Abstract

Background

Surgery is an important part of the management of oral cavity cancer with regard to both the removal of the primary tumour and removal of lymph nodes in the neck. Surgery is less frequently used in oropharyngeal cancer. Surgery alone may be treatment for early‐stage disease or surgery may be used in combination with radiotherapy, chemotherapy and immunotherapy/biotherapy. There is variation in the recommended timing and extent of surgery in the overall treatment regimens of people with these cancers. This is an update of a review originally published in 2007 and first updated in 2011.

Objectives

To determine which surgical treatment modalities for oral and oropharyngeal cancers result in increased overall survival, disease‐free survival and locoregional control and reduced recurrence. To determine the implication of treatment modalities in terms of morbidity, quality of life, costs, hospital days of treatment, complications and harms.

Search methods

Cochrane Oral Health's Information Specialist searched the following databases: Cochrane Oral Health's Trials Register (to 20 December 2017), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2017, Issue 11), MEDLINE Ovid (1946 to 20 December 2017) and Embase Ovid (1980 to 20 December 2017). We searched the US National Institutes of Health Trials Registry (ClinicalTrials.gov) and the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform for ongoing trials. There were no restrictions on the language or date of publication.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials where more than 50% of participants had primary tumours of the oral cavity or oropharynx, or where separate data could be extracted for these participants, and that compared two or more surgical treatment modalities, or surgery versus other treatment modalities.

Data collection and analysis

Two or more review authors independently extracted data and assessed risk of bias. We contacted study authors for additional information as required. We collected adverse events data from included studies.

Main results

We identified five new trials in this update, bringing the total number of included trials to 12 (2300 participants; 2148 with cancers of the oral cavity). We assessed four trials at high risk of bias, and eight at unclear. None of the included trials compared different surgical approaches for the excision of the primary tumour. We grouped the trials into seven main comparisons.

Future research may change the findings as there is only very low‐certainty evidence available for all results.

Five trials compared elective neck dissection (ND) with therapeutic (delayed) ND in participants with oral cavity cancer and clinically negative neck nodes, but differences in type of surgery and duration of follow‐up made meta‐analysis inappropriate in most cases. Four of these trials reported overall and disease‐free survival. The meta‐analyses of two trials found no evidence of either intervention leading to greater overall survival (hazard ratio (HR) 0.84, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.41 to 1.72; 571 participants), or disease‐free survival (HR 0.73, 95% CI 0.25 to 2.11; 571 participants), but one trial found a benefit for elective supraomohyoid ND compared to therapeutic ND in overall survival (RR 0.40, 95% CI 0.19 to 0.84; 67 participants) and disease‐free survival (HR 0.32, 95% CI 0.12 to 0.84; 67 participants). Four individual trials assessed locoregional recurrence, but could not be meta‐analysed; one trial favoured elective ND over therapeutic delayed ND, while the others were inconclusive.

Two trials compared elective radical ND with elective selective ND, but we were unable to pool the data for two outcomes. Neither study found evidence of a difference in overall survival or disease‐free survival. A single trial found no evidence of a difference in recurrence.

One trial compared surgery plus radiotherapy with radiotherapy alone, but data were unreliable because the trial stopped early and there were multiple protocol violations.

One trial comparing positron‐emission tomography‐computed tomography (PET‐CT) following chemoradiotherapy (with ND only if no or incomplete response) versus planned ND (either before or after chemoradiotherapy), showed no evidence of a difference in mortality (HR 0.92, 95% CI 0.65 to 1.31; 564 participants). The trial did not provide usable data for the other outcomes.

Three single trials compared: surgery plus adjunctive radiotherapy versus chemoradiotherapy; supraomohyoid ND versus modified radical ND; and super selective ND versus selective ND. There were no useable data from these trials.

The reporting of adverse events was poor. Four trials measured adverse events. Only one of the trials reported quality of life as an outcome.

Authors' conclusions

Twelve randomised controlled trials evaluated ND surgery in people with oral cavity cancers; however, the evidence available for all comparisons and outcomes is very low certainty, therefore we cannot rely on the findings. The evidence is insufficient to draw conclusions about elective ND of clinically negative neck nodes at the time of removal of the primary tumour compared to therapeutic (delayed) ND. Two trials combined in meta‐analysis suggested there is no difference between these interventions, while one trial (which evaluated elective supraomohyoid ND) found that it may be associated with increased overall and disease‐free survival. One trial found elective ND reduced locoregional recurrence, while three were inconclusive. There is no evidence that radical ND increases overall or disease‐free survival compared to more conservative ND surgery, or that there is a difference in mortality between PET‐CT surveillance following chemoradiotherapy versus planned ND (before or after chemoradiotherapy). Reporting of adverse events in all trials was poor and it was not possible to compare the quality of life of people undergoing different surgical treatments.

Plain language summary

Surgical treatments for oral cavity (mouth) and oropharyngeal (throat) cancers

Review question

We evaluated clinical trials of surgical treatments for oral and oropharyngeal cancers to find out which were most likely to result in people with these cancers living longer (overall survival). living longer without symptoms (disease‐free survival), and not experiencing a recurrence of the cancer at the same site or spread to other sites. We also wanted to find out how different treatments affect disease symptoms, quality of life, time in hospital, complications, side effects and cost.

Background

Oral cancer is among the most common cancers worldwide, with more than 400,000 new cases diagnosed in 2012. The treatment of these cancers can involve surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or a combination of two or all three therapies. This topic area was identified as a priority by an expert working group for oral and maxillofacial surgery in 2014. Authors working with Cochrane Oral Health conducted this review, which is an update of a review originally published in 2007 and first updated in 2011. The evidence is current to 20 December 2017.

Study characteristics

We included 12 trials (five new for this update) that investigated the success of surgical treatment for oral cancers. The studies involved 2300 participants, 2148 of whom had mouth cancers. The trials included seven comparisons of different treatment options. None of them compared different surgical approaches for cutting out the primary tumour.

Key results

The findings of the studies are mixed and it is not possible to draw firm conclusions about the optimal surgical approach for mouth and throat cancers.

Surgical removal of the lymph nodes in the neck that appear to be cancer‐free, at the same time as the cancer is removed did not seem to be associated with longer survival in two studies whose results were combined. Another study, however, suggested there may be a benefit of early neck surgery in terms of overall survival and 'disease‐free survival' (length of time after primary treatment without signs and symptoms of disease). One study found cancer recurrence at or around the same site was less likely with the early surgery, while three other studies did not favour either treatment.

There was no evidence that removal of all the lymph nodes in the neck resulted in longer survival compared to selective surgical removal of affected lymph nodes.

One study evaluated use of a special scan (positron‐emission tomography‐computed tomography (PET‐CT)), after a combination of chemotherapy and radiotherapy, to guide decisions about neck dissection, and found no difference in mortality (death) compared with undertaking a planned neck dissection before or after chemoradiotherapy.

There were a number of other surgical approaches compared in the studies, but we were unable to use the results in this review.

Although removal of lymph nodes from the neck is known to be associated with significant negative effects related to appearance and functions such as eating, drinking and speaking, the studies reported poorly on these side effects and did not measure quality of life accurately enough or in large enough numbers to be included in any of our analyses.

Certainty of the evidence

The certainty of the evidence was very low as there were few studies for each comparison and they were at risk of bias because of the way they were designed. Some comparisons and outcomes had no useable results.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Head and neck cancers (HNC) comprise laryngeal, pharyngeal and oral cancers. Collectively, they are the sixth most common cancer in the world, accounting for approximately 5% of all malignant tumours (Torre 2015). HNC generally have common risk factors and aetiology (Winn 2015); however, since the late 2000s, oropharyngeal (throat) cancers have increasingly been associated with human papillomavirus (HPV), unlike other oral cancers (D'Souza 2007). The tumours do not always recognise the boundaries between the oral cavity and oropharynx, with tumours frequently overlapping these sites (Tapia 2011).

HNCs are increasingly treated by multidisciplinary HNC teams in centralised units (Hughes 2012; Lo Nigro 2017). Clinical trials have generally recruited people with HNCs as if this was a single disease entity (Adelstein 2009). This influences the evidence base available to draw from in a systematic review.

Oral cancer (defined here to include both oral cavity and oropharynx cancers) is among the most common cancers worldwide, with approximately 442,760 incident cases and 241,418 deaths reported in 2012 (Ferlay 2013; Stewart 2014). There are geographical variations in the incidence of oral cancers, with increase among men and women in some European countries, stabilisation in certain Asian countries, and decrease in Canada and USA (Chaturvedi 2013; Simard 2014). In the UK, incidence trends are continuing to rise, driven mainly by oropharyngeal cancer rates (Louie 2015; Purkayastha 2016). Survival following a diagnosis of oral cavity or oropharyngeal cancer remains poor with five‐year survival around 50% overall, with only limited improvement since the late 1980s (Warnakulasuriya 2009).

There is overwhelming evidence that tobacco use, alcohol consumption and betel quid chewing are the main risk factors in the aetiology of oral cancer (Gupta 2014; La Vecchia 1997; Macfarlane 1995; Winn 2015). There is also strong evidence that low socioeconomic status (educational attainment and income) is associated with substantial increased risk not explained by tobacco and alcohol (Conway 2015). There is a higher incidence of oral cancers among men (Freedman 2007), and the vast majority of cases occur in men over 50 years of age (Warnakulasuriya 2009), and among low socioeconomic groups (Conway 2008). However, the ratio of males to females diagnosed with oral cancers has changed from approximately 5:1 in the 1960s to less than 2:1 after 2000 (Parkin 2005; Purkayastha 2016).

Two distinct types of oropharyngeal cancer exist as classified according to HPV status. HPV‐negative oropharyngeal cancer is epidemiologically similar to the traditional type of cancer of the upper aerodigestive tract, in which long‐term exposure to tobacco and alcohol products leads to development of malignancy. HPV‐positive oropharyngeal cancer starts with exposure to high‐risk HPV, most often HPV 16, and can develop independently of tobacco or alcohol exposure (Gillison 2000). People with HPV‐positive oropharyngeal cancer are more likely to be male and of a relatively younger age than their HPV‐negative counterparts (Chaturvedi 2008; Chaturvedi 2015; Gillison 2007). Moreover, they have a better overall performance and are less likely to be smokers or heavy alcohol consumers (Gillison 2000). In the US, it is suggested that more the 70% of oropharyngeal cancers are HPV positive (Chaturvedi 2011).

The link between oncogenic HPV and oropharyngeal cancer is strong and has been documented in numerous studies, fulfilling the epidemiological criteria for disease causality, especially in the development of oropharyngeal cancer in non‐smokers (Sturgis 2007). Since the early 1990s, the proportion of people with oropharyngeal cancer who are HPV positive has increased dramatically (Attner 2010; Ryerson 2008), but it is interesting to note that this group of people have significantly improved rates of both overall survival and disease‐free survival (Adelstein 2009; Fakhry 2006; Fakhry 2008; Licitra 2006), and more recent trials are beginning to treat HPV‐positive oropharyngeal cancers differently (Blanchard 2011; Holsinger 2015; Parsons 2002). There is evidence to suggest that the rate of oral cavity cancer has reached a plateau, whereas the proportion of people developing oropharyngeal cancer is increasing and is projected to continue to increase (Purkayastha 2016).

Description of the intervention

Surgery can be combined with one or more other treatments, that is, radiotherapy, chemotherapy and immunotherapy/biotherapy; the sequence of these combination therapies is considered important. Radiotherapy is typically now administered postoperatively. Chemotherapy can be given: 1. before surgery (induction/neoadjuvant – when treatment is administered before the primary therapy, e.g. to shrink a tumour prior to surgery or radiation); 2. after surgery (adjuvant – administered after the primary therapy, e.g. when the primary therapy to treat a cancerous tumour is surgery, chemotherapy would be considered an adjuvant therapy) and before radiotherapy; 3. at the same time as radiotherapy (concomitant/concurrent – it may also be referred to as chemoradiotherapy); or 4. alternating with radiotherapy. In recent years, a form of radiotherapy called intensity‐modulated radiotherapy (IMRT) has been used to treat oral cancers, which uses use higher radiation doses than traditional therapies with a better chance of locoregional control while sparing more of the surrounding healthy oral tissue from harmful doses and effects of radiation (Brennan 2017; Studer 2007).

The locoregional control of the primary tumour is the main criterion of successful treatment. Tumours are excised with a margin of clinically normal tissue (typically between 1 cm and 2 cm in the UK). Despite this apparent complete clinical surgical excision, the tumour may still be demonstrated at the margins histopathologically; this has prognostic implications (Batsakis 1999; Sutton 2003). Margins apparently histologically free of tumour may demonstrate molecular changes and the presence of such tumour clonogen populations at the margins may be predictive for disease progression (Partridge 2000).

Spread of the tumour to the regional lymph nodes within the neck (cervical nodes) is an early and consistent event in the natural history of oral and oropharyngeal cancers (Haddadin 2000). The extent of cervical involvement is reflected in the staging of the tumour and has prognostic implications (Shah 1990). Therefore, surgical dissection of the cervical lymph nodes at risk of metastasis may be undertaken as part of the management of the primary tumour. The classic radical neck dissections (RND) removed all of the cervical lymph nodes from levels I to V combined with the sternocleidomastoid muscle, internal jugular vein, submandibular gland and the spinal accessory nerve, with resultant significant postoperative morbidity particularly in relation to loss of the accessory nerve. In one study of 100 cases following RND, almost half of the participants experienced shoulder pain, shoulder droop and a reduction in the range of motion (Ewing 1952). One more recent study comparing RND with accessory nerve‐sparing surgery found all of the cases with RND had severe shoulder dysfunction compared with only 7% of the cases who had nerve‐sparing surgery (Umeda 2010). RND is now only reserved for advanced neck disease. Modifications of the neck dissection to preserve some or all of the associated structures have reduced morbidity and may now be undertaken as selective neck dissections (Carew 2003; Robbins 2002). There has been an increasing trend of using selective neck dissection as a therapeutic procedure in the clinically N0 neck (indicating no palpable nodes on clinical examination). In addition to the extent of neck disease at presentation, spread of the tumour outside the capsule of the lymph nodes (extracapsular spread) is also an indicator of a poor prognosis (Woolgar 2003). Distant metastasis is uncommon in HNC with one study reporting 13.8% in 1022 cases (Duprez 2017). Locoregional disease recurrence remains the dominant mode of treatment failure for people with advanced tumours (Brizel 1998). Historically, clinicians treating oral cancer did not focus on distant metastatic disease because locoregional control had been the main cause of death and there were fewer effective chemotherapeutic agents to deal with distant metastases. With improvements in locoregional control, distant metastases are an increasing issue in the management of oral cancer.

When early stage tumours (T1, less than 2 cm, or T2, 2 cm to 4 cm) present with apparently clinically negative neck nodes, there is controversy over the management of the cervical lymph nodes (Woolgar 2003). To date, imaging of the head and neck region is not sensitive enough to identify nodal micrometastases as the rate of occult metastases has been reported as 23% to 43% (Ebrahimi 2012). Studies have demonstrated an improved outcome when a neck dissection has been undertaken at the same time as the resection of the primary tumour rather than waiting for neck disease to present subsequently (Haddadin 2000; Hughes 1993), although others adopt a 'wait and ' policy. One current clinical guideline recommends that T1 and T2 oral cancer with a clinically negative neck should receive prophylactic neck treatment (Paleri 2016). However, this implies overtreatment and treatment‐associated morbidity in the majority of people (Dias 2001). There is evidence of improved overall and disease‐free survival in people with early‐stage oral squamous‐cell cancer (SCC) who had an elective neck dissection in comparison with therapeutic neck dissection (D'Cruz 2015).

The use of sentinel node biopsy (SNB) is now being advocated for small tumours with a clinically negative neck. One UK guideline recommends that biopsy should be offered to people with oral cancer (T1‐T2N0), as it is in the Netherlands and Denmark (Holden 2018; NICE 2018). One European study reported a sensitivity of 86% and negative predictive value of 95% with SNB and concluded that this is a reliable and safe oncological technique for staging the clinically N0 neck in people with T1 and T2 oral cancer (Schilling 2015). Yang 2017 also indicated that a high sensitivity and negative predictive value have been reported with SNB in a larger study including meta‐analysis of cT1/T2N0 people with tongue SCC. The widespread introduction of SNB for oral SCC will result in individual treatment that enables people at high risk to be suitably treated early in the disease process, and people at low risk to be spared unnecessary surgery (Schilling 2017).

Why it is important to do this review

Cochrane Oral Health undertook an extensive prioritisation exercise in 2014 to identify a core portfolio of titles that were the most clinically important ones to maintain on the Cochrane Library (Worthington 2015). The Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Expert Panel identified this review as a priority (Cochrane Oral Health Priority Reviews).

The management of advanced oral cavity and oropharyngeal cancers is problematic and has traditionally relied on surgery and radiotherapy, both of which are associated with substantial adverse effects. Although there have been new treatments developed, there has been limited improvement in survival since the late 1970s (Warnakulasuriya 2009). Oropharyngeal cancers have relatively 'silent' symptoms, which may not be present during the early stages of the disease. This is a possible explanation for the fact that the disease stage at diagnosis has not altered since the 1960s despite public education (McGurk 2005). Tumour recurrence and the development of multiple primary tumours are the major causes of treatment failure (Day 1992; Partridge 2000; Woolgar 2003). Surgical treatment may be disfiguring and result in a substantially reduced quality of life as people with oral and oropharyngeal cancers are socially isolated, due to difficulties with altered appearance, speech, eating and drinking. Developments in the way in which surgery is delivered aim to improve its efficacy and reduce the impact on people's quality of life.

This review was undertaken as part of a series of reviews looking at the different treatment modalities for oral cancer (Furness 2011; Glenny 2010): surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy and immunotherapy. In this update of our surgical review, we aimed to answer two broad questions.

Does surgery, in addition to chemotherapy, radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy, improve outcomes for people with oral cavity and oropharyngeal cancers?

Which type of surgery improves outcomes for people with oral cavity and oropharyngeal cancers?

In this surgical review, we included all randomised controlled trials (RCTs) where more than 50% of participants had primary tumours in the oral cavity or oropharynx or where separate data could be extracted for these types of cancer. We included only trials where participants in each treatment arm received different surgical interventions (either different techniques or timing); or radiotherapy, chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy with or without surgery; or surgery versus no surgery.

Objectives

Primary objective

To determine which surgical treatment modalities for oral and oropharyngeal cancers result in increased overall survival, disease‐free survival, locoregional control and reduced recurrence.

Secondary objective

To determine the implication of treatment modalities in terms of morbidity (quality of life, complications, harms and adverse events) and Utilization of the Health care services (costs, hospital days of treatment).

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

RCTs comparing different surgical treatment modalities or trials of other treatment interventions with and without surgery including radiotherapy and chemotherapy. We anticipated that there would be no studies comparing surgery with placebo (although if there were such studies they would have been included).

Types of participants

People with oral cancer as defined by the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology (ICD‐O) codes as C01‐C02, C03, C04, C05‐C06 (oral cavity) and cancer of the oropharynx (ICD‐O: C09, C10). We excluded hypopharynx (ICD‐O: C13), nasopharynx (ICD‐O: C11), larynx (ICD‐O: C32) and cancers of the lip (ICD‐O: C00) (WHO 1990).

We included studies of HNC with cases of oral cancer (as long as at least 50% of participants had oral cavity or oropharyngeal cancer, or data for these cancers alone are available separately).

Cancers were primary SCCs arising from the oral mucosa. We included histological variants of SCCs (e.g. adenosquamous, verrucous, basaloid, papillary). Although they are known to have differing natural history to most conventional SCCs, they have a common aetiology, incidence is low and they are generally managed in the same way. We included carcinoma in situ.

We excluded epithelial malignancies of the salivary glands, odontogenic tumours, all sarcomas and lymphomas as these have a different aetiology and are managed differently.

Types of interventions

Surgical treatment of the primary tumour is typically one of the primary treatment interventions. Surgical treatment could have included traditional scalpel‐based surgery, laser cutting or ablation, or harmonic scalpel. We included trials that compared surgical treatment with another surgical intervention; different treatment modalities such as radiotherapy, chemotherapy, immunotherapy/biotherapy with or without surgery; any combinations were considered providing they were compared to surgery in at least one arm of the study. We did not consider salvage or palliative surgery.

We included studies that carried out surgical treatment of the neck lymph nodes (cervical lymph nodes) before, after or at the same time as surgical treatment of the primary tumour. We did not consider studies when there was surgical treatment of the cervical lymph nodes but no treatment of the primary tumour. We included studies concerned with cervical lymph node management in the surgical treatment of the primary tumour.

The treatments received and compared must have been the primary treatment for the tumour and participants should not have received any prior intervention other than diagnostic biopsy.

Types of outcome measures

As we did not expect many data, we planned to report outcomes at all time points reported, other than for 'time to event' data as the hazard ratios (HR) would be used to summarise this.

Primary outcomes

Overall survival (or total mortality) (disease‐related mortality will also be studied, if possible).

Disease‐free survival (or new disease, progression and mortality).

Locoregional recurrence.

Recurrence.

Secondary outcomes

Harms associated with treatment.

Quality of life.

Direct and indirect costs to patients and health services.

Participant satisfaction.

Search methods for identification of studies

For previous versions of this review, searches were conducted as part of a series of Cochrane Reviews on the treatment modalities for treating oral cavity and oropharyngeal cancer. The reviews were divided into four themes: surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy and immunotherapy/targeted therapies. A search strategy was developed that would encompass three of the four broad themes simultaneously (surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, see Bessell 2011 for details of the search strategy). From 2011 onwards, we conducted a more specific search for the surgery theme.

Electronic searches

Cochrane Oral Health's Information Specialist conducted systematic searches in the following databases for RCTs and controlled clinical trials. There were no language, publication year or publication status restrictions.

Cochrane Oral Health's Trials Register (searched 20 December 2017; Appendix 1);

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2017, Issue 11) in the Cochrane Library (searched 20 December 2017; Appendix 2);

MEDLINE Ovid (1946 to 20 December 2017; Appendix 3);

Embase Ovid (1980 to 20 December 2017; Appendix 4).

Subject strategies were modelled on the search strategy designed for MEDLINE Ovid. Where appropriate, they were combined with subject strategy adaptations of the highly sensitive search strategy designed by Cochrane for identifying RCTs and controlled clinical trials as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Chapter 6 (Lefebvre 2011).

Searching other resources

We searched the following trial registries for ongoing studies:

US National Institutes of Health Ongoing Trials Register ClinicalTrials.gov (clinicaltrials.gov; searched 20 December 2017; Appendix 5);

World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (apps.who.int/trialsearch; searched 20 December 2017; Appendix 6).

When necessary, we contacted authors of key papers and abstracts to request further information about their trials.

We searched the reference lists of included studies and relevant systematic reviews for further studies.

We did not perform a separate search for adverse effects of interventions used; we considered adverse effects described in included studies only.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

At least two review authors (from HW, VB, AMG, DC, MM) independently scanned the titles and abstracts (when available) of all reports identified through the electronic searches. The search was designed to be sensitive and include controlled clinical trials; these were filtered out early in the selection process if they were not randomised. As studies involving oral cancer are often included with those of the head and neck, we undertook a broad search to include all possible studies (Figure 1). For studies appearing to meet the inclusion criteria, or for which there were insufficient data in the title and abstract to make a clear decision, we obtained the full report. We excluded data from conference abstracts alone from the review. Two review authors independently assessed full reports obtained from the searches to establish whether the studies met the inclusion criteria or not. We resolved disagreements by discussion or by consulting a third review author if necessary. We recorded studies rejected at this or subsequent stages in the Characteristics of excluded studies table, and recorded our reasons for exclusion.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Data extraction and management

At least two review authors independently extracted data from included studies. The data extraction forms were piloted on several papers and modified as required before use. We discussed any disagreements and a third review author was consulted where necessary. However, group discussion was often required following data extraction due to the complexity of the data presented. When necessary, we contacted study authors for clarification or missing information.

For each trial, we recorded the following data.

Year of publication, country of origin and source of study funding.

Details of the participants including demographic characteristics and criteria for inclusion and exclusion, proportion with oral cavity and oropharyngeal cancer.

Details of the type of intervention, timing and duration.

Details of the outcomes reported, including method of assessment, and time intervals.

We planned to include HNC trials with only combined data (i.e. no outcome data available by primary tumour site) where greater than 50% of participants presented with oral/oropharyngeal cancer; however, where separate 'pure' oral/oropharyngeal cancer data were available for a trial, we extracted and analysed these 'pure' data and analysed and ignored the combined head and neck data.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

At least two review authors independently conducted assessment of risk of bias in included studies using the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool (Higgins 2011). We assessed six domains for each included study: sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding (of participant, carer, outcome assessor), completeness of outcome data, selective outcome reporting and other potential sources of bias. We made an overall risk of bias assessment for each study.

For this systematic review, we assessed risk of bias according to the following.

Sequence generation: low risk if use of a random number table, computerised system, central randomisation by statistical co‐ordinating centre, randomisation by an independent service using minimisation technique, permuted block allocation or Zelan technique. If the paper merely stated randomised or randomly allocated with no further information, we assessed this as being unclear.

Allocation concealment: low risk if centralised allocation including access by telephone call or fax, or pharmacy‐controlled randomisation, sequentially numbered, sealed, opaque envelopes.

Blinding: as mortality is the primary outcome that is most frequently and reliably reported, we decided to assess all trials as being at low risk of bias for this domain.

Outcome data: outcome data were considered complete if all participants randomised were included in the analysis of the outcome(s). However, in trials of treatment for cancer this is rarely the case. Trials where less than 10% of those randomised were excluded from the analysis, and where reasons for exclusions were described for each group, and where both numbers and reasons were similar in each group, were assessed at low risk of bias due to incomplete outcome assessment. Where postrandomisation exclusions were greater than 10%, or reasons were not given for exclusions from each group, or where rates and reasons were different for each group, we assessed the risk of bias due to (in)complete outcome data as unclear.

Selective outcome reporting: we assessed a trial at low risk of bias due to selective outcome reporting if the outcomes of interest that were described in the methods section were systematically reported in the results section. Where reported outcomes did not include those outcomes specified or expected in trials of treatments for oral cancer, or where additional analyses were reported, we assessed this domain as unclear.

Other bias: we noted examples of potential sources of bias such as imbalance in potentially important prognostic factors between the treatment groups at baseline, or the use of a cointervention in only one group (e.g. nasogastric feeding). If information was not available about the intervention groups at baseline, we assessed studies as being at unclear risk of bias.

Measures of treatment effect

The primary outcome most frequently and reliably reported was total mortality, expressed as an HR. An HR provides an estimate of the ratio of the hazard rates, for a particular event, between the experimental group and a control group over the duration of the entire study. For overall survival, the event of interest is death (total mortality). It is acknowledged that it is preferable to talk in terms of overall survival; however, statistically, the estimate of effect is the HR of death.

We entered these data into the meta‐analysis using the inverse variance method. If studies did not quote HRs, we calculated the log HR and the standard error from the available summary statistics or Kaplan‐Meier curves, according to the methods proposed by Parmar and colleagues (Parmar 1998), or requested these data from authors.

For dichotomous outcomes, we expressed the estimates of effect of an intervention as risk ratios (RR) together with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Dichotomous data were only used for primary outcomes where HRs were unavailable or could not be calculated. We planned to combine data of similar follow‐up periods.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We conducted meta‐analyses only if there were studies of similar comparisons reporting the same outcome measures. We assessed the significance of any discrepancies in the estimates of the treatment effects from the different trials using Cochrane's test for heterogeneity and the I² statistic, and we investigated any heterogeneity.

Data synthesis

We conducted meta‐analyses only if there were studies of similar comparisons reporting the same outcome measures. We combined RR for dichotomous data, and HRs for survival data, using random‐effect models.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Due to the different natural history and treatment regimens for oral cavity and oropharyngeal cancers, we planned to analyse these cancer types separately, if possible.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned sensitivity analysis (to examine the effects of randomisation, allocation concealment, blinded outcome assessment (if appropriate) and quality of follow‐up/completeness of data set), but there were insufficient data.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

We identified 6929 research papers through the electronic searching for this update, after the removal of duplicates (Figure 1). Screening of the titles and abstracts resulted in the identification of 26 potentially relevant trials for inclusion in the review. We retrieved full‐text copies of these articles. Further assessment of the papers resulted in five trials being included in this update of the review. Four of these trials were newly identified (Guo 2014; Iyer 2015; Mehanna 2017; Rastogi 2018), and one trial had previously been identified (D'Cruz 2015).

Included studies

Of the 12 trials included in the review, five were multicentred, with the number of centres ranging from two to 37. Three trials were undertaken in India (D'Cruz 2015; Fakih 1989; Rastogi 2018), two in Brazil (BHNCSG 1998; Kligerman 1994), two in China (Guo 2014; Yuen 2009), two in the UK (Mehanna 2017; Robertson 1998), one in centres across Europe (Austria, Germany and Switzerland) (Bier 1994), one in France (Vandenbrouck 1980), and one in Singapore (Iyer 2015). Twenty‐four trials, previously included in this review, have now been excluded, because they better fit in the other oral cancer treatment reviews (see Characteristics of excluded studies for details). Three trials required personal communication with the authors of the papers for retrieval of extra information (Kligerman 1994; Mehanna 2017; Robertson 1998).

Participants

Participants were recruited over periods ranging from two years to 11 years, with the earliest recruitment commencing in 1966 (Vandenbrouck 1980). A total of 2300 participants were randomly allocated to treatments and 2090 were included in the outcome evaluations. Most of the participants (2148) had oral cavity tumours and the remainder had oropharyngeal tumours.

All included trials reported tumour extent (TNM), four of which included participants with T1 to T2 tumours (D'Cruz 2015; Fakih 1989; Kligerman 1994; Yuen 2009), two with T2 to T4 tumours (BHNCSG 1998; Robertson 1998), two with T1 to T3 tumours (Rastogi 2018; Vandenbrouck 1980), and three with T1 to T4 tumours (Guo 2014; Iyer 2015; Mehanna 2017). In seven of the trials, participants had clinically negative neck nodes (BHNCSG 1998; D'Cruz 2015; Fakih 1989; Kligerman 1994; Rastogi 2018; Vandenbrouck 1980; Yuen 2009), three trials included participants with neck nodes clinically staged as N0‐2 (Guo 2014; Iyer 2015; Robertson 1998), and one trial included participants with clinically staged N2‐3 nodes (Mehanna 2017). The trial by Bier 1994 did not record the tumour stage or node status of the participants at trial entry (Table 12).

1. Stage of cancer.

| Study | TNM stage | Nodal status |

| BHNCSG 1998 | T2 to T4 | Negative neck |

| Bier 1994 | NS | Negative or positive neck |

| D'Cruz 2015 | T1 or T2 | Negative neck |

| Fakih 1989 | T1 or T2 | Negative neck |

| Guo 2014 | T1–T4 | Negative or positive neck |

| Iyer 2015 | T3 or T4 | Negative or positive neck |

| Kligerman 1994 | T1 or T2 | Negative neck |

| Mehanna 2017 | T1–T4 | N2 or N3 |

| Rastogi 2018 | T1–T3 | Negative neck |

| Robertson 1998 | T2–T4 | N0 to N2 |

| Vandenbrouck 1980 | T1–T3 | Negative neck |

| Yuen 2009 | T1 or T2 | Negative neck |

NS: not stated.

Of the 12 included trials, eight included recruited participants with oral cavity cancer only (BHNCSG 1998; Bier 1994; D'Cruz 2015; Fakih 1989; Kligerman 1994; Rastogi 2018; Vandenbrouck 1980; Yuen 2009); two included participants with oral cavity or oropharyngeal cancer (Guo 2014; Robertson 1998); one included participants with cancer of the oral cavity, oropharynx, hypopharynx, larynx and maxillary sinus (Iyer 2015); and one included participants with cancer of the oral cavity, tonsil, base of tongue, supraglottis and glottis or subglottis (Mehanna 2017).

Interventions

None of the included trials compared different surgical approaches to the excision of the primary tumour.

Nine trials of participants with oral cavity cancers compared either different surgical techniques for management of the lymph nodes in the neck or different timing for removal of the lymph nodes in the neck (BHNCSG 1998; Bier 1994; D'Cruz 2015; Fakih 1989; Guo 2014; Kligerman 1994; Rastogi 2018; Vandenbrouck 1980; Yuen 2009). Five trials compared the timing of neck dissection; either elective neck dissection at the same time as excision of the primary tumour or therapeutic neck dissection (delayed until nodes became clinically positive) (D'Cruz 2015; Fakih 1989; Kligerman 1994; Vandenbrouck 1980; Yuen 2009). Kligerman 1994 used a supraomohyoid (SOH) approach for the elective neck dissection in a group of participants with clinically negative neck nodes compared with a therapeutic neck dissection if the nodes became clinically positive. Yuen 2009 compared an elective selective neck dissection at the time of glossectomy with glossectomy alone plus therapeutic neck dissection if nodes became clinically positive. Fakih 1989 used elective RND at the same time as resection of the primary tumour in a group with clinically negative neck nodes. Vandenbrouck 1980 compared elective RND within two months of resection of the primary tumour with therapeutic neck dissection. D'Cruz 2015 compared a selective neck dissection with a modified therapeutic neck dissection.

Four trials compared different types of neck dissection surgery at the time of removal of the primary tumour (BHNCSG 1998; Bier 1994; Guo 2014; Rastogi 2018). In the trial by Bier 1994, both groups had a radical resection of the primary tumour. One group had RND at the same time as resection and the other had selective neck dissection surgery. The Brazilian Study group compared a modified RND with a SOH neck dissection in conjunction with resection of the primary tumour (BHNCSG 1998). Rastogi 2018 compared superselective neck dissection with SOH neck dissection in conjunction with resection of the primary tumour. Guo 2014 compared SOH neck dissection with modified RND in conjunction with resection of the primary tumour.

The trial by Robertson 1998 compared surgery followed by radiotherapy with radiotherapy alone in a group of participants with either oral cavity or oropharyngeal cancer. Iyer 2015 compared surgery and adjuvant radiotherapy with concurrent chemoradiotherapy. Mehanna 2017 compared positron‐emission tomography‐computed tomography (PET‐CT) guided watch and wait policy (with neck dissection undertaken only if no/incomplete response to chemoradiotherapy identified) with planned neck dissection before or after radical chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced head and neck SCC.

Outcome measures

The duration of follow‐up in the included trials ranged from approximately 15 months (Bier 1994) to 122 months (Yuen 2009). All trials except one reported either total mortality or overall survival (Yuen 2009), but not all provided data in a form suitable for inclusion in meta‐analysis. Six trials reported disease‐free survival (Bier 1994; D'Cruz 2015; Fakih 1989; Kligerman 1994; Vandenbrouck 1980; Yuen 2009), and seven trials reported recurrence (BHNCSG 1998; D'Cruz 2015; Fakih 1989; Kligerman 1994; Rastogi 2018; Robertson 1998; Yuen 2009).

Five trials mentioned harms/adverse events (BHNCSG 1998; D'Cruz 2015; Guo 2014; Mehanna 2017; Robertson 1998). BHNCSG 1998 reported the total number of adverse events in each group but not the number of participants affected. Two trials reported the percentages of participants in each group who experienced adverse effects (D'Cruz 2015; Robertson 1998). One trial reported quality‐adjusted‐life‐years (QALYs), costs and harms/adverse events (Mehanna 2017). One trial reported hospital days of treatment (Guo 2014).

Excluded studies

We excluded 24 trials that were previously included in this review because they better fit in the other oral cancer treatment reviews. Four previously included trials (Ang 2001; Lawrence 1974; Sanguineti 2005; Terz 1981) are now included in the radiotherapy review (Glenny 2010); 17 previously included trials (Bernier 2004; Cooper 2004; Lam 2001; Laramore 1992; Licitra 2001; Luboinski 1985; Maipang 1995; Mohr 1994; Paccagnella 1994; Rao 1991; Rentschler 1987; Richard 1991; Schuller 1988; Szabo 1999; Szpirglas 1978; Volling 1999; Weissler 1992) are now included in the chemotherapy review (Furness 2011), and three previously included trials are being considered for inclusion in the immunotherapy review, which is currently being prepared. One trial was excluded from this review because less than 50% of the participants had oral cavity or oropharyngeal cancer and their data could not be extracted separately (Hintz 1979a).

Risk of bias in included studies

Allocation

Four of the included trials reported adequate sequence generation methods (D'Cruz 2015; Fakih 1989; Mehanna 2017; Robertson 1998); in the remaining eight trials, the methods of sequence generation were unclear. Two trials reported adequate allocation concealment (Robertson 1998; Vandenbrouck 1980), but only one trial was assessed as being at low risk of bias in both of these domains (Robertson 1998).

Blinding

Blinding of participants and clinicians is not feasible in surgical trials, but blinding of outcome assessment is both possible and desirable. However, as mortality is the primary outcome that is most frequently and reliably reported, a decision was made to assess all trials as being at low risk of bias for this domain.

Incomplete outcome data

We assessed nine of the included trials at low risk of bias with regard to incomplete outcome data because all the randomised participants were adequately accounted for in the outcome evaluation (BHNCSG 1998; Guo 2014; Iyer 2015; Kligerman 1994; Mehanna 2017; Rastogi 2018; Robertson 1998; Vandenbrouck 1980; Yuen 2009). Of the remaining trials, we assessed two at high risk with regard to this domain (Bier 1994; Fakih 1989), and one at unclear (D'Cruz 2015). Both Bier 1994 and Fakih 1989 presented an interim analysis of a subgroup of participants and the final analysis has not been published as far as we are aware. In both of these trials, it was unclear how many participants were randomly allocated to each intervention group, and how many in each group were subsequently excluded from the analysis or analysed in a different group from that to which they were originally allocated (or both). It is likely that those excluded from the analysis (because they refused surgery or had extracapsular rupture during surgery) had a different outcome from those included in the analysis.

Selective reporting

We assessed 11 of the included trials as free of selective reporting bias as they reported on expected, clinically important outcomes. Yuen 2009 did not report total mortality or overall survival, so was at high risk of bias for this domain.

Other potential sources of bias

We assessed eight trials at low risk of other bias because the intervention groups appeared to be similar at baseline and there were no other sources of bias (BHNCSG 1998; D'Cruz 2015; Guo 2014; Iyer 2015; Mehanna 2017; Rastogi 2018; Vandenbrouck 1980; Yuen 2009).

Three trials provided no information regarding the baseline characteristics of participants in each group, and so these trials were at unclear risk of other bias (Bier 1994; Fakih 1989; Kligerman 1994).

We assessed Robertson 1998 at high risk of other bias because, although planned recruitment was 350 participants, this trial was stopped after only 35 participants were recruited because clinicians felt it was unethical to continue. While appropriate procedures were followed and an interim analysis was conducted and reported, it is not clear from this report whether a priori stopping rules were in place. Additionally, more than half of the participants in this trial did not receive radiotherapy as planned due to problems with faulty equipment. It is likely that this would have had a greater effect on the outcomes the of radiotherapy‐only arm of the trial.

Overall risk of bias

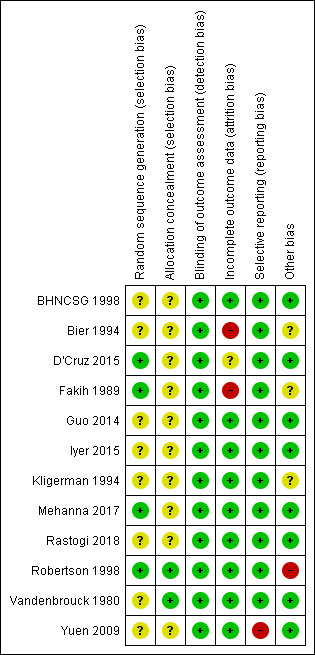

A summary of the 'Risk of bias' assessment is presented in Figure 2. Overall, we assessed four studies at high risk of bias (Bier 1994; Fakih 1989; Robertson 1998; Yuen 2009), and eight trials at unclear risk of bias (BHNCSG 1998; D'Cruz 2015; Guo 2014; Iyer 2015; Kligerman 1994; Mehanna 2017; Rastogi 2018; Vandenbrouck 1980), for all of the outcomes evaluated.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4; Table 5; Table 6; Table 7

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Elective neck dissection versus therapeutic (delayed) neck dissection.

| Elective neck dissection versus therapeutic (delayed) neck dissection | ||||||

|

Patient: adults with oral or oropharyngeal cancer Setting: inpatient Intervention: elective neck dissection Comparison: therapeutic (delayed) neck dissection | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Therapeutic neck dissection | Elective neck dissection | |||||

|

Total mortality (follow‐up: 3 years) |

500a per 1000 | 441 per 1000 (247 to 696) |

HR 0.84 (0.41 to 1.72) |

571 (2) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowb,c,d | These data were from the HR for overall survival. Other binary data from 2 trials could not be pooled. 1 trial indicated no clear evidence of either intervention leading to lower mortality; however, 1 small trial indicated elective neck dissection led to lower mortality (RR 0.40, 95% CI 0.19 to 0.84) (very low‐certainty evidence). |

|

New disease, progression or mortality (follow‐up: 3 years) |

500e per 1000 | 397.1 per 1000 (159 to 768) |

HR 0.73 (0.25 to 2.11) |

571 (2) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowb,c | These data were from the HR for disease‐free survival. Binary data from 2 trials did not favour either intervention. 1 trial provided some very low‐certainty evidence for elective SOH leading to lower mortality (HR 0.32, 95% CI 0.12 to 0.84). |

| 250e per 1000 | 190 per 1000 (69 to 455) | |||||

| Locoregional recurrence | — | — | — | 278 (4) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowc,f | Binary data; unable to pool data (different timings). Three studies were inconclusive and one favoured elective procedure. |

| Recurrence | — | — | — | 0 (0) |

— | No data presented |

| Adverse events | 1 study showed that 6.6% of elective‐surgery participants reported adverse events, while 3.6% of participants in therapeutic‐surgery group reported adverse events. These adverse events included: neck haematoma, chyle leak, oral bleeding, postoperative infection and anaphylaxis. None of the other trials reported on adverse events. | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; HR: hazard ratio; RR: risk ratio; SOH: supraomohyoid neck dissection. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aBased on data presented by Warnakulasuriya 2009.

bDowngraded once as two trials at unclear risk of bias.

cDowngraded twice for imprecision.

dDowngraded once for heterogeneity.

ePurely illustrative, unable to find any epidemiological estimates.

fDowngraded once for study design; four heterogeneous trials, two at high risk of bias and two at unclear risk of bias.

Summary of findings 2. Elective radical neck dissection versus elective selective neck dissection.

| Radical neck dissection versus selective neck dissection | ||||||

|

Patient: adults with oral or oropharyngeal cancer Setting: inpatient Intervention: elective radical neck dissection Comparison: elective selective neck dissection | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Selective neck dissection | Radical neck dissection | |||||

| Total mortality | — | — | — | 252 (2) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b |

HR from 2 trials, but unable to pool data as different surgical procedures. Neither trial indicated that mortality was different for the 2 interventions. |

|

New disease, progression or mortality (follow‐up: 5 years) |

500c per 1000 | 326 per 1000 (182 to 537) |

HR 0.57 (0.29 to 1.11) |

104 (1) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowb,d | These data were from the HR for disease‐free survival. 1 study, indicating no difference between the interventions. |

| 250c per 1000 | 151 per 1000 (80 to 273) | |||||

| Locoregional recurrence | — | — | — | — | — | Not reported |

|

Recurrence (5 years) |

180e per 1000 | 213 per 1000 (118 to 370) |

RR 1.21 (0.63 to 2.33) |

143 (1) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowb,f,g | 1 study, indicating no difference between the interventions. |

| Adverse events | 1 trial reported the following adverse effects: flap necrosis, wound infection, fistula, vascular rupture, haematoma, seroma and chyle fistula. There were 0 complications in 45 participants (59%) in the modified radical neck dissection group and 0 in 54 participants (75%) in the supraomohyoid neck dissection group. There were 2 postoperative deaths in the modified radical neck dissection group and 1 in the supraomohyoid neck dissection group. The other studies did not report adverse events | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; HR: hazard ratio; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded twice, two heterogeneous studies at unclear and high risk of bias.

bDowngraded once for imprecision.

cPurely illustrative, unable to find any epidemiological estimates.

dDowngraded twice as single study at high risk of bias.

eEstimated from BHNCSG 1998.

fSDowngraded once as single study at unclear risk of bias.

g Downgraded twice for imprecision

Summary of findings 3. Surgery plus radiotherapy versus radiotherapy alone.

| Surgery plus radiotherapy versus radiotherapy alone | ||||||

|

Patient: adults with oral or oropharyngeal cancer Setting: inpatient Intervention: surgery + radiotherapy Comparison: radiotherapy alone | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Radiotherapy alone | Surgery + radiotherapy | |||||

|

Total mortality (follow‐up: 3 years) |

500 per 1000 | 153 per 1000 (67 to 336) |

HR 0.24 (0.10 to 0.59) |

35 (1) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa | These data were from the HR for overall survival. 1 study, result favouring the surgery group; however, data were unreliable because trial stopped early and there were multiple protocol violations. |

| Disease‐free survival | — | — | — | — | — | Not reported |

| Locoregional recurrence | — | — | — | — | — | Not reported |

| Recurrence | — | — | — | — | — | Not reported |

| Adverse events | Both groups reported the following severe acute adverse effects: subcutaneous fibrosis, telangiectasia (1–4 cm²), and moderate‐to‐severe oedema, xerostomia, trismus and dysphagia. Subcutaneous fibrosis was reported as more prevalent in the surgery + radiotherapy group (P = 0.042), but the prevalence of other adverse effects appeared to be similar in each group. | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; HR: hazard ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded three levels as high risk of bias, interim analysis of 35 participants after 23 months.

Summary of findings 4. PET‐CT following chemoradiotherapy versus planned neck dissection either before or after chemoradiotherapy.

| PET‐CT following chemoradiotherapy versus planned neck dissection either before or after chemoradiotherapy | ||||||

|

Patient: adults with oral or oropharyngeal cancer Setting: inpatient Intervention: PET‐CT following chemoradiotherapy Comparison: planned neck dissection either before or after chemoradiotherapy | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Planned neck dissection | PET‐CT | |||||

|

Total mortality (follow‐up: 2 years) |

500 per 1000 | 471 per 1000 (363 to 597) |

HR 0.92 (0.65 to 1.31) |

564 (1) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b | These data were from the HR for overall survival. 1 study, no evidence of a difference in mortality |

| Disease‐free survival | — | — | — | — | — | Outcome not reported in a usable way. |

| Locoregional recurrence | — | — | — | — | — | Outcome not reported in a usable way. |

| Recurrence | — | — | — | — | — | Outcome not reported in a usable way. |

| Adverse events | 22 surgical complications in PET‐CT group compared with 83 in planned surgery group. | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; HR: hazard ratio; PET‐CT: positron‐emission tomography–computed tomography. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded once as one study at unclear risk of bias.

bDowngraded twice for imprecision.

Summary of findings 5. Surgery plus adjuvant radiotherapy versus chemotherapy.

| Surgery plus adjuvant radiotherapy versus chemotherapy | |||||||

|

Patient: adults with oral or oropharyngeal cancer Setting: inpatient Intervention: surgery + adjuvant radiotherapy Comparison: chemotherapy |

|||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | ||

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | ||||||

| Chemotherapy | Surgery + adjuvant radiotherapy | ||||||

|

Total mortality (follow‐up: 2 years) |

— | — | — | — | — | 1 study report stated, "For the oral cavity, survival was significantly better in patients who underwent surgery and RT compared with the CRT [chemoradiotherapy] group." However, there were no useable data. | |

| Disease‐free survival | — | — | — | — | — | Reported as statistically significant in favour of the surgery group (P = 0.038), but there were no useable data. | |

| Locoregional recurrence | — | — | — | — | — | Reported as not statistically significant between groups (P = 0.355), but there were no useable data. | |

|

Recurrence (5 years) |

— | — | — | — | — | Reported as not statistically significant between the groups, but there were no useable data. | |

| Adverse events | — | — | — | — | — | Not reported | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval. |

|||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||||||

Summary of findings 6. Supraomohyoid neck dissection versus modified radical neck dissection.

| Supraomohyoid neck dissection versus modified radical neck dissection | ||||||

|

Patient: adults with oral or oropharyngeal cancer Setting: inpatient Intervention: supraomohyoid neck dissection Comparison: modified radical neck dissection | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Modified radical neck dissection | Supraomohyoid neck dissection | |||||

|

Total mortality (follow‐up: 2 years) |

— | — | — | — | — | 1 study, unable to use the data. |

| Disease‐free survival | — | — | — | — | — | Outcome not reported in a usable way. |

| Locoregional recurrence | — | — | — | — | — | Outcome not reported in a usable way. |

|

Recurrence (5 years) |

— | — | — | — | — | Outcome not reported in a usable way. |

| Adverse events | Significant difference in complication rates with lower rates for supraomohyoid procedure. UW‐QOL scores for all disease‐free survivors were assessed at 1 year after treatment. Scores from 9 disease‐specific domains appeared to show that supraomohyoid neck dissection was superior to modified radical neck dissection in the domains of pain relief (78.8% vs 75.2%, P = 0.013) and shoulder function (81.1% vs 68.1%, P < 0.001), but not in any of the other domains. |

|||||

|

GRADE Working Group grades of evidence

High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect.

Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different.

Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect.

Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. CI: confidence interval; UW‐QOL: University of Washington Quality of Life Questionnaire. | ||||||

Summary of findings 7. Super‐selective neck dissection versus selective neck dissection.

| Super‐selective neck dissection versus selective neck dissection | ||||||

|

Patient: adults with oral or oropharyngeal cancer Setting: inpatient Intervention: super‐selective neck dissection Comparison: selective neck dissection | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Selective neck dissection | Super‐selective neck dissection | |||||

|

Total mortality (follow‐up: 2 years) |

— | — | — | — | — | Outcome not reported |

| Disease‐free survival | — | — | — | — | — | Outcome not reported |

| Locoregional recurrence | — | — | — | — | — | Data not presented in a useable way. Report concluded that super‐selective procedure showed a lower rate of recurrence. |

|

Recurrence (5 years) |

— | — | — | — | — | Outcome not reported in a usable way. |

| Adverse events | Shoulder morbidity data indicated improvement for super‐selective group, as well as better quality of life. | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

Comparison 1: elective neck dissection versus therapeutic (delayed) neck dissection

See Table 1.

Five trials compared the timing of the neck dissection; either at the same time as resection of the primary tumour or as a separate procedure subsequent to resection of the primary, with dissection of the neck nodes being undertaken only after there was clinical evidence of disease in the neck nodes (D'Cruz 2015; Fakih 1989; Kligerman 1994; Vandenbrouck 1980; Yuen 2009). All participants had oral cavity cancers, specifically tongue or floor of mouth tumours and clinically negative neck nodes on study entry.

Fakih 1989 and Vandenbrouck 1980 performed classical RND procedures and pooled data after one year (Fakih 1989) and three years (Vandenbrouck 1980) of follow‐up. D'Cruz 2015 and Yuen 2009 performed selective neck dissection of level I to III nodes with D'Cruz 2015 reporting data at three years. Kligerman 1994 used a SOH elective neck dissection procedure, and reported data after 3.5 years of follow‐up. Fakih 1989 and Yuen 2009 was at overall high risk of bias and Kligerman 1994, Vandenbrouck 1980, and D'Cruz 2015 were at unclear overall risk of bias.

Overall survival (or total mortality)

Two trials presented overall survival data as HRs (D'Cruz 2015; Vandenbrouck 1980) and two trials as RRs (Fakih 1989 at one year; Vandenbrouck 1980 at three years). The meta‐analysis for the HRs showed no evidence of a difference between the interventions (Analysis 1.1; very low‐certainty evidence)). We were unable to pool the binary data due to different follow‐up periods. Fakih 1989 found no evidence of a difference between elective RND and therapeutic neck dissection at one‐year follow‐up (very low‐certainty evidence); however, Kligerman 1994, where elective surgery was the less extensive SOH, found a difference in overall survival after 3.5 years of follow‐up, favouring elective SOH neck dissection compared to therapeutic neck dissection (Analysis 1.2; very low‐certainty evidence).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Elective neck dissection (ND) versus therapeutic (delayed) neck dissection, Outcome 1 Total mortality (HR for overall survival).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Elective neck dissection (ND) versus therapeutic (delayed) neck dissection, Outcome 2 Total mortality.

Disease‐free survival (or new disease, progression and mortality)

Three trials reported the data for disease‐free survival as HRs (D'Cruz 2015; Kligerman 1994; Vandenbrouck 1980), and two trials as RRs (Fakih 1989 at one year; Vandenbrouck 1980 at three years). The pooled HR showed no evidence of a difference between elective neck dissection and therapeutic neck dissection (HR 0.73, 95% CI 0.25 to 2.11; Analysis 1.3; very low‐certainty evidence). One study provided very low‐certainty evidence of a benefit from elective SOH neck dissection when compared to therapeutic neck dissection (HR 0.32, 95% CI 0.12 to 0.84; Analysis 1.3) (Kligerman 1994). The binary data showed no evidence of a difference between the interventions (Analysis 1.4; very low‐certainty evidence).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Elective neck dissection (ND) versus therapeutic (delayed) neck dissection, Outcome 3 New disease, progression or mortality (HR for disease‐free survival).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Elective neck dissection (ND) versus therapeutic (delayed) neck dissection, Outcome 4 New disease, progression or mortality.

Locoregional recurrence

Four trials reported binary data on locoregional recurrence (D'Cruz 2015; Fakih 1989; Kligerman 1994; Vandenbrouck 1980), but the data were not suitable for meta‐analysis due to the differences between studies in the type of surgery and the duration of follow‐up (Analysis 1.5; very low‐certainty evidence). The results were mixed, with three trials suggesting neither intervention was superior, while the study evaluating elective SOH neck dissection concluding this approach may reduce locoregional recurrence more than therapeutic delayed ND.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Elective neck dissection (ND) versus therapeutic (delayed) neck dissection, Outcome 5 Locoregional recurrence.

Recurrence

Two trials reported recurrence rates at different sites, but numbers were too small to determine whether there may have been a difference between the groups in rate of recurrence of either a second primary tumour or distant metastases (data not shown) (Vandenbrouck 1980; Yuen 2009).

Secondary outcomes

In D'Cruz 2015, 6.6% of the elective‐surgery participants showed adverse events, while 3.6% of participants in the therapeutic‐surgery group reported adverse events. These included neck haematoma, chyle leak, oral bleeding, postoperative infection and anaphylaxis. None of the other trials reported on adverse events.

None of the trials reported on quality of life, costs or any measure of participant satisfaction.

Comparison 2: elective radical neck dissection versus elective selective neck dissection

See Table 2.

Two trials compared neck dissection surgery of differing extent (BHNCSG 1998; Bier 1994). There were differences between the two studies with regard to participant characteristics at baseline and surgical procedures so meta‐analysis was not undertaken.

BHNCSG 1998 compared a modified classical neck dissection procedure with accessory nerve preservation, to a SOH neck dissection to achieve a compartmental excision of levels I to III neck nodes in 148 participants with T2 to T4 primary lesions in the oral cavity and clinically negative nodes. Frozen sections were carried out on the nodes during surgery and three participants in the SOH group who had histologically positive nodes then underwent the modified classical neck dissection instead. This trial was at overall unclear risk of bias.

In Bier 1994, 104 participants with either clinically negative or positive but movable neck nodes were randomised to either RND or a selective neck dissection where the platysma, sternocleidomastoid muscle, internal jugular vein and accessory nerve were left in place. Primary tumours were in the oral cavity and the study was at overall high risk of bias.

Overall survival (or total mortality)

There was no evidence of a difference in overall survival (Analysis 2.1; very low‐certainty evidence).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Radical neck dissection (ND) versus selective neck dissection, Outcome 1 Total mortality (HR for overall survival).

Disease‐free survival (or new disease, progression and mortality)

Only Bier 1994 reported disease‐free survival and there was no evidence of a difference (Analysis 2.2; very low‐certainty evidence).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Radical neck dissection (ND) versus selective neck dissection, Outcome 2 New disease, progression or mortality (HR for disease‐free survival).

Locoregional recurrence

Neither trial reported locoregional recurrence.

Recurrence

Only BHNCSG 1998 reported recurrence as binary data at five years, and there was no evidence of a difference in disease recurrence (Analysis 2.3; very low‐certainty evidence).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Radical neck dissection (ND) versus selective neck dissection, Outcome 3 Recurrence.

Secondary outcomes

BHNCSG 1998 reported the following adverse effects: flap necrosis, wound infection, fistula, vascular rupture, haematoma, seroma and chyle fistula. There were no complications in 45/76 participants in the modified RND group and none in 54/72 participants in the SOH neck dissection group. There were two postoperative deaths in the modified RND group and one in the SOH neck dissection group.

Neither trial reported other secondary outcomes.

Comparison 3: surgery plus radiotherapy versus radiotherapy alone

See Table 3.

One trial compared surgery plus postoperative radiotherapy with radiotherapy alone (Robertson 1998). Participants in the surgery group had wide local excision of the primary tumour together with either a RND or a more selective neck dissection at the discretion of the surgeon. It was planned to accrue 175 participants, with oral cavity or oropharyngeal cancer (neck nodes clinically staged as N0 to 2) to each arm of the trial but after 35 participants had been recruited the trial was stopped due to the high death rate in the radiotherapy alone arm.

Overall survival (or total mortality)

Data in Analysis 3.1 are from an interim analysis of 35 participants after 23 months and showed an HR for total mortality of 0.24 (95% CI 0.10 to 0.59), favouring the surgery group. This estimate should be interpreted with extreme caution for several reasons. The authors stated that "the difference in survival is likely to be inflated" due to the small number of participants in the analysis, the fact that only 41% of participants in the radiotherapy only arm received their radiotherapy as planned due to problems with faulty machines, and that there were several other protocol violations in the trial. In the surgery plus radiotherapy arm, 50% of the participants received radiotherapy as planned, but 12% of participants received neither surgery to the mandible nor neck dissection.

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Surgery plus radiotherapy (RT) versus radiotherapy alone, Outcome 1 Total mortality (HR for overall survival).

Disease‐free survival (or new disease, progression and mortality)

The trial did not report this outcome.

Locoregional recurrence

The trial did not report locoregional recurrence.

Recurrence

The trial did not report recurrence.

Secondary outcomes

There were the following severe acute adverse effects in both groups (Robertson 1998): subcutaneous fibrosis, telangiectasia (1 cm² to 4 cm²), and moderate to severe oedema, xerostomia, trismus and dysphagia. Subcutaneous fibrosis was more prevalent in the surgery plus radiotherapy group (P = 0.042), but the prevalence of other adverse effects appeared to be similar in each group.

The trial did not report other secondary outcomes.

Comparison 4: PET‐CT following chemoradiotherapy versus planned neck dissection either before or after chemoradiotherapy

See Table 4.