Abstract

Background

Glutamine is a non‐essential amino acid which is abundant in the healthy human body. There are studies reporting that plasma glutamine levels are reduced in patients with critical illness or following major surgery, suggesting that glutamine may be a conditionally essential amino acid in situations of extreme stress. In the past decade, several clinical trials examining the effects of glutamine supplementation in patients with critical illness or receiving surgery have been done, and the systematic review of this clinical evidence has suggested that glutamine supplementation may reduce infection and mortality rates in patients with critical illness. However, two recent large‐scale randomized clinical trials did not find any beneficial effects of glutamine supplementation in patients with critical illness.

Objectives

The objective of this review was to:

1. assess the effects of glutamine supplementation in critically ill adults and in adults after major surgery on infection rate, mortality and other clinically relevant outcomes;

2. investigate potential heterogeneity across different patient groups and different routes for providing nutrition.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Anaesthesia Review Group (CARG) Specialized Register; Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in The Cochrane Library (2013, Issue 5); MEDLINE (1950 to May 2013); EMBASE (1980 to May 2013) and Web of Science (1945 to May 2013).

Selection criteria

We included controlled clinical trials with random or quasi‐random allocation that examined glutamine supplementation versus no supplementation or placebo in adults with a critical illness or undergoing elective major surgery. We excluded cross‐over trials.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently extracted the relevant information from each included study using a standardized data extraction form. For infectious complications and mortality and morbidity outcomes we used risk ratio (RR) as the summary measure with the 95% confidence interval (CI). We calculated, where appropriate, the number needed to treat to benefit (NNTB) and the number needed to treat to harm (NNTH). We presented continuous data as the difference between means (MD) with the 95% CI.

Main results

Our search identified 1999 titles, of which 53 trials (57 articles) fulfilled our inclusion criteria. The 53 included studies enrolled a total of 4671 participants with critical illness or undergoing elective major surgery. We analysed seven domains of potential risk of bias. In 10 studies the risk of bias was evaluated as low in all of the domains. Thirty‐three trials (2303 patients) provided data on nosocomial infectious complications; pooling of these data suggested that glutamine supplementation reduced the infectious complications rate in adults with critical illness or undergoing elective major surgery (RR 0.79, 95% CI 0.71 to 0.87, P < 0.00001, I² = 8%, moderate quality evidence). Thirty‐six studies reported short‐term (hospital or less than one month) mortality. The combined rate of mortality from these studies was not statistically different between the groups receiving glutamine supplement and those receiving no supplement (RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.78 to 1.02, P = 0.10, I² = 22%, low quality evidence). Eleven studies reported long‐term (more than six months) mortality; meta‐analysis of these studies (2277 participants) yielded a RR of 1.00 (95% CI 0.89 to 1.12, P = 0.94, I² = 30%, moderate quality evidence). Subgroup analysis of infectious complications and mortality outcomes did not find any statistically significant differences between the predefined groups. Hospital length of stay was reported in 36 studies. We found that the length of hospital stay was shorter in the intervention group than in the control group (MD ‐3.46 days, 95% CI ‐4.61 to ‐2.32, P < 0.0001, I² = 63%, low quality evidence). Slightly prolonged intensive care unit (ICU) stay was found in the glutamine supplemented group from 22 studies (2285 participants) (MD 0.18 days, 95% CI 0.07 to 0.29, P = 0.002, I² = 11%, moderate quality evidence). Days on mechanical ventilation (14 studies, 1297 participants) was found to be slightly shorter in the intervention group than in the control group (MD ‐ 0.69 days, 95% CI ‐1.37 to ‐0.02, P = 0.04, I² = 18%, moderate quality evidence). There was no clear evidence of a difference between the groups for side effects and quality of life, however results were imprecise for serious adverse events and few studies reported on quality of life. Sensitivity analysis including only low risk of bias studies found that glutamine supplementation had beneficial effects in reducing the length of hospital stay (MD ‐2.9 days, 95% CI ‐5.3 to ‐0.5, P = 0.02, I² = 58%, eight studies) while there was no statistically significant difference between the groups for all of the other outcomes.

Authors' conclusions

This review found moderate evidence that glutamine supplementation reduced the infection rate and days on mechanical ventilation, and low quality evidence that glutamine supplementation reduced length of hospital stay in critically ill or surgical patients. It seems to have little or no effect on the risk of mortality and length of ICU stay, however. The effects on the risk of serious side effects were imprecise. The strength of evidence in this review was impaired by a high risk of overall bias, suspected publication bias, and moderate to substantial heterogeneity within the included studies.

Plain language summary

Giving glutamine supplements to critically ill adults

Glutamine is a non‐essential amino acid which is abundant in the healthy human body. There are studies reporting that muscle and plasma glutamine levels are reduced in patients with critical illness, or following major surgery, suggesting that the body's demand for glutamine is increased in these situations. In the past decade, several clinical trials have examined the effects of glutamine supplementation in patients with critical illness or receiving surgery, and a systematic review of this clinical evidence suggested that giving glutamine to these patients may reduce infection and mortality rates. However, two recent large‐scale clinical trials, published in 2011 and 2013, did not find any beneficial effects of glutamine supplementation in patients with critical illness.

In this review, we searched the available literature until May 2013 and included studies which compared the outcomes with glutamine supplementation and without in adults with a critical illness or undergoing elective major surgery. We included 57 articles from 53 randomized controlled studies in this review. These 53 studies enrolled a total of 4671 patients with critical illness or undergoing elective major surgery. The risk of mortality, length of intensive care unit stay and the incidence of side effects were not significantly different between those given glutamine and those who were not. However, our findings showed that the risk of infectious complications in patients who were given glutamine was 79% of the risk for those who were not. In other words, 12 patients need to be supplemented with glutamine to prevent one case of infection. This result needs to be interpreted cautiously as the quality of evidence for infectious complications was moderate. The funnel plot for this outcome suggested that smaller studies with outcomes favouring non‐supplemented patients have not been published, and further research is likely to have an impact on the estimate of effect for this outcome. The findings from this review also suggested that the average length of hospital stay in critically ill or surgical patients supplemented with glutamine was 3.46 days shorter than for patients without glutamine supplementation. This result should also be treated with care as there was substantial heterogeneity between these studies. We found in this review that the mean number of days on mechanical ventilation was 0.69 days shorter in patients with glutamine supplementation than for patients without glutamine supplementation.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Glutamine‐supplemented nutrition compared to non‐supplemented nutrition for critically ill patients.

| Glutamine‐supplemented nutrition compared to non‐supplemented nutrition for critically ill patients | ||||||

| Patient or population: critically ill patients or receiving major surgery Settings: inpatient Intervention: glutamine‐supplemented nutrition | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Glutamine‐supplemented nutrition | |||||

| Infectious complications | 399 per 1000 | 315 per 1000 (283 to 347) | RR 0.79 (0.71 to 0.87) | 2303 (33 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| Short‐term mortality (within hospital stay or closest to one month) | 197 per 1000 | 175 per 1000 (154 to 201) | RR 0.89 (0.78 to 1.02) | 3454 (36 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | |

| Long‐term mortality (closest to six month) | 328 per 1000 | 328 per 1000 (292 to 367) | RR 1 (0.89 to 1.12) | 2277 (11 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2 | |

| Length of hospital stay | The mean length of hospital stay ranged across control groups from 9 to 73 days | The mean length of hospital stay in the intervention groups was 3.46 lower (4.61 to 2.32 lower) | 2963 (36 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2,3 | ||

| Length of ICU stay | The mean length of ICU stay ranged across control groups from 0.5 to 28.38 days | The mean length of ICU stay in the intervention groups was 0.18 higher (0.07 to 0.29 higher) | 2284 (22 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2 | ||

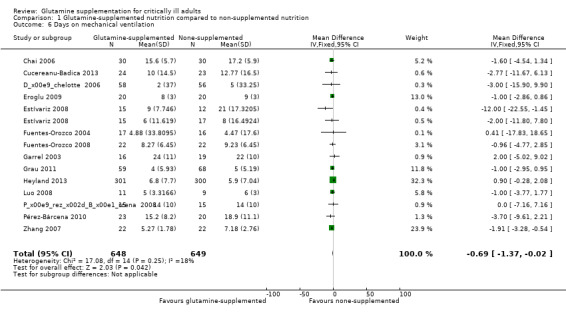

| Days on mechanical ventilation | The mean days on mechanical ventilation ranged across control groups from 4.47 to 22 days | The mean days on mechanical ventilation in the intervention groups was 0.69 lower (1.37 to 0.02 lower) | 1297 (14 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2 | ||

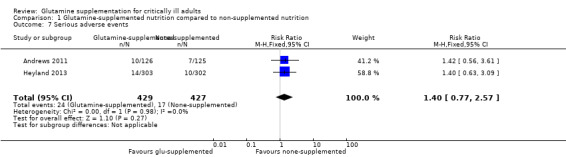

| Serious adverse events | 40 per 1000 | 56 per 1000 (31 to 103) | RR 1.4 (0.77 to 2.57) | 856 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate4 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Publication bias is suspected as the funnel plot for this outcome suggested that smaller studies with outcomes favouring non‐supplemented patients were lacking 2 The proportion of high risk of bias trials in this outcome was higher than 30%, the potential limitations are likely to reduce confidence in the estimate of effect 3 There was substantial variability in effect estimates (I² = 63%) 4 The 95% CI of the pooled estimate was not narrow enough for a confident judgment of the effect size

Background

Description of the condition

Critically ill adults can be defined as a group of patients with a life‐threatening medical or surgical status who need treatment in an intensive care unit (ICU) (Mizock 2010). They are vulnerable to nosocomial infections as severe illness may bring about immunofunctional deficiency (O'Leary 1996). In response to a severe condition the local inflammatory reaction of the body develops into systemic inflammation. Immunosuppression may be induced by the corresponding compensatory anti‐inflammatory response, which may increase the risk of infection and organ failure in critically ill patients (Mizock 2010; Tschoeke 2007). Specific nutrients for the immune system, such as glutamine, can be administered enterally or parenterally to impact favourably on the immune response and thus reduce the complications associated with critical illness (Mizock 2010; Novak 2002).

Description of the intervention

Glutamine is a type of free amino acid which is abundant in the body. It accounts for approximately 30% of the plasma free amino acids. Most glutamine in the body is synthesized by skeletal muscle, while the brain and the lung synthesize the remainder (Tjader 2007). Although glutamine is non‐essential in the diet of healthy human beings, endogenous glutamine biosynthesis may be insufficient to meet the needs of patients in situations of extreme stress (Bongers 2007). In patients undergoing surgery or suffering trauma or sepsis the levels of free glutamine in muscle are decreased (Gamrin 1996; Vinnars 1975). Plasma glutamine levels are also reduced in patients with critical illness or following major surgery (Melis 2004; Parry‐Billings 1992). Clinical evidence has revealed that glutamine supplementation in critical illness may reduce infection and mortality rates (Novak 2002).

Glutamine supplementation can be used to prevent a new infection in non‐infected patients or a subsequent infection in critically ill patients who have already had an infection. The latter situation is a far greyer area since the immune dysfunction associated with repeated infections and how these affect subsequent outcomes are far less clearly understood. In this systematic review we will focus on the effect of glutamine in preventing new infective complications in non‐infected participants (Andrews 2011).

How the intervention might work

There are many potential mechanisms which could account for the benefit of glutamine supplementation in critically ill patients. First, there is a depletion of free glutamine and a shortage in relation to needs under conditions of severe metabolic stress such that exogenous glutamine supplementation is required in order to maintain normal concentrations of plasma glutamine (Tjader 2007). Second, both in vitro and in vivo studies have suggested that glutamine could induce the expression of heat shock proteins (HSPs), especially HSP‐70 (Kim 2013). Hsp‐70 expression could protect cells against cytotoxic mediators and reduce organ injury and mortality in critical illness settings (Roth 2008). In critically ill patients it was reported that glutamine supplementation significantly increased serum HSP‐70 and the magnitude of the HSP‐70 enhancement in the glutamine group was correlated with improved clinical outcomes, further indicating that glutamine may play a protective role by inducing the expression of HSPs (Ziegler 2005). Third, clinical trials revealed that glutamine supplementation attenuated hyperglycaemia and insulin resistance in ICU patients (Bakalar 2006; Déchelotte 2006) and it seems reasonable to speculate that glutamine may exert its effects through regulating glucose metabolism in the critically ill. Fourth, glutamine supplementation in patients has been shown to maintain the gastrointestinal structure (Melis 2004), improve nitrogen balance (Hammarqvist 1989), elevate immune cell function (Ogle 1994) and reduce the production of proinflammatory cytokines (O'Riordain 1996). Fifth, glutamine is a precursor for glutathione and could play its role as an antioxidant by producing glutathione (Melis 2004).

Why it is important to do this review

Although glutamine may play an important role in the treatment of critically ill patients in some countries (such as the UK) enteral or parenteral supplementation with glutamine has not been widely adopted for patients with critical illness or those who have had surgery (Avenell 2006) due to a lack of good quality randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Also, when dealing with nutritional deficiency any effect on patient outcome is dependent on the prior and current states of nutrition and health, and the consequences of a deficiency depends on how well the patient's own endogenous system can meet that need. Some of the recently published, large sample size studies have tested the influence of glutamine supplementation given only for a few days on short‐term and long‐term outcomes (Andrews 2011; Déchelotte 2006); few have studied long‐term glutamine supplementation. Therefore, it is necessary to investigate and summarize the potential heterogeneity in the design of these studies and assess any association with their results.

Furthermore, there are differences in the use of exogenous glutamine by parenteral or enteral administration. There is controversy as to whether both total parenteral and enteral glutamine supplementation can reduce infection in patients with critical illness (Avenell 2009). Some studies have assessed the influence of risk of bias in the RCTs that have compared parenteral or enteral nutrition with no nutritional intervention in critically ill patients (Koretz 2007a; Koretz 2007b; Koretz 2007c). The results show that in the trials with lower risk of bias parenteral nutrition appeared to cause infection, and the alleged benefits of enteral nutrition may actually have been due to bias. Therefore, even if the conclusion of our review is that the addition of glutamine results in fewer infections, we will need to interpret the results cautiously. Still, the inflammatory response accompanying critical illness was far more intense and complex than the response elective surgical patients had experienced (Avenell 2009). Thus, the effects of glutamine supplementation may differ between patients undergoing surgery and patients who are critically ill. Like in the previous systematic reviews (Avenell 2009; Novak 2002) we planned to examine the treatment effects of glutamine supplementation in surgical patients and critically ill patients separately. As heterogeneity may exist between critically ill patients and surgical patients the combined results of these two populations in our review must be interpreted cautiously.

Lastly, large sample multicentre RCTs examining the role of glutamine in critical illness have recently been completed (Andrews 2011; Heyland 2013). Therefore a rigorous and objective systematic review is needed to evaluate the role of glutamine supplementation in preventing infections in critically ill adults.

Objectives

The objective of this review was to:

determine the effects of glutamine supplementation in critically ill adults and in adults after major surgery on infection rate, mortality and other clinically relevant outcomes;

investigate potential heterogeneity across different patient groups and different routes for providing nutrition.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included full reports of controlled clinical trials with random or quasi‐random allocation. We excluded cross‐over trials.

Types of participants

We included studies in adults with a critical illness or undergoing elective major surgery. We excluded participants receiving prophylactic supplementation of glutamine before surgery.

We included studies reporting mixed groups of participants (for example, combined data from critically ill and medical patients). We planned to treat these as separate groups in subgroup analyses (for example, medical, surgical, mixed).

Types of interventions

We examined glutamine supplementation delivered by the parenteral or enteral route versus no supplementation or placebo. The nutritional regime was determined by each of the included trials and the glutamine was given in addition to a standard nutritional regime.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Number of infectious complications (as defined in each of the included studies)

Mortality (measured at the follow‐up times closest to one and six months)

Secondary outcomes

Length of hospital stay

Length of ICU stay

Days on mechanical ventilation

Possible side effects, as described by the authors

Quality of life

With secondary outcomes 1, 2 and 3, for patients who died before discharge death was considered as discharge.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Anaesthesia Review Group (CARG) Specialized Register; Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in The Cochrane Library (2013, Issue 5), see Appendix 1; MEDLINE via OvidSP (1950 to May 2013), see Appendix 2; EMBASE via OvidSP (1980 to May 2013), see Appendix 3; and Web of Science (1945 to May 2013), see Appendix 4.

We used the following text words: glutam* or dipeptide* or L‐glutamin*.

We developed a specific search strategy for each database based on that developed for MEDLINE. We did not apply any language restriction.

Searching other resources

Two authors (WFX, LQY) independently handsearched the following intensive care and nutrition journals (up to April 2013) as advised by the reviewers. These are available in our library:

Clinical Nutrition;

Critical Care Medicine;

Intensive Care Medicine;

Proceedings of the Nutrition Society;

Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition;

Chest;

Journal of Orthomolecular Medicine.

Two authors (YMS, ZJL) searched the references of all identified trials and previous reviews.

One author (KMT) searched the following websites for ongoing clinical trials and unpublished studies (up to June 2013):

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two authors (KMT, XQL) independently screened the abstracts of all studies identified by the search strategy. We obtained the full texts of articles that seemed to meet our inclusion criteria and independently re‐assessed them. We resolved any disagreements by discussion until a consensus was achieved.

Data extraction and management

Two authors (KMT, XQL) independently extracted the relevant information from each included study using a standardized data extraction form. We resolved any disagreements by discussion. One author (KMT) entered data into Review Manager software (RevMan 5.2) and re‐checked the data for accuracy. If we needed further information to enable us to reach a decision then we attempted to contact the study authors.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Based on the recommendations in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Handbook 2011), two authors (LQY and ZJL) assessed the risk of bias for each included trial by using the domain‐based evaluation. We assessed the following seven domains: random sequence generation (selection bias), allocation concealment (selection bias), blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias), blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias), incomplete outcome data (attrition bias), selective reporting (reporting bias) and other bias. We also gave reasons for our judgements. Three authors (LQY, ZJL and WFY) resolved disagreements by reviewing the data together.

We judged an included trial to be a trial with low risk of bias if the risk of bias was evaluated as 'low' in all of the domains. If the risk of bias was judged as 'high', then we listed the trial as having a high risk of bias. Those trials that we judged 'unclear' were listed as having an unclear risk of bias. Using the content of the included studies and the 'risk of bias' tables, we presented the quality of the evidence using the GRADE approach, giving particular attention to the limitations of study design and heterogeneity of results.

Measures of treatment effect

For dichotomous data, we used the risk ratio (RR) as the summary measure. We calculated the number needed to treat to benefit (NNTB) and the number needed to treat to harm (NNTH) where appropriate. We presented continuous data as the difference between means. Data reported as median and range were converted into mean (standard deviation) before meta‐analysis by using the formula from Hozo 2005, and the estimated standard deviation was calculated from the interquartile range based on the assumption that the width of the interquartile range will be approximately 1.35 standard deviations (Handbook 2011).

Unit of analysis issues

The unit of analysis was the participating adult in individually randomized trials.

Dealing with missing data

We contacted the authors of the included trials to obtain relevant missing data. If data were obtained from the trial authors, then we performed an intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis. We investigated attrition, for example from dropouts, losses to follow‐up and withdrawals. We critically appraised issues of missing data according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Handbook 2011).

Assessment of heterogeneity

We identified heterogeneity by visual inspection of the forest plots and by using a standard Chi2 test with a significance level of α = 0.1. We also specifically examined heterogeneity with the I2 statistic, quantifying inconsistency across studies to assess the impact of heterogeneity on the meta‐analysis, where an I2 statistic of 50% and more indicates a substantial level of inconsistency (Handbook 2011). When statistical heterogeneity was found, we attempted to determine the potential reasons for it by examining the individual trials and the subgroup characteristics.

We assessed the statistical heterogeneity of any included studies that were assessed as having clinical diversity (for example, different types of patients, enteral or parenteral glutamine supplementation) and methodological diversity.

Assessment of reporting biases

We tried to minimize the impact of publication bias through a thorough review of all the published data. As the review included more than 10 studies, we assessed publication bias and small study effects in a qualitative manner using a funnel plot. If significant asymmetry was found in the funnel plot, we reported it in our results and in the summary of findings table.

Data synthesis

On the basis that no substantial clinical heterogeneity was found between trials, we performed the analysis using RevMan software (RevMan 5.2). We performed meta‐analysis of the included trials by using a fixed‐effect model if the P value of the heterogeneity test was more than 0.1, otherwise we used a random effects model. We expressed dichotomous data as the risk ratio (RR) with the 95% confidence interval (CI). We calculated the NNTB for the infectious complications outcome by combining the overall RR with an estimate of the prevalence of the event in the control groups of the trials. We analysed continuous outcomes according to the difference in the mean treatment effects and the 95% CI. We assumed a P value of < 0.05 to be of statistical significance.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

As the treatment effect of glutamine supplementation may be different in surgical patients compared with critically ill patients, and it may also be affected by different routes of administration and different disease status, we performed subgroup analysis for the primary outcomes by:

elective surgical patients and critically ill patients,

enteral glutamine supplementation only and parenteral glutamine supplementation only,

patients with malignant and non‐malignant disease.

Sensitivity analysis

We performed sensitivity analysis for trials with a low risk of bias, for all the outcomes. We compared random‐effects and fixed‐effect estimates for each outcome variable. In the case of any missing data, we planned to use the best case, worst case for imputation of missing data. We excluded and included any study that appeared to have a large effect size (often the largest or earliest study) in order to assess its impact on the meta‐analysis.

Summary of findings

We used the principles of the GRADE system (Guyatt 2008) to assess the quality of the body of evidence associated with the following specific outcomes in our review:

number of infectious complications;

mortality (mortality closest to at one and six months);

length of hospital stay;

length of ICU stay;

days on mechanical ventilation;

serious adverse events.

We constructed a 'summary of findings' (SoF) table using the GRADE software. The GRADE approach appraises the quality of a body of evidence based on the extent to which one can be confident that an estimate of effect or association reflects the item being assessed. The quality of a body of evidence takes into consideration within‐study risk of bias (methodological quality), directness of the evidence, heterogeneity of the data, precision of effect estimates and risk of publication bias.

Results

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; Characteristics of studies awaiting classification; Characteristics of ongoing studies.

Results of the search

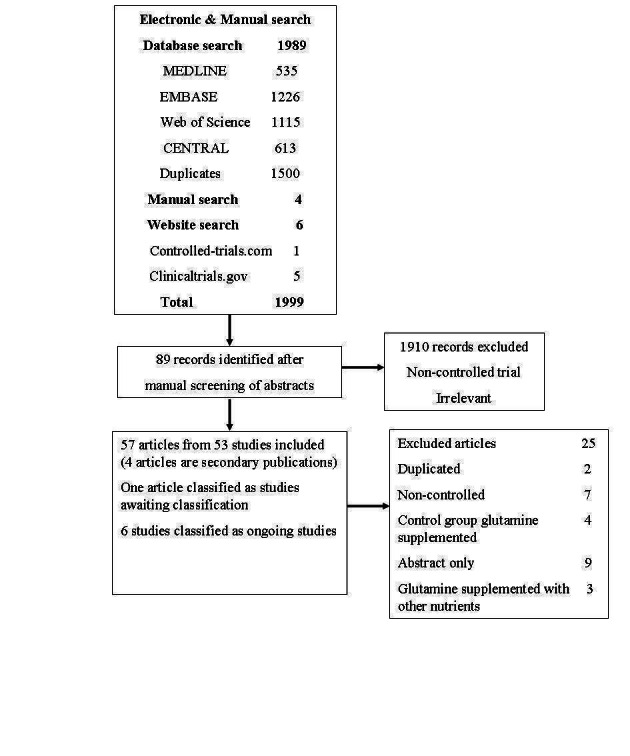

We identified a total of 1999 citations. Through reading the titles and then abstracts, we obtained the full texts of 89 citations that were potentially eligible for inclusion in our review. Of those 89 citations, 25 did not meet our inclusion criteria and were excluded for the reasons described in the table Characteristics of excluded studies. Six ongoing clinical trials were identified through searching the websites clinicaltrials.gov and controlled‐trials.com (Characteristics of ongoing studies). One study (Hallay 2002) is waiting assessment as we were unable to obtain the full text. Finally, we included 57 articles from 53 studies (four articles were secondary publications) in this review (Figure 1).

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

These 53 studies enrolled a total of 4671 patients. All participants were adults with a critical illness or undergoing elective major surgery; they were allocated to either a glutamine supplementation group or control group. All studies reported at least one of the outcomes which we had predefined in our protocol. The studies fell broadly into the following groups.

Studies in intensive care unit (ICU) patients

We included 19 studies in this category. Of these 19 studies, 12 included participants admitted to ICU with varying diagnoses (Andrews 2011; Çekmen 2011; Déchelotte 2006; Goeters 2002; Grau 2011; Griffiths 1997; Luo 2008; Pérez‐Bárcena 2008; Tjäder 2004; Tremel 1994; Wernerman 2011; Zhang 2007). Two studies included trauma patients (Eroglu 2009; Pérez‐Bárcena 2010). One study included patients with systemic inflammatory response syndrome (Conejero 2002). One study included aged patients (Chai 2006). One study included patients with multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (Tian 2006). One study included patients requiring mechanical ventilation (Hall 2003), and a further study included mechanically ventilated adult patients with two or more failed organs (Heyland 2013).

Studies in surgical patients

We included 18 studies in this category. Of these 18 studies, 14 included patients receiving abdominal surgery (Dong 2008; Fuentes‐Orozco 2004; Jiang 1999; Kłek 2005; Kumar 2007; Lin 2002; Lu 2011; Morlion 1998; Neri 2001; O'Riordain 1994; Qiu 2009; Spittler 2001; Yao 2007; Zhu 2000). Two studies included patients receiving thoracic or abdominal surgery (Estívariz 2008; Mertes 2000). One study included patients undergoing aortic abdominal aneurysm reconstruction (Karwowska 2001). One study included patients receiving laryngectomy (Wang 2006).

Studies in burns patients

Eight trials investigating the impact of glutamine supplementation in burns patients were included in the review (Cucereanu‐Badica 2013; Garrel 2003; Pattanshetti 2009; Peng 2004; Wischmeyer 2001; Zhou 2002; Zhou 2003; Zhou 2004).

Studies in patients with acute pancreatitis

Seven trials were included in this category (Fuentes‐Orozco 2008; Hajdú 2012; He 2004; Ockenga 2002; Sahin 2007; Yang 2008; Zhao 2013).

The remaining one study included patients both from ICU and other departments (Powell‐Tuck 1999).

Excluded studies

We excluded 25 clinical studies for the reasons described in the Characteristics of excluded studies.

Studies awaiting classification

One study that examined the effects of enteral glutamine supplementation in patients receiving subtotal oesophagectomy for malignancy (Hallay 2002) is waiting classification as we were unable to obtain the full text (see Characteristics of studies awaiting classification).

Ongoing studies

Six ongoing studies enrolling trauma, ICU, burns and acute pancreatitis participants were identified (see Characteristics of ongoing studies).

Risk of bias in included studies

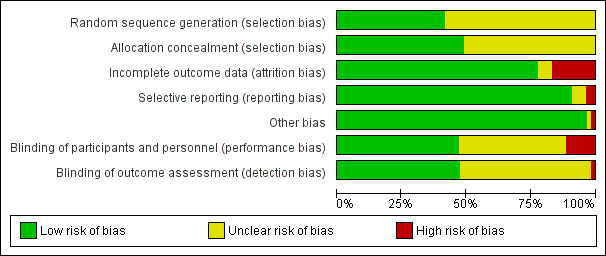

See: Characteristics of included studies; Figure 2; Figure 3.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

We analysed seven domains of potential risk of bias for the included studies; 42, 48 and 51 studies were rated at low risk of attrition bias, selective reporting bias and other bias respectively. Eighteen studies were rated at low risk of selection bias. We rated 25 studies each at low risk of performance bias and detection bias. Blinding of participants and personnel and incomplete outcome data were rated at high risk in six and nine included studies respectively.

Allocation

Eighteen studies clearly described the process for adequate generation of a randomized sequence and concealment of allocation and were classified as low risk of bias. Random sequence generation or allocation concealment was rated as having an unclear risk of bias in the remaining 35 studies due to not reporting sequence generation or allocation details. No study was rated as high risk of bias (Figure 3).

Blinding

Performance bias

Six studies were at high risk for performance bias. In four studies patients were not blinded (Kumar 2007; Pattanshetti 2009; Pérez‐Bárcena 2008; Pérez‐Bárcena 2010). One study was performed in an unblinded fashion (Goeters 2002) and in another study treatment was not blinded for the attending physicians (Tjäder 2004). Twenty‐two studies gave insufficient information to assess performance bias and 25 studies were at low risk for performance bias as blinding of participants and key study personnel was ensured in these studies (Figure 2; Figure 3).

Detection bias

One open randomized trial was rated as high risk for detection bias (Goeters 2002) and 27 included studies were rated at an unclear risk of detection bias (Figure 2; Figure 3).

Incomplete outcome data

In nine studies the number of patients withdrawn after randomization was high (4 to 49) and the studies were judged as having a high risk for attrition bias (Conejero 2002; Estívariz 2008; Garrel 2003; Goeters 2002; Hajdú 2012; Kłek 2005; Luo 2008; Mertes 2000; Yang 2008). Two studies were rated at unclear risk: one study planned to exclude the patients who died within 72 hours of admission but did not report the number of patients excluded (Pattanshetti 2009), another study withdrew five patients without giving reasons (Wernerman 2011). For the remaining 42 studies the risk of attrition bias was low (Figure 2; Figure 3).

Selective reporting

We judged two studies as high risk for reporting bias. One study did not report the length of hospital stay outcome completely (Qiu 2009), the other study did not report the length of ICU stay and all‐cause six‐month mortality outcomes completely (Wernerman 2011). We were, therefore, unable to enter these two studies in a meta‐analysis. Three studies were judged as having an unclear risk for reporting bias. One study only reported the average length of stay and mortality outcomes in the subgroup of patients treated for longer than nine days, and whether this was pre‐specified was unclear (Goeters 2002). Two other studies either did not report baseline infection associated blood test results (Pattanshetti 2009) or did not report organ function tests (Zhu 2000) and were therefore judged at unclear risk. The remaining 48 studies were free from selective reporting bias (Figure 2; Figure 3).

Other potential sources of bias

One study had baseline bias and was rated at high risk. This was because the patients in the treatment group were younger than those in the control group (Kumar 2007). In another study, patients that were clinically accepted for parenteral nutrition were included in the trial, it was unclear whether the patients were all critically ill. This study was rated at unclear risk (Powell‐Tuck 1999). No other significant potential sources of bias were identified in the remaining trials (Figure 2; Figure 3).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

See: summary of findings for the main comparison glutamine supplementation for critically ill adults, Table 1.

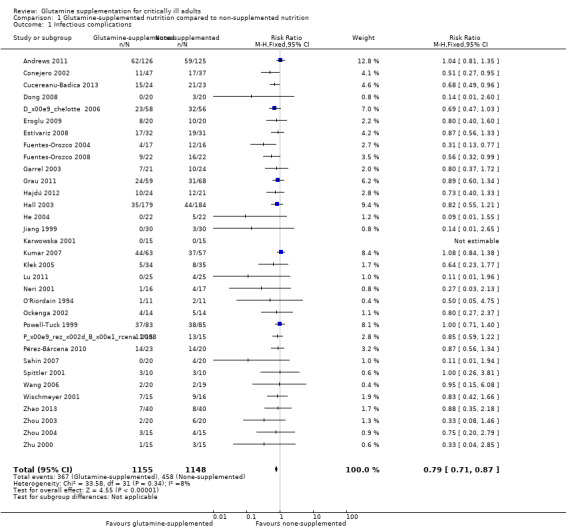

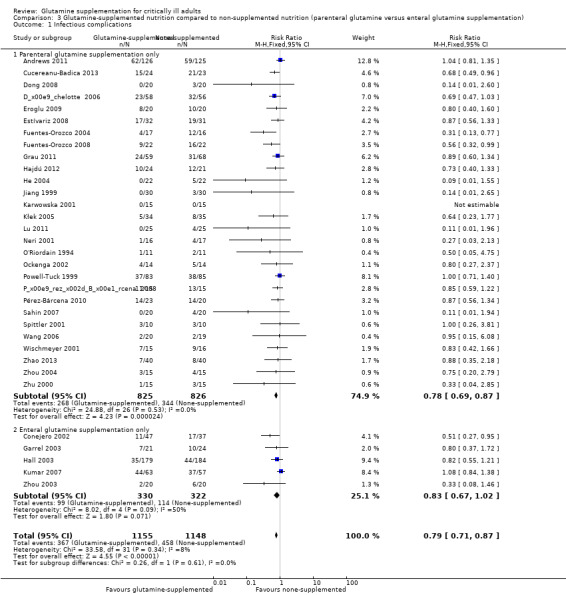

Infectious complications

Thirty‐three trials (including 2303 patients) provided data on the nosocomial infectious complications (see Characteristics of included studies). The absolute risk for infectious complications was 39.9% (458/1148) in the control group and 31.8% (367/1155) in the intervention group. Pooling of these data suggested that glutamine supplementation reduced the infectious complications rate in adults with critical illness or undergoing elective major surgery (RR 0.79, 95% CI 0.71 to 0.87, P < 0.00001, I² = 8%) (Analysis 1.1). By setting the assumed control risk at 40%, we calculated the number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome as 12. The funnel plot for this outcome was asymmetrical, suggesting that smaller studies with outcomes favouring non‐supplemented patients appeared to be lacking. One newly published large sample, randomized blinded trial (Heyland 2013) provided data on the infectious outcome in glutamine supplementation patients together with patients on antioxidant supplementation. We were told by the author that the detailed infectious incidence in glutamine supplementation patients will be published in the future (Heyland 2013 [pers comm]). This study was not included in the analysis. We also used the trim and fill method for this outcome to identify and correct for funnel plot asymmetry arising from publication bias. The method suggested that 13 studies are missing. Using a fixed‐effect model (inverse variance method) the original point estimate (RR) and 95% CI for the combined studies was 0.84 (95% CI 0.80 to 0.92). Using trim and fill the imputed point estimate was 0.89 (95% CI 0.81 to 0.98). Using the random‐effects model the RR was 0.83 (95% CI 0.75 to 0.92). Using trim and fill the imputed point estimate was 0.87 (95% CI 0.77 to 0.99). These results suggested that the combined results were not changed after adding the missing studies.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Glutamine‐supplemented nutrition compared to non‐supplemented nutrition, Outcome 1 Infectious complications.

Sensitivity analysis showed that the risk of infectious complications in the low risk of bias studies (Andrews 2011; Déchelotte 2006; Dong 2008; Grau 2011; Hall 2003; Zhou 2003; Zhou 2004) was not different between the groups (RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.72 to 1.01, P = 0.06, I² = 9%). The difference in combined effect size between the main analysis and the sensitivity analysis could be explained by the reduced sample size but more importantly the change in RR from 0.79 in the main analysis to 0.85 in the sensitivity analysis suggested that the effect size could have been partly explained by within study biases.

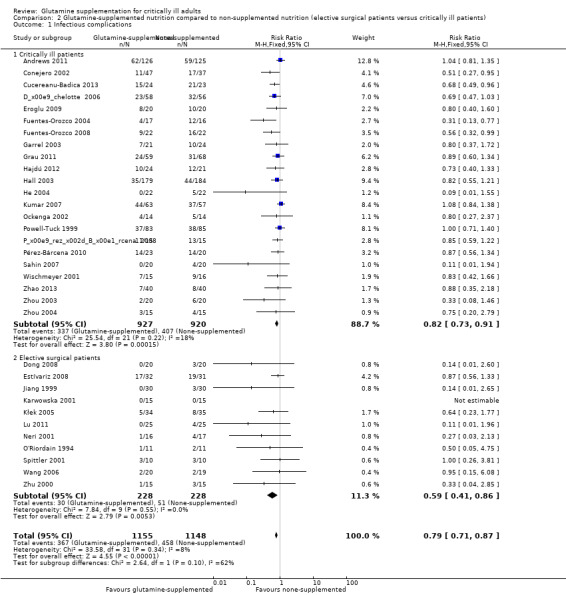

Infectious complications: elective surgery patients versus critically ill patients

Eleven trials (Dong 2008; Estívariz 2008; Jiang 1999; Karwowska 2001; Kłek 2005; Lu 2011; Neri 2001; O'Riordain 1994; Spittler 2001; Wang 2006; Zhu 2000) included 456 patients who were enrolled for elective surgery. The pooled RR was 0.59 (95% CI 0.41 to 0.86, P = 0.005, I² = 0%). Twenty‐two trials (Andrews 2011; Conejero 2002; Cucereanu‐Badica 2013; Déchelotte 2006; Eroglu 2009; Fuentes‐Orozco 2004; Fuentes‐Orozco 2008; Garrel 2003; Grau 2011; Hajdú 2012; Hall 2003; He 2004; Kumar 2007; Ockenga 2002; Pérez‐Bárcena 2008; Pérez‐Bárcena 2010; Powell‐Tuck 1999; Sahin 2007; Wischmeyer 2001; Zhao 2013; Zhou 2003; Zhou 2004) that enrolled 1847 critically ill patients were pooled to give a RR of 0.82 (95% CI 0.73 to 0.91, P = 0.001, I² = 18%) (Analysis 2.1).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Glutamine‐supplemented nutrition compared to non‐supplemented nutrition (elective surgical patients versus critically ill patients), Outcome 1 Infectious complications.

Infectious complications: enteral glutamine supplementation versus parenteral glutamine supplementation

Twenty‐eight studies (Andrews 2011; Cucereanu‐Badica 2013; Déchelotte 2006; Dong 2008; Eroglu 2009; Estívariz 2008; Fuentes‐Orozco 2004; Fuentes‐Orozco 2008; Grau 2011; Hajdú 2012; He 2004; Jiang 1999; Karwowska 2001; Kłek 2005; Lu 2011; Neri 2001; Ockenga 2002; O'Riordain 1994; Pérez‐Bárcena 2008; Pérez‐Bárcena 2010; Powell‐Tuck 1999; Sahin 2007; Spittler 2001; Wang 2006; Wischmeyer 2001; Zhao 2013; Zhou 2004; Zhu 2000) examined the effects of parenteral glutamine supplementation on infection. Meta‐analysis showed a lower risk of infectious complications in patients receiving parenteral glutamine supplementation than those without glutamine supplementation (RR 0.78, 95% CI 0.69 to 0.87, P < 0.00001, I² = 0%). Five studies (Conejero 2002; Garrel 2003; Hall 2003; Kumar 2007; Zhou 2003) tested the effects of enteral glutamine supplementation on the infection rate. There was no significant difference between the treatment and control groups (RR 0.83, 95% CI 0.67 to 1.02, P = 0.07, I² = 50%) (Analysis 3.1). The test for subgroup differences was not statistically significant (P = 0.61).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Glutamine‐supplemented nutrition compared to non‐supplemented nutrition (parenteral glutamine versus enteral glutamine supplementation), Outcome 1 Infectious complications.

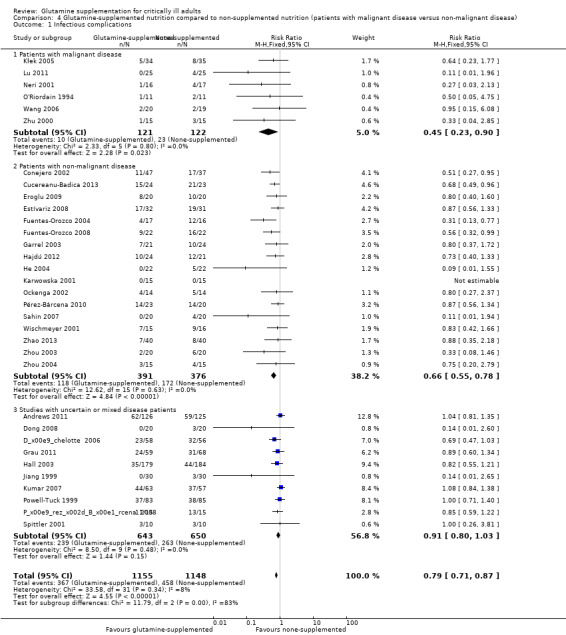

Infectious complications: patients with malignant disease versus patients with non‐malignant disease

Six studies (Kłek 2005; Lu 2011; Neri 2001; O'Riordain 1994; Wang 2006; Zhu 2000) included surgical patients with malignant disease and the pooled RR was 0.45 (95% CI 0.23 to 0.90, P = 0.02, I² = 0%). Seventeen studies (Conejero 2002; Cucereanu‐Badica 2013; Eroglu 2009; Estívariz 2008; Fuentes‐Orozco 2004; Fuentes‐Orozco 2008; Garrel 2003; Hajdú 2012; He 2004; Karwowska 2001; Ockenga 2002; Pérez‐Bárcena 2010; Sahin 2007; Wischmeyer 2001; Zhao 2013; Zhou 2003; Zhou 2004) enrolled patients with non‐malignant disease. The pooled analysis showed that the risk of infectious complications was lower in the glutamine supplemented patients than in the patients that did not receive the supplement (RR 0.66, 95% CI 0.55 to 0.78, P < 0.00001, I² = 0%). The remaining 10 studies (Andrews 2011; Déchelotte 2006; Dong 2008; Grau 2011; Hall 2003; Jiang 1999; Kumar 2007; Pérez‐Bárcena 2008; Powell‐Tuck 1999; Spittler 2001) enrolled patients with uncertain or mixed disease. The pooled RR was 0.91 (95% CI 0.80 to 1.03, P = 0.15, I² = 0%) (Analysis 4.1).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Glutamine‐supplemented nutrition compared to non‐supplemented nutrition (patients with malignant disease versus non‐malignant disease), Outcome 1 Infectious complications.

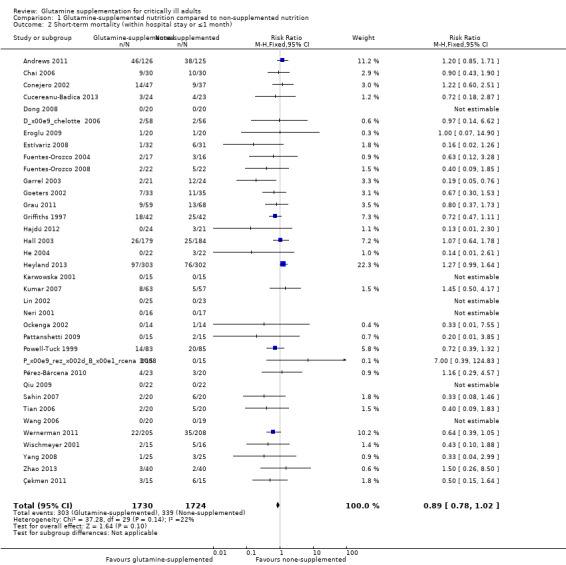

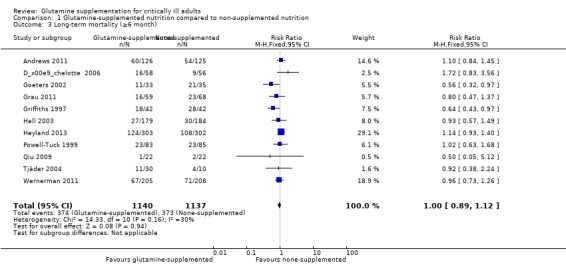

Mortality

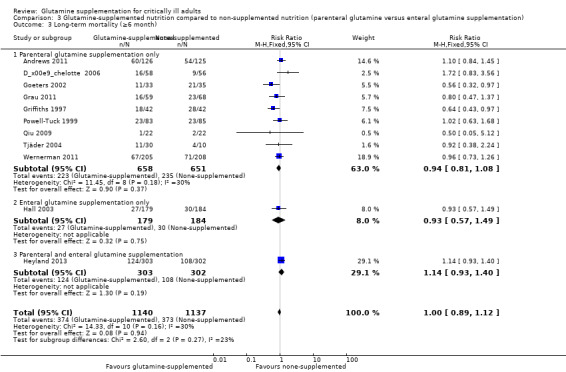

Thirty‐seven studies (3494 patients) reported on mortality. Of these 37 studies, 36 (Andrews 2011; Çekmen 2011; Chai 2006; Conejero 2002; Cucereanu‐Badica 2013; Déchelotte 2006; Dong 2008; Eroglu 2009; Estívariz 2008; Fuentes‐Orozco 2004; Fuentes‐Orozco 2008; Garrel 2003; Goeters 2002; Grau 2011; Griffiths 1997; Hajdú 2012; Hall 2003; He 2004; Heyland 2013; Karwowska 2001; Kumar 2007; Lin 2002; Neri 2001; Ockenga 2002; Pattanshetti 2009; Pérez‐Bárcena 2008; Pérez‐Bárcena 2010; Powell‐Tuck 1999; Qiu 2009; Sahin 2007; Tian 2006; Wang 2006; Wernerman 2011; Wischmeyer 2001; Yang 2008; Zhao 2013) reported short‐term (hospital or closest to one month) mortality. The combined rate of mortality from these studies was not statistically different between the group which received a glutamine supplement and the group which did not (RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.78 to 1.02, P = 0.10, I² = 22%) (Analysis 1.2). Eleven studies (Andrews 2011; Déchelotte 2006; Goeters 2002; Grau 2011; Griffiths 1997; Hall 2003; Heyland 2013; Powell‐Tuck 1999; Qiu 2009; Tjäder 2004; Wernerman 2011) reported long‐term (closest to six months) mortality. Meta‐analysis of these 11 studies yielded an RR of 1.00 (95% CI 0.89 to 1.12, P = 0.94, I² = 30%) (Analysis 1.3). The funnel plot for the short‐term mortality outcome was asymmetrical, suggesting that smaller studies with outcomes favouring non‐supplemented patients appeared to be lacking; while the funnel plot for the long‐term mortality outcome was symmetrical. The trim and fill method suggested that 10 studies were missing for the short‐term mortality outcome, and results indicated that the combined results were not changed after filling in these missing studies. Using the fixed‐effect model (inverse variance method) the original point estimate (RR) for the combined studies was 0.93 (95% CI 0.81 to 1.07). Using the trim and fill method the imputed point estimate was 1.00 (95% CI 0.87 to 1.14). Using the random‐effects model the RR for the combined studies was 0.83 (95% CI 0.69 to 1.00). Using trim and fill the imputed RR was 0.93 (95% CI 0.76 to 1.15).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Glutamine‐supplemented nutrition compared to non‐supplemented nutrition, Outcome 2 Short‐term mortality (within hospital stay or ≤1 month).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Glutamine‐supplemented nutrition compared to non‐supplemented nutrition, Outcome 3 Long‐term mortality (≥6 month).

Sensitivity analysis showed that both the short‐ and long‐term mortality rates in low risk of bias studies were not different between the groups (RR 1.10, 95% CI 0.93 to 1.30, P = 0.29, I² = 21%; RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.80 to 1.23, P = 0.96, I² = 46% respectively).

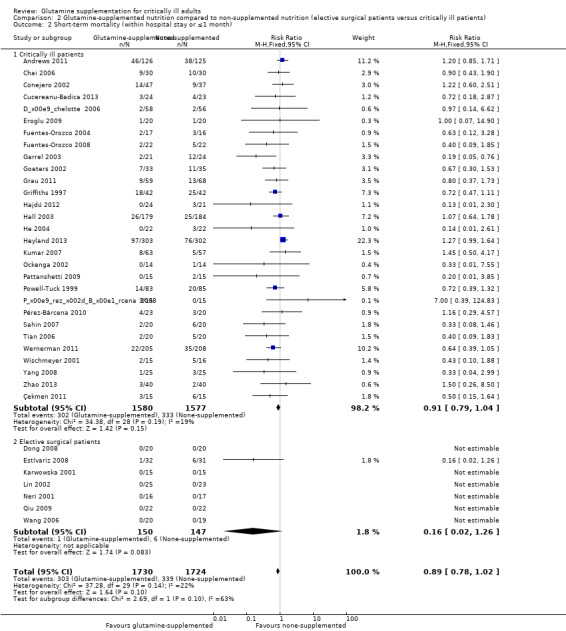

Short‐term mortality: elective surgery patients versus critically ill patients

Twenty‐nine studies (Andrews 2011; Çekmen 2011; Chai 2006; Conejero 2002; Cucereanu‐Badica 2013; Déchelotte 2006; Eroglu 2009; Fuentes‐Orozco 2004; Fuentes‐Orozco 2008; Garrel 2003; Goeters 2002; Grau 2011; Griffiths 1997; Hajdú 2012; Hall 2003; He 2004; Heyland 2013; Kumar 2007; Ockenga 2002; Pattanshetti 2009; Pérez‐Bárcena 2008; Pérez‐Bárcena 2010; Powell‐Tuck 1999; Sahin 2007; Tian 2006; Wernerman 2011; Wischmeyer 2001; Yang 2008; Zhao 2013) enrolling 3157 critically ill patients reported short‐term mortality. The pooled RR was 0.91 (95% CI 0.79 to 1.04, P = 0.15, I² = 19%). The mortality outcome was reported in seven studies (Dong 2008; Estívariz 2008; Karwowska 2001; Lin 2002; Neri 2001; Qiu 2009; Wang 2006) enrolling patients for elective surgery. No deaths occurred during the study period in six of the seven studies so the data could not be combined (Analysis 2.2).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Glutamine‐supplemented nutrition compared to non‐supplemented nutrition (elective surgical patients versus critically ill patients), Outcome 2 Short‐term mortality (within hospital stay or ≤1 month).

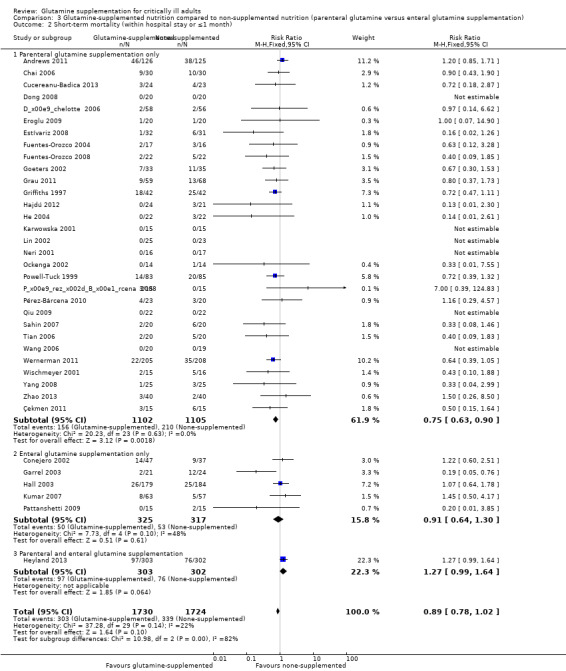

Short‐term mortality: enteral glutamine supplementation versus parenteral glutamine supplementation

Five clinical trials (Conejero 2002; Garrel 2003; Hall 2003; Kumar 2007; Pattanshetti 2009) examined the effects of enteral glutamine supplementation on short‐term mortality. Pooling of these studies suggested no difference in mortality rate between the intervention and control groups (RR 0.91, 95% CI 0.64 to 1.30, P = 0.61, I² = 48%). Thirty trials (Andrews 2011; Çekmen 2011; Chai 2006; Cucereanu‐Badica 2013; Déchelotte 2006; Dong 2008; Eroglu 2009; Estívariz 2008; Fuentes‐Orozco 2004; Fuentes‐Orozco 2008; Goeters 2002; Grau 2011; Griffiths 1997; Hajdú 2012; He 2004; Karwowska 2001; Lin 2002; Neri 2001; Ockenga 2002; Pérez‐Bárcena 2008; Pérez‐Bárcena 2010; Powell‐Tuck 1999; Qiu 2009; Sahin 2007; Tian 2006; Wang 2006; Wernerman 2011; Wischmeyer 2001; Yang 2008; Zhao 2013) used parenterally supplemented glutamine. We pooled the data on the 2207 patients enrolled in these studies, which yielded a RR of 0.75 (95% CI 0.63 to 0.90, P = 0.002, I² = 0%) (Analysis 3.2). Only one study (Heyland 2013) supplemented glutamine both parenterally and enterally but this study could not be entered into a subgroup analysis.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Glutamine‐supplemented nutrition compared to non‐supplemented nutrition (parenteral glutamine versus enteral glutamine supplementation), Outcome 2 Short‐term mortality (within hospital stay or ≤1 month).

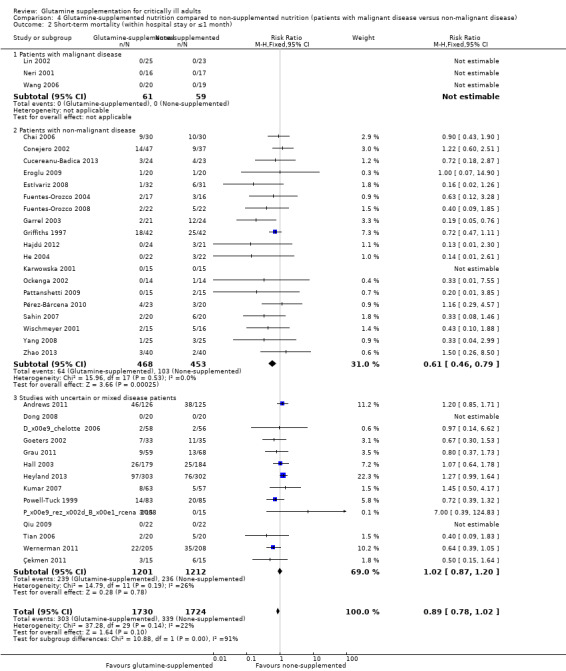

Short‐term mortality: patients with malignant disease versus patients with non‐malignant disease

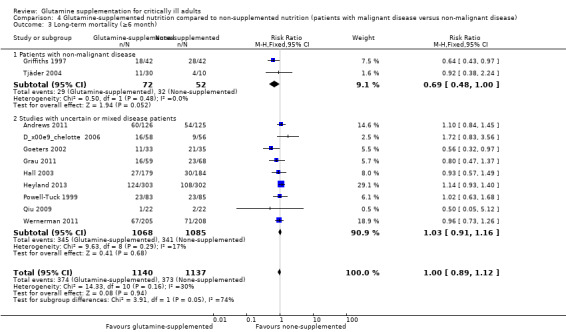

Three studies (Lin 2002; Neri 2001; Wang 2006) included 120 surgical patients with malignant disease. No deaths occurred during the study period in these three studies, so the RR could not be estimated. Nineteen studies (Chai 2006; Conejero 2002; Cucereanu‐Badica 2013; Eroglu 2009; Estívariz 2008; Fuentes‐Orozco 2004; Fuentes‐Orozco 2008; Garrel 2003; Griffiths 1997; Hajdú 2012; He 2004; Karwowska 2001; Ockenga 2002; Pattanshetti 2009; Pérez‐Bárcena 2010; Sahin 2007; Wischmeyer 2001; Yang 2008; Zhao 2013) enrolled 921 patients with non‐malignant disease. The pooled analysis of these studies showed a lower mortality risk for participants receiving glutamine supplementation compared with those receiving placebo (RR 0.61, 95% CI 0.46 to 0.79, P = 0.002, I² = 0%). The remaining 14 studies (Andrews 2011; Çekmen 2011; Déchelotte 2006; Dong 2008; Goeters 2002; Grau 2011; Hall 2003; Heyland 2013; Kumar 2007; Pérez‐Bárcena 2008; Powell‐Tuck 1999; Qiu 2009; Tian 2006; Wernerman 2011) enrolled 2413 patients with uncertain or mixed disease, and the pooled RR was 1.02 (95% CI 0.87 to 1.20, P = 0.78, I² = 26%) (Analysis 4.2).

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Glutamine‐supplemented nutrition compared to non‐supplemented nutrition (patients with malignant disease versus non‐malignant disease), Outcome 2 Short‐term mortality (within hospital stay or ≤1 month).

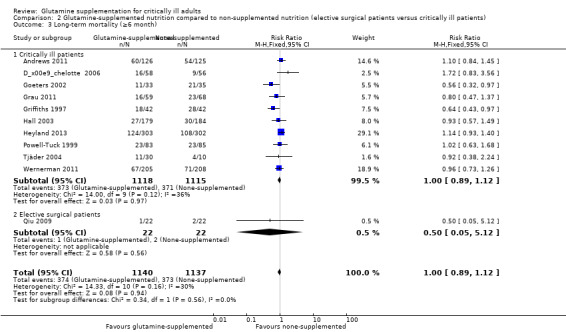

Long‐term mortality

Data on 124 patients with non‐malignant disease from two studies comparing nutrition with glutamine supplementation to nutrition without glutamine supplementation (Griffiths 1997; Tjäder 2004) were pooled to give a RR of 0.69 (95% CI 0.48 to 1.00, P = 0.05, I² = 0%). The remaining subgroup analysis did not find a mortality difference between the groups (Analysis 2.3; Analysis 3.3; Analysis 4.3).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Glutamine‐supplemented nutrition compared to non‐supplemented nutrition (elective surgical patients versus critically ill patients), Outcome 3 Long‐term mortality (≥6 month).

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Glutamine‐supplemented nutrition compared to non‐supplemented nutrition (parenteral glutamine versus enteral glutamine supplementation), Outcome 3 Long‐term mortality (≥6 month).

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Glutamine‐supplemented nutrition compared to non‐supplemented nutrition (patients with malignant disease versus non‐malignant disease), Outcome 3 Long‐term mortality (≥6 month).

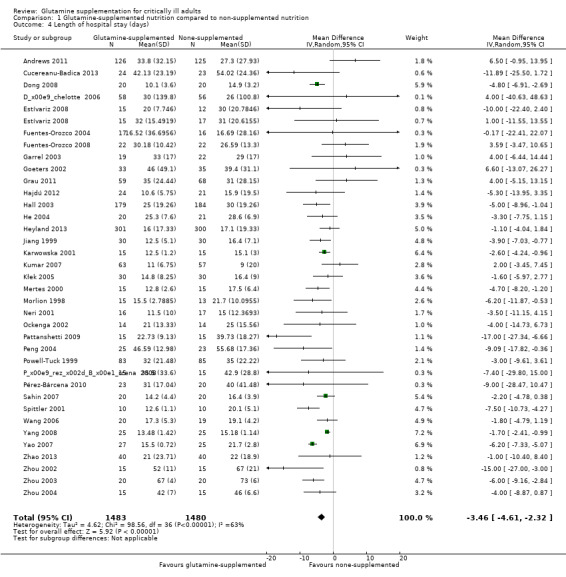

Length of hospital stay

Hospital length of stay was reported in 36 studies (see Characteristics of included studies). Of these 36 studies, 25 (Cucereanu‐Badica 2013; Dong 2008; Estívariz 2008; Fuentes‐Orozco 2004; Fuentes‐Orozco 2008; Garrel 2003; Goeters 2002; He 2004; Jiang 1999; Karwowska 2001; Mertes 2000; Morlion 1998; Neri 2001; Pattanshetti 2009; Peng 2004; Pérez‐Bárcena 2008; Sahin 2007; Spittler 2001; Wang 2006; Yang 2008; Yao 2007; Zhao 2013; Zhou 2002; Zhou 2003; Zhou 2004) reported the outcome as mean (standard deviation or standard error of mean). Pooled analysis of these studies showed that the length of hospital stay was shorter in the glutamine supplementation group than in the control group (mean difference (MD) ‐4.14, 95% CI ‐5.46 to ‐2.81, P < 0.0001, I² = 70%). In the remaining 11 studies (Andrews 2011; Déchelotte 2006; Grau 2011; Hajdú 2012; Hall 2003; Heyland 2013; Kumar 2007; Kłek 2005; Ockenga 2002; Pérez‐Bárcena 2010; Powell‐Tuck 1999) the data were reported as the median (interquartile range) or median (range). The median (range) in each study was converted into mean (standard deviation) by using the formula from Hozo 2005, while the estimated standard deviation was calculated from the interquartile range based on the assumption that the width of the interquartile range was approximately 1.35 standard deviations (Handbook 2011). All 36 studies were included in the meta‐analysis after conversion and the results suggested that the length of hospital stay was shorter in the intervention group than in the control group (MD ‐3.46, 95% CI ‐4.61 to ‐2.32, P < 0.0001, I² = 63%) (Analysis 1.4). The funnel plot for this outcome was symmetrical.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Glutamine‐supplemented nutrition compared to non‐supplemented nutrition, Outcome 4 Length of hospital stay (days).

Sensitivity analysis, including eight low risk of bias studies (Andrews 2011; Déchelotte 2006; Dong 2008; Grau 2011; Hall 2003; Heyland 2013; Zhou 2003; Zhou 2004), also showed that glutamine supplementation had beneficial effects in reducing the length of hospital stay (MD ‐2.9, 95% CI ‐5.3 to ‐0.5, P = 0.02, I² = 58%).

The substantial heterogeneity between studies for this outcome may have been because these studies included participants with different categories of disease. Hence we did the following subgroup analysis according to types of diseases. Among the 36 trials, seven trials included burns patients (Cucereanu‐Badica 2013; Garrel 2003; Pattanshetti 2009; Peng 2004; Zhou 2002; Zhou 2003; Zhou 2004) and seven trials included acute pancreatitis patients (Fuentes‐Orozco 2008; Hajdú 2012; He 2004; Ockenga 2002; Sahin 2007; Yang 2008; Zhao 2013). Meta‐analysis of these two subgroups suggested beneficial effects of glutamine in reducing the length of hospital stay, with mild to moderate heterogeneity between studies (MD ‐7.24, 95% CI ‐11.28 to ‐3.21, P = 0.0004, I² = 49% for burn patients; MD ‐1.75, 95% CI ‐2.42 to ‐1.08, P < 0.00001, I² = 0% for acute pancreatitis patients). However, combining the data from nine trials that included critically ill patients other than burns and acute pancreatitis patients (Andrews 2011; Déchelotte 2006; Goeters 2002; Grau 2011; Hall 2003; Heyland 2013; Pérez‐Bárcena 2008; Pérez‐Bárcena 2010; Powell‐Tuck 1999) revealed that there was no difference between the treatment and control groups, with moderate heterogeneity between studies (MD ‐1.16, 95% CI ‐4.05 to 1.72, P = 0.43, I² = 25%). A meta‐analysis of 13 trials including surgical patients (Dong 2008; Estívariz 2008; Fuentes‐Orozco 2004; Jiang 1999; Karwowska 2001; Kumar 2007; Kłek 2005; Mertes 2000; Morlion 1998; Neri 2001; Spittler 2001; Wang 2006; Yao 2007) showed that there was still substantial heterogeneity among these studies (MD ‐4.04, 95% CI ‐5.44 to ‐2.64, P < 0.00001, I² = 56%). This may have been because patients received different types of surgery in these studies.

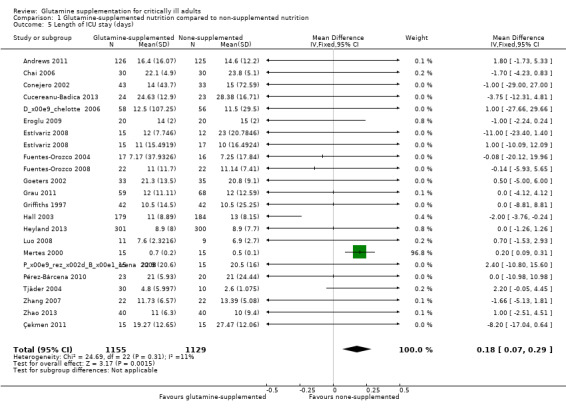

Length of intensive care unit (ICU) stay

We analysed 22 studies (see Characteristics of included studies) which reported the length of stay in ICU. The data were combined using the fixed‐effect model and revealed slightly prolonged ICU stay in the glutamine supplemented group (MD 0.18, 95% CI 0.07 to 0.29, P = 0.002, I² = 11%) (Analysis 1.5). Using the random‐effects model there was no significant difference in ICU days between the treatment and control groups (MD ‐0.12, 95% CI ‐0.62 to 0.37, P = 0.63, I² = 11%). The funnel plot for this meta‐analysis was symmetrical.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Glutamine‐supplemented nutrition compared to non‐supplemented nutrition, Outcome 5 Length of ICU stay (days).

Of the 22 studies, eight studies (Andrews 2011; Conejero 2002; Déchelotte 2006; Grau 2011; Griffiths 1997; Hall 2003; Heyland 2013; Pérez‐Bárcena 2010) reported the days in ICU as the median (range) or median (interquartile range). They were changed into mean (standard deviation) as described above (Measures of treatment effect). A sensitivity analysis, excluding these studies by using the fixed‐effect model, reported the same result (MD 0.19, 95% CI 0.08 to 0.30, P = 0.001, I² = 22%). A sensitivity analysis including seven low risk of bias studies (Andrews 2011; Déchelotte 2006; Grau 2011; Griffiths 1997; Hall 2003; Heyland 2013; Çekmen 2011) and using the fixed‐effect model or the random‐effects model showed that glutamine supplementation had no effect on reducing the length of ICU stay (MD ‐0.54, 95% CI ‐1.48 to 0.4, P = 0.26, I² = 25%; MD ‐0.6, 95% CI ‐1.98 to 0.79, P = 0.40, I² = 25%, respectively).

Days on mechanical ventilation

Eleven studies with 455 patients (Chai 2006; Cucereanu‐Badica 2013; Eroglu 2009; Estívariz 2008; Fuentes‐Orozco 2004; Fuentes‐Orozco 2008; Garrel 2003; Heyland 2013; Pérez‐Bárcena 2008; Pérez‐Bárcena 2010; Zhang 2007) reported this outcome as the mean (standard deviation). The combined MD of these studies was ‐1.54 days (95% CI ‐2.44 to ‐0.65, P = 0.0008, I² = 0%) suggesting that glutamine supplementation reduced the number of days on mechanical ventilation in critically ill and surgical patients. In three studies (Déchelotte 2006; Grau 2011; Heyland 2013) the original data were reported as the median (interquartile ranges) or median (range). These studies were included in the meta‐analysis after they were converted into the mean (standard deviation) and the combined MD of all 14 studies was ‐0.69 days (95% CI ‐1.37 to ‐0.02, P = 0.04, I² = 18%) (Analysis 1.6). The funnel plot for this outcome was symmetrical, suggesting no evidence of publication bias for this outcome.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Glutamine‐supplemented nutrition compared to non‐supplemented nutrition, Outcome 6 Days on mechanical ventilation.

Sensitivity analysis including three low risk of bias studies (Déchelotte 2006; Grau 2011; Heyland 2013) showed that glutamine supplementation did not reduce the number of days on mechanical ventilation (MD 0.37, 95% CI ‐0.64 to 1.38, P = 0.47, I² = 32%).

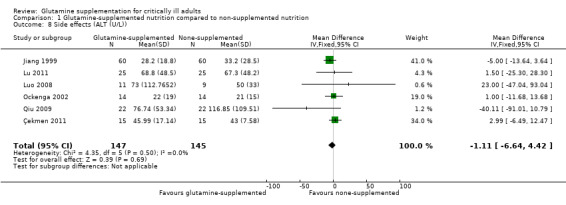

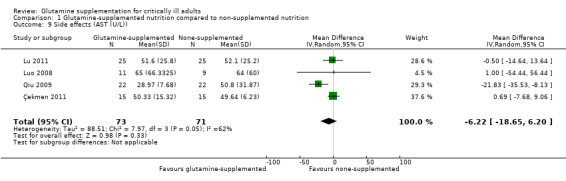

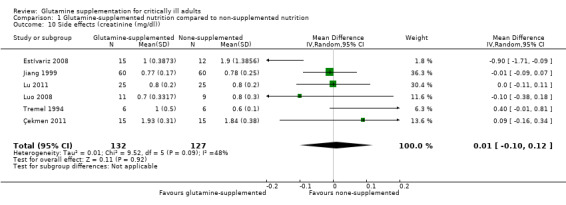

Side effects

Eleven studies (Estívariz 2008; Çekmen 2011; Goeters 2002; Grau 2011; Lin 2002; Morlion 1998; Neri 2001; Pérez‐Bárcena 2008; Pérez‐Bárcena 2010; Yao 2007; Zhu 2000) reported that glutamine supplementation was well tolerated and no adverse events related to the administration of glutamine were observed. In two large sample, clinical trials (Andrews 2011; Heyland 2013) with 856 patients the serious adverse events outcome was reported and the pooled analysis of these two studies revealed that there was no significant difference in the risk of serious adverse events between the intervention and control groups (RR 1.40, 95% CI 0.77 to 2.57, P = 0.27, I² = 0%) (Analysis 1.7). In one trial (Heyland 2013) it was also found that the frequency of high urea levels (> 50 mmol/L) was higher among patients who received glutamine than for those that did not (13.4% versus 4.0%, P < 0.001). However, meta‐analysis of biological markers of liver and kidney function, such as alanine aminotransferase (Analysis 1.8), aspartate aminotransferase (Analysis 1.9) and creatinine (Analysis 1.10), did not find any difference between the groups during the treatment period. A further three studies reported on side effects. Two studies (Conejero 2002; Hall 2003) that supplemented glutamine enterally in critical ill patients reported gastrointestinal complications. The incidence of gastrointestinal complications was similar between the two groups. One study (Déchelotte 2006) of parenterally supplemented glutamine for ICU patients found that the number of adverse events per patient was significantly lower in the alanyl‐glutamine group than in the placebo group (2.0 versus 2.8, P < 0 .01).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Glutamine‐supplemented nutrition compared to non‐supplemented nutrition, Outcome 7 Serious adverse events.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Glutamine‐supplemented nutrition compared to non‐supplemented nutrition, Outcome 8 Side effects (ALT (U/L)).

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Glutamine‐supplemented nutrition compared to non‐supplemented nutrition, Outcome 9 Side effects (AST (U/L)).

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Glutamine‐supplemented nutrition compared to non‐supplemented nutrition, Outcome 10 Side effects (creatinine (mg/dl)).

Quality of life

This outcome was recorded in four studies. One study (Griffiths 1997) used the Whiston Health Questionnaire (Jones 1993) to assess patients' pre‐morbid health status and found that the morbidity of the participants at six months was similar between the glutamine supplemented and control groups. One study (Hall 2003) described the functional status of surviving patients at six months, and no differences were detected between the two groups. In one study (Powell‐Tuck 1999) patients were asked to score their mood, sleep, energy, appetite, pain, and mobilization on a 10‐point scale with 0 = 'perfect' and 10 = 'as bad as it can be'. No statistical difference was found between the intervention and control groups at the end of the treatment. In another study (Andrews 2011) quality of life measures (SF‐12 and EQ‐5D questionnaires) were collected at three and six months by post; the results have not been published.

Discussion

The results of our meta‐analysis provided moderate evidence that glutamine supplementation could reduce the infection rate and days on mechanical ventilation, and low quality evidence that glutamine supplementation reduced length of hospital stay in critically ill or surgical participants. However, the differences in risk of mortality, length of ICU stay and quality of life were not significant between the intervention and control groups. According to the results of predefined subgroup analyses, our review also suggests that the effects of glutamine supplementation in reducing the risk of infectious complications and mortality were not different between elective surgical patients and critically ill patients, patients receiving enteral supplementation and parenteral supplementation, and patients with malignant and non‐malignant diseases respectively.

Enteral nutrition is the preferred way of feeding the critically ill patient (Kreymann 2006), however our review suggested that parenteral glutamine had the same effect in reducing the risk of infectious complications and mortality in critically ill patients. Considering the biologically plausible reasons for this result, there is a clinical study suggesting that the intestinal absorption of glutamine was impaired during critically ill conditions (Salloum 1991). Still, in a clinical trial in which glutamine was enterally supplemented at a dose of 26 g/day in burns patients it was found that there was no difference in plasma glutamine levels between the supplemented and non‐supplemented groups, suggesting that most of the glutamine that is administered is consumed by the gut. The immune system outside the gut would not have been affected by the glutamine supplementation (Garrel 2003).

Several meta‐analyses had been undertaken to examine the effects of perioperative glutamine supplementation in surgical patients (Wang 2010; Yue 2013; Zheng 2006). These meta‐analyses all found that perioperative glutamine supplementation is safe in reducing the morbidity of postoperative infectious complications in surgical patients. In this review we have included 18 studies on surgical patients. For the short‐ and long‐term mortality outcomes, deaths were reported in only one trial for each (Estívariz 2008; Qiu 2009). This prohibited further analysis. For infectious complications, our subgroup analysis revealed that glutamine supplementation had beneficial effects in reducing the risk of infection in both critically ill and surgical participants. This result suggests that participants with critical illness or undergoing elective major surgery may have similar glutamine deficiencies. Further research focusing on the different effects of glutamine supplementation in these two groups of patients may not be required.

In this systematic review we also predefined a subgroup analysis to compare the treatment effects of glutamine in participants with malignant and non‐malignant disease. Cancer patients included in this meta‐analysis were all surgical patients, hence we found that the results in cancer patients were the same as those in surgical patients. Still, the studies that we included mostly focused on non‐oncology or mixed disease patients. Few trials have focused on oncology patients but their results showed an infection benefit in this population. No conclusions can be drawn on the differences in risk of infection and death between oncology and non‐oncology patients given the limited data available. There is still a lack of large, quality trials that focus on oncology patients.

Summary of main results

This meta‐analysis found moderate evidence that glutamine supplementation could reduce the infection rate and days on mechanical ventilation in critically ill or surgical participants. However, it seems to have little or no effect on the risk of mortality and length of ICU stay. Although there is substantial heterogeneity within the included studies, our review also suggests that glutamine supplementation may reduce the length of hospital stay in these participants (Table 1).

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

We investigated 53 controlled clinical trials that met our predefined inclusion criteria for the participants, intervention and outcomes. The pre‐specified objectives and outcomes of the review are sufficiently addressed, except for the quality of life outcome. Quality of life was only descriptively analysed in this review as there were few included studies that reported on this outcome, and they used different measurement scales.

In recent guidelines on nutrition support, parenteral supplementation with glutamine was supported in critically ill patients, while enteral glutamine supplementation in surgical or critically ill patients was not recommended because of lack of evidence (Clinical Evaluation Research Unit 2013; Kreymann 2006; Singer 2009). Our review further classified and analysed this evidence and will provide guidance for clinical nutrition therapy.

Quality of the evidence

We identified 10 low risk of bias studies (Andrews 2011; Çekmen 2011; Déchelotte 2006; Dong 2008; Grau 2011; Griffiths 1997; Hall 2003; Heyland 2013; Zhou 2003; Zhou 2004); 16 high risk of bias studies (Conejero 2002; Estívariz 2008; Garrel 2003; Goeters 2002; Hajdú 2012; Kłek 2005; Kumar 2007; Luo 2008; Mertes 2000; Pattanshetti 2009; Pérez‐Bárcena 2008; Pérez‐Bárcena 2010; Qiu 2009; Tjäder 2004; Wernerman 2011; Yang 2008); and 27 studies with an unclear risk of bias (Chai 2006; Cucereanu‐Badica 2013; Eroglu 2009; Fuentes‐Orozco 2004; Fuentes‐Orozco 2008; He 2004; Jiang 1999; Karwowska 2001; Lin 2002; Lu 2011; Morlion 1998; Neri 2001; Ockenga 2002; O'Riordain 1994; Peng 2004; Powell‐Tuck 1999; Sahin 2007; Spittler 2001; Tian 2006; Tremel 1994; Wang 2006; Wischmeyer 2001; Yao 2007; Zhang 2007; Zhao 2013; Zhou 2002; Zhu 2000).

Potential biases in the review process

Firstly, the risk of overall bias in our review is probably high as four‐fifths of the included studies were judged as having unclear or high risk of bias (Figure 2; Figure 3). Secondly, we converted continuous outcomes that were reported as the median (range) or median (interquartile range) into the mean (SD), this will introduce bias in the final results of the meta‐analysis. Thirdly, although efforts were made to retrieve all relevant trials, there is still one article that is awaiting classification (Hallay 2002). Fourthly, the meta‐analysis of infection and short‐term mortality outcomes included studies with no events in one arm and excluded studies where there were no events in both arms, this may introduce bias in the combined treatment effect estimates. Fifthly, funnel plots for infection and short‐term mortality suggest that smaller studies with outcomes favouring non‐supplemented patients appear to be lacking, our analysis is therefore at risk of publication bias. Finally, we could not include the detailed infectious complications results from Heyland's study (Heyland 2013), and there is time lag between the search and publication of the review dates; they are likely to introduce bias into the review process.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

The results of our review are comparable to previous meta‐analyses (Avenell 2006; Avenell 2009; Bollhalder 2013; Novak 2002). There are several differences between our review and the other published reviews. First, we included recently published RCTs (Andrews 2011; Heyland 2013) and more clinical trials were analysed with the rigorous Cochrane methods in our review. Second, we added side effects and quality of life as our secondary outcomes. Third, we undertook subgroup analysis to investigate the heterogeneity between patients with malignant and non‐malignant disease.

In this review we observed a significant effect on infection complications, which is in contrast with the results from two recently published large‐scale, high quality RCTs (Andrews 2011; Heyland 2013) that did not find any beneficial effects of glutamine supplementation for reducing the rates of mortality and infection complications in critically ill patients. On the one hand, this may have been due to the fact that we could not include in this review the detailed infectious complications reported in the Heyland study (Heyland 2013). We will include this study in the updated review when the results are published. On the other hand, the uniqueness and limitations of these two studies should be noted. Heyland's study (Heyland 2013) was distinct from other traditional glutamine trials supplementing complete parenteral nutrition in that it administered glutamine (and antioxidants) independent of any nutrition support. The average nutritional delivery for the entire study period was about 50% of the prescribed delivery, so not meeting the prescribed patient needs. In addition, more then 30% of patients in the Heyland study were found to have baseline renal failure at admission, which universally was an exclusion criterion in other traditional nutrition‐based glutamine trials. Further, all patients that were enrolled were in multi‐system organ failure at enrolment, which was an exclusion criterion in most of the previous trials using parenteral glutamine as a supplement to parenteral nutrition. Hence the Heyland study may indicate that glutamine should not be supplemented in patients early in the acute phase of critical illness, when patients are shown to have multiple organ failure or to be in unresuscitated shock requiring significant vasopressor support; and patients with renal failure who are not receiving dialysis should receive supplemental glutamine cautiously. In the Andrews trial (Andrews 2011) concerns including lack of availability of some key data regarding missing values, dropouts, protocol violations and complete follow‐up data have been raised. The actual values for the glutamine doses based on body weight have not been published and this should be noted.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

There is moderate evidence that glutamine supplementation could reduce the infection rate and days on mechanical ventilation, and low quality evidence that glutamine supplementation reduced the length of hospital stay for critically ill or surgical participants. However, it has no effect on the risk of mortality, length of ICU stay and risk of side effects in these participants. Subgroup analysis of infectious complications and mortality outcomes did not find any statistically significant difference between the predefined groups (elective surgical patients and critically ill patients, patients with enteral glutamine supplementation only and parenteral glutamine supplementation only, patients with malignant and non‐malignant disease).

Implications for research.

The strength of evidence in our review was reduced as there was a high risk of overall bias, suspected publication bias and moderate to substantial heterogeneity within the included studies. Future clinical trials on glutamine supplementation should be conducted strictly in accordance with the principles advised by the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials Statement (CONSORT) to minimize the overall risk of bias in trials. Regarding the heterogeneity between the included studies, it is possible that glutamine's beneficial effects correlate with the types and severity of the disease. Hence future high quality RCTs should focus on the differences in the glutamine supplementation effects in critically ill patients with different characteristics. In this review no conclusions have been drawn on the difference in risk of infection and death between oncology and non‐oncology patients as very few trials have focused on this subject as a primary aim. Oncology patients are theoretically more likely to be glutamine deficient and thus large, quality trials that focus on oncology patients are still needed.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 20 December 2018 | Amended | Editorial team changed to Cochrane Emergency and Critical Care |

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Chun‐bo Li for his help with statistics and advice on the methods section. We also would like to thank Jane Cracknell (Managing Editor of CARG), Harald Herkner (content and statistical editor), Ronald L Koretz, Richard D Griffiths, Daren Heyland (peer reviewers) and Ann Fonfa (consumer) for their help and editorial advice during the preparation of the protocol for the systematic review.

We would like to thank Harald Herkner (content editor), Cathal Walsh (statistical editor), Thomas Bongers, Philip C Calder, Paul Wischmeyer (peer reviewers) and Robert Wyllie (consumer referee) for their help and editorial advice during the preparation of this systematic review.

Appendices

Appendix 1. CENTRAL search strategy

#1 MeSH descriptor Glutamine explode all trees #2 MeSH descriptor Dipeptides explode all trees #3 glutamin* or dipeptid* or L?glutamin* #4 (#1 OR #2 OR #3) #5 MeSH descriptor Infection explode all trees #6 MeSH descriptor Critical Illness explode all trees #7 (critical* near ill*):ti,ab or supplement* or infect*:ti,ab #8 (#5 OR #6 OR #7) #9 (#4 AND #8)

Appendix 2. Search strategy for MEDLINE (OvidSP)

1. (glutamin* or dipeptid* or L?glutamin*).mp. or exp Glutamine/ or Dipeptides/ 2. exp Infection/ or exp Critical Illness/ or (critical* adj3 ill*).ti,ab. or supplement*.mp. or infect*.ti,ab. 3. ((randomized controlled trial or controlled clinical trial).pt. or randomized.ab. or placebo.ab. or clinical trials as topic.sh. or randomly.ab. or trial.ti.) not (animals not (humans and animals)).sh. 4. 1 and 2 and 3

Appendix 3. EMBASE (OvidSP) search strategy

1 (glutamin* or dipeptid* or l?glutamin*).ti,ab. or glutamine/ or dipeptide/ 2 infection/ or critical illness/ or (critical* adj3 ill*).ti,ab. or supplement*.mp. or infect*.ti,ab. 3 1 and 2 4 (placebo.sh. or controlled study.ab. or random*.ti,ab. or trial*.ti,ab. or ((singl* or doubl* or trebl* or tripl*) adj3 (blind* or mask*)).ti,ab.) not (animals not (humans and animals)).sh. 5 3 and 4

Appendix 4. ISI Web of Science search strategy

#1 TS=(glutamin* or dipeptid* or L?glutamin*) #2 TS=(critical* SAME ill*) or TS=supplement* or TI=infect* #3 TS=(random* or (trial* SAME (clinical or controlled))) or TS=(prospective or multicenter or placebo*) or TS=((blind* or mask*) SAME (single or double or triple or treble)) #4 #1 or #2 or #3

Appendix 5. Study characteristics, quality assessment and data extraction form

Study characteristics

| Trial characteristics | |

| First author/year | |

| Journal/conference proceedings | |

| Single centre/multicentre | |

| RCT/quasi/CCT | |

| Participants | |

| Location | |

| Period of study | |

| Age (mean, median, range, etc.) | |

| Disease status/type, etc. | |

| Inclusion criteria | |

| Exclusion criteria | |

| Interventions | |

| Timing of intervention | |

| Groups | |

| Assessed | |

| Outcomes | |

| Length of follow‐up | |

| Main outcomes | |

| Other outcomes | |

| Other | |

Methodological quality assessment

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | |

| State here reasons for grading | Risk of bias |

| |

Low |

| High | |

| Unclear | |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | |

| State here reasons for grading | Risk of bias |

| Low | |

| High | |

| Unclear | |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | |

| State here reasons for grading | Risk of bias |

| Low | |

| High | |

| Unclear | |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | |

| State here reasons for grading | Risk of bias |

| Low | |

| High | |

| Unclear | |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | |

| State here reasons for grading | Risk of bias |

| Low | |

| High | |

| Unclear | |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | |

| State here reasons for grading | Risk of bias |

| Low | |

| High | |

| Unclear | |

| Other bias | |

| State here reasons for grading | Risk of bias |

| Low | |

| High | |

| Unclear | |

|

Intention‐to‐treat An intention‐to‐treat analysis is one in which all the participants in a trial are analysed according to the intervention to which they were allocated, whether they received it or not | |

| All participants entering trial | |

| 15% or fewer excluded | |

| More than 15% excluded | |

| Not analysed as ‘intention‐to‐treat’ | |

| Unclear | |

| Other | |

Data extraction form

| Outcomes relevant to your review | Reported in paper | Subgroups | |

| Primary outcomes | 1. Critically ill patients 2. Surgical patients 3. Enteral glutamine supplementation 4. Parenteral glutamine supplementation 5. Patients with malignant disease 6. Patients with non‐malignant disease |

||

| Outcome 1: Number of infectious complications | Yes/No | ||