Abstract

Introduction

Injuries are a major cause of disability and lost productivity. The case for a national trauma registry has been recognized by the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care and at a policy level.

Background

The need was flagged in 1993 by the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons and the Australasian Trauma Society. In 2003, the Centre of National Research and Disability funded the Australian and New Zealand National Trauma Registry Consortium, which produced three consecutive annual reports. The bi‐national trauma minimum dataset was also developed during this time. Operations were suspended thereafter.

Method

In response to sustained lobbying the Australian Trauma Quality Improvement Program including the Australian Trauma Registry (ATR) commenced in 2012, with data collection from 26 major trauma centres. An inaugural report was released in late 2014.

Result

The Federal Government provided funding in December 2016 enabling the work of the ATR to continue. Data are currently being collected for cases that meet inclusion criteria with dates of injury in the 2017–2018 financial year. Since implementation, the number of submitted records has been increased from fewer than 7000 per year to over 8000 as completeness has improved. Four reports have been released and are available to stakeholders.

Conclusion

The commitment shown by the College, other organizations and individuals to the vision of a national trauma registry has been consistent since 1993. The ATR is now well placed to improve the care of injured people.

Keywords: trauma, registry

Introduction

Road trauma is a leading cause of death and injury in Australia.1, 2 However, all injuries are significant as a major cause of disability and lost productivity worldwide.3 Therefore, the case for a national trauma clinical quality registry (CQR) to monitor, evaluate and inform change in trauma care is strong.4, 5 This year the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons (RACS) celebrates 25 years of supporting the development of the Australian Trauma Registry (ATR).

Over the last decade, the importance of CQRs as drivers of quality improvement and public health programmes has been promoted by the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (ACSQH) and recognized by both the Federal and state governments. Initiatives included the endorsement in 2010 by health ministers of strategic principles for registries that led to the publication of the Framework for Australian clinical quality registries in 2014.6 Gabbe et al.7 showed that at a state level, since the introduction of a trauma system that includes a registry, cost savings can be made of over $600 000 per admission. Furthermore, in 2016, the cost–benefit ratio of CQRs was evaluated by the ACSQH as being as much as seven to one, with the minimum cost–benefit ratio expected to be four to one if the registry was national.8 In the same year, a report on critical incident management in Victorian hospitals recognized the role that CQRs have in performance monitoring and recommended that their funding be adjusted accordingly.9

In addition, the ACSQH published a report that raised trauma to the second highest priority, behind the clinical domain of ischaemic heart disease and musculoskeletal disorders. The attendant summary stated the associated ‘serious consequences of poor quality (trauma) care, very high burden of disease and high cost to the system’.10

The trauma registry development activity in Australia has aligned with the World Health Organization Decade of Action for Road Safety 2011–202011 and the National Road Safety Strategy's goal of reducing road trauma by at least 30% by 2020.

Background

The need for a national trauma registry in Australia was initially flagged in 1993 by the National Road Trauma Advisory Council in conjunction with support from the RACS and the Australasian Trauma Society (ATS).12 This early advocacy, in combination with financial support from the Centre of National Research on Disability and Rehabilitation Medicine, formed the basis for the formation a decade later of the Australian and New Zealand National Trauma Registry Consortium (NTRC), led by Professor Cliff Pollard, FRACS. Cliff Pollard's commitment spanned the next 25 years and was supported from a paediatric care viewpoint by Professor Danny Cass, FRACS. The Centre of National Research on Disability and Rehabilitation Medicine provided the majority of funding to the consortium from its inception in 2003 and was supported in 2005 by the New South Wales Institute of Trauma Injury Management. Additional financial assistance was provided by the ATS and RACS, with Mr Ian Civil, FRACS, and Dr Tony Joseph, FACEM, coordinating the support of the ATS. The championship of these bodies, and cooperation with existing registries in Australian and New Zealand, enabled the NTRC to collate the available data and produce annual reports in 2003, 2004 and 2005.13, 14

The NTRC was committed to the task of standardizing trauma data collection to enable benchmarking and deploying a trauma minimum dataset (MDS) that would serve both Australia and New Zealand. Mr Cameron Palmer drove this work, which began in 2005, and was completed in 2010 with the development of a dictionary comprising 67 data elements.15 The dataset is now known as the Bi‐National Trauma Minimum Dataset (BNTMDS).

The NTRC ceased operations while the development of the BNTMDS was in progress; however, the decades of support and commitment shown to the concept of a national trauma registry, and the eventual availability of an agreed MDS, laid a firm foundation for the next phase of development – the Australian Trauma Quality Improvement Program and the ATR (AusTQIP‐ATR).

Method

In 2011, in response to the sustained vision and lobbying of the RACS, both Alfred Health in Melbourne and the National Critical Care and Trauma Response Centre in Darwin provided funding that would enable the NTRC's work to continue. Professor Russell Gruen, FRACS, directing the National Trauma Research Institute, undertook the challenge and created the AusTQIP, a national collaboration framework with objectives that would support health services to provide the best trauma care and chance of recovery to injured Australians (Table 1). Professor Kate Curtis, RN, added her extensive trauma nursing experience to co‐chair the programme.

Table 1.

AusTQIP objectives

| 1. Standardize and align trauma data definitions for designated major trauma centres and established state‐based trauma registries. |

| 2. Develop technical infrastructure and best‐practice governance policies for a national clinical quality registry for trauma (ATR). |

| 3. Combine subset of trauma data already routinely collected by designated Major Trauma Centres and established state‐based trauma registries into an ATR. |

| 4. Develop secure systems to support standardized and customized reports on trauma data, including de‐identified, risk‐adjusted comparison of data among designated major trauma centres. |

| 5. Furthermore, develop existing trauma quality improvement systems to facilitate us of ATR data to improve safety, quality and patient outcomes at designated Major Trauma Centres. |

| 6. Foster effective networks between key stakeholders with a significant interest in trauma quality improvement. |

| 7. Monitor structure, process and outcome measures and the impact of collaborative quality improvement on trauma patient outcomes. |

ATR, Australian Trauma Registry; AusTQIP, Australian Trauma Quality Improvement Program.

The AusTQIP including the ATR began operations in 2012 with representation from stakeholders in all states and territories. A large information gathering exercise was undertaken by then team members, Mr Nathan Farrow and Dr Meng Tuk Mok, that determined the status of quality improvement and data collection capacity at all of the major trauma centres (MTCs) around the country at that time.

Using the completed BNTMDS and the information gaps identified in consultation with the major trauma centres, the study protocol was finalized in June 2012. The resulting Collaboration Agreement was formalized in May 2014 with executive endorsement from the organizations that would contribute data to the ATR. Once all ethics and governance approvals were in place, data were collected from the contributing sites for cases that met inclusion criteria (Table 2) with dates of injury between 1 January 2010 and 31 December 2012 inclusive.

Table 2.

ATR inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusions |

OR

|

| Exclusions |

|

AIS, Abbreviated Injury Score; ATR, Australian Trauma Registry; ISS, injury severity score.

The now consolidated national trauma registry data were published in 2014 with the release of the first AusTQIP‐ATR report, entitled Caring for the Severely Injured in Australia: Inaugural Report of the Australian Trauma Registry 2010 to 2012.

In late 2015, the present Director of the National Trauma Research Institute and past president of the ATS, Professor Mark Fitzgerald, FACEM, supported by funding from the Alfred Foundation, arranged a collaboration with the Department of Epidemiology and Preventive Medicine at Monash University led by Professor Peter Cameron, FACEM. Ms Jane Ford was appointed as a dedicated data manager in January 2016.

All previous ethics and governance approvals at the sites were updated along with data submission protocols. Data collection resumed in June 2016 of cases that met ATR inclusion criteria with dates of injury from 1 January 2013. The Steering Committee decided to move to reporting in financial years, thus the first ensuing report released in June 2017 was for cases with dates of injury up to and including the 30 June 2015.16

The future of the ATR was confirmed in May 2016, when the Rural and Regional Affairs and Transport References Committee met at the Senate enquiry into aspects of road safety in Australia. After presentations by Mr John Crozier, FRACS, and Ms Ailene Fitzgerald, FRACS, the first recommendation of the resultant report was that the Commonwealth Government commit to funding the operations of the ATR.17

In response to the recommendation, and in the context of the ongoing support from the RACS and the National Road Safety Strategy, the Australian Prime Minister, the Honourable Malcolm Turnbull, announced new funding for the ATR. The funding was provided in December 2016 jointly by the Bureau of Infrastructure, Transport and Regional Economics and the Department of Health.

Results

The ATR has progressed to data collection of cases with dates of injury in the 2017–2018 financial year. Quality and completeness reports are provided to the contributing sites on a regular basis to optimize data integrity. Including the inaugural report, four consolidated reports have been released (AusTQIP‐ATR – National Trauma Research Institute).

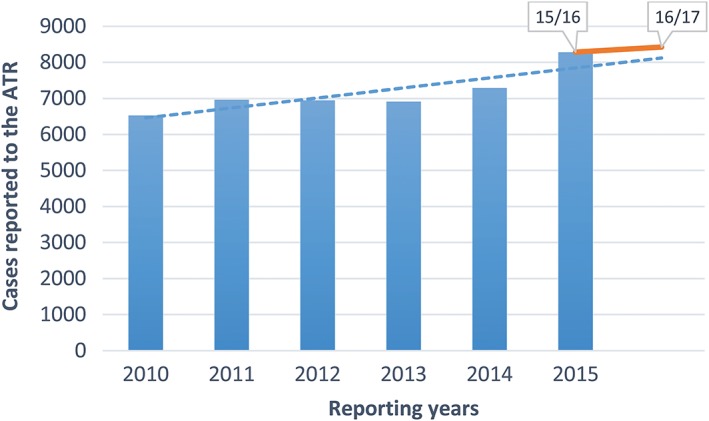

Aggregate numbers indicate an increase in the number of cases reported to the ATR (Fig. 1). This is most likely due to improved data completeness, although a small increase would be expected due to changes in incidence of certain injuries and the ageing of the general population.18

Figure 1.

Trend of increase in the number of cases reported by the Australian Trauma Registry (ATR), adjusted to show change of methodology from calendar years to financial years.

Discussion

The ATR will continue to improve the extent of data completeness and coverage and it is envisaged that the data will be increasingly used for monitoring the effect of public health initiatives, including safety campaigns that address road trauma (https://www.towardszero.vic.gov.au) and community concerns such as the growing incidence of ladder related falls in males aged over 65 years.19 Risk‐adjusted modelling will enable benchmarking between jurisdictions of clinical processes and outcomes that will inform improvements in trauma care.20 There is a wide variability between sites for many measures, for example, time to theatre and splenectomy rates for splenic injury.

Other developments are also planned (Table 3), some of which require better use of available information technology, while others will be a manual process requiring discussion and consultation. The list will evolve as tasks are completed and the goals are achieved.

Table 3.

Pending ATR initiatives

| 1. Addition of contributing sites |

|

| 2. Inclusion of New Zealand data from the New Zealand Major Trauma Registry (NZMTR) |

|

| 3. Review of the BNTMDS |

|

| 4. Development of a targeted MDS to capture presentations to Emergency Departments (EDs) as a result of road trauma |

|

| 5. Update of AusTQIP‐ATR internet profile |

|

| 6. Development of a risk‐adjustment model for benchmarking of process indicators. |

|

| 7. Improved access to, and use of, ATR data |

|

ATR, Australian Trauma Registry; AusTQIP, Australian Trauma Quality Improvement Program; BNTMDS, Bi‐National Trauma Minimum Dataset; EDs, emergency departments; GPS, global positioning system; MoU, memorandum of understanding; MTCs, major trauma centres; NTRI, National Trauma Research Institute; NZMTR, New Zealand Major Trauma Registry; RACS, Royal Australasian College of Surgeons; TQIP, total quality improvement.

Conclusion

The College positions on road trauma prevention and trauma prevention have been developed and continually updated since the original Road Trauma Committee was formed in 1970. The vision for a national trauma registry in Australia has been championed by committed individuals and organizations since 1993. Establishing the ATR has been a long and careful process, eventually receiving federal government funding in December 2016. A systems‐based approach to trauma care, based on accurate and credible data for clinicians, injury control experts, policy makers and legislators is essential to reduce the consequences of injury. The ATR is now well placed to improve the quality of care of severely injured people and is a proud achievement of the College.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the following people and organizations for their expert guidance: The AusTQIP‐ATR Steering Committee: Ms Bronte Martin; Mr Chris Clarke; Dr David Read; Dr Grant Christey; Ms Kathleen McDermott; Professor Michael Reade; Mr Nick Rushworth; Professor Rodney Judson; Dr Sandy Zalstein; Associate Professor Kirsten Vallmuur; Dr Sudhakar Rao; Dr Tony Joseph; Dr Joseph Mathew; Dr Michael Dinh; Dr Ian Civil. The AusTQIP‐ATR Management Committee: Professor Belinda Gabbe; Professor James Harrison; Professor Kate Curtis; Ms Mimi Morgan; Ms Sue McLellan. The New Zealand Major Trauma Registry: Dr Ian Civil, National Clinical Lead and Ms Siobhan Isles, Programme Manager. Registry and data managers at the collaborating sites. The ATR Manager, Ms Emily McKie, for the provision of current data.

M. C. Fitzgerald MBBS, MD; K. Curtis RN, PhD; P. A. Cameron MBBS, MD; J. E. Ford BSc (HIM), CAISS; T. S. Howard PhD; J. A. Crozier FRCST (Hons), DOU (Vasc); A. Fitzgerald MBBS; R. L. Gruen MBBS, PhD; C. Pollard AM, BD, MBBS.

References

- 1. Australian Transport Council . National road safety strategy 2011–2020. 2011. Canberra: Council of Australian Governments. [Cited 23 Jul 2018.] Available from URL: http://roadsafety.gov.au/nrss/

- 2. Australian Automobile Association . Benchmarking the performance of the National Road Safety Strategy. 2017. [Cited 23 Jul 2018.] Available from URL: https://www.aaa.asn.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/AAA-Benchmarking-Report_Q4-2017.pdf

- 3. Haagsma JA, Graetz N, Bolliger I et al The global burden of injury; incidence, mortality, disability‐adjusted life years and time trends from the Global Burden of Disease study 2013. Inj. Prev. 2016; 22: 3–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Moore L, Clark DE. The value of trauma registries. Injury 2008; 39: 686–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zehtabchi S, Nishjima DK, McKay MP, Clay N. Trauma registries: history, logistics, limitations, and contributions to emergency medicine research. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2011; 18: 637–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care . Framework for Australian clinical quality registries. 2014. [Cited 30 Jul 2018.] Available from URL: https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/wp‐content/uploads/2014/09/Framework‐for‐Australian‐Clinical‐Quality‐Registries.pdf

- 7. Gabbe BJ, Lyons RA, Fitzgerald MC, Judson R, Richardson J, Cameron PA. Reduced population burden of road transport‐related major trauma after introduction of an inclusive trauma system. Ann. Surg. 2015; 261: 565–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care . Economic evaluation of clinical quality registries: final report. 2016. [Cited 30 Jul 2018.] Available from URL: https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/wp‐content/uploads/2016/12/Economic‐evaluation‐of‐clinical‐quality‐registries‐Final‐report‐Nov‐2016.pdf

- 9. Duckett S, Cuddihy M, Newnham H. Targeting zero. Supporting the Victorian hospital system to eliminate avoidable harm and strengthen quality of care. Report of the review of hospital safety and quality assurance in Victoria. 2016. [Cited 30 Jul 2018.] Available from URL: https://www.dhhs.vic.gov.au/publications/targeting‐zero‐review‐hospital‐safety‐and‐quality‐assurance‐victoria

- 10. Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care . Prioritised list of clinical domains for clinical quality registry development: final report. 2016. [Cited 30 Jul 2018.] Available from URL: https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/wp‐content/uploads/2016/12/Prioritised‐list‐of‐clinical‐domains‐for‐clinical‐quality‐registry‐development‐Final‐report‐Nov‐2016.pdf

- 11. United Nations Road Safety Collaboration . Decade of Action for Road Safety 2011‐2020 seeks to save millions of lives. [Cited 30 Jul 2018.] Available from URL: http://www.who.int/roadsafety/decade_of_action/en/

- 12. Alfred Health . Caring for the severely injured in Australia: inaugural report of the Australian Trauma Registry 2010 to 2012. 2014. [Cited 30 Jul 2018.] Available from URL: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/569ce2937086d768fdf7aeac/t/57a2e822be6594bf8c874a45/1470294067718/aust‐trauma‐registry‐inaugural‐report.pdf

- 13. Davey TM, Pollard CW, Aitken LM et al Tackling the burden of injury in Australasia: developing a binational trauma registry. Med J Aust. 2006; 185: 512–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pollard CW. Re Australian clinical quality registries. Correspondence from NTRC to ACSQHC. 2006. [Cited 23 Jul 2018.] Available from URL: https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/wp‐content/uploads/2012/02/10_National‐Trauma‐Registry‐Consortium‐Royal‐Australasian‐College‐of‐Surgeons‐30‐Jun‐08‐7‐pages‐PDF‐112‐KB.pdf

- 15. Palmer CS, Davey TM, Mok MT et al Standardising trauma monitoring: the development of a minimum dataset for trauma registries in Australia and New Zealand. Injury 2013; 44: 834–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Australian Trauma Quality Improvement Program . Australian trauma registry consolidated report. 1/1/2013–30/6/2015. 2017. National Trauma Research Institute. [Cited 30 Jul 2018.] Available from URL: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/569ce2937086d768fdf7aeac/t/59585ccf4c8b03b8a582b1f2/1498963171223/Australian+Trauma+Quality+Improvement+Program+including+the+Australian+Trauma+Registry+%28AusTQIP‐ATR%29+Report+January+2013+‐+June+2015.pdf

- 17. Senate Standing Committee on Rural and Regional Affairs and Transport . Aspects of road safety in Australia. Commonwealth of Australia. 2017. Available from: https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Senate/Rural_and_Regional_Affairs_and_Transport/RoadSafety45/Report

- 18. Department of Health and Human Services . Victorian state trauma system and registry report. 1 July 2015–30 June 2016. State of Victoria. 2017. [Cited 25 Jul 2018.] Available from URL: https://www2.health.vic.gov.au/about/publications/annualreports/Victorian‐State‐Trauma‐Registry‐Summary‐Report‐‐‐1‐July‐2015‐to‐30‐June‐2016

- 19. Ackland HM, Pilcher DV, Roodenburg OS, McLellan SA, Cameron PA, Cooper DJ. Danger at every rung: epidemiology and outcomes of ICU‐admitted ladder‐related trauma. Injury 2016; 47: 1109–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gruen RL, Gabbe BJ, Stelfox HT, Cameron PA. Indicators of the quality of trauma care and the performance of trauma systems. Br. J. Surg. 2012; 99: 97–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]