Abstract

Background

The use of short‐acting insulin analogues (insulin lispro, insulin aspart, insulin glulisine) for adult, non‐pregnant people with type 2 diabetes is still controversial, as reflected in many scientific debates.

Objectives

To assess the effects of short‐acting insulin analogues compared to regular human insulin in adult, non‐pregnant people with type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Search methods

For this update we searched CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, the WHO ICTRP Search Portal, and ClinicalTrials.gov to 31 October 2018. We placed no restrictions on the language of publication.

Selection criteria

We included all randomised controlled trials with an intervention duration of at least 24 weeks that compared short‐acting insulin analogues to regular human insulin in the treatment of people with type 2 diabetes, who were not pregnant.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently extracted data and assessed the risk of bias. We assessed dichotomous outcomes by risk ratios (RR), and Peto odds ratios (POR), with 95% confidence intervals (CI). We assessed continuous outcomes by mean differences (MD) with 95% CI. We assessed trials for certainty of the evidence using the GRADE approach.

Main results

We identified 10 trials that fulfilled the inclusion criteria, randomising 2751 participants; 1388 participants were randomised to receive insulin analogues and 1363 participants to receive regular human insulin. The duration of the intervention ranged from 24 to 104 weeks, with a mean of about 41 weeks. The trial populations showed diversity in disease duration, and inclusion and exclusion criteria. None of the trials were blinded, so the risk of performance bias and detection bias, especially for subjective outcomes, such as hypoglycaemia, was high in nine of 10 trials from which we extracted data. Several trials showed inconsistencies in the reporting of methods and results.

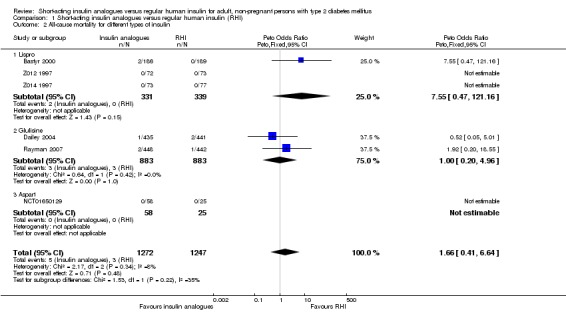

None of the included trials defined all‐cause mortality as a primary outcome. Six trials provided Information on the number of participants who died during the trial, with five deaths out of 1272 participants (0.4%) in the insulin analogue groups and three deaths out of 1247 participants (0.2%) in the regular human insulin groups (Peto OR 1.66, 95% CI 0.41 to 6.64; P = 0.48; moderate‐certainty evidence). Six trials, with 2509 participants, assessed severe hypoglycaemia differently, therefore, we could not summarise the results with a meta‐analysis. Overall, the incidence of severe hypoglycaemic events was low, and none of the trials showed a clear difference between the two intervention arms (low‐certainty evidence).

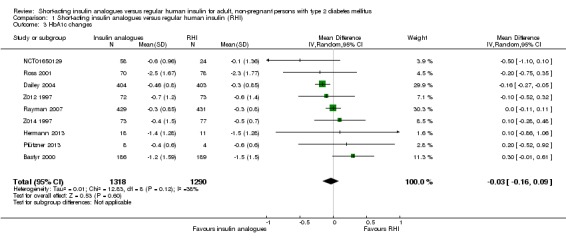

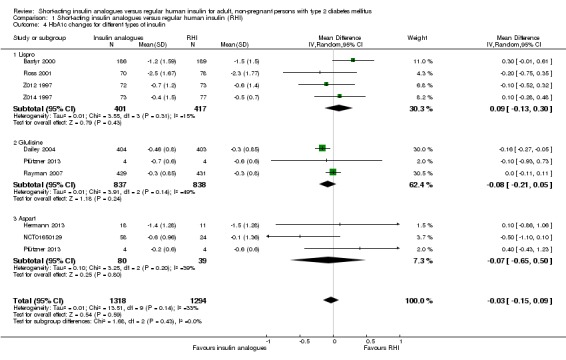

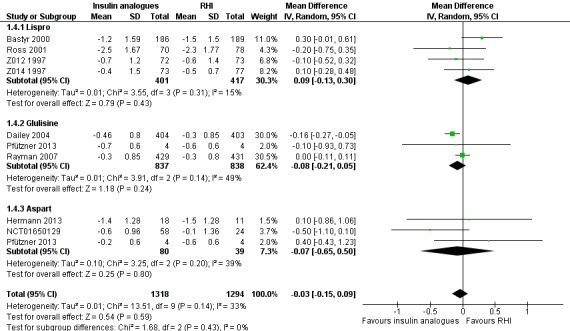

The MD in glycosylated haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) change was ‐0.03% (95% CI ‐0.16 to 0.09; P = 0.60; 9 trials, 2608 participants; low‐certainty evidence). The 95% prediction ranged between ‐0.31% and 0.25%. The MD in the overall number of non‐severe hypoglycaemic episodes per participant per month was 0.08 events (95% CI 0.00 to 0.16; P = 0.05; 7 trials, 2667 participants; very low‐certainty evidence). The 95% prediction interval ranged between ‐0.03 and 0.19 events per participant per month. The results provided for nocturnal hypoglycaemic episodes were of questionable validity. Overall, there was no clear difference between the two short‐acting insulin analogues and regular human insulin. Two trials assessed health‐related quality of life and treatment satisfaction, but we considered the results for both outcomes to be unreliable (very low‐certainty evidence).

No trial was designed to investigate possible long term effects (all‐cause mortality, microvascular or macrovascular complications of diabetes), especially in participants with diabetes‐related complications. No trial reported on socioeconomic effects.

Authors' conclusions

Our analysis found no clear benefits of short‐acting insulin analogues over regular human insulin in people with type 2 diabetes. Overall, the certainty of the evidence was poor and results on patient‐relevant outcomes, like all‐cause mortality, microvascular or macrovascular complications and severe hypoglycaemic episodes were sparse. Long‐term efficacy and safety data are needed to draw conclusions about the effects of short‐acting insulin analogues on patient‐relevant outcomes.

Short‐acting insulin analogues versus regular human insulin for type 2 diabetes mellitus

Review question

Are short‐acting insulin analogues better than regular human insulin for adult, non‐pregnant people with type 2 diabetes?

Background

Short‐acting insulin analogues act more quickly than regular human insulin. They can be injected immediately before meals and lead to lower blood sugar levels after food intake. Whether people with diabetes really profit from these newer insulins is debated.

Study characteristics

We found 10 randomised controlled trials (clinical studies where people are randomly put into one of two or more treatment groups) comparing the short‐acting insulin analogues insulin lispro, insulin aspart, or insulin glulisine to regular human insulin in 2751 participants. The people in the included trials were monitored (followed) for 24 to 104 weeks.

This evidence is up to date as of 31 October 2018.

Key results

We are uncertain whether short‐acting insulin analogues are better than regular human insulin for long‐term blood glucose control or for reducing the number of times blood sugar levels drop below normal (hypoglycaemic episodes). The studies were too short to reliably investigate death from any cause. We found no clear effect of insulin analogues on health‐related quality of life. We found no information on late diabetes complications, such as problems with the eyes, kidneys, or feet. No study reported on socioeconomic effects, such as costs of the intervention and absence from work.

Certainty of the evidence

The overall certainty of the included studies was low or very low for most outcomes, mainly because all studies were carried out in an open‐labelled fashion (study participants and study personnel knew who was getting which treatment). Several studies also showed inconsistencies in the reporting of methods, and results were imprecise.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison.

Short‐acting insulin analogues compared to regular human insulin for adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus

| Short‐acting insulin analogues compared to regular human insulin for adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus | ||||||

| Patients: adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus Setting: outpatients Intervention: short‐acting insulin analogues Comparison: regular human insulin | ||||||

| Outcomes | Risk with RHI | Risk with short‐acting insulin analogues | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (trials) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

|

All‐cause mortality (N) Follow‐up: 24‐104 weeks |

2 per 1000 | 4 per 1000 (1 to 16) | Peto OR 1.66 (0.41 to 6.64) | 2519 (6) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderatea | Low event rate |

| Macrovascular or microvascular complications | Not reported | |||||

|

Severe hypoglycaemic episodes (N) Follow‐up: 24‐52 weeks |

See comment | See comment | — | 2509 (6) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowb | Reporting of results too diverse to allow a meta‐analysis; small number of events. The effects of short‐acting insulin analogues compared with regular human insulin for this outcome are uncertain |

|

Adverse events other than severe hypoglycaemic episodes (all non‐severe hypoglycaemic episodes) (Events per participant per month) Follow‐up: 24‐52 weeks |

All non‐severe hypoglycaemic episodes ranged across RHI groups from 0.6 to 2.5 events per participant per month | The mean difference in non‐severe hypoglycaemic episodes in short‐acting insulin analogue groups was 0.08 events per participant per month higher (0.00 lower to 0.16 higher) | — | 2667 (7) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowc | The 95% prediction interval ranged between ‐0.03 events per participant per month and 0.19 events per participant per month |

|

HbA1c (%) Follow‐up: 24‐104 weeks |

The mean change in HbA1c levels across RHI groups ranged from ‐0.1% to ‐2.3% | The mean change in HbA1c levels across short‐acting insulin analogue groups was 0.03% lower (0.16% lower to 0.09% higher) | — | 2608 (9) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowd | The 95% prediction interval ranged between ‐0.31% and 0.25% |

| Health‐related quality of life (different scales used) Follow‐up: 24‐52 weeks | See comment | — | Unclear (2) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowe | Health‐related quality of life was either assessed in subpopulations of 2 trials, or insufficiently reported. The effects of short‐acting insulin analogues compared with regular human insulin for this outcome are uncertain | |

| Socioeconomic effects | Not reported | |||||

| CI: confidence interval; HbA1c: glycosylated haemoglobin A1c; N: number; OR: odds ratio; RHI: regular human insulin | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate. The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited. The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate. The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded by one level because of imprecision ‐ see Appendix 15 bDowngraded by two levels because of serious risk of bias (performance and detection bias) ‐ see Appendix 15 cDowngraded by two levels because of serious risk of bias (performance and detection bias), and by one level because of inconsistency (non‐consistent direction of effects, 95% prediction interval ranging from benefit to harm), and indirectness (surrogate outcome) ‐ see Appendix 15 dDowngraded by one level because of inconsistency (non‐consistent direction of effect, 95% prediction interval ranging from benefit to harm), and by one level because of imprecision (CI consistent with benefit and harm) ‐ see Appendix 15 eDowngraded by two levels because of serious risk of bias (performance bias, detection bias, attrition bias), and by one level because of imprecision (small number of trials) ‐ see Appendix 15

Background

Description of the condition

Type 2 diabetes mellitus is a chronic metabolic disease characterised by a combination of insulin resistance of peripheral tissues, and insufficient insulin secretion from the pancreas, which results in chronic hyperglycaemia (elevated levels of plasma glucose) with disturbances of the carbohydrate, fat, and protein metabolism. Long‐term complications of diabetes mellitus include retinopathy, nephropathy, neuropathy, and increased risk of cardiovascular disease. Type 2 diabetes is the most common form of diabetes, with the number of people affected rising rapidly worldwide (Wild 2004).

Description of the intervention

The main treatment goal for most people with type 2 diabetes is to reduce the risk of diabetic complications and hypoglycaemia. While initially, the disease can often be treated with dietary and behavioural changes alone, or in combination with non‐insulin antidiabetic drugs, eventually, many people require additional insulin therapy (ADA 1997). Different insulin regimens are possible for people with type 2 diabetes. Usually, insulin therapy for people with type 2 diabetes is initiated using basal insulin preparations to correct for fasting hyperglycaemia. However, with the progression of beta‐cell deficiency, additional insulin injections before one or several meals are often necessary to achieve sufficient glycaemic control. Alternatively, insulin therapy can be initiated or intensified with the application of twice‐daily pre‐mixed insulin, whereby the insulin mixture consists of a short‐acting and a medium‐ or long‐acting insulin component (Meneghini 2013).

Insulin preparations used for prandial application or the fast‐acting component of pre‐mixed insulin can either be regular human insulin (RHI) or short‐acting insulin analogues. In contrast to human endogenous insulin, insulin analogues have a slightly modified molecular structure, resulting in different pharmacokinetic profiles. When regular human insulin is injected subcutaneously, the plasma insulin concentration peaks about two to four hours after injection, unlike the much earlier plasma insulin peak in non‐diabetic people after meal ingestion. This low rise to peak insulin concentration makes it difficult to mimic physiologic temporal insulin profiles, and is likely to account for much of the observed hyperglycaemia following meals in people with type 2 diabetes (Zinman 1989). The delay in the absorption of subcutaneously administered regular insulin is due to the fact that in this preparation, insulin tends to associate in 'clusters' of six molecules (hexamers), and time is needed after injection for these clusters to dissociate to single molecules that can be used by the body (Mosekilde 1989). Short‐acting insulin analogues with less tendency toward self‐association are absorbed more quickly, achieving peak plasma concentrations about twice as high, and within approximately half the time as regular insulin (Howey 1994; Torlone 1994).

Currently, there are three different short‐acting insulin analogues available: insulin aspart, insulin glulisine, and insulin lispro. Compared to regular human insulin, insulin aspart has aspartic acid instead of proline at position 28 of the B‐region; in glulisine, the amino acid asparagine was replaced by lysine at position 3, and lysine with glutamic acid at position 29 of the B‐chain; and in lispro, proline at position 28 and lysine at position 29 of the B‐region were interchanged.

Adverse effects of the intervention

The key risk associated with any insulin therapy is the occurrence of hypoglycaemic episodes. While insulin analogues have been promoted as lowering the risk of hypoglycaemia, the evidence needs to be carefully evaluated, considering different patient subgroups and methodological challenges associated with the assessment of hypoglycaemia in clinical trials. For example, Singh 2009 pointed out that several trials on insulin analogues have excluded participants with a history of severe hypoglycaemia. Open‐label designs, combined with measurements of hypoglycaemia that rely solely on participants’ reports, make many results at high risk for bias. Overall, previous meta‐analyses suggested that the risk of serious hypoglycaemic episodes were similar for regular human insulin and short‐acting insulin analogues in participants with type 2 diabetes (Mannucci 2009; Singh 2009).

Another potential adverse effect of insulin therapy is weight gain. In general, improvement in glycaemic control through insulin therapy is frequently associated with weight gain, which in turn, can have negative consequences on blood pressure and lipid profiles. Especially for people with type 2 diabetes struggling with obesity, this adverse effect could have consequences for compliance. To date, there are no trials that have reported a relevant difference in weight gain between short‐acting insulin analogues and regular human insulin in people with type 2 diabetes.

Finally, the structural homology of insulin analogues to insulin‐like‐growth‐factor‐I (IGF‐I) has caused concern regarding the progression of diabetic late complications and potential mitogenic (induction of cell division) effects, especially with long‐term use of insulin analogues. IGF‐I may affect the progression of retinopathy (Grant 1993; King 1985), and certain modified insulin analogues have shown a carcinogenic effect in the mammary glands in female rats (Jørgensen 1992), or mitogenic potency in osteosarcoma cells (Kurtzhals 2000).

How the intervention might work

Due to their faster pharmacokinetics, insulin analogues could lead to lower glucose levels after meals, and potentially also improve overall glycaemic control (Heinemann 1996; Howey 1994). Since it has been proposed by some authors that lower postprandial glucose may be associated with a lower risk of cardiovascular complications in diabetes, hypothetically, treatment with short‐acting insulin analogues could also result in a reduced risk for complications (Haffner 1998).

Insulin analogues might have additional beneficial effects on patients’ quality of life by requiring less restrictive mealtime planning. For participants treated with RHI, insulin should be administered at least 30 minutes before meals. However, this recommendation is often not followed by patients because of its inconvenience (Overman 1999). In contrast, short‐acting insulin analogues can be injected directly before meals, or even after meals, without a deterioration of prandial glycaemic control (Brunner 2000; Giugliano 2008; Schernthaner 1998).

Why it is important to do this review

Based on their pharmacokinetic profile, we might expect short‐acting insulin analogues to improve the insulin therapy of people with diabetes mellitus, but at best, the evidence collected in previous reviews and meta‐analyses showed only limited benefits on glycaemic control and the frequency of hypoglycaemic episodes, compared to therapy with regular human insulin (Gough 2007; Mannucci 2009; Singh 2009; WHO 2011). Furthermore, potential adverse effects of treatment with these insulin analogues have not been ruled out sufficiently, and there is a lack of evidence regarding the effects on long‐term clinical outcomes (Singh 2009; WHO 2011).

Although clinical guidelines on type 2 diabetes do not give a clear preference of short‐acting insulin analogues over regular human insulin (NICE 2008; NVL 2013), short‐acting insulin analogues have become increasingly popular in the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus since their introduction to the market (Alexander 2008; Frick 2008).

Based on the results of cost effectiveness analyses (Cameron 2009; Holden 2011), this heavy use of insulin analogues promoted through aggressive marketing of the pharmaceutical industry has become a matter of political debate (Frick 2008; Gale 2011; Gale 2012; Holleman 2007; Sawicki 2011). This issue is of particular importance for low‐ and middle‐income countries, where people still die due to the lack of affordable insulin (Cohen 2011; Gale 2011).

Considering this background, the availability of current evidence is highly relevant. The aim of this work was to systematically review the clinical efficacy and safety of the short‐acting insulin analogues aspart, glulisine, and lispro in the treatment of people with type 2 diabetes mellitus, with a particular focus on long‐term clinical outcomes. In contrast to the previous review, this update is restricted to trials with a follow‐up duration of at least 24 weeks (Siebenhofer 2006).

Objectives

To assess the effects of short‐acting insulin analogues compared to regular human insulin (RHI) in adult, non‐pregnant persons with type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) with a treatment duration (follow‐up) of 24 weeks or more, designed to compare participants with type 2 diabetes who were treated with the currently available short‐acting insulin analogues lispro, aspart, glulisine, or with their biosimilars, compared with RHI, regardless of dose or schedule.

For mortality, macrovascular, and microvascular complications, trials with a follow‐up of several years would be needed. To assess metabolic control, trials with a shorter duration could be useful, if the blood glucose lowering effect of the investigated treatments were assessed with sufficient confidence, and compared to patient‐relevant outcomes (e.g. avoidance of hypoglycaemic events). Thus, we considered trials with a minimum duration of 24 weeks for inclusion in this review. This is concurrent with the requirement of the European Medicines Agency for confirmatory trials in the treatment of diabetes mellitus (EMA 2002).

Types of participants

Adults (18 years and older) with type 2 diabetes mellitus who were not pregnant.

Diagnostic criteria for type 2 diabetes mellitus

In order to be consistent with changes in the classification and diagnostic criteria of diabetes mellitus over the years, the diagnosis should have been established using the standard criteria valid at the time of the trial commencing (for example ADA 2003; ADA 2017; WHO 1999). Ideally, diagnostic criteria should have been described. We used the trial authors' definition of diabetes mellitus, if necessary. We had planned to subject diagnostic criteria to a sensitivity analysis.

Types of interventions

We considered all trials comparing treatment with short‐acting insulin analogues (insulin lispro, insulin aspart, insulin glulisine, or biosimilars) to treatment with RHI, if insulin was injected subcutaneously via syringe, pen, or pump.

Combination with long‐ or intermediate‐acting insulins was possible, as long as any additional treatment was given equally to both groups.

We planned to investigate the following comparisons of interventions versus control or comparator.

Intervention

Short‐acting insulin analogues (insulin lispro, insulin aspart, insulin glulisine, or biosimilars)

Comparison

Regular human insulin (RHI)

Concomitant interventions had to be the same in both the intervention and comparator groups to establish fair comparisons.

If a trial included multiple arms, we included any arm that met the review inclusion criteria.

Summary of specific exclusion criteria

We excluded trials of the following category.

Trials in participants younger than 18 years

Trials in pregnant women

Trials with a treatment duration (follow‐up) of less than 24 weeks

Trials where insulin was not administered subcutaneously

Types of outcome measures

Glycosylated haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) is used in many trials as a surrogate outcome for macrovascular and microvascular endpoints. Because the incidence of such late complications rises with higher HbA1c values in a linear way in observational studies, it was assumed that lowering HbA1c would, in turn, lead to a reduction of unfavourable outcomes, such as myocardial infarction, stroke, amputation, nephropathy, retinopathy, etc (Nordwall 2009; Stratton 2000). However, in interventional trials in people with type 2 diabetes mellitus, lowering HbA1c was not consistently associated with a corresponding lowering of the incidence of the above mentioned patient‐relevant outcomes, and in some instances, was even associated with a increase of such events (ACCORD 2008; Nissen 2007; Singh 2007). Therefore, we did not consider it a valid surrogate endpoint for reduction of late diabetic complications in persons with type 2 diabetes mellitus in this systematic review.

In this review, we reported HbA1c, because it is required to judge the effects of the different insulins on the occurrence of hypoglycaemic reactions. Intervention trials have shown that lowering blood glucose targets was associated with higher rates of hypoglycaemic events (ACCORD 2008; ADVANCE 2008; DCCT 1993; Duckworth 2009; UKPDS 1998). Thus, a reduction of such events in one of the comparison groups in interventional trials could be caused by a lower intensity of blood glucose reduction, and not necessarily by the effect of a specific treatment. Because of this, the rate of hypoglycaemic events has to be judged in reference to the respective blood glucose lowering effects, measured by HbA1c.

Primary outcomes

All‐cause mortality

Macrovascular and microvascular complications

Severe hypoglycaemic episodes

Secondary outcomes

Glycaemic control (HbA1c)

Adverse events other than severe hypoglycaemic episodes

Health‐related quality of life

Socioeconomic effects

Method of outcome measurement

All‐cause mortality: death from any cause

Macrovascular complications: nonfatal and fatal myocardial infarction and stroke

Microvascular complications: manifestation and progression of retinopathy, nephropathy, neuropathy, and end‐stage renal disease

Severe hypoglycaemic episodes: number of participants with at least one severe hypoglycaemic episode

Glycaemic control: measured by HbA1c in percent or mmol/mol

Adverse events other than severe hypoglycaemic episodes: number of non‐severe overall hypoglycaemic episodes, number of participants who experienced at least one episode of ketoacidosis, weight gain, or other adverse events

Health‐related quality of life: evaluated with a validated instrument, such as the 36‐item Short Form Health Survey (SF‐36) or the EuroQol Instument (EQ‐5D), and measured at the latest measurement time point during follow‐up

Socioeconomic effects: costs of the intervention, absence from work, medication consumption, etc

Timing of outcome measurement

We included outcomes that were measured after a time interval of shorter than 12 months (short‐term), or longer than 12 months (long‐term).

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

This review is an update of the former review 'Short‐acting insulin analogues versus regular human insulin in patients with diabetes mellitus', which was withdrawn and split into two Cochrane Reviews on short‐acting insulin analogues versus regular human insulin for type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus.

The review teams carried out the electronic search in two steps. The first search was conducted from inception until April 2015 in the following databases:

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL, 2015, issue 3), in the Cochrane Library (March 2015).

MEDLINE Ovid, MEDLINE In‐process & Other Non‐indexed Citations Ovid, MEDLINE Daily Ovid, and OLDMEDLINE Ovid (1946 to 14 April 2015);

Embase Ovid (1988 to 2015, Week 15);

A second search was conducted from 1 January 2015 to the specified date in the following sources:

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) via Cochrane Register of Studies Online (CRSO; searched on 31 October 2018);

MEDLINE Ovid (Epub Ahead of Print, In‐Process & Other Non‐indexed Citations, MEDLINE Daily and OLDMEDLINE (1 January 2015 to 31 October 2018);

Embase Ovid (1 January 2015 to 5 October 2017).

We did not update the Embase search after 2017, as RCTs indexed in Embase are now prospectively added to CENTRAL via a highly sensitive screening process (CENTRAL creation details).

We searched the following clinical trial registers from inception to the specified date:

ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov; searched on 31 October 2018);

WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP; apps.who.int/trialsearch/; searched on 31 October 2018).

For detailed search strategies, see Appendix 1. We placed no restrictions on the language of publication when searching the electronic databases or reviewing reference lists of identified trials.

Searching other resources

In addition to the electronic search, we reviewed references from original articles and reviews.

For the original review, we screened abstracts of major diabetology meetings (European Association for the Study of Diabetes, American Diabetes Association) from 1992, and articles of diabetes journals (Diabetologia, Diabetic Medicine, Diabetes Care, Diabetes) until December 2003.

We directed inquiries to the three main pharmaceutical companies producing short‐acting insulin analogues (Aventis, Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk). In addition, we searched the company’s trial registers (Lilly; Novo Nordisk; Sanofi).

We contacted experts and approval agencies (the European Agency for the Evaluation of Medicinal Products (EMA), the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the Medicines Control Agency (MCA), the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA); Hart 2012;Schroll 2015).

For economic analyses, we contacted the Pharmaceutical Evaluation Section of the Pharmaceutical Benefits Branch of the Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care of Australia.

We also reviewed the bibliography of standard textbooks (Diabetes Annual, 12 (Marshall 1999); Praxis der Insulintherapie (Berger 2001), Evidence‐based Diabetes Care (Gerstein 2001)).

We considered additional information, based on original trial reports, which was published in a report by the German Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWIG 2005). Therefore, this report was cited as an additional source. If we encountered inconsistency between journal publications and the IQWIG 2005, we used data from the IQWiG report, since these data were based on original trial reports, and therefore deemed more reliable.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (BF or MS, KH or TS) independently scanned the abstract, title, or both, of every record retrieved by the literature searches, to determine which trials we should assess further. We resolved any disagreements through consensus, or by recourse to a third review author (AS). If resolving disagreement was not possible, we categorised the trial as 'awaiting classification', and contacted the trial authors for clarification. We presented an adapted PRISMA flow‐diagram to shown the process of trial selection (Liberati 2009). We listed all articles excluded after full‐text assessment in the 'Characteristics of excluded studies' table, and provided the reasons for exclusion.

Data extraction and management

For trials that fulfilled the inclusion criteria, two review authors (BF and MS) independently extracted relevant population and intervention characteristics. We reported data on efficacy outcomes and adverse events using standardised data extraction sheets from the Cochrane Metabolic and Endocrine Disorders (CMED) Group. We resolved any disagreements by discussion, or if required, we consulted a third review author (AS). For details, see Characteristics of included studies; Table 3; Appendix 2; Appendix 3; Appendix 4; Appendix 5; Appendix 6; Appendix 7; Appendix 8; Appendix 9; Appendix 10; Appendix 11; Appendix 12; Appendix 13; Appendix 14; Appendix 15.

Table 1.

Overview of trial populations

|

Trial ID (trial design) |

Intervention(s) and comparator(s) | Sample size | Screened/eligible (N) | Randomised (N) | Safety (N) | ITT (N) | Finished trial (N) | Randomised finished trial (%) | Treatment duration (follow‐up) |

|

Altuntas 2003 (parallel RCT) |

I: lispro | — | ‐/40 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 100 | 6 months |

| C: RHI | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 100 | ||||

| total: | 40 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 100 | ||||

|

Bastyr 2000 (parallel RCT) |

I: lispro | — | — | 186 | — | — | 156a | 83.9 | 12 months |

| C: RHI | 189 | — | — | 161a | 85.2 | ||||

| total: | 375 | — | — | 317 | 84.5 | ||||

|

Dailey 2004 (parallel non‐inferiority RCT) |

I: glulisine | — | ‐/1186 | — | 435 | 435 | 407 | — | 26 weeks |

| C: RHI | — | 441 | 441 | 405 | — | ||||

| total: | 878 | 876 | 876 | 812 | 92.5 | ||||

|

Hermann 2013 (parallel RCT) |

I: aspart | — | — | 18 | — | — | 18b | 100 | 24 months |

| C: RHI | 11 | — | — | 11b | 100 | ||||

| total: | 29 | — | — | 29 | 100 | ||||

|

NCT01650129 (parallel RCT) |

I: biphasic insulin aspart | — | ‐/88 | 58 | 58 | 58 | 54 | 93 | 24 weeks |

| C: biphasic human insulin | 26 | 25 | 25 | 24 | 96 | ||||

| total: | 84 | 83 | 83 | 78 | 95 | ||||

|

Pfützner 2013 (parallel RCT) |

I1: lispro | — | ‐/12 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4b | 100 | 6 months |

| I2: glulisine | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4b | 100 | ||||

| C: RHI | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4b | 100 | ||||

| total: | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 100 | ||||

|

Rayman 2007 (parallel non‐inferiority RCT) |

I: glulisine | — | ‐/1088 | 448 | 448 | 448 | 420 | 94 | 26 weeks |

| C: RHI | 444 | 442 | 442 | 428 | 96 | ||||

| total: | 892 | 890 | 890 | 848 | 95 | ||||

|

Ross 2001 (parallel non‐inferiority RCT) |

I: lispro | — | — | 70 | — | — | — | — | 5.5 monthsc |

| C: RHI | 78 | — | — | — | — | ||||

| total: | 148 | — | — | 143 | 97 | ||||

|

Z012 1997 (parallel non‐inferiority RCT) |

I: lispro | — | — | 72 | — | — | 70 | 97 | 12 months |

| C: RHI | 73 | — | — | 71 | 97 | ||||

| total: | 145 | — | — | 141 | 97 | ||||

|

Z014 1997 (parallel non‐inferiority RCT) |

I: lispro | — | — | 73 | — | — | 68 | 93 | 12 months |

| C: RHI | 77 | — | — | 71 | 92 | ||||

| total: | 150 | — | — | 139 | 93 | ||||

| Totals | All interventions | 1388 | |||||||

| All comparators | 1363 | ||||||||

| All interventions plus comparators | 2751 | ||||||||

aThese numbers are based on what was reported in the original study report. According to the publication, only 25 participants dropped out from the lispro study arm and 19 from the RHI bNot explicitly reported, but assumed based on the number of participants presented in the figures and results section cAccording to IQWIG 2005, no information provided on the duration in weeks; 5.5 months corresponds to a minimum of 23.6 weeks and a maximum of 24.1 weeks

—: denotes not reported C: comparator; I: intervention; ITT: intention‐to‐treat; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RHI: regular human insulin

We provided information about potentially‐relevant ongoing trials, including trial identifier, in the 'Characteristics of ongoing studies' table, and in the Appendix 7 'Matrix of study endpoints'. We tried to find the protocol of each included trial, either in databases of ongoing trials, in publications of study designs, or both, and specified data in Appendix 7.

We sent an email request to authors of included trials to enquire whether they were willing to answer questions regarding their trials. Appendix 13 shows the results of this survey. If they agreed, we sought relevant missing information on the trial from the primary trial author(s), if required.

Dealing with duplicate publications and companion papers

We maximised our yield of information by collating all available data from duplicate publications, companion documents, or multiple reports of a primary trial, as available. In case of doubt, we gave priority to the publication reporting the longest follow‐up associated with our primary or secondary outcomes.

We listed any duplicate publications, companion documents, multiple reports of a primary trial, and trial documents of included trials (such as trial registry information) as secondary references under the study identifier (ID) of the included trial. We also listed duplicate publications, companion documents, multiple reports of a trial, and trial documents of excluded trials (such as trial registry information) as secondary references under the study ID of the excluded trial.

Data from clinical trials registers

If data from included trials were available as study results in clinical trials registers, such as ClinicalTrials.gov or similar sources, we made full use of this information and extracted the data. If there was also a full publication of the trial, we collated and critically appraised all available data. If an included trial was marked as a completed study in a clinical trials register, but no additional information (study results, publication or both) was available, we added this trial to the 'Characteristics of studies awaiting classification' table.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (BF, TS, or KH) independently assessed the risk of bias of each included trial. We resolved any disagreements by consensus, or by consulting a third review author (KH). In the cases of disagreement, we consulted the remainder of the review author team, and made a judgement based on consensus. If adequate information was unavailable from the trials, trial protocols, or other sources, we contacted the trial authors to request more details or missing data on 'Risk of bias' items.

We used the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' assessment tool, and assigned assessments of low, high, or unclear risk of bias; for details see Appendix 2; Appendix 3. We evaluated individual bias items as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, according to the criteria and associated categorisations contained therein((Higgins 2011; Higgins 2017).

Summary assessment of risk of bias

We presented a 'Risk of bias' graph and a 'Risk of bias' summary figure.

We distinguished between self‐reported, investigator‐assessed, and adjudicated outcome measures.

We considered the following outcomes to be self‐reported.

Macrovascular or microvascular complications

Severe hypoglycaemic episodes

Adverse events other than severe hypoglycaemic episodes

Health‐related quality of life

We considered the following outcomes to be investigator‐assessed.

All‐cause mortality

Macrovascular or microvascular complications

Severe hypoglycaemic episodes

Glycaemic control (HbA1c)

Adverse events other than severe hypoglycaemic episodes

Socioeconomic effects

Risk of bias for a trial across outcomes: some risk of bias domains, such as selection bias (sequence generation and allocation sequence concealment), affect the risk of bias across all outcome measures in a trial. In cases of high risk of selection bias, we marked all endpoints investigated in the associated trial as being at high risk. Otherwise, we did not performed a summary assessment of the risk of bias across all outcomes for a trial.

Risk of bias for an outcome within a trial and across domains: we assessed the risk of bias for an outcome measure by including all entries relevant to that outcome (i.e. both trial‐level entries and outcome‐specific entries). We considered low risk of bias to denote a low risk of bias for all key domains, unclear risk to denote an unclear risk of bias for one or more key domains, and high risk to denote a high risk of bias for one or more key domains.

Risk of bias for an outcome across trials and across domains: these are the main summary assessments that we incorporated into our judgments about the quality of evidence in the 'Summary of findings' tables. We defined outcomes as at low risk of bias when most information came from trials at low risk of bias, unclear risk when most information came from trials at low or unclear risk of bias, and high risk when a sufficient proportion of information came from trials at high risk of bias.

Measures of treatment effect

When at least two included trials were available for a comparison and a given outcome, we tried to express dichotomous data as a risk ratio (RR) or Peto odds ratio (POR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). For continuous outcomes measured on the same scale (e.g. weight loss in kg), we estimated the intervention effect using the mean difference (MD) with 95% CIs. For continuous outcomes that measured the same underlying concept (e.g. health‐related quality of life) but used different measurement scales, we calculated the standardised mean difference (SMD). We had planned to express time‐to‐event data as a hazard ratio (HR) with 95% CIs.

Unit of analysis issues

We took into account the level at which randomisation occurred, such as cross‐over trials, cluster‐randomised trials, and multiple observations for the same outcome.

If more than one comparison from the same trial was eligible for inclusion in the same meta‐analysis, we either combined groups to create a single pair‐wise comparison, or appropriately reduced the sample size so that the same participants did not contribute multiple data (splitting the 'shared' group into two or more groups). While the latter approach offers some solution to adjusting the precision of the comparison, it does not account for correlation arising from the same set of participants being in multiple comparisons.

We wanted to re‐analyse cluster‐RCTs that did not appropriately adjust for potential clustering of participants within clusters in their analyses. We planned to inflate the variance of the intervention effects by a design effect. Calculation of a design effect involves estimation of an intra‐cluster correlation (ICC). We would have obtained estimates of ICCs through contact with the trial authors, imputed them using estimates from other included trials that reported ICCs, or using external estimates from empirical research (e.g. Bell 2013). We had planned to examine the impact of clustering using sensitivity analyses.

Dealing with missing data

If possible, we obtained relevant missing data from the authors of the included trials. We carefully evaluated important numerical data, such as screened, randomised, assigned participants, as well as intention‐to‐treat (ITT), as‐treated, and per‐protocol populations. We investigated attrition rates (e.g. dropouts, losses to follow‐up, withdrawals), and we critically appraised issues of missing data and imputation methods (e.g. last observation carried forward).

Where included trials did not report means and standard deviations (SDs) for outcomes and we did not receive the necessary information from trial authors, we imputed these values by estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of the sample (Hozo 2005).

We planned to investigate the impact of imputation on meta‐analyses by performing sensitivity analyses and we reported per outcome, which trials were included with imputed SDs.

Assessment of heterogeneity

In the event of substantial clinical or methodological heterogeneity, we did not report trial results as the pooled effect estimate in a meta‐analysis.

We identified heterogeneity (inconsistency) by visual inspection of the forest plots, and by using a standard Chi² test with a significance level of α = 0.1. In view of the low power of this test, we also considered the I² statistic, which quantifies inconsistency across trials to assess the impact of heterogeneity on the meta‐analysis (Higgins 2002; Higgins 2003).

Had we found heterogeneity, we would have attempted to determine potential reasons for it by examining individual study and subgroup characteristics.

Assessment of reporting biases

If we included 10 or more trials that investigated a particular outcome, we had planned to use funnel plots to assess small‐trial effects. Several explanations may account for funnel plot asymmetry, including true heterogeneity of effect with respect to trial size, poor methodological design (and hence bias of small trials), and publication bias. Therefore, we interpreted the results carefully (Sterne 2011).

Data synthesis

We undertook a meta‐analysis only if we judged participants, interventions, comparisons, and outcomes to be sufficiently similar to ensure an answer that was clinically meaningful. Unless good evidence showed homogeneous effects across trials of different methodological quality, we primarily summarised data at low risk of bias using a random‐effects model (Wood 2008). We interpreted random‐effects meta‐analyses with due consideration to the whole distribution of effects and presented a prediction interval (Borenstein 2017a; Borenstein 2017b; Higgins 2009). A prediction interval needs at least three trials to be calculated and specifies a predicted range for the true treatment effect in an individual study (Riley 2011). For rare events, such as event rates below 1%, we used the Peto's odds ratio (POR) method, provided that there was no substantial imbalance between intervention and comparator group sizes, and intervention effects were not exceptionally large. We performed statistical analyses according to the statistical guidelines presented in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Deeks 2017).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We expected the following characteristics to introduce clinical heterogeneity, and we had planned to carry out the following subgroup analyses, including investigation of interactions (Altman 2003).

Sex

Age

Different short‐acting insulin analogues

Additional anti‐hyperglycaemic treatment

Different methods of insulin application

Duration of disease

Duration of follow‐up

Hypoglycaemia unawareness

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to perform sensitivity analyses in order to explore the influence of the following factors (when applicable) on effect sizes, by restricting analysis to the following.

Taking into account risk of bias, as specified in the Assessment of risk of bias in included studies section.

Very long (more than 12 months) or large trials to establish how much they dominated the results.

Using the following filters: language of publication, imputation, clustered data and source of funding (industry versus other).

We also planned to test the robustness of the results by repeating the analysis using different statistical models (fixed‐effect model and random‐effects model).

Certainty of evidence

We presented the overall certainty of evidence for each outcome specified under Types of outcome measures, We assessed the certainty of our findings according to the GRADE approach, which takes into account issues related to internal validity (risk of bias, inconsistency, imprecision, publication bias) and external validity (directness of results). Two review authors (BF, KH, TS) independently rated the quality of evidence for each outcome. Differences in assessment were solved by discussion, or in consultation with a third review author.

We used the 'Checklist to aid consistency and reproducibility of GRADE assessments', to help us standardise our assessments (Appendix 15; Meader 2014). If we did not complete a meta‐analysis for an outcome, we presented the results in a narrative format in the 'Summary of findings' table. We justified all decisions to downgrade the quality of trials using footnotes, and we made comments to aid the reader's understanding of the Cochrane Review where necessary.

Summary of findings table

We presented a summary of the evidence in Table 1. It provides key information about the best estimate of the magnitude of the effect, in relative terms and as absolute differences, for the comparison of alternative management strategies (short‐acting insulin analogues versus regular human insulin), numbers of participants and trials addressing each important outcome, and a rating of overall confidence in effect estimates for each outcome. We created the 'Summary of findings' table based on the methods described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, using the Review Manager 5 table editor rather than GRADEpro GDT software (GRADEpro GDT 2015; RevMan 2014; Schünemann 2011). We reported the following outcomes, listed according to priority.

All‐cause mortality

Macrovacular or microvascular complications

Severe hypoglycaemic episodes

Adverse events other than severe hypoglycaemic episodes

Glycaemic control (HbA1c)

Health‐related quality of life

Socioeconomic effects

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

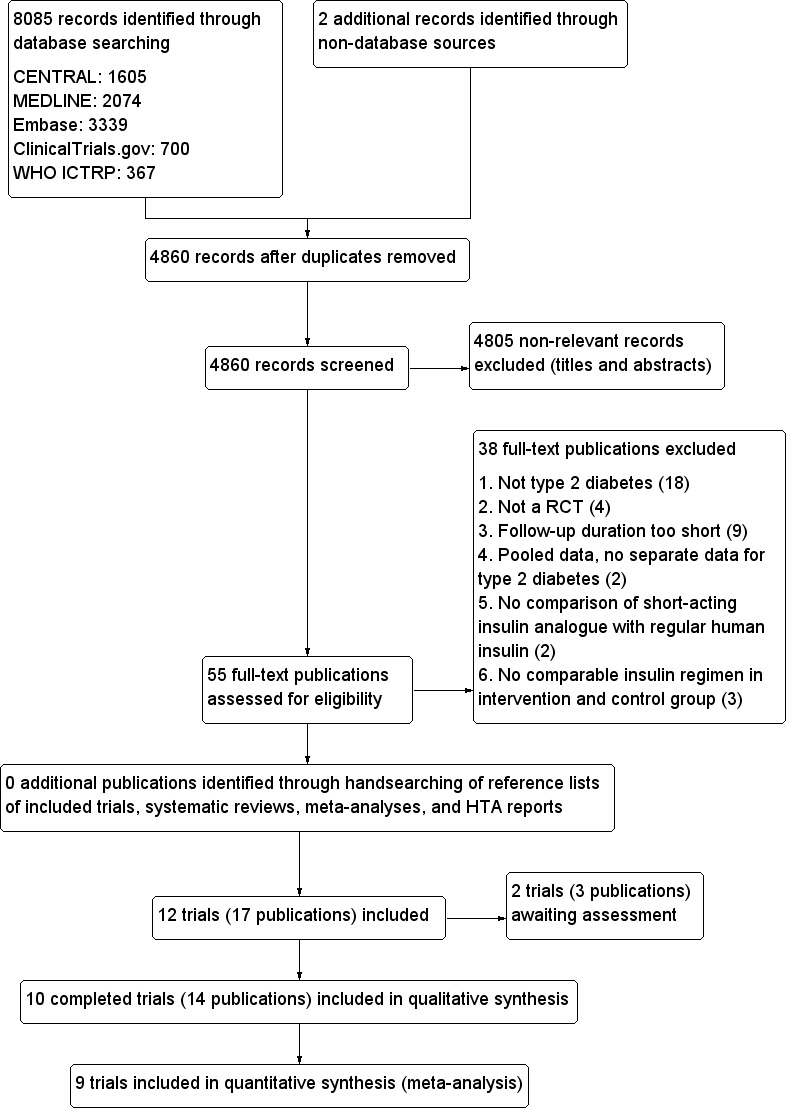

The electronic search using the search strategies described yielded 8085 references. We identified two additional records, including the IQWiG report through non‐database sources (IQWIG 2005). After we removed duplicates, 4860 records remained.

After investigating these 4860 abstracts, we excluded 4805 according to our inclusion and exclusion criteria, leaving 54 for further examination. After screening the full text of these selected records, 12 trials (17 publications) met the inclusion criteria. We classified two of these trials as awaiting classification. We identified no additional trials by handsearching the reference lists of included trials, systematic reviews, meta‐analyses, and HTA reports. In this review update we included 10 completed trials (14 publications). Three of these trials were included in our original review (Ross 2001; Z012 1997; Z014 1997). For further details see Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram

Studies awaiting classification

We classified two records as awaiting classification (see Characteristics of studies awaiting classification). One trial was listed in ClinicalTrials.gov with unknown status and estimated completion date of October 2010 (NCT01500850). So far, no trial results have been reported online, and we found no publications. We contacted the trial investigator, but received no reply. For the other trial, we were unable to determine if treatment regimens were similar in both comparison groups (Farshchi 2016). We contacted the trial investigator, but received no reply.

Ongoing trials

We found no potentially relevant ongoing RCTs that investigated short‐acting insulin analogues insulin aspart, insulin glulisine, insulin lispro, and their biosimilars compared to regular human insulin in adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Included studies

We found 10 RCTs (described in 14 reports) to be potentially appropriate for inclusion in the meta‐analysis. A detailed description of the characteristics of included studies is presented in the 'Characteristics of included studies' table. The following is a succinct overview:

Source of data

The results of the 10 trials were partially published in scientific journals between 1997 and 2013. One of these trials was only published as a conference poster (Pfützner 2013). For one of the trials, we obtained additional information from entries in clinical trials registers, and for four of the trials, we relied on additional information, based on the original study reports, which were published in a report by IQWIG (Bastyr 2000; Dailey 2004; IQWIG 2005; Z012 1997; Z014 1997). Anderson 1997 contained the combined data of two trials (Z012 1997; Z014 1997). From the publication, it was not clear that data of different two trials were combined. However, the original trial reports were available in IQWIG 2005, so we treated these trials separately in this review, using the same study names (Z012 1997; Z014 1997) as in IQWIG 2005. For one trial, information and results were only available from the entry in ClinicalTrials.gov, and from the pharmaceutical manufacturers' study reports (NCT01650129). We contacted all authors to request missing data or clarify issues about the methodology of the trial (see Appendix 13).

Comparisons

Five trials compared the insulin analogue lispro with regular human insulin (Altuntas 2003; Bastyr 2000; Ross 2001; Z012 1997; Z014 1997), two trials used the insulin analogue aspart (Hermann 2013; NCT01650129), two trials used glulisine (Dailey 2004; Rayman 2007), and one trial had three treatment arms comparing glulisine, aspart and RHI (Pfützner 2013). For details see Appendix 4.

Overview of trial populations

Overall, 2751 participants with type 2 diabetes participated in the 10 included trials; 1388 participants were randomised to the treatment arm and received a short‐acting insulin analogue, 1363 participants were randomised to the control group and received regular human insulin. On average, 95% of the randomised participants participated in the trials until the end. One trial did not report the dropout rate for the treatment arms separately, but the overall attrition rate was 3% (Ross 2001). For the remaining trials, 93% (1221) of participants finished the trial in the intervention, and 93% (1195) of the participants in the comparator groups.

The sample size ranged from 12 (Pfützner 2013) to 892 participants (Rayman 2007).

Trial design and setting

All included trials were RCTs with a parallel design; half of them were non‐inferiority trials (see Table 3). They were all open‐label trials, with no blinding of participants or investigators. The majority of the trials (70%) were carried out in multiple centres. For three trials, the setting was not reported. Two of them were likely carried out in a single centre (Altuntas 2003; Pfützner 2013), while the other was likely a multi‐centre trial (Ross 2001). Five trials had study centres in multiple countries, including countries from Europe, North and South America, Australia, and Africa (Bastyr 2000; Dailey 2004; Rayman 2007; Z012 1997; Z014 1997). The other trials were carried out in Japan (NCT01650129), Turkey (Altuntas 2003), Canada (Ross 2001), and Germany (Hermann 2013). For one trial, the country was not reported, but was likely also carried out in Germany (Pfützner 2013). Two trials provided no information on the funding source (Altuntas 2003; Ross 2001). All other trials were at least partially commercially funded. The duration of the trials ranged from 22 to 104 weeks, with a mean of about 41 weeks. Four of the trials reported a run‐in period that lasted from two to four weeks in order to achieve stable metabolic conditions (Dailey 2004; Rayman 2007; Z012 1997; Z014 1997). None of the trials were terminated before the planned end of follow‐up.

Participants

The mean age of participants was 57 years, ranging between 55 and 64 years across trials (see Appendix 4; Appendix 5). One trial did not provide information on the gender of the participants (Altuntas 2003). For the remaining trials, 45% of the participants were female. The average body mass index was 31 kg/m², with the trial means ranging from 23 kg/m² to 35 kg/m². Three trials did not report on the duration of diabetes in the participants (Hermann 2013; NCT01650129; Pfützner 2013).The mean duration of diabetes across the remaining seven trials ranged from 8 to 15 years, with an average duration across all participants of 13 years. The participants' average HbA1c was 8.1% at baseline, and varied between 7.1% and 10.6% across trials. Data on disease severity and comorbidities were generally scarce. Only Ross 2001 reported the prevalence of neuropathy, retinopathy, hypertension, and peripheral vascular disease in the overall trial sample. Three trials only included insulin naive participants (Altuntas 2003; Hermann 2013; Ross 2001). Six trials only included participants who were already insulin treated (Bastyr 2000; Dailey 2004; NCT01650129; Rayman 2007; Z012 1997; Z014 1997). Pfützner 2013 provided no information on pre‐trial blood glucose lowering medication. While OAD co‐medication was allowed in Rayman 2007 and Dailey 2004, such participants were excluded in Z012 1997 and Z014 1997. For Bastyr 2000 and NCT01650129, it remains unclear if participants had to be on insulin only. Two trials provided Information on ethnicity (Bastyr 2000; Dailey 2004). In Dailey 2004, 85% of the participants were White, 11% Black, 2% Asian, 7% Hispanic, and 1% multi‐ethnic. In Bastyr 2000, 76% of the participants were White.

Criteria for entry into the individual trials are outlined in the 'Characteristics of included studies' table. Insulin pump therapy and advanced diabetic complications were major exclusion criteria.

Diagnosis

Participants were diagnosed with type 2 diabetes mellitus in all of the trials. Most trials confirmed the diagnosis of type 2 diabetes against standard diagnostic criteria; three trials used WHO 1980 criteria ((Bennett 1991) Bastyr 2000; Z012 1997; Z014 1997), one used the ADA 1997 criteria (Altuntas 2003), and one trial used the criteria of the Japanese Diabetes Association (NCT01650129). Rayman 2007 included participants who had a type 2 diabetes diagnosis documented in their medical record. The other trials provided no information regarding their diagnostic criteria (Dailey 2004; Hermann 2013; Pfützner 2013; Ross 2001).

Interventions

All trials tried to apply a comparable insulin regimen throughout the investigation period, but usually insulin therapy was left somewhat flexible, with the aim to reach optimum glycaemic control. Ninety percent of the trials defined postprandial blood glucose targets (Altuntas 2003; Bastyr 2000; Dailey 2004; Hermann 2013; Pfützner 2013; Rayman 2007; Ross 2001; Z012 1997; Z014 1997). Trials set targets of less than 135 mg/dL, or less than 180 mg/dL. Sixty percent of the trials also specified preprandial glucose targets: three trials aimed for fasting blood glucose levels of less than 140 mg/dL (Bastyr 2000; Z012 1997; Z014 1997), Hermann 2013 aimed for less than 100 mg/dL, and Dailey 2004 and Rayman 2007 sought a preprandial target range between 90 mg/dL and 120 mg/dL.

In NCT01650129, participants took either biphasic insulin aspart 50 or biphasic human insulin 50/50 twice a day (before breakfast and dinner). In Ross 2001 and Dailey 2004, the insulin analogue plus NPH insulin, or regular human insulin plus NPH insulin was taken before breakfast and dinner. Dailey 2004 allowed additional doses of analogue or human regular insulin before meals, if necessary. In all other trials, short‐acting insulin was taken before each meal. Participants taking regular human insulin were instructed to take the insulin 30 to 40 minutes before the meal, whereas insulin analogues could be taken directly before eating. Most participants took an additional slower‐acting insulin once or twice a day. In most trials, NPH insulin was used as the basal insulin. One trial used ultralente (Z012 1997), another allowed either NPH or ultralente (Bastyr 2000), one used detemir (Hermann 2013), and one used insulin glargine (Pfützner 2013).

Three trials did not allow additional oral antidiabetic drugs (OADs (Bastyr 2000; Z012 1997; Z014 1997)). Hermann 2013 only included participants who had been using OADs for at least the last six months, but switched to short‐acting insulin as part of the trial. Two trials permitted a stable dose of OADs (Dailey 2004; Rayman 2007). The other four trials provided no information on the use of OADs (Altuntas 2003; NCT01650129; Pfützner 2013; Ross 2001).

Outcomes

Four trials clearly defined a primary study endpoint (Dailey 2004; NCT01650129; Pfützner 2013; Rayman 2007). Two trials used the change in HbA1c throughout the trial duration (Dailey 2004; Rayman 2007), one used the change in nitrotyrosine (Pfützner 2013). NCT01650129 defined two primary endpoints: the number of adverse events during the trial, and the change in HbA1c throughout the trial. Information on primary endpoints was inconsistent in three trials (Bastyr 2000; Z012 1997; Z014 1997), The original study reports referred to postprandial blood glucose levels as the primary efficacy variable, while the study protocol referred to postprandial glucose excursions and hypoglycaemia episodes in relation to glycaemic control, and metabolic control as the primary efficacy variables. The power analysis was based on the preprandial blood glucose, HbA1c, and hypoglycaemia. The remaining trials did not specify a primary study endpoint. NCT01650129 and Pfützner 2013 explicitly defined secondary outcomes.

For a summary of all outcomes assessed in each trial, see Appendix 7. For definitions of outcome measures see Appendix 9 and Appendix 10. For adverse events see Appendix 11 and Appendix 12.

Excluded studies

Overall, we excluded 38 trials upon further scrutiny of the full‐text reports. We have given the reasons for excluding trials in the 'Characteristics of excluded studies' table. The main reasons for exclusion were that participants did not have type 2 diabetes and the follow‐up duration too short.

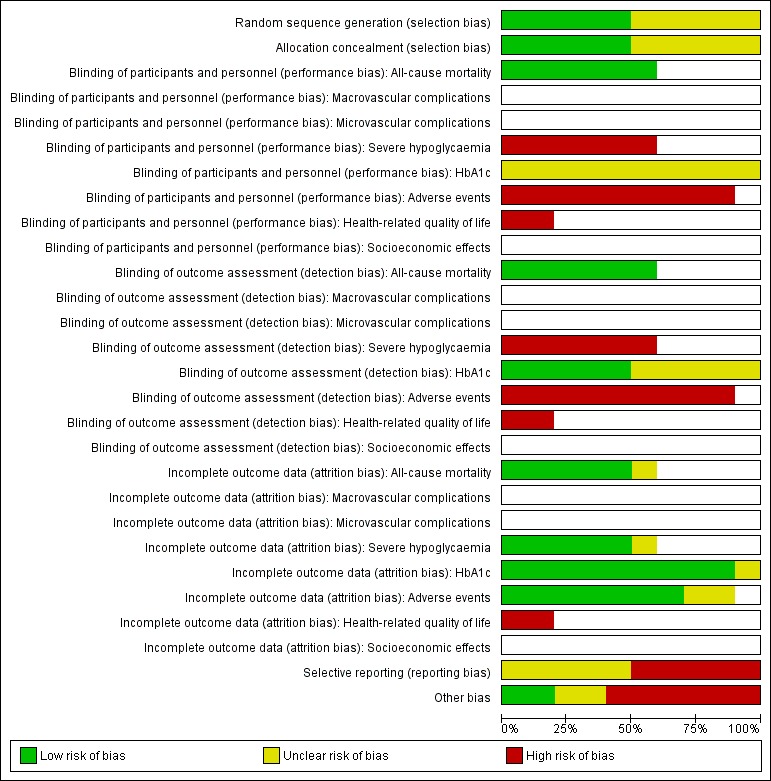

Risk of bias in included studies

For details on risk of bias of included studies see the 'Characteristics of included studies' table.

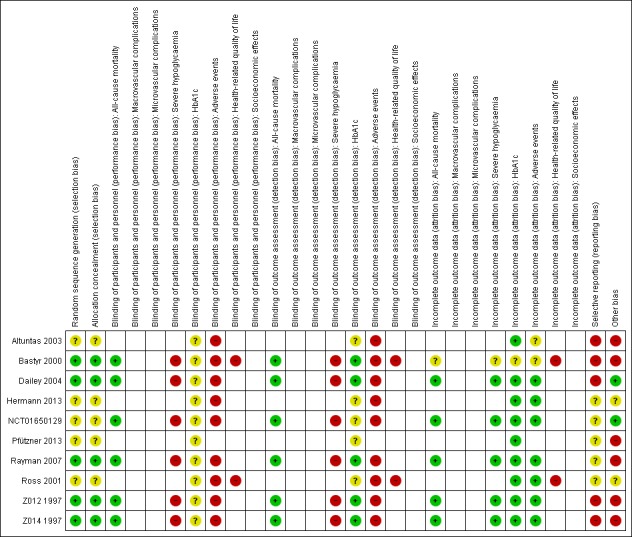

For an overview of review authors' judgments about each risk of bias item for individual trials and across all trials see Figure 2 and Figure 3.

Figure 2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included trials (note that not all trials measured all outcomes)

Figure 3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study (note that not all trials measured all outcomes)

We investigated performance bias, detection bias, and attrition bias separately for each outcome measure.

Allocation

We considered the random sequence generation and allocation concealment as adequate in five trials (Bastyr 2000; Dailey 2004; Rayman 2007; Z012 1997; Z014 1997). The other trials did not provide sufficient information on their methods.

Blinding

All trials were open‐label designs. The open‐label design was commonly chosen because according to prescribing information, regular human insulin should be injected 30 to 45 minutes before meals, while short‐acting insulin analogues can be injected immediately before a meal. An open‐label study design, especially with no blinded outcome assessment and poor or unclear concealment of allocation, carries an increased risk of bias.

None of the trials provided explicit information on a blinded outcome assessment. Where measured, all except HbA1c, were patient‐reported, investigator assessed, or both. For five trials, assessment of HbA1s was conducted in central laboratories (Bastyr 2000; Dailey 2004; Rayman 2007; Z012 1997; Z014 1997). Therefore, we assumed a blinded outcome assessment, and considered these trials to carry a low risk of detection bias for this outcome measure. None of the other trials provided information on HbA1c assessment, so we assumed an unclear risk of bias.

We assumed a low risk of bias for the outcome all‐cause mortality (Bastyr 2000; Dailey 2004; NCT01650129; Rayman 2007; Z012 1997; Z014 1997).

Because of the open‐label design, and because they were patient‐reported, investigator assessed, or both, we judged the outcomes severe hypoglycaemia and adverse events to carry a high risk of bias, when they were reported.

Because of the open‐label design, we judged the outcome health‐related quality of life as having a high risk of bias for Bastyr 2000 and Ross 2001.

None of the included trials reported on macrovascular or microvascular complications.

Incomplete outcome data

The proportion of participants lost to follow‐up ranged from 0% (Altuntas 2003; Hermann 2013; Pfützner 2013), to 16% (Bastyr 2000). The trials either did not report the method used for imputing missing data, or reported a method that was not in keeping with current recommended practice, such as multiple imputation.

All‐cause mortality

We judged attrition bias as low for five trials (Dailey 2004; NCT01650129; Rayman 2007; Z012 1997; Z014 1997). For the other five trials, the risk remained unclear, because either the outcome was not reported or insufficient information was available.

Microvascular and macrovascular complications

None of the included trials reported on these outcomes.

Severe hypoglycaemic episodes

We judged attrition bias as low for five trials (Dailey 2004; NCT01650129; Rayman 2007; Z012 1997; Z014 1997). For the other five trials, the risk remained unclear, because either the outcome was not reported or insufficient information was available.

HbA1c

We judged attrition bias as low for nine of the ten trials. For Bastyr 2000, the risk remained unclear because insufficient information on the number of analysed participants was available.

Adverse events other than severe hypoglycaemic episodes

We judged attrition bias as low for seven trials. For three trials, the risk remained unclear, because either the outcome was not reported or insufficient information on the number of analysed participants was available (Altuntas 2003; Bastyr 2000; Pfützner 2013).

Health‐related quality of life

We judged attrition bias as high for Bastyr 2000 and Ross 2001. None of the other trials reported this outcome.

Socioeconomic effects

None of the included trials reported on these outcomes.

Selective reporting

Since some study protocols were not available, it was generally difficult to judge risk of bias due to selective reporting. However, for most of the trials, we found outcomes mentioned in the abstract, methods section, or other documents related to the trial not sufficiently reported in the results section. Therefore, we judged all trials as having an unclear or high risk of bias regarding selective reporting. Risk of reporting bias was high in five trials (Altuntas 2003; Bastyr 2000; Dailey 2004; Z012 1997; Z014 1997).

Other potential sources of bias

Regarding other sources of bias, we considered the lack of definition of a primary outcome and the inconsistent or clearly erroneous presentation of data as a potential risk. Six trials did not clearly define a primary outcome (Altuntas 2003; Bastyr 2000; Hermann 2013; Ross 2001; Z012 1997; Z014 1997). In three trials the presentation of data contained substantial errors or inconsistencies, so we judged these three trials to have a high risk of bias in this category (Altuntas 2003; Bastyr 2000; Rayman 2007). Pfützner 2013 was a pilot project with very few participants, which was only published as a poster and conference abstract. For Z012 1997 and Z014 1997, only results for pooled analyses were available from the original publication (Anderson 1997). The authors did not inform readers that these were results from pooled analyses. Therefore, we judged these three trials as also having a high risk of bias.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Baseline characteristics

For details on baseline characteristics, see Appendix 5 and Appendix 6.

Primary outcomes

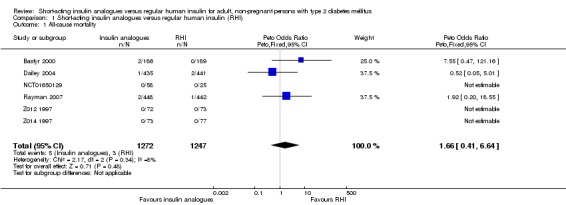

All‐cause mortality

None of the included trials defined all‐cause mortality as a primary outcome, but information on the number of participants who died during the trial was available for all but two trials (Altuntas 2003; Ross 2001). In Hermann 2013 and Pfützner 2013, the number of deaths was not explicitly reported, but we assumed it was zero, based on the presentation of the results (see Appendix 8). Overall, events were rare; across trials, there were five deaths out of 1272 participants in the insulin analogues groups (0.4%) and three deaths out of 1247 participants in the regular human insulin groups (0.2%), Peto odds ratio (POR) 1.66 (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.47 to 6.64); P = 0.48; 3 trials, 2519 participants; Analysis 1.1; moderate‐certainty evidence.

Analysis 1.1.

Comparison 1 Short‐acting insulin analogues versus regular human insulin (RHI), Outcome 1 All‐cause mortality.

There was no clear difference between the different types of insulin (Analysis 1.2).

Analysis 1.2.

Comparison 1 Short‐acting insulin analogues versus regular human insulin (RHI), Outcome 2 All‐cause mortality for different types of insulin.

Microvascular and macrovascular complications

None of the included trials reported on microvascular or macrovascular complications.

Severe hypoglycaemic episodes

Six trials reported severe hypoglycaemic episodes. Although three trials had explicitly defined severe hypoglycaemic episodes as either a primary or secondary outcome (Dailey 2004; Rayman 2007; Ross 2001), only two of these trials (Dailey 2004; Rayman 2007) reported results accordingly. Four other trials reported on severe hypoglycaemic events as part of their safety data (Bastyr 2000; NCT01650129; Z012 1997; Z014 1997). The reporting of severe hypoglycaemia across trials was diverse. Authors reported the overall number of participants with severe hypoglycaemic episodes in two trials (Dailey 2004; Rayman 2007). In three trials, information on severe hypoglycaemia was only available for participants who experienced coma, were treated with intravenous glucose, or were given glucagon separately (Bastyr 2000; Z012 1997; Z014 1997). In Dailey 2004, the number of participants with severe hypoglycaemic episodes was reported for the last two months of the trial only. The definition of severe hypoglycaemia differed somewhat between trials, but was mostly associated with the necessity of third party help, intravenous glucose infusions, glucagon administration, recovery after oral carbohydrate intake, or the occurrence of coma.

Overall, the incidence of severe hypoglycaemic events was low, and no trial showed a clear difference between the two treatment arms. In the three insulin lispro trials, coma occurred in two of the 327 participants in the intervention groups (0.6%) and in five of the 333 participants in the control groups (1.5% (Bastyr 2000; Z012 1997; Z014 1997)). Four participants needed intravenous glucose, and one participant in each of the intervention and control groups needed glucagon. In Rayman 2007, six of 448 glulisine‐treated participants and 14 of 442 participants taking regular human insulin experienced a severe hypoglycaemic episode. In Dailey 2004, six of 435 glulisine‐treated participants and five of the 441 participants in the control group experienced severe hypoglycaemia during the last two months of follow‐up. In NCT01650129, two out of 58 aspart‐treated participants and one of 25 participants taking regular human insulin experienced severe hypoglycaemic episodes.

Because of the diverse reporting of severe hypoglycaemic episodes and the small number of events, we did not conduct a meta‐analysis. Overall, there was no clear difference between the number of severe hypoglycaemic episodes experienced by those taking short‐acting insulin analogues and those taking regular human insulin (low‐certainty evidence).

Secondary outcomes

Glycaemic control (HbA1c)

One trial had to be excluded from the analyses of HbA1c, since the treatment groups were inconsistently labelled in different tables, we were unable to attribute the reported HbA1c results to the appropriate treatment arm (Altuntas 2003). Dailey 2004 and Pfützner 2013 did not report a standard deviation (SD) for the mean HbA1 at endpoint, so we used the baseline SD in the treatment groups instead.

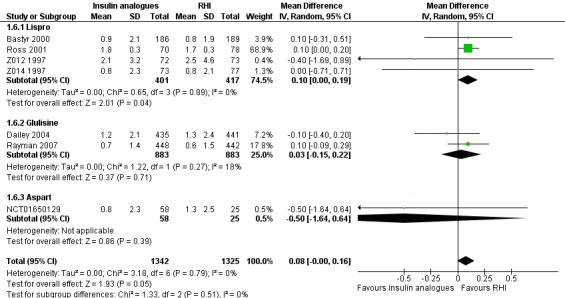

The mean difference (MD) in the change of HbA1c between short‐acting insulin analogue and regular human insulin was ‐0.03% (95% CI ‐0.16 to 0.09); P = 0.60; 9 trials, 2608 participants; Analysis 1.3; low‐certainty evidence. The 95% prediction interval ranged between ‐0.31% and 0.25%. There was no clear difference between the different types of insulin (Analysis 1.4; Figure 4).

Analysis 1.3.

Comparison 1 Short‐acting insulin analogues versus regular human insulin (RHI), Outcome 3 HbA1c changes.

Analysis 1.4.

Comparison 1 Short‐acting insulin analogues versus regular human insulin (RHI), Outcome 4 HbA1c changes for different types of insulin.

Figure 4.

Forest plot of comparison: Short‐acting insulin analogues versus regular human insulin (RHI); outcome 1.4. HbA1c changes for different types of insulin (%)

Adverse events other than sever hypoglycaemic episodes

All non‐severe hypoglycaemic episodes

All but one trial reported on overall hypoglycaemic events (Pfützner 2013). Hypoglycaemic events were usually defined as the participant experiencing symptoms typically associated with hypoglycaemia. In four of the trials, hypoglycaemic events could also be counted if blood glucose measured below a certain value (Altuntas 2003; Bastyr 2000; Z012 1997; Z014 1997). This value varied between 36 mg/dL and 63 mg/dL (2.0 mmol/mL and 3.5 mmol/mL) across trials. The authors did not define hypoglycaemic episodes in Hermann 2013.

We excluded two trials from the meta‐analysis because the unit of measurement was unclear, or was defined in a way that did not allow the results to be pooled (Altuntas 2003; Hermann 2013). Altuntas 2003 reported an increase in the overall hypoglycaemia rate in the lispro group compared to the regular human insulin group (0.57% versus 0.009%). However, the units to which the reported numbers referred were unclear. Hermann 2013 reported that five of 18 participants treated with insulin aspart experienced up to three hypoglycaemic episodes per year compared to three of 11 participants treated with regular human insulin.

For the remaining seven trials, we summarised results provided as mean episodes per participant per month. NCT01650129 reported the mean rate of hypoglycaemic episodes, but did not provide a measure of variance. Therefore, we imputed the SD from the mean SD of all other included trials (sensitivity analyses using the minimum and maximum SDs from other trials resulted in similar results; data not shown).

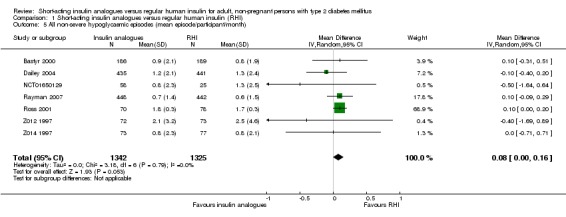

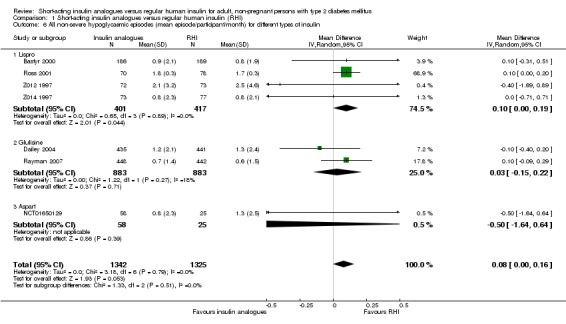

The MD of the overall mean hypoglycaemic episodes per participant per month was 0.08 episode (95% CI ‐0.00 to 0.16); P = 0.05; 7 trials, 2667 participants; Analysis 1.5; very low‐certainty evidence. The 95% prediction interval ranged between ‐0.03 and 0.19. There was no clear difference between the different types of insulin (Analysis 1.6; Figure 5).

Analysis 1.5.

Comparison 1 Short‐acting insulin analogues versus regular human insulin (RHI), Outcome 5 All non‐severe hypoglycaemic episodes (mean episode/participant/month).

Analysis 1.6.

Comparison 1 Short‐acting insulin analogues versus regular human insulin (RHI), Outcome 6 All non‐severe hypoglycaemic episodes (mean episode/participant/month) for different types of insulin.

Figure 5.

Forest plot of comparison: Short‐acting insulin analogues versus regular human insulin (RHI); outcome 1.6. All non‐severe hypoglycaemic episodes (mean episode/participant/month) for different types of insulin

Overall, none of the trials assessed hypoglycaemia in a blinded manner. The reporting of symptoms and the decision to carry out a blood glucose measurement are highly subjective, therefore, the results are at a high risk of bias and should be interpreted with caution.

Nocturnal hypoglycaemia

Four trials measured nocturnal hypoglycaemic episodes (Bastyr 2000; Dailey 2004; Rayman 2007; Ross 2001). Nocturnal hypoglycaemic episodes were either defined as those occurring between midnight and 6:00 am (Bastyr 2000; Ross 2001), or more generally, as events occurring at night or during sleep (Dailey 2004; Rayman 2007). Trial authors reported results using different units (such as number of participants with more than one episode per year, number of participants with at least one episode during the whole study period or just the last two months, number of episodes per participant per month, or number of episodes per participant per year), which made a meta‐analysis not feasible. Apart from Rayman 2007, who distinguished between overall and severe nocturnal hypoglycaemic episodes, no information was provided regarding the severity of recorded events.

Bastyr 2000 reported on nocturnal hypoglycaemic events, even though the original study report did not mention this outcome; therefore, we assumed that it was a retrospective analysis of the data (IQWIG 2005). There was no clear difference between groups in the number of participants without any events; no statistics were reported for the comparison of participants with one event (lispro 10.4% and regular human insulin 13.7%), or more than one event (lispro 9.3% and regular human insulin 8.2%). Ross 2001 reported 0.08 nocturnal episodes per participant per 30 days for the lispro group versus 0.16 for the regular human insulin group (P = 0.057). The two trials on glulisine reported the number of participants with at least one nocturnal hypoglycaemic episode (Dailey 2004; Rayman 2007). While Dailey 2004 found no clear difference in overall nocturnal hypoglycaemic episodes between the two groups, Rayman 2007 found a higher number of participants who were taking regular human insulin who reported at least one episode of symptomatic nocturnal hypoglycaemia compared to those taking insulin analogues; there was no clear difference between groups for severe events. However, Rayman 2007 reported hypoglycaemia results based on the last two trial months only. In the original study report, results for nocturnal hypoglycaemic episodes were presented for the full study period; these results were very similar between groups (symptomatic hypoglycaemia: 95 participants (21.2%) in the intervention group versus 100 participants (22.6%) in the control group with at least one episode; severe hypoglycaemia: three participants (0.7%) in the intervention group versus five participants (1.1%) in the control group with at least one episode).

Weight gain

All but one trial provided some data on weight gain in the two treatment groups (Pfützner 2013). However, in Altuntas 2003, there were discrepancies in the reporting of the results, so it was not clear which results belonged to which treatment arm. Hermann 2013 only presented results on the change of BMI, and reported no clear differences between treatment groups. NCT01650129 only stated that no treatment differences were observed, without reporting the results in detail. For the remaining trials, participants gained, on average, between 2 kg and 5 kg over the trial period. The amount of weight gain was similar for both groups in all trials. Since only three trials provided measures of variance of the weight gain, and trial durations differed, we decided not to pool results in a meta‐analysis (Bastyr 2000; Z012 1997; Z014 1997).

Other adverse events

Most trials provided at least some information on adverse events. The majority of adverse events were mild, and the frequency and type of events was generally similar for the two treatment groups. The attrition rate because of adverse events varied between 0% and 4%, and was comparable between the two treatment arms in all trials. Ross 2001 reported the attrition rate because of adverse events for the overall trial sample only.

Four trials reported hyperglycaemic events (symptomatic or severe) as part of the safety data, which occurred only rarely (range across trials: 0% to 1.6% of participants with at least one event (Bastyr 2000; Rayman 2007; Z012 1997; Z014 1997)). Two trials measured events of ketoacidosis (Bastyr 2000; Rayman 2007). Bastyr 2000 reported that one participant in the lispro group (0.5%) experienced a ketoacidotic coma; in Rayman 2007, ketoacidosis occurred in 0.2% of the participants in the glulisine group, but there were no cases in the control group.

Finally, no clinically relevant differences were noted for vital signs, physical parameters, results of electrocardiography, or clinical laboratory findings. None of the trials provided information on carcinogenicity.

Health‐related quality of life