ABSTRACT

Serine phosphorylation of STAT proteins is an important post-translational modification event that, in addition to tyrosine phosphorylation, is required for strong transcriptional activity. However, we recently showed that phosphorylation of STAT2 on S287 induced by type I interferons (IFN-α and IFN-β), evoked the opposite effect. S287-STAT2 phosphorylation inhibited the biological effects of IFN-α. We now report the identification and characterization of S734 on the C-terminal transactivation domain of STAT2 as a new phosphorylation site that can be induced by type I IFNs. IFN-α-induced S734-STAT2 phosphorylation displayed different kinetics to that of tyrosine phosphorylation. S734-STAT2 phosphorylation was dependent on STAT2 tyrosine phosphorylation and JAK1 kinase activity. Mutation of S734-STAT2 to alanine (S734A) enhanced IFN-α-driven antiviral responses compared to those driven by wild-type STAT2. Furthermore, DNA microarray analysis demonstrated that a small subset of type I IFN stimulated genes (ISGs) was induced more by IFNα in cells expressing S734A-STAT2 when compared to wild-type STAT2. Taken together, these studies identify phosphorylation of S734-STAT2 as a new regulatory mechanism that negatively controls the type I IFN-antiviral response by limiting the expression of a select subset of antiviral ISGs.

KEY WORDS: STAT2, Serine phosphorylation, JAK1, Interferon, Virus infection, Vesicular stomatitis

Summary: Phosphorylation of STAT2 at S724 selectively regulates the antiviral, but not the anti-proliferative, effects of type I interferons (IFNs) by limiting the expression of a select subset of IFN-stimulated genes.

INTRODUCTION

Signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) 2 is a pivotal component of the type I interferon (IFN) signaling pathway (Leung et al., 1995; Steen and Gamero, 2013). Type I IFNs, which include IFN-α, -β, -ε, -κ and -ω, activate the tyrosine phosphorylation of both STAT2 and STAT1 through engagement of the heterodimeric type I IFN receptor composed of IFNΑR1 and IFNΑR2 (Darnell, 1997; Pestka et al., 2004). IFN binding to its receptor triggers the activation of protein tyrosine Janus kinases (JAK)1 and TYK2 through reciprocal transphosphorylation in response to receptor dimerization (Barbieri et al., 1994; Muller et al., 1993; Velazquez et al., 1995; Yan et al., 1996). JAK1 and TYK2 phosphorylate STAT1 and STAT2 on a conserved tyrosine residue, resulting in dimerization of the two STATs, that together with the DNA-binding protein IRF9 form the heterotrimeric IFN-stimulated gene factor 3 (ISGF3) complex (Fu et al., 1990, 1992; Improta et al., 1994). ISGF3 translocates to the nucleus and binds to the promoters of multiple IFN-stimulated genes (ISGs) to activate their transcription (Fu et al., 1990; Li et al., 1997a). The resulting gene products drive the cellular responses to IFNs that include antiviral, antiproliferative and, in certain instances, pro-apoptotic responses (Chawla-Sarkar et al., 2001; de Veer et al., 2001).

The specific role of STAT2 in the ISGF3 complex is to provide its transactivation domain (TAD) for full transcriptional activity (Li et al., 1996). The STAT2 TAD is situated at the C-terminal end and spans ∼100 amino acid residues (amino acids 747–851) (Kraus et al., 2003) and binds p300 and CBP (hereafter p300/CBP, also known as EP300 and CREBBP, respectively) and GCN5 (also known as KAT2A), both of which are involved in facilitating transcription through their histone acetylation activities (Bhattacharya et al., 1996; Paulson et al., 2002). Earlier studies have suggested that the most crucial region for transactivation resides between residues 800 and 832 because deletion of this region abolished the transcriptional activity of ISGF3 (Qureshi et al., 1996). Later studies have suggested T800 and Y833 as additional phosphorylation sites (Farrar et al., 2000; Hornbeck et al., 2012; Shiromizu et al., 2013). Although mutation of Y833 to a phenylalanine residue impaired dimerization of STAT2–STAT4 induced by type I IFNs, evidence is lacking to support the biological significance of T800 and Y833 in their phosphorylated state (Hornbeck et al, 2012; Shiromizu et al 2013).

Aside from tyrosine phosphorylation, serine phosphorylation modulates the transcriptional activity of the STATs. STATs are phosphorylated on serine residues located predominantly in the N-terminal region of the TAD, usually 20–30 amino acid residues C-terminal of the conserved tyrosine (Decker and Kovarik, 2000). STAT1, STAT3, STAT4, STAT5a and STAT5b all share a conserved motif consisting of two prolines flanking either a single serine residue or a serine residue preceded by a methionine residue, usually referred to as the ‘P(M)SP’ motif, that is targeted for phosphorylation. STAT2 and STAT6 are the exception as they lack the PMSP motif. STAT6, however, is phosphorylated at a serine residue in the TAD, but its function is to inhibit gene activation (Shirakawa et al., 2011). Most recently, we made the discovery that S287-STAT2, which is mapped to the coiled-coil domain, is phosphorylated in response to IFN-α stimulation (Steen et al., 2013). In contrast to other STATs, but similarly to STAT6, phosphorylation of S734-STAT2 did not augment, but rather inhibited, gene transcription.

In this study, we report that S734 is a new STAT2 phosphorylation site targeted by type I IFN stimulation. This molecular event relies on JAK kinase activity and STAT2 tyrosine phosphorylation. Phosphorylation of S734-STAT2 plays a specific role in type I IFN signaling by contributing to the inactivation of the antiviral, but not the anti-proliferative, response to IFN-α and IFN-β. Our findings indicate that phosphorylation of STAT2 at specific serine residues dictate the specificity and kinetics of an IFN-α and IFN-β response.

RESULTS

Identification of a new IFN-α-induced S734-STAT2 phosphorylation by mass spectrometry

To gain further insight into the regulation of type I IFN signaling by post-translational modifications of STAT2, we reconstituted STAT2-null U6A cells with human STAT2. We treated these cells with or without IFN-α and immunoprecipitated STAT2 from these cells, which was then subjected to mass spectrometry. From this analysis, we identified phosphorylation of S734 as a new IFN-α-induced post-translational modification of STAT2 (Fig. 1). S734 maps to the TAD of STAT2 (Fig. 1B) and appears to be evolutionarily restricted to primates (Fig. 1C). To confirm our mass spectrometry data and show that STAT2 was indeed phosphorylated on S734 after stimulation with type I IFNs, we generated a polyclonal rabbit antibody against an immunopeptide containing phosphorylated (p)S734 and its surrounding amino acids. We established the specificity of the pS734-STAT2 antibody in two ways. First, we showed the absence of a pS734-STAT2 signal in immunoblots of protein lysates from parental U6A cells and U6A cells stably expressing mutant STAT2 in which S734 was changed to alanine (S734A) (Fig. 2A; Fig. S1A). Of note, a second band was often detected migrating immediately below the pS734-STAT2-specifc band. Given that this band was also detected in STAT2-null U6A cells and in S734A-STAT2-expressing U6A cells, we interpret this lower protein band to be non-specific. Second, to confirm that the observed protein band recognized by our pS734-STAT2 antibody was indeed a phosphorylated amino acid, immunoprecipitated wild-type (WT-)STAT2 was treated with or without lambda protein phosphatase (LPP). LPP treatment eliminated the protein band corresponding to pS734-STAT2 (Fig. 2B). With these two sequential approaches, we convincingly demonstrate the specificity of the anti-pS734-STAT2 antibody.

Fig. 1.

Mass spectrometry identifies S734 as a type I IFN-inducible phosphorylatable residue in human STAT2 that is conserved in primates. (A) Tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) spectrum of STAT2 after treatment with IFN-α. +P (lower panel) indicates S734 as being phosphorylated and the underlined peptide mass (lower panel) indicates the presence of the peptide in the spectrum (upper panel). P, phosphoryl group (79.97 Da). Not all peaks are annotated in the mass spectrum. Matches were made with a mass tolerance of ±2 Da. (B) S734 is mapped to the transactivation domain (TAD) of STAT2. (C) Cross-species conservation of this phosphorylation site is seen in primate STAT2.

Fig. 2.

STAT2 is phosphorylated at S734 in response to IFN-α treatment. (A) U6A cells stably expressing empty vector, WT-STAT2 or S734A-STAT2 were treated with human IFN-α (1000 U/ml) for the indicated times. Phosphorylation of S734-STAT2 was detected by western blot analysis using an affinity purified polyclonal antibody raised against this phosphorylated epitope. IFN-α-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT2 (pY-STAT2) and STAT1 (pY-STAT1) together with total levels of STAT2 and STAT1 were also assessed by western blot analysis. (B) Immunoreactivity of the pS734-STAT2 antibody is confirmed by a lambda protein phosphatase (LPP) assay. (C–F) Immortalized hTERT cells (C) and human colorectal cancer cells F6-8 (D), T29 (E) and (F) Stat2−/− MEFs reconstituted with human STAT2 were stimulated with either human IFN-α (1000 U/ml) or murine IFN-β (1000 U/ml), accordingly, and examined as in A. GAPDH was used as an internal loading control.

S734-STAT2 phosphorylation by IFN-α is observed in multiple cell lines

We consistently detected constitutive phosphorylation of S734-STAT2 in resting U6A cells reconstituted with WT-STAT2. The level of phosphorylated S734-STAT2 was increased with IFN-α after 1 h of treatment that then peaked at 4 h (Fig. 2A). We next evaluated the basal phosphorylation and the kinetics of IFN-α-induced phosphorylation of S734-STAT2 in cell lines that express endogenous STAT2. No basal levels of phosphorylated S734-STAT2 were observed in immortalized human mammary epithelial hTERT-HME1 cells. In response to IFN-α treatment, induction of serine phosphorylation was first detected at 8 h of cytokine exposure that peaked around 12 h and decreased thereafter (Fig. 2C). As expected, given that STAT2 is an ISG, total STAT2 levels also increased over time in hTERT-HME1 cells. The observed decrease in pS734-STAT2 detected at 24 h did not correlate with elevated STAT2 levels, indicating at least a partial independence between STAT2 levels and S734-STAT2 phosphorylation in hTERT-HME1 cells. Similarly, IFN-α treatment also induced S734-STAT2 phosphorylation in two human colon carcinoma cell lines (Fig. 2D,E). Additionally, we show that human STAT2 was phosphorylated on S734 when reconstituted in Stat2−/− mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) following treatment with murine IFN-β (Fig. 2F; Fig. S1B). It is important to remark that in all the cell lines we studied, with the exception of T29 cells, IFN-α-stimulated phosphorylation of S734-STAT2 peaked later when compared against Y690-STAT2 phosphorylation. Furthermore, we found no differences in the kinetics of tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT2 and STAT1 between U6A cells expressing wild-type and mutant S734A-STAT2 at up to 8 h of IFN-α treatment (Fig. 2A). However, when examined at 24 h, we found STAT2 tyrosine phosphorylation to be prolonged in S734A-STAT2 U6A cells and barely detectable in WT-STAT2 U6A cells (Fig. 7D), indicating that S734-STAT2 plays a role in regulating STAT2 activation.

Fig. 7.

S734-STAT2 regulates the expression of a subset of ISGs. (A) Microarray analysis identified a small subset of ISGs for which mRNA levels were found to be enhanced in S734A-STAT2 U6A cells when compared against WT-STAT2 U6A cells after 4 h of IFN-α (1000 U/ml) treatment. Genes marked in A with an asterisk were subsequently validated by qPCR using (B) U6A or (C) Stat2−/− MEFs reconstituted with either human WT- or S734-STAT2 treated with or without IFN-α or IFN-β (1000 U/ml) for 6, 18 or 24 h. The mRNA levels were normalized to actin expression and calculated by using ΔΔCt method. Data are presented as the mean±s.e.m. fold change from untreated cells from three or four independent experiments. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 (Student's t-test). (D) WT-STAT2 and S734A-STAT2 U6A cells were stimulated or not with IFN-α (1000 U/ml) for 24 or 60 h and levels of ISG15 and OAS1 as well as pY-STAT2, pY-STAT1, STAT1, STAT2 and GAPDH as indicated, were assessed by western blot analysis.

IFN-α can induce phosphorylation of STAT2 at S734 only in the presence of JAK kinases and if its Y690 is phosphorylated

To define the signaling requirements for S734-STAT2 phosphorylation, we first examined the role of STAT2 tyrosine phosphorylation as a potential pre-requisite event, as previously demonstrated with STAT1 serine phosphorylation (Sadzak et al., 2008). We chose two well-characterized STAT2 mutants for this analysis: Y690F-STAT2 and R409A/K415A-STAT2 (RKAA). The Y690F-STAT2 mutant cannot be phosphorylated by type I IFNs and is thus unable to translocate to the nucleus (Li et al., 1997b). The RKAA-STAT2 mutant is retained in the cytosol due to a non-functioning nuclear localization signal, but preserves its capacity to become phosphorylated on tyrosine (Melen et al., 2001). Accordingly, we reconstituted STAT2-null U6A cells with WT-, RKAA- or Y690F-STAT2. The STAT2-reconstituted U6A cells were treated with or without IFN-α and assayed for pS734-STAT2 by immunoblot analysis. We detected a basal level of pS734-STAT2 with all three versions of STAT2 (Fig. 3A). In response to IFN-α treatment, RKAA-STAT2 showed an increase in S734 phosphorylation (Fig. 3A). In contrast, Y690F-STAT2 did not undergo S734-STAT2 phosphorylation, supporting the notion that tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT2 is necessary for the inducible phosphorylation of S734-STAT2 by type I IFNs. To test the potential contribution of JAK kinases in the phosphorylation of S734-STAT2, U6A cells expressing WT-STAT2 were pre-treated with pan-JAK inhibitor followed by treatment with IFN-α. Western blot analysis demonstrated that JAK activity was necessary for IFN-α-dependent induction of pS734-STAT2 (Fig. 3B). To further validate these results, we evaluated pS734-STAT2 in JAK1-deficient U4A cells. Lack of JAK1 not only impaired pS734-STAT2 by IFN-α, but also basal STAT2 serine phosphorylation (Fig. 3C). Collectively, these results identify tyrosine phosphorylation on Y690 as a prerequisite for enhancing basal S734 phosphorylation of STAT2 in response to IFN-α treatment. Furthermore, IFN-α-induced S734-STAT2 phosphorylation appears to take place in the cytosol as evidenced by the behavior of the RKAA-STAT2 mutant.

Fig. 3.

Phosphorylation of S734-STAT2 is dependent on STAT2 tyrosine phosphorylation and catalytically active JAK kinases. (A) U6A cells stably expressing WT-, R409A/K415A (RKAA)-, or Y690F-STAT2 were left untreated or treated for 1 and 4 h with IFN-α (1000 U/ml). Tyrosine and serine phosphorylation of STAT2, and GAPDH were assessed by western blot analysis. Data were quantified and shown as the ratio of pS734-STAT2 to STAT2 and pY690-STAT2 to STAT2. The arrow indicates a non-specific protein band (NS). (B) U6A cells expressing WT-STAT2 were pre-treated or not with pan-JAK inhibitor overnight (o/n) and (C) U4A cells and U6 cells expressing WT-STAT2 stimulated with IFN-α (1000 U/ml) for the specified times were evaluated for pS734-STAT2, pY-STAT2, pY-STAT1, STAT1, STAT2 and GAPDH as indicated. (D) STAT1 immune complexes obtained from U6A cells expressing WT-STAT2 that were left untreated or treated with IFN-α (1000 U/ml) were evaluated for interactions with pS734-STAT2 and total STAT2 by western blot analysis.

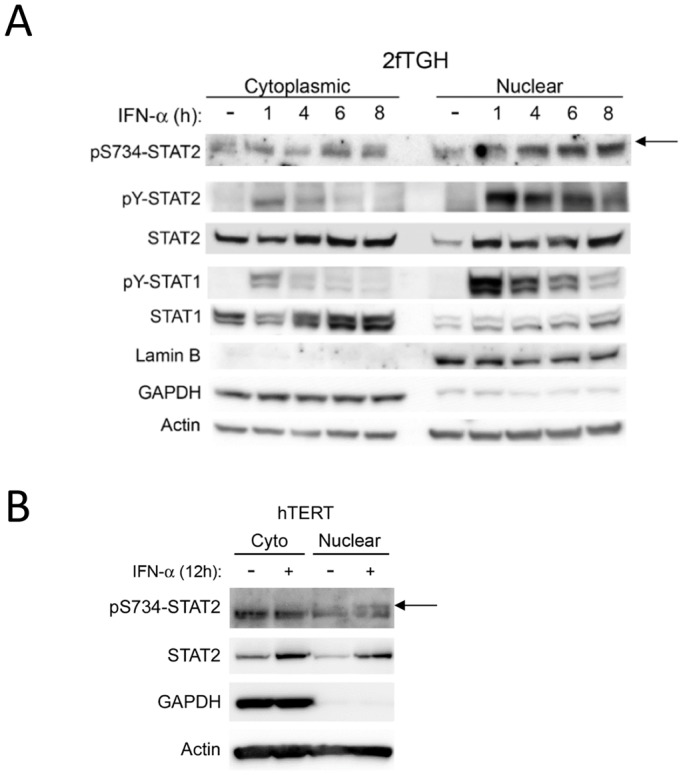

Moreover, immunoprecipitation of STAT1 from U6A WT-STAT2 cells revealed that, in the absence of IFN-α treatment, STAT2 associated with STAT1 was serine phosphorylated at a basal level (Fig. 3D). Treatment with IFN-α increased pS734-STAT2, but did not alter pS734-STAT2 binding to STAT1, indicating that pS734-STAT2 is neither enriched in nor excluded from IFN-α-induced STAT2–STAT1 dimers. Moreover, analysis of cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts from IFN-α-treated 2fTGH cells (the parent of U6A cells) showed a time-dependent accumulation of nuclear pS734-STAT2. After 1 h of IFN-α stimulation, the amount of cytoplasmic pS734-STAT2 was decreased, which coincides with an initial accumulation of nuclear pS734-STAT2. Between 4 h and 8 h of IFN-α treatment, pS734-STAT2 peaks, and a higher level is seen in the nucleus with some detected in the cytoplasm, although at reduced levels (Fig. 4A). We also detected pS734-STAT2 accumulation in the nucleus of IFN-α-treated hTERT cells (Fig. 4B). As expected, phosphorylation of S734-STAT2 in hTERT cells required a much longer incubation time with IFN-α, as we previously determined in Fig. 2C. Our data, therefore, show that JAK1-dependent tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT2 is a prerequisite for enhancing STAT2 serine phosphorylation with optimal S734-STAT2 phosphorylation peaking when STAT2 is tyrosine phosphorylated. This finding correlated with a steady increase in the level of phosphorylated S734-STAT2 in the nucleus. Further, U6A cells expressing the RKAA-STAT2 mutant showed intact IFN-α-induced pS734-STAT2 (Fig. 3A). Thus, these results reveal that phosphorylation of S734-STAT2 by type I IFNs must be occurring in the cytoplasm before STAT2 translocates to the nucleus.

Fig. 4.

Subcellular localization of phosphorylated S734-STAT2. Nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions of human (A) 2fTGH and (B) hTERT cells treated with IFN-α (1000 U/ml) for the given times were evaluated for pS734-STAT2, pY-STAT2, pY-STAT1, STAT1 and STAT2 by western blot analysis as indicated. Presence of GAPDH in the cytoplasmic extract and presence of Lamin B1 in the nuclear extract confirmed purity of fractions. The arrow indicates the upper band corresponding to pS734-STAT2. Actin was used as an internal loading control.

S734-STAT2 phosphorylation does not affect the IFN-α-induced antiproliferative activity, but diminishes the IFN-α-induced antiviral state

To elucidate the biological relevance of phosphorylated S734-STAT2 in type I IFN signaling, we compared the anti-proliferative responses to IFN-α in U6A cells expressing WT-STAT2 or S734A-STAT2. First, no significant differences in growth rates were observed between U6A cells expressing WT-STAT2 and those expressing S734A-STAT2 (Fig. 5A). Second, the anti-proliferative effects of IFN-α were also unaffected by S734A-STAT2. Similar results were obtained with the phosphomimetic mutant STAT2-S734D (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

Phosphorylation of S734-STAT2 does not affect the antiproliferative effects of IFN-α. (A) Growth rate of U6A cells stably expressing WT-, S734A- or S734D-STAT2 was measured at 48 h and 72 h by an MTS assay. The inset shows a western blot analysis of STAT2 expression in U6A cells expressing empty vector, WT-, S734A or S734D-STAT2. (B) The same panel of cells was treated with 100 U/ml or 1000 U/ml of IFN-α for 72 h and cell viability determined by MTS assay. Results are presented as the percentage of viable cells in the presence of IFN-α compared against untreated cells. Data shown are from three or four independent experiments and presented as mean±s.e.m.

Next, we asked whether phosphorylation on S734 affected IFN-α-mediated antiviral responses. To this end, we left untreated or pre-treated U6A cells expressing WT-STAT2 or S734A-STAT2 with 1000 U/ml of IFN-α, before infection with a prototypic IFN-sensitive virus vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) that also encodes for GFP expression (VSV-GFP) (Fig. 6A). Quantifying progeny virus yield from these cells demonstrated that, although there was no detectable difference at 24 h between cells expressing WT-STAT2, and phospho-null or phosphomimetic STAT2 mutants (data not shown), virion production at 36 h from S734A-STAT2-containing cells was significantly reduced compared to cells expressing WT-STAT2 (∼3×105 pfu ml−1 versus ∼4×106 pfu ml−1) or phosphomimetic S734D-STAT2 mutant (Fig. 6A). Note that expression of S734A-STAT2 or WT-STAT2 in the absence of IFN-α treatment rendered U6A cells similarly susceptible to VSV infection. It is also important to mention that S734A-STAT2 led to increased STAT2 tyrosine phosphorylation compared to WT-STAT2 in U6A cells pre-treated with IFN-α at 3 h but not at 36 h post-VSV infection (Fig. S2). No differences were found in the level of tyrosine-phosphorylated STAT1 under these conditions. Expression of S734D-STAT2 had no significant effect on VSV yield at either 24 or 36 h post infection, compared to WT-STAT2-expressing cells. We speculate that the effect of the phosphomimetic mutant is masked by phosphorylation of S287-STAT2 because, as reported by us previously (Steen et al. 2013), it negatively regulates type I IFN and because pS287-STAT2 led to a much stronger phenotype than pS734-STAT2. To confirm our findings using a different cell line, we infected Stat2−/− MEFs expressing either human WT-STAT2 or S734A-STAT2 that had been pre-treated with or without IFN-β with VSV-GFP. We quantified expression of VSV-GFP 36 h later by flow cytometry to determine the degree of viral infection. We found that compared to IFN-β-pre-treated Stat2−/− MEFs expressing human WT-STAT2, IFN-β-pre-treated Stat2−/− MEFs expressing human S734A-STAT2 showed enhanced viral protection at 36 h post infection (Fig. 6B). Taken together, these results indicate that phosphorylation of STAT2 on S734 serves to negatively regulate the type I IFN antiviral response.

Fig. 6.

S734A-STAT2 enhances IFN-α-induced protection against VSV infection. (A) The U6A cell panel was left untreated or pre-treated with IFN-α (1000 U/ml) for 16 h and then infected with GFP-tagged vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) for 36 h. Viral titers after 36 h post-viral infection (h.p.i.) were determined by plaque assay. Viral titers are shown on a log scale. (B) Western blot analysis of STAT2 expression in Stat2−/− MEFs reconstituted with either human WT- or S734A-STAT2. (C) Stat2−/− MEFs expressing human WT- or S734A-STAT2 were pre-treated or not with murine IFN-β (1000 U/ml) for 16 h and VSV infection was quantified by flow cytometry analysis of GFP-positive cells. Data are shown as the mean±s.e.m. from three or four independent experiments. **P<0.01 (Student's t-test). NS, not statistically significant.

S734-STAT2 phosphorylation enhances the expression of a subset of IFN-stimulated antiviral genes

We next conducted whole-genome DNA microarray analysis to identify potential differences in the transcriptional responses to IFN-α between WT-STAT2 and S734A-STAT2 that might explain how phosphorylation of STAT2 on S734 regulated the type I IFN antiviral state. We used total RNA extracted from U6A cells expressing WT-STAT2 or S734A-STAT2 that had been stimulated with or without IFN-α for 4 h. This genomic approach identified 10 ISGs that were induced more by IFN-α in U6A cells expressing S734A-STAT2 than they were in cells expressing WT STAT2 (Fig. 7A; full microarray data is available in the Gene Expression Omnibus under accession number GSE57017). We then selected representative genes from this list to validate by quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR). At 6 h, we consistently detected an enhanced induction of OAS1 and IFIT2 by IFN-α in U6A cells containing S734A-STAT2 compared to that in cells expressing WT-STAT2 (Fig. 7B). Similarly, we found that Stat2−/− MEFs reconstituted with human S734A-STAT2 and stimulated with murine IFN-β showed enhanced transcription of Oas1b and Isg15 when compared to IFN-β-treated MEFs expressing human WT-STAT2 (Fig. 7C). Although differences in Oas1b mRNA levels were not evident until 24 h after IFN-β stimulation, this could be attributed to the activation of human STAT2 in mouse cells. To confirm these results at the protein level, U6A cells reconstituted with either WT-STAT2 or S734A-STAT2 were stimulated with 1000 U/ml of IFN-α for 24 and 60 h and analyzed by western blot analysis for ISG15 and OAS1 expression (Fig. 7D). We found ISG15 protein levels to be similar in WT-STAT2 and S734A-STAT2 U6A cells at 24 h. At 60 h, however, ISG15 protein levels were reduced in WT-STAT2 cells, but remained elevated in S734A-STAT2 cells. In contrast, expression of OAS1 was found to be slightly elevated only at 24 h in S734A-STAT2 cells when compared to WT-STAT2 cells. This observation also correlated with increased STAT2 tyrosine phosphorylation in cells expressing S734A-STAT2 at 24 h, indicating that S734 regulates STAT2 activity. Thus, these results support the idea that phosphorylation of S734-STAT2 contributes to the transcriptional regulation of a small subset of ISGs with antiviral activity.

DISCUSSION

Regulation of type I IFN signaling through STAT2 has remained understudied chiefly because the diversity of STAT TADs and the sequence divergence of the STAT2 TAD among different species have made it challenging to predict amino acids in STAT2 that might be important for proper transcriptional activity (Park et al., 1999; Paulson et al., 1999). For example, serine phosphorylation within the P(M)SP motifs found in several STAT transactivation domains has been shown to be required for STAT-dependent gene regulation. In contrast, STAT2 lacks this conserved motif, and this opens the door to investigate the biological role of serine-phosphorylated STAT2.

Our study provides new evidence that serine phosphorylation of STAT2 plays a pivotal role in selectively regulating the biological actions of type I IFNs. We have identified a serine phosphorylation site (S734) on STAT2 that resides in the TAD, but that is away from the crucial region previously mapped for transactivation. This new site appears to specifically regulate the antiviral activity of type I IFNs, without disturbing the anti-proliferative activity. We consistently show that S734-STAT2 is phosphorylated in response to IFN-α stimulation in several cell lines, with kinetics that are distinctly slower that those observed for STAT2 tyrosine phosphorylation. We found JAK1 activity and STAT2 tyrosine phosphorylation to be necessary for pS734-STAT2 induction. Furthermore, we present evidence that IFN-α-induced pS734-STAT2 translocates to the nucleus. Although the serine kinase responsible for phosphorylating S734 is yet unknown, with the use of prediction tools, we have identified two candidate serine kinases that we are currently evaluating for their role in pS734-STAT2 phosphorylation.

The function of this newly discovered post-translational modification appears to differ from the S287 site we recently identified on STAT2. In response to IFN-α stimulation, disabling phosphorylation of S287-STAT2 has two consequences. First, it augments the growth inhibitory effects of type I IFN and, second, it protects cells from viral infection resulting in prolonged cell survival due to reduced virus replication (Steen et al., 2013), two features not entirely shared with S734-STAT2. Although additional studies are underway to determine the combinatory effect of STAT2 dually phosphorylated on serine residues 287 and 734 in type I IFN signaling, we propose that S734-STAT2 phosphorylation has a specific contributory role in negatively regulating the antiviral effects of type I IFN.

How might phosphorylation of S734-STAT2 negatively regulate type I IFN signaling? Early experiments using U6A cells reconstituted with C-terminally truncated versions of STAT2 showed that deletions up to amino acid 831 did not affect type I IFN signaling and ISG induction (Qureshi et al., 1996). However, removing residues to amino acid 812 led to a partial reduction in STAT2 function, and truncating STAT2 to residue 800 completely disrupted gene induction. The interaction between the STAT2-TAD and p300/CBP has been recently mapped by NMR and confined to amino acids 788–816 of STAT2, with some stabilizing, but non-crucial interactions between residues 817 and 833 (Wojciak et al., 2009). Owing to the deleterious effects of C-terminal truncations after removing the first 50 residues, the importance of the N-terminal part of the TAD (residues ∼700–800) has not been carefully studied. Compared to other STATs, STAT2 has a very large TAD that includes the region C-terminal of Y690. Adding to that, STAT2 is different from all other STATs in that it does not stably interact with DNA (Bluyssen and Levy, 1997). In type I IFN signaling, this task is performed by STAT1 and IRF9, which bind DNA directly while STAT2 contributes its transactivation function to the ISGF3 complex. Therefore, we can postulate that the first part of the STAT2-TAD (from residues ∼700–760) is required to bring the remaining 90 residues (761–851) into a proper conformation for binding to co-activators such as p300/CBP, GCN5 and, most recently, RVB1 and RVB2 proteins (Gnatovskiy et al., 2013).

The S734-STAT2 location, ‘PELSLDLEP’, consists of several leucine residues (hydrophobic) and acidic residues flanked by two proline residues. Interestingly, S734 is found within the mapped nuclear export signal of STAT2 (Frahm et al., 2006). As a serine phosphorylation motif, this was unknown, but remarkably very similar to one present just a few residues upstream in a stretch that starts at amino acid 716 (PELESLELELG). It is worth mentioning that WT-STAT2 and S734A-STAT2 showed identical kinetics in their subcellular localization before and after IFN-β treatment (data not shown). The nature of the STAT2 TAD, which contains both an acidic side and an opposite hydrophobic side, might facilitate its interaction with other proteins. In such a scenario, the phosphorylated serine residue would increase the negative charge on the acidic side, speculatively disrupting relevant STAT2–co-factor interactions at certain ISG loci and resulting in a dampened transcriptional response. Because this particular post-translational modification seems to only affect the level of induction of a select subset of ISGs, we hypothesize that the proteins interacting with STAT2 at the loci of these ISGs are what is providing selectivity that is not seen with other ISGs.

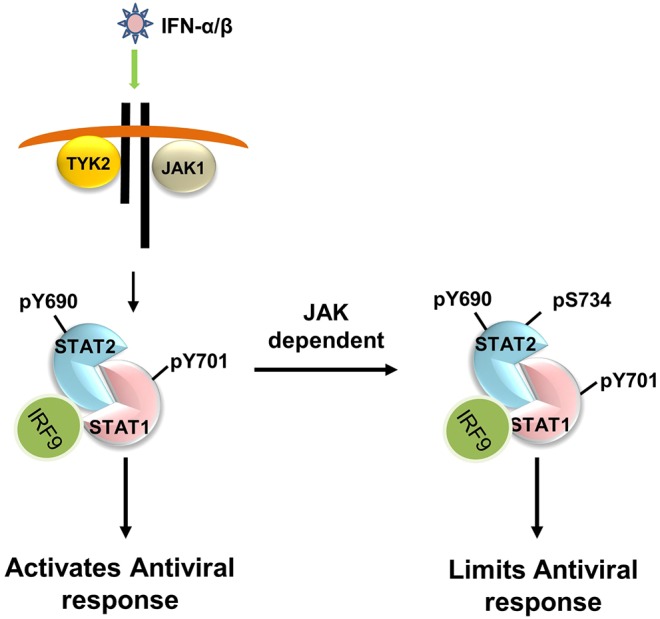

Based on these observations together with our recent report on S287 phosphorylation of STAT2, we propose a preliminary model (Fig. 8) in which dynamic S734 phosphorylation regulates the antiviral activities of type I IFNs. Overall, this discovery highlights striking differences in the role of serine phosphorylation of STAT2 compared to other STATs, including STAT1, wherein phosphorylation on serine enhances, rather than antagonizes, the transcriptional response to type I IFNs.

Fig. 8.

Proposed model of S734-STAT2 phosphorylation in regulating the antiviral activity of type I IFNs. Upon binding of IFN-α and IFN-β to its receptor, JAK1 and TYK2 become activated and tyrosine phosphorylate STAT1 (pY701) and STAT2 (pY690). Activated STAT1 and STAT2, together with IRF9, as the ISGF3 complex, trigger the induction of antiviral ISGs. Subsequently, tyrosine-phosphorylated STAT2 (pY690) is phosphorylated at S734 (pS734) in a JAK-dependent manner, and this in turn, restricts the induction of ISGs with antiviral activity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture

STAT2-deficient human U6A fibrosarcoma cells (obtained from Dr Ana Costa-Pereira, Imperial College London, London, UK), STAT2-null mouse embryonic fibroblasts (provided by Dr Chris Schindler, Columbia University, New York, NY), human colorectal carcinoma cells F6-8 and T29 (obtained from Dr Bert Vogelstein, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD), and 293FT cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Cellgro Mediatech, Inc., Manassas, VA) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (Gemini Bio-Products), 100 units/ml penicillin (Cellgro), 100 μg ml−1 streptomycin (Cellgro), and 1× GlutaMAX (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA). Human fibrosarcoma 2fTGH cells and epithelial mammary cells hTERT-HME1 (kindly provided by Dr George Stark, Cleveland Clinic Foundation, Cleveland, OH) and 293FT cells purchased from Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY) were grown in complete DMEM (Cellgro Mediatech). hTERT-HME1 cells required DMEM further supplemented with mammary epithelium growth medium containing bovine pituitary extract, hydrocortisone, insulin, epithelial growth factor, and gentamicin and amphotericin-B (Clonetics, Basel, Switzerland). All cells were grown at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2, authenticated and checked for contamination.

Reagents and antibodies

Recombinant human IFN-α-2a (specific activity 2×107 units ml−1) was purchased from PeproTech, Inc. (Rock Hill, NJ). Recombinant murine IFN-β was a kind gift from Biogen, Inc. (Cambridge, MA). JAK inhibitor was obtained from EMD Millipore (Bedford, MA). Rabbit anti-STAT2 (C-20, cat. no. sc-476, 1:1000), rabbit anti-STAT1 (E-23, cat. no. sc-346, 1:1000) and rabbit anti-Lamin B1 (C-5, cat. no. sc-365962, 1:1000) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Rabbit anti-phospho-Y689-STAT2 (cat. no. 07-224, 1:1000) was obtained from Millipore, mouse anti-pY701-STAT1 (cat. no. 612233, 1:1000) was purchased from BD Biosciences, mouse anti-GAPDH (cat. no. 60004-1, 1:5000) and mouse anti-actin (cat. no. 60008-1, 1:5000) antibodies were purchased from Proteintech Group, Inc. (Chicago, IL). Affinity purified rabbit polyclonal anti-STAT2-pS734 was raised against the phospho-specific peptide VPEPEL(pS)LDLEPL; amino acids 728–740 in collaboration with Rockland Immunochemicals, Inc. (Gilbertsville, PA).

Plasmids, site-directed mutagenesis and transduction

C-terminally Flag-tagged human STAT2 cDNA vector was obtained from Dr Curt Horvath (Northwestern University, Evanston, IL). Site-directed mutagenesis was performed using the QuikChange Lightning kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) to construct R409A/K415A-(RKAA), Y690F- and S734A-STAT2 mutants. Mutant and wild-type STAT2 constructs were subcloned into the lentiviral expression vectors pCDH-CMV-MCS-EF1-Green and pCDH-CMV-MCS-EF1-RFP (System Biosciences, Mountain View, CA). Lentiviruses were produced in 293FT cells using ViraPower Lentiviral Expression System (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). U6A cells and Stat2−/− MEFs were transduced with lentivirus in the presence of 1 μg ml−1 Polybrene (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and subjected to antibiotic selection by adding 2 μg ml−1 puromycin to the growth medium at 72 h post infection.

Western blotting, nuclear extract preparation and immunoprecipitation

Cells were lysed in Triton X-100 lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 0.5% Triton X-100) supplemented with 1× protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN), 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 1 mM PMSF and 1× phosphatase inhibitor mixture 2 and 3 (Sigma), for 20 min on ice. After centrifugation for 15 min at 4°C and 15,000 g, supernatants were collected and protein concentration was determined with the Bio-Rad protein assay kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Nuclear extracts were prepared as described previously (Steen et al., 2013). Immunoprecipitation assays were performed by first pre-clearing protein lysates by incubation with protein-G–Sepharose (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, UK). Pre-cleared lysates were then incubated with the indicated antibody overnight at 4°C and immunocomplexes collected by further incubation with protein-G–Sepharose for 2 h. Dephosphorylation of STAT2 was performed by adding 400 U of lambda protein phosphatase (LPP; New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) followed by incubation at 37°C for 30 min with constant agitation. Lysates and immunoprecipitates were resolved on NuPAGE 4–12% Bis-Tris gels (Life Technologies) and transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore, Temecula, CA). Membranes were blocked with Blocker Casein TBS (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) and incubated with the corresponding primary and horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies in Tris-buffered saline with 0.2% Tween 20 (TBS-T) plus 3% bovine serum albumin. Membranes were developed by chemiluminescence using SuperSignal West Pico or Femto (Thermo Scientific). Images were captured with the Alpha-Innotech HD2 imaging system (ProteinSimple, San Jose, CA).

Mass spectrometry

STAT2-reconstituted U6A cells were left untreated or treated with 1000 U ml−1 IFN-α for 30 min and proteins were extracted with Triton X-100 lysis buffer. STAT2 was immunoprecipitated and separated by SDS-PAGE. A protein band corresponding to the size of STAT2 (113 kDa) was visualized with Coomassie Blue stain and excised for further analysis. Extracted proteins were treated with Proteinase K prior to mass spectrometry analysis performed by ITSI Biosciences (Johnstown, PA) using an LTQ XL mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific). Resulting mass spectra was searched against a custom STAT2 human database from UniProt using Proteome Discoverer (version 1.3, Thermo Scientific) and the SEAQUEST search engine. Proteins were identified when two or more unique peptides had X-correlation scores greater than 1.5, 2.0 and 2.5 for respective peptide charge states of +1, +2, and +3, together with a delta correlation value of ≥0.1. Carbamidomethyl was used as a static modification. Phosphorylated serine, threonine, and tyrosine along with acetylated residues were variable modifications. Peptide tolerance was set to ±5000 ppm and mass tolerance was ±2 Da.

MTS cell proliferation assay

U6A cells seeded in flat-bottomed 96-well plates at a density of 500 cells per well were treated with or without IFN-α for 72 h at 37°C. Cell growth was determined by using CellTiter 96® AQueous One solution reagent (Promega, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Absorbance was measured at 490 nm using a VICTOR™X5 Multilabel Plate Reader (PerkinElmer Life Sciences, Waltham, MA). Data are shown as a percentage of the value of control (untreated cells).

Virus infection

Cells seeded in 12-well plates were left untreated or treated with increasing doses of IFN-α for 16 h prior to infection with vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) with a GFP-expressing gene (Fernandez et al., 2002). Plaque-purified VSV (Indiana strain) was added to cells at a multiplicity of infection of 0.01 for U6A cells and 0.002 for Stat2−/− MEFs under serum-free medium conditions for 1 h at 37°C. Cells were washed twice with PBS followed by re-addition of complete DMEM. Progeny virion titers were quantified in culture supernatants by standard plaque assay on baby hamster kidney (BHK-21) cells or by flow cytometry.

Quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from cells using RNA Bee solution (Amsbio LLC, Lake Forest, CA). Contaminating DNA was removed (DNA-free Kit, Ambion) and cDNA was synthesized from RNA using the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA). cDNA was combined with gene-specific FAM dye-labeled TaqMan MGB probes (Life Technologies) and 2× TaqMan Master Mix. Real-time analysis was performed using a 7300 real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems). Actin cDNA was used to normalize cDNA loading. Each sample was analyzed in triplicates and normalized against actin. The ΔΔCt method was used to determine differences in gene transcription between WT-STAT2 and S734A-STAT2.

Microarray gene analysis

STAT2-expressing U6A cells were seeded in triplicate and treated with or without 1000 U ml−1 IFN-α for 4 h. Total RNA was isolated using RNA Bee solution and further purified by RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The quality of total RNA was assessed using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). RNA samples were labeled and hybridized to the Affymetrix Human Gene 2.0 ST Array (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA). For each condition, three biological replicate samples were used for microarray experiments. Scanned microarray images were analyzed using the Affymetrix Gene Expression Console with RMA (Robust Multi-array Average) normalization algorithm. Further statistical analyses were performed using BRB-ArrayTools (Simon et al., 2007). Gene classification into ontology categories (GO) was performed using BLAST2GO® version 2.6.4 (Biobam Bioinformatics, Valencia, Spain). The complete data files are available at NCBI, GEO accession number GSE57017.

Statistical analysis

Prism software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA) was used for statistical analysis. Student's t-test was applied to discern significant statistical differences between samples. P≤0.05 was considered significant.

Acknowledgements

We thank Mr Michael Slifker for the analysis of the microarray data. Analyses were performed using the BRB-ArrayTools developed by Dr Richard Simon and BRB-ArrayTools Development Team.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing or financial interests.

Author contributions

A.M.G. prepared the manuscript and designed experiments; H.C.S. and K.P.K. conducted and designed experiments, and helped write the manuscript; S.N. and M.Y.H. conducted some of the experiments, and S.B. helped with manuscript preparation and experimental design.

Funding

This project was supported by grants to A.M.G. from the National Cancer Institute (RO1CA140499) and the Pennsylvania Department of Health. Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

Data availability

The microarray data reported in this study are available from the Gene Expression Omnibus database under accession number GSE57017 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE57017).

Supplementary information

Supplementary information available online at http://jcs.biologists.org/lookup/doi/10.1242/jcs.185421.supplemental

References

- Barbieri G., Velazquez L., Scrobogna M., Fellous M. and Pellegrini S. (1994). Activation of the protein tyrosine kinase tyk2 by interferon alpha/beta. Eur. J. Biochem. 223, 427-435. 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb19010.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya S., Eckner R., Grossman S., Oldread E., Arany Z., D'Andrea A. and Livingston D. M. (1996). Cooperation of Stat2 and p300/CBP in signalling induced by interferon-α. Nature 383, 344-347. 10.1038/383344a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bluyssen H. A. R. and Levy D. E. (1997). Stat2 is a transcriptional activator that requires sequence-specific contacts provided by stat1 and p48 for stable interaction with DNA. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 4600-4605. 10.1074/jbc.272.7.4600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chawla-Sarkar M., Leaman D. W. and Borden E. C. (2001). Preferential induction of apoptosis by interferon (IFN)-beta compared with IFN-alpha2: correlation with TRAIL/Apo2L induction in melanoma cell lines. Clin. Cancer Res. 7, 1821-1831. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darnell J. E., Jr. (1997). STATS and gene regulation. Science 277, 1630-1635. 10.1126/science.277.5332.1630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decker T. and Kovarik P. (2000). Serine phosphorylation of STATs. Oncogene 19, 2628-2637. 10.1038/sj.onc.1203481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Veer M. J., Holko M., Frevel M., Walker E., Der S., Paranjape J. M., Silverman R. H. and Williams B. R. (2001). Functional classification of interferon-stimulated genes identified using microarrays. J. Leukoc. Biol. 69, 912-920. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrar J. D., Smith J. D., Murphy T. L. and Murphy K. M. (2000). Recruitment of Stat4 to the human interferon-a/b receptor requires activated Stat2. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 2693-2697. 10.1074/jbc.275.4.2693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez M., Porosnicu M., Markovic D. and Barber G. N. (2002). Genetically engineered vesicular stomatitis virus in gene therapy: application for treatment of malignant disease. J. Virol. 76, 895-904. 10.1128/JVI.76.2.895-904.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frahm T., Hauser H. and Koster M. (2006). IFN-type-I-mediated signaling is regulated by modulation of STAT2 nuclear export. J. Cell Sci. 119, 1092-1104. 10.1242/jcs.02822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu X.-Y., Kessler D. S., Veals S. A., Levy D. E. and Darnell J. E. Jr. (1990). ISGF-3, the transcriptional activator induced by IFN-a, consists of multiple interacting polypeptide chains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87, 8555-8559. 10.1073/pnas.87.21.8555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu X.-Y., Schindler C., Improta T., Aebersold R. and Darnell J. E. Jr. (1992). The proteins of ISGF-3, the interferon a-induced transcriptional activator, define a gene family involved in signal transduction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89, 7840-7843. 10.1073/pnas.89.16.7840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gnatovskiy L., Mita P. and Levy D. E. (2013). The human RVB complex is required for efficient transcription of type I interferon-stimulated genes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 33, 3817-3825. 10.1128/MCB.01562-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornbeck P. V., Kornhauser J. M., Tkachev S., Zhang B., Skrzypek E., Murray B., Latham V. and Sullivan M. (2012). PhosphoSitePlus: a comprehensive resource for investigating the structure and function of experimentally determined post-translational modifications in man and mouse. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, D261-D270. 10.1093/nar/gkr1122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Improta T., Schindler C., Horvath C. M., Kerr I. M., Stark G. R. and Darnell J. E. Jr. (1994). Transcription factor ISGF-3 formation requires phosphorylated Stat91 protein, but Stat113 protein is phosphorylated independently of Stat91 protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91, 4776-4780. 10.1073/pnas.91.11.4776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus T. A., Lau J. F., Parisien J.-P. and Horvath C. M. (2003). A hybrid IRF9-STAT2 protein recapitulates interferon-stimulated gene expression and antiviral response. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 13033-13038. 10.1074/jbc.M212972200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung S., Qureshi S. A., Kerr I. M., Darnell J. E. Jr and Stark G. R. (1995). Role of STAT2 in the alpha interferon signaling pathway. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15, 1312-1317. 10.1128/MCB.15.3.1312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Leung S., Qureshi S., Darnell J. E. Jr and Stark G. R. (1996). Formation of STAT1-STAT2 heterodimers and their role in the activation of IRF-1 gene transcription by interferon-α. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 5790-5794. 10.1074/jbc.271.10.5790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Leung S., Ker I. M. and Stark G. R. (1997a). Functional subdomains of STAT2 required for preassociation with the alpha interferon receptor and for signaling. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17, 2048-2056. 10.1128/MCB.17.4.2048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Leung S., Kerr I. M. and Stark G. R. (1997b). Functional subdomains of STAT2 required for preassociation with the alpha interferon receptor and for signaling. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17, 2048-2056. 10.1128/MCB.17.4.2048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melen K., Kinnunen L. and Julkunen I. (2001). Arginine/lysine-rich structural element is involved in interferon-induced nuclear import of STATs. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 16447-16455. 10.1074/jbc.M008821200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller M., Briscoe J., Laxton C., Guschin D., Ziemiecki A., Silvennoinen O., Harpur A. G., Barbieri G., Withuhn B. A., Schindler C. et al. (1993). The protein tyrosine kinase JAK1 complements defects in the interferon-α/β and -γ signal transduction. Nature 366, 129-135. 10.1038/366129a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park C., Lecomte M.-J. and Schindler C. (1999). Murine Stat2 is uncharacteristically divergent. Nucleic Acids Res. 27, 4191-4199. 10.1093/nar/27.21.4191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulson M., Pisharody S., Pan L., Gaudagno S., Mui A. L. and Levy D. E. (1999). Stat protein transactivation domains recruit p300/CBP through widely divergent sequences. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 25343-25349. 10.1074/jbc.274.36.25343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulson M., Press C., Smith E., Tanese N. and Levy D. E. (2002). IFN-Stimulated transcription through a TBP-free acetyltransferase complex escapes viral shutoff. Nat. Cell Biol. 4, 140-147. 10.1038/ncb747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pestka S., Krause C. D. and Walter M. R. (2004). Interferons, interferon-like cytokines, and their receptors. Immunol. Rev. 202, 8-32. 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00204.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qureshi S. A., Leung S., Kerr I. M., Stark G. R. and Darnell J. E. Jr. (1996). Function of Stat2 protein in transcriptional activation by alpha interferon. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16, 288-293. 10.1128/MCB.16.1.288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadzak I., Schiff M., Gattermeier I., Glinitzer R., Sauer I., Saalmüller A., Yang E., Schaljo B. and Kovarik P. (2008). Recruitment of Stat1 to chromatin is required for interferon-induced serine phosphorylation of Stat1 transactivation domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 8944-8949. 10.1073/pnas.0801794105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirakawa T., Kawazoe Y., Tsujikawa T., Jung D., Sato S.-i. and Uesugi M. (2011). Deactivation of STAT6 through serine 707 phosphorylation by JNK. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 4003-4010. 10.1074/jbc.M110.168435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiromizu T., Adachi J., Watanabe S., Murakami T., Kuga T., Muraoka S. and Tomonaga T. (2013). Identification of missing proteins in the neXtProt database and unregistered phosphopeptides in the PhosphoSitePlus database as part of the Chromosome-centric Human Proteome Project. J. Proteome Res. 12, 2414-2421. 10.1021/pr300825v [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon R., Lam A., Li M. C., Ngan M., Menenzes S. and Zhao Y. (2007). Analysis of gene expression data using BRB-ArrayTools. Cancer Inform 3, 11-17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steen H. C. and Gamero A. M. (2013). STAT2 phosphorylation and signaling. JAKSTAT 2, e25790 10.4161/jkst.25790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steen H. C., Nogusa S., Thapa R. J., Basagoudanavar S. H., Gill A. L., Merali S., Barrero C. A., Balachandran S. and Gamero A. M. (2013). Identification of STAT2 serine 287 as a novel regulatory phosphorylation site in type I interferon-induced cellular responses. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 747-758. 10.1074/jbc.M112.402529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velazquez L., Mogensen K. E., Barbieri G., Fellous M., Uze G. and Pellegrini S. (1995). Distinct domains of the protein tyrosine kinase tyk2 required for binding of interferon-a/b and for signal transduction. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 3327-3334. 10.1074/jbc.270.7.3327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojciak J. M., Martinez-Yamout M. A., Dyson H. J. and Wright P. E. (2009). Structural basis for recruitment of CBP/p300 coactivators by STAT1 and STAT2 transactivation domains. EMBO J. 28, 948-958. 10.1038/emboj.2009.30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan H., Krishnan K., Lim J. T. E., Contillo L. G. and Krolewski J. J. (1996). Molecular characterization of an alpha interferon receptor 1 subunit (IFNaR1) domain required for TYK2 binding and signal transduction. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16, 2074-2082. 10.1128/MCB.16.5.2074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]