Abstract

Spliceostatin A is a potent inhibitor of spliceosomes and exhibits excellent anticancer activity against multiple human cancer cell lines. We describe here the design and synthesis of a stable cyclopropane derivative of spliceostatin A. The synthesis involved a cross-metathesis or a Suzuki cross-coupling reaction as the key step. The functionalized epoxy alcohol ring was constructed from commercially available optically active tri-O-acetyl-D-glucal. The biological properties of the cyclopropyl derivative revealed that it is active in human cells and inhibits splicing in vitro comparable to spliceostatin A.

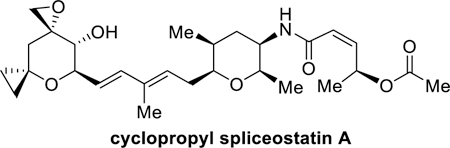

Graphical Abstract

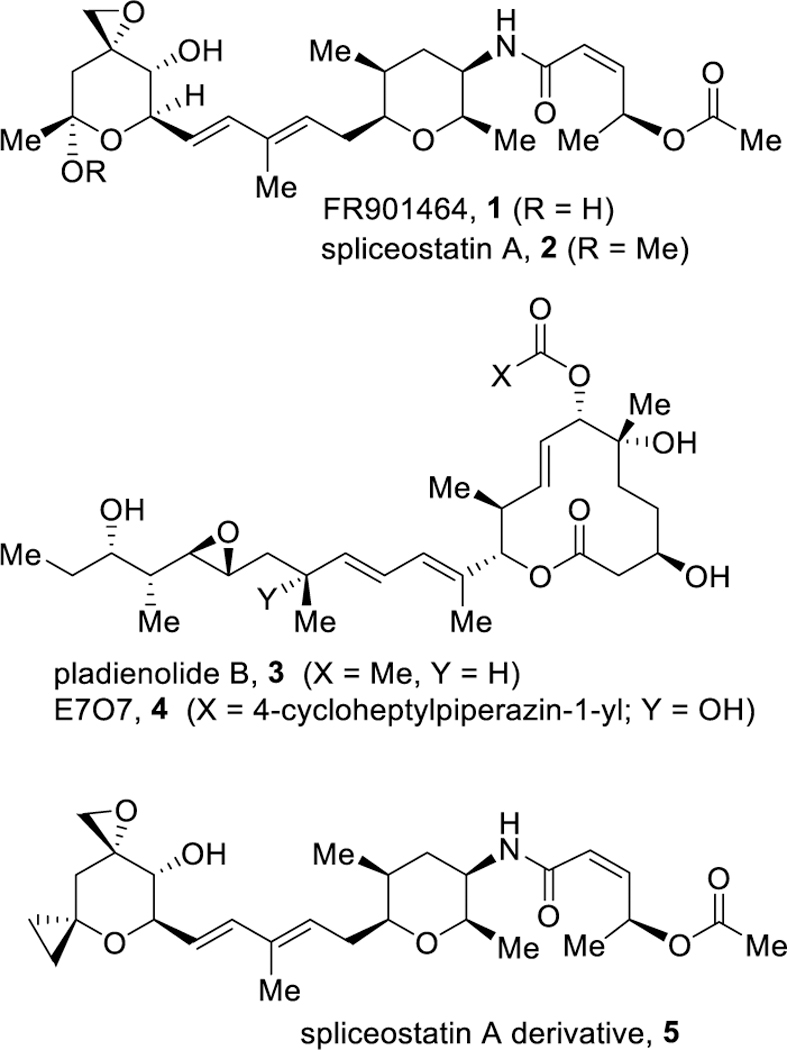

The majority of eukaryotic genes are expressed as precursor mRNAs (pre-mRNAs) which are then converted to mRNAs by splicing.1,2 This event is carried out by the multi-megadalton ribonucleoprotein complex, spliceosome, which upon recognition of a splicing signal, catalyzes the removal of non-coding sequences (introns) and joins protein coding sequences (eons) to form messenger RNAs.3,4,5 These get exported to cytoplasm for translation into proteins. While these transcription and translation processes are complex, recent studies have demonstrated that splicing is pathologically altered to promote the initiation and maintenance of cancer.6,7 Splicing involves numerous protein-protein and protein-RNA interactions which offer opportunities to manipulate or inhibit the splicing cascade for therapeutic purposes, particularly in the area of anticancer drug development.8,9 Presently, a number of natural products and their derivatives are known to potently inhibit spliceosome function by binding to the SF3B subunit of U2 SnRNP.10,11,12 These include, FR901464 (1, Figure 1), spliceostatin A(2), pladienolide B (3), and a semisynthetic derivative E7O7, 4.13,14,15 The precise molecular interactions of these molecules with SF3B are being investigated using cryo-electron microscopy.16,17,18 While these natural products display potent splicing activity their clinical use is limited due to chemical instability and inadequate physiochemical properties. To date, a semi synthetic derivative of pladienolide E7O7, (4), was developed with improved pharmacological properties for clinical development.19 A number of spliceostatin derivatives have seen specifically synthesized as payloads for antibody-drug conjugates.20,21 Both FR901464 (1) and spliceostatin A(2) show very potent antitumor properties. FR901464 displayed IC50 values ranging from 0.6 to 3.4 nM against multiple human cancer cell lines. It also showed effectiveness against solid tumors implanted in mice at a dose range of 0.05 to 1 mg/kg.14,22 Spliceostatin A showed similar activity. As a result, these compounds attracted much attention for synthesis and medicinal chemistry development. We recently reported the synthesis and structure-activity studies of both these compounds.23,24 Nicolaou and co-workers also reported structural modifications of spliceostatin derivatives.25 In our continued interest in developing molecular probes for splicing studies, we devised cyclopropyl derivative of FR901464 and spliceostatin A, where a cyclopropane is incorporated at the anomeric site of FR901464 and spliceostatin A to improve stability and potency. We have devised an enantioselective synthesis of the epoxide subunit using readily available tri-O-acetyl-D-glucal as the key starting material and investigated coupling using cross-metathesis and Suzuki reactions. The synthesis will provide ready access to stable spliceostatin derivatives for biological studies.

Figure 1.

Structures of spliceosome inhibitors 1–5

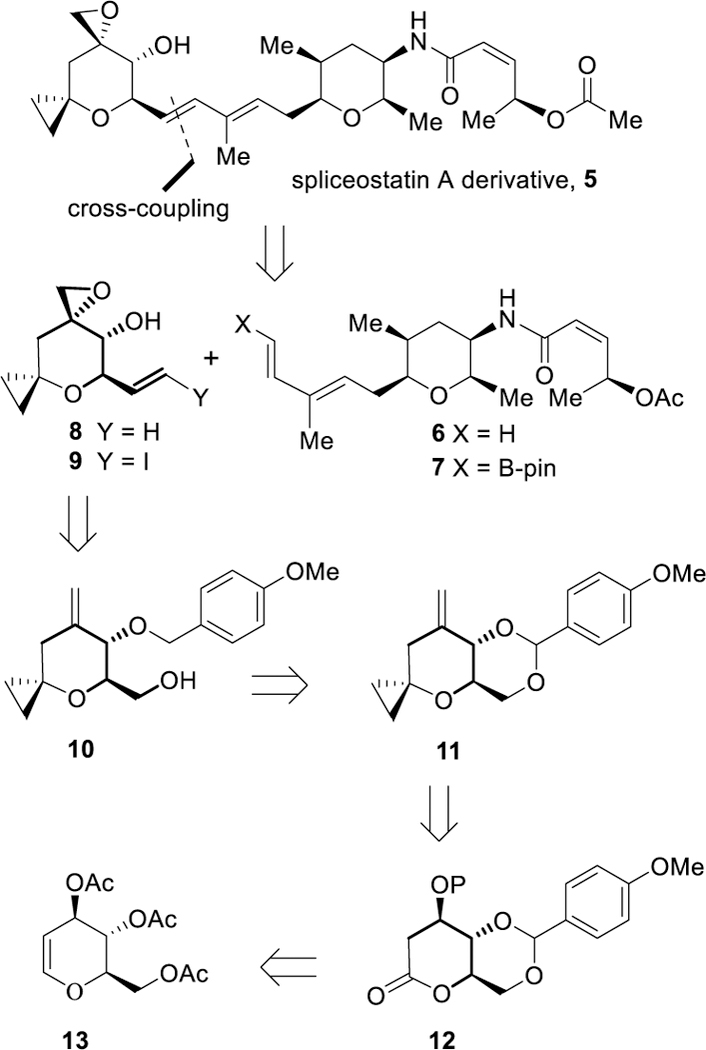

Our synthetic strategy for the construction of the cyclopropyl derivative of spliceostatin A is shown in Scheme 1. We initially planned cross metathesis of diene 6 and epoxy olefin 8 using Grubbs’ 2nd generation catalyst. This cross metathesis reaction typically yields a mixture of olefin dimer, diene dimer, and the desired cross-coupling product. We also planned to investigate a Suzuki cross-coupling reaction between the known26,27 pinacol borononate 7 and vinyl iodide derivative 9 to provide the desired cross-coupling product 5. The synthesis of pinacol boronate 7 would be achieved in optically active form using our recently reported procedure.27 The synthesis of cyclopropyl epoxide segment 8 or 9 would be carried out from alcohol 10 which would be derived from 4-methoxybenzylidene acetal 11 by reduction with Dibal-H. Acetal 11 can be synthesized from δ-lactone 12 by synthetic manipulation from standard commercially available optically active tri-O-acetyl-D-glucal 13.

Scheme 1.

Retrosynthesis of spliceostatin derivative

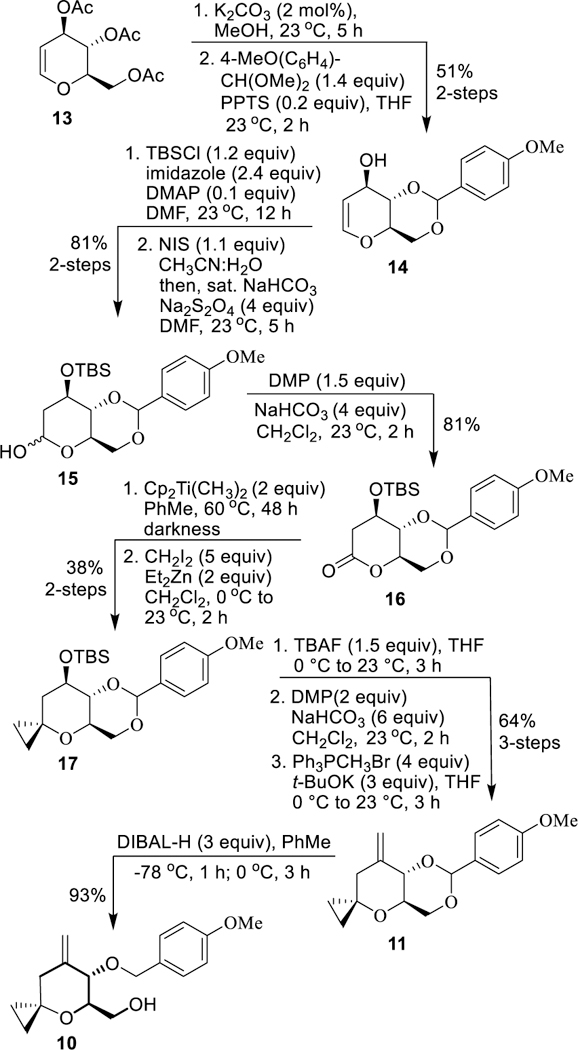

Enantioselective synthesis of 7-methylene-4-oxaspiro[2.5]octane derivative 10 is shown in Scheme 2. The preparation of benzylidene acetal 14 was carried out in multi-gram scale using commercially available tri-O-acetyl-D-glucal 13 with minor modifications.28 Treatment of 13 with K2CO3 in MeOH at 23 °C for 5 h provided the corresponding triol. Reaction of the resulting triol with 1-(dimethoxy)-4-methoxybenzene in the presence of a catalytic amount of PPTS at 23 °C for 2 h afforded benzylidene acetal 14. It was protected as the TBS-ether using TBSCl and imidazole in the presence of a catalytic amount of DMAP in DMF at 23 °C for 12 h. The resulting TBS-ether was treated with NIS in a mixture (95:5) of CH3CN and water at 23 °C for 15 min and the mixture was concentrated. The residue was dissolved in DMF and saturated NaHCO3 and Na2S2O4 were added and the mixture was stirred at 23 °C for 5 h to provide lactol 15 in 81% yield over 2-steps.29,30 Oxidation of lactol 15 with Dess-Martin periodinane (DMP) in the presence of NaHCO3 in CH2Cl2 at 0 °C to 23 °C for 2 h furnished lactone derivative 16 in 81% yield. To install the cyclopropane ring, lactone 16 was treated with Petasis reagent31 in toluene at 23 °C and the resulting mixture was heated at 60 °C for 48 h to provide the corresponding enol-ether in 90% yield. Simmons-Smith cyclopropanation32 of the resulting enol ether with methylene diiodide and diethyl zinc in CH2Cl2 at 0 °C to 23 °C for 2 h afforded 4-oxaspiro[2,5]octane derivative 17 in 42% yield. Cyclopropane derivative 17 was converted to olefin 11 as follows. Treatment of TBS-ether 17 with TBAF in THF at 0 °C to 23 °C for 3 h provided the corresponding alcohol. Oxidation of the secondary alcohol to the corresponding ketone was achieved by treatment with DMP at 0 °C to 23 °C for 2 h. Wittig-olefination of the resulting ketone with methylenetriphenylphosphorane in THF at 0 °C to 23 °C for 3 h provided 11 in 64% yield over 3-steps. DIBAL-H reduction of benzylidene acetal 11 at −78 °C to 0 °C for 4 h furnished alcohol 10 in 93% yield.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of dihydropyranone 18

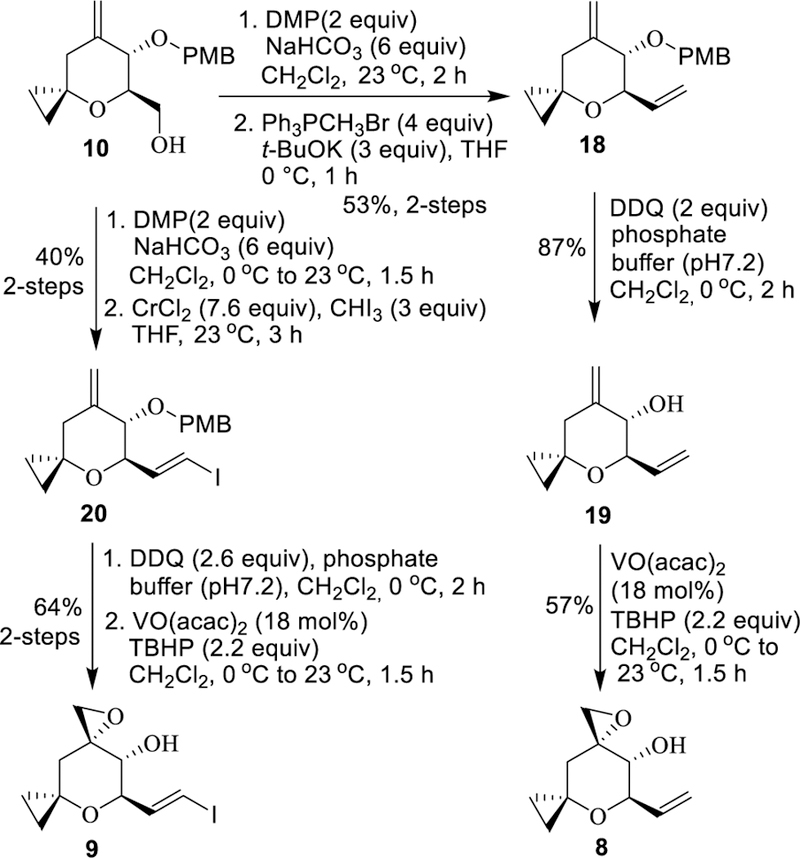

Conversion of alcohol 10 to epoxy alcohol derivatives 8 and 9 is shown in Scheme 3. Oxidation of alcohol 10 with DMP in the presence of NaHCO3 provided the corresponding aldehyde. Wittig-olefination of the resulting aldehyde with methylenetriphenylphosphorane in THF at 0 °C for 1 h afforded diene 18 in 53% yield over 2-steps. Removal of the PMB-group was carried out by exposure of 18 to DDQ in a mixture (10:1) of CH2Cl2 and phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) at 0 °C for 2 h to furnish homoallylic alcohol 19. Selective epoxidation of 19 with a catalytic amount (18 mol%) of VO(acac)2 in the presence of t-butyl hydroperoxide in CH2Cl2 at 0 °C to 23 °C for 1.5 h provided epoxy alcohol derivative 8 as a single diastereomer (by 1H-NMR analysis) in 57% yield (73% brsm). For the synthesis of vinyl iodide derivative 9, alcohol 10 was oxidized with DMP in the presence of NaHCO3 to provide the aldehyde in 48% yield. Takai olefination33 was carried out by reaction of the resulting aldehyde with a mixture of CrCl2 and CHI3 in THF at 23 °C for 3 h to furnish vinyl iodide 20 in 85% yield. Exposure of PMB-derivative 20 to DDQ in a mixture of CH2Cl2 and phosphate buffer resulted in deprotection of the PMB-group. Directed epoxidation of the resulting allyic alcohol with t-butyl hydroperoxide in the presence of a catalytic amount (18 mol%) of VO(acac)2 provided epoxy alcohol 9 in 64% yield over 2-steps.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of epoxy alcohol derivatives

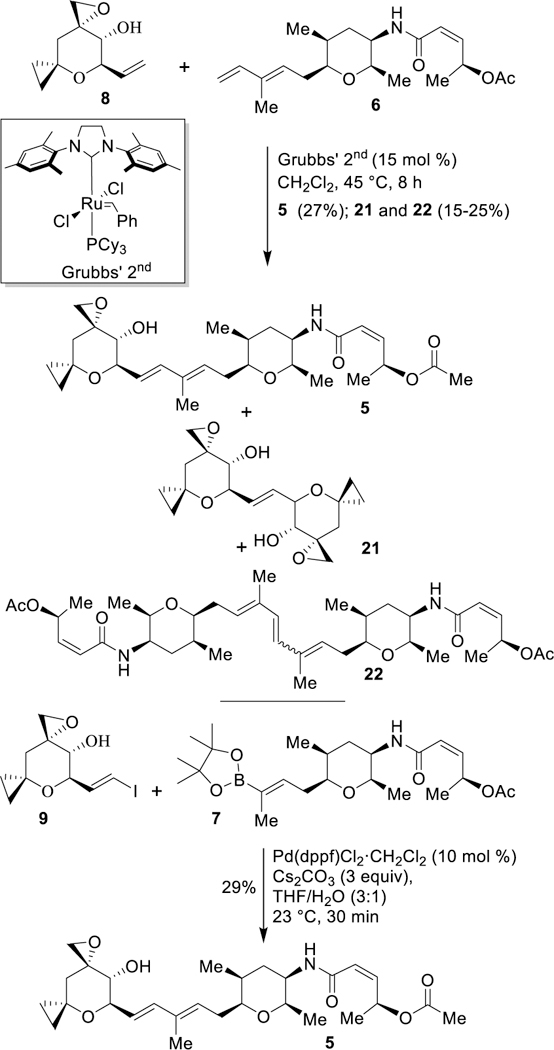

For the synthesis of the cyclopropyl derivative of spliceostatin A, we first carried out a cross metathesis34 reaction of diene 6 and epoxy olefin 8 as shown in Scheme 4. A mixture of epoxy olefin 8 and Grubbs’ II catalyst (15 mol%) in CH2Cl2 was prepared under argon atmostphere. To a stirred solution of diene 6 in CH2Cl2, a one-third portion of epoxy olefin 8 and Grubbs catalyst was added and the resulting mixture was heated at reflux for 1.5 h. The other two portions of catalyst and olefin mixture were added successively in 1.5 h intervals. The resulting mixture was stirred at reflux for an additional 1.5 h (total 8 h). The reaction was cooled to 23 °C and the mixture was concentrated. The residue was purified by silica gel chromatography to furnish cyclopropane derivative 5 in 27% yield. The cross metathesis reaction also provided an inseparable mixture of epoxide dimer and diene dimer as the by-products (21 and 22, about 25–30%). We then investigated a Suzuki coupling35 of known boronate 7 and vinyl iodide derivative 9 using Pd(dppf)2Cl2•DCM (10 mol%) catalyst in the presence of aqueous Cs2CO3 in THF at 23 °C for 30 min to provide the coupling product 5 in 29% yield. The yield for coupling product 5 via cross-metathesis or Suzuki coupling was comparable.

Scheme 4.

The synthesis of spliceostatin derivative 5

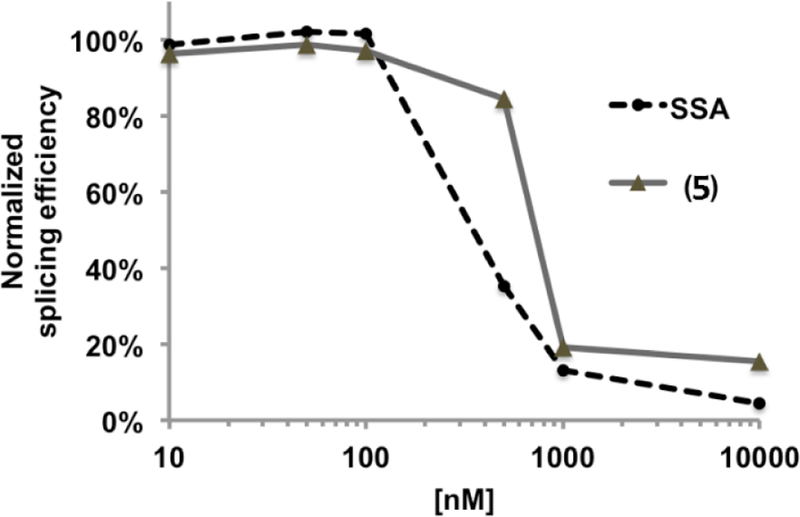

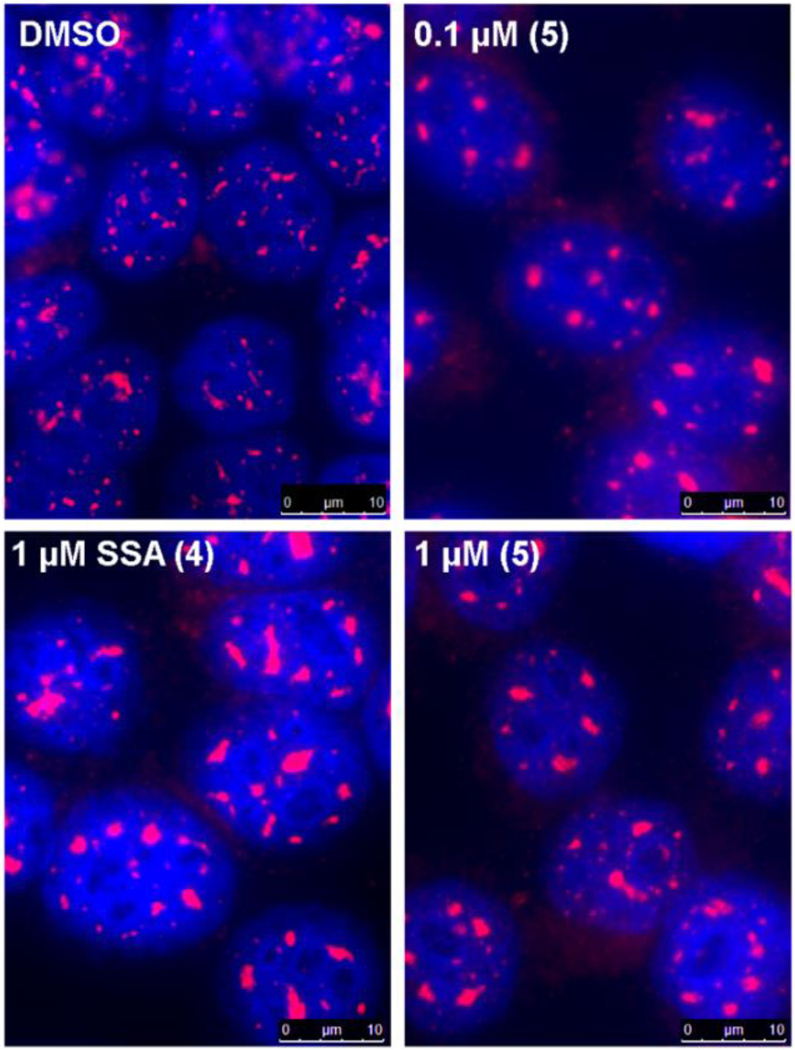

We evaluated the biological activity of this cyclopropane spliceostatin A (5) in an in vitro splicing system as previously described.36 The compound inhibits splicing, but at a slightly reduced (~2-fold lower) potency relative to spliceostatin A (Figure 2). The compound is also active in HeLa cells. It induces the coalescence of nuclear speckles as observed by immuno-staining of the splicing factor SFRS2 at similar levels as spliceostatin A (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Impact of compound 5 on in vitro splicing. Average splicing efficiency relative to inhibitor concentration normalized to no-drug control. Compound 5; SSA, spliceostatin A.

Figure 3.

Changes in nuclear speckle morphology. Fluorescent images of in HeLa cells nuclei incubated four hours with the indicated compound, then fixed and stained with DAPI (blue) and anti-SRSF2 antibody (magenta).

In summary, we reported the design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of a cyclopropane derivative of spliceostatin A and FR901464. The synthesis of the cyclopropane derivatives 8 and 9 for coupling reactions was carried out enantioselectively from commercially available, optically active tri-O-acetyl-D-glucal. We have investigated both a cross-metathesis route as well as a Suzuki coupling and both coupling reactions provided the final derivative in comparable yield.

Our design of cyclopropane ring conceivably removed one chiral center and also improved chemical stability of the resulting cyclopropane derivative. We have evaluated spliceosome inhibitory activity of the cyclopropane derivative 5 and compared its activity with spliceostatin A. The compound is very active in HeLa cells. Also, compound 5 induces the coalescence of nuclear speckles at a similar level to spliceostatin A. As it turns out, the cyclopropane derivative exhibited comparable potency to spliceostatin A. Further design and synthesis of structural variants of spliceostatins are underway.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Financial support of this work was provided by the National Institutes of Health (GM122279) and Purdue University. The authors thank Ms. Hannah Simpson and Mr. Josh Born (both, Purdue University) for valuable discussions

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

Experimental procedures in addition to 1H- and 13C-NMR spectra are available for all new compounds. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Supporting Information Available General experimental procedures, characterization data for all new products. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Roybal GA; Jurica MS Nucleic Acids Res 2010, 38, 6664–6672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wahl MC; Will CL; Lührmann R Cell 2009, 136, 701–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shi Y Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol 2017, 18, 655–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Will CL; Luhrmann R Cold Spring Harb. Perspect Biol 2011, 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Raymond B Nat. Chem. Biol 2007, 3, 533–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Alphen RJ; Wiemer EA; Burger H; Eskens FA Br. J. Cancer 2009, 100, 228–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cooper TA; Wan L; Dreyfuss G Cell 2009, 136, 777–793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee SC-W; Abdel-Wahab O Nat. Med 2016, 22, 976–986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pal S; Gupta R; Kim H; Wickramasinghe P; Baubet V; Showe LC; Dahmane N; Davuluri RV Genome Res 2011, 21, 1260–1272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Alphen RJ; Wiemer EAC; Burger H; Eskens FALM Brit. J. Cancer 2009, 100, 228–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hsu TY-T; Simon LM; Neill NJ; Marcotte R; Sayad A; Bland CS; Echeverria GV; Sun T; Kurley SJ; Tyagi S; Karlin KL; Dominguez-Vidaña R; Hartman JD; Renwick A; Scorsone K; Bernardi RJ; Skinner SO; Jain A; Orellana M; Lagisetti C; Golding I; Jung SY; Neilson JR; Zhang XH-F; Cooper TA; Webb TR; Neel BG; Shaw CA; Westbrook TF Nature, 2015, 525, 384–388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sidarovich A; Will CL; Anokhina MM; Ceballos J; Sievers S; Agafonov DE; Samatov T; Bao P; Kastner B; Urlaub H; Waldmann H; Lührmann R eLife, 2017, 6, e23533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sakai T; Sameshima T; Matsufuji M; Kawamura N; Dobashi K; Mizui Y J. Antibiot 2004, 57, 173–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sakai T; Asai N; Okuda A; Kawamura N; Mizui Y .J. Antibiot 2004, 57, 180–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sato M; Muguruma N; Nakagawa T; Okamoto K; Kimura T; Kitamura S; Yano H; Sannomiya K; Goji T; Miyamoto H; Okahisa T; Mikasa H; Wada S; Iwata M; Takayama T Cancer Sci 2014, 105, 110–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kotake Y; Sagane K; Owa T; Mimori-Kiyosue Y; Shimizu H; Uesugi M; Ishihama Y; Iwata M; Mizui Y Nat. Chem. Biol 2007, 3, 570–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yokoi A; Kotake Y; Takahashi K; Kadowaki T; Matsumoto Y; Minoshima Y; Sugi NH; Sagane K; Hamaguchi M; Iwata M; Mizui Y FEBS J 2011, 278, 4870–4880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Galej WP; Wilkinson ME; Fica SM; Oubridge C; Newman AJ; Nagai K Nature 2016, 537, 197–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bonnal S; Vigevani L; Valcárcel Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 2012, 11, 847–859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beck A; Goetsch L; Dumontet C; Corvaïa N Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 2017, 16, 315–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bessire AJ; Ballard TE; Charati M; Cohen J; Green M; Lam M-H; Loganzo F; Nolting B; Pierce B; Puthenveetil S; Roberts L; Schildknegt K; Subramanyam C Bioconjugate Chem 2016, 27, 1645–1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mizui Y; Sakai T; Iwata M; Uenaka T; Okamoto K; Shimizu H; Yamori T; Yoshimatsu K; Asada M J. Antibiot 2004, 57, 188–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ghosh AK; Chen Z-H Org. Lett 2013, 15, 5088–5091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ghosh AK; Chen Z-H; Effenberger KA; Jurica MS J. Org. Chem 2014, 79, 5697–5709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nicolaou KC; Rhoades D; Kumar SM J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 8303–8320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nicolaou KC; Rhoades D; Lamani M; Pattanayak MR; Kumar SM J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 7532–7535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ghosh AK; Reddy GC;MacRae AJ; Jurica MS J. Org. Chem 2018, 26, 96–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bartolozzi A; Pacciani S; Benvenuti C; Cacciarini M; Liguori F; Menichetti S; Nativi C J. Org. Chem 2003, 68, 8529–8533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koviach JL; Chappell MD; Halcomb RL J. Org. Chem 2001, 66, 2318–2326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bolitt V; Mioskowski C; Lee SG; Falck JR J. Org. Chem 1990, 55, 5812–5813. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Petasis NA; Bzowej EI J. Am. Chem. Soc 1990, 112, 6392–6394. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lebel H; Marcoux J-F; Molinaro C; Charette AB Chem. Rev 2003, 103, 977–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takai K; Nitta K; Utimoto K J. Am. Chem. Soc 1986, 108, 7408–7410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chatterjee AK; Choi T-L; Sanders DP; Grubbs RH J. Am. Chem. Soc 2003, 125, 11360–11370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Suzuki A J. Organomet. Chem 1999, 576, 147–168. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Effenberger KA; Anderson DD; Bray WM; Prichard BE; Ma N; Adams MS; Ghosh AK; Jurica MS J. Biol. Chem 2014, 289, 1938–1947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.