Abstract

Background

Nutritional support in the critically ill child has not been well investigated and is a controversial topic within paediatric intensive care. There are no clear guidelines as to the best form or timing of nutrition in critically ill infants and children. This is an update of a review that was originally published in 2009. .

Objectives

The objective of this review was to assess the impact of enteral and parenteral nutrition given in the first week of illness on clinically important outcomes in critically ill children. There were two primary hypotheses:

1. the mortality rate of critically ill children fed enterally or parenterally is different to that of children who are given no nutrition; 2. the mortality rate of critically ill children fed enterally is different to that of children fed parenterally.

We planned to conduct subgroup analyses, pending available data, to examine whether the treatment effect was altered by:

a. age (infants less than one year versus children greater than or equal to one year old); b. type of patient (medical, where purpose of admission to intensive care unit (ICU) is for medical illness (without surgical intervention immediately prior to admission), versus surgical, where purpose of admission to ICU is for postoperative care or care after trauma).

We also proposed the following secondary hypotheses (a priori), pending other clinical trials becoming available, to examine nutrition more distinctly:

3. the mortality rate is different in children who are given enteral nutrition alone versus enteral and parenteral combined; 4. the mortality rate is different in children who are given both enteral feeds and parenteral nutrition versus no nutrition.

Search methods

In this updated review we searched: the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL 2016, Issue 2); Ovid MEDLINE (1966 to February 2016); Ovid EMBASE (1988 to February 2016); OVID Evidence‐Based Medicine Reviews; ISI Web of Science ‐ Science Citation Index Expanded (1965 to February 2016); WebSPIRS Biological Abstracts (1969 to February 2016); and WebSPIRS CAB Abstracts (1972 to February 2016). We also searched trial registries, reviewed reference lists of all potentially relevant studies, handsearched relevant conference proceedings, and contacted experts in the area and manufacturers of enteral and parenteral nutrition products. We did not limit the search by language or publication status.

Selection criteria

We included studies if they were randomized controlled trials; involved paediatric patients, aged one day to 18 years of age, who were cared for in a paediatric intensive care unit setting (PICU) and had received nutrition within the first seven days of admission; and reported data for at least one of the pre‐specified outcomes (30‐day or PICU mortality; length of stay in PICU or hospital; number of ventilator days; and morbid complications, such as nosocomial infections). We excluded studies if they only reported nutritional outcomes, quality of life assessments, or economic implications. Furthermore, we did not address other areas of paediatric nutrition, such as immunonutrition and different routes of delivering enteral nutrition, in this review.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently screened the searches, applied the inclusion criteria, and performed 'Risk of bias' assessments. We resolved discrepancies through discussion and consensus. One author extracted data and a second checked data for accuracy and completeness. We graded the evidence based on the following domains: study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness, and publication bias.

Main results

We identified only one trial as relevant. Seventy‐seven children in intensive care with burns involving more than 25% of the total body surface area were randomized to either enteral nutrition within 24 hours or after at least 48 hours. No statistically significant differences were observed for mortality, sepsis, ventilator days, length of stay, unexpected adverse events, resting energy expenditure, nitrogen balance, or albumin levels. We assessed the trial as having unclear risk of bias. We consider the quality of the evidence to be very low due to there being only one small trial. In the most recent search update we identified a protocol for a relevant randomized controlled trial examining the impact of withholding early parenteral nutrition completing enteral nutrition in pediatric critically ill patients; no results have been published.

Authors' conclusions

There was only one randomized trial relevant to the review question. Research is urgently needed to identify best practices regarding the timing and forms of nutrition for critically ill infants and children.

Plain language summary

Nutrition for critically ill children in paediatric intensive care units

There is little evidence to support or refute the need to provide nutrition to critically ill children in a paediatric intensive care unit during the first week of their critical illness.

Giving nutrition in the form of tube feeding (enteral) or intravenous feeding (parenteral) is often considered a priority during critical illness in children. There are reasons to think this may not necessarily be true. During critical illness the body's metabolism is changed and the need for calories is reduced. There are known side effects from giving too much nutrition, such as delays in being able to take the child off a respiratory ventilator, liver problems, and worsened inflammation.

We found only one small randomized controlled trial that compared early feeding (within 24 hours of injury) with conventional feeding (after at least 48 hours). The trial showed no differences between the groups for any of the outcomes examined. Further research in this area is urgently needed to help guide optimal treatment of children with critical illness. In a recent search update (February 2016) we identified a protocol for a relevant randomized controlled study; however, no results have yet been published.

Summary of findings

for the main comparison.

| Enteral nutrition within 24 hours compared with enteral nutrition after at least 48 hours for critically ill children | ||||||

|

Patient or population: children with critical illness Settings: paediatric intensive care unit Intervention: enteral nutrition within 24 hours Comparison: enteral nutrition after at least 48 hours | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| [control] | [experimental] | |||||

| Mortality | 83 per 1000 | 111 per 1000 | RR 1.33 (0.32 to 5.54) | 72 (1) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low | — |

| Sepsis | 583 per 1000 | 472 per 1000 | RR 0.81 (0.52 to 1.26) | 72 (1) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low | — |

| Ventilator days | Mean 22.5 (SD 4.2) | Mean 24.5 (SD 4.6) | MD 2.00 (‐0.03 to 4.03) | 72 (1) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low | — |

| Length of stay (days) | Mean 54.8 (SD 4.6) | Mean 54.8 (SD 5.9) | MD 0.00 (‐2.44 to 2.44) | 72 (1) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low | — |

| Unexpected adverse events | 83 per 1000 | 222 per 1000 | RR 2.67 (0.77 to 9.25) | 72 (1) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low | — |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference; RR: risk ratio; SD: standard deviation | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

Background

Nutritional support in the critically ill child has not been well investigated and is a controversial topic in paediatric critical care medicine. There are no clear guidelines for the optimal timing and form of nutritional support in these children. There are several lines of evidence that suggest further investigation is required into whether any form of nutritional support is beneficial in the first week of critical illness in children, and these are discussed below.

We have defined nutritional support as the provision of energy in the form of glucose, protein, or lipid to provide calories and substrate for metabolism. Metabolic support can be defined as provision of these calories at basal metabolic rate, without any intention of supporting anabolic activities such as growth or activities of daily living. Accordingly, metabolic support is a form of nutritional support. For the purposes of this review, we defined critical illness as any illness requiring admission to a paediatric intensive care unit.

Metabolism during critical illness

Critical illness often results in altered cellular energy metabolism (Fink 2001; Joffe 2001; Mizock 1984; Protti 2006). Although the mechanisms and exact alterations are poorly understood, it is clear that protein catabolism and mitochondrial dysfunctions with metabolic suppression can occur (Joffe 2001; Mizock 1984). The suggestion that an increased metabolic rate occurs in adults with critical illness has been questioned (Miles 2006). Similarly, the metabolic rate measured in children with critical illness is most often at or below the predicted basal metabolic rate in the first week of illness (Avitzur 2003; Briassoulis 2000; Framson 2007; Jacsik 2001; Letton 1995; Martinez 2004; Oosterveld 2006; White 2000); anabolism (with growth) does not occur (Chwals 1994).

Underfeeding and overfeeding during critical illness

Overfeeding has important adverse effects during critical illness (Chwals 1994; Zaloga 1994). Excess carbohydrate intake can increase carbon dioxide production and impede ventilator weaning (Chwals 1994). Excess protein does not prevent catabolism and can even increase catabolism of body protein (Chwals 1994; Shew 1999; Stroud 2007). High calorific intake can increase fat deposition, including in the liver (Chwals 1994; Hart 2002; Zaloga 1994). In animal models, lower calorific goals were associated with weight loss and improved survival from critical illness (Alexander 1989; Yamazaki 1986). Some adult human studies suggest that underfeeding during critical illness is associated with improved survival and reduced length of stay in hospital (Ash 2005; Boitano 2006; Dickerson 2002; Jeejeebhoy 2004; Krishnan 2003). This is compatible with the finding in many types of animals that a 30% to 50% restriction of calories increases their lifespan and resistance to diseases of aging and oxidative damage (with similar pathophysiology to critical illness inflammatory cascades) (Bordone 2005).

Adult nutritional trials during critical illness

There have been several systematic reviews of nutritional support in critically ill adults. Koretz et al found no compelling evidence that enteral nutrition improved outcomes in critically ill adults when compared to no treatment or parenteral nutrition (Koretz 2007a; Koretz 2007). Koretz found no evidence that parenteral nutrition had an effect on clinical outcomes compared to not providing artificial nutrition (Koretz 2007b). A consensus statement published by the American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition in 1997 pointed out that "although it has been assumed that nutrition support is clinically beneficial in this [critically ill] patient population, this hypothesis has not been tested by well‐designed clinical trials..." (Klein 1997). This was reaffirmed, in 2002, with the statement that "It appears reasonable to recommend that some form of supplemental nutritional support be started after 5 to 10 days of fasting in patients who are likely to remain unable to eat for an additional week or more" (ASPEN 2002). Canadian researchers have published systematic reviews showing that parenteral nutrition was associated with more infectious complications than enteral nutrition (Gramlich 2004); parenteral nutrition did not improve clinically important outcomes compared to standard care (Heyland 1998a); and combined parenteral and enteral nutrition did not improve clinically important outcomes in critically ill adults compared to enteral nutrition alone (Dhaliwal 2004). Others have found poor evidence that early enteral nutrition is better than early parenteral nutrition (Peter 2005; Simpson 2005), although this is controversial (Heyland 2003). Part of the reason for the controversy is that many of the trials were not of optimal quality (Preiser 2003). "The point at which 'safe' starvation ends and malnutrition‐related complications begin has yet to be defined" (Preiser 2003).

Surrogate outcomes

Many clinicians have assumed that early nutritional support is required for critically ill children and adults. Malnutrition is associated with poor outcomes and nutritional support can improve surrogate nutritional outcomes, such as immune function, wound healing, and measured proteins (Briassoulis 2001; Heyland 1998b). In adult studies, however, there is a poor concordance between nutritional markers and clinical outcomes (Koretz 2005). Although it seems intuitive that providing nutrition will be of benefit, because malnutrition is harmful, it does not necessarily follow that nutritional support during the first week of illness improves a critically ill patient's outcome.

Paediatric differences

The American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition statements from 1997 and 2002 indicated that no randomized controlled trials of nutritional support in children with critical illness had been found (ASPEN 2002; Klein 1997). The nutritional needs of children with critical illness may be different from adults in many ways: in terms of underlying metabolism and growth, underlying illness and co‐morbidities, pre‐existing energy reserves (particularly in young infants), and responses to critical illness. It would be ideal to have studies specific to children to guide nutritional support in critically ill children.

For these reasons, a systematic review is needed to identify any randomized controlled trials of nutritional support during the first week of illness in critically ill children. Evidence is needed to provide clear guidelines for how and when to initiate feedings in children requiring intensive care. We did not include premature or low birth weight neonates as their care is in a neonatal intensive care unit and their needs are very likely to be different from infants and children during the first week of critical illness.

Objectives

The objective of this review was to assess the impact of enteral and parenteral nutrition given in the first week of illness on clinically important outcomes in critically ill children. There were two primary hypotheses:

1. the mortality rate of critically ill children fed enterally or parenterally is different to that of children who are given no nutrition; 2. the mortality rate of critically ill children fed enterally is different to that of children fed parenterally.

We planned to conduct subgroup analyses, pending available data, to examine whether the treatment effect was altered by:

a. age (infants less than one year versus children greater than or equal to one year old); b. type of patient (medical, where purpose of admission to intensive care unit (ICU) is for medical illness (without surgical intervention immediately prior to admission), versus surgical, where purpose of admission to ICU is for postoperative care or care after trauma).

We also proposed the following secondary hypotheses (a priori), pending other clinical trials becoming available, to examine nutrition more distinctly:

3. the mortality rate is different in children who are given enteral nutrition alone versus enteral and parenteral combined; 4. the mortality rate is different in children who are given both enteral feeds and parenteral nutrition versus no nutrition.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We planned to include randomized controlled trials (RCTs), completed or ongoing.

Types of participants

We planned to include trials of paediatric participants, aged one day to 18 years, who were cared for in a paediatric intensive care setting and who received nutrition within the first seven days of admission. We also planned to include studies involving both paediatric and adult participants if data were separately available for paediatric cases cared for in a paediatric intensive care unit (PICU). Studies were to be excluded if participants were primarily adults. We planned to analyse those participants aged less than one year separately from children who were older than one year, if such data were available, given that infants are believed to have higher nutritional requirements compared to older children. Furthermore, medical patients are often studied separately from surgical, critically ill participants (including trauma participants). If there were no studies that differentiated medical from surgical participants, we planned to group these participants in the analysis.

Types of interventions

Participants must have been randomized to receive either:

enteral feeding versus no feeding;

total parenteral nutrition versus no feeding;

enteral versus total parenteral nutrition;

enteral versus enteral with supplemental parenteral nutrition.

We did not address other areas of paediatric nutrition, such as immunonutrition versus normal nutrition and different routes of delivering enteral nutrition, in this review.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

30‐day mortality. If this was not available, then paediatric intensive care unit (PICU) mortality.

Secondary outcomes

Length of stay in the PICU.

Length of stay in hospital.

Number of days on the ventilator.

Morbid complications including nosocomial infections.

We were not interested in nutritional outcomes. Data for quality of life assessments and economic implications were to be extracted if reported in studies meeting all other criteria.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

In this updated review, we searched the following bibliographic databases: the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL 2016, Issue 2); Ovid MEDLINE (1966 to February 2016 ); Ovid EMBASE (1988 to February 2016 ); OVID Evidence‐Based Medicine Reviews (includes Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, CENTRAL, ACP Journal Club, and Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effectiveness (DARE)); ISI Web of Science ‐ Science Citation Index Expanded (1965 to February 2016); WebSPIRS Biological Abstracts (1969 to February 2016); and WebSPIRS CAB Abstracts (1972 to February 2016). We also searched the following trial registries: ClinicalTrials.gov; CenterWatch Clinical Trials Listing Service; Current Controlled Trials; GlaxoSmithKline Clinical Trial Register; National Clinical Trials Registry and the National Research Register (all found at www.ualberta.ca/ARCHE/litsearch.html#trials).

Searching other resources

We reviewed the reference lists of all potentially relevant studies; handsearched relevant conference proceedings(British Association for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (2005 to 2007), European Society of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (2005 to 2007), and American Society of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (2005 to 2007)); and contacted primary authors and experts in the area (n = 5), and manufacturers of enteral (n = 5) and parenteral (n = 2) nutritional products.

We did not limit the search by language or publication status.

The search strategies are shown in Appendix 1.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

The selection of studies involved two steps. First, two authors (AJ, NA) independently screened the search results to identify citations with potential relevance. Second, we obtained the full text of selected articles. Two authors (AJ, NA) independently decided on trial inclusion using a standard form with predetermined eligibility criteria.

Data extraction and management

Two authors (NA, LL, or BV) planned to extract data from each study and resolve discrepancies through discussion and by referring to the original paper. We planned to request unpublished data from authors, when necessary. We developed a standard form to describe the following: characteristics of the study (design, method of randomization, withdrawals or dropouts); participants (age, gender); test intervention (type, dose, route of administration, timing and duration of therapy, co‐interventions); control intervention (agent and dose); outcomes (types of outcome measures, timing of outcomes, adverse effects); and results.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed risk of bias. We planned to provide overall 'Risk of bias' assessments. In addition, we planned to describe and display the risk of bias information by individual components. Each component was to be classified as high, low, or unclear. We planned to examine the effect of methodological quality through sensitivity analyses, as described in the 'Sensitivity analysis' section below. In addition, we planned to record whether or not the studies used an intention‐to‐treat analysis and their funding sources.

Measures of treatment effect

We planned to express dichotomous data (for example, mortality) as risk ratios (RR) and to calculate an overall RR with 95% confidence interval (CI). We planned to express complications as risk differences, due to low event numbers. We planned to derive the number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB) for dichotomous data to help clarify the degree of benefit for a range of baseline risks. We planned to convert continuous data to the mean difference and calculate an overall weighted mean difference (with 95% CI). We planned to summarize time‐to‐event data (for example, length of stay in hospital, number of days on a ventilator) by the log hazards ratio (Parmar 1998), and to calculate an overall log hazards ratio.

Unit of analysis issues

There are no unit of analysis issues to report.

Dealing with missing data

We planned to use data as provided in the available reports and/or manuscripts.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We planned to quantify heterogeneity using the I2 statistic (Higgins 2002). The I2 statistic estimates the per cent variability due to between‐study differences.

Assessment of reporting biases

We planned to test for asymmetry visually, using a funnel plot, and quantitatively (with the rank correlation test (Begg 1994), the trim and fill method (Duval 2000), or weighted regression (Egger 1997)) depending on the number of trials included in the review. One source of asymmetry is publication bias.

Data synthesis

We planned to conduct separate analyses for the four comparisons: enteral feeding versus standard care; total parenteral nutrition versus standard care; enteral versus total parenteral nutrition; and enteral versus enteral with supplemental parenteral nutrition.

We planned to calculate results using a random‐effects model.

We assessed the quality of the body of evidence using the GRADE approach. We considered the following domains: study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness, and publication bias.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

If a sufficient number of trials were included in the study, we planned to assess possible sources of heterogeneity for the primary outcome using either subgroup or sensitivity analyses, or both. We identified the following clinical subgroups: age (infants less than one year, children equal to or greater than one year old); and surgical patients (purpose of admission to PICU for postoperative care or care after trauma) versus medical patients (purpose of admission to PICU for medical illness without surgical intervention prior to admission). The subgroup for age was based on the fact that infants are at higher risk of catabolism and are generally fed more aggressively than older children. Infants may have less nutritional reserve than older children; a physiology that demonstrates rapid changes over the first year of life; and different admission diagnoses and co‐morbidities to older children; accordingly they are typically managed differently from a clinical perspective. The subgroup of surgical versus medical patients was based on inherent differences between these populations and the precedence in the literature for examining these populations separately (Heyland 1998a; Heyland 2001; Marik 2001). If a study did not provide the data or results by age, or had a different age categorization to that used in this review, we planned to contact the authors for additional data for the subgroups of interest.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to conduct the following sensitivity analyses: methodological quality of included trials; intention‐to‐treat status; and funding source (medical or pharmaceutical companies versus other). We also planned to calculate fixed‐effect model estimates as a sensitivity analysis.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

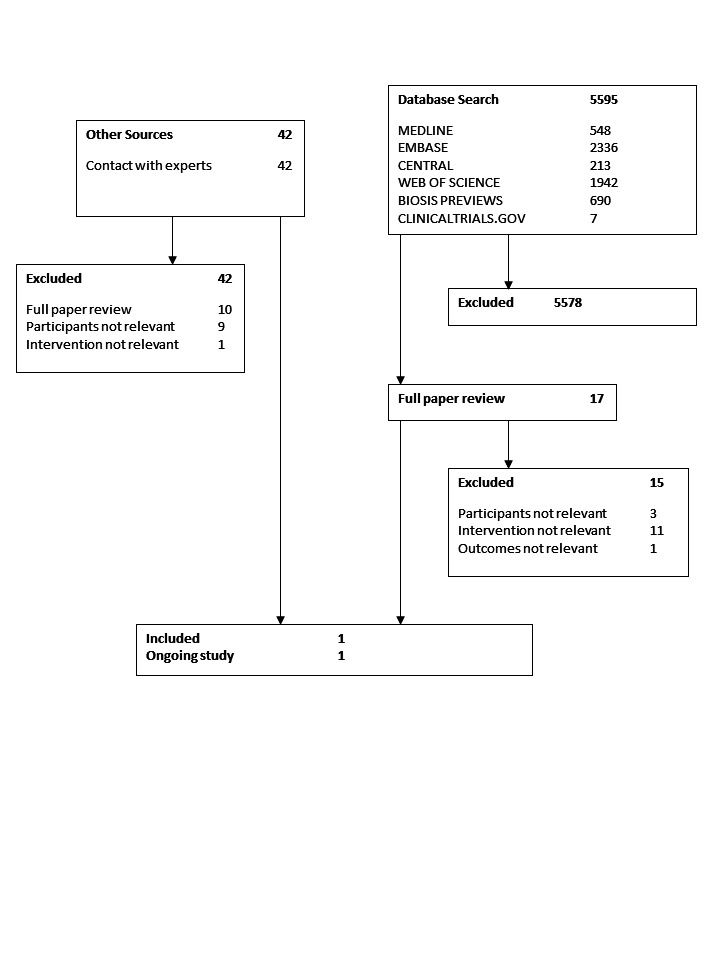

Our search identified 5595 studies. We identified an additional 42 potentially relevant studies through contacts with experts in the area. See Figure 1 for details of the search and selection process.

1.

Flow diagram of studies through the search and selection process

Included studies

We identified only one relevant trial. Seventy‐seven children in an intensive care unit because of burns involving more than 25% of their total body surface area were randomized to enteral nutrition within 24 hours or conventional care (that is no tube feeding or oral diet for at least 48 hours) (Gottschlich 2002). Children were eligible for the study if they were older than three years and were admitted within 24 hours of the injury. Five children were excluded from the study (three protocol violations, two transferred to another hospital) leaving 36 children in each group. Children were followed up for four weeks from entry into the study. The outcomes reported are detailed in the 'Characteristics of included studies' table. In our search update we identified a protocol for a relevant randomized controlled trial (Fivez 2015; ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT01536275); however, no results have yet been published.

Excluded studies

Following screening, we identified 17 studies as potentially relevant (see Figure 1). Upon closer review we excluded all but one of the studies (as well as one ongoing study), for the following reasons: different routes of delivering enteral nutrition compared (gastric versus small bowel feeding (Meert 2004); continuous versus intermittent gastric feeding (Horn 2003); immune‐enhancing formula versus standard formula (Alberda 2005; Albers 2005; Barbosa 1999; Briassoulis 2005; Briassoulis 2005b; Briassoulis 2006; Gottschlich 1990; Marin 2006; Papadopoulou 2000); two regimens of early combined enteral and parenteral nutrition compared (Alexander 1980); only surrogate nutritional markers as outcomes (Chaloupecky 1994); study population was primarily adult (Hadley 1986; Hausmann 1985; Justo Meirelles 2011; Kolacinski 1993; Peng 2001; Suchner 1996; Young 1987); study population was premature neonates or newborn infants in the neonatal intensive care unit (Black 1981; Morgan 2013); and study population was not critically ill children (that is, children not cared for in a PICU) (Khorasani 2010; Marín 1999; Pillo‐Blocka 2004). See 'Characteristics of excluded studies'.

Studies awaiting classification

There are no studies awaiting classification.

Ongoing studies

One ongoing study fitted our inclusion criteria (Fivez 2015). It is a protocol for a relevant randomized controlled trial; and no results have yet been published (see Characteristics of ongoing studies) .

Risk of bias in included studies

Overall, the risk of bias of the one relevant study was unclear, based on the Cochrane 'Risk of Bias' tool. This judgement is a result of unclear ratings for allocation concealment. We assessed all other domains as low risk of bias.

Allocation

We assessed the study as low risk of bias for random sequence generation and as unclear risk of bias for allocation concealment (not described).

Blinding

We assessed the study as unclear risk of bias for blinding.

Incomplete outcome data

We assessed the study as low risk of bias for incomplete outcome data.

Selective reporting

We assessed the study as low risk of bias for selective outcome reporting.

Other potential sources of bias

The authors described their funding source, which was not related to industry.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Feeding started at a mean of 15.6 hours (standard error (SE) 1) in the early intervention group compared to 48.5 hours (SE 0.4) in the control group. The study groups showed no statistically significant differences in the following outcomes: mortality (early, n = 4 (11%) versus control, n = 3 (8%); P value = 0.99); sepsis (early, n = 17 (47%) versus control, n = 21 (58%); P value = 0.23); ventilator days (early, mean 24.5 days (SE 4.6) versus control, mean 22.5 days (SE 4.2); P value = 0.75); hospital length of stay (early, mean 54.8 days (SE 5.9) versus control, mean 54.8 days (SE 4.6); P value = 0.96); and unexpected adverse events (early, 8 (22%) versus control, 3 (8%); P value = 0.19). Furthermore, there were no differences between groups in weekly measurements of resting energy expenditure, nitrogen balance, level of pre‐albumin, or albumin. We considered the quality of the evidence to be very low due to imprecise effects (only one small study), and the inability to assess consistency or publication bias.

Discussion

Nutritional support in children in the paediatric intensive care unit is considered important by most intensivists (van der Kuip 2004). Nevertheless, there are limited data on which to base optimal practice for nutritional support during the first week of critical illness in these children. Although it seems almost intuitively obvious that nutritional support early during critical illness would be of benefit, this has not been demonstrated in adults or children (Way 2007).

There are reasons to question the dogma that nutritional support during the first week of critical illness is a priority. For example, metabolism and mitochondrial function are altered during critical illness (Fink 2001; Mizock 1984); calorie restriction has been beneficial in animal models of critical illness (Alexander 1989), and possibly in adults with critical illness (Ash 2005; Krishnan 2003); overfeeding is associated with adverse effects (Chwals 1994; Zaloga 1994); many trials in adults have given unclear evidence of benefit from early nutritional support in critical illness (Koretz 2007a; Koretz 2007; Koretz 2007b); and surrogate nutritional outcomes may not be adequate to confirm a benefit from nutritional support in terms of meaningful clinical outcomes (Heyland 1998b; Koretz 2005). Further, it has been found that in early critical illness children do not experience hypermetabolism (Framson 2007), and energy expenditure is close to or below calculated basal metabolic rate (Briassoulis 2000; Jacsik 2001; Martinez 2004; Oosterveld 2006; White 2000). Protein catabolism during this time cannot be averted by aggressive nutritional support, and anabolism with growth cannot be induced (Chwals 1994; Shew 1999).

Therefore, we conducted this systematic review of the evidence for nutritional support during the first week of critical illness in children. With our exhaustive search strategy we found only one small, randomized controlled trial that met our criteria (Gottschlich 2002). This trial evaluated early enteral feeding (that is, within 24 hours of injury) versus conventional feeding (that is, feeding withheld for at least 48 hours) among children with burns over 25% of their body surface area. The study found no differences between groups in clinically important outcomes including infection, length of stay, and mortality. We considered the quality of the evidence based on GRADE to be very low.

We found eight trials of an immune‐enhancing formula versus a standard formula for feeding critically ill children, which did not show consistent benefit in terms of clinically important outcomes. This was, however, not a systematic review of immune‐enhancing formulae in critically ill children. It would be of interest to conduct a systematic review of immune‐enhancing formulae in paediatric critical illness. The immune‐enhancing components may best be considered as pharmacological interventions, rather than nutritional support, in which case they should be studied separately from the need for nutritional support (Heyland 2006). One trial of gastric versus small bowel feeding found that more calories were provided in the small bowel‐fed group, with trends toward increased mortality, ventilator days, intensive care unit days, and hospital days in the small bowel‐fed group (Meert 2004).

Randomized controlled trials are needed to help guide optimal nutritional support of critically ill children during the first week of critical illness. We found little evidence to support or refute the suggested need for nutritional support in these children. While more research is needed, there are a number of challenges that researchers face in this area. These include the small number of children available for study, fewer funding opportunities for non‐pharmacological nutritional interventions, and ethical concerns related to experimental protocols among this critically ill population. Further, methodological challenges exist, including the difficulty of blinding due to the nature of the intervention, heterogeneity of the patient population (comorbidities, admission diagnosis, age), and the large sample size required to show a change because of the low mortality rate in paediatric intensive care. Nevertheless, future multicentre trials are urgently needed. These must ensure methodological rigour by examining potential risks for bias at the design stage (for example, in blinding outcome assessors or using objective outcomes, such as organ dysfunction scores, that are less prone to biased assessments or reporting). Our search update found a protocol for an international, multicenter randomized controlled trial comparing "early versus late initiation of parenteral nutrition when enteral nutrition fails to reach preset caloric targets in critically ill children" (Fivez 2015). No results are yet available; these will be added to future updates of this review.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

We identified only one small randomized controlled trial. This review does not provide evidence for or against the need for nutritional support in children during the first week of critical illness; nor does it provide evidence for or against an optimal route of nutritional support in children during the first week of critical illness. Further evidence from randomized controlled trials is needed to support statements regarding the importance or lack of importance of early nutritional support in critically ill children.

Implications for research.

Research is needed to guide nutritional support in critically ill children (excluding premature or low birth weight neonates). We suggest that randomized trials of nutritional support in critically ill children during the first week of critical illness should include a control arm in which no nutritional support is administered or hypocaloric goals (below basal metabolic rate) for nutritional support are used. One multi‐center, international randomized controlled trial is ongoing.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 12 December 2018 | Amended | Editorial team changed to Cochrane Emergency and Critical Care |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 1, 2005 Review first published: Issue 2, 2009

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 3 February 2016 | New search has been performed | We ran the search in February 2016. We identified an additional 2525 citations. One ongoing study fitted our inclusion criteria (Fivez 2015). It is a protocol for a relevant randomized controlled trial; and no results have yet been published. |

| 3 February 2016 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | No new studies were included in the review. |

| 11 December 2007 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Karen Hovhannisyan (former TSC, Cochrane Anaesthesia, Critical and Emergency Care Group (ACE)) and Ann Møller (Co‐ordinating Editor ACE) for their help with the updated review.

We would like to thank John Carlisle (content editor), Alison Avenell, Reinout Mildner, Diane Yorke (peer reviewers), and Ann E. Fonfa (Cochrane Consumer Network) for their help and editorial advice during the preparation of the original review (Joffe 2009).

We would like to thank John Carlisle, Alison Avenell, Leo Celi, and Ann Møller for their help and editorial advice during the preparation of the protocol (Joffe 2005) for the review. We would also like to thank Ellen Crumley for contributions to the protocol and initial searches and Iveta Simera for translation of a study written in Czechoslovakian.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategies

Ovid MEDLINE(R)

1 ((artificial* or enteric* or naso‐gastric* or nasogastric* or nose* or tube* or ng or intravenous* or iv* or parenteral* or enteral* or jejunal* or naso‐jejunal* or nasojejunal*) adj5 (nutrition* or feed* or food* or refeed* or re‐feed* or refed* or re‐fed* or fasting or fasts or immunonutrition* or immuno‐nutrition* or diet* or hyperalimentation* or alimentation* or fluid* or liquid*)).mp. or tpn.ti,ab. or food intake/ or infant nutrition/ or child nutrition/ or diet/ or exp parenteral nutrition, total/ or intravenous feeding/ or feeding methods/

2 (picu or icu or ((critical* or intensive*) adj5 (care* or ill*))).mp. or exp intensive care units, pediatric/

3 child/ or infant/ or adolescence/ or exp infant, newborn/ or exp child, preschool/ or (pediatric or paediatric).tw. or (child* or newborn* or adolescen* or infan*).tw. or preschool*.tw. or teen*.tw. or kindergarten*.tw. or elementary school*.tw. or nursery school*.tw. or youth*.tw. or (baby* or babies*).tw. or schoolchild*.tw. or toddler*.tw.

4 1 and 2 and 3

5 ("neonatal intensive care" or "very low birth weight" or (preterm or prematur*)).ti.

6 4 not 5

7 ((randomized controlled trial or controlled clinical trial).pt. or randomized.ab. or placebo.ab. or drug therapy.fs. or randomly.ab. or trial.ab. or groups.ab.) not (animals not (humans and animals)).sh.

8 6 and 7

EMBASE (Ovid SP)

1 ((artificial* or enteric* or naso‐gastric* or nasogastric* or nose* or tube* or ng or intravenous* or iv* or parenteral* or enteral* or jejunal* or naso‐jejunal* or nasojejunal*) adj5 (nutrition* or feed* or food* or refeed* or re‐feed* or refed* or re‐fed* or fasting or fasts or immunonutrition* or immuno‐nutrition* or diet* or hyperalimentation* or alimentation* or fluid* or liquid*)).mp. or tpn.ti,ab. or food intake/ or infant nutrition/ or child nutrition/ or diet/ or exp total parenteral nutrition/ or intravenous feeding/

2 (picu or icu or ((critical* or intensive*) adj5 (care* or ill*))).mp. or exp intensive care units, pediatric/

3 child/ or infant/ or adolescence/ or exp newborn/ or exp preschool child/ or (pediatric or paediatric).tw. or (child* or newborn* or adolescen* or infan*).tw. or preschool*.tw. or teen*.tw. or kindergarten*.tw. or elementary school*.tw. or nursery school*.tw. or youth*.tw. or (baby* or babies*).tw. or schoolchild*.tw. or toddler*.tw.

4 1 and 2 and 3

5 ("neonatal intensive care" or "very low birth weight" or (preterm or prematur*)).ti.

6 4 not 5

7 (randomized‐controlled‐trial/ or randomization/ or controlled‐study/ or multicenter‐study/ or phase‐3‐clinical‐trial/ or phase‐4‐clinical‐trial/ or double‐blind‐procedure/ or single‐blind‐procedure/ or (random* or cross?over* or factorial* or placebo* or volunteer* or ((singl* or doubl* or trebl* or tripl*) adj3 (blind* or mask*))).ti,ab.) not (animals not (humans and animals)).sh.

8 6 and 7

EBM Reviews ‐ Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, ACP Journal Club, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects <Issue 4, 2006>

Date searched: 13 February 2007

# 1. ((artificial$ or enteric$ or naso‐gastric$ or nasogastric$ or nose$ or tube$ or ng or intravenous$ or iv$ or parenteral$ or enteral$ or jejunal$ or naso‐jejunal$ or nasojejunal$) adj5 (nutrition$ or feed$ or food$ or refeed$ or re‐feed$ or refed$ or re‐fed$ or fasting or fasts or immunonutrition$ or immuno‐nutrition$ or diet$ or hyperalimentation$ or alimentation$ or fluid$ or liquid$)).mp.

#2. tpn.ti,ab.

#3. food intake.sh.

#4. infant nutrition.sh.

#5. child nutrition/

#6. diet.sh.

#7. parenteral nutrition, total.sh.

#8. food intake.sh.

#9. intravenous feeding.sh.

#10. feeding methods/

#11. or/1‐10

#12. (picu or icu or nicu).mp.

#13. ((critical$ or intensive$) adj5 (care$ or ill$)).mp.

#14. intensive care units, pediatric/

#15. or/12‐14

#16. and/11,15

#17. child/

#18. infant/

#19. adolescence/

#20. infant, newborn/

#21. child, preschool/

#22. or/17‐21

#23. (pediatric$ or paediatric$ or child$ or newborn$ or adolescen$ or infan$ or preschool$ or pre‐school$ or teen$ or kindergarden$ or elementary school$ or nursery school$ or youth$ or baby$ or babies$ or neonat$ or schoolchild$ or toddler$).tw.

#24. #22 or #23

#25. #16 and #24

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL)

#1 ((artificial* or enteric* or naso‐gastric* or nasogastric* or nose* or tube* or ng or intravenous* or iv* or parenteral* or enteral* or jejunal* or naso‐jejunal* or nasojejunal*) near (nutrition* or feed* or food* or refeed* or re‐feed* or refed* or re‐fed* or fasting or fasts or immunonutrition* or immuno‐nutrition* or diet* or hyperalimentation* or alimentation* or fluid* or liquid*)) or tpn:ti,ab #2 MeSH descriptor Eating explode all trees #3 MeSH descriptor Infant Food explode all trees #4 MeSH descriptor Diet, this term only #5 MeSH descriptor Parenteral Nutrition explode all trees #6 MeSH descriptor Feeding Methods explode all trees #7 (#1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6) #8 (picu or icu or ((critical* or intensive*) near (care* or ill*))) #9 MeSH descriptor Intensive Care Units, Pediatric explode all trees #10 (#8 OR #9) #11 MeSH descriptor Child explode all trees #12 MeSH descriptor Infant explode all trees #13 MeSH descriptor Adolescent explode all trees #14 MeSH descriptor Infant, Newborn explode all trees #15 MeSH descriptor Child, Preschool explode all trees #16 pediatric or paediatric or child* or newborn* or adolescen* or infan* or preschool* or teen* or kindergarten* or elementary school* or nursery school* or youth* or baby* or babies* or schoolchild* or toddler* #17 (#11 OR #12 OR #13 OR #14 OR #15 OR #16) #18 (#7 AND #10 AND #17) #19 neonatal intensive care or very low birth weight or preterm or premature* #20 (#18 AND NOT #19)

ISI Web Of Science and BIOSIS Citation IndexSM

#1 S=((critical$ or intensive$) SAME (care$ or ill$)) or TS=(PICU OR ICU OR NICU)

#2 TS=(PARENTERAL NUTRITION OR Intravenous Feeding OR Food Intake OR Child Nutrition OR Infant Nutrition OR DIET OR tpn) or TS=(naso gastric* or nasogastric* or nose* or tube* or ng or intravenous* or iv or parenteral* or enteral* or jejunal* or naso jejunal* or nasojejunal* or artificial* or enteric*) or TS=(nutrition* or feed* or food* or refeed* or re feed* or refed* or re fed* or fasting or fasts or immunonutrition* or immuno‐nutrition* or diet* or hyperalimentation* or alimentation* or fluid* or liquid*)

#3 TS=(pediatric* or paediatric* or child* or newborn* or neonat* or adolescen* or infan* or preschool* or pre‐school* or teen* or kindergarden* or elementary school* or nursery school* or youth* or baby* or babies* or schoolchild* or toddler*)

#4 #1 and #2 and #3

#5 TS=clinical trial* OR TS=research design OR TS=comparative stud* OR TS=evaluation stud* OR TS=controlled trial* OR TS=follow‐up stud* OR TS=prospective stud* OR TS=random* OR TS=placebo* OR TS=(single blind*) OR TS=(double blind*) OR TS=groups

#6 #5 AND #4

#7 TS=(neonatal intensive care or very low birth weight or preterm or prematur*)

#8 #6 not #7

TRIALS REGISTRIES

Dates of searches: 14 February 2007

Current Controlled Trials

(critical% or icu or picu) AND (nutrition% or feed% or food% or refeed% OR PN or EN or TPN) NOT adult%

Clinicaltrials.gov

("parenteral nutrition" OR "enteral nutrition" OR nutritional OR nutritionally OR feed or feeding OR feedings OR food OR refeed OR refeeding OR PN OR EN OR TPN) [TREATMENT] AND "Child" [AGE‐GROUP] AND (ICU OR picu OR critical OR "critically ill" OR serious ) [CONDITION]

MEDLINE Plus searching of Clinicaltrials.gov

parenteral nutrition [TREATMENT]

"nutritional support" [TREATMENT]

National Research Register

#1. (nutritional next support)

#2. (nutrition* or feed* or refeed* or tubefeed* or tubefed* or en or pn or tpn)

#3. (critical* or intensive or icu or picu)

#4. (#1 or #2)

#5. (#3 and #4)

#6. (enteral or parenteral)

#7. ((#1 or #6) and #3)

#8. picu

#9. ((#1 or #6) and #8)

#10. (pediatric next intensive next care)

#11. (paediatric next intensive next care)

#12. ((#10 or #11 or #8) and (#4 or #6))

Appendix 2. Inclusion form

Please assess each study with reference to the criteria below. Place a check mark beside the statement that best describes the study. A study will be excluded even if has only one 'NO' answer.

Reviewer __________________________________________

Reference number__________________________

STUDY DESIGN:

1. Was the study a randomized controlled trial? Yes [] No []

POPULATION:

2. Was the population studied children/youth (age 1 day to 18 years) that are cared for Yes [] No []

in a paediatric intensive care setting and who receive nutrition within the first seven

days of admission? [Studies that involve both paediatric and adult participants will be

included.]

INTERVENTIONS:

3. Were patients randomized during the first week of admission to receive either: Yes [] No []

a) enteral feeding versus no feeding;

b) total parenteral nutrition versus no feeding;

c) enteral versus total parenteral nutrition;

d) enteral versus enteral with supplemental parenteral nutrition.

[This review will not address other areas of paediatric nutrition, such as

Immunonutrition versus normal nutrition, or different routes of delivering

enteral nutrition.]

OUTCOMES:

4. Are data reported for one of the following outcomes: Yes [] No []

‐ 30‐day mortality or PICU mortality []

‐ length of stay in PICU []

‐ length of stay in hospital []

‐ number of days on ventilator []

‐ morbid complications, including nosocomial infections []

DECISION:

Should this study be included in this systematic review?

Yes [] (questions 1‐4 must ALL be answered 'Yes')

No [] (any of questions 1‐4 answered with 'No')

Unsure [] (will need to be reviewed and decided by consensus)

If disagreement; final consensus decision: Yes [] No []

Reason:

Appendix 3. Data extraction form

The Cochrane Anaesthesia Review Group 02.01

APPENDIX IV, DATA EXTRACTION FORM

| Study ID: | |||||||||||

| Authors: | |||||||||||

| MEDLINE Journal ID: | |||||||||||

| Year of publication: | |||||||||||

| Language: Country: | |||||||||||

| Type of study: RCT_____ CCT_____ Non‐randomized_____ | |||||||||||

| Comments on study design: | |||||||||||

| QUALITY OF CONCEALMENT OF ALLOCATION | POINTS | ||||||||||

| Allocation was not concealed (e.g. quasi‐randomized) | 0 | ||||||||||

| Allocation concealment was not stated or was unclear | 1 | ||||||||||

| Disclosure of allocation was a possibility | 2 | ||||||||||

| Allocation was concealed (e.g. numbered, sealed, opaque envelopes drawn NON consecutively) | 3 | ||||||||||

| Inclusion and exclusion criteria were not clearly defined in the text | 0 | ||||||||||

| Inclusion and exclusion criteria were clearly defined in the text | 1 | ||||||||||

| Outcomes of patients who withdrew or were excluded after allocation were NEITHER detailed separately NOR included in an intention‐to‐treat |

0 | ||||||||||

| Outcomes of patients who withdrew or were excluded after allocation were EITHER detailed separately OR included in an intention‐to‐treat analysis OR the text stated there were no withdrawals |

1 | ||||||||||

| Treatment and control groups were NOT adequately described at entry | 0 | ||||||||||

| Treatment and control groups were adequately described at entry A minimum of 4 admission details were described (e.g. age, sex, mobility, type of surgery, ASA grade, function score, mental test score) |

1 | ||||||||||

| The text stated that the care programmes other than trial options were NOT identical | 0 | ||||||||||

| The text stated that the care programmes other than trial options were identical | 1 | ||||||||||

| Outcome measures were NOT clearly defined in the text | 0 | ||||||||||

| Outcome measures were clearly defined in the text | 1 | ||||||||||

| Outcome assessors were NOT blind to the allocation of patients | 0 | ||||||||||

| Outcome assessors were blind to the allocation of patients | 1 | ||||||||||

| The timing of the measurement of the outcomes was NOT appropriate | 0 | ||||||||||

| The timing of the measurement of the outcomes was appropriate | 1 | ||||||||||

| TOTAL NUMBER OF POINTS: / 10 | |||||||||||

| METHODS: | |||||||||||

| Subject‐blinded Yes_____ No_____ Unclear_____ | |||||||||||

| Physician‐blinded Yes_____ No_____ Unclear_____ | |||||||||||

| Intention‐to‐treat analysis: Planned Yes_____ No_____ Unclear_____ Performed Yes_____ No_____ Unclear_____ N/A_____ | |||||||||||

| Method of randomization: | |||||||||||

| PARTICIPANTS: | |||||||||||

| Number of eligible participants: Number enrolled in study: | |||||||||||

| Number of males: Number of females: | |||||||||||

| Age of participants: Type of patients: surgical_____ medical_____ Specify: < 1 yr ___ >= 1 yr ___ no stratification ___ | |||||||||||

| Severity of illness: | |||||||||||

| INTERVENTION: | Intervention | Duration | |||||||||

| Study Group 1: | |||||||||||

| Study Group 2: | |||||||||||

| Study Group 3: | |||||||||||

| Study Group 4: | |||||||||||

| COMMENT ON TREATMENT: | |||||||||||

| | |||||||||||

| Withdrawals: Yes_____ No_____ Unclear_____ Indicate number by group: study group 1 _____ study group 2 _____ study group 3 _____ Indicate reasons for withdrawals: | |||||||||||

| OUTCOMES: (specify units and measures, e.g. mean, SD, SE median, range, IQR) | Study Group 1 | Study Group 2 | Study Group 3 | Study Group 4 | |||||||

| 30‐day mortality (n, %) | |||||||||||

| PICU Mortality (n, %) | |||||||||||

| LOS in PICU (days) | |||||||||||

| LOS in hospital (days) | |||||||||||

| Ventilator days (days) | |||||||||||

| Infection (n, %) | |||||||||||

| Other complications (list) | |||||||||||

| Side effects (list) | |||||||||||

|

Was a time to event analysis performed: no_____ yes_____ If yes: List outcomes: Are data available for individual cases: no _____ yes_____ | |||||||||||

| CHANGES IN PROTOCOL: | |||||||||||

| CONTACT WITH AUTHOR: | |||||||||||

| OTHER COMMENTS ON THIS STUDY: | |||||||||||

| SUBGROUPS: | |||||||||||

| Age < 1 year | Study Group 1 | Study Group2 | Study Group 3 | Study Group 4 | |||||||

| 30‐day mortality (n, %) | |||||||||||

| PICU mortality (n, %) | |||||||||||

| Age ? 1 year | Study Group 1 | Study Group 2 | Study Group 3 | Study Group 4 | |||||||

| 30‐day mortality (n, %) | |||||||||||

| PICU mortality (n, %) | |||||||||||

| Medical patients | Study Group 1 | Study Group 2 | Study Group 3 | Study Group 4 | |||||||

| 30‐day mortality (n, %) | |||||||||||

| PICU mortality (n, %) | |||||||||||

| Surgical patients | Study Group 1 | Study Group 2 | Study Group3 | Study Group 4 | |||||||

| 30‐day mortality (n, %) | |||||||||||

| PICU mortality (n, %) | |||||||||||

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Gottschlich 2002.

| Methods | Randomized trial using random numbers table; no blinding | |

| Participants | 77 children over a 10‐year period; inclusion criteria: greater than 3 years old; burns to greater than 25% total body surface area; admitted within 24 hours after burn | |

| Interventions | Early enteral feeding beginning within 24 hours of injury versus conventional treatment (tube feeding and oral diet withheld for at least 48 hours after injury); all children received routine clinical management based on published practices and supervised by 1 physician to ensure uniformity of care | |

| Outcomes | The following outcomes were reported weekly for 4 weeks: metabolic rate, caloric intake, anabolism indices (nitrogen balance, 3‐methylhistidine); hormone levels (insulin, glucagon, cortisol, gastrin, epinephrine, norepinephrine, dopamine, T3, T4); clinical nutrition (albumin, transferrin, pre‐albumin, retinol‐binding protein, glucose). Clinical outcome data included: incidence of sepsis and wound infection; number of patients requiring parenteral nutrition, experiencing diarrhoea, or requiring growth hormone; days on tube feed; number of diarrhoea days; days receiving antibiotics; ventilator days; number of surgeries; unexpected adverse events (bowel necrosis, acute respiratory distress syndrome, renal failure, multisystem organ failure, death); medical and wound length of stay; discharge weight Primary outcome was not specified; no sample size calculation reported |

|

| Notes | Intention‐to‐treat analysis not performed. Funding source: Shriners of North America | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Random numbers table |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No description |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | For mortality |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 5 patients excluded from analysis; reasons described (3 protocol violations, 2 transferred to another hospital). Exclusions unlikely to change the results |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All outcomes listed in the methods section appear in the results section of the published report |

| Other bias | Low risk | No risk of bias due to inappropriate influence of study sponsors or baseline imbalances |

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Alberda 2005 | Comparison: immune‐enhancing versus standard formula |

| Albers 2005 | Comparison: immune‐enhancing versus standard formula |

| Alexander 1980 | Comparison: 2 forms of early combined enteral and parenteral nutrition |

| Barbosa 1999 | Comparison: immune‐enhancing versus standard formula |

| Black 1981 | Study population: premature neonates or newborns in the neonatal intensive care unit |

| Briassoulis 2005 | Comparison: immune‐enhancing versus standard formula |

| Briassoulis 2005b | Comparison: immune‐enhancing versus standard formula |

| Briassoulis 2006 | Comparison: immune‐enhancing versus standard formula |

| Chaloupecky 1994 | Outcomes: only surrogate nutritional markers |

| Gottschlich 1990 | Comparison: immune‐enhancing versus standard formula |

| Hadley 1986 | Study population: predominantly adults |

| Hausmann 1985 | Study population: predominantly adults |

| Horn 2003 | Comparison: 2 routes of delivering enteral nutrition (continuous versus intermittent gastric feeding) |

| Justo Meirelles 2011 | Study population: predominantly adults |

| Khorasani 2010 | Study population: children not in PICU |

| Kolacinski 1993 | Study population: predominantly adults |

| Marin 2006 | Comparison: immune‐enhancing versus standard formula |

| Marín 1999 | Study population: children not in PICU |

| Meert 2004 | Comparison: 2 routes of delivering enteral nutrition (gastric versus small bowel feeding) |

| Morgan 2013 | Study population: premature neonates or newborns in the neonatal intensive care unit |

| Papadopoulou 2000 | Comparison: immune‐enhancing versus standard formula |

| Peng 2001 | Study population: predominantly adults |

| Pillo‐Blocka 2004 | Study population: children not in PICU |

| Suchner 1996 | Study population: predominantly adults |

| Young 1987 | Study population: predominantly adults |

PICU: paediatric intensive care unit

Characteristics of ongoing studies [ordered by study ID]

Fivez 2015.

| Trial name or title | The Pediatric Early versus Late Parenteral Nutrition in Intensive Care Unit (PEPaNIC) study (quoted text below is from: Fivez T et al. Trials 2015;16:202) |

| Methods | "investigator‐initiated, international, multicenter, randomized controlled trial (RCT) in three tertiary referral pediatric intensive care units (PICUs) in three countries on two continents" |

| Participants | "Critically ill children, newborn to 17 years (inclusive or exclusive depending on the local definition of a pediatric patient) old, with a STRONGkids (Nutritional risk score) score of 2 points or more and who are likely to stay in the PICU for more than 24 hours, are eligible for inclusion." |

| Interventions | "This study compares early versus late initiation of PN [parenteral nutrition] when EN [enteral nutrition] fails to reach preset caloric targets in critically ill children. In the early‐PN (control, standard of care) group, PN comprising glucose, lipids and amino acids is administered within the first days to reach the caloric target. In the late‐PN (intervention) group, PN completing EN is only initiated beyond PICU‐day 7, when EN fails. For both study groups, an early EN protocol is applied and micronutrients are administered intravenously." |

| Outcomes | "The primary assessor‐blinded outcome measures are the incidence of new infections during PICU‐stay and the duration of intensive care dependency." |

| Starting date | "The study was initiated as planned on 18 June 2012." |

| Contact information | Senior author: Greet Van den Berghe: greet.vandenberghe@med.kuleuven.be |

| Notes | "At the time of the safety interim analyses (after 480 and 750 study patients discharged from PICU), the DSMB advised the continuation of the trial and ratified the initial sample size of 1,440 patients as adequate to test the hypothesis. On 1 December 2014, 1,130 patients have been included into the PEPaNIC trial. Recruitment of the last patient is expected for October 2015." |

Differences between protocol and review

Background updated (Joffe 2009).

Contributions of authors

Conceiving the review: Ari Joffe (AJ)

Co‐ordinating the review: AJ, Lisa Hartling (LH)

Undertaking manual searches: AJ

Screening search results: AJ, Natalie Anton (NA)

Organizing retrieval of papers: Lisa Tjosvold (LT; for original review), AJ

Screening retrieved papers against inclusion criteria: AJ, NA

Appraising quality of papers: LH, NA

Abstracting data from papers: AJ, LH, NA

Writing the review: AJ, NA, LH, Ben Vandermeer (BV), Laurance Lequier (LL), Bodil Larsen (BL)

Guarantor for the review (one author): AJ

Person responsible for reading and checking review before submission: AJ, LH

Sources of support

Internal sources

Alberta Research Centre for Child Health Evidence (ARCHE), University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada.

External sources

Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research, Canada.

Declarations of interest

Ari Joffe: none known

Natalie Anton: none known

Laurance Lequier: none known

Ben Vandermeer: none known

Lisa Tjosvold: none known

Bodil Larsen: none known

Lisa Hartling: none known

Edited (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

Gottschlich 2002 {published data only}

- Gottschlich MM, Jenkins ME, Mayes T, Khoury J, Kagan RJ, Warden GD. An evaluation of the safety of early vs delayed enteral support and effects on clinical, nutritional, and endocrine outcomes after severe burns. Journal of Burn Care & Rehabilitation 2002;23(6):401‐15. [PUBMED: 12432317 ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Alberda 2005 {published data only}

- Alberda C, Gramlich L, Field C, McCargar L, Meddings J, Madsen K. Effects of probiotic therapy in critically ill patients: a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study [abstract]. Gastroenterology 2005;128 Suppl 2(4):281‐2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Albers 2005 {published data only}

- Albers MJ, Steyerberg EW, Hazebroek FW, Mourik M, Borsboom GJ, et al. Glutamine supplementation of parenteral nutrition does not improve intestinal permeability, nitrogen balance, or outcome in newborns and infants undergoing digestive‐tract surgery: results from a double‐blind, randomized, controlled trial. Annals of Surgery 2005;241(4):599‐606. [PUBMED: 15798461 ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Alexander 1980 {published data only}

- Alexander JW, Macmillan BG, Stinnett JD, Ogle C, Bozian RC, Fischer JE, et al. Beneficial effects of aggressive protein feeding in severely burned children. Annals of Surgery 1980;192:505‐16. [PUBMED: 7425697 ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Barbosa 1999 {published data only}

- Barbosa E, Moreira EA, Goes JE, Faintuch J. Pilot study with a glutamine‐supplemented enteral formula in critically ill infants. Revista do Hospital das Clínicas 1999;54(1):21‐4. [PUBMED: 10488597] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Black 1981 {published data only}

- Black DD, Suttle EA, Whitington PF, Whitington GL, Korones SD. The effect of short‐term total parenteral nutrition on hepatic function in the human neonate: a prospective randomized study demonstrating alteration of hepatic canalicular function. Journal of Pediatrics 1981;99:445‐9. [PUBMED: 6115001] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Briassoulis 2005 {published data only}

- Briassoulis G, Filippou O, Hatzi E, Papassotiriou I, Hatzis T. Early enteral administration of immunonutrition in critically ill children: results of a blinded randomized controlled clinical trial. Nutrition 2005;21(7‐8):799‐807. [PUBMED: 15975487] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Briassoulis 2005b {published data only}

- Briassoulis G, Filippou O, Kanariou M, Hatzis T. Comparative effects of early randomized immune or non‐immune‐enhancing enteral nutrition on cytokine production in children with septic shock. Intensive Care Medicine 2005;31(6):851‐8. [PUBMED: 15834703 ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Briassoulis 2006 {published data only}

- Briassoulis G, Filippou O, Kanariou M, Papassotiriou I, Hatzis T. Temporal nutritional and inflammatory changes in children with severe head injury fed a regular or an immune‐enhancing diet: a randomized, controlled trial. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine 2006;7(1):56‐62. [PUBMED: 16395076 ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Chaloupecky 1994 {published data only}

- Chaloupecky V, Vislocky I, Pachl J, Sprongl L, Svomova V. The effect of early parenteral nutrition on amino acid and protein metabolism in infants following congenital heart disease surgery in extracorporeal circulation. Cor et Vasa 1994;36:26‐34. [Google Scholar]

Gottschlich 1990 {published data only}

- Gottschlich MM, Jenkins M, Warden GD, Baumer T, Havens P, Snook JT, et al. Differential effects of three enteral dietary regimens on selected outcome variables in burn patients. JPEN. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition 1990;14(3):225‐36. [PUBMED: 2112634 ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hadley 1986 {published data only}

- Hadley MN, Grahm TW, Harrington T, Schiller WR, McDermott MK, Posillico DB. Nutritional support and neurotrauma: a critical review of early nutrition in forty five acute head injury patients. Neurosurgery 1986;19:367‐73. [PUBMED: 3093915 ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hausmann 1985 {published data only}

- Hausmann D, Mosebach KO, Caspari R, Rommelsheim K. Combined enteral‐parenteral nutrition versus total parenteral nutrition in brain‐injured patients. Intensive Care Medicine 1985;11:80‐4. [PUBMED: 3921583] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Horn 2003 {published data only}

- Horn D, Chaboyer W. Gastric feeding in critically ill children: a randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Critical Care 2003;12(5):461‐8. [PUBMED: 14503430 ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Justo Meirelles 2011 {published data only}

- Justo Meirelles CM, Aguilar‐Mascimento JE. Enteral or parenteral nutrition in traumatic brain injury: a prospective randomized trial. Nutricion Hospitalana 2011;26:1120‐4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Khorasani 2010 {published data only}

- Khorasani EN, Mansouri F. Effect of early enteral nutrition on morbidity and mortality in children with burns. Burns 2010;36:1067‐71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kolacinski 1993 {published data only}

- Kolacinski Z. Early parenteral nutrition in patients unconscious because of acute drug poisoning. JPEN. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition 1993;17:25‐9. [PUBMED: 8437319] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Marín 1999 {published data only}

- Marín VB, Rebollo MG, Castillo‐Duran CD, López MT, Sanabria MS, Morage FM, et al. Controlled study of early postoperative parenteral nutrition in children. Journal of Pediatric Surgery 1999;34:1330‐5. [PUBMED: 10507423] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Marin 2006 {published data only}

- Marin VB, Rodriguez‐Osiac L, Schlessinger L, Villegas J, Lopez M, Castillo‐Duran C. Controlled study of enteral arginine supplementation in burned children: impact on immunologic and metabolic status. Nutrition 2006;22(7‐8):705‐12. [PUBMED: 16815485 ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Meert 2004 {published data only}

- Meert KL, Daphtary KM, Metheny NA. Gastric vs small‐bowel feeding in critically ill children receiving mechanical ventilation: a randomized controlled trial. Chest 2004;126(3):872‐8. [PUBMED: 15364769] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Morgan 2013 {published data only}

- Morgan J, Bombell S, McGuire W. Early trophic feeding versus enteral fasting for very preterm or very low birth weight infants. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2013, Issue 3. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000504.pub4] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Papadopoulou 2000 {published data only}

- Papadopoulou A, Papazoglou K, Tsoutsou A, Papadatos J. Prospective, randomised trial on the efficacy of glutamine‐ versus placebo‐enriched peptide based feeds in critically ill children. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition 2000;31 Suppl 2:209‐10. [Google Scholar]

Peng 2001 {published data only}

- Peng YZ, Yuan ZQ, Xiao GX. Effects of early enteral feeding on the prevention of enterogenic infection in severely burned patients. Burns 2001;27:145‐9. [PUBMED: 11226652 ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Pillo‐Blocka 2004 {published data only}

- Pillo‐Blocka F, Adatia I, Sharieff W, McCrindle BW, Zlotkin S. Rapid advancement to more concentrated formula in infants after surgery for congenital heart disease reduces duration of hospital stay: a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Pediatrics 2004;145(6):761‐6. [PUBMED: 15580197 ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Suchner 1996 {published data only}

- Suchner U, Senftleben U, Eckart T, Scholz MR, Beck K, Murr R, et al. Enteral versus parenteral nutrition: effects on gastrointestinal function and metabolism. Nutrition 1996;12:12‐22. [PUBMED: 8838831] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Young 1987 {published data only}

- Young B, Ott L, Twyman D, Norton J, Rapp R, Tibbs P, et al. The effect of nutritional support on outcome from severe head injury. Journal of Neurosurgery 1987;67:668‐76. [PUBMED: 3117982] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to ongoing studies

Fivez 2015 {published data only}

- The Pediatric Early versus Late Parenteral Nutrition in Intensive Care Unit (PEPaNIC) study (quoted text below is from: Fivez T et al. Trials 2015;16:202). Ongoing study "The study was initiated as planned on 18 June 2012.".

Additional references

Alexander 1989

- Alexander JW, Gonce SJ, Miskell PW, Peck MD, Sax H. A new model for studying nutrition in peritonitis: the adverse effect of overfeeding. Annals of Surgery 1989;209(3):334‐40. [PUBMED: 2493777] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ash 2005

- Ash JL, Gervasio JM, Zaloga GP, Rodman GH. Does the quantity of enteral nutrition affect outcomes in critically ill trauma patients. Nutrition in Clinical Practice 2005;29 Suppl(1):10‐1. [Google Scholar]

ASPEN 2002

- ASPEN Board of directors and the clinical guidelines task force. Guidelines for the use of parenteral and enteral nutrition in adult and pediatric patients. JPEN. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition 2002;26 Suppl:1‐138SA. [PUBMED: 11841046 ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Avitzur 2003

- Avitzur Y, Singer P, Dagan O, Kozer E, Abramovitch D, Dinari G, et al. Resting energy expenditure in children with cyanotic and noncyanotic congential heart disease before and after open heart surgery. JPEN. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition 2003;27:47‐51. [PUBMED: 12549598] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Begg 1994

- Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics 1994;50:1088‐101. [PUBMED: 7786990] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Boitano 2006

- Boitano M. Hypocaloric feeding of the critically ill. Nutrition in Clinical Practice 2006;21:617‐22. [PUBMED: 17119168] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bordone 2005

- BordoneL, Guarente L. Calorie restriction, SIRT1, and metabolism: understanding longevity. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 2005;6:298‐305. [PUBMED: 15768047] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Briassoulis 2000

- Briassoulis G, Venkataraman S, Thompson AE. Energy expenditure in critically ill children. Critical Care Medicine 2000;28:1166‐72. [PUBMED: 10809300] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Briassoulis 2001

- Briassoulis G, Zavras N, Hatzis T. Malnutrition, nutritional indices, and early enteral feeding in critically ill children. Nutrition 2001;17:548‐57. [PUBMED: 11448572] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Chwals 1994

- Chwals WJ. Overfeeding the critically ill child: fact or fantasy?. New Horizons 1994;2:147‐55. [PUBMED: 7922439] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Dhaliwal 2004

- Dhaliwal R, Jurewitsch B, Harrietha D, Heyland DK. Combination enteral and parenteral nutrition in critically ill patients: harmful or beneficial? A systematic review of the evidence. Intensive Care Medicine 2004;30:1666‐71. [PUBMED: 15185069] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Dickerson 2002

- Dickerson RN, Boschert KJ, Kudsk KA, Brown RO. Hypocaloric enteral tube feeding in critically ill obese patients. Nutrition 2002;18:241‐6. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Duval 2000

- Duval S, Tweedie R. Trim and fill: A simple funnel‐plot‐based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta‐analysis. Biometrics 2000;56:455‐63. [PUBMED: 10877304] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Egger 1997

- Egger M, Davey Smith GD, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta‐analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997;315:629‐34. [PUBMED: 9310563] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Fink 2001

- Fink MP. Cytopathic hypoxia: Mitochondrial dysfunction as mechanism contributing to organ dysfunction in sepsis. Critical Care Clinics 2001;17:219‐37. [PUBMED: 11219231] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Framson 2007

- Framson CM, LeLeiko NS, Dallal GE, Roubenoff R, Snelling LK, Dwyer JT. Energy expenditure in critically ill children. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine 2007;8:264‐7. [PUBMED: 17417117] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gramlich 2004

- Gramlich L, Kichian K, Pinilla J, Rodych NJ, Dhaliwal R, Heyland DK. Does enteral nutrition compared to parenteral nutrition result in better outcomes in critically ill adult patients? A systematic review of the literature. Nutrition 2004;20:843‐8. [PUBMED: 15474870] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hart 2002

- Hart DW, Wolf SE, Herndon DN, Chinkes DL, Lal SO, Obeng MK, et al. Energy expenditure and caloric balance after burn: increased feeding leads to fat rather than lean mass accretion. Annals of Surgery 2002;235(1):152‐61. [PUBMED: 11753055] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Heyland 1998a

- Heyland DK, MacDonald S, Keefe L, Drover JW. Total parenteral nutrition in the critically ill patient: a meta‐analysis. JAMA 1998;280:2013‐9. [PUBMED: 9863853] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Heyland 1998b

- Heyland DK. Nutritional support in the critically ill patient: a critical review of the evidence. Critical Care Clinics 1998;14(3):423‐40. [PUBMED: 9700440] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Heyland 2001

- Heyland DK, Novak F, Drover JW, Jain M, Su X, Suchner U. Should immunonutrition become routine in critically ill patients? A systematic review of the evidence. JAMA 2001;286(8):944‐53. [PUBMED: 11509059] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Heyland 2003

- Heyland DK, Dhaliwal R, Drover JW, Gramlich L, Dodek P. Canadian clinical practice guidelines for nutrition support in mechanically ventilated, critically ill adult patients. JPEN. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition 2003;27(5):355‐73. [PUBMED: 12971736 ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Heyland 2006

- Heyland DK, Dhaliwal R. Oxidative stress in the critically ill: a preliminary look at the REDOXS study. Critical Care Rounds 2006;7(1):1‐7. [Google Scholar]

Higgins 2002

- Higgins JPT, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta‐analysis. Statistics in Medicine 2002;21(11):1538‐58. [PUBMED: 12111919] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Jacsik 2001

- Jacsik T, Shew SB, Keshen TH, Dzakovic A, Jahoor F. Do critically ill surgical neonates have increased energy expenditure?. Journal of Pediatric Surgery 2001;36(1):63‐7. [PUBMED: 11150439 ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Jeejeebhoy 2004

- Jeejeebhoy KN. Permissive underfeeding of the critically ill patient. Nutrition in Clinical Practice 2004;19:477‐80. [PUBMED: 16215142 ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Joffe 2001

- Joffe AR. Critical care medicine: major changes in dogma of the past decade. Journal of Intensive Care Medicine 2001;16:177‐92. [Google Scholar]

Klein 1997

- Klein S, Kinney J, Jeejeebhoy K, Alpers D, Hellerstein M, Murray M, et al. Nutrition support in clinical practice: review of published data and recommendations for future research directions. Summary of a conference sponsored by the National Institutes of Health, American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, and American Society for Clinical Nutrition. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 1997;66(3):683‐706. [PUBMED: 9280194] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Koretz 2005

- Koretz RL. Nutrition society symposium on 'end points in clinical nutrition trials': death, morbidity and economics are the only end points for trials. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society 2005;64:277‐84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Koretz 2007

- Koretz RL. Do data support nutrition support? Part II. Enteral artificial nutrition. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 2007;107:1374‐80. [PUBMED: 17659905 ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Koretz 2007a

- Koretz RL, Avenell A, Lipman TO, Braunschweig CL, Milne AC. Does enteral nutrition affect clinical outcome? A systematic review of the randomized trials. American Journal of Gastroenterology 2007;102:412‐29. [PUBMED: 17311654 [] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Koretz 2007b

- Koretz RL. Do data support nutrition support? Part I: Intravenous nutrition. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 2007;107:988‐96. [PUBMED: 17524720 ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Krishnan 2003

- Krishnan JA, Parce PB, Martinez A, Diette GB, Brower RG. Caloric intake in medical ICU patients: consistency of care with guidelines and relationship to clinical outcomes. Chest 2003;124:297‐305. [PUBMED: 12853537 ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Letton 1995

- Letton RW, Chwals WJ, Jamie A, Charles B. Early postoperative alterations in infant energy use increase the risk of overfeeding. Journal of Pediatric Surgery 1995;30(7):988‐93. [PUBMED: 7472959] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Marik 2001

- Marik PE, Zaloga GP. Early enteral nutrition in acutely ill patients: a systematic review. Critical Care Medicine 2001;29(12):2264‐70. [PUBMED: 11801821 ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Martinez 2004