Abstract

Wolbachia bacteria inhabit the cells of about half of all arthropod species, an unparalleled success stemming in large part from selfish invasive strategies. Cytoplasmic incompatibility (CI), whereby the symbiont makes itself essential to embryo viability, is the most common of these and constitutes a promising weapon against vector-borne diseases. After decades of theoretical and experimental struggle, major recent advances have been made toward a molecular understanding of this phenomenon. As pieces of the puzzle come together, from yeast and Drosophila fly transgenesis to CI diversity patterns in natural mosquito populations, it becomes clearer than ever that the CI induction and rescue stem from atoxin-antidote (TA) system. Further, the tight association of the CI genes with prophages provides clues to the possible evolutionary origin of this phenomenon and the levels of selection at play.

Every living organism is a chimera of different evolutionary lineages living in more or less tight association. Arthropods are emblematic of that rule and often carry bacteria within their own cells that are transmitted from mothers to offspring with the egg cytoplasm. These may offer benefits, such as vital nutrients to hosts feeding exclusively on sap or blood [1,2], and thus become essential parts of a new whole, but also often colonize host populations through selfish strategies, maximizing their own fitness regardless of possible detrimental effects to hosts [3,4]. Cytoplasmic incompatibility (CI; Figure 1 and Box 1) is one such strategy which has likely contributed in large part to the radiative success of Wolbachia bacteria that are now present in about half of all arthropod species [5–7].

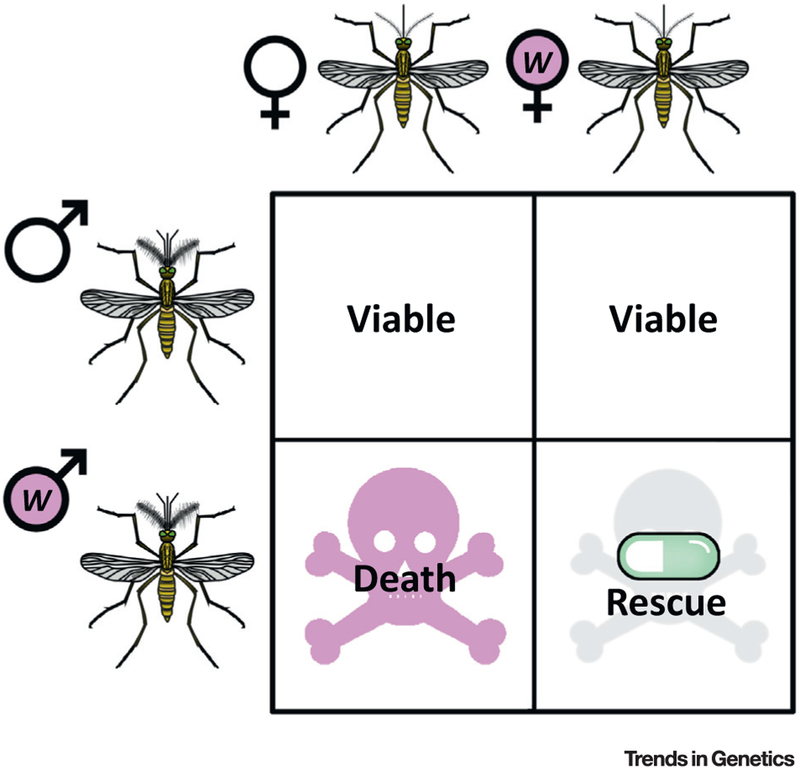

Figure 1. Cytoplasmic Incompatibility in Its Simplest Form.

Infectedfemalesarecompatiblewith both infected and uninfected males, whereas uninfected females produce viable offspring only if they mate with uninfected males. Abbreviation: w, Wolbachia-infected.

Box 1. Wolbachia and Cytoplasmic Incompatibility.

Perhapsthe most crucial aspect of Wolbachia biology is the fact it is transmitted from mothers to offspring through the egg cytoplasm [71], although horizontal transfer may also occur [7,45]. Vertical transmission through the female germline will select Wolbachia traits that increase the fitness of infected females, or, more technically, the number or the fitness of their infected daughters. CI can be interpreted within such a framework: by protecting infected embryos from the lethal effect of the sperm of infected males, Wolbachia increases the relative brood size of infected females. Infected males pay a heavy price for CI (mating with uninfected females drastically reduces their own fertility), but this is costless for Wolbachia because males do not transmit the symbiont to future generations. Notably, only few uninfected females are sterilized through CI when Wolbachia is rare in the host population, and a low-frequency infection therefore has a low chance of invasion, unless it combines CI with other traits such as protection of the host against pathogens [72]. Such protective effects are actually observed [73] and can also block the passage of human pathogens through insect vectors [74]. The ongoing World Mosquito Program makes use of this property: the massive release of CI-inducing mosquitoes allows spread of the infection, which should reduce overall viral transmission rates [75], although the implementation and evolutionary outcome of this approach remain uncertain [76,77].

CI Genetics

Although Wolbachia and CI were both discovered a long time ago in Culexpipiens mosquitoes [8–11], the causal link between the two was only made decades later [12,13]. By that time, early models had clarified the invasion dynamics of CI [14], that were later extended [15] and calibrated with empirical data [16,17], but a formal mechanistic model was proposed only in the 1990s [18–20]. The fact that sperm from Wolbachia-carrying males kills uninfected but not infected embryos upon fertilization is compatible with aTA model (Figure 2, Key Figure). The toxin factor, deposited in maturing sperm, would kill the embryos unless they are rescued by the antidote. Although concurrent explanations were also proposed [21,22], the discovery of Wolbachia strains capable of rescuing CI without inducing it further supported the notion that this phenomenon should involve two distinct factors [23,24]. The observations of independent effects of distinct Wolbachia strains, either in the context of multiple infections or mutual incompatibility between different Wolbachia strains, further suggested that the toxin and antidote should interact specifically, in a lock-and-key manner [25]. This framework generated a set of testable predictions that fueled the experimental quest to identify the CI genes, which was recently achieved [26–30].

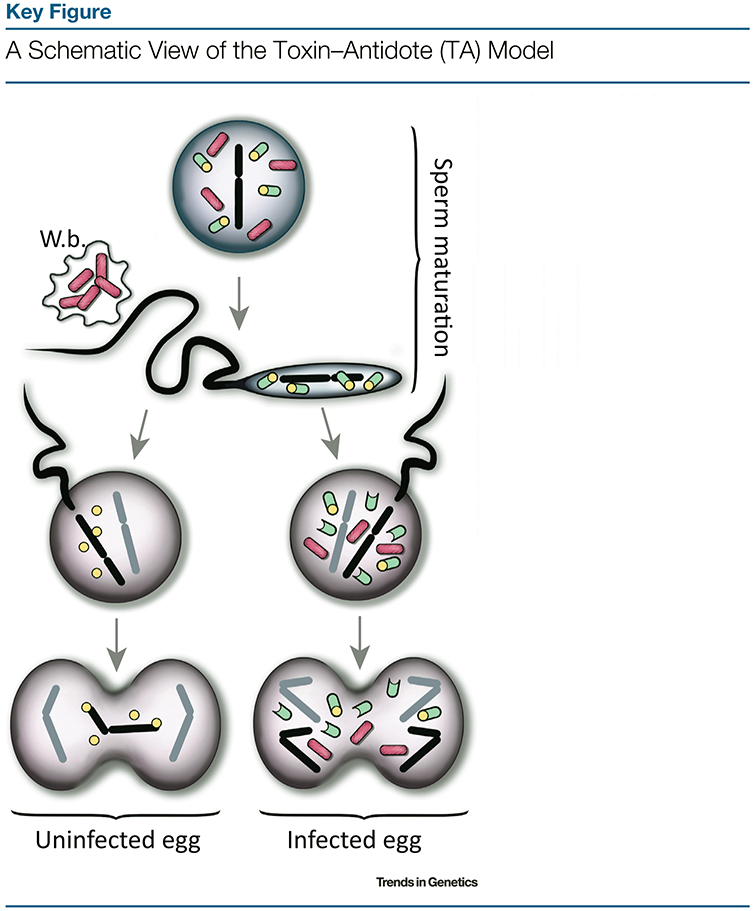

Figure 2.

In immature sperm, Wolbachia bacteria (pink) produce both a toxin (yellow particles) and its specific antidote (green particles). As Wolbachia are removed from maturing sperm into waste bags (W.b.), the antidote, presumably unstable, is lost faster than the toxin. Upon fertilization of an uninfected egg (left part), the toxin is thus present and active, impeding the paternal chromosomes through direct or indirect interactions with chromatin or DNA, which results in embryo death. In infected eggs, antidotes of maternal origin bind to the toxin and thus maintain embryo viability. Alternative cytoplasmic incompatibility (CI) mechanisms have been envisaged [21,22,82,83], but the model depicted here best accounts for all CI features [25], including its recently discovered genetic architecture [26–29].

The first evidence pointing to the two genes, later established as genuine CI factors, came from a sperm proteomic study based on the rationale that the hypothetical CI toxin should be present in mature sperm of infected males, even though the bacterium itself is not [26]. Inspired by earlier proteomic analyses of Drosophila sperm [31,32], this approach finally pinpointed the candidate CI genes in the mosquito Culex pipiens, where the high penetrance of CI associated with the wPip Wolbachia strain predicted a toxin protein detectable by mass spectrometry. Serendipity also played an essential role: the first CI protein identified in sperm in this study was later revealed not as the toxin gene product, as predicted, but as the antidote, the presence of which was not expected under the most parsimonious CI model [25]. Nevertheless, its synteny and cotranscription with another Wolbachia gene, later revealed as the CI toxin, was noted, as was the similarity of this locus with typical TA systems, usually composed of two genes, the first of which, the antidote, is expressed at higher levels [33]. Proximity of these putative CI genes to prophages in the wPip genome was also pointed out at that time [26].

The next major steps toward the demonstration that these genes and their homologs in Drosophila are responsible for the induction and rescue of CI came from a combination of approaches and model systems [27,28]. In line with the TA model, biochemical analysis and transgenic expression of the putative wPip CI genes in yeast revealed that they encode both a toxic deubiquitylase (DUB) and an inhibitor of this toxicity (DUBs are enzymes that specifically remove ubiquitin from ubiquitin-modified proteins). When transgenically expressed in uninfected Drosophila males crossed with uninfected females, these factors recapitulate CI induction during the first embryonic mitosis [27]. Importantly, the two proteins were also found to bind tightly to one another in a cognate-specific manner [27] consistent with prior lock-and-key predictions [25]. At the same time, independent experiments involving the homologs of these genes from the wMel Wolbachia strain, that naturally infects D. melanogaster, confirmed and complemented these results: their dual expression in uninfected Drosophila males induces a CI-like phenotype that, most importantly, is rescued by the presence of wMel bacteria in females [28].

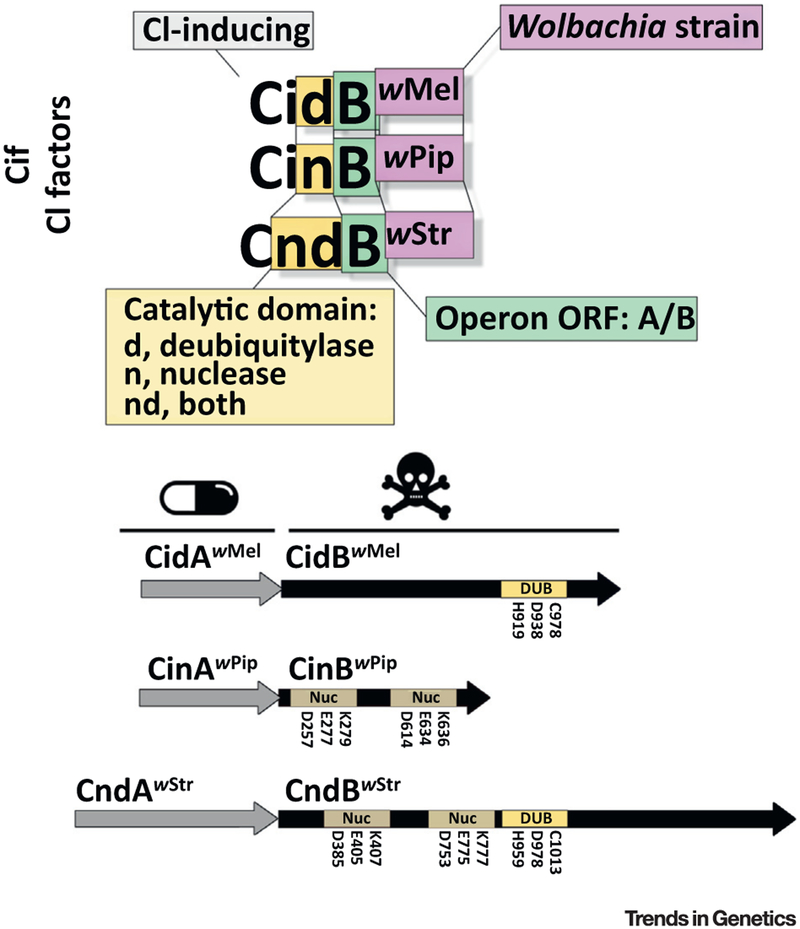

Before discussing the many questions raised by these results, a brief note is necessary to avoid ambiguities stemming from different CI gene nomenclatures coexisting in the literature [27,28] (Figure 3). One proposal is that the operon inducing a CI-like phenotype when expressed in Drosophila should be called ‘cid’, for ‘CI-inducing DUB’ [27]. This function-based name was chosen to explicitly distinguish cid from cin, short for ‘CI-inducing nuclease’, a paralogous operon in the wPip genome that encodes a nuclease with similar TA-like behavior in yeast, and also displays polycistronic transcription [26,27]. Within each operon, the first gene, encoding the putative antidote, is labeled A (e.g., cidA or cinA), and the second, encoding the putative toxin, is labeled B. A contrasting nomenclature proposes that all the different CI-associated genes should be more neutrally denoted ‘CI factors’ (cif), and that the different paralogs should be distinguished on the basis of phylogeny [28,34]. The ‘operon’ designation is also questioned by these authors, primarily because the two transcripts can be measured at different levels, which could be indicative of different promoters [34]. Nonetheless, no such distinct promoters have been identified, and different expression levels of two adjacent genes are not uncommon within bacterial operons [35]. In our view, the ‘operon’ designation is thus appropriate in the present case. Regardless of this semantic debate, the two genes within each potential CI locus are labeled A and B in both nomenclature proposals. Thus, cidA and cidB are synonymous with cifA and cifB (clade 1), respectively, and these constitute the major CI genes identified to date, recapitulating the phenotype in Drosophila. We see pros and cons in both nomenclatures, and suggest they should be merged into a single system to avoid further confusion. The ‘cif term (for CI factor) seems appropriate to designate CI genes in general, and we will use it in that sense. To denote their different functional categories and evolutionary histories, we will distinguish cid (the DUB operon) from cin (the nuclease operon), and use this dichotomy to designate specific cif genes from any Wolbachia strain. Some operons have been predicted to carry both functions; we suggest these should be called ‘cnd’ (Figure 3) [27,36]. When necessary, we append the Wolbachia strain name as a superscript. In our opinion, this system merges positives of both previously proposed nomenclatures and fairly acknowledges the concomitant discovery of these gene pairs in two separate studies [27,28].

Figure 3. A Nomenclature Proposal and Schematic View of Putative Cytoplasmic Incompatibility (CI) Operon Structures.

In this naming system, the cif (and Cif) terms designate CI genes (and proteins) in general, while genes from specific operon categories are named according to the enzymatic activity of the putative toxin [deubiquity-lase (DUB), nuclease (Nuc), or both]. The first and second genes within each operon are denoted A and B, respectively, and the Wolbachia strain is indicated as a superscript when relevant. The structure of several CI operons is shown to illustrate this system; active-site residues are labeled. Abbreviation: ORF, open reading frame.

Following publication of the first two conclusive reports on cif genes, two major unsettled points remained [28,34]. First, the antidote activity of the CidA protein, although demonstrated for both CidAwPip and CinAwPip in yeast, was not established in Drosophila. A more recent report has now clarified this point: if expressed in sufficient amount during oogenesis, CidAwMel was found to restore the viability of uninfected embryos fertilized by wMel-carrying Drosophila males [29]. A second major question, still not fully settled as of time of writing, is whether CidBcan act alone as the CI toxin or needs some interaction with CidA to express toxicity. Transgenic expression in yeast indicates that the DUB activity of CidBwPip has in itself a toxic effect, which is inhibited by coexpression of CidAwPip. However, Drosophila lines expressing CidBwPip alone were never obtained, making it impossible to directly assess its effect in this context [27]. A simple hypothesis, compatible with the idea that CidB alone is indeed the CI toxin, is that CidBwPip can exert deleterious effects outside the first embryonic mitosis, where CI is usually first realized, and therefore requires coexpression of CidA, the antidote, in any tissue where CidB is present, and at sufficiently high dosage. Such a model would also help to explain the paradoxical observation that first turned the spotlight toward the CI operon: the high dosage of CidA protein in mature sperm [26]. If this interpretation is correct, CI would result from removal or inactivation of the paternal CidA protein immediately before, or shortly after, fertilization.

At first sight, experiments involving transgenic expression of the cicdwMel genes in Drosophila argue against a toxic effect of CidBwMel alone: lines expressing this protein were viable and the CI phenotype was recapitulated only by males expressing both CidBwMel and CidAwMel [28]. This result has been considered by some authors as arguing for a ‘two-by-one’ model, in which CI induction would somehow rely on both CidA and CidB proteins, while rescue would rely on CidA only [29]. However, differences in the toxicity of CidBwMel and CidBwPip may reconcile these experimental results with a simple TA model. Although the wMel Wolbachia strain may induce very high CI in a permissive host background (e.g., upon artificial transfer into Drosophila simulans) [37], it is well established that it has a low penetrance in its natural host [38], possibly as a result of past coevolution [39]. Low toxicity of CidBwMel in D. melanogaster would explain why flies expressing this protein alone can survive. However, why then is CI not expressed in such transgenic lines? One possibility is that CidBwMel is sufficiently toxic to kill those maturing sperm cells where it is most highly expressed. It would follow that the surviving mature sperm would be precisely those where CidBwMel is not sufficiently expressed to induce either sperm or embryonic death. This model could be tested by assessing if D. melanogaster males expressing CidBwMel alone show reduced sperm production.

Notably, the hypothesis that cidB may be deleterious in various cell types and developmental stages does not imply that the Wolbachia themselves express this gene in many tissues of their native hosts. In other words, the pattern of expression of cidB in transgenic insects says nothing about its natural expression in Wolbachia-infected hosts. The fact that viable uninfected offspring can often be obtained through imperfect Wolbachia transmission or antibiotic curing actually suggests that, in a natural context, the CI toxin is not expressed in all tissues. At present, one cannot exclude a ‘two-by-one’ model, wherein both CidA and CidB proteins would be necessary to produce a toxic effect, but this would imply drastically different effects of CidA in sperm (where it would contribute to toxicity) and in the eggs (where it is known to act as an antidote). In our view, and as discussed above, a model where CidB and CidA act respectively as toxin and antidote is more likely correct, and can be reconciled with the data in hand. As we shall now discuss, comparative genomics of cif genes, at both micro- and macro-evolutionary scales, further support this conclusion [30,34].

CI Evolution

Although C. pipiens provided the original CI model system, the simple pattern presented in Figure 1, which best illustrates the invasiveness of CI, is never seen in natural populations of this species. Wherever they come from, C. pipiens mosquitoes are always infected by Wolbachia (although uninfected specimens can occasionally be found in a cryptic species [40,41]). As a consequence, infected males never encounter uninfected females in nature, and CI is only expressed in its most elaborate form: infected males and females can only produce offspring if they carry ‘compatible infections’. Indeed, C. pipiens has long been known to harbor a large diversity of cross-incompatible mosquito lines [11], which are now known to carry closely related but incompatible Wolbachia strains [42,43]. These are said to be ‘bidirectionally incompatible’ if crossing in both directions results in embryo death. By contrast, crosses between ‘unidirectionally incompatible’ strains produce effective CI in only one direction, producing a pattern similar to that illustrated in Figure 1, although all individuals are infected.

How can this be? That different Wolbachia strains may harbor different compatibility types is easily explained in the framework of the TA model, especially in its lock-and-key formulation: incompatible Wolbachia strains will carry incompatible locks and keys. In this regard, C. pipiens is not unique: Drosophila simulans, among many other species, also carries several distinct Wolbachia strains, each with its own compatibility type [38]. In this fruit fly, compatibility relationships between lines can, at least in theory, be parsimoniously explained by variations at a single TA locus [44] (although some D. simulans Wolbachia genomes appear to include multiple cif paralogs [45]). By contrast, incompatibility patterns are so complex in C. pipiens that they cannot be explained with a single TA pair per Wolbachia genome [42,46]. Specifically, compatibility relationships are not all transitive in this system: two strains may be mutually compatible although they harbor distinct compatibility patterns with other strains [44]. Focusing on compatibility relationships among 19 wild-type C. pipiens lines [43], theoretical analyses grounded in the TA framework concluded that at least five TA pairs may co-occur in one wPip genome [44]. Now that the CI genes have been identified, the time has come to test such theoretical predictions.

Although all infections from C. pipiens represent a monophyletic group of close Wolbachia relatives, fine-scale phylogenetic markers allow one to distinguish five clades within which crosses are most often compatible, and between which they are usually incompatible [42,47]. Based on this phylogenetic and phenotypic diversity, Bonneau et al. [30] selected multiple mosquito lines collected worldwide to assess molecular variation of the cif genes and test their explanatory power with regard to compatibility patterns. Under the hypothesis that these genes underlie CI diversity in Culex, they should be present in several distinct copies within each Wolbachia genome, and strains harboring different CI patterns should carry different cif repertoires. The cid data fully matched these predictions: in the Culex populations studied, cidA and cidB show tremendous variation in both sequence and copy number, resulting in large part from duplication and recombination events, possibly mediated by the prophage region where they occur. By contrast, the cinA and cinB genes were found to be monomorphic in the wPip strains analyzed, indicating that incompatibilities in Culex are the result of cid but not cin variations.

Although mutually incompatible strains should harbor different cid repertoires, as was indeed observed, the TA model does not predict that mutually compatible strains should carry exactly the same cid alleles. First, mutations may occur outside the TA interaction sites, which should not affect compatibility patterns and would thus be neutral as far as CI is concerned. Second, the TA model does not demand a strict one-to-one specificity of TA interactions: some antidotes may inhibit more than one toxin. Both these explanations may contribute to explain why several mutually compatible strains harbor different cid repertoires. Nevertheless, these strains always share a common cidA variant that may represent a superantidote that matches several distinct toxins [30]. Expressing these different Cid variants in an experimentally flexible in vivo system such as yeast, together with biochemical studies, should clarify this issue.

What does the cid polymorphism tell us about the evolutionary process of CI diversification? In other words, can cid molecular variations reveal how bidirectionally incompatible Wolbachia evolved? Past theoretical work has highlighted how much the genetic architecture of CI should affect this process [39,44,48,49]. The experimental confirmation that CI genes can occur in multiple copies [30] greatly simplifies the problem from a theoretical standpoint: following duplication of a TA pair, redundancy between loci may allow new antidotes to emerge without compromising self-compatibility. This first step could be followed by the occurrence of matching mutations of the toxin, producing two distinct CI operons in a genome [44]. The possibility that some antidotes may inhibit more than one toxin opens another possible scenario, where either side may diversify first if the process goes through a broad spectrum phase before further restriction of specificity, as has been suggested in other TA systems [50].

The absence of polymorphism in the cin operon (the nuclease paralog of cid) rules out this locus as a driver of CI diversity in Culex. However, could this operon or other cid paralogs operate in other species? Comparative genomics among Wolbachia lineages indicate that some CI-inducing strains do not contain cid genes, but only cin paralogs [28,34]. Moreover, neither cid- nor cin-related paralogs were found in a close relative of wMel that does not induce CI [34,51], or in nematode Wolbachia strains that have become obligate mutualists [26,34]. These results support the involvement of both cid and cin operons in CI induction by Wolbachia, with evidence still emerging. Further, these two loci so far seem to be sufficient to explain all CI cases associated with Wolbachia.

This conclusion does not hold when symbiont lineages distant from Wolbachia are considered. Notably, Cardinium bacteria can induce CI but do not carry identifiable cid or cin genes, suggesting convergent evolution of CI [34,52]. However, a recent study suggested that TA-like systems showing putative DUB activity can be found in a diverse array of endosymbionts, not only in Cardinium (albeit in a lineage where CI itself was not demonstrated) but also in other intracellular symbionts, such as Rickettsia and Spiroplasma, that are also known as manipulators of host reproduction [36]. Also notable is the presence of cin genes in non-CI but parthenogenesis-inducing Wolbachia strains [34]. Although these results do not provide direct evidence that distant cif homologs are involved in CI or other forms of reproductive manipulation, they make this hypothesis worth exploring. Finally, the discovery of CI associated with a non-Wolbachia Alphaproteobacterium [53] provides another system where cif gene relatives should be sought.

Cui Bono? Levels of Selection and the Origin of CI

From Cicero to the detective Columbo, asking ‘cui bono?’ (who benefits?) has been a useful avenue of criminal and sociological investigation. This question is also relevant in a Darwinian framework and has prompted novel explanations of evolutionary oddities such as altruism and selfish genetic elements [54–56]. Applying this question to CI led early theorists to highlight the benefit that it provides to Wolbachia itself, rather than to its host, suggesting that the bacterium represents the right level of selection to understand how this phenomenon came to be [19]. Remarkably, the sameearly study was visionary in suggesting that the CI genes may be associated with mobile genetic elements: the discovery that they sit in a prophage supported this hypothesis [26–28,34,57]. In our view, this finding also makes it relevant to revisit the question of the adaptive significance of CI,and ask whether this phenomenon may have primarily evolved forthe benefit not of Wolbachia, but of the bacterium’s own intragenomic parasites.

The hypothesis that TA systems, including restriction-modification systems and bacteriocins, constitute fundamentally selfish genetic elements has received ample support in the field of microbial evolution [58–63]. In brief, the idea is that TA systems make themselves addictive as soon as they enter a cell: the toxin molecule is typically more stable than the antidote, such that removing the source of both results in cell death. Although this property is not necessarily invasive (an element killing a host once it is lost increases its effective transmission rate but will not, by itself, increase its frequency), it can promote invasion under some circumstances, especially if the TA system is part of a horizontally transmitted mobile genetic element [64].

With regard to Wolbachia, it seems reasonable to assume that the nearly universal positioning of the CI genes within prophages [57,65] is not mere chance, but instead has some adaptive significance. Who then benefits from the CI genes and, more specifically, from their association with prophages? This particular location is not a priori adaptive at the Wolbachia level, but it may well be at the phage level: horizontally transmitted phages should more readily invade Wolbachia populations if they carry a TA system. The occurrence of distant cif relatives in several other bacterial lineages, where they sit in plasmids rather than in prophages, argues against a purely viral origin of this gene family [36], as does their relatedness to typical eukaryotic sequences [26,36,57]. However, the association of cif genes with phages in the Wolbachia lineage opens the possibility that they first invaded this clade as a phage adaptation, and only later became ‘CI genes’.

As previously pointed out (D. Poinsot, PhD thesis, University Paris 6, 1997), the elimination of Wolbachia from maturing sperm establishes conditions for the evolution of a selfish phage TA system toward genuine CI. If one simply assumes that the toxin is exported outside of the bacterium and can exert its deleterious effects on the host (eukaryotic) cell, then CI could easily arise. In particular, the paternal pronucleus, threatened by a stable toxin, would need fresh antidote from an infected egg to be able to participate in the first embryonic division. Such a situation would in turn make the bacterium invasive through CI, generating a convergence in the evolutionary interests of both the phage and its bacterial host.

Concluding Remarks and Future Perspectives

Recent research has provided a firm answer to the first of many key questions regarding the molecular biology of CI (see Outstanding Questions). There is indeed a general agreement that the principal Wolbachia CI genes have been found [26–29], and our present analysis concurs with past predictions that they encode toxins and antidotes that interact in a lock-and-key fashion [25]. Nevertheless, significant revisions of the basic TA model are necessary to account for all observations. First, we suggest that CifB toxins may exert their deleterious effects not only in incompatible crosses during the first embryonic mitosis but also in maturing sperm and other cell types, in which the presence of CifA antidotes would also be required. This hypothesis would explain why dual transgenic expression of the two genes in uninfected Drosophila males is necessary for them to survive (in the case of cidwPip) or for CI to be transgenically expressed (in the case of cidwMel) [27,28]. The patterns of molecular variation of the cidA and cidB genes [30] also suggest that some antidotes may match several toxin products, a conjecture that could be tested by direct assessments of CidA-B interactions in simplified in vivo or in vitro systems. Furthermore, these genetic data confirm the earlier speculation that single Wolbachia strains may carry multiple active CI operons, not only in Culex [66] but also in Drosophila [67].

Outstanding Questions.

What are the genes behind CI? Do they encode a TA system?

Among the various paralogs of the putative CI genes (cif, for CI factors), are only cid operons (including a DUB toxin) involved in CI, or are those including a nuclease toxin (cin) or toxins combining the two functions (cnd) also involved?

Is CI induced by CifB proteins alone? Why then is CI not recapitulated by sole transgenic expression of the main putative toxin gene (cidB) in Drosophila? Could this be explained by toxic effects of CidB outside the first embryonic division, making the presence of its cognate antidote (CidA) essential for fly survival or CI expression?

How would CifB proteins induce embryo death? What targets are affected by the DUB activity of CidB? Are these in direct interaction with paternal chromosomes, or do they affect upstream regulators of the cell cycle? Do CidB and CinB proteins affect the same pathway?

How do CifA proteins inhibit CifB toxicity without necessarily affecting their enzymatic activity? Could CifB sequestration or relocalization be involved?

Is variation in cid genes, both in copy number and sequence variation, alone able to explain the complex CI patterns in natural populations of the mosquito C. pipiens?

How do mutually incompatible Wolbachia strains evolve? What is the contribution of gene duplication to this process? How specific is the cifA/cifB interaction, and does this vary across cif loci?

Do all CI cases involve cif operons? What are the functions of their numerous distant homologs in other intracellular bacteria?

How did CI evolve? Why are cif genes located in a prophage? Could CI derive from a selfish phage invasion system?

Although the genetics of CI have been clarified, its molecular mechanisms remain to be worked out (Box 2). Furthermore, the exact nature of the interaction between toxin and antidote proteins remains to be determined, even though there are already some indications of which residues might be involved [30]. Clarification of these issues will be necessary to design artificial CI systems that may be used in biological control. Comparative genomics will provide a valuable complement to experiments to understand how CI actually works, and to investigate how it evolves. At a microevolutionary scale, further exploration of the Culex system will clarify how different Wolbachia strains become mutually incompatible. On a macroevolutionary scale, genomic comparisons may further reveal which cif genes can actually induce CI, and what are the commonalities and specificities between these systems.

Box 2. CI Molecular Mechanisms.

Although the CI effectors have been identified, the question of how they induce embryo death or rescue remains largely unanswered, and can be divided in two: how do cif toxins impede paternal chromosomes, and how do cif antidotes impede the toxins? The functional properties of the cifB genes are obviously relevant to the first question, as is characterization of the CI phenotype at the cytological level. The earliest detected abnormality in CI crosses is improper deposition of maternal H3.3 histones on the paternal genome after protamine removal [78]. This deposition defect could be responsible for improper paternal chromosome condensation in prophase [22,79–81]. How could these features be related to cif gene activities? Although bioinformatics predicts several potential enzymatic properties for the products of the various cif paralogs, the DUB domain of CidB stands at the moment as the strongest CI effector candidate: active-site mutations in CidB eliminate CI in transgenic insects as well as toxicity in yeast models [27]. Furthermore, different CidB repertoires induce different levels of CI defects at the cellular level [81]. Although the DUB activity may affect upstream components of the CI causal chain, interference with the ubiquitylation status of key chromatin or cell-cycle regulators is an obvious hypothesis to link CidB to CI cytology.

However, the observation that some Wolbachia strains may lack cid genes but still induce CI suggests the DUB function is only one tool in a larger cif arsenal [26,28,34,36]. CinB appears to be the most likely source of CI in this case because active-site mutations block CinB toxicity in yeast [27]. Even so, why and how would different enzymes generate the same CI phenotype? One hypothesis would be that the DUB and nuclease activities are two upstream components of a common causal chain. Simply put, cutting DNA and cleaving ubiquitin may constitute alternative ways to disturb paternal chromosome condensation. Definitive demonstrations that CinB can induce CI, as well as the identification of the CidB and CinB targets, will be crucial to resolving these issues.

The fact that CI may be mediated by two distinct effectors, involving DUB or nuclease activities, is also relevant to investigating how CI antitoxins may function. CidA and CinA may inhibit DUB and nuclear activities, respectively, either through distinct pathways or alternatively through a single mechanism such as protein sequestration or relocalization. The latter hypothesis may explain why CidA can inhibit the toxicity of CidB without specifically reducing its DUB activity against model substrates [27]. Further characterization of the Cid and Cin protein structures and identification of the residues involved in the interaction between cognate partners of both operons are promising avenues of research to better understand how infected embryos are rescued from CI.

Building on the observation that the CI genes lie in a mobile genetic element (the WO prophage), we suggested they might originally have been selected as a phage invasive strategy and were later domesticated by the bacterium. In line with this hypothesis, distant homologs of the cid genes are present in other bacterial symbionts, and nearly always in association with phages or plasmids [36]. Pushing the reasoning one step further, one may envisage that the TA operon was initially costly for the phage, and only later became domesticated as an effective invasive strategy. CI would then be a case of a parasitic operon within a parasitic phage within a parasitic symbiont, each relying today on its past inner enemy. The observation that some insects, and many filarial nematodes, cannot live without Wolbachia [68–70] reinforces the idea that such ‘evolution through addiction’ constitutes a never-ending process, producing the Russian dolls that all organisms seem to be.

Highlights.

Wolbachia are maternally inherited intracellular bacteria of many Arthropod species. They can invade populations through various strategies including CI, whereby the symbionts protect eggs from the lethal effect of the sperm of infected males.

It has long been proposed that this phenomenon may rely on a toxin deposited by the bacterium before its elimination from maturing sperm, and on an antidote that is provided in an infected egg by the maternal symbiont.

Recent research toward the molecular basis of CI has turned the spotlight on two syntenic loci in a prophage region which recapitulate the CI phenotype and are organized in a typical TA fashion.

This genetic architecture, that is archetypal of TA systems that promote the spread of selfish mobile elements in free-living bacteria, provides clues to the possible evolutionary origin of CI.

Acknowledgments

This work benefited from funding by the US Department of Agriculture (grant USDA-1015922 to J.B.), the National Institutes of Health (grant GM046904 to M.H.), and the French Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR: CIAWOL grant to M.S., ANR-16-CE02-0006-01; HORIZON grant to S.C., ANR-17-CE02-0021-02).

References

- 1.Moran NA (2006) Symbiosis. Curr. Biol 16, R866–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kirkness EF et al. (2010) Genome sequences of the human body louse and its primary endosymbiont provide insights into the permanent parasitic lifestyle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 107, 12168–12173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hurst GDD and Crystal L (2015) Reproductive parasitism: maternally inherited symbionts in a biparental world. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect Biol. 7, a017699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Charlat S et al. (2003) Evolutionary consequences of Wolbachia infections. Trends Genet. 19, 217–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Werren JH et al. (2008) Wolbachia: master manipulators of invertebrate biology. Nat. Rev. Microbiol 6, 741–751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weinert LA et al. (2015) The incidence of bacterial endosym-bionts in terrestrial arthropods. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci 282, 20150249–20150249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bailly-Bechet M et al. (2017) How long does Wolbachia remain on board? Mol. Biol. Evol 34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hertig M and Wolbach SB (1924) Studies on Rickettsia-like microorganisms in insects. J. Med. Res 44, 329–374 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marshall JF (1938) The British Mosquitoes, British Museum [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roubaud E (1941) Phénomènes d’amixie dans les intercroisements de culicides du groupe pipiens. Comptes Rendus l’Aca-demie des Sci. Paris 212, 257–259 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laven H (1951) Crossing experiments with Culex strains. Evolution 5, 370–375 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yen JH and Barr AR (1971) New hypothesis of the cause of cytoplasmic incompatibility in Culexpipiens L. Nature 232,657–658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yen JH and Barr AR (1973) The etiological agent of cytoplasmic incompatibility in Culex pipiens. J. Invertebr. Pathol 22, 242–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Caspari E and Watson GS (1959) On the evolutionary importance of cytoplasmic sterility in mosquitoes. Evolution (N. Y.) 13, 568–570 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fine PEM (1978) On the dynamics of symbiont-dependent cytoplasmic incompatibility in culicine mosquitoes. J. Invertebr. Pathol 30, 10–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoffmann AA et al. (1986) Unidirectional incompatibility between populations of Drosophila simulans. Evolution 40, 692–701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Turelli M and Hoffmann AA (1995) Cytoplasmic incompatibility in Drosophila simulans: dynamics and parameter estimates from natural populations. Genetics 140, 1319–1338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Werren JH (1997) Biology of Wolbachia. Annu. Rev. Entomol 42, 587–609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hurst LD (1991)The evolution of cytoplasmic incompatibility or when spite can be successful. J. Theor. Biol 148, 269–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Breeuwer JA and Werren JH (1990) Microorganisms associated with chromosome destruction and reproductive isolation between two insect species. Nature 346, 558–560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kose H and Karr TL (1995) Organization of Wolbachia pipientis in the Drosophila fertilized egg and embryo revealed by an anti-Wolbachia monoclonal antibody. Mech. Dev 51, 275–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Callaini G et al. (1997) Wolbachia-induced delay of paternal chromatin condensation does not prevent maternal chromosomes from entering anaphase in incompatible crosses of Drosophila simulans. J. Cell Sci 110, 271–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Merçot H and Poinsot D (1998) [Rescuing Wolbachia have been overlooked] … and discovered on Mount Kilimanjaro. Nature 391, 853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bourtzis K et al. (1998) Rescuing Wolbachia have been overlooked. Nature 391, 852–853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Poinsot D et al. (2003) On the mechanism of Wolbachia-induced cytoplasmic incompatibility: confronting the models with the facts. BioEssays 25, 259–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beckmann JF and Fallon AM (2013) Detection of the Wolbachia protein WPIP0282 in mosquito spermathecae: implications for cytoplasmic incompatibility. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol 43, 867–878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beckmann JF et al. (2017)A Wolbachia deubiquitylating enzyme induces cytoplasmic incompatibility. Nat. Microbiol 2, 17007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.LePage DP et al. (2017) Prophage WO genes recapitulate and enhance Wolbachia-induced cytoplasmic incompatibility. Nature 543, 243–247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shropshire JD et al. (2018) One prophage WO gene rescues cytoplasmic incompatibility in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 115, 4987–4991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bonneau M et al. (2018) Culex pipiens crossing type diversity is governed by an amplified and polymorphic operon of Wolbachia. Nat. Commun 9, 319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karr TL (2007) Fruit flies and the sperm proteome. Hum. Mol. Genet 16, R124–R133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wasbrough ER et al. (2010) The Drosophila melanogaster sperm proteome-II (DmSP-II). J. Proteomics 73, 2171–2185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yamaguchi Y et al. (2011) Toxin-antitoxin systems in bacteria and archaea. Annu. Rev. Genet 45, 61–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lindsey ARI et al. (2018) Evolutionary genetics of cytoplasmic incompatibility genes cifA and cifB in prophage WO of Wolbachia. Genome Biol. Evol 10, 434–451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Güell M et al. (2011) Bacterial transcriptomics: what is beyond the RNA horizome? Nat. Rev. Microbiol 9, 658–669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gillespie JJ et al. (2018) A tangled web: origins of reproductive parasitism. Genome Biol. Evol 10, 2292–2309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Poinsot D et al. (1998) Wolbachia transfer from Drosophila melanogaster into D. simulans: host effect and cytoplasmic incompatibility relationships. Genetics 150, 227–237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Merçot H and Charlat S (2004) Wolbachia infections in Drosophila melanogaster and D. simulans: polymorphism and levels of cytoplasmic incompatibility. Genetica 120, 51–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Turelli M (1994) Evolution of incompatibility-inducing microbes and their hosts. Evolution 48, 1500–1513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rasgon JL and Scott TW (2003) Wolbachia and cytoplasmic incompatibility in the California Culex pipiens mosquito species complex: parameter estimates and infection dynamics in natural populations. Genetics 165, 2029–2038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dumas E et al. (2016) Molecular data reveal a cryptic species within the Culex pipiens mosquito complex. Insect Mol. Biol 25, 800–809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Atyame CMCM et al. (2014) Wolbachia divergence and the evolution of cytoplasmic incompatibility in Culex pipiens. PLoS One 9, e87336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Duron O et al. (2006) Tracking factors modulating cytoplasmic incompatibilities in the mosquito Culex pipiens. Mol. Ecol 15, 3061–3071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nor I et al. (2013) On the genetic architecture of cytoplasmic incompatibility: inference from phenotypic data. Am. Nat 182, E15–E24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Turelli M et al. (2018) Rapid global spread ofwRi-like Wolbachia across multiple Drosophila. Curr. Biol 28, 963–971.e8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Atyame CM et al. (2011) Multiple Wolbachia determinants control the evolution of cytoplasmic incompatibilities in Culex pipiens mosquito populations. Mol. Ecol 20, 286–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Atyame CM et al. (2011) Diversification of Wolbachia endosymbiont in the Culex pipiens mosquito. Mol. Biol. Evol 28, 2761–2772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Charlat S et al. (2001) On the mod resc model and the evolution of Wolbachia compatibility types. Genetics 159, 1415–1422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Charlat S et al. (2005) Exploring the evolution of Wolbachia compatibility types: a simulation approach. Genetics 170, 495–507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Aakre CD et al. (2015) Evolving new protein-protein interaction specificity through promiscuous intermediates. Cell 163,594–606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sutton ER et al. (2014) Comparative genome analysis of Wolbachia strain wAu. BMC Genomics 15, 928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Penz T et al. (2012) Comparative genomics suggests an independent origin of cytoplasmic incompatibility in Cardinium hertigii. PLoS Genet. 8, e1003012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Takano S et al. (2017) Unique clade of alphaproteobacterial endosymbionts induces complete cytoplasmic incompatibility in the coconut beetle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 114, 6110–6115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Burt A and Trivers R (2006) Genes in Conflict: The Biology of Selfish Genetic Elements, Belknap Press [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hamilton WD (1963) The evolution of altruistic behavior. Am. Nat 97, 354–356 [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hickey DA (1982) Selfish DNA: a sexually-transmitted nuclear parasite. Genetics 101, 519–531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bordenstein SR and Bordenstein SR (2016) Eukaryotic association module in phage WO genomes from Wolbachia. Nat. Commun 7, 1–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Van Melderen L and De Bast MS (2009) Bacterial toxin-anti-toxin systems: more than selfish entities? PLoS Genet. 5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kobayashi I (2001) Behavior of restriction-modification systems as selfish mobile elements and their impact on genome evolution. Nucleic Acids Res. 29, 3742–3756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mruk I and Kobayashi I (2014) To be or not to be: regulation of restriction-modification systems and other toxin-antitoxin systems. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, 70–86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Inglis RF et al. (2013) The role of bacteriocins as selfish genetic elements. Biol. Lett 9, 8–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rankin DJ et al. (2011) What traits are carried on mobile genetic elements, and why. Heredity 106, 1–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kusano K et al. (1995) Restriction-modification systems as genomic parasites in competition for specific sequences. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 92, 11095–11099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rankin DJ et al. (2012) The coevolution of toxin and antitoxin genes drives the dynamics of bacterial addiction complexes and intragenomic conflict. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci 279, 3706–3715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Klasson L et al. (2008) Genome evolution of Wolbachia strain wPip from the Culex pipiens group. Mol. Biol. Evol 25, 1877–1887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Atyame CM et al. (2011) Multiple Wolbachia determinants control the evolution of cytoplasmic incompatibilities in Culex pipiens mosquito populations. Mol. Ecol 20, 286–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zabalou S et al. (2008) Multiple rescue factors within a Wolbachia strain. Genetics 178, 2145–2160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dedeine F et al. (2001) Removing symbiotic Wolbachia bacteria specifically inhibits oogenesis in a parasitic wasp. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 98, 6247–6252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hosokawa T et al. (2010) Wolbachia as a bacteriocyte-associated nutritional mutualist. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 107, 769–774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Taylor MJ et al. (2005) Wolbachia bacterial endosymbionts of filarial nematodes. Adv. Parasitol 60, 245–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.O’Neill SL et al. (1997) Influential Passengers: Inherited Micro-organisms and Arthropod Reproduction, Oxford University Press [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fenton A et al. (2011) Solving the Wolbachia paradox: modeling the tripartite interaction between host, Wolbachia, and a natural enemy. Am. Nat 178, 333–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Teixeira L et al. (2008) The bacterial symbiont Wolbachia induces resistance to RNA viral infections in Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS Biol. 6, 2753–2763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Moreira LA et al. (2009) A Wolbachia symbiont in Aedes aegypti limits infection with dengue, chikungunya, and Plasmodium. Cell 139, 1268–1278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Flores HA and O’Neill SL (2018) Controlling vector-borne diseases by releasing modified mosquitoes. Nat. Rev. Microbiol 16, 508–518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Vavre F and Charlat S (2012) Making (good) use of Wolbachia: what the models say. Curr. Opin. Microbiol 15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kamtchum-Tatuene J et al. (2017) The potential role of Wolbachia in controlling the transmission of emerging human arboviral infections. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis 30, 108–116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Landmann F et al. (2009) Wolbachia-mediated cytoplasmic incompatibility is associated with impaired histone deposition in the male pronucleus. PLoS Pathog. 5, e1000343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Reed KM and Werren JH (1995) Induction of paternal genome loss by the paternal-sex-ratio chromosome and cytoplasmic incompatibility bacteria (Wolbachia): a comparative study of early embryonic events. Mol. Reprod. Dev 40, 408–418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ryan SL and Saul GB (1968) Post-fertilization effect of incompatibility factors in Mormoniella. Mol. Gen. Genet 103, 29–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bonneau M et al. (2018) The cellular phenotype of cytoplasmic incompatibility in Culex pipiens in the light of cidB diversity. PLoS Pathog. 14, e1007364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Pontier SM and Schweisguth F (2015) A Wolbachia-sensitive communication between male and female pupae controls gamete compatibility in Drosophila. Curr. Biol 25, 1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Jacquet A et al. (2017) Does pupal communication influence Wolbachia-med’iated cytoplasmic incompatibility? Curr. Biol 27, R53–R55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]