Abstract

Background

Observational studies suggest higher pregnancy rates after the hysteroscopic removal of endometrial polyps, submucous fibroids, uterine septum or intrauterine adhesions, which are present in 10% to 15% of women seeking treatment for subfertility.

Objectives

To assess the effects of the hysteroscopic removal of endometrial polyps, submucous fibroids, uterine septum or intrauterine adhesions suspected on ultrasound, hysterosalpingography, diagnostic hysteroscopy or any combination of these methods in women with otherwise unexplained subfertility or prior to intrauterine insemination (IUI), in vitro fertilisation (IVF) or intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI).

Search methods

We searched the following databases from their inception to 16 April 2018; The Cochrane Gynaecology and Fertility Group Specialised Register, the Cochrane Central Register of Studies Online, ; MEDLINE, Embase , CINAHL , and other electronic sources of trials including trial registers, sources of unpublished literature, and reference lists. We handsearched the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) conference abstracts and proceedings (from 1 January 2014 to 12 May 2018) and we contacted experts in the field.

Selection criteria

Randomised comparison between operative hysteroscopy versus control for unexplained subfertility associated with suspected major uterine cavity abnormalities.

Randomised comparison between operative hysteroscopy versus control for suspected major uterine cavity abnormalities prior to medically assisted reproduction.

Primary outcomes were live birth and hysteroscopy complications. Secondary outcomes were pregnancy and miscarriage.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed studies for inclusion and risk of bias, and extracted data. We contacted study authors for additional information.

Main results

Two studies met the inclusion criteria.

1. Randomised comparison between operative hysteroscopy versus control for unexplained subfertility associated with suspected major uterine cavity abnormalities.

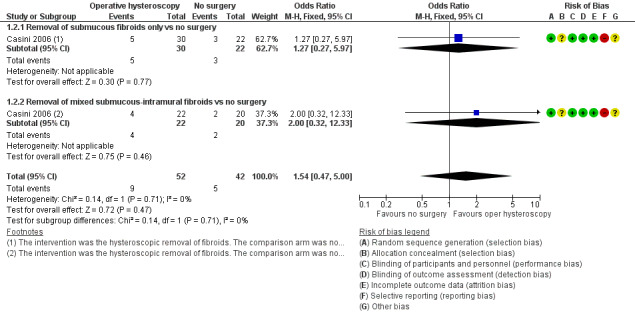

In women with otherwise unexplained subfertility and submucous fibroids, we were uncertain whether hysteroscopic myomectomy improved the clinical pregnancy rate compared to expectant management (odds ratio (OR) 2.44, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.97 to 6.17; P = 0.06, 94 women; very low‐quality evidence). We are uncertain whether hysteroscopic myomectomy improves the miscarriage rate compared to expectant management (OR 1.54, 95% CI 0.47 to 5.00; P = 0.47, 94 women; very low‐quality evidence). We found no data on live birth or hysteroscopy complication rates. We found no studies in women with endometrial polyps, intrauterine adhesions or uterine septum for this randomised comparison.

2. Randomised comparison between operative hysteroscopy versus control for suspected major uterine cavity abnormalities prior to medically assisted reproduction.

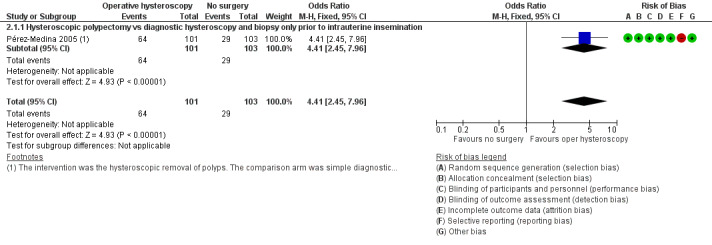

The hysteroscopic removal of polyps prior to IUI may have improved the clinical pregnancy rate compared to diagnostic hysteroscopy only: if 28% of women achieved a clinical pregnancy without polyp removal, the evidence suggested that 63% of women (95% CI 45% to 89%) achieved a clinical pregnancy after the hysteroscopic removal of the endometrial polyps (OR 4.41, 95% CI 2.45 to 7.96; P < 0.00001, 204 women; low‐quality evidence). We found no data on live birth, hysteroscopy complication or miscarriage rates in women with endometrial polyps prior to IUI. We found no studies in women with submucous fibroids, intrauterine adhesions or uterine septum prior to IUI or in women with all types of suspected uterine cavity abnormalities prior to IVF/ICSI.

Authors' conclusions

Uncertainty remains concerning an important benefit with the hysteroscopic removal of submucous fibroids for improving the clinical pregnancy rates in women with otherwise unexplained subfertility. The available low‐quality evidence suggests that the hysteroscopic removal of endometrial polyps suspected on ultrasound in women prior to IUI may improve the clinical pregnancy rate compared to simple diagnostic hysteroscopy. More research is needed to measure the effectiveness of the hysteroscopic treatment of suspected major uterine cavity abnormalities in women with unexplained subfertility or prior to IUI, IVF or ICSI.

Plain language summary

Hysteroscopy for treating suspected abnormalities of the cavity of the womb in women having difficulty becoming pregnant

Review question

Cochrane authors reviewed the evidence about the effect of the hysteroscopic treatment of suspected abnormalities of the cavity of the womb in women having difficulty becoming pregnant.

Background

Human life starts when a fertilised egg has successfully implanted in the inner layer of the cavity of the womb. It is believed that abnormalities originating from this site, such as polyps (abnormal growth of tissue), fibroids (non‐cancerous growth), septa (upside‐down, triangular‐shaped piece of tissue which divides the womb) or adhesions (scar tissue that sticks the walls of the womb together), may disturb this event. The removal of these abnormalities by doing a hysteroscopy using a very small diameter inspecting device might therefore increase the chance of becoming pregnant either spontaneously or after specialised fertility treatment, such as insemination or in vitro fertilisation.

Study characteristics

We found two studies. The first study compared the removal of fibroids versus no removal in 94 women wishing to become pregnant spontaneously from January 1998 to April 2005. The second study compared the removal of polyps versus simple hysteroscopy only in 204 women before insemination with husband's sperm from January 2000 to February 2004. The evidence is current to April 2018. Neither study reported funding sources.

Key results

In women with fibroids wishing to become pregnant spontaneously we were uncertain whether removal of the fibroids improved the pregnancy or miscarriage rate compared to usual management: uncertainty remains because the number of women (94) and the number of pregnancies (30) were too small and the quality of the evidence was very low. We found no data on live birth or complications due to surgery. We found no studies on women with polyps, septa or adhesions.

The hysteroscopic removal of polyps prior to intrauterine insemination (IUI; a fertility treatment where sperm is placed inside a woman's womb to fertilise the egg) is may improve the pregnancy rate compared to not removing polyps. If 28% of women become pregnant without surgery, the evidence suggests that about 63% of women will become pregnant following removal of polyps. We found no data on number of live births, hysteroscopy complications or miscarriage rates prior to IUI. We retrieved no studies in women before other fertility treatments.

More studies are needed before hysteroscopy can be proposed as a fertility‐enhancing procedure in the general population of women having difficulty becoming pregnant.

Quality of the evidence

The quality of the evidence retrieved was very low to low due to the limited number of participants and the poor design of the studies.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Subfertility is "a disease of the reproductive system defined by the failure to achieve a clinical pregnancy after 12 months or more of regular unprotected sexual intercourse" according to the International Committee for Monitoring Assisted Reproductive Technology (ICMART) and the World Health Organization (WHO) revised glossary of assisted reproductive technology (Zegers‐Hochschild 2017) (see: www.icmartivf.org/ivf‐glossary.html). It is estimated that 72.4 million women are subfertile and that 40.5 million of these women are currently seeking fertility treatment (Boivin 2007). Unexplained subfertility usually refers to a diagnosis (or lack of diagnosis) made in couples in whom all the standard investigations such as tests of ovulation, tubal patency and semen analysis are normal: it can be found in as many as 30% to 40% of subfertile couples (Ray 2012).

The evaluation of the uterine cavity seems a basic step in the investigation of all subfertile women since the uterine cavity and its inner layer, the endometrium, are assumed to be important for the implantation of the human embryo, called a blastocyst. Nevertheless, the complex mechanisms leading to successful implantation are still poorly understood (Taylor 2008). Despite the huge investment in research and developments of the technologies and biology involved in medically assisted reproduction (MAR), the maximum implantation rate per embryo transferred still remains only 30% (Andersen 2008). The different phases of the implantation process are established by the complex interchange between the blastocyst and the endometrium (Singh 2011).

Major uterine cavity abnormalities can be found in 10% to 15% of women seeking treatment for subfertility; they usually consist of the presence of excessive normal uterine tissue (Wallach 1972). The most common acquired uterine cavity abnormality is an endometrial polyp. This benign, endometrial stalk‐like mass protrudes into the uterine cavity and has its own vascular supply. Depending on the population under study and the applied diagnostic test, endometrial polyps can be found in 1% to 41% of the subfertile population (Silberstein 2006). A fibroid is an excessive growth originating from the muscular part of the uterine cavity. Fibroids are present in 2.4% of subfertile women without any other obvious cause of subfertility (Donnez 2002). A submucous fibroid is located underneath the endometrium and is thought to interfere with fertility by deforming the uterine cavity. Intrauterine adhesions are fibrous tissue strings connecting parts of the uterine wall. They are commonly caused by inflammation or iatrogenic tissue damage (meaning involuntarily caused by a physician's intervention, for example an aspiration curettage after miscarriage) and are present in 0.3% to 14% of subfertile women (Fatemi 2010).

A septate uterus is a congenital malformation in which the longitudinal band separating the left and right Müllerian ducts, which form the uterus in the human female foetus, has not been entirely resorbed. A uterine septum is present in 1% to 3.6% of women with otherwise unexplained subfertility (Saravelos 2008).

Ultrasonography (US), preferably transvaginally (TVS), is used to screen for possible endometrium or uterine cavity abnormalities in the work‐up of subfertile women. This evaluation can be expanded with hysterosalpingography (HSG), saline infusion/gel instillation sonography (SIS/GIS) and diagnostic hysteroscopy. Diagnostic hysteroscopy is generally considered as the gold standard procedure for the assessment of the uterine cavity since it enables direct visualisation; moreover, treatment of intrauterine pathology can be done in the same setting (Bettocchi 2004). Nevertheless, even for experienced gynaecologists, the hysteroscopic diagnosis of the major uterine cavity abnormalities may be problematic (Kasius 2011a).

Description of the intervention

Hysteroscopy is performed for the evaluation, or for the treatment of the uterine cavity, tubal ostia and endocervical canal in women with uterine bleeding disorders, Müllerian tract anomalies, retained intrauterine contraceptives or other foreign bodies, retained products of conception, desire for sterilisation, recurrent miscarriage and subfertility. If the procedure is intended for evaluating the uterine cavity only, it is called a diagnostic hysteroscopy. If the observed pathology requires further treatment, the procedure is called an operative hysteroscopy. In everyday practice, a diagnostic hysteroscopy confirming the presence of pathology will be followed by an operative hysteroscopy in a symptomatic woman.

Hysteroscopy allows the direct visualisation of the uterine cavity through a rigid, semi‐rigid or flexible endoscope. The hysteroscope consists of a rigid telescope with a proximal eyepiece and a distal objective lens that may be angled at 0° to allow direct viewing or offset at various angles to provide a fore‐oblique view. Advances in fibreoptic technology have led to the miniaturisation of the telescopes without compromising the image quality. The total working diameters of modern diagnostic hysteroscopes are typically 2.5 mm to 4.0 mm. Operative hysteroscopy requires adequate visualisation through a continuous fluid circulation using an inflow and an outflow channel. The outer diameters of modern operative hysteroscopes have been reduced to a diameter between 4.0 mm and 5.5 mm. The sheath system contains one or two 1.6 mm to 2.0 mm working channels for the insertion of small grasping or biopsy forceps, scissors, myoma fixation instruments, retraction loops, morcellators (surgical instruments used to divide and remove tissue during endoscopic surgery) and aspiration cannulae, or unipolar or bipolar electrodiathermy instruments.

Most diagnostic and many operative procedures can be done in a clinic setting using local anaesthesia and fluid distension media, while more complex procedures are generally performed as day surgery under general anaesthesia (Clark 2005). Operative hysteroscopic procedures require a complex instrumentation setup, special training of the surgeon, and appropriate knowledge and management of complications (Campo 1999).

Although complications from hysteroscopy are rare, they can be potentially life threatening. One multicentre study including 13,600 diagnostic and operative hysteroscopic procedures performed in 82 centres reported a complication rate of 0.28%. Diagnostic hysteroscopy had a significantly lower complication rate compared to operative hysteroscopy (0.13% with diagnostic versus 0.95% with operative). The most common complication of both types of hysteroscopy was uterine perforation (0.13% with diagnostic versus 0.76% with operative). Fluid intravasation occurred almost exclusively in operative procedures (0.02%). Intrauterine adhesiolysis was associated with the highest incidence of complications (4.5%); all of the other procedures had complication rates of less than 1% (Jansen 2000).

How the intervention might work

It is assumed that major uterine cavity abnormalities may interfere with factors that regulate the blastocyst‐endometrium interplay, for example hormones and cytokines, precluding the possibility of pregnancy. Many hypotheses have been formulated in the literature of how endometrial polyps (Shokeir 2004; Silberstein 2006; Taylor 2008; Yanaihara 2008), submucous fibroids (Pritts 2001; Somigliana 2007; Taylor 2008), intrauterine adhesions (Yu 2008), and uterine septum (Fedele 1996) are likely to disturb the implantation of the human embryo; nevertheless, the precise mechanisms of action through which each one of these major uterine cavity abnormalities affects this essential reproductive process are poorly understood. The foetal‐maternal conflict hypothesis tries to explain how a successful pregnancy may establish itself despite the intrinsic genomic instability of human embryos through the specialist functions of the endometrium, in particular its capacity for cyclic spontaneous decidualisation, shedding and regeneration. An excellent indepth review linking basic research of human implantation with clinical practice can be found elsewhere (Lucas 2013).

For endometrial polyps, submucous fibroids, intrauterine adhesions and uterine septum, observational studies have shown a clear improvement in the spontaneous pregnancy rate after the hysteroscopic removal of the abnormality (Taylor 2008). Two observational studies suggested a better reproductive outcome following hysteroscopic polypectomy in women prior to intrauterine insemination (IUI) (Kalampokas 2012; Shohayeb 2011). The chance for pregnancy is significantly lower in subfertile women with submucous fibroids compared to other causes of subfertility according to one systematic review and meta‐analysis of 11 observational studies (Pritts 2001; Pritts 2009). Three observational studies found a major benefit for removing a uterine septum by hysteroscopic metroplasty in subfertile women with a uterine septum (Mollo 2009; Shokeir 2011; Tomaževič 2010).

Why it is important to do this review

An updated National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guideline on fertility assessment and treatment states that " Women should not be offered hysteroscopy on its own as part of the initial investigation unless clinically indicated because the effectiveness of surgical treatment of uterine abnormalities on improving pregnancy rates has not been established " (NICE 2013). However, there is a trend in reproductive medicine that is developing towards diagnosis and treatment of all major uterine cavity abnormalities prior to fertility treatment. This evolution can be explained by three reasons. First, diagnostic hysteroscopy is generally accepted in everyday clinical practice as the 'gold standard' for identifying uterine abnormalities because it allows direct visualisation of the uterine cavity (Golan 1996). Second, since 2004 several randomised controlled trials (RCTs) have demonstrated the technical feasibility and the high patient satisfaction rate in women undergoing both diagnostic and operative hysteroscopy for various reasons including subfertility (Campo 2005; De Placido 2007; Garbin 2006; Guida 2006; Kabli 2008; Marsh 2004; Sagiv 2006; Shankar 2004; Sharma 2005). Third, in a subfertile population screened systematically by diagnostic hysteroscopy, the incidence of newly detected intrauterine pathology may be as high as 50% (Campo 1999; De Placido 2007).

This review aimed to summarise and critically appraise the current evidence on the effectiveness of operative hysteroscopic interventions in subfertile women with major uterine cavity abnormalities, both in women with unexplained subfertility and women bound to undergo MAR. Since uterine cavity abnormalities may negatively affect the uterine environment, and therefore the likelihood of conceiving (Rogers 1986), it has been recommended that these abnormalities be diagnosed and treated by hysteroscopy to improve the cost‐effectiveness in subfertile women undergoing MAR, where recurrent implantation failure is inevitably associated with a higher economic burden to society.

The study of the association between subfertility and major uterine cavity abnormalities might increase our current understanding of the complex mechanisms of human embryo implantation. This could lead to the development of cost‐effective strategies in reproductive medicine with benefits for both the individual woman experiencing subfertility associated with major uterine cavity abnormalities as well as for society, in a broader perspective.

Objectives

To assess the effects of the hysteroscopic removal of endometrial polyps, submucous fibroids, uterine septum or intrauterine adhesions suspected on ultrasound, hysterosalpingography, diagnostic hysteroscopy or any combination of these methods in women with otherwise unexplained subfertility or prior to intrauterine insemination (IUI), in vitro fertilisation (IVF) or intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI).

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Inclusion criteria

Trials that were either clearly randomised or claimed to be randomised and did not have evidence of inadequate sequence generation such as date of birth or hospital number were eligible for inclusion.

Cluster trials were eligible if the individually randomised women were the unit of analysis.

Cross‐over trials were eligible for completeness but we planned to use only pre‐cross‐over data for meta‐analysis.

Exclusion criteria

Quasi‐randomised trials.

Types of participants

Inclusion criteria

Women of reproductive age with otherwise unexplained subfertility and endometrial polyps, submucous fibroids, septate uterus or intrauterine adhesions detected by US, SIS, GIS, HSG, diagnostic hysteroscopy or any combination of these methods. Besides unexplained subfertility as the main clinical problem, other gynaecological complaints, such as pain or bleeding, might or might not be present.

Women of reproductive age with subfertility, undergoing IUI, IVF or ICSI with endometrial polyps, submucous fibroids, septate uterus or intrauterine adhesions detected by US, SIS, GIS, HSG, diagnostic hysteroscopy or any combination of these methods.

Exclusion criteria

Women of reproductive age with no major uterine cavity abnormalities detected by US, SIS, GIS, HSG, diagnostic hysteroscopy or any combination of these methods.

Women of reproductive age with subfertility and intrauterine cavity abnormalities other than endometrial polyps, submucous fibroids, intrauterine adhesions and septate uterus, for example, subserous or intramural fibroids without cavity deformation on hysteroscopy, acute or chronic endometritis, adenomyosis or other so‐called 'subtle focal' lesions.

Women of reproductive age with endometrial polyps, submucous fibroids, intrauterine adhesions or septate uterus without subfertility.

Women of reproductive age with recurrent pregnancy loss.

Types of interventions

We addressed two types of randomised interventions; within both comparisons we stratified the suspected major uterine cavity abnormalities into endometrial polyps, submucous fibroids, uterine septum and intrauterine adhesions. For the second comparison, there was a stratification into IUI, IVF or ICSI.

Operative hysteroscopy versus control in women with otherwise unexplained subfertility and suspected major uterine cavity abnormalities diagnosed by US, SIS, GIS, HSG, diagnostic hysteroscopy or any combination of these methods.

Operative hysteroscopy versus control in women undergoing IUI, IVF or ICSI with suspected major uterine cavity abnormalities diagnosed by US, SIS, GIS, HSG, diagnostic hysteroscopy or any combination of these methods.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Effectiveness: live birth, defined as a delivery of a live foetus after 20 completed weeks of gestational age that resulted in at least one live baby born. The delivery of a singleton, twin or multiple pregnancy was counted as one live birth.

Adverse events: hysteroscopy complications, defined as any complication due to hysteroscopy.

Secondary outcomes

-

Pregnancy

Ongoing pregnancy, defined as a pregnancy surpassing the first trimester or 12 weeks of pregnancy.

Clinical pregnancy with foetal heartbeat, defined as a pregnancy diagnosed by US or clinical documentation of at least one foetus with a heartbeat (Zegers‐Hochschild 2017).

Clinical pregnancy, defined as a pregnancy diagnosed by US visualisation of one or more gestational sacs or definitive clinical signs of pregnancy (Zegers‐Hochschild 2017).

Adverse events: miscarriage, defined as the spontaneous loss of a clinical pregnancy before 20 completed weeks of gestation, or if gestational age was unknown a foetus with a weight of 400 g or less.

We planned to report the minimally important clinical difference (MICD) for the primary outcome of live birth. An MICD of 5% for the live birth rate was predefined as being relevant for the benefits. The imputation of this value was based on data from a clinical decision analysis on screening hysteroscopy prior to IVF (Kasius 2011b).

Search methods for identification of studies

An updated search was done in liaison with the Cochrane Gynaecology and Fertility (CGF) Group Information Specialist (Marian Showell).

Two review authors (JB and SVW) independently performed a comprehensive search of all published and unpublished reports that described hysteroscopy in subfertile women with endometrial polyps, submucous fibroids, intrauterine adhesions or septate uterus, or undergoing MAR. The search strategy was not limited by language, year of publication or document format. We merged all the retrieved citations from the CGF Specialised Register, the Cochrane Central Register of Studies Online (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, Embase, Web of Science, the BIOSIS PREVIEWS and handsearch‐related articles and removed duplicates using specialised software (EndNote Web 3.5; www.myendnoteweb.com/EndNoteWeb.html; last done: 12 May 2018).

Electronic searches

For the 2018 update of this Cochrane Review, we searched the following bibliographic databases, trial registers and websites:

The Cochrane Gynaecology and Fertility Group's (CGF) Specialised Register, searched on 16 April 2018, PROCITE platform (Appendix 1), CENTRAL Register of Studies Online (CRSO), searched on 16 April 2018, web platform (Appendix 2), MEDLINE OvidSP (searched from 1946 to 16 April 2018) (Appendix 3), and Embase OvidSP (searched from 1980 to 16 April 2018) (Appendix 4).

The search strategy combined both index and free‐text terms.

Our MEDLINE search included the Cochrane highly sensitive search strategy for identifying randomised trials using the PubMed format which appears in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Section 6.4.11.1, box 6.4.a) (Higgins 2011).

Our Embase search included the SIGN trial filter developed by the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (www.sign.ac.uk/methodology/filters.html#random).

Other electronic sources of trials were:

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effectiveness (DARE) and the Health Technology Assessment Database (HTA Database) through the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (searched 12 May 2018) (www.crd.york.ac.uk);

National Guideline Clearinghouse (www.guideline.gov) for evidence‐based guidelines (searched 12 May 2018);

BIOSIS previews through ISI Web of Knowledge (isiwebofknowledge.com) and CINAHL (www.cinahl.com) through EBSCOhost available at the Biomedical Library Gasthuisberg of the Catholic University of Leuven (from 1961 to 1 May 2018) (Appendix 5);

trial registers for ongoing and registered trials: Current Controlled Trials (www.controlled‐trials.com), ClinicalTrials.gov provided by the US National Institutes of Health (clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/home) and the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform search portal (apps.who.int/trialsearch/) (searched 12 May 2018);

citation indexes: Science Citation Index through Web of Science (scientific.thomson.com/products/sci/) – SCI‐EXPANDED (2014 to 12 May 2018) and Conference Proceedings Citation Index – Science (CPCI‐S) (2014 to 12 May 2018) and Scopus available at the Biomedical Library Gasthuisberg of the Catholic University of Leuven) (from inception to 12 May 2018);

conference abstracts and proceedings on the ISI Web of Knowledge (isiwebofknowledge.com) applying 'SCI‐EXPANDED' (2014 to 12 May 2018) and 'CPCI‐S' (2014 to 12 May 2018) (Appendix 6);

LILACS database (searched 12 May 2018) (bases.bireme.br/cgi‐bin/wxislind.exe/iah/online/?IsisScript=iah/iah.xis&base=LILACS&lang=i&form=F) (searched 12 May 2018);

European grey literature through Open Grey database (searched to 12 May 2018) (www.opengrey.eu/subjects/).

Searching other resources

Two review authors (JB and JK for the first published version, JB and SVW for this update) independently handsearched the reference lists of reviews, guidelines, included and excluded studies, and other related articles for additional eligible studies. One review author (JB) contacted the first or corresponding authors of included studies to ascertain if they were aware of any ongoing or unpublished trials.

Two review authors (JB and JK for the first published version, JB and SVW for this update) independently handsearched the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) conference abstracts and proceedings (from 1 January 2014 to 12 May 2018).

One review author (JB) contacted European experts and opinion leaders in the field of hysteroscopic surgery to ascertain if these experts were aware of any relevant published or unpublished studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two or three review authors were responsible for independently selecting the studies (FB and TD for the first published version, JB, SVW and MB for this update). We scanned titles and abstracts from the searches and obtained the full text of those articles that appeared to be eligible for inclusion. We linked multiple reports of the same study together while citing all the references and indicating the primary reference of the identified study. On assessment, we categorised the trials as 'included studies' (Characteristics of included studies table), 'excluded studies' (Characteristics of excluded studies table), 'ongoing studies' (Characteristics of ongoing studies table) or 'studies awaiting classification' (Characteristics of studies awaiting classification table). Any disagreements between both review authors who are content experts were resolved through consensus or by a third review author (BWM for the first published version, SW for this update). We contacted the first or corresponding authors of the primary study reports for further clarification when required. If disagreements between review authors were not resolved, we categorised the studies as 'awaiting classification' and reported the disagreement in the final review. We avoided the exclusion of studies on the basis of the reported outcome measures throughout the selection phase by searching all potential eligible studies that could have measured the primary or secondary outcomes even if these were not reported. We appraised studies in an unblinded fashion, as recommended by the CGF Group.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors, one methodologist (JB) and one topic area specialist (SW), independently assessed the studies that appeared to meet the inclusion criteria by using data extraction forms based on the items listed in the protocol of this Cochrane Review (Appendix 7). We pilot‐tested the data extraction form and process by reviewing 10 randomly chosen study reports. In the pilot phase, two review authors consistently identified one retracted record (Shokeir 2011) on the basis of finding duplicated parts from another study included in the present Cochrane review (Pérez‐Medina 2005). For studies with multiple publications, we used the main trial report as the primary data extraction source and additional details supplemented from secondary papers if applicable. One review author (JB) contacted the first or corresponding authors of the original studies to obtain clarification whenever additional information on trial methodology or original trial data was required. We sent reminder correspondence if a reply was not obtained within two weeks. The two review authors resolved any discrepancies in opinion by discussion; they searched for arbitration by a third review author if consensus was not reached (BWM). One review author (BWM) resolved disagreements which could not be resolved by the review authors after contacting the first or corresponding authors of the primary study reports. If this failed, we reported the disagreement in the review.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (JB and SW) independently assessed the risk of bias of the included studies using the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' assessment tool that considers the following criteria, listed in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Chapter 8, tables 8.5.a and 8.5.b) (Higgins 2011): random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessors, completeness of outcome data, selective outcome reporting and other potential sources of bias. We resolved any disagreements by consensus or by discussion with a third review author (BWM). We presented the conclusions in the 'Risk of bias' table (Characteristics of included studies table), with a full description of all judgements and incorporated them into the interpretation of review findings by means of sensitivity analyses.

We presented a narrative description of the quality of evidence, which is necessary for the interpretation of the results of the review and which is based on the review authors' judgements on the risk of bias of the included trials (Quality of the evidence).

Measures of treatment effect

For the dichotomous data for live birth, pregnancy, miscarriage and hysteroscopy complications, we used the numbers of events in the control and intervention groups of each study to calculate Mantel‐Haenszel odds ratios (OR). We presented 95% confidence intervals (CI) for all outcomes. The OR has mathematically sound properties that are consistent with benefit or harm and which work well in most RCTs on the effectiveness of reproductive surgery given that sample sizes are usually small and trial events are rare. Where data to calculate ORs were not available, we planned to utilise the most detailed numerical data available that might facilitate similar analyses of included studies (e.g. test statistics, P values). We compared the magnitude and direction of effect reported by studies with how they were presented in the review, taking account of legitimate differences. We contacted the corresponding or first authors of all included trials that reported data in a form that was not suitable for meta‐analysis, such as time‐to‐pregnancy (TTP) data. We planned to report the data of those reports that failed to present additional data that could be analysed under 'other data'; we did not included TTP data in any meta‐analyses.

Unit of analysis issues

All primary and secondary outcomes were expressed as per woman randomised. In addition, we reported narrative data on miscarriage expressed as per pregnancy as a secondary analysis. We planned to summarise reported data that did not allow a valid analysis, such as 'per cycle', in an additional table without any attempt at meta‐analysis. We counted multiple live births and multiple pregnancies as one live birth or one pregnancy event. We planned to include only first‐phase data from cross‐over trials, if available.

Dealing with missing data

We aimed to analyse the data on an intention‐to‐treat (ITT) basis. We tried to obtain as much missing data as possible from the original investigators. If this was not possible, we undertook imputation of individual values for the primary outcomes only. We assumed that live births would not have occurred in participants without a reported primary outcome. For all other outcomes, we analysed only the available data. We subjected any imputation of missing data for the primary outcomes to sensitivity analysis. If there were substantial differences in the analysis as compared to an available data analysis, we reported this in the review.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We planned to consider whether the clinical and methodological characteristics of the included studies were sufficiently similar for meta‐analysis to provide a clinically meaningful summary, if more randomised studies were included. We planned to carry out a formal assessment of statistical heterogeneity using the I² statistic combined with the Q‐statistic. Cochrane's Q test, a type of Chi² statistic, is the classical measure to test significant heterogeneity. Cochrane's Q test is calculated as the weighted sum of squared differences between individual study effects and the pooled effect across studies. The Q‐statistic follows Chi² distribution with k‐1 degree of freedom where k is the number of studies. Q greater than k‐1 suggests statistical heterogeneity. A low P value of Cochrane's Q test means significant heterogeneous results among different studies; usually, the P value at 0.10 is used as the cut‐off. The Q‐statistic has low power as a comprehensive test of heterogeneity especially when the number of studies is small. The Q‐statistic informs us about the presence or absence of heterogeneity; it does not report on the extent of such heterogeneity. The I² statistic describes the percentage of variation across studies that is due to significant heterogeneity rather than random chance. It measures the extent of heterogeneity. An I² statistic greater than 50% was taken to indicate substantial heterogeneity (Higgins 2003). We planned to explore possible explanations for heterogeneity by performing sensitivity analyses in Review Manager 5, if there was evidence of substantial statistical heterogeneity (Review Manager 2014).

Assessment of reporting biases

In view of the difficulty in detecting and correcting for publication bias, reporting bias and within‐study reporting bias, we planned to minimise their potential impact by ensuring a comprehensive search for eligible studies and by being alert in identifying duplication of data. We aimed to detect within‐trial selective reporting bias, such as trials failing to report obvious outcomes, or reporting them in insufficient detail to allow inclusion. We planned to seek published protocols and to compare the outcomes between the protocol and the final published study report. Where identified studies failed to report the primary outcomes (e.g. live birth), but did report interim outcomes (e.g. pregnancy), we would have undertaken informal assessment as to whether the interim values were similar to those reported in studies that also reported the primary outcomes. If there were outcomes defined in the protocol or the study report with insufficient data to allow inclusion, the review indicated this lack of data and suggested that further clinical trials need to be conducted to clarify these knowledge gaps. If there were 10 or more studies, we planned to create a funnel plot to explore the possibility of small‐study effects (a tendency for estimates of the intervention effect to be more beneficial in smaller studies). A gap on either side of the graph would have given a visual indication that some trials had not been identified. Given the low number of studies included in the final review, it was not possible to assess reporting bias formally.

Data synthesis

One review author (JB) entered the data and carried out the statistical analysis of the data using Review Manager 5 (Review Manager 2014). We considered the outcomes live birth and pregnancy to be positive and higher numbers as a benefit. We considered the outcomes miscarriage and hysteroscopy complications in the protocol as negative effects and higher numbers harmful. These aspects were taken into consideration when assessing the summary graphs. In the quantitative synthesis an increase in the odds of a particular outcome, either beneficial or harmful, was displayed graphically to the right of the centre‐line and a decrease in the odds of an outcome to the left of the centre‐line.

We planned to combine data from primary studies in a meta‐analysis with Review Manager 5 using the Peto method and a fixed‐effect model (Higgins 2011) for the following comparisons, if more randomised studies could have been included and if significant clinical diversity and statistical heterogeneity could have been confidently ruled out.

Operative hysteroscopy versus control in women with otherwise unexplained subfertility and suspected major uterine cavity abnormalities diagnosed by US, SIS, GIS, HSG, diagnostic hysteroscopy or any combination of these methods.

Operative hysteroscopy versus control in women undergoing MAR with suspected major uterine cavity abnormalities diagnosed by US, SIS, GIS, HSG, diagnostic hysteroscopy or any combination of these methods.

We planned to define analyses that were both comprehensive and mutually exclusive so that all eligible study results were slotted into one of the two predefined strata only. If there were no retrieved trials for some comparisons, the review indicated their absence identifying knowledge gaps which need further research. Since meta‐analysis was not possible due to the limited number of studies included in the review, we presented a narrative overview as prespecified in the protocol).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned to carry out subgroup analyses to determine the separate evidence within the following subgroups, if enough data were available.

Those studies that reported 'live birth' and 'ongoing or clinical pregnancy' to assess any overestimation of effect and reporting bias.

For the two types of randomised comparison, stratified according to the type of uterine abnormality, we planned to carry out subgroup analyses according to the extent or severity of the uterine abnormality. We used the length and diameter in centimetres or calculated volumes of endometrial polyps and submucous fibroids, the lengths and widths of uterine septa and the European Society of Gynaecological Endoscopy (ESGE) classification for intrauterine adhesions as references when applicable (Wamsteker 1998).

We planned to carry out subgroup analyses based on the modifier participant age if enough studies were available.

The interpretation of the statistical analysis for subgroups is not without problems. In the final review, we reported the interpretation of any subgroup analysis performed restrictively, if at all possible, and with utmost caution even if enough data were retrieved.

Sensitivity analysis

We aimed to perform sensitivity analyses for the primary outcomes to determine whether the conclusions are robust to arbitrary decisions made regarding the eligibility and analysis. These analyses included consideration of whether conclusions would have differed if:

eligibility was restricted to studies at low risk of bias in all domains;

alternative imputation strategies were adopted;

a random‐effects rather than a fixed‐effect model was adopted;

the summary effect measure was risk ratio rather than OR.

Overall quality of the body of evidence: 'summary of findings' table

We prepared 'summary of findings' tables using GRADE and Cochrane methods (GRADEpro GDT; Higgins 2011). These tables evaluated the overall quality of the body of evidence for the main review outcomes (primary outcome of effectiveness – live birth – as well as secondary outcome of effectiveness – clinical pregnancy – and the adverse events – hysteroscopy complication and miscarriage) for the two main review comparisons (randomised comparison between operative hysteroscopy versus control for unexplained subfertility associated with suspected major uterine cavity abnormalities and randomised comparison between operative hysteroscopy versus control for suspected major uterine cavity abnormalities prior to MAR). We assessed the quality of the evidence using GRADE criteria: risk of bias, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness and publication bias). Two review authors independently made judgements about evidence quality (high, moderate, low or very low), with disagreements resolved by discussion. Judgements were justified, documented, and incorporated into reporting of results for each outcome.

Results

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; Characteristics of studies awaiting classification; Characteristics of ongoing studies tables.

Results of the search

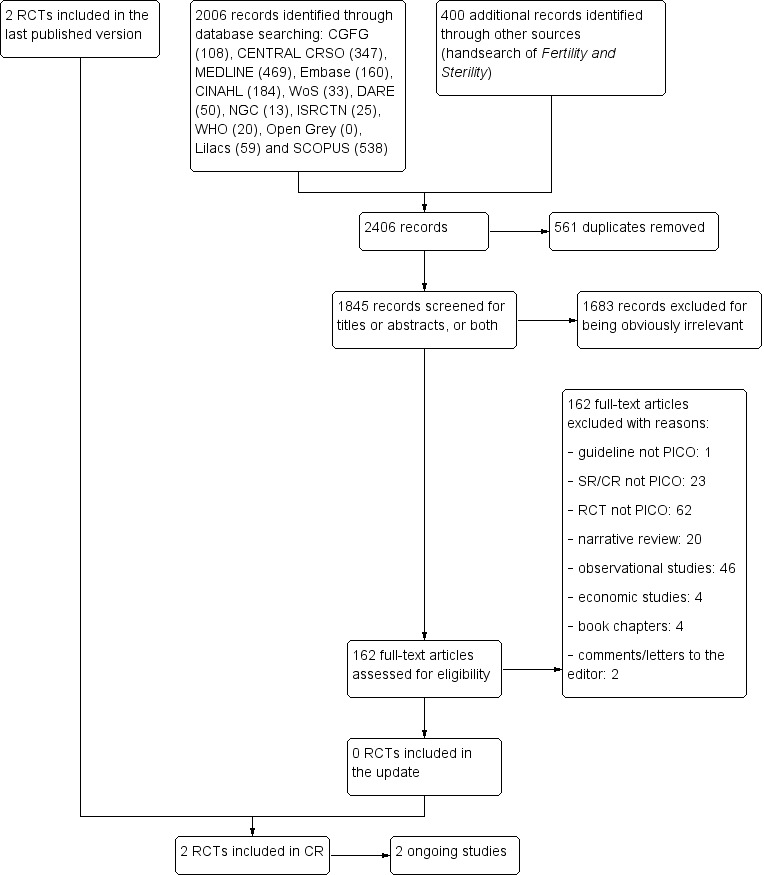

For the present update, there were 108 records from the CGFG Specialised Register, 347 records from CRSO, 469 from MEDLINE, 160 from Embase and 33 from Web of Science. An electronic search in DARE produced 50 records; there were 13 guidelines from National Guideline Clearinghouse, 25 records from the ISRCTN register of controlled trials and 20 records from WHO ICTRP. We identified 538 additional references in Scopus. We identified 184 records in CINAHL and 59 records in LILACS but none in Open Grey. We handsearched 400 abstracts in the congress proceedings of the ASRM for the period 2014 to 2018; we identified no additional abstracts after contacting the experts of the European Society for Gynaecological Endoscopy (ESGE).

After combining 2006 records identified from electronic searches with 400 additional records through handsearching, we screened 2406 records for duplicates by using a specialised software program (EndNote Web). After the removal of 561 duplicate references, we screened the titles or abstracts, or both of 1845 records. We removed 1683 records that were obviously irrelevant. We assessed 162 full‐text articles for eligibility. We did not include additional RCTs in the updated version, so finally we included two RCTs addressing the research questions of this Cochrane Review (Characteristics of included studies table). We excluded 64 studies for various reasons (Characteristics of excluded studies table); 58 studies did not address the PICO research questions of this Cochrane Review, four studies were not randomised, one was a quasi‐randomised trial and one potentially eligible RCT was excluded (Shokeir 2010) because the study report had been retracted at the request of the publisher. Two trials are still ongoing (Characteristics of ongoing studies table).

See: PRISMA flow chart (Figure 1).

1.

Study flow diagram: summary of searches since 2014. CR: Cochrane Review; PICO: Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcome; RCT: randomised controlled trial; SR: systematic review.

Included studies

Study design and setting

The review included two parallel‐design RCTs. Both were single‐centre studies, one conducted in Italy (Casini 2006) and the other in Spain (Pérez‐Medina 2005).

Participants

One study included 94 women with submucous fibroids with or without intramural fibroids and otherwise unexplained subfertility (Casini 2006). There were 52 women in the intervention group and 42 women in the control group. The mean participant age was 31 years (range 29 to 34) in the subgroup of women with submucous fibroids only and 32 years (range 30 to 35) in the subgroup of women with mixed intramural‐submucous fibroids. All women underwent a complete fertility assessment. The presence of uterine fibroids was by TVS. All women who were affected by uterine fibroids excluding all other causes of infertility were asked to participate in the study. Only women aged 35 years or less with a problem of subfertility for at least one year and the presence of one fibroid of diameter 40 mm or less were selected for randomisation. Women older than 35 years or with other causes of infertility at the performed examinations were excluded. Other exclusion criteria were the presence of two or more fibroids of diameter greater than 40 mm; body weight greater than 20% of normal weight; and use of medication containing oestrogens, progestins or androgens in the eight weeks prior to the study.

The second study included 215 women with unexplained, male or female factor infertility for at least 24 months bound to undergo IUI with a sonographic diagnosis of endometrial polyps (Pérez‐Medina 2005). 11 women were lost to follow‐up, six in the intervention group and five in the control group. Data from 101 women in the intervention group and 103 women in the control group were available for analysis.The mean participant age was 31 years (range 27 to 35). All women experienced primary subfertility; they all underwent a complete fertility assessment. Unexplained infertility was diagnosed in women with normal ovulatory cycles, semen analysis, HSG and postcoital testing. Female factor infertility was diagnosed in women with ovulatory dysfunction, cervical factor or endometriosis. Male factor infertility was diagnosed if two semen analyses obtained at least one month apart were subnormal according to the WHO criteria. The sonographic diagnosis of endometrial polyps was established by the demonstration of the vascular stalk of the endometrial polyp by colour Doppler in a hyperechogenic formation with regular contours occupying the uterine cavity, surrounded by a small hypoechogenic halo. Women older than 39 years of age or with anovulation or uncorrected tubal disease or previous unsuccessful use of recombinant follicle‐stimulating hormone (FSH), as well as women with a male partner with azoospermia, were excluded from randomisation.

For details of the inclusion and exclusion criteria, see Characteristics of included studies table.

Interventions

One trial treated the intervention group with hysteroscopic surgery to remove the fibroids; TVS was done three months after the procedure (Casini 2006). Women in the intervention group were suggested to abstain from sexual intercourse for three months and then to start having regular fertility‐oriented intercourse. Women in the control group were asked to immediately start having fertility‐oriented intercourse. Both groups were monitored for up to 12 months after study commencement.

The second trial performed all hysteroscopic interventions in an outpatient clinic setting under local anaesthesia by one gynaecologist (Pérez‐Medina 2005). In the intervention group, the endometrial polyps suspected on Doppler US were extracted by means of rigid 1.5 mm scissors and forceps through the working channel of a 5.5 mm continuous flow hysteroscope. All removed polyps were submitted for histopathological examination. If resection was not possible during the outpatient hysteroscopy, the woman was scheduled for operative hysteroscopy under spinal anaesthesia in the operating theatre of the hospital. All the hysteroscopic interventions were done in the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle. The women of the intervention group were scheduled to receive four cycles of IUI, using subcutaneous injections of FSH 50 IU (international units) daily from the third day of the cycle. The first IUI treatment cycle was started three cycles after the operative hysteroscopy. In the control group, the endometrial polyps suspected on Doppler US were left in place during diagnostic hysteroscopy using a 5.5 mm continuous flow hysteroscope; polyp biopsy was performed to establish a histopathological diagnosis. All women in the control group were scheduled to receive four cycles of IUI, using subcutaneous injections of FSH 50 IU daily from the third day of the cycle. The first IUI treatment cycle was scheduled three cycles after the diagnostic hysteroscopy. Four IUI cycles were attempted before finishing the trial.

Outcomes

Neither of the two included studies reported data on the primary outcomes for this review, live birth and hysteroscopy complication rates.

The first trial measured two secondary outcomes, clinical pregnancy and miscarriage rate (Casini 2006). A clinical pregnancy was defined by the visualisation of an embryo with cardiac activity at six to seven weeks of pregnancy. Miscarriage was defined by the loss of an intrauterine pregnancy between the seventh and 12th weeks of gestation.

The second trial reported only one secondary outcome, the clinical pregnancy rate (Pérez‐Medina 2005). This was defined by a pregnancy diagnosed by US visualisation of one or more gestational sacs.

The authors of one study gave a plausible explanation for the failure to report on the live birth rate (Pérez‐Medina 2005). They failed to give an explanation for the lack of data on the other primary outcome, the hysteroscopy complication rate. The study authors of the other trial could not be contacted successfully for further clarification on the absence of reporting the primary outcomes (Casini 2006).

Excluded studies

We excluded 64 studies on hysteroscopic interventions for various reasons.

One randomised trial (Shokeir 2010) was excluded since the main published report was retracted at the request of the editor of the publishing journal as it duplicated parts of a paper on a different topic that had already appeared in another journal published years before (Pérez‐Medina 2005).

One trial was a quasi‐randomised trial (Pabuccu 2008).

Four trials were non‐randomised studies (De Angelis 2010; Gao 2013; Mohammed 2014; Trninić‐Pjević 2011).

-

Fifty‐eight randomised trials did not address the prespecified PICO (Participants, Interventions, Comparisons and Outcomes) research questions of this Cochrane Review.

Fourteen trials studied the effectiveness of hysteroscopy in subfertile women bound to undergo IVF or ICSI treatment with unsuspected or no uterine cavity abnormalities (Abiri 2014; Aghahosseini 2012; Aleyassin 2017; Basma 2013; Demirol 2004; Di Florio 2013; El‐Nashar 2011; Elsetohy 2015; El‐Toukhy 2009; Fatemi 2007; Rama Raju 2006; Shawki 2012; Smit 2016; Sohrabvand 2012).

One trial assessed the effectiveness of hysteroscopy prior to IUI in women with no previously detected uterine anomalies (Moramezi 2012).

Three trials assessed the effectiveness of endometrial injury (El‐Khayat 2015; Hare 2013; Weiss 2005).

Twelve trials had a study population that included women who were not of reproductive age experiencing gynaecological problems other than subfertility (Clark 2015; Hamerlynck 2015; Javidan 2017; Kamel 2014; Lara‐Dominguez 2016; Lieng 2010a; Muzii 2007; Muzii 2017; Nappi 2013; Rubino 2015; Smith 2014; van Dongen 2008).

Two trials had a study population that included only women with repeated miscarriage (Vercellini 1993) or recurrent implantation failure (Cao 2018).

Eighteen trials studied the effectiveness of adjunctive therapies (hyaluronic acid gel, amnion graft, balloon catheter, cyclical hormone replacement therapy alone or intrauterine device alone or both cotreatments combined, autologous platelet rich plasma) for the prevention of intrauterine adhesions following hysteroscopic adhesiolysis (Abu Rafea 2013; Acunzo 2003; Aghajanova 2018; Amer 2010; De Iaco 2003; Di Spiezio Sardo 2011; Fuchs 2014; Gan 2017; Guida 2004; Guo 2017; Hanstede 2016; Lin 2014; Liu 2016; Paz 2014; Revel 2011; Roy 2014; Tonguc 2010; Xiao 2015).

Six trials compared different surgical techniques for treating uterine septum in a mixed study population of women with subfertility or recurrent pregnancy loss (Colacurci 2007; Darwish 2009; Parsanezhad 2006; Roy 2015; Roy 2017; Youssef 2013).

One trials assessed the interobserver agreement of gynaecologists performing hysteroscopy for a septate uterus who received instructions on the assessment of the septum prior to the procedure versus gynaecologists who did not (Smit 2015).

One trial was an RCT investigating the effects of mindfulness‐based stress reduction on anxiety, depression and quality of life in women with intrauterine adhesions (Chen 2017).

See: Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Studies awaiting classification

We found no studies awaiting classification.

Ongoing studies

We retrieved two ongoing studies (SEPTUM trial; TRUST trial).

The TRUST trial is a multicentre RCT. The starting date was 1 October 2008. The sample size of this study is 68 women; on 4 May 2018 the 63rd participant was included.

The SEPTUM trial was designed as a pilot multicentre RCT to assess the feasibility for a larger adequately powered trial. The trial is closed to further recruitment due to feasibility issues with recruitment. Six participants were included and will be followed up for 24 months post intervention (personal correspondence with Dr Matthew Prior).

See: Characteristics of ongoing studies table.

Risk of bias in included studies

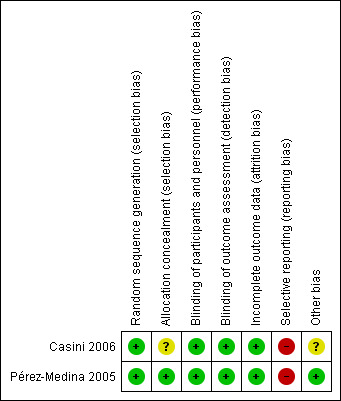

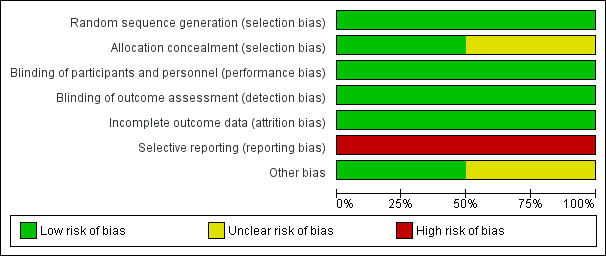

See the 'Risk of bias' summary for the review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item in the included study (Figure 2).

2.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

See the 'Risk of bias' graph for the review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across the two included studies (Figure 3).

3.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Allocation

We judged both studies at low risk of selection bias related to random sequence generation, as both used computerised random numbers tables (Casini 2006; Pérez‐Medina 2005).

We judged one study at low risk for selection bias related to allocation concealment, as they used sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes to conceal the random allocation of women to one of the comparison groups (Pérez‐Medina 2005). We judged the second trial at unclear risk for selection bias related to allocation concealment since the method used was not reported and no further clarification by the authors could be obtained (Casini 2006).

Blinding

We judged both studies at low risk of performance and detection bias since both surgical studies had unequivocal outcomes that are most likely not affected by unclear blinding of participants, personnel and outcome assessors (Casini 2006; Pérez‐Medina 2005). The methods were not reported and no further clarification could be obtained.

Incomplete outcome data

We judged both studies at low risk of attrition bias. One study reported outcome data of all randomised women (Casini 2006). The second study analysed the majority of women randomised (95%) (Pérez‐Medina 2005). The missing outcome data in the remaining 5% were balanced in numbers with similar reasons for missing data between the two comparison groups.

Selective reporting

We judged both studies at high risk of reporting bias (Casini 2006; Pérez‐Medina 2005). Both studies failed to include data for the primary outcome live birth, which could reasonably have been reported in studies conducted over a seven‐year (Casini 2006) and a four‐year (Pérez‐Medina 2005) period. Although a plausible explanation was given by the contact author of one study (Pérez‐Medina 2005), we judged that it could have been possible to obtain data on the live birth rates if the study authors had contacted the referring gynaecologists (see Characteristics of included studies table). Moreover, one trial reported no data on adverse outcomes such as miscarriage or hysteroscopy complications (Pérez‐Medina 2005), whereas the second study reported miscarriage rates only for the adverse events (Casini 2006).

Other potential sources of bias

We judged one study to be at unclear risk of other potential sources of bias (Casini 2006). The study did not report the mean ages and duration of infertility in the intervention and control group of women with submucous fibroids; we were unable to obtain these data from the study authors given that we were unsuccessful in contacting them. It is unclear whether this might have caused imbalance in the baseline characteristics between the comparison groups in this randomised trial (Casini 2006). Moreover, it was unclear whether hysteroscopy had been performed in all participants to confirm the position of the ultrasonically detected fibroids.

We judged the second study at low risk of other potential sources of bias since there was no evidence of baseline imbalance in the participant characteristics between the two comparison groups (Pérez‐Medina 2005).

Publication bias could not be formally assessed due to the very limited number of studies included in this Cochrane Review.

Effects of interventions

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Operative hysteroscopy versus control in women with otherwise unexplained subfertility and suspected major uterine cavity abnormalities.

| Operative hysteroscopy versus control in women with otherwise unexplained subfertility and suspected major uterine cavity abnormalities | ||||||

|

Patient or population: women with submucous fibroids and otherwise unexplained subfertility Settings: infertility centre in Rome, Italy Intervention: hysteroscopic removal of 1 submucous fibroid ≤ 40 mm Comparison: no surgery | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| No surgery | Myomectomy | |||||

| Live birth | No data reported. | |||||

| Adverse events: hysteroscopy complications | No data reported. | |||||

|

Clinical pregnancya Ultrasound 12 months |

214 per 1000 | 400 per 1000 (209 to 627) |

OR 2.44 (0.97 to 6.17) |

94 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowb,c | — |

|

Adverse events: miscarriaged Ultrasound 12 months |

119 per 1000 | 172 per 1000 (63 to 477) |

OR 1.54 (0.47 to 5.00) |

94 women (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowb,c | — |

| *The basis for the assumed risk is the control group risk of the single included study (Casini 2006). The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aClinical pregnancy defined by the visualisation of an embryo with cardiac activity at six to seven weeks' gestational age.

bDowngraded by two levels for very serious risk of bias (unclear allocation concealment, high risk of selective outcome reporting and unclear whether there is other bias caused by imbalance in the baseline characteristics).

cDowngraded by one level for serious imprecision (wide confidence interval of the effect size estimate).

dMiscarriage was defined by the clinical loss of an intrauterine pregnancy between the 7th and 12th weeks of gestation.

Summary of findings 2. Operative hysteroscopy versus control in women undergoing medically assisted reproduction with suspected major uterine cavity abnormalities.

| Operative hysteroscopy versus control in women undergoing medically assisted reproduction with suspected major uterine cavity abnormalities | ||||||

|

Patient or population: subfertile women with endometrial polyps diagnosed by ultrasonography prior to treatment with gonadotropin and intrauterine insemination Settings: infertility unit of a university tertiary hospital in Madrid, Spain Intervention: hysteroscopic polypectomy using a 5.5 mm continuous flow office hysteroscope with a 1.5 mm scissors and forceps Comparison: diagnostic hysteroscopy using a 5.5 mm continuous flow office hysteroscope and polyp biopsy | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Polypectomy | |||||

| Live birth | No data reported. | |||||

| Adverse events: hysteroscopy complications | No data reported. | |||||

|

Clinical pregnancya Ultrasound 4 intrauterine insemination cycles |

282 per 1000 | 634 per 1000 (451 to 894) |

OR 4.41 (2.45 to 7.96) |

204 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowb,c | — |

| Adverse events: miscarriage | No data were reported for this secondary outcome. | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk is the control group risk of the single included study (Pérez‐Medina 2005). The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aClinical pregnancy was defined by the presence of at least one gestational sac on ultrasound.

bDowngraded by one level for serious risk of bias (high risk for selective outcome reporting).

cDowngraded by one level for serious imprecision (wide confidence interval of the effect size estimate).

1. Operative hysteroscopy versus control in women with otherwise unexplained subfertility and suspected major uterine cavity abnormalities

See: Table 1.

Endometrial polyps

The search identified no studies on endometrial polyps.

Submucous fibroids

One study compared hysteroscopic myomectomy versus no surgery in women with unexplained subfertility and submucous fibroids only or combined with intramural fibroids (Casini 2006).

Primary outcomes

Live birth

There were no data for live births.

Adverse events: hysteroscopy complications

There were no data for hysteroscopy complications.

Secondary outcomes

Clinical pregnancy

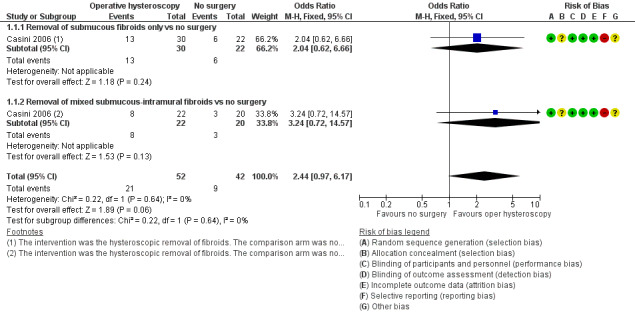

In women with otherwise unexplained subfertility and submucous fibroids, we were uncertain whether hysteroscopic myomectomy improved the clinical pregnancy rate compared to expectant management (OR 2.44, 95% CI 0.97 to 6.17; P = 0.06, 94 women; Analysis 1.1; Figure 4).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Operative hysteroscopy versus control in women with otherwise unexplained subfertility and suspected major uterine cavity abnormalities, Outcome 1 Clinical pregnancy.

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Hysteroscopic myomectomy vs no surgery in women with unexplained subfertility and submucous fibroids. Outcome: 1.1 Clinical pregnancy per woman randomised.

Adverse events: miscarriage

There was insufficient evidence to determine whether there was a difference between the removal of one submucous fibroid of diameter 40 mm or less in women with otherwise unexplained subfertility for at least one year versus expectant management for the outcome of miscarriage per woman randomised (OR 1.54, 95% CI 0.47 to 5.00; P = 0.47, 94 women; Analysis 1.2; Figure 5). As a secondary analysis, we reported the miscarriage rate per clinical pregnancy. There was insufficient evidence to determine whether there was a difference between the groups (OR 0.58, 95% CI 0.12 to 2.85; P = 0.50, 30 clinical pregnancies in 94 women).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Operative hysteroscopy versus control in women with otherwise unexplained subfertility and suspected major uterine cavity abnormalities, Outcome 2 Adverse events: miscarriage.

5.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Hysteroscopic myomectomy vs no surgery in women with unexplained subfertility and submucous fibroids. Outcome: 1.2 Miscarriage per clinical pregnancy.

Subgroup analyses

We performed no subgroup analyses across studies to assess any overestimation of treatment effect or reporting bias, due to the limited number of studies.

One prespecified subgroup analysis within the trial was done for the two secondary outcomes of clinical pregnancy and miscarriage according to whether submucous fibroids only or mixed submucous‐intramural fibroids were considered. There was insufficient evidence to determine whether there was a difference for the secondary outcome clinical pregnancy between the 'submucous only' subgroup (OR 2.04, 95% CI 0.62 to 6.66; P = 0.24, 1 RCT, 52 women) and the 'mixed submucous‐intramural' subgroup (OR 3.24, 95% CI 0.72 to 14.57; P = 0.13, 1 RCT, 42 women); the tests for subgroup differences demonstrated no statistical heterogeneity beyond chance (Chi² = 0.22, degrees of freedom (df) = 1; P = 0.64, I² = 0%). There was insufficient evidence to determine whether there was a difference for the secondary outcome miscarriage between the 'submucous only' subgroup (OR 0.63, 95% CI 0.09 to 4.40; P = 0.64, 1 RCT, 19 clinical pregnancies in 52 women) and the 'mixed submucous‐intramural' subgroup (OR 0.50, 95% CI 0.03 to 7.99; P = 0.62, 1 RCT, 11 clinical pregnancies in 42 women); the tests for subgroup differences demonstrated no statistical heterogeneity beyond chance (Chi² = 0.02, df = 1, P = 0.90, I² = 0%).

Uterine septum

There were no data for uterine septum.

Intrauterine adhesions

There were no data for intrauterine adhesions.

2. Operative hysteroscopy versus control in women undergoing medically assisted reproduction with suspected major uterine cavity abnormalities

See: Table 2.

Endometrial polyps prior to intrauterine insemination

One study compared hysteroscopic removal of polyps versus diagnostic hysteroscopy and polyp biopsy in women with endometrial polyps undergoing gonadotropin treatment and IUI (Pérez‐Medina 2005).

Primary outcomes

Live birth

There were no data for live births.

Adverse events: hysteroscopy complications

There were no data for hysteroscopy complications.

Secondary outcomes

Clinical pregnancy

The hysteroscopic removal of polyps prior to IUI may have improved the clinical pregnancy rate compared to diagnostic hysteroscopy only: if 28% of women achieved a clinical pregnancy without polyp removal, the evidence suggested that 63% of women (95% CI 45% to 89%) would have achieved a clinical pregnancy after the hysteroscopic removal of the endometrial polyps (OR 4.41, 95% CI 2.45 to 7.96; P < 0.00001, 204 women; Analysis 2.1; Figure 6). The number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome was 3 (95% CI 2 to 4).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Operative hysteroscopy versus control in women undergoing medically assisted reproduction with suspected major uterine cavity abnormalities, Outcome 1 Clinical pregnancy.

6.

Forest plot of comparison: 2 Hysteroscopic removal of polyps vs diagnostic hysteroscopy and biopsy only prior to intrauterine insemination. Outcome: 2.1 Clinical pregnancy per woman randomised.

Adverse events: miscarriage

There were no data for miscarriage.

Subgroup analyses

We performed no subgroup analyses across studies to assess any overestimation of treatment effect or reporting bias given the limited number of studies.

We performed the following two subgroup analyses within the included study.

A first prespecified subgroup analysis studied the effect of polyp size on the secondary outcome of clinical pregnancy. On histopathological examination, the mean size of the polyps removed was 16 mm (range 3 mm to 24 mm). The primary study examined the effect of polyp size on the clinical pregnancy rate in the intervention group. They analysed the data based on the size of the removed polyps, subdivided into four groups based in their quartiles (less than 5 mm, 5 mm to 10 mm, 11 mm to 20 mm and greater than 20 mm); there was insufficient evidence to determine whether there was a difference between these four subgroups given the limited number of data (P = 0.32) (Table 3). There was no evidence of an effect of polyp size on the outcome of clinical pregnancy, but these results should be interpreted carefully given the limited numbers in only one included study. There were no data on the estimated size of the polyps in the control group.

1. Effect of polyp size on clinical pregnancy rates in the intervention group.

| Polyp size | Clinical pregnancya | Clinical pregnancy rate (95% CI)b |

| < 5 mm | 19/25 | 76% (72% to 80%) |

| 5–10 mm | 18/32 | 56% (53% to 59%) |

| 11–20 mm | 16/26 | 61% (58% to 65%) |

| > 20 mm | 11/18 | 61% (58% to 64%) |

CI: confidence interval.

aClinical pregnancy is defined by a pregnancy diagnosed by ultrasound visualisation of at least one gestational sac per woman randomised.

bNo significant difference was found for the clinical pregnancy rates between the 4 subgroups (P = 0.32).

The second subgroup analysis studied the effect of the timing of the IUI treatment after hysteroscopy on the secondary outcome clinical pregnancy. About 29% of women in the polypectomy group, compared to 3% in the diagnostic hysteroscopy group, became pregnant in the three‐month period after the hysteroscopy before the treatment with gonadotropin and IUI was started; this was calculated from the Kaplan‐Meier survival analysis in the published report of the primary study (Pérez‐Medina 2005). Hysteroscopic polypectomy may have improved the clinical pregnancy rate compared to diagnostic hysteroscopy and polyp biopsy in women waiting to be treated with gonadotropin and IUI (OR 13, 95% CI 3.9 to 46; P < 0.0001, 1 study, 204 women; available‐data analysis). The number needed to treat to for an additional beneficial outcome after hysteroscopic polypectomy while waiting for further treatment with gonadotropin and IUI was 4 (95% CI 3 to 6). In women who started gonadotropin and IUI treatment the pregnancy rates per woman were 49% in the intervention group and 26% in the control group, calculated from data in the published report of the primary study (Pérez‐Medina 2005). Hysteroscopic polypectomy may have improved the clinical pregnancy rate in women who started from three months after the surgical procedure with gonadotropin and IUI treatment (OR 2.7, 95% CI 1.4 to 5.1; P = 0.003, 1 RCT, 172 women; available‐data analysis). The number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome when treated with gonadotropin and IUI after a prior hysteroscopic polypectomy was 4 (95% CI 3 to 12). This was a post hoc subgroup analysis. Quoting from the primary study published report "A second important conclusion in our study is that pregnancies after polypectomy are frequently obtained spontaneously while waiting for the treatment, suggesting a strong cause–effect of the polyp in the implantation process. This led us to defer the first IUI to three menstrual cycles after the polypectomy is performed. Longer series are needed to verify these results". Data from this subgroup analysis should be treated with caution as subgroup analysis by itself is observational in nature, and statistical interpretation of its results is not without problems.

Sensitivity analyses

A sensitivity analysis comparing an ITT analysis assuming that clinical pregnancies would not have occurred in participants with missing data, rather than an available‐data analysis, did not affect the statistical significance of the main analysis for the secondary outcome clinical pregnancy (OR 4.0, 95% CI 2.3 to 7.2; P < 0.00001; 1 RCT, 215 women randomised). No other imputation strategies for dealing with the missing data were assumed given the limited number of studies.

Endometrial polyps prior to in vitro fertilisation or intracytoplasmic sperm injection

We found no studies on endometrial polyps prior to IVF or ICSI.

Submucous fibroids prior to intrauterine insemination, in vitro fertilisation or intracytoplasmic sperm injection

We found no studies on submucous fibroids prior to IUI, IVF or ICSI.

Uterine septum prior to intrauterine insemination, in vitro fertilisation or intracytoplasmic sperm injection

We found no studies on uterine septum prior to IUI, IVF or ICSI.

Intrauterine adhesions prior to intrauterine insemination, in vitro fertilisation or intracytoplasmic sperm injection

We found no studies on intrauterine adhesions prior to IUI, IVF or ICSI.

Other analyses

We planned to do sensitivity analyses for Analysis 1.1; Analysis 1.2; and Analysis 2.1 to consider whether conclusions would have differed if eligibility had been restricted to studies at low risk of bias in all domains. We retrieved only one study for each random comparison. Moreover for both studies there was at least one item at high risk of bias (Figure 2). Hence no sensitivity analyses were performed in the present updated Cochrane Review.

Discussion

Summary of main results

This systematic review aimed to investigate whether the hysteroscopic treatment of suspected major uterine cavity abnormalities made a difference to the main outcomes of live birth or pregnancy and the adverse events (hysteroscopy complications and miscarriage) in subfertile women with otherwise unexplained subfertility or before IUI, IVF or ICSI. We searched for studies on two randomised comparisons to study the effectiveness of operative hysteroscopy in the treatment of subfertility associated with major uterine cavity abnormalities.

The first randomised comparison was operative hysteroscopy versus control in women with otherwise unexplained subfertility and suspected major uterine cavity abnormalities – stratified into endometrial polyps, submucous fibroids, intrauterine adhesions or septate uterus – diagnosed by US, SIS/GIS, HSG, diagnostic hysteroscopy or any combination of these methods (Table 1). We retrieved and critically appraised only one trial in this category comparing the hysteroscopic removal of one submucous fibroid with a diameter of 40 mm or less in women aged 35 years or less with otherwise unexplained subfertility versus expectant management (no surgery followed by fertility‐oriented intercourse) (Casini 2006). There was insufficient evidence to determine whether there was a difference between groups. This may have been due to a type II error: we calculated that a sample size of 91 participants was needed to detect a difference of 19% for the outcome of clinical pregnancy between groups with a statistical power of 80% at a confidence level of 95% (α = 0.05 and β = 0.20). In other words, a study population of at least 182 participants is needed to detect any statistically significant difference if present; compared to only 94 women in the study (Casini 2006). There was insufficient evidence to determine whether there was a difference between groups for the miscarriage rate. We found no data on live birth or hysteroscopy complication rates. We found no studies in women with endometrial polyps, intrauterine adhesions or septate uterus for this randomised comparison.