Abstract

Background

During intensive care unit (ICU) admission, patients and their carers experience physical and psychological stressors that may result in psychological conditions including anxiety, depression, and post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Improving communication between healthcare professionals, patients, and their carers may alleviate these disorders. Communication may include information or educational interventions, in different formats, aiming to improve knowledge of the prognosis, treatment, or anticipated challenges after ICU discharge.

Objectives

To assess the effects of information or education interventions for improving outcomes in adult ICU patients and their carers.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, and PsycINFO from database inception to 10 April 2017. We searched clinical trials registries and grey literature, and handsearched reference lists of included studies and related reviews.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs), and planned to include quasi‐RCTs, comparing information or education interventions presented to participants versus no information or education interventions, or comparing information or education interventions as part of a complex intervention versus a complex intervention without information or education. We included participants who were adult ICU patients, or their carers; these included relatives and non‐relatives, including significant representatives of patients.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed studies for inclusion, extracted data, assessed risk of bias, and applied GRADE criteria to assess certainty of the evidence.

Main results

We included eight RCTs with 1157 patient participants and 943 carer participants. We found no quasi‐RCTs. We identified seven studies that await classification, and three ongoing studies.

Three studies designed an intervention targeted at patients, four at carers, and one at both patients and carers. Studies included varied information: standardised or tailored, presented once or several times, and that included verbal or written information, audio recordings, multimedia information, and interactive information packs. Five studies reported robust methods of randomisation and allocation concealment. We noted high attrition rates in five studies. It was not feasible to blind participants, and we rated all studies as at high risk of performance bias, and at unclear risk of detection bias because most outcomes required self reporting.

We attempted to pool data statistically, however this was not always possible due to high levels of heterogeneity. We calculated mean differences (MDs) using data reported from individual study authors where possible, and narratively synthesised the results. We reported the following two comparisons.

Information or education intervention versus no information or education intervention (4 studies)

For patient anxiety, we did not pool data from three studies (332 participants) owing to unexplained substantial statistical heterogeneity and possible clinical or methodological differences between studies. One study reported less anxiety when an intervention was used (MD ‐3.20, 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐3.38 to ‐3.02), and two studies reported little or no difference between groups (MD ‐0.40, 95% CI ‐4.75 to 3.95; MD ‐1.00, 95% CI ‐2.94 to 0.94). Similarly, for patient depression, we did not pool data from two studies (160 patient participants). These studies reported less depression when an information or education intervention was used (MD ‐2.90, 95% CI ‐4.00 to ‐1.80; MD ‐1.27, 95% CI ‐1.47 to ‐1.07). However, it is uncertain whether information or education interventions reduce patient anxiety or depression due to very low‐certainty evidence.

It is uncertain whether information or education interventions improve health‐related quality of life due to very low‐certainty evidence from one study reporting little or no difference between intervention groups (MD ‐1.30, 95% CI ‐4.99 to 2.39; 143 patient participants). No study reported adverse effects, knowledge acquisition, PTSD severity, or patient or carer satisfaction.

We used the GRADE approach and downgraded certainty of the evidence owing to study limitations, inconsistencies between results, and limited data from few small studies.

Information or education intervention as part of a complex intervention versus a complex intervention without information or education (4 studies)

One study (three comparison groups; 38 participants) reported little or no difference between groups in patient anxiety (tailored information pack versus control: MD 0.09, 95% CI ‐3.29 to 3.47; standardised general ICU information versus control: MD ‐0.25, 95% CI ‐4.34 to 3.84), and little or no difference in patient depression (tailored information pack versus control: MD ‐1.26, 95% CI ‐4.48 to 1.96; standardised general ICU information versus control: MD ‐1.47, 95% CI ‐6.37 to 3.43). It is uncertain whether information or education interventions as part of a complex intervention reduce patient anxiety and depression due to very low‐certainty evidence.

One study (175 carer participants) reported fewer carer participants with poor comprehension among those given information (risk ratio 0.28, 95% CI 0.15 to 0.53), but again this finding is uncertain due to very low‐certainty evidence.

Two studies (487 carer participants) reported little or no difference in carer satisfaction; it is uncertain whether information or education interventions as part of a complex intervention increase carer satisfaction due to very low‐certainty evidence. Adverse effects were reported in only one study: one participant withdrew because of deterioration in mental health on completion of anxiety and depression questionnaires, but the study authors did not report whether this participant was from the intervention or comparison group.

We downgraded certainty of the evidence owing to study limitations, and limited data from few small studies.

No studies reported severity of PTSD, or health‐related quality of life.

Authors' conclusions

We are uncertain of the effects of information or education interventions given to adult ICU patients and their carers, as the evidence in all cases was of very low certainty, and our confidence in the evidence was limited. Ongoing studies may contribute more data and introduce more certainty when incorporated into future updates of the review.

Plain language summary

Information for adult intensive care unit patients and their carers

Background

During intensive care unit (ICU) admission, patients and their carers experience physical and psychological stressors that may lead to increased anxiety, depression, and post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Improving communication among patients, their carers, and doctors, nurses, and other ICU staff may improve these outcomes. Communication may include information or educational interventions, in different formats, which aim to improve knowledge of the patient's condition, their treatment plan, or challenges they may face after ICU discharge.

Study characteristics

The evidence is current up to 10 April 2017. We included eight studies with 1157 ICU patients and 943 carers of ICU patients. Seven studies are awaiting classification because we could not assess their eligibility, and three studies are ongoing. We included studies that assessed information given to patients or their carers compared to no information, and studies that assessed information as part of a more complex intervention compared to a complex intervention that did not include information or education. Studies included varied information: standardised or tailored to the individual, given regularly or on a single occasion, and that included verbal or written information, audio recordings, multimedia information, and interactive information packs.

Key results

Overall, it is uncertain whether information or education (given alone or as part of a more complex intervention) improves outcomes for patients and their carers following a stay in the ICU. For patients, it is uncertain whether or not information or education reduces anxiety or depression, or improves health‐related quality of life. One patient asked to withdraw from the study because they believed that their mental health worsened when they completed a questionnaire to assess anxiety and depression, but it is not clear whether this person received the information intervention or not. No studies reported PTSD in patients. For carers, it is uncertain whether or not information or education reduces anxiety or depression or improves carers' knowledge acquisition or their satisfaction with information provided.

Quality of the evidence

It was not possible for researchers to mask patients and carers to the intervention they received, and it was unclear whether this would affect the results, which relied on self assessments. Study authors did not consistently report rigorous methods for carrying out randomised trials, and we noted some losses of patients and carers during the studies. We found few small studies for this review, reporting limited data for many outcomes of interest. It is uncertain whether information or education is effective due to very low‐certainty evidence.

Conclusion

We are uncertain about the effects of information or education interventions given to adult ICU patients and their carers. The evidence was of very low certainty, and our confidence in the evidence was limited. We are aware of three ongoing studies and seven studies that were recently completed but not yet published. These studies may provide additional evidence or improve the certainty in the findings in future updates of the review.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

During intensive care unit (ICU) admission, patients experience a variety of physical and psychological stressors, which may result in psychological disorders including anxiety, depression, and post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Hofhuis 2008; Ringdal 2005; Wang 2009). Elevated and prolonged stress can also have detrimental consequences on other health outcomes, affecting wound healing and susceptibility to infection (Herbert 1993; Walburn 2009). The duration of psychological disorders frequently extends beyond discharge from the ICU (Ringdal 2005), and can impact a patient’s recovery as well as the mental health of carers or relatives (Davidson 2007). For example, reported anxiety and depression prevalence among people treated in ICUs ranges from 12% to 43% (Eddleston 2000; Scragg 2001), and 10% to 30% (Davydow 2009; Eddleston 2000; Scragg 2001), respectively. A recent meta‐analysis estimated that PTSD occurs in 20% of people treated in ICUs (Parker 2015). Family members of critically ill patients are also at risk of depression, anxiety, PTSD, and complicated grief (Haines 2015; Kross 2015). The prevalence of anxiety, depression, and PTSD in carers of people treated in ICUs is reported as ranging from 15% to 24%, 5% to 36%, and 35% to 57%, respectively (Van Beusekom 2016). Ineffective communication between healthcare professionals and patients/carers, or a lack of information, can exacerbate psychological disorders, both during and after an ICU stay (Magnus 2006).

Description of the intervention

Information or education interventions represent one type of communication intervention and include structured information programmes, information leaflets, face‐to‐face briefings, recorded messages, or use of online resources. These interventions aim to improve knowledge (e.g. of the condition, care, expected length of stay, or sources of support during recovery) and comprehension in patients and their carers in order to reduce anxiety and ultimately improve health outcomes (Azoulay 2002; Hofhuis 2008; Linton 2008). Information or education interventions may involve communication of important information from healthcare provider to patient, but can also incorporate elements of patient‐to‐provider communication whereby the intervention is tailored to the patient’s needs. Patients and carers who are not fluent or literate in the dominant language used by information providers may face additional challenges (Joint Commission 2007; Riley 2006; Schyve 2007). Timing of the intervention is also an important factor (Fleischer 2014). For example, interventions delivered during ICU admission may focus on the delivery of information to the carer (if the patient is incapacitated or unconscious), who then relays the information to the patient. Such an intervention is reliant on the carer's ability to comprehend and relay the correct information. In comparison, delivery of interventions at the point of discharge may involve both the patient and their carer.

How the intervention might work

There are several potential mechanisms through which information and education interventions might reduce anxiety. The provision of information and education (as a component of supportive communication) can reduce both cardiovascular reactivity (Thorsteinsson 1999), and levels of stress hormones such as cortisol (Floyd 2008). Supportive communication may also serve to encourage a stressed person to reappraise recent traumatic experiences, such as time spent in an ICU. By altering how people appraise stressful events, communication can ameliorate physiological and emotional responses to stress (Chadwick 2016).

Why it is important to do this review

Clinical guidelines recommend effective communication with critically ill patients and their families during admission to, and discharge from, the ICU. Patient‐centred discussions regarding their condition and steps that can be taken during a patient's recovery are also encouraged (NICE CG50). A number of controlled trials have examined the effects of education interventions for reducing anxiety and improving outcomes in critically ill patients, Azoulay 2002; Fleischer 2014; Hwang 1998; Linton 2008, and their carers (Douglas 2005). However, the findings of these trials are conflicting, which may relate to the timing or duration of the intervention. For example, Fleischer 2014 found no benefit (in terms of a reduction in anxiety) of an ICU‐specific single episode intervention (comprising face‐to‐face verbal communication) versus a non‐specific conversation of comparable length. In contrast, Hwang 1998 reported a reduction in anxiety for cardiac ICU patients who received an information intervention via audio recording. Both of these studies examined the effect of the interventions on depression and anxiety, but only Fleischer 2014 examined longer‐term well‐being, reporting no effect of the intervention on postdischarge quality of life. Despite the availability of data from individual trials, there are no available up‐to‐date syntheses of the evidence on education and information interventions for improving outcomes for ICU patients and their carers. Scheunemann 2011 performed a systematic review of randomised controlled trials of interventions to improve communication in intensive care. The review authors concluded that the evidence supported the use of printed information and structured communication by the ICU team. The use of ethics consultation, or palliative care consultation (e.g. about the appropriateness of aggressive medical treatments), improved emotional outcomes in family members and reduced the length of stay in the ICU and treatment intensity. However, whilst the review included studies where the focus was on determining the effects of information interventions, the review authors highlighted that few studies considered patient‐centred outcomes beyond mortality.

Our review served to re‐evaluate the available relevant evidence. Furthermore, our review focused on one aspect of communication interventions: information or education interventions. Information may be given at different time points (before an expected stay in the ICU, during an ICU stay, or after discharge from an ICU), and with different purposes. The time of an ICU stay may be especially distressing for patients and their carers, and their information needs especially high. We therefore chose to focus the review on this period of high need, considering as eligible any interventions aiming to provide information or education to these patients and their carers during the ICU stay. We included studies that provided communication interventions to enhance knowledge of the patient's prognosis and treatment plan, and information related to expected transition from the ICU; we did not consider studies that were designed to improve communication of decisions related to end‐of‐life care. The aim of this review was to reduce the uncertainty around whether information or education interventions are effective in improving knowledge and understanding, and ultimately short‐ and long‐term psychological health outcomes, in patients and their carers during and after their stay in an ICU. Additionally, improvements in short‐term outcomes potentially result in a shorter duration of stay in the ICU, and may thus reduce resource use.

Objectives

To assess the effects of information or education interventions for improving outcomes in adult ICU patients and their carers.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs). We planned to include quasi‐RCTs (i.e. trials in which randomisation is attempted but subject to potential manipulation, such as allocating participants by day of the week, date of birth, or sequence of entry into trial), with a parallel design. We included cluster RCTs to enable inclusion of studies that assign the ICU, rather than individual patients, to the intervention or control group/arm.

Types of participants

Adult (aged 18 years and above) ICU patients and critically ill patients in high‐dependency care units regardless of their status (e.g. conscious, unconscious, intubated) or length of stay. We also included carers of these patients (whether relatives or non‐relatives), because the psychological status of both can be affected by a patient’s critical illness and stay in the ICU (Davidson 2007; Haines 2015; Kross 2015).

If studies included adults and children, we included the study if the mean age of participants was 18 years or above.

Types of interventions

We included information or education interventions, which we defined as any intervention designed to improve a patient or carer's knowledge or understanding of the prognosis, treatment plan, or challenges likely to affect the patient during their transition from the ICU. Information or education interventions were delivered in different formats, such as written (e.g. leaflet), verbal (e.g. counselling), or digital (e.g. phone or tablet application, recorded message). We acknowledge the difficulties associated with delineating the definitions of information and education interventions (Kaufman 2018); for the purposes of this review, we essentially considered them as variants of the same thing. The intervention was additional or different to that provided in the comparator group (e.g. information pamphlet versus no information pamphlet). We required the intervention to be delivered by treating healthcare professionals (clinicians, nurses, or support teams).

We also included studies of more complex interventions, if part of the intervention involved the provision of information with the aim of improving a patient’s knowledge or understanding of the topics listed above, and provision was more than that delivered in the comparator group (i.e. if the effects of the information or education intervention could be isolated from the rest of the complex intervention). Finally, we also included studies that employed ‘sham’ controls (e.g. where patients were assigned to receive an ICU‐specific pamphlet versus a non‐specific pamphlet).

We included studies in which the intervention was given whilst the patient was critically ill in the ICU. We excluded studies in which the intervention was given before the ICU stay (i.e. before critical illness) and after the ICU stay (i.e. to a survivor of critical illness).

We excluded studies that assessed the effectiveness of patient diaries because patient diaries provided retrospective information to the patient about what they had experienced during their stay, rather than the provision of information aiming to increase a patient or carer's knowledge about what they should expect whilst they are in the ICU and as they transition from the ICU. We excluded information that was provided as part of managing end‐of‐life care.

We included the following comparisons:

information or education intervention versus no information or education intervention; and

information or education intervention as a part of a complex intervention (e.g. information or education intervention plus support) versus complex intervention without information or education (e.g. support alone).

The intervention was presented to either the patient, carer, or both.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Severity of anxiety in patients (assessed with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) or other validated method).

Severity of depression in patients (assessed with the HADS or other validated method).

Knowledge acquisition (patients and carers).

Secondary outcomes

Severity of PTSD in patients treated in ICUs (assessed using the Impact of Event Scale‐Revised (IES‐R) or other validated tool).

Severity of depression in carers (assessed using the HADS or other validated tool).

Severity of anxiety in carers (assessed using the HADS or other validated tool).

Patient or carer satisfaction with information provided (e.g. self reported).

Health‐related quality of life (HRQoL) (measured with a validated quality of life questionnaire such as EQ‐5D or Short Form‐36 (SF‐36)).

Length of stay in ICU.

Adverse effects.

Where more than one outcome measure was presented per outcome (for example, EQ‐5D and SF‐36 for HRQoL), we planned to select the primary outcome measure that was identified by the publication authors. Where no primary outcome measure was identified, we planned to select the measure specified in the sample size calculation. If there was no sample size calculation, we planned to rank the effect estimates (i.e. list them in order from largest to smallest) and select the median effect estimate; where there was an even number of outcome measures, we planned to select the measure whose effect estimate was ranked n/2 (where n is the number of outcomes).

We extracted data for all outcomes at their last reported time point.

The reporting of one or more of the outcomes listed above was not an inclusion criterion for this review.

Main outcomes for 'Summary of findings' tables

We reported the primary outcomes and the severity of PTSD in patients treated in ICUs, patient or carer satisfaction with the information provided, HRQoL, and adverse effects, in 'Summary of findings' tables.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following electronic databases:

the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), the Cochrane Library, issue 3, 2017;

MEDLINE OvidSP (1946 to 10 April 2017);

Embase OvidSP (1974 to 10 April 2017);

PsycINFO OvidSP (1806 to 10 April 2017); and

CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature) EBSCO (1937 to 10 April 2017).

We conducted a preliminary search in CENTRAL on 17 January 2017 using the CENTRAL scoping search strategy (Appendix 1) whilst the tailored database searches were being finalised. On 10 April 2017, we ran the finalised search strategies for the following databases: CENTRAL (Appendix 2), MEDLINE (Appendix 3), Embase (Appendix 4), PsycINFO (Appendix 5), and CINAHL (Appendix 6). The results from the CENTRAL scoping search were combined with results of the finalised search strategies, and all duplicates were removed.

We also searched the US National Institutes of Health Ongoing Trials Register ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov) and the World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (www.who.int/ictrp/en/) on 24 March 2017 for ongoing and recently completed studies. We searched all databases with no restriction on region or language of publication.

Searching other resources

We checked the references of all relevant primary studies and review articles (from 2010 onwards) to identify additional studies that might have been relevant to the review. We contacted authors of included studies for advice about other relevant studies.

We conducted a grey literature search through OpenGrey (www.opengrey.eu./) on 31 August 2017.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently screened all titles and abstracts identified by the searches to determine which met the inclusion criteria, retrieving the full texts of any papers considered to be potentially relevant. Two review authors independently screened the full‐text articles for inclusion or exclusion. Any discrepancies were resolved by discussion until consensus was reached, or through consultation with a third review author where necessary. We categorised all potentially relevant papers excluded from the review at this stage as excluded studies and provided the reasons for their exclusion in the Characteristics of excluded studies table. We also provided citation details and any available information about ongoing studies, and collated and reported details of duplicate publications, so that each study (rather than each report) was the unit of interest in the review. We reported the screening and selection process in an adapted PRISMA flow chart (Liberati 2009).

Data extraction and management

Two review authors extracted data independently from included studies. Any discrepancies were resolved by discussion until consensus was reached, or through consultation with a third review author where necessary. We developed and piloted a data extraction template and used Covidence to extract the following details of the included studies: funding source, declaration of interests for the primary investigators, aim of intervention, study design and duration, study setting, description of intervention and comparator (to include whether it was generic or personalised and frequency of intervention); the following patient participant characteristics by intervention/comparator group: number randomised, number excluded from analyses, age, gender body mass index, measure of illness (e.g. Acute Physiologic Assessment and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE‐II) score, Glasgow Coma score, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score), health literacy, and intubation status; and the following carer participant characteristics by intervention/comparator group: age, gender, relationship to patient participant, and health literacy status (Covidence). We used this information to populate Characteristics of included studies tables. We also extracted outcome data from the results of the included studies (see Primary outcomes and Secondary outcomes). We imported extracted data in Covidence into Review Manager 5 (Covidence; Review Manager 2014).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed and reported on the methodological risk of bias of included studies in accordance with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions and the Cochrane Consumers and Communication guidelines (Higgins 2011; Ryan 2013), which recommend the explicit reporting of the following individual elements for RCTs: random sequence generation; allocation sequence concealment; blinding (participants, personnel); blinding (outcome assessment); completeness of outcome data; selective outcome reporting; and other sources of bias (e.g. imbalances in baseline characteristics of intervention and comparator groups). We considered blinding separately for different outcomes where appropriate, and separately assessed risk of detection bias for patient‐related outcomes and carer‐related outcomes. We considered studies to have a high risk of bias if they reported a loss of more than 10% of patient or carer participants, and if the loss was not explained or was uneven between comparison groups. We considered risk of bias for selective recruitment in cluster RCTs, and whether analysis methods accounted for unit of randomisation, reporting this in the random sequence generation and other sources of bias domains. We did not complete 'Risk of bias' judgements for outcomes that were not reported. We judged each item as being at high, low, or unclear risk of bias as set out in the criteria described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011), and provided a quote from the study report and a justification for our judgement for each item in the 'Risk of bias' table in Characteristics of included studies. We planned to assess and report quasi‐RCTs as being at a high risk of bias for the random sequence generation item of the 'Risk of bias' tool.

A study was deemed as at high risk of bias if it was considered to be at high or unclear risk of bias for either the sequence generation or allocation concealment domain, based on growing empirical evidence that these factors are particularly important potential sources of bias (Higgins 2011). We planned to conduct sensitivity analyses excluding studies at unclear or high risk to investigate the effects of this decision on effect estimates for studies in which meta‐analyses were conducted. However, as we did not combine any data in meta‐analysis, we did not conduct this sensitivity analysis.

Two review authors independently assessed the risk of bias of included studies, with any disagreements resolved by discussion to reach consensus. We contacted study authors for additional information about the included studies or for clarification of the study methods as required. We incorporated the results of the 'Risk of bias' assessment into the review through standard tables, and systematic narrative description and commentary about each of the elements, leading to an overall assessment of the risk of bias of included studies and a judgement about the internal validity of the results of the review.

Measures of treatment effect

Although we did not conduct meta‐analysis in this review, we calculated the mean difference (MD) and 95% confidence interval (CI) for continuous outcomes in each study using the mean, standard deviation (SD), and number of people assessed for both the intervention and comparison groups as reported by study authors. We calculated the MD and 95% CI using the Review Manager 5 calculator (Review Manager 2014). If studies did not report a mean and SD, we presented measures (e.g. median and range) as reported by study authors. Again, we were unable to conduct meta‐analysis on dichotomous outcomes in this review. We calculated a risk ratio (RR) and 95% CI using number of events and the number of people assessed in the intervention and comparison groups in each study; we calculated RRs and 95% CI using the Review Manager 5 calculator (Review Manager 2014). We provided a narrative description of data reported by study authors, and when data were available using an appropriate measure, we included effect estimates for each study using the calculated MDs or RRs.

Unit of analysis issues

We did not include cross‐over trials in this review. Where multiple trial arms were reported in a single trial, we included only the relevant arms. If two comparisons (e.g. intervention A versus no intervention and intervention B versus no intervention) were combined in the same meta‐analysis, we planned to halve the control group (e.g. no intervention) to avoid double‐counting. If we included cluster RCTs, we planned to check for unit of analysis errors. We reported data if the participant was the unit of randomisation (rather than the study centre), and we planned that if unit of analysis errors were present, we would not combine data from cluster RCTs in meta‐analysis.

Dealing with missing data

We contacted study authors to obtain missing data (participant, outcome, or summary data). For participant data, we conducted analysis on an intention‐to‐treat basis where possible; otherwise we analysed data as reported. We reported on the levels of loss to follow‐up and assessed this as a source of potential bias.

For missing outcome or summary data, we planned to impute missing data where possible (for methods relevant to dichotomous data, see Higgins 2008) and report any assumptions in the review. We planned to investigate through sensitivity analyses the effects of any imputed data on pooled effect estimates.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We considered whether studies were sufficiently similar (based on consideration of populations, interventions, and setting) and assessed the degree of statistical heterogeneity by visual inspection of forest plots and by examining the Chi² test for heterogeneity. We quantified statistical heterogeneity using the I² statistic. An I² value of 50% or more is considered to represent substantial levels of heterogeneity, but we interpreted this value in light of the size and direction of effects and the strength of the evidence for heterogeneity (based on consideration of populations, interventions, and setting), using the P value from the Chi² test (Higgins 2011).

Where we detected substantial clinical, methodological, or statistical heterogeneity across included studies, we did not report pooled results from meta‐analysis but instead used a narrative approach to data synthesis. We attempted to explore possible clinical or methodological reasons for this variation by grouping studies that were similar in terms of populations, intervention features, or other factors, to explore differences in intervention effects.

Assessment of reporting biases

We assessed reporting bias qualitatively based on the characteristics of the included studies (e.g. if only small studies that indicate positive findings were identified for inclusion), and if information obtained from contact with study authors suggested that there were relevant unpublished studies.

We did not identify sufficient included studies (at least 10) to justify construction of a funnel plot to investigate small‐study effects and to assess the presence of publication bias (Sterne 2011).

Data synthesis

Our decision whether to meta‐analyse data was based on whether the interventions in the included trials were similar enough in terms of participants, settings, intervention, comparison, and outcome measures to ensure meaningful conclusions from a statistically pooled result.

Because we were unable to pool the data statistically using meta‐analysis for some outcomes, we conducted a narrative synthesis of results, and when possible used effect estimates for each study calculated using the Review Manager 5 calculator (Review Manager 2014). We presented the major outcomes and results, organised by outcome for each main comparison, and we presented data in tables and narratively summarised the results as reported by study authors.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

The effect of an information or education intervention might be expected to vary with different characteristics of the intervention itself, such as format (e.g. brochure versus one‐to‐one education session), frequency (e.g. a single verbal counselling session versus monthly sessions), specificity (e.g. tailored versus non‐tailored information), or information provider (e.g. doctor or nurse). The condition of the participant may also affect the participant's ability to receive or comprehend the information or education. For example, intubation status may influence the effectiveness of information interventions that are designed to be bidirectional between patient and healthcare provider, as the intubated patient would likely find it more difficult to communicate questions to the physician or nurse. We considered it unlikely that consciousness level would influence the results (and we did not perform a subgroup analysis by consciousness level) in as much as it would not be possible to deliver an information intervention to an unconscious patient. We did not exclude this population of patients, as the intervention may have a beneficial effect on the unconscious patient's carer. We therefore planned to perform subgroup analyses to investigate the following potential effect modifiers:

type of intervention: tailored versus non‐tailored;

type of intervention platform: verbal versus written versus digital;

category of information provider: doctor versus nurse versus psychologist versus support worker;

frequency of intervention: once (e.g. one‐off verbal counselling session) versus multiple sessions (e.g. monthly verbal counselling sessions); and

intubation status of the participant: intubated versus non‐intubated patients.

We presented a narrative form of subgroup analysis in the absence of pooled statistical data.

Sensitivity analysis

We did not carry out sensitivity analyses because we did not conduct meta‐analyses in this review.

'Summary of findings' tables

We prepared separate 'Summary of findings' tables to present the findings relating to each of the stated comparisons. We used the methods described in Chapter 11 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Schünemann 2011). For each table, we presented the results for the major comparisons of the review, for each of the major primary outcomes, including potential harms, as outlined in Types of outcome measures. We used the GRADE system to rank the certainty of the evidence using GRADEpro GDT software (GRADEpro GDT; Schünemann 2011). Through use of the GRADE system, we assessed the certainty of the evidence for each outcome on each of the following domains: study limitations, inconsistency, imprecision, indirectness, and publication bias. Two review authors independently assessed the certainty of the evidence as implemented and described in the GRADEpro software (GRADEpro GDT; Schünemann 2011). If meta‐analysis was not possible, we presented results in a narrative 'Summary of findings' table format, such as that used by Chan 2011.

Ensuring relevance to decisions in health care

The protocol and review received feedback from at least one consumer referee in addition to a health professional as part of the Cochrane Consumers and Communication Group’s standard editorial process. Additionally, a member of the review author team (DE) visited an ICU unit and ICU follow‐up clinic before drafting this protocol in order to better understand the challenges faced by critically ill patients and their relatives during the recovery process, and the types of education or information interventions currently available. The central theme of many of the discussions, that is that the provision of information was crucial to the psychological recovery of patients (and carers), emphasised the need for this review.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

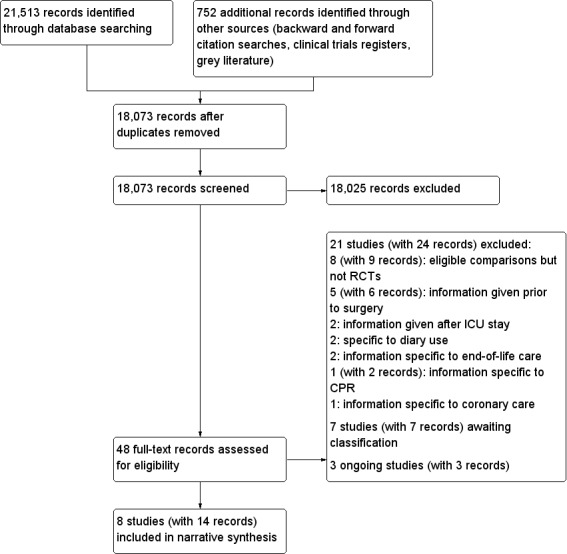

We screened 18,073 titles and abstracts from database searches, backward citation searches of relevant reviews, forward citation searches of eligible studies, searches of clinical trials registers, and grey literature searches. We considered the full‐text of 48 records. See Figure 1.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

See Characteristics of included studies.

We included eight RCTs; seven used a parallel design (Azoulay 2002; Carson 2016; Curtis 2016; Demircelik 2016; Fleischer 2014; Hwang 1998; Torke 2016), and one used a cluster parallel design (Bench 2015). We found no quasi‐RCTs.

Study population

We included studies that recruited participants who were patients in the ICU (we refer to these as patient participants) or family members, carers, or significant representatives of patients in the ICU (we refer to these as carer participants).

Studies had 1157 randomised patient participants and 943 randomised carer participants.

Participants were adults; one study recruited patient participants from 16 years of age, although the mean age indicated that most patient participants were older than 18 years of age (Hwang 1998). Carer participants included related family members (spouses, parents, siblings, and children), and unrelated significant representatives. We collected data on education level of patient and carer participants when available. Azoulay 2002, which was conducted in France, reported that all carer participants were able to speak French and that nine of 204 carer participants were healthcare professionals. Curtis 2016 reported education levels of carer participants, with eight out of 268 participants educated below high school level. Demircelik 2016 included 38 out of 100 patient participants with university level education. Hwang 1998 reported that 29 out of 60 patient participants were educated below middle school level. Torke 2016 reported education level as number of years of education, with a mean (SD) of 12.3 years (± 1.5) in the intervention group, and 15.5 years (± 2.6) in the control group. The remaining studies did not report education levels.

Study authors recruited patient participants with primary diagnoses: acute respiratory failure, shock, acute renal failure, or coma (Azoulay 2002); cardiovascular diseases (Demircelik 2016); and heart disease (Hwang 1998). The remaining studies did not report primary diagnoses. All patient participants were mechanically ventilated in Carson 2016 and Curtis 2016, and approximately a third of patient participants were mechanically ventilated in Fleischer 2014. We assumed from information in the full report that patient participants were also mechanically ventilated in Hwang 1998. The remaining studies did not report ventilation status.

Setting

All studies were conducted in the ICU; types of ICU were surgical (Azoulay 2002; Bench 2015; Fleischer 2014; Hwang 1998), medical (Azoulay 2002; Bench 2015; Carson 2016; Fleischer 2014; Torke 2016), coronary (Demircelik 2016), and trauma (Bench 2015; Curtis 2016). The studies were conducted in France, the UK, the USA, Germany, Taiwan, and Turkey.

Interventions

Three studies designed an intervention targeted at the patient participant (Demircelik 2016; Fleischer 2014; Hwang 1998). Four studies designed an intervention targeted at the carer participant (Azoulay 2002; Carson 2016; Curtis 2016; Torke 2016). One study designed an intervention targeted at both the patient and carer participant (Bench 2015).

We included studies for the two comparison groups. In summary, types of intervention were as follows.

Comparison 1: information or education intervention versus no information or education intervention

Nurses gave multimedia education training to patient participants versus no provision of information (Demircelik 2016).

Study nurses gave standardised and structured verbal information about the specific aspects of the ICU to the patient participant on the first day of the ICU stay versus a standardised non‐specific conversation of the same length (Fleischer 2014).

Audio message about the ICU and treatment plan recorded by physician and played to patient participant after heart surgery versus no information (Hwang 1998).

A Family Navigator was appointed to each carer participant to provide individualised information and support versus usual care (Torke 2016).

Comparison 2: information or education intervention as part of a complex intervention versus complex intervention without information or education

A family information leaflet given to carer participants at ICU admission alongside standard information that included daily meetings with the physician versus standard information only (Azoulay 2002). Because study authors described "standard information" in this study, which we believe was more enhanced than the description of standard care in other studies, we categorised this standard care as a complex intervention.

A User Centred Critical Care Discharge Information Pack (UCCDIP) that encouraged active participation given to patient and carer participants by bedside nurses and ad hoc verbal discharge information from healthcare professionals versus a standard ICU information booklet without discussion with bedside nurses and ad hoc verbal discharge information versus only ad hoc verbal discharge information (Bench 2015).

Structured family meetings led by palliative care team plus standard brochure and routine family meetings led by ICU clinicians versus standard brochure and routine family meetings led by ICU clinicians (Carson 2016).

Trained communication facilitator provided personalised information and emotional support to carer participant and opportunities to discuss concerns, and included information sharing with clinicians versus standardised verbal information about time in the ICU and the ICU transition (Curtis 2016).

Funding sources

Funding sources were reported in six studies with no conflicts of interest (Azoulay 2002; Bench 2015; Carson 2016; Curtis 2016; Fleischer 2014; Torke 2016). Two studies did not report funding sources (Demircelik 2016; Hwang 1998).

Excluded studies

We excluded 21 studies. See Characteristics of excluded studies.

We excluded eight studies that described relevant information interventions given to carers or patients in the ICU and were not RCTs (Barnett 2011; Chien 2006; Daly 2010; Medland 1998; Mistraletti 2017; Mitchell 2004; Othman 2016; White 2012). We excluded five studies in which healthcare professionals provided information to elective surgical patients and their carers prior to the ICU stay (Berg 2006; Guo 2012; Lai 2016; Lynn‐McHale 1997; Shin 2017); these studies were not RCTs. We excluded two RCTs in which healthcare professionals provided information after the ICU stay (Jones 2003; Walsh 2012). We excluded two studies in which caregivers and family members used a diary during the ICU stay, which was equivalent to information provision after the ICU stay (Garrouste‐Orgeas 2010; Jones 2009). We excluded two RCTs in which healthcare professionals provided information to carers related to bereavement and end‐of‐life decisions for ICU patients (Kirchhoff 2008; Lautrette 2007). We excluded one RCT in which healthcare professionals provided information to carers related specifically to cardiopulmonary resuscitation of ICU patients (Wilson 2015), and one study in which patients were in a coronary care unit and information was related specifically to cardiac patient health and disease management (Weibel 2016).

Studies awaiting classification

We were unable to assess eligibility for seven studies (Herlihy 2014; IRCT201111148100N1; IRCT2014102819728N1; McCarthy 2017; NCT01147978; NCT02067559; NCT02415634). See Characteristics of studies awaiting classification.

We identified five studies during searches of clinical trials registers; these studies were completed, but published reports of the results were not available (IRCT201111148100N1; IRCT2014102819728N1; NCT01147978; NCT02067559; NCT02415634). Two studies were published as abstracts with insufficient information (Herlihy 2014; McCarthy 2017).

Ongoing studies

We identified three ongoing studies from clinical trial register searches (NCT01982877; NCT02445937; NCT02931851). See Characteristics of ongoing studies.

Study authors describe interventions that involve family meetings with trained healthcare professionals (NCT01982877; NCT02445937), and use of a website to provide information to patient and carer participants (NCT02931851).

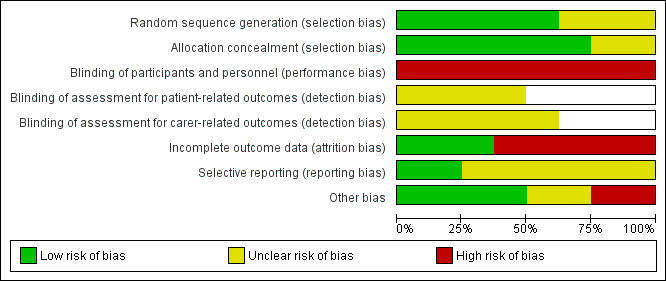

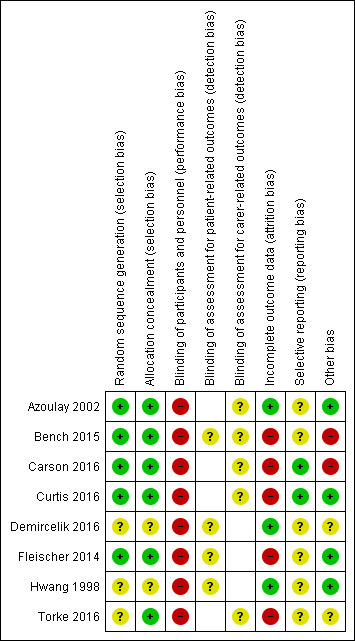

Risk of bias in included studies

See 'Risk of bias' graph (Figure 2) and 'Risk of bias' summary (Figure 3).

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study. Blank spaces indicate that outcome was not measured by study authors.

Allocation

All studies were described as randomised, and five studies provided sufficient details on the method of randomisation (Azoulay 2002; Bench 2015; Carson 2016; Curtis 2016; Fleischer 2014); we judged these studies as having a low risk of bias. Three studies provided no details on method of randomisation, and we judged risk of bias as unclear (Demircelik 2016; Hwang 1998; Torke 2016).

Six studies provided sufficient details about methods used to conceal allocation from healthcare professionals (Azoulay 2002; Bench 2015; Carson 2016; Curtis 2016; Fleischer 2014; Torke 2016); we judged these studies as having a low risk of bias. Two studies provided no details, and we judged risk of bias as unclear (Demircelik 2016; Hwang 1998).

Blinding

It was not feasible to blind participants and healthcare professionals to the intervention, and we judged all studies as having a high risk of performance bias. Most outcome assessments involved patient or carer responses to interview questions or self completion of questionnaires. We were unable to judge whether lack of participant blinding could influence outcome assessment, and assessed risk of detection bias as unclear for both patient participant‐ and carer participant‐related outcomes in all studies. We did not assess risk of bias for outcomes that were not reported; these are indicated by blank spaces in the 'Risk of bias' summary (Figure 3).

Incomplete outcome data

We judged three studies as having a low risk of bias because we noted few or no participant losses (Azoulay 2002; Demircelik 2016; Hwang 1998). We judged five studies as having a high risk of bias because they reported high attrition rates (loss of > 10%) among carer participants, and imbalance between groups or in reasons for participant loss (Bench 2015; Carson 2016; Curtis 2016; Fleischer 2014; Torke 2016).

Selective reporting

Two studies had prospective registration with clinical trials registers, and we noted that outcomes in clinical trials registration documents were the same as the reported outcomes (Carson 2016; Curtis 2016); we judged these studies as having a low risk of selective reporting bias. Two studies had retrospective registration with clinical trials registers, and it was not feasible to judge risk of selective reporting bias using these documents (Bench 2015; Fleischer 2014); we judged these studies as at unclear risk of selective reporting bias. We were unable to source clinical trials registration documents for four studies (Azoulay 2002; Demircelik 2016; Hwang 1998; Torke 2016), and it was not feasible to judge risk of bias; we assessed these studies as having an unclear risk of selective reporting bias.

Other potential sources of bias

In one study, the control group was given a verbal "ad hoc" intervention that was not standardised, which introduced a high risk of bias because participants in the control group may have received additional information (Bench 2015). In addition, we considered the effect of the cluster design of Bench 2015 in this review; study authors reported data with the participant as the unit of randomisation, but we did not combine these data with other studies, and we did not consider this to introduce risk of bias to the review. Overall, we judged Bench 2015 as having a high risk of other sources of bias due to the ad hoc information given to the control group.

We judged one study to be at a high risk of bias because the control group had opportunities to meet with a palliative care team, and it is feasible that some participant carers in that group received equivalent information to the intervention group (Carson 2016). One study had differences in gender and years of education between carer participants (Torke 2016); it was not feasible to judge whether this may have influenced the results, and we assessed this study as at unclear risk of bias. One study had limited detail in the study report relating to intervention and control groups (Demircelik 2016); we judged this study as at unclear risk of bias. We identified no other sources of bias in the remaining studies (Azoulay 2002; Curtis 2016; Fleischer 2014; Hwang 1998).

Effects of interventions

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Information or education intervention versus no information or education intervention.

| Information or education intervention versus no information or education intervention | ||||

|

Patient or population: adult ICU patients and their carers Settings: ICUs in Turkey, Germany, Taiwan, and the USA Intervention: information or education intervention Comparison: no information or education intervention | ||||

| Outcomes | Effects of information or education interventions for adult ICU patients and their carers | No. of analysed participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

|

Severity of anxiety in patients HADS‐A (1 week after hospital discharge); scale from 0 to 20 CINT (admission to regular ward); scale from 0 to 100 BSRS (in ICU, time point not specified); scale from 0 to 20 Lower scores in all scales indicate less anxiety. |

In 1 study, mean anxiety scores in the intervention group were 3.20 lower (3.38 to 3.02 lower). 2 studies reported mean anxiety scores with little or no difference between groups (0.40 lower in the intervention group, 4.75 lower to 3.95 higher; and 1.00 lower in the intervention group, 2.94 lower to 0.94 higher). |

332 patient participants (3 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowa |

We did not pool data: statistical heterogeneity was high (I² = 99%); we noted possible clinical differences in illness severity of participants (e.g. whether patient participants were intubated), and methodological differences in types of information provision (e.g. whether information was tailored, and what type, and how often, it was presented). |

|

Severity of depression in patients HADS‐D (1 week after hospital discharge); scale from 0 to 20 BSRS (in ICU, time point not specified); scale from 0 to 20 Lower scores in both scales indicate less depression. |

In 2 studies, mean depression scores in the intervention group were 2.90 lower (4.00 to 1.80 lower); and 1.27 lower (1.47 to 1.07 lower). | 160 patient participants (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowb |

We did not pool data: statistical heterogeneity was high (I² = 99%); we noted possible clinical differences in illness severity of participants (e.g. whether patient participants were intubated), and methodological differences in types of information provision (e.g. what type, and how often the information was presented). |

| Knowledge acquisition (patients and carers) | Not measured | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Severity of PTSD in patients treated in ICUs | Not measured | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Patient or carer satisfaction with information provided (e.g. self reported) | Not measured | ‐ | ‐ | |

|

Health‐related quality of life (HRQoL) SF‐12 MCS (3 months after ICU discharge); scale from 0 to 100 Lower scores indicate reduced HRQoL. |

In 1 study, mean HRQoL score in the intervention group was 1.30 lower (4.99 lower to 2.39 higher). | 143 patient participants (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowc |

|

| Adverse effects | Not measured | ‐ | ‐ | |

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate certainty: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low certainty: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low certainty: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||

| BSRS: Brief Symptom Rating Scale; HADS‐A: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale ‐ anxiety subscale; HADS‐D: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale ‐ depression subscale; ICU: intensive care unit; MCS: mental health component summary; PTSD: post‐traumatic stress disorder; SF‐12: 12‐item Short Form Health Survey | ||||

aTwo studies reported insufficient information on randomisation methods and allocation concealment; we could not judge risk of selective reporting bias due to insufficient reporting; and we were unclear if lack of blinding would have influenced outcome assessment; we downgraded by one level for study limitations. Few studies with a small sample size reported outcome data, and we could not combine data; we downgraded one level for imprecision. We noted statistical heterogeneity in outcome data between studies; we downgraded one level for inconsistency. bBoth studies reported insufficient information on randomisation methods and allocation concealment; we could not judge risk of selective reporting bias due to insufficient reporting; and we were unclear if lack of blinding would have influenced outcome assessment; we downgraded by one level for study limitations. Few studies with a small sample size reported outcome data; we downgraded one level for imprecision. We noted statistical heterogeneity in outcome data between studies; we downgraded one level for inconsistency. cWe were unclear if lack of blinding would have influenced outcome assessment, and we noted high attrition; we downgraded by one level for study limitations. Data were from a single study with a small sample size, and wide confidence interval; we downgraded two levels for imprecision.

Summary of findings 2. Information or education intervention as part of a complex intervention versus complex intervention without information or education.

| Information or education intervention as part of a complex intervention versus complex intervention without information or education | ||||

|

Patient or population: adult ICU patients and their carers Settings: ICUs in France, the UK, and the USA Intervention: information or education intervention as part of a complex intervention Comparison: complex intervention without information or education intervention | ||||

| Outcomes | Effects of information or education interventions for adult ICU patients and their carers | No. of analysed participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

|

Severity of anxiety in patients HADS‐A (at hospital discharge or at 28 days, whichever time point was soonest); scale from 0 to 20 Lower scores indicate less anxiety. |

In 1 study, mean anxiety score (using HADS‐A) in participants given a tailored information pack was 0.09 higher (‐3.29 lower to 3.47 higher), and in participants given a standardised general ICU information leaflet was 0.25 lower (4.34 lower to 3.84 higher). | 38 patient participants (1 study) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowa |

|

|

Severity of depression in patients HADS‐D (at hospital discharge or 28 days, whichever time point was soonest); scale from 0 to 20 Lower scores indicate less depression. |

In 1 study, mean depression score (using HADS‐D) in participants given a tailored information pack was 1.26 lower (4.48 lower to 1.96 higher), and in participants given a standardised general information leaflet was 1.47 lower (6.37 lower to 3.43 higher). | 38 patient participants (1 study) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowa |

|

| Knowledge acquisition (patients and carers) | In 1 study, fewer carer participants had poor comprehension if they were given an information leaflet (RR 0.28, 95% CI 0.15 to 0.53; absolute risk difference of 29.4% fewer carer participants with poor comprehension (41.6% to 17.1% fewer)). | 175 carer participants (1 study) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowb |

|

| Severity of PTSD in patients treated in ICUs | Not measured | ‐ | ‐ | |

|

Patient or carer satisfaction with information provided CCFNI (between day 3 and day 5); scale from 14 to 56 Lower scores indicate increased satisfaction. FS‐ICU 24 (90 days after randomisation); scale from 0 to 100 Lower scores indicate less satisfaction. |

1 study noted little or no difference in level of carer participant satisfaction when they were given an information leaflet. In 1 study, mean score of family satisfaction (using FS‐ICU 24) in the intervention group was 3.20 lower (7.27 lower to 0.87 higher). |

487 carer participants (2 studies) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowc |

We did not pool data: data in one study were reported as median scores; we could not calculate a mean difference with these data. |

| Health‐related quality of life | Not measured | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Adverse effects | 1 patient participant asked to be withdrawn from the trial because she believed that completion of the HADS triggered a deterioration in her mental health. It was not reported whether this participant came from the information intervention or comparison group. | 59 patient participants (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowd |

|

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate certainty: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low certainty: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low certainty: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||

| CCFNI: Critical Care Family Needs Inventory; CI: confidence interval; FS‐ICU 24: Family Satisfaction in the Intensive Care Unit 24‐item survey; HADS‐A: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale ‐ anxiety subscale; HADS‐D: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale ‐ depression subscale; ICU: intensive care unit; PTSD: post‐traumatic stress disorder; RR: risk ratio | ||||

aWe were unclear if lack of blinding would have influenced outcome assessment, and we noted high attrition; we downgraded by one level for study limitations. Data were from a single study with a very small sample size; we downgraded two levels for imprecision. bWe were unclear if lack of blinding would have influenced outcome assessment, and we could not judge risk of selective reporting bias due to insufficient reporting; we downgraded by one level for study limitations. Data were from a single study with a small sample size; we downgraded two levels for imprecision. cWe were unclear if lack of blinding would have influenced outcome assessment, and we noted some inconsistencies in attrition; we downgraded by one level for study limitations. Data were from two studies; we noted a wide range of scores in one study, and a wide CI in the other study; we downgraded two levels for imprecision. dWe were unclear if lack of blinding would have influenced outcome assessment, and we noted high attrition; we downgraded by one level for study limitations. Evidence was from a single study with a very small sample size, and study authors did not report whether the single event related to the intervention group or the control group; we downgraded two levels for imprecision.

Comparison 1: information or education intervention versus no information or education intervention

Primary outcomes

Severity of anxiety in patients

Three studies measured anxiety and analysed data for 332 patient participants (Demircelik 2016; Fleischer 2014; Hwang 1998). Demircelik 2016 used the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale ‐ anxiety subscale (HADS‐A) at one week after hospital discharge. Fleischer 2014 used three scoring systems for anxiety: a questionnaire for surgical ICU patients (called CINT) after admission to the regular ward; the State‐Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI); and the visual analogue scale for anxiety (VAS‐A). We used the CINT questionnaire in this review because this was the primary outcome identified by the study authors. Hwang 1998 used the Brief Symptom Rating Scale (BSRS) postoperatively in the cardiosurgical unit. Lower scores in all scales indicate less anxiety. We found substantial statistical heterogeneity between studies (I² = 99%); we noted possible clinical differences between studies in illness severity of participants (e.g. whether patient participants were intubated) and methodological differences in types of information provision (e.g. whether information was tailored; and what type, and how often, it was presented). We therefore did not pool data for anxiety. See Analysis 1.1 for unpooled data.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Information or education intervention versus no information or education intervention, Outcome 1 Anxiety in patient participants.

We calculated mean differences (MDs) for each study using the Review Manager 5 calculator (Review Manager 2014). Demircelik 2016 found that patient participants experienced reduced anxiety if they received multimedia information compared to no information (MD ‐3.20, 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐3.38 to ‐3.02); this was a score of 3.20 points lower (indicating less anxiety) in the intervention group (3.38 to 3.02 lower). However, Fleischer 2014 found little or no difference in anxiety when patient participants received standardised and structured information compared to a standardised non‐specific conversation (MD ‐0.40, 95% CI ‐4.75 to 3.95; a score of 0.40 points lower in the intervention group, 4.75 lower to 3.95 higher), and Hwang 1998 found little or no difference in anxiety when patient participants listened to an audio message about the ICU compared to no audio message (MD ‐1.00, 95% CI ‐2.94 to 0.94; 1.00 points lower in the intervention group, 2.94 lower to 0.94 higher).

Overall, it is uncertain whether an information or education intervention compared to no information or education intervention reduces anxiety in patients due to very low‐certainty evidence. Using the GRADE approach, we downgraded by one level for study limitations (because some studies had unclear risk of selection bias; we were unable to assess risk of selective reporting bias in studies; and it was unclear if lack of blinding would have influenced outcome assessment); one level for imprecision (because the sample size was small); and one level for inconsistency (due to unexplained statistical heterogeneity). See Table 1.

Severity of depression in patients

Two studies measured depression and analysed data for 160 participants (Demircelik 2016; Hwang 1998). Tools used to measure depression were: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale ‐ depression subscale (HADS‐D) at one week after hospital discharge (Demircelik 2016), and the BSRS postoperatively in the cardiosurgical unit (Hwang 1998). Lower scores on both scales indicate less depression. We found substantial statistical heterogeneity between studies (I² = 99%); we noted possible clinical differences between studies in illness severity of participants (e.g. whether patient participants were intubated) and methodological differences in types of information provision (e.g. what type, and how often the information was presented). We therefore did not pool data for depression. See Analysis 1.2 for unpooled data.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Information or education intervention versus no information or education intervention, Outcome 2 Depression in patient participants.

We calculated MDs for each study using the Review Manager 5 calculator (Review Manager 2014). Demircelik 2016 found that patient participants who received multimedia education training experienced a slight reduction in depression compared to those who received no information (MD ‐2.90, 95% CI ‐4.00 to ‐1.80); this was a score of 2.90 points lower (indicating less depression) in the intervention group (4.00 to 1.80 lower). Hwang 1998 also found that patient participants who received an information intervention (an audio message) experienced a reduction in depression compared to those who received no information (MD ‐1.27, 95% CI ‐1.47 to ‐1.07); this was a score of 1.27 points lower (indicating less depression) in the intervention group (1.47 to 1.07 lower).

However, it is uncertain whether information or education intervention compared to no information or education intervention reduces depression in patients due to very low‐certainty evidence. Using the GRADE approach, we downgraded by one level for study limitations (because some studies had unclear risk of selection bias; we were unable to assess risk of selective reporting bias in studies; and it was unclear if lack of blinding would have influenced outcome assessment); one level for imprecision (because the sample size was small); and one level for inconsistency (due to unexplained statistical heterogeneity). See Table 1.

Knowledge acquisition (patients and carers)

No study reported this outcome.

Secondary outcomes

Severity of PTSD in patients treated in ICUs

No study reported this outcome.

Severity of depression in carers

One study reported depression in 26 carer participants six to eight weeks after ICU discharge using the Patient Health Questionnaire‐9 (PHQ‐9), with lower scores indicating less depression (Torke 2016). Calculating MD using the Review Manager 5 calculator (Review Manager 2014), we noted that using a Family Navigator to provide information to carer participants makes little or no difference to depression of carer participants (MD 2.90, 95% CI ‐1.84 to 7.64); this is a score of 2.90 higher (indicating more depression) in the intervention group (1.84 lower to 7.64 higher). See Table 3 for data reported by study authors.

1. Comparison 1: information or education intervention versus no information or education intervention.

| Outcome: severity of depression in carers | ||||

| Study | Measurement tool |

Data as mean (SD) Intervention |

Data as mean (SD) Control |

P value* |

| Torke 2016 | PHQ‐9, for depression (at 6 to 8 weeks postdischarge) |

7.1 (± 7.4); N = 13 | 4.2 (± 4.6); N = 13 | 0.34 |

| Outcome: severity of anxiety in carers | ||||

| Study | Measurement tool |

Data as mean (SD) Intervention |

Data as mean (SD) Control |

P value* |

| Torke 2016 | GAD‐7, for anxiety (at 6 to 8 weeks postdischarge) |

5.7 (± 5.7); N = 13 | 3.9 (± 5.0); N = 13 | 0.32 |

| Outcome: health‐related quality of life | ||||

| Study | Measurement tool |

Data as mean (SD) Intervention |

Data as mean (SD) Control |

P value* |

| Fleischer 2014 | SF‐12 MCS (at 3 months postdischarge) |

46.9 (± 11.3); N = 71 | 48.2 (± 11.2); N = 72 | ‐ |

| Outcome: length of ICU stay | ||||

| Study | Measurement tool |

Data as mean (SD) Intervention |

Data as mean (SD) Control |

P value* |

| Fleischer 2014 | length of stay, days | 4.3 (± 4.5); N = 104 | 4.9 (± 5.5); N = 107 | ‐ |

*P value as reported by study authors GAD‐7: Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7‐item scale ICU: intensive care unit MCS: mental health component summary (of SF‐12) N: number of analysed participants PHQ‐9: Patient Health Questionnaire‐9 SD: standard deviation SF‐12: 12‐item Short Form Health Survey

We did not use GRADEpro GDT to assess the certainty of this evidence (GRADEpro GDT), but noted that these data were from one pilot study with methodological limitations and a very small sample size, therefore our confidence in the effect was very low.

Severity of anxiety in carers

One study reported anxiety in 26 carer participants six to eight weeks after ICU discharge using the Generalized Anxiety Disorder seven‐item scale (GAD‐7), with lower scores indicating less anxiety (Torke 2016). We calculated MD using the Review Manager 5 calculator (Review Manager 2014), and noted that using a Family Navigator to provide information to carer participants makes little or no difference to the anxiety of carer participants (MD 1.80, 95% CI ‐2.32 to 5.92); this is 1.80 higher (indicating more anxiety) in the intervention group (2.32 lower to 5.92 higher). See Table 3 for data reported by study authors.

We did not use GRADEpro GDT to assess the certainty of this evidence (GRADEpro GDT), but noted that these data were from one pilot study with methodological limitations and a very small sample size, therefore our confidence in the effect was very low.

Patient or carer satisfaction with information provided

No study reported this outcome.

Health‐related quality of life

One study reported HRQoL in 143 patient participants three months after discharge (Fleischer 2014). This study used two assessment tools to measure HRQoL: the 12‐item Short Form Health Survey (SF‐12) and the Schedule for Evaluation of Individual Quality of Life (SEIQoL). We used data from the mental component score of the SF‐12 (SF‐12 MCS); this scoring system is a shortened version of the SF‐36, which is the most commonly used tool to assess HRQoL in critically ill people (Hofhuis 2009), with lower scores indicating worse health. Study authors reported no clinically relevant differences in HRQoL at three months between patient participants who received standardised and structured verbal information and those who received a standardised non‐specific conversation; we calculated MD using the Review Manager 5 calculator, which also showed little or no difference between groups (MD ‐1.30, 95% CI ‐4.99 to 2.39); this score is 1.30 lower (indicating worse HRQoL) in the intervention group (4.99 lower to 2.39 higher). See Table 3 for data reported by study authors.

It is uncertain whether using information or education intervention compared to no information or education intervention improves HRQoL (in relation to mental function) due to very low‐certainty evidence. Using the GRADE approach, we downgraded by one level for study limitations (because we were unclear if lack of blinding would have influenced outcome assessment, and we noted high attrition in the study) and two levels for imprecision (because evidence was from a single study; the sample size was small; and the CI was wide) (GRADEpro GDT). See Table 1.

Length of stay in the ICU

One study reported length of ICU stay for 143 patient participants (Fleischer 2014). We calculated MD using the Review Manager 5 calculator (Review Manager 2014), and found little or no difference in length of ICU stay between those who received standardised and structured verbal information and those who received a standardised non‐specific conversation (MD ‐0.60 days, 95% CI ‐1.95 to 0.75); this is 0.60 days lower in the intervention group (1.95 lower to 0.75 higher). See Table 3 for data reported by study authors.

We did not use GRADEpro GDT to assess the certainty of the evidence (GRADEpro GDT), but noted that evidence for this outcome was from one study with methodological limitations and few participants, therefore our confidence in the effect was very low .

Adverse effects

No study reported this outcome.

Subgroup analyses

We did not perform meta‐analysis on any data and were not able to conduct formal statistical subgroup analyses on data for this comparison. We attempted to group studies and performed narrative assessment of the influence of potential effect modifiers for those outcomes where at least two studies with differences in potential effect modifiers contributed data. There were relatively few studies contributing data to this comparison, and narrative grouping according to potential effect modifiers did not reveal any clear patterns in the findings based on differential influences of these factors. A narrative synthesis is presented in Appendix 7.

Sensitivity analyses

We did not perform meta‐analysis on any data and were not able to conduct sensitivity analyses on data for this comparison.

Comparison 2: information or education intervention as part of a complex intervention (e.g. information or education intervention plus support) versus complex intervention without information or education (e.g. support alone)

Primary outcomes

Severity of anxiety in patients

One study assessed anxiety at hospital discharge or at 28 days after ICU discharge using HADS‐A in 38 patient participants (Bench 2015). This study was a cluster‐randomised study with three study arms. Study authors reported data as median and range scores; we contacted the study authors, who provided raw participant data, which we used to calculate mean and SDs. See Table 4 for median (range) scores in the published report, and mean (SD) scores as calculated by the review authors using participant data from the study authors (using the Review Manager 5 calculator) (Review Manager 2014). We found little or no difference in anxiety experienced by patient participants at hospital discharge or at 28 days after ICU discharge (study authors reported data at whichever time point was soonest) regardless of whether participants were given a tailored UCCDIP, a standard ICUsteps information booklet, or ad hoc information. For participants given the tailored UCCDIP versus those given ad hoc verbal information: MD 0.09, 95% CI ‐3.29 to 3.47; this is a score of 0.09 higher (indicating more anxiety) in the UCCDIP group (3.29 lower to 3.47 higher). For participants given standard ICUsteps information booklet versus those given ad hoc verbal information: MD ‐0.25, 95% CI ‐4.34 to 3.84; this is 0.25 lower (indicating less anxiety) in the ICUsteps group (4.34 lower to 3.84 higher).

2. Comparison 2: information or education intervention as part of a complex intervention versus complex intervention without information or education.

| Outcome: severity of anxiety in patients | ||||

| Study | Measurement tool |

Data Intervention |

Data Control |

P value* |

| Bench 2015 | HADS‐A (at hospital discharge or at 28 days post‐ICU discharge, whichever time point was soonest) |

UCCDIP Mean (SD)a: 6.47 (± 5.04); N = 17 Median (range): 7.0 (18); N = 17 ICUsteps Mean (SD)a: 6.13 (± 4.79); N = 8 Median (range): 6.0 (13); N = 8 |

Mean (SD)a: 6.38 (± 4.39); N = 13 Median (range): 5.0 (16); N = 13 |

≥ 0.05 |

| Outcome: severity of depression in patients | ||||

| Study | Measurement tool |

Data Intervention |

Data Control |

P value* |

| Bench 2015 | HADS‐D (at hospital discharge or at 28 days post‐ICU discharge, whichever time point was soonest) |