Abstract

Background

Problem alcohol use is common among people who use illicit drugs (PWID) and is associated with adverse health outcomes. It is also an important factor contributing to a poor prognosis among drug users with hepatitis C virus (HCV) as it impacts on progression to hepatic cirrhosis or opioid overdose in PWID.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness of psychosocial interventions to reduce alcohol consumption in PWID (users of opioids and stimulants).

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Drugs and Alcohol Group trials register, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, and PsycINFO, from inception up to August 2017, and the reference lists of eligible articles. We also searched: 1) conference proceedings (online archives only) of the Society for the Study of Addiction, International Harm Reduction Association, International Conference on Alcohol Harm Reduction and American Association for the Treatment of Opioid Dependence; and 2) online registers of clinical trials: Current Controlled Trials, ClinicalTrials.gov, Center Watch and the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials comparing psychosocial interventions with other psychosocial treatment, or treatment as usual, in adult PWIDs (aged at least 18 years) with concurrent problem alcohol use.

Data collection and analysis

We used the standard methodological procedures expected by Cochrane.

Main results

We included seven trials (825 participants). We judged the majority of the trials to have a high or unclear risk of bias.

The psychosocial interventions considered in the studies were: cognitive‐behavioural coping skills training (one study), twelve‐step programme (one study), brief intervention (three studies), motivational interviewing (two studies), and brief motivational interviewing (one study). Two studies were considered in two comparisons. There were no data for the secondary outcome, alcohol‐related harm. The results were as follows.

Comparison 1: cognitive‐behavioural coping skills training versus twelve‐step programme (one study, 41 participants)

There was no significant difference between groups for either of the primary outcomes (alcohol abstinence assessed with Substance Abuse Calendar and breathalyser at one year: risk ratio (RR) 2.38 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.10 to 55.06); and retention in treatment, measured at end of treatment: RR 0.89 (95% CI 0.62 to 1.29), or for any of the secondary outcomes reported. The quality of evidence for the primary outcomes was very low.

Comparison 2: brief intervention versus treatment as usual (three studies, 197 participants)

There was no significant difference between groups for either of the primary outcomes (alcohol use, measured as scores on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) or Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST) at three months: standardised mean difference (SMD) 0.07 (95% CI ‐0.24 to 0.37); and retention in treatment, measured at three months: RR 0.94 (95% CI 0.78 to 1.13), or for any of the secondary outcomes reported. The quality of evidence for the primary outcomes was low.

Comparison 3: motivational interviewing versus treatment as usual or educational intervention only (three studies, 462 participants)

There was no significant difference between groups for either of the primary outcomes (alcohol use, measured as scores on the AUDIT or ASSIST at three months: SMD 0.04 (95% CI ‐0.29 to 0.37); and retention in treatment, measured at three months: RR 0.93 (95% CI 0.60 to 1.43), or for any of the secondary outcomes reported. The quality of evidence for the primary outcomes was low.

Comparison 4: brief motivational intervention (BMI) versus assessment only (one study, 187 participants)

More people reduced alcohol use (by seven or more days in the past month, measured at six months) in the BMI group than in the control group (RR 1.67; 95% CI 1.08 to 2.60). There was no difference between groups for the other primary outcome, retention in treatment, measured at end of treatment: RR 0.98 (95% CI 0.94 to 1.02), or for any of the secondary outcomes reported. The quality of evidence for the primary outcomes was moderate.

Comparison 5: motivational interviewing (intensive) versus motivational interviewing (one study, 163 participants)

There was no significant difference between groups for either of the primary outcomes (alcohol use, measured using the Addiction Severity Index‐alcohol score (ASI) at two months: MD 0.03 (95% CI 0.02 to 0.08); and retention in treatment, measured at end of treatment: RR 17.63 (95% CI 1.03 to 300.48), or for any of the secondary outcomes reported. The quality of evidence for the primary outcomes was low.

Authors' conclusions

We found low to very low‐quality evidence to suggest that there is no difference in effectiveness between different types of psychosocial interventions to reduce alcohol consumption among people who use illicit drugs, and that brief interventions are not superior to assessment‐only or to treatment as usual. No firm conclusions can be made because of the paucity of the data and the low quality of the retrieved studies.

Plain language summary

Which talking therapies work for people who use drugs and also have alcohol problems?

Review question

We wanted to see whether talking therapies reduce drinking in adult users of illicit drugs (mainly opioids and stimulants). We also wanted to find out whether one type of therapy is more effective than another.

Background

Drinking alcohol above the low‐risk drinking limits can lead to serious alcohol use problems or disorders. Drinking above those limits is common in people who also have problems with other drugs. It worsens their physical and mental health. Talking therapies aim to identify an alcohol problem and motivate an individual to do something about it. Talking therapies can be given by trained doctors, nurses, counsellors, psychologists, etc. Talking therapies may help reduce alcohol use but we wanted to find out if they can help people who also have problems with other drugs.

Search date: the evidence is current to August 2017.

Study characteristics

We found seven studies that examined five talking therapies among 825 people with drug problems.

Cognitive‐behavioural coping skills training (CBCST) is a talking therapy that focuses on changing the way people think and act.

The twelve‐step programme is based on theories from Alcoholics Anonymous and aims to motivate the person to develop a desire to stop using drugs or alcohol.

Motivational interviewing (MI) helps people to explore and resolve doubts about changing their behaviour. It can be delivered in group, individual and intensive formats.

Brief motivational interviewing (BMI) is a shorter MI that takes 45 minutes to three hours.

Brief interventions are based on MI but they take only five to 30 minutes and are often delivered by a non‐specialist.

Six of the studies were funded by the National Institutes for Health or by the Health Research Board; one study did not report its funding source.

Key results

We found that the talking therapies led to no differences, or only small differences, for the outcomes assessed. These included abstinence, reduced drinking, and substance use.

One study found that there may be no difference between CBCST and the twelve‐step programme.

Three studies found that there may be no difference between brief intervention and usual treatment.

Three studies found that there may be no difference between MI and usual treatment or education only.

One study found that BMI is probably better at reducing alcohol use than usual treatment (needle exchange), but found no differences in other outcomes.

One study found that intensive MI may be somewhat better than standard MI at reducing severity of alcohol use disorder among women, but not among men and found no differences in other outcomes.

It remains uncertain whether talking therapies reduce alcohol and drug use in people who also have problems with other drugs. High‐quality studies are missing and are needed.

Quality of evidence

The quality of the evidence was moderate for brief and intensive motivational interviewing, but low for brief interventions and standard motivational interviewing, and very low for CBCST versus twelve‐step programme.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Problem alcohol use is common among people who use illicit drugs (PWID) and is associated with adverse health outcomes, which have physical, psychological and social implications (Staiger 2013). Meta‐analyses of US clinical trial data, performed by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), found alcohol use disorders (AUDs) in 38% and 45% of opiate‐ and stimulant‐using treatment seekers, respectively (Hartzler 2010; Hartzler 2011). The prevalence of 'heavy drinking' or diagnosis of alcohol use disorder among PWID enrolled in methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) ranges from 13% to 28% (Chen 2011; Klimas 2015a; Klimas 2017b). In comparison, cross‐sectional studies have reported prevalence rates of 33% to 50% in this setting (Islam 2013; Wurst 2011). Another study found that 28% of heroin users and methadone‐ or codeine‐maintained patients consumed more than 40g of alcohol daily (Backmund 2003).

Problem alcohol use is an expression that represents a spectrum of distinct drinking patterns (i.e. hazardous, harmful and dependent drinking). Hazardous drinking "is likely to result in harm should present habits persist" (Babor 2001), whereas harmful drinking, which is a diagnosis given in the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD‐10) (WHO 1993), "causes harm to the health (physical or mental) of the individual" without the presence of dependence (Babor 2001). Hazardous drinking that becomes severe is assigned the medical diagnosis of alcohol use disorder (AUD) under the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM‐5), or ICD‐10 criteria (WHO 1993). Eleven diagnostic criteria describe the DSM‐5 AUD diagnosis, which is determined by the presence of any two of the 11 criteria during the last year. Based on the number of criteria fulfilled, an AUD can be mild (2 to 3), moderate (4 to 5) or severe (more than 6). According to the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, “binge drinking” refers to a pattern of drinking wherein blood alcohol level is regularly at or above 0.08% (NIAAA 2004). This corresponds to five or more standard drinks in males and four or more drinks in females within an approximate two‐hour period.

In PWID, binge drinking is associated with increased all‐cause mortality (Johnson 2015), while daily drinking is associated with increased incidence of HIV seroconversion (Young 2016). In addition, problematic alcohol use in PWID is associated with unsafe sex, incarceration, and the use of more than one drug (Maynié‐François 2016). Alcohol use in PWID is also associated with increased risk of fatal overdose (Shah 2008); however, heavy drinking is not associated with all‐cause or overdose mortality among people receiving opioid agonist treatment (OAT) (Klimas 2017a). PWID are at high risk of liver disease resulting from hepatitis C virus infection because of its high prevalence in this population (Smyth 1998). Problem alcohol use is an important factor contributing to a poor prognosis among people with hepatitis C virus as it impacts on progression to hepatic cirrhosis, increased hepatitis C virus‐RNA levels or fatal opiate overdose in opiate users (Du 2012; White 1999). However, alcohol may have little influence on response to hepatitis C treatment (Tsui 2017). Nevertheless, Teplin and colleagues noted that PWID have higher rates of mood, anxiety and personality disorders, all of which are exacerbated by alcohol use (Teplin 2007).

There exists some evidence that alcohol may have a negative impact on outcomes of substance‐use disorder treatment (Byrne 2011; Gossop 2000). For example, a study of 114 participants enrolled in OAT found that drinking was associated with heroin and cocaine craving and actual use (Preston 2016). Sadly, in some countries substance‐use disorder treatment programmes do not accept patients with AUDs who are receiving OAT, because this is viewed as a violation of their “drug free” policies (Harris 2010). However, these precautions diminish patients’ access to treatment and are not justified, nor evidence‐based, as shown in previous demonstration projects (Kipnis 2001). In PWID, initiation of OAT decreases initiation of heavy drinking (Klimas 2016). While short‐term OAT (four weeks' duration) decreases alcohol consumption (Caputo 2002), longer‐term OAT (two years' duration) has been shown to increase alcohol consumption, potentially as a substitute substance (Dobler‐Mikola 2005).

The emerging understanding of a high prevalence of problem alcohol use among current or former PWID, allied to the clear health implications of this problem for this population, necessitates a public health response to this issue.

Description of the intervention

Psychosocial interventions are best described as "psychologically‐based interventions aimed at reducing consumption behaviour or alcohol‐related problems" (Anderson 2004; Kaner 2018), that exclude any pharmacological treatments. The term refers to a heterogeneous collection of interventions, which vary depending on:

theoretical underpinnings (e.g. psychodynamic, behavioural, motivational);

duration or intensity (e.g. brief, extended);

setting (e.g. primary‐care based, inpatient);

mode of delivery (e.g. group, individual, web‐based); or

treatment goals (e.g. abstinence oriented, harm reduction).

To date, many psychosocial interventions specifically designed to address problem alcohol use have been described. The most frequently used interventions include: motivational interviewing (MI), cognitive‐behavioural therapy (CBT), psychodynamic approaches, screening and brief interventions (SBIs), family therapy, drug counselling, 12‐step programmes, therapeutic community (TC) and vocational rehabilitation (VR).

MI is a client‐centred approach, but in contrast to its non‐directive Rogerian origins, it is a directive therapy system. A central role is played by the client's motivation and readiness to change. Change within this approach is facilitated over a series of stages (Prochaska 1992). Relapse is not viewed as a failure to maintain healthy behaviour, but rather as a part of the process of change (Miller 2004).

CBT draws upon the principles of learning theory. Change in addictive behaviour is approached through altering irrational assumptions, coping skills training or other behavioural exercises. This therapy often deals with the identification and prevention of triggers contributing to drug use. Among the modern approaches utilising such behavioural techniques are Relapse Prevention (Marlatt 1996), Contingency Management (Budney 2001), and the Community Reinforcement Approach, which combines both contingency management and positive reinforcement for non‐drinking behaviours (Hunt 1973).

Psychodynamic approaches are based on the assumptions of psychoanalytic theory, which focuses on addressing inner conflict, childhood trauma or problematic relationship themes. Such approaches include a range of different methods designed to deal with the underlying conflict (e.g. interpersonal therapy, supportive‐expressive techniques, etc.) (Crits‐Christoph 1999).

SBIs are time limited and therefore suitable for non‐specialist facilities. Usually, the length and intensity of the intervention is determined by the levels of risky alcohol consumption (i.e. screening results), and can range from a couple of minutes to several sessions (three to six). Each session includes the provision of information and advice (Babor 2001). Increasingly, brief interventions (BIs) are based on the principles and techniques of MI, so that the distinction between these two modalities is blurred in this regard.

Family therapy: the therapeutic change is achieved via intervening in the interaction between family members. Families are directly involved in a therapy session. The family therapist must be competent in eliciting the strengths and support of the wider family system. Frequently used family therapy models include multisystemic therapy and network therapy solution‐focused brief therapy (CSAT 2004).

Drug counselling: addiction is viewed as a chronic illness that has serious consequences to the individual's health and social functioning, in consonance with the 12‐step model (see below). Recovery includes spiritual components and attendance at fellowship meetings. The primary focus of this approach is to help the individual attain abstinence by promoting behavioural changes, including trigger avoidance, sport and other constructive activities. Both individual and group forms of drug counselling have been used in the largest collaborative cocaine treatment study (Crits‐Christoph 1999).

The 12‐step (facilitation) model emphasises the powerlessness of an individual over the addiction, which is seen as a disease, and the need for a spiritual recovery. The foundations of this approach lie in the 12 Steps and an accompanying document, 12 Traditions (Alcoholics Anonymous 1939). The largest of all 12‐step programmes is that of Alcoholics Anonymous (AA), and all other programmes (e.g. those of Narcotics Anonymous, Al‐Anon etc.) have evolved from it. AA meetings, besides the 12 steps, utilise well‐established therapeutic factors of group psychotherapy, such as group cohesiveness, interpersonal learning (i.e. sponsorship), peer pressure, etc.

TC is a long‐term (18‐ to 24‐month), drug‐free model of treatment, which usually runs in a residential form. This approach relies on the community itself, as the main therapeutic factor, and also on other factors, such as peer feedback, role‐modelling or recapitulation of the primary family experience. The community has a high degree of autonomy, is democratic and each member has a clearly defined role and responsibilities within the structure of TC. A structured regimen of daily activities in the TC often includes formal individual or group therapy sessions along with other educational and work activities (De Leon 2000; Staiger 2009).

VR employment is seen as an important element of successful rehabilitation from drug addiction and is often considered as one of its key indicators (Platt 1995). VR aims to increase the employability of PWID by developing their job interview skills or obtaining further qualifications. A necessary part of increasing ex‐users' access to the job market is linking with potential employers and addressing their concerns and prejudices related to PWID. An example of VR for unemployed individuals receiving methadone maintenance treatment is the customised employment supports model (Blankertz 2004).

How the intervention might work

Substantial evidence has described the value of psychosocial interventions in treating problem alcohol use.

A review by Raistrick and colleagues presented data on the effectiveness of many interventions, including screening, further assessment, BIs, more intensive treatments that can still be considered 'brief' and alcohol‐focused specialist treatments (Raistrick 2006). They reported mixed evidence on the longer‐term effects of BIs and whether extended BIs add anything to the effects of simple BIs.

The Mesa Grande project, which reviewed 361 controlled clinical trials (CCTs) (a three‐year update), found BIs to be the most strongly supported psychosocial treatment effective in treating AUDs (Miller 2002). These findings are supported by an Australian systematic review that found BIs to be effective in reducing alcohol consumption in drinkers without dependence or those with a low level of dependence (Shand 2003). Another meta‐analysis found the positive effect of BIs to be evident at the follow‐up points of three, six and 12 months, and these results were more apparent when dependent drinkers were excluded (Moyer 2002). Indeed, dependent drinkers have been excluded from much of this research, indicating that they are possibly unsuitable for BI and should be routinely referred to specialist treatment (Raistrick 2006).

While BIs are generally delivered across a range of settings, primary care has an important role in the delivery of BIs for problem alcohol use among PWID. BIs are well suited to primary care owing to their feasibility and ease of delivery in general settings by non‐specialist staff in a short period of time, and to individuals not actively seeking treatment (Kaner 2018; Raistrick 2006; Williams 2011). While primary care physicians believe these interventions are feasible, many face challenges incorporating them into care and often underestimate problem alcohol use in this population (McCombe 2016). In particular, patients receiving methadone maintenance treatment in primary care settings are not routinely screened for alcohol (Klimas 2015b).

The efficacy of primary care‐based interventions for people with problem alcohol use has been demonstrated in a Cochrane Review (Kaner 2018), although the authors judged the evidence as being of moderate quality and reported that longer counselling duration probably had little additional effect. Another systematic review of brief, multi‐contact behavioural counselling among adults attending primary care reported an average reduction of 13% to 34% in drinks per week (Whitlock 2004). However, a recent meta‐analysis of studies of adolescents and young adults showed that brief, alcohol‐targeted interventions decreased alcohol consumption, but had no effect on illicit drug use. In comparison, the same intervention targeted at alcohol and drugs decreased both behaviours (Tanner‐Smith 2015). Therefore, the evidence behind brief interventions for illicit drug use appears inconclusive (Saitz 2014).

There have also been new pilot studies published of psychosocial interventions for hazardous alcohol use among persons receiving OAT. One study found 88% of participants attempted to reduce their alcohol intake after the sessions, while 57% significantly reduced their alcohol use (Varshney 2016). Another study, Rosa 2015, also found a significant decrease in alcohol consumption after the intervention. Finally, an educational intervention to support primary care of problem alcohol use among PWID has been developed and process‐evaluated (Klimas 2014).

Thus, brief psychosocial interventions are feasible and potentially highly efficacious components of an overall public health approach to reducing problem alcohol use, although there is considerable variation in trials of effectiveness, and PWID from primary care settings are under‐represented in these trials (Kaner 2018; Whitlock 2004).

Because BIs have been developed and evaluated mainly in conventional general practice settings, it is not clear whether they can be effectively applied to excessive drinking among PWID, or whether new forms of intervention need to be developed and evaluated. Could the 'advice‐giving' form of BI be effective in PWID or are motivational techniques, in which the impetus for change comes from the user, more likely to be effective in this population?

Why it is important to do this review

The high prevalence and serious consequences of problem alcohol use among PWID highlights an opportunity for a Cochrane systematic review in this population. The question being asked in this review is also of importance because there are no other systematic reviews published that could help answer it.

Several narrative literature reviews have dealt with this question to date. The oldest of these reviews discussed six reports of four studies among methadone patients and saw some promise for contingency management procedures (Bickel 1987). A more recent review described the implications of combining behavioural and pharmacological treatments, which are effective in treating either alcohol‐ or drug‐use disorders alone, for the treatment of people who have both these disorders (Arias 2008). While pointing to the paucity of research specifically focused on the treatment of people with co‐occurring alcohol and other substance use disorders, the review concluded that successful treatment must take into account both alcohol‐ and drug‐use disorders. Similarly, a review on treatment of people seeking therapy primarily for alcohol problems, but who also used other drugs, concurred with this idea (Miller 1996). More recently, two narrative reviews examined the patterns of concurrent use among people in and out of the treatment for substance use disorders (Staiger 2013; Soyka 2015). Both reviews (Staiger 2013; Soyka 2015) concluded that while concurrent alcohol use is often "overlooked and underestimated" in drug treatment, no clear patterns have emerged and the literature remains inconclusive. Another narrative review calls for creation of a set of guidelines for screening and treatment of alcohol use in OAT participants, based on the high prevalence of problem alcohol use and limited alcohol treatment access in this patient population (Nolan 2016). It also concluded that there is no clinical evidence to justify denial of treatment for alcohol use disorders, or reduction of opioid agonist dose, in OAT participants.

Cochrane Reviews have so far examined the effectiveness of psychosocial interventions for stimulant, opiate and alcohol use disorders (Amato 2011a; Minozzi 2016; Lui 2008). Although other reviews and review protocols have targeted poly‐drug use, they concentrated either on specific populations, for example women and adolescents, or particular interventions, such as case management and MI, but not on 'alcohol‐specific' interventions (Dalsbø 2010; Hesse 2007; Smedslund 2011; Smith 2006; Terplan 2015; Thomas 2011). None of the published reviews on psychosocial interventions examined the effectiveness of alcohol‐specific interventions in PWID. The main problem driving the lack of quality studies in this area seems to flow from the administrative separation of drug problems from alcohol problems. This separation has led researchers to focus on one or the other but not on both. In the USA, the National Institutes of Health had planned to correct this separation by forming a new institute that covers both drugs and alcohol — the proposed National Institute of Substance Use and Addiction Disorders (NIH 2012) — although this plan was quickly abandoned.

The lack of systematic evaluation, together with the anticipated differences in the responsiveness of PWID to psychosocial interventions, provides additional reasons for conducting this review. In other words, the results of reviews on the effectiveness of psychosocial interventions among the general population might not be applicable to specific groups, such as PWID, because they may have a different responsiveness to psychosocial interventions (Nilsen 2010; Klimas 2012b). Several factors could possibly influence the responsiveness of PWID to treatment interventions (for example, stability of drug use, engagement with the service, concurrent personality disorders, etc). Evidence suggests that PWID with antisocial personality disorders are more likely to respond to rewarding than to punitive approaches (Messina 2003), and the use of more intensive psychosocial interventions is recommended in those who have achieved a sufficient degree of stability and compliance with a service regimen (Pilling 2010; Saitz 2015).

Moreover, it has been suggested that evidence on the effectiveness of many psychosocial interventions has been overestimated, that limitations of this evidence have been overlooked, and that results are difficult to generalise (McCambridge 2017). These criticisms further highlight the necessity of a comprehensive systematic review evaluating and consolidating the body of literature on various psychosocial interventions in PWID.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness of psychosocial interventions to reduce alcohol consumption in people who use illicit drugs (PWID) (users of opioids and stimulants).

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and controlled clinical trials (CCTs).

Types of participants

We included people who use illicit drugs (PWID), aged 18 years or more, attending a range of services (i.e. community, inpatient or residential, including receiving opioid agonist treatment). Problem drug use was defined according to the definition of the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, as "injecting drug use or long‐duration/regular use of opioids, cocaine and/or amphetamines" (EMCDDA 2008, page 10). This definition also encompasses other similar terms, for example substance use, misuse, abuse, dependence, addiction or people who use illicit drugs.

Only studies that defined participants as problem drug and alcohol users at randomisation were included. Studies including PWID without concurrent problem alcohol use were excluded. We excluded participants whose primary drug of use was alcohol.

Types of interventions

Experimental interventions: any psychosocial intervention that was described by the study's author(s) as such.

Control interventions: other psychosocial interventions that allowed for comparisons between different types of interventions (e.g. CBT, contingency management, family therapy, etc.), standard care, no intervention, waiting list, or any other non‐pharmacological therapy, including moderate drinking, assessment‐only.

We intended to exclude studies comparing psychosocial with pharmacological treatments. However, trials with two psychosocial arms in addition to pharmacological arms were exempted from this rule.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Alcohol use (reduction or stabilisation), as measured by either biological markers or self‐report tests

Retention in treatment (measured as number of people completing all treatment sessions, or retained at three months — for studies of brief interventions)

Secondary outcomes

Illicit drug use (changes in illicit drug use), as measured by either biological markers or self‐report tests

Alcohol‐related problems or harms, as represented by physical or mental health outcomes associated with problem alcohol use.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

For this second update of a previously published review update, we searched the following databases up to 3 August 2017.

Cochrane Drugs and Alcohol Review Group (CDAG) Specialised Register* (June 2014 to August 2017; 20 hits)

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL, July 2017, Issue 7) in the Cochrane Library

MEDLINE (PubMed) (June 2014 to August 2017)

Embase (Elsevier) (June 2014 to August 2017)

CINAHL EBSCO (June 2014 to August 2017)

PsycINFO (ProQuest) (June 2014 to August 2017)

* All trials from the CDAG Specialised Register can be found in the Cochrane Library by searching on SR‐ADDICTN.

Details of the previous search strategies are available in the previously published updates (Klimas 2012a; Klimas 2014b).

We searched the databases using a strategy developed incorporating the filter for the identification of RCTs (Higgins 2011), combined with selected medical subject heading (MeSH) terms and free‐text terms relating to alcohol use. The CDAG Information Specialist conducted the electronic searches of all the databases listed above except PsycINFO, which the first author of the review conducted. We adapted the MEDLINE search strategy for use with the other databases using the appropriate controlled vocabulary, as applicable. Since the initial search yielded several RCTs, we continued to use the RCT filter for subsequent database searches. We collated the results of the two sets of electronic searches into a single EndNote database.

The search strategies for all databases are shown in Appendix 1, Appendix 2, Appendix 3, Appendix 4 and Appendix 5.

For the 2017 update, we searched for ongoing clinical trials and unpublished studies via searches on the following websites:

www.controlled‐trials.com (search date: 17 May 2017);

www.clinicaltrials.gov (search date: 17 May 2017);

www.centrewatch.com (search date: 17 May 2017);

World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform, www.who.int/ictrp/en/ (search date: 17 May 2017).

Searching other resources

We also searched:

reference lists of articles considered eligible based on full report screening and other relevant papers;

conference proceedings (online archives only) of the Society for the Study of Addiction, International Harm Reduction Association, International Conference on Alcohol Harm Reduction and American Association for the Treatment of Opioid Dependence.

In addition, we contacted investigators and relevant trial authors seeking information about unpublished or incomplete trials.

All searches included non‐English language literature and we assessed any with English abstracts for inclusion. When we considered the studies likely to meet inclusion criteria, we obtained translations of any abstracts.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (JK, ChF) independently screened titles and abstracts and selected studies potentially relevant. We resolved any differences between selection lists by discussion with a third and fourth review author with respective thematic and methodological expertise (WC, CSMOG). We obtained full‐text copies of each potentially relevant paper, as well as full reports of references with inadequate information in order to definitively determine relevance. Two review authors (JK, ChF) independently re‐evaluated whether studies were eligible for the update or not, according to the inclusion criteria. A second opinion was not needed. We screened abstracts, full texts and extracted data using the Eppi Reviewer 4 software (Eppi 2017).

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (JK, ChF) independently extracted data from the full‐text reports using an electronic version of an amended data extraction form of the Cochrane Drug and Alcohol Review Group. We resolved disagreements by mutual discussion. We sought information on study participants, characteristics of experimental and control intervention, primary and secondary outcomes, funding and conflict of interest from reports of included studies.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We performed 'Risk of bias' assessments for RCTs and CCTs using the criteria recommended in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). The recommended approach for assessing risk of bias in studies included in a Cochrane Review is a two‐part tool addressing six specific domains (namely sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessor, incomplete outcome data and selective outcome reporting). The first part of the tool involves describing what was reported to have happened in the study. The second part of the tool involves assigning a judgement relating to the risk of bias for that entry in terms of high, low or unclear risk. To make these judgements we used the criteria indicated in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions adapted to the addiction field. See the table in Appendix 6 for details.

We addressed the domains of sequence generation and allocation concealment (avoidance of selection bias) using a single entry for each study.

Blinding of participants and providers was not possible for this kind of intervention. Moreover, knowledge of participation in a psychosocial intervention is part of the therapeutic effect; therefore, we think that lack of blinding of participants and personnel does not introduce bias in trials of psychosocial interventions. “In psychotherapy, it is impossible for the principle participants to be blind to the treatment used."(Beutler 2016, p.102) For this reason, we did not assess the risk of performance bias. We considered the blinding of outcome assessors (avoidance of detection bias) separately for objective outcomes (e.g. dropouts from therapy, substance use measured by urinalysis, participants relapsed at the end of follow‐up, participants engaged in further treatments), and subjective outcomes (e.g. duration and severity of signs and symptoms of withdrawal, individual self‐reported use of substance, side effects, social functioning as integration at school or at work, family relationship, etc.).

We considered incomplete outcome data (avoidance of attrition bias) for all outcomes with the exception of dropouts from therapy, which is usually the primary outcome measure in trials on addiction. We assessed this separately for results at the end of the study period, and for results at follow up.

Measures of treatment effect

For continuous data, we calculated mean differences (MDs), and standardised MDs (where appropriate) between the intervention and comparator groups, with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We present dichotomous outcomes as risk ratios (RRs), with 95% CIs.

Unit of analysis issues

We included only one multiarm trial, Nyamathi 2010, in the review and it was not included more than once in any of the comparisons. This study had three arms; of those, two were experimental (group and single format). We collapsed them into a single experimental group which we entered into a single comparison so they were not counted twice.

In accordance with the Cochrane Handbook (Higgins 2011), the actual sample sizes of included cluster‐randomised trials have been reduced by a design effect coefficient to their effective sample size.

Dealing with missing data

We contacted the authors of the seven original studies by email for missing data (April 2012; July 2016) and sent reminders after two weeks. To date, five study authors have responded and provided additional information.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We analysed heterogeneity by using the I² statistic and the Chi² test. Cut‐off points included an I² value greater than 50% and a P value for the Chi² test less than 0.1.

Assessment of reporting biases

We planned to further explore the potential for reporting bias using funnel plots if more than 10 RCTs were included (plotting the effect from each trial against the sample size or effect's standard error); however, this was not possible because only seven RCTs were identified.

Data synthesis

For comparisons of sufficiently similar studies, we used the random‐effects model. For the comparisons where we considered that no two studies were sufficiently similar to allow pooling of data, we reported the results of included studies individually for each trial. We used a fixed‐effect model if there was only one trial for each comparison.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

If sufficient information had been available, we had planned to conduct the following subgroup analyses:

types of psychosocial intervention (e.g. motivational versus behavioural or brief interventions);

length of the intervention (short, medium, extended).

We had also intended to conduct the following subgroup analyses, but did not due to there being insufficient data:

sustained benefit at six and 12 months after intervention;

gender differences;

single‐drug (alcohol) versus poly‐drug‐focused interventions;

single‐drug (alcohol) versus poly‐drug‐focused interventions that also address other health‐related behaviours.

Sensitivity analysis

If sufficient information had been available, we intended to conduct the following sensitivity analyses according to the following criteria:

excluding studies with a high risk of bias from the analysis: this decision was to be based on a predefined cut‐off score (i.e. studies judged to be at high risk of bias for three or more domains, including selection bias, were to be excluded);

excluding CCTs.

However, we did not perform sensitivity analyses because of insufficient information.

'Summary of findings' tables

We assessed the overall quality of the evidence for the primary outcomes using the GRADE system for grading the quality of evidence (Schunemann 2013), which takes into account issues not only related to internal validity but also to external validity, such as directness, consistency, imprecision of results and publication bias. The 'Summary of findings' tables present the main findings of a review in a transparent and simple tabular format. In particular, they provide key information concerning the quality of evidence, the magnitude of effect of the interventions examined and the sum of available data on the main outcomes.

The GRADE system uses the following criteria for assigning grades of evidence.

High quality: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect.

Moderate quality: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate. The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different.

Low quality: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited. The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect

Very low quality: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate. The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect.

Grading of the quality of evidence is decreased for the following reasons.

Serious (‐1) or very serious (‐2) study limitations due to risk of bias.

Serious (‐1) or very serious (‐2) inconsistency between study results.

Some (‐1) or major (‐2) uncertainty about directness (the correspondence between the population, the intervention, or the outcomes measured in the studies actually found and those under consideration in our systematic review).

Serious (‐1) or very serious (‐2) imprecision of the pooled estimate.

Publication bias strongly suspected (‐1).

Consumer participation

We sought consumer participation in the preparation of the protocol and the original review: a) the first review author (JK) is a member of the Cochrane Consumers Network, b) the Cochrane Consumers Network was approached to assist with the plain language summary of the review, and c) one of the co‐authors of this review (EK) contributed to consumer consultation during the protocol and review development, as he was a practicing clinician in a healthcare facility with a high prevalence of this problem.

Results

Description of studies

See Characteristics of included studies, Characteristics of excluded studies and Characteristics of studies awaiting classification.

Results of the search

This is an update of a Cochrane Review first published in 2012 (Klimas 2012a), and updated in 2014 (Klimas 2014b). In the first version of our review, we retrieved a total of 7207 records from the initial search of the Cochrane Drugs and Alcohol Review Group (CDAG) Register, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), PubMed, Embase, CINAHL and PsycINFO. Removing duplicates left 5548 records. After screening titles and abstracts, we identified 25 potentially eligible studies; we excluded 18 full‐text reports and included seven reports which described four randomised controlled trials (RCTs). We found no additional studies through reference checking.

For the 2014 update, we retrieved a total of 1836 records from a more up‐to‐date search of the CDAG Register, CENTRAL, PubMed, Embase, CINAHL and PsycINFO. Removing duplicates left 960 records. After screening titles and abstracts we identified 16 potentially eligible records and included one record (Feldman 2013). This record was a 2013 correction of Feldman 2013, a paper we included in the first version of this review (Klimas 2012a).

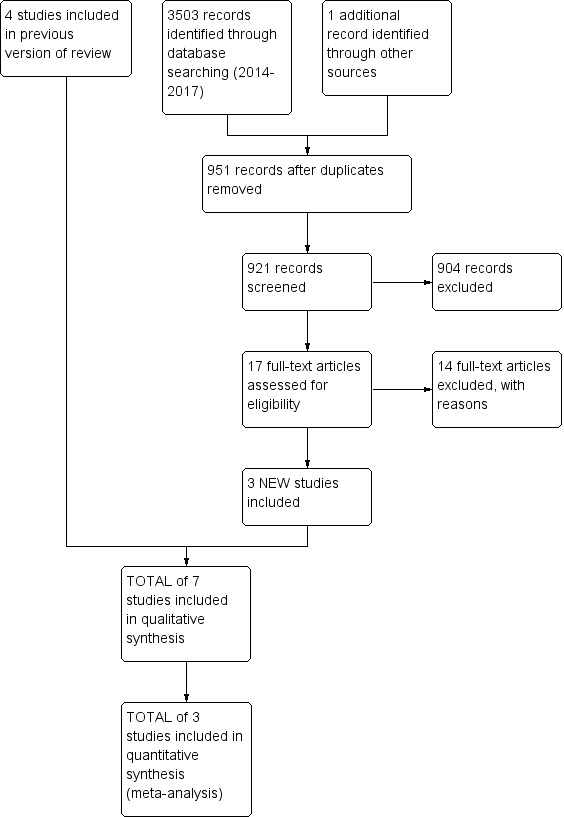

For this 2017 update, we retrieved a total of 3503 records from a more up‐to‐date search of the CDAG Register, CENTRAL, PubMed, Embase, CINAHL and PsycINFO. We identified one additional study through other sources. Removing duplicates left 921 records. After screening titles and abstracts we identified 17 potentially eligible studies; we excluded 14 full‐text reports and included three new RCTs (Darker 2016; Feldman 2013; Henihan 2016). Four studies are awaiting classification (Aharonovich 2017; Poblete 2017; Staiger 2009; Thapaliya 2017). A PRISMA (Moher 2009) flowchart of study selection for this review update is shown in Figure 1.

1.

Study flow diagram for the 2017 review update: previous studies incorporated into results of new literature search

Included studies

We included seven studies (825 participants) in this review.

Study designs

Five studies were parallel RCTs and two were cluster‐RCTs (Darker 2016; Henihan 2016)

Participants

Participants included 825 people who use illicit drugs (PWID). One multiarm trial included 122 participants (Carroll 1998), however, from this study only 41 participants from two psychosocial therapy arms were considered for this review. The mean age of participants was 38.6 years, and 28% were female.

Intervention

The studies assessed the effectiveness of eight psychosocial interventions: cognitive‐behavioural coping skills training (CBCST), twelve‐step facilitation (TSF) programme, brief intervention (BI), motivational interviewing (MI) (group based), MI (individual), educational hepatitis health promotion (HHP), brief motivational interviewing (BMI), and MI (intensive, group based). CBCST and TSF involved 16 individual sessions, twice weekly, over 12 weeks. BI involved one session that lasted approximately 15 minutes. MI (group and single) and HHP were delivered over three 60‐minute sessions, spaced two weeks apart. BMI included two therapist sessions, one month apart; the first session was 60 minutes long and the second session was 30 to 45 minutes long. MI (intensive, group based) involved a total of nine 50‐minute sessions, with three sessions being delivered each week (versus one 90‐minute session of standard MI and eight 60‐minute nutrition sessions).

Types of comparisons and setting

CBCST versus TSF in an outpatient clinic (Carroll 1998)

BI versus treatment as usual in an opioid agonist clinic (Darker 2016)

BI versus treatment as usual in an outpatient clinic with/without opioid agonist treatment (Feldman 2013)

BI versus treatment as usual in a primary care setting (Henihan 2016)

MI versus HHP in an opioid agonist clinic (Nyamathi 2010)

BMI versus assessment‐only in a needle exchange programme (Stein 2002)

MI intensive (group) versus MI (group) in an outpatient substance use treatment facility (Korcha 2014)

Country

Four studies were conducted in the USA, two in Ireland, and one in Switzerland.

Duration of the trials

Duration of the trials ranged from one to 12 weeks (mean 3.9 weeks), plus various follow‐ups. Between one and 16 sessions were offered to participants (mean 4.7, providing from three minutes to 16 hours of treatment time).

Funding

Six of the studies were funded by the National Institutes for Health or by the Health Research Board; one study did not report its funding source. Four studies reported no competing interests (Darker 2016; Feldman 2013; Henihan 2016; Nyamathi 2010), while three studies did not provide information about conflicts of interests (Carroll 1998; Korcha 2014; Stein 2002).

See the Characteristics of included studies table for more details.

Excluded studies

We excluded 46 studies (17 in 2012, 15 in 2014, and 14 in 2017) that did not meet the criteria for inclusion in this review; for more information see the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

We considered grounds for exclusion as follows: type of intervention not in the inclusion criteria (no studies); type of participants not in the inclusion criteria (37 studies); types of outcomes not in the inclusion criteria (six studies); study design not in the inclusion criteria (three studies).

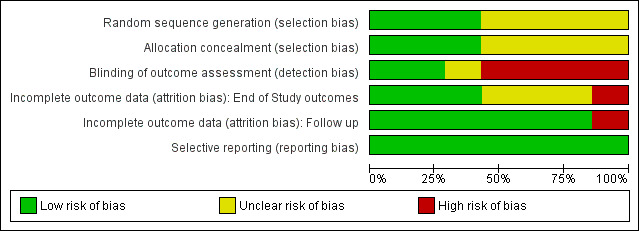

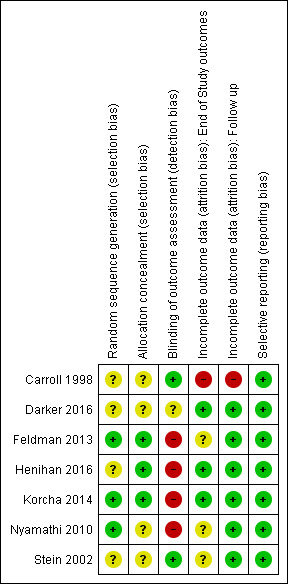

Risk of bias in included studies

All the studies were RCTs. For a summary of the our judgements regarding risk of bias for each domain in each included study and across studies, see Figure 2 and Figure 3. See the Characteristics of included studies table for more detailed information.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Random sequence generation

We judged random sequence generation to be adequate in three studies (for two studies, this was based on unpublished information obtained via email communication with the study authors), and unclear in the remaining trials.

Allocation concealment

We judged three studies as being at low risk of bias, and the remaining trials as having unclear risk of bias.

Blinding

Detection bias

Objective outcomes

None of the included studies reported objective outcomes, so we did not assess risk of detection bias for these outcomes.

Subjective outcomes

We assessed the following outcome for this 'Risk of bias' domain: abstinence or use of a substance, as measured by self‐reported or interviewer‐administered questionnaires. Two studies (27%) specified that outcome assessors were blinded and we judged these studies to be at low risk of bias. Four studies reported that the outcome assessor was not blinded and we judged these to be at high risk of bias; for two of them, this was unpublished information obtained via email communication with the study authors. We judged one study to have an unclear risk of bias because it did not specify the blindness of outcome assessor.

Incomplete outcome data

End‐of‐study outcomes

With the exception of retention in treatment, four studies measured end‐of‐study outcomes. We judged three to be at low risk of bias because of low or balanced dropout rates across all groups. We judged one study to be at high risk of bias because the dropout rates were not balanced across all groups: "the psychotherapy groups had significantly lower retention rates than the medication [disulfiram] groups" (Carroll 1998), although the difference between the two psychotherapy arms included in the present review was not significant (70% versus 78%), see Analysis 1.4.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Cognitive‐behavioural coping skills training (CBCST) versus twelve‐step facilitation (TSF) programme, Outcome 4 Retention ‐ end of treatment (unpublished).

Follow‐up outcomes

With the exception of retention in treatment, we judged six studies to be at low risk of attrition bias because few participants (less than 10%) withdrew from the studies, or because there was a high rate of drop‐out but percentages were balanced across intervention groups, and reasons for withdrawal were provided or authors performed an intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis. We judged one study to be at high risk of bias because of a high dropout rate that was unbalanced across groups.

Selective reporting

All studies reported on the primary outcomes pre‐specified in the methods sections of the full reports. See Figure 2 and Figure 3.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4; Table 5

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Cognitive‐behavioural coping skills training (CBCST) compared to twelve‐step facilitation (TSF) programme to reduce alcohol consumption in people who use illicit drugs (PWID).

| Cognitive‐behavioural coping skills training (CBCST) compared to twelve‐step facilitation (TSF) programme to reduce alcohol consumption in PWID | ||||||

| Patient or population: concurrent problem alcohol and illicit drug users Setting: substance use treatment centre Intervention: cognitive‐behavioural coping skills training (CBCST) Comparison: twelve‐step facilitation (TSF) programme | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with twelve‐step facilitation (TSF) programme | Risk with cognitive‐behavioural coping skills training (CBCST) | |||||

| Maximum number of weeks of consecutive alcohol abstinence during treatment assessed with: Substance abuse calendar and breathalyser Scale from: 0 to 12 Follow‐up: 12 weeks | The mean maximum number of weeks of consecutive alcohol abstinence during treatment was 1.8 weeks | MD 0.4 weeks higher (1.14 lower to 1.94 higher) | ‐ | 41 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 2 | |

| Number of participants achieving 3 or more weeks of consecutive alcohol abstinence during treatment assessed with: Substance abuse calendar and breathalyser Follow‐up: 1 year | Study population | RR 1.96 (0.43 to 8.94) | 41 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 2 | ||

| 111 per 1,000 | 218 per 1,000 (48 to 993) | |||||

| Alcohol abstinence assessed with: Substance abuse calendar and breathalyser Follow‐up: 1 year | Study population | RR 2.38 (0.10 to 55.06) | 41 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 2 | ||

| 0 per 1,000 | 0 per 1,000 (0 to 0) | |||||

| Retention ‐ end of treatment Assessed with: number of participants completing all treatment sessions | Study population | RR 0.89 (0.62 to 1.29) | 41 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 2 | ||

| 778 per 1,000 | 692 per 1,000 (482 to 1,000) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; MD: mean difference; PWID: people who use illicit drugs | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Downgraded one level for risk of bias: incomplete outcome data.

2 Downgraded two levels for imprecision: only one study with very few participants included in comparison.

Summary of findings 2. Brief intervention (BI) compared to treatment as usual (TAU) to reduce alcohol consumption in PWID.

| Brief intervention (BI) compared to treatment as usual (TAU) to reduce alcohol consumption in PWID | ||||||

| Patient or population: concurrent problem alcohol and illicit drug users Setting: opioid agonist treatment clinic, outpatient clinic with/without opioid agonist treatment, and primary care setting Intervention: brief intervention (BI) Comparison: treatment as usual (TAU) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with treatment as usual (TAU) | Risk with Brief intervention (BI) | |||||

| Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) or Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST) scores Follow‐up: 3 months | The mean alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) or Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST) score was 0 | SMD 0.07 higher (0.24 lower to 0.37 higher)4 | ‐ | 170 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 | |

| Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) scores Follow‐up: 9 months | The mean alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) scores was 11.6 | MD 2.3 higher (0.58 lower to 5.18 higher) | ‐ | 110 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 3 | |

| Number of drinks per week Assessed with: unreported Follow‐up: 3 months | The mean number of drinks per week was 16.3 | MD 0.7 higher (3.85 lower to 5.25 higher) | ‐ | 110 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 3 | |

| Number of drinks per week Assessed with: unreported Follow‐up: 9 months | The mean number of drinks per week at 9 months was 18.7 | MD 0.3 lower (4.79 lower to 4.19 higher) | ‐ | 110 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 3 | |

| Decreased alcohol use assessed with: 1st question from the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: How often do you have a drink containing alcohol? Follow‐up: 3 months | Study population | RR 1.13 (0.67 to 1.93) | 110 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 3 | ||

| 314 per 1,000 | 355 per 1,000 (210 to 605) | |||||

| Decreased alcohol use assessed with: 1st question from the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: How often do you have a drink containing alcohol? Follow‐up: 9 months | Study population | RR 1.09 (0.62 to 1.92) | 110 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 3 | ||

| 294 per 1,000 | 321 per 1,000 (182 to 565) | |||||

| Retention Assessed with: unpublished and published data Follow‐up: 3 months | Study population | RR 0.94 (0.78 to 1.13) | 190 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 | ||

| 784 per 1,000 | 713 per 1,000 (611 to 831) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; MD: mean difference;SMD: standardised mean difference; PWID: people who use illicit drugs | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Downgraded one level for risk of bias: high risk of detection bias (no blinding of outcome assessor, subjective outcomes).

2 Downgraded one level for imprecision: only three studies with relatively few participants included in comparison.

3 Downgraded one level for imprecision: only one study with relatively few participants included in comparison.

4 The result corresponds to a small, statistically insignificant difference.

Summary of findings 3. Motivational interviewing (MI) compared to treatment as usual (TAU) or educational intervention only to reduce alcohol consumption in PWID.

| Motivational interviewing (MI) compared to treatment as usual (TAU) or educational intervention only to reduce alcohol consumption in PWID | ||||||

| Patient or population: concurrent problem alcohol and illicit drug users Setting: opioid agonist clinics and outpatient clinic with/without opioid agonist treatment Intervention: motivational interviewing (MI) Comparison: treatment as usual (TAU) or educational intervention only | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with treatment as usual (TAU) or educational intervention only | Risk with Motivational interviewing (MI) | |||||

| Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) or Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST) scores Follow‐up: 3 months | The mean alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) or Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST) scores was 0 | SMD 0.04 higher (‐0.29 lower to 0.37 higher)4 | ‐ | 141 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 | |

| Number of standard drinks consumed per day over the last 30 days Assessed with: counts Follow‐up: 6 months | The mean number of standard drinks consumed per day over the last 30 days was 3.9 | MD 0.2 lower (1.76 lower to 1.36 higher) | ‐ | 225 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 2 3 | |

| Greater than 50% reduction in number of standard drinks consumed per day over the last 30 days Assessed with: timeline follow back Follow‐up: 6 months | Study population | RR 1.01 (0.77 to 1.31) | 256 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 2 3 | ||

| 494 per 1,000 | 499 per 1,000 (381 to 647) | |||||

| Abstinence from alcohol over the last 30 days Assessed with: timeline follow back Follow‐up: 6 months | Study population | RR 0.93 (0.57 to 1.50) | 256 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 2 3 | ||

| 230 per 1,000 | 214 per 1,000 (131 to 345) | |||||

| Retention ‐ end of treatment Assessed with: number of people who completed all treatment sessions | Study population | RR 0.96 (0.87 to 1.06) | 256 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 2 3 | ||

| 885 per 1,000 | 850 per 1,000 (770 to 938) | |||||

| Retention Follow‐up: 3 months | Study population | RR 0.93 (0.60 to 1.43) | 160 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 2 3 | ||

| 738 per 1,000 | 671 per 1,000 (553 to 811) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; MD: mean difference; PWID: people who use illicit drugs | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Downgraded one level for imprecision: only two studies with relatively few participants included in comparison.

2 Downgraded one level for risk of bias: high risk of selection and detection bias (subjective outcomes).

3 Downgraded one level for imprecision: only one study with relatively few participants included in comparison.

4 The result corresponds to a small, statistically insignificant difference.

Summary of findings 4. Brief motivational interviewing (BMI) compared to assessment‐only to reduce alcohol consumption in PWID.

| Brief motivational interviewing (BMI) compared to assessment‐only to reduce alcohol consumption in PWID | ||||||

| Patient or population: concurrent problem alcohol and illicit drug users Setting: addiction clinic Intervention: brief motivational interviewing (BMI) Comparison: assessment‐only | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with assessment‐only | Risk with Brief motivational interviewing (BMI) | |||||

| Number of days with alcohol use Assessed with: timeline follow back Scale from: 0 to 31 Follow‐up: 6 months | The mean number of days with alcohol use was 9.1 days | MD 1.5 days lower (4.56 lower to 1.56 higher) | ‐ | 187 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | |

| 25% reduction of drinking days in the past 30 days Assessed with: timeline follow back Follow‐up: 6 months | Study population | RR 1.23 (0.96 to 1.57) | 187 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | ||

| 522 per 1,000 | 642 per 1,000 (501 to 819) | |||||

| 50% reduction of drinking days in the past 30 days Assessed with: timeline follow back Follow‐up: 6 months | Study population | RR 1.27 (0.96 to 1.68) | 187 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | ||

| 457 per 1,000 | 580 per 1,000 (438 to 767) | |||||

| 7 or more drinking days' reduction in the past 30 days Assessed with: timeline follow back Follow‐up: 6 months | Study population | RR 1.67 (1.08 to 2.60) | 187 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | ||

| 239 per 1,000 | 399 per 1,000 (258 to 622) | |||||

| Retention ‐ end of treatment Assessed with: number of people who completed all treatment sessions | Study population | RR 0.98 (0.94 to 1.02) | 190 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | ||

| 968 per 1,000 | 949 per 1,000 (910 to 988) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; MD: mean difference; PWID: people who use illicit drugs | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Downgraded one level for imprecision: only one study with relatively few participants included in comparison.

Summary of findings 5. Motivational interviewing intensive (MII) compared to motivational interviewing (MI) to reduce alcohol consumption in PWID.

| Motivational interviewing intensive (MII) compared to motivational interviewing (MI) to reduce alcohol consumption in PWID | ||||||

| Patient or population: concurrent problem alcohol and illicit drug users Setting: an outpatient substance use disorder treatment facility Intervention: motivational interviewing intensive (MII) Comparison: motivational interviewing (MI) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with motivational interviewing (MII) | Risk with Motivational interviewing intensive (MI) | |||||

| Addiction Severity Index alcohol score Assessed with: ASI Follow‐up: 2 months | The mean addiction Severity Index alcohol score was 0.11 | MD 0.03 higher (0.02 lower to 0.08 higher) | ‐ | 163 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 | |

| Addiction Severity Index alcohol score Assessed with: ASI Follow‐up: 4 months | The mean addiction Severity Index alcohol score was 0.16 | MD 0.01 lower (0.06 lower to 0.04 higher) | ‐ | 163 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 | |

| Addiction Severity Index alcohol score assessed with: ASI Follow‐up: 6 months | The mean addiction Severity Index alcohol score was 0.16 | MD 0.02 lower (0.07 lower to 0.03 higher) | ‐ | 163 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 | |

| Retention ‐ end of treatment Assessed with: number of people who completed all treatment sessions | Study population | RR 17.63 (1.03 to 300.48) | 163 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 | ||

| 0 per 1,000 | 0 per 1,000 (0 to 0) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; OR: Odds ratio; PWID: people who use illicit drugs | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Downgrared one level for risk of bias: high risk of detection bias (subjective outcomes).

2 Downgraded one level for imprecision: only one study with relatively few participants included in comparison.

We were unable to pool data for any of the comparisons, except that of "brief intervention versus treatment as usual" and "motivational interviewing versus treatment as usual". We therefore summarise the results according to the type of psychosocial intervention, with comparisons of quantitative data where possible. The included studies used different questionnaires to measure their outcomes and, for many, the authors did not report post‐treatment/follow‐up scores, or they did not state what was considered to represent mild, moderate and severe categories. This prevented comparison of results across the studies. See the Characteristics of included studies table for more detailed information.

We present the effects of the interventions by the comparisons examined in the primary studies. The primary outcomes of this review were alcohol use (or abstinence) and retention in treatment. The main secondary outcome was illicit drug use (or abstinence). We were unable to report alcohol‐related problems or harms because they were not measured in the included trials.

1. Cognitive‐behavioural coping skills training (CBCST) versus twelve‐step facilitation (TSF)

See: Table 1 for this comparison.

Primary outcomes

1.1 Alcohol abstinence as number achieving three or more weeks of consecutive alcohol abstinence during treatment

There was no significant difference between CBCST and TSF for this outcome (risk ratio (RR) 1.96, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.43 to 8.94; one study, 41 participants (Carroll 1998); very low‐quality evidence), see Analysis 1.1.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Cognitive‐behavioural coping skills training (CBCST) versus twelve‐step facilitation (TSF) programme, Outcome 1 Alcohol abstinence as number achieving 3 or more weeks of consecutive alcohol abstinence during treatment.

1.2 Alcohol abstinence as maximum number of weeks of consecutive alcohol abstinence during treatment

There was no significant difference between CBCST and TSF for this outcome (mean difference (MD) 0.40, 95% CI ‐1.14 to 1.94; one study, 41 participants (Carroll 1998); very low‐quality evidence), see Analysis 1.2.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Cognitive‐behavioural coping skills training (CBCST) versus twelve‐step facilitation (TSF) programme, Outcome 2 Alcohol abstinence as maximum number of weeks of consecutive alcohol abstinence during treatment.

1.3 Alcohol abstinence during follow‐up year

There was no significant difference between CBCST and TSF for this outcome (RR 2.38, 95% CI 0.10 to 55.06; one study, 41 participants (Carroll 1998); very low‐quality evidence), see Analysis 1.3.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Cognitive‐behavioural coping skills training (CBCST) versus twelve‐step facilitation (TSF) programme, Outcome 3 Alcohol abstinence during follow‐up year.

1.4 Retention as number of people who completed all treatment sessions (unpublished)

There was no significant difference between CBCST and TSF for this outcome (RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.62 to 1.29; one study, 41 participants (Carroll 1998); very low‐quality evidence), see Analysis 1.4.

Secondary outcomes

1.5 Illicit drug abstinence as maximum number of weeks of consecutive abstinence from cocaine during treatment

There was no significant difference between CBCST and TSF for this outcome (MD 0.80, 95% CI ‐0.70 to 2.30; one study, 41 participants (Carroll 1998); very low‐quality evidence), see Analysis 1.5.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Cognitive‐behavioural coping skills training (CBCST) versus twelve‐step facilitation (TSF) programme, Outcome 5 Illicit drug abstinence as maximum number of weeks of consecutive abstinence from cocaine during treatment.

1.6 Illicit drug abstinence as number achieving three or more weeks of consecutive abstinence from cocaine during treatment

There was no significant difference between CBCST and TSF for this outcome (RR 1.10, 95% CI 0.42 to 2.88; one study, 41 participants (Carroll 1998); very low‐quality evidence), see Analysis 1.6.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Cognitive‐behavioural coping skills training (CBCST) versus twelve‐step facilitation (TSF) programme, Outcome 6 Illicit drug abstinence as number achieving 3 or more weeks of consecutive abstinence from cocaine during treatment.

1.7 Illicit drug abstinence as abstinence from cocaine during follow‐up year

There was no significant difference between CBCST and TSF for this outcome (RR 0.39, 95% CI 0.04 to 3.98; one study, 41 participants (Carroll 1998); very low‐quality evidence), see Analysis 1.7.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Cognitive‐behavioural coping skills training (CBCST) versus twelve‐step facilitation (TSF) programme, Outcome 7 Illicit drug abstinence as abstinence from cocaine during follow‐up year.

1.8 Alcohol‐related harms or problems

There were no data for this outcome.

2. Brief intervention (BI) versus treatment as usual (TAU)

See Table 2 for this comparison.

Primary outcomes

2.1 Alcohol use as scores on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) or Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST) at three months

There was no significant difference between BI and TAU for this outcome (standardised mean difference (SMD) 0.07, 95% ‐0.24 to 0.37; three studies, 170 participants (Darker 2016; Feldman 2013; Henihan 2016); low‐quality evidence), see Analysis 2.1.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Brief intervention (BI) versus treatment as usual (TAU), Outcome 1 Alcohol use as AUDIT or ASSIST scores at 3 months.

2.2 Alcohol use as AUDIT scores at nine months

There was no significant difference between BI and TAU for this outcome (MD 2.30, 95% CI ‐0.58 to 5.18; one study, 110 participants (Feldman 2013); low‐quality evidence), see Analysis 2.2.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Brief intervention (BI) versus treatment as usual (TAU), Outcome 2 Alcohol use as AUDIT scores at 9 months.

2.3 Alcohol use as decreased alcohol use at three months

There was no significant difference between BI and TAU for this outcome (RR 1.13, 95% CI 0.67 to 1.93; one study, 110 participants (Feldman 2013); low‐quality evidence), see Analysis 2.3.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Brief intervention (BI) versus treatment as usual (TAU), Outcome 3 Alcohol use as decreased alcohol use at 3 months.

2.4 Alcohol use as number of drinks per week at three months

There was no significant difference between BI and TAU for this outcome (MD 0.70, 95% CI ‐3.85 to 5.25; one study, 110 participants (Feldman 2013); low‐quality evidence), see Analysis 2.4.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Brief intervention (BI) versus treatment as usual (TAU), Outcome 4 Alcohol use as number of drinks per week at 3 months.

2.5 Alcohol use as number of drinks per week at nine months

There was no significant difference between BI and TAU for this outcome (MD ‐0.30, 95% CI ‐4.79 to 4.19; one study, 110 participants (Feldman 2013); low‐quality evidence), see Analysis 2.5.

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Brief intervention (BI) versus treatment as usual (TAU), Outcome 5 Alcohol use as number of drinks per week at 9 months.

2.6 Alcohol use as decreased alcohol use at nine months

There was no significant difference between BI and TAU for this outcome (RR 1.09, 95% CI 0.62 to 1.92; one study, 110 participants (Feldman 2013); low‐quality evidence), see Analysis 2.6.

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Brief intervention (BI) versus treatment as usual (TAU), Outcome 6 Alcohol use as decreased alcohol use at 9 months.

2.7 Retention at three months (unpublished and published data)

There was no significant difference between BI and TAU for this outcome (RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.78 to 1.13; three studies, 170 participants (Darker 2016; Feldman 2013; Henihan 2016); low‐quality evidence), see Analysis 2.7.

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Brief intervention (BI) versus treatment as usual (TAU), Outcome 7 Retention at 3 months (unpublished and published data).

Secondary outcomes

2.8 Illicit drug use

There were no data for this outcome.

2.9 Alcohol‐related harms or problems

There were no data for this outcome.

3. Motivational interviewing (MI) versus treatment as usual or educational intervention only

See: Table 3 for this comparison.

Primary outcomes

3.1 Alcohol use as AUDIT or ASSIST scores at three months

There was no significant difference between BI and TAU/education for this outcome (SMD 0.04, 95% CI ‐0.29 to 0.37; two studies, 141 participants (Darker 2016; Feldman 2013); low‐quality evidence), see Analysis 3.1.

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Motivational interviewing (MI) versus treatment as usual (TAU) or educational intervention only, Outcome 1 Alcohol use as AUDIT or ASSIST scores at 3 months.

3.2 Alcohol use as AUDIT scores at nine months

There was no significant difference between BI and TAU for this outcome (MD 2.30, 95% CI ‐0.58 to 5.18; one study, 110 participants (Feldman 2013); low‐quality evidence), see Analysis 3.2.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Motivational interviewing (MI) versus treatment as usual (TAU) or educational intervention only, Outcome 2 Alcohol use as AUDIT scores at 9 months.

3.3 Alcohol use (unpublished) as number of standard drinks consumed per day over the last 30 days

There was no significant difference between MI and educational intervention for this outcome (MD ‐0.20, 95% CI ‐1.76 to 1.36; one study, 225 participants (Nyamathi 2010); low‐quality evidence), see Analysis 3.3.

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Motivational interviewing (MI) versus treatment as usual (TAU) or educational intervention only, Outcome 3 Alcohol use as number of standard drinks consumed per day over the last 30 days.