Abstract

Background

Case series and a post hoc subgroup analysis of a large randomized trial have suggested a potential benefit in treating ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms (rAAAs) using endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) with local anaesthesia (LA) rather than general anaesthesia (GA). The uptake and outcomes of LA in clinical practice remain unknown.

Methods

The UK National Vascular Registry was interrogated for patients presenting with rAAA managed with EVAR under different modes of anaesthesia between 1 January 2014 and 31 December 2016. The primary outcome was in‐hospital mortality. Secondary outcomes included: the number of centres performing EVAR under LA; the proportion of patients receiving this technique; duration of hospital stay; and postoperative complications.

Results

Some 3101 patients with rAAA were treated in 72 hospitals during the study: 2306 underwent on open procedure and 795 had EVAR (LA, 319; GA, 435; regional anaesthesia, 41). Overall, 56 of 72 hospitals (78 per cent) offered LA for EVAR of rAAA. Baseline characteristics and morphology were similar across the three EVAR subgroups. Patients who had surgery under LA had a lower in‐hospital mortality rate than patients who received GA (59 of 319 (18·5 per cent) versus 122 of 435 (28·0 per cent)), and this was unchanged after adjustment for factors known to influence survival (adjusted hazard ratio 0·62, 95 per cent c.i. 0·45 to 0·85; P = 0·003). Median hospital stay and postoperative morbidity from other complications were similar.

Conclusion

The use of LA for EVAR of rAAA has been adopted widely in the UK. Mortality rates appear lower than in patients undergoing EVAR with GA.

Short abstract

Improves 30‐day survival

Introduction

Without emergency surgical intervention, ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm (rAAA) is usually fatal. Global experience with endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) for elective abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) has led to its increasing use in the emergency setting1, 2. Comparative outcomes between conventional open and endovascular repair for ruptured AAA (rEVAR) have been assessed in one case series3 and four RCTs4, 5, 6, 7. A recent individual‐patient meta‐analysis8 of three RCTs that compared EVAR with open repair for rAAA reported that women might benefit more from the EVAR approach and that patients are discharged sooner after EVAR, although survival at 90 days was similar in the two groups. Despite this, earlier discharge from critical care, shorter hospital stay, and a higher proportion discharged directly home in the EVAR group means that the EVAR approach is likely to gain further support for its use in rAAA, especially in specialist centres. Furthermore, the EVAR approach for rAAA may allow treatment of more elderly patients and those with significant co‐morbidities who would not be considered feasible candidates for open surgery2.

A case series3 of 20 patients, published in 2002, demonstrated the feasibility of performing rEVAR under local anaesthesia (LA). A subsequent post hoc subgroup analysis of a cohort of 186 patients who underwent rEVAR in the IMPROVE (Immediate Management of the Patient with Rupture: Open Versus Endovascular repair) trial9 demonstrated a significantly reduced 30‐day mortality rate for patients operated on under LA compared with surgery under general anaesthesia (GA): odds ratio 0·27 (95 per cent c.i. 0·10 to 0·70), after adjustment for potential confounding. The magnitude of benefit observed with LA in the IMPROVE trial warrants further investigation and, if replicated in a well conducted RCT, would suggest that LA should become the standard of care in rEVAR. However, at this stage little is known about how applicable this technique might be to patients in everyday clinical practice and how widely the technique has been adopted across the UK.

The UK National Vascular Registry (NVR), which captures data on more than 90 per cent of AAA procedures, provides a unique opportunity to examine practice and outcomes in a real‐world setting, and includes centres that may not have contributed patients to the IMPROVE trial7, 9, 10. The aim of this study was to quantify the uptake of LA for rEVAR across all UK vascular centres and evaluate whether the benefit of LA observed in the IMPROVE trial has been replicated in everyday clinical practice.

Methods

National Vascular Registry

The NVR was commissioned by the Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership (HQIP), as part of the National Clinical Audit and Patient Outcomes Programme, to measure quality of care and outcomes in patients undergoing vascular interventions in National Health Service (NHS) hospitals10. Data submission is mandatory and forms part of the revalidation of vascular surgeons. Data are assessed for consistency, including range checks, and also comparison of case ascertainment with the Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) data set, to which all NHS Trusts in England are obliged to contribute for financial probity11. Equivalent checks were applied to data for patients operated on in Scotland (Scottish Morbidity Record, SMR01), Wales (Patient Episode Database for Wales) and Northern Ireland (Hospital Activity Statistics). The NVR is the largest recognized register of AAA procedures in the UK. Permission was obtained from HQIP for the NVR to release anonymized patient data under a data‐sharing agreement signed between HQIP and the University of Bristol.

Study population

The study population comprised patients undergoing repair of a rAAA in the UK between 1 January 2014 and 31 December 2016. The registry classifies each procedure as open, EVAR, complex EVAR, revision open, revision EVAR or endovascular aneurysm sealing (EVAS), and the AAAs were grouped into asymptomatic, symptomatic unruptured, ruptured, aortic transection, acute dissection or chronic dissection. The EVAR and EVAS procedures were combined. The following were excluded: aortic transections, acute and chronic dissections, thoracic aneurysms and thoracoabdominal aneurysms. Case ascertainment for the NVR for the period 2014–2016 was 91 per cent for rAAA12.

Mode of anaesthesia

Modes of anaesthesia captured in the NVR include GA, LA and regional anaesthesia (RA). The NVR does not identify procedures that were initiated under LA only but then converted to GA (or RA) later in the procedure. Such procedures are coded as GA or RA, as appropriate.

Data collection

Data items included in the NVR and available for analysis are summarized in Appendix S1 (supporting information). The Hardman index13 for predicting the risk of an adverse outcome is not captured in the NVR. However, four of the five factors used to derive the index are included. Therefore, a modified Hardman index was derived based on age, haemoglobin, serum creatinine and ECG findings only (excluding data on loss of consciousness).

Study outcomes

The primary outcome of this study was in‐hospital mortality. Hospital discharge was defined as discharge from the hospital in which the vascular surgical procedure was performed. Patients could be discharged home, to a referring hospital, or to a rehabilitation hospital. Secondary clinical outcomes included postoperative length of hospital stay (LOS), ICU admission rate, duration of ICU stay and postoperative complications. Secondary process outcomes included uptake of EVAR for rAAA across centres and use of LA for these procedures.

Statistical analysis

Continuous data are summarized as mean(s.d.) values (or median (i.q.r.) if the distribution is skewed). Categorical data are summarized as a number and percentage. Patients undergoing EVAR were grouped by the type of anaesthesia received: LA, GA or RA. Standardized mean differences were calculated to quantify the differences between baseline characteristics and the aortic morphology of patients undergoing EVAR under GA and LA.

Cox proportional hazards regression was used to compare in‐hospital mortality by mode of anaesthesia. Survivors were censored at hospital discharge. The analysis was adjusted for modified Hardman index13, ASA fitness grade, maximum AAA diameter and sex, and centre fitted as a frailty term. Kaplan–Meier curves were constructed to estimate mortality rates to 30 days. Secondary outcomes are described, but not compared formally. For duration of ICU and hospital stay, patients who died before hospital discharge were censored at death.

Missing data are described in table footnotes. Multiple imputation was used to account for missing data in analyses. Fifty‐two imputed data sets were generated and the results combined using Rubin's rules14. Sensitivity analyses with missing data items for the Hardman index were assigned 0 points (sensitivity analysis 1) or 1 point (sensitivity analysis 2). All analyses were performed in Stata® version 15.1 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA).

Results

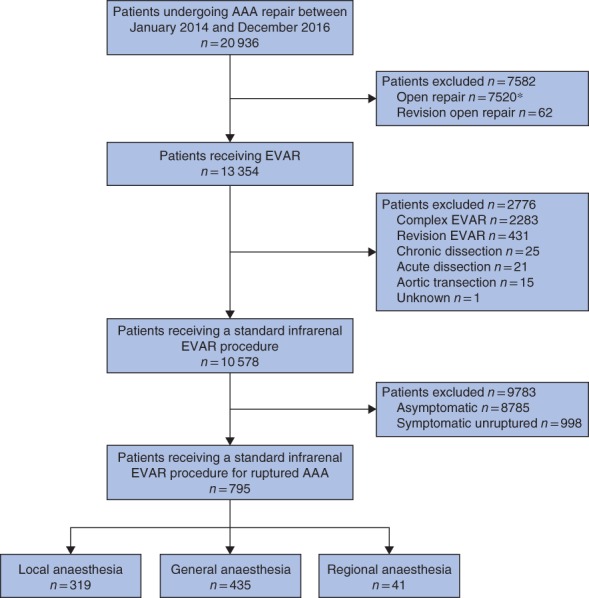

Between January 2014 and December 2016, the NVR collected data on 20 936 patients undergoing AAA repair, 13 354 (63·8 per cent) of whom underwent EVAR. Of these 13 354 patients, 795 (6·0 per cent) had rEVAR (Fig. 1). The majority of patients undergoing rEVAR received GA (435, 54·7 per cent), with 319 (40·1 per cent) having LA and 41 (5·2 per cent) RA.

Figure 1.

Study profile. *Of 7520 open repairs, 2306 were for ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA). EVAR, endovascular aneurysm repair

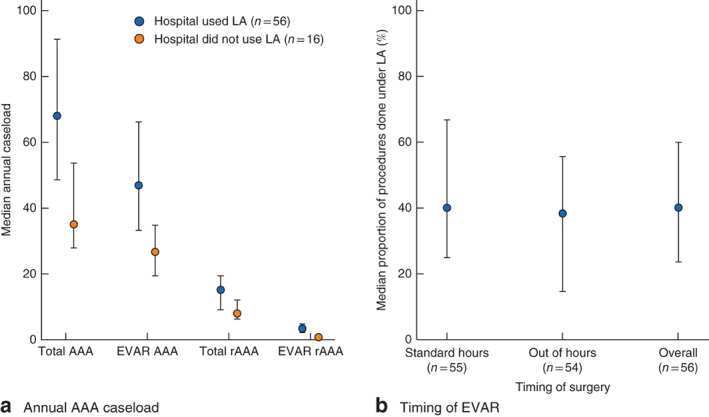

rEVAR procedures were carried out across 72 hospitals, 56 (78 per cent) of which performed at least one procedure under LA. The hospitals that used LA for rEVAR were the higher‐volume centres carrying out a median of 47·0 EVAR and 15·2 rAAA procedures each year, compared with a median of 26·7 EVAR and 7·9 rAAA procedures in the non‐LA centres (Fig. 2 a; Table S1, supporting information). Across the 56 centres performing rEVAR under LA, a median of 40·0 (i.q.r. 22·6–60·0) per cent of procedures used LA, and the rate was similar for procedures performed during standard working hours (08.00 to 17.00 hours Monday to Friday) and procedures performed out of hours (Fig. 2 b; Table S2, supporting information).

Figure 2.

Use of local anaesthesia (LA) according to a median annual abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) caseload and b timing of endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR). Values are median (i.q.r.). Standard hours are defined as operation start time from 08.00 to 17.00 hours Monday to Friday. rEVAR, ruptured endovascular aneurysm repair

Patient characteristics

Mean age was 79 years in the LA and RA groups and 77 years in the GA group; the majority of patients were men (Table 1). Over 85 per cent of patients had co‐morbidities and 15 per cent were moribund (ASA grade V). Of patients with data, only 16·6 per cent had none of the four risk factors included in the modified Hardman index, and 12·3 per cent had at least three risk factors. The mean maximum AAA diameter exceeded 72 mm in all groups. Characteristics of patients in the LA and GA groups were similar, as indicated by the small mean differences (less than 0·2) for most factors examined.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients undergoing emergency endovascular aneurysm repair

| LA (n = 319) | GA (n = 435) | RA (n = 41) | MD (LA versus GA) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age (years)* | 79·4(8·2) | 77·0(9·0) | 79·9(7·3) | 0·27 |

| Sex ratio (M : F) | 274 : 45 | 368 : 67 | 37 : 4 | 0·04 |

| Smoking status | ||||

| Current or stopped < 2 months previously | 61 (19·1) | 113 of 431 (26·2) | 9 (22) | −0·17 |

| Ex‐smoker | 196 (61·4) | 240 of 431 (55·7) | 23 (56) | 0·12 |

| Never smoker | 62 (19·4) | 78 of 431 (18·1) | 9 (22) | 0·03 |

| ASA grade | ||||

| I (normal) | 1 (0·3) | 3 (0·7) | 0 (0) | −0·05 |

| II (mild disease) | 8 (2·5) | 16 (3·7) | 2 (5) | −0·07 |

| III (severe, not life‐threatening) | 41 (12·9) | 64 (14·7) | 12 (29) | −0·05 |

| IV (severe, life‐threatening) | 219 (68·7) | 287 (66·0) | 23 (56) | 0·06 |

| V (moribund) | 50 (15·7) | 65 (14·9) | 4 (10) | 0·02 |

| AAA maximum diameter (mm)* | 75·8(17·7) | 72·8(20·1) | 72·6(21·4) | 0·16 |

| Cardiovascular risk factors | ||||

| Co‐morbidity on admission (any) | 276 (86·5) | 386 (88·7) | 36 (88) | −0·07 |

| Diabetes | 42 (13·2) | 66 (15·2) | 5 (12) | −0·06 |

| Hypertension | 220 (69·0) | 285 (65·5) | 21 (51) | 0·07 |

| Stroke | 21 (6·6) | 31 (7·1) | 3 (7) | −0·02 |

| Ischaemic heart disease | 125 (39·2) | 177 (40·7) | 19 (46) | −0·03 |

| Chronic heart failure | 28 (8·8) | 32 (7·4) | 3 (7) | 0·05 |

| Chronic renal disease | 55 (17·2) | 77 (17·7) | 11 (27) | −0·01 |

| Chronic lung disease | 98 (30·7) | 113 (26·0) | 19 (46) | 0·11 |

| Hardman index | ||||

| Age > 76 years | 217 (68·0) | 262 of 434 (60·4) | 29 (71) | 0·16 |

| Haemoglobin < 9 g/dl | 20 of 152 (13·2) | 35 of 219 (16·0) | 3 of 12 (25) | −0·08 |

| Serum creatinine > 190 μmol/l | 29 of 318 (9·1) | 42 of 434 (9·7) | 3 (7) | −0·02 |

| Abnormal ECG | 149 of 284 (52·5) | 176 of 377 (46·7) | 20 of 38 (53) | 0·12 |

| No. of Hardman factors (complete case) | ||||

| 0 | 18 of 136 (13·2) | 35 of 179 (19·6) | 1 of 10 (10) | −0·17 |

| 1 | 55 of 136 (40·4) | 63 of 179 (35·2) | 5 of 10 (50) | 0·11 |

| 2 | 47 of 136 (34·6) | 59 of 179 (33·0) | 2 of 10 (20) | 0·03 |

| 3 | 15 of 136 (11·0) | 20 of 179 (11·2) | 1 of 10 (10) | −0·005 |

| 4 | 1 of 136 (0·7) | 2 of 179 (1·1) | 1 of 10 (10) | −0·04 |

| No. of Hardman factors (imputed) | ||||

| 0 | 46 (14·4) | 89 (20·5) | 5 (12) | −0·16 |

| 1 | 137 (42·9) | 175 (40·2) | 18 (44) | 0·06 |

| 2 | 105 (32·9) | 140 (32·2) | 15 (37) | 0·02 |

| 3 | 30 (9·4) | 28 (6·4) | 2 (5) | 0·11 |

| 4 | 1 (0·3) | 3 (0·7) | 1 (2) | −0·05 |

Values in parentheses are percentages unless indicated otherwise;

values are mean(s.d.) with data missing for one patient in the general anaesthesia (GA) group. LA, local anaesthesia; RA, regional anaesthesia; MD, mean difference; AAA, abdominal aortic aneurysm.

Patients undergoing open surgery for rAAA were slightly younger and had fewer risk factors than those having rEVAR (Table S3, supporting information).

Outcomes

Overall, 187 of 795 patients (23·5 per cent) undergoing rEVAR died before hospital discharge (Table 2). The in‐hospital mortality rate was highest in the GA group, 28·0 per cent, followed by 18·5 per cent in the LA group and 15 per cent in the RA group. After adjustment, the risk of death in patients having rEVAR under LA was 38 per cent lower than the risk under GA (adjusted hazard ratio 0·62, 95 per cent c.i. 0·45 to 0·85; P = 0·003).

Table 2.

Postoperative outcomes following emergency endovascular aneurysm repair

| LA (n = 319) | GA (n = 435) | RA (n = 41) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | |||

| In‐hospital death | 59 (18·5) | 122 (28·0) | 6 (15) |

| PostoperativeLOS (days)*† | 10 (6–18) | 10 (6–21) | 9 (5–16) |

| Admitted to ICU‡ | 205 of 258 (79·5) | 262 of 329 (79·6) | 28 of 35 (80) |

| Duration of ICUstay (days)*† | 2 (1–4) | 3 (1–5) | 2 (2–4) |

| Complications | |||

| Cardiac | 42 of 308 (13·6) | 69 of 409 (16·9) | 3 (7) |

| Pulmonary | 64 of 308 (20·8) | 84 of 409 (20·5) | 9 (22) |

| Cerebral | 4 of 308 (1·3) | 2 of 409 (0·5) | 0 (0) |

| Renal failure | 36 of 308 (11·7) | 48 of 409 (11·7) | 2 (5) |

| Bleeding | 7 of 308 (2·3) | 11 of 409 (2·7) | 1 (2) |

| Endoleak | 51 of 317 (16·1) | 68 of 429 (15·9) | 7 (17) |

| No. of complications | |||

| 0 | 168 of 309 (54·4) | 235 of 417 (56·4) | 24 (59) |

| 1 | 99 of 309 (32·0) | 115 of 417 (27·6) | 13 (32) |

| 2 | 23 of 309 (7·4) | 35 of 417 (8·4) | 3 (7) |

| 3 | 17 of 309 (5·5) | 31 of 417 (7·4) | 1 (2) |

| 4 | 2 of 309 (0·6) | 1 of 417 (0·2) | 0 (0) |

Values in parentheses are percentages unless indicated otherwise;

values are median (i.q.r.).

Estimated using survival methods with patients censored if they died in hospital;

excludes patients who died in theatre. LA, local anaesthesia; GA, general anaesthesia; RA, regional anaesthesia; LOS, length of hospital stay.

Sensitivity analyses were consistent with the primary analysis (Table S4, supporting information). From the Kaplan–Meier curves, the estimated mortality rate at 30 days was 39·5 per cent with GA compared with 34·0 per cent with LA. The risk with all three modes of anaesthesia (GA, LA and RA) was less than the risk of death with open repair of rAAA (Table S5, supporting information).

Almost 80 per cent of patients were admitted to ICU. The median length of stay was 2 days, and median postoperative hospital stay was 10 days in both the GA and LA groups. The complication rates were also similar in the two groups: 168 of 309 patients (54·4 per cent) in the LA group had no reported complications compared with 235 of 417 (56·4 per cent) in the GA group (Table 2).

Discussion

The main finding of this contemporary UK‐based study is that LA for endovascular repair of rAAA is associated with reduced in‐hospital mortality compared with GA.

Four RCTs4, 5, 6, 7 comparing open and endovascular repair have reported broadly comparable outcomes between the two approaches, and EVAR is now an established treatment strategy for rAAA. This has led to the emergence of rAAA repair under LA and RA that was previously not possible during open surgery. The observed benefit of LA in terms of reduced in‐hospital mortality is in line with that reported in the IMPROVE study9, which showed an adjusted fourfold reduction in 30‐day mortality among patients treated under LA: odds ratio 0·27, 95 per cent c.i. 0·10 to 0·70 (P = 0·007). A recent retrospective analysis of the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP)15 as well as the Vascular Quality Initiative (VQI)16 databases also showed a significantly reduced risk‐adjusted 30‐day mortality rate for patients who had emergency EVAR under LA compared with GA in the USA. According to these reports, the use of LA as mode of anaesthesia for emergency EVAR in the USA is less common (9·4 per cent in NSQIP and 12·2 per cent in VQI)15, 16 than in the present UK cohort, where 40·1 per cent of patients treated for rAAA with an endovascular strategy were treated under LA. UK vascular surgeons appear to have adopted the LA approach more rapidly than their colleagues in the USA. This might be a direct result of the IMPROVE trial9. The present finding of similar baseline characteristics between the LA and GA groups is in contrast to previous observational studies on elective aneurysm repair where patients undergoing elective EVAR under LA or RA tended to be older, with a higher ASA grade and a greater burden of cardiopulmonary co‐morbidity compared with patients who received GA17, 18, 19, 20, 21.

This study provides information on selection criteria and outcomes relating to the mode of anaesthesia for emergency EVAR in a real‐world setting in the UK. Some 78 per cent of vascular centres offered surgery under LA. Furthermore, the use of LA for rEVAR was not affected by the timing of the surgery; vascular units with a higher volume of aortic surgery were more likely to offer LA for rEVAR. These are important service delivery issues. The choice of anaesthesia in this registry analysis did not seem to be influenced by known patient characteristics, cardiovascular risk factors, ASA grade or aortic diameter. The reasons why vascular surgeons and anaesthetists opt for either LA or GA in specific situations are not evident, and this needs further exploration. Although the mode of anaesthesia used for emergency EVAR appears to be important, the results of the present study do not offer an explanation for the observed benefit of LA. Theories about the potential causes of poorer outcomes with GA include relaxation of tissues and release of tamponade, and the significant haemodynamic effects of GA, including loss of vascular tone, all of which may be exacerbated in patients with rAAA experiencing shock22.

Any registry is limited by the completeness and quality of its data. The NVR is externally validated against HES data in England (and equivalent routine data for Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland), and any discrepancies are raised at a central level. Case ascertainment rates continue to improve; over the 3 years from 2014 to 2016 it was 91 per cent for rAAA12. Nevertheless, the observed mortality rate was lower than might be expected for this patient group, and the potential for reporting bias remains. The NVR data collection system includes extensive checks to ensure that the values entered are valid (range checks and cross‐validation on various fields), and individual hospitals are asked to check data that appear spurious. Thus the internal validity of the registry is high. Additionally, multiple imputation methods were applied to ensure all cases were included in the analyses and not dropped owing to missing data. The NVR was established as part of the National Clinical Audit and Patient Outcomes Programme, and was not designed primarily for research10. Despite its limitations, registries such as the NVR are a vital tool to audit the safety of novel treatment approaches in rAAA and to monitor that trial outcomes are being replicated in routine practice.

Emergency EVAR can be undertaken under different modes of anaesthesia. However, there is a lack of standardization and consistency in how anaesthetic techniques are defined23. The complexity increases when sedation is used alongside LA or RA. The recording of anaesthesia in the NVR does not include whether or not sedation was used. The boundary between deep sedation and GA is fluid, and both definitions can include patients whose airway and ventilatory function might require support24. It is not known how many of the procedures in the present study cohort from the NVR were started as an LA procedure and converted to GA. This may introduce bias and is a potential weakness that was not possible to address due to the limitations of the database. In the IMPROVE trial, 16 per cent of patients treated initially under LA were converted to GA, and the outcomes of this group were similar to those of the GA group9. There are other potential confounders that this study could not address as the data were not available. For example, the level of haemodynamic instability may affect both the choice of anaesthesia and outcomes. If the proportion of more haemodynamically stable patients was higher in the LA group this would favour LA. Furthermore, centres using LA had higher case volumes than those not using LA, and there might be unknown centre‐specific characteristics such as experience of LA and secondary transfers that could influence outcome.

Mortality from emergency surgery for rAAA remains high, with variation among different healthcare systems and countries. Furthermore, the burden of morbidity is significant in survivors. Therefore, even a small reduction in perioperative mortality could have a dramatic effect. This study provides further evidence of the benefit of LA for patients undergoing emergency EVAR for rAAA.

Supporting information

Appendix S1 Data items available in the National Vascular Registry

Table S1 Use of local anaesthesia according to abdominal aortic aneurysm caseload

Table S2 Use of local anaesthesia according to timing of surgery

Table S3 Demographics and risk factors for patients undergoing open versus endovascular repair of ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm

Table S4 Comparison of in‐hospital mortality after emergency endovascular repair with local and general anaesthesia for models applying different assumptions when calculating the Hardman index

Table S5 Postoperative outcomes of patients undergoing open versus endovascular repair of ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm

Acknowledgements

The authors express their gratitude to all the vascular surgeons and patients who have contributed data to the NVR. Special thanks go to S. Waton from the Clinical Effectiveness Unit, Royal College of Surgeons of England, for conducting the data retrieval from the NVR.

This study was supported by an Infrastructure grant from the David Telling Charitable Trust, and by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre at University Hospitals Bristol NHS Foundation Trust and the University of Bristol. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the UK National Health Service, NIHR or Department of Health.

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1. Holt PJ, Karthikesalingam A, Poloniecki JD, Hinchliffe RJ, Loftus IM, Thompson MM. Propensity scored analysis of outcomes after ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm. Br J Surg 2010; 97: 496–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Karthikesalingam A, Holt PJ, Vidal‐Diez A, Ozdemir BA, Poloniecki JD, Hinchliffe RJ et al Mortality from ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms: clinical lessons from a comparison of outcomes in England and the USA. Lancet 2014; 383: 963–969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lachat ML, Pfammatter T, Witzke HJ, Bettex D, Künzli A, Wolfensberger U et al Endovascular repair with bifurcated stent‐grafts under local anaesthesia to improve outcome of ruptured aortoiliac aneurysms. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2002; 23: 528–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hinchliffe RJ, Bruijstens L, MacSweeney ST, Braithwaite BD. A randomised trial of endovascular and open surgery for ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm – results of a pilot study and lessons learned for future studies. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2006; 32: 506–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Desgranges P, Kobeiter H, Katsahian S, Bouffi M, Gouny P, Favre JP et al; ECAR Investigators. Editor's choice – ECAR (Endovasculaire ou Chirurgie dans les Anévrysmes aorto‐iliaques Rompus): a French randomized controlled trial of endovascular versus open surgical repair of ruptured aorto‐iliac aneurysms. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2015; 50: 303–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Reimerink JJ, Hoornweg LL, Vahl AC, Wisselink W, van den Broek TA, Legemate DA et al; Amsterdam Acute Aneurysm Trial Collaborators. Endovascular repair versus open repair of ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg 2013; 258: 248–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. IMPROVE Trial Investigators . Endovascular strategy or open repair for ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm: one‐year outcomes from the IMPROVE randomized trial. Eur Heart J 2015; 36: 2061–2069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sweeting MJ, Balm R, Desgranges P, Ulug P, Powell JT; Ruptured Aneurysm Trialists . Individual‐patient meta‐analysis of three randomized trials comparing endovascular versus open repair for ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm. Br J Surg 2015; 102: 1229–1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. IMPROVE Trial Investigators , Powell JT, Hinchliffe RJ, Thompson MM, Sweeting MJ, Ashleigh R et al Observations from the IMPROVE trial concerning the clinical care of patients with ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm. Br J Surg 2014; 101: 216–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vascular Society of Great Britain and Ireland. Vascular Services Quality Improvement Programme; 2017. www.vsqip.org.uk [accessed 28 October 2018].

- 11.Office for National Statistics. The 21st Century Mortality Files – Deaths Dataset, England and Wales; 2015. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/datasets/the21stcenturymortalityfilesdeathsdataset [accessed 28 October 2017].

- 12. Waton S, Johal A, Heikkila K, Cromwell D, Boyle J, Loftus I. National Vascular Registry: 2017 Annual Report. Royal College of Surgeons of England: London, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hardman DT, Fisher CM, Patel MI, Neale M, Chambers J, Lane R et al Ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms: who should be offered surgery? J Vasc Surg 1996; 23: 123–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rubin DB. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. John Wiley: New York, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 15. El‐Hag S, Shafii S, Rosenberg M, Weinhandl ED, Loor G, Aplin B et al Local anesthesia‐based endovascular repair of ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm is associated with lower 30‐day mortality in the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program database. J Vasc Surg 2016; 63(Suppl): 173S–174S. [Google Scholar]

- 16. El‐Hag S, Shafii S, Rosenberg M, Loor G, Weinhandl ED, Mewissen M et al Decreased mortality with local vs general anesthesia in EVAR for ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm in the Vascular Quality Initiative database. J Vasc Surg 2016; 63(Suppl): 147S–148S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ruppert V, Leurs LJ, Steckmeier B, Buth J, Umscheid T. Influence of anesthesia type on outcome after endovascular aortic aneurysm repair: an analysis based on EUROSTAR data. J Vasc Surg 2006; 44: 16–21.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Verhoeven EL, Cinà CS, Tielliu IF, Zeebregts CJ, Prins TR, Eindhoven GB et al Local anesthesia for endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg 2005; 42: 402–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Geisbüsch P, Katzen BT, Machado R, Benenati JF, Pena C, Tsoukas AI. Local anaesthesia for endovascular repair of infrarenal aortic aneurysms. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2011; 42: 467–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Edwards MS, Andrews JS, Edwards AF, Ghanami RJ, Corriere MA, Goodney PP et al Results of endovascular aortic aneurysm repair with general, regional, and local/monitored anesthesia care in the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program database. J Vasc Surg 2011; 54: 1273–1282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Karthikesalingam A, Thrumurthy SG, Young EL, Hinchliffe RJ, Holt PJ, Thompson MM. Locoregional anesthesia for endovascular aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg 2012; 56: 510–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hope K, Nickols G, Mouton R. Modern anesthetic management of ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2016; 30: 1676–1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Armstrong RA, Mouton R. Definitions of anaesthetic technique and the implications for clinical research. Anaesthesia 2018; 73: 935–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.American Society of Anesthesiologists. Continuum of Depth of Sedation: Definition of General Anesthesia and Levels of Sedation/Analgesia; 2014. http://www.asahq.org/quality‐and‐practice‐management/standards‐guidelines‐and‐related‐resources/continuum‐of‐depth‐of‐sedation‐definition‐of‐general‐anesthesia‐and‐levels‐of‐sedation‐analgesia [accessed 3 September 2017].

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1 Data items available in the National Vascular Registry

Table S1 Use of local anaesthesia according to abdominal aortic aneurysm caseload

Table S2 Use of local anaesthesia according to timing of surgery

Table S3 Demographics and risk factors for patients undergoing open versus endovascular repair of ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm

Table S4 Comparison of in‐hospital mortality after emergency endovascular repair with local and general anaesthesia for models applying different assumptions when calculating the Hardman index

Table S5 Postoperative outcomes of patients undergoing open versus endovascular repair of ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm