Abstract

Background

Critical illness is associated with uncontrolled inflammation and vascular damage which can result in multiple organ failure and death. Antithrombin III (AT III) is an anticoagulant with anti‐inflammatory properties but the efficacy and any harmful effects of AT III supplementation in critically ill patients are unknown. This review was published in 2008 and updated in 2015.

Objectives

To examine:

1. The effect of AT III on mortality in critically ill participants.

2. The benefits and harms of AT III.

We investigated complications specific and not specific to the trial intervention, bleeding events, the effect on sepsis and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) and the length of stay in the intensive care unit (ICU) and in hospital in general.

Search methods

We searched the following databases from inception to 27 August 2015: Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE (Ovid SP), EMBASE (Ovid SP,), CAB, BIOSIS and CINAHL. We contacted the main authors of trials to ask for any missed, unreported or ongoing trials.

Selection criteria

We included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) irrespective of publication status, date of publication, blinding status, outcomes published, or language. We contacted the investigators and the trial authors in order to retrieve missing data. In this updated review we include trials only published as abstracts.

Data collection and analysis

Our primary outcome measure was mortality. Two authors each independently abstracted data and resolved any disagreements by discussion. We presented pooled estimates of the intervention effects on dichotomous outcomes as risk ratios (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). We performed subgroup analyses to assess risk of bias, the effect of AT III in different populations (sepsis, trauma, obstetrics, and paediatrics), and the effect of AT III in patients with or without the use of concomitant heparin. We assessed the adequacy of the available number of participants and performed trial sequential analysis (TSA) to establish the implications for further research.

Main results

We included 30 RCTs with a total of 3933 participants (3882 in the primary outcome analyses).

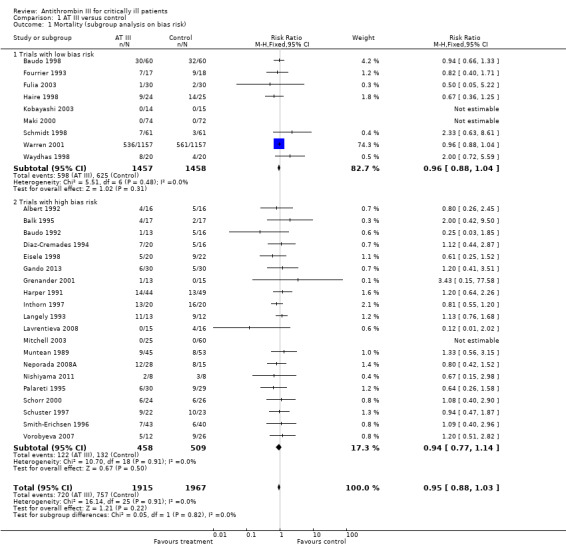

Combining all trials, regardless of bias, showed no statistically significant effect of AT III on mortality with a RR of 0.95 (95% CI 0.88 to 1.03), I² statistic = 0%, fixed‐effect model, 29 trials, 3882 participants, moderate quality of evidence). For trials with low risk of bias the RR was 0.96 (95% Cl 0.88 to 1.04, I² statistic = 0%, fixed‐effect model, 9 trials, 2915 participants) and for high risk of bias RR 0.94 (95% Cl 0.77 to 1.14, I² statistic = 0%, fixed‐effect model, 20 trials, 967 participants).

For participants with severe sepsis and DIC the RR for mortality was non‐significant, 0.95 (95% Cl 0.88 to 1.03, I² statistic = 0%, fixed‐effect model, 12 trials, 2858 participants, moderate quality of evidence).

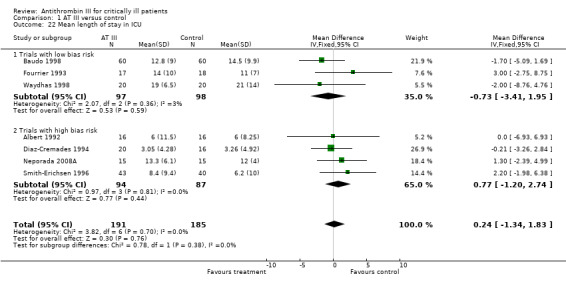

We conducted 14 subgroup and sensitivity analyses with respect to the different domains of risk of bias, but detected no statistically significant benefit in any subgroup analyses.

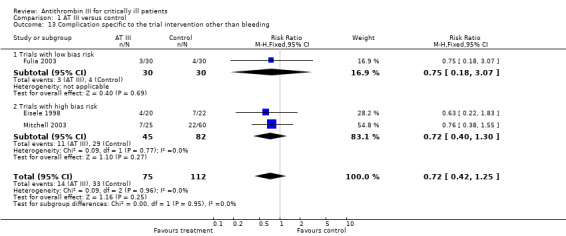

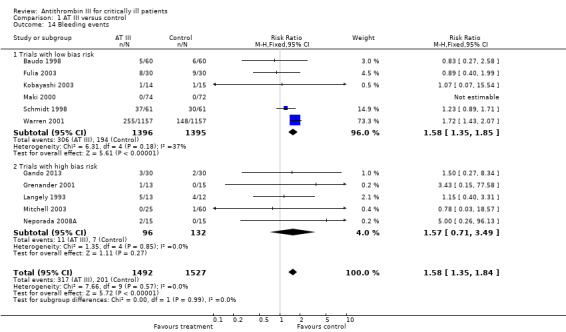

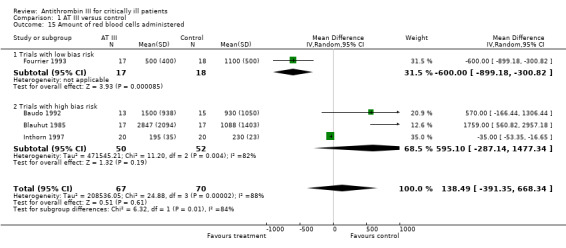

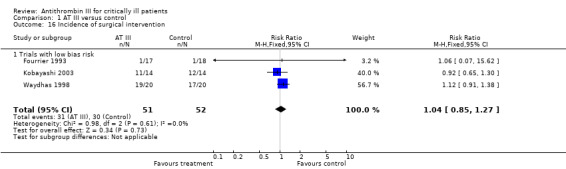

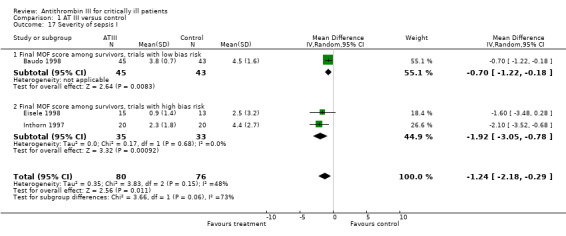

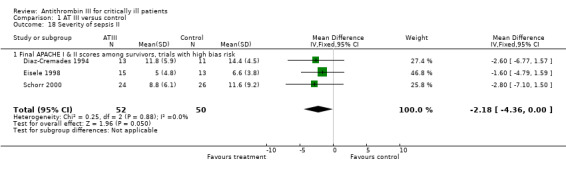

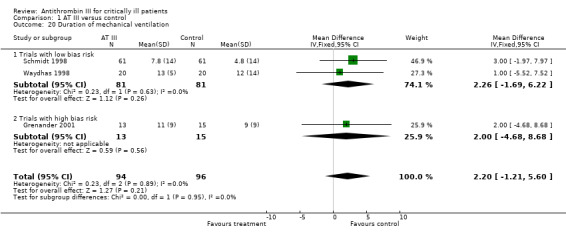

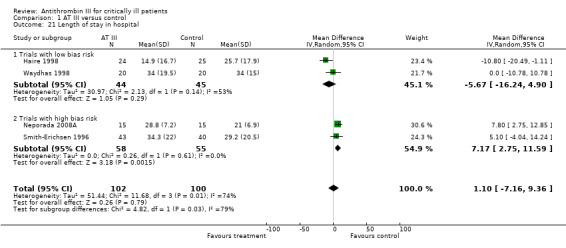

Our secondary objective was to assess the benefits and harms of AT III. For complications specific to the trial intervention the RR was 1.26 (95% Cl 0.83 to 1.92, I² statistic = 0%, random‐effect model, 3 trials, 2454 participants, very low quality of evidence). For complications not specific to the trial intervention, the RR was 0.71 (95% Cl 0.08 to 6.11, I² statistic = 28%, random‐effects model, 2 trials, 65 participants, very low quality of evidence). For complications other than bleeding, the RR was 0.72 ( 95% Cl 0.42 to 1.25, I² statistic = 0%, fixed‐effect model, 3 trials, 187 participants, very low quality of evidence). Eleven trials investigated bleeding events and we found a statistically significant increase, RR 1.58 (95% CI 1.35 to 1.84, I² statistic = 0%, fixed‐effect model, 11 trials, 3019 participants, moderate quality of evidence) in the AT III group. The amount of red blood cells administered had a mean difference (MD) of 138.49 (95% Cl ‐391.35 to 668.34, I² statistic = 84%, random‐effect model, 4 trials, 137 participants, very low quality of evidence). The effect of AT III in patients with multiple organ failure (MOF) was a MD of ‐1.24 (95% Cl ‐2.18 to ‐0.29, I² statistic = 48%, random‐effects model, 3 trials, 156 participants, very low quality of evidence) and for patients with an Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation score (APACHE) at II and III the MD was ‐2.18 (95% Cl ‐4.36 to ‐0.00, I² statistic = 0%, fixed‐effect model, 3 trials, 102 participants, very low quality of evidence). The incidence of respiratory failure had a RR of 0.93 (95% Cl 0.76 to 1.14, I² statistic = 32%, random‐effects model, 6 trials, 2591 participants, moderate quality of evidence). AT III had no statistically significant impact on the duration of mechanical ventilation (MD 2.20 days, 95% Cl ‐1.21 to 5.60, I² statistic = 0%, fixed‐effect model, 3 trials, 190 participants, very low quality of evidence); on the length of stay in the ICU (MD 0.24, 95% Cl ‐1.34 to 1.83, I² statistic = 0%, fixed‐effect model, 7 trials, 376 participants, very low quality of evidence) or on the length of stay in hospital in general (MD 1.10, 95% Cl ‐7.16 to 9.36), I² statistic = 74%, 4 trials, 202 participants, very low quality of evidence).

Authors' conclusions

There is insufficient evidence to support AT III substitution in any category of critically ill participants including the subset of patients with sepsis and DIC. We did not find a statistically significant effect of AT III on mortality, but AT III increased the risk of bleeding events. Subgroup analyses performed according to duration of intervention, length of follow‐up, different patient groups, and use of adjuvant heparin did not show differences in the estimates of intervention effects. The majority of included trials were at high risk of bias (GRADE; very low quality of evidence for most of the analyses). Hence a large RCT of AT III is needed, without adjuvant heparin among critically ill patients such as those with severe sepsis and DIC, with prespecified inclusion criteria and good bias protection.

Plain language summary

Antithrombin III for critically ill patients

Background

Antithrombin is a small particle produced by the liver. It deactivates several substances which affect the ability of the blood to form clots. Its activity is increased many‐fold by the drug heparin, which enhances the binding of antithrombin to clotting factors so that the blood does not form clots. Antithrombin also reduces inflammation in the human body. Inflammation is the body's attempt at self protection to remove harmful stimuli and begin healing processes. Inflammation is thus not always a bad process.

This updated review assessed the effects of antithrombin in people recovering from critical illness. Our primary goal was to investigate whether the number of people who died changed by giving antithrombin. We also investigated whether there were more complications among people treated with this drug, the extent of bleeding and the amount of blood given to the critical ill people. Finally we examined the impact of antithrombin on the duration of respiratory therapy, length of stay in the intensive care units and in the hospital in general.

Study characteristics

We included 30 trials with 3933 participants (3882 in our data calculation) in this updated review. We found the overall quality of trials to be poor, with little information on how the experiments were carried out. The results were limited and the included trials were mostly small. In most trials, there was a high risk of misleading information. Thus, the results must be interpreted with caution. The evidence is up to date to 27 August 2015.

Study funding sources

Three of the 30 included trials reported receiving money from drug companies.

Key results

In our review we could not identify a clear advantage of antithrombin for the objectives we examined, overall or among various types of patients or subgroups. In our investigation of bleeding events, however, we found an increased risk of bleeding for patients treated with antithrombin.

Quality of the evidence

Overall, there was a low quality of information from the studies regarding all of the results. We conclude that there is a need for a large‐scale clinical trial with low risk of misleading information to investigate the advantages and harms of this drug among critically ill patients.

Summary of findings

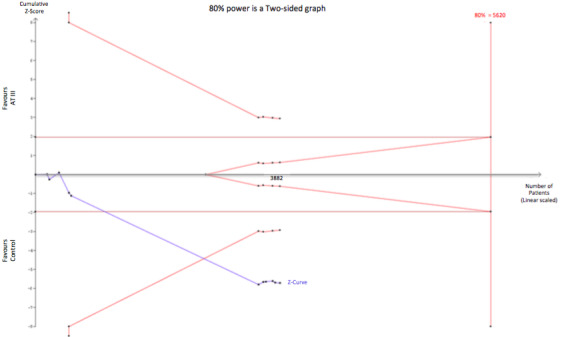

1.

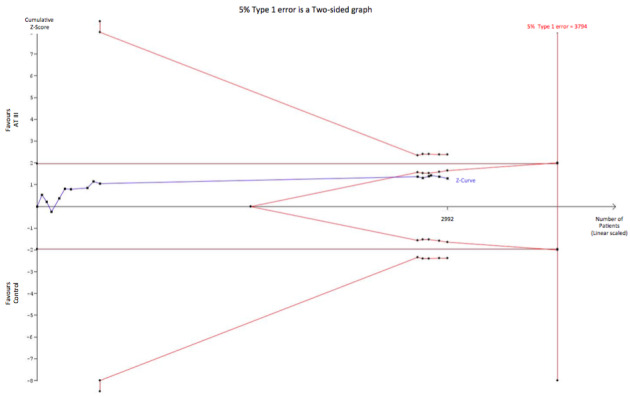

Trial sequential analysis of AT III vs placebo or no intervention on number of bleeding events. The Diversity (D‐square) is 0%, the control event proportion is 13.2% and the required information size is estimated for an anticipated relative risk increase of 20% with a type 1 and 2 error risk of 5% and 20% respectively. The cumulative Z‐curve is breaking through the trial sequential monitoring boundary for harm suggesting, even though the required information size has not been reached, that AT III increases the number of bleeding events. The TSA‐adjusted meta‐analysis yields a RR of 1.85 (95% CI 1.35 to 1.85).

Background

Description of the condition

Despite advances in the medical field, growing numbers of patients are becoming critically ill. Each year, 5,700,000 people in the USA are admitted to intensive care units (ICUs) (Wunsch 2008).

Critical illness is characterized by cellular immune dysfunction, vascular damage and uncontrolled hyperinflammation, even when the cause of illness is not infection. In critical illness, a systemic activation of coagulation may occur which, at its worst, results in a fulminant disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). DIC is characterized by simultaneous widespread microvascular thrombosis and profuse bleeding from various sites (Levi 2004). Sepsis resulting from a generalized inflammatory and procoagulant response to an infection is associated with a high risk of mortality. Twenty per cent of patients who develop severe sepsis will die during their hospitalization (Mayr 2014). Septic shock is associated with the highest mortality, approaching 50% (Mayr 2014). This rate increases in the presence of circulatory shock despite aggressive antimicrobial therapy, adequate fluid resuscitation, and optimal care (Periti 2000), and may reach as high as 70% in patients with multiple organ dysfunction (Polderman 2004).

The inflammation associated with critical illness is characterized by an increase in the number and activity of numerous molecules, such as platelet activating factor, von Willebrand factor, and tumour necrosis factor. There is a simultaneous increase in the activity of pro‐inflammatory and pro‐coagulant processes, such as thrombin formation, fibrin deposition at the vascular wall, and the formation of aggregates containing platelets and leukocytes. Leukocyte rolling, adhesion, and transmigration are also important parts of the inflammatory reaction. These processes lead to capillary leakage, severe disturbance of the microcirculation, tissue damage, and eventually multiorgan failure and death (Becker 2000).

Description of the intervention

Any proposed treatment of critical illness should aim to eliminate the underlying disorder or condition and to restore microvascular function, hence reducing organ dysfunction (Levi 2004).

Antithrombin III (AT III) is primarily a potent anticoagulant with independent anti‐inflammatory properties. AT III irreversibly inhibits serine proteases (for example, activated factor X and thrombin) in a one‐to‐one ratio, with the generation of protease‐AT III complexes. Heparin prevents AT III from interacting with the endothelial cell surface by binding to sites on the AT III molecule, competing for the AT III binding site, and reducing AT III ability to interact with its cellular receptor. AT III's anticoagulant effect is thus greatly accelerated (by a factor of 1000) by heparin; heparin reduces AT III's anti‐inflammatory properties, weakens vascular protection, and increases bleeding events (Diaz 2015; Opal 2002; Rublee 2003).

Heparin in patients with sepsis, septic shock, or DIC associated with infection may be associated with decreased mortality (Zarychanski 2015). However, the overall effect is still not clear. Major bleeding events related to heparin administration cannot be excluded (Zarychanski 2015) and safety outcomes have yet to be validated in a multicentre trial setting.

How the intervention might work

The blood concentration of AT III falls by 20% to 40% in septic patients, and these levels correlate with disease severity and clinical outcome (Opal 2002; Wiedermann 2002). This reduction in concentration is due to the combined effect of decreased production of AT III in the liver, inactivation by the enzyme elastase, which is increased during inflammation, and loss of AT III from the circulation into tissues through inflamed and leaking capillary blood vessels. These processes reduce the half‐life of AT III from a mean of 55 hours to 20 hours (Fourrier 2000). The main mechanism of AT III depletion in severe sepsis is linked to consumption of the molecule.

It is this depletion of AT III that has prompted research into the potential benefits of replenishing AT III levels. Investigators have often tried to increase the antithrombin concentration to supranormal values because the activity of pro‐inflammatory and pro‐coagulant molecules are increased in critically ill patients. Thus artificially high levels of AT III may be required to overcome the inhibitory effect of thrombin and other such serine proteases. This is because the normal serum concentration of AT III does not necessarily reflect the amount bound to endothelial receptors and appears insufficient (Fourrier 2000). Finally, by blocking the actions of thrombin, AT III may have anti‐angiogenic and antitumour properties (Larsson 2001).

Why it is important to do this review

Although critically ill patients are a heterogeneous population, they are characterized by having systemic inflammation, no matter what the cause of their illness. This inflammation causes further damage to tissues and organs and can result in multiple organ failure and death. The process of inflammation can be modified by AT III, whether or not clotting is abnormal, and it is possible that AT III can reduce the high death rate or permanent damage experienced by critically ill patients. The benefit of AT III supplementation in critically ill patients is still controversial and its efficacy is still debated (Tagami 2014; Tagami 2015).

Objectives

To examine:

The effect of AT III on mortality in critically ill participants.

The benefits and harms of AT III.

We investigated complications specific and not specific to the trial intervention, bleeding events, the effect on sepsis and DIC and the length of stay in ICU and in hospital in general.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) irrespective of publication status, date of publication, blinding status, outcomes published, or language. We contacted the investigators and the authors in order to retrieve relevant data. We included unpublished trials only if trial data and methodological descriptions were either provided in written form or could be retrieved from the trial authors. We excluded cross‐over trials. We include In this updated review trials published as abstracts (Balk 1995; Blauhut 1985; Muntean 1989; Palareti 1995; Schuster 1997).

Types of participants

We included critically ill participants as variously defined by the trial authors. However, we excluded trials of adjuvant AT III administration for the reduction of cardiovascular events in the invasive treatment of acute myocardial infarction.

The terminology for sepsis, as originally proposed by the American College of Chest Physicians and the Society of Critical Care Medicine, is in many ways outdated (Opal 2003). A loose definition of sepsis can easily result in enrolment of a heterogeneous population and hence in exaggerated findings, in either direction, that are difficult to reproduce. However, we accepted the various definitions of sepsis, septic shock, DIC, and other critical illnesses as proposed by the authors; we did not exclude any trial based on their definitions. We chose to accept the term 'standard treatment of sepsis and DIC' as reported by many authors, despite the lack of a generally accepted treatment regimen.

We classified two trials as obstetric trials (Kobayashi 2003; Maki 2000); four trials as paediatric trials (Fulia 2003; Mitchell 2003; Muntean 1989; Schmidt 1998); and a further two trials as trauma trials (Grenander 2001; Waydhas 1998).

Types of interventions

We included AT III versus no intervention or placebo. We included any dose of AT III, any duration of administration, and co‐interventions, but excluded trials that compared different doses of AT III.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Overall mortality (longest follow‐up, regardless of the period of follow‐up)

Secondary outcomes

Complications during the inpatient stay specific to the trial intervention, e.g. pneumonia, congestive cardiac failure, respiratory failure, myocardial infarction, renal failure, cerebrovascular accident

Complications during the inpatient stay not specific to the trial intervention, e.g. bleeding, limb venous thrombosis, line sepsis, local haematoma

Complications specific to the trial intervention other than bleeding

Bleeding events

Amount of red blood cells administered

Incidence of surgical intervention

Severity of sepsis (according to different organ dysfunction scores; sepsis versus septic shock if adequately defined by authors)

Incidence of respiratory failure not present at admission (mechanically‐assisted ventilation)

Duration of mechanical ventilation

Length of stay in hospital

Mean length of stay in the intensive care unit (ICU)

Overall mortality among patients with severe sepsis and DIC

We defined bleeding events (4) as intracranial bleeding or bleeding requiring transfusion of at least three units of blood. We counted repeated transfusions in the same participant as a singular event.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

In this updated review, we have further extended the original review's search from November 2006 (Afshari 2008). Thus, we searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2015, Issue 8). We updated our search of MEDLINE (Ovid SP, to 27 August 2015), EMBASE (Ovid SP, to 27 August 2015) and CINAHL (to 27 August 2015). The search is now from inception until 27 August 2015.

For specific information regarding our search strategies and results, please see Appendix 1.

Searching other resources

We searched for ongoing clinical trials and unpublished trials on the following Internet sites:

clinicaltrials.gov

We handsearched the reference lists of reviews, randomized and non‐randomized trials, and editorials for additional trials. We contacted the main authors of trials and experts in this field to ask for any missed, unreported, or ongoing studies. We applied no language restrictions to eligible reports. We conducted the latest search on 27 August 2015.

Data collection and analysis

Three review authors (FR, MA and AA) independently screened and classified all citations as potential primary studies, review articles or other. The three review authors also independently examined all potential primary studies and decided on their inclusion in the review. We evaluated all trials for major potential sources of bias (random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, intention‐to‐treat analysis, funding and completeness of follow‐up) (See Figure 2; Figure 3). We assessed each trial quality factor separately and defined the trials as having low risk of bias only if they adequately fulfilled all of the criteria. We independently abstracted and evaluated methodology and outcomes from each trial, in accordance with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We resolved disagreements by consensus among the review authors.

Selection of studies

We assessed the reports identified from the described searches and excluded obviously irrelevant reports. We screened all articles by title and abstract, and then as full‐text articles for inclusion. We list all excluded studies with reasons for their exclusion in the Characteristics of excluded studies

Two review authors (FR, MA) independently examined the retrieved reports for eligibility. We performed this process without blinding to study authors, institution, journal of publication or results. We resolved disagreements by consensus among the review authors. We provide a detailed description of the search and assessment.

Data extraction and management

We used the above strategy to search for relevant trials. We then screened the titles and abstracts in order to identify studies for eligibility. We independently extracted and collected the data on a standardized paper form. We were not blinded to the study author, source institution, or the publication source of trials. We resolved disagreements by discussion and approached all first authors of the included trials for additional information on risks of bias. For more detailed information please see the section Contributions of authors.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We evaluated the validity and design characteristics of each trial. We evaluated trials for major potential sources of bias (random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, intention‐to‐treat analysis, funding and completeness of follow‐up). We assessed each trial quality factor separately and defined the trials as having a low risk of bias only if they adequately fulfilled all of the criteria.

1. Random sequence generation

Assessment of randomization: sufficiency of the method in producing two comparable groups before intervention.

Grade: ’low risk’: a truly random process (e.g. random computer number generator, coin tossing, throwing dice); ’high risk’: any non‐random process (e.g. date of birth, date of admission by hospital or clinic record number or by availability of the intervention); or ’unclear risk’: insufficient information.

2. Allocation concealment

Allocation method prevented investigators or participants from foreseeing assignment.

Grade: ’low risk’: central allocation or sealed opaque envelopes; ’high risk’: using an open allocation schedule or other unconcealed procedure; or ’unclear risk’: insufficient information.

3. Blinding

Assessment of appropriate blinding of the team of investigators and participants: person responsible for participant care, participants and outcome assessors.

Grade: ’low risk’: blinding considered adequate if participants and personnel were kept unaware of intervention allocations after inclusion of participants into the study, and if the method of blinding involved a placebo indistinguishable from the intervention, as mortality is an objective outcome; ’high risk’: not double‐blinded, categorized as an open‐label study, or without use of a placebo indistinguishable from the intervention; ’unclear risk’: blinding not described.

4. Incomplete outcome data

Completeness of outcome data, including attritions and exclusions.

Grade: ’low risk’: numbers and reasons for dropouts and withdrawals in the intervention groups described, or no dropouts or withdrawals were specified; ’high risk’: no description of dropouts and withdrawals provided; ’unclear risk’: report gave the impression of no dropouts or withdrawals, but this was not specifically stated.

5. Selective reporting

The possibility of selective outcome reporting.

Grade: ’low risk’: reported outcomes prespecified in an available study protocol, or, if this is not available, published report includes all expected outcomes; ’high risk’: not all prespecified outcomes reported, reported using non‐prespecified subscales, reported incompletely or report fails to include a key outcome that would have been expected for such a study; ’unclear risk’: insufficient information.

6. Funding bias

Assessment of any possible funding bias.

Grade: ’low risk’: reported no funding, funding from universities or public institutions; ’high risk’: funding from private investors, pharmaceutical companies or trial investigator employed by the pharmaceutical company; ’unclear risk’: insufficient information.

7. Other bias

Assessment of any possible sources of bias not addressed in domains 1 to 6.

Grade: ’low risk’: report appears to be free of such biases; ’high risk’: at least one important bias is present that is related to study design, early stopping because of some data‐dependent process, extreme baseline imbalance, academic bias, claimed fraudulence or other problems; or ’unclear risk’: insufficient information or evidence that an identified problem will introduce bias.

Measures of treatment effect

We calculated risk ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for dichotomous data (binary outcomes). These included:

Primary outcomes:

Overall mortality (longest follow‐up, regardless of the period of follow‐up)

Secondary outcomes:

Complications during the inpatient stay specific to the trial intervention

Complications during the inpatient stay not specific to the trial intervention

Complications specific to the trial intervention other than bleeding

Bleeding events

Incidence of surgical intervention

Incidence of respiratory failure not present at admission

Overall mortality among patients with severe sepsis and DIC

We used the mean difference (MD) with a 95% confidence interval (CI), if data were continuous and measured in the same way between trials.

Amount of red blood cells administered

Severity of sepsis

Duration of mechanical ventilation

Length of stay in hospital

Mean length of stay in the ICU

Unit of analysis issues

Studies with multiple intervention groups

In accordance with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011), for trials with two or more groups receiving different doses, we combined data for the primary and secondary outcomes. We excluded trials that only compared different doses of AT III and did not have a control group, with or without placebo.

Dealing with missing data

We contacted the authors of trials with missing data in order to retrieve the relevant information. For all included studies we noted levels of attrition and any exclusions. In case of missing data, we chose ’complete‐case analysis’ for our primary outcomes, which excludes from the analysis all participants with the outcome missing.

Selective outcome reporting occurs when nonsignificant results are selectively withheld from publication (Chan 2004), and is defined as the selection, on the basis of the results, of a subset of the original variables recorded for inclusion in publication of trials (Hutton 2000). The most important types of selective outcome reporting are: selective omission of outcomes from reports; selective choice of data for an outcome; selective reporting of different analyses using the same data; selective reporting of subsets of the data and selective underreporting of data (Higgins 2011).

Assessment of heterogeneity

We explored heterogeneity using the I² statistic and Chi² test. An I² statistic above 50% represents substantial heterogeneity (Higgins 2011). In case of I² statistic > 0, we tried to determine the cause of heterogeneity by performing relevant subgroup analyses. We used the Chi² test to provide an indication of heterogeneity between studies, with a P value ≤ 0.1 considered significant.

Assessment of reporting biases

Funding bias is related to the possible publication delay or discouragement of undesired results in trials sponsored by the industry (Higgins 2011).

Data synthesis

Data analysis

We used Review Manager 5 software (RevMan 5.3). We calculated risk ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for dichotomous variables and mean difference (MD) with CI for continuous outcomes. We used the Chi² test to provide an indication of heterogeneity between studies, with a P value < 0.1 considered significant. The degree of heterogeneity observed in the results was quantified using the I² statistic, which can be interpreted as the proportion of the total variation observed between the studies that is attributable to differences between studies rather than to sampling error (Higgins 2002). An I² statistic > 75% is considered as very heterogeneous. We used both a random‐effects model and a fixed‐effect model. If the I² statistic = 0% we only reported the results from the fixed‐effect model, and in the case of I² statistic > 0% we reported only the results from the random‐effects model.

Trial sequential analysis

The risk of type 1 errors in meta‐analyses due to sparse data and repeated significance testing following updates with new trials remains a serious concern (Brok 2009; Thorlund 2009; Wetterslev 2008; Wetterslev 2009). As a result, spurious P values due to systematic errors from trials with high risk of bias, outcome reporting bias, publication bias, early stopping for benefit and small trial bias may result in false conclusions. In a single trial, interim analysis increases the risk of type 1 errors. In order to avoid type 1 errors, group sequential monitoring boundaries (Lan 1983) are used to decide whether a trial could be terminated early because of a sufficiently small P value; thus, the cumulative Z‐curve crosses the monitoring boundary.

Equally, sequential monitoring boundaries can be applied to meta‐analyses and are labelled ’trial sequential monitoring boundaries’ (TSMBs). In ’trial sequential analysis’ (TSA), the addition of each new trial in a cumulative meta‐analysis is viewed as an interim meta‐analysis, which provides useful information on the need for additional trials (Wetterslev 2008).

It is appropriate and wise to adjust new meta‐analyses for multiple testing on accumulating data to control the overall type 1 error risk in cumulative meta‐analysis (Pogue 1997; Pogue 1998; Thorlund 2009; Wetterslev 2008).

When using TSA, if the cumulative Z‐curve crosses the boundary, there is an indication of a sufficient level of evidence having been reached, and as a consequence one may conclude that no further trials may be needed. However, evidence is insufficient to allow a conclusion if the Z‐curve does not cross the boundary or does not surpass the required information size.

In order to construct the TSMBs, one needs a required information size which is calculated as the least number of participants required in a well‐powered single trial with low risk of bias (Brok 2009; Pogue 1998; Wetterslev 2008).

In this updated review, we adjusted the required information size for heterogeneity with the diversity adjustment factor (Wetterslev 2009). We applied TSA, as it prevents an increase in the risk of type 1 errors (20%). If the actual accrued information size was too small, we provided the required information size given the actual diversity (Wetterslev 2009)

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We conducted the following subgroup analyses:

The effect of AT III in participants given heparin (all types and doses) versus participants not given heparin

Comparing estimates of the pooled intervention effect in trials with low risk of bias to estimates from trials with high risk of bias (i.e. trials having at least one inadequate risk of bias component)

Duration of drug administration (up to one week, more than one week)

Completeness of follow‐up

Comparing the pooled intervention effect in trials with a follow‐up that was longer than the median follow‐up with trials having a follow‐up equal to or shorter than the median follow‐up of trial participants. This was in order to detect a possible dependency of the estimate of intervention effect with length of follow‐up

The effect of AT III in the trauma population

The effect of AT III in obstetrics (eclampsia, pre‐eclampsia)

The effect of AT III in paediatrics (we defined an age below 18 years for our inclusion criteria)

The effect of AT III in sepsis and DIC

If analyses of various subgroups were significant, we performed a test of interaction (Altman 2003). We considered P values < 0.05 as indicating significant interaction between the AT III effect and subgroup category.

We included entire trials for subgroup analysis of trauma, obstetric, and paediatric participants.

Sensitivity analysis

We decided to carry out a sensitivity analysis on the results by applying fixed‐effect and random‐effects models to assess the impact of heterogeneity on our results.

Summary of findings

We used the principles of the GRADE approach to provide an overall assessment of the evidence relating to all of our outcomes. We constructed a 'Summary of findings' table using the GRADEpro software. As outcomes of public interest, we chose to present: mortality, bleeding events, incidence of respiratory failure not present at admission, duration of mechanical ventilation, length of stay in hospital, mean length of stay in ICU and overall mortality among patients with severe sepsis and DIC (see Table 1).

for the main comparison.

| AT III compared to control for critically ill patients | ||||||

|

Setting: Worldwide

Intervention: AT III

Comparison: Control Patient or population: critically ill participants | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with control | Risk with AT III | |||||

| Mortality (subgroup analysis on bias risk) | Study population | RR 0.95 (0.88 to 1.03) | 3882 (29 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1,2 | 9 trials had low risk of bias, 20 trials high risk of bias. Trial sequential analysis (TSA) adjusted RR 0.95 (95% CI 0.87 to 1.04). |

|

| 385 per 1000 | 366 per 1000 (339 to 396) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 310 per 1000 | 295 per 1000 (273 to 320) | |||||

| Bleeding events | Study population | RR 1.58 (1.35 to 1.84) | 3019 (11 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate3 |

6 trials had low risk of bias, 5 trials high risk of bias. Based on the TSA analysis, there seem to be evidence indicating that AT III increases risk of bleeding (Figure 1). TSA adjusted meta‐analysis yields a RR of 1.85 (95% CI 1.35 to 1.85). | |

| 385 per 1000 | 366 per 1000 (339 to 396) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 67 per 1000 | 102 per 1000 (87 to 119) | |||||

| Incidence of respiratory failure not present at admission | Study population | RR 0.93 (0.76 to 1.14) | 2591 (6 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1,4 | 5 trials had low risk of bias, 1 trial high risk of bias. | |

| 106 per 1000 | 98 per 1000 (80 to 120) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 317 per 1000 | 294 per 1000 (241 to 361) | |||||

| Duration of mechanical ventilation | The mean duration of mechanical ventilation in the intervention group was 2.2 more (1.21 fewer to 5.6 more) | ‐ | 190 (3 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low5 | 2 trials had low risk of bias, 1 trial high risk of bias | |

| Length of stay in hospital | The mean length of stay in hospital in the intervention group was 1.1 more (7.16 fewer to 9.36 more) | ‐ | 202 (4 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low6 | 2 trials had low risk of bias, 2 trials high risk of bias | |

| Mean length of stay in ICU | The mean length of stay in ICU in the intervention group was 0.24 more (1.34 fewer to 1.83 more) | ‐ | 376 (7 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,7 | 3 trials had low risk of bias, 4 trials high risk of bias | |

| Overall mortality among patients with severe sepsis & DIC | Study population |

RR 0.95 (0.88 to 1.03) |

2858 (12 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,8 | 4 trials had low risk of bias, 8 trials high risk of bias | |

| 462 per 1000 | 439 per 1000 (407 to 476) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 392 per 1000 | 372 per 1000 (345 to 404) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1With the exception of Baudo 1998; Fourrier 1993; Fulia 2003; Kobayashi 2003; Maki 2000; Schmidt 1998; Warren 2001; Waydhas 1998 there was a high risk of bias in all trials.

2The entry refers to trials in Analysis 1.1. The outcome was downgraded two levels because of the substantial number of trials with high risk of bias but TSA led to an upgrade of one level to moderate quality of evidence, indicating no benefit for survival. The choice for this TSA upgrade was based on increased precision with continuity correction for zero event trials, adjustment for the risk of random error, a calculation of the required information size leading to rejection of an intervention effect of a RRR of 10% with a power of 80% in 30 randomized trials.

3The entry refers to trials in Analysis 1.14. The outcome was downgraded from high to moderate quality of evidence because majority of trials had high risk of bias.

4The entry refers to trials in Analysis 1.19. The outcome was downgraded from high to moderate quality of evidence since one large trial provided most of the data (Warren 2001).

5The entry refers to trials in Analysis 1.20. The outcome was downgraded from high to very low quality of evidence because of a small number of trials, high risk of bias, a small numbers of participants and imprecision of results with a wide confidence interval.

6The entry refers to trials in Analysis 1.21. The outcome was downgraded from high to very low quality of evidence because of a small number of trials, high risk of bias, a small numbers of participants and imprecision of results with a wide confidence interval.

7The entry refers to trials in Analysis 1.22. The outcome was downgraded from high to very low quality of evidence because of a small number of trials, most of them with high risk of bias.

8The entry refers to trials in Analysis 1.10. The outcome was downgraded from high to very low quality of evidence because of numerous trials with high risk of bias. The vast majority of trials were small and poorly described.

Results

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; Characteristics of studies awaiting classification; Characteristics of ongoing studies

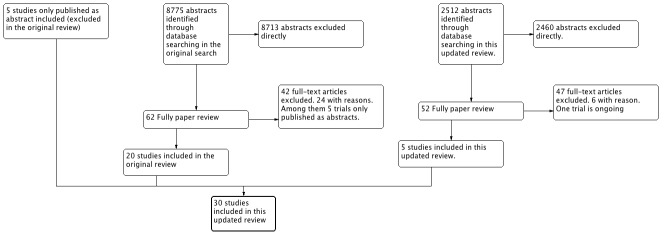

Results of the search

Through electronic searches and from reading the references of potentially relevant articles, we identified 11287 publications on AT III (see Figure 2). After reading the abstracts, we could directly exclude 11,173 publications. We retrieved 65 relevant publications for further assessment. From these 65 publications, we included 30 (Albert 1992; Balk 1995; Baudo 1992; Baudo 1998; Blauhut 1985; Diaz‐Cremades 1994; Eisele 1998; Fourrier 1993; Fulia 2003; Gando 2013; Grenander 2001; Haire 1998; Harper 1991; Inthorn 1997; Kobayashi 2003; Langely 1993; Lavrentieva 2008; Maki 2000; Mitchell 2003; Muntean 1989; Neporada 2008A; Nishiyama 2011; Palareti 1995; Schmidt 1998; Schorr 2000; Schuster 1997; Smith‐Erichsen 1996; Vorobyeva 2007; Warren 2001; Waydhas 1998), which randomized a total of 3933 participants. One trial (Blauhut 1985) was only published as an abstract and the data were so inadequate that they could not be used for further processing. Our analyses include a total of 3882 participants. The sample size varied from 16 to 2314 participants. We excluded 24 publications for the reasons detailed in the Characteristics of excluded studies. We found one ongoing trial (D'angelo 2005) but no data were provided for this trial (see Characteristics of ongoing studies).

2.

Flow

One trial was published in Russian only (Vorobyeva 2007), and one excluded trial was in German (Angstwurm 2009, a secondary publication of Warren 2001). We had these studies translated into English. Five trials had multiple full‐text publications or published post hoc subgroup analyses (Inthorn 1997; Maki 2000; Mitchell 2003; Neporada 2008A; Warren 2001).

In this updated review, we also included trials that were only published as abstracts in order to avoid publication bias (Balk 1995; Blauhut 1985; Muntean 1989; Palareti 1995; Schuster 1997).

Types of participants

We classified two trials as obstetric studies (Kobayashi 2003; Maki 2000); four trials as paediatric trials (Fulia 2003; Mitchell 2003; Muntean 1989; Schmidt 1998); and a further two trials as trauma studies (Grenander 2001; Waydhas 1998). The remaining trials consisted of mixed populations of critically ill participants, mainly with sepsis.

Types of interventions

The duration of the intervention varied from less than 24 hours to four weeks. Three trials had a median duration of AT III intervention that was longer than one week (Inthorn 1997; Mitchell 2003; Smith‐Erichsen 1996). Follow‐up ranged from seven to 90 days.

Included studies

The 30 included trials were all published between 1985 and 2013. Five trials of AT III were multicentre trials (Baudo 1998; Eisele 1998; Gando 2013; Mitchell 2003; Warren 2001). Five trials of AT III were multinational trials including Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands, Canada and the USA (Baudo 1992; Eisele 1998; Gando 2013; Mitchell 2003; Warren 2001). One trial was carried out in 19 countries (Warren 2001). Two trials did not state the location (Blauhut 1985; Palareti 1995).

The 30 included trials involved a total of 3933 participants. The details of the included studies are provided in the table Characteristics of included studies.

Fourteen trials recruited more male than female participants (Baudo 1998; Diaz‐Cremades 1994; Eisele 1998; Fourrier 1993; Fulia 2003; Gando 2013; Grenander 2001; Inthorn 1997; Lavrentieva 2008; Mitchell 2003; Nishiyama 2011; Smith‐Erichsen 1996; Warren 2001; Waydhas 1998). One trial recruited only men (Baudo 1992), two trials recruited only women (Kobayashi 2003; Maki 2000), six did not report the gender of the participants (Blauhut 1985; Harper 1991; Neporada 2008A; Palareti 1995; Schuster 1997; Vorobyeva 2007) and two studies had more female than male participants (Balk 1995; Haire 1998). The age of the participants included extends from the premature infant to the elderly intensive‐care participant. It therefore makes little sense to calculate the average age of the participants included. One trial however, excluded participants older than 75 (Neporada 2008A).

Eighteen trials used an initial loading dose either based on weight (u/kg) or as a fixed dose (Albert 1992; Baudo 1992; Diaz‐Cremades 1994; Eisele 1998; Fourrier 1993; Fulia 2003; Grenander 2001; Haire 1998; Harper 1991; Inthorn 1997; Langely 1993; Palareti 1995; Schmidt 1998; Schorr 2000; Schuster 1997; Smith‐Erichsen 1996; Vorobyeva 2007; Warren 2001). All trials except two (Balk 1995; Blauhut 1985) stated the use of a maintenance dose. Nine trials used albumin as the control intervention (Baudo 1998; Diaz‐Cremades 1994; Fourrier 1993; Haire 1998; Maki 2000; Schmidt 1998; Schuster 1997; Warren 2001; Waydhas 1998); two trials used fresh frozen plasma as the control intervention (Neporada 2008A; Vorobyeva 2007); three trials only stated the use of an unknown placebo (Balk 1995; Eisele 1998; Kobayashi 2003). Nine trials used no placebo (Albert 1992; Baudo 1992; Grenander 2001; Harper 1991; Inthorn 1997; Langely 1993; Mitchell 2003; Schorr 2000; Smith‐Erichsen 1996). Four trials did not state which control they applied (Baudo 1998; Gando 2013; Lavrentieva 2008; Palareti 1995).

Excluded studies

We excluded 24 randomized trials (Aibiki 2006; Dietrich 2013; Doi 2012; Hoffmann 2010; Ilias 2000; Jochum 1995; Kanbak 2011; Kim 2013; Korninger 1987; Leitner 2006; Maki 1987; Mayumi 2011; Neporada 2008B; Nishiyama 2006; Paparella 2014; Paternoster 2000; Paternoster 2004; Ranucci 2013; Sawamura 2009; Scherer 1997; Shimada 1994; Terao 1989; Valsecchi 2008; Vinazzer 1995), for the reasons detailed in the Characteristics of excluded studies.

Ongoing studies

One trial is stated to be ongoing (D'angelo 2005); see the Characteristics of ongoing studies

Awaiting classification

No studies are awaiting classification.

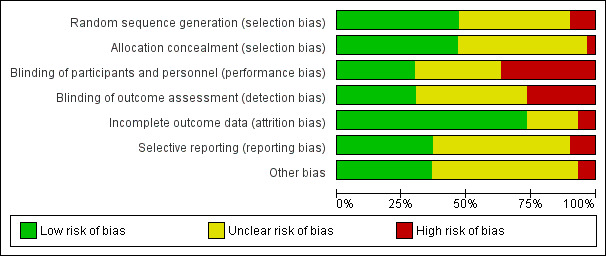

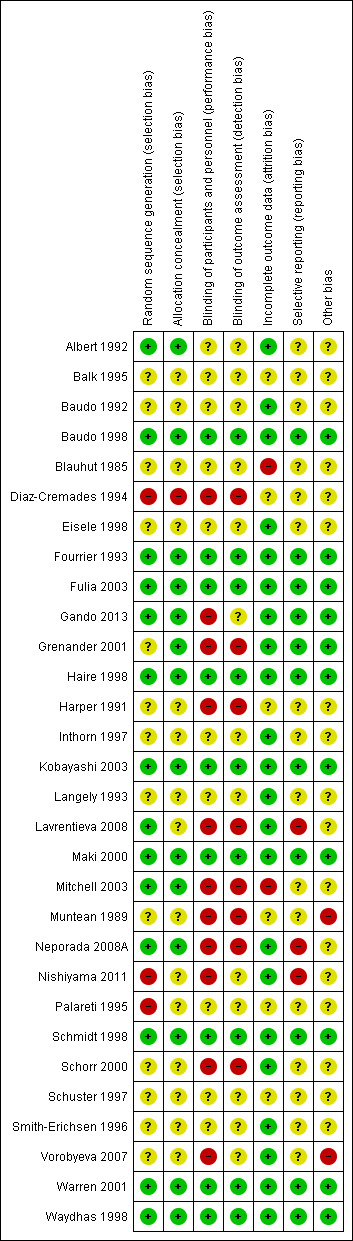

Risk of bias in included studies

All of the included studies were randomized controlled trials. However, the risk of bias of the included studies was high (Figure 3). The trials often failed to report trial methodology in sufficient detail. See Characteristics of included studies.

3.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included trials.

Allocation

Generation of allocation sequence was adequately reported in 15 trials (Albert 1992; Baudo 1998; Fourrier 1993; Fulia 2003; Gando 2013; Grenander 2001; Haire 1998; Kobayashi 2003; Lavrentieva 2008; Maki 2000; Mitchell 2003; Neporada 2008A; Schmidt 1998; Warren 2001; Waydhas 1998) (Figure 4).

4.

Risk of bias graph summarized

Allocation concealment was adequately reported in 14 trials (Albert 1992; Baudo 1998; Fourrier 1993; Fulia 2003; Gando 2013; Grenander 2001; Haire 1998; Kobayashi 2003; Maki 2000; Mitchell 2003; Neporada 2008A; Schmidt 1998; Warren 2001; Waydhas 1998) (Figure 4).

Blinding

Nine trials provided sufficient data to be categorized as double‐blinded (Baudo 1998; Fourrier 1993; Fulia 2003; Haire 1998; Kobayashi 2003; Maki 2000; Schmidt 1998; Warren 2001; Waydhas 1998). The remaining 21 trials were either open‐label or did not provide sufficient data on how the double‐blinding was achieved (Figure 4).

Incomplete outcome data

Two trials did not provide sufficient data (high risk) on follow‐up (Blauhut 1985; Mitchell 2003). Six trials did not provide any data on follow‐up (unclear risk) (Balk 1995; Diaz‐Cremades 1994; Harper 1991; Muntean 1989; Palareti 1995; Schuster 1997). Twenty‐two trials had adequate follow‐up (low risk) (Albert 1992; Baudo 1992; Baudo 1998; Eisele 1998; Fourrier 1993; Fulia 2003; Gando 2013; Grenander 2001; Haire 1998; Inthorn 1997; Kobayashi 2003; Langely 1993; Lavrentieva 2008; Maki 2000; Neporada 2008A; Nishiyama 2011; Schmidt 1998; Schorr 2000; Smith‐Erichsen 1996; Vorobyeva 2007; Warren 2001; Waydhas 1998).

Selective reporting

Ten trials provided adequate information to be classified as low‐risk trials (Baudo 1998; Fourrier 1993; Fulia 2003; Gando 2013; Grenander 2001; Kobayashi 2003; Maki 2000; Schmidt 1998; Warren 2001; Waydhas 1998). This was often due to supplementary information provided based on online registration, protocol availability or authors providing supplementary information while responding to our questions.

Eighteen trials did not provide sufficient data on selective reporting (unclear risk) (Albert 1992; Balk 1995; Baudo 1992; Blauhut 1985; Diaz‐Cremades 1994; Eisele 1998; Grenander 2001; Haire 1998; Harper 1991; Inthorn 1997; Langely 1993; Mitchell 2003; Muntean 1989; Palareti 1995; Schorr 2000; Schuster 1997; Smith‐Erichsen 1996; Vorobyeva 2007).

Three trials had substantial methodological shortcomings across multiple domains of bias (Lavrentieva 2008; Neporada 2008A; Nishiyama 2011).

Other potential sources of bias

Fourteen trials performed analysis according to the intention‐to‐treat (ITT) method or provided sufficient data for us to perform ITT analyses (Baudo 1992; Eisele 1998; Fourrier 1993; Fulia 2003; Haire 1998; Harper 1991; Inthorn 1997; Kobayashi 2003; Langely 1993; Maki 2000; Schmidt 1998; Schorr 2000; Warren 2001; Waydhas 1998).

Eight trials reported sample size calculations (Baudo 1998; Fourrier 1993; Haire 1998; Inthorn 1997; Kobayashi 2003; Mitchell 2003; Schmidt 1998; Warren 2001).

Three trials (Grenander 2001; Langely 1993; Warren 2001) reported receiving pharmaceutical company funding.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Primary outcomes

1. Overall mortality (longest follow‐up, regardless of the period of follow‐up)

Combining all trials showed no statistically significant effect of AT III on mortality, with a risk ratio (RR) of 0.95 (95% CI 0.88 to 1.03, I² statistic = 0%, P value = 0.91), based on data from 3882 participants in 29 trials. Results were analysed using a fixed‐effect model because heterogeneity was low. We downgraded the outcome from high to moderate quality of evidence because of 20 trials with high risk of bias. However, trial sequential analysis (TSA) led us to upgrade the overall assessment. Equally, for trials with only low risk of bias (Baudo 1998; Fourrier 1993; Fulia 2003; Haire 1998; Kobayashi 2003; Maki 2000; Schmidt 1998; Warren 2001; Waydhas 1998) we found no statistically significant effect; RR 0.96 (95% 0.88 to 1.04, I² statistic = 0%, fixed‐effect model, 9 trials, 2915 participants). Trials with only high risk of bias (Albert 1992; Balk 1995; Baudo 1992; Diaz‐Cremades 1994; Eisele 1998; Gando 2013; Grenander 2001; Harper 1991; Inthorn 1997; Langely 1993; Lavrentieva 2008; Mitchell 2003; Muntean 1989; Neporada 2008A; Nishiyama 2011; Palareti 1995; Schorr 2000; Schuster 1997; Smith‐Erichsen 1996; Vorobyeva 2007) had a non‐significant RR of 0.94 (95% CI 0.77 to 1.14, I² statistic = 0%, fixed‐effect model, 20 trials, 967 participants) (Analysis 1.1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 AT III versus control, Outcome 1 Mortality (subgroup analysis on bias risk).

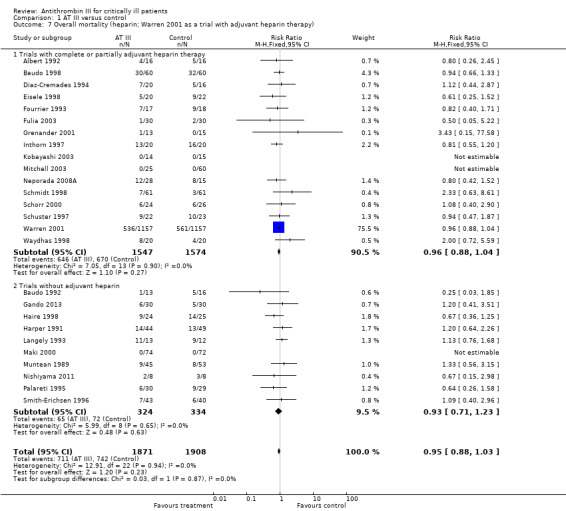

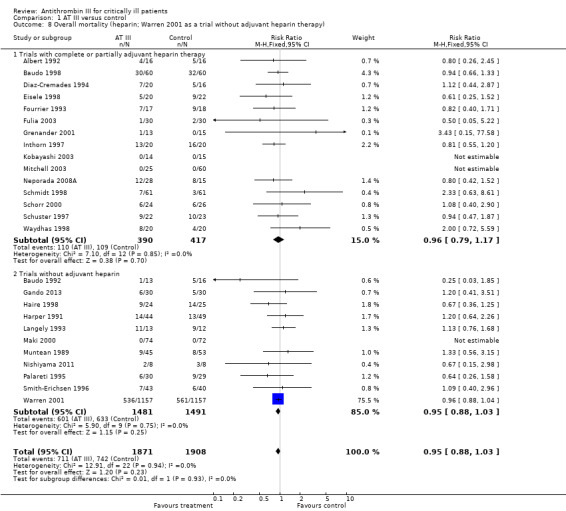

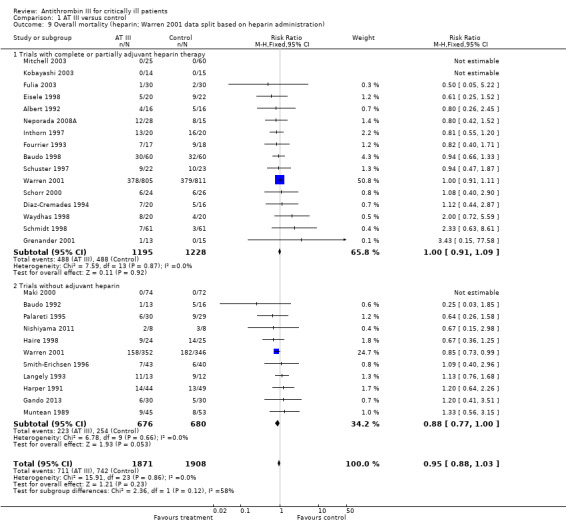

We conducted three subgroup analyses concerning the use of heparin (Analysis 1.7; Analysis 1.8; Analysis 1.9), but detected no statistically significant effects between the groups.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 AT III versus control, Outcome 7 Overall mortality (heparin; Warren 2001 as a trial with adjuvant heparin therapy).

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 AT III versus control, Outcome 8 Overall mortality (heparin; Warren 2001 as a trial without adjuvant heparin therapy).

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 AT III versus control, Outcome 9 Overall mortality (heparin; Warren 2001 data split based on heparin administration).

We carried out 15 subgroup and sensitivity analyses in regard to our primary outcome, and found no statistically significant effect in any of them (Analysis 1.1; Analysis 1.2; Analysis 1.3; Analysis 1.4; Analysis 1.5; Analysis 1.6; Analysis 1.7; Analysis 1.8; Analysis 1.9; Analysis 1.10; Table 2).

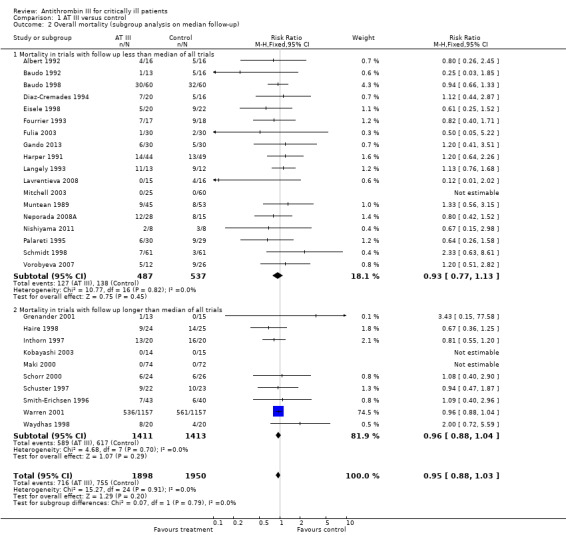

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 AT III versus control, Outcome 2 Overall mortality (subgroup analysis on median follow‐up).

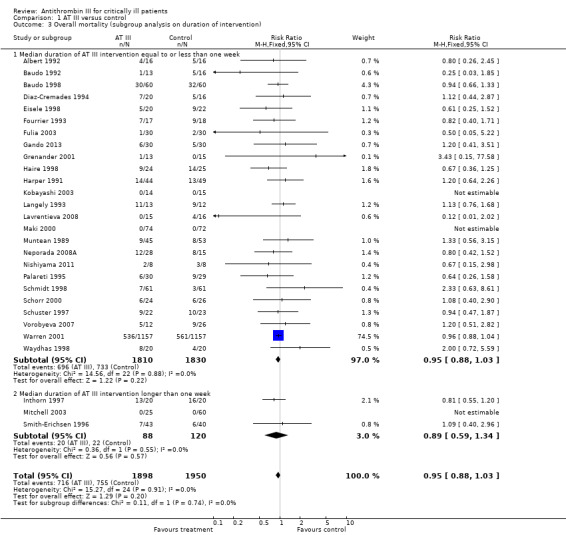

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 AT III versus control, Outcome 3 Overall mortality (subgroup analysis on duration of intervention).

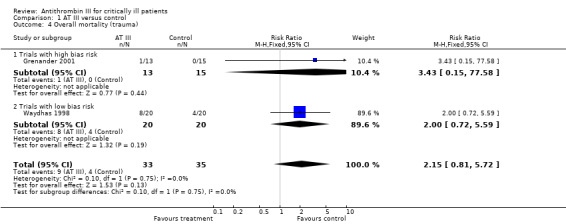

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 AT III versus control, Outcome 4 Overall mortality (trauma).

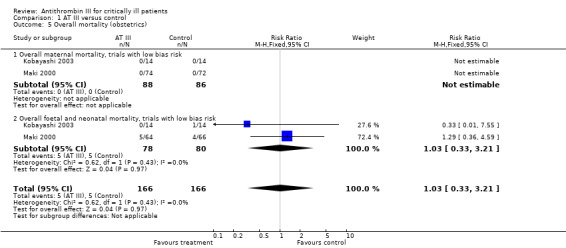

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 AT III versus control, Outcome 5 Overall mortality (obstetrics).

1.6. Analysis.

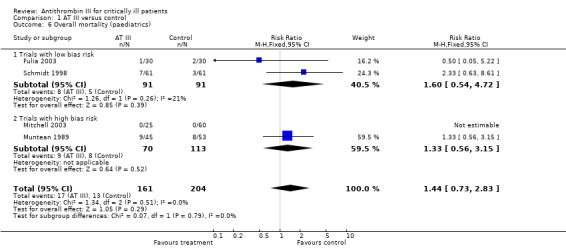

Comparison 1 AT III versus control, Outcome 6 Overall mortality (paediatrics).

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 AT III versus control, Outcome 10 Overall mortality among patients with severe sepsis & DIC.

1. Subgroup analysis (Overall mortality).

| AT III n/N |

Control n/N |

Low risk of bias trials RR (95% CI) |

High risk of bias trials RR (95% CI) |

Overall RR (95% CI) | Heterogeneity | |

| Overall mortality (subgroup analysis on random sequence generation)1 | 720/1915 | 757/1967 | 0.95 (0.88 to 1.03) | 0.98 (0.79 to 1.21) | 0.95 (0.88 to 1.03) | I² = 0% |

| Overall mortality (subgroup analysis on allocation concealment)2 | 720/1915 | 757/1967 | 0.96 (0.88 to 1.04) | 0.93 (0.75 to 1.15) | 0.95 (0.88 to 1.03) | I² = 0% |

| Overall mortality (subgroup analysis on blinding)3 | 720/1915 | 757/1967 | 0.96 (0.88 to 1.04) | 0.94 (0.77 to 1.14) | 0.95 (0.88 to 1.03) | I² = 0% |

| Overall mortality (subgroup analysis on completeness of follow‐up)4 | 720/1915 | 757/1967 | 0.95 (0.88 to 1.02) | 1.08 (0.77 to 1.51) | 0.95 (0.88 to 1.03) | I² = 0% |

| Overall mortality (subgroup analysis on ITT)5 | 705/1856 | 736/1895 | 0.98 (0.79 to 1.22) | 0.95 (0.88 to 1.03) | 0.95 (0.88 to 1.03) | I² = 0% |

1Low risk of bias trials (adequate random sequence generation): Albert 1992; Baudo 1998; Fourrier 1993; Fulia 2003; Gando 2013; Haire 1998; Kobayashi 2003; Lavrentieva 2008; Maki 2000; Mitchell 2003; Neporada 2008A; Schmidt 1998; Warren 2001; Waydhas 1998. High risk of bias trials (inadequate or unclear random sequence generation): Balk 1995; Baudo 1992; Diaz‐Cremades 1994; Eisele 1998; Grenander 2001; Harper 1991; Inthorn 1997; Langely 1993; Muntean 1989; Nishiyama 2011; Palareti 1995; Schorr 2000; Schuster 1997; Smith‐Erichsen 1996; Vorobyeva 2007.

2Low risk of bias trials (adequate allocation concealment): Albert 1992; Baudo 1998; Fourrier 1993; Fulia 2003; Gando 2013; Grenander 2001; Haire 1998; Kobayashi 2003; Maki 2000; Mitchell 2003; Neporada 2008A; Schmidt 1998; Warren 2001; Waydhas 1998. High risk of bias trials (inadequate or unclear allocation concealment): Balk 1995; Baudo 1992; Diaz‐Cremades 1994; Eisele 1998; Harper 1991; Inthorn 1997; Langely 1993; Lavrentieva 2008; Muntean 1989; Nishiyama 2011; Palareti 1995; Schorr 2000; Schuster 1997; Smith‐Erichsen 1996; Vorobyeva 2007

3Low risk of bias trials (blinded): Baudo 1998; Fourrier 1993; Fulia 2003; Haire 1998; Kobayashi 2003; Maki 2000; Schmidt 1998; Warren 2001; Waydhas 1998. High risk of bias trials (not blinded or unclear blinding): Albert 1992; Balk 1995; Baudo 1992; Diaz‐Cremades 1994; Eisele 1998; Gando 2013; Grenander 2001; Harper 1991; Inthorn 1997; Langely 1993; Lavrentieva 2008; Mitchell 2003; Muntean 1989; Neporada 2008A; Nishiyama 2011; Palareti 1995; Schorr 2000; Schuster 1997; Smith‐Erichsen 1996; Vorobyeva 2007

4Low risk of bias trials (complete follow‐up): Balk 1995; Diaz‐Cremades 1994; Harper 1991; Mitchell 2003; Muntean 1989; Palareti 1995; Schuster 1997. High risk of bias trials (absence of complete follow‐up): Albert 1992; Baudo 1992; Baudo 1998; Eisele 1998; Fourrier 1993; Fulia 2003; Gando 2013; Grenander 2001; Haire 1998; Inthorn 1997; Kobayashi 2003; Langely 1993; Maki 2000; Neporada 2008A; Nishiyama 2011; Schmidt 1998; Schorr 2000; Smith‐Erichsen 1996; Vorobyeva 2007; Warren 2001; Waydhas 1998.

5Low risk of bias trials (ITT): Baudo 1992; Eisele 1998; Fourrier 1993; Fulia 2003; Gando 2013; Haire 1998; Harper 1991; Inthorn 1997; Langely 1993; Maki 2000; Schmidt 1998; Schorr 2000; Smith‐Erichsen 1996; Warren 2001; Waydhas 1998. High risk of bias trials (no ITT): Albert 1992; Baudo 1998; Diaz‐Cremades 1994; Grenander 2001; Kobayashi 2003; Lavrentieva 2008; Mitchell 2003; Muntean 1989; Neporada 2008A; Nishiyama 2011; Schuster 1997.

Secondary outcomes

Summarized in Table 3

2. Secondary outcomes; refers to 'Data and analyses' 1.11; 1.12; 1.13; 1.14; 1.16; 1.19.

| Secondary outcomes | AT III n/N |

Control n/N |

Low risk of bias trials RR (95% CI) |

High risk of bias trials RR (95% CI) |

Overall RR (95% CI) |

| Analysis 1.11: Intracranial bleeding | 36/1226 | 26/1228 | 1.62 (0.96 to 2.73) | 0.92 (0.51 to 1.66) | 1.26 (0.83 to 1.92) |

| Analysis 1.12: Renal failure | 2/33 | 3/32 | 3.00 (0.13 to 69.52) | 0.31 (0.04 to 2.57) | 0.71 (0.08 to 6.11) |

| Analysis 1.13: Complications other than bleeding | 14/75 | 33/112 | 0.75 (0.18 to 3.07) | 0.72 (0.40 to1.30) | 0.72 (0.42 to 1.25) |

| Analysis 1.14: Bleeding events | 317/1492 | 201/1527 | 1.58 (1.35 to 1.85) | 1.57 (0.71 to 3.49) | 1.58 (1.35 to 1.84) |

| Analysis 1.16: Incidence of surgical intervention | 31/51 | 30/52 | 1.04 (0.85 to 1.27) | NA | 1.04 (0.85 to 1.27) |

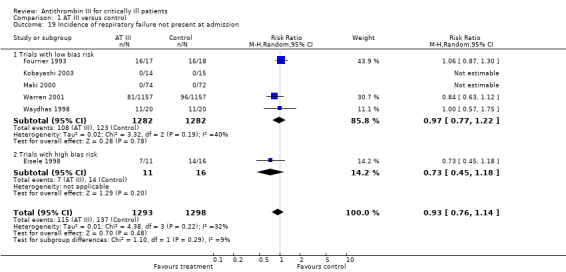

| Analysis 1.19: Respiratory failure not present at admission | 115/1293 | 137/1298 | 0.97 (0.77 to 1.22) | 0.73 (0.45 to 1.18) | 0.93 (0.76 to 1.14) |

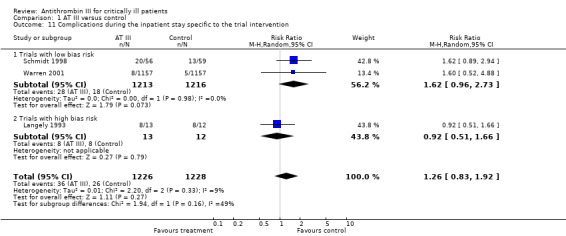

1. Complications during the inpatient stay specific to the trial intervention

Two trials with low risk of bias (Schmidt 1998; Warren 2001) and one trial with high risk of bias (Langely 1993) demonstrated a statistically significant increase in complications specific to the trial intervention: RR 1.26 (95% CI 0.83 to 1.92, I² statistic = 9%, P value = 0.33), based on data from 2454 participants in the three trials. We analysed results using a random‐effects model. We downgraded the outcome from high to very low quality because of the small number of trials (Analysis 1.11)

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 AT III versus control, Outcome 11 Complications during the inpatient stay specific to the trial intervention.

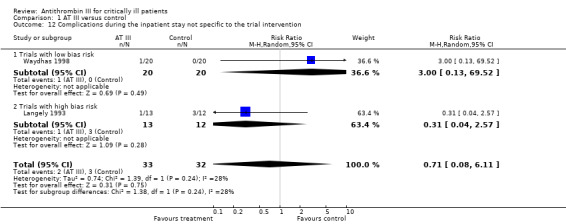

2. Complications during the inpatient stay not specific to the trial intervention

Two trials (Langely 1993; Waydhas 1998) did not reach statistical significance assessing complications not specific to the trial intervention: RR 0.71 (95% CI 0.08 to 6.11, I² statistic = 28%, P value = 0.24), based on data from 65 participants. We analysed results using a random‐effects model. We downgraded the outcome from high to very low quality because of the small number of trials (Analysis 1.12)

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 AT III versus control, Outcome 12 Complications during the inpatient stay not specific to the trial intervention.

3. Complications specific to the trial intervention other than bleeding

Three trials, one with low risk of bias (Fulia 2003) and two with high risk of bias (Eisele 1998; Mitchell 2003), examined complications specific to the trial intervention other than bleeding: RR 0.72 (95% CI 0.42 to 1.25, I² statistic = 0%, P value = 0.95), based on data from 187 participants in the three trials. We analysed results using a fixed‐effect model. We downgraded the outcome from high to very low quality because of the small number of trials (Analysis 1.13)

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1 AT III versus control, Outcome 13 Complication specific to the trial intervention other than bleeding.

4. Bleeding events

Six trials with low risk of bias (Baudo 1998; Fulia 2003; Kobayashi 2003; Maki 2000; Schmidt 1998; Warren 2001) and five with high risk of bias (Gando 2013; Grenander 2001; Langely 1993; Mitchell 2003; Neporada 2008A) demonstrated a statistically significant increase in bleeding events in the intervention group compared to the control group, with a RR of 1.58 (95% CI 1.35 to 1.84, I² statistic = 0%, P value = 0.57), based on data from 3019 participants in the 11 trials. We analysed results using a fixed‐effect model. We downgraded the outcome from high to moderate quality because of the proportion of trials with high risk of bias (Analysis 1.14)

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1 AT III versus control, Outcome 14 Bleeding events.

5. Amount of red blood cells administered

Four trials referred to the amount of red blood cells administered; one with low risk of bias (Fourrier 1993) and three with high risk of bias (Baudo 1992; Blauhut 1985; Inthorn 1997) with a mean difference (MD) of 138.49 (95% CI ‐391.35 to 668.34, I² statistic = 88%, P value = 0.0001), based on data from 137 participants. We analysed results using a random‐effects model. We downgraded the outcome from high to very low quality because of the small number of trials, three of them with high risk of bias (Analysis 1.15)

1.15. Analysis.

Comparison 1 AT III versus control, Outcome 15 Amount of red blood cells administered.

6. Incidence of surgical intervention

Three trials referred to the incidence of surgical intervention, all with low risk of bias (Fourrier 1993; Kobayashi 2003; Waydhas 1998) with a RR of 1.04 (95% CI 0.85 to 1.27, I² statistic = 0%, P value = 0.61), based on data from 103 participants. We analysed results using a fixed‐effect model. We downgraded the outcome from high to very low quality because of the small number of trials with few participants (Analysis 1.16)

1.16. Analysis.

Comparison 1 AT III versus control, Outcome 16 Incidence of surgical intervention.

7. Severity of sepsis

Only Analysis 1.17, of the three different analyses (Analysis 1.17; Analysis 1.18; Table 4) reached statistical significance, with a MD of ‐1.24 (95% CI ‐2.18 to ‐0.29, I² statistic = 48%, P value = 0.015, random‐effects model, 3 trials, 156 participants) (Baudo 1998; Eisele 1998; Inthorn 1997) when examining the effect of AT III on various illness scores. Six trials provided data (Baudo 1998; Diaz‐Cremades 1994; Eisele 1998; Haire 1998; Inthorn 1997; Schorr 2000). However, the trials that did provide data adequate for meta‐analysis were quite heterogenous in their application of various scores and their choice of time points.

1.17. Analysis.

Comparison 1 AT III versus control, Outcome 17 Severity of sepsis I.

1.18. Analysis.

Comparison 1 AT III versus control, Outcome 18 Severity of sepsis II.

3. Severity of sepsis III.

| Trial | AT III | Control | Mean Difference | ||||

| Mean | SD | Total | Mean | SD | Total | IV, Fixed, 95% CI | |

| Eisele 1998 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 15 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 13 | ‐0.20 (‐0.66 to 0.26) |

Subgroup analysis where only one trial had the relevant endpoints.

8. Incidence of respiratory failure not present at admission

Six trials examined the effect of AT III on the incidence of respiratory failure (not present at admission) (Eisele 1998; Fourrier 1993; Kobayashi 2003; Maki 2000; Warren 2001; Waydhas 1998). There was no statistically significant difference, with a RR of 0.93 (95% CI 0.76 to 1.14, I² statistic = 32%, P value = 0.22), based on data from 2591 participants in six trials. We analysed results using a random‐effects model. We downgraded the outcome from high to moderate quality because one trial contributed with the majority of patients (Warren 2001. It is considered to skew the finding; however, it is rated low risk of bias, and contributes a weighting of only 30.7%. A sensitivity analysis removing it from the plot eliminates all heterogeneity in that subgroup.

9. Duration of mechanical ventilation

Three trials examined the effect of the trial intervention on duration of mechanical ventilation (Grenander 2001; Schmidt 1998; Waydhas 1998). There was no statistically significant difference, with a MD of 2.20 (95% CI ‐1.21 to 5.60, I² statistic = 0%, P value = 0.89), based on data from 190 participants. We analysed results using a fixed‐effect model. We downgraded the outcome from high to very low quality of evidence because of the small number of trials, few participants and imprecision of results with a wide confidence interval. The mean duration of mechanical ventilation in the intervention group was 2.2 days more (1.21 fewer to 5.6 more). (Analysis 1.20).

1.20. Analysis.

Comparison 1 AT III versus control, Outcome 20 Duration of mechanical ventilation.

10. Length of stay in hospital

Four trials examined the intervention effect on the length of stay in hospital (Haire 1998; Neporada 2008A; Smith‐Erichsen 1996; Waydhas 1998) with a MD of 1.10 (95% CI ‐7.16 to 9.36, I² statistic = 74%, P value = 0.009), based on data from 202 participants. We analysed results using a random‐effects model. We downgraded the outcome from high to very low quality of evidence because of the small number of trials, few participants and imprecision of results with a wide confidence interval. The mean length of stay in hospital in the intervention group was 1.1 days more (7.16 fewer to 9.36 more). (Analysis 1.21)

1.21. Analysis.

Comparison 1 AT III versus control, Outcome 21 Length of stay in hospital.

11. Mean length of stay in the ICU

Three trials with low risk of bias (Baudo 1998; Fourrier 1993; Waydhas 1998) and four trials with high risk of bias (Albert 1992; Diaz‐Cremades 1994; Neporada 2008A; Smith‐Erichsen 1996) examined the intervention effect on length of stay in the ICU. There was insufficient evidence to support any beneficial effect of the intervention, with a MD of 0.24 (95% CI ‐1.34 to 1.83, I² statistic = 0%, P value = 0.70), based on data from 376 participants. We analysed results using a fixed‐effect model. We downgraded the outcome from high to very low quality of evidence because of the small number of trials, most of them with high risk of bias. The mean length of stay in ICU in the intervention group was 0.24 days more (1.34 fewer to 1.83 more). (Analysis 1.22).

1.22. Analysis.

Comparison 1 AT III versus control, Outcome 22 Mean length of stay in ICU.

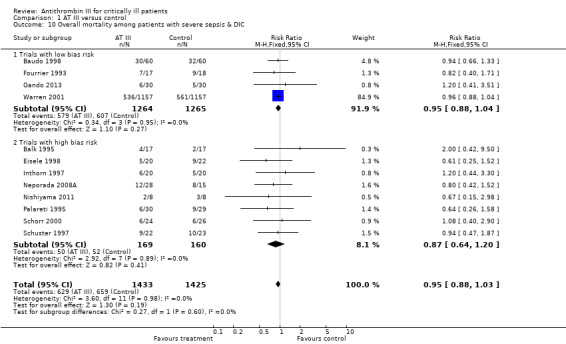

12. Overall mortality among participants with severe sepsis and DIC

Twelve trials examined the intervention effect on mortality among participants with severe sepsis and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) (Balk 1995; Baudo 1998; Eisele 1998; Fourrier 1993; Gando 2013; Inthorn 1997; Neporada 2008A; Nishiyama 2011; Palareti 1995; Schorr 2000; Schuster 1997; Warren 2001). The trials demonstrated a statistically significant decrease in mortality in favour of the trial intervention: RR 0.95 (95% CI 0.88 to 1.03, I² statistic = 0%, P value = 0.98), based on data from 2858 participants. We analysed results using a fixed‐effect model. We downgraded the outcome from high to very low quality of evidence, because of numerous trials with high risk of bias. The vast majority of trials were small and poorly described.

Subjective overall quality‐of‐life assessment

Only one trial examined the intervention's effect on quality of life (Rublee 2003: based on data from Warren 2001). There was an objective assessment of physical performance and dependency, and a subjective overall quality‐of‐life assessment analysis. Neither assessment supported intervention with AT III, with a MD of ‐2.00, (95% CI ‐4.49 to 0.49, fixed‐effect model, 897 participants) and a MD of ‐2.00, (95% CI ‐5.01 to 1.01, fixed‐effect model, 897 participants) respectively, both rated at very low quality (Table 5; Table 6).

4. Subjective overall quality of life assessment.

| Trial | At III | Control | Mean Difference | ||||

| Mean | SD | Total | Mean | SD | Total | IV, Fixed, 95% CI | |

| Warren 2001 | 47 | 23 | 460 | 49 | 23 | 437 | ‐2.00 (‐5.01 to 1.01) |

Subgroup analysis where only one trial had the relevant endpoints.

5. Objective assessment of physical performance and dependency (Karnofsky).

| Trial | AT III | Control | Mean Difference | ||||

| Mean | SD | Total | Mean | SD | Total | IV, Fixed, 95% CI | |

| Warren 2001 | 53 | 19 | 460 | 55 | 19 | 437 | ‐2.00 (‐4.49 to 0.49) |

Subgroup analysis where only one trial had the relevant endpoints.

Subgroup and sensitivity analyses

The heparin issue

A detrimental interaction between AT III and heparin was suspected before the Warren 2001 trial, and we predefined use of AT III with and without heparin in the protocol for secondary analyses. However, the participants were not stratified according to heparin administration and the protocol allowed concomitant use of heparin by indication, after randomization to AT III or placebo. Even if the baseline comparison of participants allocated to AT III and placebo, in the subgroup without heparin, showed similar characteristics, the randomization is violated in the subgroup analysis.

Pooling all trials with and without concomitant use of heparin, with the Warren 2001 trial as either a trial with concomitant use of heparin or as a trial without use of heparin, does not provide evidence of a statistically significant intervention effect of AT III (Analysis 1.7; Analysis 1.8). Even when splitting the Warren 2001 trial into two 'separate trials', with and without concomitant use of heparin, and pooling these results with the other trials, we found no statistically significant intervention effect of AT III in the subgroup of trials without adjuvant heparin administration (RR 0.95, 95% CI 0.88 to 1.03; I² statistic = 0%, fixed‐effects model, Analysis 1.9). However, splitting the Warren 2001 trial violates the randomization procedure.

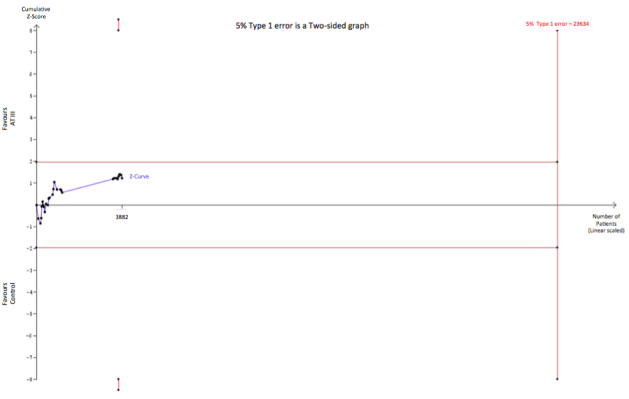

Trial sequential analysis

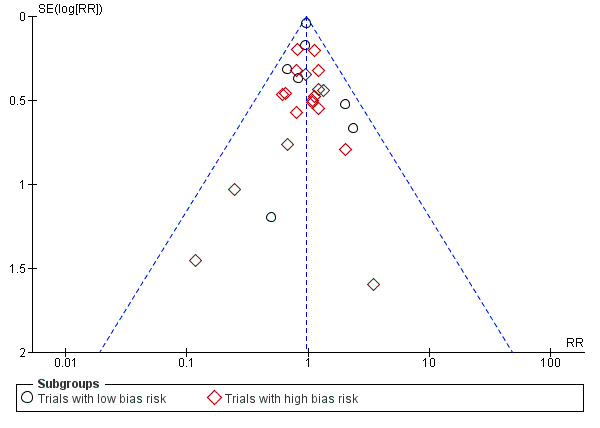

We conducted trial sequential analysis (TSA) of AT III versus control on longest follow‐up mortality (Analysis 1.1; Figure 5). The TSA‐adjusted confidence interval for the meta‐analysis of the primary outcome with continuity correction for zero events trials (0.001 event in each arm) in a fixed‐effect model results in a RR of 0.95 (95% CI 0.88 to 1.03; I² statistic = 0%, Diversity D² = 0%). The point estimate of the potential intervention effect as suggested by the low risk of bias trials in the meta‐analysis of the effect of AT III on mortality is a relative risk reduction (RRR) of 5% and the low‐bias heterogeneity‐adjusted information size (LBHIS) calculated based on this intervention effect (with 80% power and alpha 0.05, assuming a double‐sided type I risk of 5% and a type II risk of 20%) is 23,634 participants (Figure 6). With an accrued information size of 3882 participants and no boundaries crossed so far, only 16.43% of the required information size is actually available at this stage to reject or accept a 4% RRR for overall mortality.

5.

Funnel plot, overall mortality regardless of follow‐up and bias Analysis 1.1

6.

Trial sequential analysis of all trials with low risk of bias of the effect of AT III on mortality. Cumulative Z‐curve in blue does not cross the trial sequential monitoring boundary (full red line with open diamonds) constructed for a low‐bias heterogeneity‐adjusted information size of 23,634 participants corresponding to a RRR of 5% with an α = 0.05 and a power of 80% (β = 0.20). Only 16.43 % of the required information size has been reached so far.

However, solid evidence may be obtained with fewer participants if eventually the cumulative meta‐analysis Z‐curve crosses the trial sequential monitoring boundary constructed for a required information size of 23,634 randomized participants.

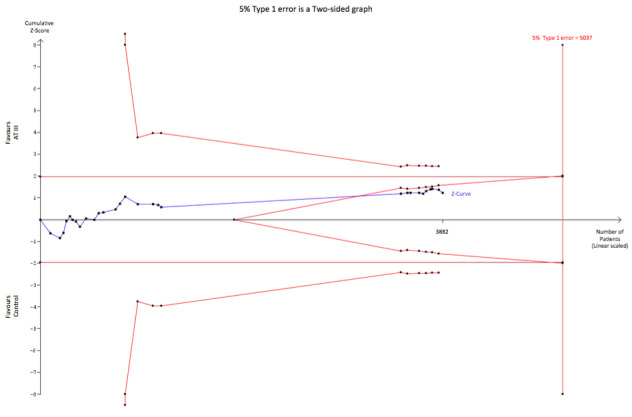

On the other hand, to demonstrate or reject an a priori anticipated intervention effect of a RRR of 10%, 5037 should be randomized. In this analysis, the cumulative Z‐curve breaks through the boundary for futility (non‐superiority) (Figure 7). As 3882 participants are included in the present meta‐analyses on mortality without the meta‐analysis becoming statistically significant and since the futility boundary is crossed, an intervention effect of 10% RRR or more on mortality is unlikely.

7.

Trial sequential analysis (TSA) of all trials of the effect of AT III on mortality. Cumulative Z‐curve in blue does not cross the boundary constructed for an information size of 5037 in the meta‐analysis (full red line with open diamonds) with a RRR of 10% (α = 0.05) and a power of 80% (β = 0.20). However, the cumulative Z‐curve breaks through the boundary for futility (non‐superiority). The analysis therefore led to rejection of an intervention effect of a RRR of 10% with a power of 80% in 30 randomized trials with a total number of accrued participants of 3882.

When carrying out the same TSA analyses as above for trials of sepsis and DIC only (Analysis 1.10) with an anticipated RRR of 10%, the required information size is 3794 participants without the meta‐analysis becoming statistically significant, and with the boundary for futility being crossed, thus indicating that a RRR of 10% is to be rejected. (Figure 8)

8.

Trial sequential analysis (TSA) of all trials of sepsis and DIC examining the effect of AT III on mortality. Cumulative Z‐curve in blue does not cross the boundary constructed for an information size of 3794 in the meta‐analysis (full red line with open diamonds) with a RRR of 10% (α = 0.05) and a power of 80% (β = 0.20). However, the cumulative Z‐curve breaks through the boundary for futility (non‐superiority). The analysis therefore led to rejection of an intervention effect of a RRR of 10% with a power of 80% in 30 randomized trials with a total number of accrued participants of 2992.

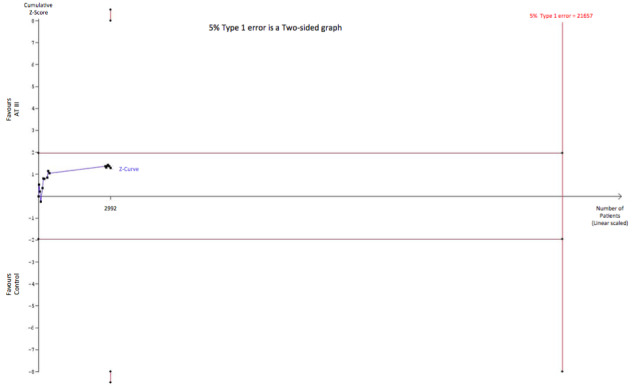

TSA analysis based on a potential RRR of 5% as indicated by the meta‐analysis for studies on sepsis and DIC (Analysis 1.10) yields a LBHIS of 21,657 participants and with an accrued information size of 2992 participants and no boundaries being crossed so far, only 13.82% of the required information size is actually available (Figure 9).

9.

Trial sequential analysis of all trials of Sepsis and DIC with low risk of bias examining the effect of AT III on mortality. Cumulative Z‐curve in blue does not cross the trial sequential monitoring boundary (full red line with open diamonds) constructed for a low bias heterogeneity adjusted information size of 21,657 participants corresponding to a RRR of 5% with an α = 0.05 and a power of 80% (β = 0.20). Only 13.82 % of the required information size has been reached so far.

Discussion

Summary of main results

In this systematic review of 30 trials with 3933 participants we found no significant beneficial effect of AT III on mortality (Analysis 1.1).

The analyses on mortality showed no heterogeneity and were robust when performing different subgroup analyses. Conversely, AT III increased the risk of bleeding (Analysis 1.14) and it appeared to improve only one of the reported severity of sepsis scores (multiple organ failure syndrome, MOFS) with limited data included in the analysis (inadequate power and precision) and remains a surrogate outcome (Analysis 1.17). None of the other secondary outcomes reached statistical significance.

Neither the meta‐analysis nor the subgroup analyses demonstrated a statistically significant effect of AT III on mortality. However, this is not evidence of the absence of a beneficial effect, but the data suggest that a potentially beneficial effect of AT III must be at best modest compared to what had been expected. Trial sequential analysis added valuable information to the level of evidence and as such we are able to reject an intervention effect of 10% RRR or more for all trials, as well as trials including participants with sepsis and DIC. Additionally, based on the existing level of evidence from trials with low risk of bias, only 16.43% of the required information size is available to reject or accept a 5% RRR for overall mortality.

Subgroup analysis of duration of intervention and length of follow‐up

Based on follow‐up less than or longer than the median of all trials, we undertook a subgroup analysis to examine the intervention effect on mortality. However, there was no statistically significant association between follow‐up and mortality (see Analysis 1.2). The median follow‐up time was 32 days.

We also examined the intervention effect based on the median duration of intervention being less than or longer than one week (Analysis 1.3). Only three trials with a total of 208 participants had a median duration of intervention longer than one week (Inthorn 1997; Mitchell 2003; Smith‐Erichsen 1996). The current evidence does not support a longer duration of intervention.

Subgroup analyses on paediatric, obstetric and trauma populations

Based on the existing data, we have to conclude that there is insufficient data to help us support or refute the use of AT III intervention among trauma, obstetric, or paediatric populations.

Subgroup analyses regarding septic populations

Very few trials met our requirements in terms of trial intervention effect on various illness scores. We accepted the various definitions provided by the authors and undertook four different meta‐analyses. The participant numbers in these analyses ranged from 28 to 156, and only one meta‐analysis reached statistical significance (Analysis 1.17). The meta‐analyses examining the overall mortality in the septic population, based on 2918 participants, also failed to demonstrate a statistically significant reduction of mortality (Analysis 1.10).

The heparin issue

We examined a potential detrimental interaction of AT III with heparin by carrying out three separate analyses pooling mortality data from trials with concomitant heparin use against those without (Analysis 1.7; Analysis 1.8; Analysis 1.9), while examining the impact of data from Warren 2001. The latter trial was either defined as a trial with or without heparin use (Analysis 1.7; Analysis 1.8) and finally we chose to split data from Warren 2001 in order to examine the hypothesis. As such, this is to be considered a post hoc analysis violating the randomization procedure (Analysis 1.9). However, none of these analyses demonstrated any statistically significant interaction effects.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The authors of this updated review are confident that our search strategy obtained all available studies. We have contacted several authors. We identified two additional trials by Neporada et al. One was included (Neporada 2008A) and one excluded Neporada 2008B.

Quality of the evidence

The randomized controlled trial (RCT) is considered the most rigorous method of determining whether a cause‐effect relationship exists between an intervention and outcome. The strength of the RCT lies in the process of randomization.

We rank the quality of findings from moderate to very low quality of evidence across the different outcomes. The main limiting factors were high risk of bias and small and poorly described trials.