The funnel plot, which is presented in Figure 5 shows no indication of relevant asymmetry.

6.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Norepinephrine, outcome: 1.1 Total mortality.

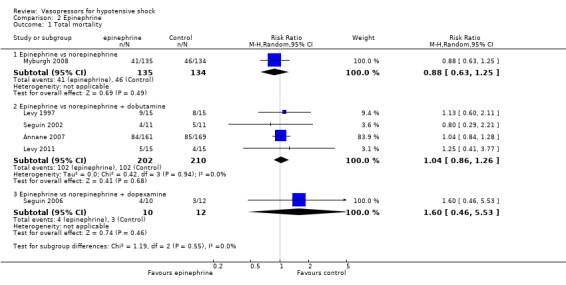

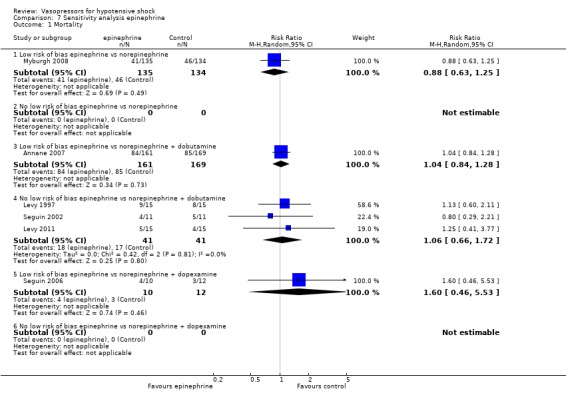

Epinephrine was compared with norepinephrine, norepinephrine + dobutamine and norepinephrine + dopexamine (six studies; 703 participants) (Analysis 2.1). Overall 298 deaths were observed among the 703 participants. Studies were performed in participants with septic shock (Annane 2007; Levy 1997; Seguin 2002; Seguin 2006), participants with cardiogenic shock (Levy 2011) and critically ill participants (Myburgh 2008). In no comparisons was a significant difference found.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Epinephrine, Outcome 1 Total mortality.

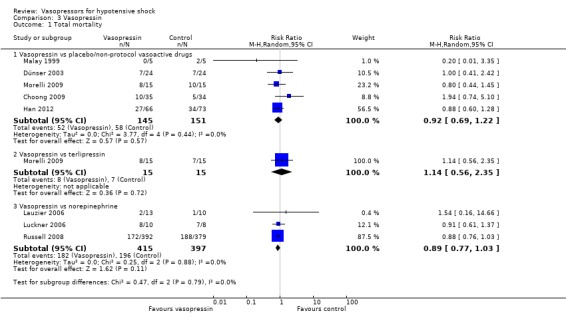

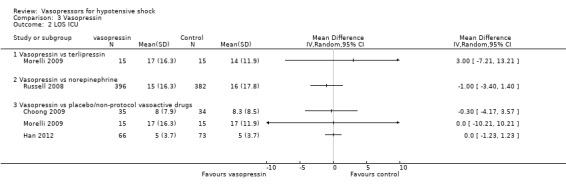

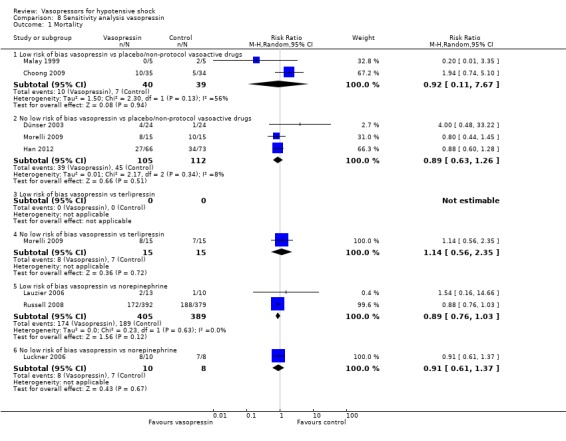

Vasopressin was compared with placebo (non‐protocol vasoactive drugs), terlipressin and norepinephrine/dopamine (eight studies; 1138 participants) (Analysis 3.1). In the comparisons 'versus placebo/non‐protocol vasoactive drugs', two studies actually used a placebo (Choong 2009; Malay 1999), two studies (Dünser 2003; Morelli 2009) compared fixed‐dose vasopressin + variable‐dose norepinephrine versus variable‐dose norepinephrine and one study compared vasopressin versus norepinephrine or dopamine (Han 2012). Overall 503 deaths were observed among 1138 participants. Studies were performed in participants with septic shock (Dünser 2003; Han 2012; Lauzier 2006; Malay 1999; Morelli 2009; Russell 2008), in adult post‐operative participants (Luckner 2006) and in paediatric participants with vasodilatory shock (Choong 2009). In no comparisons was a significant difference found.

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Vasopressin, Outcome 1 Total mortality.

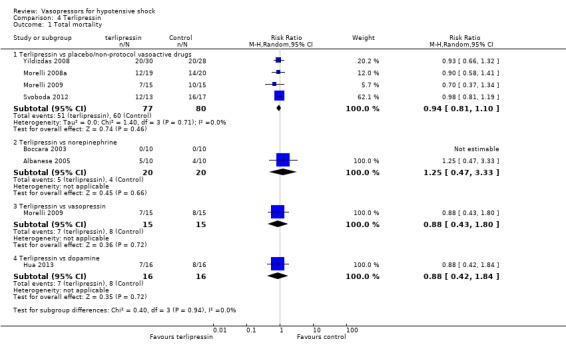

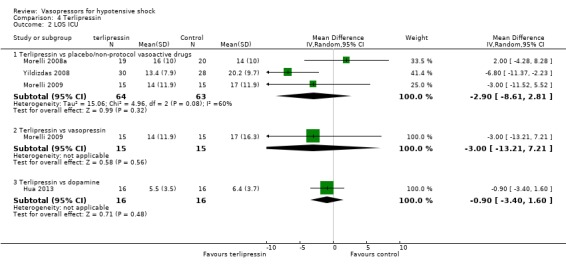

Terlipressin was compared with placebo (non‐protocol vasoactive drugs), norepinephrine and vasopressin (seven studies; 259 participants) (Analysis 4.1). In the comparisons 'versus placebo/non‐protocol vasoactive drugs', one study actually used a placebo (Yildizdas 2008), and three studies (Morelli 2008a; Morelli 2009; Svoboda 2012) compared fixed‐dose terlipressin + variable‐dose norepinephrine versus variable‐dose norepinephrine. In the same study (Morelli 2008a), investigators compared norepinephrine + terlipressin + dobutamine versus non‐protocol vasoactive drugs and found no difference (14/20 vs 14/20; RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.67 to 1.50). In another study, terlipressin was compared with dopamine (Hua 2013). Overall 150 deaths were observed among 259 participants. Studies were performed in participants with septic shock (Albanese 2005; Han 2012; Morelli 2008a; Morelli 2009; Svoboda 2012), in children with catecholamine‐resistant shock (Yildizdas 2008) and in participants with refractory hypotension after anaesthesia (Boccara 2003). No comparisons revealed a significant difference.

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Terlipressin, Outcome 1 Total mortality.

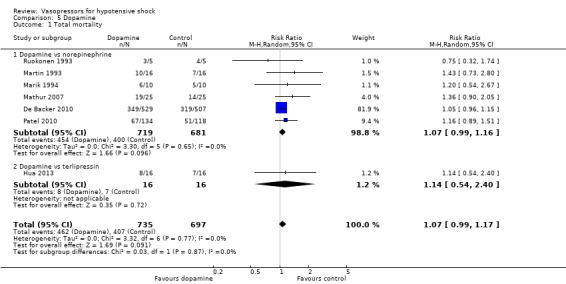

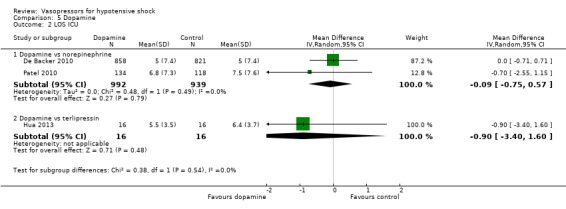

Dopamine was compared with norepinephrine and with terlipressin (seven studies; 1432 participants) (Analysis 5.1). Overall 869 deaths were observed among 1432 participants. Studies were performed in participants with septic shock (Hua 2013; Marik 1994; Martin 1993; Mathur 2007; Patel 2010; Ruokonen 1993) and in participants with several causes of shock (De Backer 2010). In no comparisons was a significant difference found.

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Dopamine, Outcome 1 Total mortality.

Phenylephrine was compared with norepinephrine in participants with septic shock (two studies; 86 participants) (Jain 2010; Morelli 2008b) (Analysis 1.1). Overall 50 deaths were observed among 86 participants (RR 0.92, 95% CI 0.64 to 1.32).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Norepinephrine, Outcome 1 Total mortality.

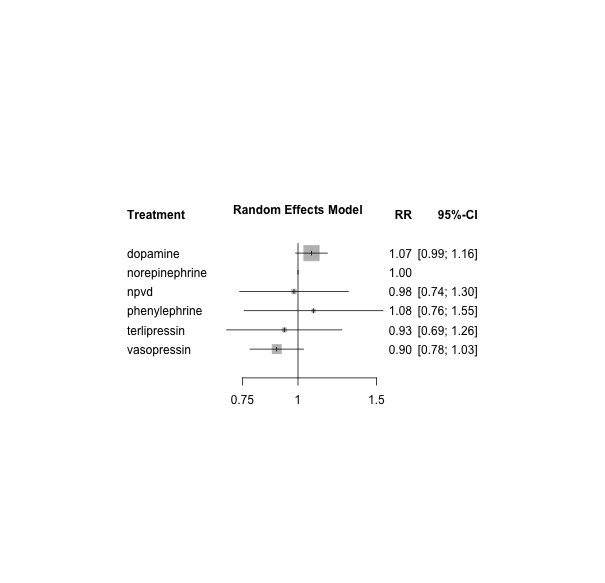

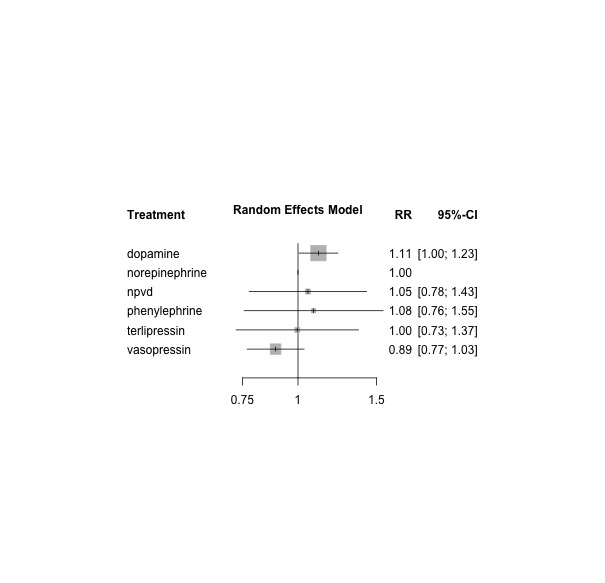

In a network that included vasopressors only (Figure 7), we found no differences in effects of any vasopressor versus non‐protocol vasoactive drugs on mortality, as shown in the network forest plot comparing seven vasopressor regimens versus norepinephrine (Figure 8) from 22 studies with 24 pair‐wise comparisons. Heterogeneity/inconsistency: tau2 < 0.0001; I2 statistic = 0%. Test of heterogeneity/inconsistency: Q = 8.39 (d.f. 17), P value = 0.96. Likewise, no hotspots are evident in the heatplot indicating the absence of specific sources of important inconsistency in the network (see www.meduniwien.ac.at/user/harald.herkner/AppendixCARG029_2015.pdf). For the full network assessment, including measures for characterizing a network meta‐analysis (direct evidence proportion, mean path length, minimal parallelism of mixed treatment comparisons and evidence flow per design) (see www.meduniwien.ac.at/user/harald.herkner/AppendixCARG029_2015.pdf).

7.

Graphical representation of the evidence network including vasopressors showing available direct comparisons. The lines represent direct comparisons, and line thickness is proportional to precision of the estimates (1/SE).

8.

Network forest plot comparing seven vasopressor regimens vs norepinephrine (reference) from 22 studies with 24 pair‐wise comparisons. Heterogeneity/inconsistency: tau2 < 0.0001; I2 statistic = 0%. Test of heterogeneity/inconsistency: Q = 8.48 (d.f. 18), P value = 0.97; 'NPVD' denotes non‐protocol vasoactive drugs with or without placebo. RR denotes risk ratio, as calculated by a fixed‐effect model. RR > 1 indicates increased mortality risk; RR < 1 indicates reduced mortality risk vs norepinephrine (reference).

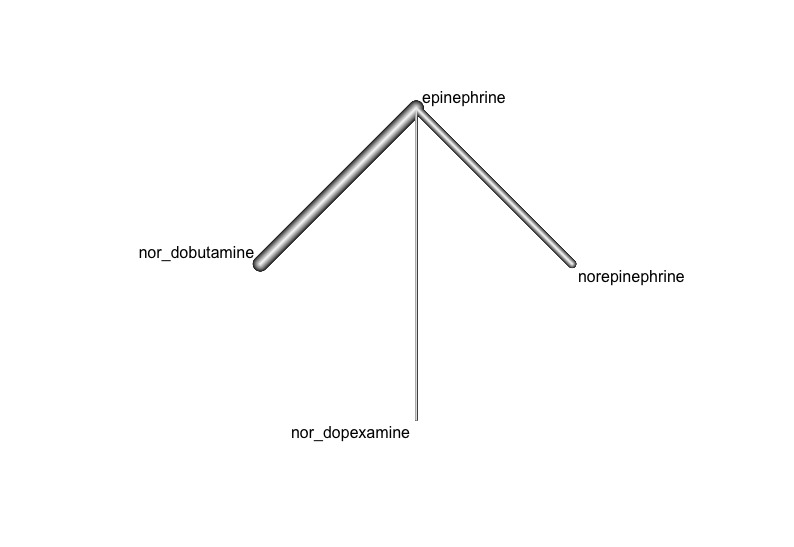

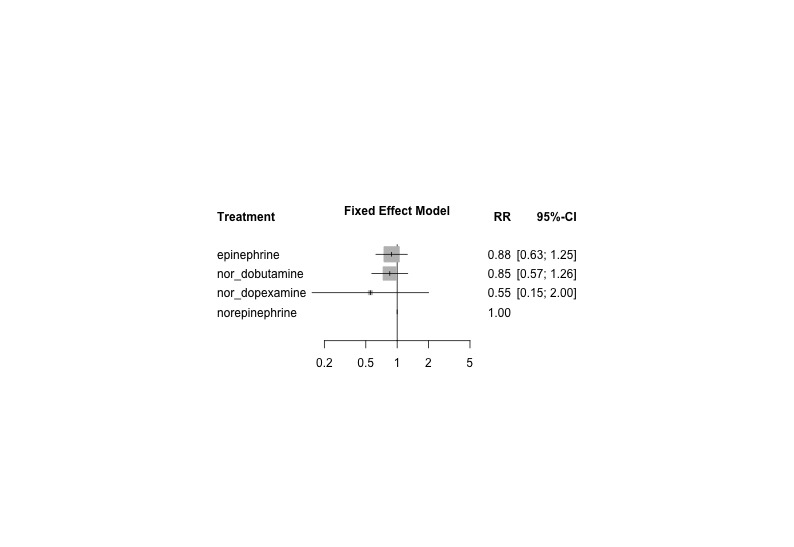

In a network that included vasopressors and combinations with beta‐agonist action (Figure 9), we found no differences in the effects of any vasopressor versus norepinephrine on mortality, as shown in the network forest plot comparing four vasopressor regimens with a beta‐agonist component versus norepinephrine (Figure 10) from six studies with six pair‐wise comparisons. Heterogeneity/inconsistency: tau2 < 0.0001; I2 statistic = 0%. Test of heterogeneity/inconsistency: Q = 0.42 (d.f. 3), P value = 0.94 (Figure 10). No indication of severe heterogeneity/inconsistency was found, although several analyses were not possible with available data. For the full network assessment, see the Appendix (www.meduniwien.ac.at/user/harald.herkner/AppendixCARG029_2015.pdf).

9.

Graphical representation of the evidence network including vasopressors and combinations with beta‐agonist action showing available direct comparisons. The lines represent direct comparisons, and line thickness is proportional to precision of the estimates (1/SE).

10.

Network forest plot comparing four vasopressor regimens with a beta‐agonist component vs norepinephrine (reference) from 6 studies with 6 pair‐wise comparisons. Heterogeneity/inconsistency: tau2 < 0.0001; I2 statistic = 0%. Test of heterogeneity/inconsistency: Q = 0.42(d.f. 3), P value = 0.94; 'nor_' denotes norepinephrine added to the other drugs as described. RR denotes risk ratio, as calculated by a fixed‐effect model. RR > 1 indicates increased mortality risk; RR < 1 indicates reduced mortality risk vs norepinephrine (reference).

Secondary outcomes

Morbidity

Morbidity was assessed as (1a) ICU LOS; (1b) hospital LOS; (1c) duration of vasopressor treatment; (1d) duration of mechanical ventilation; (1e) renal failure (as defined by study authors as oliguria or renal replacement therapy) and (1f) other. Renal outcomes are presented separately in Table 6.

1. Morbidity outcomes ‐ measures of renal function comparing several vasopressor regimens (each single vasopressor is compared with other available vasopressor regimens).

| Vasopressor | Comparator (Reference) | Outcome | Effect* |

| Norepinephrine |

Vasopressin (Lauzier 2006) Vasopressin (Russell 2008) |

Creatinine clearance Days alive free of renal replacement therapy |

54 mL min‐11.73 m‐2 ± 38 vs 122 mL min‐11.73m‐2 ± 66 , P value < 0.001 (23 (IQR 5 to 28) vs 25 (IQR 6 to 28), P value = 0.64) |

| Norepinephrine + terlipressin + dobutamine (Morelli 2008a) |

Urine output 4 hours after study start |

96 mL/h ± 48 vs 130 mL/h ± 76 (P value < 0.05) |

|

| Norepinephrine + terlipressin (Morelli 2008a) |

Urine output 4 hours after study start | 96 mL/h ± 48 vs 147 mL/h ± 119 (P value = 0.08) |

|

| Dopamine (Mathur 2007) Dopamine (De Backer 2010) |

Post‐treatment urine output Days free of renal support within 28 days |

1.17 mL/kg/h ± 0.47 vs 0.81 mL/kg/h ± 0.75, P value < 0.05 14.0 ± 12.3 days vs 12.8 ± 12.4 days, P value = 0.07 |

|

| Phenylephrine (Morelli 2008b) |

Creatinine clearance Urine output |

No difference (P value = 0.61) No difference (P value = 0.17) |

|

| Terlipressin (Boccara 2003) | Renal failure post‐operatively |

(0/10 vs 0/10) |

|

| Terlipressin + norepinephrine and vasopressin + norepinephrine (Morelli 2009) |

Need for renal replacement therapy |

(8/15 vs 4/15 vs 5/15, P value = 0.29) |

|

| Epinephrine | Norepinephrine + dobutamine (Levy 1997) |

Oliguria reversal |

9/12 vs 10/11 RR 0.36 (95% CI 0.04 to 3.00) |

| Vasopressin |

Norepinephrine (Lauzier 2006) Norepinephrine (Russell 2008) Norepinephrine vs terlipressin (Morelli 2009) |

Creatinine clearance Days alive free of renal replacement therapy Need for renal replacement therapy |

122 mL min‐11.73m‐2 ± 66 vs 54 mL min‐11.73m‐2 ± 38, P value < 0.001 25 (IQR 6 to 28) vs 23 (IQR 5 to 28), P value = 0.64 8/15 vs 4/15 vs 5/15, P value = 0.29 |

| Placebo/non‐protocol vasoactive drugs (Choong 2009) Placebo/non‐protocol vasoactive drugs (Malay 1999) |

Urine output Creatinine |

1.7 mL/kg/h (IQR 0.7 to 3.5) vs 1.5 mL/kg/h (IQR 0.7 to 3.7), P value = 0.65 N/A |

|

| Terlipressin |

Norepinephrine vs vasopressin (Morelli 2009) |

Need for renal replacement therapy |

8/15 vs 4/15 vs 5/15, P value = 0.29 |

| Placebo/non‐protocol vasoactive drugs in patients taking norepinephrine (Morelli 2008a) | Urine output 4 hours after study start |

147 mL/h ± 119 vs 96 mL/h ± 48 (P value = 0.08) |

|

| Dopamine | Norepinephrine (Mathur 2007) Norepinephrine (De Backer 2010) |

Post‐treatment urine output Days free of renal support within 28 days |

0.81 mL/kg/h ± 0.75 vs 1.17 mL/kg/h ± 0.47, P value < 0.05 12.8 ± 12.4 days vs 14.0 ± 12.3 days, P value = 0.07 |

*All effects are presented as outcomes in the vasopressor group (left hand column) versus comparator (second column) with risk ratio or P value for differences between groups

CI = confidence interval

IQR = 25% to 75% interquartile range

N/A = not applicable

RR = risk ratio

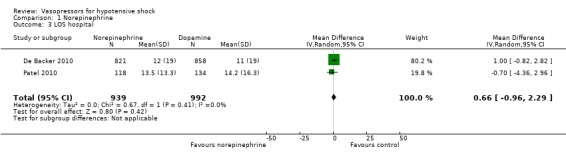

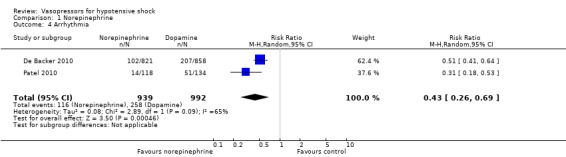

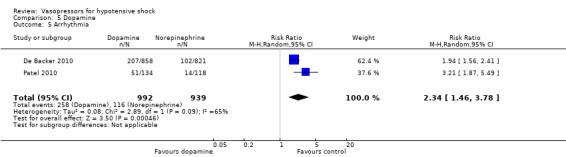

Norepinephrine was compared with dopamine, vasopressin, phenylephrine and norepinephrine + terlipressin + dobutamine in terms of (1a) ICU LOS (five studies; 2781 participants) (Analysis 1.2). All studies included participants with septic shock. Investigators reported no differences in (1a) ICU LOS and (1b) hospital LOS (Analysis 1.2; Analysis 1.3). Additionally, Russell 2008 compared norepinephrine versus vasopressin and found no significant differences in (1b) hospital LOS (difference 1.00 day, 95% CI ‐3.01 to 5.01). Further, they reported no significant differences in (1c) vasopressor use (17, interquartile range (IQR) 0 to 24 vs 19, IQR 0 to 24; P value = 0.61) and (1d) days alive free of mechanical ventilation (six, IQR 0 to 20 vs 9, IQR 0 to 20; P value = 0.24). Myburgh 2008 compared norepinephrine with epinephrine and found no differences in the number of (1c) vasopressor‐free days (25 days, IQR 14 to 27 vs 26 days, IQR 19 to 27; P value = 0.31). De Backer 2010 compared norepinephrine with dopamine and found no differences in days free of mechanical ventilation within 28 days (9.5 ± 11.4 days vs 8.5 ± 11.2 days; P value = 0.13). They noted a small difference in (1c) days free of any vasopressor therapy within 28 days (14.2 ± 12.3 days vs 12.6 ± 12.5 days; P value = 0.007). The largest study by De Backer 2010 and a smaller study by Patel 2010 compared dopamine versus norepinephrine and found significant differences in (1f) arrhythmia (Analysis 1.4), including mostly sinus tachycardia (Patel 2010): 25% versus 6%; atrial fibrillation: 21% versus 11% (De Backer 2010), 13% versus 3% (Patel 2010); ventricular tachycardia (De Backer 2010): 2.4% versus 1.0%; and ventricular fibrillation (De Backer 2010): 1.2% versus 0.5%. Boccara 2003 compared noradrenaline with terlipressin and found no differences in (1b) hospital LOS (5 days, IQR 4 to 7 vs 5 days, IQR 4 to 7).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Norepinephrine, Outcome 2 LOS ICU.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Norepinephrine, Outcome 3 LOS hospital.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Norepinephrine, Outcome 4 Arrhythmia.

Epinephrine was compared with norepinephrine + dobutamine in terms of (1a) ICU LOS in participants with septic shock (one study; 330 participants) (Annane 2007). Researchers reported no significant differences in ICU LOS (difference 1.00 day, 95% CI ‐3.01 to 5.01). In the same study (Annane 2007), the number of (1c) vasopressor‐free days until day 90 was reported as a median 53 days (IQR 0 to 86) in the epinephrine group and 66 days (IQR 6 to 86) in the norepinephrine + dobutamine group (P value = 0.18). In the same study, duration of (1c) vasopressor support was presented as a Kaplan‐Meier plot (log‐rank test P value = 0.09). Myburgh 2008 compared epinephrine with norepinephrine and found no differences in the number of (1c) vasopressor‐free days (26 days, IQR 19 to 27 vs 25 days, IQR 14 to 27; P value = 0.31).

Vasopressin was compared with placebo (non‐protocol vasoactive drugs), terlipressin and norepinephrine in terms of (1a) ICU LOS (four studies; 1046 participants) (Analysis 3.2). Studies were performed in participants with septic shock (Morelli 2009; Russell 2008) and paediatric vasodilatory shock (Choong 2009). In no comparison was a significant difference found. Vasopressin was compared with norepinephrine in terms of (1b) hospital LOS in one study (Russell 2008), and no significant difference was found (difference 1.00 day, 95% CI ‐3.01 to 5.01). Further, researchers noted no significant differences in (1c) vasopressor use (19, IQR 0 to 24 vs 17, IQR 0 to 24; P value = 0.61) and (1d) days alive free of mechanical ventilation (9, IQR 0 to 20 vs 6, IQR 0 to 20; P value = 0.24). Choong 2009 compared vasopressin with placebo/non‐protocol vasoactive drugs in paediatric participants and found no differences in (1c) time to vasopressor discontinuation (50 hours, IQR 30 to 219 vs 47, IQR 26 to 87; P value = 0.85) and (1d) mechanical ventilation‐free days until day 30 (17 days, IQR 0 to 24 vs 23 days, IQR 13 to 26; P value = 0.15). Han 2012 compared vasopressin with non‐protocol vasoactive drugs and found no differences in (1a) LOS (five days (IQR 3 to 8) vs five days (IQR 3 to 8) and (1d) duration of mechanical ventilation (4 days (IQR 3 to 6) vs 4 days (IQR 2 to 5); P value > 0.05),

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Vasopressin, Outcome 2 LOS ICU.

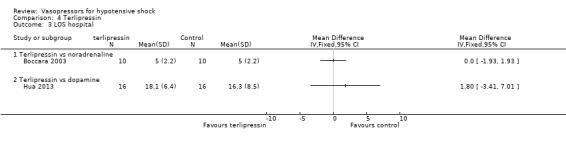

Terlipressin was compared with placebo (non‐protocol vasoactive drugs) (six studies; 185 participants) (Morelli 2008a; Morelli 2009; Svoboda 2012; Yildizdas 2008), dopamine (Hua 2013), norepinephrine (Boccara 2003) and vasopressin (Morelli 2009) in terms of (1a) ICU LOS (Analysis 4.2), (1b) hospital LOS (Analysis 4.3), (1c) pressor‐free days until day 28 (Analysis 4.5), (1d) duration of mechanical ventilation (Analysis 4.4) and (1f) serious adverse events (Analysis 4.6). In comparisons summarized as 'versus placebo/non‐protocol vasoactive drugs', one study actually used placebo (Yildizdas 2008); in two studies (Morelli 2008a; Morelli 2009), fixed‐dose terlipressin + variable dose norepinephrine was compared with variable‐dose norepinephrine. Studies were performed in participants with septic shock (Morelli 2008a; Morelli 2009; Svoboda 2012) and in children with catecholamine‐resistant shock (Yildizdas 2008), peri‐operative refractory hypotension (Boccara 2003) and acute respiratory distress syndrome (Hua 2013). In no comparison was a significant difference found.

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Terlipressin, Outcome 2 LOS ICU.

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Terlipressin, Outcome 3 LOS hospital.

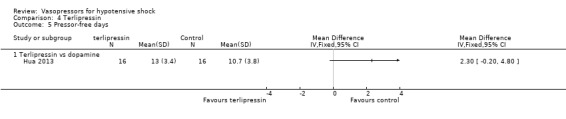

4.5. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Terlipressin, Outcome 5 Pressor‐free days.

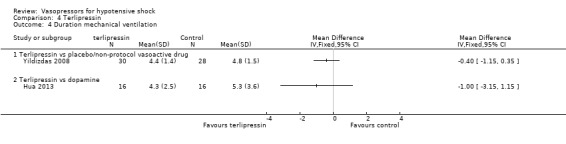

4.4. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Terlipressin, Outcome 4 Duration mechanical ventilation.

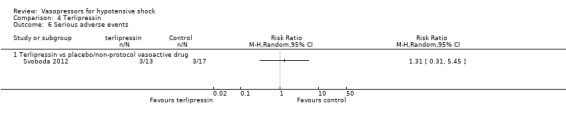

4.6. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Terlipressin, Outcome 6 Serious adverse events.

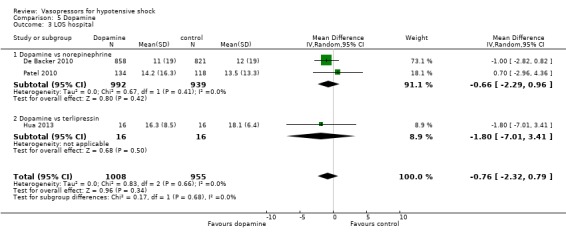

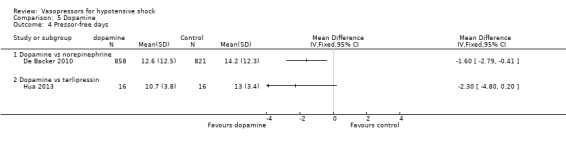

Dopamine was compared with norepinephrine (two studies; 1931 participants; De Backer 2010; Patel 2010) and terlipressin (one study; 32 participants) Hua 2013) in terms of (1a) ICU LOS (Analysis 5.2), (1b) hospital LOS (Analysis 5.3), (1c) pressor‐free days until day 28 (Analysis 5.4) and (1f) arrhythmia (Analysis 5.5). De Backer 2010 and Patel 2010 compared dopamine with norepinephrine and found no differences in (1a) ICU LOS and (1b) hospital LOS (Analysis 5.2; Analysis 5.3). Further, De Backer 2010 assessed (1d) days free of mechanical ventilation within 28 days (8.5 ± 11.2 days vs 9.5 ± 11.4 days; P value = 0.13). Hua 2013 compared dopamine with noradrenaline for duration of mechanical ventilation (5.3 ± 3.6 days vs 4.3 ± 2.5 days; difference 1.00, 95% CI ‐1.15 to 3.15).

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Dopamine, Outcome 2 LOS ICU.

5.3. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Dopamine, Outcome 3 LOS hospital.

5.4. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Dopamine, Outcome 4 Pressor‐free days.

5.5. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Dopamine, Outcome 5 Arrhythmia.

De Backer 2010 reported a small difference in (1c) days free of any vasopressor therapy within 28 days (12.6 ± 12.5 days vs 14.2 ± 12.3 days; P value = 0.007; Analysis 5.4). The largest study by De Backer 2010 and a smaller study by Patel 2010 compared dopamine versus norepinephrine and found significant differences in (1f) arrhythmias (Analysis 5.5), including mostly sinus tachycardia (Patel 2010): 25% versus 6%; atrial fibrillation: 21% versus 11% (De Backer 2010), 13% versus 3% (Patel 2010); ventricular tachycardia (De Backer 2010): 2.4% versus 1.0%; and ventricular fibrillation (De Backer 2010): 1.2% versus 0.5%.

Phenylephrine was compared with norepinephrine in participants with septic shock (one study; 32 participants) (Morelli 2008b). Mean (1a) ICU LOS was 16 ± 13 versus 16 ± 10 days (difference 0.00 days, 95% CI ‐8.27 to 8.27).

Measures of health‐related quality of life and measures of anxiety and depression

In no studies were measures of health‐related quality of life assessed. In no studies were measures of anxiety and depression assessed.

Subgroup analysis

Among the network of vasopressors versus combinations of vasopressors, 18 studies provided data on participants with septic shock. In 17 studies, septic shock was an eligibility criterion; in one study, data on a subgroup of participants with septic shock were available for day 28 (De Backer 2010). Overall 20 study arms included 2706 participants with 1370 mortality outcomes. The network forest plot is presented as Figure 11. In this subgroup analysis, dopamine was inferior to norepinephrine (dopamine vs norepinephrine RR 1.11, 95% CI 1.005 to 1.23).

11.

Subgroup analysis in patients with septic shock: network forest plot comparing 7 vasopressor regimens vs norepinephrine (reference) from 18 studies with 20 pair‐wise comparisons. Heterogeneity/inconsistency: tau2 < 0.0001; I2 statistic = 0%. Test of heterogeneity/inconsistency: Q = 5.21, d.f. = 14, P value = 0.98; 'NPVD' denotes non‐protocol vasoactive drugs with or without placebo. RR denotes risk ratio, as calculated by a fixed‐effect model. RR > 1 indicates increased mortality risk; RR < 1 indicates reduced mortality risk vs norepinephrine (reference).

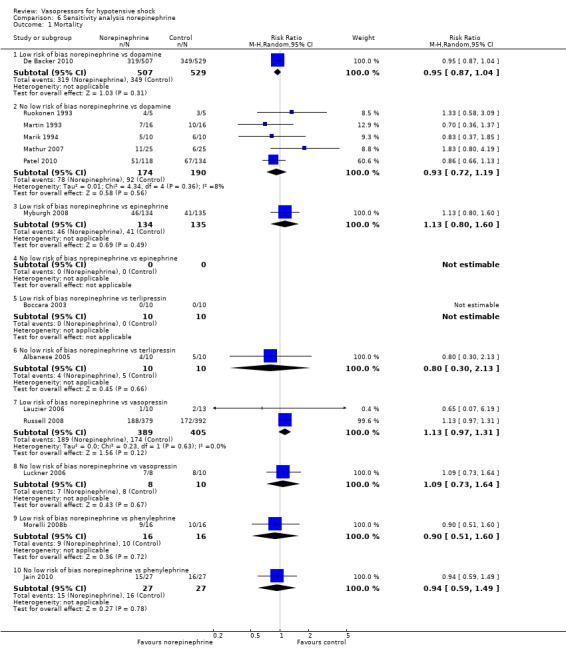

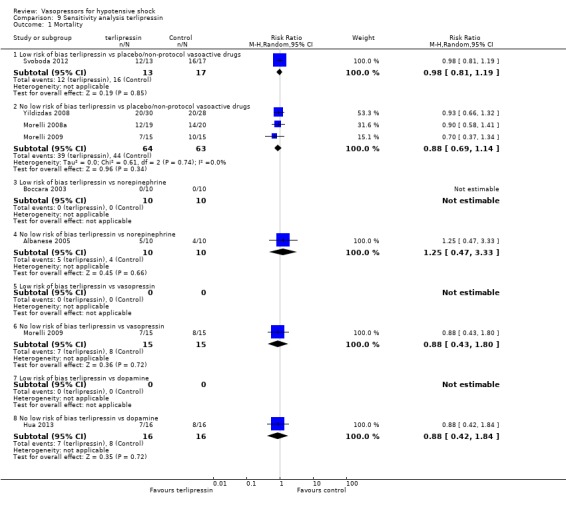

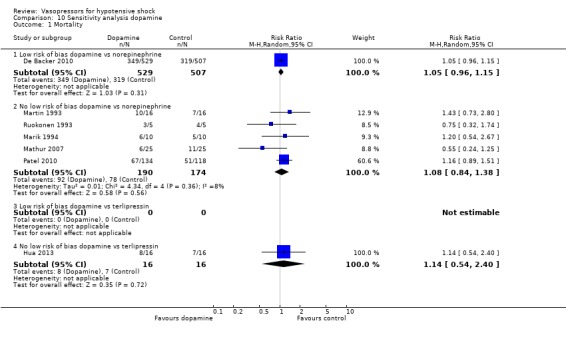

Sensitivity analysis

We classified 11 studies (1148 participants) as having low risk of bias for the primary outcome of mortality (Annane 2007; Boccara 2003; Choong 2009; De Backer 2010; Lauzier 2006; Malay 1999; Morelli 2008b; Myburgh 2008; Russell 2008; Seguin 2006; Svoboda 2012); for the remaining studies, at least some risk of bias could not be excluded because information was lacking, or because high risk of bias was indicated by the study design.

In no comparisons did within‐study risk of bias seem to affect overall estimates (Analysis 6.1; Analysis 7.1; Analysis 8.1; Analysis 9.1; Analysis 10.1).

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Sensitivity analysis norepinephrine, Outcome 1 Mortality.

7.1. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Sensitivity analysis epinephrine, Outcome 1 Mortality.

8.1. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Sensitivity analysis vasopressin, Outcome 1 Mortality.

9.1. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Sensitivity analysis terlipressin, Outcome 1 Mortality.

10.1. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Sensitivity analysis dopamine, Outcome 1 Mortality.

In all comparisons, heterogeneous mortality outcomes were included (Analysis 1.1; Analysis 2.1; Analysis 3.1; Analysis 4.1; Analysis 5.1).

For the comparison of norepinephrine versus dopamine (six studies; 1400 participants) (Analysis 1.1), effects of using the latest mortality outcome yielded an RR of 0.93 (95% CI 0.86 to 1.01) as compared with an RR of 0.92 (95% CI 0.85 to 1.01; analysis not shown) if 28‐day mortality, hospital mortality and undetermined periods were acknowledged.

For the comparison of epinephrine versus norepinephrine + dobutamine (four studies; 412 participants) (Analysis 2.1), effects of using the latest mortality outcome included an RR of 1.04 (95% CI 0.86 to 1.26) as compared with an RR of 1.19 (95% CI 0.92 to 1.54; analysis not shown) if 28‐day mortality and undetermined periods were acknowledged.

For the comparison of vasopressin versus non‐protocol vasoactive drugs (five studies; 296 participants) (Analysis 3.1), effects of using the latest mortality outcome included an RR of 0.92 (95% CI 0.69 to 1.22) as compared with an RR of 0.90 (95% CI 0.06 to 12.64; analysis not shown) if restricted to studies reporting 24‐hour mortality (Dünser 2003; Malay 1999), and an RR of 1.05 (95% CI 0.63 to 1.75; analysis not shown) if restricted to studies reporting 30‐day or ICU mortality (Choong 2009; Dünser 2003; Morelli 2009).

For the comparison of norepinephrine versus vasopressin (three studies; 812 participants) (Analysis 1.1), effects of using the latest mortality outcome included an RR of 1.12 (95% CI 0.98 to 1.29) as compared with an RR of 1.10 (95% CI 0.94 to 1.30; analysis not shown) if 28‐day mortality and ICU mortality were acknowledged. In the comparison of terlipressin and non‐protocol vasoactive drugs, ICU mortality and 90‐day mortality were combined. Choosing time points other than 90 days had no significant impact on the estimates (Analysis 4.1).

In summary, estimates remained virtually unchanged if definitions of mortality were changed, or if studies with different mortality definitions were compared.

Assessment of reporting bias

Funnel plots of the primary outcome of all comparisons did not suggest major asymmetry. We present the funnel plot for comparison 1.1 (see Figure 5). We identified too few studies per comparison to sensibly perform a formal test for funnel plot asymmetry. Overall, however, reporting bias does not seem to be a major problem in this review and in particular does not explain the results.

Discussion

Summary of main results

We found 28 studies that fulfilled our inclusion criteria. Overall 3497 participants with 1773 mortality outcomes were analysed. Information was derived mainly from six studies (Annane 2007; De Backer 2010; Han 2012; Myburgh 2008; Patel 2010; Russell 2008) that reported on 2797 participants (80% of total) and 1463 mortality outcomes (83% of total mortality outcomes) across all comparisons. Six different vasopressors, given alone or in combination with dobutamine or dopexamine, were compared in 12 different combinations.

All 28 studies reported mortality outcomes. Length of stay (LOS) was reported in 12 studies (Annane 2007; Boccara 2003; Choong 2009; De Backer 2010; Han 2012; Hua 2013; Morelli 2008a; Morelli 2008b; Morelli 2009; Patel 2010; Russell 2008; Yildizdas 2008). Other morbidity outcomes were reported in a variable and heterogeneous way. No data were available on quality of life nor on anxiety and depression outcomes.

In summary, investigators reported no differences in mortality outcomes in any of the studies comparing different vasopressors or combinations. In particular, for the comparison between dopamine and norepinephrine, which included most participants, researchers observed no differences in mortality (Table 1). The same results were obtained by our network meta‐analysis (Figure 9; Figure 10).

De Backer 2010 and Patel 2010 when comparing dopamine versus norepinephrine found higher risk of arrhythmia in the dopamine group (Analysis 1.4). In total, 347 arrhythmia episodes were documented in 1891 participants (Table 1). Other adverse events such as new infectious episodes, skin ischaemias and arterial occlusion did not differ between intervention groups.

We found no differences in other relevant morbidity outcomes within any comparisons. This finding was consistent among the few large studies identified, as well as in studies with different levels of within‐study bias risk. Overall the quality of the evidence ranged from high to very low across comparisons.

Our review included no pre‐defined subgroup analyses; therefore, we cannot make strong inferences about whether effects of vasopressors differ across populations with different causes of shock. However, in one of the large trials comparing norepinephrine versus dopamine (De Backer 2010), a pre‐defined subgroup analysis according to shock type revealed a beneficial effect on 28‐day mortality among participants with cardiogenic shock treated with norepinephrine. However, although subgroups were pre‐defined, randomization was not stratified; moreover the test for subgroup differences (P value = 0.87) suggests that this subgroup effect can be explained by chance alone.

No evidence suggests that any of the investigated vasopressors are clearly superior over others.

Nine studies can be regarded as placebo/non‐protocol vasoactive drug controlled add‐on studies. Morelli 2008a and Morelli 2009 compared norepinephrine versus norepinephrine + terlipressin and dobutamine, which might be seen as add‐on therapy of terlipressin + dobutamine versus no extra vasopressor in participants receiving norepinephrine. Investigators reported no differences in mortality or in LOS. Likewise Morelli 2009 compared a vasopressin + norepinephrine arm versus a norepinephrine alone arm. This add‐on vasopressin therapy did not have an effect. Yildizdas 2008 compared terlipressin versus placebo in paediatric patients with septic shock who did not respond to fluid resuscitation and high‐dose catecholamines, and found no differences in mortality but significant reduction of LOS. This effect was no longer found when data were combined with those from Morelli 2008a. Malay 1999 and Han 2012 studied vasopressin versus non‐protocol vasoactive drugs in participants with septic shock who were already taking catecholamines; Dünser 2003 and Svoboda 2012 compared norepinephrine versus norepinephrine + vasopressin; Choong 2009 compared vasopressin versus placebo in paediatric patients with vasodilatory shock after volume resuscitation under catecholamines. In none of these comparisons could a significant effect on mortality or morbidity be found. This result must not be interpreted as showing no effects of vasopressors versus placebo at all. Moreover, these results indicate that in participants requiring massive vasoactive support, additional vasopressors have no major effect. It is noteworthy that this evidence on placebo/non‐protocol vasoactive drug comparisons comes from a few small studies only and therefore must be interpreted with additional caution.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Even though 28 studies met our inclusion criteria, numerous comparisons were necessary. Accordingly, the actual number of studies per comparison, as well as the number of participants in most studies, was small. Therefore, some comparisons resulted in under‐powered effects. Also only limited subgroup analyses could be performed to investigate potential sources of heterogeneity.

Quality of the evidence

Overall quality of the evidence ranged from high to very low. Only four studies (Annane 2007; Choong 2009; De Backer 2010; Russell 2008) fulfilled all criteria for the risk of bias assessment (Figure 3). However, when only bias items that were assumed to strongly influence the effects were considered, 11 studies were classified as having low risk of bias. Small‐study bias usually tends to overestimate a true effect, but on the other hand, in the case of a null effect, limited power to exclude the absence of an effect may matter more. Many comparisons must be interpreted with caution. In summary, however, within‐study bias does not seem to explain our findings.

Studies were too few for review authors to examine reporting bias in detail. However, as no obvious asymmetry in funnel plots was considered, and given that the comprehensive search strategy used several electronic databases without restrictions, as well as trial registers and experts in the field, reporting bias may not be a major source of distortion.