Abstract

Background

Therapist‐delivered trauma‐focused psychological therapies are an effective treatment for post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). These have become the accepted first‐line treatments for the disorder. Despite the established evidence‐base for these therapies, they are not always widely available or accessible. Many barriers limit treatment uptake, such as the limited number of qualified therapists to deliver the interventions, cost, and compliance issues, such as time off work, childcare, and transportation, associated with the need to attend weekly appointments. Delivering cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) on the Internet is an effective and acceptable alternative to therapist‐delivered treatments for anxiety and depression. However, fewer Internet‐based therapies have been developed and evaluated for PTSD, and uncertainty surrounds the efficacy of Internet‐based cognitive and behavioural therapy (I‐C/BT) for PTSD.

Objectives

To assess the effects of I‐C/BT for PTSD in adults.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Common Mental Disorders Group's Specialised Register (CCMDCTR) to June 2016 and identified four studies meeting the inclusion criteria. The CCMDCTR includes relevant randomised controlled trials (RCT) from MEDLINE, Embase, and PsycINFO. We also searched online clinical trial registries and reference lists of included studies, and contacted researchers in the field to identify additional and ongoing studies. We ran an update search on 1 March 2018, and identified four additional completed studies, which we added to the analyses along with two that were previously awaiting classification.

Selection criteria

We searched for RCTs of I‐C/BT compared to face‐to‐face or Internet‐based psychological treatment, psychoeducation, wait list or care as usual. We included studies of adults (aged over 16 years or over), in which at least 70% of the participants met the diagnostic criteria for PTSD, according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) or the International Classification of Diseases (ICD).

Data collection and analysis

We entered data into Review Manager 5 software. We analysed categorical outcomes as risk ratios (RRs), and continuous outcomes as mean differences (MD) or standardised mean differences (SMDs), with 95% confidence intervals (CI). We pooled data with a fixed‐effect meta‐analysis, except where heterogeneity was present, in which case we used a random‐effects model. Two review authors independently assessed the included studies for risk of bias; any conflicts were discussed with a third author, with the aim of reaching a unanimous decision.

Main results

We included 10 studies with 720 participants in the review. Eight of the studies compared I‐C/BT delivered with therapist guidance to a wait list control. Two studies compared guided I‐C/BT with I‐non‐C/BT. There was considerable heterogeneity among the included studies.

Very low‐quality evidence showed that, compared with wait list, I‐C/BT may be associated with a clinically important reduction in PTSD post‐treatment (SMD –0.60, 95% CI –0.97 to –0.24; studies = 8, participants = 560). However, there was no evidence of a difference in PTSD symptoms when follow‐up was less than six months (SMD –0.43, 95% CI –1.41 to 0.56; studies = 3, participants = 146). There may be little or no difference in dropout rates between the I‐C/BT and wait list groups (RR 1.39, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.88; studies = 8, participants = 585; low‐quality evidence). I‐C/BT was no more effective than wait list at reducing the risk of a diagnosis of PTSD after treatment (RR 0.53, 95% CI 0.28 to 1.00; studies = 1, participants = 62; very low‐quality evidence). I‐C/BT may be associated with a clinically important reduction in symptoms of depression both post‐treatment (SMD –0.61, 95% CI –1.17 to –0.05; studies = 5, participants = 425; very low‐quality evidence). Very low‐quality evidence also suggested that I‐C/BT may be associated with a clinically important reduction in symptoms of anxiety post‐treatment (SMD –0.67, 95% CI –0.98 to –0.36; studies = 4, participants = 305), and at follow‐up less than six months (MD –12.59, 95% CI –20.74 to –4.44; studies = 1, participants = 42; very low‐quality evidence). The effects of I‐C/BT on quality of life were uncertain (SMD 0.60, 95% CI 0.08 to 1.12; studies = 2, participants = 221; very low‐quality evidence).

Two studies found no difference in PTSD symptoms between the I‐C/BT and I‐non‐C/BT groups when measured post‐treatment (SMD –0.08, 95% CI –0.52 to 0.35; studies = 2, participants = 82; very low‐quality evidence), or when follow‐up was less than six months (SMD 0.08, 95% CI –0.41 to 0.57; studies = 2, participants = 65; very low‐quality evidence). However, those who received I‐C/BT reported their PTSD symptoms were better at six‐ to 12‐month follow‐up (MD –8.83, 95% CI –17.32 to –0.34; studies = 1, participants = 18; very low‐quality evidence). Two studies found no difference in depressive symptoms between the I‐C/BT and I‐non‐C/BT groups when measured post‐treatment (SMD –0.12, 95% CI –0.78 to 0.54; studies = 2, participants = 84; very low‐quality evidence) or when follow‐up was less than six months (SMD 0.20, 95% CI –0.31 to 0.71; studies = 2, participants = 61; very low‐quality evidence). However, those who received I‐C/BT reported their depressive symptoms were better at six‐ to 12‐month follow‐up (MD –8.34, 95% CI –15.83 to –0.85; studies = 1, participants = 18; very low‐quality evidence). Two studies found no difference in symptoms of anxiety between the I‐C/BT and I‐non‐C/BT groups when measured post‐treatment (SMD 0.08, 95% CI –0.78 to 0.95; studies = 2, participants = 74; very low‐quality evidence) or when follow‐up was less than six months (SMD –0.16, 95% CI –0.67 to 0.35; studies = 2, participants = 60; very low‐quality evidence). However, those who received I‐C/BT reported their symptoms of anxiety were better at six‐ to 12‐month follow‐up (MD –8.05, 95% CI –15.20 to –0.90; studies = 1, participants = 18; very low‐quality evidence).

None of the included studies reported on cost‐effectiveness or adverse events.

Authors' conclusions

While the review found some beneficial effects of I‐C/BT for PTSD, the quality of the evidence was very low due to the small number of included trials. Further work is required to: establish non‐inferiority to current first‐line interventions, explore mechanisms of change, establish optimal levels of guidance, explore cost‐effectiveness, measure adverse events, and determine predictors of efficacy and dropout.

Plain language summary

Internet‐based cognitive and behavioural therapies for post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

Why was this review important?

Post‐traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD, is a common mental illness that can occur after a serious traumatic event. Symptoms include re‐experiencing the trauma as nightmares, flashbacks, and distressing thoughts; avoiding reminders of the traumatic event; experiencing negative changes to thoughts and mood; and hyperarousal, which includes feeling on edge, being easily startled, feeling angry, having difficulties sleeping, and problems concentrating. PTSD can be treated effectively with talking therapies that focus on the trauma. Some of the most effective therapies are those based on cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT). Unfortunately, there are a limited number of qualified therapists who are able to deliver these therapies. There are also other factors that limit access to treatment, such as taking time off work to attend appointments, and transportation issues.

An alternative is to deliver psychological therapy on the Internet, with or without guidance from a therapist. Internet‐based cognitive and behavioural therapies (I‐C/BT) have received a great deal of attention, and are now used routinely to treat depression and anxiety. There have been fewer studies of I‐C/BT for PTSD, and we do not yet know whether they are effective.

Who will be interested in this review?

• People with PTSD and their loved ones.

• Professionals working in mental health services.

• General practitioners.

• Commissioners.

What questions did this review try to answer?

In adults with PTSD, we tried to find out if I‐C/BT:

• was more effective than no therapy (waiting list);

• was as effective as psychological therapies delivered by a therapist;

• was more effective than other psychological therapies delivered online; or

• was more effective than education about the condition delivered online, at reducing symptoms of PTSD, and improving quality of life; or

• was cost effective, compared to face‐to‐face therapy?

Which studies were included in the review?

We searched for randomised controlled trials (clinical studies where people are randomly put into one of two or more treatment groups) that examined I‐C/BT for adults with PTSD, published between 1970 and 2 March 2018.

We included 10 studies with 720 participants.

What did the evidence from the review tell us?

• Very low‐quality evidence from eight studies found that I‐C/BT was more effective than no therapy (waiting list) at reducing symptoms of PTSD.

• Very low‐quality evidence from two studies found no significant difference between I‐C/BT and another type of psychological therapy delivered online.

• We found no studies that compared I‐C/BT to psychological therapy delivered by a therapist, or education about the condition delivered online.

• We found no evidence to tell us whether people who received I‐C/BT felt it was an acceptable treatment, or whether it was effective in improving quality of life.

• We found no studies that reported on the cost effectiveness of I‐C/BT.

What should happen next?

The current evidence base is small. More studies are needed to decide if I‐C/BT should be used routinely for the treatment of PTSD.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is characterised by the development of distressing psychological symptoms following exposure to a traumatic event (APA 2013). Exposure can involve direct personal experience, or can occur when witnessing a traumatic event happening to another person. Qualifying traumas are "of an exceptionally threatening or catastrophic nature, which is likely to cause pervasive distress in almost anyone" (WHO 1992). PTSD does not represent a valid diagnosis after life‐events such as divorce or losing a job.

Diagnostic symptoms of PTSD include re‐experiencing the trauma as upsetting thoughts, nightmares, or flashbacks; avoiding thoughts about the trauma or reminders of it; negative alterations in mood or cognitions, including difficulties recalling the trauma and constricted affect; and heightened physiological arousal, which can manifest as hypervigilance, exaggerated startle responses, and difficulties concentrating or sleeping. Diagnosis is dependent on symptoms that cause clinically significant distress and impairment to the person's capacity to work, socialise, or function in other important domains (APA 2013).

PTSD is a common disorder that imposes a significant personal and societal burden. Epidemiological research suggests that 60% of men and 50% of women experience at least one PTSD‐qualifying traumatic event through the course of their lives (Kessler 1995). Lifetime prevalence of PTSD in Europe has been estimated at between 1.9% (Alonso 2014) and 11% (Ferry 2010); one large‐scale survey in Australia reported a 12‐month prevalence of 1.33% (Creamer 2001), and a survey in Mexico revealed a lifetime prevalence rate of 11.2% (Norris 2003). Approximately 50% of people diagnosed with PTSD recover within two years, while about a third continue to meet criteria for diagnosis six years later (Kessler 1995).

There is substantial comorbidity between PTSD and other psychiatric disorders. One large‐scale survey in the USA revealed the coexistence of at least one additional disorder in 88.3% of men and 79% of women with a history of PTSD (Kessler 1995). One UK survey found that people with PTSD were twice as likely as people without PTSD to have at least one other comorbid mood, anxiety, or substance‐use disorder (NICTT 2008). Risk factors for the development of PTSD include pretrauma factors, such as psychiatric history and traumatic events; peritrauma factors, such as trauma severity and dissociation; and post‐trauma factors, such as poor social support (Brewin 2000; Ozer 2003).

Description of the intervention

International guidelines for the treatment of PTSD converge on the recommendation of trauma‐focused psychological therapies, including trauma‐focused cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), as effective treatments for the disorder (ACPMH 2007; APA 2004; NCCMH 2005). These are currently the treatments of choice for people with PTSD, but evidence is insufficient to support the use of pharmacotherapy in isolation, or the provision of non‐trauma‐focused psychological therapies, such as CBT without a trauma focus, supportive therapy, non‐directive counselling, psychodynamic therapy, and present‐centred therapy (NCCMH 2005). A shortage of suitably qualified and trained therapists who can deliver these interventions has prompted interest in new interventions that place less reliance on therapist time (Lewis 2013).

Internet‐based cognitive and behavioural therapies (I‐C/BT) deliver treatment protocols online using multi‐media delivery methods (Cuijpers 2008). Therapists provide sufficient instruction to teach coping skills, or bring about improvement in target symptoms with limited therapist input (Spek 2007). I‐C/BT programmes have been developed and implemented for a range of disorders, with the aim of reducing healthcare expenditures and broadening access to psychological therapies (Lewis 2010). The content of existing therapies is not usually altered, deviating from traditional psychological treatment only in terms of method of delivery (Cuijpers 2010).

The distinction between I‐C/BT and online psychoeducation must be clear. Although the two overlap in content, psychoeducation aims to increase patient knowledge, while I‐C/BT aims to teach skills and techniques that can be used to overcome specific symptoms (IAPT 2010). I‐C/BT programmes are usually based on existing protocols, and share many common features (Andersson 2005). Most start treatment with psychoeducation, and then present the rationale for CBT‐based treatment (IAPT 2010). These programmes incorporate cognitive techniques with the aim of identifying and modifying unhelpful patterns of cognition (Newman 2003). Usually, behavioural components are included also; for PTSD, they generally encompass imaginal exposure (which creates a narrative of the trauma memory and engages in repeated exposure to it), and in vivo exposure (which involves gradual, repeated exposure to feared or avoided situations; Lewis 2012). Most Internet‐based self‐help programmes conclude with a section on relapse prevention that focuses on staying well, recognising signs of relapse, and offering advice on what to do if problems recur (Gega 2004).

Many different types of I‐C/BT have been developed; they can be distinguished on the basis of the level of therapist assistance provided. First, I‐C/BT can be delivered with regular assistance from a highly engaged specialist who provides input and feedback on homework, which acts as a direct analogue to specialty care. Second, I‐C/BT can be delivered by a non‐specialist mental health professional who briefly introduces the programme and briefly intervenes to check on progress, often by telephone or by e‐mail. Finally, I‐C/BT can adopt a pure self‐help approach, in which the participant is the sole agent of change, and no therapist assistance is provided.

How the intervention might work

Internet interventions may take a cognitive therapy (CT) or a behavioural therapy (BT) approach, but most are based on CBT (Andersson 2009). The core premise of CBT for PTSD is that fear conditioning and maladaptive cognitions contribute to emotional distress and problematic behaviours. Several disorder‐specific CBT protocols have been developed, and the approach involves a collaborative problem‐solving process, aimed at exploring and challenging unhelpful cognitions, and modifying problematic behaviours. Many I‐C/BT programmes for PTSD have taken a trauma‐focused CBT approach, which relies on general cognitive and behavioural techniques, with additional components aimed at addressing problematic thoughts and behaviours arising from the traumatic event itself.

Face‐to‐face trauma‐focused CBT is evidence based, and protocols draw on four core components: psychoeducation, anxiety management, exposure, and cognitive restructuring (Bisson 2013). These components are incorporated into Internet adaptations of the intervention (Lange 2003). Psychoeducation usually provides the starting point; anxiety management, exposure, and cognitive work are then gradually introduced (NCCMH 2005). Anxiety management techniques strengthen the individual's ability to cope with PTSD symptoms, recollection of traumatic memories, and the therapeutic process. Anxiety management may include breathing techniques, progressive muscle relaxation, or forms of guided imagery. Exposure plays an important role in many trauma‐focused CBT protocols and may be carried out in vivo (real life) or imaginally (Bryant 2003). It is common for both techniques to be used in the treatment of people with PTSD, to target internally and externally feared stimuli (Creamer 2004). The trauma memory itself is often the primary feared stimulus, and exposure to the memory is carried out imaginally. The rationale for the use of imaginal exposure varies according to the specific trauma‐focused CBT protocol applied. Imaginal exposure is based on principles of habituation (reduction of anxiety after prolonged exposure), information processing (re‐evaluation of old information and incorporation of new information into the trauma memory), or both (Foa 2008). In vivo exposure encourages the person to confront feared situations in real life, and cognitive work seeks to identify and modify unhelpful thoughts by testing and challenging self‐held beliefs (Foa 2007; Wilson 2012).

Why it is important to do this review

PTSD causes clinically significant distress and impacts functioning (APA 2013). Therefore, it is important to develop effective interventions. Several systematic reviews of interventions for PTSD have been published in the Cochrane Library. Bisson 2013 and Bradley 2005 described fairly robust evidence for trauma‐focused CBT and eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing (EMDR) as treatments for chronic PTSD, with emerging evidence for some non‐trauma‐focused CBT interventions and trauma‐focused CBT‐based group interventions. Other Cochrane reviews have considered single‐session psychological 'debriefing’ (Rose 2002), and multiple‐session early psychological interventions to prevent PTSD (Roberts 2009); and early psychological therapies (Roberts 2010), pharmacological treatments (Stein 2006), combined pharmacotherapy and psychological therapies (Hetrick 2010), and psychological therapies to treat PTSD in children and adolescents (Gillies 2012). Internet‐based self‐help represents an increasingly popular way of delivering psychological therapy, but its use for the treatment of people with PTSD has lagged behind that for other disorders (Lewis 2012). Internet‐based cognitive and behavioural therapies for depression and anxiety have received significant attention, and numerous systematic reviews and meta‐analyses have explored the efficacy of these interventions (e.g. Cuijpers 2008; Spek 2007). Positive findings, and the potential for these Internet‐based treatments to broaden access to psychological therapy and reduce costs, have spurred on the development and evaluation of similar interventions for a wide range of mental health problems. This has led to a proliferation of studies evaluating the efficacy of I‐C/BT for PTSD, deeming it a good time to conduct a Cochrane Review on this topic.

Two Cochrane Reviews are related to the current work, including the review of psychological therapies for PTSD, which did not include I‐C/BT treatments (Bisson 2013), and a review of media‐delivered CBT for anxiety disorders in adults, which excluded PTSD, as it was set to be separated from anxiety disorders in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM‐5), and the International Classification of Diseases, 11th Edition (ICD‐11; Mayo‐Wilson 2013). A third Cochrane Review of I‐C/BT for anxiety disorders included PTSD as an eligible diagnosis, but excluded interventions provided without therapist assistance, and interventions that included face‐to‐face therapist assistance; the stringent inclusion criteria resulted in inclusion of only one trial of I‐C/BT for PTSD (Olthuis 2015). Therefore, there still is the need to summarise the evidence base for I‐C/BT, which is unguided, or uses minimal face‐to‐face guidance.

Objectives

To assess the effects of I‐C/BT for PTSD in adults.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs), randomised cross‐over trials, and cluster‐randomised trials. We only used data from the first randomisation period of cross‐over trials to avoid a carry‐over effect. We did not use sample size or publication status to determine whether a study should be included. We included studies published in all languages.

Types of participants

Participant characteristics

Adults, 16 years of age or older. We did not consider I‐C/BT interventions for children under the age of 16 years for this review. We applied no restrictions on gender or ethnicity.

Diagnosis

Participants had traumatic stress symptoms, and at least 70% of people in any given study were required to meet diagnostic criteria for PTSD according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM‐III; APA 1980), DSM‐IIIR (APA 1987), DSM‐IV (APA 2000), DSM‐5 (APA 2013), International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD‐9; WHO 1979), or ICD‐10 (WHO 1992), assessed by clinical interview or a validated questionnaire. We included studies regardless of the index trauma, severity of symptoms, duration of symptoms, or length of time since trauma. We included studies of participants with PTSD as a comorbid disorder, as long as reduction in PTSD symptoms was the primary aim of the intervention. We placed no restriction on the basis or severity of PTSD symptoms or type of traumatic event.

Comorbidities

We applied no restrictions on the basis of comorbidity.

Setting

We applied no restrictions on the basis of setting.

Types of interventions

Experimental interventions

We included I‐C/BT interventions for the treatment of people with PTSD (with or without therapist guidance), including those delivered online and through native applications. We included programmes based on CT, BT, or CBT. These terms were defined as follows.

Interventions based on CT had to incorporate components that aimed to identify and modify unhelpful cognitions.

Interventions based on BT had to change behaviours associated with unhelpful cognitions or fear conditioning. This might have included exposure‐based work.

Interventions based on CBT must have included a combination of components based on CT and BT.

We drew a distinction between I‐C/BT and online psychoeducation, and did not include online psychoeducation.

To be classified as I‐C/BT, programmes had to be delivered via a computer or a mobile device. We included programmes that provided a maximum of five hours of therapist guidance, delivered face‐to‐face or remotely (e.g. telephone, e‐mail, instant messaging). We applied no restrictions based on the number of interactions with a therapist, or the length of the online programme.

We excluded interventions based on EMDR and interventions using mindfulness‐based approaches, apart from mindfulness‐based I‐C/BT.

Comparator interventions

Face‐to‐face psychological therapy (CBT‐based).

Face‐to‐face psychological therapy (non‐CBT‐based), categorised EMDR and other therapies (i.e. supportive therapy, non‐directive counselling, psychodynamic therapy, and present‐centred therapy) in line with the Cochrane Review of psychological therapies for adults with chronic PTSD (Bisson 2013).

Wait list, repeated assessment, or usual care.

Internet psychoeducation.

Internet psychological therapy (non‐CBT).

Types of outcome measures

We included studies that met the above inclusion criteria, regardless of whether they reported on the following outcomes.

Primary outcomes

Severity of PTSD symptoms (measured using a standardised scale, such as the Clinician‐Administered PTSD Symptom Scale (CAPS‐5; Blake 1995), or the PTSD Checklist (PCL‐5; Weathers 2013). When a study reported both a clinician‐administered scale and a self‐report measure, we used the clinician‐administered measure in the meta‐analysis).

Dropouts (measured by the number of participants still in treatment at the end of the intervention).

Secondary outcomes

Diagnosis of PTSD after treatment (number of participants who met diagnostic criteria for PTSD in each arm of the study).

Severity of depressive symptoms (using a standardised scale, e.g. Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck 1961)).

Severity of anxiety symptoms (using a standardised scale, e.g. Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI; Beck 1993)).

Cost‐effectiveness (any measures of cost‐effectiveness).

Adverse events (e.g. symptom worsening (taking into account the measurement error of the instrument), relapses to substance use, hospitalisations, suicide attempts, and work absenteeism).

Quality of life (any measures of quality of life).

Timing of outcome assessment

We grouped outcome measures according to length of follow‐up as follows.

Post‐treatment.

Follow‐up less than six months' post‐treatment.

Follow‐up between six months' and one year' post‐treatment.

Follow‐up longer than one year' post‐treatment.

Our primary outcome point was immediately post‐treatment.

Hierarchy of outcome measures

We produced hierarchies of standardised measures based on their frequency of use within included studies. When a trial reported data from two or more measures of the same outcome, we only used data from the measure ranked highest.

Search methods for identification of studies

Cochrane Common Mental Disorders Controlled Trials Register (CCMDCTR)

The Cochrane Common Mental Disorders Group maintains a specialised register of RCTs, the CCMDCTR. This register contains over 40,000 reference records (reports of RCTs) for anxiety disorders, depression, bipolar disorder, eating disorders, self‐harm, and other mental disorders within the scope of this Group. The CCMDCTR is a partially studies‐based register with more than 50% of reference records tagged to about 12,500 individually population, intervention, comparison, outcome (PICO)‐coded study records. Reports of trials for inclusion in the register are collated from (weekly) generic searches of Ovid MEDLINE (from 1950), Embase (from 1974), and PsycINFO (from 1967); quarterly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL); and review‐specific searches of additional databases. Reports of trials are also sourced from international trial registries, drug companies, handsearching of key journals, conference proceedings, and other (non‐Cochrane) systematic reviews and meta‐analyses. Details of CCMD's core search strategies (used to identify RCTs) can be found on the Group's website, with an example of the core MEDLINE search displayed in Appendix 1.

Electronic searches

The Cochrane Common Mental Disorders Group's Information Specialist ran initial searches on their specialised register (24 September 2015 and 6 May 2016) using the following search terms.

1. The CCMDCTR‐Studies Register: Condition = (PTSD or *trauma* or “acute stress” or “stress reaction”) AND Intervention = (computer* or internet or web* or online or self‐help or self‐manage* or self‐change)

2. The CCMDCTR‐References Register was searched using a more sensitive set of terms to identify additional untagged or uncoded reports of RCTs: #1. (PTSD or *trauma* or “combat disorder*” or “stress reaction” or “acute stress” or "stress disorder" or "war neurosis"):ab,ti,kw,ky,emt,mh,mc #2. (self near3 (care or change or guide* or help or intervention or manag* or support* or train*)):ab,ti,kw,ky,emt,mh,mc #3. (android or app or apps or audio* or blog or iCBT or cCBT or i‐CBT or c‐CBT or CD‐ROM or “cell phone” or cellphone or chat or computer* or cyber* or distance* or DVD or eHealth or e‐health or "electronic health*" or e‐Portal or ePortal or eTherap* or e‐therap* or forum* or gaming or “information technolog*” or "instant messag*" or internet* or interapy or ipad or i‐pad or iphone or i‐phone or ipod or i‐pod or web* or WWW or "smart phone" or smartphone or “mobile phone” or e‐mail* or email* or mHealth or m‐health or mobile or multi‐media or multimedia or online* or on‐line or “personal digital assistant” or PDA or SMS or "social medi*" or Facebook or software or telecomm* or telehealth* or telemed* or telemonitor* or telepsych*or teletherap* or "text messag*" or texting or tape or taped or video* or YouTube or podcast or virtual* or remote):ab,ti,kw,ky,emt,mh,mc #4. (#1 and (#2 or #3)) [Key to CRS field tags: ab:abstract; ti:title; kw:CRG keywords; ky:other keywords; emt:EMTREE headings; mh:MeSH headings; mc:MeSH checkwords]

3. The Information Specialist also ran a complementary search on PILOTS (Published International Literature on Traumatic Stress, US Department of Veterans Affairs), using relevant subject headings and search syntax appropriate to this resource (1990 to 24 November 2014 in the first instance; Appendix 2).

4. The searches were updated (1 March 2018), but as the Group's specialised register was out of date at the time, the information specialist ran searches directly on the following databases (Appendix 3):

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (Issue 2, 2018);

Ovid MEDLINE (2016 to 1 March 2018);

Ovid Embase (2016 to Week 9 2018);

Ovid PsycINFO (2016 to February week 4 2018);

ProQuest PILOTS (all years to 2 March 2018);

CCMDCTR (May to June 2016).

5. We searched international trial registries via the World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) and ClinicalTrials.gov to identify unpublished or ongoing studies (to March 2018).

We did not restrict the searches by date, language, or publication status.

Searching other resources

Grey literature

We searched sources of grey literature including dissertations and theses, clinical guidelines, and reports from regulatory agencies (when appropriate).

ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Database.

National Guideline Clearing House (guideline.gov/).

Worldwide Regulatory Agencies (www.globepharm.org/links/resource_agencies.html).

Open Grey (www.opengrey.eu/).

Reference lists

We scrutinised the reference lists of all included studies and relevant systematic reviews to identify additional missed studies. We also conducted a cited reference search on the Web of Science.

Correspondence

We contacted trialists and subject matter experts for information on unpublished or ongoing studies, and to request additional trial data.

Data collection and analysis

We followed guidance on data collection and analysis provided by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

Selection of studies

Two review authors (CL and AB) independently screened titles and abstracts of studies identified by the search, and coded them as 'retrieve' or 'do not retrieve'. We retrieved the full‐text publications of all potentially eligible studies, and the same two review authors independently screened and identified studies for inclusion. We recorded reasons for exclusion of ineligible studies. We resolved disagreements through discussion with a third review author (NR), and recorded the selection process in sufficient detail to complete a PRISMA flow diagram and Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Data extraction and management

We used a data extraction form that was piloted on one study in the review to extract study characteristics and outcome data.

Two review authors (CL and AB) independently extracted the following study characteristics and outcome data from included studies.

Methods: study design, duration of the study, study setting, withdrawals, year of the study.

Participants: number, mean age, age range, gender, primary trauma, time since trauma, severity of condition, diagnostic criteria, inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria, comorbidity, multiple traumas, trauma during childhood.

Interventions: intervention, number of hours of guidance, nature of guidance, training and qualifications of guiding therapists, amount of time spent on the programme, comparison, concomitant and excluded interventions, type of device.

Outcomes: primary and secondary outcomes specified and collected, time points reported.

Notes: funding for trial, notable conflicts of interest of trial authors (e.g. if they were involved in development of the intervention).

We noted in the Characteristics of included studies table if outcome data were not reported in a useable way. We resolved disagreements by consensus, or with involvement of a third review author (NR). One review author (CL) transferred data into Review Manager 5 (Review Manager 2014). We double‐checked data by comparing data presented in the systematic review with data provided in the study reports. A second review author (AB) spot‐checked study characteristics for accuracy against the trial report.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (CL and AB or LR) independently assessed the risk of bias for each study, using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions and listed below (Higgins 2011). We resolved conflicts through discussion with a third review author (NR).

Random sequence generation.

Allocation concealment.

Blinding of participants and personnel.

Blinding of outcome assessment.

Incomplete outcome data.

Selective outcome reporting.

Other bias (including baseline imbalances, early termination of the trial, researcher allegiance).

We judged each potential source of bias as high, low, or unclear, and provided a supporting quotation from the study report, together with a justification for the judgement, in the 'Risk of bias' table. We summarised risk of bias judgements across different studies for each of the domains listed. We considered blinding separately for different key outcomes when necessary. When information on risk of bias related to unpublished data or correspondence with a trialist, we noted this in the 'Risk of bias' table.

When considering treatment effects, we took into account risk of bias for studies that contributed to that outcome.

For cross‐over trials, we also took the following into account.

Suitability of the cross‐over design.

Possibility of carry‐over effects.

Whether only first period data were available.

Incorrect analysis.

Comparability of results with those from parallel‐group trials.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

We analysed dichotomous data as risk ratios (RR) to allow comparison across studies. We presented all outcomes with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Continuous data

We analysed continuous data as mean differences (MDs) or standardised mean differences (SMDs), to allow comparison across studies. We calculated MDs when all studies within a meta‐analysis used the same outcome measure, and SMDs when studies used different measures. We entered data presented on a scale with a consistent direction of effect. We presented all outcomes using 95% CIs, and undertook meta‐analyses only when it was meaningful to do so (i.e. when treatments, participants, and the underlying clinical question were sufficiently similar). We planned to describe skewed data reported as medians and interquartile ranges in a narrative, and when multiple trial arms were reported in a single trial, we planned to include only the relevant arms.

Clinical significance was assessed by taking into account the size of a treatment effect, the severity of the condition being treated, and the adverse effects of the treatment.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐randomised trials

We decided that, when necessary, we would adjust sample sizes, using an estimate of the intracluster or intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC), which describes the similarity of participants within the same cluster. We planned to derive this from the trial if possible, or from another source, such as a similar study, or from a resource providing examples of ICCs, if data were not available in the trial report.

Cross‐over trials

When a study adopted a cross‐over design, we planned to only include outcome data from the first randomisation period, to avoid a carry‐over effect.

Studies with multiple treatment groups

We planned to undertake pair‐wise meta‐analysis with each arm, depending on the nature of the intervention in each arm and its relevance to the review objectives. We aimed to avoid multiple comparisons to limit the risk of false‐positive results. If a study included three or more arms that were relevant to the review, we planned to assess the appropriateness of combining data from two arms if therapies were sufficiently similar, or of using data from the arms of the trial that fit most closely with the review objectives. For studies with multiple treatments arms, some of which are relevant to the review, we still listed the treatment arms in the Characteristics of included studies table. Decisions would follow guidance provided by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

Dealing with missing data

We contacted investigators to verify key study characteristics, and to request missing outcome data. We documented all correspondence with trialists, and reported which trialists responded. The protocol described the use of imputation of missing data; however, only published data were presented in the review. Should we find incidents of inadequate reporting of data in future updates of this review, we will attempt to impute missing data from other available information, in line with guidance provided by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed studies included in each comparison for clinical heterogeneity in terms of variability in experimental and comparator interventions, participants, settings, and outcomes. To further assess heterogeneity, we used both the I² statistic and the Chi² test of heterogeneity, and visually inspected the forest plots. We used the following scale suggested by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions as a guide to interpretation of the I² statistic (Higgins 2011).

0% to 40%: might not be important.

30% to 60%: may represent moderate heterogeneity.

50% to 90%: may represent substantial heterogeneity.

75% to 100%: shows considerable heterogeneity.

The I² statistic was interpreted with consideration of the size and direction of effects, as well as the strength of evidence for heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

We specified that if sufficient studies were available in a meta‐analysis (10 or more), we would prepare funnel plots and examine these for signs of asymmetry. We specified that if asymmetry was identified, we would consider other possible reasons for this.

Data synthesis

We pooled data from more than one study when appropriate. We performed random‐effects meta‐analyses as the main analyses as substantial heterogeneity between trials was anticipated. We conducted fixed‐effect analyses as sensitivity analyses to informally compare the results. When studies could not be combined, we summarised them in a narrative.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We specified that we would consider the following possible causes of clinical heterogeneity for exploration, if sufficient data allowed.

Therapist assistance (e.g. Internet‐based interventions delivered with guidance, Internet‐based interventions delivered without guidance), as this varies substantially between interventions and may impact trial results.

Type of therapist assistance (e.g. guidance face‐to‐face, by telephone, by video conference, by e‐mail, by instant messaging).

Participant subgroups (e.g. veterans, female victims of sexual abuse, police officers), as some subgroups are more difficult to treat than others, and may be more or less suited to an online approach to treatment.

Type of recruitment (e.g. from media adverts only, from healthcare services only), as this may influence motivation and symptom severity of trial participants.

Type of CBT (e.g. predominantly CT, predominantly BT, CBT), as this may vary, and may include an efficacy outcome.

Baseline symptom severity (e.g. high versus low baseline mean symptom severity), on the basis that I‐C/BT is commonly thought to be better suited to people with milder symptoms.

Trauma type and context (e.g. war, childhood abuse, motor vehicle accident), on the basis that I‐C/BT is commonly thought to be better suited to people with less complex trauma histories.

Trauma focus (e.g. trauma‐focused versus non‐trauma‐focused I‐C/BT), as findings from the wider PTSD literature support trauma‐focused interventions as most effective.

Type of device (e.g. computer, smartphone), as availability on a smartphone is thought to improve outcomes.

We intended to keep subgroup analyses to a minimum to avoid issues related to multiple testing, and to only conduct these analyses on primary outcome measures.

Sensitivity analysis

We specified that we would consider sensitivity analysis to explore possible causes of methodological heterogeneity, if sufficient data allowed. We would base analyses on the following criteria.

Sequence generation.

Allocation concealment.

Blinding of outcome assessment.

Method of diagnosis (e.g. clinician diagnosis, structured interview, screening tool or questionnaire).

We planned to conduct these analyses for primary outcomes by removing studies with high or unknown risk of bias for these domains.

'Summary of findings' tables

We evaluated the quality of available evidence using the GRADE approach. We generated 'Summary of findings' tables using GRADEpro GDT software, which imports data from Review Manager 5 (GRADEpro GDT; Review Manager 2014). These tables provided outcome‐specific information concerning the overall quality of evidence from studies included in the comparison, the magnitude of effect of the interventions examined, and the sum of available data on outcomes considered. We included information on the first seven outcomes of our review: severity of PTSD symptoms post‐treatment, dropouts, diagnosis of PTSD after treatment, severity of depressive symptoms, severity of anxiety symptoms, cost‐effectiveness, and adverse events. We assessed the quality of evidence using five factors.

Limitations in study design and implementation of available studies.

Indirectness of evidence.

Unexplained heterogeneity or inconsistency of results.

Imprecision of effect estimates.

Potential publication bias.

For each outcome, we classified the quality of evidence according to the following categories.

High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect.

Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect, and may change the estimate.

Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect, and is likely to change the estimate.

Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate.

We downgraded the evidence from high quality by one level for serious (or by two for very serious) study limitations (risk of bias), indirectness of evidence, serious inconsistency, imprecision of effect estimates, or potential publication bias. 'Summary of findings' tables included primary outcome measures and post‐treatment outcomes.

Results

Description of studies

See Characteristics of included studies table.

Results of the search

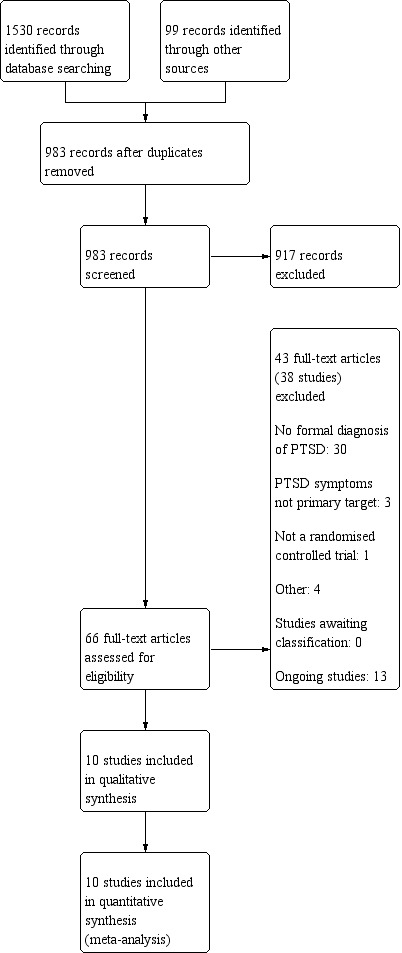

The initial searches identified 669 potentially relevant studies for consideration, plus 99 studies from other sources. After removing duplicates, we were left with 481 reports. We excluded 435 after assessing titles and abstracts. We obtained full‐text papers for the remaining 46; after full inspection, we identified four that met the inclusion criteria and were included in the final qualitative and quantitative analyses (Ivarsson 2014; Lewis 2017; Litz 2007; Spence 2011),

An update search (1 March 2018) identified a further 861 records and after the Information Specialist removed 359 duplicate records and 161 reports of uncontrolled trials, left 341 records to screen. After we assessed the abstracts and relevant full‐text, we identified four additional studies that met inclusion criteria (Krupnick 2017; Kuhn 2017; Littleton 2016; Miner 2016). These have been included in the final qualitative and quantitative analyses together with two studies which were previously awaiting classification (Engel 2015; Knaevelsrud 2015).

We excluded 38 studies (see Characteristics of excluded studies table).

We identified 13 ongoing studies (see Characteristics of ongoing studies table).

The process of study selection is illustrated in the PRISMA diagram in Figure 1.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

The review included 10 RCTs of 720 participants.

Design

All of the included studies were RCTs. All studies randomly assigned participants, as opposed to clinics or practices.

Sample sizes

The studies had sample sizes of 80 (I‐C/BT 43; optimised usual care 37; Engel 2015); 62 (I‐C/BT 31; delayed treatment 31; Ivarsson 2014); 159 (I‐C/BT 79; wait list 80; Knaevelsrud 2015); 31 (I‐C/BT 16; treatment as usual 15; Krupnick 2017); 120 (I‐C/BT 62; wait list 58; Kuhn 2017); 42 (I‐C/BT 21; wait list 21; Lewis 2017); 87 (I‐C/BT 46; supportive counselling 41; Littleton 2016); 45 (I‐C/BT 24; supportive counselling 21; Litz 2007); 49 (I‐C/BT 25; wait list 24; Miner 2016), and 42 (I‐C/BT 21; wait list 21; Spence 2011).

Setting

Six studies were conducted in the US (Engel 2015; Krupnick 2017; Kuhn 2017; Littleton 2016; Litz 2007; Miner 2016), one in Sweden (Ivarsson 2014), one in Australia (Spence 2011), one in the UK (Lewis 2017), and one in Iraq (Knaevelsrud 2015).

Participants

One included participants who met criteria for DSM‐5 PTSD (Lewis 2017); the other nine studies included participants who met criteria for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual 4th Edition (DSM‐IV) PTSD (Engel 2015; Ivarsson 2014; Knaevelsrud 2015; Krupnick 2017; Kuhn 2017; Littleton 2016; Litz 2007; Miner 2016; Spence 2011). One study included only military personnel traumatised after combat exposure in Afghanistan or Iraq, or the 9/11 attacks on the Pentagon (Litz 2007); one study included only female rape victims (Littleton 2016), and the remainder included participants traumatised after a variety of traumatic events that met DSM criteria. See Characteristics of included studies table for further details. Where reported, the percentage of women in studies ranged from 18.75% to 100%; the percentage of participants with a university education ranged from 14.2% to 62.8%; and the percentage of participants who were unemployed ranged from 8.1% to 40%.

Interventions

Eight studies compared an Internet programme based on trauma‐focused CBT with a wait list, treatment as usual, or delayed treatment control group (Engel 2015; Ivarsson 2014; Knaevelsrud 2015; Krupnick 2017; Kuhn 2017; Lewis 2017; Miner 2016; Spence 2011). Treatment durations were four weeks (Miner 2016), five weeks (Knaevelsrud 2015), six weeks (Engel 2015), eight weeks (Ivarsson 2014; Lewis 2017; Spence 2011), 10 sessions (Krupnick 2017) and 12 weeks (Kuhn 2017).

Two studies compared an Internet programme based on trauma‐focused CBT with Internet psychological therapy (non‐CBT) (Littleton 2016; Litz 2007). In the Litz 2007 study, the duration of treatment was eight weeks, while in the study by Littleton 2016, treatment was for 14 weeks. A therapist guided all of the Internet interventions. See Characteristics of included studies table for further details.

Outcomes

Symptoms of PTSD were measured using the Impact of Event Scale (IES‐R), the Clinician‐Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS‐5), the PTSD Checklist – Civilian Version (PCL‐C), the PTSD Symptom Scale – Interview (PSS‐I), and the Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale (PDS). Depression was measured using the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ‐7, PHQ‐8, PHQ‐9, PHQ‐15), and the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES‐D). Anxiety was measured using the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7‐Item Scale (GAD‐7). Quality of life was measured using the Quality of Life Inventory (QOLI) and EUROHIS‐QUOL.

Excluded studies

For details of the 38 excluded studies, see the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Ongoing studies

For details of the 13 ongoing studies, see the Characteristics of ongoing studies table.

Studies awaiting classification

There are no studies awaiting classification.

Risk of bias in included studies

For details of the risk of bias judgements for each study, see the Characteristics of included studies table. A graphical representation of the overall risk of bias in included studies is presented in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

2.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias domain presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias domain for each included study.

For cluster‐randomised trials, we planned to take the following into account.

Recruitment bias (e.g. if participants had been recruited to the trial after clusters were randomly assigned).

Baseline imbalance.

Loss of clusters.

Incorrect analysis.

Comparability with individual randomised trial

Allocation

Seven of the included studies provided sufficient information to determine that there was a low risk of bias associated with sequence generation (Engel 2015; Ivarsson 2014; Knaevelsrud 2015; Kuhn 2017; Lewis 2017; Littleton 2016; Spence 2011), while three studies did not provide information to make a judgement (Krupnick 2017; Litz 2007; Miner 2016). One study reported the use of sealed, opaque envelopes to conceal the allocation of treatment and was judged at low risk of selection bias (Lewis 2017). The remaining nine studies did not provide information to make a judgement on allocation concealment and were therefore classified at unclear risk of selection bias (Engel 2015; Ivarsson 2014; Knaevelsrud 2015; Krupnick 2017; Kuhn 2017; Littleton 2016; Litz 2007; Spence 2011).

Blinding

It is impossible to blind the participants and therapists in psychological treatment trials and, therefore, all 10 studies were at high risk of performance bias.

Eight studies reported adequate blinding of the outcome assessor (Engel 2015; Ivarsson 2014; Knaevelsrud 2015; Krupnick 2017; Kuhn 2017; Lewis 2017; Litz 2007; Miner 2016). The two remaining studies reported that outcome assessors were not blinded to treatment and were, therefore, at high risk of detection bias (Littleton 2016; Spence 2011).

Incomplete outcome data

Six of the included studies dealt with missing outcome data appropriately and were judged to be at low risk of attrition bias (Engel 2015; Ivarsson 2014; Kuhn 2017; Lewis 2017; Littleton 2016; Miner 2016). Four studies were at high risk of attrition bias (Knaevelsrud 2015; Krupnick 2017; Litz 2007; Spence 2011). One study completed intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis but missing data were more than 30% (Knaevelsrud 2015). One study had a dropout rate of over 75% and did not fully report reasons for dropout (Krupnick 2017). One study reported completer data only, but performed ITT analyses (Litz 2007). One study used the last outcome carried forward method to impute missing data (Spence 2011). Reasons for dropout were poorly described.

Selective reporting

Only one of the included studies published the study protocol (Knaevelsrud 2015). Of the nine remaining included studies, although the study protocol was not available, it was clear that the published reports included the outcomes PTSD, depression, and anxiety, that were prespecified and expected in trials of this type in the field of PTSD. Therefore, these nine studies were judged at low risk of reporting bias (Engel 2015; Ivarsson 2014; Krupnick 2017; Kuhn 2017; Lewis 2017; Littleton 2016; Litz 2007; Miner 2016; Spence 2011).

Other potential sources of bias

Five studies were at low risk of other bias (Engel 2015; Knaevelsrud 2015; Kuhn 2017; Littleton 2016; Miner 2016). Four studies were at high risk of bias (Ivarsson 2014; Krupnick 2017; Lewis 2017; Litz 2007). We could not rule out potential researcher allegiance, since three included trials were of interventions that were evaluated by their originators (Ivarsson 2014; Lewis 2017; Litz 2007). Sample sizes in three studies were small (Krupnick 2017; Lewis 2017; Litz 2007), and follow‐up was very limited in one study (Litz 2007). For practical and ethical reasons, longer‐term follow‐up data were not available from the wait list groups. One study was at unclear risk of bias as it terminated recruitment prematurely, and failed to recruit the prespecified number of participants (Spence 2011).

Effects of interventions

Summary of findings 1. Internet‐based cognitive and behavioural therapy (I‐C/BT) compared to wait list for post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults.

| I‐C/BT compared to wait list for PTSD in adults | ||||||

| Patient or population: adults with PTSD Setting: Intervention: I‐C/BT Comparison: wait list | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with wait list | Risk with I‐C/BT | |||||

|

Severity of PTSD symptoms (measured with the IES‐R, CAPS‐5, PCL‐CPSS‐I and PDS; higher score = worse outcome) Follow‐up: post‐treatment |

The mean severity of PTSD symptoms (post‐treatment) was 0 | SMD 0.6 lower (0.97 lower to 0.24 lower) | — | 560 (8 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b | — |

| Dropouts | Study population | RR 1.39 (1.03 to 1.88) | 585 (8 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa | — | |

| 186 per 1000 | 258 per 1000 (192 to 350) | |||||

| Diagnosis of PTSD after treatment | Study population | RR 0.53 (0.28 to 1.00) | 62 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowc,d | — | |

| 548 per 1000 | 291 per 1000 (154 to 548) | |||||

|

Severity of depressive symptoms (measured with the BDI, PHQ and CES‐D; higher score = worse outcome) Follow‐up: post‐treatment |

The mean depression (post‐treatment) was 0 | SMD 0.61 lower (1.17 lower to 0.05 lower) | — | 425 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowb,e | — |

|

Severity of anxiety symptoms (measured with the BAI and GAD‐7; higher score = worse outcome) Follow‐up: post‐treatment |

The mean anxiety (post‐treatment) was 0 | SMD 0.67 lower (0.98 lower to 0.36 lower) | — | 305 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowf,g | — |

| Cost‐effectiveness | — | — | — | — | — | Not measured |

| Adverse events | — | — | — | — | — | Not measured |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). BAI: Beck Anxiety Inventory; BDI: Beck Depression Inventory; CAPS‐5: Clinician‐Administered PTSD Symptom Scale; CES‐D: Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; CI: confidence interval; GAD‐7: Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7‐Item Scale; I‐C/BT: Internet‐based cognitive and behavioural therapy; IES‐R: Impact of Event Scale; PCL‐CPSS‐I: PTSD Checklist‐Child Posttraumatic Stress Scale – Interview for DSM‐5; PDS: Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale; PHQ: Patient Health Questionnaire; PTSD: post‐traumatic stress disorder;RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio; SMD: standardised mean difference. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded two levels due to high risk of performance bias in all eight studies, high risk of attrition bias in two studies (Knaevelsrud 2015; Krupnick 2017), and high risk of other bias in three studies (Ivarsson 2014; Krupnick 2017; Lewis 2017).

bDowngraded one level for inconsistency; high levels of heterogeneity.

cDowngraded one level for imprecision due to small sample size and the CI around the effect estimate includes both little or no effect.

dDowngraded two levels due high risk of performance bias and other bias (Ivarsson 2014).

eDowngraded two levels due to high risk of performance bias in all five studies, high risk of attrition bias in one study (Krupnick 2017), and high risk of other bias in two studies (Krupnick 2017; Lewis 2017).

fDowngraded one level for imprecision due to small sample size.

gDowngraded two levels due to high risk or performance bias in all four studies, high risk of attrition bias in one study (Knaevelsrud 2015), and high risk of other bias in two studies (Lewis 2017; Spence 2011).

Summary of findings 2. Internet‐based cognitive and behavioural therapy (I‐C/BT) compared to I‐non‐C/BT for post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults.

| I‐C/BT compared to I‐non‐C/BT for post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults | ||||||

| Patient or population: adults with PTSD Setting: Intervention: I‐C/BT Comparison: I‐non‐C/BT | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with I‐non‐C/BT | Risk with I‐C/BT | |||||

|

Severity of PTSD symptoms (measured with the IES‐R, CAPS‐5, PCL‐CPSS‐I and PDS; higher score = worse outcome) Follow‐up: post‐treatment |

The mean severity of PTSD symptoms (post‐treatment) was 0 | SMD 0.08 lower (0.52 lower to 0.35 higher) | — | 82 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b | — |

| Dropouts | Study population | RR 2.14 (0.97 to 4.73) | 132 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b | — | |

| 113 per 1000 | 242 per 1000 (110 to 534) | |||||

| Diagnosis of PTSD after treatment | — | — | — | — | — | — |

|

Severity of depressive symptoms (measured with the BDI, PHQ and CED‐D; higher score = worse outcome) Follow‐up: post‐treatment |

The mean depression (post‐treatment) was 0 | SMD 0.12 lower (0.78 lower to 0.54 higher) | — | 84 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b | — |

|

Severity of anxiety symptoms (measured with the BAI and GAD‐7; higher score = worse outcome) Follow‐up: post‐treatment |

The mean anxiety (post‐treatment) was 0 | SMD 0.08 higher (0.78 lower to 0.95 higher) | — | 74 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b,c | — |

| Cost‐effectiveness | — | — | — | — | — | Not measured |

| Adverse events | — | — | — | — | — | Not measured |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). BAI: Beck Anxiety Inventory; BDI: Beck Depression Inventory; CAPS‐5: Clinician‐Administered PTSD Symptom Scale; CES‐D: Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; CI: confidence interval; GAD‐7: Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7‐Item Scale; I‐C/BT: Internet‐based cognitive and behavioural therapy; IES‐R: Impact of Event Scale; PCL‐CPSS‐I: PTSD Checklist‐Child Posttraumatic Stress Scale – Interview for DSM‐5; PDS: Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale; PHQ: Patient Health Questionnaire; PTSD: post‐traumatic stress disorder;RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio; SMD: standardised mean difference. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded two levels due to high risk of performance bias due to lack of blinding participants and personnel in both studies (Littleton 2016; Litz 2007), high risk of detection bias due to lack of blinding outcome assessors in one study (Littleton 2016), and high risk of attrition bias and other bias in one study (Litz 2007).

bDowngraded two levels for imprecision due to small sample size and the CI of the effect estimate includes both little or no effect.

cDowngraded one level for inconsistency due to high levels of heterogeneity.

Comparison 1: Internet‐based cognitive and behavioural therapies versus face‐to‐face cognitive behavioural therapy

None of the included studies compared I‐C/BT versus face‐to‐face CBT.

Comparison 2: Internet‐based cognitive and behavioural therapies versus face‐to‐face non‐cognitive behavioural therapy

None of the included studies compared I‐C/BT versus face‐to‐face non‐CBT.

Comparison 3: Internet‐based cognitive and behavioural therapies versus wait list or usual care

Eight studies including 560 participants compared I‐C/BT versus wait list or usual care (Engel 2015; Ivarsson 2014; Knaevelsrud 2015; Krupnick 2017; Kuhn 2017; Lewis 2017; Miner 2016; Spence 2011). See Table 1.

Primary outcomes

3.1. Severity of post‐traumatic stress disorder symptoms

There was very low‐quality evidence that I‐C/BT was more effective than wait list when the severity of PTSD symptoms were measured post‐treatment (SMD –0.60, 95% CI –0.97 to –0.24; participants = 560; studies = 8; Analysis 1.1). There was considerable heterogeneity in study results (I² = 76%). When duration of follow‐up was less than six months, there was no evidence of a difference between I‐C/BT and wait list groups (SMD –0.43, 95% CI –1.41 to 0.56; studies = 3; participants = 146; Analysis 1.2).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Internet‐based cognitive and behavioural therapy (I‐C/BT) versus wait list (WL), Outcome 1: Severity of PTSD symptoms (post‐treatment)

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Internet‐based cognitive and behavioural therapy (I‐C/BT) versus wait list (WL), Outcome 2: Severity of PTSD symptoms (follow‐up < 6 months)

3.2. Dropouts

There was low‐quality evidence of a significant difference in dropout rates from the I‐C/BT and wait list groups (RR 1.39, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.88; studies = 8; participants = 585; I² = 13%; Analysis 1.3).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Internet‐based cognitive and behavioural therapy (I‐C/BT) versus wait list (WL), Outcome 3: Dropouts

Secondary outcomes

3.3. Diagnosis of post‐traumatic stress disorder after treatment

There was very low‐quality evidence that I‐C/BT was no more effective than wait list at reducing the risk of a diagnosis of PTSD after treatment (RR 0.53, 95% CI 0.28 to 1.00; participants = 62; studies = 1; Analysis 1.4).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Internet‐based cognitive and behavioural therapy (I‐C/BT) versus wait list (WL), Outcome 4: Diagnosis of PTSD after treatment

3.4. Severity of depressive symptoms

There was very low‐quality evidence that I‐C/BT was more effective than wait list at reducing the severity of depressive symptoms (SMD –0.61, 95% CI –1.17 to –0.05; participants = 425; studies = 5; Analysis 1.5). There was considerable heterogeneity in study results (I² = 86%). There was very low‐quality evidence that I‐C/BT was still more effective than wait list at follow‐up less than six months (MD –8.95, 95% CI –15.57 to –2.33; participants = 42; studies = 1; Analysis 1.6).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Internet‐based cognitive and behavioural therapy (I‐C/BT) versus wait list (WL), Outcome 5: Severity of depression (post‐treatment)

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Internet‐based cognitive and behavioural therapy (I‐C/BT) versus wait list (WL), Outcome 6: Severity of depression (follow‐up < 6 months)

3.5. Severity of anxiety symptoms

There was very low‐quality evidence that I‐C/BT was more effective than wait list at reducing symptoms of anxiety (SMD –0.67, 95% CI –0.98 to –0.36; participants = 305; studies = 4; I² = 35%; Analysis 1.7). There was very low‐quality evidence that I‐C/BT was still more effective than wait list at follow‐up less than six months (MD –12.59, 95% CI –20.74 to –4.44; participants = 42; studies = 1; Analysis 1.8).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Internet‐based cognitive and behavioural therapy (I‐C/BT) versus wait list (WL), Outcome 7: Severity of anxiety symptoms (post‐treatment)

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Internet‐based cognitive and behavioural therapy (I‐C/BT) versus wait list (WL), Outcome 8: Severity of anxiety symptoms (follow‐up < 6 months)

3.6. Cost‐effectiveness

None of the included studies comparing I‐C/BT to wait list or usual care reported cost‐effectiveness.

3.7. Adverse events

None of the included studies comparing I‐C/BT to wait list or usual care reported adverse events.

3.8. Quality of life

There was very low‐quality evidence of no significant difference between the I‐C/BT and wait list groups for quality of life (SMD 0.60, 95% CI 0.08 to 1.12; participants = 221; studies = 2; Analysis 1.9). There was substantial heterogeneity in study results (I² = 68%).

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Internet‐based cognitive and behavioural therapy (I‐C/BT) versus wait list (WL), Outcome 9: Quality of Life (post‐treatment)

Comparison 4: Internet‐based cognitive and behavioural therapies versus Internet psychoeducation

None of the included studies compared I‐C/BT versus Internet psychoeducation.

Comparison 5: Internet‐based cognitive and behavioural therapies versus Internet‐based non‐cognitive and behavioural therapies

Two studies including 82 participants compared I‐C/BT versus Internet‐based non‐cognitive and behavioural therapies (I‐non‐C/BT) (Littleton 2016; Litz 2007). See Table 2.

5.1. Severity of post‐traumatic stress disorder symptoms

There was very low‐quality evidence of no significant difference between the I‐C/BT and I‐non‐C/BT groups in the post‐treatment severity of PTSD symptoms (SMD –0.08, 95% CI –0.52 to 0.35; participants = 82; studies = 2; I² = 19%; Analysis 2.1), or at follow‐up less than six months (SMD 0.08, 95% CI –0.41 to 0.57; participants = 65; studies = 2; I² = 0%; Analysis 2.2). However, there was a significant difference in favour of I‐C/BT at follow‐up of six to 12 months (MD –8.83, 95% CI –17.32 to –0.34; participants = 18; studies = 1; Analysis 2.3).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Internet‐based cognitive and behavioural therapy (I‐C/BT) versus I‐non‐C/BT, Outcome 1: Severity of PTSD symptoms (post‐treatment)

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Internet‐based cognitive and behavioural therapy (I‐C/BT) versus I‐non‐C/BT, Outcome 2: Severity of PTSD symptoms (follow‐up < 6 months)

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Internet‐based cognitive and behavioural therapy (I‐C/BT) versus I‐non‐C/BT, Outcome 3: Severity of PTSD symptoms (follow‐up 6–12 months)

5.2. Dropouts

There was very low‐quality evidence of no significant difference between dropout rates from the I‐C/BT and I‐non‐C/BT (RR 2.14, 95% CI 0.97 to 4.73; participants = 132; studies = 2; I² = 0%; Analysis 2.4).

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Internet‐based cognitive and behavioural therapy (I‐C/BT) versus I‐non‐C/BT, Outcome 4: Dropouts

Secondary outcomes

5.3. Diagnosis of post‐traumatic stress disorder after treatment

Neither study comparing I‐C/BT versus I‐non‐C/BT reported on diagnosis of PTSD after treatment.

5.4. Severity of depressive symptoms

There was very low‐quality evidence of no significant difference in severity of depressive symptoms between the I‐C/BT and I‐non‐C/BT groups post treatment (SMD –0.12, 95% CI –0.78 to 0.54; participants = 84; studies = 2; I² = 52%; Analysis 2.5) or when follow‐up was less than six months (SMD 0.20, 95% CI –0.31 to 0.71; participants = 61; studies = 2; I² = 0%; Analysis 2.6). However, there was very low‐quality evidence of a difference in severity of depressive symptoms between the I‐C/BT and I‐non‐C/BT groups when follow‐up was six to 12 months (MD –8.34, 95% CI –15.83 to –0.85; participants = 18; studies = 1; Analysis 2.7).

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Internet‐based cognitive and behavioural therapy (I‐C/BT) versus I‐non‐C/BT, Outcome 5: Severity of depressive symptoms (post‐treatment)

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Internet‐based cognitive and behavioural therapy (I‐C/BT) versus I‐non‐C/BT, Outcome 6: Severity of depressive symptoms (follow‐up < 6 months)

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Internet‐based cognitive and behavioural therapy (I‐C/BT) versus I‐non‐C/BT, Outcome 7: Severity of depressive symptoms (follow‐up 6–12 months)

5.5. Severity of anxiety symptoms

There was very low‐quality evidence of no significant difference in severity of symptoms of anxiety between the I‐C/BT and I‐non‐C/BT groups (SMD 0.08, 95% CI –0.78 to 0.95; participants = 74; studies = 2; I² = 70%; Analysis 2.8) or when follow‐up was less than six months (SMD –0.16, 95% CI –0.67 to 0.35; participants = 60; studies = 2; I² = 9%; Analysis 2.9). However, there was very low‐quality evidence of a difference in severity of anxiety symptoms between the I‐C/BT and I‐non‐C/BT groups when follow‐up was six to 12 months (MD –8.05, 95% CI –15.20 to –0.90; participants = 18; studies = 1; Analysis 2.10).

2.8. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Internet‐based cognitive and behavioural therapy (I‐C/BT) versus I‐non‐C/BT, Outcome 8: Severity of anxiety symptoms (post‐treatment)

2.9. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Internet‐based cognitive and behavioural therapy (I‐C/BT) versus I‐non‐C/BT, Outcome 9: Severity of anxiety symptoms (follow‐up < 6 months)

2.10. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Internet‐based cognitive and behavioural therapy (I‐C/BT) versus I‐non‐C/BT, Outcome 10: Severity of anxiety symptoms (follow‐up 6–12 months)

5.6. Cost‐effectiveness

Neither study comparing I‐C/BT versus I‐non‐C/BT reported cost‐effectiveness.

5.7. Adverse events

Neither study comparing I‐C/BT versus I‐non‐C/BT reported adverse effects.

5.8. Quality of life

Neither study comparing I‐C/BT versus I‐non‐C/BT reported quality of life.

Subgroup analyses

There were insufficient data to perform subgroup analyses on the effect of therapist assistance; type of therapist assistance; participant subgroups; type of recruitment; type of CBT; baseline symptom severity; trauma type and context; trauma focus; or type of device.

Sensitivity analyses

We could not conduct sensitivity analyses because none of the comparisons included more than 10 studies.

Discussion

Summary of main results

The review included 10 studies with 720 participants (see Table 1; Table 2). Eight of the studies compared I‐C/BT delivered with therapist guidance to a wait‐list control group. Two studies compared guided I‐C/BT with I‐non‐C/BT.

Therapist‐guided I‐C/BT may have been more effective than a wait list in reducing PTSD symptoms, depression, and anxiety post‐treatment. However, there was no significant difference between the two groups on measures of quality of life. The magnitude of effect was smaller than that found in comparisons of therapist‐administered trauma‐focused CBT with wait list or usual care (Bisson 2013). This may indicate that while beneficial, this is a less effective form of treatment. There was a significant difference in dropout rates between groups, with a greater number leaving I‐C/BT than wait list/usual care.

There was no significant difference between therapist‐guided I‐C/BT and I‐non‐C/BT on any measure post‐treatment. Only two small studies made this comparison; they showed that I‐C/BT was no more effective in reducing severity of PTSD symptoms, anxiety, and depression at 12‐month follow‐up. There was no significant difference in dropout rates between groups.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The field of I‐C/BT for PTSD is in its infancy, and this review considered the limited number of studies currently available. Drawing together the results of these studies provided an indication of the effectiveness of I‐C/BT. However, the small number of studies contributing to each comparison limited our ability to comprehensively answer the questions that we set out to address. Indeed, we were unable to answer many of the questions set out by the review. For example, we were unable to draw any conclusions related to cost‐effectiveness. We were also unable to compare the efficacy of I‐C/BT with face‐to‐face psychological therapy or the provision of education. This indicates a need for further research, and an update of the review once further studies have been completed.

Eligible RCTs included adults who had been exposed to a variety of traumatic events (see Types of participants). We included all studies in which at least 70% of participants had been diagnosed with PTSD. We excluded studies that evaluated I‐C/BT in participants with subthreshold PTSD symptoms, or traumatised people who were not formally diagnosed as having PTSD (see Characteristics of excluded studies table). This approach is in keeping with the Cochrane Review of therapist‐administered psychological therapies for PTSD, and the aim was to ensure the empirical validity of the review (Bisson 2013). However, this did result in the exclusion of studies that would have contributed additional data.

The included studies were conducted in Sweden, the UK, the USA, Iraq, and Australia, which limits generalisability of results to the rest of the world, especially to low‐ and middle‐income countries. The studies did not include participants with comorbidities of substance dependence, psychosis, and severe depression, therefore, excluding people who are arguably more difficult to treat. That said, it is possible that I‐C/BT may be most appropriate for people with mild‐to‐moderate PTSD, in a stepped or stratified pathway of care. Participants included in the 10 studies were predominantly white, employed, and had relatively high levels of education. Therefore, it is not possible to determine whether similar results would have been obtained from participants with more representative demographic characteristics.

Eight of the 10 included studies compared I‐C/BT to a wait list or delayed treatment control group. The search identified no studies that compared I‐C/BT to psychological therapy delivered face‐to‐face (CBT‐based or non‐CBT‐based), or to Internet‐based psychoeducation. Therefore, we were unable to draw any conclusions related to these comparisons. All studies included some level of guidance, which precluded comparison of guided and unguided interventions. None of the eligible studies included data on cost effectiveness, so we were unable to comment on whether these interventions hold promise from an economic standpoint, although clearly, they would have cost less to deliver than face‐to‐face therapy, given the reduced contact time with therapists. Despite high levels of dropout from the included studies, the reasons given for this were poorly described, which precluded indepth consideration related to the tolerability of interventions.

As is common in studies of psychological therapies, concurrent pharmacotherapy was permissible. This caused issues disentangling the effects of medication versus the therapy being trialled. This is largely unavoidable, due to ethical considerations, and all studies stipulated that dosage had been constant for a stipulated duration. Although concurrent psychological therapy was an exclusion criterion for the included studies, methods of formally evaluating whether additional treatment had been sought were not described. Indeed, one study gave the possibility of participants in the control group having engaged in psychological therapy during the study period as a possible explanation for a failure to find between group differences, despite large within‐group differences in the treatment group (Spence 2011).