Abstract

Background

Molidustat, a novel hypoxia-inducible factor-prolyl hydroxylase inhibitor, is being investigated for the treatment of anemia associated with chronic kidney disease (CKD). The efficacy and safety of molidustat were recently evaluated in three 16-week phase 2b studies. Here, we report the results of two long-term extension studies of molidustat.

Methods

Both studies were parallel-group, open-label, multicenter studies of ≤36 months' duration, in patients with anemia due to CKD, and included an erythropoiesis-stimulating agent as active control. One study enrolled patients not receiving dialysis (n = 164), and the other enrolled patients receiving hemodialysis (n = 88). The primary efficacy variable for both studies was change in blood hemoglobin (Hb) level from baseline to each post-baseline visit, and safety outcomes included adverse events (AEs).

Results

In patients not on dialysis, the mean ± SD Hb concentrations at baseline were 11.28 ± 0.55 g/dL for molidustat and 11.08 ± 0.51 g/dL for darbepoetin. The mean ± SD blood Hb concentrations throughout the study (defined as mean of each patient's overall study Hb levels) were 11.10 ± 0.508 and 10.98 ± 0.571 g/dL in patients treated with molidustat and darbepoetin, respectively. Similar proportions of patients reported at least one AE in the molidustat (85.6%) and darbepoetin (85.7%) groups. In patients on dialysis, mean ± SD Hb levels at baseline were 10.40 ± 0.70 and 10.52 ± 0.53 g/dL in the molidustat and epoetin groups, respectively. The mean ± SD blood Hb concentrations during the study were 10.37 ± 0.56 g/dL in the molidustat group and 10.52 ± 0.47 g/dL in the epoetin group. Proportions of patients who reported at least one AE were 91.2% in the molidustat group and 93.3% in the epoetin group.

Conclusions

Molidustat was well tolerated for up to 36 months and appears to be an effective alternative to darbepoetin and epoetin in the long-term management of anemia associated with CKD.

Keywords: Anemia, Chronic kidney disease, Efficacy, Molidustat, Safety

Introduction

Anemia is a frequent and serious complication of chronic kidney disease (CKD) and is associated with reduced quality of life and increased incidence of cardiovascular disease, hospitalizations, cognitive impairment, and mortality [1, 2]. In addition, increased severity of anemia is an independent risk factor for mortality [3]. Reduced erythropoietin (EPO) synthesis in the kidneys is a major contributor to anemia associated with CKD [4]. Recombinant human EPO (rhEPO) and its analogs mimic the actions of endogenous EPO and are the standard treatment for patients with anemia due to CKD [5]. Although rhEPO and its analogs are effective in elevating hemoglobin (Hb) levels in the majority of patients with anemia due to CKD, there are growing concerns that their use may lead to adverse events (AEs) including elevated blood pressure, seizures, and increased rate of vascular access thrombosis [6, 7]. The use of rhEPO and its analogs to target Hb levels of 13 g/dL or higher is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular events [8, 9].

A new therapeutic agent being investigated for anemia associated with CKD is molidustat (BAY 85-3934), which is an orally bioavailable inhibitor of hypoxia-inducible factor-prolyl hydroxylase (HIF-PH). HIFs regulate the physiological response to hypoxia by activating the transcription of EPO and other genes that may protect against hypoxia. In the presence of oxygen, HIF-PH hydroxylates the HIF-α subunit, which is then targeted for proteasomal degradation, preventing EPO synthesis. Molidustat inhibits HIF-PH, allowing the accumulation of HIF, which then translocates to the nucleus where it activates the transcription of EPO and other hypoxia-inducible genes, thereby increasing endogenous EPO levels. Preclinical studies revealed that molidustat is effective in raising hematocrit levels via production of endogenous EPO levels to a normal physiological range [10, 11, 12].

The efficacy, safety, and tolerability of molidustat were recently evaluated in 3 phase 2b 16-week studies as part of the DIALOGUE (DaIly orAL treatment increasing endOGenoUs EPO) program and were reported previously [13]. DIALOGUE 1 (D1) was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of molidustat for the treatment of anemia in patients with CKD not previously treated with an analog of rhEPO, and who were not receiving dialysis treatment [13]. DIALOGUE 2 (D2) was an open-label, variable-dose study comparing molidustat with the rhEPO analog darbepoetin alfa (subsequently referred to as darbepoetin) to assess treatment efficacy maintenance of renal anemia in patients with CKD previously treated with an analog of rhEPO, and who were not receiving dialysis treatment [13]. Finally, DIALOGUE 4 (D4) was an open-label, variable-dose trial comparing molidustat with the rhEPO analog epoetin alfa or beta (subsequently referred to as epoetin) and assessed treatment efficacy maintenance of renal anemia in patients with CKD who were receiving dialysis and were previously treated with an analog of rhEPO [13]. Molidustat was generally well tolerated in all 3 studies, with most AEs being of mild or moderate severity [13].

Understanding the long-term effects of HIF-PH inhibitors is of paramount importance because CKD requires life-long treatment. Here, we report data from DIALOGUE 3 (D3) and DIALOGUE 5 (D5), the first long-term extension studies of this new class of drug. D3 is a long-term extension study to D1 and D2, and D5 is a long-term extension study to D4. These extension studies were designed to determine the long-term efficacy and safety of molidustat in patients with anemia associated with CKD.

Materials and Methods

Study Objectives

D3 and D5 were conducted to investigate the long-term efficacy of molidustat in maintaining blood Hb levels within the target range, as well as its safety and tolerability compared with darbepoetin or epoetin (ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers: NCT02055482 and NCT02064426, respectively).

Study Designs

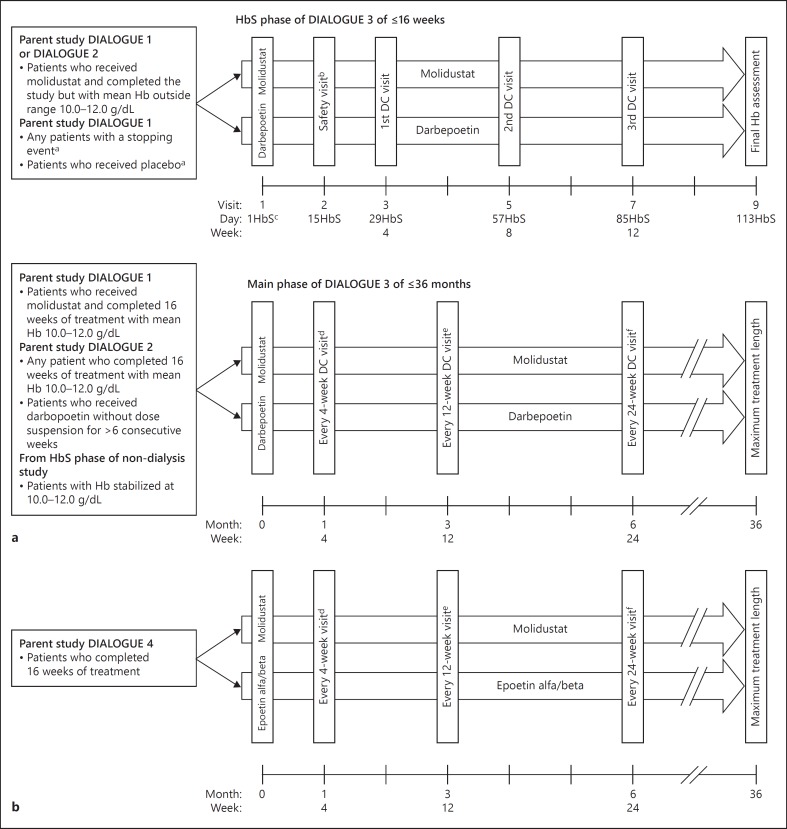

Both study designs are shown in Figure 1.

Fig. 1.

Study design of (a) DIALOGUE 3 and (b) DIALOGUE 5. a In the case of a patient who received placebo and completed DIALOGUE 1, eligibility for entry into the extension study could be reassessed ≤4 weeks after the DIALOGUE 1 end of treatment visit. b A safety visit was required only for patients in the darbepoetin arm and for patients in the molidustat arm who did not complete the day 15 safety visit or who had an Hb stopping event after day 15 in DIALOGUE 1. c ‘HbS' denotes the numbering of days in the HbS phase. d Every 4 (±1) weeks: Hb, dose decision. e Every 12 (±2) weeks: Hb, dose decision, and central laboratory tests. f Every 24 (±2) weeks: Hb, dose decision. DC, dose control; Hb, hemoglobin; HbS, Hb-stabilization.

D3, a long-term extension of D1 and D2, was a controlled, parallel-group, open-label, multicenter study for ≤36 months, in patients not receiving dialysis. Patients continued to receive the same active treatment as in the parent studies; those who had received placebo in D1 were switched to darbepoetin. This study comprised 2 concurrent phases: the Hb-stabilization phase (≤16 weeks) and the main phase (≤36 months). The purpose of the Hb-stabilization phase was to individualize the dose to achieve a stable Hb level of 10.0–12.0 g/dL. Patients achieving a mean Hb level of 10.0–12.0 g/dL for at least 2 consecutive visits in the Hb-stabilization phase could enter the main phase of the study. Patients who did not achieve the target Hb level by week 16 of the Hb-stabilization phase were withdrawn from the study. Patients who completed treatment in D1 and D2 with a mean Hb concentration within the target range during the evaluation period could enter the main phase directly.

D5, a long-term extension of D4, was a controlled, parallel-group, open-label, multicenter study for ≤36 months in patients on dialysis with renal anemia. Patients continued to receive the same treatment as in the parent study.

Patients

D3 included patients who either experienced a stopping event, defined as Hb ≥13.0 g/dL, Hb < 8.0 g/dL, or an Hb increase > 1 g/ dL in 2 weeks, in D1 or completed the treatment period in D1 or D2. Patients who experienced a stopping event in the fixed-dose D1 study were allowed to participate in the Hb-stabilization phase of the extension study because the dose-titration methodology utilized in the extension study could prevent the stopping events previously observed and result in a stable blood Hb level of 10.0–12.0 g/dL required to enter the main phase of the study. D5 included patients who completed the end-of-treatment visit in D4. Key inclusion and exclusion criteria that apply to both extension studies are summarized in online supplementary Table 1 (for all online suppl. material see www.karger.com/doi/10.1159/000499111), and additional inclusion criteria specific to each study in online supplementary Table 2.

Study Treatment

In D3, patients randomized to placebo in D1 entered the Hb-stabilization phase and received darbepoetin. Patients entering D3 from D1 were titrated to an individually optimized dose, and those entering from D2 received an initial dose of active drug based on their treatment regimen and Hb level upon exiting the parent study. In the Hb-stabilization phase, a safety visit was performed at day 15 for patients new to darbepoetin, or patients receiving molidustat who did not complete the day 15 safety visit in D1 or who had a stopping event after day 15 in D1.

In D5, the initial dose in both treatment arms was based on the dose that patients received at the end of treatment in the parent study. The daily available doses included 15, 25, 50, 75, 100, and 150 mg.

In D3 and D5, dose regimens were adapted every 4 (± 1) weeks for each patient based on their Hb response to the prior dose. Molidustat could be titrated up if blood Hb concentrations were < 10.2 g/dL in D3 and < 9.7 g/dL in D5. Molidustat doses could be titrated down if blood Hb concentrations were > 11.7 g/dL in D3 and > 11.2 g/dL in D5. The dose was suspended if the blood Hb concentration was > 13.0 g/dL or if the rise in Hb level was >1.0 g/dL in 2 weeks. The daily average doses of molidustat in D3 and D5 are reported in online supplementary Table 3. Darbepoetin and epoetin were dosed according to prescribing information and standard practice of the site. In both studies, oral and intravenous iron supplementation was dosed according to site standards at the discretion of the physician to maintain adequate levels during the study.

Efficacy Endpoints

In both extension studies, the primary efficacy variable was the change in blood Hb level from baseline to each post-baseline visit during the main phase of the study. Results were reported for the efficacy evaluation period of 52 weeks. For patients entering D5 or the main phase of D3 directly, baseline was defined as the average blood Hb concentrations in the evaluation period of the parent study. For patients entering the main phase of D3 from the Hb-stabilization phase, baseline was defined as the average blood Hb concentrations of the last 2 visits of the Hb-stabilization phase. In D3, the goal was to maintain Hb concentrations within the range 10.0–12.0 g/dL; in D5, the Hb target range was 10.0–11.0 g/dL.

Safety Endpoints

Safety outcomes included AEs and serious AEs. A central adjudication committee consisting of independent clinical experts adjudicated protocol-specified AEs in a treatment-blinded manner. Adjudicated events included death and serious AEs of the following: severe arrhythmias, thromboembolic events (excluding hemodialysis vascular access events), syncope, symptomatic hypotension, and heart failure. Additionally, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and conversion to end-stage kidney disease, defined as either onset of dialysis treatment or eGFR < 15 mL/min/1.73 m2, were reported for D3.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using descriptive statistical methods, and in both extension studies, efficacy was analyzed using observed case data from the modified intention-to-treat (mITT) set, defined as patients who received at least one dose of study medication during the study, and had at least one post-baseline Hb value (in the main phase only in D3). In both extension studies, the safety analysis set population, defined as all patients who received at least one dose of study medication, was used for the summary of all safety variables. Both efficacy and safety analyses were based on the actual treatment received.

The statistical evaluation was performed by using the Hosted SAS version release 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Ethics

All studies were conducted in compliance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and in accordance with Good Clinical Practice guidelines. The protocols were reviewed and approved by the institutional review board or Ethics Committee of each participating center. All patients provided written informed consent before study entry.

Results

Populations

Demographics and baseline characteristics for both studies are summarized in Table 1, and patient disposition is described in online supplementary Tables 4 and 5. Of the 164 patients enrolled in D3, 160 (118 molidustat, 42 darbepoetin) were included in the safety population and 144 (103 molidustat, 41 darbepoetin) in the mITT population used for efficacy evaluation. Of the 88 patients enrolled in D5, 87 (57 molidustat, 30 epoetin) were included in the safety population and 86 (56 molidustat, 30 epoetin) in the mITT population used for efficacy evaluation.

Table 1.

Patient demographics and baselinea characteristics (safety population)

| DIALOGUE 3 | Molidustat (n = 118) | Darbepoetin (n = 42) | Total (n = 160) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yearsb | |||

| Mean (SD) | 70 (10) | 69 (12) | 69 (11) |

| Min, max | 35, 89 | 34, 94 | 34, 94 |

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Male | 57 (48) | 22 (52) | 79 (49) |

| Female | 61 (52) | 20 (48) | 81 (51) |

| Race, n (%) | |||

| White | 73 (62) | 32 (76) | 105 (66) |

| Black | 0 | 1 (2) | 1 (0.6) |

| Asian | 45 (38) | 9 (21) | 54 (34) |

| Parent study, n (%) | |||

| DIALOGUE 1 | 66 (56) | 17 (40) | 83 (52) |

| DIALOGUE 2 | 52 (44) | 25 (60) | 77 (48) |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2 at baselinec | |||

| n | 111 | 42 | 153 |

| Mean (SD) | 23 (14) | 22 (13) | 23 (15) |

| Min, max | 5, 67 | 7, 54 | 5, 67 |

| eGFR category at baseline, n (%)c | |||

| <15 mL/min/1.73 m2, stage 5 | 42 (36) | 16 (38) | 58 (36) |

| 15 to <30 mL/min/1.73 m2, stage 4 | 37 (31) | 17 (40) | 54 (34) |

| 30 to <60 mL/min/1.73 m2, stage 3 | 30 (25) | 9 (21) | 39 (24) |

| Missing | 9 (8) | 0 | 9 (6) |

| Etiology of CKD (reported for ≥5% of patients in any group), n (%)d | |||

| Hypertension | 48 (41) | 15 (36) | 63 (39) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 43 (36) | 16 (38) | 59 (37) |

| Autoimmune disease | 9 (8) | 5 (12) | 14 (9) |

| Infection | 9 (8) | 3 (7) | 12 (8) |

| Polycystic kidney disease | 5 (4) | 3 (7) | 8 (5) |

| CRP | |||

| Mean (SD), mg/L | 5.1 (10.2) | 10.8 (21.6) | 6.7 (14.4) |

| DIALOGUE 5 | Molidustat (n = 57) | Epoetin (n = 30) | Total (n = 87) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yearsb | |||

| Mean (SD) | 61 (12) | 59 (9) | 60 (11) |

| Min, max | 25, 82 | 39, 74 | 25, 82 |

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Male | 33 (58) | 23 (77) | 56 (64) |

| Female | 24 (42) | 7 (23) | 31 (36) |

| Race, n (%) | |||

| White | 28 (49) | 14 (47) | 42 (48) |

| Black | 16 (28) | 10 (33) | 26 (30) |

| Asian | 10 (18) | 6 (20) | 16 (18) |

| Others | 2 (4) | 0 | 2 (2) |

| Not reported | 1 (2) | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Dialysis frequency, n (%) | |||

| 3 times per week | 57 (100) | 30 (100) | 87 (100) |

| Etiology of CKD (reported for >5% of patients in any group),n (%)d | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 30 (53) | 18 (60) | 48 (55) |

| Hypertension | 19 (33) | 12 (40) | 31 (36) |

| Others | 6 (11) | 0 | 6 (7) |

| Glomerulonephritis | 3 (5) | 2 (7) | 5 (6) |

| Polycystic kidney disease | 1 (2) | 0 | 1 (1) |

| CRP | |||

| Mean (SD), mg/L | 0.7 (1.2) | 0.6 (0.8) | 0.7 (1.1) |

Baseline measurement was defined as the measurement taken prior to the first study drug administration in the extension studies.

Age was defined as the baseline value of the parent studies.

eGFR was calculated using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease formula.

One patient could have more than 1 etiology. CKD, chronic kidney disease; CRP, C-reactive protein; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; max, maximum; min, minimum.

Treatment Exposure

In D3, the mean ± SD treatment durations (i.e., times from first dose to last dose) were 430.5 ± 211.2 days for darbepoetin and 375.0 ± 210.0 days for molidustat. The minimum duration of exposure to molidustat was 6 days, and the maximum was 760 days. The mean ± SD daily dose per patient was 40.2 ± 30.3 mg in the molidustat group and 2.4 ± 2.0 µg in the darbepoetin group (online suppl. Table 3).

In D5, the mean ± SD treatment duration was shorter in the molidustat group (358.7 ± 224.8 days) than in the epoetin group (473.0 ± 226.1 days). The mean ± SD daily dose per patient was 69.7 ± 47.8 mg in the molidustat group and 1,087.4 ± 764.3 IU in the epoetin group (online suppl. Table 3).

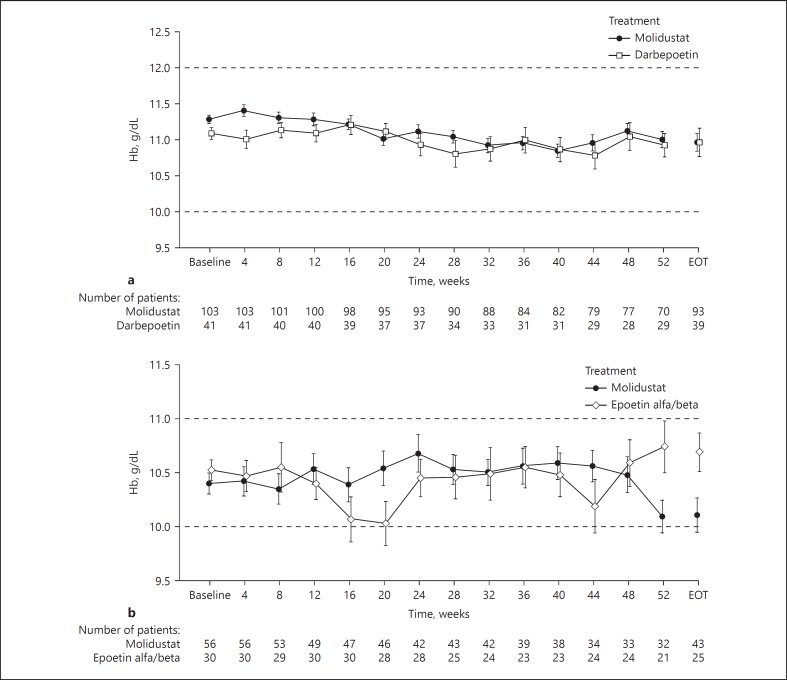

Efficacy Outcomes

In D3, the mean change in blood Hb concentration from baseline to week 52 was < 0.5 g/dL in both the molidustat and darbepoetin groups. The mean ± SD blood Hb concentration remained stable in both the molidustat group (11.3 ± 0.6 g/dL at baseline; 11.0 ± 0.9 g/dL at week 52) and the darbepoetin group (11.1 ± 0.5 g/dL at baseline; 10.9 ± 0.9 g/dL at week 52; Fig. 2a). The mean blood Hb concentrations were similar across the molidustat and darbepoetin groups and remained within the target range during the study (Fig. 2a). The mean ± SD blood Hb concentrations throughout treatment (defined as the mean of each patient's overall study Hb levels) were 11.1 ± 0.5 and 11.0 ± 0.6 g/dL in patients treated with molidustat and darbepoetin, respectively. In D5, the mean change in blood Hb concentration from baseline to week 52 was < 0.5 g/dL in both the molidustat and epoetin groups. The mean ± SD blood Hb levels remained stable in both the molidustat group (10.4 ± 0.7 g/dL at baseline; 10.1 ± 0.8 g/dL at week 52) and the epoetin group (10.5 ± 0.5 g/dL at baseline; 10.7 ± 1.1 g/dL at week 52; Fig. 2b). The mean ± SD blood Hb concentrations during the treatment were 10.4 ± 0.6 g/dL in the molidustat group and 10.5 ± 0.5 g/dL in the epoetin group.

Fig. 2.

The mean (SE) blood Hb concentrations at visits up to week 52 and at end of treatment using observed case data in (a) DIALOGUE 3 and (b) DIALOGUE 5. In DIALOGUE 3, for patients entering the main phase directly, baseline Hb was based on the average of scheduled Hb values from the last 4 visits in the parent study (evaluation period); for patients entering the main phase from the Hb-stabilization phase, baseline was defined as the average blood Hb concentrations of the last 2 visits of the Hb-stabilization phase. In DIALOGUE 5, the baseline Hb value was based on the average of scheduled Hb values from the last 4 visits of the parent study (the evaluation period). EOT, end-of-treatment; Hb, hemoglobin.

Safety Outcomes

In D3, similar proportions of patients reported at least one AE in the molidustat group (86% [101/118 patients]) and in the darbepoetin group (86% [36/42 patients]; online suppl. Table 6). AEs reported in at least 10% of patients in any group are summarized in online supplementary Table 7. The proportions of patients who experienced AEs considered by the investigator to be drug-related were 7% (8/118) in the molidustat group and 5% (2/42) in the darbepoetin group (Table 2). Most drug-related AEs were mild or moderate in severity and resolved without any medication. Similar proportions of patients in the molidustat (47% [56/118]) and darbepoetin (52% [22/42]) groups reported serious AEs (online suppl. Table 6). A larger proportion of patients in the molidustat group (21% [25/118]) withdrew from treatment compared with those in the darbepoetin group (10% [4/42]). Among patients who discontinued, 5 (all in the molidustat arm) had AEs considered to be treatment-related (atrial tachycardia, intestinal adenocarcinoma, blood creatine phosphokinase increase, melena, and Hb increase). The mean ± SD change in eGFR from baseline to end of treatment was −0.8 ± 6.5 mL/min/1.73 m2 in the molidustat group and −1.9 ± 5.5 mL/min/1.73 m2 in the darbepoetin group, and the proportion of patients who initiated dialysis in the main phase was 29 and 37% in the molidustat and darbepoetin groups, respectively.

Table 2.

Study drug-related AEs (safety population)

| DIALOGUE 3 | Molidustat (n = 118) | Darbepoetin (n = 42) | Total (n = 160) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number (%) of patients with >1 such AE | 8 (6.8) | 2 (4.8) | 10 (6.3) |

| Atrial tachycardia | 1 (0.8) | 0 | 1 (0.6) |

| Melena | 1 (0.8) | 0 | 1 (0.6) |

| Blood creatine phosphokinase increase | 1 (0.8) | 0 | 1 (0.6) |

| Blood pressure increase | 1 (0.8) | 0 | 1 (0.6) |

| Glycosylated hemoglobin increase | 1 (0.8) | 0 | 1 (0.6) |

| Hemoglobin increase (as judged by the investigator) | 1 (0.8) | 0 | 1 (0.6) |

| Metabolic disorder | 1 (0.8) | 0 | 1 (0.6) |

| Intestinal adenocarcinoma | 1 (0.8) | 0 | 1 (0.6) |

| Iron-deficiency anemia | 0 | 1 (2.4) | 1 (0.6) |

| Vascular disorder | 0 | 1 (2.4) | 1 (0.6) |

| DIALOGUE 5 | Molidustat (n = 57) | Epoetin (n = 30) | Total (n = 87) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number (%) of patients with >1 such AE | 11 (19.3) | 4 (13.3) | 15 (17.2) |

| Hemoglobin increase (as judged by the investigator) | 3 (5.3) | 1 (3.3) | 4 (4.6) |

| Anemia | 1 (1.8) | 0 | 1 (1.1) |

| Nephrogenic anemia | 1 (1.8) | 0 | 1 (1.1) |

| Bundle branch block left | 1 (1.8) | 0 | 1 (1.1) |

| Diarrhea | 1 (1.8) | 1 (3.3) | 2 (2.3) |

| Abdominal tenderness | 1 (1.8) | 0 | 1 (1.1) |

| Arteriovenous graft thrombosis | 1 (1.8) | 0 | 1 (1.1) |

| Vascular access site thrombosis | 1 (1.8) | 0 | 1 (1.1) |

| Electrocardiogram QT prolonged | 1 (1.8) | 0 | 1 (1.1) |

| Lipase increase | 1 (1.8) | 0 | 1 (1.1) |

| Weight decrease | 1 (1.8) | 0 | 1 (1.1) |

| Balance disorder | 1 (1.8) | 0 | 1 (1.1) |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 1 (1.8) | 0 | 1 (1.1) |

| Dizziness | 1 (1.8) | 0 | 1 (1.1) |

| Dyspnea | 1 (1.8) | 0 | 1 (1.1) |

| Hypertension | 1 (1.8) | 1 (3.3) | 2 (2.3) |

| Blood pressure increase | 0 | 1 (3.3) | 1 (1.1) |

Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities version 19.1 was used for coding AEs. A patient with multiple AEs was counted a single time for that system organ class or preferred term. An AE was defined as an event that occurred between the first dose date (regardless of phase) and the end-of-treatment date +3 days in the extension study. Data shown are for the safety population. AE, adverse event.

In D5, the proportions of patients who reported at least one AE were 91% (52/57) in the molidustat group and 93% (28/30) in the epoetin group (online suppl. Table 6). AEs reported in at least 10% of patients in any group are summarized in online supplementary Table 7. AEs considered to be drug-related by the investigator were reported by 19% (11/57) and 13% (4/30) of patients in the molidustat and epoetin groups, respectively (Table 2). Most drug-related AEs were mild or moderate in severity. Serious AEs were experienced by 51% (29/57) of patients in the molidustat group and 37% (11/30) in the epoetin group. A larger proportion of patients withdrew from molidustat treatment (23% [13/57]) than from epoetin treatment (7% [2/30]). Among patients who discontinued, 2 (both in the molidustat arm) had AEs considered to be treatment-related (anemia and nephrogenic anemia).

Discussion/Conclusion

Molidustat is a novel HIF-PH inhibitor, with the potential to be an alternative therapeutic option to RhEPO and its analogs for the treatment of anemia in patients with CKD. To our knowledge, these DIALOGUE extension studies are the first to assess the long-term efficacy and safety of a HIF-PH inhibitor. In both patient groups, molidustat was as effective as darbepoetin and epoetin in maintaining Hb levels within target ranges for up to 36 months. Additionally, molidustat was well tolerated, with a similar incidence of AEs to those reported in the darbepoetin and epoetin groups.

The use of rhEPO and its analogs for the treatment of anemia due to CKD since the early 1990s has generally improved the patients' quality of life; however, it is thought that Hb levels above the recommended range and supraphysiologic plasma EPO levels are likely to contribute to side effects associated with rhEPO and its analogs, and a cautious approach to Hb target levels is needed when treating anemia with rhEPO and its analogs [14, 15]. In the parent studies, molidustat increased Hb levels in treatment-naïve patients and maintained Hb levels within a target range in patients previously treated with a rhEPO analog. In the present long-term extension studies, the efficacy of molidustat in maintaining blood Hb levels within the target range for up to 52 weeks was similar to that of darbepoetin and epoetin.

In both patient groups, similar proportions of the molidustat and comparator groups reported at least one AE during the study. In addition, the long-term safety profile of molidustat observed in both extension studies was consistent with the parent short-term studies, and the profiles of darbepoetin and epoetin were consistent with previously published data [16, 17, 18]. The incidences of serious AEs were similar in the molidustat and darbepoetin groups in D3, whereas, in D5, a higher proportion of patients reported at least one serious AE in the molidustat group than in the epoetin group. In both extension studies, the study drug was discontinued owing to AEs in a greater proportion of patients receiving molidustat than those receiving darbepoetin or epoetin. However, most AEs leading to discontinuation were not considered to be drug-related. In addition, it should be noted that investigators may have chosen to discontinue patients in the molidustat groups from an efficacy and safety perspective, because this was an open-label study, and patients treated with molidustat could switch to a standard of care rhEPO or its analogs, whereas patients on darbepoetin or epoetin were already receiving standard of care for renal anemia. Although in D3 the decrease in eGFR was numerically lower in the molidustat group than in the darbepoetin group, urinary albumin/creatinine ratio, cystatin C, and serum creatinine measurements (data not shown) did not display a similar trend, precluding any conclusions regarding the potential renoprotective effect of molidustat.

The development of novel strategies that elevate and maintain EPO levels within the normal physiological range rather than producing the supraphysiologic EPO levels associated with rhEPO and its analogs for the treatment of anemia in individuals with CKD may be beneficial. One such option is molidustat, which, by targeting a different molecular mechanism of action to the standards of care, offers a potential alternative to rhEPO and its analogs for the treatment of anemia associated with CKD. The present long-term extension studies showed promising efficacy and safety profiles for molidustat treatment and warrant further clinical trials.

A strength of these studies is the inclusion of 2 standard of care as active controls. However, the findings presented here should be interpreted in the context of several limitations. In both studies, the sample size was too small to enable detection of statistical differences between treatments, and efficacy results should be considered to be exploratory in nature. Furthermore, the sample sizes are too low to draw meaningful conclusions on the long-term safety of molidustat. In addition, the open-label design of these studies could have biased the outcomes. Finally, because the populations of both studies comprised patients who had completed earlier short-term studies, these extension study populations may have been enriched for participants who responded to and tolerated molidustat and comparator.

In conclusion, in the DIALOGUE extension studies, molidustat maintained mean Hb levels within the target range in the long term, and the effect of molidustat on mean Hb levels was similar to that of darbepoetin and epoetin. Furthermore, molidustat treatment for up to 36 months was well tolerated. Therefore, molidustat, a novel HIF-PH inhibitor, appears to be an effective alternative to rhEPO and its analogs in the long-term management of anemia associated with CKD.

Ethics Statement

All studies were conducted in compliance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and in accordance with Good Clinical Practice guidelines. The protocols were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board or Ethics Committee of each participating center. All patients provided written informed consent before study entry.

Disclosure Statement

T.A. has received consulting fees from Astellas, Bayer Yakuhin Ltd, Fuso Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd, GlaxoSmithKline, JT Pharmaceuticals, Kissei Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd, Kyowa Hakko Kirin, Nipro Corporation, and Ono Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd, and lecture fees from Bayer Yakuhin Ltd, Chugai Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd, Kyowa Hakko Kirin, Torii Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd, Ono Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd, and Kissei Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd. I.C.M. has received research funding for the DIALOGUE studies, honoraria for steering committee activities, and speaker fees from Bayer AG. He has also received research support and speaker's honoraria from Akebia Therapeutics, Astellas, FibroGen, and GlaxoSmithKline. J.S.B. served on the steering committees for the DIALOGUE studies and for an Amgen-sponsored darbepoetin clinical trial. T.B., T.K., and G.S. are employees of Bayer AG. M.T. and K.I. are employees of Bayer Yakuhin Ltd. Study concept and protocol as well as analyses were performed based on recommendations by the sponsor and the authors. Interpretations were made by the authors of the manuscript.

Funding Sources

These studies were funded by Bayer AG.

Author Contributions

I.C.M., T.A., J.S.B., T.B., G.S., and T.K. participated in the study concept and design. All the authors were involved in the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data. All the authors participated in preparing the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data

Acknowledgment

Eriko Ogura of Bayer Yakuhin reviewed the manuscript for scientific accuracy. Medical writing support was provided by Nicolas Bertheleme of Oxford PharmaGenesis, Oxford, UK, with funding from Bayer AG. Availability of the data underlying this publication will be determined according to Bayer's commitment to the EFPIA/PhRMA “Principles for responsible clinical trial data sharing”. This pertains to scope, timepoint, and process of data access. As such, Bayer commits to sharing upon request from qualified scientific and medical researchers patient-level clinical trial data, study-level clinical trial data, and protocols from clinical trials in patients for medicines and indications approved in the United States and European Union as necessary for conducting legitimate research. This applies to data on new medicines and indications that have been approved by the European Union and United States regulatory agencies on or after January 01, 2014.

Interested researchers can use www.clinicalstudydatarequest.com to request access to anonymized patient-level data and supporting documents from clinical studies to conduct further research that can help advance medical science or improve patient care. Information on the Bayer criteria for listing studies and other relevant information is provided in the Study sponsors section of the portal. Data access will be granted to anonymized patient-level data, protocols and clinical study reports after approval by an independent scientific review panel. Bayer is not involved in the decisions made by the independent review panel. Bayer will take all necessary measures to ensure that patient privacy is safeguarded.

References

- 1.Culleton BF, Manns BJ, Zhang J, Tonelli M, Klarenbach S, Hemmelgarn BR. Impact of anemia on hospitalization and mortality in older adults. Blood. 2006 May;107((10)):3841–3846. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-10-4308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.KDOQI; National Kidney Foundation KDOQI Clinical Practice Guidelines and Clinical Practice Recommendations for Anemia in Chronic Kidney Disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2006 May;47((5 Suppl 3)):S11–S145. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2006.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Portolés J, Gorriz JL, Rubio E, de Alvaro F, García F, Alvarez-Chivas V, et al. NADIR-3 Study Group. The development of anemia is associated to poor prognosis in NKF/KDOQI stage 3 chronic kidney disease. BMC Nephrol. 2013 Jan;14((1)):2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-14-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Babitt JL, Lin HY. Mechanisms of anemia in CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012 Oct;23((10)):1631–4. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2011111078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline for Anemia in Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney Int Suppl. 2012;2:279–335. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krapf R, Hulter HN. Arterial hypertension induced by erythropoietin and erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESA) Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009 Feb;4((2)):470–80. doi: 10.2215/CJN.05040908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robles NR. The safety of erythropoiesis-stimulating agents for the treatment of anemia resulting from chronic kidney disease. Clin Drug Investig. 2016 Jun;36((6)):421–31. doi: 10.1007/s40261-016-0378-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Solomon SD, Uno H, Lewis EF, Eckardt KU, Lin J, Burdmann EA, et al. Trial to Reduce Cardiovascular Events with Aranesp Therapy (TREAT) Investigators Erythropoietic response and outcomes in kidney disease and type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2010 Sep;363((12)):1146–55. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1005109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Szczech LA, Barnhart HX, Inrig JK, Reddan DN, Sapp S, Califf RM, et al. Secondary analysis of the CHOIR trial epoetin-alpha dose and achieved hemoglobin outcomes. Kidney Int. 2008 Sep;74((6)):791–8. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boettcher M, Lentini S, Kaiser A, Flamme I, Kubitza D, Wensing G. First-in-man study with BAY 85-3934 - a new oral selective HIF-PH inhibitor for the treatment of renal anemia. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24:347A. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flamme I, Oehme F, Ellinghaus P, Jeske M, Keldenich J, Thuss U., Mimicking hypoxia to treat anemia HIF-stabilizer BAY 85-3934 (Molidustat) stimulates erythropoietin production without hypertensive effects. PLoS One. 2014 Nov;9((11)):e111838. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0111838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Macdougall IC, Berns JS, Akizawa T, Fishbane S, Bernhardt T. DIALOGUE phase 2 program for BAY85-3934 a HIF-PH inhibitor with daily oral treatment in anemic patients suffering from CKD/ESRD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24:413A. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Macdougall IC, Akizawa T, Berns JS, Bernhardt T, Krueger T. Effects of Molidustat in the Treatment of Anemia in CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019 Jan 7;14((1)):28–39. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02510218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Del Vecchio L, Locatelli F. An overview on safety issues related to erythropoiesis-stimulating agents for the treatment of anaemia in patients with chronic kidney disease. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2016 Aug;15((8)):1021–30. doi: 10.1080/14740338.2016.1182494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCullough PA, Barnhart HX, Inrig JK, Reddan D, Sapp S, Patel UD, et al. Cardiovascular toxicity of epoetin-alfa in patients with chronic kidney disease. Am J Nephrol. 2013;37((6)):549–58. doi: 10.1159/000351175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Macdougall IC, Provenzano R, Sharma A, Spinowitz BS, Schmidt RJ, Pergola PE, et al. PEARL Study Groups Peginesatide for anemia in patients with chronic kidney disease not receiving dialysis. N Engl J Med. 2013 Jan;368((4)):320–32. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1203166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patel M, Thimons DG, Winston JL, Langholff W, McGowan T. An open-label controlled study of epoetin alfa for the treatment of anemia of chronic kidney disease in the long term care setting. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012 Mar;13((3)):244–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2010.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weir MR, Pergola PE, Agarwal R, Fink JC, Kopyt NP, Singh AK, et al. A comparison of the safety and efficacy of HX575 (Epoetin Alfa Proposed Biosimilar) with epoetin alfa in patients with end-stage renal disease. Am J Nephrol. 2017;46((5)):364–70. doi: 10.1159/000481736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary data