Abstract

Background

Endometrial carcinoma is the most common gynaecologic malignancy in the world and develops through preliminary stages of endometrial hyperplasia. Atypical endometrial hyperplasia suggests a significant pre‐malignant state with frank progression to endometrial carcinoma, and tends to occur at a young age. Oral progestins have been used as conservative treatment in young women with atypical endometrial hyperplasia, but they are associated with poor tolerability and side effects that may limit their overall efficacy. So it has become increasingly important and necessary to find a safe and effective fertility‐sparing treatment with better tolerability and fewer side effects than the options currently available. The levonorgestrel‐releasing intrauterine system (LNG‐IUS) has been used to provide endometrial protection in women with breast cancer who are on adjuvant tamoxifen. The antiproliferative function of levonorgestrel is thought to reduce the risk of endometrial hyperplasia.

Objectives

To determine the efficacy and safety of oral and intrauterine progestogens in treating atypical endometrial hyperplasia.

Search methods

In July 2018 we searched CENTRAL; MEDLINE; Embase; CINAHL, PsycINFO and the China National Knowledge Infrastructure for relevant trials. Cochrane Gynaecology and Fertility (CGF) Specialised Register and Embase were searched in November 2018. We attempted to identify trials from references in published studies. We also searched for ongoing trials in five major clinical trials registries.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of oral and intrauterine progestogens (LNG‐IUS) versus each other or placebo in women with a confirmed histological diagnosis of simple or complex endometrial hyperplasia with atypia.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors assessed trial eligibility and risk of bias and extracted the data. The primary outcomes of the review were rate of regression and adverse effects. Secondary outcomes included rate of recurrence and proportion of women undergoing hysterectomy. We have used GRADE methodology to judge the quality of the evidence.

Main results

We included one RCT (153 women) comparing the LNG‐IUS administering 20 micrograms (μu) levonorgestrel per day versus 10 milligrams of continuous or cyclical oral medroxyprogesterone (MPA) for treating any type of endometrial hyperplasia. Only 19 women in this study were histologically confirmed with atypical complex hyperplasia before treatment. The evidence was of low or very low quality. The included study was at low risk of bias, but the quality of the evidence was very seriously limited by imprecision and indirectness. We did not find any RCTS comparing the LNG‐IUS or oral progestogens versus placebo in women with atypical endometrial hyperplasia.

Among the 19 women with atypical complex hyperplasia, after six months of treatment there was insufficient evidence to determine whether there was a difference in regression rates between the LNG‐IUS group and the progesterone group (odds ratio (OR) 2.76, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.26 to 29.73; 1 RCT subgroup, 19 women, very low‐quality evidence). The rate of regression was 100% in the LNG‐IUS group (n = 6/6) and 77% in the progesterone group (n = 10/13).

Among the total study population (N = 153), over the six months' treatment the main adverse effects were nausea and vaginal bleeding. There was no evidence of a difference between the groups in rates of nausea (OR 0.58, 95% CI 0.28 to 1.18; 1 RCT, 153 women, very low‐quality evidence). Vaginal bleeding was more common in the LNG‐IUS group (OR 2.89, 95% CI 1.11 to 7.52; 1 RCT, 153 women, low‐quality evidence). Except for nausea and vaginal bleeding, no other adverse effects were reported.

Authors' conclusions

We did not find any RCTS of women with atypical endometrial hyperplasia, and our findings derive from a subgroup of 19 women in a larger RCT. All six women who used the LNG‐IUS system achieved regression of atypical hyperplasia, but there was insufficient evidence to draw any conclusions regarding the relative efficacy of LNG‐IUS versus oral progesterone (MPA) in this group of women. When assessed in a population of women with any type of endometrial hyperplasia, there was no clear evidence of a difference between LNG‐IUS and oral progesterone (MPA) in risk of nausea, but vaginal bleeding was more likely to occur in women using the LNG‐IUS. Larger studies are necessary to assess the efficacy and safety of oral and intrauterine progestogens in treating atypical endometrial hyperplasia.

Keywords: Female; Humans; Intrauterine Devices, Medicated; Administration, Oral; Endometrial Hyperplasia; Endometrial Hyperplasia/drug therapy; Levonorgestrel; Levonorgestrel/administration & dosage; Medroxyprogesterone; Medroxyprogesterone/administration & dosage; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Plain language summary

Oral and intrauterine progestogens for atypical endometrial hyperplasia

Review question

Cochrane authors investigated the efficacy and safety of oral and intrauterine progestogens for the precancerous condition of thickening in the lining of the womb (endometrium) called atypical endometrial hyperplasia.

Background

Oral progestins have been used as conservative (non‐surgical) treatment in young women with atypical endometrial hyperplasia. However, oral progestins are associated with side effects that may limit their overall efficacy. The levonorgestrel‐releasing intrauterine system (LNG‐IUS) is thought to reduce the risk of endometrial hyperplasia because it slows thickening in the lining of the womb, and studies have reported that it may be an appropriate conservative treatment for atypical hyperplasia. So it is important to determine the efficacy and safety of the LNG‐IUS in treating atypical endometrial hyperplasia.

Study characteristics

This review of the evidence found one randomised controlled trial (RCT) of the LNG‐IUS versus oral progestin therapy in women with any type of endometrial hyperplasia. It was conducted in Norway and included 153 women, but only 19 of the women had a confirmed histological diagnosis of atypical endometrial hyperplasia; the other women had other types of endometrial hyperplasia. The evidence is current to July 2018.

Key results

The included RCT compared LNG‐IUS versus oral continuous or cyclic medroxyprogesterone (MPA) for treating endometrial hyperplasia. After six months of treatment, there was insufficient evidence to determine whether there was a difference in regression rates between the LNG‐IUS group and the MPA group. The rate of regression was 100% in the LNG‐IUS group (n = 6/6) and 77% in the MPA group (n = 10/13). Among the total study population (N = 153), over the six months' treatment the main adverse effects were nausea and vaginal bleeding. There was no evidence of a difference between the groups in rates of nausea, but vaginal bleeding was more common in the LNG‐IUS group.

Quality of the evidence

The quality of the evidence was low or very low for all outcomes. The included study was at low risk of bias, but the quality of the evidence was very seriously limited by imprecision and indirectness.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Levonorgestrel‐releasing intrauterine system (LNG‐IUS) compared to medroxyprogesterone (MPA) 10 mg for atypical endometrial hyperplasia.

| Levonorgestrel‐releasing intrauterine system (LNG‐IUS) compared to medroxyprogesterone (MPA) 10 mg for atypical endometrial hyperplasia | ||||||

| Population: women with atypical endometrial hyperplasia Setting: outpatient clinic Intervention: LNG‐IUS Comparison: MPA 10 mg (continuous or cyclical) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with MPA 10 mg | Risk with LNG‐IUS | |||||

| Regression rate at 6 months |

769 per 1000 | 902 per 1000 (464 to 990) | OR 2.76 (0.26 to 29.73) | 19 (1 RCT subgroup) | Very lowa,b | |

| Nausea over 6‐month follow‐up |

410 per 1000 | 287 per 1000 (163 to 451) | OR 0.58 (0.28 to 1.18) | 153 (1 RCT) | Very lowc,d | No other adverse events were reported |

| Vaginal bleeding over 6‐month follow‐up |

730 per 1000 | 887 per 1000 (750 to 953) | OR 2.89 (1.11 to 7.52) | 153 (1 RCT) | Lowc | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

a Downgraded one level for indirectness: outcome measured in a subgroup of women (19/153) who were histologically confirmed with atypical complex hyperplasia. b Downgraded two levels for very serious imprecision; small sample, only 16 events, very wide confidence intervals. c Downgraded two levels for indirectness: outcome measured in total study population, of whom only a subgroup of women (19/153) were histologically confirmed with atypical complex hyperplasia. d Downgraded one level for serious imprecision; confidence intervals compatible with a benefit in the LNG‐IUS group, or with no difference between the groups.

Background

Description of the condition

Endometrial carcinoma is the most common gynecologic malignancy in the world and develops through preliminary stages of endometrial hyperplasia. Histologically, endometrial hyperplasia can be divided into three main categories of simple, complex and atypical hyperplasia. The classification is based on the degree of architectural and cytological abnormality. Cytological atypia is the most important prognostic factor for progression to carcinoma. Some 8% to 30% of atypical hyperplasias progress to carcinoma over a mean duration of four years, while only about 1% to 3% of non‐atypical hyperplasias progress to endometrial carcinoma over a mean duration of 10 years (Kurman 1985). This means that the presence of atypical endometrial hyperplasia suggests a significant pre‐malignant state with frank progression to endometrial adenocarcinoma. The optimal treatment of atypical endometrial hyperplastic lesions is essential to prevent the development of endometrial cancer. The standard treatment is hysterectomy. However, hysterectomy is not considered the optimal treatment for all women. For women who want to preserve fertility, who refuse an operation or have medical contraindications to surgery, conservative therapy is needed. Because atypical endometrial hyperplasia tends to occur at a young age (Guo 1993), it has become increasingly important and necessary to find a safe and effective fertility‐sparing treatment with better tolerability and fewer side effects than the options for treatment that are currently available.

Description of the intervention

Since the 1960s, oral progestins have been used as conservative treatment in young women with atypical endometrial hyperplasia. However, oral progestins are associated with poor tolerability and numerous systemic side effects (for example, headache, nausea) that may limit their overall efficacy. Furthermore, the long‐term use of oral progestins often results in metabolic changes and exposes the woman to a higher risk of thromboembolic events (Randall 1997). Gonadotropin‐releasing hormone (GnRH) analogues have also been proposed, but hormonal side effects preclude their long‐term use (Kullander 1992).

The levonorgestrel‐releasing intrauterine system (LNG‐IUS) was developed in the early 1970s. The Mirena is a T‐shaped device composed of a cylinder containing 52 mg of levonorgestrel covered by a rate‐controlling membrane which serves to regulate the rate of hormonal release; 20 μg of levonorgestrel is released every 24 hours from this polymer cylinder. The effect of levonorgestrel is to thin the endometrial lining of the uterus to make it less suitable for implantation and to change the cervical mucus and utero‐tubal fluid in a way that inhibits the passage of sperm. It provides contraceptive protection for up to five or seven years (Luukkainen 1991). Although the LNG‐IUS was developed for use as a contraceptive device, it is now commonly used for treating menorrhagia and for providing endometrial protection in women taking hormone therapy (Chi 1994; Cozza 2017; Eralil 2016; Sturridge 1996).

How the intervention might work

Levonorgestrel released from the intrauterine system inhibits the endometrial synthesis of oestrogen receptors and induces atrophy of the endometrial glands. During this process, the stroma undergoes a widespread decidual reaction and the mucosa and the epithelium become inactive (Critchley 2007; Sitruk‐Ware 2004). The device also suppresses the spiral arterioles of the mucosa and thickens the arteriole wall and reduces capillary thrombosis. These changes result in markedly decreased menstrual blood loss or amenorrhoea and endometrial growth suppression, which is seen three months after insertion of the LNG‐IUS. Moreover, the LNG‐IUS provides very high local concentrations of progestins to the uterine mucosa and acts many times more strongly on the endometrium than when levonorgestrel is given systemically (Xiao 1990). The dosage can, therefore, be reduced significantly to minimise side effects associated with hormonal problems and to optimise tolerability by women. However, side effects related to the intrauterine device such as pelvic inflammatory disease, ectopic pregnancy, expulsion and perforation may occur.

Some analyses have shown an 89% regression rate for atypical hyperplasia. Other prospective cohort studies reported that the LNG‐IUS was effective in the reversion of atypical endometrial hyperplasia (Buttini 2009; Pronin 2015; Qi 2008; Wildemeersch 2003; Wildemeersch 2007), suggesting that LNG‐IUS may be an appropriate conservative treatment for atypical hyperplasia. Nevertheless, this effect needs to be supported and confirmed by more evidence‐based studies, especially randomised controlled trials (RCTs).

Why it is important to do this review

The Cochrane Review of LNG‐IUS for endometrial protection in women with breast cancer who are on adjuvant tamoxifen has been published (Dominick 2015). The antiproliferative function of levonorgestrel is thought to reduce the risk of endometrial hyperplasia. LNG‐IUS appears to be a promising conservative treatment that is safe, convenient and reversible, thus it could provide a valuable alternative to hysterectomy and oral progestin, especially in younger women who still want to preserve fertility and in women who refuse an operation or are in poor health. Herein, we intend to determine the efficacy and safety of the LNG‐IUS in treating atypical endometrial hyperplasia.

Objectives

To determine the efficacy and safety of oral and intrauterine progestogens in treating atypical endometrial hyperplasia.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that evaluated the effects of oral (e.g. medroxyprogesterone (MPA)) and intrauterine progestogens (e.g. levonorgestrel‐releasing intrauterine system (LNG‐IUS)) versus each other or placebo in women with atypical endometrial hyperplasia.

Types of participants

Inclusion

Women with a confirmed histological diagnosis of simple or complex endometrial hyperplasia with atypia by pipelle biopsy or by curettage.

Exclusion

Women with contraindications to the LNG‐IUS (acute genital tract inflammatory disease, genital bleeding of unknown aetiology, pregnancy or suspicion of pregnancy, hypersensitivity to any component of this product, congenital or acquired uterine anomaly, known or suspected breast cancer, known or suspected uterine and cervical neoplasia or unresolved or abnormal Pap smear, acute liver disease or liver tumour, etc.).

Women with concurrent endometrial cancer.

Women with a history of any other malignancy.

Types of interventions

Intervention

LNG‐IUS insertion (Nova‐T, Levonovac/Mirena, Femilis, Fibroplant, Mirena).

Comparator

Progestins (including medroxyprogesterone acetate; megestrol acetate; 17a‐hydroxyprogesterone caproate; 6,17 adimethyl‐6‐dehydroprogesterone, 6‐methyl‐6‐dehydroprogesterone acetate).

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Regression rate (complete or partial): a 'complete regression' is defined as a return of the atypical endometrium to normal, often with associated secretory glandular changes and atrophy; a 'partial regression' is defined as a change from atypical to non‐atypical hyperplasia. The regression rate includes the complete and partial regression rate.

Adverse effects associated with hormonal problems: weight gain, acne, nausea, headache, dizziness, vomiting, depression, breast tenderness

Secondary outcomes

Recurrence rate

Proportion of women undergoing hysterectomy (histologically indicated or non‐histologically indicated)

Other adverse effects: bleeding (spotting, amenorrhoea, prolonged or heavy bleeding), pelvic inflammatory disease, ovarian cyst, uterine myoma, device‐related problems (expulsion, perforation)

Withdrawal from treatment because of adverse events

Satisfaction with treatment

Quality of life, measured using a scale that has been validated through reporting of norms in a peer‐reviewed publication

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

See: Cochrane Gynaecology and Fertility (CGF) Group methods used in reviews. A comprehensive search strategy was formulated in order to identify all RCTs regardless of language. We searched the following electronic databases:

Gynaecology and Fertility Group Specialised Register (Procite platform) (19 November 2018).

CENTRAL via CENTRAL Register of Studies Online (CRSO) (web platform) (9 July 2018).

MEDLINE; searched from 1946 (OVID platform) (9 July 2018).

Embase; searched from 1980 (OVID platform) (9 July 2018 and 19 November 2018).

PsycINFO; searched from 1806 (OVID platform) (9 July 2018).

CINAHL searched from 1961 (EBSCO platform) (9 July 2018).

Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) (web platform) (9 July 2018).

CBM (China Biomedicine Database) (web platform) (9 July 2018).

The search strategies, based on terms related to the review topic, are presented for each database in Appendix 1; Appendix 2; Appendix 3; Appendix 4; Appendix 5; Appendix 6; Appendix 7; Appendix 8. We used the PubMed 'related articles' feature to check for articles related to eligible studies. We searched the bibliographies of all relevant papers selected through this strategy. Where possible, we established personal communications with corresponding authors and clinical experts to enquire about other published or unpublished relevant studies.

Searching other resources

We searched the following trials registries for ongoing and registered trials.

ClinicalTrials.gov (a service of the US National Institutes of Health).(https://clinicaltrials.gov/)

The World Health Organisation International Trials Registry Platform search portal (www.who.int/trialsearch/)

DARE (database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects) on the Cochrane Library at www.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/o/cochrane (for reference lists from relevant non‐Cochrane reviews).

Web of Science (wokinfo.com), another source of trials and conference abstracts

OpenGrey (www.opengrey.eu) for unpublished literature from Europe

LILACS database (www.regional.bvsalud.org), for trials from the Portuguese and Spanish speaking world.

PubMed and Google Scholar (for recent trials not yet indexed in MEDLINE)(www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed)(scholar.google.com/)

We handsearched reference lists of articles retrieved by the search and contacted experts in the field to obtain additional data. We also handsearched relevant journals and conference abstracts that were not covered in the CGF register, in liaison with the CGF Information Specialist.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

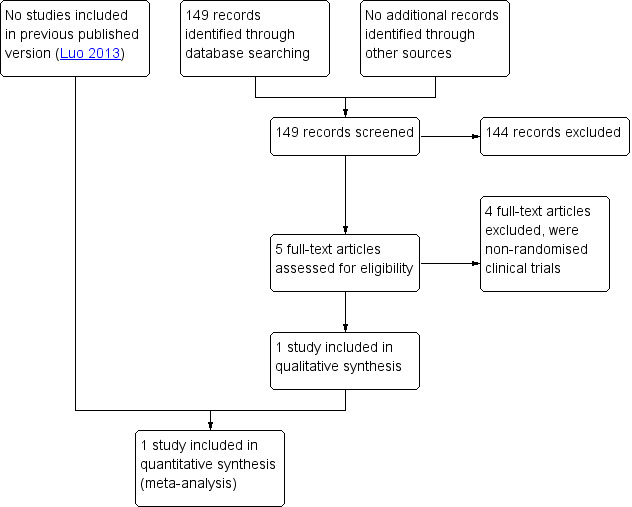

We downloaded all titles and abstracts retrieved by electronic searching to the reference management database (EndNote), removed duplicates and two review authors (LL, LB) independently examined the remaining references. We excluded those studies which clearly did not meet the inclusion criteria and obtained copies of the full texts of potentially relevant references. Two review authors (LL, LB) independently assessed the eligibility of retrieved papers. We resolved disagreements by discussion. We documented reasons for exclusion. See our PRISMA flow chart for details of the screening and selection process (Figure 1).

1.

Study flow diagram.

Data extraction and management

LL and LB independently extracted data on the characteristics of participants and interventions, study quality and endpoints using a piloted data extraction form designed according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). Differences between review authors were resolved by discussion or by appeal to a third review author (ZY or LJ).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We planned to assess the methodological quality using the Cochrane tool and the criteria specified in Chapter 8 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We planned to assess sequence generation; allocation concealment; blinding of outcome assessors; completeness of outcome data; selective outcome reporting; and other potential sources of bias. We planned that two review authors would assess these domains, with any disagreements resolved by consensus or by discussion with a third author. All judgements would be fully described. The conclusions would be presented in the 'Risk of bias' table and incorporated into the interpretation of review findings by means of sensitivity analyses.

Measures of treatment effect

We calculated dichotomous data (all the outcome measures in this review) using the Peto odds ratios (Peto OR). We presented the 95% confidence intervals (CIs) combined with Review Manager 5 software for meta‐analysis using a fixed‐effect model for all outcomes (RevMan 2014). We selected the Mantel‐Haenszel method because it performs well when event rates are very high.

Unit of analysis issues

The unit of analysis we are using is per woman. We anticipated that no unit of analysis issues would arise.

Dealing with missing data

We planned to contact trial authors to ask for any missing data. If suitable data were available, we would conduct intention‐to‐treat analysis. Where these were unobtainable, we planned that imputation of individual values would be undertaken for the primary outcomes only. Endometrial regression would be assumed not to have occurred in participants with an unreported outcome.

If studies reported sufficient detail to calculate mean differences (MDs) but gave no information on the associated standard deviation (SD), we planned to assume the outcome had a SD equal to the highest SD from other studies within the same analysis.

For other outcomes, we planned that we would analyse only the available data. Any imputation that was undertaken would be subjected to sensitivity analysis.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We planned to consider whether the clinical and methodological characteristics of the included studies were sufficiently similar for meta‐analysis to provide a meaningful summary. Statistical heterogeneity would be assessed by a measure of the I2 statistic. An I2 statistic greater than 50% would be taken to indicate substantial (high level) heterogeneity; 25% to 50% as moderate level; less than 25% as low level (Higgins 2002; Higgins 2003). If we had detected substantial heterogeneity, we would have explored possible explanations in sensitivity analyses. We were unable to assess heterogeneity, as we only identified one study.

Assessment of reporting biases

In view of the difficulty in detecting and correcting for publication bias and other reporting biases, we aimed to minimise their potential impact by ensuring a comprehensive search for eligible studies and by being alert for duplication of data. If there were 10 or more studies in an analysis, we planned to use a funnel plot to explore the possibility of small study effects (a tendency for estimates of the intervention effect to be more beneficial in smaller studies).

Data synthesis

If we had considered the RCTs not appropriate for pooled analysis, we would have only conducted a descriptive analysis. Otherwise, we planned that the data from primary studies would be combined using fixed‐effect models in the following comparisons.

-

LNG‐IUS versus oral progestin, stratified by duration and dose

low dose and short duration

high dose and short duration

low dose and long duration

high dose and long duration

-

LNG‐IUS (low dose) versus LNG‐IUS (high dose), stratified by duration

short duration

long duration

-

LNG‐IUS (short duration) versus LNG‐IUS (long duration), stratified by dose

low dose

high dose

An increase in the odds of a particular outcome, which may be beneficial (for example, endometrial regression) or detrimental (for example, adverse effects), would be displayed graphically in the meta‐analyses to the right of the centre‐line and a decrease in the odds of an outcome to the left of the centre‐line. We were unable to pool data in a meta‐analysis as there were insufficient trials that were eligible.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned to conduct subgroup analyses grouping the trials by the following variables.

Type of LNG‐IUS used

frameless LNG‐IUS, releasing 14 μg LNG/day

framed LNG–IUS, releasing 20 μg LNG/day

-

Type of atypical endometrial hyperplasia

simple hyperplasia with atypia

complex hyperplasia with atypia

We were to consider factors such as, age, the duration of LNG‐IUS intervention, length of follow‐up, different diagnostic criteria of atypical endometrial hyperplasia, and adjusted or unadjusted analysis in interpretation of any heterogeneity.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to use sensitivity analysis to explore the influence of the following factors on effect size.

If eligibility was restricted to studies without high risk of bias.

If alternative imputation strategies were adopted.

If a random‐effects model was adopted.

Overall quality of the body of evidence: 'Summary of findings' table

We prepared a 'Summary of findings' table using GRADEpro and Cochrane methods (GRADEpro GDT 2015; Higgins 2011). This table evaluated the overall quality of the body of evidence for the main review outcomes (regression rate, adverse effects). We assessed the quality of the evidence using GRADE criteria (risk of bias, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness and publication bias). Judgements about evidence quality (high, moderate, low or very low) were made by two review authors working independently, with disagreements resolved by discussion. Judgements were justified, documented, and incorporated into reporting of results for each outcome.

Results

Description of studies

We found only one study meeting all the inclusion criteria. This study was a parallel randomised controlled trial (RCT).

Results of the search

The search retrieved 149 articles. Five studies were potentially eligible and we retrieved the full text. We excluded four trials which initially seemed to conform to our inclusion criteria after assessing the full articles (Buttini 2009; Lee 2010; Pronin 2015; Vilos 2011). See Figure 1.

Included studies

Study design and setting

We identified only one RCT for inclusion in this review. This trial which was a parallel RCT conducted in Norway and recruitment took place over six years. During the study all participating women were investigated and treated in 17 different gynaecological centres in Norway. The follow‐up time was six months.

Participants

The trial included 153 women, but only 19 women had atypical endometrial hyperplasia; other women in this study had other types of endometrial hyperplasia. Among the 19 women with confirmed atypical endometrial hyperplasia, six were in the treatment group and 13 were in the control group.

Interventions

The trial (follow‐up: 6 months) compared the levonorgestrel‐releasing intrauterine system (LNG‐IUS), which releases 20 μg/day of the synthetic progestogen, levonorgestrel, with oral progestin (medroxyprogesterone (MPA) (10 mg, continuous or cyclic).

Outcomes

The included study reported both the primary outcomes of our review; rate of regression and adverse effects (nausea and vaginal bleeding).

Study funding: a grant given by the Norwegian Cancer Association, the Regional Research Board of Northern Norway (Helse Nord), and the Bank of North Norway funded the study. Annual funding is also granted from the University of Tromsø.

Interest: fees were from Bayer for invited lectures in scientific seminars for gynaecologists.

Excluded studies

We excluded four studies (Buttini 2009; Lee 2010; Pronin 2015; Vilos 2011) as they were non‐randomised trials.

Please refer to the Characteristics of excluded studies table for details of these studies.

Risk of bias in included studies

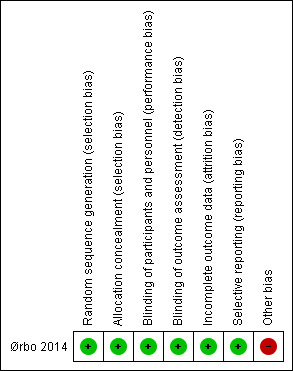

See Figure 2

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

We assessed this trial at low risk of selection bias related to sequence generation as it used a computer‐generated list of random numbers for eligible participants. We judged the trial to be at low risk of selection bias related to allocation concealment as it used central telephone randomisation.

Blinding

As all information of the study was not given to the main investigator before the study was closed, the trial was at low risk of performance bias. Detection bias was at low risk because the pathologists were blinded. Although the provider and participants were not blinded in regards to the clinical intervention, we considered the blinding of both groups unlikely to influence the outcomes.

Incomplete outcome data

This study reported 17 withdrawals, which equates to 10% of all the participants; the reasons for withdrawal were clear and included irregular bleeding, depression and other unspecific reasons. The primary authors performed a simple sensitivity analysis to ensure that withdrawals from the study did not influence the main conclusions of the study.

Selective reporting

We considered the trial to be at low risk of reporting bias. The primary outcomes and part of the secondary outcomes planned in the protocols were reported and these included rate of regression, nausea and irregular vaginal bleeding.

Other potential sources of bias

We judged the potential for other bias to be high. Our findings derive from a small subgroup within the main trial and the data are indirect. Only 19/153 participants met the criteria for this review and they are not balanced in terms of numbers in the intervention and control groups. The recruitment period for the study was long (6 years), due to the strict eligibility criteria. The number of participating centres was high, with possible differences between centres in reporting routines for adverse effects. Few women were postmenopausal or older than 52 years, so differences in response due to hormonal status were not considered.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

LNG‐IUS versus MPA

We have evaluated the quality of the evidence in a summary of findings table (see Table 1).

Primary outcomes

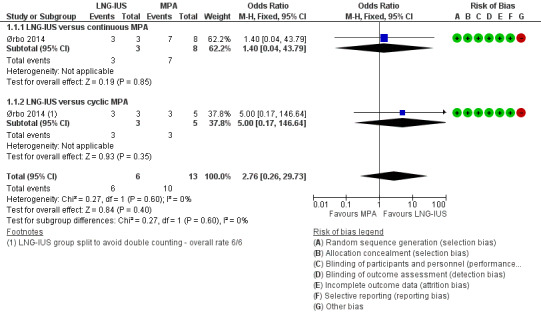

1. Rate of regression

Among the 19 women with atypical endometrial hyperplasia, after six months of treatment there was insufficient evidence to determine whether there was a difference in regression rates between the LNG‐IUS group and the progesterone group (odds ratio (OR) 2.76, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.26 to 29.73; 1 RCT subgroup, 19 women, very low‐quality evidence). The rate of regression was 100% in the LNG‐IUS group (6/6) and 77% in the progesterone group (10/13). (See Figure 3).

3.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Levonorgestrel‐releasing intrauterine system (LNG‐IUS) versus medroxyprogesterone (MPA) 10 mg, outcome: 1.1 Regression rate.

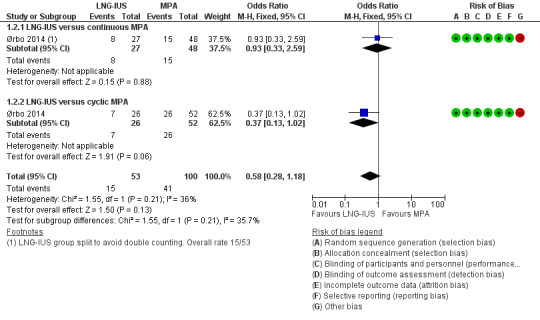

2. Adverse effects associated with hormonal problems

Nausea

Among the total study population (N = 153), over the six months' treatment the main adverse effect was nausea. There was no evidence of a difference between the groups in rates of nausea (OR 0.58, 95% CI 0.28 to 1.18; 1 RCT, 153 women, very low‐quality evidence; Figure 4).

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Levonorgestrel‐releasing intrauterine system (LNG‐IUS) versus medroxyprogesterone (MPA) 10 mg, outcome: 1.2 Nausea.

Secondary outcomes

3. Rate of recurrence

No data were available for this outcome.

4. Proportion of women undergoing hysterectomy

No data were available for this outcome.

5. Other adverse effects

Irregular vaginal bleeding

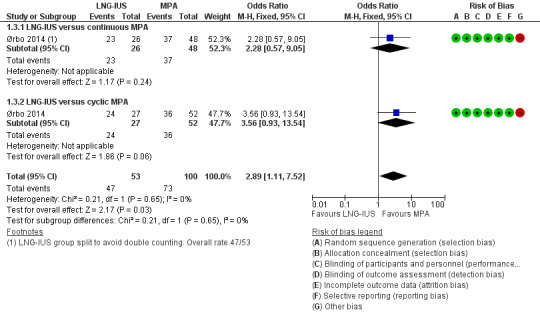

Among the total study population (N = 153), vaginal bleeding was more common in the LNG‐IUS group (OR 2.89, 95% CI 1.11 to 7.52; 1 RCT, 153 women, low‐quality evidence; Figure 5).

5.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Levonorgestrel‐releasing intrauterine system (LNG‐IUS) versus medroxyprogesterone (MPA) 10 mg, outcome: 1.3 Vaginal bleeding.

Except for nausea and irregular vaginal bleeding, none of the other adverse effects were reported.

6. Withdrawal from treatment because of adverse events

No data were available for this outcome.

7. Satisfaction with treatment

No data were available for this outcome.

8. Quality of life

No data were available for this outcome.

Other analyses

There were too few studies to conduct subgroup or sensitivity analyses, or to construct a funnel plot to investigate reporting bias.

The evidence was low‐ or very low‐quality, because the quality of the evidence was very seriously limited by imprecision and indirectness.

Discussion

Summary of main results

We only found one randomised controlled trial (RCT) with 153 women and only a subgroup of 19 women in this RCT met the eligibility criteria for this review. There was insufficient evidence to determine whether there was a difference in regression rates between the levonorgestrel‐releasing intrauterine system (LNG‐IUS) group and the progesterone group (medroxyprogesterone (MPA)) in this study. Among the total study population, over the six months' treatment, the main adverse effects were nausea and vaginal bleeding. There was no evidence of a difference between the groups in rates of nausea, but vaginal bleeding was more common in the LNG‐IUS group.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The included RCT used the 'gold standard' of pipelle biopsy or curettage to diagnose endometrial pathology. There were very few relevant data and the evidence is based on a single small trial of which only 19 of the 153 participants were eligible for this review. We do not consider that the evidence is generalisable to all women with atypical endometrial hyperplasia.

Quality of the evidence

We have used GRADE methodology to judge the quality of the evidence. The quality of the evidence was low or very low for all outcomes. The included study was at low risk of bias, but the quality of the evidence was very seriously limited by indirectness and imprecision, both associated with lack of data specifically relevant to women with atypical endometrial hyperplasia (Table 1).

Potential biases in the review process

We used a systematic search of the literature using multiple databases and trial registers not limited by date or language.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Among the excluded studies, three studies were observational studies. Two of these reported that the regression of complex atypical hyperplasia was attained at the 37th week and ninth month after LNG‐IUS insertion, respectively (Buttini 2009; Lee 2010). The third excluded study reported that two women required hysterectomy for endometrioid carcinoma (Vilos 2011), evident on endometrial biopsy at six months and 24 months, respectively. These studies reported that LNG‐IUS was a safe and effective method for treating non‐atypical endometrial hyperplasia. A fourth excluded study was a prospective study and reported that LNG‐IUS can be considered as a valid therapeutic option for young women of childbearing potential with atypical endometrial hyperplasia who wish to preserve their fertility (Pronin 2015), but whether LNG‐IUS could provide a safe and cost‐effective alternative to hysterectomy for atypical endometrial hyperplasia warranted further investigation.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

We did not find any randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of women with atypical endometrial hyperplasia, and our findings derive from a subgroup of 19 women in a larger RCT. All six women who used the LNG‐IUS system achieved regression of atypical hyperplasia, but there was insufficient evidence to draw any conclusions regarding the relative efficacy of LNG‐IUS versus oral progesterone (medroxyprogesterone (MPA)) in this group of women. When assessed in a population of women with any type of endometrial hyperplasia, there was no clear evidence of a difference between LNG‐IUS and oral progesterone (medroxyprogesterone (MPA)) in risk of nausea, but vaginal bleeding was more likely to occur in women using the LNG‐IUS.

Implications for research.

More well‐designed RCTs with sufficient power are needed to test the efficacy and safety of oral and intrauterine progestogens (medroxyprogesterone (MPA)) in treating atypical endometrial hyperplasia. Outcomes reported should include progression to cancer.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 23 August 2018 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | The addition of RCT evidence has changed the conclusions of this review |

| 23 August 2018 | New search has been performed | One RCT report has been added (Ørbo 2014) |

Acknowledgements

We thank Lin Dongtao for her contribution to the English revision process. We also thank Cochrane Gynaecology and Fertility (CGF) for providing us with support and advice.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Cochrane Gynaecology and Fertility (CGF) specialised register search strategy

Searched 19 November 2018

PROCITE platform

Keywords CONTAINS "Levonorgestrel"or"Levonorgestrel‐Therapeutic‐Use"or"levonorgestrel‐releasing intrauterine system" or "levonorgestrel‐releasing intrauterine device" or "levonorgestrel intrauterine system" or "intrauterine contraceptive devices" or "intrauterine device" or "intrauterine devices" or "Intrauterine Devices, Medicated" or "Mirena" or "LNG‐IUS" or "Nova T 380" or "LNG20" or "IUD" or Title CONTAINS"Levonorgestrel"or"Levonorgestrel‐Therapeutic‐Use"or"levonorgestrel‐releasing intrauterine system" or "levonorgestrel‐releasing intrauterine device" or "levonorgestrel intrauterine system" or "intrauterine contraceptive devices" or "intrauterine device" or "intrauterine devices" or "Intrauterine Devices, Medicated" or "Mirena" or "LNG‐IUS" or "Nova T 380"or "LNG20" or "IUD"

AND

Keywords CONTAINS "endometrial abnormalities" or "endometrial hyperplasia" or “endometrial thickness" or "endometrial vascularity" or "hyperplasia" or "proliferation" or "endometrial proliferation" or "endometrial safety" or "endometrial" or "endometrial bleeding" or "endometrial adhesions" or "endometrial activity" or "endometrial assessment" or "endometrial dysfunction" or "endometrioma" or "Endometrium" or "endometrium profile" or "endometrial parameters" or "endometrial pathology" or "endometrial response" or Title CONTAINS "endometrial abnormalities" or "endometrial hyperplasia" or "endometrial thickness" or "endometrial vascularity" or "hyperplasia" or "proliferation" or "endometrial proliferation" or "endometrial safety" (79 hits)

Appendix 2. CENTRAL via Cochrane Central Register of Studies Online (CRSO) search strategy

Searched 9 July 2018

Web Platform

#1 MESH DESCRIPTOR Levonorgestrel EXPLODE ALL TREES 561 #2 MESH DESCRIPTOR Intrauterine Devices, Medicated EXPLODE ALL TREES 300 #3 ((LNG‐IUS or LNG‐IUD)):TI,AB,KY 140 #4 Levonova*:TI,AB,KY 1 #5 Mirena*:TI,AB,KY 50 #6 Fibroplant*:TI,AB,KY 1 #7 d‐norgestrel:TI,AB,KY 17 #8 Levonorgestrel:TI,AB,KY 1043 #9 (LNG releasing):TI,AB,KY 4 #10 ((progest* adj5 intrauterine)):TI,AB,KY 24 #11 (intrauterine device*):TI,AB,KY 644 #12 (intra‐uterine system*):TI,AB,KY 5 #13 ((Skyla or Jaydess)):TI,AB,KY 3 #14 ((IUS or IUD)):TI,AB,KY 569 #15 #1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9 OR #10 OR #11 OR #12 OR #13 OR #14 1618 #16 MESH DESCRIPTOR Endometrial Hyperplasia EXPLODE ALL TREES 94 #17 ((endometri* adj4 hyperplas*)):TI,AB,KY 326 #18 ((atypi* adj2 hyperplas*)):TI,AB,KY 85 #19 ((atypi* adj2 endometri*)):TI,AB,KY 20 #20 ((endometri* adj2 proliferat*)):TI,AB,KY 87 #21 ((endometri* adj2 thick*)):TI,AB,KY 693 #22 ((endometri* adj5 (biops* or histology))):TI,AB,KY 623 #23 ((proliferat* adj4 endometri*)):TI,AB,KY 93 #24 endometrium:TI,AB,KY 1892 #25 ((endometri* N2 histopathology*)):TI,AB,KY 0 #26 ((endometri* adj5 effect*)):TI,AB,KY 790 #27 ((endometri* adj2 safety)):TI,AB,KY 87 #28 #16 OR #17 OR #18 OR #19 OR #20 OR #21 OR #22 OR #23 OR #24 OR #25 OR #26 OR #27 2552 #29 #15 AND #28 169

Appendix 3. MEDLINE search strategy

Searched from 1946 to 9 July 2018

OVID platform

1 exp Levonorgestrel/ (3954) 2 d‐norgestrel.tw. (250) 3 exp Intrauterine Devices, Medicated/ (3145) 4 Levonorgestrel.tw. (4191) 5 (LNG‐IUS or LNG‐IUD).tw. (722) 6 Levonova$.tw. (7) 7 Mirena$.tw. (260) 8 Femilis$.tw. (9) 9 Fibroplant$.tw. (20) 10 LNG releasing.tw. (36) 11 (progest$ adj5 intrauterine).tw. (406) 12 (progest$ adj5 intra‐uterine).tw. (30) 13 intrauterine device$.tw. (4849) 14 intra‐uterine device$.tw. (379) 15 intra‐uterine system$.tw. (40) 16 (Skyla or Jaydess).tw. (11) 17 (IUS or IUD).tw. (7525) 18 or/1‐17 (15134) 19 exp Endometrial Hyperplasia/ (3382) 20 (endometri$ adj4 hyperplas$).tw. (4330) 21 (atypi$ adj2 hyperplas$).tw. (4795) 22 (atypi$ adj2 endometri$).tw. (836) 23 (endometri$ adj2 proliferat$).tw. (1984) 24 (endometri$ adj2 thick$).tw. (2639) 25 (endometri$ adj5 (biops$ or histology)).tw. (5248) 26 (proliferat$ adj4 endometri$).tw. (3165) 27 endometrium.tw. (25354) 28 (endometri$ adj2 histopatholog$).tw. (241) 29 (endometri$ adj5 effect$).tw. (4469) 30 (endometri$ adj2 safety).tw. (169) 31 or/19‐30 (38678) 32 randomized controlled trial.pt. (462668) 33 controlled clinical trial.pt. (94066) 34 randomized.ab. (404362) 35 placebo.tw. (194164) 36 clinical trials as topic.sh. (185923) 37 randomly.ab. (280798) 38 trial.ti. (181286) 39 (crossover or cross‐over or cross over).tw. (75223) 40 or/32‐39 (1163027) 41 exp animals/ not humans.sh. (4399971) 42 40 not 41 (1071641) 43 18 and 31 and 42 (189)

Appendix 4. Embase search strategy

Searched from 1980 to 19 November 2018

OVID platform

1 exp LEVONORGESTREL/ (10435) 2 d‐norgestrel.tw. (98) 3 exp intrauterine contraceptive device/ (15738) 4 Levonorgestrel.tw. (4988) 5 (LNG‐IUS or LNG‐IUD).tw. (1104) 6 Levonova$.tw. (37) 7 Mirena$.tw. (1382) 8 Femilis$.tw. (16) 9 Fibroplant$.tw. (25) 10 LNG releasing.tw. (39) 11 (progest$ adj5 intrauterine).tw. (457) 12 (progest$ adj5 intra‐uterine).tw. (54) 13 intrauterine device$.tw. (5454) 14 intra‐uterine device$.tw. (482) 15 intra‐uterine system$.tw. (81) 16 (Skyla or Jaydess).tw. (72) 17 (IUS or IUD).tw. (7043) 18 or/1‐17 (25795) 19 exp endometrium hyperplasia/ (6628) 20 (endometri$ adj4 hyperplas$).tw. (5464) 21 (proliferat$ adj4 endometri$).tw. (3891) 22 (endometri$ adj4 atypi$).tw. (1904) 23 (atypi$ adj2 hyperplas$).tw. (6423) 24 (atypi$ adj2 endometri$).tw. (1194) 25 (endometri$ adj2 proliferat$).tw. (2476) 26 (endometri$ adj2 thick$).tw. (4200) 27 (endometri$ adj5 (biops$ or histology)).tw. (7134) 28 (proliferat$ adj4 endometri$).tw. (3891) 29 endometrium.tw. (29614) 30 (endometri$ adj2 histopatholog$).tw. (357) 31 (endometri$ adj5 effect$).tw. (5762) 32 (endometri$ adj2 safety).tw. (225) 33 or/19‐32 (48599) 34 Clinical Trial/ (914488) 35 Randomized Controlled Trial/ (442991) 36 exp randomization/ (73467) 37 Single Blind Procedure/ (26529) 38 Double Blind Procedure/ (134845) 39 Crossover Procedure/ (50787) 40 Placebo/ (290654) 41 Randomi?ed controlled trial$.tw. (155702) 42 Rct.tw. (23717) 43 random allocation.tw. (1618) 44 randomly allocated.tw. (26908) 45 allocated randomly.tw. (2208) 46 (allocated adj2 random).tw. (776) 47 Single blind$.tw. (18850) 48 Double blind$.tw. (169923) 49 ((treble or triple) adj blind$).tw. (661) 50 placebo$.tw. (246694) 51 prospective study/ (372549) 52 or/34‐51 (1713018) 53 case study/ (46479) 54 case report.tw. (325185) 55 abstract report/ or letter/ (989575) 56 or/53‐55 (1353513) 57 52 not 56 (1668797) 58 18 and 33 and 57 (461)

Appendix 5. PsycINFO search strategy

Searched from 1806 to 9 July 2018

OVID platform

1 exp Intrauterine Devices/ (107) 2 d‐norgestrel.tw. (1) 3 Levonorgestrel.tw. (81) 4 (LNG‐IUS or LNG‐IUD).tw. (21) 5 Levonova$.tw. (0) 6 Mirena$.tw. (9) 7 Femilis$.tw. (1) 8 Fibroplant$.tw. (0) 9 LNG releasing.tw. (1) 10 (progest$ adj5 intrauterine).tw. (10) 11 (progest$ adj5 intra‐uterine).tw. (1) 12 intrauterine device$.tw. (220) 13 intra‐uterine device$.tw. (7) 14 intra‐uterine system$.tw. (0) 15 (Skyla or Jaydess).tw. (0) 16 (IUS or IUD).tw. (277) 17 or/1‐16 (479) 18 (endometrial or endometrium).tw. (342) 19 17 and 18 (13)

Appendix 6. CINAHL search strategy

Searched from 1961 to 9 July 2018

EBSCO platform

| # | Query | Results |

| S49 | S20 AND S36 AND S48 | 189 |

| S48 | S37 OR S38 OR S39 OR S40 OR S41 OR S42 OR S43 OR S44 OR S45 OR S46 OR S47 | 1,133,933 |

| S47 | TX allocat* random* | 6,849 |

| S46 | (MH "Quantitative Studies") | 15,720 |

| S45 | (MH "Placebos") | 10,129 |

| S44 | TX placebo* | 45,889 |

| S43 | TX random* allocat* | 6,849 |

| S42 | (MH "Random Assignment") | 42,878 |

| S41 | TX randomi* control* trial* | 124,700 |

| S40 | TX ( (singl* n1 blind*) or (singl* n1 mask*) ) or TX ( (doubl* n1 blind*) or (doubl* n1 mask*) ) or TX ( (tripl* n1 blind*) or (tripl* n1 mask*) ) or TX ( (trebl* n1 blind*) or (trebl* n1 mask*) ) | 888,594 |

| S39 | TX clinic* n1 trial* | 205,729 |

| S38 | PT Clinical trial | 80,011 |

| S37 | (MH "Clinical Trials+") | 213,619 |

| S36 | S21 OR S22 OR S23 OR S24 OR S25 OR S26 OR S27 OR S28 OR S29 OR S30 OR S31 OR S32 OR S33 OR S34 OR S35 | 3,820 |

| S35 | TX (IUS or IUD) | 1,184 |

| S34 | TX (Skyla or Jaydess) | 75 |

| S33 | TX intrauterine system* | 472 |

| S32 | TX intra‐uterine system* | 14 |

| S31 | TX intra‐uterine device* | 39 |

| S30 | TX intrauterine device* | 2,531 |

| S29 | TX progest* N5 intra‐uterine | 6 |

| S28 | TX (progest* N5 intrauterine) | 81 |

| S27 | TX LNG releasing | 79 |

| S26 | TX LNG‐IUD | 28 |

| S25 | TX LNG‐IUS | 129 |

| S24 | TX mirena | 100 |

| S23 | TX levonorgestrel | 1,433 |

| S22 | (MM "Intrauterine Devices") | 1,228 |

| S21 | (MM "Levonorgestrel") | 657 |

| S20 | S1 OR S2 OR S3 OR S4 OR S5 OR S6 OR S7 OR S8 OR S9 OR S10 OR S11 OR S12 OR S13 OR S14 OR S15 OR S16 OR S17 OR S18 OR S19 | 37,681 |

| S19 | TX (endometri* N2 safety) | 57 |

| S18 | TX(endometri* N5 effect*) | 745 |

| S17 | TX (endometri* N2 histopatholog*) | 41 |

| S16 | TX endometrium | 2,034 |

| S15 | TX(endometri* N2 thick*) | 343 |

| S14 | TX(endometri* N2 proliferat*) | 113 |

| S13 | TX(complex N2 hyperplas*) | 73 |

| S12 | TX(simple N2 hyperplas*) | 40 |

| S11 | TX(atypi* N2 endometri*) | 115 |

| S10 | TX(atypi* N2 hyperplas*) | 418 |

| S9 | TX (endometri* N2 effect*) | 483 |

| S8 | TX (endometri* N2 safety) | 57 |

| S7 | TX endometrium | 2,034 |

| S6 | TX (bleed* or spotting*) | 26,073 |

| S5 | TX (hysteroscop* or hysterectomy) | 8,208 |

| S4 | TX (endometri* N5 (biops$ or histology)) | 149 |

| S3 | TX (endometri* N3 cancer*) | 2,597 |

| S2 | TX (endometri* N3 carcinoma) | 691 |

| S1 | TX endometri* N2 hyperplas* | 336 |

Appendix 7. CNKI search strategy

Searched 9 July 2018

Web platform

Levonorgestrel

Intrauterine Devices

Mirena

Or 1‐3

endometrial hyperplasis

endometrial simple hyperplasia

endometrial complex hyperplasia

endometrial atypia

or 5‐8

4 and 9

and randomised controlled trial

Appendix 8. CBM search strategy

Searched 9 July 2018

Web platform

Levonorgestrel

Intrauterine Devices

Mirena

or 1‐3

endometrium

endometrial simple hyperplasia

endometrial complex hyperplasia

endometrial atypia

or 5‐8

4 and 9

randomised controlled trial

controlled clinical trial

Randomized

placebo

clinical trials as topic

randomly

trial

(crossover or cross‐over or cross over)

or/11‐18

exp animals/ not humans.sh.

19 not 20

10 and 21

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Levonorgestrel‐releasing intrauterine system (LNG‐IUS) versus medroxyprogesterone (MPA) 10 mg.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Regression rate | 1 | 19 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.76 [0.26, 29.73] |

| 1.1 LNG‐IUS versus continuous MPA | 1 | 11 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.4 [0.04, 43.79] |

| 1.2 LNG‐IUS versus cyclic MPA | 1 | 8 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 5.0 [0.17, 146.64] |

| 2 Nausea | 1 | 153 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.58 [0.28, 1.18] |

| 2.1 LNG‐IUS versus continuous MPA | 1 | 75 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.93 [0.33, 2.59] |

| 2.2 LNG‐IUS versus cyclic MPA | 1 | 78 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.37 [0.13, 1.02] |

| 3 Vaginal bleeding | 1 | 153 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.89 [1.11, 7.52] |

| 3.1 LNG‐IUS versus continuous MPA | 1 | 74 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.28 [0.57, 9.05] |

| 3.2 LNG‐IUS versus cyclic MPA | 1 | 79 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.56 [0.93, 13.54] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Levonorgestrel‐releasing intrauterine system (LNG‐IUS) versus medroxyprogesterone (MPA) 10 mg, Outcome 1 Regression rate.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Levonorgestrel‐releasing intrauterine system (LNG‐IUS) versus medroxyprogesterone (MPA) 10 mg, Outcome 2 Nausea.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Levonorgestrel‐releasing intrauterine system (LNG‐IUS) versus medroxyprogesterone (MPA) 10 mg, Outcome 3 Vaginal bleeding.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Ørbo 2014.

| Methods | This trial was a parallel randomised controlled trial and the timing of the study was six years. Women were randomly assigned to LNG‐IUS or oral MPA | |

| Participants | 153 women aged 30–70 years with low‐ or medium‐risk endometrial hyperplasia who met inclusion criteria. Only 19 women derived from this larger study were histologically confirmed with atypical complex hyperplasia before treatment and thus met the inclusion criteria for this review. The number of women allocated to the LNG‐IUS group were six, the number of women allocated to the MPA group were 13. | |

| Interventions | The trial compared the LNG‐IUS (20 micrograms levonorgestrel per 24 hours) with oral progestin (MPA). Progestin was cyclic (10 mg administered for 10 days per cycle) or continuous (10 mg daily). The interventions were administered for six months. | |

| Outcomes | The primary outcome was endometrial hyperplasia or not, diagnosed with endometrial biopsy assessed by light microscopy. The reference standard for evaluation of endometrial hyperplasia is the modified WHO94 classification. Secondary outcomes included reported adverse effects with focus on nausea (only sometimes and trivial versus often and annoying), vaginal bleeding (> or < 10 days per month). | |

| Notes | Study funding: a grant given by the Norwegian Cancer Association, the Regional Research Board of Northern Norway (Helse Nord), and the Bank of North Norway funded the study. Annual funding is also granted from the University of Tromsø. Interest: fees were from Bayer for invited lectures in scientific seminars for gynaecologists |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | A computer‐generated list of random numbers was used. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | The trial was at low risk of selection bias related to allocation concealment, as central telephone randomisation was used. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Although the provider and participants were not blinded regarding the clinical intervention, the blinding of both was considered unlikely to influence the outcomes. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | The trial was rated as low risk of performance bias and detection bias because the pathologists were blinded. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | This study reported 17 withdrawals and the reasons of withdrawal were clear. A simple sensitivity analysis was performed by the authors of the primary study, to ensure that withdrawals from the study did not influence the main conclusions of the study. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All expected outcomes were reported. |

| Other bias | High risk | Our findings derive from a small subgroup within the main trial and that the data are indirect. Only 19/153 participants met the criteria for this review and they are not balanced in terms of numbers in the intervention and control groups. The recruitment period for the study was long (6 years), due to the strict eligibility criteria. The number of participating centres was high, with possible differences between centres in reporting routines for adverse effects. Few women were postmenopausal or older than 52 years, so differences in response due to hormonal status were not considered. |

LNG‐IUS: levonorgestrel‐releasing intrauterine system MPA: medroxyprogesterone

GnRH: Gonadotropin‐releasing hormone

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Buttini 2009 | Non‐randomised clinical trial. A retrospective study of 21 cases of endometrial hyperplasia without any randomisation, control or blinding. |

| Lee 2010 | Non‐randomised clinical trial. An observational study to evaluate the effectiveness of the levonorgestrel‐releasing intrauterine system for endometrial hyperplasia after three months of therapy. |

| Pronin 2015 | Non‐randomised clinical trial. A prospective study of 38 cases of atypical endometrial hyperplasia without any randomisation, control or blinding. |

| Vilos 2011 | Non‐randomised clinical trial. A retrospective study of 56 cases of endometrial hyperplasia without any randomisation, control or blinding. |

Differences between protocol and review

For the 2018 update, we agreed with Cochrane Gynaecology and Fertility to extend the scope of this review to include oral progestogens, in the event of evidence from future trials. This led to a change in the title of this review: it was previously 'Levonorgestrel‐releasing intrauterine system for atypical endometrial hyperplasia'.

Contributions of authors

Zheng Ying and Li Jing provided clinical expertise and designed the protocol. Luo Li, Luo Bing and Zhang Heng assisted with writing the protocol and review. Neil Sidell was responsible for the English writing.

Sources of support

Internal sources

-

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, West China Second University Hospital, Sichuan University, China.

Advice and support of department and hospital, and salary

External sources

-

Cochrane Gynaecology and Fertility Group, New Zealand.

Support of search strategy, advice and statistical analysis

Declarations of interest

Li Jing, Luo Bing, Luo Li, Neil Sidell, Zhang Heng and Zheng Ying have no interests to declare.

New search for studies and content updated (conclusions changed)

References

References to studies included in this review

Ørbo 2014 {published data only}

- Ørbo A, Vereide AB, Arnes M, Pettersen I, Straume B. Levonorgestrel‐impregnated intrauterine device as treatment for endometrial hyperplasia: a national multicentre randomised trial. BJOG 2014;121(4):477‐86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Buttini 2009 {published data only}

- Buttini MJ, Jordan SJ, Webb PM. The effect of the levonorgestrel releasing intrauterine system on endometrial hyperplasia: an Australian study and systematic review. The Australian & New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology 2009;49(3):316‐22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lee 2010 {published data only}

- Lee SY, Kim MK, Park H, Yoon BS, Seong SJ, Kang JH, et al. The effectiveness of levonorgestrel releasing intrauterine system in the treatment of endometrial hyperplasia in Korean women. Journal of Gynecologic Oncology 2010;21(2):102‐5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Pronin 2015 {published data only}

- Pronin SM, Novikova OV, Andreeva JY, Novikova EG. Fertility‐sparing treatment of early endometrial cancer and complex atypical hyperplasia in young women of childbearing potential. International Journal of Gynecological Cancer 2015;25(6):1010‐14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Vilos 2011 {published data only}

- Vilos GA, Marks J, Tureanu V, Abu‐Rafea B, Vilos AG. The levonorgestrel intrauterine system is an effective treatment in selected obese women with abnormal uterine bleeding. Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology 2011;18(1):75‐80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Additional references

Chi 1994

- Chi IC, Farr G. The non‐contraceptive of the levonorgestrel‐releasing intrauterine device. Advances in Contraception 1994;10(4):271‐85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cozza 2017

- Cozza G, Pinto A, Giovanaie V, Bianchi P, Guarino A, Marziani R, et al. Comparative effective and impact on health‐related quality of life of hysterectomy vs. levonorgestrel intra‐uterine system for abnormal uterine bleeding. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2017;21(9):2255‐2260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Critchley 2007

- Guttinger A, Critchley HO. Endometrial effects of intrauterine levonorgestrel. Contraception 2007;75(6 Suppl):93‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Dominick 2015

- Dominick S, Hickey M, Chin J, Su HI. Levonorgestrel intrauterine system for endometrial protection in women with breast cancer on adjuvant tamoxifen. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2015, Issue 12. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD007245.pub3] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Eralil 2016

- Eralil GJ. The effectiveness of levorgestrel‐releasing intrauterine system in the treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding. J Obstet Gynaecol India 2016;66((Suppl 1)):502‐12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

GRADEpro GDT 2015 [Computer program]

- GRADE Working Group, McMaster University. GRADEpro GDT. Version accessed 26 July 2017. Hamilton (ON): GRADE Working Group, McMaster University, 2015. Available at gradepro.org.

Guo 1993

- Guo LN. Atypical hyperplasia and complex hyperplasia of endometrium in women of reproductive age. Zhonghua Fu Chan Ke Za Zhi 1993;28(12):725‐7, 760. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Higgins 2002

- Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta‐analysis. Statistics in Medicine 2002;21:1539‐58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Higgins 2003

- Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta‐analyses. BMJ 2003;327:557‐60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Higgins 2011

- Higgins JP, Green S, editor(s). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 (updated March 2011). The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from handbook.cochrane.org.

Kullander 1992

- Kullander S. Treatment of endometrial cancer with GnRH analogs. Recent Results in Cancer Research 1992;124:69‐73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kurman 1985

- Kurman RJ, Kaminski PF, Norris HJ. The behavior of endometrial hyperplasia. A long‐term study of "untreated" hyperplasia in 170 patients. Cancer 1985;56(2):403‐12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Luukkainen 1991

- Luukkainen T. Levonorgestrel‐releasing intrauterine device. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1991;626:43‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Qi 2008

- Qi X, Zhao W, Duan Y, Li Y. Successful pregnancy following insertion of a levonorgestrel‐releasing intrauterine system in two infertile patients with complex atypical endometrial hyperplasia. Gynecologic and Obstetric Investigation 2008;65(4):266‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Randall 1997

- Randall TC, Kurman RJ. Progestin treatment of atypical hyperplasia and well‐differentiated carcinoma of the endometrium in women under age 40. Obstetrics and Gynecology 1997;90(3):434‐40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

RevMan 2014 [Computer program]

- Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration. Review Manager 5 (RevMan 5). Version 5.3. Copenhagen: Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014.

Sitruk‐Ware 2004

- Sitruk‐Ware R. Pharmacological profile of progestins. Maturitas 2004;47(4):277‐83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sturridge 1996

- Sturridge F, Guillebaud J. A risk‐benefit assessment of the levonorgestrel‐releasing intrauterine system. Drug Safety 1996;15(6):430‐40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Wildemeersch 2003

- Wildemeersch D, Dhont M. Treatment of non‐atypical and atypical endometrial hyperplasia with a levonorgestrel‐releasing intrauterine system. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2003;188(5):1297‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Wildemeersch 2007

- Wildemeersch D, Janssens D, Pylyser K, Wever DE, Verbeeck G, Dhont M, et al. Management of patients with non‐atypical and atypical endometrial hyperplasia with a levonorgestrel‐releasing intrauterine system: long‐term follow‐up. Maturitas 2007;57(2):210‐3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Xiao 1990

- Xiao BL, Zhou LY, Zhang XL, Jia MC, Luukkainen T, Allonen H. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic studies of levonorgestrel‐releasing intrauterine device. Contraception 1990;41(4):353‐62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to other published versions of this review

Luo 2011

- Luo L, Luo B, Zheng Y, Zhang H, Li J, Sidell N. Levonorgestrel‐releasing intrauterine system for atypical endometrial hyperplasia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2011, Issue 11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Luo 2013

- Luo L, Luo B, Zheng Y, Zhang H, Li J, Sidell N. Levonorgestrel‐releasing intrauterine system for atypical endometrial hyperplasia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2013, Issue 6. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD009458.pub2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]