Abstract

Background

Antihypertensive drugs are often used in the belief that lowering blood pressure will prevent progression to more severe disease, and thereby improve pregnancy outcome. This Cochrane Review is an updated review, first published in 2001 and subsequently updated in 2007 and 2014.

Objectives

To assess the effects of antihypertensive drug treatments for women with mild to moderate hypertension during pregnancy.

Search methods

We searched Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth’s Trials Register, ClinicalTrials.gov, the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (13 September 2017), and reference lists of retrieved studies.

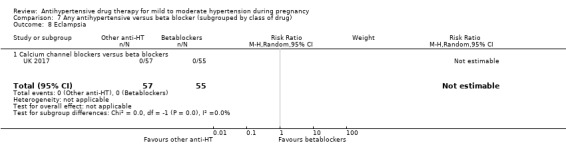

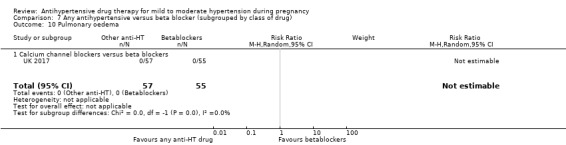

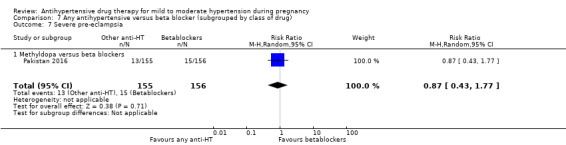

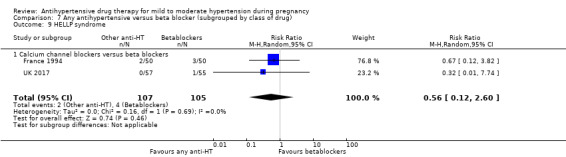

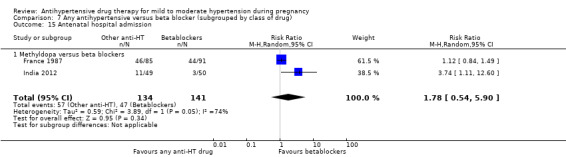

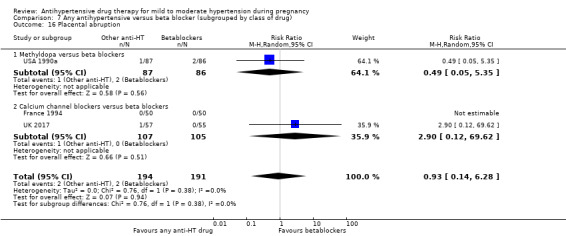

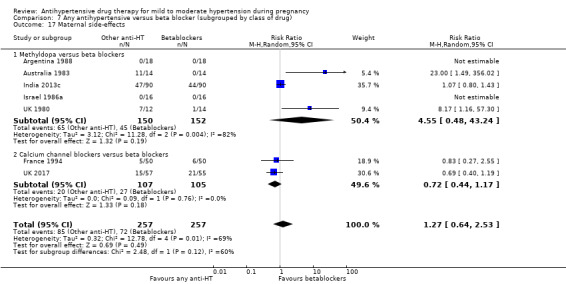

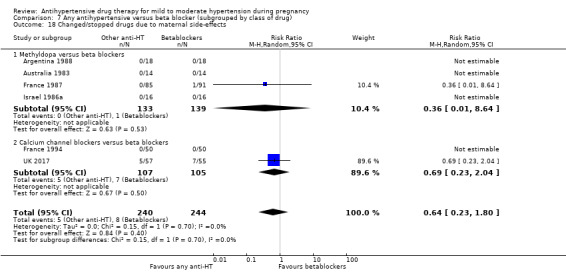

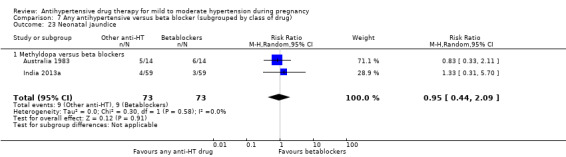

Selection criteria

All randomised trials evaluating any antihypertensive drug treatment for mild to moderate hypertension during pregnancy, defined as systolic blood pressure 140 to 169 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure 90 to 109 mmHg. Comparisons were of one or more antihypertensive drug(s) with placebo, with no antihypertensive drug, or with another antihypertensive drug, and where treatment was planned to continue for at least seven days.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed trials for inclusion and risk of bias, extracted data and checked them for accuracy.

Main results

For this update, we included 63 trials (data from 58 trials, 5909 women), with moderate to high risk of bias overall.

We carried out GRADE assessments for the main 'antihypertensive drug versus placebo/no antihypertensive drug' comparison only. Evidence was graded from very low to moderate certainty, with downgrading mainly due to design limitations and imprecision.For many outcomes, trials contributing data evaluated different hypertensive drugs; while we did not downgrade for this indirectness, results should be interpreted with caution.

Antihypertensive drug versus placebo/no antihypertensive drug (31 trials, 3485 women)

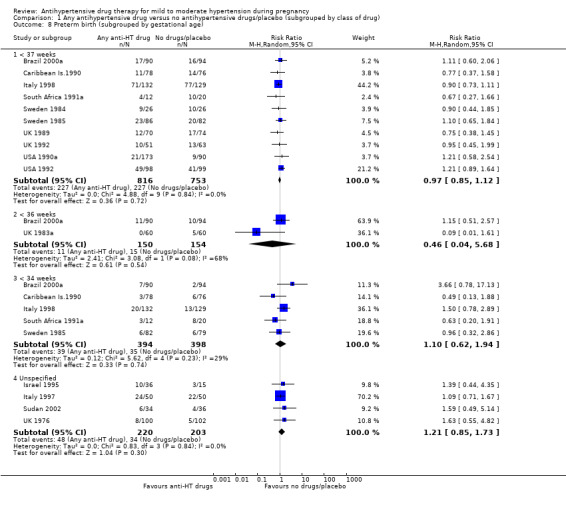

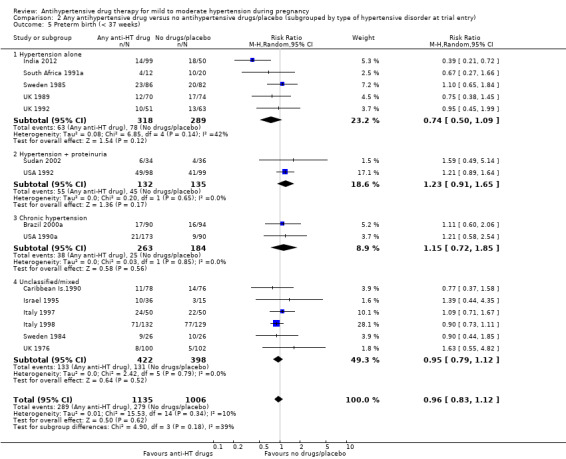

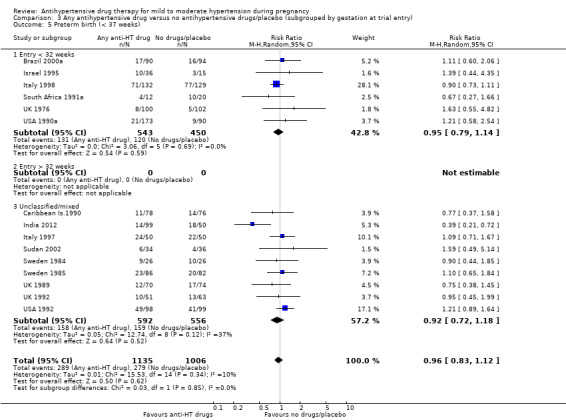

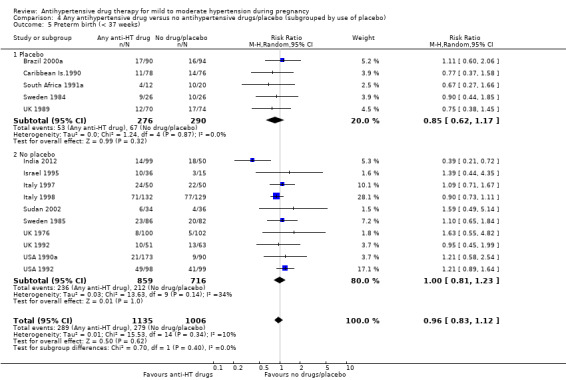

Primary outcomes: moderate‐certainty evidence suggests that use of antihypertensive drug(s) probably halves the risk of developing severe hypertension (risk ratio (RR) 0.49; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.40 to 0.60; 20 trials, 2558 women), but may have little or no effect on the risk of proteinuria/pre‐eclampsia (average risk ratio (aRR) 0.92; 95% CI 0.75 to 1.14; 23 trials, 2851 women; low‐certainty evidence). Moderate‐certainty evidence also shows that antihypertensive drug(s) probably have little or no effect in the risk of total reported fetal or neonatal death (including miscarriage) (aRR 0.72; 95% CI 0.50 to 1.04; 29 trials, 3365 women), small‐for‐gestational‐age babies (aRR 0.96; 95% CI 0.78 to 1.18; 21 trials, 2686 babies) or preterm birth less than 37 weeks (aRR 0.96; 95% CI 0.83 to 1.12; 15 trials, 2141 women).

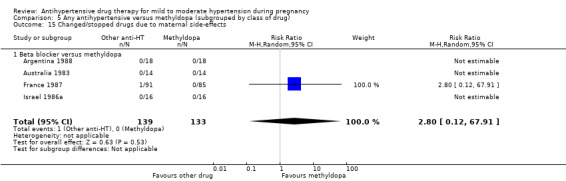

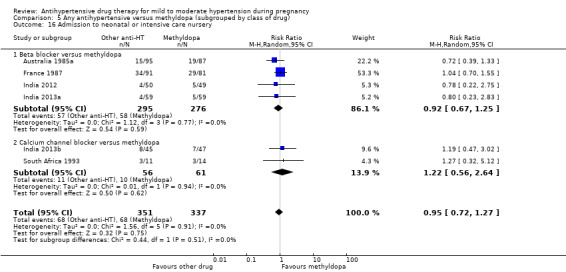

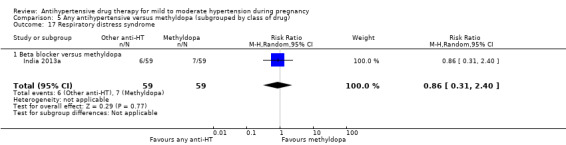

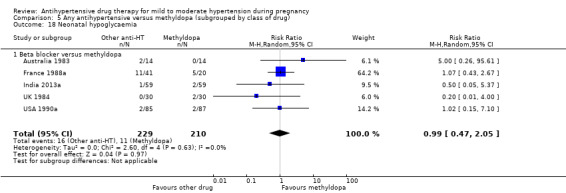

Secondary outcomes: we are uncertain of the effect of antihypertensive drug(s) on the risk of maternal death, severe pre‐eclampsia, or eclampsia, orimpaired long‐term growth and development of the baby in infancy and childhood, because the certainty of this evidence is very low. There may be little or no effect on the risk of changed/stopped drugs due to maternal side‐effects, or admission to neonatal or intensive care nursery (low‐certainty evidence). There is probably little or no difference in the risk of elective delivery (moderate‐certainty evidence).

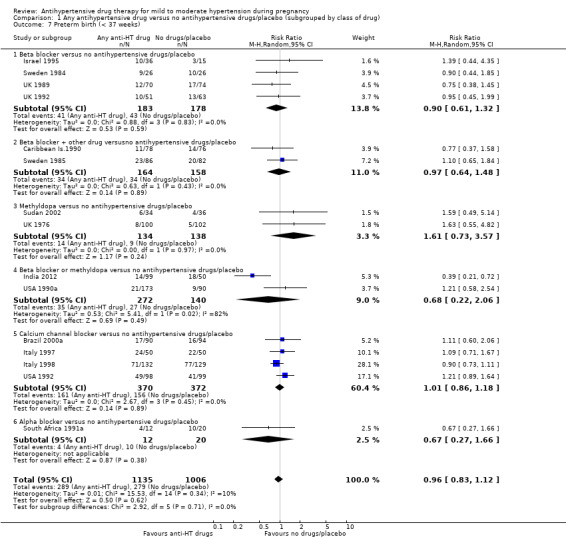

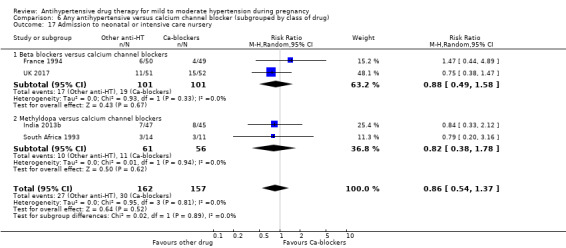

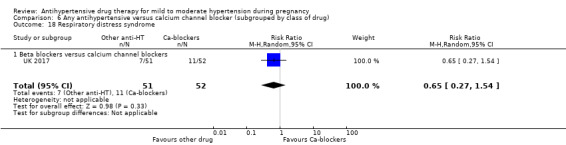

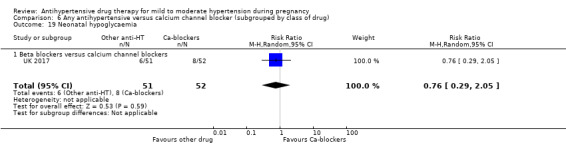

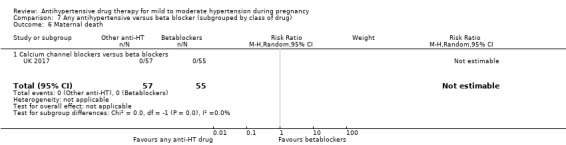

Antihypertensive drug versus another antihypertensive drug (29 trials, 2774 women)

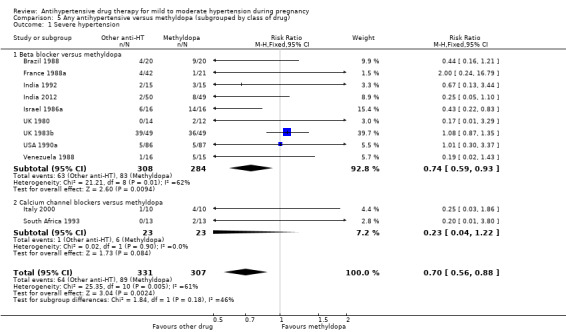

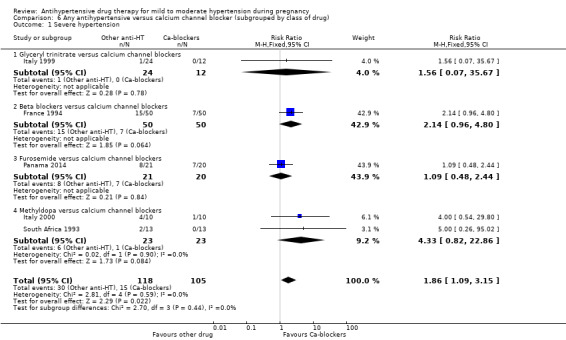

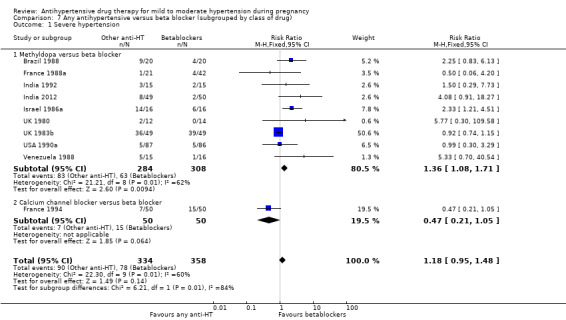

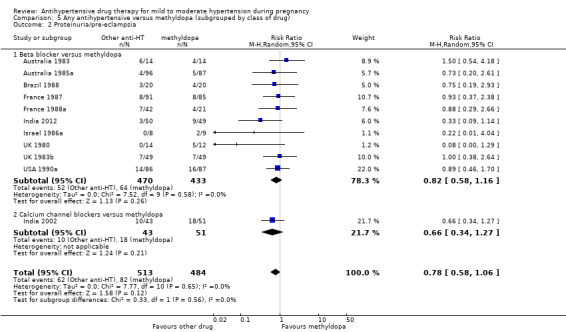

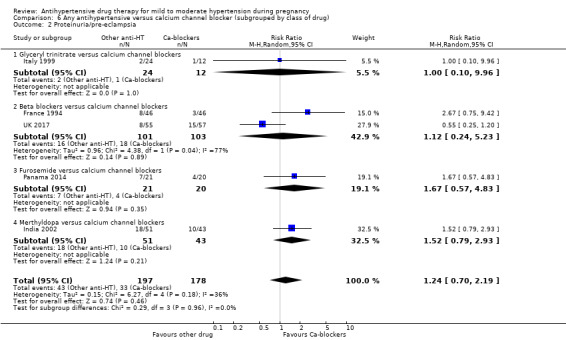

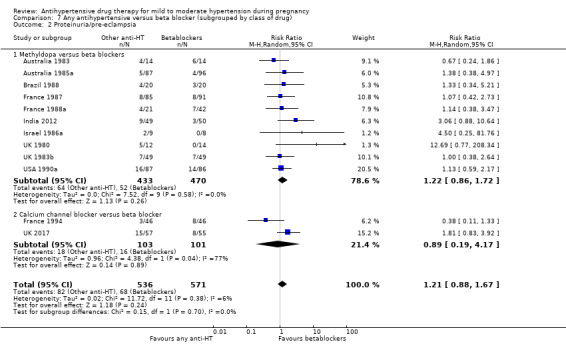

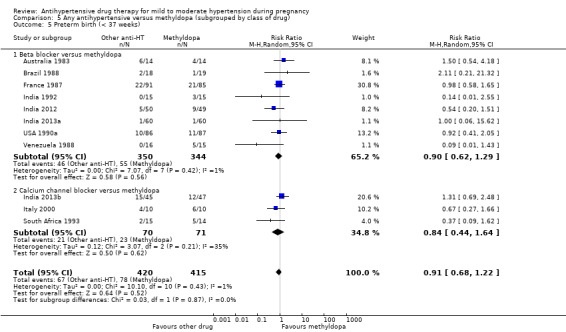

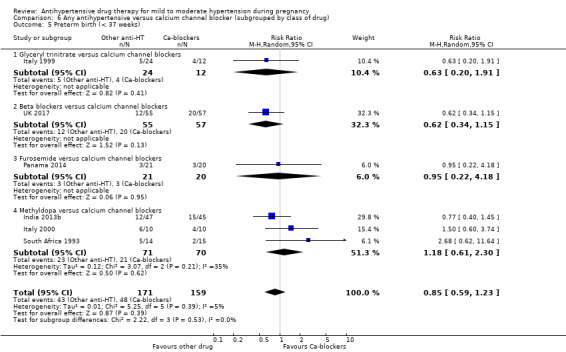

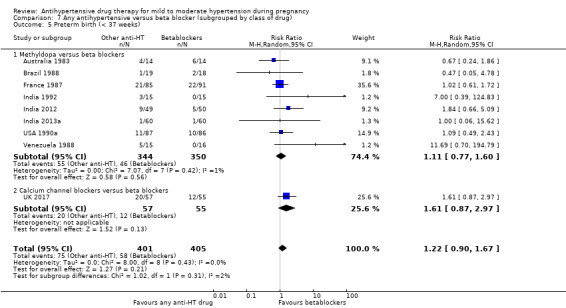

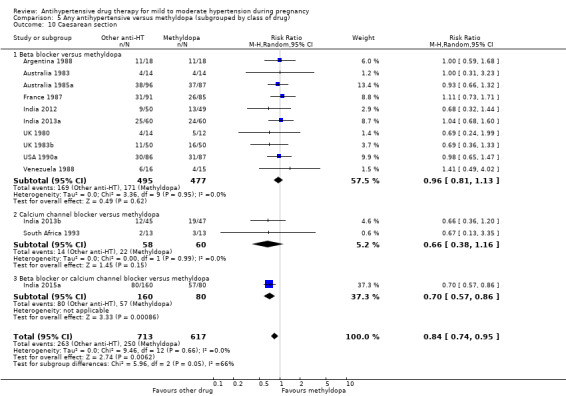

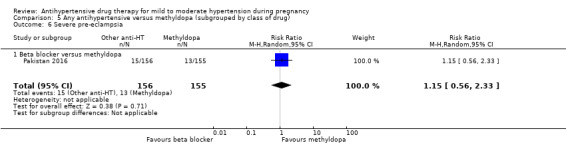

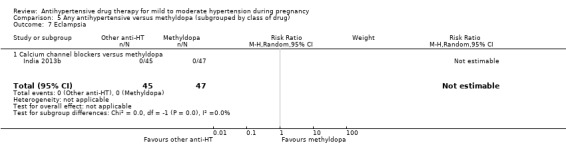

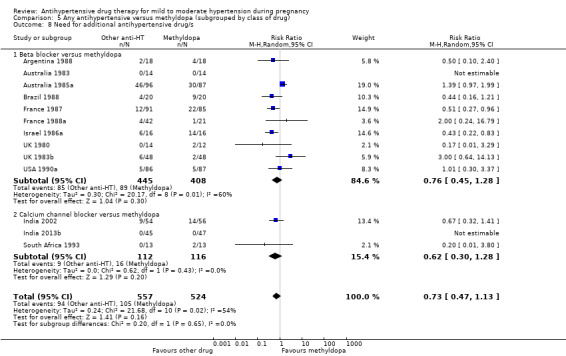

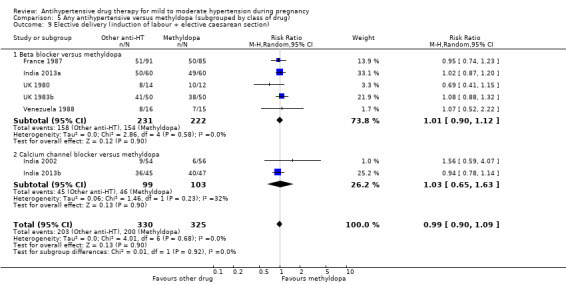

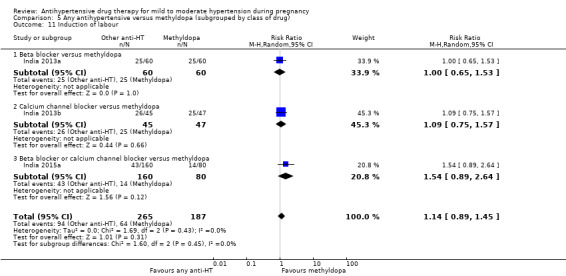

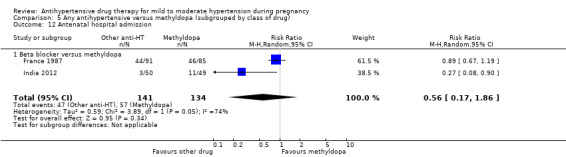

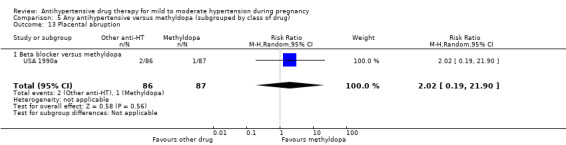

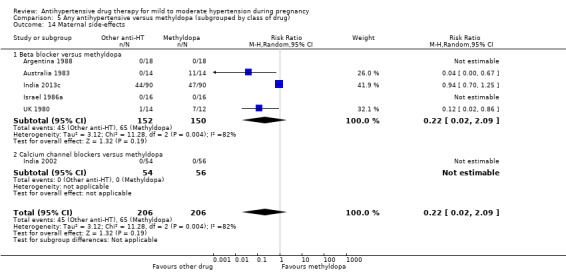

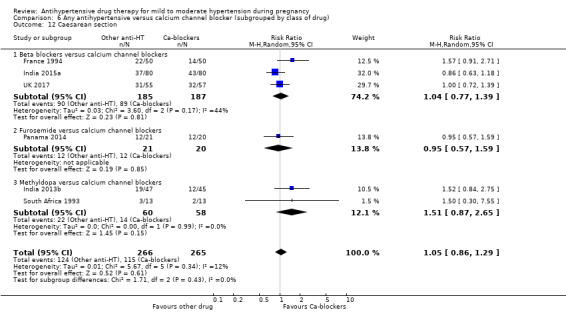

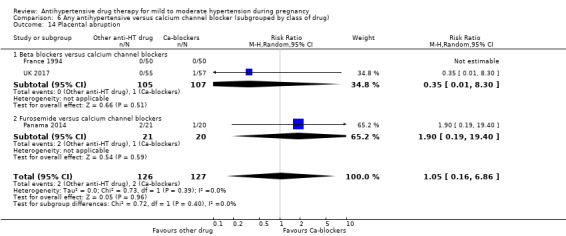

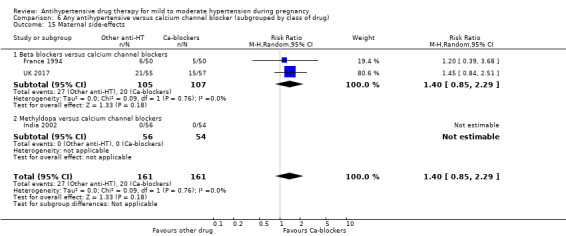

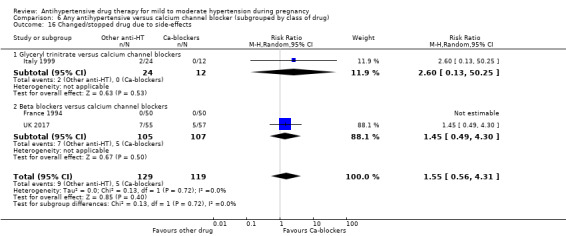

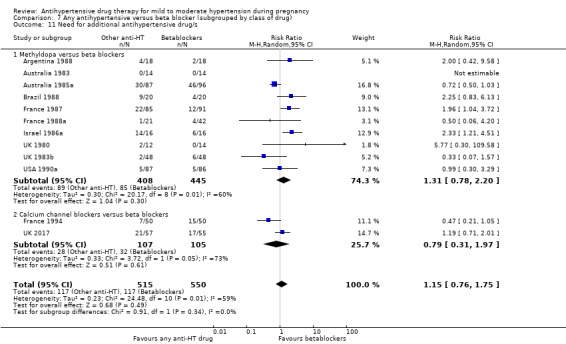

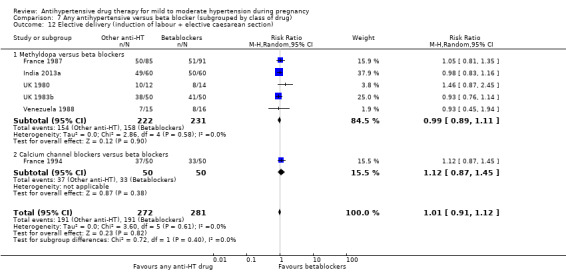

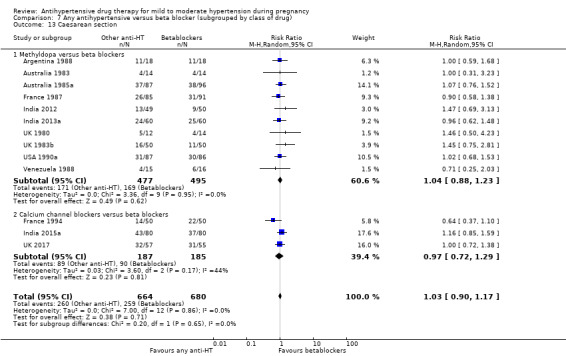

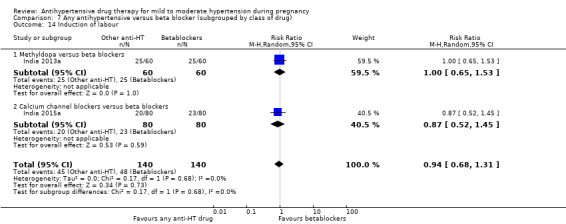

Primary outcomes: beta blockers and calcium channel blockers together in the meta‐analysis appear to be more effective than methyldopa in avoiding an episode of severe hypertension (RR 0.70; 95% CI 0.56 to 0.88; 11 trials, 638 women). There was also an increase in this risk when other antihypertensive drugs were compared with calcium channel blockers (RR 1.86; 95% CI 1.09 to 3.15; 5 trials, 223 women), but no evidence of a difference when methyldopa and calcium channel blockers together were compared with beta blockers (RR1.18, 95% CI 0.95 to 1.48; 10 trials, 692 women). No evidence of a difference in the risk of proteinuria/pre‐eclampsia was found when alternative drugs were compared with methyldopa (aRR 0.78; 95% CI 0.58 to 1.06; 11 trials, 997 women), with calcium channel blockers (aRR: 1.24, 95% CI 0.70 to 2.19; 5 trials, 375 women), or with beta blockers (aRR 1.21, 95% CI 0.88 to 1.67; 12 trials, 1107 women).

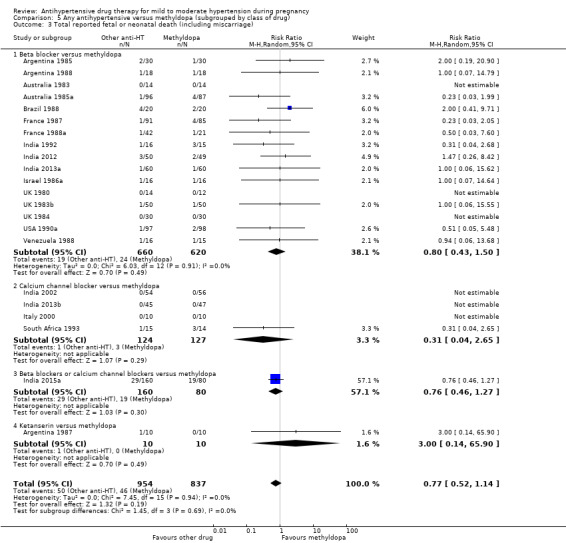

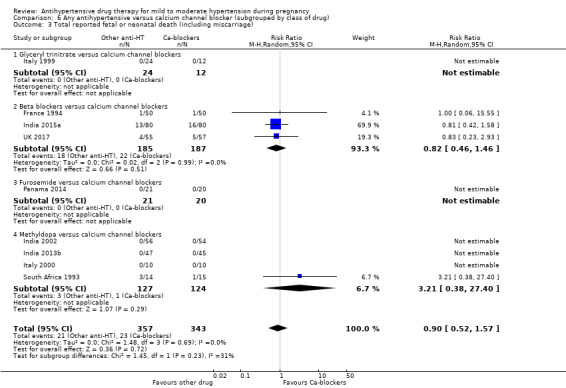

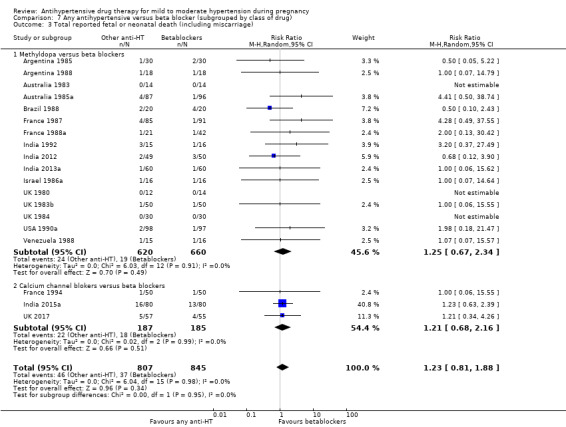

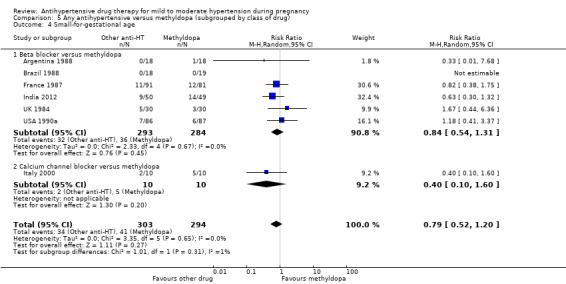

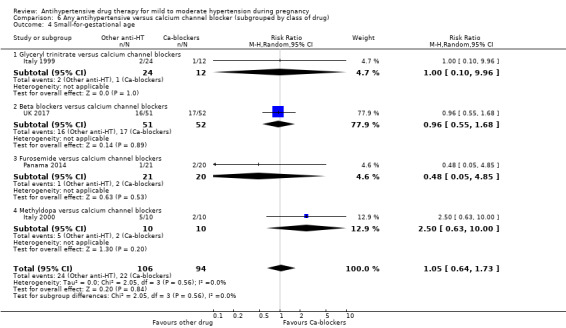

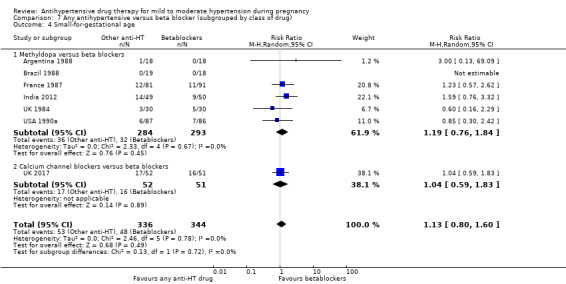

For the babies, we found no evidence of a difference in the risk oftotal reported fetal or neonatal death (including miscarriage) when comparing other antihypertensive drugs with methyldopa (aRR 0.77, 95% CI 0.52 to 1.14; 22 trials, 1791 babies), with calcium channel blockers (aRR 0.90, 95% CI 0.52 to 1.57; nine trials, 700 babies), or with beta blockers (aRR: 1.23, 95% CI 0.81 to 1.88; 19 trials, 1652 babies); nor in the risk for small‐for‐gestational age in the comparison with methyldopa (aRR 0.79, 95% CI 0.52 to 1.20; seven trials, 597 babies), with calcium channel blockers (aRR 1.05, 95% CI 0.64 to 1.73; four trials, 200 babies), or with beta blockers (average RR 1.13, 95% CI 0.80 to 1.60; 7 trials, 680 babies). No evidence of an overall difference among groups in the risk of preterm birth (less than 37 weeks) was found in the comparison with methyldopa (aRR: 0.91; 95% CI 0.68 to 1.22; 11 trials, 835 women), with calcium channel blockers (aRR 0.85, 95% CI 0.59 to 1.23; six trials, 330 women), or with beta blockers (aRR 1.22, 95% CI 0.90 to 1.66; 9 trials, 806 women).

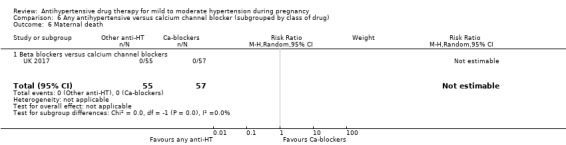

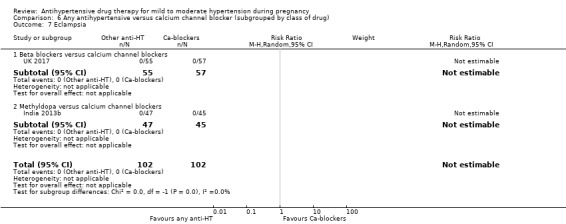

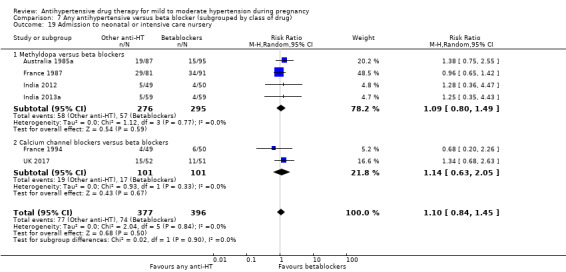

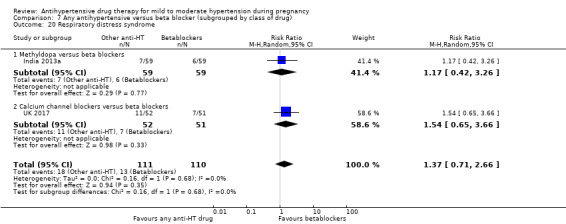

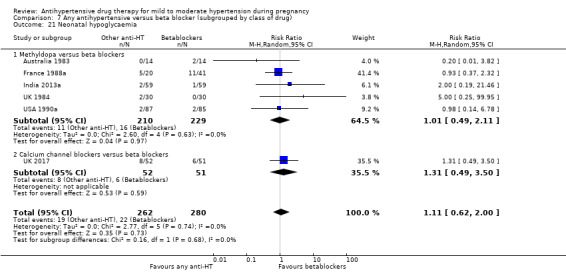

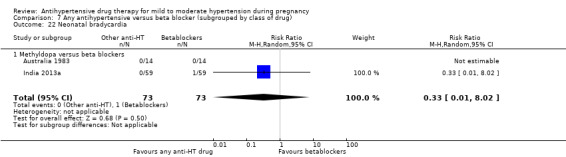

Secondary outcomes: There were no cases of maternal death andeclampsia. There is no evidence of a difference in the risk of severe pre‐eclampsia, changed/stopped drug due to maternal side‐effects, elective delivery, admission to neonatal or intensive care nursery when other antihypertensive drugs are compared with methyldopa, calcium channel blockers or beta blockers. Impaired long‐term growth and development in infancy and childhood was not reported for these comparisons.

Authors' conclusions

Antihypertensive drug therapy for mild to moderate hypertension during pregnancy reduces the risk of severe hypertension. The effect on other clinically important outcomes remains unclear. If antihypertensive drugs are used, beta blockers and calcium channel blockers appear to be more effective than the alternatives for preventing severe hypertension. High‐quality large sample‐sized randomised controlled trials are required in order to provide reliable estimates of the benefits and adverse effects of antihypertensive treatment for mild to moderate hypertension for both mother and baby, as well as costs to the health services, women and their families.

Plain language summary

Antihypertensive drug therapy for mild to moderate hypertension during pregnancy

What is the issue?

The aim of this review was to determine the benefits and adverse effects of blood pressure‐lowering drugs (antihypertensive drugs) for pregnant women with mild to moderate hypertension (high blood pressure). The other aim was to assess the benefits and adverse effects of these drugs for their babies.

Why is this important?

During pregnancy, up to one in 10 women have blood pressure readings that are above normal. For some women, their blood pressure remains slightly high (termed ‘mild to moderate high blood pressure’), with no apparent complications. Some of these women go on to develop very high blood pressure. Very high blood pressure can result in a medical emergency if it affects the woman’s organs (such as her liver, or brain in the form of a stroke). Also, it can seriously affect the growth and health of her baby.

Drugs that lower blood pressure are used to treat mild to moderate high blood pressure, in the belief that this treatment will prevent the blood pressure from continuing to rise. Over the years, information from good quality research studies has been contradictory, so we cannot be sure if this drug treatment is worthwhile.

What evidence did we find?

This Cochrane Review is an update of a review that was first published in 2001 and updated in 2007 and 2014. We searched for randomised controlled trials in September 2017, and this review now includes data from 58 trials involving more than 5900 women. A total of 31 trials with 3485 women compared a number of different blood pressure‐lowering drugs to a placebo or no treatment. There were a further 29 trials involving 2774 women which compared one blood pressure‐lowering drug with another one.

The evidence showed that treating pregnant women who had moderately raised blood pressure with blood pressure‐lowering drugs probably halved the number of the women developing severe high blood pressure (20 trials, 2558 women). However, blood pressure‐lowering drugs probably had little or no effect on the risk of the baby dying (29 trials, 3365 women), and there is insufficient data on maternal deaths to make a judgement on whether this risk is lowered (five trials, 525 women).

The use of blood pressure‐lowering drugs may have little or no effect on the number of the women developing pre‐eclampsia (23 trials, 2851 women), or the number of women who had to change drugs because of side‐effects (16 trials, 1503 women).

We found no difference in the number of babies born preterm, that is before 37 weeks (15 trials, 2141 women). There was also no difference in the number of babies born small for their gestational age (21 trials, 2686 babies).

The quality of the evidence was mostly moderate (but for pre‐eclampsia it was low). This was due to a number of small studies, and problems with the way the studies were undertaken.

The available evidence is still insufficient to demonstrate if there is any antihypertensive drug that is better than another. However, beta blockers and calcium channel blockers seem to be better than the alternative drugs for blood pressure control.

What does this mean?

More research is needed in order to confirm the true effect of antihypertensive drugs in mothers and in their babies, and to identify the drug which would be best.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Hypertension during pregnancy is common. One in 10 women will have high blood pressure at some time before delivery, and pre‐eclampsia complicates between 2% to 8% of all pregnancies worldwide (Abalos 2013). Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, particularly pre‐eclampsia and eclampsia, constitute important causes of severe acute morbidity, long‐term disability and death among mothers and babies (Abalos 2014a; Khan 2006). Pre‐eclampsia is discussed in more detail in the generic protocol of interventions for prevention of pre‐eclampsia (Meher 2005).

There is a general consensus about the classification of hypertensive disorders during pregnancy (NHBPEP 2000) considering four broad categories: (a) gestational hypertension or pregnancy‐induced hypertension, which is hypertension newly diagnosed after 20 weeks of gestation without proteinuria; (b) pre‐eclampsia, which is hypertension developed after 20 weeks of gestation with proteinuria; (c) chronic hypertension, or essential hypertension, which is pre‐existing hypertension; and (d) chronic hypertension with superimposed pre‐eclampsia. Recently, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy extended the diagnosis of pre‐eclampsia to those cases in which hypertension, in the absence of significant proteinuria, is associated with other systemic findings such as thrombocytopenia, worsening liver or renal function, pulmonary oedema or new‐onset cerebral or visual disturbances (ACOG Task Force 2013).

Moderate hypertension is defined as systolic blood pressure of 140 mmHg or more, and/or diastolic blood pressure of 90 mmHg or above on two consecutive occasions at least four hours apart. Severe hypertension is defined as systolic blood pressure of 160 mmHg or 170 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure of 110 mmHg or more two consecutive occasions up to 15 minutes apart (ACOG Task Force 2013; Canadian HDP Working Group 2014; NHBPEP 2000). Korotkoff phase V (disappearance of sounds) is now widely recommended as more reliable than phase IV (muffling) for measuring diastolic blood pressure (Canadian HDP Working Group 2014).

For this review we have accepted broad and pragmatic criteria for identifying women with mild to moderate hypertension during pregnancy. This reflects clinical practice, and is justifiable in the context of randomised trials as within each study the same criteria will have been used for women in both groups.

Description of the intervention

A wide variety of drugs have been advocated for lowering blood pressure in pregnant women with hypertension, and each group has different potential side‐effects and adverse events. In this review we evaluate individual agents within the class or family to which they belong, as each class has a similar mechanism of action.

How the intervention might work

Alpha agonists: inhibit vasoconstriction via a centrally mediated effect (Ingenito 1970). Methyldopa is the most widely used alpha agonist, and became available in 1963. Clonidine is also an alpha agonist, although it has the disadvantage that sudden withdrawal may cause a hypertensive crisis (Isaac 1980). Common side‐effects of methyldopa include dizziness, lightheadedness, drowsiness, headache, stuffy nose, and weakness, especially when starting this medication and when dosage is increased. Other side‐effects include swelling, muscle pain, dry mouth, swollen or "black" tongue, gastrointestinal symptoms and depression (depressed mood, unusual thoughts, and nightmares).

Beta blockers: beta‐adrenoceptor blocking drugs block adrenoceptors in the heart, peripheral blood vessels, airways, pancreas and liver (Frishman 1979). Labetalol has an additional arteriolar vasodilating action that lowers peripheral resistance, but is usually classified with the beta blockers. Side‐effects of beta blockers include oedema, postural hypotension, bradycardia, cold or cyanotic extremities, rashes, masking of the normal response to hypoglycaemia (sweating and tachycardia), nausea, dyspepsia, vomiting, difficulty in micturition (including acute urinary bladder retention, dizziness, headache, taste distortion, vertigo, and paraesthesia.

Calcium channel blockers: include amlodipine, isradipine, nifedipine, nicardipine, nimodipine and verapamil. These drugs inhibit influx of calcium ions to vascular smooth muscle resulting in arterial vasodilatation (Robinson 1980). Common side‐effects of calcium channel blockers include dizziness, giddiness, lightheadedness, headaches, heat sensation, weakness, flushing, palpitations, transient hypotension, heartburn, nausea, dyspnoea, nasal congestion, and muscle cramps.

Peripheral vasodilators: hydralazine is a vasodilator with a direct relaxing effect on smooth muscle in the blood vessels, predominantly in the arterioles (Stunkard 1954). The most frequently reported side‐effects are palpitations and tachycardia. Other side‐effects include flushing, hypotension, nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, gastrointestinal disturbances, headache, arthralgia, joint swelling, myalgia, and anorexia.

Serotonin receptor antagonists: ketanserin is a selective serotonin receptor antagonist with weak adrenergic receptor blocking properties (Frishman 1995). The drug is effective in lowering blood pressure in essential hypertension. It also inhibits platelet aggregation. Side‐effects of ketanserin includes dizziness, headache, drowsiness, fatigue, dry mouth, sedation, lightheadedness, lack of concentration, gastrointestinal disturbances. Rare but serious side‐effects includes ventricular tachycardia.

Nitric‐oxid donors: glyceryl trinitrate is a nitric oxide donor with vasodilator effect in perivascular smooth‐muscle cells (Seligman 1994). Side‐effects include chest pain, hypoxaemia, difficulty breathing, cyanosis, tachycardia, throbbing headache, spinning sensation, postural hypotension, dizziness, drowsiness, and weakness.

Phosphodiesterase inhibitors: sildenafil (usually associated with treatment of erectile dysfunction in men) has been attracting the attention of clinicians and researchers. This is a phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitor that increases intracellular cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) in the vascular smooth muscle, resulting in vasodilatation (Wareing 2004). The most common adverse reactions reported in clinical trials are headache, flushing, dyspepsia, abnormal vision, nasal congestion, back pain, myalgia, nausea, dizziness, and rash.

Why it is important to do this review

The role of antihypertensive therapy for pregnant women with mild to moderate hypertension is unclear. As there is no immediate need to lower mild to moderate rises in blood pressure, the rationale for treatment is that it will prevent or delay progression to more severe disease, thereby benefiting the woman or her baby, or both, and reducing consumption of health service resources. As well as reducing blood pressure, the belief has been that these drugs reduce the risk of preterm delivery and placental abruption and improve fetal growth. The aim of this review is to assess the potential benefits and hazards, to the woman and baby, of antihypertensive drugs for the treatment of mild to moderate hypertension during pregnancy. If antihypertensive agents are overall beneficial, a secondary aim will be to assess the comparative effects of alternative agents.

There are other types of interventions for women with mild to moderate hypertension during pregnancy that are not considered in this review. Interventions covered by other reviews include salt restriction (Duley 1999), antiplatelet agents (Duley 2007), abdominal decompression (Hofmeyr 2012), and bed rest, with or without hospitalisation (Meher 2005a). The role of diuretics for women with hypertension during pregnancy is covered by a separate Cochrane review (Churchill 2007), as is prevention and treatment of postpartum hypertension (Magee 2013).

For women with severe hypertension, usually defined as 170 mmHg or more systolic blood pressure or 110 mmHg or more diastolic blood pressure, there is a risk of direct arterial damage and so antihypertensive drugs are used to lower blood pressure (Gifford 1990; Redman 1993). The question of which drug is best in this situation is considered in another Cochrane review and not discussed further here (Duley 2013).

A separate review assessing the effect of alternative oral beta blocker regimens in mild to moderate hypertension during pregnancy is underway. Beta blockers are included in this review as part of all the spectrum of antihypertensive drugs.

Objectives

To determine the possible benefits, risks and side‐effects of antihypertensive drug treatments for women with mild to moderate hypertension during pregnancy (defined whenever possible as a systolic blood pressure of 140 to 169 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure of 90 to 109 mmHg, or both). Also, to compare the differential effects of alternative drug regimens.

The comparisons are of:

any antihypertensive drug with either no drug or placebo;

one antihypertensive drug compared with another. For this review, the commonly used group of drugs are regarded as controls and compared with all other group of drugs (for example, other antihypertensives versus methyldopa, other antihypertensives versus calcium channel blockers, and other antihypertensives versus beta blockers).

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All cluster‐ and‐ individually‐randomised trials evaluating any antihypertensive drug treatment for mild to moderate hypertension during pregnancy. Quasi‐randomised trials were excluded. Cross‐over trials were not eligible for inclusion.

Types of participants

The review includes women with mild to moderate hypertension during pregnancy, defined whenever possible as those with systolic blood pressure 140 to 169 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure 90 to 109 mmHg. Studies in which participants were described as having 'mild to moderate' hypertension but the range of blood pressures was not clearly specified were also included. Women were included regardless of whether they had proteinuria or not, and irrespective of previous antihypertensive treatment or whether the pregnancy was singleton or multiple.

Women who had given birth before trial entry were excluded, as were women with severe hypertension (defined whenever possible as either systolic blood pressure of 170 mmHg or more, or diastolic blood pressure 110 mmHg or more). Studies that included a substantial proportion of women who did not have mild to moderate hypertension were excluded, unless data were available on outcomes for those with mild to moderate hypertension only.

Types of interventions

Any comparison of one or more antihypertensive drug with either placebo or no antihypertensive drug was included, as were comparisons of one antihypertensive drug with another. Studies were excluded if the intention was to treat for less than seven days, as a longer period of treatment would be necessary for any substantive clinical effect. Comparisons of two drugs of the same class were also excluded, although these may be included in future updates if clinically relevant. Drugs that aimed to reduce the risk of pregnancy‐induced hypertension progressing to pre‐eclampsia but are not antihypertensive agents were also excluded.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Main outcomes were pre‐specified as follows.

Severe hypertension: defined whenever possible as either systolic blood pressure 170 mmHg or more, or diastolic blood pressure 110 mmHg or more. Trials where the definition of severe hypertension was not clear, or where the cut‐off was up to 10 mmHg lower were also included and were clearly documented.

Proteinuria/pre‐eclampsia: defined whenever possible as new proteinuria (1+ or more or 300 mg/24 hours).

Total reported fetal or neonatal death (including miscarriage): fetal deaths included miscarriage (fetal losses before viability, usually taken as 20 or 24 weeks) and stillbirths (after 24 weeks, or however defined). Perinatal deaths are stillbirths plus deaths in the first week of life. Neonatal deaths are deaths in the first 28 days.

Small‐for‐gestational age: low birthweight for gestational age, below the third, fifth or 10th percentile, using the most severe reported.

Preterm birth: all births before 37 completed weeks.

Secondary outcomes

For the woman

Maternal death.

Severe pre‐eclampsia: defined whenever possible as severe hypertension with proteinuria 2+ or more, or 2 g or more/24 hours, with or without other signs of symptoms, or as moderate hypertension with proteinuria 3+ or more. Haemolysis, elevated liver enzymes and low platelets (HELLP) syndrome is a form of severe pre‐eclampsia and was therefore included here as well as a separate measure. Trials reporting imminent eclampsia, or where the definition of severe pre‐eclampsia was not clear were also included.

Eclampsia.

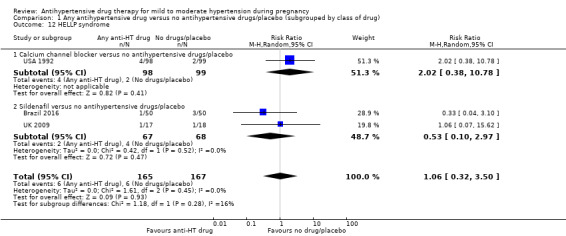

HELLP syndrome.

Severe maternal morbidity: such as liver or renal failure, disseminated intravascular coagulation and cerebrovascular accident (stroke).

Need for additional antihypertensive drug/s to control blood pressure.

Miscarriage (fetal losses before viability, usually taken as before 20 or 24 weeks).

Elective delivery: combines elective caesarean sections and elective induction of labour at term or before term.

Caesarean section.

Antenatal hospital admission and length of stay more than seven days: hospital and day care units were to be reported separately.

Placental abruption.

Side‐effects: any reported side‐effects or severe adverse events.

Changed/stopped drug due to maternal side‐effects.

For the baby

Very low, less than four, five‐minute Apgar score.

Severe prematurity, all births less than 32 or less than 34 weeks' gestation.

Admission to neonatal or intensive care nursery.

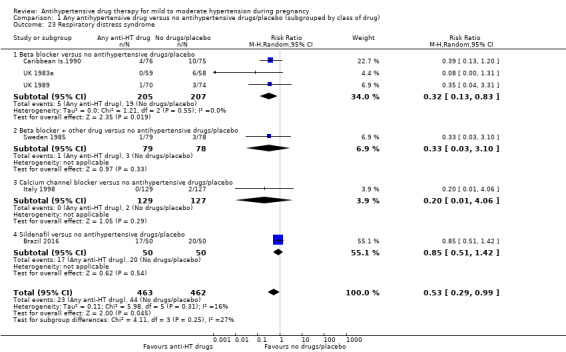

Respiratory distress syndrome.

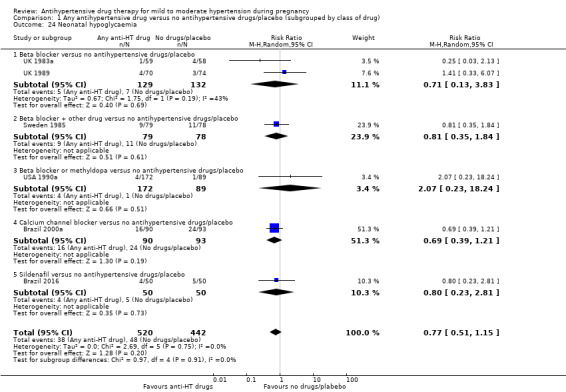

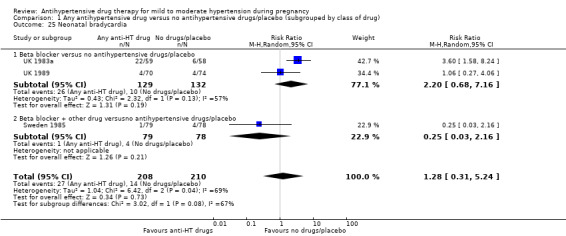

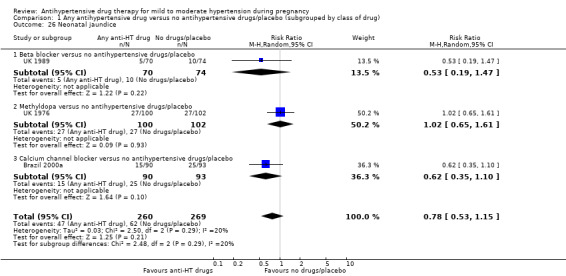

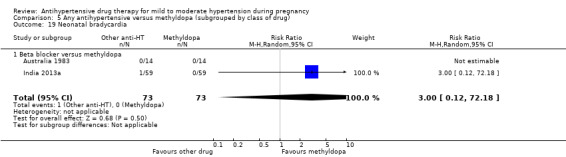

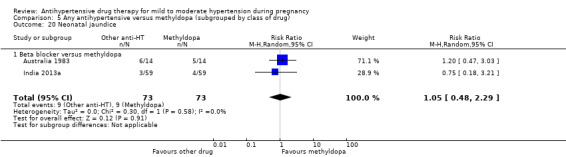

Other morbidity possibly related to maternal drug therapy, such as hypo‐ or hypertension, hypoglycaemia and bradycardia (with beta blockers).

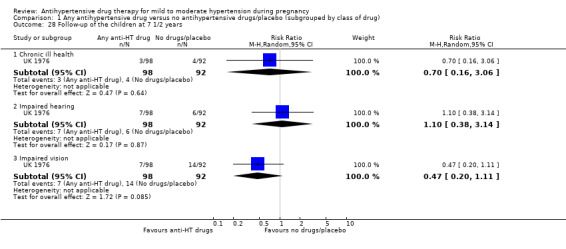

Impaired long‐term growth and development in infancy and childhood.

Search methods for identification of studies

The following search methods section of this review is based on a standard template used by Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth.

Electronic searches

For this update, we searched Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth’s Trials Register by contacting their Information Specialist (13 September 2017).

The Register is a database containing over 24,000 reports of controlled trials in the field of pregnancy and childbirth. For full search methods used to populate Pregnancy and Childbirth’s Trials Register including the detailed search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase and CINAHL; the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service, please follow this link to the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth in the Cochrane Library and select the ‘Specialized Register ’ section from the options on the left side of the screen.

Briefly, Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth’s Trials Register is maintained by their Information Specialist and contains trials identified from:

monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE (Ovid);

weekly searches of Embase (Ovid);

monthly searches of CINAHL (EBSCO);

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Search results are screened by two people and the full text of all relevant trial reports identified through the searching activities described above is reviewed. Based on the intervention described, each trial report is assigned a number that corresponds to a specific Pregnancy and Childbirth review topic (or topics), and is then added to the Register. The Information Specialist searches the Register for each review using this topic number rather than keywords. This results in a more specific search set that has been fully accounted for in the relevant review sections (Included studies; Excluded studies; Ongoing studies).

In addition, we searched ClinicalTrials.gov and the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (13 September 2017) for unpublished, planned and ongoing trial reports (See: Appendix 1)

Searching other resources

We searched reference lists of retrieved studies.

We did not apply any language or date restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

For methods used in the previous version of this review, seeAbalos 2014.

For this update, the following methods were used for assessing the 45 reports that were identified as a result of the updated search.

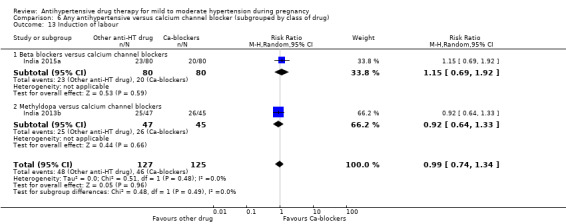

The following methods section of this review is based on a standard template used by Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth.

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently assessed for inclusion all the potential studies identified as a result of the search strategy. We resolved any disagreement through discussion or, if required, we consulted a third review author.

Data extraction and management

We designed a form to extract data. For eligible studies, two review authors extracted the data using the agreed form. We resolved discrepancies through discussion or, if required, we consulted a third review author. Data were entered into Review Manager software (RevMan 2014) and checked for accuracy.

When information regarding any of the above was unclear, we planned to contact authors of the original reports to provide further details.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). Any disagreement was resolved by discussion or by involving a third assessor.

(1) Random sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it should produce comparable groups.

We assessed the method as:

low risk of bias (any truly random process, e.g. random number table; computer random number generator);

high risk of bias (any non‐random process, e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number);

unclear risk of bias.

(2) Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to conceal allocation to interventions prior to assignment and assessed whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during recruitment, or changed after assignment.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. telephone or central randomisation; consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes);

high risk of bias (open random allocation; unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes, alternation; date of birth);

unclear risk of bias.

(3.1) Blinding of participants and personnel (checking for possible performance bias)

We described for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We considered that studies were at low risk of bias if they were blinded, or if we judged that the lack of blinding unlikely to affect results. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed the methods as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias for participants;

low, high or unclear risk of bias for personnel.

(3.2) Blinding of outcome assessment (checking for possible detection bias)

We described for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind outcome assessors from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed methods used to blind outcome assessment as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias.

(4) Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias due to the amount, nature and handling of incomplete outcome data)

We described for each included study, and for each outcome or class of outcomes, the completeness of data including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We stated whether attrition and exclusions were reported and the numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total randomised participants), reasons for attrition or exclusion where reported, and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes. Where sufficient information was reported, or could be supplied by the trial authors, we planned to re‐include missing data in the analyses which we undertook.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. no missing outcome data; missing outcome data balanced across groups);

high risk of bias (e.g. numbers or reasons for missing data imbalanced across groups; ‘as treated’ analysis done with substantial departure of intervention received from that assigned at randomisation);

unclear risk of bias.

(5) Selective reporting (checking for reporting bias)

We described for each included study how we investigated the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias and what we found.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (where it is clear that all of the study’s pre‐specified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review have been reported);

high risk of bias (where not all the study’s pre‐specified outcomes have been reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not pre‐specified; outcomes of interest are reported incompletely and so cannot be used; study fails to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported);

unclear risk of bias.

(6) Other bias (checking for bias due to problems not covered by (1) to (5) above)

We described for each included study any important concerns we had about other possible sources of bias.

(7) Overall risk of bias

We made explicit judgements about whether studies were at high risk of bias, according to the criteria given in the Handbook (Higgins 2011). With reference to (1) to (6) above, we planned to assess the likely magnitude and direction of the bias and whether we considered it is likely to impact on the findings. In future updates, we will explore the impact of the level of bias through undertaking sensitivity analyses ‐ seeSensitivity analysis.

Assessment of the quality of the evidence using the GRADE approach

For this update the quality of the evidence was assessed using the GRADE approach as outlined in the GRADE handbook in order to assess the quality of the body of evidence relating to the following outcomes for the main comparison ‐ any hypertensive drug versus no antihypertensive drugs/placebo.

Primary outcomes

Severe hypertension

Proteinuria/pre‐eclampsia

Total reported fetal or neonatal (including miscarriage)

Small‐for‐gestational age

Preterm birth

Secondary outcomes

Maternal

Maternal death

Severe pre‐eclampsia

Eclampsia

Elective delivery

Changed/stopped drug due to maternal side‐effects

Fetal/infant outcomes

Admission to neonatal or intensive care nursery

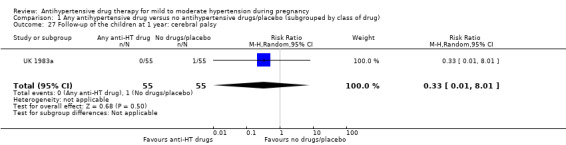

Follow‐up of the children at one year: cerebral palsy

We used the GRADEpro Guideline Development Tool to import data from Review Manager 5.3 (RevMan 2014) in order to create ’Summary of findings’ tables. A summary of the intervention effect and a measure of quality for each of the above outcomes was produced using the GRADE approach. The GRADE approach uses five considerations (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness and publication bias) to assess the quality of the body of evidence for each outcome. The evidence can be downgraded from 'high quality' by one level for serious (or by two levels for very serious) limitations, depending on assessments for risk of bias, indirectness of evidence, serious inconsistency, imprecision of effect estimates or potential publication bias.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

For dichotomous data, we presented results as summary risk ratio with 95% confidence intervals.

Continuous data

We planned to use the mean difference if outcomes were measured in the same way between trials. We would have used the standardised mean difference to combine trials that measured the same outcome, but used different methods.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐randomised trials

Although there were no cluster‐randomised trials identified to date for inclusion, we will include them in future updates in the analyses along with individually‐randomised trials. We will adjust their sample sizes using the methods described in the Handbook [Section 16.3.4] using an estimate of the intracluster correlation co‐efficient (ICC) derived from the trial (if possible), from a similar trial or from a study of a similar population. If we use ICCs from other sources, we will report this and conduct sensitivity analyses to investigate the effect of variation in the ICC. If we identify both cluster‐randomised trials and individually‐randomised trials, we plan to synthesise the relevant information. We will consider it reasonable to combine the results from both if there is little heterogeneity between the study designs and the interaction between the effect of intervention and the choice of randomisation unit is considered to be unlikely.

We will also acknowledge heterogeneity in the randomisation unit and perform a sensitivity analysis to investigate the effects of the randomisation unit.

Other unit of analysis issues

Dealing with more than two intervention groups

For multi‐arm studies, all intervention arms were mentioned and described in the Characteristics of included studies table, including the number of women randomised to each arm. Appropriate pair‐wise comparisons were selected for the meta‐analysis in order to avoid double‐counting of one of the arms. For example, when two different antihypertensive drugs were compared with placebo, the active drug groups were combined into one arm for the comparison antihypertensive drugs versus no antihypertensive drugs/placebo. These two arms, were included separately in the meta‐analysis of alternative regimens.

Dealing with missing data

For included studies, we noted levels of attrition. In future updates, if more eligible studies are included, we will explore the impact of including studies with high levels of missing data in the overall assessment of treatment effect by using sensitivity analysis.

For all outcomes, analyses were carried out, as far as possible, on an intention‐to‐treat basis, i.e. we attempted to include all participants randomised to each group in the analyses. The denominator for each outcome in each trial was the number randomised minus any participants whose outcomes were known to be missing.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed statistical heterogeneity in each meta‐analysis using the Tau², I² and Chi² statistics. We regarded heterogeneity as substantial if an I² was greater than 30% and either a Tau² was greater than zero, or there was a low P value (less than 0.10) in the Chi² test for heterogeneity. If we identified substantial heterogeneity (above 30%), we planned to explore it by pre‐specified subgroup analysis.

Assessment of reporting biases

Where there were 10 or more studies in the meta‐analysis, we investigated reporting biases (such as publication bias) using funnel plots. We assessed funnel plot asymmetry visually. If asymmetry was suggested by a visual assessment, we performed exploratory analyses to investigate it.

Data synthesis

We carried out statistical analysis using the Review Manager software (RevMan 2014). We used fixed‐effect meta‐analysis for combining data where it was reasonable to assume that studies were estimating the same underlying treatment effect: i.e. where trials were examining the same intervention, and the trials’ populations and methods were judged sufficiently similar.

Where there was clinical heterogeneity sufficient to expect that the underlying treatment effects differed between trials, or if substantial statistical heterogeneity was detected, we used random‐effects meta‐analysis to produce an overall summary, if an average treatment effect across trials was considered clinically meaningful. The random‐effects summary was treated as the average range of possible treatment effects and we discussed the clinical implications of treatment effects differing between trials. If the average treatment effect was not clinically meaningful, we did not combine trials. Where we used random‐effects analyses, the results were presented as the average treatment effect with 95% confidence intervals, and the estimates of Tau² and I².

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

For the comparison of antihypertensive drug/s with placebo or no treatment the following subgroup analyses were pre‐specified:

by class of drug (such as alpha agonists, beta blockers and calcium channel blockers);

by type of hypertensive disorder at trial entry: mild to moderate hypertension alone; mild to moderate hypertension with proteinuria; chronic hypertension; unspecified;

by gestational age at trial entry: less than about 32 weeks' gestation; about 32 weeks or more gestation; or unclassified/mixed;

by whether a placebo was used: placebo, no placebo.

The subgroup analysis by type of drug is presented for all outcomes. The remaining subgroups are presented for the pre‐specified primary outcomes only.

We assessed subgroup differences by interaction tests available within RevMan (RevMan 2014). We reported the results of subgroup analyses quoting the Chi² statistic and P value, and the interaction test I² value.

Sensitivity analysis

We did not conducted sensitivity analyses. In future updates, we plan to carry out sensitivity analyses to explore the effect of trial quality assessed by concealment of allocation, high attrition rates, or both, with poor quality studies (high and unclear risk of bias) being excluded from the analyses in order to assess whether this makes any difference to the overall result. If future updates include cluster‐randomised trials, we will also acknowledge heterogeneity in the randomisation unit and perform a sensitivity analysis to investigate the effects of the randomisation unit. In future updates, if more eligible studies are included, the impact of including studies with high levels of missing data in the overall assessment of treatment effect will be explored by using sensitivity analysis.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

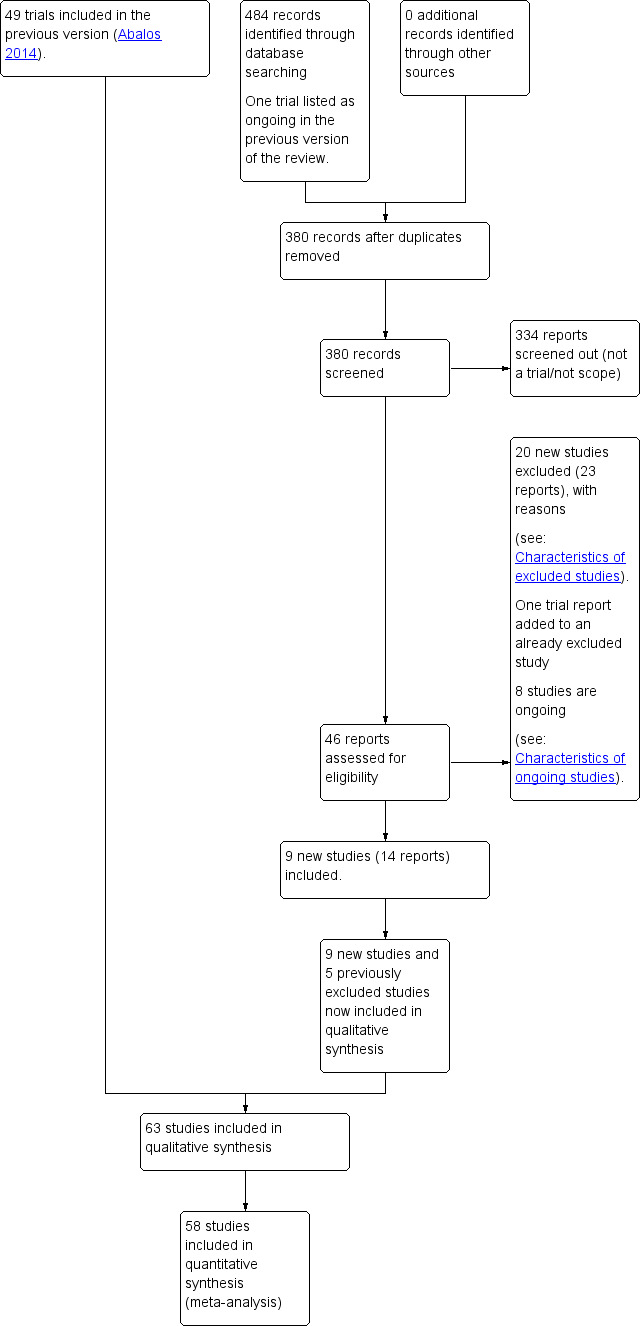

See: Figure 1.

1.

Study flow diagram.

We retrieved 45 trial reports to assess from the updated search in September 2017 and we also reassessed one ongoing trial listed in the previous version of the review. We included nine new trials (14 reports), and five previously excluded studies in the qualitative synthesis and excluded 20 (23 reports) and added an additional reference to an already excluded study. Eight trials are ongoing.

Included studies

In total, 63 studies were included in this review. From these, 58 trials (5909 women) contributed data: 36 trials (3629 women) were conducted in high‐income countries (Australia, France, Hong Kong, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Sweden, UK and USA), and 22 trials (2280 women) in middle‐ or low‐income countries (Argentina, Brazil, Caribbean Islands, India, Pakistan, Panama, South Africa, Sudan and Venezuela).

Methods and trial dates

Three trials (405 women) were published in the 1960s and 1970s, 22 (1854 women) in the 1980s, 17 (1718 women) in the 1990s, and 16 (1927 women) after the year 2000. All included trials are small. The largest study recruited 314 women. Only six studies had comparison arms containing more than 100 women. Two three‐arm trials of methyldopa versus labetalol versus no treatment (India 2012; USA 1990a) were included in the comparison of any antihypertensive with placebo/no antihypertensive, and in the comparison of one drug with another. One three‐arm trial of nifedipine versus methyldopa versus labetalol (India 2015a), was included in the comparison one drug versus another. Another three‐arm trial of furosemide versus amlodipine versus aspirin (Panama 2014), was only included in the comparison one drug versus another (furosemide versus amlodipine), as aspirin is not an antihypertensive and was only prescribed in the third arm.

Funding sources

Six of the included trials reported to be funded by universities or non commercial organisations; 14 trials were funded by industry and two trials stated to have no funding source. The remaining trials provided no information about funding.

Trials authors' declaration of interest

Authors of UK 2017 declared that "C. Nelson‐Piercy reports personal fees from Alliance Pharmaceuticals, UCB Pharmaceuticals, LEO Pharmaceuticals, Sanofi Aventis, and Warner Chilcott outside the submitted work. J.K. Cruickshank is current President of the Artery Society which has had donations from Servier Pharmaceuticals" and that "the other authors report no conflicts". Authors of Brazil 2016, India 2012, India 2013c, India 2015a, India 2015b, Panama 2014 and UK 2009 declared that they had no conflicts of interest. Of the remaining studies, none included any declarations of interest.

Interventions and comparisons

The antihypertensive drugs used in these trials include: alpha agonists (methyldopa), beta blockers (acebutolol, atenolol, labetalol, mepindolol, metoprolol, pindolol, oxprenolol and propranolol), calcium channel blockers (amlodipine, isradipine, nicardipine, nifedipine, nimodipine and verapamil), vasodilators (hydralazine and prazozin), ketanserin, glyceryl trinitrate (GTN), furosemide and sildenafil. All drugs were given orally, except glyceryl trinitrate, which was given transdermally. The dose for several agents varied considerably between studies, in both amount and duration of therapy.

The antihypertensive drug was compared with placebo, or no antihypertensive drug, in 31 trials (3480 women). Of these trials, 17 evaluated beta blockers (1902 women), seven using a placebo for the control group and 10 comparing with no treatment. Methyldopa was evaluated in eight trials (986 women), one comparison with placebo, and seven with no antihypertensive treatment. One trial (118 women) compared isradipine with placebo, another trial (199 women) compared verapamil with placebo, and three studies (583 women) compared nifedipine with no drug treatment. Prazozin was compared with placebo in one trial (32 women), and GTN was compared with placebo patches in another (16 women). Two newly included trials (Brazil 2016; UK 2009) compared sildenafil with placebo in 130 women.

Alternative drug regimens were compared in 30 trials (3093 women). Twenty‐five of these studies compared methyldopa with another agent. In 19 trials (2041 women) the comparison was with beta blockers, in four it was nifedipine (389 women), in one (111 women) it was nimodipine, and in another ketanserin (20 women). Two trials (354 women) compared labetalol versus nifedipine. One small trial (36 women) compared nifedipine with GTN. In one study (100 women), metoprolol was compared with nicardipine and in another (42 women) furosemide was compared with amlodipine (the aspirin arm of this study was not considered for this review).

Gestation at trial entry

Twenty of the 58 included studies contributing to data recruited women during the second and third trimester of pregnancy, and 21 recruited only during the third trimester. Eight studies recruited women during the first and second trimester. Gestational age at trial entry was not reported in nine studies.

Severity and type of hypertension disease at trial entry

Mild to moderate hypertension was defined as a diastolic blood pressure of 90 mmHg or more in 42 studies. In five trials, the definition was 95 mmHg or more and in four it was 100 mmHg or more. In two trials, the cut‐off was 85 mmHg, In the remaining five studies, authors merely stated 'mild to moderate hypertension', or 'pregnancy‐induced hypertension', or 'diagnosed hypertension'. Women with proteinuria were excluded from trial entry in 19 studies, whilst in eight trials all women had proteinuria at recruitment. Fourteen trials included women regardless of whether or not they had proteinuria, and the proportion of women with proteinuria ranged from 4% to 47%. In the remaining 17 trials the presence of proteinuria at trial entry was not reported.

Ten studies only recruited women with chronic hypertension. Women with chronic hypertension were excluded from 22 trials. Ten trials included women regardless of whether or not they had chronic hypertension, although outcomes were often not reported separately. In the remaining 16 trials, chronic hypertension at trial entry was not mentioned.

Methods for measuring blood pressure

Only four trials masked the assessment of blood pressure by using a random zero sphygmomanometer (Australia 1983; UK 1976; UK 1983a; UK 1983b). For assessment of diastolic blood pressure, Korotkoff phase IV sound was used in 16 trials and Korotkoff phase V was used for 10 studies. Criteria for blood pressure measurement were not mentioned in 32 trials.

Definition of small‐for‐gestational age

Small‐for‐gestational age was defined in a variety of ways in the 34 trials reporting this outcome. Five studies used birthweight below the fifth centile and 14 below the 10th centile. Four trials used other definitions, and in the remaining 11 trials, small‐for‐gestational age was not defined.

One outcome specified in our protocol, very low (less than four) five‐minute Apgar score, is not included in this review as it was not reported by any trial.

When pooling the data, and in the absence of statistical heterogeneity, we used fixed‐effect meta‐analysis only for the outcome severe hypertension with the assumption that all drugs are expected to lower blood pressure. For the other outcomes, we used random‐effects meta‐analysis as different drugs' effects might vary due to their different mechanisms of action, dosages, length of treatment, etc.

Excluded studies

Ninety‐six studies were excluded from the review. Of these, 41 were conducted in high‐income countries (Australia, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Israel, Italy, Japan, Netherlands, Sweden, UK and USA), and 55 in low‐ and middle‐income countries (Argentina, Brazil, China, Cuba, Czech Republic, Dominican Republic, Egypt, Hungary, India, Iran, Kuwait, Mexico, Pakistan, Panama, Philippines, Russia, Singapore, Slovakia, South Africa, Sri Lanka, Uganda and Venezuela). The oldest excluded study was published 1957, one was published in 1978, 54 were published in the 1980s and 1990s, and 42 have been published since the millennium.

The language of publication was English (for 78 papers), Chinese (six), Spanish (five), Portuguese (three), Czech (two), French (one), and Russian (one). Language was not a reason for exclusion. Twenty‐six papers (21/101) were published only as congress abstracts, and 13 are protocols registered in ClinicalTrials.Gov or similar pages. They were excluded as the intervention is not eligible (i.e. severe hypertension, prevention trial in high‐risk women, etc). Three studies were excluded after personal communication with authors. Authors of 14 papers provided additional information about methods and/or clinical outcomes. The reasons for exclusions were as follows.

Methodological problems (25 studies): either they were not randomised trials (12 studies) or they used quasi‐random methods for treatment allocation (nine studies), or more than 20% of women were excluded after randomisation (four studies).

Participants were not eligible for the review (18 studies): either some or all of the women had severe hypertension (nine studies), or some women had normal blood pressure, and data were not presented separately for the women with mild to moderate hypertension, or all women were at high risk of developing hypertension in a prophylactic trial (eight studies), or the intervention was administered postpartum (one).

Intervention was not eligible for the review (45 studies): either the comparison was of drugs within the same class (eight studies), or the allocated intervention was for less than seven days (15 trials), or it was not an antihypertensive drug (21) or the study had a mixed control group (one).

No clinical outcomes measured (eight studies): there are no data on clinical outcomes (three congress abstracts, of which authors were contacted but with no responses to date). Three reports were personal communications of planned randomised controlled trials, but no information could be found about their completion.

Risk of bias in included studies

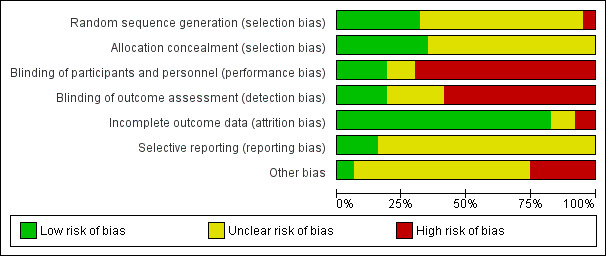

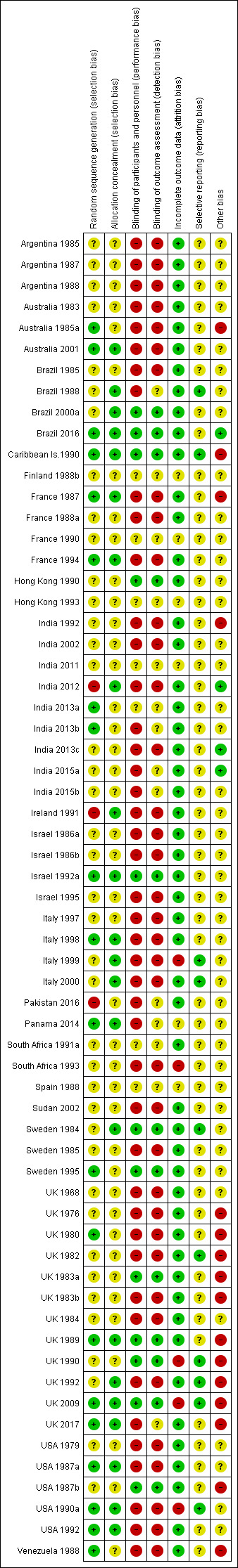

Overall, the quality of the studies included in this review is moderate to poor (Figure 2; Figure 3).

2.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Sequence generation

Methods for generating the random sequence were described in 23 trials out of 63 (36.5%).

We assessed these trials as being at a low risk of bias ‐ methods included computer generation (Australia 2001, France 1994; India 2013a; Italy 1998; Panama 2014; UK 2009; UK 2017; USA 1987a; USA 1990a; USA 1992), random‐number tables (UK 1980; UK 1989; Venezuela 1988), series of random numbers (Australia 1985a; India 2013b; Israel 1992a). Although three studies did not describe the method used for allocation, the authors mentioned that it was in blocks of five (Brazil 2016), six (Sweden 1995), 10 (Caribbean Is.1990), or nine at each centre (France 1987).

We assessed three trials as being at a high risk of bias due to inadequate methods, namely "mixed‐up opaque envelopes" (India 2012), "lottery method" (Pakistan 2016) and "cards shuffled into a random order and numbered in sequence" (Ireland 1991). See Figure 2, Figure 3.

Methods for generating the random sequence were not described in the remaining 40 trials.

Allocation concealment

Concealment of allocation was adequate for only 22 of the 63 trials (34.9%), being unclear whether concealment was adequate in the remaining 41 trials. Methods for concealing the allocation included on‐line computer system (UK 2017), telephone randomisation (Australia 2001; Italy 1998; Sweden 1984; UK 2009), blinded treatment packs (Brazil 1988; Brazil 2000a; Caribbean Is.1990; Israel 1992a; Italy 2000; UK 1989), consecutive, sealed identical envelopes (UK 1992) or blinded or sealed envelopes (Brazil 2016; France 1987; France 1994; India 2012; Ireland 1991; Italy 1999; Panama 2014; USA 1987a; USA 1990a; USA 1992), or just "envelopes" (South Africa 1991a, Sweden 1985; UK 1982). Most trials with unclear concealment of allocation were described as 'randomised' with no details on how this was achieved. Some of these studies were stated to be double blind, but with no information about how this was achieved. Three trials with unclear concealment used random‐number tables without mentioning any attempt to conceal the allocation (Sweden 1995; UK 1980; Venezuela 1988). See Figure 2, Figure 3.

Blinding

Performance bias

From 31 trials evaluating whether or not hypertension should be treated with antihypertensives, only 14 (45%) compared the active drug with placebo, 12 of them were described by authors as double‐blind (Brazil 2000a; Brazil 2016; Caribbean Is.1990; Hong Kong 1990; Israel 1992a; Sweden 1984; Sweden 1995; UK 1983a; UK 1989; UK 1990; UK 2009; USA 1987b). One placebo‐controlled trial was reported as single‐blind (Australia 2001), and another, even though placebo‐controlled, did not mention whether it was single‐ or double‐blinded (South Africa 1991a). See Figure 2, Figure 3

Detection bias

All trials evaluating alternative treatments for mild/moderate hypertension during pregnancy were open‐label trials, and no attempts were made to blind outcome assessment in order to prevent detection bias. See Figure 2, Figure 3

Incomplete outcome data

As per protocol, trials were excluded from the review (or a particular outcome was excluded from the analysis) if it was not possible to enter data on an intention‐to‐treat basis, or lf 20% or more participants were excluded or withdrawn. We also downgraded the score of a trial to a high risk of bias status if more than 10% of randomised women were withdrawn from the analysis. Most trials reported the outcomes for all (or nearly all) women randomised (low risk of bias), although only six trials described the women who met the study eligibility criteria, but were not randomised (Sweden 1984; Sweden 1985; UK 1976; UK 1983a; UK 2009; UK 2017). Five trials reported losses greater than 10%: Italy 1999 (17%), South Africa 1993 (10.3%), UK 1990 (12%), UK 2009 (10.3%) and USA 1990a (12%), with high risk of bias. See Figure 2, Figure 3.

Selective reporting

Thirty‐three trials (52%) reported on the risk of a woman for developing severe hypertension (one of the primary outcomes of this review). However, most trials evaluated the effect that the antihypertensive under scrutiny may have on blood pressure (mean blood pressure after treatment, % fall in blood pressure, etc.). Proteinuria (either new proteinuria or the aggravation of previously existing) was reported in 46 trials. Total reported fetal or neonatal deaths were evaluated in 48 trials, preterm birth in 25 and small‐for‐gestational‐age babies in 28. Most analyses were carried out using data from published reports. Authors were contacted for unpublished information related to the methods and the main outcomes; we obtained data from Australia 2001; Brazil 1988; Brazil 2000a; Caribbean Is.1990; Ireland 1991; Italy 1999; Italy 2000; Sweden 1984; Sweden 1995; UK 1982; UK 1990; UK 1992; USA 1990a. See Figure 2, Figure 3,

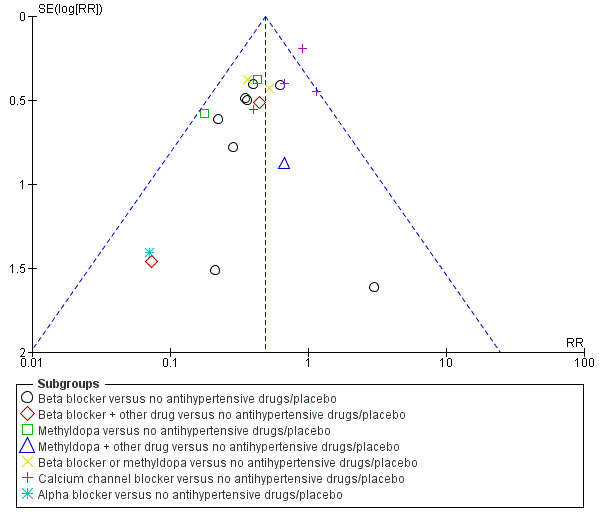

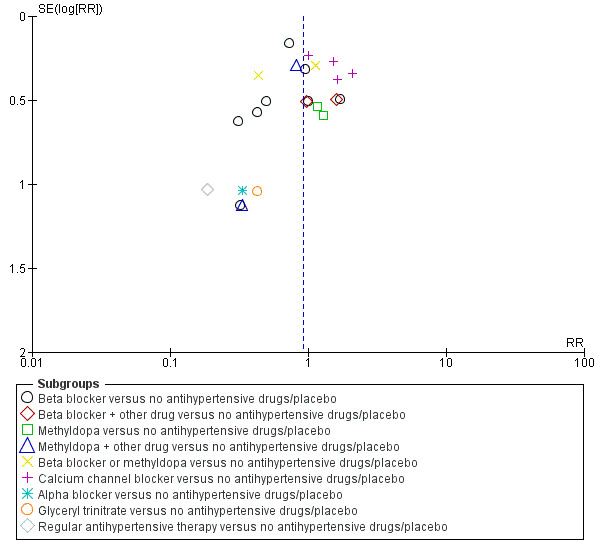

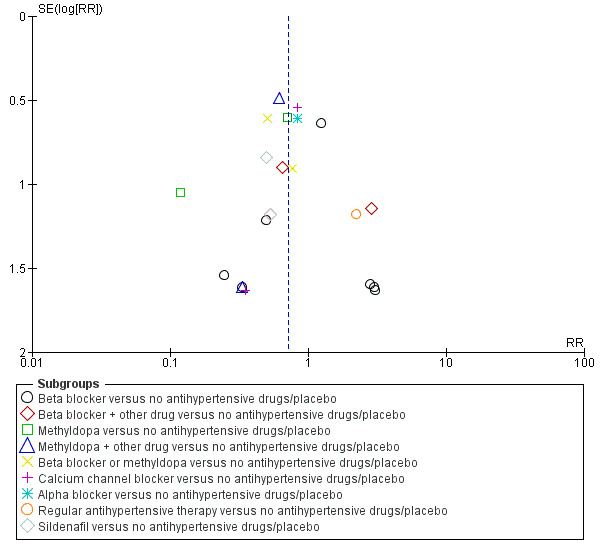

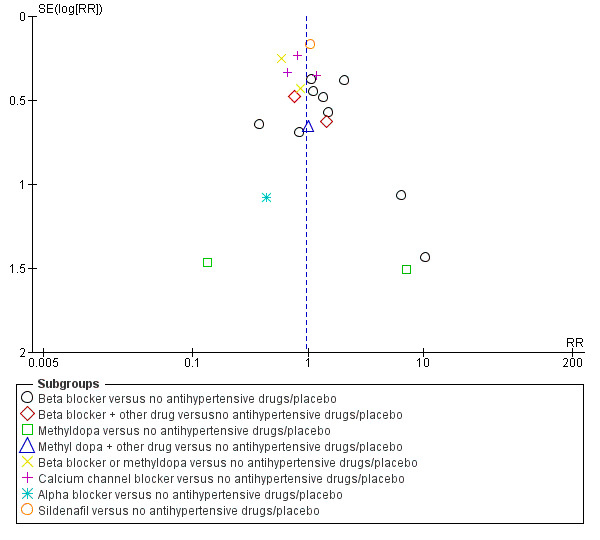

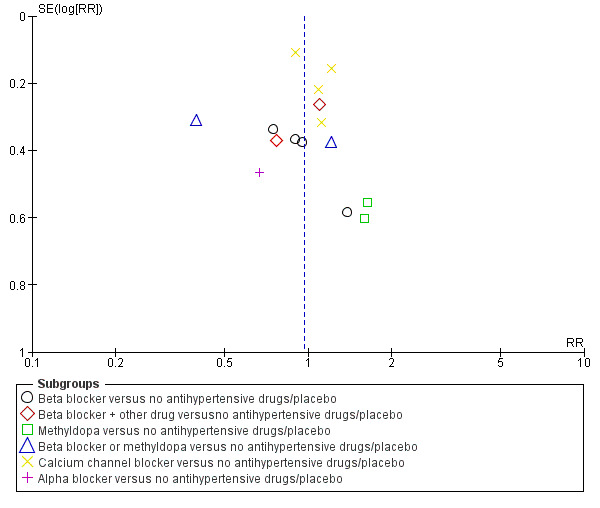

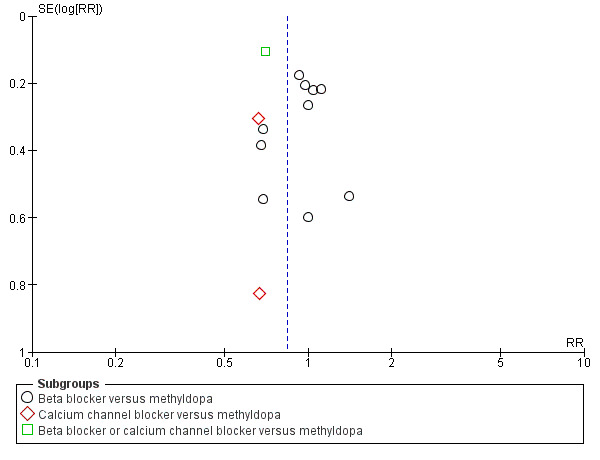

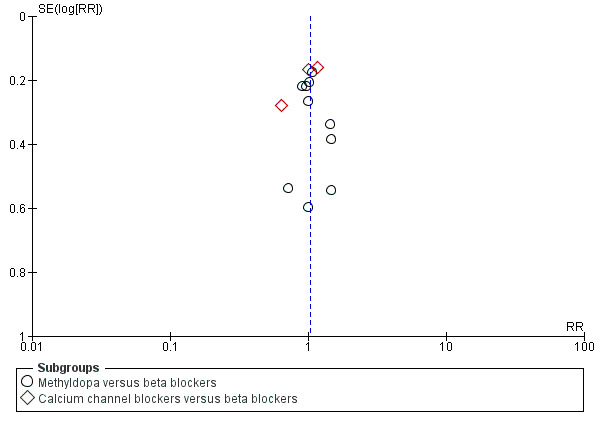

Funnel plots were assessed, see Figure 4; Figure 5; Figure 6; Figure 7; Figure 8; Figure 9; Figure 10; Figure 11; Figure 12; Figure 13; Figure 14; Figure 15; Figure 16; Figure 17; Figure 18; Figure 19; Figure 20; Figure 21; Figure 22; Figure 23; Figure 24; Figure 25.

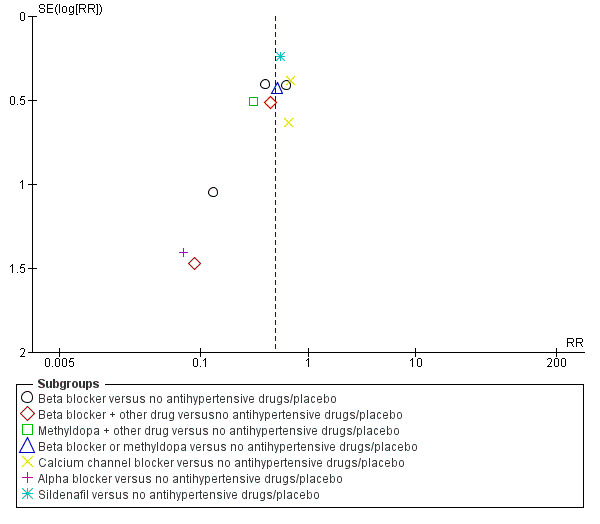

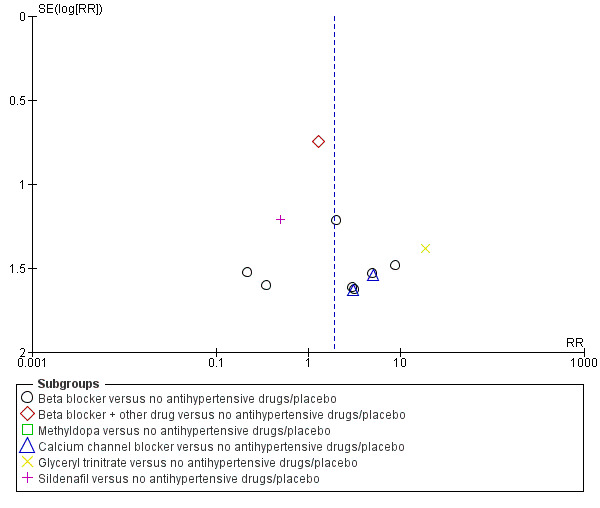

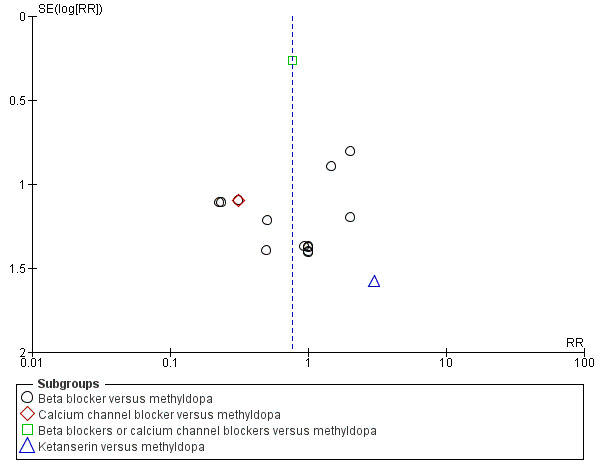

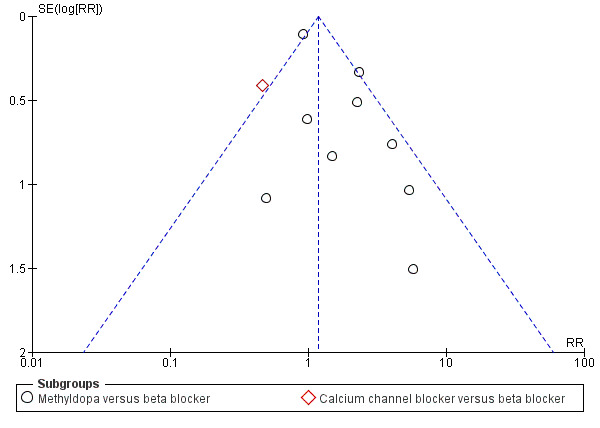

4.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Any antihypertensive drug versus no antihypertensive drugs/placebo (subgrouped by class of drug), outcome: 1.1 Severe hypertension.

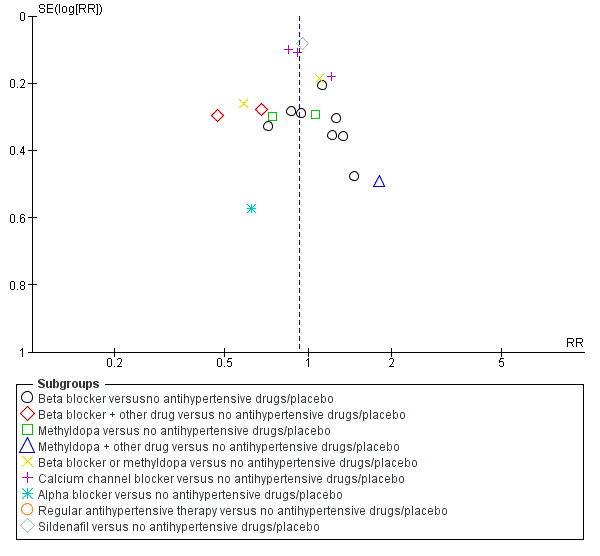

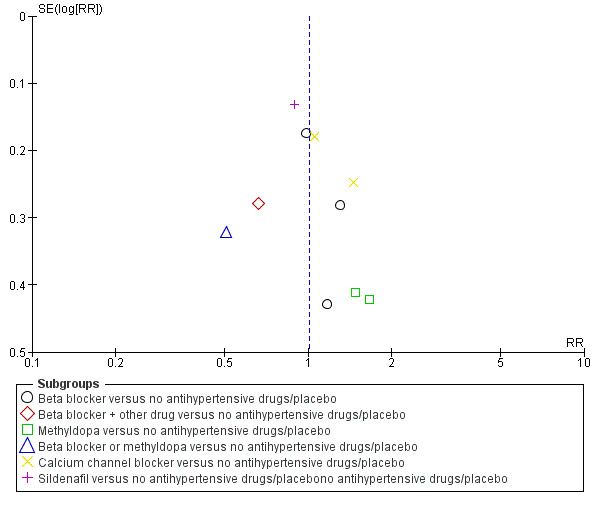

5.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Any antihypertensive drug versus no antihypertensive drugs/placebo (subgrouped by class of drug), outcome: 1.2 Proteinuria/pre‐eclampsia.

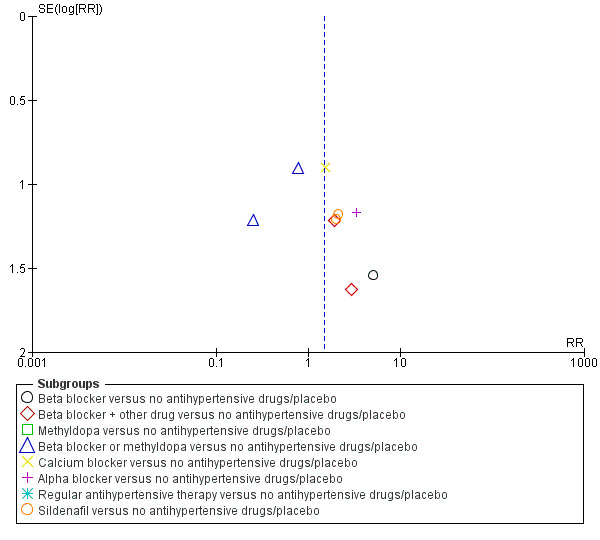

6.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Any antihypertensive drug versus no antihypertensive drugs/placebo (subgrouped by class of drug), outcome: 1.3 Total reported fetal or neonatal death (including miscarriage).

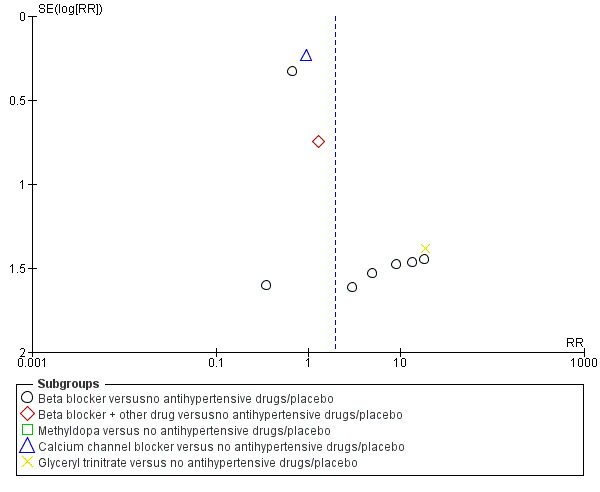

7.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Any antihypertensive drug versus no antihypertensive drugs/placebo (subgrouped by class of drug), outcome: 1.5 Small‐for‐gestational age.

8.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Any antihypertensive drug versus no antihypertensive drugs/placebo (subgrouped by class of drug), outcome: 1.7 Preterm birth (< 37 weeks).

9.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Any antihypertensive drug versus no antihypertensive drugs/placebo (subgrouped by class of drug), outcome: 1.14 Need for additional antihypertensive drug/s.

10.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Any antihypertensive drug versus no antihypertensive drugs/placebo (subgrouped by class of drug), outcome: 1.16 Caesarean section.

11.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Any antihypertensive drug versus no antihypertensive drugs/placebo (subgrouped by class of drug), outcome: 1.19 Placental abruption.

12.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Any antihypertensive drug versus no antihypertensive drugs/placebo (subgrouped by class of drug), outcome: 1.20 Maternal side‐effects.

13.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Any antihypertensive drug versus no antihypertensive drugs/placebo (subgrouped by class of drug), outcome: 1.21 Changed/stopped drugs due to maternal side‐effects.

14.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Any antihypertensive drug versus no antihypertensive drugs/placebo (subgrouped by class of drug), outcome: 1.22 Admission to neonatal or intensive care nursery.

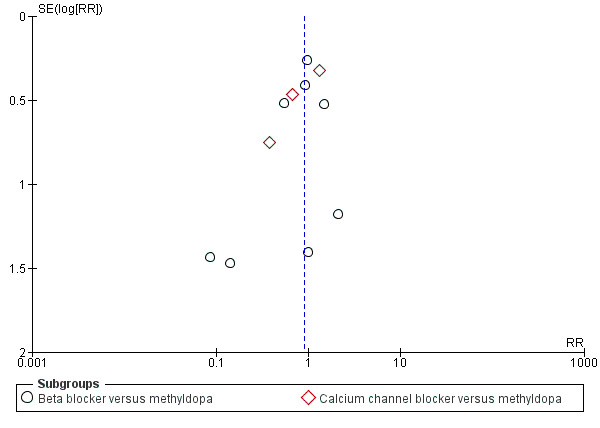

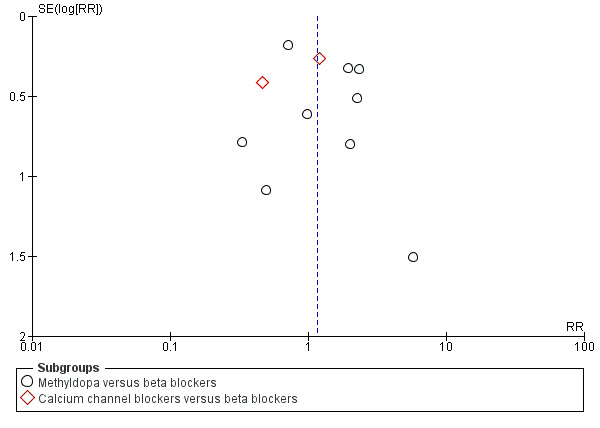

15.

Funnel plot of comparison: 5 Any antihypertensive versus methyldopa (subgrouped by class of drug), outcome: 5.1 Severe hypertension.

16.

Funnel plot of comparison: 5 Any antihypertensive versus methyldopa (subgrouped by class of drug), outcome: 5.2 Proteinuria/pre‐eclampsia.

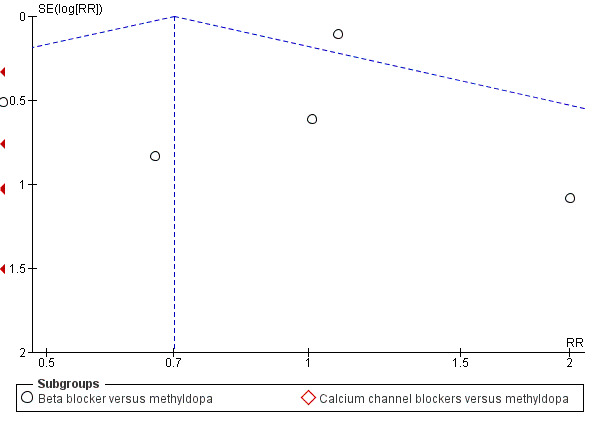

17.

Funnel plot of comparison: 5 Any antihypertensive versus methyldopa (subgrouped by class of drug), outcome: 5.3 Total reported fetal or neonatal death (including miscarriage).

18.

Funnel plot of comparison: 5 Any antihypertensive versus methyldopa (subgrouped by class of drug), outcome: 5.5 Preterm birth (< 37 weeks).

19.

Funnel plot of comparison: 5 Any antihypertensive versus methyldopa (subgrouped by class of drug), outcome: 5.8 Need for additional antihypertensive drug/s.

20.

Funnel plot of comparison: 5 Any antihypertensive versus methyldopa (subgrouped by class of drug), outcome: 5.10 Caesarean section.

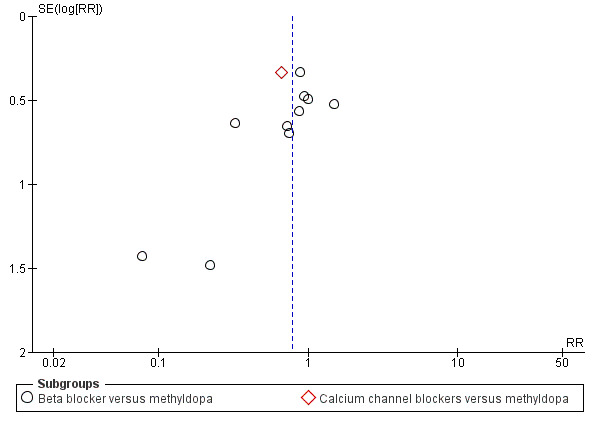

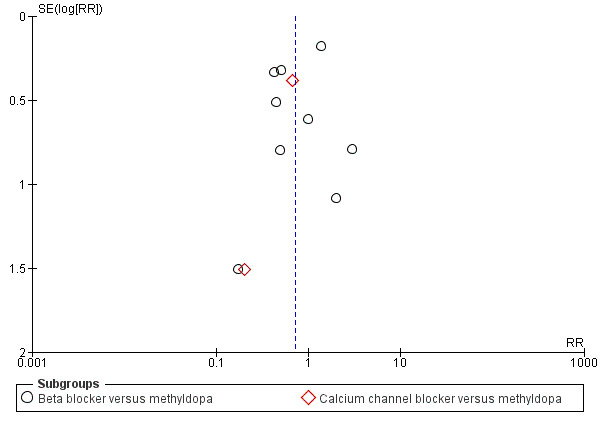

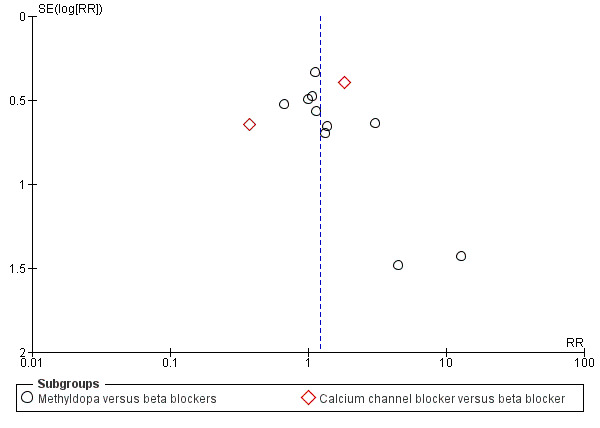

21.

Funnel plot of comparison: 7 Any antihypertensive versus beta blocker (subgrouped by class of drug), outcome: 7.1 Severe hypertension.

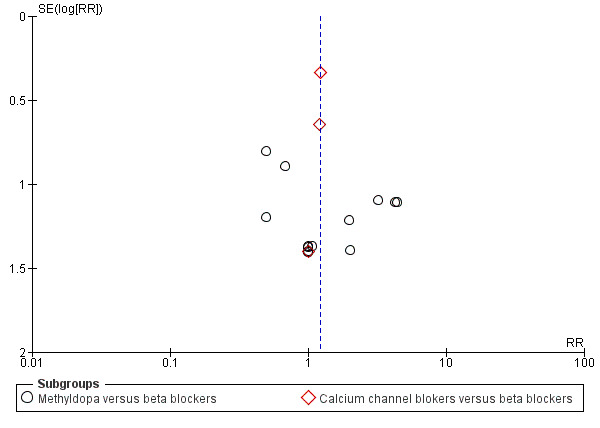

22.

Funnel plot of comparison: 7 Any antihypertensive versus beta blocker (subgrouped by class of drug), outcome: 7.2 Proteinuria/pre‐eclampsia.

23.

Funnel plot of comparison: 7 Any antihypertensive versus beta blocker (subgrouped by class of drug), outcome: 7.3 Total reported fetal or neonatal death (including miscarriage).

24.

Funnel plot of comparison: 7 Any antihypertensive versus beta blocker (subgrouped by class of drug), outcome: 7.11 Need for additional antihypertensive drug/s.

25.

Funnel plot of comparison: 7 Any antihypertensive versus beta blocker (subgrouped by class of drug), outcome: 7.13 Caesarean section.

Other potential sources of bias

Baseline characteristics were similar between groups in most trials, thus in the absence of other potential sources of bias they were scored as at low risk. In one trial (Australia 1985a) co‐interventions were unevenly distributed: 48% of oxprenolol group and 35% of methyldopa group received a second or third antihypertensive. In another study (Caribbean Is.1990), treatment was unblinded in 23 women (15%) and other treatment started, 16 for uncontrolled BP (five experimental, 11 control) and seven for poor compliance/side‐effects (four experimental, three control). In another trial (UK 2017) some baseline characteristics (such as smoking or chronic hypertension) were not balanced. So these three studies were assessed as high risk. In 13 trials, funding source included the Industry totally or partially (France 1987, India 1992UK 1976; UK 1980; UK 1982; UK 1983a; UK 1983b; UK 1989; UK 1990; UK 1992; UK 2009; USA 1987b; Venezuela 1988), so they were assessed as high risk of bias. In 22 studies, the funding sources was not declared and theywere classified as unclear risk of bias.

Informed consent was mentioned in the majority of trials. In one study, informed consent was obtained only from women allocated to the treatment arm (Ireland 1991).

Sample size and power calculations were reported for nine trials (Brazil 2016; Caribbean Is.1990; France 1987; Ireland 1991; Italy 1998; Pakistan 2016; UK 1989; UK 2009; UK 2017).

Effects of interventions

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Any antihypertensive drug compared to no antihypertensive drugs/placebo for mild to moderate hypertension during pregnancy (primary outcomes).

| Any antihypertensive drug compared to no antihypertensive drugs/placebo for mild to moderate hypertension during pregnancy | ||||||

| Patient or population: women with mild to moderate hypertension during pregnancy Setting: hospital settings in high‐ low‐ and middle‐income countries Intervention: any antihypertensive drug (beta blockers, methyldopa, calcium channel blockers, alpha blockers, glyceryl trinitrate, sildenafil) alone or in combination Comparison: placebo or no antihypertensive drug | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with no drugs/placebo | Risk with any antihypertensive drug | |||||

| Maternal | ||||||

| Severe hypertension | Study population | RR 0.49 (0.40 to 0.60) | 2558 (20 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 2 | ||

| 198 per 1000 | 97 per 1000 (79 to 119) | |||||

| Proteinuria/pre‐eclampsia | Study population | RR 0.92 (0.75 to 1.14) | 2851 (23 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 3 4 | ||

| 185 per 1000 | 171 per 1000 (139 to 211) | |||||

| Fetal/neonatal/infant | ||||||

| Total reported fetal or neonatal deaths (including miscarriage) | Study population | RR 0.72 (0.50 to 1.04) | 3365 (29 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 2 | ||

| 41 per 1000 | 28 per 1000 (20 to 40) | |||||

| Small‐for‐gestational age | Study population | RR 0.96 (0.78 to 1.18) | 2686 (21 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 2 | ||

| 152 per 1000 | 149 per 1000 (125 to 176) | |||||

| Preterm birth (< 37 weeks) | Study population | RR 0.96 (0.83 to 1.12) | 2141 (15 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 2 | ||

| 277 per 1000 | 266 per 1000 (236 to 305) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Studies contributing data had design limitations

2 We have not downgraded for indirectness although trials examined a range of different antihypertensive drugs

3 Fairly wide 95% CI but not downgraded for imprecision as the CIs touched but did not cross .75 or 1.25

4 The funnel plot does suggest some asymmetry which may indicate small study effect and possible publication bias

Summary of findings 2. Any antihypertensive drug compared to no antihypertensive drugs/placebo for mild to moderate hypertension during pregnancy (secondary maternal and fetal/neonatal/infant outcomes).

| Any antihypertensive drug compared to no antihypertensive drugs/placebo for mild to moderate hypertension during pregnancy | ||||||

|

Patient or population: women with mild to moderate hypertension during pregnancy

Setting: hospital settings in high‐ low‐ and middle‐income countries Intervention: any antihypertensive drug (beta blockers, methyldopa, calcium channel blockers, alpha blockers, glyceryl trinitrate, sildenafil) alone or in combination Comparison: placebo or no antihypertensive drug | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with no antihypertensive drugs/placebo | Risk with any antihypertensive drug | |||||

| Maternal | ||||||

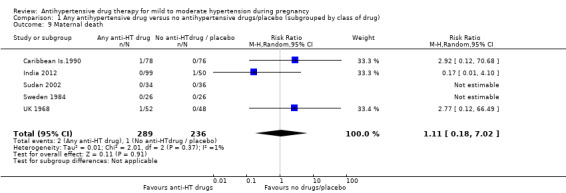

| Maternal death | Study population | RR 1.11 (0.18 to 7.02) | 525 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 2 3 | ||

| 4 per 1000 | 5 per 1000 (1 to 20) | |||||

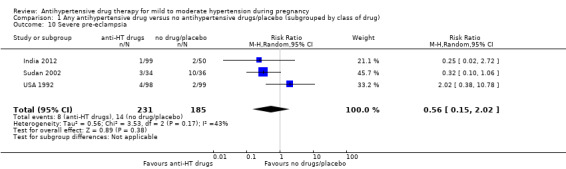

| Severe pre‐eclampsia | Study population | RR 0.56 (0.15 to 2.02) | 416 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 2 3 | ||

| 76 per 1000 | 42 per 1000 (11 to 153) | |||||

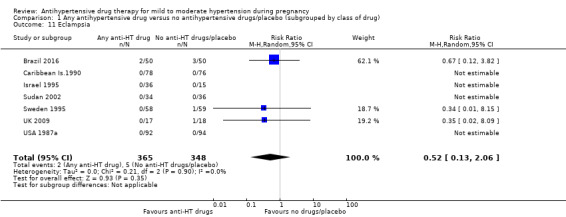

| Eclampsia | Study population | RR 0.52 (0.13 to 2.06) | 713 (7 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 2 3 | ||

| 14 per 1000 | 7 per 1000 (2 to 28) | |||||

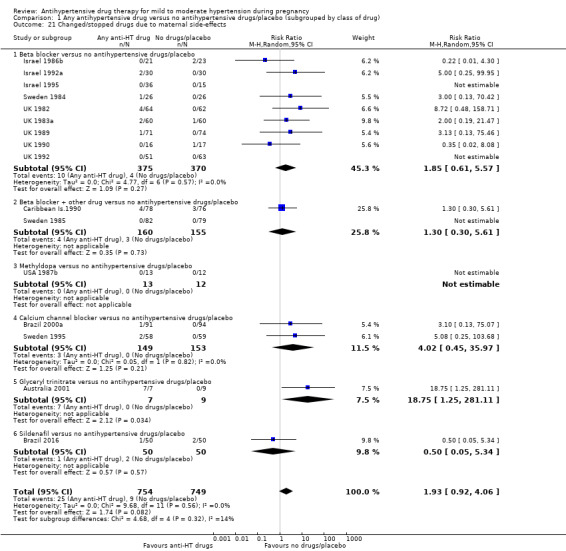

| Changed/stopped drugs due to maternal side‐effects | Study population | RR 1.93 (0.92 to 4.06) | 1503 (16 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 4 | ||

| 12 per 1000 | 27 per 1000 (15 to 51) | |||||

| Elective delivery (induction of labour + elective caesarean section) | Study population | RR 0.93 (0.84 to 1.04) | 710 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 2 | ||

| 716 per 1000 | 651 per 1000 (594 to 716) | |||||

| Fetal/neonatal/infant | ||||||

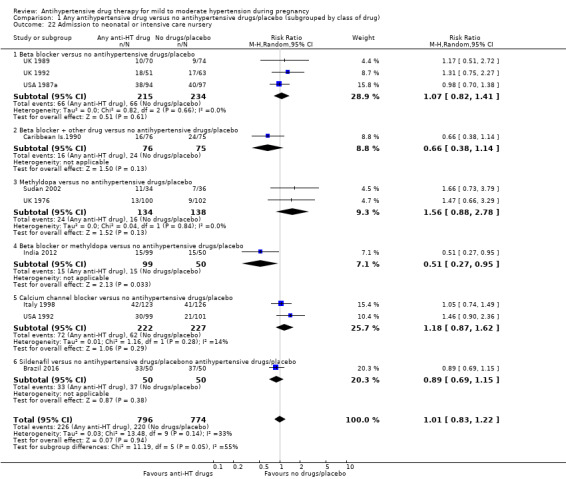

| Admission to neonatal or intensive care nursery | Study population | RR 1.01 (0.83 to 1.22) | 1570 (10 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 5 | ||

| 284 per 1000 | 287 per 1000 (236 to 347) | |||||

| Follow‐up of the children at 1 year: cerebral palsy | Study population | RR 0.33 (0.01 to 8.01) | 110 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 3 | ||

| 18 per 1000 | 6 per 1000 (0 to 146) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Studies contributing data had design limitations

2 We have not downgraded for indirectness although trials examined a range of different antihypertensive drugs

3 Wide 95% CI crossing the line of no effect and low event rate

4 Trials contributing data examined a range of different hypertensive drugs

5 The funnel plot does suggest some asymmetry which may indicate small study effect and possible publication bias

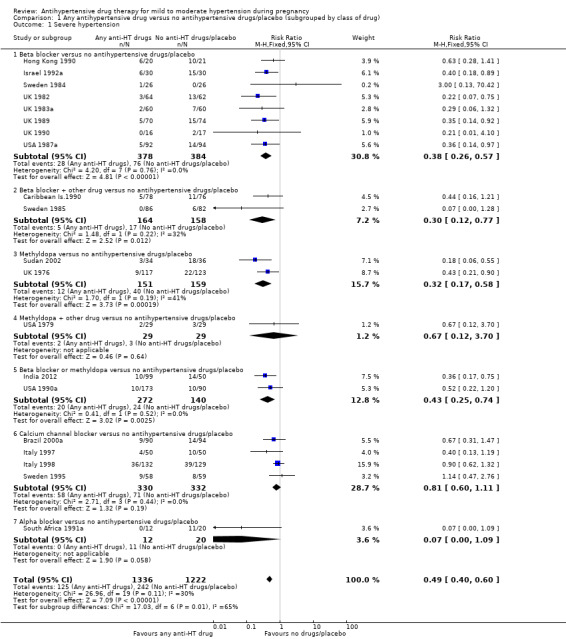

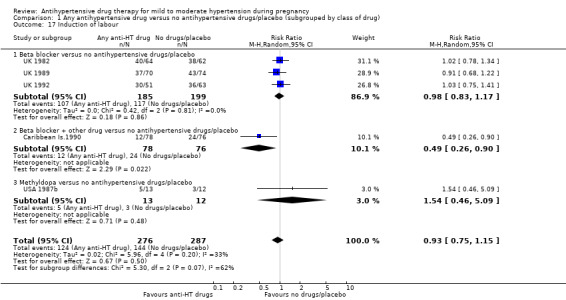

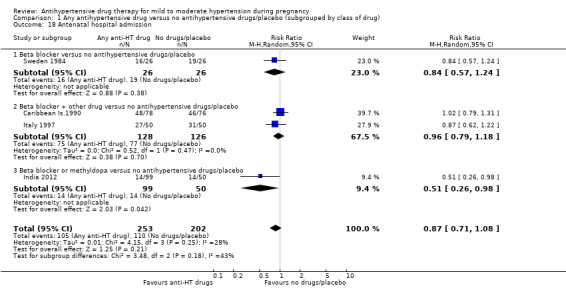

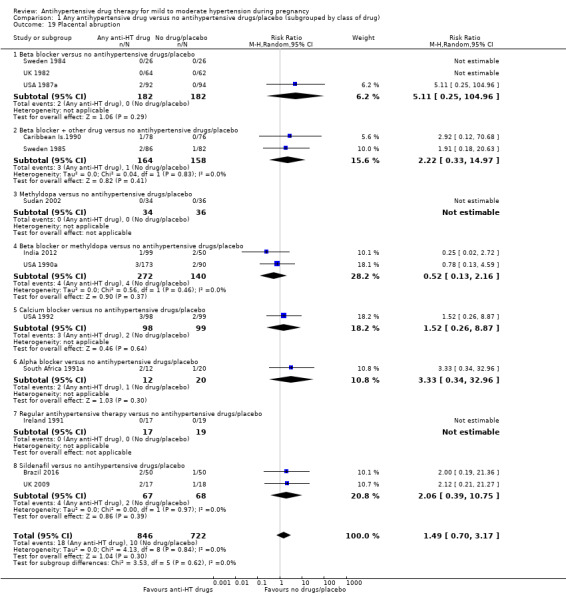

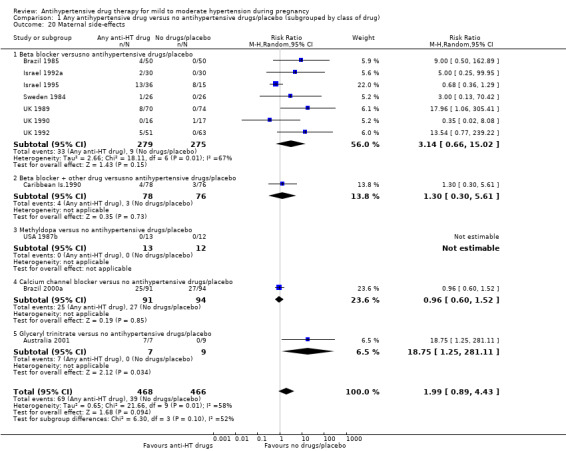

(1) Any antihypertensive drug versus no antihypertensive drugs/placebo

Overall, 31 trials with a total of 3485 women compared an antihypertensive drug with placebo or no antihypertensive drug.

Primary outcomes

Severe hypertension

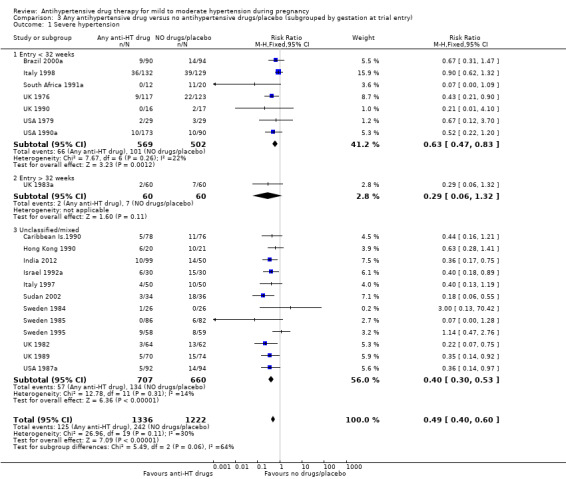

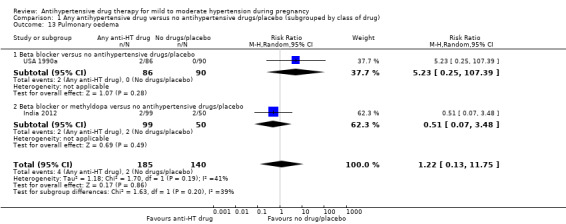

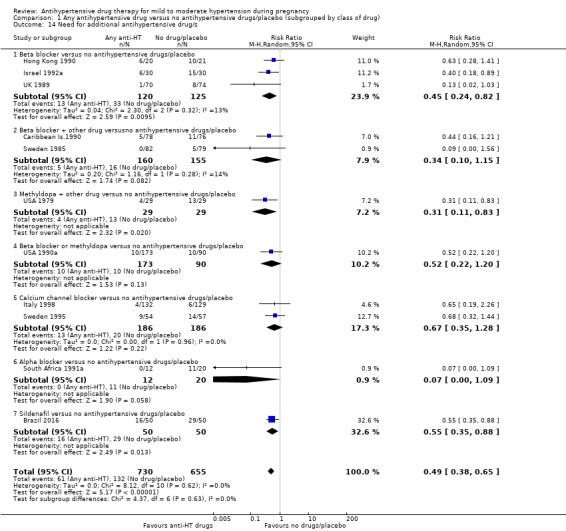

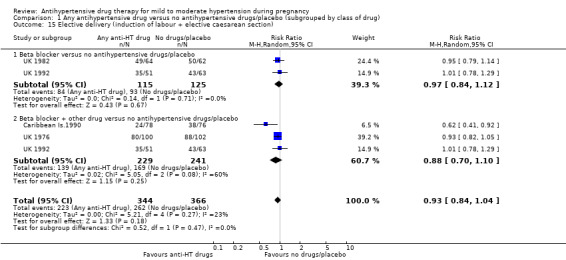

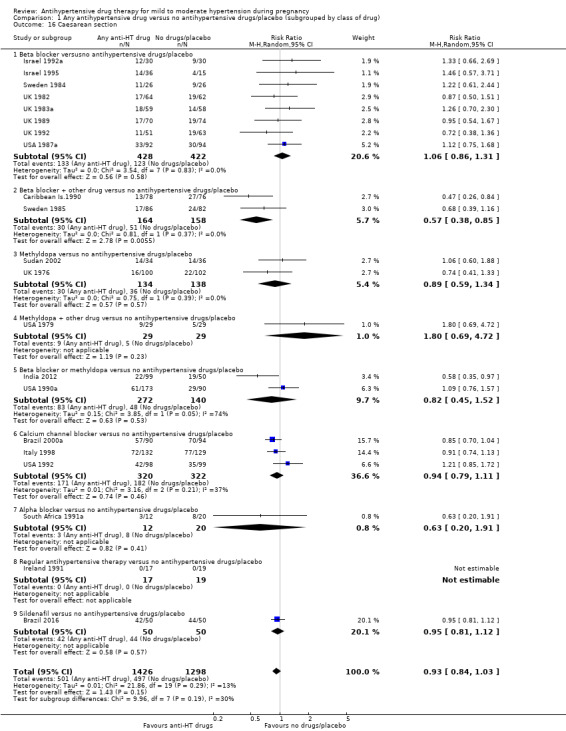

There is probably a halving in the risk of developing severe hypertension associated with the use of antihypertensive drug/s (20 trials, 2558 women; risk ratio (RR) 0.49; (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.40 to 0.60; moderate‐certainty evidence), Analysis 1.1.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Any antihypertensive drug versus no antihypertensive drugs/placebo (subgrouped by class of drug), Outcome 1 Severe hypertension.

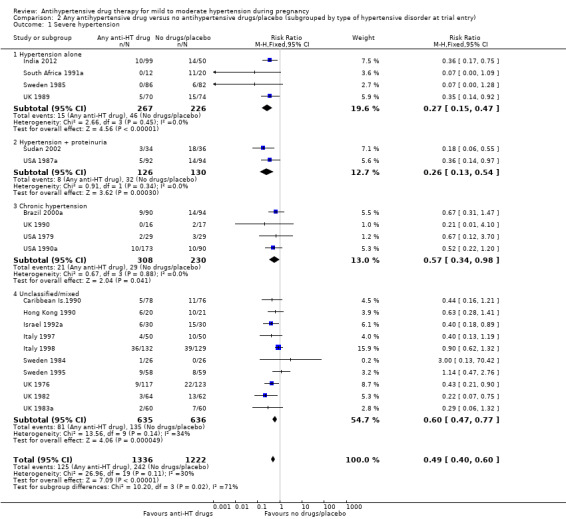

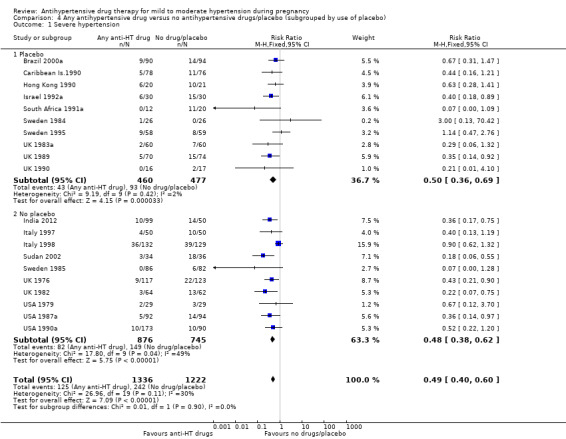

Subgroup analyses Although differences were observed between the classes of drugs subgroups (test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 17.03, df = 6 (P = 0.009), I² = 64.8%), this effect was strikingly consistent regardless of the hypertensive disorder at trial entry hypertension alone: four trials, (493 women) (RR 0.27; 95% CI 0.15 to 0.47), Analysis 2.1.1; hypertension + proteinuria: two trials, (256 women) (RR 0.26; 95% CI 0.13 to 0.54), Analysis 2.1.2; chronic hypertension: four trials, (538 women) (RR 0.57; 95 % CI 0.34 to 0.98), Analysis 2.1.3; unclassified/mixed: 10 trials, (1271 women) (RR 0.60; 95% CI 0.47 to 0.77), Analysis 2.1.4 (test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 10.20, df = 3 (P = 0.02), I² = 70.6%). The same effect was observed when a placebo or no antihypertensive drugs were used for the control group (with placebo: 10 trials (937 women) (RR 0.50, 95 % CI 0.36 to 0.69), Analysis 4.1.1; with no antihypertensive treatment: 10 trials (1621 women) (RR: 0.48, 95 % CI 0.38 to 0.62) Analysis 4.1.2 (test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 0.01, df = 1 (P = 0.90, I² = 0%); or when gestational age at trial entry was less than 32 weeks, seven trials (1071 women) (RR 0.63; 95% CI 0.47 to 0.83) Analysis 3.1,1, or was unclassified/mixed:12 trials (1367 women) (RR 0.40; 95% CI 0.30 to 0.53) Analysis 3.1,3, but not in the only trial recruiting women with gestational age over 32 weeks, (120 women) (RR 0.29; 95% CI 0.06 to 1.32) Analysis 3.1,2 (test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 5.49, df = 2 (P = 0.06), I² = 63.6%).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Any antihypertensive drug versus no antihypertensive drugs/placebo (subgrouped by type of hypertensive disorder at trial entry), Outcome 1 Severe hypertension.

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Any antihypertensive drug versus no antihypertensive drugs/placebo (subgrouped by use of placebo), Outcome 1 Severe hypertension.

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Any antihypertensive drug versus no antihypertensive drugs/placebo (subgrouped by gestation at trial entry), Outcome 1 Severe hypertension.

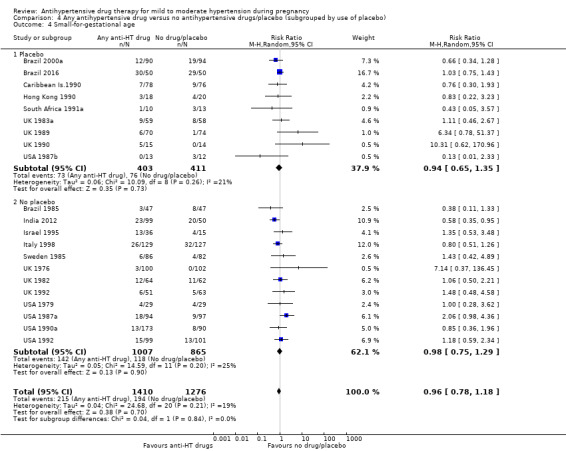

Proteinuria/pre‐eclampsia

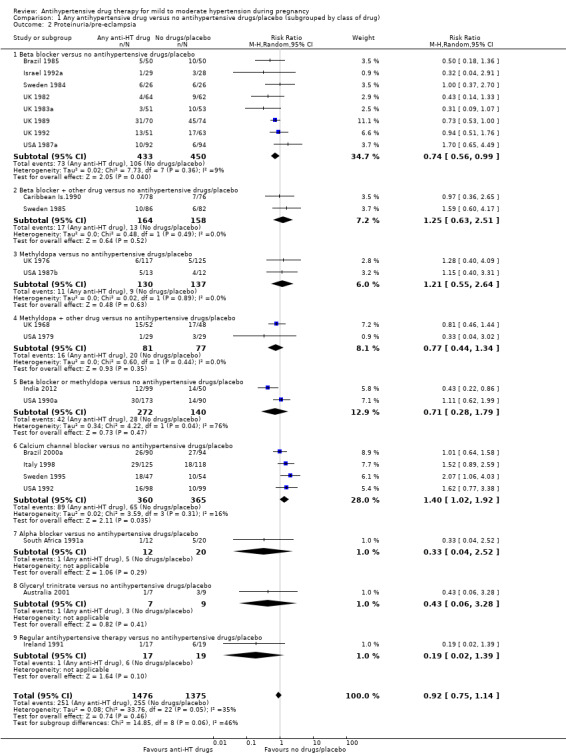

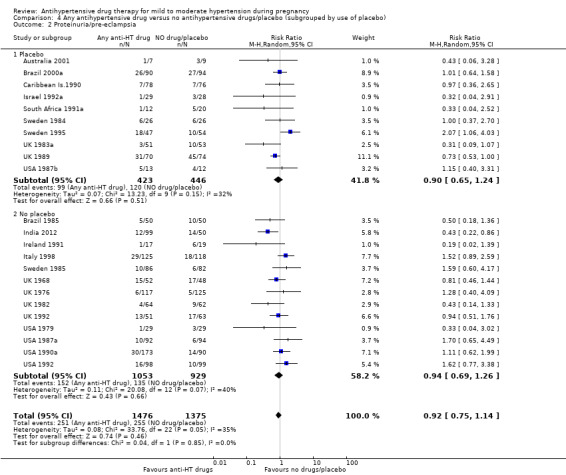

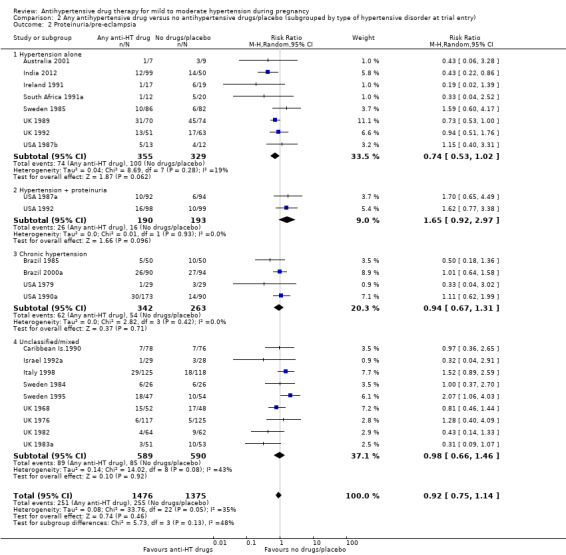

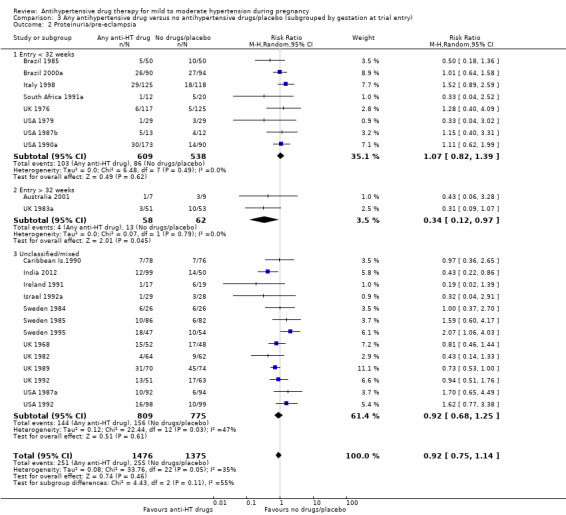

Low‐certainty evidence suggests that there may be little or no difference in the risk of developing proteinuria/pre‐eclampsia in the 23 trials (2851 women) reporting this outcome (average risk ratio (aRR) 0.92, 95% CI 0.75 to 1.14), Analysis 1.2.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Any antihypertensive drug versus no antihypertensive drugs/placebo (subgrouped by class of drug), Outcome 2 Proteinuria/pre‐eclampsia.

Subgroup analyses These results are consistent regardless of the use of placebo (with placebo: aRR 0.90; 95% CI: 0.65 to 1.24; without placebo: aRR 0.94 ; 95% CI 0.69 to 1.26), test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 0.04, df = 1 (P = 0.85), I² = 0%). Analysis 4.2. However, when other subgroups are considered, there is evidence of a difference between subgroups. There is a reduction in the risk of developing proteinuria/pre‐eclampsia in women treated with beta blockers versus no antihypertensive drugs/placebo (eight trials, 883 women; aRR 0.74; 95% CI 0.56 to 0.99) Analysis 1.2.1. However, in trials evaluating calcium channel blockers versus no antihypertensive drugs/placebo (four trials, 725 women), the risk of pre‐eclampsia appears to increase (aRR 1.40; 95% CI 1.02 to 1.92), Analysis 1.2.6. For the other class of drugs, no evidence of an overall difference was found. Test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 14.85, df = 8 (P = 0.06), I² = 46.1%). A reduction in the risk of developing proteinuria/pre‐eclampsia was also seen in those women with hypertension alone, when subgrouped by type of hypertensive disorder at trial entry (eight trials, 684 women; aRR 0.74; 95% CI 0.53 to 1.02), but not in the other subgroups (Test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 5.73, df = 3 (P = 0.13), I² = 47.6%) Analysis 2.2. When subgrouped by gestational age at trial entry, a reduction in the risk was only seen in two trials of 120 women recruited after 32 weeks' gestation (aRR 0.34; 95% CI 0.12 to 0.97), but not in the other subgroups (Test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 4.43, df = 2 (P = 0.11), I² = 54.9%). Analysis 3.2.

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Any antihypertensive drug versus no antihypertensive drugs/placebo (subgrouped by use of placebo), Outcome 2 Proteinuria/pre‐eclampsia.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Any antihypertensive drug versus no antihypertensive drugs/placebo (subgrouped by type of hypertensive disorder at trial entry), Outcome 2 Proteinuria/pre‐eclampsia.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Any antihypertensive drug versus no antihypertensive drugs/placebo (subgrouped by gestation at trial entry), Outcome 2 Proteinuria/pre‐eclampsia.

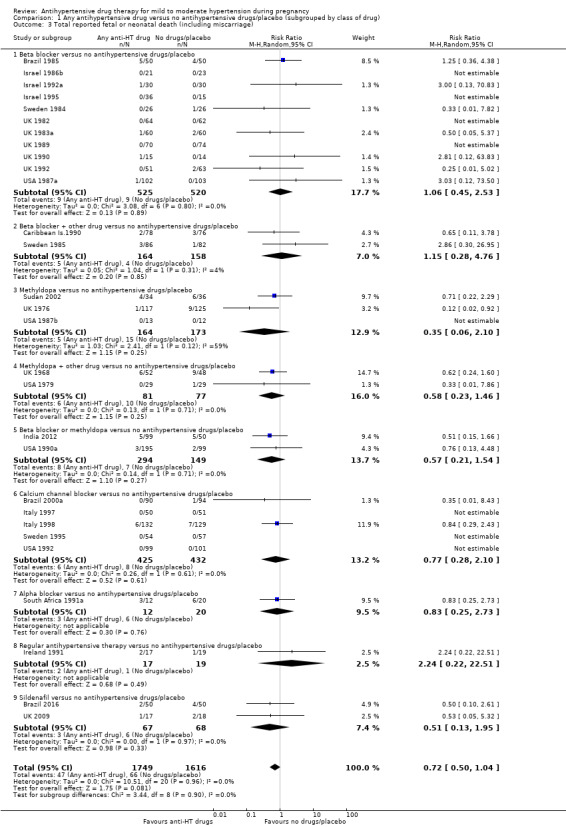

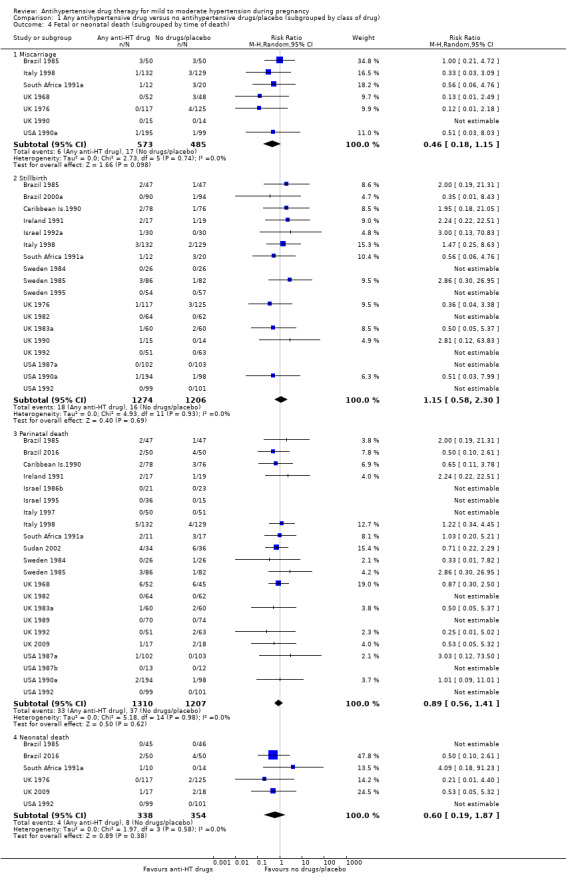

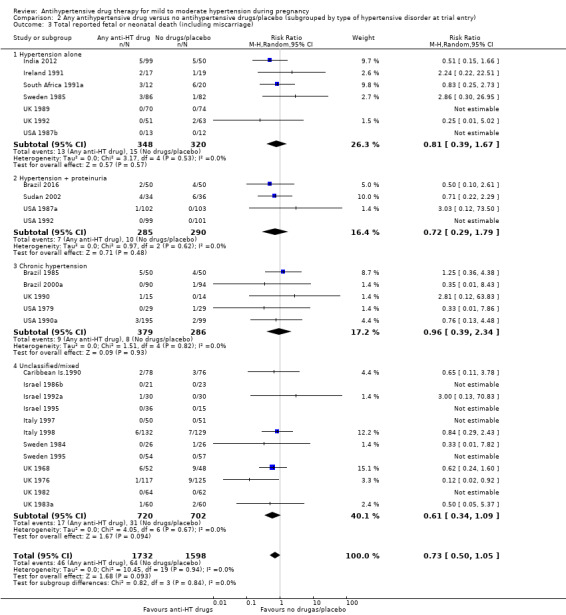

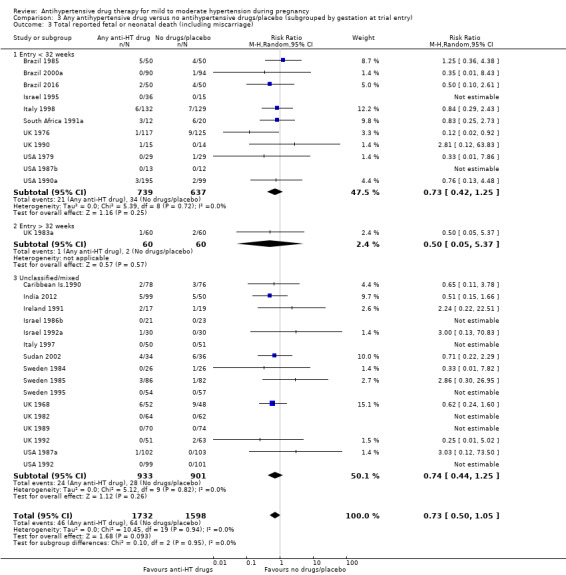

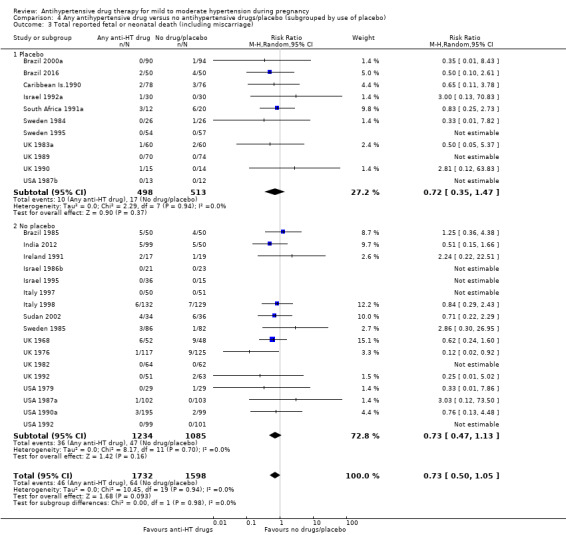

Total reported fetal or neonatal deaths (including miscarriage)

Moderate‐certainty evidence suggests that antihypertensive drug(s) probably have little or no effect on the overall risk of the fetus or baby dying (including miscarriage). The confidence intervals show that the effect includes everything from a 50% reduction to a 4% increase (29 trials, 3365 women; aRR 0.72, 95% CI 0.50 to 1.04; moderate‐certainty evidence), Analysis 1.3.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Any antihypertensive drug versus no antihypertensive drugs/placebo (subgrouped by class of drug), Outcome 3 Total reported fetal or neonatal death (including miscarriage).

Subgroup analyses No evidence of an overall difference was found between any of the pre‐specified subgroups (type of drugs (Analysis 1.3), time of death (Analysis 1.4), of hypertensive disorder at trial entry (Analysis 2.3), gestational age at trial entry Analysis 3.3), or the use of placebo (Analysis 4.3).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Any antihypertensive drug versus no antihypertensive drugs/placebo (subgrouped by class of drug), Outcome 4 Fetal or neonatal death (subgrouped by time of death).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Any antihypertensive drug versus no antihypertensive drugs/placebo (subgrouped by type of hypertensive disorder at trial entry), Outcome 3 Total reported fetal or neonatal death (including miscarriage).

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Any antihypertensive drug versus no antihypertensive drugs/placebo (subgrouped by gestation at trial entry), Outcome 3 Total reported fetal or neonatal death (including miscarriage).

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Any antihypertensive drug versus no antihypertensive drugs/placebo (subgrouped by use of placebo), Outcome 3 Total reported fetal or neonatal death (including miscarriage).

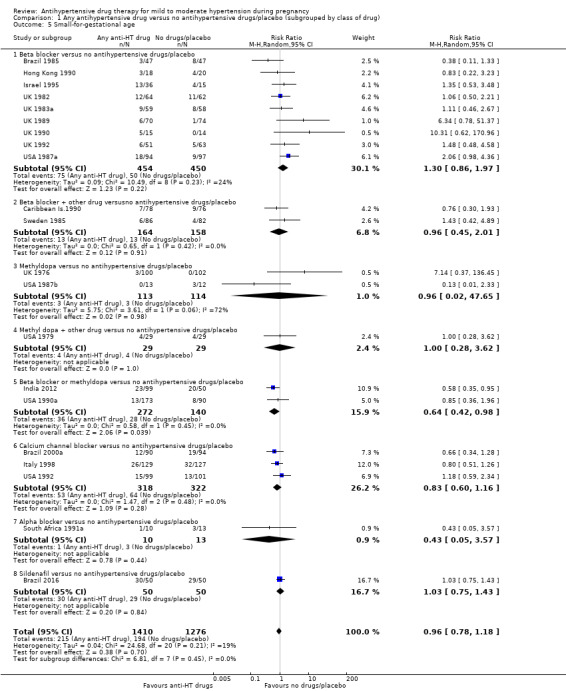

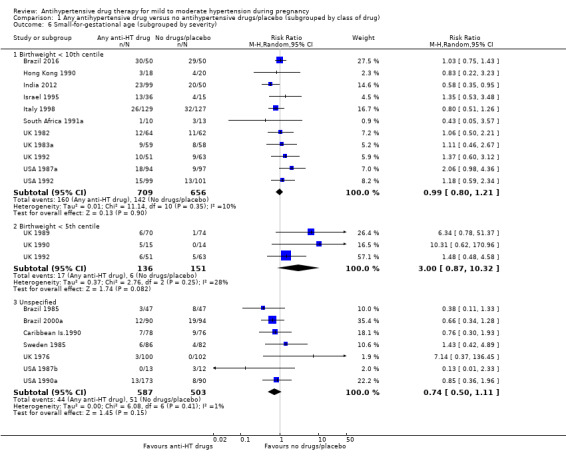

Small‐for‐gestational age

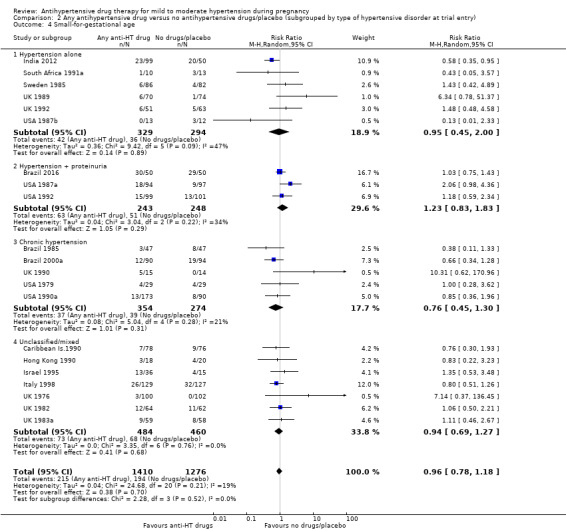

There is probably little or no difference in the risk of having small‐for‐gestational age babies (aRR 0.96; 95% CI 0.78 to 1.18; moderate‐certainty evidence), Analysis 1.5 in the 21 trials (2686 women) reporting this outcome.Figure 9

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Any antihypertensive drug versus no antihypertensive drugs/placebo (subgrouped by class of drug), Outcome 5 Small‐for‐gestational age.

Subgroup analyses No evidence of differences were found between any of the pre‐specified subgroups (severity of intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) (Analysis 1.6), type of hypertensive disorder at trial entry (Analysis 2.4), gestational age at trial entry (Analysis 3.4), use of placebo (Analysis 4.4)). When the subgroup "class of drugs" is considered, a reduction in the risk of having small‐for‐gestational age babies was seen in two small trials (412 women) comparing together beta blocker or methyldopa versus no antihypertensive drugs/placebo (aRR: 0.64; 95% CI 0.42 to 0.98 (Analysis 1.5.5). However, this effect was not seen in the nine trials (904 women) comparing beta blockers versus no antihypertensive drugs/placebo (aRR 1.30; 95% CI 0.86 to 1.97) (Analysis 1.5.1), nor in the two trials (227 women) comparing methyldopa versus no antihypertensive drugs/placebo (aRR 0.96; 95% CI 0.02 to 47.65) (Analysis 1.5.3), nor in the other classes of drugs evaluated (Test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 6.81, df = 7 (P = 0.45), I² = 0%) Analysis 1.5.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Any antihypertensive drug versus no antihypertensive drugs/placebo (subgrouped by class of drug), Outcome 6 Small‐for‐gestational age (subgrouped by severity).

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Any antihypertensive drug versus no antihypertensive drugs/placebo (subgrouped by type of hypertensive disorder at trial entry), Outcome 4 Small‐for‐gestational age.

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Any antihypertensive drug versus no antihypertensive drugs/placebo (subgrouped by gestation at trial entry), Outcome 4 Small‐for‐gestational age.

4.4. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Any antihypertensive drug versus no antihypertensive drugs/placebo (subgrouped by use of placebo), Outcome 4 Small‐for‐gestational age.

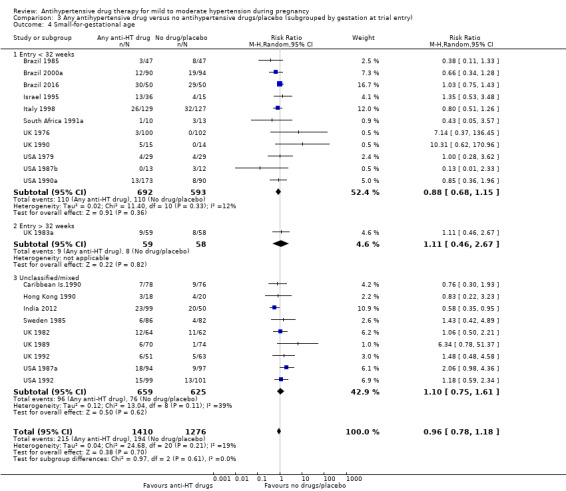

Preterm birth (less than 37 weeks)