Abstract

Background

This is the first update of a Cochrane Review first published in 2015. Renin angiotensin system (RAS) inhibitors include angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) and renin inhibitors. They are widely prescribed for treatment of hypertension, especially for people with diabetes because of postulated advantages for reducing diabetic nephropathy and cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Despite widespread use for hypertension, the efficacy and safety of RAS inhibitors compared to other antihypertensive drug classes remains unclear.

Objectives

To evaluate the benefits and harms of first‐line RAS inhibitors compared to other first‐line antihypertensive drugs in people with hypertension.

Search methods

The Cochrane Hypertension Group Information Specialist searched the following databases for randomized controlled trials up to November 2017: the Cochrane Hypertension Specialised Register, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE (from 1946), Embase (from 1974), the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform, and ClinicalTrials.gov. We also contacted authors of relevant papers regarding further published and unpublished work. The searches had no language restrictions.

Selection criteria

We included randomized, active‐controlled, double‐blinded studies (RCTs) with at least six months follow‐up in people with elevated blood pressure (≥ 130/85 mmHg), which compared first‐line RAS inhibitors with other first‐line antihypertensive drug classes and reported morbidity and mortality or blood pressure outcomes. We excluded people with proven secondary hypertension.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently selected the included trials, evaluated the risks of bias and entered the data for analysis.

Main results

This update includes three new RCTs, totaling 45 in all, involving 66,625 participants, with a mean age of 66 years. Much of the evidence for our key outcomes is dominated by a small number of large RCTs at low risk for most sources of bias. Imbalances in the added second‐line antihypertensive drugs in some of the studies were important enough for us to downgrade the quality of the evidence.

Primary outcomes were all‐cause death, fatal and non‐fatal stroke, fatal and non‐fatal myocardial infarction (MI), fatal and non‐fatal congestive heart failure (CHF) requiring hospitalizations, total cardiovascular (CV) events (fatal and non‐fatal stroke, fatal and non‐fatal MI and fatal and non‐fatal CHF requiring hospitalization), and end‐stage renal failure (ESRF). Secondary outcomes were systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP) and heart rate (HR).

Compared with first‐line calcium channel blockers (CCBs), we found moderate‐certainty evidence that first‐line RAS inhibitors decreased heart failure (HF) (35,143 participants in 5 RCTs, risk ratio (RR) 0.83, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.77 to 0.90, absolute risk reduction (ARR) 1.2%), and that they increased stroke (34,673 participants in 4 RCTs, RR 1.19, 95% CI 1.08 to 1.32, absolute risk increase (ARI) 0.7%). Moderate‐certainty evidence showed that first‐line RAS inhibitors and first‐line CCBs did not differ for all‐cause death (35,226 participants in 5 RCTs, RR 1.03, 95% CI 0.98 to 1.09); total CV events (35,223 participants in 6 RCTs, RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.93 to 1.02); and total MI (35,043 participants in 5 RCTs, RR 1.01, 95% CI 0.93 to 1.09). Low‐certainty evidence suggests they did not differ for ESRF (19,551 participants in 4 RCTs, RR 0.88, 95% CI 0.74 to 1.05).

Compared with first‐line thiazides, we found moderate‐certainty evidence that first‐line RAS inhibitors increased HF (24,309 participants in 1 RCT, RR 1.19, 95% CI 1.07 to 1.31, ARI 1.0%), and increased stroke (24,309 participants in 1 RCT, RR 1.14, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.28, ARI 0.6%). Moderate‐certainty evidence showed that first‐line RAS inhibitors and first‐line thiazides did not differ for all‐cause death (24,309 participants in 1 RCT, RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.94 to 1.07); total CV events (24,379 participants in 2 RCTs, RR 1.05, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.11); and total MI (24,379 participants in 2 RCTs, RR 0.93, 95% CI 0.86 to 1.01). Low‐certainty evidence suggests they did not differ for ESRF (24,309 participants in 1 RCT, RR 1.10, 95% CI 0.88 to 1.37).

Compared with first‐line beta‐blockers, low‐certainty evidence suggests that first‐line RAS inhibitors decreased total CV events (9239 participants in 2 RCTs, RR 0.88, 95% CI 0.80 to 0.98, ARR 1.7%), and decreased stroke (9193 participants in 1 RCT, RR 0.75, 95% CI 0.63 to 0.88, ARR 1.7% ). Low‐certainty evidence suggests that first‐line RAS inhibitors and first‐line beta‐blockers did not differ for all‐cause death (9193 participants in 1 RCT, RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.78 to 1.01); HF (9193 participants in 1 RCT, RR 0.95, 95% CI 0.76 to 1.18); and total MI (9239 participants in 2 RCTs, RR 1.05, 95% CI 0.86 to 1.27).

Blood pressure comparisons between first‐line RAS inhibitors and other first‐line classes showed either no differences or small differences that did not necessarily correlate with the differences in the morbidity outcomes.

There is no information about non‐fatal serious adverse events, as none of the trials reported this outcome.

Authors' conclusions

All‐cause death is similar for first‐line RAS inhibitors and first‐line CCBs, thiazides and beta‐blockers. There are, however, differences for some morbidity outcomes. First‐line thiazides caused less HF and stroke than first‐line RAS inhibitors. First‐line CCBs increased HF but decreased stroke compared to first‐line RAS inhibitors. The magnitude of the increase in HF exceeded the decrease in stroke. Low‐quality evidence suggests that first‐line RAS inhibitors reduced stroke and total CV events compared to first‐line beta‐blockers. The small differences in effect on blood pressure between the different classes of drugs did not correlate with the differences in the morbidity outcomes.

Plain language summary

Renin angiotensin system inhibitors versus other types of medicine for hypertension

Review question

We determined how RAS (renin angiotensin system) inhibitors compared as first‐line medicines for treating hypertension with other types of first‐line medicines (thiazide diuretics, beta‐blockers, CCBs, alpha‐blockers, or central nervous system (CNS) active drugs) for hypertension.

Background

Hypertension is a long‐lasting medical condition and associated with cardiovascular mortality and morbidity such as coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular disease, and peripheral vascular disease, which will reduce quality of life. RAS inhibitors have become a focus of interventions for hypertension in recent years and have been widely prescribed for treatment of hypertension. However, it remains unclear whether RAS inhibitors are superior to other antihypertensive drugs in terms of clinically relevant outcomes.

Search date

We searched for evidence up to November 2017.

Study characteristics

We included randomized, double‐blind, parallel design RCTs for the present review. 45 trials with 66,625 participants who were followed‐up for between 0.5 year and 5.6 years were included. The participants had an average age of 66 years.

Key results

We found that first‐line RAS inhibitors caused more heart failure and stroke than first‐line thiazides. When compared to first‐line CCBs, first‐line RAS inhibitors showed superiority in preventing heart failure but were inferior in preventing stroke, with greater absolute risk reduction in heart failure than increase in stroke. When compared to first‐line beta‐blockers, RAS inhibitors reduced total cardiovascular events and stroke. Small differences on efficacy for lowering blood pressure were detected, but these did not to seem to be related to the number of heart attacks, strokes or kidney problems.

Certainty of evidence

Overall, certainty of evidence was assessed as low to moderate according to the GRADE assessment. Moderate‐certainty evidence demonstrated superiority of first‐line thiazides to first‐line RAS inhibitors in preventing heart failure and stroke. The certainty of evidence was assessed moderate for comparison between RAS inhibitors and CCBs. The certainty of evidence was low for comparison between RAS inhibitors and beta‐blockers on total cardiovascular events and stroke since the results were based primarily on one large trial with moderate to high risk of bias.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Hypertension is a worldwide health problem and has become a heavy burden on healthcare systems. Hypertension is associated with cardiovascular (CV) mortality and morbidity such as coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular disease, and peripheral vascular disease. Blood pressure (BP) is elevated in many people with type 2 diabetes, which is a major health problem worldwide. The increasing prevalence of diabetes mellitus (DM) is primarily due to the increase in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM; Inzucchi 2005). A survey of US adults with diabetes showed that 71.0% had elevated BP, defined as BP that equals or exceeds 130/85 mmHg, or current use of prescription medication for hypertension (Geiss 2002). Elevated BP is associated with a spectrum of later health problems in people with diabetes, notably CV disease and kidney damage (nephropathy). Elevated BP has been identified as a major risk factor in progression of diabetic nephropathy (Aurell 1992). The risk of CV morbidity and mortality is also doubled in hypertensive people when diabetes is present (DeStefano 1993). Review of the evidence base on this topic is covered among guidelines primarily addressing diabetes or hypertension (CPG 2013; JNC‐8 2014, respectively). Antihypertensive agents used as first‐line drugs include angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), calcium channel blockers (CCBs), beta‐blockers and diuretics.

Description of the intervention

In the past 10 years, antagonism of the renin angiotensin system (RAS) has become a focus of therapeutic interventions for hypertension. The guidelines that recommend the use of ACE inhibitors or ARBs in hypertensive people with diabetes or renal disease base their recommendations on the results of placebo‐controlled studies, which have been interpreted to show that ACE inhibitors and ARBs have specific renoprotective effects beyond those resulting from lowering blood pressure (ADA 2013; JNC‐8 2014). Blood pressure‐independent beneficial effects of ACE inhibitors and ARBs on CV outcomes have also been proposed, based on the results of several large, multicenter, placebo‐controlled studies, especially the HOPE 2000, PROGRESS 2001 and RENAAL 2001 studies. A recent meta‐analysis has suggested that in people with DM, treatment with tissue‐specific ACE inhibitors (ramipril 1.25 mg/day or 10 mg/day; perindopril 4 mg/day or 8 mg/day) when compared to placebo significantly reduces the risk of CV mortality by 14.9% (P = 0.022), myocardial infarction (MI) by 20.8% (P = 0.002) and the need for invasive coronary revascularization by 14% (P = 0.015); but not all‐cause death (risk ratio (RR) 0.913, 95% confidence intervals (CI) 0.825 to 1.011; Saha 2008). A Cochrane Review (Strippoli 2006), that included 13 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with 10,070 participants, showed a significant reduction in the risk of end‐stage renal failure (ESRF) with ACE inhibitors or ARBs compared to placebo or no treatment (RR 0.60, 95% CI 0.39 to 0.93; RR 0.78, 95% CI 0.67 to 0.91, respectively). Furthermore, 10 studies with 2034 participants showed that ACE inhibitors, at the maximum tolerable dose, significantly reduce the risk of all‐cause death in placebo‐controlled studies (RR 0.78, 95% CI 0.61 to 0.98, absolute risk reduction (ARR) 0.04, number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB) 25).

The evidence of benefit in terms of mortality and morbidity using ACE inhibitors or ARBs versus other antihypertensive agents is not clear. Some studies suggest that RAS inhibitors might prevent or delay CV events in some subgroups, but their role in the broader group of people with hypertension remains unknown (CAPPP 2001; LIFE 2002). Some studies provided evidence of benefit of RAS inhibitors on renal function over other antihypertensive drugs (ABCD‐HT 2000; LIFE 2002; MARVAL 2002), but did not examine clinically relevant outcomes such as combined renal dysfunction or renal failure.

Other systematic reviews related to this review are summarized below in chronological order by date of publication.

A systematic review and Bayesian network meta‐analysis of 63 randomized clinical trials assessed the effects of different classes of antihypertensive treatments (monotherapy and their combinations) on survival and major renal outcomes in people with diabetes (Wu 2013). This review examined clinical endpoints that included all‐cause mortality, requirement for dialysis and doubling of serum creatinine levels. When compared with placebo, ARBs showed no reduction in any of the three outcomes, and ACE inhibitors only reduced the doubling of serum creatinine levels compared with placebo (odds ratio (OR) 0.58, 95% CI 0.32 to 0.90). Although ACE inhibitors did not show other beneficial effects compared with other drugs, the researchers supported the use of ACE inhibitors as the first‐line antihypertensive agent in people with diabetes. However, all the suggestions were based on the results of Bayesian network meta‐analysis, which not only included the results of direct comparisons, but also incorporated indirect comparisons. The review did not report the proportion of hypertensive people, and the indirect comparisons could affect the applicability of this evidence.

A systematic review and meta‐analysis by Casas et al assessed the effect of RAS inhibitors and other antihypertensive drugs on renal outcomes (Casas 2005). In this review, the effects of ACE inhibitors or ARBs in placebo‐controlled studies were indirectly compared to the effects of other antihypertensive drugs in people with type 1 or type 2 diabetes or without diabetes. For those with diabetic nephropathy, comparative studies of ACE inhibitors or ARBs showed no benefit on ESRF, glomerular filtration rate (GFR), or creatinine levels. Placebo‐controlled studies of ACE inhibitors or ARBs decreased all renal outcomes, and also reduced BP.

A Cochrane Review of RCTs compared any antihypertensive agent with placebo or another agent in hypertensive or normotensive people with diabetes and no kidney disease (Strippoli 2005). This review assessed the renal outcomes and all‐cause and CV mortality. It showed that compared to placebo, ACE inhibitors significantly reduced the development of microalbuminuria (six trials, 3840 participants: RR 0.60, 95% CI 0.43 to 0.84, ARR 0.03 and NNTB 33), but not doubling of creatinine or ESRF or all‐cause death. Compared to CCBs, ACE inhibitors significantly reduced progression to microalbuminuria (four trials,1210 participants: RR 0.58, 95% CI 0.40 to 0.84, ARR 0.05 and NNTB 20).

A meta‐analysis of double‐blinded RCTs by Siebenhofer et al compared ARBs to placebo or standard antihypertensive treatment in T2DM (three studies, 4423 participants) and examined clinical endpoints (all‐cause death, CV morbidity and mortality, and ESRF; Siebenhofer 2004). The only statistically significant benefit of ARBs was the reduction of ESRF compared with placebo (OR 0.73, 95% CI 0.60 to 0.89, ARR 0.05 and NNTB 20). ARBs failed to show superiority to standard antihypertensive treatment (CCBs, beta‐blockers) for total mortality and CV morbidity and mortality. However, ACE inhibitors were not included in this meta‐analysis.

A systematic review and meta‐analysis by Pahor et al assessed therapeutic benefits of ACE inhibitors and other antihypertensive drugs in people with T2DM and hypertension (Pahor 2000). This meta‐analysis showed a significant benefit of ACE inhibitors compared with alternative treatments (CCBs, beta‐blockers, diuretics) on acute MI (63% reduction, P < 0.001, ARR 0.06 and NNTB 17), CV events (51% reduction, P < 0.001, ARR 8% and NNTB 13), and all‐cause death (62% reduction, P = 0.010, ARR 0.02 and NNTB 40), but not stroke. However, ARBs were not included in this review. Renal outcomes (ESRF, GFR, serum creatinine or albuminuria) were not reported.

A meta‐analysis of 100 controlled and uncontrolled studies in 2494 participants with diabetes assessed the effect on proteinuria of different classes of antihypertensive agents (ACE inhibitors, CCBs, beta‐blockers and control; Kasiske 1993). This review showed that ACE inhibitors produced the greatest reductions in urine albumin and protein excretion compared with other antihypertensive agents (P < 0.05 versus CCBs; P < 0.05 versus control). ACE inhibitors achieved these beneficial effects on renal function independent of changes in blood pressure. This meta‐analysis examined surrogate markers rather than clinically relevant endpoints (such as ESRF, all‐cause death).

How the intervention might work

The RAS is a potentially pathophysiologic mechanism that causes diabetic heart disease. Angiotensin II (Ang II) is thought to play an important role in the pathogenesis of CV complications (Dzau 2001). RAS inhibitors have been proven to have additional antiproteinuric and renoprotective benefits on diabetic nephropathy (Kocks 2002).

Drugs inhibiting the RAS include: renin inhibitors, ACE inhibitors and ARBs, which inhibit the enzymatic action of renin, the conversion of angiotensin I (Ang I) to Ang II and block the Ang II receptors, respectively.

ACE inhibitors and ARBs block the RAS further downstream than renin inhibitors, which prevent the formation of renin. Renin is the substrate responsible for all downstream events that lead to production of Ang II and subsequent stimulation of its receptors. It has been proposed that renin inhibitors might provide a more effective means of blockade of the RAS than ACE inhibitors or ARBs (Duprez 2006).

Why it is important to do this review

RAS inhibitors are widely prescribed for treatment of hypertension. ACE inhibitors and ARBs are specifically promoted for people with diabetes on the basis of postulated advantages for the reduction of diabetic nephropathy and CV morbidity and mortality. Despite widespread use of ACE inhibitors and ARBs for diabetes, their efficacy compared to other antihypertensive drugs is still unclear. A systematic review is needed in order to establish the benefits and harms of clinically relevant outcomes (especially all‐cause death and morbidity, renal and CV outcomes) of RAS inhibitors compared to other antihypertensive drugs in people with elevated blood pressure.

Objectives

To evaluate the benefits and harms of first‐line RAS inhibitors compared to other first‐line antihypertensive drugs in people with hypertension.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Study design must meet the following criteria:

RCTs with parallel design;

double‐blind;

minimum follow‐up of six months.

Types of participants

People with primary elevated BP (that equals or exceeds 130/85 mmHg). We chose this BP threshold, lower than the standard 140/90 mmHg, to include more people and to be consistent with the recommended lower targets for people with hypertension and diabetes. We excluded people with proven secondary hypertension.

Types of interventions

RAS inhibitors including ACE inhibitors, ARBs or renin inhibitors:

ACE inhibitors include: alacepril, altiopril, benazepril, captopril, ceronapril, cilazapril, delapril, derapril, enalapril, enalaprilat, fosinopril, idapril, imidapril, lisinopril, moexipril, moveltipril, pentopril, perindopril, quinapril, ramipril, spirapril, temocapril, trandolapril, and zofenopril.

ARBs include: candesartan, eprosartan, irbesartan, losartan, olmesartan, tasosartan, telmisartan, valsartan, and KT3‐671.

Renin inhibitors include: aliskiren, remikiren.

Comparators

Any other antihypertensive drug class including: thiazides, beta‐blockers, CCBs, alpha‐blockers, or central nervous system (CNS) active drugs.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

All‐cause death.

All‐cause serious morbidity (non‐fatal serious adverse events).

-

Total CV events:

fatal and non‐fatal MI;

fatal and non‐fatal stroke;

fatal and non‐fatal congestive heart failure (CHF) requiring hospitalizations.

-

Renal outcomes:

ESRF (defined as a requirement for maintenance dialysis).

Secondary outcomes

Change in or end‐point systolic and diastolic BP.

Change in or end‐point heart rate.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

The Cochrane Hypertension Group Information Specialist conducted systematic searches in the following databases for randomized controlled trials without language, publication year or publication status restrictions:

the Cochrane Hypertension Specialised Register via the Cochrane Register of Studies (CRS‐Web) (searched 22 November 2017);

the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2017, Issue 11) via Wiley (searched 22 November 2017);

MEDLINE Ovid (from 1946 onwards), MEDLINE Ovid Epub Ahead of Print, and MEDLINE Ovid In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations (searched 20 November 2017);

Embase Ovid (searched 20 November 2017);

ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov) (searched 20 November 2017);

World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (www.who.int/trialsearch) (searched 22 November 2017).

The Information Specialist modelled subject strategies for databases on the search strategy designed for MEDLINE. Where appropriate, they were combined with subject strategy adaptations of the highly sensitive search strategy designed by Cochrane for identifying randomized controlled trials (as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0, Box 6.4.b. (Handbook 2011)). Search strategies are provided in Appendix 1.

Searching other resources

The Cochrane Hypertension Group Information Specialist searched the Hypertension Specialised Register segment (which includes searches of MEDLINE, Embase and Epistemonikos for systematic reviews) to retrieve existing systematic reviews relevant to this systematic review, so that we could scan their reference lists for additional trials. The Specialised Register also includes searches of CAB Abstracts & Global Health, CINAHL, ProQuest Dissertations & Theses and Web of Knowledge.

We checked the bibliographies of included studies and any relevant systematic reviews identified for further references to relevant trials.

Where necessary, we contacted authors of key papers and abstracts to request additional information about their trials.

Data collection and analysis

We performed the initial search of all the databases to identify citations with potential relevance. In our initial screen of these abstracts we excluded articles whose titles or abstracts, or both, were clearly irrelevant. We retrieved the full text of the remaining articles (and translated into English where required) to assess whether the trials met the prespecified inclusion criteria. We searched the bibliographies of pertinent articles, reviews and texts for additional relevant citations. Two independent review authors assessed the eligibility of the trials using a study selection form. A third review author resolved discrepancies.

Selection of studies

We imported references and abstracts of search results into Reference Manager software. We based selection of studies on the criteria listed above.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors independently extracted data using a standard form, and then cross‐checked them. All numeric calculations and graphic interpolations were confirmed by a second person.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed the risk of bias for each trial according to Cochrane 'Risk of bias' guidelines using the following six domains (Higgins 2011):

sequence generation;

allocation concealment;

blinding or objective assessment of primary outcomes;

incomplete outcome data;

selective outcome reporting;

other biases.

We used the overall risk of bias in the GRADE assessment in the 'Summary of findings' table. We conducted GRADE assessment according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

Measures of treatment effect

We based quantitative analysis of outcomes on intention‐to‐treat principles as much as possible. For dichotomous outcomes, we expressed results as the risk ratio (RR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI). For combining continuous variables (systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP) and heart rate (HR)), we used the mean difference (with 95% CI).

Dealing with missing data

If the included studies had missing information, we contacted investigators (using email, letter or fax or both) to obtain the missing information.

When studies did not report a within‐study variance for the effect change of continuous data, we imputed the standard deviation (SD) using the following hierarchy:

pooled SD calculated either from the t‐statistic corresponding to an exact P value reported or from the 95% CI of the mean difference between treatment group and comparative group;

SD at the end of treatment;

SD at baseline;

weighted mean SD of change calculated from at least three other trials using the same dose regimen;

weighted mean SD of change calculated from other trials using any dose.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We used Chi² and I² statistics to test for heterogeneity of treatment effect among trials. We consider a Chi² value P < 0.1 or I² value > 50% indicative of heterogeneity.We used the fixed‐effect model when there was homogeneity and used the random‐effects model to test for statistical significance where there was heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

We used funnel plots to investigate publication reporting bias when suspected. As a rule of thumb, tests for funnel plot asymmetry should be used only when there are at least 10 studies included in the meta‐analysis, because when there are fewer studies the power of the tests is too low to distinguish chance from real asymmetry.

Data synthesis

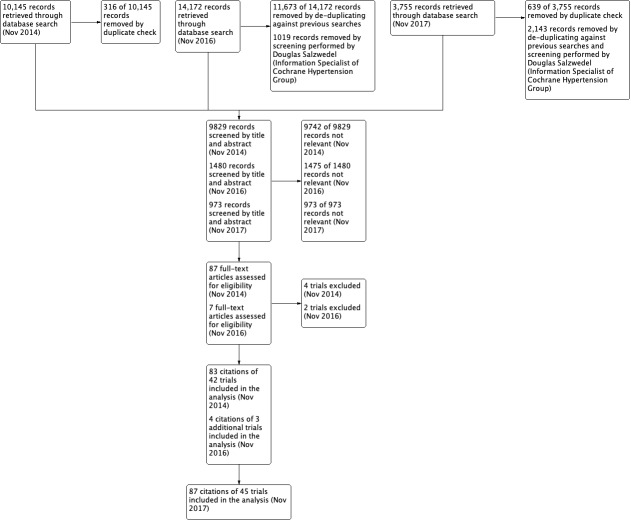

We performed data synthesis and analyses using the Cochrane Review Manager software, RevMan 5.3 (RevMan 2014). We described data results in tables and forest plots according to Cochrane guidelines. In addition we gave full details for all studies we included and excluded. We have included a standard PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1).

1.

PRISMA Study flow diagram

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Where appropriate, we performed the following subgroup analyses:

-

Heterogeneity among participants could be related to:

gender;

age;

presence of diabetes at initiation of antihypertensive treatment (time of trial entry);

baseline blood pressure;

previous renal disease;

previous CV disease.

-

Heterogeneity in treatments could be related to:

dose of drugs;

duration of therapy.

Sensitivity analysis

We tested the robustness of the results using several sensitivity analyses, including:

trials that were industry‐sponsored versus non‐industry‐sponsored;

trials with reported standard deviations of effect change versus imputed standard deviations;

trials that have a high risk of bias versus those with a low risk of bias.

Results

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies.

Results of the search

Up to November 2017, the search strategy identified 15,145 citations (Figure 1). After excluding all the studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria or those we have included before, we performed full‐text assessment of five potentially eligible studies and identified three new trials (NESTOR 2015; SILVHIA 2001; Xiao 2016) (four citations) that we included in the review update. This update includes 45 RCTs with 87 citations, i.e. the three new RCTs and the 42 RCTs (83 citations) in the first publication of this review (Xue 2015).

Included studies

The 45 included studies involved 66,625 participants with a mean age of 66 years. Participants in nine studies were under 50 years old (Buus 2004; Buus 2007; Dahlöf 1993; Pedersen 1997; Schiffrin 1994; Sørensen 1998; Tarnow 1999; Xiao 2016; Zeltner 2008); in 22 studies participants were between 50 and 59 years old (Ariff 2006; Dahlöf 2002; Dalla 2004; Derosa 2004; Derosa 2005; Derosa 2014; Esnault 2008; Estacio 1998; Gottdiener 1998; Hauf‐Zachariou 1993; Hughes 2008; IDNT 2001; Malmqvist 2002; Parrinello 2009; Petersen 2001; Roman 1998; Schmieder 2009; Schneider 2004; Seedat 1998; SILVHIA 2001; Tedesco 1999; TOHMS 1993); and over 60 years old in the remaining 14 studies (ALLHAT 2002; BENEDICT 2004; Devereux 2001; Fogari 2012; Gerritsen 1998; Hajjar 2013; Hayoz 2012; Himmelmann 1996; LIFE 2002; NESTOR 2015; Ostman 1998; Schram 2005; Terpstra 2004; VALUE 2004). The mean duration of therapy was 1.9 years, ranging from 0.5 to 5.6 years. The number of participants who received RAS inhibitors was 25,421, while 5,525 received beta‐blockers, 19,040 CCBs, 16,316 thiazides, 240 alpha‐blockers, and 83 CNS active drugs. Three studies contained multiple different drug groups: Gottdiener 1998 contained six, TOHMS 1993 contained five, and ALLHAT 2002 contained three, so the numbers of studies comparing RAS inhibitors with other drug classes were 17 for beta‐blockers, 22 for CCBs ‐ within which there were two studies that used non‐dihydropyridine (BENEDICT 2004; Gottdiener 1998), and 20 studies that used dihydropyridine, 10 for thiazides, 3 for alpha‐blockers, and 1 for CNS active drugs.

Most of the included studies were industry‐sponsored (28/45). Participants with diabetes were involved in 14 studies, while one study included participants with impaired fasting glucose; participants with decreased renal function in seven studies, and seven studies contained participants with at least one risk factor for CV diseases. Three studies recruited only men (Dahlöf 1993; Gottdiener 1998; Schiffrin 1994). One study included only women, as it focused on postmenopausal women (Hayoz 2012). All 87 included citations were published in English with publication years ranging from 1993 to 2016.

Most participants (30 studies) were recruited from European countries; seven studies included participants from North America; two studies included participants from North America, Europe, and Asia (Dahlöf 2002; VALUE 2004); one study included participants from North America, South America, Europe, Asia and Australia (IDNT 2001); NESTOR 2015 included participants from North America, South America, Europe and Asia; one study included participants from North America and Europe (LIFE 2002); Devereux 2001 included participants from Europe and Asia; Seedat 1998 included participants from South Africa; and Xiao 2016 included participants from Asia. Fifteen of the 45 included studies reported ethnicity; the percentages of white, Hispanic, Asian, Black and other race participants were 71.0%, 0.3%, 1.7%, 23.7% and 3.3%, respectively.

In terms of baseline comorbidities, nine studies stated that they would not include people with a history of prior MI or stroke; 14 studies allowed participants with a history of prior MI or stroke if this had not occurred within the previous three or six months); the other 22 studies made no clear statement, but in general the proportion of participants without cardiac‐cerebral vascular comorbidities was high. Overall, this review represents treatment effects for primary prevention.

A stepwise therapeutic regimen was used in 34 studies, in which add‐on drugs were allowed to achieve BP goals. The second‐line drugs included open‐label, non‐study agents such as CCBs, thiazides, or beta‐blockers. The remaining eleven studies restricted the therapeutic regimens to monotherapy (Dahlöf 1993; Derosa 2004; Derosa 2014; Gottdiener 1998; Himmelmann 1996; Hauf‐Zachariou 1993; Sørensen 1998; Tedesco 1999; Terpstra 2004; TOHMS 1993; Xiao 2016).

With regard to the clinical classification of hypertension (see ESH/ESC 2013), we classified mean blood pressure of participants at baseline into two groups: 30 studies included Grade 1 hypertensive participants (SBP: 140 mmHg to 159 mmHg); 15 studies included Grade 2 hypertensive participants (SBP: 160 mmHg to 179 mmHg). Baseline untreated mean BP was 156/89 mmHg (SBP/DBP) for RAS inhibitors; 151/86 mmHg for CCBs; 172/98 mmHg for beta‐blockers; 146/85 mmHg for thiazides; 150/96 mmHg for alpha‐blockers; 152/99 mmHg for CNS active drugs.

For details, see Characteristics of included studies.

Excluded studies

Full‐text screening according to the prespecified inclusion criteria led to us excluding three of the seven citations during the update, in addition to the four citations excluded in the previous version of the review. In total, we excluded seven citations of six studies in the updated review. The reasons for each study's exclusion are described in Characteristics of excluded studies.

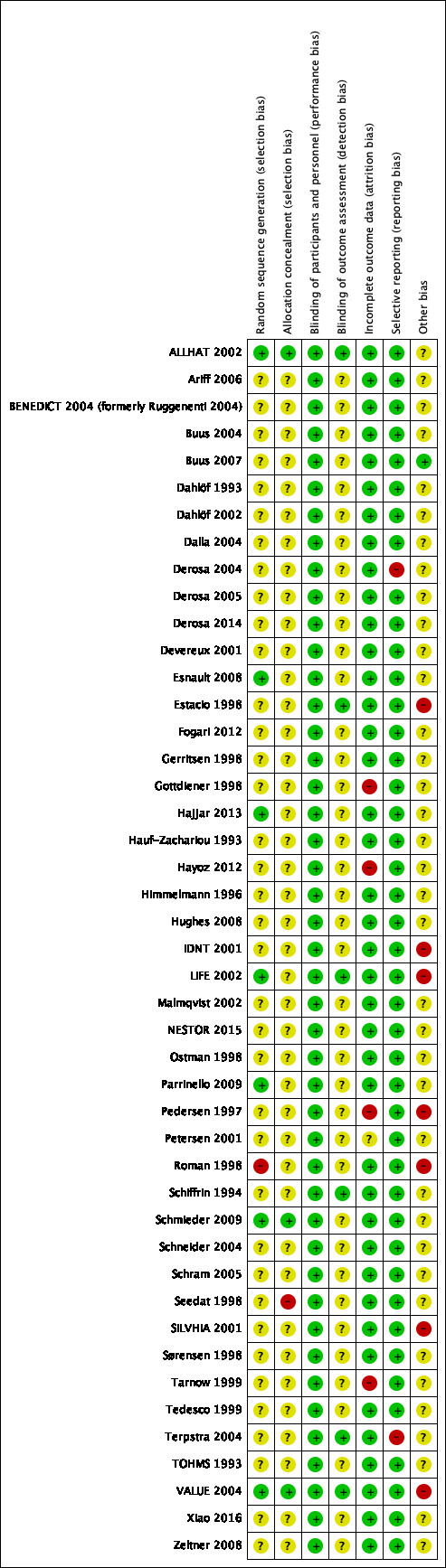

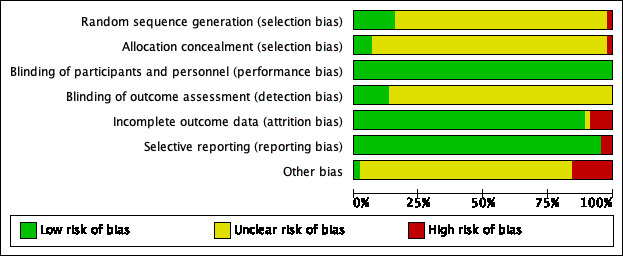

Risk of bias in included studies

The data extraction forms for each included study contained the details of study design, randomization, allocation, blinding, duration of treatment, funding, diagnosis, number of participants, age of participants, gender of participants, history of participants, inclusion and exclusion criteria, outcomes and intervention. We assessed the risk of bias for each included study (Figure 2), and all included studies (Figure 3), in detail (see Characteristics of included studies).

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included citations

3.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included citations

Allocation

We assessed seven of the 45 studies as being at low risk of bias for reporting the method for generation of random sequence and one study as being at high risk (Roman 1998); in the remaining 37 studies the risk of bias for this domain was unclear. We assessed three of the 45 studies as being at low risk for allocation concealment, one study as being at high risk, and 41 studies as being at unclear risk. The three studies at low risk used either a central office allocation (ALLHAT 2002; VALUE 2004), or were strictly confidential until unblinding time (Schmieder 2009); one study reported using alternate allocation, which is a high risk method (Seedat 1998); two studies at unclear risk of selection bias reported the allocation concealment by using an envelope to maintain the random number (Derosa 2004; Derosa 2005); however, it was not clear whether the envelope was transparent or opaque.

Blinding

All the 45 included studies were at low risk of performance bias as they were all double‐blinded and met the inclusion criteria. In terms of detection bias, we judged only six studies to be at low risk due to the use of blinding for outcome assessment for BP or HR, which was critical for the control of detection bias; the risk of bias for this domain was unclear for the remaining 39 studies. We thought that unblinded assessment of outcomes like MI, stroke, HF, CV events, all‐cause death, and ESRF was not as critical as it would be for BP and HR.

Incomplete outcome data

We judged the risk of attrition bias in 40 of the 45 studies included in the review to be low because missing data were unlikely to have an impact because of low or equal numbers of dropouts between arms. In one study this risk was unclear (Petersen 2001); and in the other four studies we judged it to be high. Among these four studies with a high risk of attrition bias, Gottdiener 1998 only included participants with a left atrial dimension measurement (a small proportion of all participants) in the analysis. Pedersen 1997 and Tarnow 1999 had many participants lost to follow‐up at the end of study and Hayoz 2012 reported inconsistent numbers of participants in Figure 1 and Table 2.

Selective reporting

In this review, we judged 43 included studies to have a low risk of reporting bias; we judged that two studies had a high risk of selective reporting as they did not report HR, which was a prespecified outcome in their 'Methods' sections (Derosa 2004; Terpstra 2004).

Other potential sources of bias

Seven studies had a high risk of other potential sources of bias. Pedersen 1997 and Roman 1998 had unbalanced baseline characteristics. VALUE 2004 had an unbalanced proportion of monotherapy and highest dose between the two groups (including HCTZ and other non‐study add‐on drugs); Estacio 1998 had an unbalanced proportion of monotherapy. LIFE 2002 was evaluated as being at high risk as it was funded and conducted by the pharmaceutical company Merck. Similarly, many of the authors of IDNT 2001 had received research grants from Bristol‐Myers Squibb. Numbers of participants reported for different outcomes were not consistent in SILVHIA 2001.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3

Summary of findings for the main comparison. RAS inhibitors compared to CCBs for hypertension.

| First‐line RAS inhibitors compared to first‐line CCBs for hypertension | |||||||

| Patient or population: people with hypertension Settings: outpatients with mean follow‐up of 4.5 years Intervention: First‐line RAS inhibitors Comparison: First‐line CCBs | |||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) |

Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) |

Comments | ||

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | ||||||

| CCBs | RAS inhibitors | ||||||

| All‐cause death | 124 per 1000 | 127 per 1000 (121 to 135) | RR 1.03 (0.98 to 1.09) | 35,226 (5) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | ||

| Total cardiovascular events | 178 per 1000 | 174 per 1000 (166 to 182) | RR 0.98 (0.93 to 1.02) | 35,223 (6) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | ||

| Death or hospitalization for heart failure | 72 per 1000 | 60 per 1000 (55 to 65) | RR 0.83 (0.77 to 0.90) | 35,143 (5) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | ARR = 1.2% NNTB = 83 |

|

| Total myocardial infarction | 68 per 1000 | 69 per 1000 (63 to 74) | RR 1.01 (0.93 to 1.09) | 35,043 (5) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | ||

| Total stroke | 39 per 1000 | 46 per 1000 (42 to 51) | RR 1.19 (1.08 to 1.32) | 34,673 (4) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | ARI = 0.7% NNTH = 143 |

|

| End stage renal failure | 25 per 1000 | 22 per 1000 (19 to 26) | RR 0.88 (0.74 to 1.05) | 19,551 (4) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1, 2 | ||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio; ARR: absolute risk reduction; ARI: absolute risk increase; NNTB: number needed to treat to prevent one adverse outcome; NNTH: number needed to treat to cause one adverse outcome | |||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect Moderate certainty: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate Low certainty: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate Very low certainty: we are very uncertain about the estimate | |||||||

1Downgraded because we judged some of the included trials to be at high risk of bias. 2Downgraded because of wide confidence intervals which include a clinically important benefit.

Summary of findings 2. RAS inhibitors compared to thiazides for hypertension.

| First‐line RAS inhibitors compared to first‐line thiazides for hypertension | ||||||

|

Patient or population: people with hypertension

Settings: outpatients with mean follow‐up of 4.9 years

Intervention: First‐line RAS inhibitors Comparison: First‐line thiazides | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) |

Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) |

Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Thiazides | RAS inhibitors | |||||

| All‐cause death | 144 per 1000 |

144 per 1000 (135 to 154) |

RR 1.00 (0.94 to 1.07) |

24,309 (1) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

|

Total cardiovascular events |

194 per 1000 | 204 per 1000 (194 to 215) | RR 1.05 (1.00 to 1.11) | 24,379 (2) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| Death or hospitalization for heart failure | 57 per 1000 |

68 per 1000 (61 to 75) |

RR 1.19 (1.07 to 1.31) |

24,309 (1) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | ARI = 1.1% NNTH = 91 |

| Total myocardial infarction | 93 per 1000 | 86 per 1000 (80 to 94) | RR 0.93 (0.86 to 1.01) | 24,379 (2) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| Total stroke | 44 per 1000 |

50 per 1000 (45 to 56) |

RR 1.14 (1.02 to 1.28) |

24,309 (1) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | ARI = 0.6% NNTH = 167 |

|

End stage renal failure Follow‐up: mean 4.9 years |

13 per 1000 |

14 per 1000 (11 to 18) |

RR 1.10 (0.88 to 1.37) |

24,309 (1) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1, 2 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio; ARI; absolute risk increase. NNTH: number needed to treat to cause one adverse outcome | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect Moderate certainty: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate Low certainty: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate Very low certainty: we are very uncertain about the estimate | ||||||

1Based on one large trial (ALLHAT 2002). 2Downgraded due to wide confidence intervals.

Summary of findings 3. RAS inhibitors compared to beta‐blockers for hypertension.

| First‐line RAS inhibitors compared to first‐line beta‐blockers for hypertension | ||||||

| Patient or population: people with hypertension Settings: outpatients with mean follow‐up of 4.8 years Intervention: First‐line RAS inhibitors Comparison: First‐line beta‐blockers | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Β‐blockers | RAS inhibitors | |||||

| All‐cause death | 94 per 1000 | 84 per 1000 (73 to 95) |

RR 0.89 (0.78 to 1.01) |

9193 (1) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1, 2 | |

|

Total cardiovascular events |

143 per 1000 | 126 per 1000 (114 to 140) | RR 0.88 (0.80 to 0.98) | 9239 (2) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1, 2 | ARR = 1.7% NNTB = 59 |

| Total heart failure | 35 per 1000 |

33 per 1000 (27 to 41) |

RR 0.95 (0.76 to 1.18) |

9193 (1) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1, 2 | |

|

Total myocardial infarction |

41 per 1000 | 43 per 1000 (35 to 52) | RR 1.05 (0.86 to 1.27) | 9239 (2) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1, 2 | |

| Total stroke | 67 per 1000 |

50 per 1000 (42 to 59) |

RR 0.75 (0.63 to 0.88) |

9193 (1) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1, 2 | ARR = 1.7% NNTB = 59 |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio; ARR: absolute risk reduction. NNTB: number needed to treat to prevent one adverse outcome | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect Moderate certainty: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate Low certainty: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate Very low certainty: we are very uncertain about the estimate | ||||||

1Based primarily on one moderate‐sized trial (LIFE 2002). 2Wide confidence intervals and moderate to high risk of bias.

First‐line RAS inhibitors versus first‐line CCBs

Compared with CCBs, RAS inhibitors decreased HF (5 RCTs, 35,143 participants, RR 0.83, 95% CI 0.77 to 0.90; Analysis 1.3), and increased stroke (4 RCTs, 34,673 participants, RR 1.19, 95% CI 1.08 to 1.32; Analysis 1.5), but were not significantly different for all‐cause death (5 RCTs, 35,226 participants, RR 1.03, 95% CI 0.98 to 1.09; Analysis 1.1), total CV events (6 RCTs, 35,223 participants, RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.93 to 1.02; Analysis 1.2), total MI (5 RCTs, 35,043 participants, RR 1.01, 95% CI 0.93 to 1.09; Analysis 1.4), and ESRF (4 RCTs, 19,551 participants, RR 0.88, 95% CI 0.74 to 1.05; Analysis 1.6). CCBs lowered SBP and DBP to a greater degree than RAS inhibitors (SBP: 20 RCTs, 36,437 participants, MD 1.23, 95% CI 0.90 to 1.56; Analysis 1.7; DBP: 20 RCTs, 36,437 participants, MD 0.98, 95% CI 0.79 to 1.18; Analysis 1.8). There was no difference in the effect of CCBs and RAS inhibitors on HR (5 RCTs, 540 participants, MD 0.30, 95% CI ‐1.63 to 2.22; Analysis 1.9).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 RAS inhibitors vs CCBs, Outcome 3 Total HF.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 RAS inhibitors vs CCBs, Outcome 5 Total stroke.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 RAS inhibitors vs CCBs, Outcome 1 All‐cause death.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 RAS inhibitors vs CCBs, Outcome 2 Total CV events.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 RAS inhibitors vs CCBs, Outcome 4 Total MI.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 RAS inhibitors vs CCBs, Outcome 6 ESRF.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 RAS inhibitors vs CCBs, Outcome 7 SBP.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 RAS inhibitors vs CCBs, Outcome 8 DBP.

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 RAS inhibitors vs CCBs, Outcome 9 HR.

First‐line RAS inhibitors versus first‐line thiazides

Compared with thiazides, RAS inhibitors increased HF (1 RCT, 24,309 participants, RR 1.19, 95% CI 1.07 to 1.31; Analysis 2.3), and increased stroke (1 RCT, 24,309 participants, RR 1.14, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.28; Analysis 2.5), but were not significantly different for all‐cause death (1 RCT, 24,309 participants, RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.94 to 1.07; Analysis 2.1), total CV events (2 RCTs, 24,379 participants, RR 1.05, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.11; Analysis 2.2), total MI (2 RCTs, 24,379 participants, RR 0.93, 95% CI 0.86 to 1.01; Analysis 2.4), and ESRF (1 RCT, 24,309 participants, RR 1.10, 95% CI 0.88 to 1.37; Analysis 2.6). Thiazides lowered SBP to a greater degree than RAS inhibitors (10 RCTs, 26,382 participants, MD 1.60, 95% CI 1.20 to 1.99; Analysis 2.7), but had a similar effect to RAS inhibitors on DBP (9 RCTs, 26,335 participants, MD ‐0.12, 95% CI ‐0.36 to 0.13; Analysis 2.8). There was also no difference in the effect on HR, but only two small trials reported this outcome (2 RCTs, 84 participants, MD 0.66, 95% CI ‐2.87 to 4.19; Analysis 2.9).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 RAS inhibitors vs thiazides, Outcome 3 Total HF.

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 RAS inhibitors vs thiazides, Outcome 5 Total stroke.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 RAS inhibitors vs thiazides, Outcome 1 All‐cause death.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 RAS inhibitors vs thiazides, Outcome 2 Total CV events.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 RAS inhibitors vs thiazides, Outcome 4 Total MI.

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 RAS inhibitors vs thiazides, Outcome 6 ESRF.

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2 RAS inhibitors vs thiazides, Outcome 7 SBP.

2.8. Analysis.

Comparison 2 RAS inhibitors vs thiazides, Outcome 8 DBP.

2.9. Analysis.

Comparison 2 RAS inhibitors vs thiazides, Outcome 9 HR.

First‐line RAS inhibitors versus first‐line beta‐blockers

Compared with beta‐blockers, RAS inhibitors decreased total CV events (2 RCTs, 9,239 participants, RR 0.88, 95% CI 0.80 to 0.98; Analysis 3.2) and decreased stroke (1 RCT, 9,193 participants, RR 0.75, 95% CI 0.63 to 0.88; Analysis 3.5). Beta‐blockers and RAS inhibitors were not significantly different for all‐cause death (1 RCT, 9,193 participants, RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.78 to 1.01; Analysis 3.1), HF (1 RCT, 9,193 participants, RR 0.95, 95% CI 0.76 to 1.18; Analysis 3.3), or MI (2 RCTs, 9.239 participants, RR 1.05, 95% CI 0.86 to 1.27; Analysis 3.4). The effect on ESRF could not be assessed because there was only one small trial that examined this outcome (1 RCT, 46 participants, RR 0.33, 95% CI 0.01 to 7.78; Analysis 3.6). Beta‐blockers lowered DBP and HR more than RAS inhibitors (DBP: 16 RCTs, 10,905 participants, MD 0.48, 95% CI 0.14 to 0.83; Analysis 3.8; HR: 10 RCTs, 9,979 participants, MD 6.05, 95% CI 5.59 to 6.50; Analysis 3.9). The effect on SBP did not differ between the two classes of drug (16 RCTs, 10,905 participants, MD ‐0.55, 95% CI ‐1.22 to 0.11; Analysis 3.7).

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 RAS inhibitors vs beta‐blockers (β‐blockers), Outcome 2 Total CV events.

3.5. Analysis.

Comparison 3 RAS inhibitors vs beta‐blockers (β‐blockers), Outcome 5 Total stroke.

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 RAS inhibitors vs beta‐blockers (β‐blockers), Outcome 1 All‐cause death.

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 RAS inhibitors vs beta‐blockers (β‐blockers), Outcome 3 Total HF.

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 RAS inhibitors vs beta‐blockers (β‐blockers), Outcome 4 Total MI.

3.6. Analysis.

Comparison 3 RAS inhibitors vs beta‐blockers (β‐blockers), Outcome 6 ESRF.

3.8. Analysis.

Comparison 3 RAS inhibitors vs beta‐blockers (β‐blockers), Outcome 8 DBP.

3.9. Analysis.

Comparison 3 RAS inhibitors vs beta‐blockers (β‐blockers), Outcome 9 HR.

3.7. Analysis.

Comparison 3 RAS inhibitors vs beta‐blockers (β‐blockers), Outcome 7 SBP.

First‐line RAS inhibitors versus first‐line alpha‐blockers

RAS inhibitors lowered SBP more than alpha‐blockers did (3 small RCTs, 380 participants, MD ‐2.38, 95% CI ‐3.98 to ‐0.78; Analysis 4.1), but did not differ in their effect on DBP and HR (DBP 3 small RCTs, 380 participants, MD ‐0.12, 95% CI ‐1.09 to 0.85; Analysis 4.2; HR: 1 small RCT, 44 participants, MD 3.10, 95% CI ‐2.41 to 8.61; Analysis 4.3).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 RAS inhibitors vs alpha‐blockers (α‐blockers), Outcome 1 SBP.

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 RAS inhibitors vs alpha‐blockers (α‐blockers), Outcome 2 DBP.

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 RAS inhibitors vs alpha‐blockers (α‐blockers), Outcome 3 HR.

First‐line RAS inhibitors versus first‐line CNS active drugs

When compared with CNS active drugs in one small trial, RAS inhibitors did not differ in their effect on SBP (1 RCT, 56 participants, MD 1.30, 95% CI ‐6.01 to 8.61; Analysis 5.1), DBP (1 RCT, 56 participants, MD ‐0.30, 95% CI ‐1.85 to 1.25; Analysis 5.2), or HR (1 RCT, 56 participants, MD 1.50, 95% CI ‐4.13 to 7.13; Analysis 5.3).

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 RAS inhibitors vs CNS active drug, Outcome 1 SBP.

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 RAS inhibitors vs CNS active drug, Outcome 2 DBP.

5.3. Analysis.

Comparison 5 RAS inhibitors vs CNS active drug, Outcome 3 HR.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

In this review, when the result was significant and the value of I2 was greater than 50%, we tested whether the result was still significant using the random‐effects model. However, in presenting the data we use the fixed‐effect model, as it weights the contributing trials more appropriately.

In an attempt to explore the heterogeneity of RAS inhibitors versus CCBs on HF (I2 of 68%) we analyzed the trials according to whether or not the participants had decreased renal function. In those with decreased renal function the RR was 0.55, 95% CI 0.43 to 0.70, without heterogeneity (Dalla 2004; IDNT 2001); while in those without decreased renal function the RR was 0.87, 95% CI 0.80 to 0.95, without heterogeneity (ALLHAT 2002; Estacio 1998; VALUE 2004). Subgroup analysis thus provided a possible explanation for the variation of effect sizes across the studies. The magnitude of the effect of RAS inhibitors for decreasing HF, when compared to CCBs, was greater in hypertensive participants with kidney dysfunction than in those with normal renal function.

The key results on the clinically important outcomes and grading of the evidence quality are presented in the 'Summary of findings' tables, which we created by using the software GRADEpro 3.6. (Atkins 2004) (Table 1; Table 2; Table 3) These tables provide the absolute effects as well as the relative effects.

Discussion

Summary of main results

This first update of the review provides no change in primary outcomes, because the three new RCTs added only provided blood pressure and heart rate data. Compared with first‐line CCBs, first‐line RAS inhibitors reduce death or hospitalizations for HF, increase fatal and non‐fatal stroke, and are similar for all‐cause death, total CV events and ESRF events. Compared with first‐line thiazides, first‐line RAS inhibitors increase death or hospitalizations for HF and increase fatal and non‐fatal stroke. RAS inhibitors are similar to thiazides for all‐cause death, total CV events, fatal and non‐fatal MI and ESRF events. Compared with first‐line beta‐blockers, first‐line RAS inhibitors reduce total CV events and fatal and non‐fatal stroke and are similar for all‐cause death, HF, MI and ESRF. There were no RCTs that compared first‐line RAS inhibitors with any other classes of drugs that reported mortality and morbidity outcomes.

These results demonstrate that first‐line RAS inhibitors are an inferior choice to first‐line thiazides, because first‐line RAS inhibitors increase both death and hospitalizations for HF and fatal and non‐fatal stroke events compared to thiazides.

The results also suggest that first‐line RAS inhibitors are a better choice than first‐line CCBs, because the absolute reduction in death or hospitalizations for HF of 1.2% found with RAS inhibitors is greater than the increase in fatal and non‐fatal stroke of 0.7%. These findings confirm and extend the findings of the Cochrane Review of first‐line CCBs versus other classes of drugs (Chen 2010).

The results also suggest that RAS inhibitors are a better first‐line choice than first‐line beta‐blockers for hypertension, confirming the conclusions of two other Cochrane Reviews (Wiysonge 2017; Wright 2009).

For the blood pressure and heart rate outcomes, the small but statistically significant greater reduction in SBP of 1.6 mmHg with first‐line thiazides compared to RAS inhibitors could have contributed to the improved outcomes with first‐line thiazides, but is unlikely to be the only explanation. The fact that BP is not the only explanation is demonstrated by the fact that first‐line beta‐blockers, which lowered HR and diastolic BP more than first‐line RAS inhibitors, had worse morbidity outcomes.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The number of trials and participants contributing to the three main comparisons in this review provide sufficient evidence regarding the outcomes that are important to patients to make first‐line thiazides the optimal first‐line drug for hypertension and to make RAS inhibitors the second best first‐line choice for hypertension. This result is based on moderate‐quality evidence demonstrating that first‐line thiazides decrease HF and stroke by about 1.7% over 4.9 years when compared to first‐line RAS inhibitors, meaning that for every 59 people treated for five years one event can be prevented. First‐line RAS inhibitors are the second best first‐line drug according to low‐quality evidence that first‐line RAS inhibitors reduce stroke by 1.7% compared to beta‐blockers and moderate‐quality evidence that they decrease overall CV events by 0.5% compared to CCBs, due to a reduction in HF events.

The evidence in this review is mostly relevant to primary prevention in patients, but is also relevant to people with hypertension and comorbidities such as T2DM, left ventricular hypertrophy, or diabetic nephropathy.

It is also important to note that the mortality and morbidity comparisons studied here involved predominately ACE inhibitors versus thiazides (ALLHAT 2002) and ARBs versus beta‐blockers (LIFE 2002). The comparison with CCBs involved both ACE inhibitors and ARBs. Subgroup comparisons based on either ACE inhibitors or ARBs compared to CCBs showed that the results were similar for HF and stroke. In addition, it is important to appreciate that in 12 of 17 studies using beta‐blockers, atenolol was the study drug, so that it is possible that the worse outcomes seen with beta‐blockers are limited to atenolol.

Sensitivity analysis

In this review, we used several analyses to test the robustness of the results. The specific sensitivity analyses done are described below.

Studies with reported standard deviations (SDs) of effect change versus those with imputed SDs

In this review, three studies did not report a within‐study variance for change in BP and we imputed SDs using the weighted mean SD from other trials (Esnault 2008; Fogari 2012; Roman 1998). When we excluded these three trials from the analysis, the BP estimates were not changed significantly.

Studies with a high risk of bias versus those with a low risk of bias

We judged four of the included studies that contributed data to the primary outcomes analyses to be at a high risk of 'other' bias (Estacio 1998; IDNT 2001; LIFE 2002; VALUE 2004). Three of these four studies compared RAS inhibitors with CCBs; their high risk of bias resulted from an unbalanced proportion of monotherapy and use of higher doses in one of the two treatment groups in the VALUE 2004 study, an unbalanced proportion of monotherapy in the Estacio 1998 study, and many authors receiving research grants form Bristol‐Myers Squibb in the IDNT 2001 study. When we dropped these three studies from the analysis, the results did not change significantly. Another high‐risk trial was funded and conducted by Merck (LIFE 2002), but this RCT was the only one providing data for the comparison of RAS inhibitors and beta‐blockers, and we therefore could not perform a sensitivity analysis.

In terms of the secondary outcomes (SBP, DBP and HR), when we excluded the studies with a high risk of other bias from the analysis in comparison of RAS inhibitors with CCBs (Pedersen 1997; VALUE 2004), the results did not change significantly. In the comparison of RAS inhibitors with beta‐blockers, when we dropped the studies with a high risk of other bias from the analysis (LIFE 2002; SILVHIA 2001), SBP decreased more in beta‐blockers (14 RCTs, MD 1.37, 95% CI 0.02 to 2.71) than with RAS inhibitors, with little clinical significance. The results did not change significantly in the comparison of RAS inhibitors with thiazides when we excluded Roman 1998 with a high risk of 'other' bias.

Potential biases in the review process

One potential bias that deserves attention is combination medication. For most long‐term and large‐scale studies, it is impossible to maintain single first‐line drug treatment, as a single drug frequently does not adequately lower the BP to an acceptable level. In most cases in the included studies, physicians were permitted to add other non‐study drugs to attempt to reach the target BP. In these RCTs and in this review, we hope that the add‐on drugs were balanced between the different treatment groups and, therefore, that any differences in outcomes were due to the first‐line drugs. The fact that we include only double‐blinded trials in this review decreases this possible bias, but there was no way of verifying that this was the case in all the trials. A potential limitation of this review is the possibility that there are differences in the effect of ACE inhibitors and ARBs on morbidity and mortality. This would have to be answered by specific head‐to‐head RCTs comparing the subclasses of drugs that inhibit the renin angiotensin system. A Cochrane Review comparing first‐line ACE inhibitors with first‐line ARBs suggests no difference in total mortality and total cardiovascular events (Li 2014), but more evidence is needed.

Unfortunately, there were not enough trials contributing to the primary outcomes to allow us to assess for publication bias. The BP and HR estimates cannot be used to estimate the BP‐lowering capacity of the first‐line drug, as other drugs could be added. The small statistically significant differences in BP lowering therefore cannot be entirely attributed to the first‐line drug. They may represent real differences in BP‐lowering capacity, but other systematic reviews specifically designed to assess BP will be needed to confirm these results.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

The results of comparison between RAS inhibitors and CCBs are in agreement with those in the Chen 2010 Cochrane Review for the outcomes of MI, stroke, HF, CV events, and all‐cause death, as well as SBP and DBP. Likewise, the results in this review for first‐line RAS inhibitors compared with first‐line beta‐blockers are similar to those reported by another review (Wiysonge 2017) for morbidity and mortality outcomes.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Compared to first‐line renin angiotensin system (RAS) inhibitors, first‐line thiazides reduce heart failure (HF) and stroke. Compared with calcium channel blockers (CCBs), RAS inhibitors reduce HF, but increase stroke; the magnitude of the reduction in HF outweighs the increase in stroke. The lower incidence of cardiovascular events and stroke that we found with RAS inhibitors relative to beta‐blockers may change with additional trials. In this updated review, only the data for blood pressure are changed by a small amount. The small differences in effect on blood pressure between the different classes of drugs did not necessarily correlate with the differences in the primary outcomes.

Implications for research.

Most of the data in this review come from the ALLHAT 2002 and LIFE 2002 trials. More large long‐term trials are needed to compare first‐line RAS inhibitors with other classes of drugs, particularly in subgroups of patients such as those with type 2 diabetes mellitus or early renal failure.

It is possible that first‐line angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers and renin inhibitors could have different mortality and morbidity outcomes, so more randomized controlled trials comparing them are needed.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 15 October 2018 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | This review includes an updated search conducted in November 2017. Three new studies met the inclusion criteria, making the number of included RCTs 45 in total. Three additional authors contributed to the update: Song Jia Yang, Qiu Ru and Li Qian. |

| 15 October 2018 | New search has been performed | No data for the primary outcomes were reported in the three new RCTs, so the evidence on all‐cause death, total CV events, total HF, total MI, total stroke and ESRF remain the same. Data on blood pressure were updated in the three main comparisons: RAS inhibitors versus CCBs, thiazides, and beta‐blockers. However, we found little change in blood pressure. In addition, data on heart rate were updated in the comparison of RAS versus beta‐blocker, with no change to that outcome either. The formerly "Ruggenenti 2004" trial was renamed "BENEDICT 2004" in this version, The abbreviation "BENEDICT" stands for "Bergamo Nephrologic Diabetes Complications Trial" and was given by the study group. We regard it necessary to make the change for the readers to identify this trial easier by its official abbreviation. |

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the help provided by the Cochrane Hypertension Group.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategies

Database: Ovid MEDLINE(R) 1946 to Present with Daily Update Search Date: 20 November 2017 ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 1 exp Angiotensin‐Converting Enzyme Inhibitors/ 2 ((angiotensin$ or dipeptidyl$ or kininase ii) adj3 (convert$ or enzyme or inhibit$ or recept$ or block$)).tw,kf. 3 (ace adj2 inhibit$).tw,kf. 4 acei.tw,kf. 5 (alacepril or altiopril or ancovenin or benazepril or captopril or ceranapril or ceronapril or cilazapril or deacetylalacepril or delapril or derapril or enalapril or enalaprilat or epicaptopril or fasidotril or fosinopril or foroxymithine or gemopatrilat or idapril or imidapril or indolapril or libenzapril or lisinopril or moexipril or moveltipril or omapatrilat or pentopril$ or perindopril$ or pivopril or quinapril$ or ramipril$ or rentiapril or saralasin or s nitrosocaptopril or spirapril$ or temocapril$ or teprotide or trandolapril$ or utibapril$ or zabicipril$ or zofenopril$ or Aceon or Accupril or Altace or Capoten or Lotensin or Mavik or Monopril or Prinivil or Univas or Vasotec or Zestril).tw,kf. 6 or/1‐5 7 exp Angiotensin Receptor Antagonists/ 8 (angiotensin adj3 (receptor antagon$ or receptor block$)).tw,kf. 9 (arb or arbs).tw,kf. 10 (abitesartan or azilsartan or candesartan or elisartan or embusartan or eprosartan or forasartan or irbesartan or KT3‐671 or losartan or milfasartan or olmesartan or saprisartan or tasosartan or telmisartan or valsartan or zolasartan).tw,kf. 11 or/7‐10 12 renin/ai 13 (aliskiren or ciprokiren or ditekiren or enalkiren or remikiren or rasilez or tekturna or terlakiren or zankiren).mp. 14 ((RAS or renin) adj2 inhibit$).tw,kf. 15 or/12‐14 16 6 or 11 or 15 17 exp calcium channel blockers/ 18 (amlodipine or aranidipine or barnidipine or bencyclane or benidipine or bepridil or cilnidipine or cinnarizine or clentiazem or darodipine or diltiazem or efonidipine or elgodipine or etafenone or fantofarone or felodipine or fendiline or flunarizine or gallopamil or isradipine or lacidipine or lercanidipine or lidoflazine or lomerizine or manidipine or mibefradil or nicardipine or nifedipine or niguldipine or nilvadipine or nimodipine or nisoldipine or nitrendipine or perhexiline or prenylamine or semotiadil or terodiline or tiapamil or verapamil or Cardizem CD or Dilacor XR or Tiazac or Cardizem Calan or Isoptin or Calan SR or Isoptin SR Coer or Covera HS or Verelan PM).tw,kf. 19 (calcium adj2 (antagonist? or block$ or inhibit$)).tw,kf. 20 or/17‐19 21 (methyldopa or alphamethyldopa or amodopa or dopamet or dopegyt or dopegit or dopegite or emdopa or hyperpax or hyperpaxa or methylpropionic acid or dopergit or meldopa or methyldopate or medopa or medomet or sembrina or aldomet or aldometil or aldomin or hydopa or methyldihydroxyphenylalanine or methyl dopa or mulfasin or presinol or presolisin or sedometil or sembrina or taquinil or dihydroxyphenylalanine or methylphenylalanine or methylalanine or alpha methyl dopa).mp. 22 (reserpine or serpentina or rauwolfia or serpasil).mp. 23 (clonidine or adesipress or arkamin or caprysin or catapres$ or catasan or chlofazolin or chlophazolin or clinidine or clofelin$ or clofenil or clomidine or clondine or clonistada or clonnirit or clophelin$ or dichlorophenylaminoimidazoline or dixarit or duraclon or gemiton or haemiton or hemiton or imidazoline or isoglaucon or klofelin or klofenil or m‐5041t or normopresan or paracefan or st‐155 or st 155 or tesno timelets).mp. 24 exp hydralazine/ 25 (dihydralazine or hydralazin$ or hydrallazin$ or hydralizine or hydrazinophtalazine or hydrazinophthalazine or hydrazinophtalizine or dralzine or hydralacin or hydrolazine or hypophthalin or hypoftalin or hydrazinophthalazine or idralazina or 1‐hydrazinophthalazine or apressin or nepresol or apressoline or apresoline or apresolin or alphapress or alazine or idralazina or lopress or plethorit or praeparat).tw,kf. 26 or/21‐25 27 exp adrenergic beta‐antagonists/ 28 (acebutolol or adimolol or afurolol or alprenolol or amosulalol or arotinolol or atenolol or befunolol or betaxolol or bevantolol or bisoprolol or bopindolol or bornaprolol or brefonalol or bucindolol or bucumolol or bufetolol or bufuralol or bunitrolol or bunolol or bupranolol or butofilolol or butoxamine or carazolol or carteolol or carvedilol or celiprolol or cetamolol or chlortalidone cloranolol or cyanoiodopindolol or cyanopindolol or deacetylmetipranolol or diacetolol or dihydroalprenolol or dilevalol or epanolol or esmolol or exaprolol or falintolol or flestolol or flusoxolol or hydroxybenzylpinodolol or hydroxycarteolol or hydroxymetoprolol or indenolol or iodocyanopindolol or iodopindolol or iprocrolol or isoxaprolol or labetalol or landiolol or levobunolol or levomoprolol or medroxalol or mepindolol or methylthiopropranolol or metipranolol or metoprolol or moprolol or nadolol or oxprenolol or penbutolol or pindolol or nadolol or nebivolol or nifenalol or nipradilol or oxprenolol or pafenolol or pamatolol or penbutolol or pindolol or practolol or primidolol or prizidilol or procinolol or pronetalol or propranolol or proxodolol or ridazolol or salcardolol or soquinolol or sotalol or spirendolol or talinolol or tertatolol or tienoxolol or tilisolol or timolol or tolamolol or toliprolol or tribendilol or xibenolol).tw,kf. 29 (beta adj2 (adrenergic? or antagonist? or block$ or receptor?)).tw,kf. 30 or/27‐29 31 exp adrenergic alpha antagonists/ 32 (alfuzosin or bunazosin or doxazosin or metazosin or neldazosin or prazosin or silodosin or tamsulosin or terazosin or tiodazosin or trimazosin).tw,kf. 33 (adrenergic adj2 (alpha or antagonist?)).tw,kf. 34 ((adrenergic or alpha or receptor?) adj2 block$).tw,kf. 35 or/31‐34 36 exp thiazides/ 37 exp sodium potassium chloride symporter inhibitors/ 38 ((loop or ceiling) adj diuretic?).tw,kf. 39 (amiloride or benzothiadiazine or bendroflumethiazide or bumetanide or chlorothiazide or cyclopenthiazide or furosemide or hydrochlorothiazide or hydroflumethiazide or methyclothiazide or metolazone or polythiazide or trichlormethiazide or veratide or thiazide?).tw,kf. 40 (chlorthalidone or chlortalidone or phthalamudine or chlorphthalidolone or oxodoline or thalitone or hygroton or indapamide or metindamide).tw,kf. 41 or/36‐40 42 hypertension/ 43 hypertens$.tw,kf. 44 ((high or elevat$ or rais$) adj2 blood pressure).tw,kf. 45 or/42‐44 46 randomized controlled trial.pt. 47 controlled clinical trial.pt. 48 randomized.ab. 49 placebo.ab. 50 drug therapy.fs. 51 randomly.ab. 52 trial.ab. 53 groups.ab. 54 or/46‐53 55 animals/ not (humans/ and animals/) 56 Pregnancy/ or Hypertension, Pregnancy‐Induced/ or Pregnancy Complications, Cardiovascular/ or exp Ocular Hypertension/ 57 (pregnancy‐induced or ocular hypertens$ or preeclampsia or pre‐eclampsia).ti. 58 54 not (55 or 56 or 57) 59 16 and 45 and 58 and (20 or 26 or 30 or 35 or 41)