Abstract

Background:

The impact of smoking on oral health is directly related to the toxic tobacco fumes. The study aimed to investigate the awareness of the link between smoking and periodontal disease among the population seeking periodontal treatment.

Materials and Methods:

A self-administered questionnaire constructed in local Malay language consisting of 13 questions on sociodemographic details and 10 questions on the knowledge domain was distributed to eligible respondents while they were waiting for their consultation in the periodontal clinic waiting hall. There were 330 study participants aged 16 years old and above, who participated in this study from all 12 dental clinics in the state of Perlis, Malaysia. Data were entered into Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 20.0 for analysis. Descriptive statistics were used to describe the sociodemographic data, whereas association between potential factor and the knowledge of awareness was found using the Pearson Chi-square test of independence or a Fisher's exact test, depending on the eligibility criteria.

Results:

Our study showed that 4.5% (n = 15) of the respondents were not aware that smoking did add risk for oral cancer, 14.5% (n = 48) were not aware that smoking could cause gum disease. Smoking status was significantly associated with the awareness of smoking effect on gum disease (P = 0.002). The proportion of the active smokers being aware that smoking could potentially cause gum disease was considerably less as compared to the nonsmokers (62.7% vs. 83.3%).

Conclusions:

Continuous dental health campaigns and awareness program are crucial to instil awareness and health-seeking behavior as well as to enforce public's knowledge.

Key words: Dental care, oral health, periodontal diseases, smokers, surveys and questionnaires

INTRODUCTION

Tobacco inhalation refers to the inhalation of smoke from the burned leaves of tobacco plant, most often prepared in the form of cigarettes. Smokers are two to seven times more likely to present with periodontitis as compared to the nonsmokers,[1,2] and they are more likely to develop tooth loss during periodontal maintenance as well.[3] Smoking has been established as a salient risk factor for several systemic diseases including lung carcinoma, respiratory diseases, and cardiovascular diseases.[4] There is an overwhelming evidence that tobacco use produces harmful effect in the mouth ranging from cosmetic issues, such as tooth staining or discoloration to potentially life-threatening illnesses such as oral cancer.[5] Smoking is known to increase the susceptibility of individuals to develop periodontal disease, further causing poorer response to both surgical and nonsurgical periodontal therapies.[6]

Periodontal disease is a heterogeneous group of disorders affecting the periodontium; the most common of which are gingivitis and chronic periodontitis.[7] Chronic periodontitis is a common form of destructive oral disease in adults. Cases of untreated periodontitis inevitably result in teeth loss, impaired mastication, and poor esthetics, coupled with its adverse effects on overall health, quality of life, and the economic productivity.

Smoking has been recognized to be linked to lung disease, cardiovascular disease, and poor pregnancy outcomes, such as miscarriage and intrauterine growth restriction.[8] Furthermore, smoking was found to affect dental health by accelerating the onset, severity, and progression of periodontal disease,[9,10] contributed by the development of a favorable milieu for periodontal pathogens inside the oral cavity.[11] Hence, tobacco use, particularly as inhalational substance is the most important, preventable risk factor in the prevalence and progression of periodontal diseases, globally.[12]

Tobacco inhalation impinges on a wide spectrum of periodontal treatment approaches including the mechanical debridement and local and systemic antimicrobial therapy to periodontal surgery which includes regenerative procedures and oral implants.[13] The smoking association to the development of periodontal disease is particularly strong that it merits a stand-alone diagnosis of smoking-associated periodontitis, characterized by a fibrotic gingiva, limited gingival redness, and edema relative to the disease severity. Furthermore, smoking-associated periodontitis also has a proportionally greater pocketing in the anterior and maxillary lingual sites and distinct gingival recession at the anterior sites, in addition to the lack of association between periodontal status and the level of oral hygiene.[14]

Moreover, smokers demonstrate more dental calculus as compared to the nonsmokers, which correlates well to the frequency and duration of their smoking habit.[15,16,17] On the other hand, smoking cessation may potentially restore periodontal health and encourage oral microbial healing[18,19] by slowing down the rate of periodontal breakdown and even promoting some degree of repair and regeneration of the periodontal tissues.

Despite the established negative effects of smoking on oral health, there is a paucity of studies conducted in examining dental patients' knowledge and awareness, particularly in the Asian region. The aim of this study was to assess the awareness and knowledge of smoking effects on oral health among patients attending the government dental clinics in Northwest Malaysia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A cross-sectional survey was conducted from May 1, 2015 until to July 31, 2017. A self-administered questionnaire was delivered to patients attending any of the 12 government dental clinics available throughout the state of Perlis, Malaysia.

The questionnaire comprised two domains, 13 questions from the sociodemography domain and 10 questions from the knowledge domain. Patients 16 years old and above, regardless of gender and irrespective of smoking history, Malay language-literate, and those who gave verbal and written consent to participate in the survey were included in the study, whereas those who were nonMalaysian citizen were excluded. A convenient sampling was used.

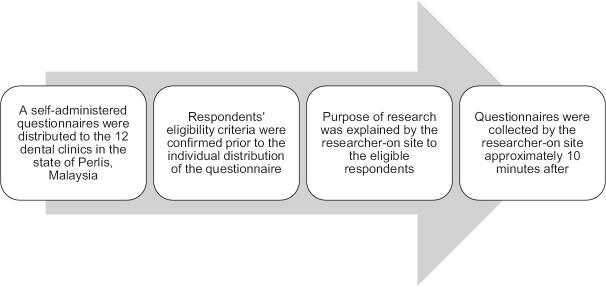

The questionnaire was distributed to the respondents during their waiting time at the waiting hall during the clinic session. The filled-up questionnaire forms were then collected by the dedicated study associate approximately 10–15 min afterward. The flowchart of the recruitment process is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the respondent's recruitment process

The knowledge domain's questionnaire comprised 10 questions which were espoused from a study validated by Nwhator et al.[20] and was translated into Malay language using the standard “forward-backward” translation procedure. A pilot study using the translated questionnaire was conducted among 31 study respondents to assess the appropriateness of the questions. The questions were found to be unambiguous and easy to respond to. A good Cronbach alpha value of 0.827 was established with the translated Malay questionnaire. The pilot study participants were not included in the main study.

Sample size estimation was calculated using the population proportion formulae.[21] Prior data indicated that the proportion of public agreeing that smoking was hazardous to health was 0.96[20] in a population size of 992. The Type I error probability and precision were preset at 0.05 and 0.05, respectively, and together with an additional of 20% dropout rate, given the sample size of at least 70 samples.

Data were entered using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 20.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 20.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp). Sociodemographic data were described using descriptive statistics, whereas the association between different factors and awareness of the link between smoking status and oral health were calculated using the Pearson Chi-square test of independence or a Fisher's exact test, depending on the eligibility criteria.

In the actual study, a total of 330 respondents were recruited from all 12 government dental clinics in a single Northwest state of Peninsular Malaysia. Respondents were selected based on a nonrandom selection, according to their availability and convenience.

The study has received ethical clearance from the Medical Research and Ethics Committee, Ministry of Health Malaysia with the registration number NMRR-15-2512-27750.

RESULTS

Sociodemography

The study successfully recruited a total of 330 study respondents. There were no differences in the baseline sociodemographic characteristics of the study respondents, as observed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline sociodemographic characteristics among the study respondents with regard to awareness that smoking is injurious to dental health

| Sociodemographic variable | n (%) | P* |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 143 (43.3) | 0.133 |

| Female | 187 (56.7) | |

| Age (years old) | ||

| <20 | 26 (7.9) | 0.868† |

| 20-50 | 255 (77.3) | |

| 51-70 | 49 (14.8) | |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Malay | 290 (87.9) | 0.095 |

| Chinese | 28 (8.5) | |

| Indian | 3 (0.9) | |

| Others | 9 (2.7) | |

| Education level | ||

| Secondary school | 118 (35.8) | 0.794 |

| College | 65 (19.7) | |

| University | 101 (30.6) | |

| Others | 46 (13.9) | |

| Smoking status | ||

| Actively smoking | 75 (22.7) | 0.759 |

| Nonsmoker | 252 (76.4) | |

| Ex-smoker | 3 (0.9) | |

| Smoking duration (years) | ||

| <1 | 6 (1.8) | 0.643 |

| 1-5 | 21 (6.4) | |

| >5 | 15 (4.5) | |

| >10 | 33 (10) | |

| Last dental visit | ||

| 0-6 months | 125 (37.8) | 0.276 |

| 7-12 months | 55 (16.7) | |

| >12 months | 128 (38.8) | |

| Never | 22 (6.7) |

*Pearson Chi-square test of independence.

†Independent t-test. P<0.05 is considered significant. n – Frequency; P – Probability value

Among our overall study respondents, 75 (22.7%) were active smokers. The study found that there were 54 (72.0%) patients who had attempted to stop smoking in the past but failed. Among the top motivational drives for those who attempted to stop smoking include newly-diagnosed health-related illnesses, n = 25 (33.3%) and the increasing market cost of tobacco, n = 24 (32.0).

Majority of the respondents recruited were nonsmokers, n = 252 (76.4%); currently smoking, n = 75 (22.7%); and ex-smokers, n = 3 (0.9%). Up to 10% (n = 33) of the currently-smoking respondents have been smoking for more than 10 years.

The respondents were predominantly female, n = 187 (56.7%) as compared to male, n = 143 (43.3%). Malays contributed to the largest ethnic volume of 87.9% Table 1.

Awareness of effect of smoking on periodontal disease and specific oral health

Our study found that 4.5% (n = 15) of the respondents were not aware that smoking did add risk for oral cancer, 14.5% (n = 48) were not aware that smoking could cause periodontal diseases. The link between smoking and delayed wound healing was acknowledged by 78.2% (n = 258) of the respondents, but 8.8% (n = 29) revealed that they did not know if this relationship existed and 12.7% (n = 42) incorrectly stated that this association did not exist.

There was only 39.1% (n = 129) of the respondents who correctly answered that smoking did not relate to tooth decay or caries while a staggering 51.8% (n = 171) of the respondents erroneously thought that there was such an association. Furthermore, the nonsmokers were found to be more aware of the smoking effects on oral health than do smokers [Table 2].

Table 2.

Awareness on the effect of smoking on oral health

| Smoking effect | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Gum disease | 259 (78.0) |

| Oral cancer | 287 (87.0) |

| Teeth discoloration | 279 (84.5) |

| Bad breath | 310 (93.9) |

| Dental caries | 171 (51.8) |

| Delayed healing | 258 (78.2) |

| Altered taste | 257 (77.9) |

| Oral ulcer | 279 (84.5) |

P<0.05 is considered statistically significant.n – Frequency; P – Probability value

Awareness of the effect of smoking on general health, oral health, and periodontal diseases versus smoking status

The vast majority of the respondents were already aware of the harmful effect of smoking to the general and oral health. Smoking status was not significantly associated with the awareness that smoking is injurious to general health (P = 0.395) and oral health (P = 0.880) as observed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Association between smoking status and awareness of smoking effects on general health, oral health, and gum disease

| Study variable | Smoking status, n (%) |

P* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active smoker | Nonsmoker | Ex-smoker | ||

| Awareness of smoking affecting general health | ||||

| Yes | 71 (23.7) | 225 (75.3) | 3 (1.0) | 0.395 |

| No | 4 (12.9) | 27 (87.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Awareness of smoking affecting oral health | ||||

| Yes | 68 (23.1) | 224 (75.9) | 3 (1.0) | 0.880 |

| No | 7 (20.0) | 28 (80.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Awareness of smoking causing gum disease | ||||

| Yes | 47 (18.1) | 210 (81.1) | 2 (0.8) | 0.002 |

| No | 19 (39.6) | 28 (58.3) | 1 (2.1) | |

| Not sure | 9 (39.1) | 14 (60.9) | 0 (0.0) | |

*Fisher’s exact test. P<0.05 is considered significant. n – Frequency; P – Probability value

Smoking status was significantly associated with the awareness of smoking effect on periodontal diseases (P = 0.002) while nonsmokers were more aware that smoking causes gum disease as compared to smokers (83.3% vs. 62.7%).

Awareness of the effect of smoking on periodontal health

There were 78.5% (n = 259) of the respondents who were aware that smoking causes gum disease and 81.1% (n = 210) among these respondents were nonsmokers. Further statistical analysis showed that gender (P < 0.001) and smoking status (P = 0.002) were significantly associated with the awareness of respondents to the harmful effects of smoking on periodontal health [Table 3].

Even though the majority of the respondents were aware of the association between smoking and periodontal health, yet there were still 48 (14.5%) respondents who were still not aware of this bad effect of smoking on periodontal health and 23 (7%) were not sure whether smoking did add risk to periodontal diseases.

We found that there was no significant association between education level and the awareness of smoking causing periodontal diseases (P = 0.219) [Table 4]. Out of the 75 self-proclaimed smoker respondents, majority of them had attempted to stop smoking before (n = 54, 72.0%) due to health problems (n = 25, 33.3%).

Table 4.

Univariate analysis on the association of different variables with respondents’ awareness of the link between smoking and periodontal disease

| Variable | Aware smoking causes periodontal disease, n (%) | Not aware smoking causes periodontal disease, n (%) | Not sure whether smoking causes periodontal disease, n (%) | P a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 99 (69.2) | 26 (18.2) | 18 (12.6) | <0.001 |

| Female | 160 (85.6) | 22 (11.8) | 5 (2.6) | |

| Age (years old) | ||||

| <20 | 16 (61.5) | 5 (19.2) | 5 (16.8) | 0.019 |

| 20-50 | 209 (82.0) | 33 (12.9) | 13 (5.1) | |

| 51-0 | 34 (69.4) | 10 (20.4) | 5 (10.2) | |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Malay | 224 (77.2) | 46 (15.9) | 20 (6.9) | 0.046 |

| Chinese | 27 (96.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.6) | |

| Indian | 2 (66.7) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (33.3) | |

| Others | 6 (66.7) | 2 (22.2) | 1 (11.1) | |

| Education level | ||||

| Secondary school | 88 (74.6) | 19 (16.1) | 11 (9.3) | 0.219 |

| College | 52 (80.0) | 9 (13.8) | 4 (6.2) | |

| University | 87 (86.1) | 9 (8.9) | 5 (5.0) | |

| Others | 32 (69.6) | 11 (23.9) | 3 (6.5) | |

| Smoking status | ||||

| Active smoker | 47 (62.7) | 19 (25.3) | 9 (12.0) | 0.002 |

| Nonsmoker | 210 (83.3) | 28 (11.1) | 14 (5.6) | |

| Ex-smoker | 2 (66.7) | 1 (33.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Smoking duration (years) | ||||

| <1 | 3 (50.0) | 2 (33.3) | 1 (16.7) | 0.001b |

| 1-5 | 12 (57.2) | 4 (19.0) | 5 (23.8) | |

| >5 | 8 (53.3) | 6 (40.0) | 1 (6.7) | |

| >10 | 24 (72.7) | 7 (21.2) | 2 (6.1) |

aPearson Chi-square test of independence, bFisher’s exact test. P<0.05 is considered significant. n – Frequency; P – Probability value

DISCUSSION

Decades of intensive research have unequivocally acknowledged that smoking has a profound direct negative effect on oral health. Smoking has been established as a significant risk factor for periodontal diseases.[22] Tobacco reduces the blood flow to the gingivae, further depriving them of oxygen and nutrients, preventing the gums from staying healthy, and eventually leaving them vulnerable to bacterial infection.

Our study demonstrated less number of smoker participants, at 22.7% (n = 75) as compared to other studies at 43.2%[23] and 30%.[24] In addition, our finding of 75.9% of the nonsmokers being aware of the bad effect of tobacco on dental health further established the fact that the nonsmokers were more health-conscious and may be less likely to start smoking in the future. However, a regular counseling and guidance from a dental practitioner during the dental visit are deemed necessary to secure their nonsmoker status.

Our finding of 78.5% (n = 259) respondents who agreed that smoking was linked to periodontal disease demonstrated a high level of public awareness, contrasting previous reports by Lung et al.[23] in the United Kingdom which reported the level of awareness at only 7%, a study in Nigeria by Nwhator et al.(2010)[20] with 2.2%, and a study by Shetty[25] in Kingdom of Arab Saudi which reported the level of awareness at a measly 11.3%. This may be contributed by the successful efforts of the local agencies at creating awareness, health education campaigns, counseling, and provisions of stop-smoking clinic in all major districts in Malaysia. The positive role of the managing dentist in achieving the smoking cessation activities is highlighted despite their busy clinic schedule.

Certainly, we also found that 13% (n = 42) of the study respondents were unaware that smoking could cause oral cancer despite the high prevalence of oral cancer worldwide. Moreover, 14.5% (n = 48) of the respondents were not aware that smoking could potentially cause periodontal disease. These findings should alert the clinicians that there is still a portion of the population yet to be educated and would surely benefit from regular dental health promotion strategies.

There were 6.4% of the actively smoking respondents who had never attempted to stop smoking before and did not consider to stop smoking in the near future. Despite the small percentage, concern should be raised to increase the knowledge and awareness regarding the risk of smoking to the development of periodontal diseases in this population. Furthermore, among those who had attempted to quit smoking, they were found to be more concerned of their esthetic appearances such as tooth discoloration and halitosis, than their oral health as the motivational drive.

CONCLUSION

Majority of the dental patients in our locality had a good knowledge about the systemic and oral effect of smoking. Esthetic values and social effects were important standards to our respondents, hence could be incorporated as the motivating drive during smoking-cessation counseling. Continuous dental health campaigns and awareness program delineating the association of smoking and periodontal disease should be regularly implemented to enforce the public's knowledge.

Smokers, who have been treated for periodontal diseases, should be monitored regularly and undergo routine professional evaluation, reinforced on good oral hygiene practice, and be given prophylaxis after completion of periodontal treatment to avoid recurrence. Moreover, the managing dental team could identify the patients who desire to stop smoking and subsequently refer them to the nearest Smoking Cessation Clinic in the district for further management.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

The author would like to thank the Director General of Health Malaysia for his permission to publish the paper. The author would also like to extend her gratitude to the Perlis State Deputy Director of Dental Health, Dr. Hjh Farehah Hj Othman for her tenacity and constructive criticisms during the manuscript review and editing. Sincere appreciation for Dr. Karniza Khalid from Clinical Research Centre, Hospital Tuanku Fauziah, Perlis, Malaysia, for her technical assistance in the statistical analysis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Susin C, Oppermann RV, Haugejorden O, Albandar JM. Periodontal attachment loss attributable to cigarette smoking in an urban Brazilian population. J Clin Periodontol. 2004;31:951–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.2004.00588.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tomar SL, Asma S. Smoking-attributable periodontitis in the United States: Findings from NHANES III. National health and nutrition examination survey. J Periodontol. 2000;71:743–51. doi: 10.1902/jop.2000.71.5.743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chambrone L, Chambrone D, Lima LA, Chambrone LA. Predictors of tooth loss during long-term periodontal maintenance: A systematic review of observational studies. J Clin Periodontol. 2010;37:675–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2010.01587.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnson NW, Bain CA. Tobacco and oral disease. EU-working group on tobacco and oral health. Br Dent J. 2000;189:200–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4800721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reibel J. Tobacco and oral diseases. Update on the evidence, with recommendations. Med Princ Pract. 2003;12(Suppl 1):22–32. doi: 10.1159/000069845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Preber H, Bergström J. Effect of non-surgical treatment on gingival bleeding in smokers and non-smokers. Acta Odontol Scand. 1986;44:85–9. doi: 10.3109/00016358609041312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pihlstrom BL, Michalowicz BS, Johnson NW. Periodontal diseases. Lancet. 2005;366:1809–20. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67728-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wald NJ, Hackshaw AK. Cigarette smoking: An epidemiological overview. Br Med Bull. 1996;52:3–11. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a011530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.ALHarthi SSY, Natto ZS, Midle JB, Gyurko R, O'Neill R, Steffensen B, et al. Association between time since quitting smoking and periodontitis in former smokers in the national health and nutrition examination surveys (NHANES) 2009 to 2012. J Periodontol. 2018. pp. 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1002/JPER.18-0183 . [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Eke PI, Thornton-Evans GO, Wei L, Borgnakke WS, Dye BA, Genco RJ, et al. Periodontitis in US adults: National health and nutrition examination survey 2009-2014. J Am Dent Assoc. 2018;149:576–88000000. doi: 10.1016/j.adaj.2018.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ismail AI, Burt BA, Eklund SA. Epidemiologic patterns of smoking and periodontal disease in the United States. J Am Dent Assoc. 1983;106:617–21. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1983.0137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grossi SG, Zambon JJ, Ho AW, Koch G, Dunford RG, Machtei EE, et al. Assessment of risk for periodontal disease. I. Risk indicators for attachment loss. J Periodontol. 1994;65:260–7. doi: 10.1902/jop.1994.65.3.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson GK, Hill M. Cigarette smoking and the periodontal patient. J Periodontol. 2004;75:196–209. doi: 10.1902/jop.2004.75.2.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haber J. Smoking is a major risk factor for periodontitis. Curr Opin Periodontol. 1994;12:12–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martinez-Canut P, Lorca A, Magán R. Smoking and periodontal disease severity. J Clin Periodontol. 1995;22:743–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1995.tb00256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bergström J, Eliasson S, Dock J. Exposure to tobacco smoking and periodontal health. J Clin Periodontol. 2000;27:61–8. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2000.027001061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Califano JV, Schifferle RE, Gunsolley JC, Best AM, Schenkein HA, Tew JG, et al. Antibody reactive with Porphyromonas gingivalis serotypes K1-6 in adult and generalized early-onset periodontitis. J Periodontol. 1999;70:730–5. doi: 10.1902/jop.1999.70.7.730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaldahl WB, Johnson GK, Patil KD, Kalkwarf KL. Levels of cigarette consumption and response to periodontal therapy. J Periodontol. 1996;67:675–81. doi: 10.1902/jop.1996.67.7.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grossi SG, Zambon J, Machtei EE, Schifferle R, Andreana S, Genco RJ, et al. Effects of smoking and smoking cessation on healing after mechanical periodontal therapy. J Am Dent Assoc. 1997;128:599–607. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1997.0259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nwhator S, Ayanbadejo PO, Arowojolu MO, Akhionbare O, Oginni AO. Awareness of link between smoking and periodontal disease in Nigeria: A comparative study. Res Rep Trop Med. 2010;1:45–51. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lemeshow S, Hosmer DW, Klar J, Lwanga SK. Adequacy of sample size in health studies. World Health Organ. 1990;4:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Petersen PE, Bourgeois D, Ogawa H, Estupinan-Day S, Ndiaye C. The global burden of oral diseases and risks to oral health. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83:661–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lung ZH, Kelleher MG, Porter RW, Gonzalez J, Lung RF. Poor patient awareness of the relationship between smoking and periodontal diseases. Br Dent J. 2005;199:731–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4812971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Terrades M, Coulter WA, Clarke H, Mullally BH, Stevenson M. Patients' knowledge and views about the effects of smoking on their mouths and the involvement of their dentists in smoking cessation activities. Br Dent J. 2009;207:E22. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2009.1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shetty AC. Patient's awareness of the relationship between smoking and periodontal diseases in kingdom of Saudi Arabia. J Dent Oral Hyg. 2015;7:60–3. [Google Scholar]