Abstract

Introduction:

The aim of this study was to investigate the planned place of delivery for women antenatally diagnosed with abnormally invasive placenta (AIP) in England and identify how many units regard themselves to be ‘specialist centres’ for the management of AIP.

Material and methods:

Observational study of obstetric-led units in England. An anonymous survey sent to the delivery suite lead clinician in all 154 consultant-led units throughout England. The main outcome measures were whether each unit planned to manage AIP ‘in-house’, estimated number of AIP cases delivered in the previous five years and whether they considered themselves a ‘specialist centre’ for AIP management.

Results:

114 of 154 units responded (74%), 80 (70%) manage AIP cases ‘in-house’ with 23 (29%) of these reporting that they regard themselves ‘specialist centres’ for AIP. The 23 ‘specialist centres’ managed significantly more cases than ‘non-specialist centres’ (4 [95% CI 4.3–7.3] vs 1.5 [95% CI 1.5–3.1] cases/unit/year; p< 0.001), nearly one third of ‘non-specialist centres’ manage ≤one case per year. Extrapolating the reported number of cases to all 154 obstetrician-led delivery units produces an estimate of 5.2 cases per 10,000 births over the last five years.

Conclusions:

Most units plan to manage AIP ‘in-house’ despite encountering few cases each year. Centralising care would allow the multi-disciplinary team in each ‘specialist centre’ to develop significant experience in management of this rare condition leading to improved outcomes for the women.

Keywords: Abnormally-invasive placenta, AIP, placenta accreta, obstetrics

INTRODUCTION

Abnormally invasive placenta (AIP; also known as placenta accreta spectrum or accreta, increta and percreta) is a potentially life-threatening pregnancy complication with an increasing incidence worldwide, most likely due to the rising rate of Caesarean delivery (1). Given the complexity of the pelvic surgery often required at delivery it is unsurprising that maternal morbidity from AIP is reported to be high. Over a 12 month period (2010–2011) the United Kingdom Obstetric Surveillance system (UKOSS) reported 134 cases of AIP in the UK (2) of which 13% suffered severe maternal morbidity including ten bowel or lower urinary tract injuries, three vesico-vaginal fistulae, one utero-cutaneous fistula, and two cardiac arrests (2).

There is evidence that antenatal diagnosis reduces the maternal morbidity, with AIP cases identified before delivery requiring fewer emergency hysterectomies and massive transfusions(3). There is also a mounting body of evidence that women managed by a multidisciplinary team who have developed specific experience in managing the risks and challenges presented by AIP have better outcomes(4–6). Multiple cohort studies have suggested that mothers treated according to a standardised approach implemented by a ‘specialist’ multi-disciplinary team fared better according to a several metrics including intraoperative blood loss(4), intensive care admissions(5) and re-operation(6). These findings are consistent across many studies demonstrating reduced morbidity when women are treated by ‘specialist’ surgical teams with increased experience(7, 8). Taken together, this suggests that optimum patient care would be achieved by concentrating all elective AIP deliveries in a few ‘specialist centres’, ensuring women are managed by a well-equipped multi-disciplinary team with significant experience in this relatively rare condition. This model of care would be similar to that seen with the National Health Service regional networks for major trauma and oncology, with hospitals specialising in, and being designated for, the diagnosis and treatment of AIP. However, how AIP is currently being managed in England is unknown.

The objective of this study was to investigate how many units in England plan to manage women with an antenatal diagnosis of AIP ‘in house’, how many refer to other units and how many regard themselves ‘specialist centres’ for the management of this rare condition.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

All consultant-led obstetric units in England were identified using information provided by the Royal College of Midwives. Each unit was then contacted by telephone and asked to provide an email address for the clinical lead for their delivery suite. Each clinical lead was then sent an anonymous survey (Supporting Information Figure S1) by email which they were invited to reply to regarding the provision of services for AIP within their unit over the previous five years (2012 to 2017). Details of the survey is provided as supplementary material (S1).

The covering email briefly explained the purpose of the survey and asked the recipient to pass it on to an appropriate clinician if they felt unable to complete it. Three reminders were sent to non-respondents in order to increase the response rate. Given that the diagnosis of AIP can only be made at or after delivery, it is more correct to refer to cases as being ‘suspicious’ of abnormal placentation. We have used the term ‘diagnosed’ to mean that AIP was sufficiently suspected antenatally to prompt specific intra-partum management for AIP such as use of interventional radiology, a vertical skin incision and cell salvage.

Statistical analyses

The range of values for five-year caseload for the ‘specialist’ and ‘non-specialist centres’ were tested for normal distribution using the Shapiro-Wilk test and variance assessed with Levene’s test. The Mann-Whitney test employing the Monte Carlo method with a power of 10000 was used to examine for a significant difference (SPSS; IBM Analytics, Armonk, USA). When the five-year caseload estimate was provided as a range of values the mean value was used.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not required for this study as no patient-identifiable data was used.

RESULTS

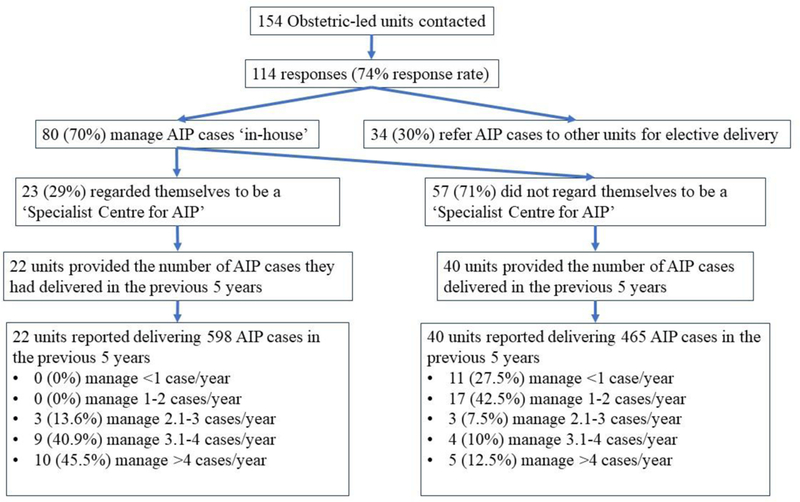

Of the 154 consultant-led obstetric units identified and contacted, 114 completed the survey, a response rate of 74%. Eighty units (70%) planned to electively manage their AIP cases ‘in house’, with 34 (30%) referring to other units. Figure 1 shows a flow diagram for the responses regarding planned place of delivery and antenatally diagnosed cases managed over the previous five years. The 62 units who provided case numbers reported delivering a total of 1063 cases of AIP over the last five years. Of the 80 units planning to manage their cases ‘in house’, only 23 (29%) responded that they considered their unit to be a ‘specialist centre’ for the management of AIP. Twenty two of the 23 self-declared ‘specialist centres’ and 40 of the 57 ‘non-specialist’ centres provided an estimate of case numbers for the last five years. Of the 40 ‘non-specialist’ units who provided caseload estimates, 28 (70%) reported that they treat two cases or fewer per year and 11 (27.5%) reported that they deliver fewer than one each year with only five (12.5%) managing 4 or more. The 22 ‘specialist centres’ who provided data on their caseload and reported managing a total of 598 cases over the last five years, with a median of 4 cases/centre/year whereas the 40 ‘non specialist’ centres providing figures reported managing 465 cases over five years, a median of 1.5 cases/centre/year (see figure 1). The difference in median number of cases manged by each type of unit was found to be significant (p<0.001) using the Mann-Whitney test as the Shapiro-Wilk demonstrated the groups were not normally distributed. All the ‘specialist centres’ reported receiving referrals from other units (mean four other units: range 1–10) whilst six ‘non-specialist’ centres reported receiving referrals from other centres (mean 3.5 other units: 1–8). Just one of the 23 (4%) ‘specialist centres’ reported that they believed they were appropriately reimbursed for their service.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram showing the exact breakdown of responses. Of the 80 units that manage cases ‘in-house’, 23 (29%) regard themselves ‘specialist centres’ for the abnormally-invasive placenta (AIP) delivery, 57 (71%) units planned to manage AIP cases themselves but did not regard themselves a ‘specialist centre’. The 40 ‘non-specialists’ that managed cases themselves and provided full data managed significantly fewer cases than the units that regarded themselves as ‘specialists’ (4 vs 1.5 cases/unit/year, p<0.001).

DISCUSSION

The majority (70%) of units in England who responded to the survey plan to deliver their AIP cases ‘in house’ irrespective of how much experience they have with this rare condition. Of the 40 ‘non-specialist’ units who provided an estimate of case numbers nearly one third reported that they aim to deliver the women ‘in house’ despite undertaking such surgery on fewer than one woman per year. There are already units in England which consider themselves to be ‘specialist centres’ for the diagnosis and management of AIP. The ‘specialist centres’ deliver significantly more cases than the ‘non-specialist’ units with the majority (86%) delivering more than 3 cases per year.

There are always a number of limitations seen with a retrospective survey. A potential confounding factor would be if ‘non-specialist’ units chose to manage only less complex AIP cases, recognising that more complex cases may need more experienced care and referring accordingly. This might see cases of accreta (creta), which has a lesser burden of pathology, managed ‘in house’, with women with a greater degree of placental invasion being referred to more experienced units. This is unlikely to have been the case however, for two reasons; distinguishing antenatally the degree of AIP is challenging, with current classification relying on a histopathological diagnosis which may be misleading depending on where the placental bed is sampled. As a result, it is unlikely that units would make referral decisions based on this, especially given the potential serious consequences of an erroneous diagnosis. Also, none of the units reporting that they planned to deliver them ‘in house’ also reported that they referred cases elsewhere.

Another possible confounder would be if some ‘non-specialist’ units already have a policy to refer AIP cases to other units, and the cases they reported managing are women where the diagnosis of AIP was actually missed antenatally. This might be compounded by the current lack of agreed-on methods for AIP screening, meaning more women are likely to be recognised as having AIP only at delivery. To avoid this, we asked respondents to provide details of their antenatally diagnosed cases, recognising that emergencies are time-critical transfer to another unit may not be possible.

The empirical relationship between surgical volume and mortality has long been known. Nearly forty years ago it was demonstrated that the mortality of complex surgical procedures including open-heart surgery, vascular surgery, and coronary bypass decreased with increasing numbers of operations(9). Hospitals where 200 or more of these procedures were undertaken annually had death rates 25% to 41% lower than hospitals with lower volumes. The association between experience and complication rates has also been clearly demonstrated in many surgical situations including scoliosis surgery(10), minimally invasive prostatectomy(11) and anterior cervical discectomy(12). Therefore, given the complexity of the surgery and the multitude of potential options for the management of AIP, greater experience gained by managing a higher volume of cases in a small number of ‘specialist centres’ is highly likely to result in optimal patient care. This is confirmed by the increasing number of publications showing reduction in maternal morbidity with the introduction of experienced multi-disciplinary teams and a standardised approach to the care of AIP (4–6). The large number of units managing a small number of cases despite not considering themselves as ‘specialists’ suggests that the benefit of referral to more experienced centres may not be understood. Adoption of a more centralised model would need to be accompanied by a campaign to highlight to obstetricians the improvement this would make to patient care to reinforce the importance of engagement with this scheme. To optimise appropriate referral, we recommend the development of a nationally agreed pathway to identify women with features highly suspicious of AIP who would benefit from transfer to a higher-volume unit.

Whilst there is strong and increasing evidence for a reduction in maternal morbidity if management is undertaken by an experienced multi-disciplinary team, no definition, consensus or regulations exists to determine what constitutes a ‘specialist centre’ for AIP.Until this is developed therefore, it is currently down to the unit itself to define whether they regard themselves as such. Our study demonstrated that those centres who did regard themselves to be ‘specialists’ received referrals from, on average, four other units and delivered significantly more cases per year. If the care of women in England with AIP is to be truly optimised the requirement of what constitutes such a ‘specialist unit’ must be formalised, outcome measures decided on and audited, and their performance benchmarked against other centres. It should be noted though that only one of the 23 ‘specialist centres’ considered that they were appropriately remunerated for their service. If provision of this service is to be concentrated to a limited number of hospitals to improve the care of the women, an appropriate tariff must be paid to the unit for each case or the financial burden will prove overwhelming and the model of care will be unsustainable.

Extrapolating the respondent’s data to all obstetric-led delivery units in the UK, 108 of the 154 units (70%) will manage AIP cases ‘in-house’. Assuming that the fraction of ‘specialist centres’ is the same as for the respondents, 31 units (29%) will be ‘specialist centres’ managing 4 cases/centre/year and 77 units ‘non-specialist’ 1.5 cases/centre/year. This equates to 344 cases per year in England, calculated using the mean of the reported 5-year caseloads. Using the reported number of deliveries in England during 2016 (663,157 ) (13) produces an estimated incidence of 5.2 cases per 10,000 births.

The incidence of 1.7 cases of accreta/increta/percreta per 10,000 maternities previously reported by the UKOSS survey is somewhat lower than the number being anecdotally reported by English clinicians based on their current experience. This may reflect recollection bias, the individual definition of AIP or a dramatic increase in the actual incidence of AIP. A recent BJOG article by Thurn et al(14) reported an incidence of 3.4 per 10,000 deliveries in Nordic countries, which have historically had a lower caesarean delivery rate than the UK. This potentially supports the clinician experience of an increasing incidence. To try to examine the current incidence in a similar way to the Nordic study attempts were made to interrogate the central National Health Service coding system. Unfortunately, major differences were identified in the way in which these cases have been ‘coded’ by different Trusts leading to unacceptable inaccuracies in the data. Therefore, this study was undertaken in an attempt to gain a more recent estimate of incidence and an indication of where these deliveries are occurring. How the clinicians reporting figures reached their case number is, of course, important. It is hoped that they checked the records for their units however this cannot be guaranteed, leaving their quoted figure open to recollection bias. However, given the rarity of the condition and the disruption to delivery suite such a case causes it is highly likely that their figures will be in the correct “ball-park”. With nearly three quarters of the units in England replying, this study provides a simple snap shot of the cases each unit in England believes it has encountered over the previous five years (2012 to 2017). This is not as potentially accurate as a prospective study, although even such high profile and robustly performed studies as those run by UKOSS still have issues with studies reliant on clinician reporting. The incidence of 5.2 per 10,000 deliveries is considerably higher than the previous estimate. This could in part be due to the fact that each unit was allowed to define AIP according to its own local criteria. Whilst there are agreed diagnostic criteria for histopathological diagnosis of AIP no such consensus exists for clinical diagnosis if hysterectomy is not undertaken. Such differences in case definition may be responsible for the wide range in the incidence reported in the literature (2–90 per 10,000 births), with many studies considering difficulty removing the placenta to be indicative of accreta whilst others only include cases requiring laparotomy. This problem will continue until a worldwide consensus is reached on the clinical diagnosis of this spectrum condition.

This is the first study that has attempted to ascertain how many units in England plan to deliver their AIP cases ‘in house’ irrespective of their experience with the pathology and how many consider themselves to be ‘specialist centres’. A survey-based methodology is ideally suited to answer such a simple question regarding a unit’s protocol. However, a limitation of any survey-based research is always the poor response rate(15). Although it was not 100%, a response rate of 74% is widely accepted as excellent and sufficient for conducting meaningful analysis. As with any survey study our data relies on the accuracy of the responses received. We did not perform a pilot study with a draft of our questionnaire, raising the possibility that the phrasing of questions may have led to some confusion and inclusion of misleading information. However, the questionnaire was designed to be extremely simple and the additional comments we received from respondents does not suggest that widespread misinterpretation was an issue.

Our study surveyed only delivery units in England, limiting the scope to only one country and one healthcare model. However, there is good reason to believe our results represent a snapshot of a global problem. Much of the data showing the benefit of consolidating AIP cases to centres with more experience derives from the United States (4–7), suggesting that this approach is valid for UK analogous to the Trauma network could act as the model for similar systems across the world.

CONCLUSION

Of the 91 units that reported that they are not ‘specialist centres’, 57 (63%) plan to manage their AIP cases ‘in-house’, despite the mounting evidence that patient morbidity is decreased if they are referred to ‘specialist centres’ with a higher annual caseload. Further work is required to raise awareness of the potential benefits to the patients of referral to ‘specialist centres’, especially amongst those units who currently only handle a small number of cases. Formalising the AIP referral process into a regional network would clarify and streamline this process, which would include creation of a diagnostic algorithm to identify women who would benefit from transfer to a more experienced unit.

Supplementary Material

Key message.

There is mounting evidence that women treated by multidisciplinary teams with significant experience in abnormally-invasive placenta have better outcomes. Despite this, our data suggests that many hospitals that see fewer than one case per year still plan to deliver their abnormally-invasive placenta cases ‘in house’ rather than refer them to specialist units.

Acknowledgements

With grateful thanks to Anthony Prudhoe at NHS England who helped formulate the underlying research question and develop the current study.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Human Placenta Project of the National Institutes of Health under award number UO1-HD087209.

Abbreviations

- AIP

abnormally-invasive placenta

- UKOSS

United Kingdom Obstetric Surveillance system

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest notification

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare

References

- 1.Morlando M, Sarno L, Napolitano R, et al. Placenta accreta: incidence and risk factors in an area with a particularly high rate of cesarean section. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2013;92:457–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fitzpatrick KE, Sellers S, Spark P, Kurinczuk JJ, Brocklehurst P, Knight M. The management and outcomes of placenta accreta, increta, and percreta in the UK: a population-based descriptive study. BJOG. 2014;121:62–70; discussion −1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chantraine F, Braun T, Gonser M, Henrich W, Tutschek B. Prenatal diagnosis of abnormally invasive placenta reduces maternal peripartum hemorrhage and morbidity. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2013;92:439–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shamshirsaz AA, Fox KA, Salmanian B, et al. Maternal morbidity in patients with morbidly adherent placenta treated with and without a standardized multidisciplinary approach. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212:218.e1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Al-Khan A, Gupta V, Illsley NP, et al. Maternal and fetal outcomes in placenta accreta after institution of team-managed care. Reprod Sci. 2014;21:761–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eller AG, Bennett MA, Sharshiner M, et al. Maternal morbidity in cases of placenta accreta managed by a multidisciplinary care team compared with standard obstetric care. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(2 Pt 1):331–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vree FEM, Cohen SL, Chavan N, Einarsson JI. The impact of surgeon volume on perioperative outcomes in hysterectomy. JSLS. 2014;18(2):174–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maruthappu M, Gilbert BJ, El-Harasis MA, et al. The influence of volume and experience on individual surgical performance: a systematic review. Ann Surg. 2015;261(4):642–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luft HS, Bunker JP, Enthoven AC. Should operations be regionalized? The empirical relation between surgical volume and mortality. N Engl J Med. 1979;301(25):1364–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Skovrlj B, Cho SK, Caridi JM, Bridwell KH, Lenke LG, Kim YJ. Association between surgeon experience and complication rates in adult scoliosis surgery: a review of 5117 cases from the Scoliosis Research Society Database 2004–2007. Spine. 2015;40:1200–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Budäus L, Sun M, Abdollah F, et al. Impact of surgical experience on in-hospital complication rates in patients undergoing minimally invasive prostatectomy: a population-based study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18(3):839–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cole TS, Veeravagu A, Zhang M, Cheng I, Ratliff J. Surgeon experience and complication rates in anterior cervical discectomy and fusions: a national longitudinal database study. Spine J. 2014;14(11):S123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vital statistics: population and health reference tables. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationestimates/datasets/vitalstatisticspopulationandhealthreferencetables: Office for National Statistics; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thurn L, Lindqvist P, Jakobsson M, et al. Abnormally invasive placenta—prevalence, risk factors and antenatal suspicion: results from a large population-based pregnancy cohort study in the Nordic countries. BJOG. 2016;123(8):1348–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cho YI, Johnson TP, VanGeest JB. Enhancing surveys of health care professionals : a meta-analysis of techniques to improve response. Eval Health Prof. 2013;36(3):382–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.