Abstract

The stimulatory pathways controlling HCO3− secretion by the pancreatic ductal epithelium are well described. However, only a few data are available concerning inhibitory mechanisms, which may play an important role in the physiological control of the pancreas. The aim of this study was to investigate the cellular mechanism by which substance P (SP) inhibits pancreatic ductal HCO3− secretion. Small intra/interlobular ducts were isolated from the pancreas of guinea pigs. During overnight culture the ducts seal to form a closed sac. Transmembrane HCO3− fluxes were calculated from changes in intracellular pH (measured using the pH sensitive dye BCECF), and the buffering capacity of the cells. We found that secretin can stimulate HCO3− secretion in guinea pig pancreatic ducts about 5-fold and that this effect could be totally blocked by SP. The inhibitory effect of SP was relieved by spantide, a SP receptor antagonist. SP had no effect on the activity of basolateral Na+/HCO3− cotransporters and Na+/H+ exchangers. However, the peptide did inhibit a Cl− dependent HCO3− efflux (secretory) mechanism, most probably the Cl−/HCO3− exchanger on the apical membrane of the duct cell.

Keywords: Pancreas, Cl−/HCO3− exchanger, tachykinin

INTRODUCTION

Pancreatic duct cells secrete the HCO3− ions found in pancreatic juice (2). This alkaline secretion washes digestive enzymes (secreted by acinar cells) along the ductal tree and into the duodenum, and also contributes to the neutralization of acid chyme entering the duodenum from the stomach (2). In recent years, following the development of isolated duct preparations, our understanding of the cellular mechanisms of ductal HCO3− secretion has advanced rapidly. HCO3− is accumulated across the basolateral membrane of the duct cell by Na (HCO3)n co-transporters, Na+/H+ exchangers and proton pumps (2, 9). Also on the basolateral membrane are Cl−/HCO3− exchangers (8, 31). The function of these basolateral anion exchangers is unclear as, given the prevailing transmembrane Cl− concentration gradient, they would be predicted to transport HCO3− from the cell into the blood, i.e. to oppose HCO3− secretion. Computer modelling studies have shown that the ratio of apical to basolateral anion exchange activities must be about 9:1 in stimulated ducts (25). Recently, it has been shown that stimulation of mouse pancreatic ducts has no effect on basolateral Cl−/HCO3− exchangers, but markedly enhances apical Cl−/HCO3− exchange activity (16).

CFTR chloride channels, Ca2+-activated chloride channels and anion exchangers are the only transport elements that have been identified on the apical membrane of duct cells in small interlobular and intralobular ducts, which are probably the major sites of HCO3− secretion (2). Originally, it was considered that HCO3− secretion occurred on the exchanger with the CFTR and Ca2+-activated chloride channels acting to recycle Cl− across the apical membrane (2). Computer modelling studies suggest that such a mechanism could increase the luminal HCO3− concentration to about 70 mM (25). To raise the luminal HCO3− concentration to 150 mM, the concentration secreted by the pancreas of guinea pigs, humans and some other species (2), additional HCO3− is secreted directly via the channels (10). The regulatory pathways that stimulate pancreatic ductal HCO3− secretion are well-described (2), however, much less is known about inhibitory pathways. Substance P (3) and 5-OH-tryptamine (26) strongly inhibit fluid and HCO3− secretion from isolated pancreatic ducts, suggesting that agents have a direct inhibitory effect on the ductal epithelium. Such inhibitory pathways may be physiologically important in terms of limiting the hydrostatic pressure within the lumen of the duct (thus preventing leakage of enzymes into the parenchyma of the gland), and in terms of switching off pancreatic secretion after a meal (3, 26).

The undecapeptide substance P (SP) has been shown to inhibit secretin-stimulated secretion from the pancreas of the dog (11, 15) and rat (12). SP like immunoreactivity has been identified in the pancreas of the dog, rat and mouse (21), although it has not been localised around the ducts (24). In isolated rat pancreatic ducts, 10−10 M and 10−8 M SP inhibited basal fluid secretion by 54% and 92% respectively, and the same doses of SP completely blocked the fluid secretory responses to secretin and bombesin (3). These inhibitory effects of SP were blocked by spantide, which is a SP receptor antagonist (3). SP also inhibited fluid secretion stimulated by dibutyryl cyclic AMP and forskolin (3), which places the inhibitory effect of SP at a point in the secretory mechanism downstream from the generation of cyclic AMP. The purpose of this study was to identify the duct cell transporter(s) that are modulated by SP.

METHODS

Isolation of pancreatic ducts

Small intra/interlobular ducts were isolated from the pancreas of guinea pigs weighing 150–250 g. The guinea pig was killed by cervical dislocation, the pancreas removed and intra/interlobular ducts isolated by enzymatic digestion, microdissection and then cultured over night as previously described (1). During overnight culture the ducts seal to form a closed sac that swells due to accumulation of secretions in the duct lumen (1).

Measurement of intracellular pH

Cultured ducts were attached, using Cell-Tak, to a coverslip (24mm2) forming the base of a perfusion chamber mounted on a Nikon Diaphot microscope (Nikon UK Ltd, Kingston upon Thames, UK). The ducts were bathed in the standard HEPES solution at 37°C and loaded with the pH-sensitive fluorescent dye BCECF by exposure to 2μM-BCECF-AM for 20–30 min. After loading, the ducts were continuously perfused with solutions at a rate of 4–5 ml/min. Intracellular pH (pHi) was measured using a Life Sciences microspectrofluorimeter system (Life Sciences Resources Ltd, Cambridge, UK). A small area of 5–10 cells was excited with light at wavelengths of 490 nm and 440 nm, and the 490/440 fluorescence emission measured at 535nm. Four pHi measurements were obtained per second. In situ calibration of the fluorescence signal was performed using the high K+-nigericin technique (28). During the calibration, ducts were bathed in a high K+ HEPES solution and extracellular pH stepped between 5.95 and 8.46.

Determination of buffering capacity

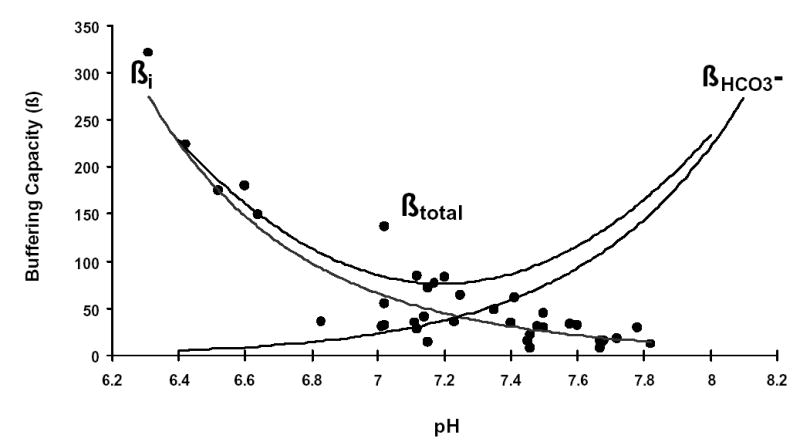

The intrinsic buffering capacity (ßi) of duct cells was estimated according to the NH4+ pre-pulse technique (29). ßi refers to the ability of intrinsic cellular components (excluding HCO3−/CO2) to buffer changes of pHi. Briefly, pancreatic duct cells were exposed to various concentrations of NH4Cl while Na+ and HCO3− were omitted from the solution in order to block the Na+ dependent pH regulatory mechanisms. ßi was estimated by the Henderson-Hasselbach equation. The total buffering capacity (ßtotal) was calculated from: , where is the buffering capacity of the HCO3−/CO2 system (Fig. 1). 0

Fig. 1. Buffering capacity of pancreatic duct cells.

Pancreatic duct cells were exposed to various concentrations of NH4Cl while Na+ and HCO3− were omitted from the solution in order to block Na+ dependent pH regulatory mechanisms. The intrinsic buffering capacity (ßi) was estimated by the Henderson-Hasselbach equation (closed circles, n=40). Regression analysis was performed using the curve fitting protocol in Excel. The total buffering capacity (ßtotal) was calculated from: , where is the buffering capacity of the HCO3−/CO2 system.

Measurement of HCO3− transport

1) HCO3− efflux

a) Inhibitor stop method

In this series of experiments the HCO3− accumulation mechanisms on the basolateral membrane of the duct cell, the Na+/H+ exchanger and the Na+/HCO3− cotransporter (2), were blocked by brief exposure (5 min) of the ducts to amiloride (0.2 mM) and DIDS (0.1 mM) (27). This procedure causes pHi to acidify (27). The rate of pHi acidification has been shown to reflect the rate of HCO3− efflux occurs across the apical membrane and the buffering capacity of the cell (27).

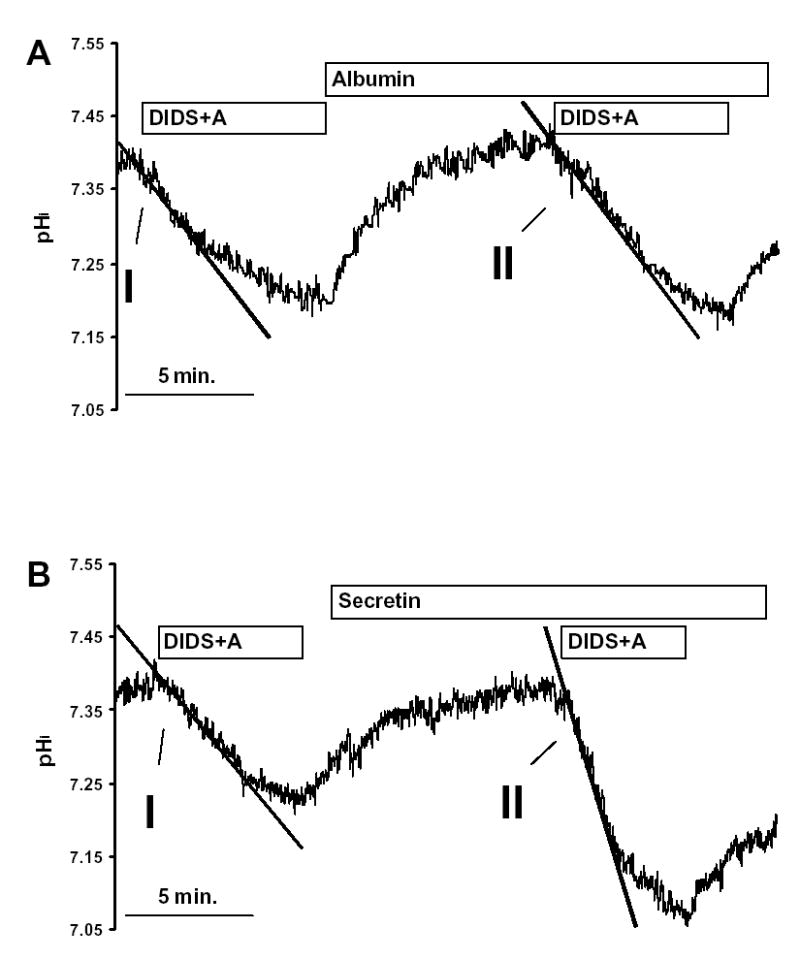

The initial rate of intracellular acidification (dpH/dt), over the first 60 sec of exposure to amiloride and DIDS, was calculated by linear regression analysis using 240 data points (four pHi measurements per second) (see Fig. 2). Each duct was exposed to amiloride and DIDS twice, the first exposure being the control and the second the test. 10nM secretin and/or 20 nM SP and/or 20 nM spantide were given for 10 minutes between the two measurements. In the control group, 1% albumin was administered before the second measurement as it was used as the vehicle for secretin and SP.

Fig. 2. Inhibitor stop method for determining bicarbonate secretion.

Pancreatic duct cells were exposed to 0.2 mmol/l amiloride (A) and 0.1 mmol/l DIDS twice in the same duct. The initial rate of intracellular acidification (over 60sec) was measured, the initial measurement being the control and the second the test. (A) 1% albumin (vehicle for secretin and SP), (B) 10 nM secretin, (C) 20 nM SP and (D) 10 nM secretin and 20 nM SP were all given for 10 minutes between the two measurements. All the experiments were performed at 37 °C using a standard KREBS solution, containing 25mM HCO3−. Each experiment was performed on a different duct.

(b) Recovery from an alkaline load

Ducts were alkali loaded by exposure to 3 min. pulses of 20 mM NH4Cl. The initial rate of recovery from alkalosis (dpH/dt) over the first 30 sec (120 pHi measurements) in the continued presence of NH4Cl, was calculated as described above.

2) HCO3− influx

(a) Recovery from an acid load

Ducts were acid loaded as described above and then the NH4Cl removed, which caused a marked acidification of pHi. The initial rate of pHi recovery (dpH/dt) was measured over the first 30 sec. (120 data points) after removal of NH4Cl.

The rates of pHi change measured in these experiments were converted to transmembrane base flux J(B−) using the equation: J(B−) = dpH/dt x ßtotal. The ßtotal value used in the calculation of base fluxes was obtained from Fig. 1 using the pHi value at the start of the 30 sec. or 60 sec. period over which dpH/dt was measured. We denote base influx as J(B−) and base efflux as −J(B−).

Solutions and chemicals

The compositions of the solutions used are shown in Table 1. HEPES-buffered solutions were gassed with 100% O2 at 37 °C and pH was set to 7.4 with HCl. HCO3− buffered solutions were gassed with 95% O2 and 5% CO2 at 37 °C.

Table 1.

Different type of solutions. The concentrations of ions are given in mM

| Standard HEPES | Standard HCO3− | high-K+ HEPES | NH4+ in HEPES | NH4+ in HCO3− | Na+ free HEPES | NH4+ in Na+ free HEPES | Cl− free HEPES | Cl− free HCO3− | NH4+ in Cl− free HEPES | NH4+ in Cl− free HCO3− | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NaCl | 130 | 115 | 5 | 110 | 95 | ||||||

| KCl | 5 | 5 | 130 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | ||||

| MgCl2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| CaCl2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| NaHEPES | 10 | 10 | 10 | ||||||||

| Glucose | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| NaHCO3 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | |||||||

| NH4Cl | 20 | 20 | 20 | ||||||||

| NMDG.Cl | 140 | 120 | |||||||||

| HEPES | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | |||||||

| Na gluconate | 140 | 115 | 120 | 95 | |||||||

| K sulfate | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | |||||||

| Mg gluconate | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Ca gluconate | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | |||||||

| NH4 sulfate | 20 | 20 |

All laboratory chemicals, peptides, transport blockers and ionophores were obtained from Sigma (Poole, Dorset, UK). Chromatographically pure collagenase was obtained from Worthington (Lakewood, NJ, USA), culture media from ICN (Aurora, Ohio, USA). Nigericin was dissolved in absolute ethanol, DIDS and amiloride in DMSO, secretin, and spantide and SP in 1% albumin. CellTak was obtained from Becton Dickinson Labware (Bedford, MA, USA). BCECF-AM was obtained from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR, USA) and made up as a 2 mM stock solution using DMSO.

Statistical analysis

Results were expressed as means ± S.E.M (n = number of observations). Statistical analyses were performed using either Student's t-test (when the data consisted of two groups) or ANOVA (when three or more data groups were compared ). P values < 0.05 were accepted as significant.

RESULTS

1. Inhibitory effect of substance P on HCO3− secretion

The resting pHi of duct cells bathed in the standard HCO3− containing buffer was 7.36 ± 0.01 (n = 8). Exposing ducts to 0.1 mM DIDS and 0.2 mM amiloride caused an acidification of pHi (Fig. 2A), due to inhibition of the basolateral Na+/HCO3− cotransporters and Na+/H+ exchangers, which normally act to transport HCO3− into the duct cell from the blood (27). The effects of DIDS and amiloride are likely to be confined to the basolateral transporters: (i) because DIDS is unlikely to gain rapid access to the lumen of the sealed ducts due to its charged sulphonic acid groups, and (ii) because there are no amiloride-sensitive transport steps at the apical membrane of the small interlobular ducts used in this study. In addition, basolateral DIDS will block the basolateral anion exchanger (8, 31), which will normally act to transport HCO3− out of the cell. Thus, the rate at which pHi acidifies after exposure to DIDS and amiloride will reflect the intracellular buffering capacity and the rate at which HCO3− effluxes (i.e. is secreted) across the apical membrane on Cl−/HCO3− exchangers and CFTR Cl− channels (2, 27). Calcium-activated Cl− channels should not be active under the conditions used in this study.

Removal of DIDS and amiloride caused pHi to return to the control value (Fig. 2A), following which a second exposure to the inhibitors caused pHi to acidify again at the same rate (Fig. 2A). Fig. 2B shows that secretin (10 nM) markedly enhanced the rate at which pHi acidifies after addition of DIDS and amiloride. SP (20 nM) had no effect on the rate of pHi acidification in unstimulated ducts (Fig. 2C), but abolished the effect of secretin (compare Figs. 2B and 2D).

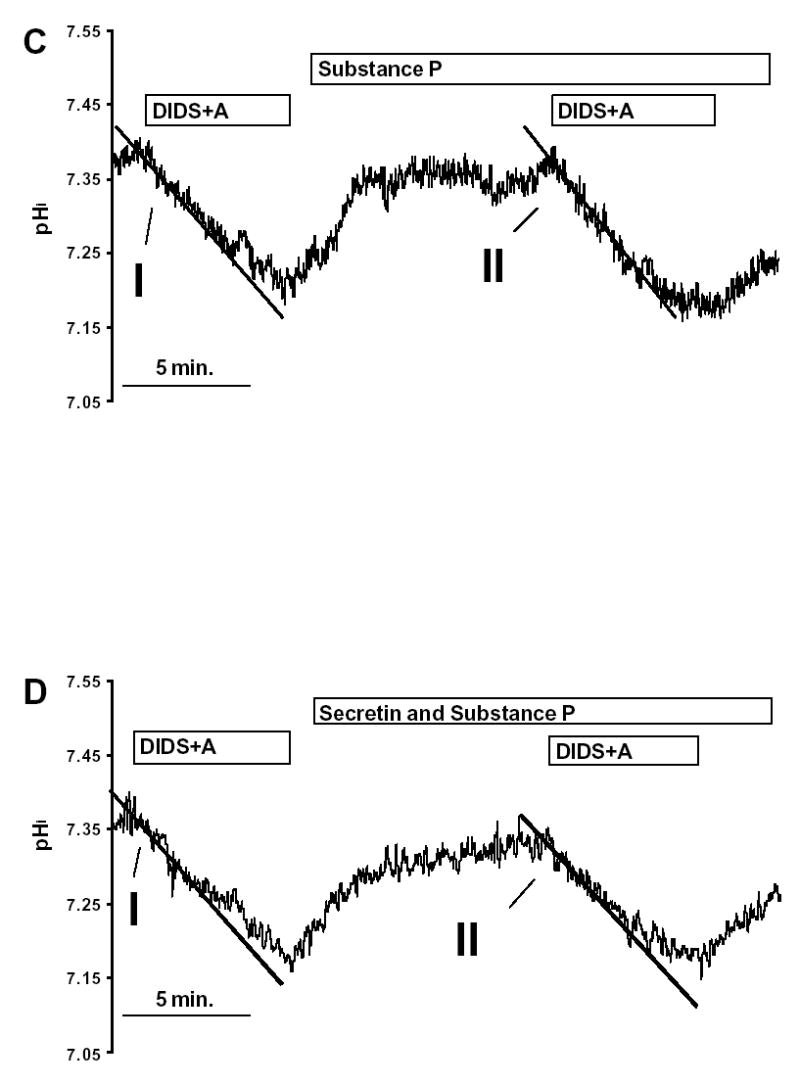

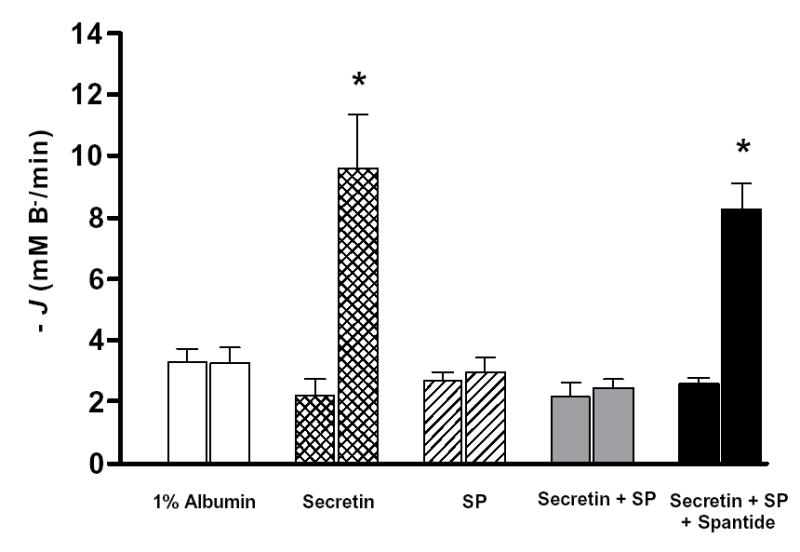

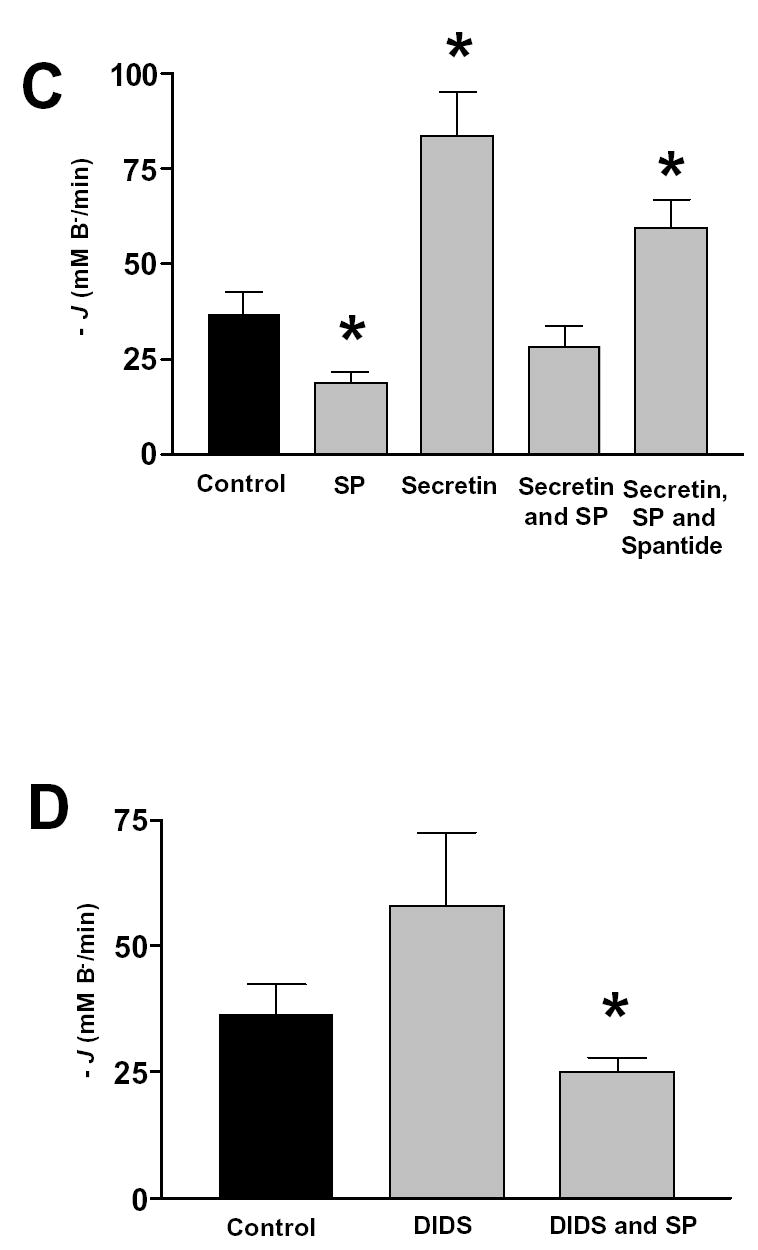

In Fig. 3, the changes in pHi observed after addition of DIDS and amiloride have been converted to a rate of base efflux (−J(B−)) using the rate of pHi change and the total buffering capacity of the cell (see Methods). Secretin (10 nM) increased −J(B−) about 5-fold. SP (20 nM) had no effect on the basal −J(B−), but the same dose completely blocked the secretin-stimulated increase in −J(B−) (Fig. 3). This inhibitory effect of SP on secretin-stimulated −J(B−) could be reversed by 20 nM spantide, a SP receptor antagonist (Fig. 3). These data are consistent with secretin enhancing HCO3− secretion and the inhibition of that process by SP. Since basolateral Na+/HCO3− cotransporters and Na+/H+ exchangers will be blocked by DIDS and amiloride, it is unlikely that SP could inhibit secretion by modulating their activity. We next sought to confirm this conclusion by investigating the effect of SP on pHi recovery after an acid load.

Fig. 3. Base fluxes calculated from the inhibitor stop experiments.

Base fluxes were calculated from the initial rate of pHi change (see Fig. 1) and the intracellular buffering capacity. Experimental protocols were similar to those shown in Fig. 1. The initial measurement being the control (first column in each section) and the second the test (second column in each section). Means ± SEM for groups of six ducts are shown. *: p<0.001 (paired t-test).

2. Effect of substance P on pHi recovery from acid load

In this series of experiments we tested whether SP affected the ability of duct cells to recover from an acid load. The transporters most likely to be involved in this process are the Na+/HCO3− cotransporter, the Na+/H+ exchanger and the H+ pump located on the basolateral membrane of the duct cell (2).

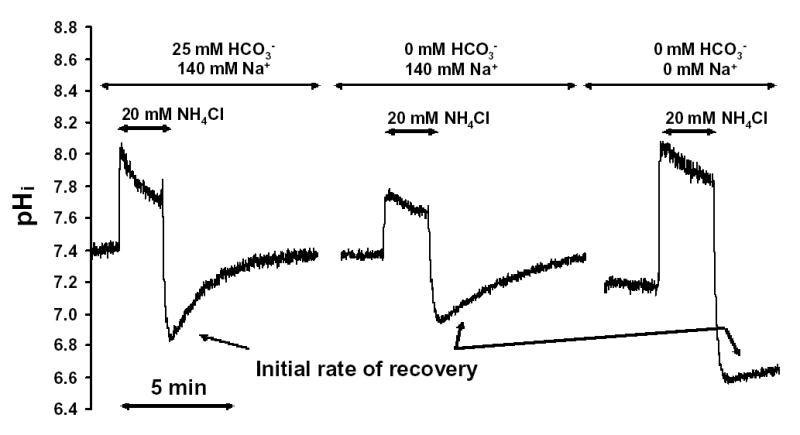

Exposure of duct cells to 20 mM NH4Cl induced an immediate rise in pHi due to the rapid entry of the lipophilic base, NH3 into the duct cell (Fig. 4). After the initial alkalinization, pHi started to recover due to influx of the less membrane permeant NH4+ and activation of cellular pHi regulatory mechanisms. After the removal of NH4Cl, pHi decreased rapidly. This acidification is caused by the dissociation of intracellular NH4+ into H+ and NH3, followed by the rapid diffusion of NH3 out of the cell. After the acidification, pHi starts to recover due to activation of pHi regulatory mechanisms (Fig. 4). Fig. 4 also shows that the removal of HCO3− markedly reduced the initial rate of pHi recovery following acid loading. In the absence of both HCO3− and sodium ions, pHi recovery from an acid load was virtually abolished (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Recovery of pHi following an acid load.

Duct cells were acid loaded by a brief exposure (3-min) to 20 mM NH4Cl followed by its sudden withdrawal. The initial rates of pHi recovery from the acid load (over the first 30sec) were calculated in each experiment. All the experiments were performed at 37 °C using a standard KREBS solution with or without Na+ or HCO3−, respectively. Each experiment was performed on a different duct.

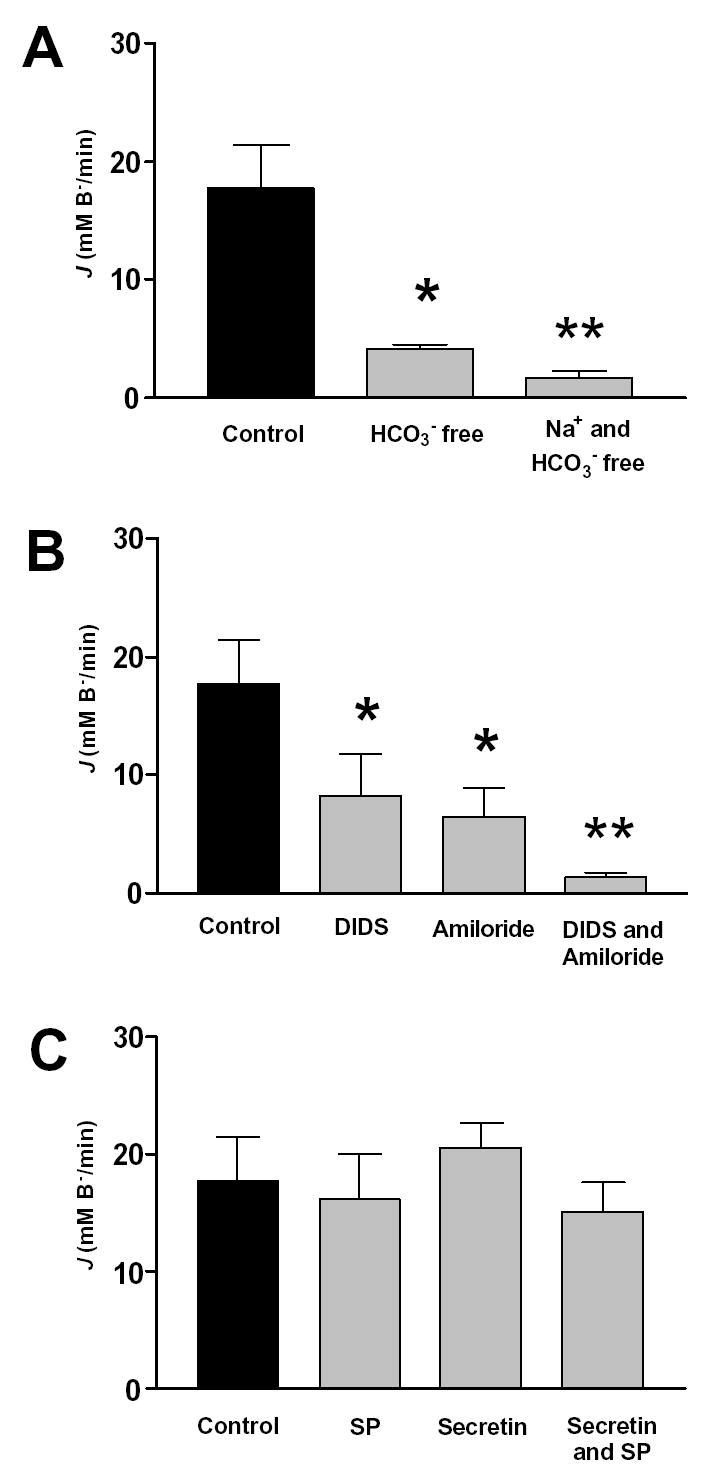

Figure 5 shows data from a series of experiments in which we measured the recovery of pHi, expressed as J(B−), following an acid load. The initial recovery J(B−) following an acid load was 17.8 ± 4.0 mM/min (n=6) in the standard HCO3− buffered solution (Fig. 5A). In a HCO3− free solution the recovery J(B−) decreased markedly to 4.1 ± 0.4 mM/min (n=6) and in a Na+ free and HCO3− free solution to 1.6 ± 0.4 mM/min (n=6) (Fig. 5A). These data indicate that pHi recovery after an acid load is dependent on the presence of extracellular HCO3− and Na+, implicating basolateral Na+/HCO3− cotransporters and Na+/H+ exchangers in this process. Therefore, the basolateral H + pump probably has only a marginal effect on pHi recovery from acid load.

Fig. 5. Base fluxes calculated from the acid load experiments.

Pancreatic ducts were treated as described in Fig. 4. The effect of (A) different solutions (HCO3− free and Na+ free solutions), (B) different inhibitors (DIDS and amiloride) and (C) different hormones and antagonists (secretin, SP, spantide) on base influx (J(B−)) are shown. In the SP and secretin-treated groups, 20nmol/l SP or 10 nmol/l secretin was given for 10 min. before the exposure of NH4Cl. Means ± SEM for groups of six ducts are shown. *: p<0.05 versus control, **:p<0.001 versus control

Consistent with these ideas, DIDS and amiloride alone markedly reduced initial recovery J(B−) values after an acid load by about 60% and 70% respectively (Fig. 5B). When the inhibitors were applied together, J(B−) was further reduced to 1.3 ± 0.02 mM/min (Fig. 5B), which is not significantly different from the rate of recovery observed in the absence of both Na+ and HCO3− (1.6 ± 0.04 n=6, p>0.05) (Fig. 5A). These data confirm that the basolateral Na+/HCO3− cotransporter and the Na+/H+ exchanger are the major base loaders in the duct cell. Figure 5C shows that neither SP (20 nM), secretin (10 nM) or a combination of the two agents had any effect on the recovery J(B−). As expected from these results, SP had no effect on recovery from an acid load in the presence of DIDS (Na+/H+ exchangers active) and no effect on pHi recovery in the presence of amiloride (Na+/HCO3− cotransporters active) (data not shown). These data confirm that SP has no effect in the major base loading transporter on the basolateral membrane of the duct cell.

3. Effect of SP on pHi recovery from alkaline load

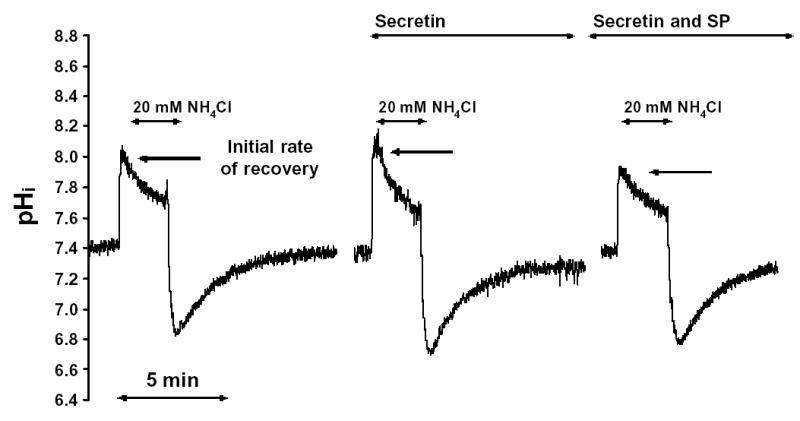

This series of experiments was performed to test whether SP has any effect on HCO3− efflux from the duct cells. Figure 6 shows that following the alkalization caused by exposure of ducts to 20mM NH4Cl, pHi started to recover in the continued presence of NH4Cl. Figure 6 also shows that the rate of pHi recovery was markedly increased by secretin (10 nM), and that the effect of secretin was inhibited by SP (20 nM).

Fig. 6. Recovery of pHi from an alkali load.

Pancreatic duct cells were alkali loaded by brief exposure to 3 min pulses of 20mM NH4Cl (or (NH4)2SO4). The initial rate of the pHi recovery was calculated in each experiment. All the experiments were performed at 37 °C using a standard HCO3− solution (containing 25mM HCO3−) with or without Cl−. In the secretin and SP experiments, 20nmol/l SP and/or 10 nmol/l secretin were given for 10 min. before the exposure of NH4Cl.

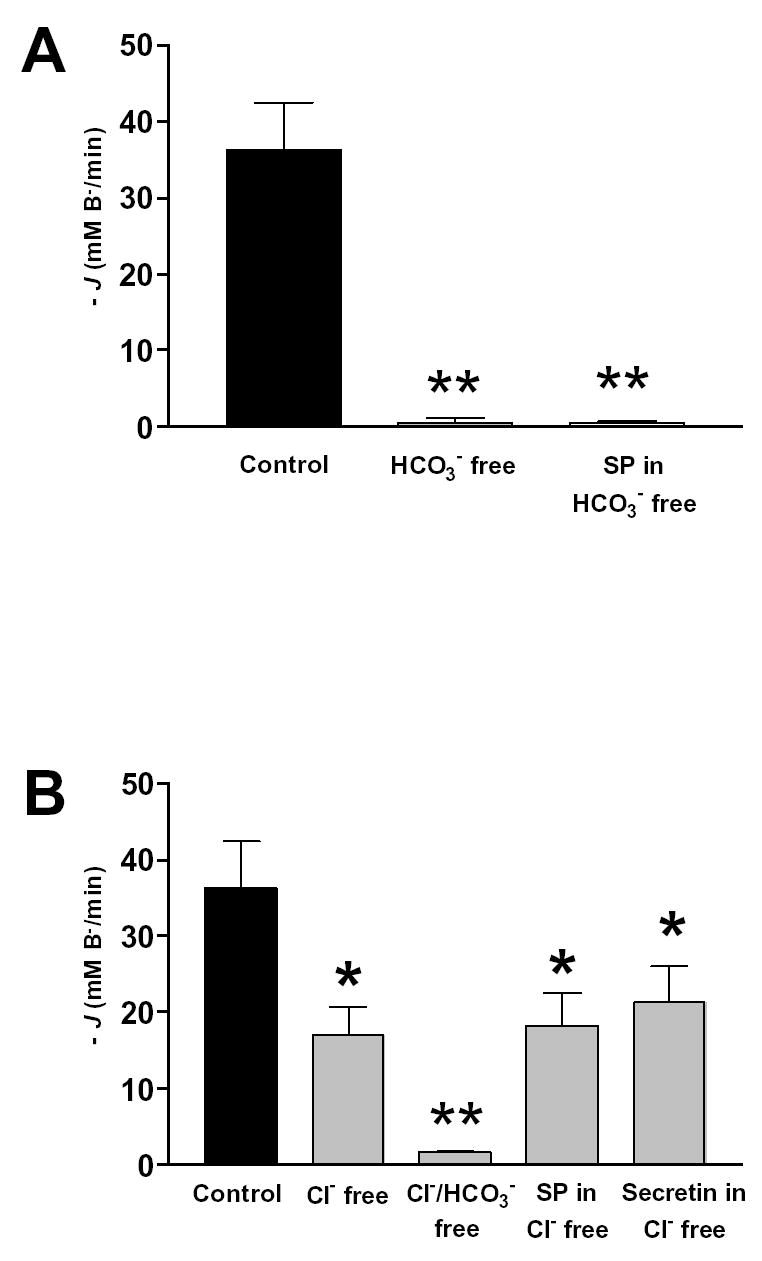

Figure 7 is a summary of the data obtained in this experimental series. The initial −J(B−) of the recovery from alkaline load was 36.3 ± 6.2 mM/min (n=6) in the standard HCO3− buffered solution (Fig. 7A). −J(B−) decreased to 0.6 ± 0.2 mM/min (n=6) in a HCO3− free solution and, under these conditions, SP had no detectable effect (Fig. 7A). −J(B−) also decreased, to 17.2 ± 3.6 mM/min (n=6) in a Cl− free solution, and to 1.6 ± 0.2 mM/min (n=6) in a Cl− free and HCO3− free solution (Fig. 7B). These data indicate that the recovery from an alkaline load is a HCO3− dependent process and, therefore, that the influx of NH4+ (derived from extracellular NH4Cl) has only a marginal effect on pHi recovery. In addition, pHi recovery after an alkali load consists of both Cl− dependent and Cl− independent HCO3− transport processes of about equal magnitude (Fig. 7B). Neither secretin nor SP had any effect on the recovery from alkaline load in a Cl− free solution, indicating that these agonists do not modulate Cl− independent HCO3− transport (Fig. 7B).

Fig. 7. Base fluxes calculated from the alkali load experiments.

Pancreatic ducts were treated as in described in Fig. 6. The effect on base efflux (−J(B−)) of (A) HCO3− free solutions, (B) Cl− free and Cl− and HCO3− free solutions. (C) secretin, SP, spantide in the standard HCO3− solution, and (D) DIDS in the standard HCO3− solution. Mean ± SEM for groups of six ducts are shown. *: p<0.05 versus control, **:p<0.001 versus control.

In the standard HCO3− buffered solution, 20 nM SP decreased −J(B−) to 18.7 ± 3.1 mM/min (n=6), while 10 nM secretin stimulated −J(B−) to 83.6 ± 11.6 mM/min (n=6) (Fig. 7C). Note that the control −J(B−) and the secretin-stimulated −J(B−) in these experiments are about 10-fold and 4-fold higher respectively than those measured in the inhibitor stop studies (Fig. 2). This difference might be explained by a higher intracellular HCO3− concentration after alkali loading of the duct cell. This secretin stimulated −J(B−) was inhibited by 20 nM SP (28.4 ± 5.2 mM/min) (n=6), and 20 nM spantide could block the inhibitory effect of SP (59.8 ± 7.6 mM/min) (n=6) (Fig. 7C). These data indicate that SP can inhibit a Cl− dependent, HCO3− efflux mechanism in the pancreatic duct cell. The cellular model suggests that there are three candidates for this mechanism: the Cl−/HCO3− exchangers located on the apical and basolateral membranes of the duct cell and apical CFTR, which is known to have a finite permeability to HCO3− ions (23).

To check whether the basolateral anion exchanger was involved, we examined the effects of DIDS on the pHi recovery after an alkali load. We reasoned that basolateral DIDS would inhibit −J(B−) after an alkali load if the basolateral anion exchanger was active. The effect of DIDS was rather variable, but in 9 experiments the disulphonic stilbene had no significant effect on −J(B−) after an alkali load (Fig. 7D). Importantly, SP significantly inhibited −J(B−) in the presence of DIDS, again suggesting that basolateral anion exchangers and Na+/HCO3− cotransporters are not targets for the peptide (Fig. 7D).

DISCUSSION

The undecapeptide SP has previously been reported to inhibit basal, secretin- and bombesin-stimulated fluid secretion from isolated rat pancreatic ducts (3), however, the cellular mechanisms of this inhibition have not been established. In this study, we provide evidence that SP inhibits HCO3− secretion in guinea pig pancreatic ducts by inhibiting a Cl− dependent HCO3− transport process that is located at the apical membrane of the duct cell.

In the first part of the study, we derived HCO3− secretion from the rate of intracellular acidification that occurs following the addition of DIDS and amiloride to the perifusion buffer (27). As these two inhibitors will block the base loading transporters (Na+/HCO3− cotransporters and Na+/H+ exchangers) and the acid loading transporter (Cl−/HCO3− exchanger) on the basolateral side of the duct cell, the rate of acidification should reflect the rate of HCO3− efflux across the apical membrane, i.e. the rate of HCO3− secretion. This conclusion is supported by the fact that 10 nM secretin, the physiological stimulant of pancreatic HCO3− secretion (2), increased -J(B−) about five-fold. Studies by others have shown that secretin stimulates the basal rate of fluid and HCO3− secretion from isolated guinea-pig ducts to a similar extent (27). We found that secretin-stimulated HCO3− efflux was completely blocked by 20 nM SP, an effect that was largely reversed by 20 nM spantide.

Next we designed experiments to test where in the HCO3− secretory mechanism SP exerts its effect. The fact that SP inhibits HCO3− efflux in the presence of basolateral DIDS and amiloride (see above), strongly suggests that the peptide does not exert its effect by either inhibition of the basolateral base loaders (Na+/HCO3− cotransporter and Na+/H+ exchanger) or activation of the basolateral acid loaders (Cl−/HCO3− exchanger). We confirmed this by investigating the effects of SP on the recovery from an acid load. After acid loading, the intracellular HCO3− concentration will be low (~6 mM following the first NH4Cl pulse in Fig. 4) and thus HCO3− flux across the apical membrane should also be low. Therefore, after acid loading the initial rate of pHi recovery will largely represent influx of base equivalents (i.e. HCO3− influx or H + efflux) across the basolateral membrane. Our finding that pHi recovery from an acid load is dependent on the presence of HCO3− and Na+, and is blocked by DIDS and amiloride, suggests that the Na+/HCO3− cotransporter and Na+/H+ exchanger are quantitatively the most important transporters involved in this process. Similar results have been reported by others (9). As expected, neither SP nor secretin had any effect on the initial J(B−) of recovery from an acid load, providing evidence that these peptides do not directly modulate the activity of the basolateral base loading transporters. Secretin also has no significant effect on pHi recovery from an acid load in rat pancreatic duct cells (22).

Finally, we examined the effect of SP on the initial rate of pHi recovery from an alkali load, induced by exposing the duct cells to 20 mM NH4Cl. Recovery of pHi under these conditions was dependent on the presence of HCO3− in the bathing medium, suggesting that it results from HCO3− efflux (i.e. secretion) out of the duct cell. Recovery from an alkali load was also reduced by about 50% in the absence of extracellular chloride, indicating that the recovery process consists of Cl− dependent and Cl− independent HCO3− transport in about equal measure.

Secretin increased −J(B−) after an alkaline load about 3-fold, consistent with −J(B−) representing HCO3− secretion. A modest, 1.4-fold, stimulatory effect of secretin on pHi recovery after an alkali load has also been reported in rat pancreatic duct cells (22). In contrast, secretin had no effect on −J(B−) when the experiments were performed in a Cl− free medium indicating that the hormone activates a Cl−-dependent, HCO3− transport mechanism in the duct cell. The Cl− dependency of pancreatic HCO3− secretion from the whole gland in vitro has been known for some time (see ref. 2 for a review). Similar results have been obtained with isolated rat ducts (4) and, more recently, in isolated microperfused guinea-pig ducts (30). Both the basal −J(B−), and the secretin-stimulated −J(B−), were markedly inhibited by SP, and this inhibitory effect was reversed by spantide. Interestingly, SP had no inhibitory effect on the residual −J(B−) remaining in a Cl− free medium, suggesting that the peptide inhibits the Cl− dependent HCO3− efflux mechanism present in the duct cell. Candidate transporters for this Cl− dependent HCO3− efflux mechanism are the basolateral and apical anion exchangers and apical CFTR. Since SP inhibited HCO3− efflux in the presence of basolateral DIDS and amiloride in the inhibitor stop experiments, it seems unlikely that the basolateral anion exchanger could be involved (see above). We confirmed this by investigating the effects of substance P on recovery from an alkaline load in the presence of DIDS. DIDS had no significant effect on the rate of −J(B−) under these conditions, indicating that pHi recovery after an alkali load cannot be mediated by either basolateral Cl−/HCO3− exchangers or the basolateral NaHCO3 cotransporter (working in reverse due to the elevated intracellular HCO3− concentration). Importantly, substance P continued to inhibit −J(B−) in the presence of DIDS, confirming that the peptide does not affect basolateral HCO3− transport in the duct cell.

These data point to the substance P inhibiting the activity of either one or both of the apical HCO3− transporters in the duct cell, that is the apical anion exchanger and CFTR. The fact that J(B−) following an alkali load in the presence of secretin is largely Cl− dependent suggests that the apical anion exchanger is the transporter that is modulated by substance P. We cannot completely exclude an effect on CFTR as this channel is known to conduct HCO3− ions, albeit less effectively than Cl− (PHCO3−/PCl− estimates vary between 0.1 and 0.5) (23). Moreover, we have recently shown that extracellular Cl− removal causes trans-inhibition of anion flux through CFTR, which might explain the fact that J(B−) after an alkali load was Cl− dependent (23). However, in patch clamp experiments on rat pancreatic duct cells, we were unable to detect a consistent inhibitory effect of SP on secretin-stimulated whole cell CFTR Cl− currents. Outward CFTR Cl− currents measured at −60 mV were 62 ± 10 pA/pF (n = 12 cells) in the presence of 10 nM-secretin and 36 ± 13 pA/pF (n = 11 cells) in the presence of 10 nM-secretin and 10 nM SP (P < 0.12, not significant) (Argent, B.E., H. McAlroy & M.A. Gray: unpublished observations). This observation suggests that neither HCO3− transport through CFTR, nor modulation of the apical anion exchanger by changes in intracellular Cl− concentration (caused by changes in CFTR activity), can explain the inhibitory effect of SP. However, a regulatory role for CFTR in SP's effect that is separate from its channel function remains a possibility. Interestingly, CFTR has recently been shown to activate luminal Cl−/HCO3− exchange in the submandibular and pancreatic ducts of mice by a mechanism that is unrelated to its Cl− channel function (16).

Molecular cloning has identified two anion exchangers families in mammalian cells, namely SLC4 (formerly AE) and SLC26 families (for refs. see 7). Expression of SLC4 isoforms in epithelial tissues is limited to the basolateral membrane (for refs. see 7). In contrast, SLC26 family members, of whom nine have now been identified (19), have been shown to be expressed on the apical membrane of epithelial cells (for refs. see 7). Strong candidates for the apical anion exchanger in pancreatic duct cells are SLC26A3 (down regulated in adenoma, DRA) and SLC26A6 (putative anion transporter 1, PAT1). Both DRA (20) and PAT1 (7) have been shown to act functionally as Cl−/HCO3− exchangers and have been localized to the apical membrane of pancreatic duct cells using immunocytochemistry (PAT1 - (18); DRA - (7)). There is mounting evidence that the expression and activity of SLC26 family can be regulated by CFTR, although the underlying mechanisms are unknown (5, 14, 16, 17).

The cellular signalling system that links SP receptor occupation to the apical anion exchanger remains to be determined. The undecapeptide binds to tachykinin receptors, which are seven transmembrane span receptors coupled to the Gq/G11 family of G-proteins (13). Activation of tachykinin receptors leads to activation of phospholipase C followed by the production of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate and diacylglycerol (DAG), which in turn lead to a rise in intracellular calcium concentration and activation of protein kinase C respectively (13). Previously, it has been reported that activation of PKC by phorbol 12,13-dibutyrate (PDBu) can inhibit fluid secretion by rat pancreatic ducts (6), and it is possible that SP exerts its effect on apical anion exchange via PKC mediated phosphorylation.

In conclusion, we have shown that SP inhibits basal and secretin-stimulated HCO3− efflux from the pancreatic duct cell. Inhibition occurs by modulation of a Cl− dependent HCO3− transport process, most probably the SLC26 anion exchanger on the apical membrane of the duct cell. This will need to be confirmed in microperfusion experiments, which will allow the activity of the apical anion exchanger to be studied directly. It will also be necessary to establish the intracellular signalling system utilised by SP and whether functional CFTR is required for SP's action.

Footnotes

Funded by a Wellcome Trust Travelling Fellowship (Grant No. 054406) to P.H.

Present address for P. Hegyi: First Department of Medicine, Albert Szent-Gyorgyi Medical University, P.O. Box 469, H-6701, Szeged, Hungary

References

- 1.Argent BE, Arkle S, Cullen MJ, Green R. Morphological, biochemical and secretory studies on rat pancreatic ducts maintained in tissue culture. Q J Exp Physiol. 1986;71:633–648. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1986.sp003023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Argent BE, Gray MA. Regulation and formation of fluid and electrolyte secretions by pancreatic ductal epithelium. In: Sirica AE, Longnecker DS, editors. Biliary and Pancreatic Ductal Epithelia. Pathobiology and Pathophysiology. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1997. pp. 349–377. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ashton N, Argent BE, Green R. Effect of vasoactive intestinal peptide, bombesin and substance P on fluid secretion by isolated rat pancreatic ducts. J Physiol. 1990;427:471–482. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ashton N, Argent BE, Green R. Characteristics of fluid secretion from isolated rat pancreatic ducts stimulated with secretin and bombesin. J Physiol. 1991;435:533–546. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choi JY, Muallem D, Kiselyov K, Lee MG, Thomas PJ, Muallem S. Aberrant CFTR-dependent HCO3- transport in mutations associated with cystic fibrosis. Nature. 2001;410:94–97. doi: 10.1038/35065099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Evans RL, Ashton N, Elliott AC, Green R, Argent BE. Interactions between secretin and acetylcholine in the regulation of fluid secretion by isolated rat pancreatic ducts. J Physiol. 1996;496.1:265–273. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greeley T, Shumaker H, Wang Z, Schweinfest CW, Soleimani M. Downregulated in adenoma and putative anion transporter are regulated by CFTR in cultured pancreatic duct cells. Am J Physiol. 2001;281:G1301–G1308. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2001.281.5.G1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ishiguro H, Naruse S, Kitagawa M, Suzuki A, Yamamoto A, Hayakawa T, Case RM, Steward MC. CO2 permeability and bicarbonate transport in microperfused interlobular ducts isolated from the guinea-pig pancreas. J Physiol. 2000;528.2:305–315. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00305.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ishiguro H, Steward MC, Lindsay ARG, Case RM. Accumulation of intracellular HCO3− by Na+-HCO3− cotransport in interlobular ducts from guinea-pig pancreas. J Physiol. 1996;495.1:169–178. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ishiguru H, Steward MC, Sohma Y, Kubota T, Kitagwa M, Kondo T, Case RM, Hayakawa T, Naruse S. Membrane potential and bicarbonate secretion in isolated interlobular ducts from guinea-pig pancreas. J Gen Physiol. 2002;120:617–628. doi: 10.1085/jgp.20028631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iwatsuki N, Yamgishi F, Chiba S. Effects of substance P on pancreatic exocrine secretion stimulated by secretin, dopamine and cholecystokinin in dogs. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1986;13:663–670. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1986.tb02395.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Katoh K. Effects of substance P on fluid and amylase secretion in exocrine pancreas of rat and mouse. Res Vet Sci. 1984;36:147–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khawaja AM, Rogers DF. Tachykinins: receptor to effector. Int J Cell Biol. 1996;28:721–738. doi: 10.1016/1357-2725(96)00017-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ko SBH, Shcheynikov N, Choi JY, Luo X, Ishibashi K, Thomas PJ, Kim JY, Kim KH, Lee MG, Naruse S, Muallem S. A molecular mechanism for aberrant CFTR-dependent HCO3− transport in cystic fibrosis. EMBO J. 2002;21:5662–5672. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Konturek SJ, Jaworek J, Tasler J, Cieszkowski M, Pawlik W. Effect of substance P and its C-terminal hexapeptide on gastric and pancreatic secretion in the dog. Am J Physiol Gastro. 1981;241:G74–G81. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1981.241.1.G74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee MG, Choi JY, Luo X, Strickland E, Thomas PJ, Muallem S. Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator regulates luminal Cl−/HCO3− exchange in mouse submandibular and pancreatic ducts. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:14670–14677. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.21.14670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee MG, Wigley WC, Zeng W, Noel LE, Marino CR, Thomas PJ, Muallem S. Regulation of Cl−/HCO3− exchange by cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator expressed in NIH 3T3 and HEK 293 cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:3414–3421. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.6.3414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lohi H, Kujala M, Kerkelä E, Saarialho-Kere U, Kestilä M, Kere J. Mapping of five putative anion transporter genes in human and characterization of SLC26A6, a candidate gene for pancreatic anion exchanger. Genomics. 2000;70:102–112. doi: 10.1006/geno.2000.6355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lohi H, Kujala M, Mäkelä S, Lehtonen E, Kestilä M, Saarialho-Kere U, Markovich D, Kere J. Functional characterisation of three novel tissue-specific anion exchangers SLC26A7, −A8, and −A9. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:14246–14254. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111802200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Melvin JE, Park K, Richardson L, Schultheis PJ, Shull GE. Mouse down-regulated in adenoma (DRA) is an intestinal Cl−/HCO3− exchanger and is upregulated in colon of mice lacking the NHE3 Na+/H+ exchanger. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:22855–22861. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.32.22855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nilsson G, Brodin E. Tissue distribution of substance P-like immunoreactivity in dog, rat and mouse. In: von Euler U, Pernow B, editors. Substance P. New York: Raven Press; 1977. pp. 49–54. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Novak I, Christoffersen BC. Secretin stimulates HCO3− and acetate efflux but not Na+/HCO3− uptake in rat pancreatic ducts. Pflügers Arch. 2001;441:761–771. doi: 10.1007/s004240000472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O'Reilly CM, Winpenny JP, Argent BE, Gray MA. Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator currents in guinea pig pancreatic duct cells: inhibition by bicarbonate ions. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:1187–1196. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(00)70372-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sharkey KA, Williams RG, Dockray CJ. Sensory substance P innervation of the stomach and pancreas. Demonstration of capsaicin-sensitive sensory neurones in the rat by combined immunohistochemistry and retrograde tracing. Gastroenterology. 1984;87:914–921. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sohma Y, Gray MA, Imai Y, Argent BE. HCO3− transport in a mathematical model of the pancreatic ductal epithelium. J Membr Biol. 2000;176:77–100. doi: 10.1007/s00232001077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suzuki A, Naruse S, Kitagawa M, Ishiguro H, Yoshikawa T, Ko SBH, Yamamoto A, Hamada H, Hayakawa T. 5-hydroxytryptamine strongly inhibits fluid secretion in guinea pig pancreatic duct cells. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:749–756. doi: 10.1172/JCI12312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Szalmay G, Varga G, Kajiyama F, Yang X-S, Lang TF, Case RM, Steward MC. Bicarbonate and fluid secretion by cholecystokinin, bombesin and acetylcholine in isolated guinea-pig pancreatic ducts. J Physiol. 2001;535.3:795–807. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00795.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thomas JA, Buchsbaum RN, Zimniak A, Racker E. Intracellular pH-measurements in Ehrlich ascites tumor cells utilizing spectroscopic probes generated in situ. Biochemistry. 1979;18:2210–2218. doi: 10.1021/bi00578a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weintraub WH, Machen TE. pH regulation in hepatoma cells: roles for Na-H exchange, Cl-HCO3 exchange, and Na-HCO3 cotransport. Am J Physiol. 1989;257:G317–G327. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1989.257.3.G317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang X-S, Ishiguro H, Case RM, Steward MC. Dependence of HCO3− secretion on luminal Cl− in interlobular ducts isolated from guinea-pig pancreas. J Physiol. 1999;517P:3P. (abstract). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhao H, Star RA, Muallem S. Membrane localization of H+ and HCO3− transporters in the rat pancreatic duct. J Gen Physiol. 1994;104:57–85. doi: 10.1085/jgp.104.1.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]