Key Points

Question

Does limiting clinicians to 1 electronic patient record open (restricted) reduce wrong-patient orders vs allowing up to 4 records open concurrently (unrestricted)?

Findings

In this randomized trial that included 3356 clinicians and 4 486 631 order sessions, the error rate in the restricted vs unrestricted group was 90.7 vs 88.0 per 100 000 order sessions, a difference that was not statistically significant. However, clinicians in the unrestricted group completed 66.2% of order sessions with only 1 record open.

Meaning

Although restricting the number of concurrently open electronic patient records did not reduce wrong-patient orders, the proportion of orders placed with a single record open in the unrestricted group limited the study’s power to detect an effect of opening 4 records concurrently.

Abstract

Importance

Recommendations in the United States suggest limiting the number of patient records displayed in an electronic health record (EHR) to 1 at a time, although little evidence supports this recommendation.

Objective

To assess the risk of wrong-patient orders in an EHR configuration limiting clinicians to 1 record vs allowing up to 4 records opened concurrently.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This randomized clinical trial included 3356 clinicians at a large health system in New York and was conducted from October 2015 to April 2017 in emergency department, inpatient, and outpatient settings.

Interventions

Clinicians were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to an EHR configuration limiting to 1 patient record open at a time (restricted; n = 1669) or allowing up to 4 records open concurrently (unrestricted; n = 1687).

Main Outcomes and Measures

The unit of analysis was the order session, a series of orders placed by a clinician for a single patient. The primary outcome was order sessions that included 1 or more wrong-patient orders identified by the Wrong-Patient Retract-and-Reorder measure (an electronic query that identifies orders placed for a patient, retracted, and then reordered shortly thereafter by the same clinician for a different patient).

Results

Among the 3356 clinicians who were randomized (mean [SD] age, 43.1 [12.5] years; mean [SD] experience at study site, 6.5 [6.0] years; 1894 females [56.4%]), all provided order data and were included in the analysis. The study included 12 140 298 orders, in 4 486 631 order sessions, placed for 543 490 patients. There was no significant difference in wrong-patient order sessions per 100 000 in the restricted vs unrestricted group, respectively, overall (90.7 vs 88.0; odds ratio [OR], 1.03 [95% CI, 0.90-1.20]; P = .60) or in any setting (ED: 157.8 vs 161.3, OR, 1.00 [95% CI, 0.83-1.20], P = .96; inpatient: 185.6 vs 185.1, OR, 0.99 [95% CI, 0.89-1.11]; P = .86; or outpatient: 7.9 vs 8.2, OR, 0.94 [95% CI, 0.70-1.28], P = .71). The effect did not differ among settings (P for interaction = .99). In the unrestricted group overall, 66.2% of the order sessions were completed with 1 record open, including 34.5% of ED, 53.7% of inpatient, and 83.4% of outpatient order sessions.

Conclusions and Relevance

A strategy that limited clinicians to 1 EHR patient record open compared with a strategy that allowed up to 4 records open concurrently did not reduce the proportion of wrong-patient order errors. However, clinicians in the unrestricted group placed most orders with a single record open, limiting the power of the study to determine whether reducing the number of records open when placing orders reduces the risk of wrong-patient order errors.

Trial Registration

clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT02876588

This randomized trial compares the risk of wrong-patient orders in an electronic health record (EHR) configuration allowing 1 vs up to 4 concurrently open patient records.

Introduction

In 2016, more than 600 000 patients in US hospitals were estimated to have had an order placed for them that was intended for another patient.1,2,3 Such errors have resulted in serious harm including patient deaths.4 In one study conducted in a large health system, the most frequent type of erroneous outpatient medication orders (1133 errors made by 542 prescribers) was placing orders for the wrong patient.5 This problem has persisted despite implementation of patient identification interventions within electronic health record (EHR) systems, such as verification alerts3,6 and patient photographs,7 and despite a Joint Commission National Patient Safety Goal requiring methods for accurate patient identification in effect since 2003.8

To promote the safe use of health information technology, the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC)9 and The Joint Commission10 issued recommendations that health systems limit the number of records displayed in the EHR to 1 at a time. However, these recommendations cite expert opinion,9,11,12 which reasoned that allowing multiple records open concurrently increases the risk of wrong-patient errors.7,13

Despite these recommendations, there is wide variation in practice. In a US survey of chief information officers, 112 respondents reporting on 167 inpatient and outpatient facilities stated that among EHRs with the capability to open multiple records, 44% allowed 3 or more records open, 38% restricted to 1 record open, and 17% allowed 2 records open.14 Respondents reported weighing concerns about wrong-patient errors against the need for efficiency and seeking to strike a balance between safety and efficiency. Given the lack of evidence, as well as lack of consensus, this randomized trial was conducted to test the hypothesis that a restricted configuration, limiting clinicians to 1 patient record open at a time, would result in significantly fewer wrong-patient orders than an unrestricted configuration allowing up to 4 records open.

Methods

Trial Design and Intervention

This randomized clinical trial was conducted from October 2015 to April 2017 at a large academic medical center in New York to assess the risk of wrong-patient electronic order errors in an EHR system configured to display only 1 vs a maximum of 4 patient records at once. Trial sites included 4 hospitals with a total of 1536 beds, 5 emergency departments (EDs), and 144 outpatient facilities. The protocol and statistical analysis plan are available in Supplement 1. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine and Columbia University Irving Medical Center. Waiver of informed consent was granted for clinicians and patients.

All clinicians with the authority to place electronic orders were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to either a configuration that restricted to 1 patient record open at a time (restricted group) or a configuration that allowed up to 4 patient records open concurrently (unrestricted group). Clinicians were excluded if their workflow either (1) had a defined requirement to open 2 patient records simultaneously (eg, mother-infant services) or (2) bypassed the standard order entry process and therefore would not be captured by the outcome measure (eg, radiologists).

The trial coincided with the implementation of a new EHR system (EpicCare, Epic Systems Corporation) at all study sites, and every eligible clinician was randomized at the time of credentialing in the new system. The previous EHR did not have the capability of opening more than 1 record at a time. An information technology specialist responsible for assigning user templates performed the randomization. A computerized random number generator was used to create a group assignment for each user at the time of randomization, thus ensuring concealed allocation and the inability to predict future assignments to the restricted or unrestricted groups. Then, using an existing feature of the EHR, each clinician was manually assigned to 1 of 2 EHR user-role templates that differed only in the number of patient records allowed open concurrently.

Clinicians could place orders only by opening the patient’s record and there was no requirement to confirm orders or the patient’s identity before the orders were transmitted. In the restricted configuration, clinicians could open and view only 1 patient record at a time. In the unrestricted configuration, clinicians could open and view up to 4 records at once, with patients’ names displayed in separate tabs for each patient along the top of the screen. In both the restricted and unrestricted configurations, the active patient’s name, age, sex, date of birth, location, and attending physician were displayed in the banner at the top of the screen. Switching between patients required a single click in the unrestricted configuration, if both records were open. In the restricted configuration, switching to a different patient record required closing the first patient’s record, then looking up and selecting the second patient. Going back to the first patient’s record required the same process.

Outcomes

The unit of analysis was the order session, defined as a series of orders placed consecutively by a single clinician for a single patient that began with opening the patient’s order file and terminated when an order was placed for another patient or after 60 minutes, whichever occurred first. If a clinician placed orders in the wrong patient’s record, several individual orders may have been entered and subsequently retracted together. Thus, the order session, rather than each order, represented an independent opportunity for a wrong-patient error to occur.

Wrong-patient orders were defined as orders placed for one patient that were intended for another patient, and were identified using the Wrong-Patient Retract-and-Reorder (RAR) measure, a validated measure endorsed by the National Quality Forum.15 The measure uses an electronic query to identify wrong-patient RAR events, defined as 1 or more orders placed for a patient that are retracted (cancelled) by the same clinician within 10 minutes, and then reordered by the same clinician for a different patient within the next 10 minutes. In a validation study, real-time telephone interviews with clinicians demonstrated that 76.2% of RAR events identified by the measure were confirmed to be wrong-patient orders3 (eMethods and eFigure 1 in Supplement 2). The Wrong-Patient RAR measure has been used in studies to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions aimed at decreasing wrong-patient orders, and has been validated and used in varied clinical settings and EHR systems.3,6,16,17,18,19 In this trial, the primary outcome was wrong-patient order sessions, defined as order sessions that included at least 1 wrong-patient RAR event.

To examine clinician utilization of the multiple-records capability in the unrestricted group, an electronic log was created that recorded the number of records open at the time each order was placed. This enabled examination of the proportion of orders and order sessions completed when 1, 2, 3, or 4 records were open.

Data were extracted for all orders (eg, prescriptions, medications, laboratory tests, imaging studies, and other types) placed by randomized clinicians during the trial period. Orders for referrals and consultations were excluded. Data for each order, including order, patient, and clinician characteristics, were extracted retrospectively from the health system data warehouse at the end of the trial period. Using this approach, there were no missing outcome data.

Statistical Analysis

Based on prior experience in this setting, we assumed 100 wrong-patient order sessions per 100 000 order sessions in the unrestricted group and an intraclinician correlation of 0.01. With approximately 1600 clinicians in each randomization group and a trial duration yielding an average of approximately 1300 order sessions per clinician with a coefficient of variation of 1.2, the trial had more than 99% power to detect an odds ratio (OR) of 0.5 (or lower), 96% power to detect an OR of 0.6, and 76% power to detect an OR of 0.7.

The primary analysis included all order sessions performed by clinicians according to their assigned randomization group (as-randomized analysis). The primary outcome variable was dichotomous, indicating whether each order session contained a wrong-patient RAR event, and was reported as the number of wrong-patient order sessions per 100 000 order sessions. To determine the effect of trial group on wrong-patient order sessions, random-effects logistic regression models were used with RAR order sessions as the outcome and randomization group as the independent variable, using clinician as a random intercept to account for nesting of order sessions within clinicians. The effect was estimated using the OR and its 95% CI, and the Wald test of significance was used with a 2-sided α = .05.

Prespecified secondary analyses included subgroup analyses to (1) examine the effect of intervention group stratified by clinical setting and (2) assess clinician utilization of multiple records in the unrestricted group. For subgroup analyses, clinical settings were prespecified and included the ED, inpatient, and outpatient locations, and for inpatient units, included medical/surgical, critical care, pediatrics, and obstetrics units. As in the primary analysis, mixed-effects models were used for each predefined subgroup, with a separate model including interaction terms. The significance of interaction effects was tested by a joint Wald test of the interaction terms’ coefficients.

For the analysis of clinician utilization of the multiple-records capability in the unrestricted group, the percentage of all order sessions were reported when 1, 2, 3, or 4 records were open at the time of ordering, overall and stratified by clinical setting. Because a clinician could open or close patient records while placing a series of orders during a single order session, order sessions that contained orders placed with different numbers of records open were reported as “varying.”

In addition, a post hoc analysis was performed to examine the rate of wrong-patient order sessions by number of records open when orders were placed in the unrestricted group, overall and stratified by clinical setting. The significance of differences was tested using a χ2 test. Because of an administrative error, some clinicians were not assigned to the trial group to which they were randomized. Therefore, all analyses were repeated according to intervention received (as-treated analyses), such that each order or order session was characterized by the clinician’s configuration (restricted or unrestricted) at the time the orders were placed.

In addition, using orders rather than order sessions as the unit of analysis, the number of orders and rate of errors were examined by study group and in each prespecified subgroup (Supplement 2). All analyses were conducted using Stata version 15.1 (StataCorp).

Results

Study Population

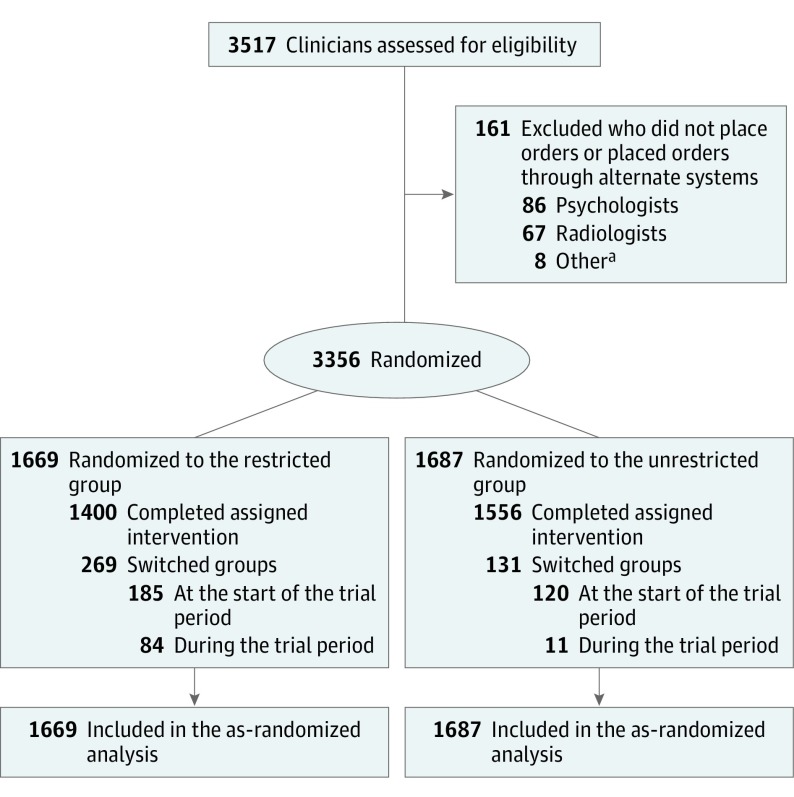

A total of 3356 clinicians were randomized and included in the primary analysis, 1669 in the restricted group and 1687 in the unrestricted group (Figure 1). The analysis included a total of 12 140 298 orders, in 4 486 631 order sessions, placed for 543 490 patients. Characteristics of clinicians, order sessions, and patients are shown in Table 1. Clinician characteristics were similar between groups including age (mean, 42.9 vs 43.2 years), sex (female, 56.0% vs 56.8%), years of experience at the study site (mean, 6.4 vs 6.6), clinician type, and primary practice setting. Order characteristics (medications, laboratory tests, imaging studies, and other types) are reported in eTable 1 in Supplement 2.

Figure 1. Randomization and Assignment of Clinicians.

The primary analysis included all orders placed by clinicians according to their assigned randomization group (as-randomized analysis). Of 3356 clinicians randomized, 400 were not assigned to the trial group to which they were randomized. Of these, 305 were assigned to the opposite group at the beginning of the trial and remained in that group throughout (185 from restricted to unrestricted, 120 from unrestricted to restricted); 95 switched groups during the trial (84 from restricted to unrestricted, 11 from unrestricted to restricted). All assessments were repeated per treatment received (as-treated analysis).

a“Other” included nonclinical staff who were not authorized to place orders.

Table 1. Characteristics of Clinicians, Order Sessions, and Patients.

| Characteristic | Group, No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Restricted (n = 1669)a | Unrestricted (n = 1687)b | |

| Clinicians | ||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 42.9 (12.7) | 43.2 (12.3) |

| Experience at study site, mean (SD), y | 6.4 (6.0) | 6.6 (6.0) |

| Median (IQR) | 4.4 (1.6-10.0) | 4.7 (1.7-10.1) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 734 (44.0) | 728 (43.2) |

| Female | 935 (56.0) | 959 (56.8) |

| Clinician type | ||

| Attending physician | 806 (48.3) | 814 (48.3) |

| House staff | 529 (31.7) | 542 (32.1) |

| Midlevelc | 334 (20.0) | 331 (19.6) |

| Primary practice area | ||

| Outpatient | 835 (50.0) | 876 (51.9) |

| Inpatient | ||

| Medical/surgical | 335 (20.1) | 312 (18.5) |

| Pediatrics | 52 (3.1) | 70 (4.1) |

| Obstetrics | 35 (2.1) | 32 (1.9) |

| Critical care | 8 (1.7) | 18 (1.1) |

| Other | 116 (7.0) | 105 (6.2) |

| Emergency department | 151 (9.0) | 135 (8.0) |

| Unclassified | 117 (7.0) | 139 (8.2) |

| Order sessions | 2 183 365 | 2 303 266 |

| Orders per session, median (IQR) | 1 (1-3) | 2 (1-3) |

| Outpatient | 1 (1-3) | 1 (1-3) |

| Inpatient | 1 (1-3) | 1 (1-3) |

| Emergency department | 2 (1-3) | 2 (1-3) |

| Patients | Overall No. (%) (N = 543 490) | |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 38.4 (4.2) | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 218 642 (40.2) | |

| Female | 324 848 (59.8) | |

| Sessions per patient, median (IQR) | 3 (2-8) | |

| Outpatient | 3 (1-6) | |

| Inpatient | 6 (2-16) | |

| Emergency department | 3 (2-5) | |

Abbreviation: IQR, interquartile range.

In the restricted group, configuration limited to 1 record open at a time.

In the unrestricted group, configuration allowed up to 4 records open concurrently.

Midlevel clinicians include nurse practitioners and physician assistants.

Primary Analysis

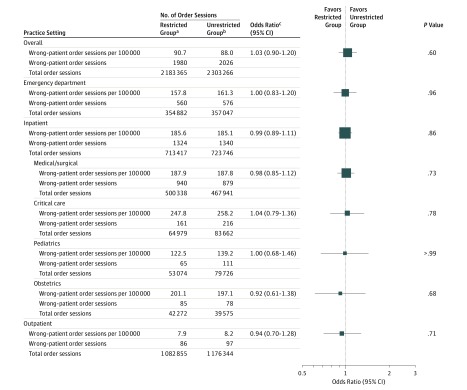

Overall, the proportion of wrong-patient order sessions in the restricted vs unrestricted group was 90.7 vs 88.0 per 100 000 order sessions, respectively (OR, 1.03 [95% CI, 0.90-1.20]; P = .60; absolute difference, 2.7 per 100 000 [95% CI, –2.8 to 8.2]) (Figure 2). Similarly, in subgroup analyses, there were no statistically significant differences in wrong-patient order sessions in the restricted vs unrestricted group in any clinical setting examined: ED, 157.8 vs 161.3 per 100 000 order sessions (OR, 1.00 [95% CI, 0.83-1.20]; P = .96; absolute difference, –3.5 per 100 000 [95% CI, –17.4 to 10.3]); inpatient, 185.6 vs 185.1 per 100 000 order sessions (OR, 0.99 [95% CI, 0.89-1.11]; P = .86; absolute difference, 0.4 per 100 000 [95% CI, –9.3 to 10.2]); or outpatient, 7.9 vs 8.2 per 100 000 order sessions (OR, 0.94 [95% CI, 0.70-1.28]; P = .71; absolute difference, –0.3 per 100 000 [95% CI –8.1 to 7.5]). Within the inpatient setting, critical care and obstetrical units had the highest rates of errors. The intervention effect did not differ among these groups (P for interaction = .99). Results at the order level are presented in eTable 2 in Supplement 2.

Figure 2. Primary Results Comparing Wrong-Patient Order Sessions in the Restricted vs Unrestricted Group.

aIn the restricted group, configuration limited to 1 record open at a time.

bIn the unrestricted group, configuration allowed up to 4 records open concurrently.

cRandom-effects logistic regression models were constructed, using the order session as the unit of analysis and the clinician as the random intercept. The order session, a series of orders placed consecutively by a single clinician for a single patient, represents an independent opportunity for an error to occur. Wrong-patient order sessions were defined as order sessions that included at least 1 wrong-patient Retract-and-Reorder event. The intervention effect did not differ among subgroups defined by practice setting; P for interaction = .99.

As-Treated Analysis

Because of administrative error, a total of 400 clinicians were not assigned to the trial group to which they were randomized. Of these, 305 were assigned to the opposite group at the beginning of the trial and remained in that group throughout (185 randomized to the restricted group and 120 randomized to the unrestricted group); 95 switched groups during the trial (84 from the restricted to unrestricted group and 11 from the unrestricted to restricted group). Study groups in the as-treated analysis did not differ with respect to age, sex, experience, or clinician type. Consistent with the primary analysis, there were no statistically significant differences in wrong-patient order sessions in the restricted vs unrestricted group in the as-treated analysis, overall (OR, 1.03 [95% CI, 0.89-1.19]; P = .68) or in any clinical setting. Clinician characteristics and results for the as-treated analyses at the order session and order level are reported in eTable 3, eFigure 2, and eTable 4, respectively, in Supplement 2).

Utilization in the Unrestricted Group

In the unrestricted group, utilization of the multiple-records capability varied across clinical settings. Overall, clinicians completed 66.2% of order sessions with 1 record open, including 34.5% of ED, 53.7% of inpatient, and 83.4% of outpatient order sessions (Table 2).

Table 2. Utilization and Wrong-Patient Order Sessions by Number of Records Open in the Unrestricted Groupa.

| Open Records | No. of Order Sessions | % of Order Sessionsb | Wrong-Patient Order Sessions per 100 000 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rate (95% CI) | P Valuec | |||

| Overall | ||||

| 1 | 1 523 585 | 66.2 | 52.0 (48.4-55.7) | <.001 |

| 2 | 303 080 | 13.2 | 132.0 (119.4-145.6) | |

| 3 | 168 387 | 7.3 | 165.7 (146.8-186.3) | |

| 4 | 267 697 | 11.6 | 184.5 (168.6-201.5) | |

| Varying | 40 517 | 1.8 | 150.6 (115.2-193.4) | |

| Emergency Department | ||||

| 1 | 123 020 | 34.5 | 122.7 (104.0-143.9) | <.001 |

| 2 | 58 592 | 16.4 | 189.4 (155.9-228.1) | |

| 3 | 48 797 | 13.7 | 207.0 (168.6-251.4) | |

| 4 | 114 155 | 32.0 | 170.8 (147.7-196.5) | |

| Varying | 12 483 | 3.5 | 144.2 (85.5-227.8) | |

| Inpatient | ||||

| 1 | 388 831 | 53.7 | 143.8 (132.1-156.2) | <.001 |

| 2 | 115 367 | 15.9 | 234.9 (207.8-264.6) | |

| 3 | 75 962 | 10.5 | 227.7 (195.1-264.3) | |

| 4 | 125 927 | 17.4 | 236.6 (210.6-265.1) | |

| Varying | 17 659 | 2.4 | 220.9 (157.1-301.8) | |

| Outpatient | ||||

| 1 | 980 558 | 83.4 | 7.3 (5.7-9.2) | .002 |

| 2 | 123 433 | 10.5 | 13.0 (7.4-21.0) | |

| 3 | 39 928 | 3.4 | 10.0 (2.7-25.6) | |

| 4 | 22 355 | 1.9 | 4.5 (0.1-24.9) | |

| Varying | 10 070 | 0.9 | 39.7 (10.8-101.7) | |

In the unrestricted group, configuration allowed up to 4 records open concurrently.

Percentage of order sessions completed with 1, 2, 3, or 4 records open, overall and stratified by clinical setting. Varying order sessions were those in which clinicians placed orders within a single order session with different numbers of records open.

Calculated using χ2 test.

Post Hoc Analysis

In a post hoc analysis of order sessions in the unrestricted group, the number of wrong-patient order sessions completed with 1 record open was 52.0 per 100 000 order sessions (95% CI, 48.4-55.7), 132.0 per 100 000 with 2 records open (95% CI, 119.4-145.6), 165.7 per 100 000 with 3 records open (95% CI, 146.8-186.3), and 184.5 per 100 000 with 4 records open (95% CI, 168.6-201.5) (P < .001). The findings stratified by clinical setting are shown in Table 2. The results of utilization and post hoc analyses at the order level are shown in eTable 5 in Supplement 2.

Discussion

In this randomized trial, an EHR configuration that restricted clinicians to 1 record open at a time did not significantly reduce the rate of wrong-patient order errors compared with a configuration allowing up to 4 records open concurrently. Furthermore, there was no significant difference in any clinical setting examined in both as-randomized and as-treated analyses. However, given the ability to open up to 4 records, clinicians randomized to the unrestricted configuration completed 66% of order sessions with a single record open, limiting the study power to detect a treatment effect. Nonetheless, this study provides evidence that may help to inform national recommendations and local EHR configuration decisions, and raises uncertainty whether restricting the number of records allowed open concurrently reduces wrong-patient errors.

In a post hoc analysis of order sessions in the unrestricted group, there was a graded increase in the rate of errors as more records were open at the time the orders were placed. However, the association between multiple records open and increased risk of error was largely attenuated when the analysis was stratified by clinical setting because most order sessions in the outpatient setting were completed with only 1 record open and were at very low risk for error. It is possible that having multiple records open leads to an increase in the risk of error. Alternatively, having multiple records open may be a marker of a high-risk situation rather than the cause of increased risk. A recent direct observation study demonstrated that multitasking and interruptions were associated with increased rates of prescribing errors, which may be unmeasured confounders in the post hoc analysis reported here.20

In the present study, clinicians in the ED randomized to the unrestricted group completed 66% of order sessions with 2 or more records open, and of all clinical settings placed the highest proportion of orders with the maximum of 4 records open. EDs are considered high-risk settings as clinicians care for multiple acutely ill patients concurrently,20,21,22,23,24 many of whom require complex treatment, in a fast-paced environment characterized by frequent interruptions.25,26,27,28 Because of the demands of the environment and that clinicians in the ED commonly had multiple records open when placing orders, restricting to 1 record might be expected to have the most benefit of any clinical setting. However, results in this setting showed no significant difference in wrong-patient order errors between trial groups, with an OR of 1.00.

To our knowledge, the only prior study evaluating the safety of multiple records in an EHR was an interrupted time series analysis conducted in the ED of a large academic medical center, using the RAR measure as the outcome.19 Results demonstrated no significant decrease in wrong-patient medication orders by limiting the maximum number of records that could be open concurrently from 4 to 2 (85.9 vs 82.9 errors per 100 000 orders) and no increase after transitioning back to a maximum of 4 records (82.2 errors per 100 000 orders) at 2-year intervals.19 Although that study was limited to the ED and used a nonrandomized design, the findings are consistent with the results of this randomized trial conducted in a different health system and using a different EHR.

Although no differences in wrong-patient orders were observed between the restricted group and the unrestricted group in this trial, there was considerable variation in the frequency of errors in different clinical settings. The rate of wrong-patient order errors was lowest in outpatient settings, where clinicians may be more likely to care for 1 patient at a time, and highest in inpatient critical care and obstetrics units. These variations likely reflect differences in workflows and number of patients being cared for simultaneously, and highlight the need for targeted interventions to reduce wrong-patient errors in high-risk settings.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, because clinicians in the unrestricted group completed 66% of order sessions with a single record open, the trial had limited power to detect a treatment effect and consequently does not establish whether reducing the number of records open when placing orders reduces the risk of order errors. However, the trial had sufficient power to test the primary question of whether a restricted vs unrestricted configuration reduces wrong-patient orders.

Second, the RAR measure identifies a single type of near-miss, wrong-patient error detected and corrected within a 20-minute timeframe. It was not designed to capture all wrong-patient errors and its sensitivity is unknown, as are the number and distribution of wrong-patient errors that the measure may have missed. However, the RAR measure systematically quantifies near-miss, wrong-patient order errors; provides sufficient outcome events to power research studies; and is not susceptible to reporting bias as is voluntary error reporting. Furthermore, the use of near-miss errors to test safety interventions in health care is endorsed by the major organizations dedicated to patient safety.29,30,31,32,33

Third, because participants were aware of the study, they may have altered their behavior, thus biasing results toward the null (ie, the Hawthorne effect). While participants may have been aware of the study, it is unlikely that a large number of clinicians could maintain vigilance in their usual workflows over the extended trial period as to substantially reduce errors. Fourth, approximately 10% of study participants were not assigned to their randomized group. However, all analyses were repeated in as-treated analyses (per treatment received) and yielded consistent results (presented in eTables 3 and 4 and eFigure 3 in Supplement 2). Fifth, although this multisite trial included 4 hospitals, 5 EDs, and 144 outpatient settings, it was conducted within a single health system using a single EHR platform and therefore results may not be generalizable to other medical centers and EHR systems.

Conclusions

A strategy that limited clinicians to only 1 EHR patient record open compared with a strategy that allowed up to 4 records open concurrently did not reduce the proportion of wrong-patient order errors. However, clinicians in the unrestricted group placed most orders with a single record open, limiting the power of the study to determine whether reducing the number of records open when placing orders reduces the risk of wrong-patient order errors.

Trial Protocol and Statistical Analysis Plan

eMethods 1. Retract-and-Reorder Methodology

eFigure 1. Wrong-Patient Retract-and-Reorder Measure

eFigure 2. Primary Results Comparing Wrong-Patient Order Sessions in the Restricted vs Unrestricted Group (As-Treated Analysis)

eTable 1. Order Characteristics.

eTable 2. Wrong-Patient Orders in the Restricted vs Unrestricted Group (As-Randomized Analysis)

eTable 3. Baseline Clinician Characteristics (As-Treated Analysis)

eTable 4. Wrong-Patient Orders in the Restricted vs Unrestricted Group (As-Treated Analysis)

eTable 5. Utilization and Wrong-Patient Orders by Number of Records Open in the Unrestricted Group

eReferences

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Lucas JW, Benson V Table P-10a: age-adjusted percent distribution (with standard errors) of number of overnight hospital stays during the past 12 months, by selected characteristics. National Center for Health Statistics, 2018. https://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/Health_Statistics/NCHS/NHIS/SHS/2016_SHS_Table_P-10.pdf. Accessed July 1, 2018.

- 2.US Census Bureau PD Annual estimates of the resident population: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2016: 2016 population estimates. https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=PEP_2016_PEPANNRES&prodType=table. Accessed July 1, 2018.

- 3.Adelman JS, Kalkut GE, Schechter CB, et al. . Understanding and preventing wrong-patient electronic orders: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2013;20(2):305-310. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2012-001055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grissinger M. Oops, sorry, wrong patient! a patient verification process is needed everywhere, not just at the bedside. P T. 2014;39(8):535-537. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hickman TT, Quist AJL, Salazar A, et al. . Outpatient CPOE orders discontinued due to ‘erroneous entry’: prospective survey of prescribers’ explanations for errors. BMJ Qual Saf. 2018;27(4):293-298. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2017-006597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Green RA, Hripcsak G, Salmasian H, et al. . Intercepting wrong-patient orders in a computerized provider order entry system. Ann Emerg Med. 2015;65(6):679-686.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2014.11.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hyman D, Laire M, Redmond D, Kaplan DW. The use of patient pictures and verification screens to reduce computerized provider order entry errors. Pediatrics. 2012;130(1):e211-e219. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Joint Commission 2018 Hospital national patient safety goals. https://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/6/2018_HAP_NPSG_goals_final.pdf. Accessed October 11, 2018.

- 9.Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology Self-assessment: patient identification: general instructions for the SAFER Self-Assessment Guides. https://www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/safer/guides/safer_patient_identification.pdf. Published September 2016. Accessed December 9, 2018.

- 10.Joint Commission Safe use of health information technology. Sentinel Event Alert. http://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/18/SEA_54.pdf. Published March 15, 2015. Accessed July 27, 2018.

- 11.Lowry SZ, Quinn MT, Ramaiah M, et al. Technical evaluation, testing, and validation of the usability of electronic health records. https://www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/safer/guides/safer_patient_identification.pdf. Published February 2012. Accessed April 5, 2019.

- 12.Paparella SF. Accurate patient identification in the emergency department: meeting the safety challenges. J Emerg Nurs. 2012;38(4):364-367. doi: 10.1016/j.jen.2012.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levin HI, Levin JE, Docimo SG. “I meant that med for Baylee not Bailey!”: a mixed method study to identify incidence and risk factors for CPOE patient misidentification. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2012;2012:1294-1301. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adelman JS, Berger MA, Rai A, et al. . A national survey assessing the number of records allowed open in electronic health records at hospitals and ambulatory sites. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2017;24(5):992-995. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocx034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Quality Forum Patient safety 2015: final technical report. http://www.qualityforum.org/WorkArea/linkit.aspx?LinkIdentifier=id&ItemID=81724. Published February 12, 2016. Accessed July 27, 2018.

- 16.Adelman J, Aschner J, Schechter C, et al. . Use of temporary names for newborns and associated risks. Pediatrics. 2015;136(2):327-333. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-0007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adelman JS, Aschner JL, Schechter CB, et al. . Evaluating serial strategies for preventing wrong-patient orders in the NICU. Pediatrics. 2017;139(5):e20162863. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-2863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lombardi D, Gaston-Kim J, Perlstein D, et al. . Preventing wrong-patient electronic orders in the emergency department. J Clin Outcomes Manag. 2016;23(12):550-554. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kannampallil TG, Manning JD, Chestek DW, et al. . Effect of number of open charts on intercepted wrong-patient medication orders in an emergency department. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2018;25(6):739-743. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocx099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Westbrook JI, Raban MZ, Walter SR, Douglas H. Task errors by emergency physicians are associated with interruptions, multitasking, fatigue and working memory capacity: a prospective, direct observation study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2018;27(8):655-663. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2017-007333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Camargo CA Jr, Tsai CL, Sullivan AF, et al. . Safety climate and medical errors in 62 US emergency departments. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;60(5):555-563.e20. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2012.02.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Epstein SK, Huckins DS, Liu SW, et al. . Emergency department crowding and risk of preventable medical errors. Intern Emerg Med. 2012;7(2):173-180. doi: 10.1007/s11739-011-0702-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Magid DJ, Sullivan AF, Cleary PD, et al. . The safety of emergency care systems: results of a survey of clinicians in 65 US emergency departments. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;53(6):715-23.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smits M, Groenewegen PP, Timmermans DR, van der Wal G, Wagner C. The nature and causes of unintended events reported at ten emergency departments. BMC Emerg Med. 2009;9:16. doi: 10.1186/1471-227X-9-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Walter SR, Li L, Dunsmuir WTM, Westbrook JI. Managing competing demands through task-switching and multitasking: a multi-setting observational study of 200 clinicians over 1000 hours. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23(3):231-241. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2013-002097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ratwani RM, Fong A, Puthumana JS, Hettinger AZ. Emergency physician use of cognitive strategies to manage interruptions. Ann Emerg Med. 2017;70(5):683-687. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2017.04.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chisholm CD, Dornfeld AM, Nelson DR, Cordell WH. Work interrupted: a comparison of workplace interruptions in emergency departments and primary care offices. Ann Emerg Med. 2001;38(2):146-151. doi: 10.1067/mem.2001.115440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Westbrook JI, Coiera E, Dunsmuir WT, et al. . The impact of interruptions on clinical task completion. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010;19(4):284-289. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2009.039255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aspden P, Corrigan JM, Wolcott J, Erickson SM, eds. Patient Safety: Achieving a New Standard for Care. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Quality Interagency Coordination Task Force Doing what counts for patient safety: federal actions to reduce medical errors and their impact. https://archive.ahrq.gov/quic/Report/errors6.pdf. Published February 2000. Accessed July 27, 2018.

- 31.Leape L, Abookire S WHO draft guidelines for adverse event reporting and learning systems: from information to action. World Health Organization. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/69797/WHO-EIP-SPO-QPS-05.3-eng.pdf. Published 2005. Accessed July 27, 2018.

- 32.Institute for Healthcare Improvement Create a reporting system. http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/Changes/CreateaReportingSystem.aspx. Accessed July 27, 2018.

- 33.Wu AW, ed. The Value of Close Calls in Improving Patient Safety: Learning How to Avoid and Mitigate Patient Harm. Oakbrook Terrace, IL: Joint Commission Resources; 2011. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol and Statistical Analysis Plan

eMethods 1. Retract-and-Reorder Methodology

eFigure 1. Wrong-Patient Retract-and-Reorder Measure

eFigure 2. Primary Results Comparing Wrong-Patient Order Sessions in the Restricted vs Unrestricted Group (As-Treated Analysis)

eTable 1. Order Characteristics.

eTable 2. Wrong-Patient Orders in the Restricted vs Unrestricted Group (As-Randomized Analysis)

eTable 3. Baseline Clinician Characteristics (As-Treated Analysis)

eTable 4. Wrong-Patient Orders in the Restricted vs Unrestricted Group (As-Treated Analysis)

eTable 5. Utilization and Wrong-Patient Orders by Number of Records Open in the Unrestricted Group

eReferences

Data Sharing Statement