Abstract

Background

Percutaneous vertebroplasty remains widely used to treat osteoporotic vertebral fractures although our 2015 Cochrane review did not support its role in routine practice.

Objectives

To update the available evidence of the benefits and harms of vertebroplasty for treatment of osteoporotic vertebral fractures.

Search methods

We updated the search of CENTRAL, MEDLINE and Embase and trial registries to 15 November 2017.

Selection criteria

We included randomised and quasi‐randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of adults with painful osteoporotic vertebral fractures, comparing vertebroplasty with placebo (sham), usual care, or another intervention. As it is least prone to bias, vertebroplasty compared with placebo was the primary comparison. Major outcomes were mean overall pain, disability, disease‐specific and overall health‐related quality of life, patient‐reported treatment success, new symptomatic vertebral fractures and number of other serious adverse events.

Data collection and analysis

We used standard methodologic procedures expected by Cochrane.

Main results

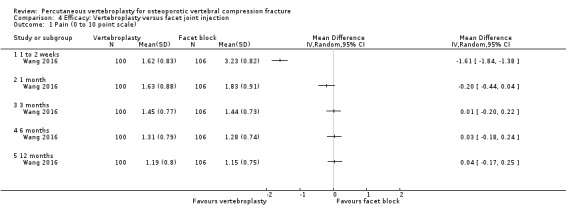

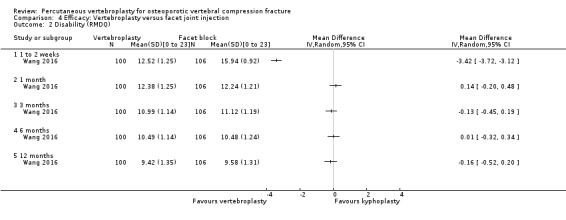

Twenty‐one trials were included: five compared vertebroplasty with placebo (541 randomised participants), eight with usual care (1136 randomised participants), seven with kyphoplasty (968 randomised participants) and one compared vertebroplasty with facet joint glucocorticoid injection (217 randomised participants). Trial size varied from 46 to 404 participants, most participants were female, mean age ranged between 62.6 and 81 years, and mean symptom duration varied from a week to more than six months.

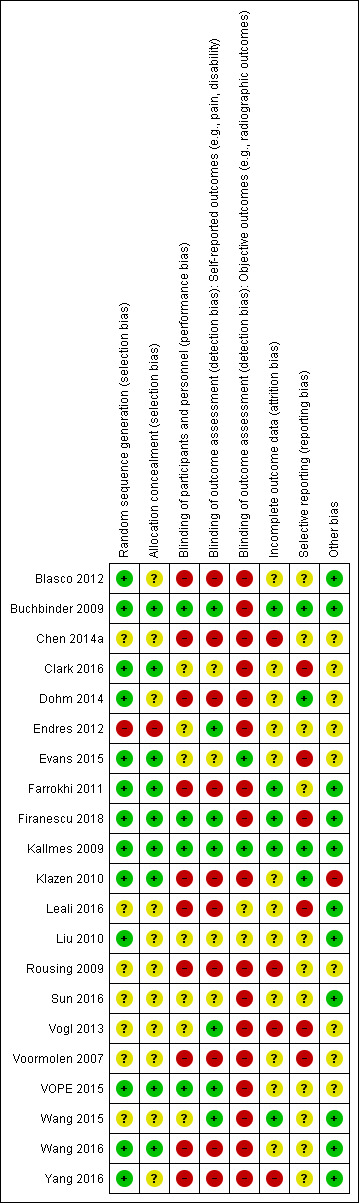

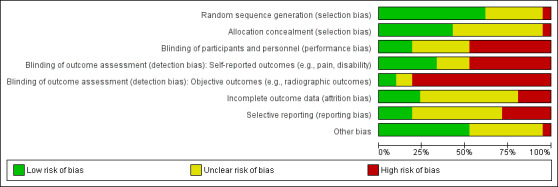

Four placebo‐controlled trials were at low risk of bias and one was possibly susceptible to performance and detection bias. Other trials were at risk of bias for several criteria, most notably due to lack of participant and personnel blinding.

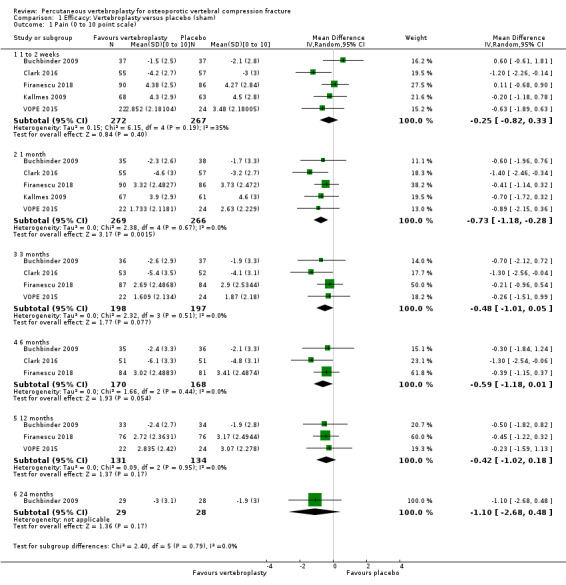

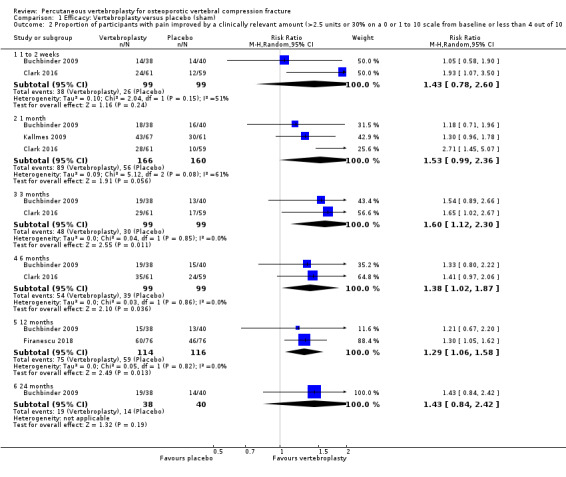

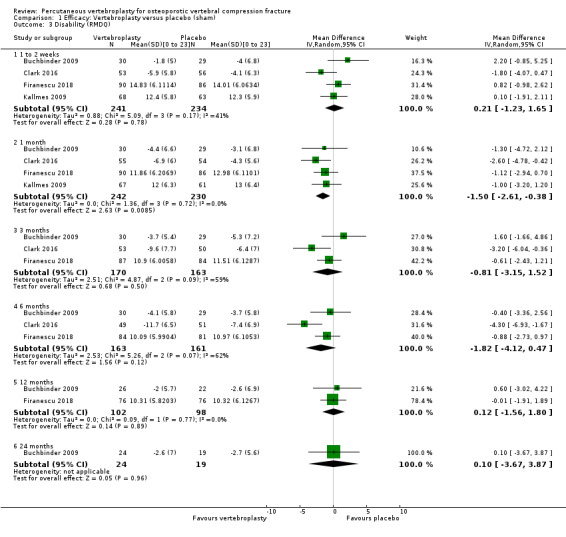

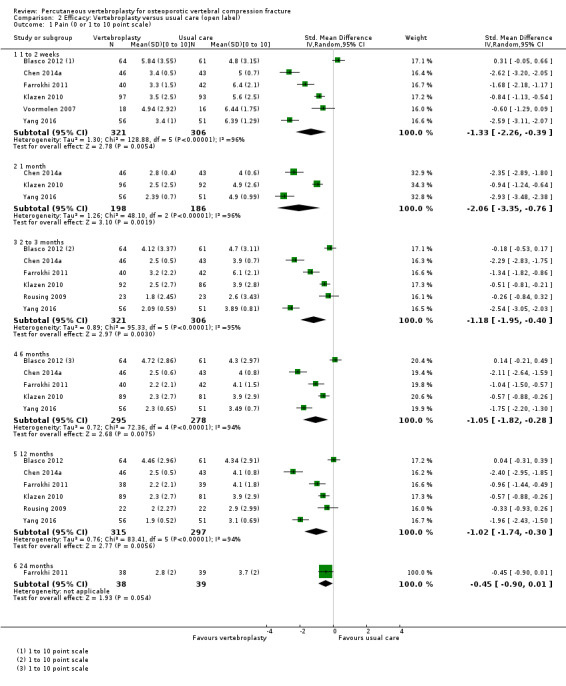

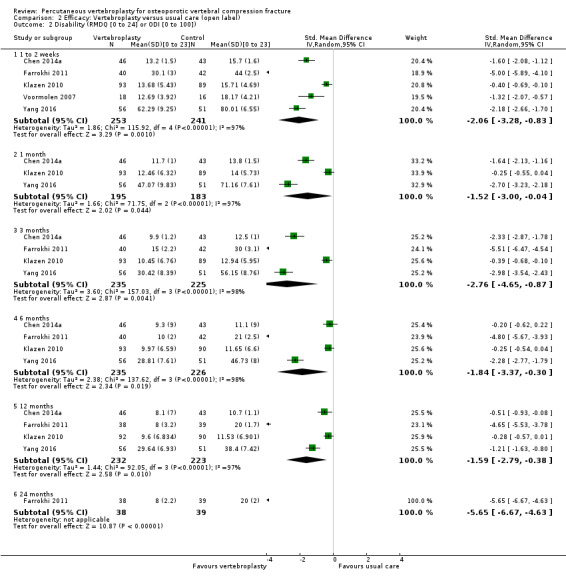

Compared with placebo, high‐ to moderate‐quality evidence from five trials indicates that vertebroplasty provides no clinically important benefits with respect to pain, disability, disease‐specific or overall quality of life or treatment success at one month. Evidence for quality of life and treatment success was downgraded due to possible imprecision. Evidence was not downgraded for potential publication bias as only one placebo‐controlled trial remains unreported. Mean pain (on a scale zero to 10, higher scores indicate more pain) was five points with placebo and 0.7 points better (0.3 better to 1.2 better) with vertebroplasty, an absolute pain reduction of 7% (3% better to 12% better, minimal clinical important difference is 15%) and relative reduction of 10% (4% better to 17% better) (five trials, 535 participants). Mean disability measured by the Roland‐Morris Disability Questionnaire (scale range zero to 23, higher scores indicate worse disability) was 14.2 points in the placebo group and 1.5 points better (0.4 better to 2.6 better) in the vertebroplasty group, absolute improvement 7% (2% to 11% better), relative improvement 9% better (2% to 15% better) (four trials, 472 participants).

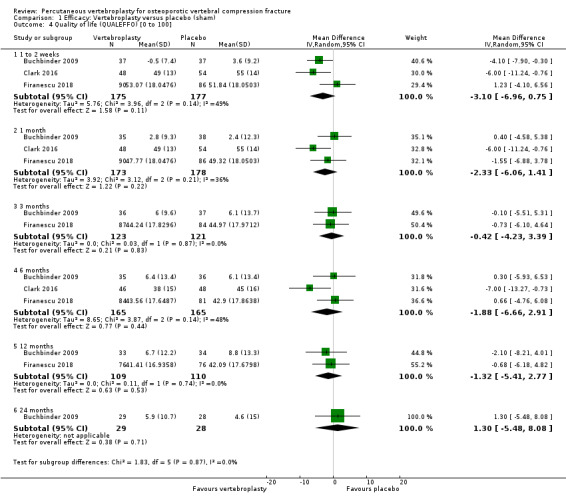

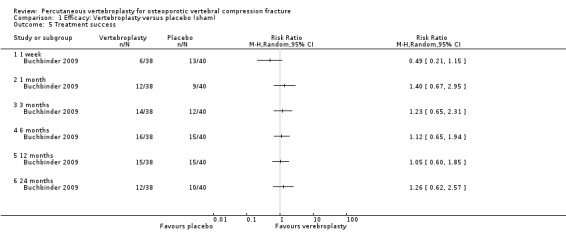

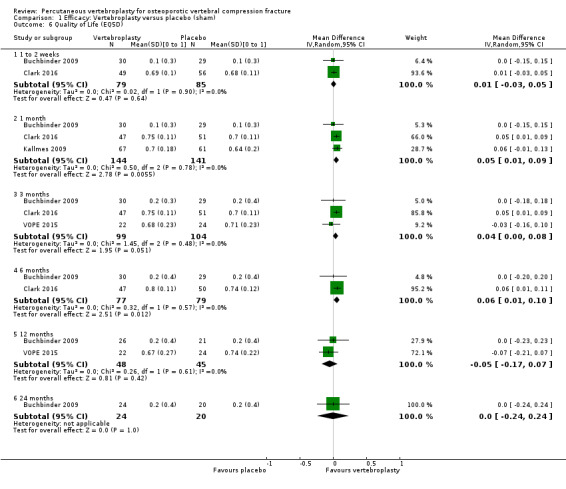

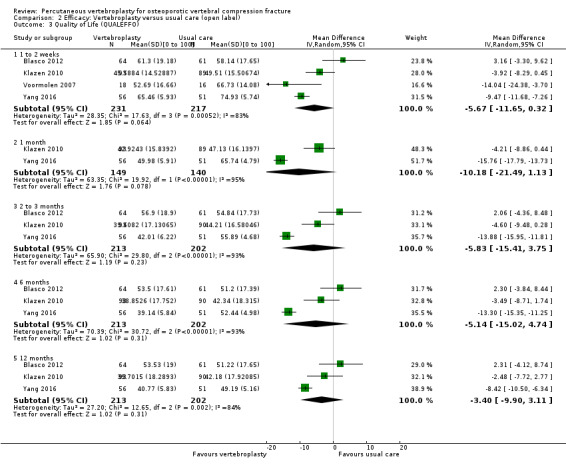

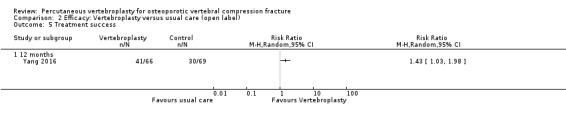

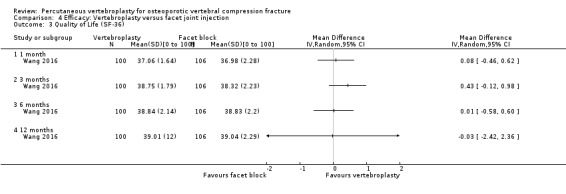

Disease‐specific quality of life measured by the Quality of Life Questionnaire of the European Foundation for Osteoporosis (QUALEFFO) (scale zero to 100, higher scores indicating worse quality of life) was 62 points in the placebo group and 2.3 points better (1.4 points worse to 6.7 points better), an absolute imrovement of 2% (1% worse to 6% better); relative improvement 4% better (2% worse to 10% better) (three trials, 351 participants). Overall quality of life (European Quality of Life (EQ5D), zero = death to 1 = perfect health, higher scores indicate greater quality of life) was 0.38 points in the placebo group and 0.05 points better (0.01 better to 0.09 better) in the vertebroplasty group, absolute improvement: 5% (1% to 9% better), relative improvement: 18% (4% to 32% better) (three trials, 285 participants). In one trial (78 participants), 9/40 (or 225 per 1000) people perceived that treatment was successful in the placebo group compared with 12/38 (or 315 per 1000; 95% CI 150 to 664) in the vertebroplasty group, RR 1.40 (95% CI 0.67 to 2.95), absolute difference: 9% more reported success (11% fewer to 29% more); relative change: 40% more reported success (33% fewer to 195% more).

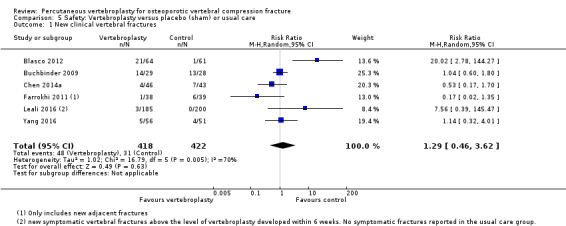

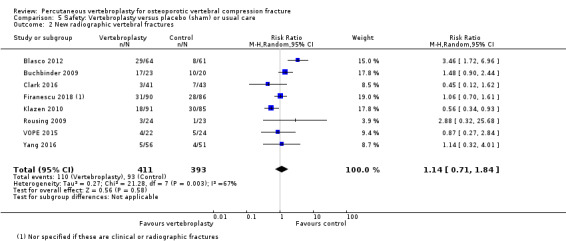

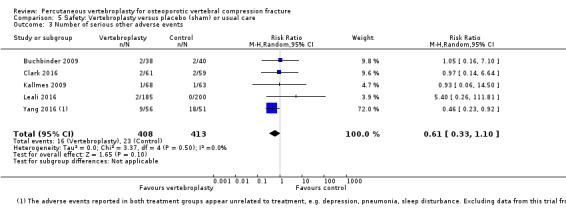

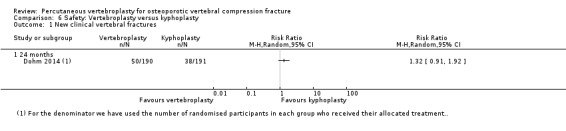

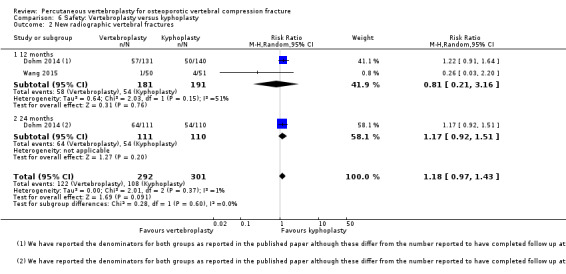

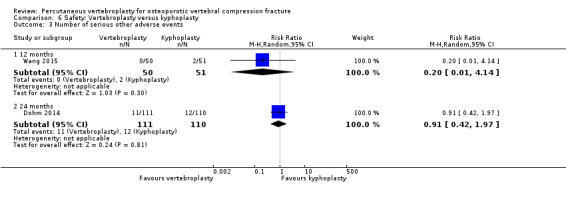

Low‐quality evidence (downgraded due to imprecision and potential for bias from the usual‐care controlled trials) indicates uncertainty around the risk estimates of harms with vertebroplasty. The incidence of new symptomatic vertebral fractures (from six trials) was 48/418 (95 per 1000; range 34 to 264)) in the vertebroplasty group compared with 31/422 (73 per 1000) in the control group; RR 1.29 (95% CI 0.46 to 3.62)). The incidence of other serious adverse events (five trials) was 16/408 (34 per 1000, range 18 to 62) in the vertebroplasty group compared with 23/413 (56 per 1000) in the control group; RR 0.61 (95% CI 0.33 to 1.10). Notably, serious adverse events reported with vertebroplasty included osteomyelitis, cord compression, thecal sac injury and respiratory failure.

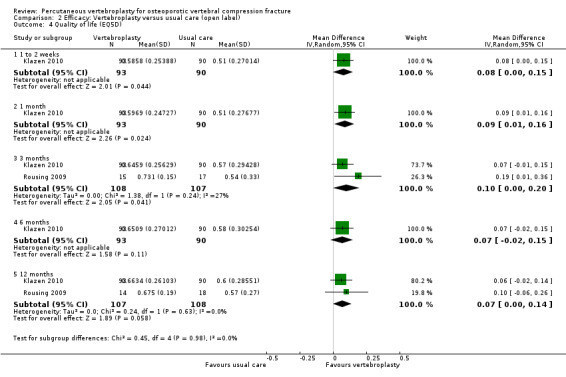

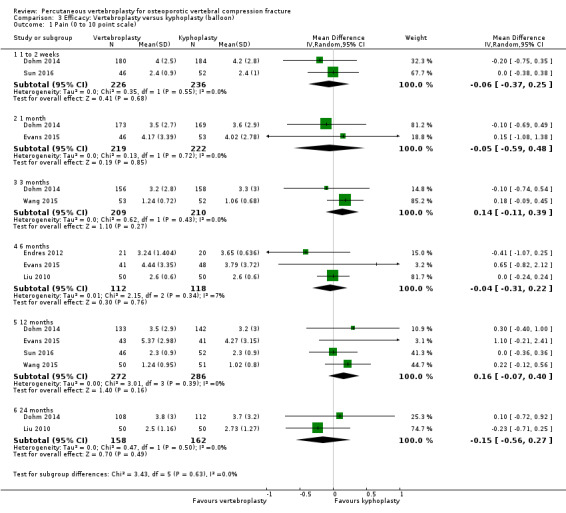

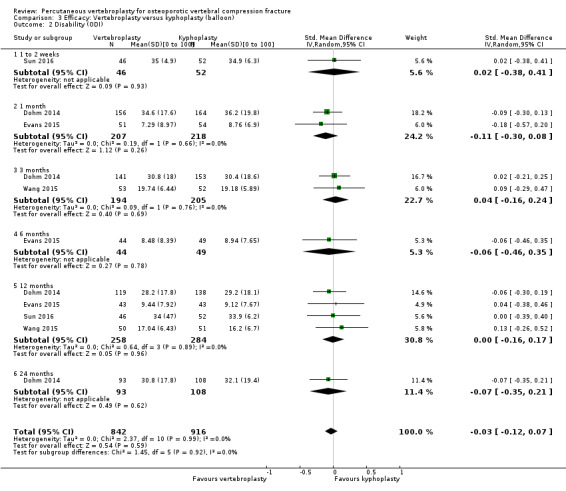

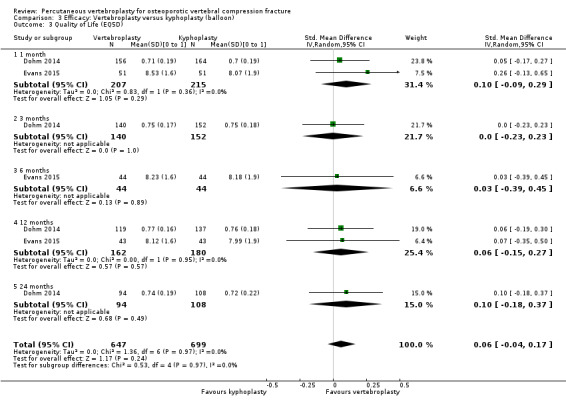

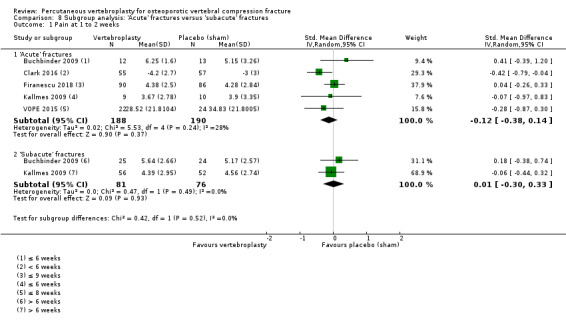

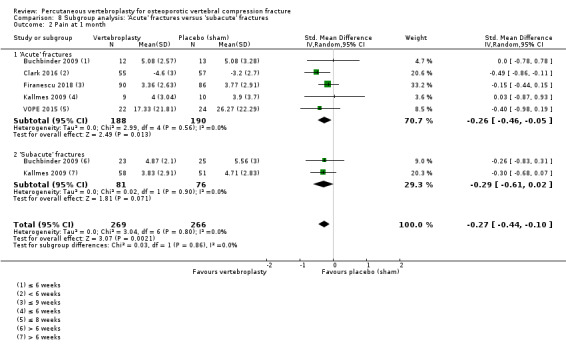

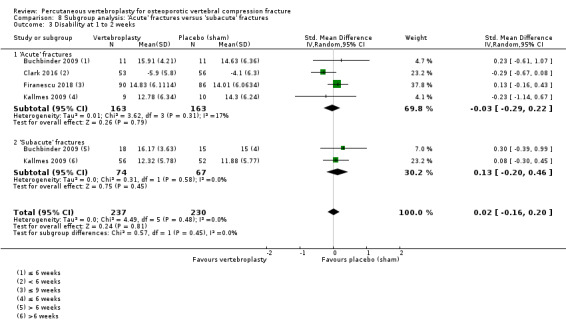

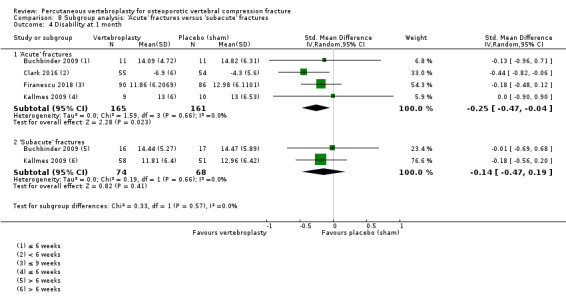

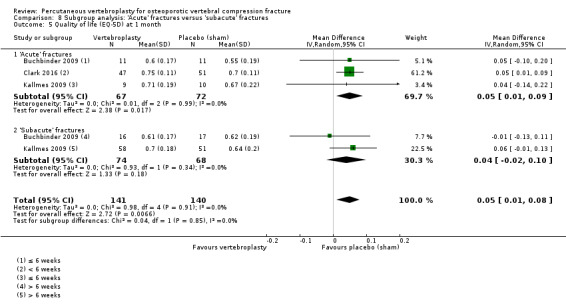

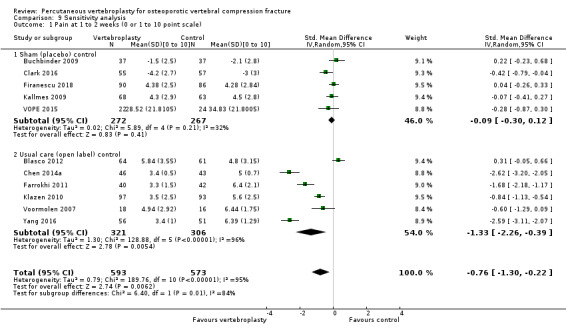

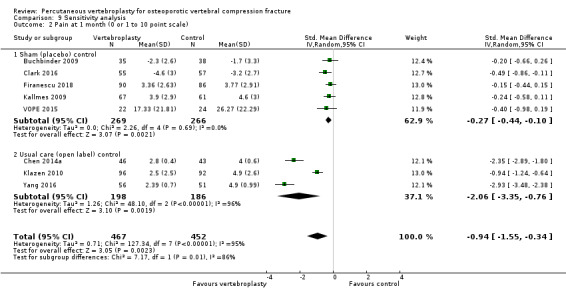

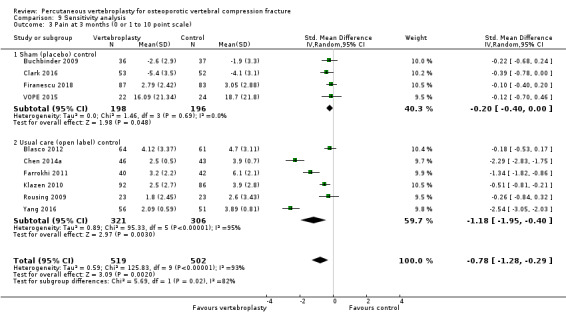

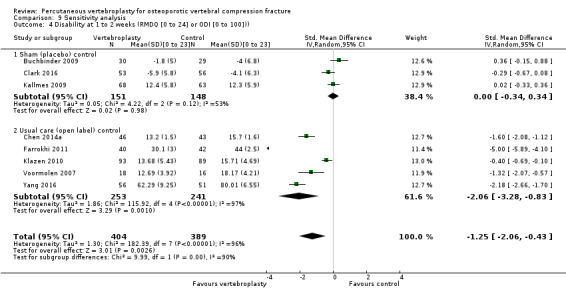

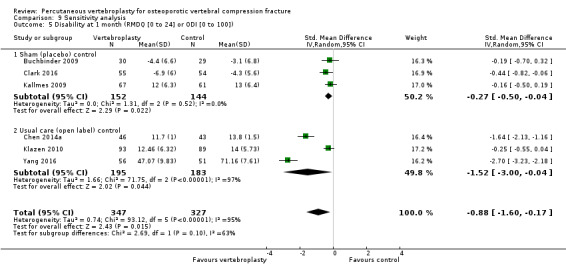

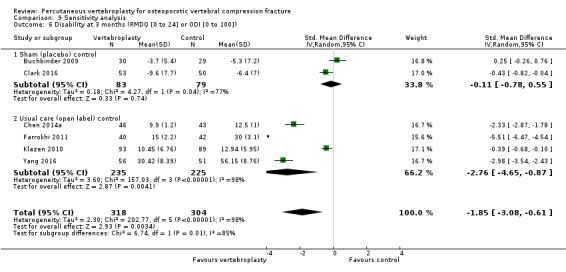

Our subgroup analyses indicate that the effects did not differ according to duration of pain (acute versus subacute). Including data from the eight trials that compared vertebroplasty with usual care in a sensitivity analyses altered the primary results, with all combined analyses displaying considerable heterogeneity.

Authors' conclusions

We found high‐ to moderate‐quality evidence that vertebroplasty has no important benefit in terms of pain, disability, quality of life or treatment success in the treatment of acute or subacute osteoporotic vertebral fractures in routine practice when compared with a sham procedure. Results were consistent across the studies irrespective of the average duration of pain.

Sensitivity analyses confirmed that open trials comparing vertebroplasty with usual care are likely to have overestimated any benefit of vertebroplasty. Correcting for these biases would likely drive any benefits observed with vertebroplasty towards the null, in keeping with findings from the placebo‐controlled trials.

Numerous serious adverse events have been observed following vertebroplasty. However due to the small number of events, we cannot be certain about whether or not vertebroplasty results in a clinically important increased risk of new symptomatic vertebral fractures and/or other serious adverse events. Patients should be informed about both the high‐ to moderate‐quality evidence that shows no important benefit of vertebroplasty and its potential for harm.

Plain language summary

Vertebroplasty for treating spinal fractures due to osteoporosis

Background

Osteoporosis is characterised by thin, fragile bones and may result in minimal trauma fractures of the spine bones (vertebrae). They can cause severe pain and disability.

Vertebroplasty involves injecting medical‐grade cement into a fractured vertebra, under light sedation or general anaesthesia. The cement hardens in the bone space to form an internal cast.

Study characteristics

This Cochrane review is current to November 2017. Studies compared vertebroplasty versus placebo (no cement injected) (five studies, 541 participants); usual care (eight studies, 1136 participants); kyphoplasty (similar, but before cement is injected a balloon is expanded in the fractured vertebra; seven studies, 968 participants) and facet joint steroid injection (one study, 217 participants). Trials were performed in hospitals in 15 countries, the majority of participants were female, mean age ranged between 63.3 and 80 years, and symptom duration ranged from a week to six months or more. Eight trials received at least some funding from medical device manufacturers and only two reported that they had no role in the trial.

Key results

Compared with a placebo (fake) procedure, vertebroplasty resulted in little benefit at one month:

Pain (lower scores mean less pain)

Improved by 7% (3% better to 12% better), or 0.7 points (0.3 better to 1.2 better) on a zero‐0 to 10‐point scale.

• People who had vertebroplasty rated their pain as 4.3 points.

• People who had placebo rated their pain as 5 points.

Disability (lower scores mean less disability)

Improved by 7% (2% better to 11% better), or 1.5 points (0.4 better to 2.6 better) on a zero to 23‐point scale.

• People who had vertebroplasty rated their disability as 12.7 points.

• People who had placebo rated their disability as 14.2 points.

Vertebral fracture or osteoporosis‐specific quality of life (lower scores mean better quality of life)

Better by 2% (1% worse to 6% better), or 2.33 points better (1.41 worse to 6.06 better) on a zero to 100‐point scale.

• People who had vertebroplasty rated their quality of life related to their fracture as 59.7 points.

• People who had placebo rated their quality of life related to their fracture as 62 points.

Overall quality of life (higher scores mean better quality of life)

Improved by 5% (1% better to 9% better), or 0.05 units (0.01 better to 0.09 better) on a zero = death to one = perfect health scale.

• People who had vertebroplasty rated their general quality of life as 0.43 points.

• People who had placebo rated their general quality of life as 0.38 points.

Treatment success (defined as pain moderately or a great deal better)

9% more people rated their treatment a success (11% fewer to 29% more), or nine more people out of 100.

• 32 out of 100 people reported treatment success with vertebroplasty.

• 23 out of 100 people reported treatment success with placebo.

Compared with a placebo or usual care:

New symptomatic vertebral fractures (at 12 to 24 months)

3% more new fractures with vertebroplasty (8% fewer to 13% more), or one more person out of 100.

• 10 out of 100 people had a new fracture with vertebroplasty.

• 7 out of 100 people had a new fracture with placebo or usual care.

Other serious adverse events:

1% fewer people (6% fewer to 4% more), had other serious adverse events with vertebroplasty; relative change 39% fewer (67% fewer to 10% more).

• 4 out of 100 people reported other serious adverse events with vertebroplasty.

• 5 out of 100 people reported other serious adverse events with placebo.

Quality of the evidence

High‐quality evidence shows that vertebroplasty does not provide more clinically important benefits than placebo. We are less certain of the risk of new vertebral fractures or other serious effects; quality was moderate due to the small number of events.

Serious adverse events that may occur include spinal cord or nerve root compression due to cement leaking out from the bone, cement leaking into the blood stream, rib fractures, infection in the bone, fat leaking into the bloodstream, damage to the covering of the spinal cord that could result in leakage of cerebrospinal fluid, anaesthetic complications and death.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Vertebroplasty for osteoporotic vertebral compression fracture.

| Vertebroplasty for osteoporotic vertebral compression fracture | ||||||

| Patient or population: people with osteoporotic vertebral compression fracture Settings: hospital, various countries including Australia, USA, UK, Canada, several European countries, Iran, China, Taiwan Intervention: vertebroplasty versus placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Placebo1 | Vertebroplasty | |||||

| Pain Scale from: 0 to 10, 0 is no pain. Follow‐up: 1 month | The mean pain in the control groups was 5 points | The mean pain in the intervention groups was 0.7 points better (0.3 better to 1.2 better) | 535 (5 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high2 | Absolute change 7% better (3% better to 12% better); relative change 10% better (4% better to 17% better)3 | |

| Disability (Roland‐Morris Disability Questionnaire) Scale from: 0 to 23; 0 is no disability. Follow‐up: 1 month | The mean disability in the control groups was 14.2 points | The mean disability in the intervention groups was 1.5 points better (0.4 better to 2.6 better) | 472 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high2 | Absolute change 7% better (2% better to 11% better); relative change 9% better (2% better to 15% better)3 | |

| Disease‐specific quality of Life (QUALEFFO) Scale from: 0 to 100; 0 is best. Follow‐up: 1 month | The mean quality of life (QUALEFFO) in the control groups was 62 points | The mean quality of life in the intervention groups was 2.33 points better (1.41 worse to 6.06 better) | 351 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high2 | Absolute change 2% better (1% worse to 6% better); relative change 4% better (2% worse to 10% better)3 | |

| Overall quality of Life (EQ5D) Scale from: 0 to 1; 1 is best. Follow‐up: 1 month | The mean quality of life (EQ‐5D) in the control groups was 0.38 points | The mean quality of life in the intervention groups was 0.05 points better (0.01 better to 0.09 better) | 285 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate4 | Absolute change 5% better (1% better to 9% better); relative change 18% improvement (4% better to 32% better)3 | |

|

Participant global assessment of success (People perceived their pain as better) Follow‐up: 1 month |

225 per 1000 | 315 per 1000 (150 to 664) | RR 1.40 (0.67 to 2.95) | 78 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate4 | Absolute difference 9% more reported success (11% fewer to 29% more); relative change 40% more reported success (33% fewer to 195% more) |

|

Incident symptomatic vertebral fractures Follow‐up: 12 ‐24 months |

73 per 1000 |

95 per 1000 (34 to 264) |

RR 1.29 (0.46 to 3.62) | 840 (6 studies)5 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low4,6 | Absolute difference 3% more fractures with vertebroplasty (8% fewer to 13% more); relative difference 29% more (54% fewer to 262% more) |

| Other serious adverse events Follow‐up: 12‐24 months | 56 per 1000 | 34 per 1000 (18 to 62) | RR 0.61 (0.33 to 1.10) | 821 (5 studies)5 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low4,6 | Absolute difference 1% fewer events with vertebroplasty (6% fewer to 4% more); relative change 39% fewer (67% fewer to 10% more) |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; SMD: Standardised mean difference; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 For incident vertebral fractures the comparison includes two placebo (sham)‐controlled trials and three trials that compared vertebroplasty versus usual care.

2 The internal validity of the five placebo‐controlled trials that have full or some results available is high. Four trials have published their results in peer‐reviewed journals (Buchbinder 2009; Clark 2016; Firanescu 2018; Kallmes 2009) while a fifth trial (VOPE 2015), completed in April 2014, was published as a thesis (http://www.forskningsdatabasen.dk/en/catalog/2371744560), and reported at a conference. Therefore we did not downgrade the evidence due to suspected publication bias although the results of one additional placebo‐controlled trial (VERTOS V) remain unpublished. This trial was previously reported as completed in June 2015, but its status has been changed to 'enrolling by invitation', at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01963039. While publication bias is possible, it is unlikely the conclusions will change when data from this trial become available.

3 Relative changes calculated as absolute change (mean difference) divided by mean at baseline in the placebo group from Buchbinder 2009 (values were: 7.1 points on 0 to 10 point VAS pain; 17.3 points on 0 to 23 point Roland‐Morris Disability questionnaire; 0.28 points on EQ‐5D quality of life scale; 59.6 points on the QUALEFFO scale).

4 Downgraded due to imprecision: the 95% confidence intervals do not exclude a clinically important change (defined as 1.5 points on the 0 to 10 pain scale; 2 to 3 points on the 0 to 23 point RMDQ scale; 0.074 on the 0 to 1 EQ‐5D quality of life scale, and 10 points on the 0 to 100 QUALEFFO scale); or for dichotomous outcomes the total number of participants was small, or number of events was small (<200); or data were from a single trial only

5 Pooled both placebo and usual care comparisons in the safety analyses.

6 Downgraded due to the possibility of detection bias in the studies with a usual care control group.

Background

Description of the condition

Vertebral compression fractures are among the most common type of fracture in patients with osteoporosis (Ström 2011). The estimated incidence of osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures in individuals 50 years or older has been reported to be 307 per 100,000 year based upon a German study, with the rate in women aged between 85 and 89 years almost eight‐fold higher that in women aged 60 to 64 years (Hernlund 2013). The same study estimated that the direct costs associated with a new osteoporotic vertebral fracture in the first year after its occurrence is about 6490 Euros, signifying that these fractures are costly. A Swedish study estimated that the lifetime risk for a symptomatic osteoporotic vertebral fracture for a person of the age of 45 is 15% for a woman and 8% for a man (Kanis 2000). In the USA, approximately 750,000 new osteoporotic vertebral fractures occur each year (Melton 1997).

A recent population‐based study examining trends in fracture incidence over time in Olmstead County, Minnesota, observed a dramatic increase in the incidence of vertebral fractures, from 1989 to 1991 to 2009 to 2011, and this was associated with an apparent earlier onset of vertebral fracture over time (Amin 2014). The vast majority of these (83.4%) were considered osteoporotic, defined in the study as resulting from no more than moderate trauma (by convention, equivalent to a fall from standing height or less). While some of the observed increase could have been partially attributable to incidentally diagnosed vertebral fractures, the findings are in keeping with a Dutch study that observed a rise in the number of emergency department visits due to osteoporotic vertebral fractures between 1986 and 2008, due to an increase in falls among the most elderly (Oudshoorn 2012). The results are also consistent with a Canadian study that observed a decline in the rate of all low‐trauma osteoporotic fractures over 20 years from 1986 to 2006 in the Province of Manitoba, except for vertebral fractures, which did not decline significantly in either sex (Leslie 2011).

Osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures are a common cause of both acute and chronic back pain in older populations, although only about a third of radiographic osteoporotic vertebral compression deformities present with acute pain. Both symptomatic and asymptomatic osteoporotic vertebral fractures can lead to substantial spinal deformity, functional limitation, pulmonary compromise and lowered quality of life. They are associated with an increased risk of further vertebral fractures and increased mortality (Lau 2008).

Management options for treating acutely painful osteoporotic vertebral fractures are limited and include provision of adequate analgesia, bed rest and physical therapy, as well as assessment and appropriate management of osteoporosis and risk factors for further fractures such as falls prevention. While most fractures generally heal within a few months, some people have persistent pain and disability, and require hospitalisation, long‐term care, or both (Kanis 1999).

Description of the intervention

Percutaneous vertebroplasty was first described in 1987 as a treatment for vertebral angioma (Galibert 1987), and subsequently it has been used to treat both benign and malignant vertebral fractures. The procedure may be performed under intravenous sedation or general anaesthesia by interventional radiologists, neurosurgeons or orthopaedic surgeons. Under imaging guidance, most often fluoroscopy, a large calibre needle is inserted into the affected vertebral body usually via a transpedicular route and bone cement, usually polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA), is injected (Hide 2004).

Early open‐label, and uncontrolled studies consistently reported dramatic immediate improvements in pain, and adverse events were reportedly uncommon (Hochmuth 2006). Despite the absence of evidence from high‐quality randomised controlled trials (RCTs) confirming its benefits, over the last 20 years the procedure has become incorporated into standard care in many parts of the world, most commonly reserved for patients who fail a period of conservative therapy. In the USA, dramatic increases in the use of vertebroplasty have been observed over the last two decades (Gray 2007a; Lad 2009; Leake 2011).

Documented adverse events occurring either during or after the procedure have included cord compression due to extension of the cement outside of the vertebral body, cement pulmonary embolism, infection, rib fractures and new adjacent or non‐adjacent vertebral fractures, osteolysis in the bone surrounding the injected material and death (Leake 2011).

How the intervention might work

The mechanism by which percutaneous vertebroplasty is purported to reduce pain is not known. At least three possible mechanisms have been proposed: (1) mechanical stabilisation of the fractured bone; (2) thermal destruction of nerve endings due to the high temperature reached during polymerisation of the injected cement; and (3) chemical destruction of the nerve endings due to the chemical composition of the cement (Belkoff 2001). The semisolid mixture of PMMA has been shown to restore strength and stiffness of vertebral bodies in post‐mortem studies (Belkoff 2001).

Why it is important to do this review

Percutaneous vertebroplasty has been widely adopted into clinical practice to treat painful osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures prior to supporting evidence of its efficacy and safety from high‐quality RCTs. The first RCT of vertebroplasty compared with usual care was published in 2007 (Voormolen 2007), while the first two placebo‐controlled trials were published in 2009 (Buchbinder 2009; Kallmes 2009).

Numerous systematic reviews and/or meta‐analyses of vertebroplasty for osteoporotic spinal fractures have been published (Anderson 2013; Bliemel 2012; Eck 2008; Gill 2007; Han 2011; Hochmuth 2006; Hulme 2006; Lee 2009; Liu 2013; Ma 2012; McGirt 2009; Papanastassiou 2012; Ploeg 2006; Robinson 2012; Shi 2012; Stevenson 2014; Taylor 2006; Trout 2006; Wang 2012; Xing 2013; Zhang 2013; Zou 2012). These have varied in inclusion criteria and methodologic rigour, and have reported conflicting results.

In 2015, we published a Cochrane systematic review that synthesised the best available evidence for the efficacy and safety of this procedure including 11 RCTs and one quasi‐RCT (1320 participants) (Buchbinder 2015). Based upon moderate‐quality evidence, our review did not support a role for vertebroplasty for treating osteoporotic vertebral fractures in routine practice. Since then the results of further trials have been published and/or presented including two additional placebo‐controlled trials. It is important to determine whether or not incorporation of the findings of the additional trials in an updated review alters our previous conclusions.

Objectives

To assess the benefits and harms of percutaneous vertebroplasty for treating patients with osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of any design (e.g. parallel, cross‐over, factorial) and controlled clinical trials using a quasi‐randomised method of allocation, such as by alternation or date of birth. Reports of trials were eligible regardless of the language or date of publication. Only trials published as full articles or available as a full trial report were considered for inclusion.

Types of participants

We included trials that enrolled adults with a diagnosis of osteoporotic vertebral compression fracture/s of any duration. The diagnosis of osteoporosis could have been based upon bone mineral densitometry or explicit clinical diagnostic criteria as defined by the studies. Trials enrolling participants with vertebral fractures due to another cause such as major trauma and malignancy were excluded.

Types of interventions

We included trials that evaluated percutaneous vertebroplasty, defined as percutaneous injection of bone cement (usually polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA)) or similar substances into a vertebral body under imaging guidance.

Comparators could be any of the following.

Placebo or sham procedure

Usual care (best supportive care)

Balloon kyphoplasty (similar to a percutaneous vertebroplasty, but prior to injection of bone cement a balloon is inserted into the vertebral body and expanded), or other similar procedures

Pharmacologic treatment (e.g. calcitonin, bisphosphonates, complementary medicine)

Non‐pharmacologic interventions (e.g. bracing, physical therapy or surgery)

Types of outcome measures

Major outcomes

The following outcomes were selected as the most important.

Mean overall pain measured on a visual analogue scale (VAS) or numerical rating scale (NRS)

Disability measured by the Roland‐Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ) or other back‐specific disability measure

Vertebral fracture and/or osteoporosis‐specific health‐related quality of life, e.g. the Quality of Life Questionnaire of the European Foundation for Osteoporosis (QUALEFFO)

Overall health‐related quality of life, e.g. European Quality of Life with 5 Dimensions (EQ‐5D) or Assessment of Quality of Life (AQoL) questionnaire

Treatment success measured by a participant‐reported global impression of clinical change (much or very much improved), or similar measure

New (incident) symptomatic vertebral fractures (the denominator was the number of participants, but the numerator could include more than one new fracture per participant)

Number of serious other adverse events judged to be due to the procedure (e.g. infection, clinical complications arising from cement leakage)

Minor outcomes

Proportion of participants with pain improved by a clinically relevant amount, for example improvement of at least 2.5 units or 30% on a zero or one to 10 scale

New (incident) radiographic vertebral fractures (the denominator was the number of participants, but the numerator could include more than one new fracture per participant)

Other adverse events

Timing of outcome assessment

We extracted outcome measures that assessed benefits of treatment (e.g. pain or function) at the following time points:

one to two weeks;

one month;

two to three months;

six months;

12 months;

24 months.

If data were available in a trial at multiple time points within each of the above periods (e.g. at one and two weeks), we only extracted data at the latest possible time point of each period. We extracted new vertebral fractures at 12 and 24 months, where available. We extracted other adverse events at all time points.

We collated the main results of the review into a 'Summary of findings' table which provides key information concerning the quality of evidence and the magnitude and precision of the effect of the interventions. We included the major outcomes (see above) in the 'Summary of findings' table at one month for outcomes assessing potential benefits of treatment (pain, disability, vertebral fracture and/or osteoporosis and overall quality of life and treatment success), 12 months for new symptomatic vertebral fractures (the most data available), and one month for serious other adverse events (judged to be related to the procedure).

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following databases on 15 November 2017; updated from the search in the earlier version of this review, which was conducted on 12 November 2014.

The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (via the Cochane Library to Issue 11 of 12, 2017)

MEDLINE (via Ovid from January 2014 to 15 November 2017)

Embase (via Ovid from January 2014 to 15 November 2017)

The search strategies are shown in Appendix 1; Appendix 2; Appendix 3).

We also searched for ongoing trials and protocols of published trials in the clinical trials register that is maintained by the US National Institute of Health (http://clinicaltrials.gov) and the Clinical Trial Register at the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform of the World Health Organization (http://www.who.int/ictrp/en/) on 18 November 2017 (see Appendix 4).

No language restrictions were applied.

Searching other resources

We also reviewed the reference lists of the included trials and any relevant review articles retrieved from the electronic searches, to identify any other potentially relevant trials.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (SD and RO (for previous version of the review) or RB and RJ or KR and RJ) independently selected trials for possible inclusion against a predetermined checklist of inclusion criteria (see Criteria for considering studies for this review). We screened titles and abstracts and initially categorised studies into the following groups:

possibly relevant ‐ studies that met the inclusion criteria and studies from which it was not possible to determine whether they met the criteria either from their title or abstract;

excluded ‐ those clearly not meeting the inclusion criteria.

If a title or abstract suggested that the study was eligible for inclusion, or we could not tell, we obtained a full‐text version of the article and two review authors independently assessed it to determine whether it met the inclusion criteria. The review authors resolved discrepancies through discussion or adjudication by a third author.

Data extraction and management

At least two review authors in various combinations (JH, AJ, RJ, KR) independently extracted data using a standard data extraction form developed for this review. The authors resolved any discrepancies through discussion or adjudication by a third author (RB). For each included study we recorded the following:

trial characteristics, including type (e.g. parallel or cross‐over), country, source of funding, and trial registration status (with registration number recorded if available);

participant characteristics, including age, sex, duration of symptoms, and inclusion/exclusion criteria;

intervention characteristics for each treatment group, and use of co‐interventions;

outcomes reported, including the measurement instrument used and timing of outcome assessment.

Five review authors (JH, AJ, RB, RJ and KR) in various combinations independently extracted all outcome data.

For a particular systematic review outcome there may be a multiplicity of results available in the trial reports (e.g. multiple scales, time points and analyses). To prevent selective inclusion of data based on the results, we used the following a priori defined decision rules to select data from trials.

Where trialists reported both final values and change from baseline values for the same outcome, we extracted final values.

Where trialists reported both unadjusted and adjusted values for the same outcome, we extracted unadjusted values.

Where trialists reported data analysed based on the intention‐to‐treat (ITT) sample and another sample (e.g. per‐protocol, as‐treated), we extracted ITT‐analysed data.

For cross‐over RCTs, we preferentially extracted data from the first period only.

Where trials did not include a measure of overall pain but included one or more other measures of pain, for the purpose of combining data for the primary analysis of overall pain, we planned to combine overall pain with other types of pain in the following hierarchy: unspecified pain; pain with activity; or daytime pain. For trials that included more than one back‐specific measure of disability we preferentially extracted data for the RMDQ if reported.

Review authors who were also authors of relevant trials had no involvement in determining whether or not their trials met the inclusion criteria for this review, and also had no involvement in data extraction or 'Risk of bias' assessment of their own trials.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

At least two review authors (JH, AJ, RJ, KR) in various combinations independently assessed the risk of selection, performance, detection, attrition and reporting biases for all included RCTs by evaluating the following domains: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants, care provider, and outcome assessor for each outcome measure, incomplete outcome data and other biases, conforming to the methods recommended by Cochrane (Higgins 2011).

Each criterion was rated as low risk of bias, high risk of bias or unclear risk (either lack of information or uncertainty over the potential for bias). Disagreements among the review authors were discussed and resolved.

Measures of treatment effect

We used Cochrane's statistical software, Review Manager 5.3, to perform data analysis. We expressed dichotomous outcomes as risk ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and continuous outcomes as mean differences (MDs) with 95% CIs if different trials used the same measurement instrument to measure the same outcome. Alternatively, we analysed continuous outcomes using the standardised mean difference (SMD) when trials measured the same outcome but employed different measurement instruments to measure the same conceptual outcome (e.g. disability).

To enhance interpretability of continuous outcomes, pooled SMDs of disability were back‐transformed to an original zero to 23 scale RMDQ, by multiplying the SMD and 95% CIs by a representative pooled standard deviation (SD) at baseline of the trial with the highest weight in the meta‐analysis and the least susceptibility to bias (Schünemann 2011b). We assumed VAS and NRS were comparable scales, and combined them in a meta‐analysis using the MD statistic (Bijur 2003; Birnbaumer 2003).

For studies comparing vertebroplasty with placebo, we used SD 2.9 for RMDQ (Buchbinder 2009).

For analyses comparing vertebroplasty with usual care that included Farrokhi 2011,

we used SMD for pain as (Farrokhi 2011 used a one to 10 pain scale in comparison to all other trials that used a zero to 10 pain scale), but back‐transformed the SMD to MD on a zero to 10 scale by multiplying the SMD and 95% CIs by the SD of pain at baseline from the control group of the Klazen 2010 trial (SD 1.6). For disability (vertebroplasty versus usual care), which included data for the RMDQ and Oswestry Disability Index (ODI), we back‐transformed the SMD to MD on the RMDQ (zero to 23 scale) by multiplying the SMD and 95% CIs by the SD of disability at baseline also from the control group of the Klazen 2010 trial (SD 4.2).

For analyses comparing vertebroplasty with kyphoplasty that included Evans 2015, we used SMD for disability (as Evans 2015 used the RMDQ compared to all other trials that used ODI), but back‐transformed the SMD to MD on the RMDQ (zero to 23 scale) by multiplying the SMD and 95% CIs by the standard deviation (SD) of pain at baseline from the control group of the Evans 2015 trial (SD 6.6).

Unit of analysis issues

The unit of analysis was the participant, rather than the number of fractures treated. For studies containing more than two intervention groups, making multiple pair‐wise comparisons between all possible pairs of intervention groups possible, we planned to include the same group of participants only once in the meta‐analysis.

Dealing with missing data

Where important data were missing or incomplete, we sought further information from the trial authors.

In cases where individuals were missing from the reported results, we assumed the missing values to have a poor outcome. For dichotomous outcomes that measured serious and other adverse events (e.g. incident fractures), we calculated the adverse event rate using the number of patients that received treatment as the denominator (worst‐case analysis). For dichotomous outcomes that measured benefits (e.g. proportion of participants reporting pain relief of 30% or greater), we calculated the worst‐case analysis using the number of randomised participants as the denominator. For continuous outcomes (e.g. pain), we calculated the MD or SMD based on the number of patients analysed at that time point. If the number of patients analysed was not presented for each time point, we used the number of randomised patients in each group at baseline.

For continuous outcomes with no SD reported, we calculated SDs from standard errors (SEs), 95% CIs or P values. If no measures of variation were reported and SDs could not be calculated, we planned to impute SDs from other trials in the same meta‐analysis, using the median of the other SDs available (Ebrahim 2013). For continuous outcomes presented only graphically, we extracted the mean and 95% CIs from the graphs using plotdigitizer (http://plotdigitizer.sourceforge.net/). For dichotomous outcomes, we used percentages to estimate the number of events or the number of people assessed for an outcome.

Where data were imputed or calculated (e.g. SDs calculated from SEs, 95% CIs or P values, or imputed from graphs or from SDs in other trials), we reported this in the Characteristics of included studies tables.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed clinical heterogeneity by determining whether the characteristics of participants, interventions, outcome measures and timing of outcome measurement were similar across trials.

We assessed statistical heterogeneity by visually assessing the scatter of effect estimates on the forest plots, and by using the Chi2 statistic and the I2 statistic (Higgins 2003). We interpreted the I2 statistic using the following as an approximate guide:

0% to 40% may not be important heterogeneity;

30% to 60% may represent moderate heterogeneity;

50% to 90% may represent substantial heterogeneity;

75% to 100% may represent considerable heterogeneity (Deeks 2011).

In cases of considerable heterogeneity, we intended to explore the data further by comparing the characteristics of individual studies and any subgroup analyses.

Assessment of reporting biases

To assess publication bias, we planned to generate funnel plots if at least 10 trials examining the same intervention comparison were included in the review, and comment on whether any asymmetry in the funnel plot was due to publication bias, or methodological or clinical heterogeneity of the trials (Sterne 2011).

To assess for potential small‐study effects in meta‐analyses (i.e. the intervention effect is more beneficial in smaller studies), we planned to compare effect estimates derived from a random‐effects model and a fixed‐effect model of meta‐analysis. In the presence of small‐study effects, the random‐effects model will give a more beneficial estimate of the intervention than the fixed‐effect estimate (Sterne 2011). However, as no statistically significant results were found, we could not perform this analysis.

To assess outcome reporting bias, we compared the outcomes specified in trial protocols with the outcomes reported in the corresponding trial publications.

Data synthesis

Included studies were grouped based on whether percutaneous vertebroplasty was compared with a placebo or sham procedure, usual care or another active intervention.

For benefit, we considered the first comparison, vertebroplasty versus placebo, to be the least prone to bias and it was therefore the primary comparison for addressing the objectives of this review.

For safety (new vertebral fractures and other serious and other adverse events), as the results were similar for both placebo and usual care comparisons, to simplify the presentation we presented safety data in the same analyses.

We combined results of trials with similar characteristics (participants, interventions, outcome measures and timing of outcome measurement) to provide estimates of benefits and harms. To combine results we used a random‐effects meta‐analysis model based on the assumption that clinical and methodological heterogeneity was likely to exist and to have an impact on the results.

'Summary of findings' table

We presented the major outcomes for the primary comparison of vertebroplasty of the review in a 'Summary of findings' table (mean pain, disability, disease‐specific quality of life, overall quality of life, treatment success, incident fractures, and total number of serious adverse events). This table reports the quality of evidence, the magnitude of effect of the interventions examined, and the sum of available data for each major outcome as recommended by Cochrane (Schünemann 2011a), and was produced using GRADEpro software. The overall quality of the evidence was graded for each of the major outcomes using the GRADE approach (Schünemann 2011b). We included evidence only from trials with adequate treatment allocation concealment and blinding of participants and outcome assessment.

In the comments column, we calculated the absolute percentage change and the relative percentage change. Relative changes were calculated as absolute change (MD) divided by mean at baseline in the placebo group from Buchbinder 2009 (values were: 7.1 points on zero‐ to 10‐point VAS pain; 17.3 points on zero‐ to 23‐point Roland‐Morris Disability questionnaire; 0.28 points on EQ‐5D quality of life scale; 59.6 points on the QUALEFFO scale). In interpreting results, we assumed a minimal clinically important difference of 1.5 points on a 10‐point pain scale (Grotle 2004); two to three points on the zero‐ to 23‐point RMDQ (Trout 2005), 10 points on the zero to 100 QUALEFFO scale (Lips 1999), and 0.074 points on the EQ‐5D quality of life scale, zero = death to one = perfect health (Walters 2005).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Where sufficient data were available, the following subgroup analysis was performed.

Duration of symptoms ('acute' fractures versus 'subacute fractures')

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analyses were performed to investigate the robustness of the treatment effect (of main outcomes) by performing an analysis that included all trials combined, i.e. trials with placebo or usual care comparator groups, to see if inclusion of trials that did not blind participants changed the overall treatment effect.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

We updated the search for the current review on 15 November 2017, searching for studies published since 2014 (the date of the search in the first version of the review).

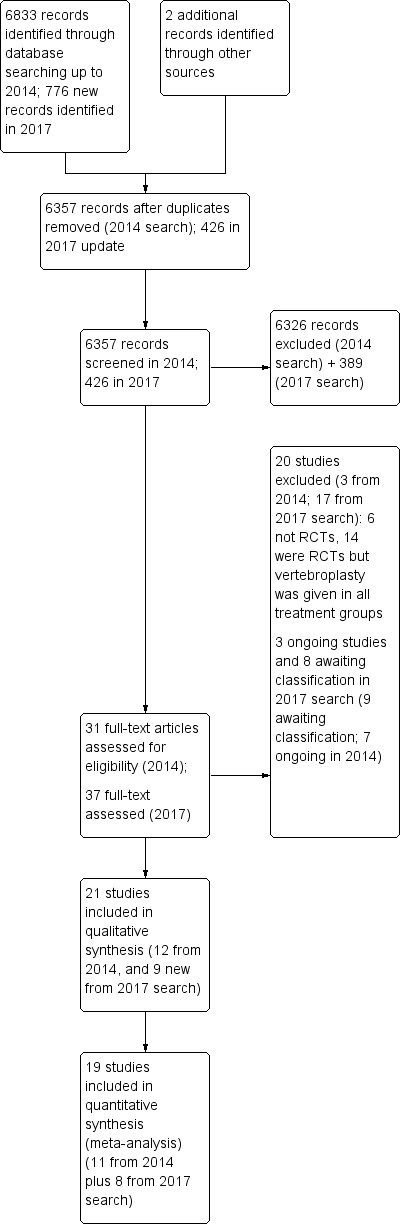

The results of the search are presented in Figure 1. The updated search strategy identified 776 new citations (426 after de‐duplication). Of these, 37 were assessed in full text and nine new studies were included (Clark 2016; Evans 2015; Leali 2016; Sun 2016; Firanescu 2018; VOPE 2015; Wang 2015; Wang 2016; Yang 2016). Six of these were identified as ongoing or completed studies in the 2015 version of this review and have since reported results (Clark 2016; Evans 2015; VOPE 2015; Firanescu 2018; Wang 2015), (Firanescu 2018), and are included in this review update. The partially reported results of Firanescu 2018 were presented at a conference, and were identified in the last full search (15 November 2017). The results of the trial were published subsequent to the search and were available on 9 May 2018; thus we included information from this publication as a minor amendment to the review.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Thus, in total in this update we included 21 trials (Blasco 2012; Buchbinder 2009; Chen 2014a; Clark 2016; Dohm 2014; Endres 2012; Evans 2015; Farrokhi 2011; Kallmes 2009; Klazen 2010; Leali 2016; Liu 2010; Rousing 2009; Sun 2016; Firanescu 2018; Vogl 2013; Voormolen 2007; VOPE 2015; Wang 2015; Wang 2016; Yang 2016).

Ten randomised controlled trials (RCTs) were registered in a trial registry (Blasco 2012; Buchbinder 2009; Clark 2016; Dohm 2014; Evans 2015; Farrokhi 2011; Kallmes 2009; Klazen 2010; Firanescu 2018; VOPE 2015), although one was registered retrospectively (Farrokhi 2011). One RCT reports that it is registered on clinicaltrials.gov (NCT00576546) (Vogl 2013), but this could not be verified. No trial registration was found for the other trials (Chen 2014a; Endres 2012; Leali 2016; Liu 2010; Rousing 2009; Sun 2016; Voormolen 2007; Wang 2015; Wang 2016; Yang 2016).

In total, 20 studies were excluded after full‐text assessment (see table of Characteristics of excluded studies): 17 studies identified in the updated search were excluded (Cai 2015; Chen 2014b; Chun‐lei 2015; Du 2014; Gu 2015; Li 2015a; Liu 2015; Min 2015; Son 2014; Xiao‐nan 2014; Yang 2014; Yi 2016; Ying 2017; Yokoyama 2016; Zhang 2015a; Zhang 2015b; Zhang 2015c), in addition to the three studies excluded in the earlier version of this review (Gilula 2013; Huang 2014; Yi 2014).

Three trials are classified as ongoing, although it is unclear if the trials are completed. We could not find any trial registration details for one study (Longo 2010), while a second trial is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov with an expected completion date of December 2014 (Sun 2012), but the current recruitment status is unknown. The third trial (VERTOS V), was recorded as completed in June 2015 at clinicaltrials.gov, but the trialists subsequently altered the recruitment status in January 2017 to state that the study is now 'enrolling by invitation', with a new estimated completion date of July 2018 (see table of Characteristics of ongoing studies).

Based upon a search of trial registries, we identified an additional four registered RCTs that are reported to have been completed but we were unable to find results (Dolin 2003; Laredo (OSTEO‐6); Laredo (STIC2); Sorensen 2005) (see table of Characteristics of studies awaiting classification). We also identified four completed RCTs that likely meet inclusion criteria of the review, but results are published in Chinese and we did not translate these prior to publication of this review update: two trials compare vertebroplasty with kyphoplasty (Tan 2016; Zhou 2015), another compared vertebroplasty with kyphoplasty and bone‐filling mesh container (Li 2015b) and the third vertebroplasty with usual care (Chen 2015).

Since the last version of the review, we have removed three ongoing trials (Damaskinos 2015 NCT02489825; Nieuwenhuijse 2012 NTR3282); and Zhao 2014 ChiCTR‐TRC‐14004835), as percutaneous vertebroplasty was given to participants in both treatment arms and thus, when trial results become available, they will not be eligible for inclusion in this review. An additional trial that was reportedly suspended due to difficulty recruiting participants prior to completion and which was included as a study awaiting classification in the last version of the review (Nakstad 2008 NCT00635297) has also been removed from this current version of the review as if the trial had been completed it would not be eligible for inclusion.

Detailed descriptions of all unpublished trials that are either completed, suspended or ongoing are provided in either the table of Characteristics of studies awaiting classification or table of Characteristics of ongoing studies and a summary of all unpublished trials is provided in Table 2.

1. Study characteristics of unpublished, ongoing and suspended or terminated trials.

| Trial registration number | Principle Investigator/s and Country | Comparator/s | Main selection criteria | Registration date | Recruitment commenced | Status 8 January 2018 | Planned sample size | Final sample size |

|

NCT00749060 ‘OSTEO‐6’ |

Laredo JD France |

Kyphoplasty; Usual care with or without brace | Age ≥ 50 years Fracture < 6 weeks |

8 Sept 2008 | Dec 2007 | Completed June 2012; results unpublished | 300 | 48 |

|

NCT00749086 ‘STIC2’ |

Laredo JD France |

Kyphoplasty | Age ≥ 50 years Fracture > 6 weeks |

8 Sept 2008 | Dec 2007 | Completed June 2012; results unpublished | 200 | 97 |

| NCT00203554 | Sorensen L Denmark |

Usual care | Fracture < 6 months | 16/09/2005 | Mar 2004 | Completed Jan 2008; results unpublished | 27 | 27 |

| ISRCTN14442024 (Also N0213112414) |

Dolin, S UK |

Usual care | Fracture > 4 weeks | 12 Sep 2003 | Nov 28 2005 | Completed (last updated 6 Feb 2014); results unpublished | Not provided | Not provided |

| NCT01677806 | Sun G China |

Usual care | Age ≥ 50 years Fracture < 6 weeks |

23 Aug 2012 | Oct 2012 | Recruitment status unknown (last updated 11 Sep 2014) | 114 | ‐ |

| Registration details not found. | Longo UG Italy |

3 weeks bed rest, rigid hyperextension corset, followed by 2‐3 months in a Cheneau brace (called ‘double‐blind) | Age ≥ 50 years | Trial registration not found | Unknown | Unknown (protocol published) | 200 | ‐ |

|

NCT01963039 ‘VERTOS V’ |

Carli D the Netherlands |

Sham | Age ≥ 50 years Fracture ≥ 12 weeks |

28 Aug 2013 | May 2013 | Previously reported as completed (Nov 2015) then recruiting again (Feb 2017) (protocol published) | 94 | ‐ |

| Record of trial registration not found | Chen JP China |

Usual care | Not available | Trial registration not found | Unknown | Completed; study awaiting translation | Unknown | 84 |

| Record of trial registration not found | Li DH China |

Kyphoplasty Bone filling mesh container |

Not available | Trial registration not found | Unknown | Completed; study awaiting translation | Unknown | 90 |

| Record of trial registration not found | Tan B China |

Kyphoplasty | Not available | Trial registration not found | Unknown | Completed; study awaiting translation | Unknown | 106 |

| Record of trial registration not found | Zhou W China |

Kyphoplasty | Not available | Trial registration not found | Unknown | Completed; study awaiting translation | Unknown | 80 |

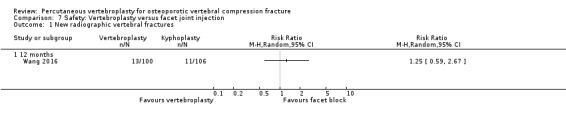

* Abstract reported that analysis favoured vertebroplasty at 1 day and 1 week for pain, and disability measured by RMDQ and ODI (data not provided), but no evidence of important differences between groups at 1, 3, 6, 12 months for pain, RMDQ, ODI and SF‐36 function and SF‐36 physical and mental component scores. After 12 months follow‐up, there were 13 new fractures in the percutaneous vertebroplasty group and 11 new fractures in the facet joint block group. Abstract did not report method of randomisation, whether or not treatment allocation was concealed and whether or not participants and investigators were blinded to treatment allocation.

Included studies

A full description of all included trials is provided in the table of Characteristics of included studies and a summary of trial and participant characteristics is provided in Table 3.

2. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the trial participants.

| Study | Country | Treatment Groups | Mean age, yrs | Mean symptom duration | Mean (SD) baseline pain (0‐10 scale$) | Mean (SD) baseline RMDQ+ (0‐24 scale†) | Mean (SD) baseline QUALEFFO (0‐100 scale) | Procedures performed by | Mean (range) volume cement injected (mL) | Follow‐up |

| Blasco 2012 | Spain | Vertebroplasty | 71.3 | 140.3 days | 7.2 (0.3) | ‐ | 65.2 (2.2) | Interventional radiologists | Not specified | 2 weeks, 2, 6, 12 months |

| Usual care | 71.3 | 143.1 days | 6.3 (0.4) | ‐ | 59.2 (2.2) | |||||

| Buchbinder 2009 | Australia | Vertebroplasty | 74.2 | 9 weeks^ | 7.4 (2.1) | 17.3 (2.8) | 56.9 (13.4) | Interventional radiologists | 2.8 (1.2 ‐ 5.5) | 1 week, 1, 3, 6, 12, 24 months |

| Placebo | 78.9 | 9.5 weeks^ | 7.1 (2.3) | 17.3 (2.9) | 59.6 (17.1) | |||||

| Clark 2016 | Australia | Vertebroplasty | 80 | 2.8 weeks | 8.1 (1.8) | 19.5 (3.5) | 65.4 (11.4) | Interventional radiologists | 7.5 (4.7 ‐ 10.3) | 3 days, 14 days, 1, 3 and 6 months |

| Placebo | 81 | 2.4 weeks | 8.2 (1.5) | 19.8 (3.7) | 67.7 (11.2) | |||||

| Chen 2014a | China | Vertebroplasty | 64.6 | 31 weeks | 6.5 (0.9)& | 18.6 (1.8)#& | ‐ | Orthopaedic surgeons | 3.6 (3 ‐ 6) | 1 day, 1 week, 1, 3, 6, 12 months |

| Usual care and brace | 66.5 | 29.5 weeks | 6.4 (0.9)& | 16.7 (1.3)#& | ‐ | |||||

| Dohm 2014 | USA and Canada | Vertebroplasty | 75.7 | ‐¤ | ˜7.6µ | ‐ | ‐ | Interventional radiologists and neuroradiologists, orthopaedic surgeons, neuroradiologists | 4.0 (3.0 to 6.0)¢ | 7 days, 1, 3, 12 and 24 months |

| Balloon kyphoplasty | 75.5 | ‐¤ | ˜7.6µ | ‐ | ‐ | Not stated | 4.6 (3.4 to 6.0)¢ | |||

| Endres 2012 | Germany | Vertebroplasty | 71.3 | ‐§ | 7.8 (0.9) | ‐ | ‐ | Orthopaedic surgeon | 3.1 (2 – 4) | Immediately, mean 5.8 months (range: 4 to 7) |

| Balloon kyphoplasty | 63.3 | ‐§ | 9.0 (0.7) | ‐ | ‐ | Orthopaedic surgeon | 3.9 (3 – 5) | |||

| Shield kyphoplasty | 67.1 | ‐§ | 8.8 (1.5) | ‐ | ‐ | Orthopaedic surgeon | 4.6 (3 – 6) | |||

| Evans 2015 | USA | Vertebroplasty | 76.1 | ‐ | 7.9 (2.0) | 16.3 (7.4) | ‐ | Not reported | Not reported | 3 days, 1, 6 and 12 months |

| Kyphoplasty | 75.1 | ‐ | 7.4 (1.9) | 17.3 (6.6) | ‐ | Not reported | Not reported | |||

| Farrokhi 2011 | Iran | Vertebroplasty | 72 | 27 weeks | 8.4 (1.6) | ‐ | ‐ | Neurosurgeons | 3.5 (1 ‐ 5.5) | 1 week, 2, 6, 12, 24, 36 months |

| Usual care | 74 | 30 weeks | 7.2 (1.7) | ‐ | ‐ | |||||

| Firanescu 2018 | the Netherlands | Vertebroplasty | 74.7 | 29.2 days | 7.7 (1.4) | 18 (4.5) | 68.4 (17.1) | Interventional radiologists | 5.11 (1 ‐ 11) | 1 day, 1 week, 1, 3, 6, 12 months |

| Placebo | 76.8 | 25.9 days | 7.9 (1.6) | 17.8 (4.7) | 69.7 (17.9) | |||||

| Kallmes 2009 | US, UK, Australia | Vertebroplasty | 73.4 | 16 weeks | 6.9 (2.0) | 16.6 (3.8) | ‐ | Interventional radiologists | 2.8 (1 ‐ 5.5)* | 3 days, 2 weeks, 1 month |

| Placebo | 73.3 | 20 weeks | 7.2 (2.0) | 17.5 (4.1) | ‐ | |||||

| Klazen 2010 | the Netherlands, Belgium | Vertebroplasty | 75.2 | 29.3 days | 7.8 (1.5) | 18.6 (3.6)# | 58.7 (13.5) | Interventional radiologists | 4.1 (1 ‐ 9) | 1 day, 1 week, 1, 3, 6, 12 months |

| Usual care | 75.4 | 26.8 days | 7.5 (1.6) | 17.2 (4.2)# | 54.7 (14.4) | |||||

| Leali 2016 | Italy | Vertebroplasty | ‐ | ‐§ | 4.8 (‐) | 53.6 (‐) | ‐ | Not reported | 4 (‐) | 1 and 2 days, 6 weeks, 3 and 6 months |

| Usual care | ‐ | ‐§ | ‐§ | ‐ | ‐ | Not reported | ||||

| Liu 2010 | Taiwan | Vertebroplasty | 74.3 | 15.8 days | 7.9 (0.7) | ‐ | ‐ | Not reported | 4.9 (0.7) | 3 days, 6 months, 1, 3 and 5 years |

| Balloon kyphoplasty | 72.3 | 17.0 days | 8.0 (0.8) | ‐ | ‐ | Not reported | 5.6 (0.6) | |||

| Rousing 2009 | Denmark | Vertebroplasty | 80 | 8.4 days | 7.5 (2.0) | ‐ | ‐ | Orthopaedic surgeons | Not reported | 3 months |

| Usual care and brace | 80 | 6.7 days | 8.8 (1.2) | ‐ | ‐ | |||||

| Sun 2016 | China | Vertebroplasty | 65.4 | ‐ | 8.5 (1.1) | 70.6 (8.6)× | ‐ | Not reported | 3.4 (0.3) | 2 days, 12 months |

| Kyphoplasty | 65.2 | ‐ | 8.2 (0.9) | 71.7(8.5)× | ‐ | Not reported | 4.2 (0.2) | |||

| Vogl 2013 | Germany and USA | Vertebroplasty | 74 | ‐¥ | 8.5 (1.2) | ‐ | ‐ | Not reported | 4.0 (1.1) | 1 day, 3 and 12 months |

| Shield kyphoplasty | 80 | ‐¥ | 8.3 (1.1) | ‐ | ‐ | Not reported | 3.8 (0.7) | |||

| Voormolen 2007 | the Netherlands | Vertebroplasty | 72 | 85 days | 7.1 (5 ‐ 9)+ | 15.7 (8‐24) | 60.0 (37 to 86) | Interventional radiologists | 3.2 (1.0 ‐ 5.0) | 2 weeks |

| Usual care | 74 | 76 days | 7.6 (5‐10) | 17.8 (8‐22) | 60.7 (38 to 86) | |||||

| VOPE 2015 | Denmark | Vertebroplasty | 70.6 | ‐ª | 7.47 () | ‐ | ‐ | Orthopaedic surgeons | Not reported˜ | 6 hours, weekly to 3 months, 12 months |

| Placebo (lidocaine injected) | 69.3 | ‐ª | 7.61 () | ‐ | ‐ | Orthopaedic surgeons | ||||

| Wang 2015 | China | Vertebroplasty | 69.43 | ‐ | 8.1 (1.2) | 71.22 (10.56)× | ‐ | Not reported | 3.31 (0.77) | 1 day, 3 and 12 months |

| Balloon kyphoplasty | 68.63 | ‐ | 8.0 (1.1) | 71.30 (10.22)× | ‐ | Not reported | 4.22 (1.29) | |||

| Wang 2016 | China | Vertebroplasty | 63.7 | ‐ª | 7.65 (1.11) | 18.3 (1.0) | ‐ | Spine surgeon | 5.5 (3.0 ‐ 9.0) | |

| Facet joint injection | 62.6 | ‐ª | 7.76 (1.06) | 18.45 (0.98) | ‐ | Spine surgeon | ||||

| Yang 2016 | China | Vertebroplasty | 77.1 | Not reported | 7.5 (1.1) | 80.2 (9.9)× | 78.1 (8.1) | Not stated | 4.5 (3‐6.5) | 1 week, 3, 6 and 12 months |

| Usual care | 76.2 | Not reported | 7.7 (1.1) | 81.5 (9.7)× | 77.5 (8.6) |

$1‐10 point scale used by Farrokhi 2011, 0 to 100 scale used by VOPE 2015 and we report pain with forward bending for this trial as overall pain not reported and have converted SE to SD; +RMDQ: Roland‐Morris Disability Questionnaire; †modified RMDQ (0‐23 scale) used by Buchbinder 2009, Kallmes 2009 and Firanescu 2018; ×Oswestry Disability Index (0 to 100) used by Leali 2016, Wang 2015, Yang 2016; ^ median duration of symptoms; ¤Not reported but symptom duration 6 months or less; µMean symptom duration reported graphically only; ¢Median and interquartile range;§Not reported but symptom duration 6 weeks or less; ªNot reported but symptom duration 8 weeks or less; &Data only included for the 42/46 in VP group and 43/50 in the usual care group who completed 12‐month follow‐up in groups assigned to at baseline; #Disability significantly higher in the vertebroplasty group; *from n = 20 treated at Mayo (personal communication); ¥Not reported but at least 6 weeks of conservative treatment; +Only range provided; ˜up to 2 mL.

Trial design, setting and characteristics

Five trials compared vertebroplasty with a placebo (a sham vertebroplasty procedure) (Buchbinder 2009; Clark 2016; Kallmes 2009; Firanescu 2018; VOPE 2015), eight trials compared vertebroplasty with usual care/optimum pain management (Blasco 2012; Chen 2014a; Farrokhi 2011; Klazen 2010; Leali 2016; Rousing 2009; Voormolen 2007; Yang 2016), one trial compared vertebroplasty with injection of local anaesthetic and glucocorticosteroid into the facet joint of the fractured vertebra in the spine (facet joint injection) (Wang 2016), while seven trials compared vertebroplasty with different kyphoplasty techniques (Dohm 2014; Endres 2012; Evans 2015; Liu 2010; Sun 2016; Vogl 2013; Wang 2015).

Trials were conducted in 15 different countries including: Australia (Buchbinder 2009; Clark 2016), USA (Evans 2015), USA, Australia and UK (Kallmes 2009), the Netherlands (Firanescu 2018; Voormolen 2007), the Netherlands and Belgium Klazen 2010), Denmark (Rousing 2009; VOPE 2015), Iran (Farrokhi 2011), Italy, France and Switzerland (Leali 2016), Spain (Blasco 2012), China (Chen 2014a; Sun 2016; Wang 2015; Wang 2016; Yang 2016), Taiwan (Liu 2010), Germany (Endres 2012), USA and Canada (Dohm 2014), and Germany and the USA (Vogl 2013). Eight trials received at least some funding from medical device companies who manufacture vertebral augmentation systems (Buchbinder 2009; Clark 2016; Dohm 2014; Evans 2015; Farrokhi 2011; Klazen 2010; Firanescu 2018; Vogl 2013); two clearly reported that they had no role in the trial (design, data collection, data analysis, preparation of the manuscript)(Buchbinder 2009; Clark 2016); while five trials did not report source of funding (Chen 2014a; Leali 2016; Sun 2016; Voormolen 2007; Wang 2015).

Trial duration varied from two weeks (Voormolen 2007) to three years (Farrokhi 2011). Seven trials allowed cross‐over: Kallmes 2009 allowed blinded cross‐over to the alternate procedure at one month or later if adequate pain relief was not achieved; both Voormolen 2007 and Farrokhi 2011 allowed participants assigned to the control arm still in severe pain after two weeks to undergo vertebroplasty; Blasco 2012, Chen 2014a and Yang 2016 allowed participants in the conservative therapy group to be considered for vertebroplasty if there was no improvement in pain but the timing of this decision was not provided; and in VOPE 2015 cross‐over between groups was allowed after three months although no details about who could cross over were not provided.

Trial participants

The 21 trials included 2852 randomised participants with trial sizes varying from 46 participants (Voormolen 2007) to 404 participants (Dohm 2014). In general, inclusion criteria for all trials were similar requiring a clinical history and imaging findings consistent with one or more acute osteoporotic vertebral fractures (see Characteristics of included studies table). Across all trials the majority of participants were female and Evans 2015 only included women (see Table 3). Mean age of participants ranged between 62.6 and 81 years.

Symptom duration varied across trials with mean duration ranging from around a week (Rousing 2009) to more than six months (Farrokhi 2011). For the placebo‐controlled trials, mean duration of symptoms ranged from less than three weeks to 20 weeks across treatment groups in the individual trials (vertebroplasty and placebo: Buchbinder 2009 nine and 9.5 weeks; Clark 2016 2.8 and 2.4 weeks; Kallmes 2009 16 and 20 weeks; Firanescu 2018 29.2 and 25.9 days; and VOPE 2015 did not report mean duration but trial inclusion specified a symptom duration of eight weeks or less).

Mean baseline pain and disability scores were similar across trials. Mean pain at baseline was greater than seven out of 10 (where 10 is the worst pain) in most trials, except the usual care group of Blasco 2012 (mean 6.3), both arms of Chen 2014a (means 6.5 and 6.4 in the vertebroplasty and usual care arms, respectively), the vertebroplasty arm of Kallmes 2009 (mean 6.9), and was low in Leali 2016 (mean 4.8 in vertebroplasty, not reported in usual care) and Leali 2016 (mean pain score 4.8 out of 25 and Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) 53.6% in the vertebroplasty group and not reported in the conservative care group). In VOPE 2015, the mean baseline pain was greater than 70 out of 100 for activity pain( 74.68 in the vertebroplasty group and 76.08 in the placebo group), but not for rest pain (40.55 in the vertebroplasty group and 53.04 in the placebo group). Sun 2016 did not report baseline pain or disability scores.

Interventions

Details of interventions in each trial are presented in the Characteristics of included studies table. Vertebroplasty was performed by different specialists in the included trials: interventional radiologists in seven trials (Blasco 2012; Buchbinder 2009; Clark 2016; Firanescu 2018; Kallmes 2009; Klazen 2010; Voormolen 2007), orthopaedic surgeons in four trials (Chen 2014a; Endres 2012; Rousing 2009; VOPE 2015), neurosurgeons in one trial (Farrokhi 2011), spine surgeons in one trial (Wang 2016), a combination of interventional radiologists and neuroradiologists, orthopaedic surgeons and neurosurgeons in one trial (Dohm 2014), and the background of the interventionalist was not reported in seven trials (Evans 2015; Leali 2016; Liu 2010; Sun 2016; Vogl 2013; Wang 2015; Yang 2016).

Vertebroplasty appeared to have been performed in a similar way across all trials. However in Dohm 2014, the majority of participants in both treatment arms (75.1% in the vertebroplasty group and 80.6% in the kyphoplasty group) also had perioperative postural reduction in an attempt to correct vertebral deformity, and in Wang 2016 postural reduction was performed before surgery in both groups.

Mean vertebroplasty cement volume was not specified in four trials (Blasco 2012; Evans 2015; Rousing 2009; VOPE 2015) (see Characteristics of included studies table and Table 2). VOPE 2015 reported that up to 2 mL of cement was inserted but it was not clear if a uni‐ or bipedicular approach was used (which may mean that up to 4 mL was inserted). For the remaining trials, the mean cement volume ranged from 2.8 mL (Buchbinder 2009; Kallmes 2009) to 7.5 mL (Clark 2016). Mean (range) cement volume in the four placebo‐controlled trials was 2.8 mL (1.2 ml to 5.5 mL) (Buchbinder 2009), 7.5 mL (4.7 mL to 10.3 mL) (Clark 2016), 2.8 mL (1 mL to 5.5 mL) (based upon a subset of 20 participants) (Kallmes 2009) and 5.11 mL (1 mL to 11 mL) (Firanescu 2018).

There was diversity in the way that the sham vertebroplasty procedure was delivered in the five placebo‐controlled trials. Buchbinder 2009 most closely simulated vertebroplasty using an identical procedure to that performed in the vertebroplasty group up to the insertion of the needle into the bone, at which point the vertebral body was gently tapped with a blunt stylet and bone cement was prepared to permeate the strong smell of the polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) in the room. The sham procedure in the second placebo‐controlled trial was similar except that the vertebral body was not tapped with a blunt stylet (Kallmes 2009). For Clark 2016, both the trial registry and protocol paper reported that the placebo involved a 4 mm skin incision and light tapping of the skin, while the results paper states that a short needle was passed into the skin incision but not as far as the periosteum and that manual skin pressure and regular tapping on the needle was performed. The published protocol of Firanescu 2018 indicates that no needles would be placed periosteally in the placebo group but the methacrylate monomer would be opened to simulate the odour of mixing the bone cement and participants would receive verbal and physical cues (e.g. pressure on the back) to simulate the procedure.. The published reported noted that bone biopsy needles were positioned periosteally bilaterally with preparation of the cement occurring in close proximity to the participants (so that the mixing sound could be heard and the polymethylmethacrylate smelt by everyone in the room). In VOPE 2015, PMMA was also opened for the odour but instead of cement, 2 mL of local anaesthetic (lidocaine) was injected into the fractured vertebrae.

Eight trials used variations on usual care as the comparator group (Blasco 2012; Chen 2014a; Farrokhi 2011; Klazen 2010; Leali 2016; Rousing 2009; Voormolen 2007; Yang 2016) (see Characteristics of included studies table). This included analgesics including acetaminophen, codeine, tramadol and/or opioids in all instances, and these could be adjusted as needed. Five trials specified the use of non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), which could have been in addition to analgesics, when simple analgesia was ineffective or for those intolerant to opioid derivatives (Farrokhi 2011; Klazen 2010; Leali 2016; Voormolen 2007; Yang 2016). Three trials also prescribed calcitonin (Blasco 2012; Farrokhi 2011; Yang 2016) and three also offered brace treatment (Chen 2014a; Rousing 2009; Yang 2016).

Seven trials compared vertebroplasty with kyphoplasty (Dohm 2014; Endres 2012; Evans 2015; Liu 2010; Sun 2016; Vogl 2013; Wang 2015). Dohm 2014, Endres 2012, Liu 2010 and Wang 2015 compared vertebroplasty with balloon kyphoplasty. Endres 2012 also compared vertebroplasty with a shield kyphoplasty which instead of a balloon, uses specialised instrumentation to create a central cavity in the vertebral body and inserts a self‐expanding implant that controls the cement flow. Endres 2012 compared vertebroplasty with the same shield kyphoplasty. Evans 2015 compared vertebroplasty with kyphoplasty, however it did not report the kyphoplasty technique used. Sun 2016 compared high‐viscosity cement vertebroplasty with low‐viscosity cement kyphoplasty.

A single trial injected a mixture of prednisolone (125 mg:5 mL) and lidocaine (100 mg:5 mL) under fluoroscopic monitoring into the facet joint of the fractured vertebra as the control intervention (Wang 2016).

Outcomes

Pain

All trials included at least one measure of pain, but its measurement varied across trials. Three trials specified pain over the preceding 24 hours (Clark 2016; Farrokhi 2011; Kallmes 2009), one trial specified pain over the course of the previous week (Buchbinder 2009), and 16 trials did not specify a time period (Blasco 2012; Chen 2014a; Dohm 2014; Endres 2012; Evans 2015; Klazen 2010; Leali 2016; Liu 2010; Rousing 2009; Sun 2016; Firanescu 2018, Voormolen 2007; VOPE 2015; Wang 2015; Wang 2016; Yang 2016). Vogl 2013 only reported baseline pain in their published trial report but measurement of pain (and disability assessed by the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI)) was referred to in a congress abstract of the same trial published in German; whether or not a time period was specified is not known.

Buchbinder 2009 measured overall pain, pain at rest and pain in bed at night, while Kallmes 2009 measured average back pain intensity. Clark 2016 specified the measurement of pain at rest and pain with standing or activity in addition to average pain intensity but these results were not reported. Leali 2016 measured pain on a visual analogue scale (VAS) (zero ‐ no pain to five ‐ maximum pain) during walking, sitting and rising from a chair, bathing, dressing, and at rest, and summed all five scores to derive a total score out of 25. VOPE 2015 measured rest pain and pain during forward bending resembling a patient in activity (both on a zero to 100 VAS). All remaining trials referred to pain or mean pain unqualified by additional descriptors.

All but two trials, included a measure of pain using either a zero to 10 VAS or zero to 10 numerical rating scale, although the descriptor for a score of 10 differed across trials (e.g. maximum pain (Blasco 2012; Clark 2016), maximal imaginable pain (Buchbinder 2009), worst pain imaginable (Chen 2014a), worst possible (Dohm 2014), pain as bad as could be (Kallmes 2009), worst pain ever (Klazen 2010;Firanescu 2018), worse pain possible (Rousing 2009), worst pain in the patient's life (Voormolen 2007), and no descriptors specified (Evans 2015; Liu 2010; Wang 2015; Yang 2016)). The pain scale investigated by Farrokhi 2011 measured pain on a one (no pain) to 10 (excruciating pain) VAS, while Endres 2012 did not specify the pain scale explicitly although it was likely to have been on a zero to 100‐point scale (as mean baseline scores varied between 78.2 and 90). As described above, Leali 2016 used a zero to five VAS to measure pain during five activities and summed them for a score out of 25. Sun 2016 used a VAS to measure pain, but the scale range and descriptors (if any), were not reported. VOPE 2015 used a zero to 100 VAS and the descriptor (if any), were not reported.

Four trials also included a dichotomous measure of pain. Blasco 2012 measured the number of participants with moderate (pain ≥ 4) or severe (pain ≥ 7) pain at 12 months. Three trials included the proportion of participants with pain improved by a clinically relevant amount although the definitions varied. Buchbinder 2009 reported the proportion of people with improvement of overall pain, pain at rest and pain in bed at night of ≥ 2.5 units as post‐hoc analyses performed at the request of the publishing journal (external reviewer request). Clark 2016 reported the proportion of participants achieving an NRS pain score of <4 out of 10 (from a baseline score of ≥ 7 out of 10). Kallmes 2009 measured the proportion of participants with clinically important improvement in pain defined as at least 30% improvement.

Four trials also included other measures of pain. Evans 2015 and Kallmes 2009 included the Pain Frequency and Pain Bothersomeness Indices (each measured on a zero to four‐point scale, with higher scores indicating more severe pain). Klazen 2010 measured the number of pain‐free days (defined as days with a VAS score of three or lower) and Rousing 2009 included the Dallas Pain Questionnaire (DPQ), a 16‐item instrument that assesses four aspects of daily living affected by chronic back pain (day‐to‐day activities, work and leisure activities, anxiety and depression and social interest), measured as a percentage of pain interference in each of the four aspects (0% is no pain and 100% is pain all the time).

Disability

All except four trials (Blasco 2012; Liu 2010; Rousing 2009; VOPE 2015), included a back‐specific measure of disability or function and two trials included two back‐specific measures (Chen 2014a; Wang 2016). Nine trials included the Roland‐Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ) (Buchbinder 2009; Chen 2014a; Clark 2016; Evans 2015; Kallmes 2009; Klazen 2010; Firanescu 2018; Voormolen 2007; Wang 2016) and 10 trials included the ODI (Chen 2014a; Dohm 2014; Endres 2012; Farrokhi 2011; Leali 2016; Sun 2016; Vogl 2013; Wang 2015; Wang 2016; Yang 2016) (although no data were presented in Vogl 2013). In Dohm 2014, section eight, regarding sexual activity was removed from the ODI. Three trials also included the physical function dimension component of the SF‐36 (Dohm 2014; Evans 2015; Kallmes 2009). Two trials only included the physical function dimension component of the SF‐36 as a measure of disability (Rousing 2009; VOPE 2015) and two trials included no measures of disability (Blasco 2012; Liu 2010).

Evans 2015 and Kallmes 2009 also included the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures‐Activities of Daily Living (SOF‐ADL) scale and Kallmes 2009 measured the proportion with clinically important improvement in disability (at least 30% improvement), while Rousing 2009 also included the Barthel Index and Farrokhi 2011 included ability to walk after one day.

Health‐related quality of life

Eight trials did not include a measure of health‐related quality of life (Chen 2014a; Endres 2012; Farrokhi 2011; Leali 2016; Liu 2010; Sun 2016; Vogl 2013; Wang 2015).

Seven trials included the Quality of Life Questionnaire of the European Foundation for Osteoporosis (QUALEFFO) (Blasco 2012; Buchbinder 2009; Clark 2016; Klazen 2010; Firanescu 2018; Voormolen 2007; Yang 2016) as a vertebral fracture and/or osteoporosis‐specific measure.

Six trials included an overall measure of health‐related quality of life: five trials included the Mental Component Summary (MCS) subscale of the SF‐36 (Evans 2015; Kallmes 2009; Rousing 2009; VOPE 2015; Wang 2016), eight trials included the European Quality of Life with 5 Dimensions (EQ‐5D) (Buchbinder 2009; Clark 2016; Dohm 2014; Evans 2015; Kallmes 2009; Klazen 2010; Rousing 2009; VOPE 2015), one trial included the Assessment of Quality of Life (AQoL) (Buchbinder 2009), and one trial included the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures‐Activities of Daily Living (SOF‐ADL6), Modified Deyo Patrick Pain Frequency and Bothersomeness Scale and the Osteoporotic Assessment Questionnaire (OPAQ) Body Image Scale (Evans 2015).

Treatment success

Two trials included a specific patient‐reported measure of treatment success. Buchbinder 2009 defined treatment success as 'moderately better' or 'a great deal better' for pain, fatigue and overall health on seven‐point ordinal scales, ranging from a 'great deal worse' to a 'great deal better'. Yang 2016 measured patient satisfaction as 'very satisfied' 'satisfied' or 'unsatisfied'.

As described above, three trials included one or more investigator‐specified measures of treatment success as determined by the number of participants who achieved various thresholds of pain and/or disability improvement (Buchbinder 2009; Clark 2016; Kallmes 2009).

Incident symptomatic and/or radiographically apparent vertebral fractures

Most trials recorded the occurrence of new symptomatic and/or radiologically apparent vertebral fractures.

Three trials reported the occurrence of both (Blasco 2012 up to 12 months; Buchbinder 2009 up to 24 months; Dohm 2014 up to 24 months).

Four trials reported new symptomatic vertebral fractures (Chen 2014a up to one year; Farrokhi 2011 up to 24 months; Leali 2016 up to six months; Voormolen 2007 up to two weeks) and five trials only reported occurrence of incident radiographic vertebral fractures (Clark 2016 at six months; Klazen 2010 at one, three and 12 months; Rousing 2009 at three and 12 months; VOPE 2015 at 12 months; Wang 2016 at 12 months; Yang 2016 at one, three, six and 12 months).

Liu 2010, Wang 2015 and Firanescu 2018 reported new vertebral fractures but did not specify if they were symptomatic or only detected on imaging, and Vogl 2013 reported radiographic refractures and adjacent level fractures up to 12 months and whether or not these were symptomatic. Endres 2012 only reported upon new adjacent fractures up to six months, while Evans 2015, Kallmes 2009 and Sun 2016 did not report occurrence of new vertebral fractures during the period of follow‐up.

Other serious adverse events

Adverse events, other than reporting of new symptomatic or asymptomatic vertebral fractures were variably reported across trials. Ten trials made specific reference to presence/absence of other adverse events in both treated groups (Buchbinder 2009; Clark 2016; Dohm 2014; Endres 2012; Kallmes 2009; Leali 2016; Sun 2016; Firanescu 2018; VOPE 2015; Yang 2016).

Blasco 2012, Chen 2014a, Wang 2015 and Yang 2016 reported on the presence/absence of clinical complications from cement leakage in the vertebroplasty‐treated group but did not report whether or not other adverse events occurred in either group; Farrokhi 2011, Klazen 2010 and Voormolen 2007 reported adverse events that occurred in the vertebroplasty‐treated group but did not report whether or not adverse events occurred in the usual care group. Evans 2015, Liu 2010, Rousing 2009 and Wang 2016 did not report the presence or absence of other adverse events.

Excluded studies