Abstract

Objectives

To determine whether progressive skin fibrosis is associated with visceral organ progression and mortality during follow-up in patients with diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis (dcSSc).

Methods

We evaluated patients from the European Scleroderma Trials and Research database with dcSSc, baseline modified Rodnan skin score (mRSS) ≥7, valid mRSS at 12±3 months after baseline and ≥1 annual follow-up visit. Progressive skin fibrosis was defined as an increase in mRSS >5 and ≥25% from baseline to 12±3 months. Outcomes were pulmonary, cardiovascular and renal progression, and all-cause death. Associations between skin progression and outcomes were evaluated by Kaplan-Meier survival analysis and multivariable Cox regression.

Results

Of 1021 included patients, 78 (7.6%) had progressive skin fibrosis (skin progressors). Median follow-up was 3.4 years. Survival analyses indicated that skin progressors had a significantly higher probability of FVC decline ≥10% (53.6% vs 34.4%; p<0.001) and all-cause death (15.4% vs 7.3%; p=0.003) than non-progressors. These significant associations were also found in subgroup analyses of patients with either low baseline mRSS (≤22/51) or short disease duration (≤15 months). In multivariable analyses, skin progression within 1 year was independently associated with FVC decline ≥10% (HR 1.79, 95% CI 1.20 to 2.65) and all-cause death (HR 2.58, 95% CI 1.31 to 5.09).

Conclusions

Progressive skin fibrosis within 1 year is associated with decline in lung function and worse survival in dcSSc during follow-up. These results confirm mRSS as a surrogate marker in dcSSc, which will be helpful for cohort enrichment in future trials and risk stratification in clinical practice.

Keywords: diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis, progressive skin fibrosis, visceral organ progression, lung function decline, all-cause death

Key messages.

What is already known about this subject?

Recent evidence-based clinical trial design aimed at including patients with high risk for progression of skin fibrosis.

However, it is unclear, whether mRSS progression is an appropriate surrogate marker for new onset or deterioration of visceral organ disease and mortality in SSc.

What does this study add?

Using the large EUSTAR cohort, this study could show that mRSS progression within 1 year is associated with long-term lung deterioration, overall disease progression and all-cause mortality.

How might this impact on clinical practice?

Patients with short term progressive skin disease should be carefully monitored for other organ progression in the following years.

The results show that mRSS progression is an excellent surrogate marker for long-term disease progression in SSc, which supports the use of mRSS as an end point in clinical trials.

Introduction

Systemic sclerosis (SSc) is a highly heterogeneous connective tissue disease with major morbidity and mortality caused by the development of visceral organ complications. These include interstitial lung fibrosis, pulmonary arterial hypertension, scleroderma renal crisis (SRC), and cardiac and gastrointestinal involvement.1 A major challenge for physicians is to identify patients at high risk of future complications before irreversible visceral involvement occurs. With several new disease-modifying agents in late-stage development,2 improved identification of at-risk patients will become even more important to inform early treatment intervention. In addition, it will provide important information for cohort enrichment in future clinical trials.3

Skin fibrosis is a hallmark of SSc. The modified Rodnan skin score (mRSS) rates skin thickness from 0 (normal) to 3 (severe) at 17 body surface areas in a standardised manner.4 The mRSS is feasible, reliable and sensitive to change, and is now commonly used in routine practice and clinical trials.5–7

Using the European Scleroderma Trials and Research (EUSTAR) database, we previously identified short disease duration (≤15 months) and low baseline mRSS (≤22/51) as independent predictors of progressive skin fibrosis (defined as >5 units and ≥25% increment in mRSS at 1-year follow-up) in patients with diffuse cutaneous SSc (dcSSc).8 9 While this evidence-based strategy of including patients with dcSSc with low baseline mRSS can improve cohort enrichment for progressive skin fibrosis in clinical trials,10 it might lead to recruitment of patients with overall milder disease. Previous studies have suggested that mRSS may be a potential surrogate marker for disease severity and mortality, but these data were derived from older studies and/or selected patients from clinical trials (D-penicillamine).11 12 Therefore, new data are required to clarify whether worsening skin fibrosis is an appropriate surrogate marker for new onset or deterioration of visceral organ disease and overall survival in dcSSc.

In a previous single-centre retrospective study of patients with early dcSSc, patients with high baseline mRSS and no subsequent skin improvement within 2 years had significantly higher mortality than those with skin improvement irrespective of baseline mRSS, while the results for internal organ-based endpoints were contradictory.13 The study thus suggested the prognostic value of the evolution of skin fibrosis, in addition to absolute skin scores, in predicting disease outcome for patients with dcSSc. We herein hypothesise that progression of skin fibrosis within 1 year might be associated with progression of visceral organ disease and mortality in dcSSc during follow-up. The aim of the current study was to test this hypothesis in the large, systematic, longitudinal, real-life EUSTAR registry.

Methods

More details on methods can be found in the online supplement.

annrheumdis-2018-213455supp001.docx (19.4KB, docx)

Patients and study design

For this observational study, data from patients’ visits from 1 January 2009 to 31 August 2017 were exported from the EUSTAR database. The structure of the EUSTAR database and minimum essential dataset have been described previously.14 15

Inclusion criteria for the study were classification of SSc (1980 American College of Rheumatology criteria16), diffuse cutaneous involvement as described by LeRoy et al,17 at least one available annual follow-up visit, mRSS ≥7 (the minimal value for subclassification as dcSSc) at the first available visit (baseline) and valid mRSS data at 12±3 months after baseline.

Definition of ‘progressor’ patients

Patients with progression of skin fibrosis (skin progressors) were defined as those with an increase in mRSS >5 units and by ≥25% from baseline to 12±3 months. This mRSS threshold is considered as the minimally clinical important difference.18 The 1-year period to define skin progression was chosen as it is considered sufficient to capture significant changes in mRSS and is thus frequently used in clinical trials in skin fibrosis.19

Follow-up and outcome measures

Follow-up was defined as the time between the first available visit (baseline) and the last available annual follow-up for each patient. All outcome events were accounted during this period. Outcome measures reflecting visceral organ progression were defined by consensus of an expert group (YA, MM-C, JEP, CPD, DK and OD) using the nominal group technique. Organ progression was defined as occurrence of one of the following events during follow-up: (1) relative decrease in FVC ≥10% from baseline; (2) reduction of left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) to <45%, or relative decrease of LVEF >10% for patients with baseline LVEF <45%, assessed by echocardiography; (3) new-onset pulmonary hypertension (PH) as globally judged on echocardiography by the treating physician; (4) new-onset SRC; (5) all-cause death.20–23 Overall disease progression was defined as the presence of any of the above outcomes. In addition, an exploratory analysis in which lung progression was defined as a relative decrease from baseline to follow-up in FVC ≥10%, or 5%–9% combined with diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO) ≥15% (instead of definition 1), was performed based on recently proposed criteria.24

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics were described as mean (SD) for continuous variables and number (frequency) for categorical variables. Baseline variables were compared between skin progressors and non-progressors by univariate analysis followed by Bonferroni correction. Chi-squared tests or Fisher’s exact tests were used for categorical variables, and independent sample t-tests were used for continuous variables.

Kaplan-Meier curves and log-rank tests were performed to compare outcomes between skin progressors and non-progressors for up to 8 years of follow-up. Only the first event was considered. Patients with PH or SRC at baseline were excluded from analyses of PH and SRC outcomes, as these patients could not show any new event of these types. Kaplan-Meier analyses were also conducted in subgroups stratifying patients by either baseline mRSS (≤22/51 vs >22/51 units) or disease duration (≤15 vs >15 months). Multivariable Cox regression analyses were performed to examine independent associations between skin progression and both FVC decline ≥10% and all-cause death. Confounding variables for multivariable Cox regression models were selected using the nominal group technique. Spearman rho analyses were conducted to measure the correlation between variables before multivariable regression. Multiple imputation with 10 imputed datasets was used before regression analysis to handle missing values.

Significance was defined as p value <0.05. Statistical analyses were performed by the biostatistician (NG) using R programming language (V.3.3.3), packages ‘survival’ and ‘mice’.25–27

Results

Baseline characteristics

In total, 1021 patients were included for analysis, of whom 78 (7.6%) had progression of skin fibrosis at 1-year follow-up. Demographic and clinical characteristics are summarised in table 1. Mean age was 52.0 years, mean disease duration was 7.7 years and mean±SD mRSS was 16.9±7.7 at baseline. Median follow-up was 3.4 years. By using Bonferroni correction, the modified critical p value (α) was determined as 0.0013. Skin progressors had a significantly shorter disease duration at baseline than non-progressors, confirming previous results.8 9 All other baseline characteristics were comparable between groups (table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of skin progressors and non-progressors

| Characteristics | Missing cases, n (%) | Whole cohort (n=1021) | Progressors (n=78) | Non-progressors (n=943) | P value |

| Demographic | |||||

| Age, years (mean±SD) | 0 (0) | 52.0±13.7 | 51.7±12.9 | 52.0±13.7 | 0.869 |

| Male sex | 0 (0) | 248 (24.3) | 30 (38.5) | 218 (23.1) | 0.004 |

| Disease duration* years (mean±SD) | 78 (7.6) | 7.7±7.5 | 5.3±6.2 | 7.9±7.5 | 0.006 |

| ≤15 months | 78 (7.6) | 126 (13.4) | 19 (27.9) | 107 (12.2) | <0.001 |

| ≤36 months | 78 (7.6) | 298 (31.6) | 36 (52.9) | 262 (29.9) | <0.001 |

| Vascular | |||||

| Raynaud’s phenomenon | 2 (0.2) | 997 (97.8) | 74 (94.9) | 923 (98.1) | 0.141 |

| Digital ulcers | 11 (1.1) | 384 (38.0) | 30 (38.5) | 354 (38.0) | 1.000 |

| Active digital ulcers | 25 (2.4) | 199 (20.0) | 16 (21.1) | 183 (19.9) | 0.925 |

| Skin | |||||

| mRSS, unit (mean±SD) | 0 (0) | 16.9±7.7 | 14.8±6.2 | 17.1±7.7 | 0.010 |

| mRSS ≤22/51 | 0 (0) | 819 (80.2) | 67 (85.9) | 752 (79.7) | 0.245 |

| Musculoskeletal | |||||

| Tendon friction rubs | 11 (1.1) | 156 (15.4) | 10 (13.0) | 146 (15.6) | 0.648 |

| Joint synovitis | 6 (0.6) | 180 (17.7) | 16 (20.5) | 164 (17.5) | 0.607 |

| Joint contractures | 7 (0.7) | 505 (49.8) | 42 (53.8) | 463 (49.5) | 0.532 |

| Muscle weakness | 6 (0.6) | 255 (25.1) | 17 (22.1) | 238 (25.4) | 0.614 |

| Gastrointestinal | |||||

| Oesophageal symptoms | 1 (0.1) | 687 (67.4) | 51 (65.4) | 636 (67.5) | 0.795 |

| Stomach symptoms | 2 (0.2) | 300 (29.4) | 27 (34.6) | 273 (29.0) | 0.361 |

| Intestinal symptoms | 3 (0.3) | 281 (27.6) | 21 (26.9) | 260 (27.7) | 0.994 |

| Cardiopulmonary | |||||

| Dyspnoea (NYHA) | 84 (8.2) | 0.186 | |||

| Stage 1 | 520 (55.5) | 34 (51.5) | 486 (55.8) | ||

| Stage 2 | 315 (33.6) | 28 (42.4) | 287 (33.0) | ||

| Stage 3/4 | 102 (10.9) | 4 (6.1) | 98 (11.2) | ||

| Diastolic dysfunction | 150 (14.7) | 195 (22.4) | 12 (18.5) | 183 (22.7) | 0.526 |

| Pericardial effusion | 215 (21.1) | 59 (7.3) | 7 (12.1) | 52 (7.0) | 0.238 |

| Conduction blocks | 124 (12.1) | 123 (13.7) | 6 (8.8) | 117 (14.1) | 0.300 |

| LVEF <45% | 266 (26.1) | 16 (2.1) | 2 (3.4) | 14 (2.0) | 0.797 |

| Pulmonary hypertension byechocardiography† | 138 (13.5) | 120 (13.6) | 11 (16.7) | 109 (13.3) | 0.568 |

| Lung fibrosis on CT scan | 351 (34.4) | 403 (60.1) | 33 (60.0) | 370 (60.2) | 1.000 |

| FVC, % predicted (mean±SD) | 168 (16.5) | 87.0±20.7 | 86.6±17.5 | 87.0±20.9 | 0.879 |

| FVC <70% predicted | 168 (16.5) | 182 (21.3) | 13 (21.7) | 169 (21.3) | 1.000 |

| FEV1, % predicted (mean±SD) | 272 (26.6) | 85.7±18.4 | 87.2±16.5 | 85.6±18.6 | 0.547 |

| TLC, % predicted (mean±SD) | 427 (41.8) | 86.6±20.6 | 86.5±15.3 | 86.6±20.9 | 0.991 |

| DLCO, % predicted (mean±SD) | 179 (17.5) | 65.6±19.3 | 65.6±17.2 | 65.6±19.4 | 0.995 |

| DLCO <70% predicted | 179 (17.5) | 479 (56.9) | 33 (57.9) | 446 (56.8) | 0.984 |

| Kidney | |||||

| Renal crisis history | 4 (0.4) | 30 (2.9) | 2 (2.6) | 28 (3.0) | 1.000 |

| Laboratory parameters | |||||

| ANA positive | 16 (1.6) | 961 (95.6) | 75 (96.2) | 886 (95.6) | 1.000 |

| ACA positive | 64 (6.3) | 88 (9.2) | 6 (8.2) | 82 (9.3) | 0.929 |

| Anti-Scl-70 positive | 42 (4.1) | 616 (62.9) | 49 (66.2) | 567 (62.7) | 0.628 |

| Anti-U1RNP positive | 237 (23.2) | 35 (4.5) | 1 (1.6) | 34 (4.7) | 0.514 |

| Anti-RNA polymerase III positive | 453 (44.4) | 58 (10.2) | 5 (9.8) | 53 (10.3) | 1.000 |

| Creatinine kinase elevation | 75 (7.3) | 100 (10.6) | 8 (10.8) | 92 (10.6) | 1.000 |

| Proteinuria | 78 (7.6) | 64 (6.8) | 5 (6.9) | 59 (6.8) | 1.000 |

| Hypocomplementaemia | 192 (18.8) | 58 (7.0) | 3 (4.8) | 55 (7.2) | 0.613 |

| ESR >25 mm/h | 117 (11.5) | 371 (41.0) | 24 (35.3) | 347 (41.5) | 0.382 |

| CRP elevation | 63 (6.2) | 294 (30.7) | 31 (41.9) | 263 (29.8) | 0.041 |

| Active disease (VAI >3)‡ | 154 (15.1) | 340 (39.2) | 20 (30.8) | 320 (39.9) | 0.187 |

| Immunosuppressive therapy§ | 66 (6.5) | 667 (69.8) | 54 (73.0) | 613 (69.6) | 0.632 |

Definitions of items and organ manifestation are according to EUSTAR.14

Data are presented as number (%) unless otherwise stated.

P values of univariate comparisons of baseline characteristics between skin progressors and non-progressors are shown (χ2 tests or Fisher’s exact tests used for categorical variables and independent sample t-tests used for continuous variables, as appropriate).

*Disease duration was calculated as the difference between the date of the baseline visit and the date of the first non-Raynaud’s symptom of the disease as reported by the patient.

†Pulmonary hypertension was globally judged on echocardiography by the treating physician.

‡Active disease was defined as a score >3 by calculating European Scleroderma Study Group disease activity indices for systemic sclerosis proposed by Valentini et al.45

§Immunosuppressive therapy was defined as treatment with corticosteroids (prednisone dose ≥2.5 mg/day or other dosage forms in equal dose) or any immunosuppressant.

ACA, anti-centromere antibody;ANA, antinuclear antibody;Anti-Scl-70, anti-topoisomerase 1 antibody;CRP, C reactive protein;CT, computed tomography; DLCO, diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide;ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 sec; FVC, forced vital capacity; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; mRSS, modified Rodnan skin score. NYHA, New York Heart Association;TLC, total lung capacity;VAI, Valentini activity index;

Associations between skin progression and visceral organ progression

Lung progression

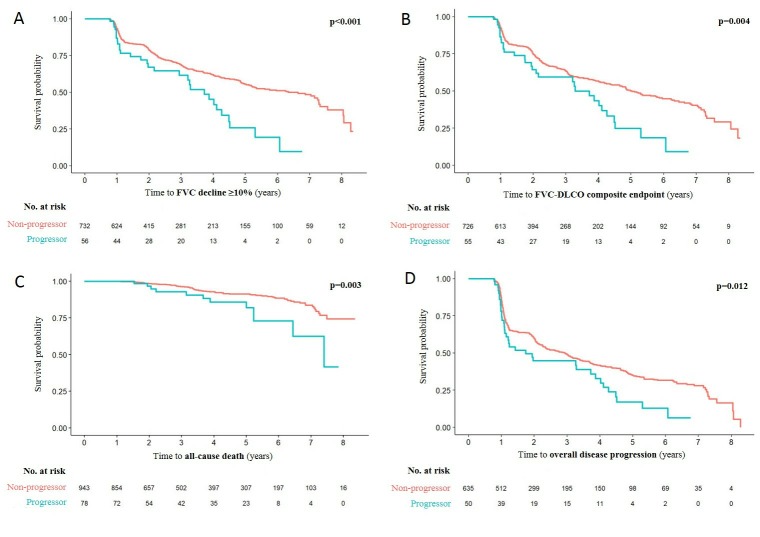

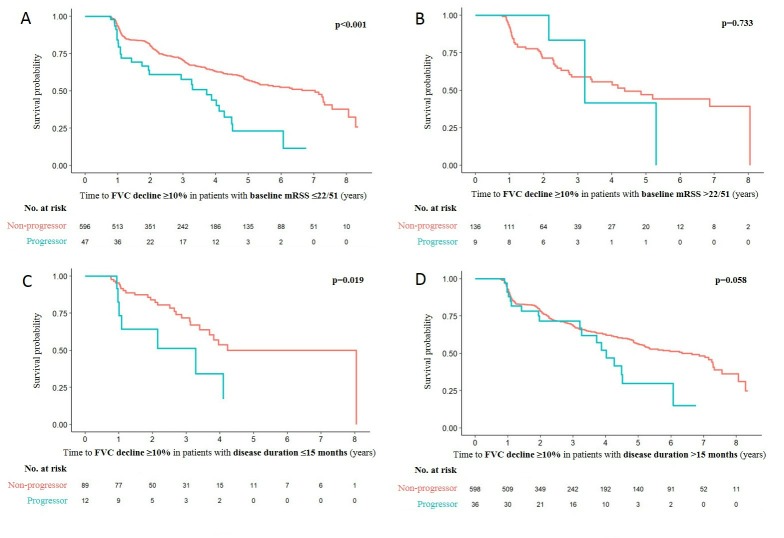

In total, 282 of 788 patients (35.8%) met the FVC definition of lung progression (relative decrease in FVC ≥10%) during a median follow-up of 3.7 years (IQR 1.8–6.2 years). In the overall cohort, 403 of 670 patients (60.1%) had lung fibrosis on CT scan at baseline. The mean±SD FVC at baseline was 86.9%±20.5%, with 164 patients (20.8%) having a baseline FVC <70%. There were 30 (53.6%) and 252 (34.4%) events in the skin progressor and non-progressor groups, respectively. The probability of FVC decline was significantly higher for skin progressors than non-progressors (log-rank test p<0.001; figure 1A). In the subgroups of patients with low baseline mRSS and short disease duration, which reflect evidence-based recruitment parameters for recent clinical trials in skin fibrosis,8 skin progressors also had a significantly higher probability of FVC decline than non-progressors (baseline mRSS ≤22/51 units: 27/47 [57.4%] vs 202/596 [33.9%], p<0.001; disease duration ≤15 months: 7/12 [58.3%] vs 26/89 [29.2%], p=0.019, respectively) (figure 2A, C). There was no significant difference in the probability of FVC decline in the subgroups of patients with baseline mRSS >22/51 units and disease duration >15 months (figure 2B, D).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier survival plots for (A) time to FVC decline ≥10%, (B) time to FVC-DCLO composite endpoint, (C) time to all-cause death and (D) time to overall disease progression during follow-up depending on the presence or absence of skin progression within 1 year. DLCO, diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide; FVC, forced vital capacity.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival plots for FVC decline ≥10% during follow-up depending on the presence or absence of skin progression within 1 year in subgroups of patients with (A) baseline mRSS ≤22/51 units, (B) baseline mRSS >22/51 units, (C) disease duration ≤15 months and (D) disease duration >15 months. FVC, forced vital capacity; mRSS, modified Rodnan skin score.

Overall, 320 of 781 patients (41.0%) met the FVC-DLCO composite definition of lung progression (relative decrease in FVC ≥10%, or 5%–9% combined with DLCO ≥15%) during a median follow-up of 3.9 years (IQR 1.9–6.2 years). There were 31 (56.4%) and 289 (39.8%) events in the skin progressor and non-progressor groups, respectively. Again the probability of FVC-DLCO decline was significantly higher for skin progressors than non-progressors (log-rank test p=0.004; figure 1B). In the subgroup of patients with low baseline mRSS, skin progressors also had a significantly higher probability of FVC-DLCO decline than non-progressors (27/47 [57.5%] vs 237/590 [40.2%]; p=0.002). In patients with short disease duration, skin progressors had a trend towards higher probability of FVC-DLCO decline than non-progressors (7/11 [63.6%] vs 29/89 [32.6%]; p=0.050). In the subgroups of patients with baseline mRSS >22/51 units and disease duration >15 months, no significant difference was seen in the probability of FVC-DLCO decline between groups (online supplementary figure S1).

Systolic heart dysfunction and SRC

Despite the large patient cohort, a low number of systolic heart dysfunction and SRC events occurred, limiting interpretation of the data.

During a median follow-up of 3.2 years (IQR 1.3–5.5 years), 15 of 662 patients (2.3%) cumulatively had an LVEF reduction. There were 3 (6.3%) and 12 (2.0%) events in the skin progressor and non-progressor groups, respectively. The probability of LVEF reduction was significantly higher for skin progressors than non-progressors (log-rank test p=0.038; online supplementary figure S2A). However, there was no significant difference in the probability of LVEF reduction between patients with and without skin progression in any subgroup when stratified by either baseline mRSS or disease duration.

During a median follow-up of 3.1 years (IQR 1.6–5.6 years), 21 of 985 patients (2.1%) cumulatively had a new SRC. There were 0 (0.0%) and 21 (2.3%) events in the skin progressor and non-progressor groups, respectively, and no significant difference in the probability of a new SRC between groups (log-rank test p=0.196; online supplementary figure 1). When stratified by either baseline mRSS or disease duration, no significant difference in the probability of a new SRC was observed between patients with and without skin progression in any subgroup.

Pulmonary hypertension

During a median follow-up of 3.8 years (IQR 1.9–5.8 years), 109 of 693 patients (15.7%) developed new PH. There were 5 (10.4%) and 104 (16.1%) events in the skin progressor and non-progressor groups, respectively, with no significant difference in probability of new PH between groups (log-rank test p=0.316; online supplementary figure S2C). When stratified by either baseline mRSS or disease duration, the only significant difference in probability of new PH between groups occurred in patients with disease duration >15 months, in whom skin progressors had a significantly lower probability of new PH compared with non-progressors (0/28 [0.0%] vs 89/528 [16.9%], respectively; p=0.026).

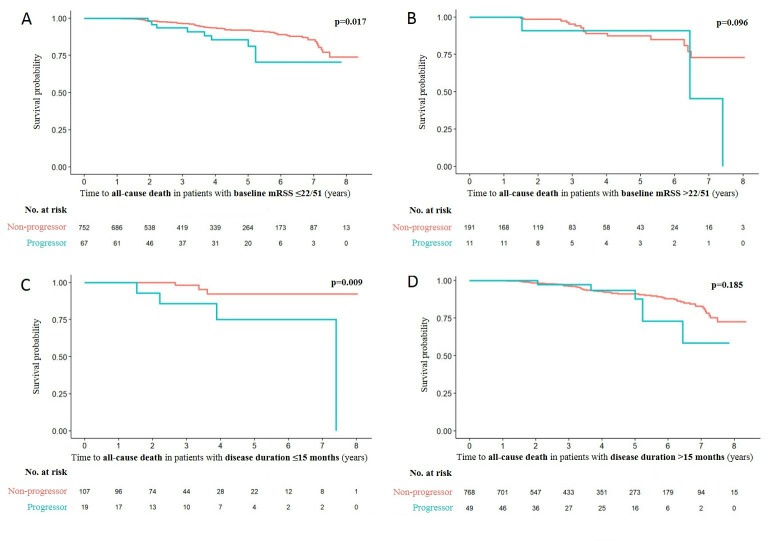

All-cause death

During a median follow-up of 3.4 years (IQR 1.8–5.9 years), 81 of 1021 patients (7.9%) died. There were 12 (15.4%) and 69 (7.3%) deaths in the skin progressor and non-progressor groups, respectively. The probability of all-cause death was significantly higher for skin progressors than non-progressors (log-rank test p=0.003; figure 1C). In the subgroups of patients with low baseline mRSS and short disease duration, skin progressors also had a significantly higher probability of all-cause death than non-progressors (baseline mRSS ≤22/51 units: 9/67 [13.4%] vs 54/752 [7.2%], p=0.017; disease duration ≤15 months: 4/19 [21.1%] vs 3/107 [2.8%], p=0.009, respectively) (figure 3A, C). In the subgroups of patients with baseline mRSS >22/51 units and disease duration >15 months, there was no significant difference in probability of all-cause death between groups (figure 3B, D).

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier survival plots for all-cause death during follow-up depending on the presence or absence of skin progression within 1 year in subgroups of patients with (A) baseline mRSS ≤22/51 units, (B) baseline mRSS >22/51 units, (C) disease duration ≤15 months and (D) disease duration >15 months. mRSS, modified Rodnan skin score.

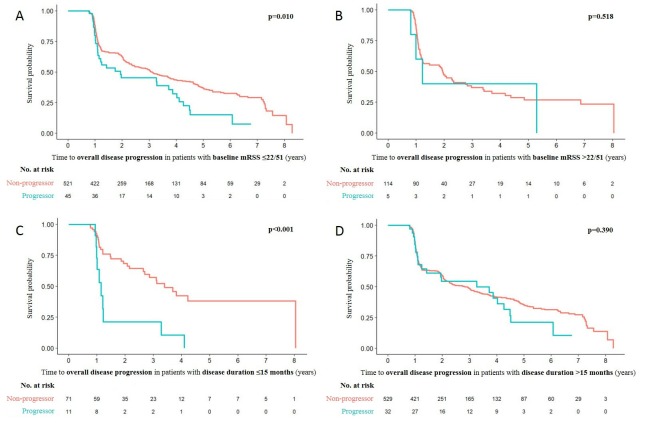

Overall disease progression

During a median follow-up of 4.6 years (IQR 2.2–6.6 years), 389 of 685 patients (56.8%) cumulatively had overall disease progression as defined above. There were 37 (74.0%) and 352 (55.4%) events in the skin progressor and non-progressor groups, respectively. The probability of overall disease progression was significantly higher for patients with skin progression than those without (log-rank test p=0.012; figure 1D). In the subgroups of patients with low baseline mRSS and short disease duration, skin progressors also had a significantly higher probability of overall disease progression than non-progressors (baseline mRSS ≤22/51 units: 33/45 [73.3%] vs 283/521 [54.3%], p=0.010; disease duration ≤15 months: 10/11 [90.9%] vs 31/71 [43.7%], p<0.001, respectively) (figure 4A, C). In the subgroups of patients with baseline mRSS >22/51 units and disease duration >15 months, no significant difference was observed in the probability of overall disease progression between groups (figure 4B, D).

Figure 4.

Kaplan-Meier survival plots for overall disease progression during follow-up depending on the presence or absence of skin progression within 1 year in subgroups of patients with (A) baseline mRSS ≤22/51 units, (B) baseline mRSS >22/51 units, (C) disease duration ≤15 months and (D) disease duration >15 months. mRSS, modified Rodnan skin score.

Independent associations between skin progression and FVC decline and all-cause death

In the final multivariable Cox regression models, skin progression was independently associated with FVC decline ≥10% (HR 1.79; 95% CI 1.20 to 2.65; p=0.004) and all-cause death (HR 2.58; 95% CI 1.31 to 5.09; p=0.006). History of SRC, LVEF <45%, FVC <70%, DLCO <70% and age at baseline were also independently associated with all-cause death (table 2). Skin progression had a trend-towards association with overall disease progression (HR 1.40; 95% CI 0.98 to 1.99; p=0.063) (online supplementary table S1).

Table 2.

Independent factors associated with FVC decline ≥10% and all-cause death as determined by multivariable Cox regression

| Baseline characteristics | HR (95% CI) |

| FVC decline ≥10% | |

| Skin progression | 1.79 (1.20 to 2.65) |

| Age | 1.00 (0.99 to 1.01) |

| Male sex | 0.89 (0.67 to 1.19) |

| mRSS | 1.01 (0.99 to 1.03) |

| Disease duration | 1.00 (0.99 to 1.00) |

| Lung fibrosis on CT scan | 1.25 (0.90 to 1.72) |

| Pulmonary hypertension by echocardiography | 1.31 (0.93 to 1.85) |

| Dyspnoea NYHA stage ≥2 | 1.23 (0.94 to 1.62) |

| Joint synovitis | 1.10 (0.81 to 1.49) |

| FVC <70% predicted | 0.89 (0.64 to 1.24) |

| DLCO <70% predicted | 1.28 (0.97 to 1.69) |

| Anti-Scl-70 positive | 0.99 (0.75 to 1.29) |

| ACA positive | 1.07 (0.69 to 1.66) |

| CRP elevation | 1.22 (0.92 to 1.60) |

| All-cause death | |

| Skin progression | 2.58 (1.31 to 5.09) |

| Age | 1.05 (1.03 to 1.07) |

| Male sex | 1.56 (0.95 to 2.57) |

| Lung fibrosis on CT scan | 1.68 (0.84 to 3.36) |

| Pulmonary hypertension by echocardiography | 0.84 (0.47 to 1.50) |

| Renal crisis history | 3.15 (1.18 to 8.43) |

| Digital ulcers | 1.58 (0.99 to 2.53) |

| Proteinuria | 1.50 (0.74 to 3.04) |

| LVEF < 45% | 3.51 (1.22 to 10.12) |

| FVC <70% predicted | 2.60 (1.49 to 4.55) |

| DLCO <70% predicted | 2.00 (1.04 to 3.84) |

Factors highlighted in bold are significantly associated with the outcome.

Skin progression is defined as an increase in mRSS >5 and ≥25% from baseline to 12±3 months later.

ACA, anti-centromere antibody;Anti-Scl-70, anti-topoisomerase 1 antibody;CRP, C reactive protein;DLCO, diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide;FVC, forced vital capacity; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction;NYHA, New York Heart Association; mRSS, modified Rodnan skin score.

Discussion

We investigated the association between skin progression and subsequent visceral organ progression in the large, prospective, multicentre, real-life EUSTAR cohort. Our findings indicate that patients with dcSSc and skin progression within 1 year have a higher probability of lung progression and worse survival during follow-up. These findings suggest that such patients should be monitored very carefully in clinical practice. The results also support the concept that inclusion of patients with lower mRSS or shorter disease duration can enrich clinical trials for progressive skin fibrosis, and this enrichment leads to study populations with more severe disease at higher risk of organ progression and overall death. Notably, this increased risk of more severe disease occurs at >1 year’s follow-up and will thus not be detectable in a classical 1-year randomised controlled trial. Our findings emphasise that mRSS progression within 1 year is an appropriate surrogate marker for more severe disease during follow-up.

This study also provides evidence for cohort enrichment in clinical studies aiming primarily at lung fibrosis. Several parameters, including dcSSc, anti-topoisomerase 1-positive status and decreased baseline FVC have been identified in multiple studies as predictors of lung progression in SSc.20 28–34 However, few studies have focused specifically on patients with dcSSc. In the current EUSTAR analysis, skin progression was associated with subsequent decline of lung function in patients with dcSSc, even after adjustment for potentially confounding predictors. We examined two definitions of lung progression based on pulmonary function tests. The conventional definition (relative decrease in FVC ≥10%), based on expert group consensus, has been widely used as an endpoint in previous clinical studies, while the exploratory FVC-DLCO composite definition has recently been shown to predict mortality in patients with SSc-related interstitial lung disease.35 Analyses with both definitions produced similar results, strengthening our findings.

We also found that skin progression within 1 year was independently associated with higher all-cause mortality. Previously, several prognostic studies have tried to predict mortality in patients with SSc. The most common baseline characteristics independently associated with worse survival reported in different cohorts include older age, male sex, dcSSc, lung fibrosis, PH, systolic heart dysfunction, restrictive lung function defect, defective diffusing capacity of the lung, proteinuria, history of SRC and digital ulcers, all of which have been confirmed in studies derived from the EUSTAR database.21 22 36–44 We included these potentially significant and clinically relevant predictors in our multivariable Cox regression analysis, and found that skin progression, along with several other factors, was still an independent prognostic factor for all-cause death.

In our cohort, average disease duration at baseline was >7 years, indicating that most cases were not early disease. In subgroup analyses, we confirmed that disease course is worse in patients with dcSSc with early disease, although there were also patients with later-stage disease who showed organ progression. This underlines the heterogeneity of the disease course and clinicians should therefore pay attention to all patients with progression of skin fibrosis, even those with longer disease duration. Our findings are supported by the results of a study that focused on early dcSSc using a different definition of skin progression.23

One limitation of our analysis is the problem of missing values and loss to follow-up, which was inevitable in such a huge multicentre registry database. This partly explains the low number of patients during long-term follow-up. However, we tried to overcome this by multiple imputation before regression analysis and for most variables there were relatively few missing values. Second, we were unable to determine specific causes of death at all participating centres, and therefore only all-cause mortality, regardless of attribution to SSc, could be assessed. However, all-cause mortality is considered a more robust measure of disease outcome than SSc-associated mortality, as cause of death is often difficult to assign. Third, there was a relatively high proportion of new PH cases during follow-up in our cohort. This was the result of basing the definition on assessment of PH on echocardiography by the treating physician rather than on right heart catheterisation, which is required for formal diagnosis of PH. Unfortunately, right heart catheterisation data are not reliably available in the EUSTAR database, and echocardiography was the best available approximation of PH for the present analysis. Finally, as a result of the observational design, we did not evaluate the effect of treatment on outcomes. However, treatment of SSc, especially with immunosuppressive therapy, is always individualised and organ specific, and it is therefore difficult to accurately exclude the influence of treatment in an unselected heterogeneous cohort. In addition, there is a meaningful treatment-by-indication error in observational studies, making interpretation of results difficult. In our cohort, the proportions of patients receiving immunosuppressive treatment between groups at baseline were equal.

In conclusion, progressive skin fibrosis is associated with decline in lung function and worse survival in dcSSc during follow-up. The evidence-based findings obtained from the large prospective EUSTAR cohort allow optimisation of cohort enrichment in future clinical trials aimed at skin and lung fibrosis, and also help clinicians to identify patients at risk of lung progression in clinical practice.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Nicole Schneider for excellent administration and data entry into the EUSTAR cohort. Medical writing assistance was provided by Adelphi Communications Ltd (Bollington, UK), funded by Bayer AG (Berlin, Germany).

Footnotes

Handling editor: Josef S Smolen

Presented at: Shown as a poster on the ACR/ARHP Annual Meeting in San Diego 2017 (Abstract No. 732).

Collaborators: EUSTAR Collaborators (numerical order of centres): Marco Matucci-Cerinic, Serena Guiducci, University of Florence, Italy; Ulrich Walker, Veronika Jaeger, Bettina Bannert, University Hospital Basel, Switzerland; Giovanni Lapadula, School of Medicine University of Bari, Italy; Radim Becvarare, 1st Medical School, Charles University, Prague, Czech Republic; Maurizio Cutolo, University of Genova, Italy; Gabriele Valentini, Policlinico U.O. Reumatologia, Naples, Italy; Elise Siegert, Charité University Hospital, Berlin, Germany; Simona Rednic, University of Medicine & Pharmacy, 'Iuliu Hatieganu' Cluj, Cluj-Napoca, Romania; Yannick Allanore, University Cochin Hospital, Paris, France; C Montecucco, IRCCS Policlinico S Matteo, Pavia, Italy; Patricia E Carreira, Hospital 12 de Octubre, Madrid, Spain; Srdan Novak, KBC Rijeka, Croatia; László Czirják, Cecilia Varju, University of Pécs, Hungary; Carlo Chizzolini, Daniela Allai, University Hospital Geneva, Switzerland; Eugene J Kucharz, Medical University of Silesia, Katowice, Poland; Franco Cozzi, University of Padova, Italy; Blaz Rozman, University Medical Center Ljublijana, Slovenia; Carmel Mallia, 'Stella Maris', Balzan, Malta; Armando Gabrielli, Istituto di Clinica Medica Generale, Ematologia ed Immunologia Clinica, Università Politecnica delle Marche Polo Didattico, University of Ancona, Italy; Dominique Farge Bancel, Hôpital Saint-Louis, Paris, France; Paolo Airò, Spedali Civili di Brescia Servizio di Reumatologia Allergologia e Immunologia Clinica, Brescia, Italy; Roger Hesselstrand, Lund University Hospital, Sweden; Duska Martinovic, Clinical Hospital of Split, Croatia; Alexandra Balbir-Gurman, Yolanda Braun-Moscovici, B. Shine Rheumatology Institute, Rambam Health Care Campus, Haifa, Israel; Nicolas Hunzelmann, Universitätshautklinik Köln, Germany; Raffaele Pellerito, Ospedale Mauriziano, Torino, Italy; Paola Caramaschi, Università degli Studi di Verona, Italy; Carol Black, Royal Free and University College London Medical School, London, UK; Nemanja Damjanov, Institute of Rheumatology Belgrade, Serbia and Montenegro; Jörg Henes, Medizinische Universitätsklinik Abt. II, Tübingen, Germany; Vera Ortiz Santamaria, Rheumatology Granollers General Hospital, Barcelona, Spain; Stefan Heitmann, Marienhospital Stuttgart, Germany; Matthias Seidel, Medizinische Universitäts-Poliklinik, Bonn, Germany; José Antonio Pereira Da Silva, da Universidade, Coimbra, Portugal; Bojana Stamenkovic, Institute for Prevention, Treatment and Rehabilitation Rheumatic and Cardiovascular Disease Niska Banja, Serbia and Montenegro; Carlo Francesco Selmi, University of Milan, Italy; Mohammed Tikly, Chris Hani Baragwanath Hospital and University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa; Lev N. Denisov, VA Nasonova Institute of Rheumatology, Moscow, Russia; Ulf Müller-Ladner, Kerckhoff Clinic Bad Nauheim, Germany; Merete Engelhart, University Hospital of Gentofte, Hellerup, Denmark; Eric Hachulla, Hôpital Claude Huriez, Lille, France; Valeria Riccieri, 'Sapienza' Università di Roma, Italy; Ruxandra Maria Ionescu, St. Maria Hospital, Carol Davila University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Bucharest, Romania; Carina Mihai, Ion Cantacuzino Clinical Hospital, Bucharest, Romania; Cord Sunderkötter, Annegret Kuhn, University of Münster, Germany; Georg Schett, Jörg Distler, Universitätsklinikum Erlangen, Germany; Pierluigi Meroni, Francesca Ingegnoli, Istituto Gaetano Pini, University of Milano, Italy; Luc Mouthon, Hôpital Cochin, Paris, France; Filip De Keyser, Vanessa Smith, University of Ghent, Belgium; Francesco Paolo Cantatore, Ada Corrado, U.O. Reumatologia-Università degli Studi di Foggia, Ospedale 'Col. D’Avanzo', Foggia, Italy; Susanne Ullman, Line Iversen, University Hospital of Copenhagen, Denmark; Maria Rosa Pozzi, Ospedale San Gerardo, Monza, Italy; Kilian Eyerich, Rüdiger Hein, Elisabeth Knott, TU Munich, Germany; Piotr Wiland, Magdalena Szmyrka-Kaczmarek, Renata Sokolik, Ewa Morgiel, Marta Madej, Wroclaw University of Medicine, Poland; Juan Jose Alegre-Sancho, Hospital Universitario Dr Peset, Valencia, Spain; Brigitte Krummel-Lorenz, Petra Saar, Endokrinologikum Frankfurt, Germany; Martin Aringer, Claudia Günther, Erler Anne, University Medical Center, Carl Gustav Carus, Technical University of Dresden, Germany; Rene Westhovens, Ellen De Langhe, Jan Lenaerts, University Hospital Leuven, Skeletal Biology and Engineering Research Center, Leuven, Belgium; Branimir Anic, Marko Baresic, Miroslav Mayer, University of Zagreb, School of Medicine, University Hospital Center Zagreb, Croatia; Maria Üprus, Kati Otsa, East-Tallin Central Hospital, Tallin, Estonia; Sule Yavuz, University of Marmara, Altunizade-Istanbul, Turkey; Sebastião Cezar Radominski, Carolina de Souza Müller, Valderílio Feijó Azevedo, Hospital de Clinicas da Universidade Federal do Parana, Curitiba, Brazil; Sergei Popa, Republican Clinical Hospital, Chisinau, Republic of Moldova; Thierry Zenone, Unit of Internal Medicine, Valence, France; Simon Stebbings, John Highton, Dunedin School of Medicine, New Zealand; Alessandro Mathieu, Alessandra Vacca, II Chair of Rheumatology, University of Cagliari-Policlinico Universitario, Cagliari, Italy; Lisa Stamp, Peter Chapman, John O’Donnell, University of Otago, Christchurch, New Zealand; Kamal Solanki, Alan Doube, Waikato University Hospital, Hamilton, New Zealand; Douglas Veale, Marie O’Rourke, St. Vincent’s University Hospital, Dublin, Ireland; Esthela Loyo, Hospital Regional Universitario Jose Ma Cabral y Baez, Clinica Corominas, Santiago, Dominican Republic; Mengtao Li, Peking Union Medical College Hospital (West Campus), Beijing, China; Edoardo Rosato, Antonio Amoroso, Antonietta Gigante, Sapienza Università di Roma, Università La Sapienza, Policlinico Umberto I, Roma, Italy; Fahrettin Oksel, Figen Yargucu, Ege University, Bornova, Izmir, Turkey; Cristina-Mihaela Tanaseanu, Monica Popescu, Alina Dumitrascu, Isabela Tiglea, Clinical Emergency Hospital St. Pantelimon, Bucharest, Romania; Rosario Foti, Elisa Visalli, Alessia Benenati, Giorgio Amato, A.O.U. Policlinico Vittorio Emanuele La U.O. Di Reumatologia, A.O.U. Policlinico V.E. Catania Centro di Riferimento Regionale Malattie Rare Reumatologiche, Catania, Italy; Codrina Ancuta, Rodica Chirieac, GR.T. Popa Center for Biomedical Research, European Center for Translational Research, University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Rehabilitation Hospital, Iasi, Romania; Peter Villiger, Sabine Adler, Diana Dan, University of Bern, Switzerland; Paloma García de la Peña Lefebvre, Silvia Rodriguez Rubio, Marta Valero Exposito, Hospital Universitario Sanchinarro, Madrid, Spain; Jean Sibilia, Emmanuel Chatelus, Jacques Eric Gottenberg, Hélène Chifflot, University Hospital of Strasbourg, Hôpital de Hautepierre, Strasbourg, France; Ira Litinsky, Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center, Israel; Francesco Del Galdo, University of Leeds, Chapel Allerton Hospital, Leeds, UK; Algirdas Venalis, State Research Institute for Innovative Medicine, Vilnius University, Lithuania; Lesley Ann Saketkoo, Joseph A Lasky, Tulane/University Medical Center Scleroderma and Sarcoidosis Patient Care and Research Center, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA; Eduardo Kerzberg, Fabiana Montoya, Vanesa Cosentino, Osteoarticular Diseases and Osteoporosis Centre, Pharmacology and Clinical Pharmacological Research Centre, School of Medicine, University of Buenos Aires, Ramos Mejía Hospital, Buenos Aires, Argentina; Massimiliano Limonta, Antonio Luca Brucato, Elide Lupi, USSD Reumatologia, Ospedali Riuniti di Bergamo, Italy; François Spertini, Camillo Ribi, Guillaume Buss, Department of Rheumatology, Clinical Immunology and Allergy, Lausanne, Switzerland; Thierry Martin, Aurélien Guffroy, Vincent Poindron, Nouvel Hôpital Civil, Strasbourg, France; Lori Chung, Stanford University School of Medicine, California, USA; Tim Schmeiser, Krankenhaus St. Josef, Wuppertal-Elberfeld, Germany; Pawel Zebryk, Poznan University of Medical Sciences, Poland; Nuno Riso, Unidade de Doencas Autoimunes—Hospital Curry Cabral, Centro Hospitalar Lisboa Central, Lisbon, Portugal; Gabriela Riemekasten, Universitätsklinik Lübeck, Germany; Elena Rezus, University of Medicine and Pharmacy 'GR.T. Popa' Iasi, Rehabilitation Hospital, Iasi, Romania; Piercarlo Sarzi Puttini, University Hospital Luigi Sacco, Milan, Italy.

Contributors: Study conception and design: OD, WW, SJ, YA, DK, CPD, MM-C, JEP, JdOP, JC. Acquisition of data: OD, WW, YA, CPD, MM-C, EUSTAR co-authors. Analysis and interpretation of data: NG, OD, WW, SJ. Drafting the article: WW, OD, SJ. Revising the article: NG, YA, DK, CPD, MM-C, JEP, JdOP, JC.

Funding: This study was supported by a grant from Bayer AG.

Disclaimer: Bayer did not have any influence on the interpretation of the data.

Competing interests: OD has obtained research support from Bayer, Sanofi, Ergonex, Boehringer Ingelheim, Actelion and Pfizer. He is a scientific consultant for 4D Science, Actelion, Active Biotec, Bayer, BiogenIdec, BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, ChemoAb, EpiPharm, Ergonex, espeRare foundation, Genentech/Roche, GSK, Inventiva, Lilly, Medac, MedImmune, Pharmacyclics, Pfizer, Serodapharm and Sinoxa, and has a patent licensed on mir-29 for the treatment of systemic sclerosis. DK has consultancy relationships and/or has received grant/research support from Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, Genentech/Roche, NIH, Pfizer, Sanofi-Aventis Pharmaceuticals, Actelion Pharmaceuticals US, Chemomab, Corbus, Covis, Cytori, Eicos, EMD Serono, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline and UCB Pharma. He is a shareholder of Eicos. CPD has consultancy relationships with and/or has received speakers’ bureau fees from Actelion Pharmaceuticals US, Bayer AG, GlaxoSmithKline, CSL Behring, Merck-Serono, Roche Pharmaceuticals, Genentech and Biogen IDEC Inc., Inventiva, Sanofi-Aventis Pharmaceuticals and Boehringer Ingelheim. JEP has consultancy relationships with and/or has received grant/research support from Actelion, Bayer AG, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck, Pfizer Inc. and Roche. MM-C has consultancy relationships and/or has received grant/research support from Pfizer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Actelion, UCB Pharma, Bayer, ChemomAb, Genentech/Roche, Inventiva and Lilly. YA has consultancy relationships with and/or has received grant/research support from Actelion, Pharmaceuticals US, Bayer AG, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Inventiva, Medac, Pfizer Inc., Roche Pharmaceuticals, Genentech and Biogen IDEC Inc., Sanofi-Aventis Pharmaceuticals and Servier. JdOP and JC are employees of Bayer. WW, SJ and NG have nothing to disclose.

Ethics approval: All contributing EUSTAR centres have obtained approval from their respective local ethics committee for including patients’ data in the EUSTAR database and written informed consent was obtained in those centres, where required by the ethics committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Contributor Information

EUSTAR Collaborators:

Marco Matucci-Cerinic, Serena Guiducci, Ulrich Walker, Veronika Jaeger, Bettina Bannert, Giovanni Lapadula, Radim Becvarare, Maurizio Cutolo, Gabriele Valentini, Elise Siegert, Simona Rednic, Yannick Allanore, C. Montecucco, Patricia E. Carreira, Srdan Novak, László Czirják, Cecilia Varju, Carlo Chizzolini, Daniela Allai, Eugene J. Kucharz, Franco Cozzi, Blaz Rozman, Carmel Mallia, Armando Gabrielli, Dominique Farge Bancel, Paolo Airò, Roger Hesselstrand, Duska Martinovic, Alexandra Balbir-Gurman, Yolanda Braun-Moscovici, Nicolas Hunzelmann, Raffaele Pellerito, Ospedale Mauriziano, Paola Caramaschi, Carol Black, Nemanja Damjanov, Jörg Henes, Vera Ortiz Santamaria, Stefan Heitmann, Matthias Seidel, José Antonio Pereira Da Silva, Bojana Stamenkovic, Carlo Francesco Selmi, Mohammed Tikly, Lev N. Denisov, Ulf Müller-Ladner, Merete Engelhart, Eric Hachulla, Valeria Riccieri, Ruxandra Maria Ionescu, Carina Mihai, Cord Sunderkötter, Annegret Kuhn, Georg Schett, Jörg Distler, Pierluigi Meroni, Francesca Ingegnoli, Luc Mouthon, Filip De Keyser, Vanessa Smith, Francesco Paolo Cantatore, Ada Corrado, Susanne Ullman, Line Iversen, Maria Rosa Pozzi, Kilian Eyerich, Rüdiger Hein, Elisabeth Knott, Piotr Wiland, Magdalena Szmyrka-Kaczmarek, Renata Sokolik, Ewa Morgiel, Marta Madej, Juan Jose Alegre-Sancho, Brigitte Krummel-Lorenz, Petra Saar, Martin Aringer, Claudia Günther, Erler Anne, Rene Westhovens, Ellen De Langhe, Jan Lenaerts, Branimir Anic, Marko Baresic, Miroslav Mayer, Maria Üprus, Kati Otsa, Sebastião Cezar Radominski, Carolina de Souza Müller, Valderílio Feijó Azevedo, Sergei Popa, Simon Stebbings, John Highton, Alessandro Mathieu, Alessandra Vacca, Lisa Stamp, Peter Chapman, John O'Donnell, Kamal Solanki, Alan Doube, Douglas Veale, Marie O'Rourke, Esthela Loyo, Mengtao Li, Edoardo Rosato, Antonio Amoroso, Antonietta Gigante, Fahrettin Oksel, Figen Yargucu, Cristina-Mihaela Tanaseanu, Monica Popescu, Alina Dumitrascu, Isabela Tiglea, Rosario Foti, Elisa Visalli, Alessia Benenati, Giorgio Amato, Codrina Ancuta, Rodica Chirieac, Peter Villiger, Sabine Adler, Diana Dan, Paloma García de la Peña Lefebvre, Silvia Rodriguez Rubio, Marta Valero Exposito, Jean Sibilia, Emmanuel Chatelus, Jacques Eric Gottenberg, Hélène Chifflot, Ira Litinsky, Algirdas Venalis, Lesley Ann Saketkoo, Joseph A. Lasky, Eduardo Kerzberg, Fabiana Montoya, Vanesa Cosentino, Massimiliano Limonta, Antonio Luca Brucato, Elide Lupi, François Spertini, Camillo Ribi, Guillaume Buss, Thierry Martin, Aurélien Guffroy, Vincent Poindron, Lori Chung, Tim Schmeiser, Pawel Zebryk, Nuno Riso, Gabriela Riemekasten, Elena Rezus, and Piercarlo Sarzi Puttini

Collaborators: EUSTAR Collaborators

References

- 1. Khanna D, Denton CP. Evidence-based management of rapidly progressing systemic sclerosis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2010;24:387–400. 10.1016/j.berh.2009.12.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Khanna D, Distler JHW, Sandner P, et al. . Emerging strategies for treatment of systemic sclerosis. J Scleroderma Relat Disord 2016;1:186–93. 10.5301/jsrd.5000207 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Denton CP, Khanna D. Systemic sclerosis. Lancet 2017;390:1685–99. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30933-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Khanna D, Furst DE, Clements PJ, et al. . Standardization of the modified Rodnan skin score for use in clinical trials of systemic sclerosis. J Scleroderma Relat Disord 2017;2:11–18. 10.5301/jsrd.5000231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Clements PJ, Lachenbruch PA, Seibold JR, et al. . Skin thickness score in systemic sclerosis: an assessment of interobserver variability in 3 independent studies. J Rheumatol 1993;20:1892–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Clements P, Lachenbruch P, Siebold J, et al. . Inter and intraobserver variability of total skin thickness score (modified Rodnan TSS) in systemic sclerosis. J Rheumatol 1995;22:1281–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Furst DE, Clements PJ, Steen VD, et al. . The modified Rodnan skin score is an accurate reflection of skin biopsy thickness in systemic sclerosis. J Rheumatol 1998;25:84–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Maurer B, Graf N, Michel BA, et al. . Prediction of worsening of skin fibrosis in patients with diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis using the EUSTAR database. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:1124–31. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-205226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dobrota R, Maurer B, Graf N, et al. . Prediction of improvement in skin fibrosis in diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis: a EUSTAR analysis. Ann Rheum Dis 2016;75:1743–8. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-208024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Distler O, Pope J, Denton C, et al. . RISE-SSc: riociguat in diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis. Respir Med 2017;122(Suppl 1):S14–S17. 10.1016/j.rmed.2016.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Steen VD, Medsger TA. Improvement in skin thickening in systemic sclerosis associated with improved survival. Arthritis Rheum 2001;44:2828–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Clements PJ, Hurwitz EL, Wong WK, et al. . Skin thickness score as a predictor and correlate of outcome in systemic sclerosis: high-dose versus low-dose penicillamine trial. Arthritis Rheum 2000;43:2445–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Shand L, Lunt M, Nihtyanova S, et al. . Relationship between change in skin score and disease outcome in diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis: application of a latent linear trajectory model. Arthritis Rheum 2007;56:2422–31. 10.1002/art.22721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Walker UA, Tyndall A, Czirják L, et al. . Clinical risk assessment of organ manifestations in systemic sclerosis: a report from the EULAR Scleroderma Trials and Research group database. Ann Rheum Dis 2007;66:754–63. 10.1136/ard.2006.062901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Meier FMP, Frommer KW, Dinser R, et al. . Update on the profile of the EUSTAR cohort: an analysis of the EULAR Scleroderma Trials and Research group database. Ann Rheum Dis 2012;71:1355–60. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Preliminary criteria for the classification of systemic sclerosis (scleroderma). Subcommittee for scleroderma criteria of the American Rheumatism Association Diagnostic and Therapeutic Criteria Committee. Arthritis Rheum 1980;23:581–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. LeRoy EC, Black C, Fleischmajer R, et al. . Scleroderma (systemic sclerosis): classification, subsets and pathogenesis. J Rheumatol 1988;15:202–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Khanna D, Furst DE, Hays RD, et al. . Minimally important difference in diffuse systemic sclerosis: results from the D-penicillamine study. Ann Rheum Dis 2006;65:1325–9. 10.1136/ard.2005.050187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kumánovics G, Péntek M, Bae S, et al. . Assessment of skin involvement in systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology 2017;56(suppl_5):v53–66. 10.1093/rheumatology/kex202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Avouac J, Walker UA, Hachulla E, et al. . Joint and tendon involvement predict disease progression in systemic sclerosis: a EUSTAR prospective study. Ann Rheum Dis 2016;75:103–9. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-205295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mihai C, Landewé R, van der Heijde D, et al. . Digital ulcers predict a worse disease course in patients with systemic sclerosis. Ann Rheum Dis 2016;75:681–6. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-205897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Elhai M, Avouac J, Walker UA, et al. . A gender gap in primary and secondary heart dysfunctions in systemic sclerosis: a EUSTAR prospective study. Ann Rheum Dis 2016;75:163–9. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-206386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Domsic RT, Rodriguez-Reyna T, Lucas M, et al. . Skin thickness progression rate: a predictor of mortality and early internal organ involvement in diffuse scleroderma. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:104–9. 10.1136/ard.2009.127621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Khanna D, Mittoo S, Aggarwal R, et al. . Connective Tissue Disease-associated Interstitial Lung Diseases (CTD-ILD)—report from OMERACT CTD-ILD Working Group. J Rheumatol 2015;42:2168–71. 10.3899/jrheum.141182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. R Core Team R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Therneau T. A package for survival analysis in S. version 2, 2015. Available: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=survival

- 27. Buuren Svan, Groothuis-Oudshoorn K. Mice : Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations in R. J Stat Softw 2011;45:1–67. 10.18637/jss.v045.i03 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jaeger VK, Wirz EG, Allanore Y, et al. . Incidences and risk factors of organ manifestations in the early course of systemic sclerosis: a longitudinal EUSTAR study. PLoS One 2016;11:e0163894 10.1371/journal.pone.0163894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hoffmann-Vold A-M, Aaløkken TM, Lund MB, et al. . Predictive value of serial high-resolution computed tomography analyses and concurrent lung function tests in systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2015;67:2205–12. 10.1002/art.39166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nihtyanova SI, Schreiber BE, Ong VH, et al. . Prediction of pulmonary complications and long-term survival in systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2014;66:1625–35. 10.1002/art.38390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gilson M, Zerkak D, Wipff J, et al. . Prognostic factors for lung function in systemic sclerosis: prospective study of 105 cases. Eur Respir J 2010;35:112–7. 10.1183/09031936.00060209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Assassi S, Sharif R, Lasky RE, et al. . Predictors of interstitial lung disease in early systemic sclerosis: a prospective longitudinal study of the GENISOS cohort. Arthritis Res Ther 2010;12 10.1186/ar3125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Plastiras SC, Karadimitrakis SP, Ziakas PD, et al. . Scleroderma lung: initial forced vital capacity as predictor of pulmonary function decline. Arthritis Rheum 2006;55:598–602. 10.1002/art.22099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cottrell TR, Wise RA, Wigley FM, et al. . The degree of skin involvement identifies distinct lung disease outcomes and survival in systemic sclerosis. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:1060–6. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Goh NS, Hoyles RK, Denton CP, et al. . Short-term pulmonary function trends are predictive of mortality in interstitial lung disease associated with systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2017;69:1670–8. 10.1002/art.40130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Elhai M, Meune C, Boubaya M, et al. . Mapping and predicting mortality from systemic sclerosis. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:1897–905. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-211448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Fransen J, Popa-Diaconu D, Hesselstrand R, et al. . Clinical prediction of 5-year survival in systemic sclerosis: validation of a simple prognostic model in EUSTAR centres. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:1788–92. 10.1136/ard.2010.144360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tyndall AJ, Bannert B, Vonk M, et al. . Causes and risk factors for death in systemic sclerosis: a study from the EULAR scleroderma trials and research (EUSTAR) database. Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:1809–15. 10.1136/ard.2009.114264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hachulla E, Clerson P, Airò P, et al. . Value of systolic pulmonary arterial pressure as a prognostic factor of death in the systemic sclerosis EUSTAR population. Rheumatology 2015;54:1262–9. 10.1093/rheumatology/keu450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Simeón-Aznar CP, Fonollosa-Plá V, Tolosa-Vilella C, et al. . Registry of the Spanish network for systemic sclerosis: survival, prognostic factors, and causes of death. Medicine 2015;94:e1728 10.1097/MD.0000000000001728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hussein H, Lee P, Chau C, et al. . The effect of male sex on survival in systemic sclerosis. J Rheumatol 2014;41:2193–200. 10.3899/jrheum.140006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hoffmann-Vold A-M, Molberg Øyvind, Midtvedt Øyvind, et al. . Survival and causes of death in an unselected and complete cohort of Norwegian patients with systemic sclerosis. J Rheumatol 2013;40:1127–33. 10.3899/jrheum.121390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sampaio-Barros PD, Bortoluzzo AB, Marangoni RG, et al. . Survival, causes of death, and prognostic factors in systemic sclerosis: analysis of 947 Brazilian patients. J Rheumatol 2012;39:1971–8. 10.3899/jrheum.111582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Domsic RT, Nihtyanova SI, Wisniewski SR, et al. . Derivation and external validation of a prediction rule for five-year mortality in patients with early diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2016;68:993–1003. 10.1002/art.39490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Valentini G, D'Angelo S, Della Rossa A, et al. . European scleroderma Study group to define disease activity criteria for systemic sclerosis. IV. Assessment of skin thickening by modified Rodnan skin score. Ann Rheum Dis 2003;62:904–5. 10.1136/ard.62.9.904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

annrheumdis-2018-213455supp001.docx (19.4KB, docx)