Abstract

Aims

We tested the age‐varying associations of cannabis use (CU) frequency and disorder (CUD) with psychotic, depressive and anxiety symptoms in adolescent and adult samples. Moderating effects of early onset (≤ 15 years) and sex were tested.

Design

Time‐varying effect models were used to assess the significance of concurrent associations between CU and CUD and symptoms of psychosis, depression and anxiety at each age.

Setting and Participants

Adolescent data (V‐HYS; n = 662) were collected from a randomly recruited sample of adolescents in Victoria, British Columbia, Canada during a 10‐year period (2003–13). Adult cross‐sectional data (NESARC‐III; n = 36 309) were collected from a representative sample from the United States (2012–13).

Measurements

Mental health symptoms were assessed using self‐report measures of diagnostic symptoms. CU was based on frequency of past‐year use. Past‐year CUD was based on DSM‐5 criteria.

Findings

For youth in the V‐HYS, CU was associated with psychotic symptoms following age 22 [b = 0.13, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 0.002, 0.25], with depressive symptoms from ages 16–19 and following age 25 (b = 0.17, 95% CI = 0.003, 0.34), but not with anxiety symptoms. CUD was associated with psychotic symptoms following age 23 (b = 0.51, 95% CI = 0.01, 1.01), depressive symptoms at ages 19–20 and following age 25 (b = 0.71, 95% CI = 0.001, 1.42) and anxiety symptoms ages 26–27 only. For adults in the NESARC‐III, CU was associated with mental health symptoms at most ages [e.g. psychotic symptoms; age 18 (b = 0.22, 95% CI = 0.10, 0.33) to age 65 (b = 0.36, 95% CI = 0.16, 0.56)]. CUD was associated with all mental health symptoms across most ages [e.g. depressive symptoms; age 18 (b = 0.96, 95% CI = 0.19, 1.73) to age 61 (b = 1.11, 95% CI = 0.01, 2.21)]. Interactions with sex show stronger associations for females than males in young adulthood [e.g. V‐HYS: CUD × sex interaction on psychotic symptoms significant after age 26 (b = 1.12, 95% CI = 0.02, 2.21)]. Findings were not moderated by early‐onset CU.

Conclusions

Significant associations between cannabis use (CU) frequency and disorder (CUD) and psychotic and depressive symptoms in late adolescence and young adulthood extend across adulthood, and include anxiety.

Keywords: Adolescence, anxiety, cannabis use, cannabis use disorder, depression, early onset, marijuana, mental health, psychosis, young adulthood

Introduction

Both substance use and mental health disorders contribute substantially to the global burden of disease 1, 2. With legalization of cannabis use (CU) in Canada and many states in the United States, there is considerable interest in how CU affects or is affected by mental health concerns. Recent reviews and meta‐analyses of research show that CU is consistently associated with the onset and severity of psychotic symptoms 3, 4, 5, 6. Research also suggests that CU may have modest effects on mood and anxiety, although findings are inconsistent 4, 5, 7. These inconsistencies relate to differences in age groups sampled, cultural differences in illegality of CU and differences in symptoms assessed. It is also possible that associations between cannabis and mental health indicators are non‐linear, given that experiences of psychotic and mood disorders may be episodic. In addition, concentrations of delta‐9‐tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), age of onset, frequency, duration of use and a host of co‐occurring risks are also related to both acute effects of cannabis and mental health symptoms 4, 5. As a result, the influences of CU and cannabis use disorder (CUD) on mental health have proved difficult to unravel.

Particular concern focuses on CU in adolescents. Several recent reviews suggest that adolescent onset of CU (i.e. 15 years or younger) conveys age‐specific risks for concurrent and adult‐onset mental health disorders 3, 4, 5. Theory relates this age‐sensitivity to ongoing brain maturation and greater reward‐sensitivity and reward‐seeking in adolescence and considerable epidemiological, animal and neuropsychological research shows some support for heightened risks related to adolescent onset of CU (see reviews by 4, 5). However, comparisons with adult samples are lacking and findings differ by symptom type 8, 9. One longitudinal study of Swedish adults aged 20–64 with a 3‐year follow‐up 10 found that CU at baseline was associated with risk for depression and anxiety (as well as the reverse); however, these associations were not significant beyond co‐occurring risks (e.g. alcohol and illicit drug use, education, family tension, place of upbringing) and age of onset of use was not examined.

However, in addition to sensitivities related to brain maturation 11, there are several reasons why adolescents may show stronger associations between CU and mental health symptoms than older adults. First, Winters & Lee 12 showed that risks for CU dependency were greater in recent‐onset users at ages 14–18 than at ages 22–26, although Chen et al. 13 found that adolescents may over‐report the clinical markers of CUD (e.g. used more than intended, spent significant time in activities to obtain cannabis or disrupted family or work relationships). Secondly, more frequent or longer‐term use (also characteristic of older users) may lower sensitivity to the negative acute effects of THC as tolerance increases 14, 15, suggesting that adults could have lower associations between CU and CUD and mental health symptoms. Thirdly, some research also finds that associations between CU and symptoms are not significant after controlling for common liabilities or co‐occurring risks (e.g. alcohol and illicit drug use, education, family tension, place of upbringing, abuse and victimization). Such risks may also be particularly likely to contribute to allostatic load, stress and mental health symptoms in adolescence 11. Fourthly, many mental health disorders onset in adolescence and this temporal co‐occurrence may contribute to the strength of their associations with CU and CUD in adolescence. For example, almost 50% of life‐time cases of any mental health disorder start by age 14 and 75% start by age 24 16, 17. However, Kessler et al. 16 also found marked differences in mean ages of onset of anxiety disorders (11 years), substance use (20 years) and mood disorders (30 years), and the onset of psychotic episodes was rare before 12 or after 30 years, suggesting that correlations may differ by symptom type. The strength of associations between psychiatric diagnoses and CU and CUD may increase from adolescence to young adulthood as new cases increase, and then level off as new cases become less likely. Finally, associations could be stronger in individuals with an early age of onset of CU given longer timing of exposure, or the hypothesized effects on adolescents’ brain development, particularly if use is sustained across adolescence and young adulthood 5. CU and mental health symptoms differ for males and females in adolescence and adulthood 18, 19, 20 and some research shows associations between CU and mental health symptoms for females 21, while others show associations for males 22, warranting further investigation of sex differences in associations.

This study has three aims:

To assess changes in strength of the associations between CU and CUD and symptoms of psychosis, depression and anxiety at each age in an adolescent and adult sample;

To examine differences in these associations for early (versus late) adolescent CU onset; and

To examine sex differences in these associations.

Method

Design

Using time‐varying effects models (described below), adjusted for socio‐economic status (SES), cigarette smoking and heavy episodic drinking (HED), we examine the strength of the associations of CU frequency and CUD with mental health symptoms in two samples: (1) a community sample of Canadian adolescents, the Victoria Healthy Youth Survey (V‐HYS 23) followed prospectively (2003–13) and (2) a nationally representative of adults (ages 18+) from the (2012–13) US National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol And Related Conditions (NESARC‐III 25). Interactions of these associations with early onset of cannabis use (i.e. age 15 and younger versus after age 15) and sex are also assessed. Use of the two samples allows us to identify age‐specific associations between CU and CUD and mental health symptoms from adolescence to older adulthood (e.g. ages 15–65).

Samples

Victoria healthy youth survey

The V‐HYS 23 included 662 Canadian youth assessed biannually across six waves (Table 1). Random digit‐dialing of 9500 telephone listings revealed 1036 households with a youth aged 12–18; 662 youth both had parental consent and agreed to participate. Youth received gift certificates at each interview. Trained interviewers administered surveys and sections dealing with sensitive topics (e.g. substance use) were collected via self‐reported questionnaires to enhance confidentiality. Retention rates at each wave were good (87–72%). Fifty‐three per cent of youth (n = 350) participated in all waves, 16% (n = 107) in five waves, 10% (n = 63) in four, 8% (n = 55) in three, 6% (n = 40) in two and 7% (n = 47) in only one wave. Youth remaining at the sixth wave were more likely to be female, χ2 (1, 662) = 8.77, P = 0.003, had higher SES, F (1, 655) = 14.90, P < 0.001 and were less likely to be smokers (F (1, 660) = 3.82, P = 0.05.

Table 1.

Demographic and study variable characteristics of the V‐HYS (T1 n = 662).

| Mean (SD) or n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Demographics (time 1) | |

| Sex (% female) | 342 (52%) |

| Age | 15.52 (1.92) |

| SESa | 2.88 (1.38) |

| Ethnicity (% white) | 561 (85%) |

| Time 1 | |

| Covariates | |

| Cigarette use | 75 (11%) |

| Heavy episodic drinking (HED) | 0.60 (1.00) |

| Predictors | |

| Cannabis use (CU) frequency (average) | 0.73 (1.21) |

| Never | 426 (64%) |

| A few times a year | 109 (17%) |

| A few times per month | 60 (9%) |

| Once a week | 15 (2%) |

| More than once a week | 52 (8%) |

| Cannabis use disorder (CUD) | –b |

| Outcomes | |

| Psychotic symptoms | –c |

| Depressive symptoms | 2.79 (2.53) |

| Anxiety symptoms | 5.81 (2.58) |

| Time 2 | |

| Covariates | |

| Cigarette use | 107 (19%) |

| Heavy episodic drinking (HED) | 1.14 (1.24) |

| Predictors | |

| Cannabis use (CU) frequency (average) | 1.17 (1.45) |

| Never | 277 (48%) |

| A few times a year | 113 (20%) |

| A few times per month | 74 (13%) |

| Once a week | 22 (4%) |

| More than once a week | 86 (15%) |

| Cannabis use disorder (CUD) | –b |

| Outcomes | |

| Psychotic symptoms | –c |

| Depressive symptoms | 3.19 (2.57) |

| Anxiety symptoms | 6.24 (2.62) |

| Time 3 | |

| Covariates | |

| Cigarette use | 131 (25%) |

| Heavy episodic drinking (HED) | 1.55 (1.29) |

| Predictors | |

| Cannabis use (CU) frequency (average) | 1.45 (1.54) |

| Never | 207 (39%) |

| A few times a year | 128 (24%) |

| A few times per month | 54 (10%) |

| Once a week | 38 (7%) |

| More than once a week | 105 (20%) |

| Cannabis use disorder (CUD) | –b |

| Outcomes | |

| Psychotic symptoms | 3.34 (2.54) |

| Depressive symptoms | 3.60 (2.66) |

| Anxiety symptoms | 6.26 (2.51) |

| Time 4 | |

| Covariates | |

| Cigarette use | 123 (27%) |

| Heavy episodic drinking (HED) | 1.62 (1.28) |

| Predictors | |

| Cannabis use (CU) frequency (average) | 1.40 (1.56) |

| Never | 191 (42%) |

| A few times a year | 97 (22%) |

| A few times per month | 48 (11%) |

| Once a week | 20 (4%) |

| More than once a week | 95 (21%) |

| Cannabis use disorder (CUD) | 116 (26%) |

| Outcomes | |

| Psychotic symptoms | 2.69 (2.37) |

| Depressive symptoms | 3.07 (2.62) |

| Anxiety symptoms | 5.98 (2.63) |

| Time 5 | |

| Covariates | |

| Cigarette use | 127 (28%) |

| Heavy episodic drinking (HED) | 1.52 (1.21) |

| Predictors | |

| Cannabis use (CU) frequency (average) | 1.21 (1.46) |

| Never | 206 (46%) |

| A few times a year | 113 (25%) |

| A few times per month | 39 (9%) |

| Once a week | 24 (5%) |

| More than once a week | 71 (16%) |

| Cannabis use disorder (CUD) | 79 (17%) |

| Outcomes | |

| Psychotic symptoms | 2.41 (2.27) |

| Depressive symptoms | 2.88 (2.58) |

| Anxiety symptoms | 5.61 (2.67) |

| Time 6 | |

| Covariates | |

| Cigarette use | 106 (22%) |

| Heavy episodic drinking (HED) | 1.44 (1.21) |

| Predictors | |

| Cannabis use (CU) frequency (average) | 1.22 (1.47) |

| Never | 214 (45%) |

| A few times a year | 116 (25%) |

| A few times per month | 41 (9%) |

| Once a week | 24 (5%) |

| More than once a week | 77 (16%) |

| Cannabis use disorder (CUD) | 73 (16%) |

| Outcomes | |

| Psychotic symptoms | 2.24 (2.34) |

| Depressive symptoms | 2.88 (2.65) |

| Anxiety symptoms | 5.44 (2.78) |

Socio‐economic status (SES) was assessed by mother's level of education (0 = did not finish high school to 4 = finished college/university) in the Victoria Healthy Youth Survey (V‐HYS). SD = standard deviation.

CUD was not assessed until T4 (2009) in the V‐HYS.

Psychotic symptoms were not assessed until T3 (2007) in the V‐HYS.

NSARC‐III

The NESARC‐III (2012–13 25) is a nationally representative sample of 36 309 non‐institutionalized US adults aged 18 and older (Table 2). NESARC‐III were sampled from non‐institutionalized civilian populations aged 18 and older, including residents of group quarters (e.g. group homes, dormitories; see 25 for more detailed information regarding data collection procedures). Black, Hispanic and Asian adults were oversampled to provide more reliable estimates; thus, survey weights were incorporated in all analyses. Structured interviews were conducted face‐to‐face. Participants received $90 in compensation.

Table 2.

Demographic and study variable characteristics of the NESARC‐III (n = 30 999).

| Mean (SD) or n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Demographics | |

| Sex (% female) | 17 283 (51%) |

| Age | 40.61 (13.41) |

| SESa | 7.25 (4.64) |

| Ethnicity (% non‐Hispanic white) | 15 392 (64%) |

| Covariates | |

| Cigarette use | 9350 (30%) |

| Heavy episodic drinking (HED) | 11 196 (37%) |

| Predictors | |

| Cannabis use (CU) frequency (average) | 0.31 (0.95) |

| Never | 27 360 (89%) |

| A few times a year | 1092 (4%) |

| A few times per month | 656 (2%) |

| Once a week | 370 (1%) |

| More than once a week | 1510 (4%) |

| Cannabis use disorder (CUD) | 965 (3%) |

| Outcomes | |

| Psychotic symptoms | 1.12 (1.66) |

| Depressive symptoms | 2.00 (3.01) |

| Anxiety symptoms | 0.78 (1.81) |

Socio‐economic status (SES) was assessed by participant income (0 = $0 to 17 = $100 000 or more) in the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol And Related Conditions (NESARC)‐III. SD = standard deviation.

Measures

Table 3 provides the items, references and alphas, where appropriate, for each construct from the V‐HYS and NESARC‐III surveys. Measures were nearly identical across data sets and had good psychometric properties.

Table 3.

Comparability of items from the V‐HYS and NESARC‐III data sets.

| Victoria Healthy Youth Survey (V‐HYS) | National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol And Related Conditions (NESARC‐III) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | Item descriptions | Notes | Measure | Item descriptions | Notes |

| Cannabis use frequency | |||||

| • How often did you use marijuana in the past 12 months? |

• 1 item • 0 (never) to 4 (more than once a week) |

• How often used marijuana in the past 12 months? |

• 1 item • 0 (never) to 4 (more than once a week) |

||

| Cannabis use disorder | |||||

| • Mini‐International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI; 26) |

• Needed to use more to get the same effect • Experience withdrawal symptoms • Taking more than anticipated • Inability to reduce use or stop • Significant time spent in activities to obtain, use or recover from cannabis • Spend less time working, enjoying hobbies, or being with family or friends due to use • Continued use despite health or mental problems • High or intoxicated when had other responsibilities at school, work, or at home • High or intoxicated in any situation where physically at risk • Continued use despite interpersonal problems |

• 9 items • 0 (no) or 1 (yes) • ≥ 2 endorsed criteria (i.e. symptoms) = cannabis use disorder 24 |

• Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM‐5) criteria for past‐year cannabis use disorder 24 |

• Needed increased amounts to achieve desired effect or diminished effect with continued use of same amount • Experience withdrawal symptoms • Taken in larger amounts or longer than intended • Unsuccessful efforts to cut down or control use • Significant time spent in activities to obtain, use or recover from cannabis • Reduced social, occupational or recreational activities due to use • Continued use despite physical or psychological problem • Failure to fulfill major life role obligations (e.g. work, school or home) • Use when in situations that are physically hazardous • Continued use despite persistent or recurrent social or interpersonal problems • Strong urge or desire to use (craving) |

• 0 (no) or 1 (yes) • ≥ 2 endorsed criteria (i.e. symptoms) = past‐year cannabis use disorder 24 |

| Psychotic symptoms | |||||

| • Symptoms Checklist 90‐Revised (SCL‐90‐R; 27) |

• Someone else can control your thoughts • Others are to blame for your troubles • Hearing voices • Other people being aware of your thoughts • Feeling that you are watched or talked about • Having thoughts that are not your own • Have ideas or beliefs that others do not share • Think something serious is wrong with your body • Never feeling close to another person • Belief something is wrong with your mind |

• 10 items • 0 (no) or 1 (yes) • Range: 0–10 • α = 0.75–0.82 |

• Items tapping unusual feelings and actions (NESARC‐III; 25) |

• Things that have no special meaning are really meant to give you a message • Difficulty trusting others • Think objects or shadows are really people or animals, or that noises are actually people's voices • Felt that you are being watched/stared at • Possess a ‘sixth sense’ that allows you to know and predict things • Strange ideas • Felt outside your body when under stress • Have few people that you're really close to • People have thought you have strange ideas |

• 9 items • 0 (no) or 1 (yes) • Range: 0–9 • α = 0.76 |

| Depressive symptoms | |||||

| • Brief Child and Family Phone Interview (BCFPI; 28) |

• Feel hopeless? • Get no pleasure from your usual activities? • Have trouble enjoying yourself? • Have no interest in your usual activities? • Are unhappy, sad, or depressed? • Are not as happy as people your age? |

• 6 items • 0 (never) to 2 (often) • Range: 0–12 • α = 0.80–0.86 |

• DSM‐5 criteria for major depressive episode 24 |

• Feeling sad, hopeless, depressed or down? • You didn't care about things? • Weight loss/gain or changes in appetite (4 items) • Insomnia or hypersomnia (3 items) • Psychomotor agitation or retardation (6 items) • Fatigue or loss of energy (2 items) • Feelings of worthlessness or excessive guilt (3 items) • Diminished ability to concentrate (4 items) • Suicidal ideation, attempt or plan (4 items) |

• 9 criteriaa,b

• 0 (no) or 1 (yes) • Range: 0–9 • α = 0.93 |

| Anxiety symptoms | |||||

| • Brief Child and Family Phone Interview (BCFPI; 28) |

• Worry about your past behavior? • Worry about doing the wrong thing? • Worry about doing better at things? • Are overly anxious to please people? • Are afraid of making mistakes? • Worry about things in the future? |

• 6 items • 0 (never) to 2 (often) • Range: 0–12 • α = 0.75–0.82 |

• DSM‐5 criteria for generalized anxiety disorder 24 |

• Feeling restless or keyed up (2 items) • Fatigue (1 item) • Difficulty concentrating or mind going blank (2 items) • Irritability (1 item) • Muscle tension or aches (1 item) • Sleep disturbances (2 items) |

• 6 criteriaa,b

• 0 (no) or 1 (yes) • Range: 0–6 • α = 0.95 |

Descriptions of items are provided. Please refer to the original reference or NESARC‐III codebooks 25 for exact item wording.

Participants were first asked if they had ever experienced a 2‐week period of depressive symptoms (e.g. felt sad, hopeless, depressed or down nearly every day) when assessing depression and a 3‐month period of excessive worry or anxiety when assessing anxiety. If yes, participants responded to items in reference to their worst period of worry or anxiety. For both depression and anxiety, if participants did not report ‘yes’ to the screening question(s), they were categorized as never or unknown if ever had a period of low mood/when they did not care (across all depression and anxiety screening questions; 0.2–0.5% were unknown).

When more than one item tapped a specific criterion (e.g. three items for insomnia or hypersomnia criteria), a participant was given a score of 1 if any of the items were endorsed.

Covariates

Participants self‐reported sex. SES was assessed using mother's education (0 = did not finish high school to 4 = finished college/university) in the V‐HYS and participant income (0 = $0–17 = $100 000 or more) in the NESARC‐III. Cigarette use was dichotomized into non‐smoker (0) and current smoker (1). In the V‐HYS, HED was assessed based on reported frequency of past‐year HED 5+ drinks; 0 = never to 4 = more than once per week); in the NESARC‐III, sex‐specific standards were used (4+/5+ drinks for women/men).

Predictors

CU frequency assessed past‐year use (0 = never to 4 = more than once per week). CUD was assessed using the Mini‐International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI 26) in the V‐HYS. However, both samples used DSM‐5 24 criteria for past‐year CUD diagnosis (Table 3).

Outcomes

Psychotic symptoms were assessed using the Symptoms Checklist 90‐Revised (SCL‐90 27) in the V‐HYS (10 items) and using nine items tapping unusual feelings and actions in the NESARC‐III 25. In the V‐HYS, depressive and anxiety symptoms (six items each) were assessed using the Brief Child and Family Phone Interview (BCFPI 28). In the NESARC‐III, DSM‐5 24 criteria were used to assess depressive (nine items) and anxiety (six items) symptoms.

Analyses

Data from the V‐HYS and NESARC‐III were restructured so that the time metric was age in years. In the V‐HYS, data for ages 12–14 were not included due to low frequency of CU and observations for age 29 (n = 39) were not included due to low covariance coverage 29. CUD was only collected from T4 (2009; ages 18–25) onwards, so data for age 18 (n = 10) also had low covariance coverage. In the NESARC‐III, individuals older than age 65 were not included due to low frequency of CU, resulting in an analytical sample of 30 999. The total number of observations at each age ranged from 76 to 273 at ages 15–28 for the V‐HYS and from 418 to 778 at ages 18–65 in the NESARC‐III.

For each sample, the %TVEM macro in SAS version 9.3 30 was used to model associations between (1) CU frequency and (2) CUD and each of the three mental health outcomes (i.e. psychotic, depressive, anxiety symptoms). TVEM flexibly estimates linear regressions as a function of age, using all available data for each participant; time‐specific observations with missing values are excluded from the model at that specific time‐point 31. Given that our mental health outcomes are continuous, we used the %TVEM‐normal macro with P‐splines which assumes outcomes are normally distributed. This type of modeling automatically adjusts for within‐person correlations due to repeated‐measurement design 31. We controlled for sex, SES, cigarette use and HED in all models. The time‐varying interactions are used to estimate whether CU or CUD had different associations with mental health symptoms for individuals with early‐ versus late‐onset use and for males and females. Results are presented in figures, as time‐varying coefficients are estimated in continuous time (age), leading to too many coefficients to present in the tables. As the dependent variables (i.e. mental health symptoms) are continuous measures, the y‐axis shows the main effect (b coefficient) of CU or CUD on symptom levels at each age. When the 95% confidence interval (CI) for the main effect (or interaction) does not include 0, the significance of the estimate falls below P = 0.05 30.

Results

V‐HYS findings

Changes across age

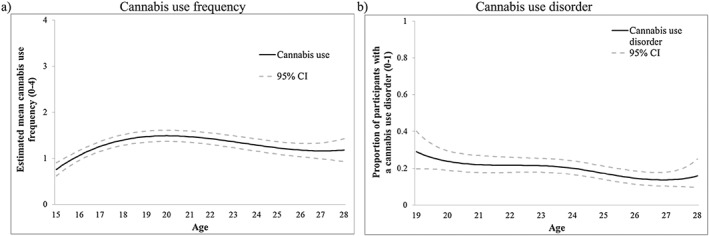

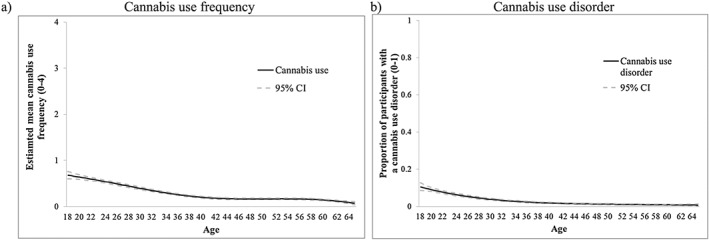

Figure 1 presents the models showing how CU frequency or the proportion of participants with a CUD varies across age. The y‐axis presents the estimated mean of past year CU frequency (Fig. 1a). CU increased until approximately 20 years (e.g. estimated mean at age 20 = 1.49, 95% CI = 1.36, 1.61) then began to gradually decline. In Fig. 1b, the y‐axis presents the prevalence of CUD which declined across age. Psychotic symptoms were reported at the highest levels in adolescence and declined steadily across age. Depressive and anxiety symptoms increased slightly until approximately 18 years and were then stable (Supporting information, Fig. S1).

Figure 1.

Victoria Healthy Youth Survey (V‐HYS) data: intercept‐only models for (a) cannabis use frequency (solid line represents estimated mean frequency) and (b) cannabis use disorder (solid line represents proportion of individuals with a past year cannabis use disorder). CI = confidence interval

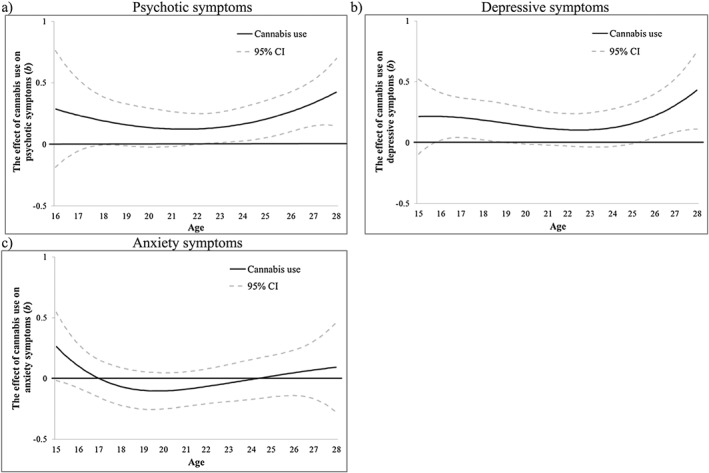

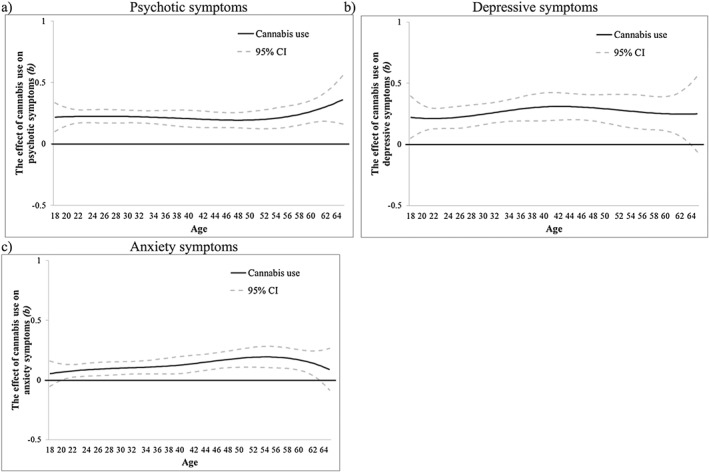

CU frequency and mental health symptoms

More frequent CU was positively significantly associated (main effect CI > 0) with psychotic symptoms after age 22 (b = 0.13, 95% CI = 0.002, 0.25) (Fig. 2a). Figure 2b shows that CU was significantly associated with more depressive symptoms from ages 16–19 (e.g. age 17: b = 0.21, 95% CI = 0.04, 0.37) and following age 25 (b = 0.17, 95% CI = 0.003, 0.34). CU was not associated with anxiety symptoms in this sample (Fig. 2c). Time‐varying interactions of CU with age of onset (Supporting information, Fig. S2) and sex (Supporting information, Fig. S3) were not significant.

Figure 2.

Victoria Healthy Youth Survey (V‐HYS) data: the time‐varying main effect (b) of cannabis use frequency on (a) psychotic, (b) depressive and (c) anxiety symptoms. Models are adjusted for sex, socio‐economic status (SES), cigarette use and heavy drinking. Results are presented as regression coefficients (b); 95% confidence interval (CI) (dashed lines) that do not include 0 indicate periods of significance

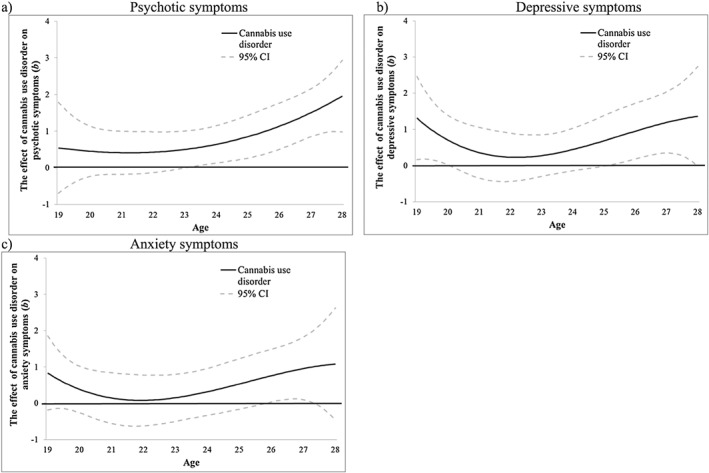

CUD and mental health symptoms

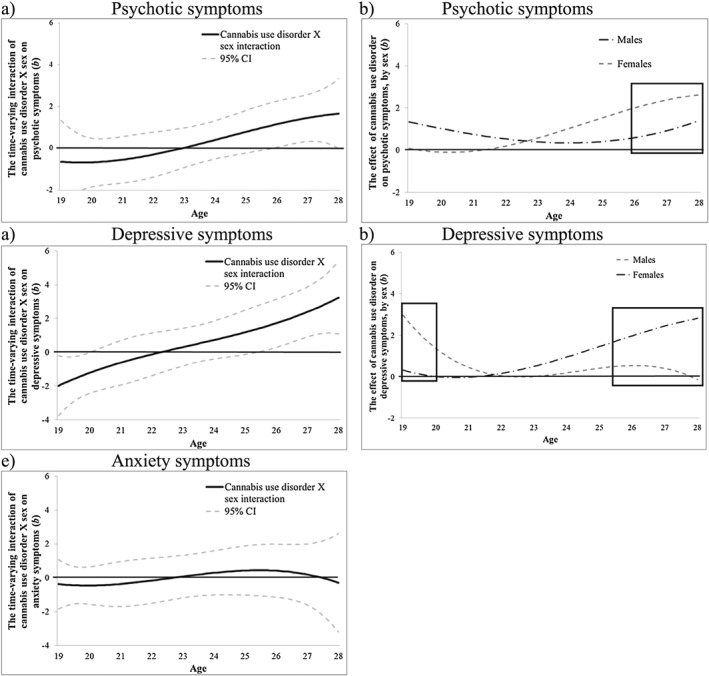

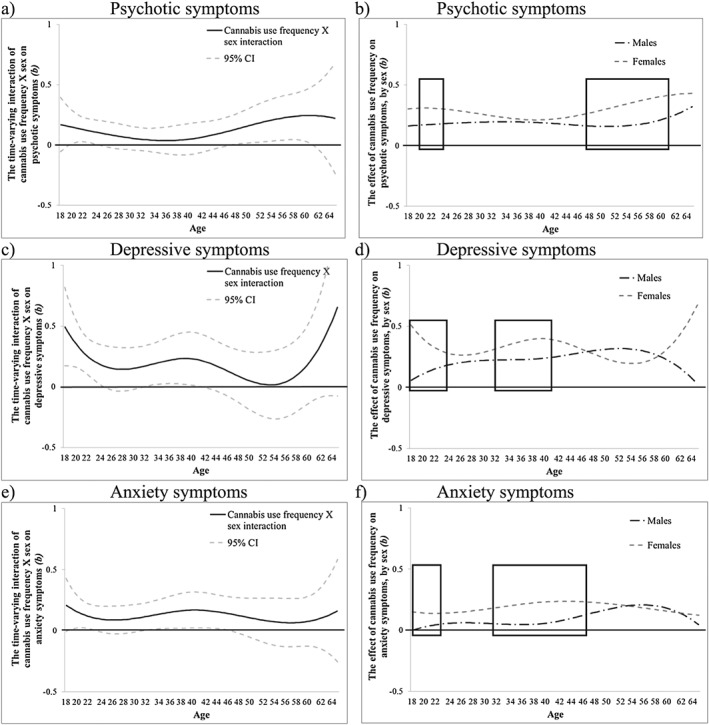

CUD was associated with psychotic symptoms after age 23 (b = 0.51, 95% CI = 0.01, 1.01) (Fig. 3a). CUD was also associated with higher depressive symptoms at ages 19–20 (e.g. age 20: b = 0.70, 95% CI = 0.02, 1.39) and following age 25 (b = 0.71, 95% CI = 0.001, 1.42) (Fig. 3b) and with higher anxiety symptoms at ages 26–27 only (e.g. age 27: b = 0.96, 95% CI = 0.10, 1.82) (Fig. 3c). Time‐varying interactions with age of onset were not significant (Supporting information, Fig. S4). However, sex differences were significant for associations between CUD and psychotic and depressive symptoms. For psychotic symptoms, the interaction was significant following age 26 (b = 1.12, 95% CI = 0.02, 2.21) (Fig. 4a), when females showed stronger associations than males (Fig. 4b). For depressive symptoms, the interaction was significant at 19–20 (e.g. age 20: b = −1.22, 95% CI = 0−2.42, −0.01) (Fig. 4c), when males showed stronger associations than females (Fig. 4d), and following age 25 (e.g. age 27: b = 2.39, 95% CI = 0.91, 3.87), when females showed stronger associations than males (Fig. 4d). Sex did not moderate the association between CUD and anxiety symptoms (Fig. 4e).

Figure 3.

Victoria Healthy Youth Survey (V‐HYS) data: the time‐varying main effect (b) of cannabis use disorder on (a) psychotic, (b) depressive and (c) anxiety. Models are adjusted for sex, socio‐economic status (SES), cigarette use and heavy drinking. Results are presented as regression coefficients (b); 95% confidence interval (CI) (dashed lines) that do not include 0 indicate periods of significance

Figure 4.

Victoria Healthy Youth Survey (V‐HYS): the time‐varying interaction (b) of cannabis use disorder by sex on psychotic (a,b), depressive (c,d) and anxiety (e; non‐significant) symptoms. The time‐varying interaction is plotted on the left. The sex difference in the main effect is plotted on the right; the area inside the box represents the approximate ages when the sex interaction is significant (P < 0.05). Models are adjusted for socio‐economic status (SES), cigarette use and heavy drinking. b = regression coefficient; CI = confidence intervals

NESARC‐III findings

Changes across age

Figure 5 presents the intercept‐only models for the NESARC‐III CU data. Frequency of CU and prevalence of CUD declined from ages 18 to 40 and then were stable (Fig. 5a,b, respectively). Mental health symptoms were relatively stable over time (Supporting information, Fig. S5).

Figure 5.

National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC)‐III data: intercept‐only models for (a) cannabis use frequency (solid line represents estimated mean frequency) and (b) cannabis use disorder (solid line represents proportion of individuals with a past year cannabis use disorder). CI = confidence interval

CU frequency and mental health symptoms

More frequent CU had a significant and stable association with more psychotic symptoms from age 18 (b = 0.21, 95% CI = 0.10, 0.33) to age 65 (b = 0.36, 95% CI = 0.16, 0.56) (Fig. 6a). Frequent CU was positively associated with depressive symptoms from age 18 (b = 0.22, 95% CI = 0.05, 0.40) to age 64 (b = 0.25, 95% CI = 0.01, 0.48) (Fig. 6b). CU was also positively associated with anxiety symptoms from age 20 (b = 0.07, 95% CI = 0.01, 0.13) to age 63 (b = 0.13, 95% CI = 0.01, 0.25) (Fig. 6c). Time‐varying interactions of CU with early age of onset were not significant beyond chance (Supporting information, Fig. S6). Time‐varying interactions of CU with sex were significant for psychotic symptoms between ages 20 (b = 0.15, 95% CI = 0.01, 0.29) to age 24 (b = 0.11, 95% CI = 0.01, 0.21) and between ages 47 (b = 0.12, 95% CI = 0.003, 0.25) to age 61 (b = 0.24, 95% CI = 0.01, 0.47), for depressive symptoms between ages 18 (b = 0.50, 95% CI = 0.17, 0.82) to age 25 (b = 0.17, 95% CI = 0.001, 0.34) and between ages 32 (b = 0.17, 95% CI = 0.01, 0.34) to age 41 (b = 0.22, 95% CI = 0.001, 0.44) and for anxiety symptoms between ages 18 (b = 0.19, 95% CI = 0.003, 0.39) to age 23 (b = 0.11, 95% CI = 0.01, 0.21) and ages 32 (b = 0.11, 95% CI = 0.001, 0.23) to age 46 (b = 0.14, 95% CI = 0.003, 0.28) (Fig. 7a,c,e). During these periods, females showed stronger associations between CU frequency and symptoms than males (Fig. 7b,d,f).

Figure 6.

National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC)‐III data: the time‐varying main effect (b) of cannabis use frequency on (a) psychotic, (b) depressive and (c) anxiety symptoms. Models are adjusted for sex, socio‐economic status (SES), cigarette use and heavy drinking. Results are presented as regression coefficients (b); 95% confidence interval (CI) (dashed lines) that do not include 0 indicate periods of significance

Figure 7.

National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC)‐III data: the time‐varying interaction (b) of cannabis use frequency by sex on psychotic (a,b), depressive (c,d) and anxiety (e,f) symptoms. The time‐varying interaction is plotted on the left. The sex difference in the main effect is plotted on the right; the area inside the box represents the approximate ages when the sex interaction is significant (P < 0.05). Models are adjusted for socio‐economic status (SES), cigarette use and heavy drinking. b = regression coefficient; CI = confidence intervals

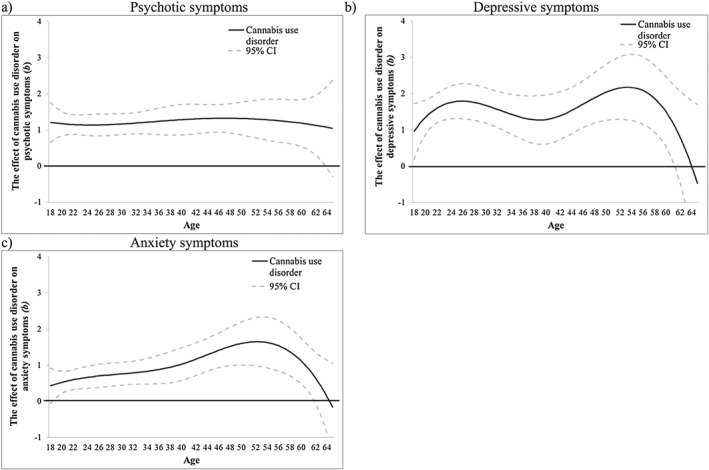

CU disorder and mental health symptoms

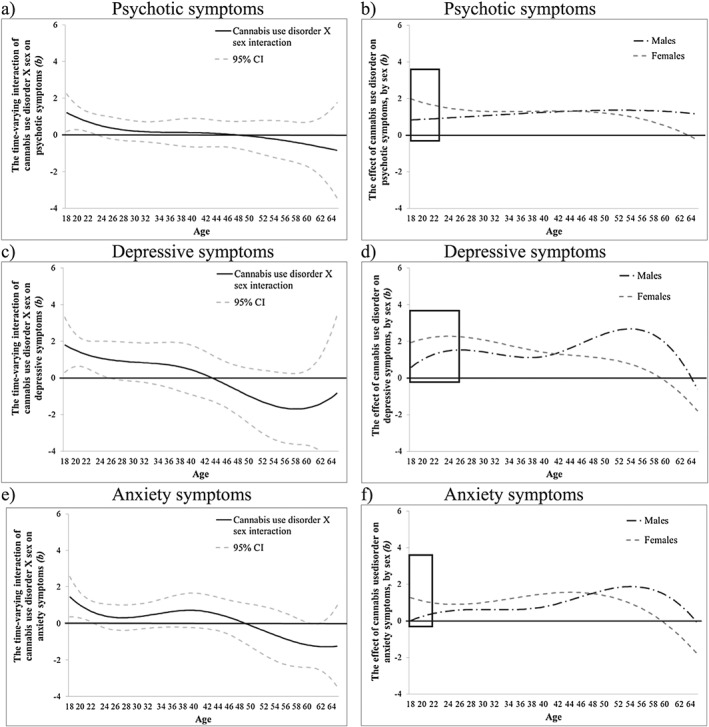

CUD was associated with more psychotic symptoms from age 18 (b = 1.21, 95% CI = 0.66, 1.76) to age 64 (b = 1.09, 95% CI = 0.05, 2.12) (Fig. 8a), more depressive symptoms from age 18 (b = 0.96, 95% CI = 0.19, 1.73) to age 61 (b = 1.11, 95% CI = 0.01, 2.21) (Fig. 8b) and more anxiety symptoms from age 18 (b = 0.45, 95% CI = 0.02, 0.88) to age 62 (b = 0.75, 95% CI = 0.08, 1.43) (Fig. 8c). Time‐varying interactions of CUD with early age of onset were not significant beyond chance (Supporting information, Fig. S7). Time‐varying interactions of CUD with sex were significant for psychotic symptoms between ages 18 (b = 1.21, 95% CI = 0.18, 2.25) to age 23 (b = 0.56, 95% CI = 0.01, 1.12), for depressive symptoms between ages 18 (b = 1.81, 95% CI = 0.30, 3.31) to age 26 (b = 1.00, 95% CI = 0.01, 2.00) and for anxiety symptoms between ages 18 (b = 1.46, 95% CI = 0.36, 2.56) to age 22 (b = 0.59, 95% CI = 0.003, 1.18) (see Fig. 9a,c,e). During these periods, females showed stronger associations between CUD and mental health symptoms than males (Fig. 9b,d,f).

Figure 8.

National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC)‐III data: the time‐varying main effect (b) of cannabis use disorder on (a) psychotic, (b) depressive and (c) anxiety symptoms. Models are adjusted for sex, socio‐economic status (SES), cigarette use and heavy drinking. Results are presented as regression coefficients (b); 95% confidence interval (CI) (dashed lines) that do not include 0 indicate periods of significance

Figure 9.

NESARC‐III data: the time‐varying interaction (b) of cannabis use disorder by sex on psychotic symptoms (a,b), depressive (c,d) and anxiety (e,f) symptoms. The time‐varying interaction is plotted on the left. The sex difference in the main effect is plotted on the right; the area inside the box represents the approximate ages when the sex interaction is significant (P < 0.05). Models are adjusted for socio‐economic status (SES), cigarette use and heavy drinking. b = regression coefficient; CI = confidence intervals

Discussion

This study is the first, to our knowledge, to examine the strength of the associations of CU and CUD with symptoms of psychosis, depression and anxiety at each age in adolescence (V‐HYS) and in adults (NESARC‐III). We used TVEM, which does not assume linear relations among the variables and allows for changes in the strengths of associations at each age 30. Our findings are consistent with past research showing associations between CU and psychosis in late adolescence and early young adulthood 3, 4, 5, 6. The associations with depression and anxiety is less consistent in past research 4, 5, 7. We also accounted for SES, cigarette use and HED and examined the moderating effects of age of onset and sex. Interactions with age of onset were not significant. Sex differences were significant.

In the V‐HYS, CU and CUD were associated with symptoms of psychosis (after age 22) and depression (ages 16–19 and after 25), but not anxiety. Findings were not significant for anxiety for the V‐HYS sample and this association was weakest for the NESARC‐III sample, suggesting power limitations due to the smaller sample size of the V‐HYS sample may have decreased our ability to detect associations. Associations with anxiety peaked in ages 40s and 50s for the NESARC‐III. Findings of associations between CU and anxiety disorders are also inconsistent in past research 32. Individuals experiencing anxiety symptoms may avoid CU if anxiety is experienced as an effect 10.

In the V‐HYS, the associations with CUD and psychosis and depressive symptoms were stronger for females than males after age 23–25. Associations for depressive symptoms were stronger for males than females at ages 19–20. In the NESARC‐III, CU and CUD were associated with all three mental health symptoms across age and associations were stronger for females, in young adulthood (approximately ages 18–25). These findings are consistent with a growing body of research 33, 34 showing that associations between CUD and mental health symptoms are stronger in females relative to males in young adulthood. Females appear to have a shorter or ‘telescoped’ trajectory from experimentation to addiction 35. In the V‐HYS, males showed significantly higher associations between depressive symptoms at ages 19–20 compared to females. This may be related to males’ more frequent use of greater amounts of cannabis, and greater impulsivity, sensation‐seeking and avoidant coping strategies at this age 22. Differences may also reflect sex differences in neural systems responsible for motivation and addiction or variations in contexts of CU by males (e.g. with peers or in sports) compared to females, who may be more likely to use substances in isolation for self‐medication or stress reduction 36.

Contrary to expectations from past literature, the interaction of CU frequency or CUD and mental health symptoms with early age of onset (15 years or younger) were not significant. Early onset of CU may have cascading effects that affect other age‐specific areas of concern including contributions to legal, work and relationship problems that are subsequently associated with increasing mental health symptoms 5, 11, 12. Longitudinal data following early‐onset users well into adulthood is needed to unravel whether early onset has a distinctive age‐sensitive association with mental health.

As with all correlational research, the causal direction of effects cannot be determined; however, the consistent association of CU frequency and CUD with symptoms of psychosis and depression across age groups suggests that more research with adults is needed. The strength of associations was not specific to the typical ages of onset of psychosis or depression 16 or attributable to early onset of CU. Adolescents and adults experiencing psychosis or depression may also experience aggravated symptoms if they begin or continue to use cannabis.

Limitations

Limitations of this study should be noted. Although the NESARC‐III over‐sampled Black, Hispanic and Asian adults 25, the majority of participants in both samples were non‐Hispanic white, and findings may not be generalizable to minority individuals. We excluded youth under age 15 in the V‐HYS and adults over 65 in the NESARC‐III sample due to low frequency of use of cannabis. All data are self‐report and social desirability may reduce reports of CU and mental health symptoms in both samples. It may also be difficult to separate the symptoms of acute CU intoxication from symptoms of psychosis; however, CUD assesses the functional impact of CU 24 and patterns of association were similar for CU and CUD. Our measure of CU did not consider the amount or potency of cannabis and early onset was measured as dichotomous. The cut‐off of age 15 is used to be consistent with past research 5. Many of the known co‐occurring liabilities associated with substance use and mental health disorders were not measured. However, SES, which may be a proxy for these concerns, was included in all analyses.

Implications and conclusions

Our findings are consistent with previous research that focuses only on the association between CU and symptoms of psychosis and depression in adolescents and young adults 3, 4, 5. However, these associations are not specific to adolescents or young adults or only concern for individuals with an early onset of CU. Considerable research has focused on the mental health and neurocognitive effects of CU during adolescence, but the links between CU or CUD and mental health in adulthood are less well studied. We also know very little about the effects of CU on common treatments for mental health disorders such as selective serotonin re‐uptake inhibitors (SSRIs) or cognitive behavioral therapy. Individuals attempting to reduce these mental health symptoms by using cannabis may be unsuccessful. Our findings suggest that reducing or abstaining from CU may improve mood, psychotic symptoms and possibly functioning at all ages. Continuing to increase our understanding of the consequences of recreational CU on mental health symptoms will improve advice to and decision‐making by individuals experiencing mental health concerns.

Declaration of interests

None.

Supporting information

Figure S1 V‐HYS data: Intercept‐only models for a) psychotic, b) depressive, and c) anxiety symptoms (solid line represents estimated mean). CI = confidence interval.

Figure S2 V‐HYS data: The time‐varying interaction (b) of cannabis use frequency by early onset on a) psychotic, b) depressive, and b) anxiety symptoms. Models are adjusted for SES, cigarette use, and heavy drinking. b = regression coefficient; CI = confidence intervals.

Figure S3 V‐HYS data: The time‐varying interaction (b) of cannabis use frequency by sex on a) psychotic, b) depressive, and c) anxiety symptoms. Models are adjusted for SES, cigarette use, and heavy drinking. b = regression coefficient; CI = confidence intervals.

Figure S4 V‐HYS data: The time‐varying interactions (b) of cannabis use disorder by early onset on d) psychotic, e) depressive, and f) anxiety symptoms. Models are adjusted for SES, cigarette use, and heavy drinking. b = regression coefficient; CI = confidence intervals.

Figure S5 NESARC‐III data: Intercept‐only models for a) psychotic symptoms, b) depressive symptoms, and c) anxiety symptoms (solid line represents estimated mean). CI = confidence interval.

Figure S6 NESARC‐III data: The time‐varying interaction (b) of cannabis use frequency by early onset on a) psychotic, b) depressive, and b) anxiety symptoms. Models are adjusted for SES, cigarette use, and heavy drinking. b = regression coefficient; CI = confidence intervals.

Figure S7 NESARC‐III data: The time‐varying interaction (b) of cannabis use disorder by early onset on a) psychotic, b) depressive, and c) anxiety symptoms. Models are adjusted for SES, cigarette use, and heavy drinking. b = regression coefficient; CI = confidence intervals.

Acknowledgements

The Victoria Healthy Youth Survey study and this research were supported by grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (#88476; #79917; #192583; #130500; SHI‐155410). The second author (M.E.A.) is also funded by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Fellowship Award (#146615) and a Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research Trainee Award (#16637). This paper was prepared using a limited‐access data set obtained from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism and does not reflect the opinions or view of NIAAA or the US Government. The current study is supported by awards P50 DA039838 (PI: Collins) from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). The NIDA did not have any role in study design, collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; writing the report; and the decision to submit the report for publication.

Leadbeater, B. J. , Ames, M. E. , and Linden‐Carmichael, A. N. (2019) Age‐varying effects of cannabis use frequency and disorder on symptoms of psychosis, depression and anxiety in adolescents and adults. Addiction, 114: 278–293. 10.1111/add.14459.

References

- 1. Gore F. M., Bloem P. J. N., Patton G. C., Ferguson J., Joseph V., Coffey C. et al Global burden of disease in young people aged 10–24 years: a systematic analysis. Lancet 2011; 377: 2093–2102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Whiteford H. A., Degenhardt L., Rehm J., Baxter A. J., Ferrari A. J., Erskine H. E. et al Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: findings from the global burden of disease study 2010. Lancet 2013; 382: 1575–1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hamilton I. Cannabis, psychosis and schizophrenia: unravelling a complex interaction. Addiction 2017; 112: 1653–1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hanna R. C., Perez J. M., Ghose S. Cannabis and development of dual diagnoses: a literature review. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 2017; 43: 442–455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Levine A., Clemenza K., Rynn M., Lieberman J. Evidence for the risks and consequences of adolescent cannabis exposure. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2017; 56: 214–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pauselli L. Cannabis‐induced psychotic disorder In: Compton M., Manseau M., editors. The Complex Connection between Cannabis and Schizophrenia. San Diego, CA: Elsevier Academic Press; 2018, pp. 183–197. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Twomey C. D. Association of cannabis use with the development of elevated anxiety symptoms in the general population: a meta‐analysis. J Epidemiol Community Health 2017; 71: 811–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Arseneault L., Cannon M., Poulton R., Murray R., Caspi A., Moffitt T. E. Cannabis use in adolescence and risk for adult psychosis: longitudinal prospective study. BMJ 2002; 325: 1212–1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Degenhardt L., Coffey C., Romaniuk H., Swift W., Carlin J. B., Hall W. D. et al The persistence of the association between adolescent cannabis use and common mental disorders into young adulthood. Addiction 2013; 108: 124–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Danielsson A. K., Lundin A., Agardh E., Allebeck P., Forsell Y. Cannabis use, depression and anxiety: a 3‐year prospective population‐based study. J Affect Disord 2016; 193: 103–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Luciana M. Adolescent brain development in normality and psychopathology. Dev Psychopathol 2013; 25: 1325–1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Winters K. C., Lee C. Y. S. Likelihood of developing an alcohol and cannabis use disorder during youth: association with recent use and age. Drug Alcohol Depend 2008; 92: 239–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chen C. Y., Wagner F. A., Anthony J. C. Marijuana use and the risk of major depressive episode: epidemiological evidence from the United States National Comorbidity Survey. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2002; 37: 199–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. D'Souza D. C., Ranganathan M., Braley G., Gueorguieva R., Zimolo Z., Cooper T. et al Blunted psychotomimetic and amnestic effects of Δ‐9‐ tetrahydrocannabinol in frequent users of cannabis. Neuropsychopharmacology 2008; 33: 2505–2516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Koethe D., Gerth C. W., Neatby M. A., Haensel A., Thies M., Schneider U. et al Disturbances of visual information processing in early states of psychosis and experimental delta‐9‐tetrahydrocannabinol altered states of consciousness. Schizophr Res 2006; 88: 142–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kessler R. C., Berglund P., Demler O., Jin R., Merikangas K. R., Walters E. E. Lifetime prevalence and age‐of‐onset distributions of DSM‐IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005; 62: 593–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Merikangas K. R., He J. P., Burstein M., Swanson S. A., Avenevoli S., Cui L. et al Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: results from the national comorbidity survey replication‐adolescent supplement (NCS‐A). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2010; 49: 980–989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cuttler C., Mischley L. K., Sexton M. Sex differences in cannabis use and effects: a cross‐sectional survey of cannabis users. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res 2016; 1: 166–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hankin B. L., Abramson L. Y., Moffitt T. E., Silva P. A., McGee R., Angell K. E. Development of depression from preadolescence to young adulthood: emerging gender differences in a 10‐year longitudinal study. J Abnorm Psychol 1998; 107: 128–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hyde J. S., Mezulis A. H., Abramson L. Y. The ABCs of depression: integrating affective, biological, and cognitive models to explain the emergence of the gender difference in depression. Psychol Rev 2008; 115: 291–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Patton G. C., Coffey C., Carlin J. B., Degenhardt L., Lynskey M., Hall W. Cannabis use and mental health in young people: cohort study. BMJ 2002; 325: 1195–1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Crane N. A., Langenecker S. A., Mermelstein R. J. Gender differences in the associations among marijuana use, cigarette use, and symptoms of depression during adolescence and young adulthood. Addict Behav 2015; 49: 33–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Leadbeater B., Thompson K., Gruppuso V. Co‐occurring trajectories of symptoms of anxiety, depression, and oppositional defiance from adolescence to young adulthood. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 2012. Jan; 41: 719–730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM–5). Washington, DC: Author; 2013.

- 25. Grant B., Chu A., Sigman R., Amsbary M., Kali J., Sugawara Y. et al Source and Accuracy Statement: National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions–III (NESARC‐III). Rockville, MD: NESARC; 2014.

- 26. Sheehan D., Janavas J., Knapp E. et al Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview, Clinician Rated, Version 4.4 . Tampa: University of South Florida College of Medicine; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Derogatis L. SCL‐90‐R: Administration, Scoring and Procedures: Manual II. Baltimore, MD: Clinical Psychometric Research; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cunningham C., Boyle M., Hong S., Pettingill P., Bohaychuk D. The brief child and family phone interview (BCFPI): rationale, development, and description of a computerized children's mental health intake and outcome assessment tool. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2009; 50: 416–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Thompson K., Merrin G., Ames M., Leadbeater B. Marijuana trajectories in Canadian youth: associations with substance use and mental health. Can J Behav Sci 2018; 50: 17–28. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Li R., Dziak J. J., Tan X., Huang L., Wagner A. T., Yang J. TVEM (Time‐Varying Effect Model) SAS Macro Users’ Guide. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dziak J. J., Tan X., Wagner A. T. TVEM (Time‐Varying Effect Modeling) SAS Macro Users’ Guide. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University; 2015.

- 32. Moore T. H. M., Zammit S., Lingford‐Hughes A., Barnes T. R. E., Jones P. B., Burke M. et al Cannabis use and risk of psychotic or affective mental health outcomes: a systematic review. Lancet 2007; 370: 319–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cooper Z. D., Haney M. Investigation of sex‐dependent effects of cannabis in daily cannabis smokers. Drug Alcohol Depend 2014; 136: 85–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hammerslag L. R., Gulley J. M. Sex differences in behavior and neural development and their role in adolescent vulnerability to substance use. Behav Brain Res [internet] 2016; 298: 15–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Khan S. S., Secades‐Villa R., Okuda M., Wang S., Pérez‐Fuentes G., Kerridge B. T. et al Gender differences in cannabis use disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey of Alcohol and Related Conditions. Drug Alcohol Depend [internet] 2013; 130: 101–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Becker J. B., Perry A. N., Westenbroek C. Sex differences in the neural mechanisms mediating addiction: A new synthesis and hypothesis. Biol Sex Differ 2012; 3: 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1 V‐HYS data: Intercept‐only models for a) psychotic, b) depressive, and c) anxiety symptoms (solid line represents estimated mean). CI = confidence interval.

Figure S2 V‐HYS data: The time‐varying interaction (b) of cannabis use frequency by early onset on a) psychotic, b) depressive, and b) anxiety symptoms. Models are adjusted for SES, cigarette use, and heavy drinking. b = regression coefficient; CI = confidence intervals.

Figure S3 V‐HYS data: The time‐varying interaction (b) of cannabis use frequency by sex on a) psychotic, b) depressive, and c) anxiety symptoms. Models are adjusted for SES, cigarette use, and heavy drinking. b = regression coefficient; CI = confidence intervals.

Figure S4 V‐HYS data: The time‐varying interactions (b) of cannabis use disorder by early onset on d) psychotic, e) depressive, and f) anxiety symptoms. Models are adjusted for SES, cigarette use, and heavy drinking. b = regression coefficient; CI = confidence intervals.

Figure S5 NESARC‐III data: Intercept‐only models for a) psychotic symptoms, b) depressive symptoms, and c) anxiety symptoms (solid line represents estimated mean). CI = confidence interval.

Figure S6 NESARC‐III data: The time‐varying interaction (b) of cannabis use frequency by early onset on a) psychotic, b) depressive, and b) anxiety symptoms. Models are adjusted for SES, cigarette use, and heavy drinking. b = regression coefficient; CI = confidence intervals.

Figure S7 NESARC‐III data: The time‐varying interaction (b) of cannabis use disorder by early onset on a) psychotic, b) depressive, and c) anxiety symptoms. Models are adjusted for SES, cigarette use, and heavy drinking. b = regression coefficient; CI = confidence intervals.