Abstract

Background

Ventilator‐associated pneumonia is a common complication in ventilated patients. Endotracheal suctioning is a procedure that may constitute a risk factor for ventilator‐associated pneumonia. It can be performed with an open system or with a closed system. In view of suggested advantages being reported for the closed system, a systematic review comparing both techniques was warranted.

Objectives

To compare the closed tracheal suction system and the open tracheal suction system in adults receiving mechanical ventilation for more than 24 hours.

Search methods

We searched CENTRAL (The Cochrane Library 2006, Issue 1) MEDLINE, CINAHL, EMBASE and LILACS from their inception to July 2006. We handsearched the bibliographies of relevant identified studies, and contacted authors and manufacturers.

Selection criteria

The review included randomized controlled trials comparing closed and open tracheal suction systems in adult patients who were ventilated for more than 24 hours.

Data collection and analysis

We included the relevant trials fitting the selection criteria. We assessed methodological quality using method of randomization, concealment of allocation, blinding of outcome assessment and completeness of follow up. Effect measures used for pooled analyses were relative risk (RR) for dichotomous data and weighted mean differences (WMD) for continuous data. We assessed heterogeneity prior to meta‐analysis.

Main results

Of the 51 potentially eligible references, the review included 16 trials (1684 patients), many with methodological weaknesses. The two tracheal suction systems showed no differences in risk of ventilator‐associated pneumonia (11 trials; RR 0.88; 95% CI 0.70 to 1.12), mortality (five trials; RR 1.02; 95% CI 0.84 to 1.23) or length of stay in intensive care units (two trials; WMD 0.44; 95% CI ‐0.92 to 1.80). The closed tracheal suction system produced higher bacterial colonization rates (five trials; RR 1.49; 95% CI 1.09 to 2.03).

Authors' conclusions

Results from 16 trials showed that suctioning with either closed or open tracheal suction systems did not have an effect on the risk of ventilator‐associated pneumonia or mortality. More studies of high methodological quality are required, particularly to clarify the benefits and hazards of the closed tracheal suction system for different modes of ventilation and in different types of patients.

Plain language summary

Closed tracheal suction systems versus open tracheal systems for mechanically ventilated adults

The comparison of open and closed suction systems shows them to have similar results in terms of safety and effectiveness.

Tracheal secretions in mechanically ventilated patients are removed using a catheter via the endotracheal tube. The suction catheter can be introduced by disconnecting the patient from the ventilator (open suction system) or by introducing the catheter into the ventilatory circuit (closed suction system). Although the literature reports several advantages for the closed suction system, the review did not show differences between the two systems in the main outcomes studied. These outcomes were ventilator‐associated pneumonia and mortality. This review identified few trials of high methodological quality. Future research should be of higher quality, clarify issues related to the patient's condition and to technique, and provide nurse‐related outcomes.

Background

Mechanical ventilation (MV) and intervention manoeuvres such as endotracheal suction are contributing risk factors for ventilator‐associated pneumonia (VAP). VAP is defined as pneumonia that develops in an intubated patient after 48 hours or more of MV support. It is associated with high morbidity and mortality and is considered one of the most difficult infections to diagnose and prevent (Chester 2002; Collard 2003; NNIS 2000).

Endotracheal suctioning, one of the most common invasive procedures carried out in an intensive care unit (ICU), is used to enhance clearance of respiratory tract secretions, improve oxygenation and prevent atelectasis. As an essential part of care for intubated patients, its major goal is to ensure adequate ventilation, oxygenation and airway patency. Endotracheal suction involves patient preparation, suctioning and follow‐up care as part of the procedure (McKelvie 1998; Wood 1998). Major hazards and complications of endotracheal suctioning include hypoxaemia, tissue hypoxia, significant changes in heart rate or blood pressure, presence of cardiac dysrhythmias and cardiac or respiratory arrest. Additional complications include tissue trauma to the tracheal or bronchial mucosa, bronchoconstriction or bronchospasm, infection, pulmonary bleeding, elevated intracranial pressure and interruption of MV (Grap 1996; Maggiore 2002; Naigow 1977; Paul‐Allen 2000; Woodgate 2001).

The endotracheal suctioning technique is classically performed by means of the open tracheal suction system (OTSS), which involves disconnecting the patient from the ventilator and introducing a single‐use suction catheter into the patient's endotracheal tube. During the late 1980s, the closed tracheal suction system (CTSS) was introduced to more safely suction patients on MV as a multi‐use catheter is introduced into the airways without disconnecting the patient from the ventilator (Carlon 1987). This catheter system may be left in place for as long as 24 hours (Carlon 1987), or more (Kollef 1997). The suggested advantages of CTSS compared to conventional OTSS are: improved oxygenation; decreased clinical signs of hypoxaemia; maintenance of positive end‐expiratory pressure; limited environmental, personnel and patient contamination; and smaller loss of lung volume. As a result the CTSS is currently being used to minimize hazards and complications associated with endotracheal suctioning. Numerous studies have been conducted to test CTSS, compared with an OTSS, analyzing the prevalence of VAP and evaluating hyperoxygenation, influence of airway pressure and ventilation mode, the effect on cardiorespiratory parameters, efficiency in secretion removal and mortality. Some studies reported that the incidence of colonization increased when a CTSS was used but noted that VAP incidence was similar whether suctioning was done with OTSS or CTSS (Deppe 1990; Johnson 1994). Combes reported that the use of a CTSS reduced VAP incidence without demonstrating any adverse effect (Combes 2000). The use of CTSS may affect bacterial colonization of the airway and the prevalence of VAP and it is recommended for patients who have an aerosol transmittable infection, HIV, hepatitis B or active respiratory tuberculosis (Lee 2001; Stenqvist 2001). In view of such scientific evidence, a systematic review on the safety and effectiveness of a CTSS in comparison with an OTSS might be helpful in highlighting the main outcomes such as VAP incidence and mortality.

Objectives

We assessed the effects of suctioning with a closed tracheal suction system in comparison with an open tracheal suction system in adult patients receiving mechanical ventilation for more than 24 hours in terms of VAP incidence, bacterial colonization, mortality, length of stay in the intensive care unit and costs, as well as physiological, technique‐related and nursing‐related outcomes.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in which closed and open suction systems were compared. We included abstracts and unpublished data if sufficient information on study design, patient characteristics, interventions and outcomes was available.

Types of participants

Adult patients (aged 18 years or over) on mechanical ventilation for more than 24 hours in an intensive care unit.

Types of interventions

We included studies where an open tracheal suction system was compared to closed tracheal suction system.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Ventilator‐associated pneumonia (VAP) and time to VAP

Mortality

Secondary outcomes

Colonization and cross‐contamination

Length of stay in the intensive care unit (LOS)

Time on ventilation

Costs

Cardiorespiratory parameter variations (as defined in the included studies)

Technique‐related outcomes (as defined in the included studies)

Nursing‐related outcomes (as defined in the included studies)

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched trials in the Cochrane Controlled Trials Register (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library 2006, Issue 2); MEDLINE (1966 to July 2006); CINAHL (1982 to July 2006); EMBASE (1974 to July 2006) and LILACS (1982 to April 2004). We did not apply any language restrictions.

We searched MEDLINE (through PubMED) with the addition of the Cochrane MEDLINE filter for RCTs (Robinson 2002). Our search strategy can be found in Appendix 1.

We performed searches of CENTRAL, CINAHL, EMBASE and LILACS using a similar strategy which we adapted for each database (see Appendix 1). Some changes were made in relation to the strategy originally planned in the protocol in order to focus the search on studies which directly compared the two suction systems.

Searching other resources

We screened the bibliographies of relevant identified papers for further studies. We contacted the authors of main studies to identify published and unpublished studies. We also contacted the manufacturers of suction catheter systems.

Data collection and analysis

Methods used to collect data

Two authors (IS, MS) independently screened the abstracts of the references obtained from the search to identify trials making the comparison between the open and the closed suction systems. After reviewing full‐text copies of these relevant studies, trials were agreed on by the two authors for inclusion in the review. We resolved disagreements by involving a third author (SB). Each author independently extracted relevant data from the included studies using a previously designed data extraction form. We resolved possible discrepancies by consensus. Where appropriate for the objectives of the review, complementary data or data not included in the study reports were requested from authors.

Methodological quality

We used the standard methods of the Cochrane Anaesthesia Review Group (Cracknell 2006), that advise authors to assess methodological quality using the criteria set out in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2005).

We analysed individual components of study quality (Jüni 2001) rather than assigning a quantitative score, which has been criticized as not being very useful (Downs 1998). Individual components assessed were:

method of randomization;

allocation concealment;

blinding of outcome assessment; and

reporting of follow up and losses.

We chose to assess only the blinding of outcome assessment because it is impossible to blind the investigator or the nurse responsible for the suctioning.

Statistical analyses

One of the authors (IS) entered the relevant data from trials into the Review Manager software (RevMan 4.2) and a second author (MS) checked this process for accuracy. We expressed effect measures as relative risk (RR) for dichotomous data and weighted mean differences (WMD) for continuous data. For outcomes reported as mean and range, we estimated the standard deviation using the difference of the range values divided by four, assuming a normal distribution of the sample. We used this method although it is not robust and is even discouraged by some because the ranges express extremes of an observed outcome rather than the average (Higgins 2005).

Heterogeneity was assessed prior to meta‐analysis by means of the chi‐squared test (statistically significant at P < 0.1). To further assess heterogeneity, we calculated the I‐squared (I2) statistic (Higgins 2003) which describes the percentage of total variation across studies that is attributable to heterogeneity rather than to chance. The random‐effects model was assumed. We chose the random‐effects model expecting a considerable heterogeneity between the eligible studies. Although the review results do not show heterogeneity for most of the outcomes considered, we preferred to maintain that model as decided in the protocol.

We did not perform the subgroup and publication bias analyses planned in the protocol, mainly because the original studies did not include the required data and we were unsuccessful in obtaining missing data from the study authors.

Results

Description of studies

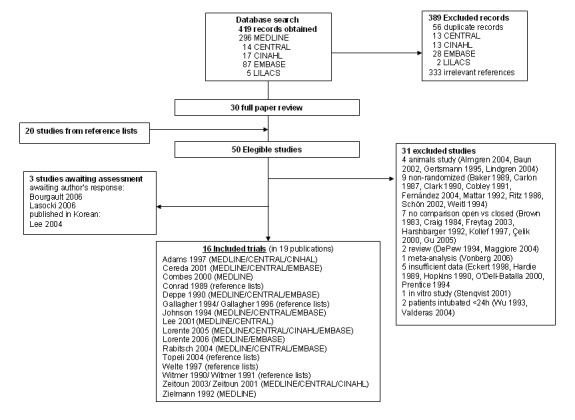

The search of the literature identified 419 relevant references for the review. Of these, we selected 51 for further assessment for their inclusion in the review. (We also identified 21 references from the reference lists of 30 full papers obtained for extensive assessment (see Additional Figure 1)). We established contact with the main closed suction device manufacturers in order to request for further trials, but we received no response. We identified two unpublished trials from the references lists of included studies (Gallagher 1994; McQuillan 1992) and a further trial published in Korean (Lee 2004), but we were unable to contact the authors. Nevertheless, we managed to obtain the abstract of Gallagher 1994 and included their results in our analysis. We were unable to find information on the McQuillan 1992 study. Three of the eligible studies are presently 'awaiting assessment' as we need to clarify some inclusion issues and methodological aspects (Bourgault 2006; Lasocki 2006) or have been unable to obtain a translation of the report (Lee 2004). In future updates of the review, this latter trial will be translated and considered for inclusion.

1.

Search results

Of the potentially eligible references, we excluded 31 studies (see 'Characteristics of excluded studies') because they: (1) were animals studies (four studies); (2) were reviews (two studies); (3) were not randomized (nine studies); (4) did not compare the OTSS and the CTSS (seven studies); (5) included patients who were intubated for less than 24 hours (two studies); (6) were 'in vitro' studies (one study); (7) was a meta analysis (one study); or (8) did not include sufficient information (five studies).

From the group of studies with insufficient information, we decided to exclude three studies (Kollef 1997; Prentice 1994; Valderas 2004) after having assessed the information provided by the authors. For Kollef 1997 and Valderas 2004 this was based on study design and for Prentice 1994 there was a weakness in the concealment of the randomization sequence so that the sickest patients were probably allocated to the CTSS; data provided in the original publication (as an abstract) were insufficient. In the case of O'Dell‐Batalla 2000, the trial report was published in a narrative abstract form and did not include any numerical data on the results. Contact with the authors to obtain additional data was unsuccessful.

A total of 16 randomized controlled trials met the inclusion criteria and were finally included in the review; 13 were parallel‐group trials (Adams 1997; Conrad 1989; Combes 2000; Deppe 1990; Gallagher 1994; Johnson 1994; Rabitsch 2004; Lorente 2005; Lorente 2006; Topeli 2004; Welte 1997; Zeitoun 2003; Zielmann 1992), whereas the remaining three included studies were cross‐over trials (Cereda 2001; Lee 2001; Witmer 1991). A description of the included trials is detailed in the 'Characteristics of included studies' tables.

Only 10 of the included trials reported details about the suction manoeuvre (Cereda 2001; Combes 2000; Deppe 1990; Johnson 1994; Lee 2001; Lorente 2005; Lorente 2006; Rabitsch 2004; Topeli 2004; Witmer 1991). For suction protocol details see 'Characteristics of included studies'. Additional tables 02 to 04 detail the suction procedure reported in the included studies and include patient preparation (Additional Table 1), suction event (Additional Table 2) and patient follow up after the suction procedure (Additional Table 3) (Collard 2003). Patient conditions and intervention factors related to the risk of developing VAP development are summarized in Additional Table 4 and Table 5 (Kollef 1999).

1. Description of endotracheal suctioning procedure: patient preparation.

| Study | Hyperinflation | Hyperoxygenation | Hyperventilation | Sodium Chloride 0.9% |

| Adams 1997 | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated |

| Cereda 2001 | Not done | Not done | Not stated | Not stated |

| Combes 2000 | Not stated | Done in the OTSS group | Not stated | Not stated |

| Conrad 1989 | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated |

| Deppe 1990 | Not stated | Done | Not stated | Done |

| Gallagher 1994 | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated |

| Johnson 1994 | Not stated | Done | Not stated | Done (3‐5 ml) |

| Lee 2001 | Not stated | Done | Not stated | Not stated |

| Lorente 2005 | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated |

| Lorente 2006 | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated |

| Rabitsch 2004 | Not stated | Done | Not stated | Not stated |

| Topeli 2005 | Not stated | Done | Not stated | Not stated |

| Welte 1997 | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not done |

| Witmer 1991 | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated |

| Zeitoun 2003 | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated |

| Zielmann 1992 | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated |

2. Description of endotracheal suctioning procedure: suction event.

| Study | Aseptic technique | Negative pressure | Suct. catheter size | Number of suctions | Suction duration | Patient assessment | Patient monitoring |

| Adams 1997 | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | CTSS:16.6 (2‐33) vs OTSS:10 (0‐43) | Not stated | Yes | Not stated |

| Cereda 2001 | Not stated | 100 mmHg | 12 French | CTSS:2 vs OTSS:2 | 20 seconds | Yes | Yes |

| Combes 2000 | Yes | 80 mmHg | Not stated | 1 every 2 hours | 10 seconds | Yes | Not stated |

| Conrad 1989 | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | CTSS:10.6 vs OTSS:8.8 | Not stated | Yes | Not stated |

| Deppe 1990 | Yes | 80 mmHg | Not stated | CTSS:16.6 vs OTSS:12 | 10 seconds | Yes | Not stated |

| Gallagher 1994 | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Yes | Not stated |

| Johnson 1994 | Not stated | CTSS:80‐100 mmHg vs OTSS:100‐120 mmHg | Not stated | At discretion of the patient's bedside nurse (CTSS:149 OTSS:127) | <15 seconds | Yes | Yes |

| Lee 2001 | Not stated | Not stated | CTSS:12 French | Not stated | Not stated | Yes | Yes |

| Lorente 2005 | Done for the OTSS | Not stated | Not stated | CTSS:8.1±3.5 vs OTSS:8.3±3.7 | Not stated | Yes | Not stated |

| Lorente 2006 | Done for the OTSS | Not stated | Not stated | CTSS:8.1±2.7 vs OTSS:7.9±2.6 | Not stated | Yes | Not stated |

| Rabitsch 2004 | Yes | Not stated | Not stated | Day 1: CTSS:7 (6‐9) vs OTSS:8 (6‐9); Day 3: CTSS:8 (6‐9) vs OTSS:8 (6‐10) | Not stated | Yes | Not stated |

| Topeli 2004 | Done for the OTSS | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Yes | Not stated |

| Welte 1997 | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Yes | Not stated |

| Witmer 1991 | Not stated | 120 torr | 14 French | Not stated | Not stated | Yes | Not stated |

| Zeitoun 2003 | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated |

| Zielmann 1992 | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Median of 15 suctions | Not stated | Yes | Not stated |

3. Description of endotracheal suctioning procedure: follow up after the procedure.

| Study | Hyperinflation | Hyperoxygenation | Hyperventilation | Patient monitoring |

| Adams 1997 | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated |

| Cereda 2001 | Not done | Not done | Not stated | Done |

| Combes 2000 | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated |

| Conrad 1989 | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated |

| Deppe 1990 | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated |

| Gallagher 1994 | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated |

| Johnson 1994 | Not done | Not done | Not done | Done |

| Lee 2001 | Not done | Not done | Not done | Done |

| Lorente 2005 | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated |

| Lorente 2006 | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated |

| Rabitsch 2004 | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Done |

| Topeli 2004 | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated |

| Welte 1997 | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated |

| Witmer 1991 | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated |

| Zeitoun 2003 | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated |

| Zielmann 1992 | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated |

4. Risk of VAP related to patient conditions.

| Study | Age | ARDS | Chest trauma | Coma/impaired consc. | Severe chronic dis. | Severity of illness | Smoking history |

| Adams 1997 | CTSS:49.3; OTSS:55.8 | No | No | No | Yes | Child Pug Score for CTSS:A=3, B=7; Child Pug Score for OTSS:A=2, B=7, C=1 | Not stated |

| Cereda 2001 | 58.6±15.9 | 3/10 | No | No | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated |

| Combes 2000 | CTSS:43±20.7; OTSS:43.8±17.8 | Not stated | Not stated | Glasgow Coma Scale for CTSS:8.1 (4.9); Glasgow Coma Scale for OTSS:7.6 (4.4) | Not stated | SAPS for CTSS:7.88 (3.2); SAPS for OTSS:6.91 (2.44) | Not stated |

| Conrad 1989 | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated |

| Deppe 1990 | 53.2 (16‐85) | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | APACHE/TISS | Yes |

| Gallagher 1994 | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | APACHE II/AIS 80/TISS | Yes |

| Johnson 1994 | CTSS:44; OTSS:42 | No | CTSS:4; OTSS:8 | Not stated | COPD on CTSS:3; COPD on OTSS:4 | Average APACHE score:12; Trauma ISS score for CTSS:35; Trauma ISS score for OTSS:31 | Not stated |

| Lee 2001 | 69.7±16.1 | No | No | Glasgow Coma Scale:10.6±0.7 | No | APACHE II:21.2 | Not stated |

| Lorente 2005 | CTSS:59.4±16; OTSS:58.2±16.3 | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | APACHE for CTSS:15.4±6.2; APACHE for OTSS:15.8±6.3 | Not stated |

| Lorente 2006 | CTSS:59.6±16.5; OTSS:59.2±16.1 | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | APACHE for CTSS:13.8±8.8; APACHE for OTSS:13.7±8.7 | Not stated |

| Rabitsch 2004 | CTSS:64 (51‐75); OTSS:63 (50‐79) | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Yes | APACHE II | Not stated |

| Topeli 2004 | CTSS:60.6±2.7; OTSS:67.9±2.6 | Not stated | Not stated | Glasgow Coma Scale for CTSS:11.1±0.6; Glasgow Coma Scale for OTSS:11.2±0.7 | Not stated | APACHE II for CTSS:25.6±1.1; APACHE for OTSS:23.8±1.3 | Not stated |

| Welte 1997 | CTSS:47.9; OTSS:51.8 | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated |

| Witmer 1991 | 59 | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Yes | Not stated | Not stated |

| Zeitoun 2003 | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Yes | APACHE II for CTSS:24; APACHE II for OTSS:22 | Yes |

| Zielmann 1992 | CTSS:38 (18‐84); OTSS:44 (18‐97) | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated |

5. Risk of VAP related to intervention factors.

| Study | Antacids | Antibiotic therapy | Sedation | H2 blockers | Intracr pres monitor | MV > 48 hours | NG tube |

| Adams 1997 | Not stated | Yes | Not stated | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Cereda 1997 | Not stated | Not stated | Yes | Not stated | No | Not stated | Not stated |

| Combes 2000 | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Yes | Not stated | Yes | Yes |

| Conrad 1989 | Not stated | Yes | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Yes | Yes |

| Deppe 1990 | Yes | Yes | Not stated | Yes | Not stated | Yes | Yes |

| Gallagher 1994 | Yes | Yes | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated |

| Johnson 1994 | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated |

| Lee 2001 | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated |

| Lorente 2005 | Yes | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Yes | Yes |

| Lorente 2006 | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Yes |

| Rabitsch 2004 | Not stated | Yes | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Yes | Not stated |

| Topeli 2004 | Not stated | Not stated | Yes | Not stated | Not stated | Yes | Yes |

| Welte 1997 | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Yes | Not stated |

| Witmer 1991 | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Yes | Not stated |

| Zeitoun 2003 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Not stated | Yes | Not stated |

| Zielmann 1992 | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated |

Risk of bias in included studies

Most of the studies included in the review had methodological weaknesses (see Additional Table 6: 'Methodological quality of included studies'). Three of the included trials reported insufficient data since they were published only in abstract form (Conrad 1989, Gallagher 1994, Welte 1997). Despite efforts to procure additional information regarding the studies with missing data, we only obtained data from Lorente 2005 (personal communication).

6. Methodological quality of included studies.

| Study | Randomization | Allocation Concealm. | Blinded Assessment | Follow up |

| Adams 1997 | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Yes |

| Cereda 2001 | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Yes |

| Combes 2000 | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Yes |

| Conrad 1989 | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Unclear (17 patients randomized to the OTSS, but the VAP rate was reported only for 15 patients) |

| Deppe 1990 | Adequate (random number table) | Not stated | Yes | Yes |

| Gallagher 1994 | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated |

| Johnson 1994 | Inadequate (randomization based on bed availability) | Inadequate | Not stated | Yes (3 losses were reported: 1 patient in OTSS passed to CTSS, and 2 withdrawals in CTSS) |

| Lee 2001 | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Yes (1 follow up loss for the ECG analysis) |

| Lorente 2005 | Adequate (random number table) | Adequate (independent office) | Yes | Yes |

| Lorente 2006 | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Yes |

| Rabitsch 2004 | Adequate (random number list) | Adequate (sealed envelopes provided by an independent deparment) | Yes | Yes |

| Topeli 2004 | Inadequate (even file patient numbers were randomized to CTSS, and odd file numbers to the OTSS) | Inadequate | No (personal communication) | Yes |

| Welte 1997 | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Yes |

| Witmer 1991 | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Yes |

| Zeitoun 2003 | Inadeqaute (admitted on even dates randomized to OTSS, and admitted on odd dates to CTSS) | Inadequate | Not stated | Yes |

| Zielmann 1992 | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Yes |

Only six trials provided information about the randomization method followed and their allocation concealment. Deppe 1990 and Lorente 2005 adequately randomized their patients by means of a random number table, but the allocation concealment was not clearly reported. However, in a personal communication the authors of the Lorente 2005 trial clarified that an independent office was in charge of the randomization sequence. Rabitsch 2004 also used a list of random numbers to randomize their patients; concealment was adequate because an independent department provided the allocation sequence by means of sealed envelopes. Three trials (Johnson 1994; Topeli 2004; Zeitoun 2003) were quasi‐randomized trials. Johnson 1994 randomized the recruited patients depending on bed availability and Zeitoun 2003 allocated the patients recruited on even dates to the OTSS group whereas the patients recruited on odd dates were allocated to the CTSS group. Topeli 2004 used a similar system to randomize their patients: even file number patients were allocated to the CTSS group whereas odd file number patients were allocated to the OTSS group. The remaining included trials did not provide details on randomization or allocation concealment.

The suction procedure cannot be blinded to nurses and participants. The only option was to blind the person in charge of outcome assessment. This was only performed by three studies (Deppe 1990; Lorente 2005; Rabitsch 2004).

In most trials the follow‐up period was short. Patients in most cases completed the study and losses were rare. Nevertheless four trials (Conrad 1989; Johnson 1994; Lee 2001; Zielmann 1992) reported some losses during the trial (see Additional Table 6).

Effects of interventions

Where appropriate, we performed meta‐analyses. Many of the secondary outcomes described in this section were measured at very different time points and some studies reported highly skewed data. Due to this, we could not always perform a pooled analysis and chose to give only a narrative description of the main results. We provide numerical data for the studies results in Additional Table 7. All the pooled estimations showed a statistical homogeneity with the exception of that performed for length of stay in ICU.

7. Included studies results.

| Outcomes | Results |

| Primary Outcomes | |

| Ventilator‐associated pneumonia | Adams 1997 VAP (NS): 0/10 CTSS, 0/10 OTSS. Combes 2000 1. VAP (NS): CTSS: 7.4% (4/54) representing 7.32 VAP per 1000 patient days. OTSS: 18% (9/50) representing 15.98 VAP per 1000 patient days. OTSS was accompanied by a 3.5 fold higher risk of VAP; prophylactic use of gastric acid secretion inhibitors increased this risk 4.3 times (P 0.04). 2. Time to the VAP occurrence (NS): 5 (3‐10) days CTSS, 5 (2‐23) days OTSS. Conrad 1989 Nosocomial pneumonia (NS): 38% (6/16) CTSS, 35.3% (6/17) OTSS. Time to infection (NS): 5.8 ± 2.6 days CTSS, 4.1 ± 0.9 days OTSS. Infection rate (NS): 0.04 per day CTSS, 0.054 per day OTSS. Deppe 1990 Nosocomial pneumonia incidence (NS): 26% (12/46) CTSS, 29% (11/38) OTSS. When evaluating 1) hospitalization <72h prior to entering the study (N: 52) and 2) hospitalization >72h prior to entering the study (N: 32) there was no statistical difference between CTSS and OTSS. Johnson 1994 Nosocomial pneumonia (NS): 50% (8/16) CTSS vs. 52.6% (10/19) OTSS. Lorente 2005 1. VAP (NS): 20.47% (43/210) CTSS, 18.02% (42/233) OTSS. 2. Cases of VAP per 1000 days of mechanical ventilation (NS): 17.59% (46/2615) CTSS, 15.84% (47/2966) OTSS. Lorente 2006 1. VAP CTSS= 13.9% (33/236) OTSS = 14.1% (31/221) (P=0.99) 2. Cases of ventilator associated pneumonia per 1000 days of mechanical ventilation CTSS = 14.1% (33/2336) OTSS = 14.6% (31/2113) (P=0.8) Rabitsch 2004 VAP: 0% (0/12) CTSS, 41.67% (5/12) OTSS (P=0.037) Topeli 2004 1. VAP (NS): 31.7% (13/41) CTSS, 24.3% (9/37) OTSS. 2. Time from intubation to the development of VAP (NS): 8.1±1 days CTSS, 7.7±2.3 days OTSS. Welte 1997 VAP (signification not stated): 33.3% (9/27) CTSS, 64% (16/25) OTSS. Zeitoun 2003 VAP (NS): 30.4% (7/23) CTSS, 45.8% (11/24) OTSS. |

| Mortality | Combes 2000 Mortality (NS): 26% (14/54) CTSS, 28% (14/50) OTSS. Deppe 1990 Mortality (NS): 26% (12/46) CTSS, 29% (11/38) OTSS. Lorente 2005 Mortality (NS): 24.7% (52/210) CTSS, 21.4% (50/233) OTSS. Lorente 2006 Mortality CTSS = 13.1% (31/236) OTSS = 13.5% (30/221) (P=0.78) Topeli 2004 3. Mortality in ICU (NS): 65.9% (27/41) CTSS, 67.6% (25/37) OTSS. Surrogate outcome: Time on ventilation Conrad 1989 Time on ventilator (NS): 12.4 (15.2) days CTSS, 7.6 (5.2) days OTSS. Lorente 2005 Days on mechanical ventilation (NS): 12.45±14.07 CTSS, 12.72±14.14 OTSS. Lorente 2006 Days on mechanical ventilation CTSS =9.9±12.1 OTSS =9.5±12.1 (P=0.76) Topeli 2004 Duration of MV (NS): 8.2±0.7 days CTSS, 7.5±1.0 days OTSS. |

| Secondary Outcomes | |

| Bacterial Colonization | Adams 1997 Microbiological analysis of endotracheal aspirate (NS): Patients with microorganism isolated for CTSS at 24 hours: 3/10; at day 2‐3: 3/6; at day 4‐5: 0/0; at day 6‐7: 0/0. Patients with microorganism isolated for OTSS at 24 hours: 3/10; at day 2‐3: 2/3; at day 4‐5: 1/2; at day 6‐7: 1/1. Deppe 1990 Colonization rates (P<0.02): 67% (31/46) CTSS, 39% (15/38) OTSS. Gallagher 1994 1. Colonization incidence with acinetobacter calcoaceticus (NS): 13/99 CTSS, 7/99 OTSS. 2. Time to colonization (NS): 53.5 (15.5‐313.0) CTSS, 132.0 (28.5‐368.5) OTSS. Topeli 2004 Colonization rate (NS): 16/41 CTSS, 13/37 OTSS. Welte 1997 Colonization (NS): 14.8% (4/27) CTSS, 8% (2/25) OTSS. Surrogate outcome: Cross‐contamination Rabitsch 2004 Cross‐contamination between the bronchial system and the gastric juices (P=0.037; as reported by the authors) 0% (0/12) CTSS, 41.67% (5/12) OTSS. 5. VAP (P=0.037; as reported by the authors) 0% (0/12) CTSS, 41.67% (5/12) OTSS. |

| Length of stay in the ICU | Combes 2000 Length of stay (NS): 15.6 ± 13.4 days CTSS, 19.9 ± 16.7 days OTSS. Topeli 2004 Length of ICU stay (NS): 12.3±7.04 days CTSS, 11.5±8.54 days OTSS. |

| Respiratory outcomes | Cereda 2001 1. Drop in lung volume (P<0.05): ‐133.5 ± 129.9 CTSS, ‐1231.5 ± 858.3 OTSS. 2. SpO2 (P<0.05): 97.2 ± 2.9 CTSS, 94.6 ± 5.1 OTSS. 3. PaO2 (NS): before suctioning with CTSS (123.5±26.1) and after suctioning with CTSS (123.2±25.7). Before suctioning with OTSS (122.6±26.0) and after suctioning with OTSS (117.3±31.1). 4. PaCO2 (NS): before suctioning with CTSS (48.1±14.3) and after suctioning with CTSS (47.9±14). Before suctioning with OTSS (47.4±14.0) and after suctioning with OTSS (49.2±14.3). 5. PaO2 (NS): before suctioning with CTSS (123.5±26.1) and after suctioning with CTSS (123.2±25.7). Before suctioning with OTSS (122.6±26.0) and after suctioning with OTSS (117.3±31.1). 6. HbO2 (NS): before suctioning with CTSS (95.6±2.6) and after suctioning with CTSS (95.7±2.6). Before suctioning with OTSS (96.6±2.7) and after suctioning with OTSS (95.2±3.3). 7. Respiratory rate (P<0.05): before suctioning with CTSS (15.1±4.5), during suction (39.8±6.6) and after suctioning with CTSS (15.1±5.4). Before suctioning with OTSS (15.1±4.3) and after suctioning with OTSS (15.1±4.3). 8. Airway pressure (P<0.05): before suctioning with CTSS (15.9±5.1), during suction (18.0±5.5) and after suctioning with CTSS (15.9±5.1). Before suctioning with OTSS (16±5.1) and after suctioning with OTSS (15.9±5.1). Johnson 1994 1. Mean arterial pressure Change from B to AH (P=0.0019): +0.7% (89±1.3mmHg) CTSS vs. +4% (92±1.7 mmHg) OTSS. Change from B to AS (P=0.0001): +8.6% (97±1.4 mmHg) CTSS vs. +17.3% (102±1.7 mmHg) OTSS. Change from B to 30s (P=0.0001): +7.9% (101±1.6 mmHg) CTSS vs. +15.2% (96±1.2 mmHg) OTSS. 2. Oxygen saturation Change from B to AH (P=0.0005): +0.3% (98±0.2%) CTSS vs. ‐0.4% (97±0.3%) OTSS. Change from B to AS (P=0.0001): +1.6% (99±0.1%) CTSS vs. ‐1.1% (99±0.1%) OTSS. Change from B to 30s (P=0.0001): +1.4% (99±0.1%) CTSS vs. ‐0.4% (97±0.1%) OTSS. 3. Systemic venous oxygen saturation Change from B to AH (NS): +0.3% (73±0.9%) CTSS vs. ‐0.9% (72±0.9%) OTSS. Change from B to AS (P=0.0001): +2.1% (74±0.9%) CTSS vs. ‐8.3% (67±1.5%) OTSS. Change from B to 30s (P=0.0001): +3.4% (75±1.0%) CTSS vs. ‐7.7% (67±1.4%) OTSS. Lee 2001 1. Oxygen saturation (NS at BL1, T2 and T5. Significant at S1, S2 and BL2) Values at BL1 (NS): 96.36±3.27% CTSS vs 95.50±4.70% OTSS. Values at T2 (NS): 95.79±3.87% CTSS vs 94.86±5.99% OTSS. Values at T5 (NS): 95.5±3.74% CTSS vs 94.93±5.34% OTSS. Values at S1 (P<0.05): 98.29±2.40% CTSS vs 97±4.66% OTSS (CTSS BL1 vs CTSS S1; OTSS BL1 vs OTSS S1). Values at BL2 (P<0.05): 98.07±2.87% CTSS vs 95.36±5.9% OTSS (CTSS BL1 vs CTSS BL2; CTSS vs OTSS). Values at S2 (P<0.05): 97±3.64% CTSS vs 95.79±5.67% OTSS (CTSS vs OTSS). 2. Mean arterial pressure (NS at BL1, T2 and T5. Significant at S1, S2 and BL2) Values at BL1 (NS): 87.57±18.03 mmHg CTSS vs 89.43±19.54 mmHg OTSS. Values at T2 (NS): 91.29±19.35 mmHg CTSS vs 89.43±18.59 mmHg OTSS. Values at T5 (NS): 86.86±17.68 mmHg CTSS vs 85.36±16.75 mmHg OTSS. Values at S1 (P<0.05): 91.21±18.58 mmHg CTSS vs 92.79±17.98 mmHg OTSS (CTSSBL1 vs. CTSSS1). Values at BL2 (P<0.05): 84.64±19.68 mmHg CTSS vs 93.14±21.03 mmHg OTSS (OTSSBL1 vs OTSSBL2; CTSS vs OTSS). Values at S2 (P<0.05): 92.36±21.44 mmHg CTSS vs 95.71±21.73 mmHg OTSS. (CTSSBL1 vs CTSSS2; OTSSBL1 vs OTSSS2) 3. Respiratory rate (NS at BL1, S1, BL2, S2, T2 and T5) Values at BL1 (NS): 21.43±7.61 breaths/min CTSS vs 20.21±6.44 breaths/min OTSS. Values at S1 (NS): 20.14±6.63 breaths/min CTSS vs 22±9.98 breaths/min OTSS. Values at BL2 (NS): 20.43±7.45 breaths/min CTSS vs 23.21±10.23 breaths/min OTSS: Values at S2 (NS): 22.43±7.39 breaths/min CTSS vs 23.29±10.62 breaths/min OTSS. Values at T2 (NS): 23.14±8.5 breaths/min CTSS vs 22.14±8.58 breaths/min OTSS. Values at T5 (NS): 23.43±7.95 breaths/min CTSS vs 21.07±7.49 breaths/min OTSS. Rabitsch 2004 Oxygen saturation: SaO2 at beginning of suctioning day1: 96.3±1.4% CTSS, 97.2±1.9% OTSS. SaO2 at the end of suctioning day1: 96.8±1.0% CTSS, 89.6±2.5% CTSS. (P<0.0001) OTSS at the beginning of suctioning vs. OTSS at the end of suctioning. Sa O2 at beginning of suctioning day3: 97.0±1.4% CTSS, 96.8±1.0% OTSS. Sa O2 at the end of suctioning day3: 96.4±0.8 CTSS, 89.6±1.9 CTSS. (P<0.0001) OTSS at the beginning of suctioning vs. OTSS at the end of suctioning. |

| Cardiovascular outcomes | Cereda 2001 1. Heart rate (NS): before suctioning with CTSS (97.1±21.9), during suction (100.2±20.0) and after suctioning with CTSS (97.6±21.3). Before suctioning with OTSS (98.7±22.3) during suction (97.5±21.4) and after suctioning with OTSS (98.1±22.5). 2. Mean arterial pressure (P<0.05): before suctioning with CTSS (79.4±11.7), during suction (81.2±11.9) and after suctioning with CTSS (80.0±11.6). Before suctioning with OTSS (78.1±10.2) during suction (83.2±14.7) and after suctioning with OTSS (84.5±13.6). Johnson 1994 1. Heart rate Change from B to AH (NS): +1.2% (98±1.4 beats/min) CTSS vs +2.2% (108±1.8 beat/min) OTSS. Change from B to AS (NS): +5.7% (102±1.5 beats/min) CTSS vs +8.1% (114±1.7 beat/min) OTSS. Change from B to 30s (P=0.0209): +3.6% (100±1.4 beats/min) CTSS vs +6.4% (112±1.8 beats/min) OTSS. 2. Heart rhythm (P = 0.0001) Dysrhythmias 2% (3/149 suctioning passes) CTSS vs 14% (8/127 suctioning passes) OTSS. Lee 2001 1. Heart rate (NS at BL1, T2 and T5. Significant at S1, S2 and BL2) Values at BL1 (NS): 100±19.6beats/min CTSS vs 100.29±22.05 beats/min OTSS. Values at T2 (NS): 100.43±19.79 beats/min CTSS vs 106.86±29.87 beats/min OTSS. Values at T5 (NS): 99.43±21.51 beats/min CTSS vs 105.07±29.65 beats/min OTSS. Values at S1 (P<0.05): 96.43±20.4 beats/min CTSS vs 102.29±20.53 beats/min OTSS. Values at BL2 (P<0.05): 96.14±20 beats/min CTSS vs 101±20.49 beats/min OTSS. (CTSSBL1 vs CTSSBL2) Values at S2 (P<0.05): 97.43±19.79 beats/min CTSS vs. OTSS: 106.86±29.87 beats/min; 2. Heart rhythm (P<0.05) Dysrhythmias 0% (0/13 suctioning manoeuvre) CTSS, 38.5% (5/13 suctioning manoeuvre) OTSS. |

| Technique related outcomes | Adams 1997 Suctions per day (NS): 16.6 (2‐33) CTSS, 10 (0‐43) OTSS Conrad 1989 1. Suction frequency (NS): 10.6 per day CTSS, 8.8 per day OTSS. 2. Antibiotic usage (NS): 94% (15/16) CTSS, 88% (15/17) OTSS. 3. Nasogastric tube (NS): 50% (8/16) CTSS, 36% (6/17) OTSS. Deppe 1990 Suctions per day (P<0.054): 16.6 CTSS, 12.4 OTSS. Analysis performed in 41 patients, 23 CTSS, 18 OTSS. Lorente 2005 Aspirations per day (NS): 8.13±3.54 CTSS, 8.32±3.71 OTSS. Lorente 2006 Aspirations per day CTSS =8.1±2.7 OTSS =7.9±2.6 (P=0.64) Rabitsch 2004 1. Number of suctioning per day (NS) Day1, 7 (6‐9) and day3, 8 (6‐9) for CTSS. Day1, 8 (6‐9) and day3, 8 (6‐10) for OTSS. 2. Quantity of secretions (NS) Day1, 2 little, 6 moderate, 4 profuse. Day3, 2 little, 6 moderate, 4 profuse for CTSS. Day1, 2 little, 7 moderate, 3 profuse. Day3, 2 little, 6 moderate, 4 profuse for OTSS. Witmer 1991 Quantity of secretions removed (NS): 1.7 g CTSS, 1.9 g OTSS Zielmann 1992 Suctions performed. During the total study period a median of 15 suction manoeuvres were performed; group distribution not stated. |

| Nursing related outcomes | Johnson 1994 Nursing time (P = 0.0001): 93 seconds per procedure CTSS vs 153 seconds per procedure OTSS Zielmann 1992 Nursing time (significance data not stated): 2.5 (2‐4) CTSS, 3.5 (2‐6) OTSS. |

| Comments | The outcomes showed significant differences, unless otherwise stated (NS) ALI: acute lung injury; ARDS: acute respiratory distress syndrome; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CTSS: closed tracheal suction system; ET: endotracheal; ICU: intensive care unit; MV: mechanical ventilation; NS: non‐significant; OTSS: open tracheal suction system; PEEP: positive‐pressure respiration; RCT: randomized controlled trial; VAP: ventilator associated pneumonia Johnson 1994: Data was collected before suctioning, baseline (B), after hyperoxygenation (AH), immediately after suctioning (AS) and 30 seconds after suctioning (30s). Lee 2001: Data was collected before the two suction manoeuvres (BL1 and BL2), at the moment of the manoeuvres (S1 and S2), and then 2 and 5 minutes post‐suctioning (T2 and T5). |

Primary outcomes

Ventilator‐associated pneumonia (VAP)

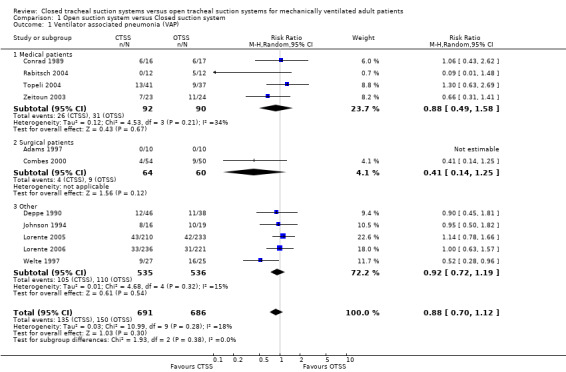

Eleven of the included studies reported data about the incidence of VAP, comparing CTSS with OTSS (see table 'Comparisons and data 01 01'). The pooled estimation for the risk of developing VAP did not show any significant differences (N = 1377; RR 0.88; 95% CI 0.70 to 1.12) indicating that suctioning with the closed or the open system did not affect the risk of VAP, even when a subgroup analysis was performed according to the type of patient (medical, surgical or mixed) included in the studies.

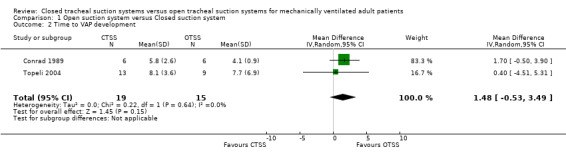

Time to VAP

In three studies (Conrad 1989; Combes 2000Topeli 2004) time to VAP was not significantly different between suction systems. Neither did a pooled analysis for two of the studies (see table 'Comparisons and data 01 02') show differences between groups (N 34; WMD 1.48; 95% CI ‐0.53 to 3.49). Data about time to infection were not entered into the pooled analysis for Combes 2000 because the outcome was reported using the median and range. This study reported the same time to infection for the CTSS group (5 days (range 3 to 10)) as for patients suctioned with the OTSS (5 days (range 2 to 23)).

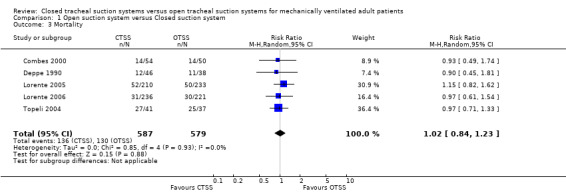

Mortality

Six studies reported data on mortality (ranging between 22% and 68%) but one did not provide numerical data (Welte 1997). Based on the results of five included studies (see table 'Comparisons and data 01 03') the two suction systems showed no differences in relation to mortality (N = 1166; RR 1.02; 95% CI 0.84 to 1.23).

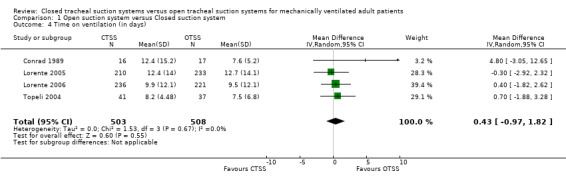

Time on ventilation

Patient mortality has been shown to relate to the duration of time on ventilation. For this review, four studies presented highly skewed data for this outcome (Conrad 1989; Lorente 2005; Lorente 2006; Topeli 2004). The pooled analysis did not show a significant difference between suction techniques for this outcome (see table 'Comparisons and data 01 04') (N = 1011; WMD 0.44; 95% CI ‐0.92 to 1.80).

Secondary outcomes

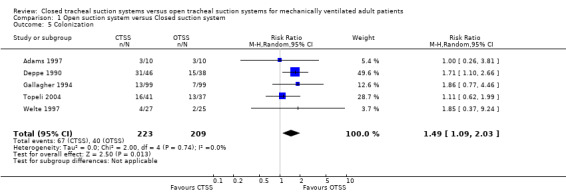

Bacterial colonization

Five studies reported results on bacterial colonization (see table 'Comparisons and data 01 05'). The pooled analysis of these five studies showed a significant increase in colonization for the CTSS group, with a 49% increased risk in comparison with the OTSS (N = 432; RR 1.49; 95% CI 1.09 to 2.03).

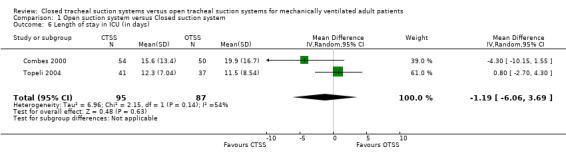

Length of stay (LOS) in the intensive care unit (ICU)

Combes 2000 and Topeli 2004 reported skewed data on LOS in ICU, without statistically significant differences between the CTSS and OTSS groups (see table 'Comparisons and data 01 06') (WMD 1.19; 95% CI ‐6.06 to 3.69).

Time on ventilation

See the Mortality section above for results on this outcome.

Costs

It was difficult to make a direct comparison between studies concerning costs as there were large differences in data analysis and also in the study periods (over different years). Five studies assessed the costs associated with tracheal suction systems (Adams 1997; Johnson 1994; Lorente 2005; Lorente 2006; Zielmann 1992). Costs were statistically different and much higher for the CTSS group in all studies except in Johnson 1994. Lorente 2006 reported a lower cost with the CTSS in patients ventilated for more than four days. In light of the differences in reporting results for this outcome they are summarized in Additional Table 8.

8. Costs.

| Study | Costs CTSS | Costs OTSS | Comments |

| Adams 1997 | Average daily costs: £16.89 sterling | Average daily costs: £1.45 sterling | |

| Johnson 1994 | Daily cost: US$13.00 | Daily cost: US$14.88 | Results based on a unit average of 16 suctioning procedures per patient per day |

| Lorente 2005 | Patient costs per day: US$ 11.11±2.25 | Patient costs per day: US$ 2.50±1.12 | |

| Lorente 2006 | Patient costs per day: eur 2.3±3.7 | Patient costs per day: eur 2.4±0.5 | For patients ventilated lower than 4 days the CTSS costs were higher than those of the OTSS (CTSS = eur 7.2±4.7 vs OTSS = eur 1.9±0.6; P<0.001). This trend changed for the patients ventilated longer than 4 days (CTSS = eur 1.6±2.8 vs OTSS = eur 2.5±0.5; P< 0.001) |

| Zielmann 1992 | Patient costs per day: eur 27.35 | Patient costs per day: eur 9 | Results based on an average of 15 suction procedures |

Cardiorespiratory parameter variations

Cardiorespiratory parameter included the analysis of oxygenation and ventilation and cardiovascular outcomes. We were unable to do summary statistics due to the differences between the included studies in reporting the information. Hence we give a narrative description of the main results.

Respiratory outcomes

Oxygen saturation (SaO2 / SpO2)

Four studies monitored oxygen saturation continuously by pulse oximetry (Cereda 2001; Johnson 1994; Lee 2001; Rabitsch 2004). The studies coincided in reporting a significant decrease in oxygen saturation immediately after the suction procedure for those patients suctioned with the OTSS; patients in the CTSS groups maintained or increased their oxygen saturation values.

Respiratory rate, lung volumes and airway pressures (Paw)

Two of the included studies (Cereda 2001; Lee 2001) reported information on the respiratory rate without any difference between the two suction systems (see Additional Table 7). Cereda 2001 assessed lung volume measured by respiratory inductive plethysmography and reported a statistically significant difference in lung volume between CTSS (‐133.5 ± 129.9) and OTSS (‐1231.5 ± 858.3) groups (P < 0.01). In their study, Cereda 2001 observed a marked decrease in airway pressure (Paw) during suction with OTSS, while the decrease with CTSS was minor.

Cardiovascular outcomes (heart rate, heart rhythm, mean arterial pressure)

Heart rate (HR) increased with suction time for both suction groups in Johnson 1994. At 30 seconds post‐suction, the difference was significant between groups, with patients in the OTSS group showing a higher HR (see Additional Table 7). In Cereda 2001 there were no significant changes in HR during or after suctioning with CTSS or OTSS, despite a slight increase for patients in the CTSS group and a decrease in the OTSS group. In Lee 2001, however, changes were significant when comparing CTSS versus OTSS immediately after the first and second suction procedures, with higher HR for patients in the OTSS group.

The studies that measured heart rhythm reported higher rates of dysrhythmias in OTSS patients: Johnson 1994 observed 2% of dysrhythmias in the CTSS group and 14% in the OTSS group, whereas Lee 2001 reported dysrhythmias only for patients in the OTSS group (38.5%). Three trials (Cereda 2001; Johnson 1994; Lee 2001) reported data on mean arterial pressure (MAP). MAP was higher after suction for the OTSS group patients (see Additional Table 7 for numerical data).

Technique‐related outcomes

We identified two surrogate outcomes in relation to the suction technique: the number of suctions performed per day and the quantity of secretions removed. The heterogeneity of studies with regard to the definition of outcomes and their reporting (mainly regarding the absence of standard deviations in the study reports) did not allow pooling of these data.

Seven of the included studies that reported data about the number of suction manoeuvres performed per day (Adams 1997; Conrad 1989; Lorente 2005; Lorente 2006; Rabitsch 2004; Zielmann 1992) did not find significant differences between the two suction systems (see Additional Table 7). Deppe 1990 was the only study that reported significant differences.

The quantity of secretions removed by suction was reported in two studies (Rabitsch 2004; Witmer 1991). Results showed no significant differences in the quantity of secretions removed with the CTSS compared to the OTSS.

Nursing‐related outcomes

Results from Zielmann 1992 and Johnson 1994 reported that nurses needed more time to suction patients with OTSS. Zielmann 1992 observed that nurses averaged 3.5 minutes (range of 2 to 6 minutes) to suction patients with OTSS, whereas suctioning patients with CTSS took one minute less (average = 2.5 minutes, range 2 to 4 minutes). Johnson 1994 reported overall shorter times than those of Zielmann 1992 but the differences between groups remained. These authors reported an average of 2.5 minutes for the OTSS in comparison with the 1.5 minutes needed to suction with the CTSS.

Discussion

The major limitation for this systematic review was related to the methodological quality of the included studies. Based on the adequate reporting of the randomization method, blinding of outcome assessment and complete patients follow up, only three trials had a high methodological quality (Deppe 1990; Lorente 2005; Rabitsch 2004). The major weaknesses in the included studies were related to inaccuracy in reporting information about the randomization method and allocation concealment. These are the two methodological issues with the highest amount of evidence about their effects on trial results (Jüni 2001). This weakness highlights a lack of attention when authors report the studies, even in trials published after the CONSORT statement (Moher 2001), and reduces the reliability of the methodological quality assessment (Chan 2005). Furthermore, many identified studies were published as abstracts. Of the nine studies initially identified as abstracts, only three (Conrad 1989; Gallagher 1994; Welte 1997) included sufficient information to consider their results for inclusion and further analysis. Regarding the study population, most studies had a small sample size, different case mixes and different mean ages of patients. Despite these limitations, the findings in this review are consistent.

This review included 16 trials that evaluated the effects of a closed tracheal suction system versus an open tracheal suction system. In general, the two systems appear to be similar in terms of safety and effectiveness. The review results showed that suctioning with either closed tracheal suction or open tracheal suction had no effect on the risk of ventilator‐associated pneumonia, even when a subgroup analysis based on patients' medical or surgical status was performed. The effect of the suction systems used on the risk of mortality showed no difference. Study data were heterogeneous, with mortality ranging between 22% and 68%. No statistically significant differences were found between closed tracheal suction system and open tracheal suction system groups in length of stay in the intensive care unit (Combes 2000; Topeli 2004). Patient condition and intervention factors (such as the use of an aseptic technique or the number of suctions performed) play a key role in the development of ventilator‐associated pneumonia but were poorly analysed in the included studies (Additional Table 4 and Table 5).

Condition of the patient and time to ventilator‐associated pneumonia showed no significant differences between suction systems (Combes 2000; Conrad 1989; Deppe 1990; Gallagher 1994; Lorente 2005; Topeli 2004). On the other hand, some other conditions related to ventilator‐associated pneumonia such as age, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), chest trauma, coma or impaired consciousness, severe chronic disease, severity of illness and smoking history (Collard 2003; Kollef 1999) were not assessed in the included studies. Combes 2000 adjusted the hazard ratio to age, sex and Glasgow Coma Score, showing a higher risk of ventilator‐associated pneumonia for patients suctioned with the open suction system.

Sedation (Cereda 2001; Topeli 2004; Zeitoun 2003) and prophylactic use of gastric acid secretion inhibitors (Combes 2000; Topeli 2004) are suggested to increase the risk of ventilator‐associated pneumonia. Selective digestive tract decontamination was reported in five studies (Adams 1997; Combes 2000; Deppe 1990; Gallagher 1994; Zeitoun 2003) and no reduction in pneumonia risk was observed. Bacterial colonization increased significantly for the closed suction group. Complete rinsing of the closed suction system after suctioning is crucial to prevent colonization (Hixson 1998). Unfortunately this aspect of nursing care was not clearly stated in the included studies.

Five studies reported data on costs but tracheal suction systems alone were not evaluated for their cost‐effectiveness. Differences in the year of study and in currency made comparison difficult. Based on a unit average of 16 suctioning procedures per patient per day, Johnson 1994 reported that daily costs per patient were $1.88 greater for the open tracheal suction system. Lorente 2006, with the same incidence of ventilator‐associated pneumonia between suction systems, reported that a non‐daily changed closed suction system in patients ventilated for less than four days had a higher cost compared with the open suction system. Costs for the closed system were lower when patients were ventilated for more than four days.

Five studies (Adams 1997; Conrad 1989; Lorente 2005; Rabitsch 2004; Zielmann 1992) reported data on the number of suctions per day and found no significant differences in the number of manoeuvres. But Deppe 1990 observed a significant increase in number of daily suctions in the closed tracheal suction group and suggested that this was due to the ease of the procedure. Two studies (Rabitsch 2004; Witmer 1991) reported the quantity of secretions removed, showing no significant differences between suction systems. There is insufficient evidence on which to base a recommendation regarding the effectiveness of suction devices on secretion removal.

Two studies (Johnson 1994; Zielmann 1992) reported that more time was needed to suction patients with the closed suction system. Literature concerning nursing satisfaction with the suction systems is also scarce. As a result, the impact of nursing care with both systems and in specific groups of patients remains unknown, making it an important area of interest for future research. The suction procedure should be performed only when necessary, not exceed 15 seconds and be according to clinical signs rather than a time standard (NNIS 2000; Noll 1990; Thompson 2000). Perception and technique in the use of the tracheal suction system can probably explain the misconception that a closed suction system does not suction as well as using an open suction system (NNIS 2000).

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Suctioning is an intervention that requires caution, is done based on a nurse's clinical decision and using an aseptic technique. The review suggests that there is no difference in the risk of ventilator‐associated pneumonia and mortality between open and closed suction systems.

Implications for research.

In reviewing the studies for this review, many concerns relating to quality and study design were identified. There is a need for well designed randomized trials with large sample sizes, and improved reporting of outcomes. Further research is required to clarify the potential benefits and hazards of closed suction systems with different patients, modes of ventilation and suction procedures. Furthermore specific cost‐effectiveness studies should be designed.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 13 December 2018 | Amended | Editorial team changed to Cochrane Emergency and Critical Care |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 1, 2004 Review first published: Issue 4, 2007

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 11 June 2010 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

| 21 June 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

Acknowledgements

We are grateful and indebted to Dr Mathew Zacharias (content editor) and Prof Nathan Pace (statistical editor) for their helpful comments that contributed to, and improved the quality of this review.

We would like to thank the following people.

Mrs Lynne Williams (peer reviewer) for commenting on the protocol. Dr Maureen O. Meade and Dr Malcolm G Booth (peer reviewers), Kathie Godfrey and Mark Edward (consumers) for commenting on the review.

Dr Phillipe Éckert, Mrs María Jesus García, Karin Kirchhoff, Dr Marin Kollef, Dr Leonardo Lorente, Mrs Donna Prentice, and Dr Arzu Topeli for their kind attention in providing additional information about their studies.

Mrs Marta Roqué for her statistical support with the first draft of this review.

Mrs Susanne Ebrahim (Cochrane Metabolic and Endocrine Disorders Review Group) for her help in translating German articles.

The authors would like to acknowledge the members of the Epidemiology Department who supported this study, particularly Dr. Xavier Bonfill, Ignasi Bolíbar, Ignasi Gich, Teresa Puig and Gerard Urrútia. We would also like to acknowledge the support provided by Carolyn Newey.

We would be grateful to any readers who provide further studies for assessment for future updates.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategies

| Database | Search Strategy |

| MEDLINE (PubMed) | #1. Closed‐system suction OR Closed system [tw] OR Closed‐system [tw] OR Closed suction method OR Closed suction system OR Closed suctioning system OR Closed suctioning [tw] OR Closed‐suction system OR Closed tracheal suction system OR Closed endotracheal suction #2. Open‐system suction OR Open suction system OR Open system [tw] OR Open‐suction system OR Open‐suction method OR Open suction method OR Open suctioning OR Open suctioning system #3. #1 AND #2 |

| CENTRAL (The Cochrane Library Issue 1, 2006) | #1 Closed‐system suction #2 Closed system #3 Closed‐system #4 Closed suction method #5 Closed suction system #6 Closed suctioning system #7 Closed suctioning #8 Closed‐suction system #9 Closed tracheal suction system #10 Closed endotracheal suction #11 OR/1‐10 #12 Open‐system suction #13 Open suction system #14 Open system #15 Open‐suction system #16 Open‐suction method #17 Open suction method #18 Open suctioning #19 Open suctioning system #20 OR/12‐19 #21 11 AND 20 |

| EMBASE (Ovid) | #1 (Closed‐system suction OR Closed system OR Closed‐system OR Closed suction method OR Closed suction system OR Closed suctioning system OR Closed suctioning OR Closed‐suction system OR Closed tracheal suction system OR Closed endotracheal suction).mp. #2 (Open‐system suction OR Open suction system OR Open system OR Open‐suction system OR Open‐suction method OR Open suction method OR Open suctioning OR Open suctioning system).mp. #3 1 AND 2 |

| CINAHL (Ovid) | #1 (Closed‐system suction OR Closed system OR Closed‐system OR Closed suction method OR Closed suction system OR Closed suctioning system OR Closed suctioning OR Closed‐suction system OR Closed tracheal suction system OR Closed endotracheal suction).mp. #2 (Open‐system suction OR Open suction system OR Open system OR Open‐suction system OR Open‐suction method OR Open suction method OR Open suctioning OR Open suctioning system).mp. #3 1 AND 2 |

| LILACS (Biblioteca Virtual em Saúde) | #1 aberto [Palavras] AND fechado [Palavras] AND aspiraçao [Palavras] #2 abierto [Palavras] AND cerrado [Palavras] AND succión [Palavras] #3 1 OR 2 |

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Open suction system versus Closed suction system.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Ventilator associated pneumonia (VAP) | 11 | 1377 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.88 [0.70, 1.12] |

| 1.1 Medical patients | 4 | 182 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.88 [0.49, 1.58] |

| 1.2 Surgical patients | 2 | 124 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.41 [0.14, 1.25] |

| 1.3 Other | 5 | 1071 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.92 [0.72, 1.19] |

| 2 Time to VAP development | 2 | 34 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.48 [‐0.53, 3.49] |

| 3 Mortality | 5 | 1166 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.02 [0.84, 1.23] |

| 4 Time on ventilation (in days) | 4 | 1011 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.43 [‐0.97, 1.82] |

| 5 Colonization | 5 | 432 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.49 [1.09, 2.03] |

| 6 Length of stay in ICU (in days) | 2 | 182 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐1.19 [‐6.06, 3.69] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Open suction system versus Closed suction system, Outcome 1 Ventilator associated pneumonia (VAP).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Open suction system versus Closed suction system, Outcome 2 Time to VAP development.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Open suction system versus Closed suction system, Outcome 3 Mortality.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Open suction system versus Closed suction system, Outcome 4 Time on ventilation (in days).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Open suction system versus Closed suction system, Outcome 5 Colonization.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Open suction system versus Closed suction system, Outcome 6 Length of stay in ICU (in days).

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Adams 1997.

| Methods | Design: parallel RCT. Method of randomization: not stated. Allocation concealment: not stated. Blinding of outcome assessment: no. Complete follow up: yes. |

|

| Participants | 20 liver transplant patients (10 CTSS, 10 OTSS). Setting: liver ICU in a General Hospital (Birmingham UK). Patient diagnosis: liver transplant for chronic liver failure. Sex: 6 males and 4 females in the CTSS group, 2 males and 8 females in the OTSS group. Mean age: 49.3 (30‐69) CTSS, 55.8 (35‐69) OTSS. Inclusion criteria: Mechanically ventilated for a minimum of 28 hours (48.1 hours CTSS, 62.5 hours OTSS). Without microbiological or clinical evidence of pneumonia. No patients had been hospitalized for more than 12 hours before endotracheal intubation. Exclusion criteria: not stated. | |

| Interventions | CTSS (Trach Care(r), Vygon, Gloucestershire, UK) vs OTSS. Suction protocol procedure not described. Data were collected until extubation. | |

| Outcomes | 1. VAP 2. Microbiological analysis of endotracheal aspirate 3. Suctions per day 4. Costs | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Cereda 2001.

| Methods | Design: cross‐over RCT. Method of randomization: not stated. Allocation concealment: not stated. Blinding of outcome assessment: no. Complete follow up: yes. |

|

| Participants | 10 patients with acute lung injury (ALI). Setting: ICU in a University Hospital in Milan (Italy). Patient diagnosis: 2 ALI and cardiac arrest; 3 ARDS; 2 pneumonia; 2 sepsis; 1 gastric aspiration. Sex: not stated. Mean age: 58.6±15.9. Inclusion criteria: patients with ALI; Mechanically ventilated with PEEP >= 5cmH2O. Exclusion criteria: bronchospasm or clinical history of COPD, elevation in intracranial pressure, haemodynamic instability. | |

| Interventions | CTSS (Mallinckrodt Medical, Mirandola, Italy) vs OTSS (Medicoplast, Illingen, Germany) the catheter was withdrawn after each used. Suction protocol clearly described. Setting of an inspiratory time of 25% on the ventilator, an inspiratory plateau time of 10% and a trigger sensitivity of ‐2 cmH2O. CTSS (12 Fr) was left in place throughout the study. After an adaptation period (20 min) the authors performed both a CTSS and an OTSS twice in an alternate sequence. A total of four steps were performed with a time interval of 20 min within manoeuvres. No hyper‐oxygenation or hyperinflation was applied before or after suctioning. CTSS: The suction catheter was unlocked and inserted into the ET without disconnection, catheter advanced and suction was applied for 20 sec (100 mm Hg). The catheter was withdrawn and locked. OTSS: After disconnection from the ventilator, a catheter (12 Fr) was inserted in the ET tube until resistance was met. Then it was withdrawn 2‐3cm. Suction was applied for 20 sec (100 mm Hg). Data were collected before, during and after suctioning. | |

| Outcomes | 1. Drop in lung volume 2. SpO2 3. PaO2 4. PaCO2 5. PaO2 6. HbO2 7. Respiratory rate 8. Airway pressure 9. Heart rate 10. Mean arterial pressure | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Combes 2000.

| Methods | Design: parallel RCT. Method of randomization: not stated. Allocation concealment: not stated. Blinding of outcome assessment: no Complete follow up: yes |

|

| Participants | 104 patients (54 CTSS, 50 OTSS) Setting: neuro‐surgical ICU at the Centre Hospitalier de Grenoble (France). Patient diagnosis: closed head injuries (64 CTSS, 59 OTSS), cerebro‐vascular accidents (30 CTSS, 33 OTSS). Sex: 37 males and 17 females in the CTSS group, 36 males and 14 females in the OTSS group. Mean age: 43 ± 20.7 CTSS, 43.8 ± 17.8 OTSS. Inclusion criteria: patients free of any acute or chronic chest disease, hospitalized within the last 48 hours and predicted time on the ventilator greater than 48 hours. Exclusion criteria: not stated. | |

| Interventions | CTSS (Stericath) replaced each 24 hours (8.00 AM) vs OTSS discarded after each use. Suction protocol procedure clearly described ET suctioning was performed once every 2 hours, at a pressure of less than ‐80 cm H2O, and was repeated if needed. The procedure did not exceed a period of 10 sec. Patients on the OTSS were preoxygenated for 30 sec at a FIO2 of 1.0. When a second suction was needed in the same procedure, the same material was used after having been cleaned with sterile solution. The CTSS was cleaned in a similar way after each suction maneuver. Data were collected after 48 hours of mechanical ventilation. | |

| Outcomes | 1. VAP (NS): 2. Time to the VAP occurrence 3. Length of stay 4. Mortality | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Conrad 1989.

| Methods | Design: parallel RCT. Method of randomization: not stated. Allocation concealment: not stated. Blinding of outcome assessment: no. Complete follow up: not clear. Although 17 patients were randomized to the OTSS, the pneumonia rate was reported in 15 patients. Published as an abstract. |

|

| Participants | 33 patients (16 CTSS, 17 OTSS). Setting: Medical Centre (Los Angeles; USA). Patient diagnosis: not stated. Sex: not stated. Mean age: not stated. Inclusion criteria: Patients without prior pneumonia. Exclusion criteria: not stated. | |

| Interventions | CTSS (Trach Care(r), Ballard Medical) replaced each 24 hours vs. OTSS discharged after each use. Suction protocol not clearly described. Data were collected during ICU admission. | |

| Outcomes | 1. VAP 2. Time on ventilator 3. Time to infection 4. Infection rate 5. Suction frequency 6. Antibiotic usage 7. Use of nasogastric tube | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Deppe 1990.

| Methods | Design: parallel RCT. Method of randomization: adequate (number random table). Allocation concealment: not stated. Blinding of outcome assessment: no. Complete follow up: yes. |

|

| Participants | 84 patients (46 CTSS, 38 OTSS). Setting: surgical ICU at Brooke Army Medical Center (Fort Sam Houston, Texas) and medical ICU at Ben Taub General Hospital (Houston, Texas; USA). Patient diagnosis: not stated. Sex: 48 males and 36 females. Mean age: 53.2 (16‐85). Inclusion criteria: Presence of endotracheal tube (not tracheostomy tube) at least 48h after study entry and no admission diagnosis and / or infiltrate compatible with the diagnosis of pneumonia. Exclusion criteria: not stated. Patients were stratified as follows: 1) hospitalization <72h prior to entering the study (N: 52) and 2) hospitalization >72h prior to entering the study (N: 32) | |

| Interventions | CTSS (Trach Care(r) Closed Suction System, Ballard Medical Products, Midvale UT) replaced each 24 hours (08.00hra) vs OTSS discarded after each use. Suction protocol clearly described. Suctions were performed each 3 hours and when needed. In cases of thick secretions of 5‐10 mL of sterile saline solution was installed into the ET. CTSS: Pre oxygenation with an FIO2 1 (6 or 7 breaths). The catheter control valve was unlocked, and the catheter (inside the sheath) advanced into the ET until mild resistance was met. The catheter was then withdrawn using intermittent suction pressure of ‐80 cm H2O (limiting suction to 10 seconds). The catheter was irrigated through the port while applying suction, and patient's level of oxygenation was resumed. OTSS: Pre oxygenation with an FIO2 1 with an Ambu manual bag (6 or 7 breaths). A sterile suction catheter was passed through the ET tube until encounter resistance was met. The catheter was withdrawn 2 cm and suction pressure of ‐80 cm H2O was applied, while withdrawing the catheter. Each manoeuvre was limited to 10 seconds, repeating the process until clearing the airway. Data were collected during ICU admission. | |

| Outcomes | 1. Colonization rates 2. Nosocomial pneumonia incidence 3. Suctions per day 4. Mortality | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Gallagher 1994.

| Methods | Design: parallel RCT. Method of randomization: not stated. Allocation concealment: not stated. Blinding of outcome assessment: not stated. Complete follow up: not stated. Published as an abstract. |

|

| Participants | 198 patients (99 CTSS, 99 OTSS). Setting: ICU (Auckland, New Zealand). Patient diagnosis: not stated. Sex: not stated. Mean age: not stated. Inclusion criteria: not stated. Exclusion criteria: not stated. | |

| Interventions | CTSS vs. OTSS. Suction protocol not described. Both groups were equivalent for age, sex, smoking history, referral source, APACHE II, TISS, instrumentation, use of H2 antagonist or cytoprotective agents and individual antibiotics. | |

| Outcomes | 1. Colonization incidence with acinetobacter calcoaceticus 2. Time to colonization | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Johnson 1994.

| Methods | Design: parallel Quasi‐RCT. Method of randomization: inadequate (based on bed availability). Allocation concealment: inadequate. Blinding of outcome assessment: no. Complete follow up: yes (3 losses: 1 patient in the OTSS passed to the CTSS, and 2 withdrawals in the CTSS). |

|

| Participants | 35 patients / 276 suction procedures (16 patients / 149 procedures CTSS, 19 patients / 127 procedures OTSS). Setting: trauma ICU in a level I trauma Center of the University of Kentucky Hospital (KY; USA). Patient diagnosis: burn trauma (11 CTSS, 10 OTSS), penetrating trauma (2 CTSS, 3 OTSS), vascular surgery (2 CTSS, 3 OTSS), general surgery (1 CTSS, 3 OTSS). Average APACHE score was 12 for both groups. Sex: 12 males and 4 females CTSS, 14 males and 5 females OTSS. Mean age: 42 CTSS, 44 OTSS. Inclusion criteria: presence of endotracheal tube or tracheostomy tube, absence of pneumonia and/or infiltrate consistent with pulmonary infection at study entry, admission to a general surgery or a surgical subspecialty service and age >17 years. Exclusion criteria: patients treated with endotracheal suctioning in another ICU. | |

| Interventions | CTSS (Trach Care Closed Suction System, Ballard Medical Products, Midvale, UT) replaced each 24 hours vs OTSS (Regu‐vac, Bard‐Parker, Lincoln Park, NJ) discarded after each manoeuvre. Each staff nurse was required to demonstrate 100% competency in both methods of suctioning protocols. Four rooms were designated to CTSS, and four rooms to OTSS. Patients were then allocated based on bed availability. Suction protocol was clearly described. CTSS: Pre oxygenation with FIO2 1 (3‐5 breaths). If patients had thick secretions 3‐5 mL of sterile normal saline solution were instilled through the irrigation port. The catheter was advanced into the ET until resistance was encountered. The catheter was withdrawn with a suction pressure of ‐100 to ‐120 cm H2O, while withdrawing the catheter (limiting suction to <15 seconds). The procedure was repeated until the airway was cleaned. The catheter was irrigated through the port while applying suction, and the patient's level of oxygenation was resumed. A respiratory therapist verified the ventilation settings. OTSS: Preoxygenation with FIO2 1 with an Ambu manual bag (3‐5 breaths). If patients had thick secretions, 3‐5 mL of sterile normal saline solution was instilled. A sterile suction catheter was passed through the ET tube until resistance was met. A suction pressure of ‐80 to ‐100 cm H2O was applied, while withdrawing the catheter. Each manoeuvre was limited to <15 seconds, repeating the process until the airway was clear. After each pass manual postoxygenation was applied. The bedside nurse performed the manoeuvre. | |

| Outcomes | 1. Mean arterial pressure 2. Heart rate 3. Heart rhythm 4. Arterial oxygen saturation 5. Systemic venous oxygen saturation 6. Nosocomial pneumonia 7. Costs 8. Nursing time | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | C ‐ Inadequate |

Lee 2001.

| Methods | Design: cross‐over RCT. Method of randomization: not stated. Allocation concealment: not stated. Blinding of outcome assessment: no. Complete follow up: yes (the authors only reported one loses during follow up for the heart rhythm analysis). |

|

| Participants | 14 patients randomized. Setting: surgical ICU in a General Hospital in Singapore. Patient diagnosis: 4 liver diseases, 6 gastrointestinal diseases, 1 acute myocardial infarction, 1 pneumonia, 2 thyroid diseases. Sex: 6 males and 8 females. Mean age: 67.8 (21‐86). Inclusion criteria: ET tube. Blood pressure monitoring. At least 2 days of admission to the ICU. Exclusion criteria: Raised intracranial pressure. Treatment with neuromuscular blocking agents. Mandatory closed suction. Glasgow coma scale <=8. Ramsay sedation score >=5. | |

| Interventions | CTSS (DAR Hi‐Care in‐line suction catheter 12 CH/FR, Tyco Healthcare) vs. OTSS. Suction protocol clearly described. Patients were randomized to receive closed suction or open suction in the first manoeuvre. Alternated suctioning was then used between 2 to 4 hours after the first procedure. Cardiorespiratory parameters were measured at baseline (BL1), followed by 60 seconds of hyperoxygenation. The first suction manoeuvre was performed for 10 seconds, measuring outcomes (S1) at the 5th second. Outcomes measure at the end of the 1st manoeuvre (BL2) and hyperoxygenation during 30 seconds. The second suction manoeuvre was performed for 10 seconds, with outcomes measured at the 5th second (S2), followed by 30 seconds of hyperoxygenation. Outcome measures were obtained 2 and 5 minutes after the second suction manoeuvre (T2 and T5). Suction pressure was ‐120 mmHg and catheter size was 12 Fr. | |

| Outcomes | 1. Oxygen saturation 2. Heart rate 3. Mean arterial pressure 4. Respiratory rate 5. Heart rhythm | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Lorente 2005.

| Methods | Design: parallel RCT. Method of randomization: adequate (random number table). Allocation concealment: adequate (the random number table was managed by an independent office; personal communication). Blinding of outcome assessment: yes. Complete follow up: yes. |

|

| Participants | 443 patients randomized (210 CTSS, 233 OTSS). Setting: 24‐bed medical‐surgical ICU in a 650‐bed tertiary Hospital (Spain). Patient diagnosis: Cardiac surgery 25.24% CTSS, 26.18% OTSS; Cardiology 16.66% CTSS, 13.73 OTSS; Respiratory 15.71% CTSS, 18.02% OTSS; Digestive 10% CTSS, 10.30% OTSS; Neurologic 15.71% CTSS, 15.02 OTSS; Traumatic 13.81% CTSS, 12.44% OTSS; Intoxication 2.86% CTSS, 4.29 OTSS. Sex: 146 (69.5%) males, 64 (30.5%) females CTSS, 158 (67.8%) males, 75 (32.2%) females OTSS. Mean age: 59.4 ± 16 CTSS, 58.2 ± 16.3 OTSS. Mean APACHE: 15.4 ± 6.2 CTSS, 15.8 ± 6.3 OTSS. Inclusion criteria: All patients who required MV for more than 24 consecutive hours. Exclusion criteria: not stated. | |