Abstract

Background

Literature on the efficacy of azathioprine in antihistamine refractory chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU) is limited.

Objective

To compare the efficacy and safety of azathioprine with respect to cyclosporine in the treatment of refractory CSU.

Methods

In this prospective, randomized, active-controlled, non-inferiority study, 80 patients of refractory CSU were administered either cyclosporine (group A, n = 40) or azathioprine (group B, n = 40) for 90 days and followed up for further 90 days. The treatment efficacy was assessed every 15th day using urticaria activity score (UAS7) and outcome scoring scale (OSS). Serum IgE levels, autologous serum skin test (ASST) and autologous plasma skin test (APST) were additionally measured at baseline and 90th day.

Results

Primary end point (≥75% reduction in UAS7 at 90th day) was achieved by 31/40 (79.5%) patients in group A and 32/40 (80%) patients in group B (proportion difference −0.5%, 95% confidence interval [CI] of difference -17.13 to 18.09; point estimates favoring B, CIs demonstrating non-inferiority). At 180th day, ≥75% reduction in UAS7 was maintained in 19/40 (47.95%) patients in group A and 24/40 (60%) patients in group B (proportion difference −12.5%, 95% CI of difference -9.00 to 32.46, point estimates favoring B, CIs demonstrating non-inferiority). Thus, the number of patients who could maintain ≥75% reduction in UAS7 at 180th day reduced significantly in group A (proportion difference 30%, 95% CI of difference 8.78 to 47.77), but not in group B (proportion difference 20%, 95% CI of difference -0.10 to 38.10). The values of mean UAS7 significantly decreased from 28.70 ± 4.42 and 28.88 ± 4.25 at baseline, to 5.56 ± 5.12 and 7.0 ± 4.48 at 90th day in group A and B respectively (group A, mean difference −23.27, 95% CI of difference -25.33 to -21.22; group B, mean difference −21.87, 95% CI of difference -23.78 to -19.96). It increased significantly to 9.98 ± 5.46 in group A at 180th day (mean difference 4.55, 95% CI of difference 2.98 to 6.12), but not in group B (mean UAS7 180th day 7.88 ± 5.53, mean difference 0.88, 95% CI of difference -0.82 to 2.57). The reduction in number of patients having positive ASST post-treatment was significant in group A, whereas reduction in IgE levels was more significant in group B.

Conclusion

The present study concludes that azathioprine is not inferior to cyclosporine in the treatment of refractory CSU, and it can be a valuable adjunct, especially in resource poor settings.

Keywords: Refractory chronic spontaneous urticaria, Cyclosporine, Azathioprine, Urticaria activity score

Introduction

According to recent EAACI/GA2LEN/EDF/WAO, guideline (European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, Global Allergy and Asthma European Network, European Dermatology Forum, World Allergy Organization),1, 2 second-generation H1 antihistamines (AH1) are the first line treatment options for chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU). Non-response to AH1 is common3 and almost 10–50% of patients do not respond adequately to even 4-fold increased doses of AH1 and end up requiring repeated courses of oral corticosteroids to control disease exacerbations.4, 5, 6 As per the EAACI/GA2LEN/EDF/WAO guideline, a treatment option for such patients includes the addition of omalizumab, the availability of which is limited due to high costs.2 Cyclosporine is the next line treatment option for these patients, but its use is restricted owing to high costs (especially in resource poor settings) and associated adverse effects.2 Azathioprine was found to be beneficial in cyclosporine resistant CSU in 2 patients7 (in a dosage of 150 mg/day) and also responded fairly in autologous serum skin test (ASST) positive CSU in a prior placebo-controlled study (in a dosage of 50 mg/day).8 In the absence of any previous study, we attempted to compare azathioprine with cyclosporine (an established agent in the management of antihistamine refractory CSU) in this prospective, active-controlled, non-inferiority study.

Methods

Study design

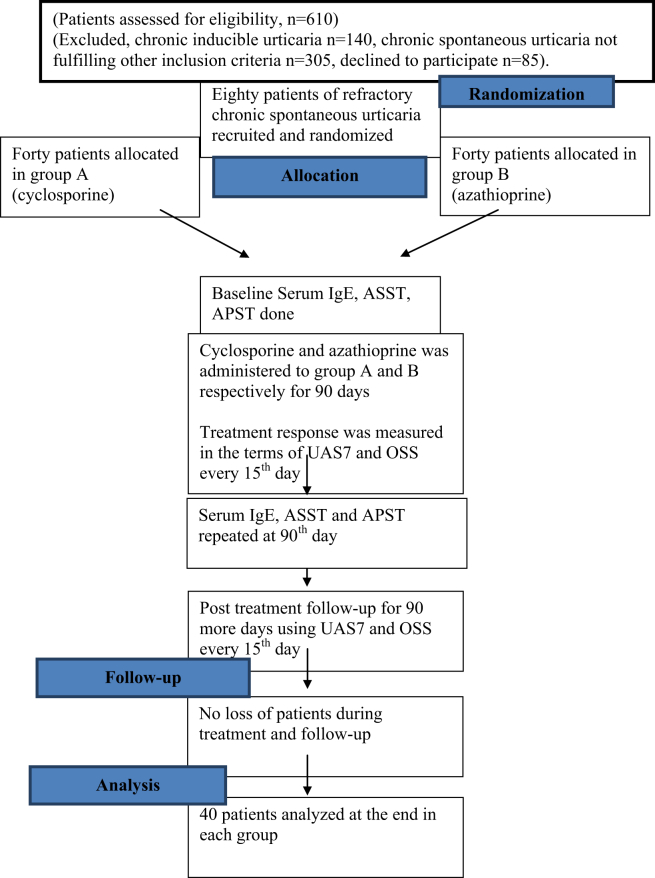

This randomized, prospective, comparative study was conducted at the urticaria clinic of a tertiary care center in North India, which is a Global Allergy and Asthma European Network (GA2LEN) recognized center for urticaria management. Sample size of 40 per arm (allocation ratio, r = 1) was calculated using a non-inferiority trial design; using a power of 80% (β = 0.2), type 1 error (alpha at two sided 95% confidence intervals) = 0.025, and a non-inferiority margin (delta) of −0.2 (20% loss of effect).9 The non-inferiority margin was derived from the previous placebo-controlled randomized controlled study of cyclosporine (with a confidence interval of 6.6–18.8 for UAS7 reduction for cyclosporine [sandimmune preparation, 4 mg/kg], and −3.3-7.9 for placebo).10 All consecutive chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU) patients with active disease presenting from June 2016 to July 2017 were screened (n = 610) to include 80 patients who satisfied the following inclusion-exclusion criteria (excluded chronic inducible urticaria [CINDU], n = 140; CSU not fulfilling other inclusion criteria, n = 305; declined to participate, n = 85).

Inclusion criteria

-

1.

Patients of CSU having active disease with duration ≥6 months (arbitrarily chosen; in absence of any valid definition for refractory urticaria) and

-

2.

Refractory CSU arbitrarily defined for present study as failure to respond to 4-fold increased doses of standard 2nd generation AH1 (levocetirizine) prescribed for at least 3 continuous months and requiring repeated short-term courses of oral corticosteroids, at least one such course per month.

Exclusion criteria

CINDU, urticarial vasculitis, acute urticaria and anaphylaxis, angioedema without wheals, pregnancy and lactation, underlying hepatic and renal disease and malignancy.

All recruited patients signed an informed written consent. The institute ethics committee approved the study (NCT03250143, trial registration number CTRI/2017/08/009213, both documents are being submitted in supplementary files). The overall study design is depicted in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart depicting the basic study design.

As per the EAACI/GA2LEN/EDF/WAO guideline, we uniformly start our patients having CU on recommended doses of AH1 (example, levocetirizine 5 mg), and sequentially increase the dose every week, until adequate clinical response is achieved or maximum dose is reached (4 times recommended dose). When a patient presents with acute exacerbation while still taking the maximum doses of antihistamines, a short course of oral prednisolone (0.5 mg/kg/day for 5–7 days) is administered. A non-response to four-fold dosages of antihistamines is subsequently followed by the addition of phototherapy, cyclosporine, methotrexate or omalizumab, based on the patient's clinical profile and affordability. Since ours is a tertiary care center, we see quite a few antihistamine refractory patients who have usually endured CSU for more than 6 months, or even more, and are on maximal licensed dosages of antihistamines at the time they present to us. After confirming their current and previous treatments, such patients are directly managed by the addition of various immunosuppressants to their antihistamine regimen.

Previous treatments

Apart from AH1 and oral corticosteroids, patients had received leukotriene receptor antagonists (n = 12) and methotrexate (n = 4). During a washout period of 1 month before inclusion in the present study, all treatments except AH1 (preferably levocetirizine) were discontinued.

Randomization and treatment

Forty random, single and double-digit numbers from 1 to 80 were extracted from computer-generated random number tables and assigned to a particular treatment arm (MSK). Eighty opaque brown-paper envelopes, each containing a paper slip with a particular number and corresponding treatment arm, were prepared to conceal the allocation sequence from both patient and randomizing investigator. These envelopes were arranged in a stack randomly. Eligible and consenting patients were randomized, in accordance with the particulars that the envelope on their sequence contained. The process of recruitment was performed by investigator DP. Patients in group A were administered cyclosporine (microemulsion form), whereas those in group B received azathioprine. Cyclosporine was started at a dose of 3 mg/kg/day, whereas azathioprine was started at a dose of 1 mg/kg/day (both administered in 2 divided doses, e.g., azathioprine 25 mg twice a day, cyclosporine 100 mg and 50 mg in morning and evening, respectively). Also, all patients were uniformly started on oral levocetirizine 10 mg/day, which was maintained throughout the treatment and follow-up period.

Baseline investigations

Comprehensive physical examination, complete hemogram, renal and hepatic function tests, urine microscopic examination, chest X-ray, serological tests for HIV, Hepatitis B and C, serum IgE levels, and thyroid function tests including thyroid autoantibodies were carried out in all patients prior to inclusion in the study. Serum IgE levels above 100 IU/ml were considered as raised (as per standardized chemiluminescence immune assay). Autologous serum skin test (ASST) and autologous plasma skin test (APST) were performed at baseline using standard guidelines,11 and they were considered positive if the average diameter of wheal induced by serum and plasma, respectively, was greater than 1.5 mm in comparison to the diameter of wheal induced by normal saline. All female patients were counseled regarding the need of employing 2 methods of contraception to avoid conception during treatment and 3 months thereafter and to disclose urgently if they developed amenorrhoea. Regular urine pregnancy tests (UPTs) were not advised, though one UPT was performed 15 days prior to starting treatment.

Assessment and follow-up

The total study period for each patient was 180 days, divided equally between treatment and follow-up (90 days each). Urticaria activity score (UAS)12 and outcome scoring scale (OSS)13 were used to measure the frequency and severity of the disease and response to treatment (Table 1). Complete hemogram, and renal and hepatic function tests were performed every 2 weeks for the first month and monthly thereafter. Monitoring of blood pressure was regularly performed with cyclosporine.

Table 1.

Urticaria activity score (UAS) and outcome scoring scale (OSS).

| Score | Wheals | Pruritus |

|---|---|---|

| Urticaria activity score (UAS) | ||

| 0 | None | None |

| 1 | Mild (<20 wheals/24 h) | Mild (present but not troublesome) |

| 2 | Moderate (20–50 wheals/24 h) | Moderate (troublesome but does not interfere with sleep) |

| 3 | Severe (>50 wheals/24 h) | Severe (sufficiently troublesome to interfere with normal daily activity and sleep) |

| Outcome scoring scale (OSS) | ||

| 1 | No improvement | |

| 2 | Minimal improvement (symptomatic improvement ±, no change in frequency and extent of the disease) | |

| 3 | Moderate improvement (symptomatic improvement +, less frequent and less extensive disease) | |

| 4 | Marked improvement (occasional episodes, less extensive disease, symptomatic improvement ++, reduced antihistamine use) | |

| 5 | Clearance (with or without antihistamines) | |

UAS7 is the standard urticaria disease activity measuring score.12 Patients were instructed to write down the number of wheals and severity of itching they experienced in their daily urticaria diary on a daily basis. At every 15th day, UAS7 (derived by adding itch and wheal score as written in the patient's diary for last week, range 0–42), and OSS (range 1–5) were calculated. At the completion of treatment (90th day), serum IgE levels, ASST and APST were repeated. Subsequently, patients were followed up every 15th day for 90 more days (using UAS7 and OSS at every follow-up). The follow-up of all patients was completed by January 2018. Since the standard chronic urticaria related quality of life score (CU-QoL) has not been validated in either Hindi or Punjabi (the national language and vernacular language of our region, respectively), for the purpose of present study patients were asked at the end of study period to subjectively grade cyclosporine and azathioprine as a treatment option for their CRU on scale of 0–10, with 0 being the worst and 10 being the best (defined as the patient satisfaction score).

Study end-points

Primary end-point

Number of patients achieving ≥75% reduction in their UAS7 at 90th day (end of treatment) compared to baseline.

Secondary end-points

-

1.

Change in mean UAS7and OSS from baseline to 90th (end of treatment)and 180th day (end of follow-up) within group A and B.

-

2.

Percentage of patients showing improvement on basis of OSS scoring.

-

3.

Change in ASST, APST and IgE levels from baseline to 90th day within group A and B.

-

4.

Comparison for the above mentioned parameters between group A and B.

-

5.

Patient global assessment using patient satisfaction score at 180th day for group A and B.

Relapse

Relapse was defined as return of UAS7 to the baseline value.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was carried out using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS for Windows). Normality of the quantitative data was assessed using Kolmogorov Smirnov test and their descriptive data was presented by Mean ± SD or median/interquartile (IQR) range, depending upon the distribution of the data (normal/skewed). Two-sided 95% confidence intervals were determined for all parameters, and all statistics were performed at a significance level of p = 0.025.

Results

Patients

The mean age of patients in groups A and B was 35.98 ± 9.36 years and 36.68 ± 9.68 years respectively (mean difference −0.70, 95% confidence interval [CI] of difference -4.94 to 3.54). Among 80 patients, 48 (60%, A-24, B-24) were females, and 32 (40%, A-16, B-16) were males. The mean duration of illness in groups A and B was 5.21 ± 4.87 and 6.56 ± 5.81 years, respectively (mean difference-1.35, 95% CI of difference -3.74 to 1.04), and 41 patients had angioedema (A-20, B-21). Total duration of treatment prior to inclusion in the present study was 29.4 ± 12.5 and 35.0 ± 25.7 months in groups A and B respectively. Baseline clinicodemographic features of both groups is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Baseline clinical and demographic characteristics of groups A and B.

| Baseline characteristics | Group A (Cyclosporine, reference group) | Group B (Azathioprine) | Mean/proportion difference | 95% CI of difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 40 | 40 | ||

| Age (years) | 35.98 ± 9.36 | 36.68 ± 9.68 | −0.70 | −4.94 to 3.54 |

| Duration of illness (years) | 5.21 ± 4.87 | 6.56 ± 5.81 | −1.35 | −3.74 to 1.04 |

| Gender (Female: Male) | 24:16 | 24:16 | 0% | −20.58 to 20.58 |

| Angioedema | 20 (50) | 21 (52.5) | 2.5% | −18.57 to 23.26 |

| UAS7 | 28.70 ± 4.42 | 28.88 ± 4.25 | −0.18 | −2.11 to 1.76 |

| ASST (positive) | 16 (40) | 12 (30) | 10% | −10.6 to 29.48 |

| APST (positive) | 2 (5) | 2 (5) | 0% | −12.06 to 12.06 |

| Serum IgE levels median (IQR, IU/ml) | 91.35 (50.2–248.75) | 243 (78.27–654.0) | −105.15@ | −308.0 to −16.8 |

@: (Hodges – Lehman median difference).

IQR – Interquartile range.

ASST – Autologous serum skin test.

APST – Autologous plasma skin test.

UAS7- urticaria activity score over 7 days, ranges from 0 to 42.

CI – Confidence Interval.

Bold numerical values show significant CIs.

Response to treatment (Table 3)

Table 3.

Comparison of primary and secondary end points within groups A and B, and between group A and group B.

| Variables | Group A, Cyclosporine | Difference (95% CI of difference) | Group B, Azathioprine | Difference (95% CI of difference) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Within group comparisons | ||||

| Mean UAS7 (baseline) | 28.70 ± 4.42 | 28.88 ± 4.25 | ||

| Mean UAS7 (90th day) | 5.43 ± 5.12 | −23.27 (−25.33 to −21.22) | 7.0 ± 4.48 | −21.87 (-23.78 to -19.96) |

| Mean UAS7 (180th day) | 9.98 ± 5.46 | 4.55 (2.98–6.12) | 7.88 ± 5.53 | 0.88 (−0.82 to 2.57) |

| Number of patients having ≥75% reduction in UAS7 on 90th day | n = 31 (77.5%) | 30% (8.78–47.77) | n = 32 (80%) | 20% (−0.10 to 38.10) |

| Number of patients having ≥75% reduction in UAS7 on 180th day | n = 19 (47.5%) | n = 24 (60%) | ||

| Mean OSS at 15th day | 2.85 ± 1.03 | 2.70 ± 0.91 | ||

| Mean OSS, 90th day | 4.25 ± 0.70 | 1.40 (1.06–1.74) | 4.05 ± 0.59 | 1.35 (1.06 to 1.65) |

| Mean OSS, 180th day | 3.59 ± 0.78 | −0.68 (−0.89 to −0.45) | 3.87 ± 0.79 | −0.18 (−0.41 to 0.06) |

| Number of patients having positive ASST (Baseline) | n = 16 (40%) | 5% (17.15–50.82) | n = 12 (30%) | 15% (−3.45 to 32.35) |

| Number of patients having positive ASST (90th day) | n = 2 (5%) | n = 6 (15%) | ||

| Number of patients having positive APST (Baseline) | n = 2 (5%) | 5% (−4.48 to 16.50) | n = 2 (5%) | 5% (−4.48 to 16.50) |

| Number of patients having positive APST (90th day) | n = 0 | n = 0 | ||

| S.IgE IU/ml, Baseline Median (IQR) |

91.35 (50.27–248.7) |

−27.65 (−64.35 to −10.10) (Hodges – Lehman median difference) |

243 (78.27–654.0) |

−88.57(-209.50 to -28.70) (Hodges – Lehman median difference) |

| S.IgE IU/ml, 90th day) Median (IQR) |

72.5 (40.5–147.50) |

164.15 (60.0–515.0) |

||

| Variables |

Group A, cyclosporine n (%) |

Group B, azathioprine n (%) |

Difference |

(95% CI of difference) |

| Comparison between group A and B | ||||

| Mean UAS7 (baseline) | 28.70 ± 4.42 | 28.88 ± 4.25 | −0.18 | −2.11 to1.76 |

| Mean UAS7 (90th day) | 5.43 ± 5.13 | 7.0 ± 4.48 | −1.57 | −3.72 to 0.57 |

| Mean UAS7 (180th day) | 9.98 ± 5.46 | 7.88 ± 5.53 | 2.10 | −0.35 to 4.55 |

| Number of patients who achieved ≥75% reduction in UAS7 on 90th day | 31 (79.5%) | 32 (80%) | −0.5% | −17.13 to 18.09 |

| Number of patients who could maintain ≥75% reduction in UAS7 on 180th day | 19 (47.5%) | 24 (60%) | −12.5% | −9.00 to 32.46 |

| Number of patients who could not maintain >75% reduction in UAS7 at 180th day | 12 (52.5%) | 8 (40%) | 12.5% | −9.00 to 32.46 |

| OSS, 90th day, Median (IQR) | 4 (4–5) | 4 (4–4.0) | 0.00(Hodges – Lehman median difference) | 0.00 to 0.00 |

| No improvement per OSS | – | – | – | – |

| Minimal improvement | 4/40 (10%) | – | 10% | −0.64 to 23.05 |

| Moderate improvement | 4/40 (10%) | 3/40 (7.5%) | 2.5% | −11.26 to 16.45 |

| Marked improvement | 19/40 (47.5%) | 29/40 (72.5%) | 25% | 3.54 to 43.49 |

| Clearance | 13/40 (32.5%) | 8/40 (20%) | 12.5% | −6.79 to 30.66 |

|

OSS, 180th day Median (IQR) |

4 (3–4) | 4 (3–4.0) | 0.00(Hodges – Lehman median difference) | −1.00 to 0.00 |

| No improvement per OSS | 1/40 (2.5%) | – | 2.5% | −6.50 to 12.88 |

| Minimal improvement | 5/40 (12.5%) | 1/40 (2.5%) | 10 | −2.54 to 23.77 |

| Moderate improvement | 15/40 (37.5%) | 9/40 (22.5%) | 15% | −5.03 to 33.52 |

| Marked improvement | 16/40 (40%) | 21/40 (52.5%) | 12.5% | −9.00 to 32.46 |

| Clearance | 3/40 (7.5%) | 9/40 (22.5%) | 15% | −1.02 to 30.79 |

| Number of patients with positive ASST (Baseline) | 16 (40%) | 12 (30%) | 10% | −10.60 to 29.48 |

| Number of patients with positive ASST (90th day) | 2 (5%) | 6 (15%) | 10% | −3.97 to 24.53 |

| Number of patients with positive APST (Baseline) | 2 (5%) | 2 (5%) | 0.0% | −12.06 to 12.06 |

| Number of patients with positive APST (90th day) | 0 | 0 | 0.0% | – |

| S.IgE (IU/ml, Baseline) Median (IQR) |

91.35 (50.2–248.75) | 243 (78.27–654.0) | −105.15@ | −308.0 to -16.8 |

| S.IgE (IU/ml, 90th day) Median (IQR) |

72.5 (40.5–147.5) | 164.15 (60.0–515.0) | −82.95@ | −228.0 to -19.50 |

@: (Hodges – Lehman median difference).

IQR – Interquartile range.

ASST – Autologous serum skin test.

APST – Autologous plasma skin test.

OSS – outcome scoring scale.

UAS – Urticaria activity score.

sIgE – serum Immunoglobulin E.

n = number of patients.

CI – Confidence Interval.

Bold numerical values show significant CIs.

Primary end point

Primary end point (≥75% reduction in UAS7 at end of treatment, i.e. on 90th day) was achieved by 31/40 (77.5%) patients in group A and 32/40 (80%) patients in group B (proportion difference −0.5%, 95% confidence interval [CI] of difference -17.13 to 18.09; point estimate favoring B, CIs demonstrating non-inferiority).

Secondary end points

Change in UAS7 (Table 3)

Within group analysis

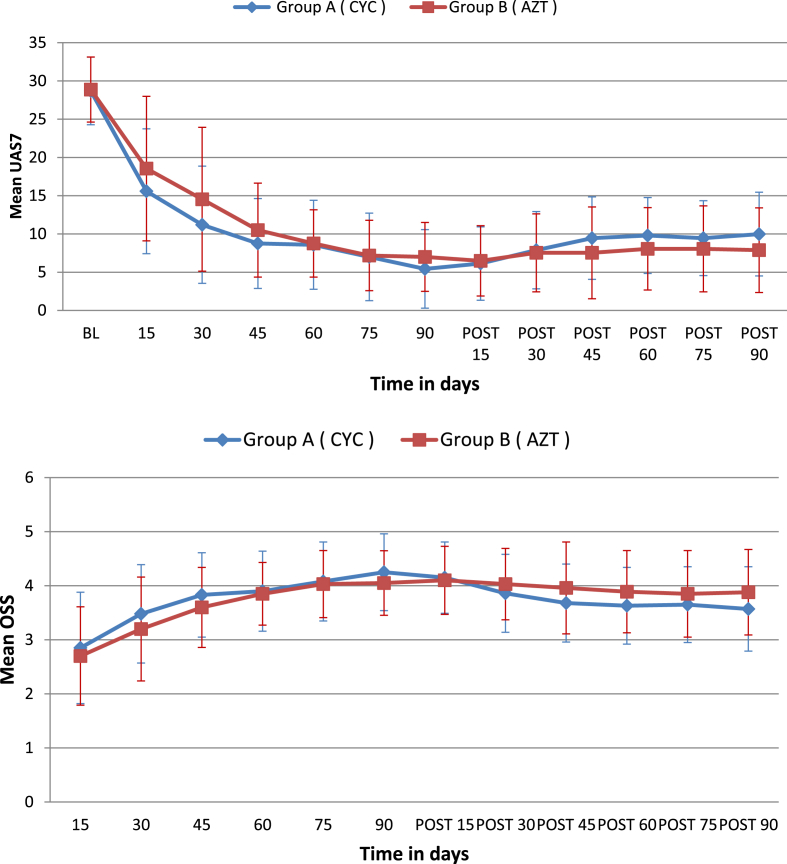

The values of mean UAS7 significantly decreased from 28.70 ± 4.42 and 28.88 ± 4.25 at baseline, to 5.56 ± 5.12 and 7.0 ± 4.48 at 90th day in group A and B respectively (group A, mean difference −23.27, 95% CI of difference -25.33 to -21.22; group B, mean difference −21.87, 95% CI of difference -23.78 to -19.96). It increased significantly to 9.98 ± 5.46 in group A at 180th day (mean difference 4.55, 95% CI of difference 2.98 to 6.12), but not in group B (mean UAS7 180th day 7.88 ± 5.53, mean difference 0.88, 95% CI of difference -0.82 to 2.57). Within group A this increase was statistically significant at all the follow-up visits; whereas in group B this increase was not statistically significant at any of the follow-up visits (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2.

a. Line diagram showing trend of change of mean urticaria activity score (UAS7) in groups A and B during 180 days of study period, also depicting standard errors of mean. b. Line diagram showing trend of change of mean outcome scoring scale (OSS) in groups A and B during 180 days of study period, also depicting standard errors of mean.

Comparison between groups

The mean UAS7 was not significantly different in groups A and B at 90th day (mean difference −1.57, 95% CI of difference -3.72 to 0.57; point estimate favoring A, CIs demonstrating non-inferiority) and 180th day (mean difference 2.10, 95% CI of difference -0.35 to 4.55; point estimate favoring B, CIs demonstrating non-inferiority). At 180th day, ≥75% reduction in UAS7 was maintained in 19/40 (47.95%) patients in group A and 24/40 (60%) patients in group B (proportion difference −12.5%, 95% CI of difference -9.00 to 32.46, point estimate favoring B, CIs demonstrating non-inferiority). The number of patients who could maintain ≥75% reduction in UAS7 at 180th day reduced significantly in group A (proportion difference 30%, 95% CI of difference 8.78 to 47.77) but not in group B (proportion difference 20%, 95% CI of difference -0.10 to 38.10).

Change in OSS (Table 3)

Within group analysis

The mean OSS significantly increased from 2.85 ± 1.04 and 2.70 ± 0.91 at 15th day to 4.23 ± 0.70 and 4.05 ± 0.59 at 90th day (mean difference 1.40, 95% CI of difference 1.06 to 1.74 in group A; mean difference 1.35, 95% CI of difference 1.06 to 1.65 in group B); and decreased to 3.59 ± 0.78 and 3.87 ± 0.79 at 180th day in group A and B respectively (group A, mean difference −0.68, 95% CI of difference -0.89 to -0.45; group B, mean difference −0.18, 95% CI of difference -0.41 to 0.06, Fig. 2b).

Comparison between groups

The values of OSS between the groups did not differ significantly when compared at 90th day ([group A, IQR 4–5, median 4], [group B, IQR 4–4.0, median 4], Mann Whitney test; median difference 0.00, 95% CI of difference 0.00 to 0.00) and 180th day ([group A, IQR 3–4, median 4], [group B, IQR 3–4.0, median 4], Mann Whitney test, median difference 0.00, 95% CI of difference -1.00 to 0.00). Number of patients achieving clearance, marked improvement, moderate improvement, minimal improvement and no improvement, as graded through OSS, are presented in Table 3.

Effect on ASST and APST

The number of ASST positive patients in group A decreased significantly from 16/40 (40%) at baseline to 2/40 (5%) at 90th day (Mc Nemar test, proportion difference 5%, 95% CI of difference 17.15 to 50.82); and that in group B decreased from 12/40 (30%) to 6/40 (15%) at 90th day (proportion difference 15%, 95% CI of difference -3.45 to 32.35). In both group A and B, 2 patients had positive APST at baseline, and both turned negative at the end of treatment (proportion difference 5%, 95% CI of difference -4.48 to 16.50, Table 3).

Effect on serum IgE levels

In group A, the median levels of serum IgE decreased significantly from 91.35 IU/ml (<100 IU/ml; IQR 50.27–248.75 IU/ml) at baseline to 72.5 IU/ml (IQR 40.5–147.5) at the 90th day (median difference −27.65, 95% CI of difference -64.35 to -10.10, Hodges-Lehman median difference). In group B, the median levels of serum IgE decreased significantly from 243.0 IU/ml (IQR 78.27–654.0 IU/ml) at baseline to 164.15 IU/ml (IQR 60.0–515.0 IU/ml) at the 90th day (median difference −88.57, 95% CI of difference -209.50 to -28.70, Hodges-Lehman median difference). The reduction in serum IgE levels was more significant in group B than A, but the values at baseline were also significantly higher in group B than A, Table 3.

Relapse

Relapse was noted in one patient in group A.

Mean patient satisfaction score

It was comparable at 180th day, being 7.5 in group A and 7.2 in group B (p 0.979, mean difference 0.30).

Adverse effects

Nausea and heartburn were experienced by 3 patients on initiating cyclosporine and responded adequately to rabeprazole. Abdominal pain and mild vomiting were experienced by 2 patients on initiating azathioprine, but responded to antiemetics. No hepatic, renal or hematological adverse effects were observed. All patients completed the study and there were no dropouts.

Discussion

CSU can have a dreadful effect on quality of life, especially when antihistamine resistant.14 Cyclosporine has been previously evaluated in the treatment of resistant urticaria in very low (<2 mg/kg/day), low (2–4 mg/kg/day) and moderate (4–5 mg/kg/day) dosages.10, 15, 16, 17 A recent meta-analysis suggested 3 mg/kg/day as a reasonable starting dosage of cyclosporine in resistant urticaria, a dose that was employed in the present study.18 Moreover, cyclosporine has proved quite safe in CRU,19, 20 with no adverse effects being noticed even after 5–10 years of therapy at low doses.21 There are only 2 prior publications stating the efficacy of azathioprine in CU. A placebo-controlled study by Bhanja et al.,8 found low-dose azathioprine (50 mg/day) to be effective in a cohort of ASST positive CSU patients and the remission lasted till 36 weeks. Azathioprine was also employed successfully in 2 patients having resistant urticaria who had failed high-dose cyclosporine.7

In the present study, we compared low-dose cyclosporine with low dose azathioprine using a non-inferiority design, and the primary end point (≥75% reduction in UAS7 at the end of treatment) was achieved by 77.5% patients in group A and 80% patients in group B (comparable to 66–73% response to low-moderate dosages of cyclosporine at 12 weeks, as suggested previously18). Clinically meaningful minimum important difference (MID) for UAS7 has been previously defined between 9.5-10.5.22 In the present study, the reduction observed in UAS7 at 90th day when compared to baseline was 23.3 and 22.3 in cyclosporine and azathioprine groups, respectively (Table 2, Table 3), and it was comparable to that obtained with omalizumab in prior studies.23 Patients in both groups were able to achieve a significant reduction in their mean UAS7 at 90th day (end of treatment), after which UAS7 started rising gradually in both groups indicating increase in disease activity. The rise was significantly more in group A, and it became significant as soon as 30 days after stopping cyclosporine. A similar trend was observed with OSS, and it rose significantly in both the groups with treatment, only to reduce again in post treatment. The reduction was statistically significant in group A, and was seen as early as 30 days after discontinuation of cyclosporine. Although the patients achieving azathioprine also experienced mild increase in the disease activity after discontinuation of treatment, it was not significant. Overall, ≥75% reduction in UAS7 was maintained in 19 and 24 patients in groups A and B, respectively, during follow-up (as compared to 31 and 32 at 90th day respectively). Therefore, in the cyclosporine group, a statistically significant reduction was observed in the number of patients who could maintain ≥75% reduction in UAS7 at 180th day. Regarding the primary end-point, the point estimate favored azathioprine, whereas CIs demonstrated non-inferiority. Regarding the secondary end-point, point estimate of the difference in the mean “UAS7 reduction” favored cyclosporine at 90th day and azathioprine at 180th day; whereas the CIs demonstrated non-inferiority.

Relapse was noticed in 1 patient, who had achieved good initial control with cyclosporine. Azathioprine is known to cause myelosuppression and hepatitis, whereas cyclosporine can cause nephrotoxicity and hypertension. In the present study, adequate monitoring was routinely performed, and both agents were found to be safe, and serious adverse effects warranting the discontinuation of treatment were not noticed. This can be attributed to low doses of cyclosporine and azathioprine employed (comparable to prior study on azathioprine8). Both agents rendered antihistamine-resistant disease adequately responsive to antihistamines for the intended study duration and scored comparably on global patient satisfaction score at the end of the study.

Positive ASST and raised serum IgE levels are traditionally considered a marker of chronic and severe disease. The reduction in the number of patients having a positive ASST was significantly greater with cyclosporine, as seen in a prior study.10 Both azathioprine24 and cyclosporine have been found to reduce the levels of serum IgE levels in atopic dermatitis24 and CU25 respectively, though the results with cyclosporine in atopic dermatitis are conflicting.26 The exact mechanism for this is not known; though cyclosporine has also been shown to reduce the levels of IL-5 post-treatment in CSU.17 We observed that the reduction in IgE levels was more significant in patients receiving azathioprine, but the same cannot be overemphasized because the baseline serum IgE levels were significantly higher in azathioprine arm and values were lesser than 100 IU/ml in the cyclosporine arm. Moreover, repeated measurements of serum IgE levels are not recommended by current guidelines and should not be used as a surrogate marker to assess the degree of response to treatment.

Limitations

-

1.

Thiopurine methyl transferase levels could not be carried out because of affordability issues.

-

2.

Longer follow-up duration could have better ascertained the efficacy and relapse rate.

-

3.

One of the perceived limitations of the current study is the lack of a placebo group. However, withholding a potentially effective treatment in patients having severe refractory chronic spontaneous urticaria could not be ethically justified. Although lack of placebo arm does not allow us to definitely exclude the possibility of spontaneous remission (regression to the mean, as the patients are simply cured with time3), the strict inclusion criteria and the severity and duration of disease in our cohort (mean disease duration > 5 years, mean continuous treatment duration > 2 years, and baseline UAS7 >28) exceeded the time window normally associated with spontaneous remission.

-

4.

We have not objectively measured angioedema severity score and CU-QoL questionnaire in our patients.

Conclusion

The present study concludes that low-dose azathioprine is not inferior to low-dose cyclosporine in the treatment of antihistamine refractory CSU, and it can be a valuable adjunct in the treatment of patients who are intolerant to cyclosporine or have affordability issues, especially in resource poor settings.

Financial disclosure/Source of funding

None.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

The institute ethics committee approved the study (NCT03250143, trial registration number CTRI/2017/08/009213).

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.waojou.2019.100033.

Contributor Information

Yashdeep Singh Pathania, Email: yashdeepsinghpathania@gmail.com.

Anuradha Bishnoi, Email: dranha14@gmail.com.

Davinder Parsad, Email: PARSAD@me.com.

Ashok Kumar, Email: ajangir_27@yahoo.in.

Muthu Sendhil Kumaran, Email: drsen_2000@yahoo.com.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Zuberbier T., Aberer W., Asero R. The EAACI/GA(2)LEN/EDF/WAO Guideline for the definition, classification, diagnosis, and management of urticaria: the 2013 revision and update. Allergy. 2014;69:868–887. doi: 10.1111/all.12313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zuberbier T., Aberer W., Asero R. The EAACI/GA(2)LEN/EDF/WAO guideline for the definition, classification, diagnosis and management of urticaria. Allergy. 2018;73:1393–1414. doi: 10.1111/all.13397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van der Valk P.G., Moret G., Kiemeney L.A. The natural history of chronic urticaria and angioedema in patients visiting a tertiary referral centre. Br J Dermatol. 2002;146:110–113. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2002.04582.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Humphreys F., Hunter J.A. The characteristics of urticaria in 390 patients. Br J Dermatol. 1998;138:635–638. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.02175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaplan A.P. Therapy of chronic urticaria: a simple, modern approach. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2014;112:419–425. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2014.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morgan M., Khan D.A. Therapeutic alternatives for chronic urticaria: an evidence-based review, part 1. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2008;100:403–411. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60462-0. Quiz 12-4, 68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tal Y., Toker O., Agmon-Levin N., Shalit M. Azathioprine as a therapeutic alternative for refractory chronic urticaria. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:367–369. doi: 10.1111/ijd.12536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhanja D.C., Ghoshal L., Das S., Das S., Roy A.K. Azathioprine in autologous serum skin test positive chronic urticaria: a case-control study in a tertiary care hospital of eastern India. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:185–188. doi: 10.4103/2229-5178.156391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flight L., Julious S.A. Practical guide to sample size calculations: non-inferiority and equivalence trials. Pharm Stat. 2016;15:80–89. doi: 10.1002/pst.1716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grattan C.E., O'Donnell B.F., Francis D.M. Randomized double-blind study of cyclosporin in chronic 'idiopathic' urticaria. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:365–372. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03664.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Konstantinou G.N., Asero R., Maurer M., Sabroe R.A., Schmid-Grendelmeier P., Grattan C.E. EAACI/GA(2)LEN task force consensus report: the autologous serum skin test in urticaria. Allergy. 2009;64:1256–1268. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.02132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mlynek A., Zalewska-Janowska A., Martus P., Staubach P., Zuberbier T., Maurer M. How to assess disease activity in patients with chronic urticaria? Allergy. 2008;63:777–780. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2008.01726.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berroeta L., Clark C., Ibbotson S.H., Ferguson J., Dawe R.S. Narrow-band (TL-01) ultraviolet B phototherapy for chronic urticaria. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2004;29:97–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2004.01442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bishnoi A., Parsad D., Vinay K., Kumaran M.S. Phototherapy using narrowband ultraviolet B and psoralen plus ultraviolet A is beneficial in steroid-dependent antihistamine-refractory chronic urticaria: a randomized, prospective observer-blinded comparative study. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:62–70. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vena G.A., Cassano N., Colombo D., Peruzzi E., Pigatto P., Neo I.S.G. Cyclosporine in chronic idiopathic urticaria: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:705–709. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.04.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Loria M.P., Dambra P.P., D'Oronzio L. Cyclosporin A in patients affected by chronic idiopathic urticaria: a therapeutic alternative. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 2001;23:205–213. doi: 10.1081/iph-100103860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koski R., Kennedy K.K. Treatment with omalizumab or cyclosporine for resistant chronic spontaneous urticaria. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2017;119:397–401. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2017.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kulthanan K., Chaweekulrat P., Komoltri C. Cyclosporine for chronic spontaneous urticaria: a meta-analysis and systematic review. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018 Mar–Apr;6(2):586–599. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2017.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seth S., Khan D.A. The comparative safety of multiple alternative agents in refractory chronic urticaria patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5:165–170 e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2016.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Neverman L., Weinberger M. Treatment of chronic urticaria in children with antihistamines and cyclosporine. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2014;2:434–438. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2014.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kessel A., Toubi E. Cyclosporine-A in severe chronic urticaria: the option for long-term therapy. Allergy. 2010;65:1478–1482. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2010.02419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mathias S.D., Crosby R.D., Zazzali J.L., Maurer M., Saini S.S. Evaluating the minimally important difference of the urticaria activity score and other measures of disease activity in patients with chronic idiopathic urticaria. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2012;108:20–24. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2011.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maurer M., Rosen K., Hsieh H.J. Omalizumab for the treatment of chronic idiopathic or spontaneous urticaria. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:924–935. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1215372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuanprasert N., Herbert O., Barnetson R.S. Clinical improvement and significant reduction of total serum IgE in patients suffering from severe atopic dermatitis treated with oral azathioprine. Australas J Dermatol. 2002;43:125–127. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-0960.2002.00573.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guaragna M.A., Albanesi M., Stefani S., Franconi G., Di Stanislao C., Paparo Barbaro S. Chronic urticaria with high IgE levels: first results on oral cyclosporine A treatment. Clin Ter. 2013;164:115–118. doi: 10.7417/CT.2013.1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hijnen D.J., Knol E., Bruijnzeel-Koomen C., de Bruin-Weller M. Cyclosporin A treatment is associated with increased serum immunoglobulin E levels in a subgroup of atopic dermatitis patients. Dermatitis. 2007;18:163–165. doi: 10.2310/6620.2007.06025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.