Abstract

Although alternations of brain functional networks (BFNs) derived from resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (rs-fMRI) have been considered as promising biomarkers for early Alzheimer’s disease (AD) diagnosis, it is still challenging to perform individualized diagnosis, especially at the very early stage of preclinical stage of AD, i.e., early mild cognitive impairment (eMCI). Recently, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) show powerful ability in computer vision and image analysis applications, but there is still a gap for directly applying CNNs to rs-fMRI-based disease diagnosis. In this paper, we propose a novel multiple-BFN-based 3D CNN framework that can automatically and deeply learn complex, high-level, hierarchical diagnostic features from various independent component analysis-derived BFNs. More importantly, the embedded features of different BFNs could comprehensively support each other towards a more accurate eMCI diagnosis in a unified model. The performance of the proposed method is validated by a large-sample, multisite, rigorously controlled publicly accessible dataset. The proposed framework can also be conveniently and straightforwardly applied to individualized diagnosis of various neurological and psychiatric diseases.

Keywords: Diagnosis, Convolutional neural networks, Brain networks Independent component analysis, Mild cognitive impairment, Deep learning Resting-state functional MRI

1. Introduction

Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) is the most common form of dementia with memory and cognitive deficits in elderly people and is to date still irreversible and incurable [1]. Early detection of AD at its preclinical Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) stage is of great clinical importance for early intervention. Recently, a few pioneering studies have called for pushing early AD diagnosis to an even earlier stage, i.e., early MCI (eMCI). While promising results based on group-level comparisons were found [2–4]; computer-aided individualized eMCI diagnosis is still among the most challenging tasks. Many MCI studies have used resting-state functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (rs-fMRI)-derived brain functional networks (BFNs) for MCI studies [5, 6]; however, most of them are based on mass-univariate analysis, e.g., constructing the default mode network (DMN) and conducting a voxel-wise greedy search for potential group differences within it [5]. While such traditional BFN-based MCI studies yield some statistically significant brain regions [2–4], they suffer several inherent drawbacks: (1) mass-univariate analysis usually results in loss of statistical power; (2) the voxel-wise analysis may lose rich inter-voxel pattern information in the BFNs; and (3) the severe noise in the rs-fMRI data could overwhelm subtle diagnostic information in eMCI. For example, a study in MCI detected multiple BFNs but only found a small blob in the DMN with statistical differences between MCI and controls [3], which is insufficient to clearly separating the two groups.

MCI could involve complex brain structural and functional changes, which usually involve large-scale functional abnormalities that could encompass multiple BFNs, with both local and global changes, as well as with both intra- and inter-BFN association changes. This inspired us to use the modern convolutional neural network (CNN) framework to improve individual diagnosis performance for eMCI because CNNs have been demonstrated to be powerful in automatic learning and capturing hierarchical features by integrating different scales of features with different layers for spatial pattern representation and recognition in computer vision and image analysis applications [7]. Previous works have also demonstrated a promising future of CNN for medical imaging analysis such as disease diagnosis and prognosis [8, 9]. However, directly applying CNNs to rs-fMRI data for disease diagnosis is not straightforward; several key issues need to be solved: (1) As aforementioned, the raw rs-fMRI data is usually noisy; and, more importantly, (2) raw rs-fMRI data is a 4D data with a temporal dimension that does not have correspondence across different subjects, whereas CNN cannot be directly applied to such time-series data. Several studies have proposed a fully connected network to learn patterns of the whole-brain functional connectivity (FC) matrices by treating it as a long FC-feature vector constituting inter-regional rs-fMRI signal correlations [10, 11]. However, they are actually learning an oversimplified BFN without taking voxel-wise-FC details into consideration.

Inspired by independent component analysis (ICA), a widely used data-driven BFN modeling method [12, 13], we propose a novel BFN-based deep learning framework that directly works on the BFNs abstracted by ICA, thus avoiding the technical limitation of directly applying CNN on the noisy raw rs-fMRI time series. Specifically, we use a group-wise ICA algorithm [14] to obtain a set of spatially independent BFNs for each individual, each of which is regarded as a voxel-wise spatial representation of a certain brain functional system mediating specific cognitive function(s) [15]. Instead of directly conducting separate traditional voxel-wise mass-univariate comparisons for each BFN (where only superficial features could be used), we train multiple 3D CNNs, each of which learns complex, hierarchical spatial pattern information from a BFN in a layer-by-layer manner; and these CNNs for multiple BFNs are further combined with consequential layers for end-to-end multiple-BFN-based eMCI diagnosis. The innovation of our method is three-fold. (1) It learns diagnostic spatial patterns of each BFN automatically and deeply, with consideration of both local and global FC features; (2) It takes advantage of different BFNs by letting them support each other toward more accurate disease diagnosis; and (3) It uses widely accepted ICA-derived BFNs and makes the result interpretation relatively intuitive. We demonstrate the feasibility of our method in a challenging eMCI diagnosis problem using a rigorously collected, publicly accessible, multisite Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative 2 (ADNI2)1 dataset.

2. Materials and Preprocessing

We collected raw rs-fMRI data from 49 eMCI subjects (20M/29F, mean age 72.12 ± 7.22 yrs.) and 48 age-, gender-matched Normal Controls (NCs) (20M/28F, mean age 75.50 ± 46.81 yrs.) from the ADNI2 database. The eMCI is the early stage of MCI, whose BFNs are believed to more resemble to the NCs’; thus their classification is more challenging than MCI vs. NC classification. Note that, multiple rs-fMRI scans were longitudinally acquired for most of the subjects. We thus used all the available data as long as they corresponded to stable eMCI or NC status. This allowed us to make use of as much data as possible for more accurate CNN model training. Thus, we used a total of 351 samples (172 and 179 for NCs and eMCIs, respectively), which makes it among one of the largest sample-size studies to date. The data are acquired by 3T Siemens scanners at multiple sites with rigorous quality control (TR = 3,000 ms, TE = 30 ms, voxel size = 3 × 3 × 3.3 mm3, the number of slices = 48, and flip angle = 80°).

We preprocessed the data using a widely-adopted DPARSF toolbox2 with conventional pipeline as used in [14]. During the preprocessing, the first volumes acquired during the first 10 s. were discarded to ensure magnetization equilibrium and the remaining volumes were head motion corrected, spatially normalized, spatially resampled (voxel resolution = 3 × 3 × 3 mm3), smoothed and band-pass filtered. Nuisance signals including the head motion parameters, mean white matter and cerebrospinal fluid signals are regressed out to further remove noise and artifacts.

3. Proposed Method

We propose a novel framework combining Group-Information-Guided ICA (GIG-ICA) [14] and 3D CNNs for BFN-based eMCI diagnosis. GIG-ICA drives subject-specific BFNs by keeping spatial correspondence across subjects under the guidance of the group-level BFN information [14]. Thus, we chose GIG-ICA to generate more robust BFNs for better model training. Of note, other rs-fMRI denoising methods can also be used such as FIX in FSL3; while other whole-brain BFN construction methods (e.g., seed-based correlation) can also be as long as robust and reliable BFNs can be extracted [15, 16]. GIG-ICA, as a group-wise ICA method, decomposed 4D rs-fMRI data from all subjects into a set of 3D spatial maps of BFNs for each subject, with which we can construct 3D CNNs to learn sophisticated embedded spatial patterns of BFNs.

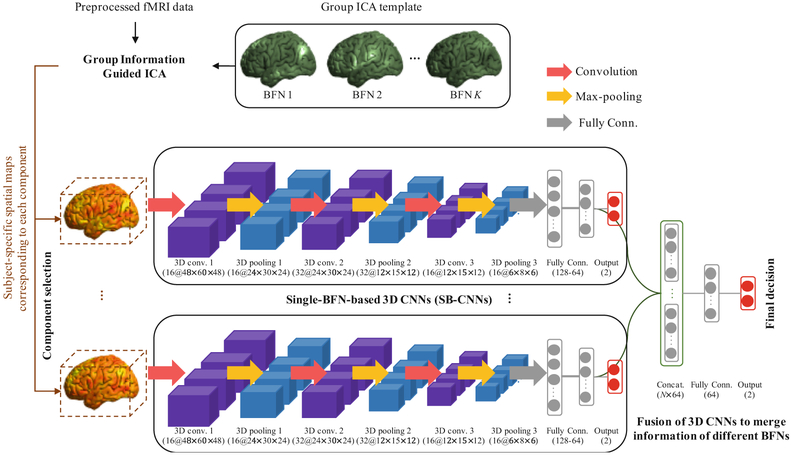

Figure 1 illustrates the overall framework of our method. Specifically, from preprocessed rs-fMRI, we first extract 3D subject-specific spatial map of each of the 6 high-level cognitive function-related BFNs that could be affected in eMCIs. For each 3D BFN, we first learn single-BFN-based 3D CNN (SB-CNN), then fuse the multiple SB-CNNs with a multiple-BFN-based 3D CNN (MB-CNN) to make the final decision by merging all the available high-level features from each SB-CNN as a unified framework.

Fig. 1.

Illustration of the proposed multiple-BFN-based 3D CNN (MB-CNN) framework for early MCI (eMCI) diagnosis. MB-CNN consists of multiple single-BFN-based 3D CNN (SB-CNN) by fusing high-level features of each SB-CNN in a unified framework. Each layer consists of multiple feature maps with (# feature maps@x×y×z dimension).

3.1. Extraction of Subject-Specific Spatial Maps of BFNs

To extract subject-specific BFNs for inputs of the CNNs, we apply GIG-ICA to the preprocessed rs-fMRI of all subjects. As described above, GIG-ICA uses group information captured by the standard group ICA as a guidance to extract subject-specific BFNs with individually unique BFN information preserved and with inter-subject correspondence ensured. In this work, as the spatial guidance of GIG-ICA, we use the group ICA templates provided by Human Connectome Project (HCP)4 that consist of 25 components by conducting a standard group ICA with 812 normal subjects.

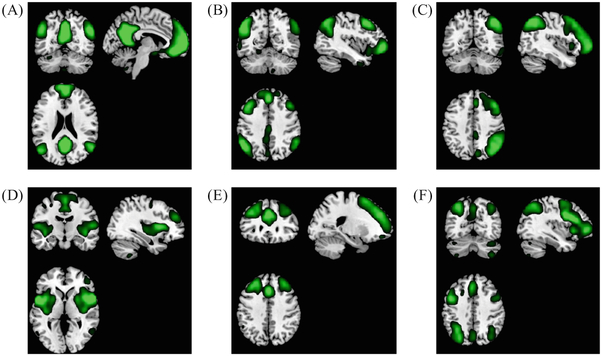

As the AD pathological attacks in the early stage mainly target on the high-level cognitive function-related BFNs, e.g., the DMN, frontoparietal networks, attention networks, and executive control network; thus, we manually select 6 components which are associated with the higher-level cognitive functions. Figure 2 shows the selected BFNs. We use the GIG-ICA-derived, subject-specific BFN maps of the 6 components for SB-CNN and MB-CNN training.

Fig. 2.

The maps of the selected group-level components of the high-level cognitive function-related BFNs: (A) default model network (DMN), (B, C) frontoparietal networks (FPNs 1&2), (D, E) attention networks (ANs 1&2), and (F) executive control network (ECN), from the group ICA template provided by Human Connectome Project (HCP). We set a threshold of 5 in each map for the visualization purpose.

3.2. Learning of Spatial Features of BFNs

We first construct SB-CNN for each BFN, respectively, and then merge those separately trained SB-CNNs as a unified, MB-CNN-based disease diagnosis model (refer to Fig. 1 for more details).

SB-CNN Construction and Learning.

The subject-specific spatial maps of each BFN are fed to each SB-CNN, respectively, as input. To reduce computational complexity, from each spatial map of 61 × 73 × 61 dimension, we remove the background voxels by cropping the 3D BFN map to only include brain regions of 48 × 60 × 48 dimension. In each SB-CNN, the input is convolved by a series of three convolutional layers with Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) activation, and each convolutional layer is followed by a max-pooling layer to down-sample the feature maps generated from the previous convolutional layers. The sizes of convolution and max-pooling kernels are set to 3 × 3 × 3 and 2 × 2 × 2, respectively. The last feature maps are fully connected with a series of 2 fully connected layers with 128 and 64 nodes, and an output layer has 2 nodes for binary class labels. The label information is used for back-propagation procedure in model learning. The softmax function is applied to the output units to predict the probability of an input belonging to NC or eMCI group. The model is optimized by the Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) algorithm [17].

MB-CNN Construction and Learning.

The last fully connected layers of each SB-CNN are concatenated, and then an additional fully connected layer with 64 nodes are stacked to merge the high-level features of each SB-CNN together and make them support each other toward better eMCI classification. An output layer with the softmax function is connected to the top of the model for the final decision making. The learned weights of each SB-CNN are adopted as the initial weights of MB-CNN, and then all the weights are refined together during MB-CNN learning by the SGD algorithm to make the model robust and also make different BFNs affect to each other in a layer-by-layer way.

4. Experiments and Results

4.1. Experimental Settings

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed MB-CNN method, we compare it with a baseline model, for which we used a traditional voxel-wise mass-univariate analysis to extract features and then fed them in a Support Vector Machine (SVM). For the baseline method, discriminative features from each BFN are extracted by using voxel-wise two-sample t-tests on the training set, and then Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is applied to reduce dimension of the features5. We also compare the MB-CNN with different SB-CNNs, each of which diagnose eMCI based only on each of the 6 BFNs. For evaluation of the proposed and competing methods, 5-fold cross-validation is adopted. That is, all the subjects are partitioned into 5 subsets, and 4 are used for training and the remaining subset is used for testing. Of note, some subjects have multiple scans in data acquisition (see Sect. 2). For training, all the scans of the subjects included in the training stage are used for better training; but, for the testing subjects, only the baseline scan of each subject are used for producing the testing result, to resemble the real application scenario.

4.2. Performance Evaluation

For performance evaluation, diagnostic performance is computed by the following quantitative metrics:

Accuracy (ACC) = (TP + TN)/(TP + TN + FP + FN)

Sensitivity (SEN) = TP/(TP + FN)

Specificity (SPEC) = TN/(TN + FP)

Positive Predictive Value (PPV) = TP/(TP + FP)

Negative Predictive Value (NPV) = TN/(TN + FN)

where TP, TN, FP, and FN denote true positive, true negative, false positive, and false negative, respectively.

In Table 1, we summarize the performance of the proposed and competing methods for eMCI diagnosis. The proposed method shows the best performance for all the performance metrics. Specifically, the proposed MB-CNN shows the best accuracy of 74.23% which significantly improves the performance of the baseline method by more than 9%. Compared to different SB-CNNs only using a single BFN, the proposed method improves the accuracy by ~3–7%. According to the results, the proposed framework shows the effectiveness on extracting spatial features from different BFNs and merging the multiple-BFN features together for more accurate eMCI diagnosis. We also find that the SB-CNNs with DMN and FPN achieved better diagnosis accuracy than those with other BFNs, indicating that these two brain functional systems could be more affected in the early stage of MCI. We also noted that, even using all the 6 BFNs, the traditional method (Baseline) could not compete with any of the CNN-based methods, indicating a promising future of using CNN for disease diagnosis.

Table 1.

Performance comparison of the proposed and competing methods.

| Method | BFN | ACC (%) | SEN (%) | SPEC (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | All | 64.95 | 69.39 | 60.42 | 64.15 | 65.91 |

| SB-CNN | DMN | 70.10 | 71.43 | 68.75 | 70.00 | 70.21 |

| FPN1 | 71.13 | 73.47 | 68.75 | 70.59 | 71.74 | |

| FPN2 | 70.10 | 73.47 | 66.67 | 69.23 | 71.11 | |

| AN1 | 68.04 | 71.43 | 64.58 | 67.31 | 68.89 | |

| AN2 | 67.01 | 69.39 | 64.58 | 66.67 | 67.39 | |

| ECN | 67.01 | 67.35 | 66.67 | 67.35 | 66.67 | |

| MB-CNN | All | 74.23 | 75.51 | 72.92 | 74.00 | 74.47 |

SB-CNNs are constructed for each BFN, respectively; the baseline and MB-CNN methods use all the six BFNs (DMN: default-mode network; FPN 1&2: two fronto-parietal networks; AN 1&2: two attention networks; ECN: executive control network).

5. Discussion and Conclusions

We proposed a novel framework to model spatial patterns of BFNs derived from rs-fMRI by combining GIG-ICA and 3D CNNs in a unified framework for accurate eMCI diagnosis. To our best knowledge, this is the first BFN-based deep learning for the disease diagnosis. Zhao et al., proposed a 3D CNN model for automatic ICA component labeling for each BFN [18]; however, that study used only healthy subjects for a much easier task (component labeling) than the current eMCI diagnosis study. In the proposed method, we first extracted subject-specific spatial maps of high-level cognitive function-related BFNs by using GIG-ICA, and then constructed a 3D CNN for each BFN, respectively, to learn deeply embedded spatial patterns of each BFN. Furthermore, we combined all the CNNs to fuse the deep features of multiple BFNs in a unified framework for joint eMCI diagnosis. Results on a public dataset show the effectiveness of the proposed framework for eMCI diagnosis. In future, we will focus on the time-varying spatial patterns of the BFNs, as the dynamic brain functional connectome could contain more fine-grained information for eMCI diagnosis. The proposed method can also be used for diagnosis of other diseases in the future.

Acknowledgements.

This work was partially supported by NIH grants (AG041721, AG049371, AG042599, and AG053867).

Footnotes

To optimize the SVM hyperparameter, a nested 10-fold cross-validation technique is adopted for the inner cross-validation loop, while the outer loop is 5-fold cross-validation.

References

- 1.Alzheimer’s Association: Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s Dement. 13, 325–373 (2017) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Celone KA, Calhoun VD, Dickerson BC, et al. : Alterations in memory networks in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease: an independent component analysis. J. Neurosci. 4, 10222–10231 (2006) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Binnewijzend MA, Schoonheim MM, Sanz-Arigita E, et al. : Resting-state fMRI changes in Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. Neurobiol. Aging 33(9), 2018–2028 (2012) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Petrella JR, Sheldon FC, Prince SE, et al. : Default mode network connectivity in stable vs. progressive mild cognitive impairment. Neurology 76(6), 511–517 (2011) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keiichi O, Nobuhiro Y, Kentaro O, et al. : Can a resting-state functional connectivity index identify patients with Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment across multiple sites? Brain Connect. 7(7), 391–400 (2017) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhao Q, Lu H, Metmer H, et al. : Evaluating functional connectivity of executive control network and frontoparietal network in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Res. 1678, 262–272 (2018) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.LeCun Y, Bengio Y, Hinton G: Deep learning. Nature 521(7553), 436–444 (2015) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nie D, Zhang H, Adeli E, Liu L, Shen D: 3D deep learning for multi-modal imaging-guided survival time prediction of brain tumor patients In: Ourselin S, Joskowicz L, Sabuncu MR, Unal G, Wells W (eds.) MICCAI 2016. LNCS, vol. 9901, pp. 212–220. Springer, Cham; (2016). 10.1007/978-3-319-46723-8_25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gao M, Bagci U, Lu L, et al. : Holistic classification of CT attenuation patterns for interstitial lung diseases via deep convolutional neural networks. Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomed. Eng.: Imaging Vis. 6(1), 1–6 (2018) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hjelm RD, Calhoun VD, et al. : Restricted Boltzmann machines for neuroimaging: an application in identifying intrinsic networks. NeuroImage 96, 245–260 (2014) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kam T-E, Suk H-I, Lee S-W: Multiple functional networks modeling for autism spectrum disorder diagnosis. Hum. Brain Mapp. 38(11), 5804–5821 (2017) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beckmann CF, Deluca M, et al. : Investigations into resting-state connectivity using independent component analysis. Philos. Trans. R. Soci. B: Biol. Sci. 360, 1001–1013 (2005) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hafkemeijer A, Altmann-Schneider I, Craen AJ, Slagboom PE, Grond J, Rombouts SA: Associations between age and gray matter volume in anatomical brain networks in middle-aged to older adults. Aging Cell 13, 1068–1074 (2014) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Du Y, Fan Y: Group information guided ICA for fMRI data analysis. NeuroImage 69, 157–197 (2013) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Calhoun VD, Adali T: Multisubject independent component analysis of fMRI: a decade of intrinsic networks, default mode, and neurodiagnostic discovery. IEEE Rev. Biomed. Eng. 5, 60–73 (2012) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Du Y, Lin D, et al. : Comparison of IVA and GIG-ICA in brain functional network estimation using fMRI data. Front. Neurosci. 11, 267 (2017) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boyd S, Vandenberghe L: Convex Optimization. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge: (2004) [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao Y, Dong Q, et al. : Automatic recognition of fMRI-derived functional networks using 3D convolutional neural networks. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 65, 1975–1984 (2017) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]