Abstract

While smoking cessation leads to significant improvements in both mortality and morbidity, post-cessation weight gain partially attenuates this benefit. Even though post-cessation weight gain is small (4.7 kg on average), it is a stated reason to delay cessation attempts and is associated with smoking relapse. Fit & Quit is a randomized, controlled efficacy trial that aims to examine the ability of a weight stability intervention and a weight loss intervention to reduce post-cessation weight gain. For this purpose, Fit & Quit will randomize participants to three conditions: (a) Small Changes, a weight gain prevention intervention; (b) Look AHEAD Intensive Lifestyle Intervention; and (c) a lower-intensity bibliotherapy intervention. All conditions will receive a highly efficacious behavioral (i.e., rate reduction skills, motivational interviewing) and pharmacological (i.e., varenicline) smoking cessation program. A total of 400 participants will be recruited and randomized to the three interventions. Participants will be recruited in waves, with 10 waves of approximately 40 participants per wave. The primary outcomes of this study include post-cessation weight gain and cessation status at 12-month follow-up. Fit & Quit will integrate and adapt the strongest evidence-based interventions available for weight management and smoking cessation. Fit & Quit is highly innovative in the areas of the target population, study design, and use of technology. For these reasons, we expect that Fit & Quit will make a significant public health contribution to curtailing the important cessation barrier of post-cessation weight gain.

Keywords: Post-cessation weight gain, smoking cessation, randomized efficacy trial, weight gain prevention, weight loss

Introduction

While smoking cessation leads to significant improvements in both mortality and morbidity,1–4 post-cessation weight gain partially attenuates this benefit as it may affect blood pressure and glucose metabolism.5,6 Smoking cessation is accompanied by 4.7 kg average weight gain 12 months after quitting.7 Even when this weight gain may be considered moderate, concerns about post-cessation weight gain are common among smokers and are often cited as a reason to delay cessation attempts.8,9 Notably, post-cessation weight gain is associated with smoking relapse.8–10 Although the health benefits of smoking cessation greatly outweigh the negative impact of post-cessation weight gain, efficacious intervention “packages” that would not require people to choose between smoking cessation and nontrivial weight gain could minimize this important barrier to smoking abstinence.

Weight management programs in conjunction with smoking cessation have demonstrated modest initial success but they have not found long-term weight maintenance (e.g., at 12 months), have been restricted to women, and have not included diverse samples or reported rates of racial and ethnic minority groups.11–14 Much like weight maintenance after weight loss, weight maintenance after smoking cessation is also difficult to achieve.11,15 However, a randomized controlled trial investigating weight gain prevention found that participants who received an intervention focusing on making small changes (e.g., reducing 100 calories per day, adding 2000 steps per day) lost significantly more weight at the 12-month follow-up period relative to a psychoeducational condition.16,17 Given these positive results, a small changes weight gain prevention approach before cessation may be beneficial for individuals who are planning to quit smoking and are, thus, at high risk for weight gain.

While a weight stability intervention is one possible approach, another promising option is to induce weight loss prior to smoking cessation to offset post-cessation weight gain. The Look AHEAD Intensive Lifestyle Intervention (ILI), which has produced clinically significant long-term weight loss,18 could help in the development of an effective weight loss intervention for people who quit smoking. Thus, we sought to investigate whether a weight gain prevention intervention or a weight loss intervention, both followed by a smoking cessation intervention, are efficacious in reducing post-cessation weight gain.

Given the negative health implications of weight gain after smoking cessation and the difficulty in reducing post-cessation weight gain in previous interventions, we will determine the efficacy of a weight gain prevention intervention,17 a weight loss intervention,19 and a bibliotherapy intervention20 on preventing post-cessation weight gain at 12-month follow-up. All conditions will receive behavioral and pharmacological smoking cessation treatments. Pharmacotherapy will include 6 months of varenicline (Chantix™), a medication that has demonstrated comparable effectiveness rates to nicotine replacement therapy, continuous abstinence rates of 44% during treatment, and prolonged abstinence rates of 22% at 1-year follow-up.21–24 We hypothesize that participants in all weight management conditions will achieve similar cessation rates. We also hypothesize that participants on the weight gain prevention and weight loss conditions will have significantly lower post-cessation weight gain at 12-month follow-up compared to bibliotherapy, a minimal intervention condition.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

The University of Tennessee Health Science Center Institutional Review Board provided approval to conduct this study. We will conduct a randomized, controlled efficacy trial to examine the ability of a weight gain prevention intervention and a weight loss intervention to reduce post-cessation weight gain. We will randomize participants to three conditions: (a) a small changes weight gain prevention intervention (SMALL), (b) a weight loss intervention (LOSS), and (c) bibliotherapy, a minimal intervention condition (BIBLIO). All three conditions will receive an efficacious smoking cessation program and 6 months of varenicline pharmacotherapy (Chantix™). In addition, those participants randomized to the SMALL and LOSS conditions will receive monthly booster weight management sessions after completing the smoking cessation intervention.

Participant contact will occur both in person and over the phone. Enrollment, randomization, and periodic assessments will occur in person, whereas all counseling sessions will occur over the telephone in group format. Procedures for each of the types of contact are described below.

Participants

Based on an a priori power analysis (see “Power Analysis” section), a total of 400 participants will be recruited for this randomized, controlled efficacy trial.

Inclusion Criteria.

Participants recruited for the randomized, controlled efficacy trial must wish to quit smoking within the next 30 days, have smoked five or more cigarettes a day for at least 1 year, be 18 years of age or older, have a BMI of 22 kg/m2 or greater, have daily access to a phone and email, have willingness to use phone minutes for weekly session calls, speak English, live within 45 minutes of the data collection sites (two sites located ~ 30 minutes apart from each other), and be able to exercise for at least 10 minutes a day.

Exclusion Criteria.

Potential participants will be excluded if they have a known allergy or hypersensitivity to varenicline; are currently (i.e., in the previous 30 days) participating in other behavioral or pharmacologic weight or smoking cessation interventions; have had weight loss surgery; have lost ≥ 10 lbs. in the past 6 months; have used an investigational drug within the last 30 days; have self-reported current depression based upon the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale - Revised (CESD-R ≥ 16);25 have current suicidal thoughts or have a lifetime history of a suicide attempt as defined by the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS);26 have a history of psychosis, bipolar disorder, cancer, or anorexia nervosa; have current alcohol abuse or illicit substance use; have kidney disease, HIV, or unstable cardiovascular conditions; have another member of their household already participating in this study; plan to move from the area in the following year; have blood pressure ≥ 150/95, heart rate < 40 bpm and > 120 bpm, and weigh > 385 lbs. (due to the upper weight limit on the e-scales provided to the participants). All women of childbearing age must not be pregnant or breastfeeding, must have a negative pregnancy test, and must agree to use contraception during participation in the study (i.e., 12 months). Participants must also be willing to be randomized to the study conditions and wait 8 weeks prior to beginning smoking cessation (during which they will participate in the weight management intervention to which they are assigned).

Recruitment, Screening, and Baseline Visit

Recruitment will be multi-faceted. Strategies will be both traditional (e.g., flyers, business cards, postcards, posters, recruitment through medical referrals, radio, and local media advertising) and electronic (e.g., institution emails, electronic advertisements on Facebook). Sites for recruitment will include local universities and colleges, local physician and dentist offices, barbershops, police stations, fire department stations, and community resource websites. In addition, recruitment will include a “refer a friend” incentive where participants can refer up to 10 friends to the study. Each randomized friend will earn the referrer $10 in incentives (i.e., Amazon gift certificates). Importantly, we plan to strategically advertise to ensure that we do not have a large influx of candidates for the study at any one time. We will utilize periodic advertising to fill groups, followed by a lull while groups are initiated, then another advertising period. A large and consistent influx may work against recruitment, as we would not be able to enroll all potential participants immediately. Thus, our recruitment plan is to “trickle” advertisements on a periodic basis to allow us to fill groups at specific recruitment periods.

Interested individuals will be directed from our recruitment materials to call the study phone number to learn more and determine whether they meet the preliminary eligibility criteria. Individuals who meet the phone screening eligibility criteria will be invited to schedule an in-person screening visit, during which written informed consent will be obtained, eligibility will be determined, self-report measures will be administrated, and physical measures will be collected. In addition, participants will receive a paper copy of a diet and exercise journal (with instructions to complete for the 3 days prior to baseline visit as a behavioral run-in), instructions to friend Fit & Quit on Facebook (as a method for staying in touch with the participant should they move or change their phone number), instructions to acquire physician clearance to participate, and an appointment for a baseline visit. During this in-person baseline visit, participants must turn in the diet and exercise journal (with complete information for 3 days prior to baseline visit) and the physician clearance letter. We will recruit in waves, with 10 waves of approximately 40 participants per wave (16 participants randomized to the SMALL condition, 16 randomized to the LOSS condition, and 8 randomized to the BIBLIO condition).

Randomization

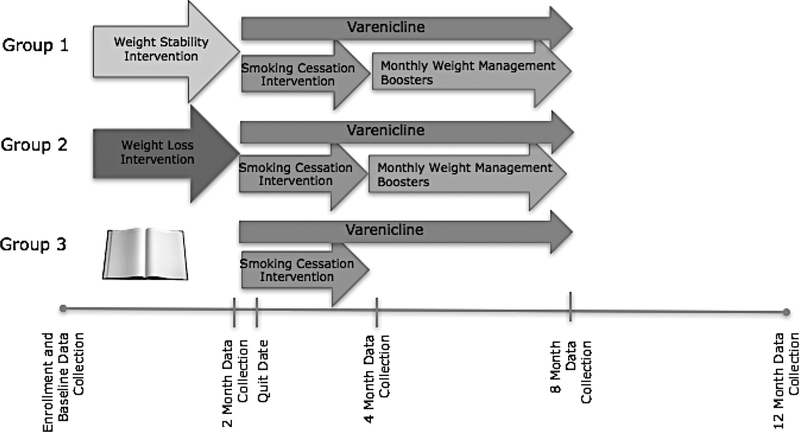

When each wave has been sufficiently filled, participants will be invited to an in-person randomization visit where they will be randomly allocated to one of the three conditions (see Figure 1). Randomization will be conducted using a custom SAS randomization algorithm with a sequence blocked by baseline weight category (normal weight, overweight, obese) and gender in order to ensure equal distribution by condition. Participants will be assigned in a ratio of 2 (SMALL condition, n = 160): 2 (LOSS condition, n = 160): 1 (BIBLIO condition, n = 80), for two reasons. First, this will increase the likelihood that participants will receive an intensive intervention while still having a minimal intervention group available for comparison without significant loss of power or detectable effect size. Second, given the novelty of the active intervention arms, we will increase the precision of our estimated outcomes, which will inform future research. After randomization, all participants will meet their interventionists in an individual meeting, where they will be provided a BodyTrace™ e-scale with instructions as well as group-specific intervention materials. Specifically, SMALL participants will receive a Fitbit Alta activity tracker. LOSS participants will receive their tailored diet and exercise goals, self-monitoring instructions, meal replacements for 8 weeks (e.g., Slim Fast, oatmeal, protein bars), a Fitbit Alta activity tracker, and measuring cups. BIBLIO participants will receive the EatingWell Diet® book.20

Figure 1.

Study design and general timeline for Fit & Quit.

Retention

We will employ a proactive approach to retention that will include flexible appointments, maintaining current contact information, minimizing barriers to in-person assessment visits (e.g., conducting assessments at participants’ homes or at neutral locations), problem-solving barriers to phone sessions, session and assessment reminders (via phone, text, mail, email, and Facebook), and setting explicit session expectations (e.g., attending at least 75% of group phone sessions). Also, we will provide small but meaningful incentives. For example, all participants will receive an email with an Amazon gift card at 4- ($30), 8- ($35), and 12-month ($35) assessments. Because all participants will be receiving free varenicline at the 2-month assessment, they will not receive a gift card for this visit. Participants in the SMALL condition will receive a small weekly reward (< $2) during weight management and smoking cessation sessions and monthly during booster sessions if they maintain their weight (i.e., no more than 1.4 kg above baseline), consistent with previous research.17 Weekly staff meetings, which will include retention as a standing agenda item, will also be a component of this systematic and comprehensive approach. Based on previous retention experience, we project 10 to 15% attrition at 12-month follow-up in this study.

Power Analysis

A power analysis was conducted to determine the sample size and detectable effects for this study. Based on previous research, post-cessation weight gain at 12 months estimates are 4.7 kg without intervention.7 Group sample sizes in SMALL (n = 160), LOSS (n = 160), and BIBLIO (n = 80) conditions would achieve 80% power to reject the null hypothesis of equal means when the population mean difference is 5 kg (SD = 13), and with p = .05 using a simple general linear model. This corresponds to a medium effect size of 0.38,27 and the exact p < .01. With the uneven randomization scheme of 2:2:1 (described in “Randomization” section), we would have 80% power to detect a minimal difference of at least 18% in the smoking abstinence rate between the groups, under the assumption that the BIBLIO arm has a 30% abstinence rate,28 using a χ2 test at p = .05. All of the power calculations were done with PASS12.29

Intervention Conditions

Small Changes Weight Gain Prevention (SMALL).

This intervention will be based on the Small Changes intervention protocol from the Study of Novel Approaches to Weight Gain Prevention (SNAP).17 Eight weekly sessions will be completed over the phone in group format. Each session will last approximately 60 minutes. The primary goal will be to train participants in self-regulation for dietary behaviors and physical activity to prevent weight gain. Participants will be asked to make small behavioral changes to their diet and physical activity during the first 8 weeks of the study and, if they gain or lose too much weight, we will work with participants to return to their baseline weight. Participants will receive electronic documents of the lesson materials before each session. Self-regulation skills will be embedded in this treatment: (a) daily weighing to monitor changes; (b) detecting small weight changes using a graph indicating red (i.e., weight ranges requiring more than one small change), yellow (i.e., weight ranges requiring one small change), and green (i.e., optimal weight of ± 2 lbs. of baseline weight) zones; (c) using problem-solving to implement strategies that deal with weight changes; (d) evaluating the success of these strategies; and (e) reinforcing successful weight maintenance. As frequent weighing is a key component to weight management programs,30 participants will be encouraged to engage in daily weight self-monitoring on the BodyTrace™ e-scale (http://www.bodytrace.com) given at baseline. Each time a participant weighs, the e-scale will upload the data automatically to a secure database, so that timely tailored feedback on weighing frequency and progress can be provided by the interventionist through email. The interventionists will also monitor daily self-weighing and daily small changes as a measure of treatment engagement (coded each day as present or absent).

Session 1 will focus on making small changes. The interventionist will discuss how to minimize post-cessation weight gain by making small dietary (i.e., 100 calorie reductions per day) and physical activity changes (i.e., increasing the number of daily steps by 2000 to 3000 steps). Session 2 will focus on increasing physical activity. The interventionist will discuss small changes in physical activity that can help participants to prevent weight gain (e.g., taking the stairs, walking, cleaning, and using Fitbit trackers and app). Session 3 will focus on portion control. The interventionist will discuss strategies to facilitate portion control (e.g., measuring portions and substituting current foods with healthier foods) and portion reduction (e.g., leaving food on plate). Session 4 will focus on balancing calorie intake. The interventionist will discuss the caloric density of different food types (e.g., fat vs. carbohydrates) and the importance of reading nutrition fact labels (e.g., serving size, calories, and % of calories from fat) to make dietary decisions that can help participants achieve their goals. Session 5 will focus on goal setting. The interventionist will review the characteristics of helpful goals (i.e., positive, specific, under participant’s control, time-limited, and achievable) and will guide participants in generating helpful goals relevant to weight gain prevention. Session 6 will focus on eating out. The interventionist will discuss strategies when eating out (e.g., planning ahead, using assertive communication, asking for substitutions, and requesting smaller portions) that can help participants achieve their goals. Session 7 will focus on liquid calories. The interventionist will review a few examples of beverages and their caloric content and will discuss strategies to replace, reduce, and eliminate liquid calories. Session 8 will focus on problem-solving. The interventionist will teach and facilitate problem-solving skills (e.g., describing the problem, brainstorming solutions, and testing useful solutions) to overcome barriers when making small changes.

Weight Loss (LOSS).

This intervention is based on the Look AHEAD ILI.19 Eight weekly sessions will be completed over the phone in group format. Each session will last approximately 60 minutes. The primary intervention goal will be to achieve a weight loss goal of at least 5% of their baseline weight by week 8.31 Participants will first receive tailored calorie and fat goals based on their baseline weight.19 Then, participants will be encouraged to engage in daily dietary and physical activity self-monitoring using MyFitnessPal website or app, as electronic tools facilitate self-monitoring.32 The self-monitoring diaries will be used to assist participants in mastering dietary and physical activity skills during the course of 8 weeks. The interventionist will review the diaries weekly, provide tailored email feedback to reinforce or shape new behaviors,33 and identify high-risk situations for problem-solving. Diet and physical activity self-monitoring will be examined by the interventionist. For each day, participants will receive a dichotomous code for “did not self-monitor” (0) or “self-monitored at least one item” (1), consistent with a previous study.34 Like the participants in the SMALL condition, participants will be given a BodyTrace™ e-scale at baseline and will be asked to weigh themselves daily. The interventionist will also monitor daily self-weighing as a measure of treatment engagement (coded each day as present or absent). In addition, lesson materials for each session will be drawn from Look AHEAD ILI and will cover core concepts of weight management (e.g., self-monitoring, exercise, portion size estimation, stress management, stimulus control, goal setting, and problem-solving). Moreover, meal replacements will be provided to participants for 8 weeks as a method to achieve the study’s calorie and fat goals and as a strategy to control portions. Participants will be encouraged to replace two meals (e.g., breakfast and lunch) and will be advised to consume a third meal of conventional foods as well as additional fruits and vegetables until they reach their daily caloric goals. Based on Look AHEAD ILI materials, participants will also be provided with detailed meal plans that include specific portions and calories. Participants will be advised to use these meal plans as guidance for their third conventional meal or for all meals if they refuse meal replacements at any point. We will use commercially-available meal replacements (i.e., Slim Fast, Special K Protein Bar, and Better Oats oatmeal). With an eye toward future dissemination, we have selected commercially-available meals that could be a cost-effective intervention strategy. Based on dietary self-monitoring, interventionists will code daily meal replacement consumption from 0 to 3 meal replacements consumed to measure treatment engagement. Last, participants will be provided with graded physical activity goals to reach the goal of at least 175 minutes of moderate intensity exercise (e.g., brisk walking) per week or 10,000 steps per day, similar to physical activity goals set in a previous weight management trial with smokers.12,19 Research has shown that smokers can significantly increase their physical activity goals to 10,000 steps per day with the use of a pedometer.35–37 Thus, participants will be provided with Fitbit Alta pedometers to self-monitor their steps, consistent with the Look AHEAD ILI protocol.19 Notably, the Fitbit Alta syncs with the MyFitnessPal smartphone app.

Session 1 will focus on weight loss. The interventionist will discuss how to minimize post-cessation weight gain by consuming 1200 to 1800 calories per day (based on baseline weight) and slowly increasing up to 175 minutes per week of moderate physical activity (~ 10,000 steps per day) to lose 5% (~ 10 lbs.) of baseline weight. Session 2 will focus on calorie intake. The interventionist will explain how many calories per week are required for specific weight loss (e.g., cutting 3,500 calories per week accounts for 1 lb. of weight loss) and will explore strategies to track calorie intake (e.g., measuring foods, eating less than 30% of total calories from fat, and reading nutrition fact labels). Session 3 will focus on increasing physical activity. The interventionist will discuss principles to increase physical activity that can help participants reach their goals (e.g., exercising at least five days per week for at least 10 minutes). Session 4 will focus on goal setting. The interventionist will guide participants in generating helpful goals (i.e., positive, specific, under participant’s control, time-limited, and achievable). Session 5 will focus on being active. The interventionist will elicit barriers, and brainstorm solutions, to being active and will facilitate discussion on how to safely engage in structured physical activity. Session 6 will focus on eating out. The interventionist will discuss strategies when eating out (e.g., planning ahead, asking for substitutions, and requesting smaller portions) and how to use assertive communication when ordering food at restaurants. Session 7 will focus on problem-solving. The interventionist will teach and facilitate problem-solving skills (e.g., describing the problem, brainstorming solutions, and testing useful solutions) to overcome barriers when making dietary and physical activity changes. Session 8 will focus on relapse prevention. The interventionist will review common high-risk situations for diet and exercise slips (e.g., negative emotions and social events), will elicit specific high-risk situations from participants, and will provide strategies to continue behavioral changes (e.g., practicing coping and problem-solving, setting a weight increase limit, and having an action plan if a relapse occurs).

Bibliotherapy (BIBLIO).

Participants randomized to the BIBLIO condition will wait for 8 weeks before initiating the same smoking cessation intervention as the other two conditions. At the baseline visit, participants will receive The EatingWell® Diet book,20 as a minimal intervention that will provide information regarding weight management. This book includes seven self-guided steps for weight loss that are based on the VTtrim weight loss program as well as healthy recipes. We chose to not have a “pure” control group because smokers gain nontrivial amounts of weight when they quit smoking.7 Given the expense and participant burden of the two other conditions, the benefits would need to exceed the effects of bibliotherapy to warrant dissemination. The book has high face validity and the strategies outlined are based on solid empirical literature. Similar to the other conditions, participants will be given a BodyTrace™ e-scale at baseline and will be asked to weigh themselves daily. However, they will not receive interventionist feedback about their weighing frequency or weight trajectory. Nonetheless, data will be collected on daily self-weighing as a measure of treatment engagement (coded each day as present or absent).

Smoking Cessation.

Participants in all conditions will get 6 sessions of a highly efficacious, telephonic smoking cessation intervention that will be delivered in a group setting.38–40 Participants will also get one individual over-the-phone session during the third week (i.e., the week the participant is quitting smoking) to assist in problem-solving. Each session will last approximately 60 minutes. Varenicline use will begin immediately after the first session of smoking cessation as recommended in previous research.21

Participants will transition to the smoking cessation intervention at week 9; they will remain in the same group with whom they received the weight management intervention (or begin attending their group for the BIBLIO condition) in order to preserve group social support and reduce contamination. Our smoking cessation intervention will incorporate three distinct phases that follow the Clinical Practice Guidelines recommendations.41 During the first phase we will prepare participants for the quitting process (sessions 1 and 2). The second phase is the actual quitting process and getting through the first several days of being a non-smoker (sessions 3 and 4). In the third phase, we will discuss relapse prevention strategies (sessions 5 and 6). All sessions will use the 5Rs model to increase participants’ motivation to quit smoking.41 During this discussion, the interventionist will elicit: (a) reasons for participants to quit smoking, (b) risks or negative consequences of smoking, (c) rewards or benefits of quitting smoking, (d) roadblocks or barriers to quitting smoking, and (e) repetition or previous quit attempts and how a new quit attempt could be different. Then, the topic of the session will be discussed and, at the end, the interventionist will suggest participants to set a goal to reduce smoking by 25% until the participant has quit smoking.

Session 1 will focus on rate reduction. The interventionist will discuss a series of empirically-based rate reduction skills (e.g., changing cigarette brand, self-monitoring, and decreasing the amount of nicotine dose from cigarettes).42,43 Session 2 will introduce the topic of preparing for quitting. The interventionist will discuss strategies to disrupt smoking triggers (e.g., delaying the first cigarette, avoiding triggering situations, and limiting the access to cigarettes) and will request all participants to provide a quit date. Session 3 will focus on participants’ quit attempts. The interventionist will discuss removing and dealing with triggers (i.e., avoiding high-risk situations, anticipating triggers, using distraction). Session 4 will focus on staying quit. The interventionist will discuss the health benefits that accumulate over time after cessation (based on standard materials from https://smokefree.gov). Session 5 will focus on short-term relapse prevention. The interventionist will discuss successes, useful skills in maintaining cessation, and challenges experienced by participants. The interventionist will facilitate problem-solving to address these challenges. Session 6 will focus on long-term relapse prevention. The interventionist will aid in the completion of individualized relapse prevention plans.

Varenicline.

All participants will receive varenicline (Chantix™) prior to the start of the smoking cessation intervention so that use can commence immediately after the first smoking cessation session. The efficacy of varenicline as a smoking cessation aid exceeds that of nicotine replacement therapy (OR = 1.57, 95% CI: 1.29 to 1.91) and bupropion (OR = 1.59, 95% CI: 1.29 to 1.96).22 Notably, Tonstad et al. found continuous abstinence rates of 70% after 6 months of varenicline.23 Therefore, to increase the likelihood of cessation maintenance over time, all participants will receive varenicline 0.5 mg once daily for 3 days, increasing to 0.5 mg twice daily for days 4 to 7, and then to the maintenance dose of 1 mg twice daily for a total of 6 months of treatment. Varenicline is minimally metabolized by the liver and 92% is excreted by the kidney, unchanged. Moreover, varenicline has no significant drug interactions.

We will carefully monitor mood changes, adverse events, and serious adverse events. Consistent with FDA recommendations, participants will be encouraged to reduce their alcohol intake while taking varenicline.44 However, it should be emphasized that recent studies, including a large meta-analysis of all phase II, III, and IV trials, showed no increased risk of psychiatric or cardiac adverse events.22,45 Varenicline will be distributed at the 2-month (i.e., immediately prior to smoking cessation sessions) and 4-month in-person visits, and by mail as needed, based on monthly medication phone calls. Varenicline utilization, adverse events, and suicidal ideation will be assessed during these monthly medication phone calls and at the 8-month in-person data collection visit (i.e., the final week of varenicline use). Varenicline utilization will be assessed through pill counts, which has shown the greatest sensitivity and specificity of medication adherence in comparison to plasma varenicline concentration.46

Weight Management Booster Sessions.

After completing the smoking cessation intervention, SMALL and LOSS participants will receive monthly booster weight management sessions over the phone. These sessions will assist participants in the appropriate use of skills provided in weight management and smoking cessation sessions. There will be five booster sessions (weeks 16, 20, 24, 28, and 32) provided with the same group with whom they received the weight management and smoking cessation interventions, in order to preserve group social support and prevent contamination. Booster sessions will start with the interventionist eliciting diet, activity, and cessation challenges. Then, the interventionist will guide participants through the 5-step problem-solving model (i.e., identifying the problem, generating solutions, evaluating each solution, and trying the best solution) to create solutions for the self-reported challenges.47 Problem-solving was a major component to Stability Skills First and Look AHEAD ILI trials,19,48 and was more effective than relapse prevention training in long-term weight management.49

Interventionist Training and Fidelity

Our previous experience in weight management and smoking cessation research suggests that the following quality procedures will help ensure treatment fidelity: (a) detailed intervention protocol development; (b) careful interventionist training, certification, and periodic re-training; (c) randomly select 20% of intervention sessions to record and code to ensure protocol adherence and to provide corrective feedback; (d) documentation of all intervention contacts to monitor participant exposure to treatment; and (e) weekly study meetings to review overall adherence to structured protocols and prevent any drift between interventionists.

An intensive training will be conducted by trained clinical psychologists prior to starting the Fit & Quit study. This will include examining principles and techniques of behavior change, methods to facilitate interactive sessions, Motivational Interviewing principles and techniques, and tips for working with challenging participants. Moreover, the training will underscore the importance of adhering to the intervention protocol to assure treatment fidelity. Periodic trainings will also be conducted as needed. Investigators and behavioral interventionists will attend weekly team supervision meetings that will include discussions on participant progress, attendance, problem-solving, and challenging cases and skill refinement.

Measures

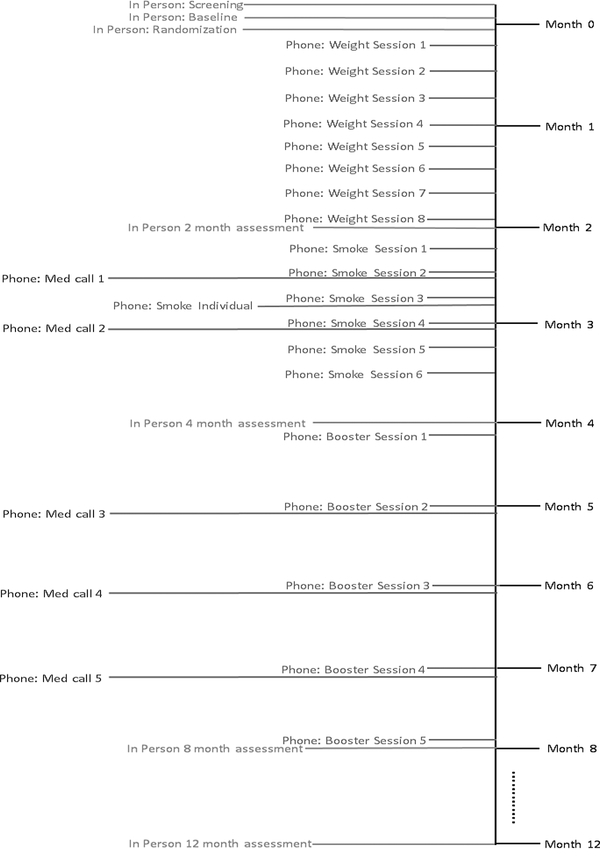

In-person data collection visits will be scheduled at baseline, and at 2-month (i.e., after the weight management component for the SMALL and LOSS conditions), 4-month (i.e., after the behavioral smoking cessation intervention), 8-month (i.e., after completion of the behavioral smoking cessation intervention and varenicline pharmacotherapy), and 12-month follow-ups. Follow-up measures will be obtained by trained staff who will be blinded to treatment assignment (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Study timeline with pre-intervention, intervention, booster, and assessment time points. BIBLIO condition will not include phone weight intervention sessions or phone booster sessions.

Primary Outcomes.

Weight will be measured in duplicate on a calibrated digital scale and recorded in kg. Participants will wear light clothing without their shoes. If the two measurements differ by no more than 0.2 kg, the average will be recorded and used for analysis. If this criterion is not met, a third measurement will be taken and the average of the three measures will be used for analysis. While the primary outcome will be weight change from baseline to 12-month follow-up, participant weight will also be measured at 2-, 4-, and 8-month follow-ups to allow us to model the weight trajectory.

We will assess smoking status (point prevalence and prolonged abstinence) at 2-, 4-, 8-, and 12-month in-person follow-ups.50 Given recent research indicating that some smokers may falsify their tobacco status,51,52 we will test cotinine levels for participants who report point prevalence abstinence at 8- and 12-month follow-up. Cotinine, a direct metabolite of nicotine, will be measured using the NicAlert™ salivary cotinine testing system. NicAlert™ is a valid and reliable method for verifying smoking status, with a specificity of 95%, sensitivity of 93%, positive predictive value of 95%, and negative predictive value of 93% (95% CI: 86 to 100%).53 A concentration of ≥ 3 ng/mL cotinine has been set as the cut point for those who are smoking.54 However, we will consider participants with ≥ 10 ng/mL cotinine in their saliva to be smokers; this liberal definition will avoid false positives due to secondhand smoke.54 If participants should indicate that they are using nicotine replacement products (not provided as a part of the study, but allowed to be used), we will verify point prevalence abstinence with end-expiratory exhaled carbon monoxide measurement of < 10 parts per million using a Micro IV Smokerlyzer (Bedfont Scientific), consistent with previous research.55

Socio-demographic Characteristics and Contact Information.

Participants will complete a questionnaire regarding their gender, age, race and ethnicity, and education level as well as provide contact information to facilitate high retention rates. Contact information will be updated at each data collection visit.

Tobacco Use and Dependence.

We will measure the number of cigarettes smoked per day, regular use of other tobacco products (e.g., e-cigarettes and smokeless tobacco), use of other cessation aids, and quit attempts. We will assess nicotine dependence with the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence.56

Physical Measures.

Arm circumference will be measured with a measuring tape to determine appropriate blood pressure cuff. After identifying the appropriate cuff, blood pressure and heart rate will be measured in duplicate using an Omron Digital Blood Measure Machine after 5 minutes of rest (e.g., sitting quietly). Duplicate measurements with systolic blood pressure differing by no more than 10 mmHg, diastolic blood pressure differing by no more than 6 mmHg, and heart rate differing by no more than 5 bpm will be obtained. If these criteria are not met, a third measurement will be taken and the average of the three measures will be used for analysis. Exclusion criteria for blood pressure and heart rate (described in “Participants” section) will be applied only at baseline. Weight will be measured as previously described in “Primary Outcomes.” Height, using a wall-mounted stadiometer with horizontal measuring block, will be measured in duplicate and recorded in centimeters. The two measurements may differ by no more than 0.5 cm and the average will be recorded. If weight and height duplicate measurements do not fall within the acceptable ranges, a third measure will be taken, and the average of the three measures will be recorded. BMI will be calculated from the average weight and height values and will be recorded in kg/m2. Waist circumference will be measured in duplicate with a non-distensible tape measure. The two measurements may differ by no more than 0.5 cm and the average will be recorded. If this criterion is not met, a third measure will be taken and the average of the three measures will be recorded. Pregnancy will be tested in women of child-bearing age at baseline using QuickVue pregnancy test. Exclusion criteria (described in “Participants” section) will be applied at baseline.

Interview.

We will assess depressive symptoms using the 20-item CESD-R scale, which is a validated and frequently used self-report measure of depressive symptoms.25 Scores ≥ 16 are considered to suggest clinically significant depression. If a participant reports depression, suicidal ideation, or an adverse event, we will involve the study physician and other investigators who are clinical psychologists. At measurement visits and monthly medication calls, we will assess adverse events and suicidality using the C-SSRS.26 We will have a safety plan to manage depression and suicidal ideation, including follow-up, to ensure that care has been obtained.

Weight Concern.

The 11-item Weight Concern Scale will be used to assess weight concern.57 Participants will be asked if they would return to smoking after a weight gain of fewer than 2 lbs., and each subsequent question will add 2 lbs. until the participant is asked, “If after quitting smoking you gained 20 pounds or more, would you start smoking?” Participants who indicate that they would return to smoking after any weight gain will be classified as “weight concerned.”

Secondary Outcomes.

Program satisfaction will be assessed at 2-, 4-, 8-, and 12-month follow-ups to offer insight into program acceptability for each condition and get feedback on specific intervention components. We will utilize a treatment satisfaction measure used in other studies,58 which will inform program refinement and future implementation.

Intervention and varenicline adherence will be assessed to assure treatment fidelity and inform potential dissemination of the intervention. Interventionists will carefully monitor session attendance, dietary and physical activity self-monitoring (if applicable), weight self-monitoring, meal replacement utilization (if applicable), and varenicline utilization to examine the implementation and to capture intervention exposure. Treatment adherence is a consistent predictor of weight management success; thus, we expect that intervention and varenicline adherence in this study will also be important in the management of post-cessation weight gain.34,59,60

Statistical Analysis

All of the analyses will be performed with SAS/STATv14.1. Data will be examined for distributional normality and outliers prior to any analyses. Descriptive statistics will be generated for all variables of interest included in the analysis, overall and by treatment arm. Univariate comparisons will consist of χ2 tests and ANOVA. We will use similar analytical methods to compare baseline characteristics between study completers and non-completers at 12 months. Based on these findings appropriate adjustments will be implemented in the regression models.

Consistent with previous studies, outcomes will be analyzed on an intention-to-treat basis, including available data from all randomized cases, regardless of treatment adherence and smoking status.12 Missing outcome data will be imputed using Markov Chain Monte Carlo model based approach by treatment arm.61 Monotone missing data pattern will be created by using all available measured outcome data points. This approach is most suitable for an arbitrary missing data mechanism.62

Our hypotheses include that randomization to the SMALL and LOSS conditions will produce smaller post-cessation weight gain compared to participants in the BIBLIO condition. The main independent variable of interest will be treatment assignment and the outcome will be weight change from baseline to 12-month follow-up. Measures of weight will be obtained at multiple time points to provide feedback, but we will model only the final measure to capture full post-cessation weight gain. Two separate general linear and mixed ANCOVA-like regression models for continuous measures will be utilized, with treatment effect estimated as the distance between the fitted group-specific means at the 12-month data collection visit (SMALL compared to BIBLIO and LOSS compared to BIBLIO), while adjusting for the fitted distance between them at baseline. In addition, we will adjust within the model for demographic factors, baseline weight, and other covariates if needed; however, due to randomization, we do not anticipate significant differences in baseline distributions. We will also test the interactions between treatment assignment and demographic covariates to examine the homogeneity of treatment effects. We will include smoking status within our modeling strategy either as moderator or a confounder. We hypothesize no significant difference in post-cessation weight gain between the SMALL and LOSS conditions. We will compare the two conditions within the scope of the regression models described previously. The main treatment comparison results will be considered significant at α = .017 due to three pre-planned contrasts, with all other associations at α = .05.

We hypothesize that participants randomized to the SMALL, LOSS, and BIBLIO conditions will have similar rates of smoking cessation at 12-month assessment. Given that the outcome is binary (i.e., prolonged abstinence; yes or no) and the treatment conditions are nominal, we will use categorical analytical methods. To test the differences in prolonged abstinence between the intervention arms, we will apply χ2 test and then a multivariate logistic regression model, with BIBLIO selected as the referent group compared to the other conditions. We will estimate the relative odds of a treatment effect on prolonged abstinence while adjusting for baseline demographics, smoking history (e.g., onset of regular smoking, quit attempts, use of tobacco products), process measures and other potential confounders. As such, we can test the associations and estimate effects of additional variables, besides treatment effect.

Discussion

Post-cessation weight gain remains a concern for those who quit smoking and is a key barrier to start the process of quitting and remaining abstinent.8–10 Notably, weight loss and weight gain prevention are challenging to achieve.11,15 However, Small Changes and Look AHEAD ILI have demonstrated promise in helping people achieve successful weight gain prevention and weight loss, respectively, but their effects have not been tested for post-cessation gain.16,18 Thus, developing efficacious interventions that minimize post-cessation weight are warranted. As such, this study aimed to adapt these two interventions to prevent weight gain in smokers after receiving an efficacious smoking cessation program with behavioral and pharmacological components. This paper described the design, interventions (i.e., weight stability, weight loss, bibliotherapy, and smoking cessation), assessments, and analyses for Fit & Quit, a randomized, controlled efficacy trial that will examine the ability of adapted weight management interventions to reduce post-cessation weight gain.

The integration of the strongest evidence-based interventions is one of the major strengths of Fit & Quit. Small Changes was designed to prevent weight gain by making small dietary (e.g., reducing 100 calories per day) and physical activity changes (e.g., adding 2000 steps per day). This intervention is an innovative approach for post-cessation weight management, where the goal is not weight loss, but weight stability.16 This randomized controlled trial demonstrated that Small Changes produced weight gain prevention compared to a psychoeducation control group 24 months post-intervention. Notably, Small Changes demonstrated similar long-term weight gain prevention compared to an intervention that promoted larger behavioral changes (e.g., 1200 to 1800 calories per day goal, 250 minutes of exercise). Second, Look AHEAD ILI was a large, multicenter, randomized controlled trial with specific goals (e.g., 1200 to 1800 calories per day, less than 30% of calories from fat, 175 minutes of moderate physical activity per week) and strategies (e.g., portion control, provision of meal replacements and plans, group setting) to facilitate weight loss.19 This intervention has demonstrated higher retention rates, higher weight loss rates, and increased fitness consistently throughout 10 years compared to psychoeducation, making it the most efficacious weight loss intervention to date.18 Furthermore, Look AHEAD ILI has demonstrated being translatable to other populations and settings.58 Third, the elements of the smoking cessation program in Fit & Quit are also strongly supported by evidence. Overall, combined behavioral and pharmacological smoking reduction interventions significantly promote long-term cessation.42 Specifically, the behavioral aspect of the smoking cessation program is based on established tobacco treatment guidelines, rate reduction strategies, and Motivational Interviewing elements that have yielded higher rates of smoking cessation compared to treatment as usual.41,63,64 Similarly, varenicline is an effective pharmacological treatment for smoking cessation.22–24

Fit & Quit is also innovative. First, while previous studies have largely focused on women,11 men are more likely to relapse after weight gain.65 Furthermore, most research on post-cessation weight gain interventions have failed to even report race and ethnicity, let alone focus on recruiting diverse samples.14 Thus, we plan to recruit broadly—and specifically for men—in a diverse community using traditional (e.g., flyers, posters, media advertisement) and electronic (e.g., Facebook) means to facilitate recruitment of a diverse sample that will aid in the generalizability of our findings. Importantly, we plan to incorporate the use and distribution of commercially-available meals that could be a cost-effective intervention strategy for a wide range of people (e.g., low socioeconomic status and people without time to prepare meals).

Second, the intervention design of this study is novel, but informed by previous research. For instance, Spring et al., examined the impact of a weight management intervention that was initiated at the same time as a 16-week smoking cessation intervention (i.e., concurrent) or a weight management intervention initiated 8 weeks into the smoking cessation intervention (i.e., sequential).12 They found that participants in the sequential approach, but not in the concurrent approach, reduced weight gain relative to a control intervention without weight management. Also, we chose to provide the weight management interventions before the smoking cessation intervention to prevent weight gain after quitting and provide success in weight stability or loss before cessation occurs.

Third, we chose to use technology such as phone calls to deliver interventions and self-monitoring devices (i.e., BodyTrace™ and Fitbit), applications, websites (i.e., MyFitnessPal and bodytrace.com), and email to enhance interventions. An important reason for choosing phone instead of in-person sessions is the need for accessible and convenient interventions that can reach people of diverse backgrounds and socioeconomic status. Appel et al., conducted a randomized clinical trial comparing the effects of remote (i.e., phone, website, and email), in-person, and self-directed (i.e., control) weight loss programs.66 Researchers found that the remote intervention was more effective at weight loss maintenance over a 2-year period compared to the control group. Notably, the remote intervention was not significantly different from the in-person intervention. In addition, multiple studies have demonstrated that smoking cessation phone treatments are efficacious and cost-effective.52,67,68 Also, technology-assisted interventions (e.g., self-monitoring applications and websites) have demonstrated better weight loss and maintenance rates compared to in-person or no intervention conditions.69 For these reasons, we expect that Fit & Quit will make a significant public health contribution to curtailing post-cessation weight gain in recent smoking quitters.

Acknowledgments

The authors of this work would like to thank the staff who contributed to different aspects of this study: Julia Graber, Marissa McRae, and Kristin Cornwell.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases [grant number 1R01DK107747–01A1]. The National Institutes of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases were not involved in the study design, collection and analysis of data, interpretation of results, or writing of this report.

Footnotes

Competing Interests

All authors confirm that there are no known conflicts of interest associated with this publication and there has been no significant financial support for this work that could have influenced its outcome.

References

- 1.Siahpush M, Singh GK, Tibbits M, Pinard CA, Shaikh RA, Yaroch A. It is better to be a fat ex-smoker than a thin smoker: findings from the 1997–2004 National Health Interview Survey-National Death Index linkage study. Tob Control. 2014;23(5):395–402. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clair C, Rigotti NA, Porneala B, et al. Association of smoking cessation and weight change with cardiovascular disease among adults with and without diabetes. JAMA. 2013;309(10):1014–1021. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.1644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parsons A, Daley A, Begh R, Aveyard P. Influence of smoking cessation after diagnosis of early stage lung cancer on prognosis: systematic review of observational studies with meta-analysis. BMJ. 2010;340:b5569. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b5569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Godtfredsen NS, Lam TH, Hansel TT, et al. COPD-related morbidity and mortality after smoking cessation: status of the evidence. Eur Respir J. 2008;32(4):844–853. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00160007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Janzon E, Hedblad B, Berglund G, Engström G. Changes in blood pressure and body weight following smoking cessation in women. J Intern Med. 2004;255(2):266–272. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2003.01293.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nilsson P, Lundgren H, Söderström M, Fagerström K-O, Nilsson‐Ehle P. Effects of smoking cessation on insulin and cardiovascular risk factors – a controlled study of 4 months’ duration. J Intern Med. 1996;240(4):189–194. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.1996.16844000.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aubin H-J, Farley A, Lycett D, Lahmek P, Aveyard P. Weight gain in smokers after quitting cigarettes: meta-analysis. BMJ. 2012;345:e4439. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e4439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klesges RC, Meyers AW, Klesges LM, La Vasque ME. Smoking, body weight, and their effects on smoking behavior: a comprehensive review of the literature. Psychol Bull. 1989;106(2):204–230. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.106.2.204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klesges RC, Shumaker SA. Understanding the relations between smoking and body weight and their importance to smoking cessation and relapse. Health Psychol. 1992;11(Suppl):1–3. doi: 10.1037/h0090339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klesges RC, Brown K, Pascale RW, Murphy M, Williams E, Cigrang JA. Factors associated with participation, attrition, and outcome in a smoking cessation program at the workplace. Health Psychol. 1988;7(6):575–589. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.7.6.575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spring B, Howe D, Berendsen M, et al. Behavioral intervention to promote smoking cessation and prevent weight gain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction. 2009;104(9):1472–1486. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02610.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spring B, Pagoto S, Pingitore R, Doran N, Schneider K, Hedeker D. Randomized controlled trial for behavioral smoking and weight control treatment: effect of concurrent versus sequential intervention. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72(5):785–796. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.5.785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ussher M, West R, McEwen A, Taylor A, Steptoe A. Randomized controlled trial of physical activity counseling as an aid to smoking cessation: 12 month follow-up. Addict Behav. 2007;32(12):3060–3064. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farley AC, Hajek P, Lycett D, Aveyard P. Interventions for preventing weight gain after smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;1:CD006219. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006219.pub3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wing RR. Behavioral interventions for obesity: recognizing our progress and future challenges. Obes Res. 2003;11(S10):3S–6S. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wing RR, Tate DF, Espeland MA, et al. Innovative self-regulation strategies to reduce weight gain in young adults: The Study of Novel Approaches to Weight Gain Prevention (SNAP) randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(6):755. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.1236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wing RR, Tate D, Espeland M, et al. Weight gain prevention in young adults: design of the Study of Novel Approaches to Weight Gain Prevention (SNAP) randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:300. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.The Look AHEAD Research Group. Cardiovascular effects of intensive lifestyle intervention in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(2):145–154. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1212914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.The Look AHEAD Research Group, Wadden TA, West DS, et al. The Look AHEAD study: a description of the lifestyle intervention and the evidence supporting it. Obesity. 2006;14(5):737–752. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harvey-Berino J The EatingWell Diet: Introducing the University-Tested VTrim Weight-Loss Program. 1 edition Woodstock, VT: Countryman Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ebbert JO, Wyatt KD, Hays JT, Klee EW, Hurt RD. Varenicline for smoking cessation: efficacy, safety, and treatment recommendations. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2010;4:355–362. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S10620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cahill K, Stevens S, Perera R, Lancaster T. Pharmacological interventions for smoking cessation: an overview and network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(5):CD009329. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009329.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tonstad S, Tønnesen P, Hajek P, et al. Effect of maintenance therapy with Varenicline on smoking cessation: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;296(1):64–71. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.1.64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baker TB, Piper ME, Stein JH, et al. Effects of nicotine patch vs varenicline vs combination nicotine replacement therapy on smoking cessation at 26 weeks: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315(4):371–379. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.19284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eaton WW, Smith C, Ybarra M, Muntaner C, Tien A. Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale: Review and Revision (CESD and CESD-R) In: The Use of Psychological Testing for Treatment Planning and Outcomes Assessment: Instruments for Adults. Vol 3 3rd ed. Mahwah, NJ, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 2004:363–377. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Posner K, Oquendo MA, Gould M, Stanley B, Davies M. Columbia Classification Algorithm of Suicide Assessment (C-CASA): Classification of suicidal events in the FDA’s pediatric suicidal risk analysis of antidepressants. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(7):1035–1043. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.164.7.1035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cohen J Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd edition Hillsdale, NJ: Routledge; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ebbert JO, Hatsukami DK, Croghan IT, et al. Combination varenicline and bupropion SR for tobacco dependence treatment in cigarette smokers: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2014;311(2):155–163. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.283185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hintze J PASS. Kaysville, UT: NCSS, LLC; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Steinberg DM, Tate DF, Bennett GG, Ennett S, Samuel-Hodge C, Ward DS. The efficacy of a daily self-weighing weight loss intervention using smart scales and email. Obesity. 2013;21(9):1789–1797. doi: 10.1002/oby.20396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Unick JL, Hogan PE, Neiberg RH, et al. Evaluation of early weight loss thresholds for identifying nonresponders to an intensive lifestyle intervention. Obesity. 2014;22(7):1608–1616. doi: 10.1002/oby.20777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carter MC, Burley VJ, Nykjaer C, Cade JE. Adherence to a smartphone application for weight loss compared to website and paper diary: pilot randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15(4):e32. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kreuter MW, Strecher VJ, Glassman B. One size does not fit all: The case for tailoring print materials. Ann Behav Med. 1999;21(4):276–283. doi: 10.1007/BF02895958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krukowski RA, Harvey-Berino J, Bursac Z, Ashikaga T, West DS. Patterns of success: online self-monitoring in a web-based behavioral weight control program. Health Psychol. 2013;32(2):164–170. doi: 10.1037/a0028135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kovelis D, Zabatiero J, Furlanetto KC, Mantoani LC, Proença M, Pitta F. Short-term effects of using pedometers to increase daily physical activity in smokers: a randomized trial. Respir Care. 2012;57(7):1089–1097. doi: 10.4187/respcare.01458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mantoani LC, Furlanetto KC, Kovelis D, et al. Long-term effects of a program to increase physical activity in smokers. Chest. 2014;146(6):1627–1632. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-0459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zabatiero J, Kovelis D, Furlanetto KC, Mantoani LC, Proença M, Pitta F. Comparison of two strategies using pedometers to counteract physical inactivity in smokers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014;16(5):562–568. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Klesges RC, Haddock CK, Lando H, Talcott GW. Efficacy of forced smoking cessation and an adjunctive behavioral treatment on long-term smoking rates. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999;67(6):952–958. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.67.6.952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Klesges RC, DeBon M, Vander Weg MW, et al. Efficacy of a tailored tobacco control program on long-term use in a population of U.S. Military troops. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006;74(2):295–306. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.2.295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Klesges RC, Ebbert JO, Talcott GW, et al. Efficacy of a Tobacco Quitline in Active Duty Military and TRICARE Beneficiaries: A Randomized Trial. Mil Med. 2015;180(8):917–925. doi: 10.7205/MILMED-D-14-00513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fiore MC, Jaén CR, Baker TB, et al. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence 2008 Update - Clinical Practice Guideline Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Public Health Service; 2009. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK63952/. Accessed June 14, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Asfar T, Ebbert JO, Klesges RC, Relyea GE. Do smoking reduction interventions promote cessation in smokers not ready to quit? Addict Behav. 2011;36(7):764–768. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.02.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Haddock CK, Talcott GW, Klesges RC, Lando H. An examination of cigarette brand switching to reduce health risks. Ann Behav Med. 1999;21(2):128. doi: 10.1007/BF02908293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA updates label for stop smoking drug Chantix (varenicline) to include potential alcohol interaction, rare risk of seizures, and studies of side effects on mood, behavior, or thinking. https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm436494.htm. Published February 26, 2018. Accessed June 12, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Anthenelli RM, Benowitz NL, West R, et al. Neuropsychiatric safety and efficacy of varenicline, bupropion, and nicotine patch in smokers with and without psychiatric disorders (EAGLES): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled clinical trial. The Lancet. 2016;387(10037):2507–2520. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30272-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Buchanan TS, Berg CJ, Cox LS, et al. Adherence to varenicline among African American smokers: an exploratory analysis comparing plasma concentration, pill count, and self-report. Nicotine Tob Res. 2012;14(9):1083–1091. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Perri MG, Nezu AM, Viegener BJ. Improving the Long-Term Management of Obesity: Theory, Research, and Clinical Guidelines. 1st ed. New York, NY: Wiley; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kiernan M, Brown SD, Schoffman DE, et al. Promoting healthy weight with “Stability Skills First”: a randomized trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2013;81(2):336–346. doi: 10.1037/a0030544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Perri MG, Nezu AM, McKelvey WF, Shermer RL, Renjilian DA, Viegener BJ. Relapse prevention training and problem-solving therapy in the long-term management of obesity. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69(4):722–726. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.69.4.722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hughes JR, Keely JP, Niaura RS, Ossip-Klein DJ, Richmond RL, Swan GE. Measures of abstinence in clinical trials: issues and recommendations. Nicotine Tob Res. 2003;5(1):13–25. doi: 10.1093/ntr/5.1.13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Klesges RC, Krukowski RA, Klosky JL, et al. Efficacy of a tobacco quitline among adult survivors of childhood cancer. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17(6):710–718. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Klesges RC, Krukowski RA, Klosky JL, et al. Efficacy of a tobacco quitline among adult cancer survivors. Prev Med. 2015;73:22–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.12.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cooke F, Bullen C, Whittaker R, McRobbie H, Chen M-H, Walker N. Diagnostic accuracy of NicAlert cotinine test strips in saliva for verifying smoking status. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10(4):607–612. doi: 10.1080/14622200801978680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Benowitz NL, Bernert JT, Caraballo RS, Holiday DB, Wang J. Optimal serum cotinine levels for distinguishing cigarette smokers and nonsmokers within different racial/ethnic groups in the United States between 1999 and 2004. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;169(2):236–248. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Koegelenberg CFN, Noor F, Bateman ED, et al. Efficacy of varenicline combined with nicotine replacement therapy vs varenicline alone for smoking cessation: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;312(2):155–161. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.7195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerström K-O. The Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence: a revision of the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addict. 1991;86(9):1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Meyers AW, Klesges RC, Winders SE, Ward KD, Peterson BA, Eck LH. Are weight concerns predictive of smoking cessation? A prospective analysis. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1997;65(3):448–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Krukowski RA, Hare ME, Talcott GW, et al. Dissemination of the Look AHEAD Lifestyle Intervention in the United States Air Force: study rationale, design and methods. Contemp Clin Trials. 2015;40:232–239. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2014.12.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wing RR, Hamman RF, Bray GA, et al. Achieving weight and activity goals among diabetes prevention program lifestyle participants. Obes Res. 2004;12(9):1426–1434. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.West DS, DiLillo V, Bursac Z, Gore SA, Greene PG. Motivational interviewing improves weight loss in women with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(5):1081–1087. doi: 10.2337/dc06-1966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Geyer CJ. Introduction to Markov Chain Monte Carlo In: Brooks S, Gelman A, Jones GL, Meng X-L, eds. Handbook of Markov Chain Monte Carlo. Chapman & Hall/CRC Handbooks of Modern Statistical Methods. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2011:3–48. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schafer JL. Analysis of Incomplete Multivariate Data. 1 edition Boca Raton, FL: Chapman and Hall/CRC; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lindson-Hawley N, Thompson TP, Begh R. Motivational interviewing for smoking cessation In: The Cochrane Collaboration, ed. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2015. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006936.pub3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stead LF, Lancaster T. Interventions to reduce harm from continued tobacco use In: The Cochrane Collaboration, ed. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2007. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005231.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Borrelli B, Spring B, Niaura R, Hitsman B, Papandonatos G. Influences of gender and weight gain on short-term relapse to smoking in a cessation trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69(3):511–515. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.69.3.511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Appel LJ, Clark JM, Yeh H-C, et al. Comparative effectiveness of weight-loss interventions in clinical practice. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(21):1959–1968. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1108660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Graham AL, Chang Y, Fang Y, et al. Cost-effectiveness of internet and telephone treatment for smoking cessation: an economic evaluation of The iQUITT Study. Tob Control. 2013;22(6):432–432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shireman T, Emchi K, Spaulding R, et al. Comparative and cost effectiveness of telemedicine versus telephone counseling for smoking cessation. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17(5):e113. doi: 10.2196/jmir.3975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Allen JK, Stephens J, Patel A. Technology-assisted weight management interventions: systematic review of clinical trials. Telemed J E Health. 2014;20(12):1103–1120. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2014.0030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]