Abstract

Objectives

We aimed to assess for sex differences in invasive parameters of acute microvascular reperfusion injury and infarct characteristics on cardiac MRI after ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI).

Methods

Patients with STEMI undergoing emergency percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) were prospectively enrolled. Index of microcirculatory resistance (IMR) and coronary flow reserve (CFR) were measured in the culprit artery post-PCI. Contrast-enhanced MRI was used to assess infarct characteristics, microvascular obstruction and myocardial haemorrhage, 2 days and 6 months post-STEMI. Prespecified outcomes were as follows: (i) all-cause death/first heart failure hospitalisation and (ii) cardiac death/non-fatal myocardial infarction/urgent coronary revascularisation (major adverse cardiovascular event, MACE) during 5- year median follow-up.

Results

In 324 patients with STEMI (87 women, mean age: 61 ± 12.19 years; 237 men, mean age: 59 ± 11.17 years), women had anterior STEMI less often, fewer prescriptions of beta-blockers at discharge and higher baseline N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide levels (all p < 0.05). Following emergency PCI, fewer women than men had Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) myocardial perfusion grades ≤ 1 (20% vs 32%, p = 0.027) and women had lower corrected TIMI frame counts (12.94 vs 17.65, p = 0.003). However, IMR, CFR, microvascular obstruction, myocardial haemorrhage, infarct size, myocardial salvage index, left ventricular remodelling and ejection fraction did not differ significantly between sexes. Female sex was not associated with MACE or all-cause death/first heart failure hospitalisation.

Conclusion

There were no sex differences in microvascular pathology in patients with acute STEMI. Women had less anterior infarcts than men, and beta-blocker therapy at discharge was prescribed less often in women.

Trial registration number

Keywords: sex, myocardial infarction, clinical outcomes, index of microcirculatory resistance, microvascular obstruction, MRI

Key questions.

What is already know about the subject?

Women with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) have reportedly worse outcomes than men and microvascular pathology has been postulated as a potential mechanism.

Findings from non-invasive imaging studies are conflicting, some report smaller infarcts in women while others report no sex differences.

Previous studies did not use MRI methods to detect myocardial haemorrhage (microvascular destruction) and most acquired MRI at a single time point.

What does this study add?

There were no sex differences in acute microvascular reperfusion injury with index of microcirculatory resistance, or on MRI.

Women had fewer anterior myocardial infarcts and were prescribed beta-blockers at discharge less often than men.

How might this impact on clinical practice?

The hypothesis of sex differences in acute microvascular injury for STEMI is not supported by this study.

This study serves a reminder of sex differences in post-MI care in contemporary practice, and the need to reduce sex imbalance in management.

Introduction

Ischaemic heart disease is the leading cause of death and disability worldwide.1 Although many studies have reported worse outcomes in women after ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI),2 3 the results are conflicting.4 5

Confounders, including older age6 and comorbidities,7 particularly diabetes mellitus,8 and renal insufficiency,3 6 may contribute to excess mortality in women post-STEMI. Another confounder is longer symptom to reperfusion times in women6 8–10 purportedly attributable to women underestimating their cardiovascular risk or misinterpreting the symptoms which may be atypical in nature.11 Sex disparity in guideline-directed pharmacological2 and invasive reperfusion treatments has also been reported.3 10–12 Reducing sex imbalance in management and outcomes post-STEMI, and identifying potential mechanistic explanations, is emphasised in guideline recommendations.2 13

Findings from previous studies on sex and infarct size assessed by MRI are conflicting; some report smaller infarct size and greater myocardial salvage in women4 while others reported no sex differences.6–8 14 A previous study using single-photon emission CT also observed better myocardial salvage after primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in women.5 Limitations of these studies include not using specific MRI methods to detect myocardial haemorrhage (a consequence of severe microcirculatory injury) and the acquisition of MRI at a single early time point post-STEMI in most,6–8 14 but not all, studies.4 This is relevant since the size of infarction evolves dynamically post-STEMI. Furthermore, patients included in some studies were pooled from multiple randomised trials.5 8

Microvascular dysfunction has been postulated as a potential mechanism for worse outcomes in women.8 We investigated sex associations with the incidence, nature and timecourse of reperfusion injury in patients after an acute STEMI using invasive measures of microvascular function acutely, and serial assessments with multiparametric contrast-enhanced MRI.15 We also aimed to assess the prognostic implications on left ventricular (LV) surrogate outcomes revealed by MRI at 6 months and health outcomes in the longer term.

Methods

Study population

We performed a retrospective analysis of a prospectively collected cohort of patients with acute STEMI in a regional cardiac centre from July 2011 to November 2012. Consecutive, unselected patients with STEMI were screened for inclusion in the study and patients with MRI contraindications were excluded. The study was approved by the National Research Ethics Service (reference 10-S0703-28).

Sociodemographic status was identified from postcodes at the time of enrolment into the study, using the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (SIMD) tool. The first and fifth SIMD quintiles contain the 20% most deprived and least deprived postal zones in Scotland, respectively.

Invasive physiology, angiographic and ECG measures of microvascular injury

Index of microcirculatory resistance (IMR) was measured in the culprit coronary artery using a coronary guidewire with a pressure sensor and temperature sensor (Abbott Vascular, Santa Clara, CA, USA) at the end of primary PCI or rescue PCI, as previously described.15 IMR is defined as distal coronary pressure multiplied by mean transit time of a bolus of saline at room temperature, during maximal coronary hyperaemia (induced by 140 µg/kg/min of intravenous adenosine preceded by an intracoronary bolus of 200 µg of nitrate).15 Coronary flow reserve (CFR) is the mean transit time at rest divided by the mean transit time during hyperaemia.

Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) myocardial perfusion grade and corrected TIMI frame count were evaluated at the end of the PCI procedure. If the infarct-related vessel was the left anterior descending artery (LAD), the frame count was divided by 1.7 to correct for longer vessel length. Complex plaques were defined as lesions ≥30% diameter stenosis with ≥2 adverse features on a five-point plaque characterisation score comprising the following: presence of a filling defect/thrombus; ulceration; irregularity; TIMI flow <3, moderate/severe calcification or involvement of a bifurcation.16 Intraprocedural thrombotic events were defined as new or increasing thrombus, abrupt vessel closure, no reflow or slow reflow, or distal embolisation at any time during PCI.17 ST-segment resolution was assessed 60 min after reperfusion and was compared with ECGs obtained before coronary reperfusion.

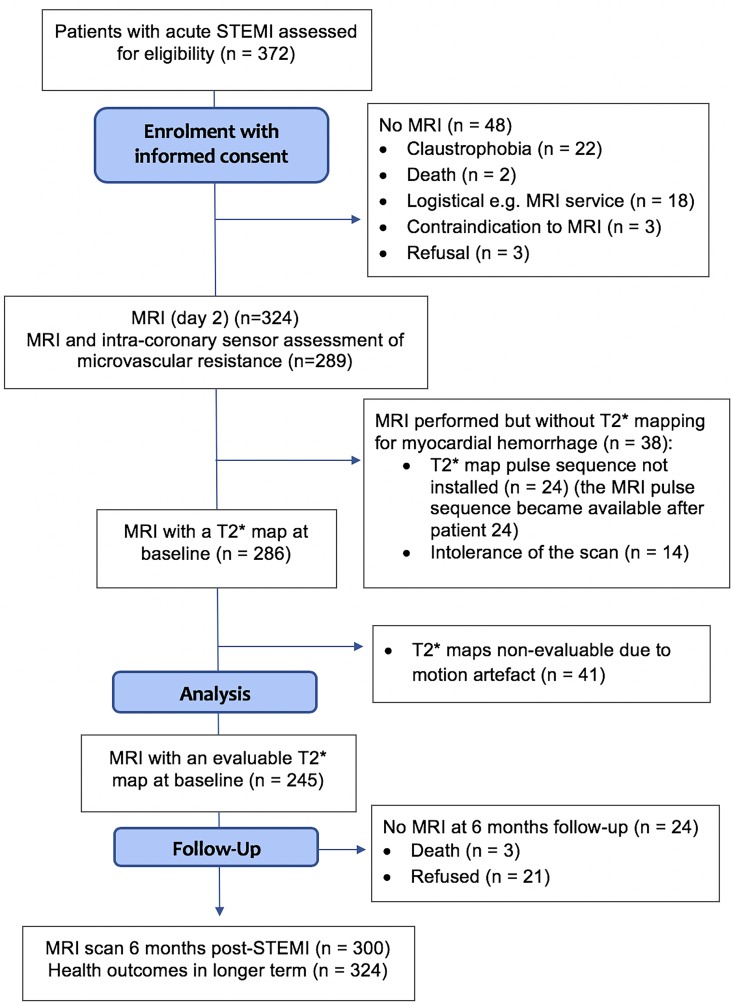

Cardiac MRI

MRI was performed on a Siemens MAGNETOM Avanto (Erlangen, Germany) 1.5-Tesla scanner at 2 days post-STEMI and 6 months later (figure 1). The imaging protocol (Supplementary Methods) included cine MRI with steady-state free precession, T2-mapping,18 native T1 mapping,19 T2*-mapping14 and delayed-enhancement phase-sensitive inversion-recovery pulse sequences.20 The scan acquisitions were spatially co-registered and included different slice orientations to enhance diagnostic confidence.

Figure 1.

Consort flow diagram of the study. STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

Image analyses

The MRI analyses are described in detail in the Supplementary Methods. The results of infarct characteristics are reported for the whole of the LV.

Infarct size, microvascular obstruction and myocardial haemorrhage

The presence of acute infarction was established based on abnormalities in cine wall motion, rest first-pass myocardial perfusion and delayed-enhancement imaging in two imaging planes. The myocardial mass of late gadolinium was quantified using computer-assisted planimetry and the territory of infarction was delineated using a signal intensity threshold of >5 standard deviations (SDs above a remote reference region and expressed as a percentage of total LV mass.14 Late gadolinium enhancement and microvascular obstruction were expressed as % LV mass.

Microvascular obstruction was defined as a dark zone on late gadolinium enhancement imaging at least 1 min post-contrast injection that persisted within an area of late gadolinium enhancement at 15 min. On the T2* maps, a region of reduced signal intensity within the infarcted area, with a T2* value of <20 ms14 was considered to confirm the presence of myocardial haemorrhage.

Myocardial salvage

Myocardial salvage was calculated by subtraction of the infarct size at 6 months from the baseline area at risk.14 The myocardial salvage index was calculated by dividing the myocardial salvage area by the initial area at risk.

LV remodelling

An increase in ≥20% LV end-diastolic volume (LVEDV) at 6 months from baseline was taken to reflect adverse LV remodelling.19

Clinical outcomes

The prespecified primary composite outcome was all-cause death or the first heart failure hospitalisation following the initial admission. The second composite outcome was major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) including cardiac death, non-fatal myocardial infarction (MI) or urgent coronary revascularisation (Supplementary Methods).

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (V.24.0, SPSS, IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) and MedCalc Statistical Software V.18 (MedCalc Software, Ostend, Belgium). Continuous variables were tested for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test, and were presented as mean±SD, or median and interquartile range (IQR) as appropriate. Continuous and categorical between-group comparisons were based on χ2 and t-tests, respectively, unless indicated otherwise (tables 1–3). Associations between baseline covariates and MRI outcomes were evaluated using linear or logistic regression for continuous or categorical outcomes, respectively. Associations between baseline covariates and clinical outcomes were evaluated using cox proportional hazards analyses. Non-sex (woman/ man) variables that were significant (p<0.05) were included in multivariable analyses to assess for associations between sex and parameters from the angiographic, ECG and MRI analyses. Associations were expressed as odds ratios (OR), or hazard ratios (HR), with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Predictors of late mortality (median 5-year follow-up) were assessed only in those patients who survived to hospital discharge (landmark survival analysis). Kaplan-Meier survival plots were constructed for visualisation and assessed using the log-rank test.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Characteristics* | Women (n=87) | Men (n=237) | P value |

| Age (years), mean±SD | 61.18±12.19 | 58.61±11.17 | 0.074* |

| Current smoker, n (%) BMI (kg/m2), median (IQR) |

57 (66) 28.50 (25.10–32.30) |

139 (59) 28.30 (25.78–31.20) |

0.262† 0.664‡ |

| BMI <25 (kg/m2), n (%) 25≤BMI<30 (kg/m2), n (%) BMI≥30 (kg/m2), n (%) |

18 (21) 29 (33) 40 (46) |

44 (19) 112 (47) 81 (34) |

0.069† |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 32 (37) | 73 (31) | 0.308† |

| Hypercholesterolaemia, n (%) | 28 (32) | 66 (28) | 0.446† |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 8 (9) | 26 (11) | 0.644† |

| Previous MI, n (%) | 5 (6) | 20 (8) | 0.421† |

| Previous PCI, n (%) | 2 (2) | 16 (7) | 0.171§ |

| Pre-infarct angina, n (%) | 9 (10) | 31 (13) | 0.507† |

| Social deprivation status, n (%): | |||

| I II III IV V |

31 (36) 16 (19) 16 (19) 11 (13) 12 (14) |

81 (35) 53 (23) 38 (16) 39 (17) 23 (10) |

0.750† |

| Presenting HR (bpm), median (IQR) | 80.00 (67.50–91.00) |

76.00 (65.00–87.00) |

0.092‡ |

| Presenting BP <90/60 (mm Hg), n (%) | 14 (16) | 21 (9) | 0.063† |

| Ventricular fibrillation/tachycardia, n (%) | 8 (9) | 14 (6) | 0.297† |

| Symptom to reperfusion time (min), median (IQR) | 172.50 (122.00–316.00) |

174.00 (119.00–314.00) |

0.746‡ |

| Symptom to reperfusion time >6 hours, n (%) | 16 (20) | 41 (18) | 0.840† |

| Door-to-balloon time (min), median (IQR) | 20.00 (16.00–23.00) |

19.00 (16.00–24.00) |

0.477‡ |

| Killip class, n (%): | |||

| I II III/IV |

65 (75) 15 (17) 7 (8) |

168(71) 53 (22) 16 (7) |

0.584† |

| Reperfusion strategy, n (%): | 0.458§ | ||

| Primary PCI | 83 (95) | 219 (92) | |

| Thrombolysis (failed/successful) | 4 (5.2) | 18 (8.8) | |

| Aspiration thrombectomy, n (%) | 57 (66) | 179 (76) | 0.073† |

| Glycoprotein IIbIIIa inhibitor, n (%) | 82 (94) | 215 (91) | 0.307† |

| Medications at discharge: | |||

| ACE-I or ARB, n (%) | 85 (98) | 235 (99) | 0.293† |

| Beta-blocker, n (%) | 79 (91) | 229 (97) | 0.032† |

| Statin, n (%) | 87 (100) | 237 (100) | |

| Aspirin, n (%) | 86 (99) | 237 (100) | 0.098† |

| Clopidogrel, n (%) Ticagrelor, n (%) |

86 (99) 1 (1) |

235 (99) 2 (1) |

0.799† |

| Blood results on admission: | |||

| Anaemia, n (%) | 17 (20) | 41 (17) | 0.641† |

| eGFR ≥60 (mL/min/1.73 m2), n (%) 30≤eGFR<60 (mL/min/1.73 m2), n (%) eGFR <30 (mL/min/1.73 m2), n (%) |

76 (87) 11 (13) 0 |

222 (94) 14 (6) 0 |

0.059† |

| C-reactive protein, mg/L, median (IQR) | 4.00 (2.00–9.00) |

3.00 (2.00–7.00) |

0.063‡ |

| Peak troponin T, ng/L, median (IQR) | 1334.00 (83.60–3548.00) |

1944.50 (165.40–5437.50) |

0.113‡ |

| N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide, median (IQR) | 1175.00 (627.50–2285.50) |

701.50 (309.00–1456.00) |

0.009‡ |

| Blood results at 6 months post-STEMI | |||

| N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide, median (IQR) | 230.50 (97.00–510.50) |

154.00 (73.00–337.00) |

0.144‡ |

Presenting HR was available in 321 subjects. Symptom-to-reperfusion time was available in 304 subjects. Door-to-balloon time was available in 305 subjects. eGFR was available in 323 subjects. C-reactive protein was available in 316 subjects. Peak troponin was available in 313 subjects. N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide results were available in 139 subjects on admission and 171 subjects at 6 months. Results of interleukin 6 were available in 139 subjects on admission and 171 subjects at 6 months. Information on anaemia was available in 324 subjects and was defined as haemoglobin<130 g/L in men or <115 g/L in women.

*Student’s t-test.

†χ2 test.

‡Mann-Whitney U test.

§Fisher’s exact test.

ACE-I, ACE inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HR, heart rate; MI, myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

Table 2.

ECG, invasive coronary physiology and angiographic characteristics

| Women (n=87) | Men (n=237) | P value | |

| Angiography: | |||

| Number of diseased coronary arteries, n (%): | |||

| 1 2 3 |

48 (55) 27 (31) 12 (14) |

126 (53) 72 (30) 39 (17) |

0.842* |

| Culprit artery, n (%): LAD or left main Right coronary artery Circumflex |

27 (31)/0 50 (58) 10 (12) |

93 (39)/1 (0) 94 (39.7) 49 (21) |

0.013* |

| TIMI flow grade pre-PCI ≤1, n (%) | 65 (75) | 162 (68) | 0.268* |

| TIMI flow grade post-PCI ≤2, n (%) | 4 (5) | 19 (8) | 0.288* |

| TIMI frame count post-PCI, median (IQR) | 12.94 (10.00–18.62) |

17.65 (10.00–27.77) |

0.003† |

| TIMI myocardial perfusion grade post-PCI, n (%): ≤1 ≥2 |

17 (20) 70 (81) |

76 (32) 161 (68) |

0.027* |

| Plaque characteristics: | |||

| Culprit lesion plaque characterisation score, n (%): ≤Median (4) >Median (4) |

76 (87) 11 (13) |

193 (81) 44 (19) |

0.208* |

| Number of complex plaques in culprit/non-culprit coronary arteries, n (%): ≤1 ≥2 |

65 (75) 22 (25) |

180 (76) 57 (24) |

0.818* |

| Intraprocedural thrombotic event occurrence, n (%) | 8 (9) | 25 (11) | 0.721* |

| Invasive coronary physiology: | |||

| IMR (U), median (IQR) | 23.10 (15.00–41.00) |

25.50 (15.33–47.68) |

0.199† |

| IMR >40(U), n (%) | 21 (27) | 60 (28) | 0.771* |

| CFR, median (IQR) | 1.50 (1.10–2.03) |

1.60 (1.10–2.10) |

0.427† |

| CFR≤2, n (%) | 13 (17) | 37 (18) | 0.871* |

| ECG: | |||

| ST-segment resolution, n (%): Complete, ≥70% Incomplete, 30% to <70% None, ≤30% |

44 (51) 31 (36) 12 (14) |

104 (44) 96 (41) 36 (15) |

0.580* |

TIMI frame count post-PCI was available in 322 subjects. IMR was available in 289 subjects. CFR was available in 286 subjects. Information on ST-segment resolution was available in 323 subjects.

*χ2Chi-square test.

†Mann-Whitney U test.

CFR, coronary flow reserve; IMR, Index of microcirculatory resistance; LAD, left anterior descending artery; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; TIMI, Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction.

Table 3.

Cardiac MRI findings at 2 days and 6 months post-reperfusion in patients with STEMI

| Female (n=87) | Male (n=237) | P value | |

| MRI finding 2 days post-MI | |||

| Infarct size (%LV mass), median (IQR) LVEF%, mean±SD |

15.90 [4.90–24.28) 56.5±9.8 |

16.50 [7.00–28.88) 53.2±9.5 |

0.141* 0.086† |

| LVESVi, mL/m2, median (IQR) | 32.45 [23.40–40.00) | 36.30 [27.40–46.30) | < 0.0001* |

| LVEDVi, mL/m2, median (IQR) | 70.80 [63.70–80.60) | 80.60 [72.53–91.58) | < 0.0001* |

| Microvascular obstruction present, n (%) | 37 (43) | 127 (54) | 0.078‡ |

| Microvascular obstruction extent (%LV mass), mean±SD | 1.96±3.95 | 3.25±5.32 | 0.039* |

| Myocardial haemorrhage, n (%) | 17 (29) | 85 (45) | 0.032‡ |

| T1 remote zone (ms), mean±SD | 968.46±24.97 | 958.74±24.64 | 0.003† |

| T1 infarct zone, (ms), mean±SD | 1105.40±52.39 | 1091.20±51.04 | 0.042† |

| T1 core zone, (ms), mean±SD | 1001.05±74.43 | 995.68±51.18 | 0.615† |

| T2 remote zone (ms), mean±SD | 50.07±2.11 | 49.62±2.04 | 0.088† |

| T2 infarct zone (ms), mean±SD | 62.45±4.91 | 63.04±5.22 | 0.356† |

| T2 core zone (ms), mean±SD | 53.10±4.68 | 54.15±4.87 | 0.204† |

| MRI finding 6 months post-MI | |||

| Myocardial salvage index (%LV mass), median (IQR) Infarct size (%LV mass), median (IQR) |

64.20 [47.55–87.15) 9.70 [3.45–17.63) |

60.40 [43.80–82.30) 12.10 [4.40–19.90) |

0.169* 0.156* |

| LVEF% at 6 months, mean±SD | 63.93±9.13 | 61.15±9.41 | 0.025† |

| LVESVi at 6 months, mL/m2, median (IQR) | 26.55 [18.70–33.20) | 31.50 [22.68–40.93) | < 0.0001* |

| LVEDVi at 6 months, mL/m2, median (IQR) | 74.25 [63.60–80.80) | 83.70 [72.75–94.55) | < 0.0001* |

| Change in LVEDVi (6 months compared with 2 days), median (IQR) | 0.90 [−7.10 to 7.40) | 2.25 [−5.55 to 9.60) | 0.158* |

| Change in LVEDVi (6 months compared with 2 days≥20%), n (%) | 5 (6) | 15 (7) | 0.872‡ |

| Persistent myocardial haemorrhage, n (%): | |||

| None/resolved Persisting |

43 (88) 6 (12) |

121 (75) 41 (25) |

0.054‡ |

| T2 remote zone (ms), mean±SD | 49.94±2.48 | 49.64±2.28 | 0.328† |

| T2 infarct zone (ms), mean±SD | 56.41±3.95 | 56.05±4.24 | 0.512† |

| T2 core zone (ms), mean±SD | 45.72±4.31 | 47.80±3.57 | 0.194† |

LV volumes and ejection fraction on MRI at 2 days was available in 321 subjects. At 6 months, LV volumes were available in 294 subjects. Infarct size was available in 322 subjects on MRI at 2 days and 296 subjects at 6 months. Myocardial salvage index and LVEF at 6 months was available in 296 subjects. Presence/absence of microvascular obstruction was available in 324 subjects, extent of microvascular obstruction in 322 subjects, myocardial haemorrhage in 246 subjects and persistent myocardial haemorrhage in 211 subjects. T1 remote and infarct zone information was available in 288 subjects, and T1 core in 160 subjects. On MRI at 2 days, T2 remote/infarct zone information was available in 324 subjects, core zone in 192 subjects and at 6 months T2 remote, infarct, core zone was available in 297, 296 and 52 subjects, respectively.

*Mann-Whitney U test.

†Student’s t-test.

‡χ2 test.

LV, left ventricular; LVEDVi, LV end-diastolic volume index; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVESVi, LV end-systolic volume index; MI, myocardial infarction; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Of 372 patients with acute STEMI who were assessed for eligibility, 324 (87%) patients were enrolled. Reasons for non-enrolment are detailed in figure 1. There were no patients who presented with myocardial infarction with non-obstructive coronary arteries. Women accounted for 27% (n=87) of the cohort and had a mean age of 61±12.19 years. Twenty five (29%) women were young (age <55 years), which did not differ significantly from the proportion of men in the study with age <55 years (n=84; 35%), p=0.260. Primary PCI was performed in 302 (93%) subjects, the remainder had rescue PCI after failed thrombolysis (14; 4%) or PCI after successful thrombolysis (8; 2%)).

Baseline demographic and clinical features of the 324 patients with STEMI are shown in table 1. Women had higher baseline N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide levels, were less likely to have LAD territory infarctions and were less likely to have beta-blockers prescribed on discharge (all p<0.05). ECG, coronary physiology and angiographic characteristics are shown in table 2, and MRI findings are presented in table 3. The mean time between STEMI and baseline MRI was 2±1.90 days and did not differ between sexes (p=0.220).

Acute reperfusion outcomes in relation to sex

Compared with men, women were less likely to have TIMI myocardial perfusion grade ≤1 (20% vs 32%, OR: 0.52, 95% CI: 0.28 to 0.97, p=0.040), after adjustment for estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), reperfusion strategy (thrombolysis vs no thrombolysis), culprit artery territory (LAD/left main vs circumflex vs right coronary artery), age and ischaemic time. Consistent with this finding, female sex was a multivariable associate of lower corrected TIMI frame count (12.94 vs 17.65, β: −0.17, 95% CI: −0.28 to −0.05, p=0.004). There were no sex differences in incomplete ST-segment resolution on the ECG (OR: 0.89, p=0.743) (table 4). IMR and CFR measured directly in the culprit artery were similar in women and men (table 2).

Table 4.

Univariable and multivariable associations between female sex and (I) MRI surrogate outcomes and (II) acute reperfusion outcomes from the ECG, angiogram and invasive coronary physiology

| Crude | Adjusted | |||

| MRI outcomes 2 days post-STEMI | β/OR (95% CI) | P value | β/OR (95% CI) | P value |

| Infarct size (%LV mass) | −0.08 (−0.19 to 0.03) | 0.140 | −0.06 (−0.16 to 0.05) | 0.282 |

| LVEF% | 0.10 (−0.01 to 0.21) | 0.086 | 0.05 (−0.05 to 0.16) | 0.327 |

| LVESVi at 2 days, mL/m2 | −0.22 (−0.33 to −0.12) | < 0.0001 | −0.17 (−0.27 to −0.07) | 0.002 |

| LVEDVi at 2 days, mL/m2 | −0.30 (−0.40 to −0.19) | < 0.0001 | −0.26 (−0.36 to −0.20) | < 0.0001 |

| Microvascular obstruction present | 0.64 (0.39 to 1.05) | 0.079 | 0.60 (0.35 to 1.02) | 0.060 |

| Microvascular obstruction extent (%LV mass) | −0.12 (−0.22 to −0.01) | 0.039 | −0.10 (−0.21 to −0.01) | 0.077 |

| Myocardial haemorrhage present | 0.50 (0.27 to 0.95) | 0.033 | 0.52 (0.26 to 1.03) | 0.060 |

| T1 remote zone (ms) | 0.17 (0.06 to 0.29) | 0.003 | 0.18 (0.06 to 0.30) | 0.004 |

| T1 infarct zone (ms) | 0.12 (0.00 to 0.24) | 0.042 | 0.11 (−0.01 to 0.23) | 0.063 |

| T1 core zone (ms) | 0.04 (−0.12 to 0.20) | 0.615 | 0.07 (−0.09 to 0.23) | 0.398 |

| T2 remote zone (ms) | 0.10 (−0.01 to 0.20) | 0.088 | 0.10 (−0.02 to 0.21) | 0.089 |

| T2 infarct zone (ms) | −0.05 (−0.16 to 0.06) | 0.356 | −0.06 (−0.18 to 0.06) | 0.319 |

| T2 core zone (ms) | −0.09 (−0.23 to 0.05) | 0.204 | −0.10 (−0.26 to 0.05) | 0.176 |

| MRI outcomes 6 months post-STEMI | ||||

| Myocardial salvage index (%LV mass) | 0.08 (−0.03 to 0.20) | 0.151 | 0.08 (−0.04 to 0.20) | 0.206 |

| Infarct size (%LV mass) | −0.10 (−0.22 to 0.01) | 0.077 | −0.07 (−0.18 to 0.04) | 0.207 |

| LVEF% | 0.13 (0.02 to 0.25) | 0.025 | 0.11 (0.00 to 0.23) | 0.060 |

| LVESVi at 6 months, mL/m2 | −0.21 (−0.32 to −0.10) | < 0.0001 | −0.19 (−0.31 to −0.08) | 0.001 |

| LVEDVi at 6 months, mL/m2 | −0.27 (−0.38 to −0.16) | < 0.0001 | −0.26 (−0.37 to −0.15) | < 0.0001 |

| Change in LVEDVi>20% | 0.92 (0.32 to 2.62) | 0.872 | −0.08 (−0.19 to 0.04) | 0.206 |

| Persistent myocardial haemorrhage present | 0.48 (0.21 to 1.08) | 0.075 | 0.47 (0.20 to 1.13) | 0.092 |

| T2 remote zone (ms) | 0.06 (−0.06 to 0.17) | 0.328 | 0.08 (−0.04 to 0.20) | 0.193 |

| T2 infarct zone (ms) | 0.04 (−0.08 to 0.15) | 0.512 | 0.04 (−0.08 to 0.16) | 0.558 |

| T2 core zone (ms) | −0.18 (−0.46 to 0.10) | 0.194 | 0.01 (−0.40 to 0.42) | 0.946 |

| Angiography outcomes | ||||

| TIMI frame count post-PCI | −0.15 (−0.26 to −0.04) | 0.007 | −0.17 (−0.28 to −0.05) | 0.004 |

| TIMI myocardial perfusion grade post-PCI ≤1 | 0.51 (0.28 to 0.93) | 0.029 | 0.52 (0.28 to 0.97) | 0.040 |

| Invasive coronary physiology outcomes | ||||

| IMR >40(U) | 0.92 (0.51 to 1.64) | 0.771 | 0.90 (0.49 to 1.66) | 0.744 |

| IMR(U) | −0.07 (−0.18 to 0.05) | 0.247 | −0.09 (−0.20 to 0.03) | 0.161 |

| CFR≤2 | 0.94 (0.47 to 1.89) | 0.871 | 1.11 (0.54 to 2.30) | 0.777 |

| CFR | −0.03 (−0.14 to 0.09) | 0.667 | −0.00 (−0.13 to 0.12) | 0.951 |

| ECG outcomes | ||||

| Incomplete ST-segment resolution | 0.89 (0.44 to 1.80) | 0.743 | 1.17 (0.55 to 2.46) | 0.687 |

MRI outcomes at 6 months were adjusted for prescription of beta-blocker on discharge, eGFR, reperfusion strategy (thrombolysis vs no thrombolysis), culprit artery territory (LAD/left main vs circumflex vs right coronary artery), age and ischaemic time. All other outcomes were adjusted for eGFR, reperfusion strategy (thrombolysis vs no thrombolysis), culprit artery territory (LAD/left main vs circumflex vs right coronary artery), age and ischaemic time.

CFR, coronary flow reserve; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; IMR, Index of microcirculatory resistance; LV, left ventricular; LVEDVi, LV end-diastolic volume index; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVESVi, LV end-systolic volume index; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; TIMI, Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction.

Infarct pathology and sex-specific associations

Microvascular obstruction and myocardial haemorrhage

Microvascular obstruction revealed by MRI 2 days after reperfusion occurred in 164 subjects (70%) (table 3). The proportions of women and men affected by microvascular obstruction were similar (43% vs 54%, OR: 0.64, 95% CI: 0.39 to 1.05, p=0.079). In multivariable models including infarct territory (which differed significantly between sexes), the association between sex and the presence of microvascular obstruction remained non-significant (OR: 0.60, 95% CI: 0.35 to 1.02, p=0.060) (table 4).

Evaluable T2* maps on the baseline MRI were available in 246 patients (58 women, 67%; 188 men, 79%). Myocardial haemorrhage was present in 102 (41%) subjects, on baseline MRI, and occurred less frequently in women than men (29% vs 45%), but this difference was not significant after adjustment for eGFR, reperfusion strategy (thrombolysis vs no thrombolysis), culprit artery territory, age and ischaemic time (OR: 0.52, 95% CI: 0.26 to 1.03, p=0.060). Evaluable T2* maps on the 6-month MRI were available in 251 patients (61 women, 70%; 190 men, 55%). Persistent myocardial haemorrhage on the 6-month MRI occurred in 47 (22%) of subjects and was numerically lower in women (12% vs 25%), but this difference was not statistically significant (OR: 0.48, 95% CI: 0.21 to 1.08, p=0.075).

Remote zone inflammation

Female sex was a multivariable associate of higher T1 remote zone signal on baseline MRI (968.46 vs 958.74 ms, β: 0.18, 95% CI: 0.06 to 0.30, p=0.004). After adjustment for the same variables, T1 infarct zone signal was not associated with sex (β: 0.11, p=0.063). There were no sex differences in T1 core zone signal on baseline MRI, or T2 signal on MRI at baseline or at 6 months (table 4).

LV volumes and adverse remodelling

Adverse LV remodelling, defined as an increase in ≥20% LVEDV at 6 months from baseline, occurred in 6% of women and 7% of men (OR: 0.92, p=0.872). Women had smaller indexed LVEDVs than men 2 days (70.80 vs 80.60 mL/m2, β: −0.26, 95% CI: −0.36 to −0.20, p<0.0001) and 6 months post-MI (74.25 vs 83.70 mL/m2, β: −0.26, 95% CI: −0.37 to −0.15, p<0.0001). Women had smaller indexed LV end-systolic volumes than men 2 days (32.45 vs 36.30 mL/m2, β: −0.17, 95% CI: −0.27 to –0.07, p=0.002) and 6 months post-MI (26.55 vs 31.50 mL/m2, β: −0.19, 95% CI: −0.31 to −0.08, p<0.0001).

LVEF, Infarct size and myocardial salvage index

Infarct size, myocardial salvage and LV ejection fraction were similar in women and men at 2 days and 6 months post-MI (table 3).

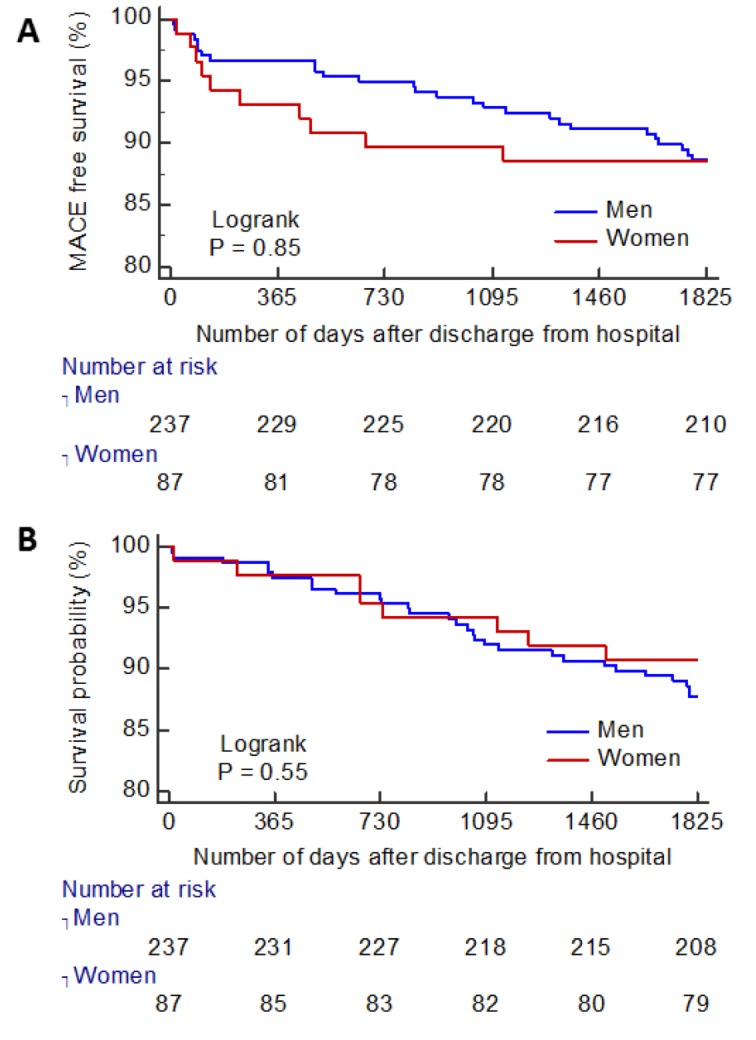

Health outcomes

In the landmark survival analysis with median 5-year follow-up, female sex was not associated with either MACE (women n=10 [11.5%] vs men n=30 [14.5%], HR: 0.92, 95% CI: 0.45 to 1.89, p=0.820), or all-cause death or first hospitalisation for heart failure postdischarge (n=11 [13%] compared with men n=36 [15%], HR: 0.80, 95% CI: 0.41 to 1.57, p=0.520) (figure 2).

Figure 2.

(A) Kaplan-Meier curve for MACE-free survival, after initial hospitalisation to 5-year follow-up. (B) Kaplan-Meier curve for survival free from all-cause death or the first heart failure hospitalisation to 5-year follow-up. MACE, major adverse cardiovascular event.

Discussion

We have undertaken a large, contemporary, prospective study of sex-based associations in acute reperfusion injury, infarct characteristics and long-term prognosis after STEMI. Anterior MI was more common in men and beta-blockers were prescribed less often in women. We observed no sex differences in acute reperfusion injury assessed by IMR or CFR, but angiographically corrected TIMI frame count was lower and TIMI myocardial perfusion grade was higher in women than men. On MRI performed 2 days and 6 months later, there were no differences in microvascular obstruction, myocardial haemorrhage, infarct size, myocardial salvage index, LV remodelling or LV function. 3 6Long-term health outcomes in women and men were similar.

Microvascular reperfusion injury in women post-STEMI

The angiographic finding of lower corrected TIMI frame count and higher myocardial perfusion grade in women was a surprise finding, and perhaps suggests that PCI was less effective in women than men. Prior studies have reported that women were more likely to have pre-infarct angina than men4 5 implicating ischaemic preconditioning as a plausible explanation.21 The comparatively low rates of pre-infarct angina, without sex differences (women 10% vs males 13%; p=0.507), do not implicate this explanation in our cohort. We considered whether sex differences in lesion plaque characteristics at the time of angiography may have contributed to the lower TIMI myocardial perfusion grade and higher corrected TIMI frame count in men. However, no sex differences were detected in culprit lesion plaque characterisation score, or total number of complex plaques (table 2). We also found no sex differences in intraprocedural thrombotic events, which is consistent with previous reports.17 In a previous study, male patients with STEMI had higher plaque burden than propensity-matched women, as revealed by virtual histology intravascular ultrasound22; however high-risk lesion characteristics such as thin cap fibroatheroma were similar in both sexes.22

Even though we observed angiographically lower corrected TIMI frame counts and higher TIMI myocardial perfusion grades at the end of the PCI procedure in women than men, there were no sex differences in invasive coronary physiology measurements of acute microvascular reperfusion injury, that is, IMR and CFR. We considered whether this result could be explained by men in our cohort having more LAD territory infarcts. However, even when the analysis was restricted to patients with IMR measured in the LAD, there was still no sex difference in IMR.

The inconsistency between the acute angiographic and invasive coronary physiology observations might be explained by angiography-based techniques for assessing microvascular function having lower specificity and poorer interobserver and intraobserver reproducibility, largely related to dependence on volume of contrast dye injected or force of injection, coronary artery size and haemodynamic conditions. Even though corrected TIMI frame count measured in the LAD was divided by 1.7 to correct for the relatively longer vessel length, it is plausible that the higher proportion of LAD infarcts in males may still have contributed to the higher corrected TIMI frame count in males. IMR has previously been shown to have better predictive utility for microvascular obstruction than angiographic parameters.23 The IMR and CFR results were consistent with the MRI findings. Furthermore, the CIs are narrow for the non-significant associations between sex and the presence of microvascular obstruction or myocardial haemorrhage, which suggests that type II statistical error was unlikely (table 4).

Microvascular reperfusion plays an important role in ameliorating adverse LV remodelling24 and prior literature suggests that LV remodelling is more favourable in women, potentially due to sex differences in modulation of the ischaemia-induced apoptotic cascade.25 In our cohort, LV remodelling was not significantly different between men and women. Furthermore, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide level at 6 months (a biomarker of adverse LV remodelling19) did not differ between women and men. We found that myocardial remote zone native T1 (a biomarker of inflammation and risk factor for adverse LV remodelling19) was higher in women. However, there were no sex differences in remote zone native T2. Taken together, the findings suggest that the sex differences in remote zone T1 may be explained by women generally having higher myocardial T1 values than men26 and not due to a higher degree of inflammation of the remote zone in women.

Our data contrast with those of Canali et al,4 who reported that women had more favourable microvascular obstruction extent, infarct size and myocardial salvage post-STEMI. Our study extends the findings of Canali et al4 by providing new information on coronary physiology acutely, myocardial haemorrhage at 2 days and 6 months, and long-term clinical outcomes.

In-hospital acute MI care and beta-blocker therapy

The door-to-balloon time, a measure of the efficiency of emergency in-hospital care for STEMI, was short and similar in women and men. Furthermore, in contrast to previous studies, ischaemic time (which is causally implicated in the development of microvascular obstruction) was similar in women and men in our contemporary cohort. Other in-hospital treatments were also similar. On the other hand, beta-blocker therapy was prescribed less often in women at discharge. The reasons for this sex-based difference are unclear. Beta-blocker therapy notably with metoprolol may reduce reperfusion injury and improve prognosis (including in women),27 and beta-blocker therapy post-MI is recommended in practice guidelines.28 Previous studies have found that women were less likely than men to adhere effectively to chronic medications including after MI.29 The difference in beta-blocker therapy serves another reminder of sex differences in post-MI care in contemporary practice.

Limitations

This is an observational study, so causality cannot be inferred. The data are from a single centre, but it is still likely to be representative of contemporary patients with STEMI in other centres. The study was not powered to demonstrate sex differences in clinical outcomes. We do not have information on medication adherence postdischarge and do not have information on the reason for beta-blockers being prescribed less often in women.

Conclusions

There were no sex differences in serial measures of microvascular reperfusion injury from acute invasive coronary physiology and MRI performed 2 days and 6 months later. LV remodelling and health outcomes were also similar. Beta-blocker therapy at discharge was prescribed less often in women than men, and anterior MI was more common in men.

openhrt-2018-000979supp001.docx (71.4KB, docx)

Footnotes

Contributors: AM wrote the manuscript, statistically analysed the results and interpreted the data. DC coordinated the study, obtained informed consent in all of the participants, coordinated and analysed the MRI scans. He collected the clinical data, interpreted the results and contributed to the manuscript. IF contributed to study design and contributed to the manuscript. NS contributed to study design. AM assessed the source data for serious adverse events during follow-up that were potentially relevant to the prespecified health outcomes. KM contributed to the analysis of the clinical MRI scans in patients with STEMI and contributed to the manuscript. JC contributed to the analysis of the clinical MRI scans in patients with STEMI and performed the angiographic analysis. CB is PI for the research grant from the British Heart Foundation and Chief Investigator for the clinical study. CB conceived the idea for the study, obtained the funding and ethics approvals. He participated in patient recruitment, collected clinical data and interpreted the results. CB takes responsibility for the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the British Heart Foundation (BHF) (Centre of Research Excellence Award [RE/18/6134217], BHF Project Grant [PG/11/2/28474]), the National Health Service and the Chief Scientist Office. CB was supported by a Senior Fellowship from the Scottish Funding Council. PW is supported by a BHF Intermediate Fellowship [FS/12/62/29889]. AM is supported by a BHF Clinical Research Training Fellowship [FS/16/74/32573].

Competing interests: CB: Research Grant—Significant; Based on an institutional agreement with the University of Glasgow, CB has acted as a consultant to Abbott, a manufacturer of diagnostic coronary guidewires. The company has offered a significant research grant in relation to a research project led by CB. The University of Glasgow holds a research agreement with Siemens Healthcare, which manufactured the MRI scanner used in this study. KO: Honoraria—Modest. KO has acted as consultant to Abbott.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Townsend N, Wilson L, Bhatnagar P, et al. Cardiovascular disease in Europe: epidemiological update 2016. Eur Heart J 2016;37:3232–45. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mehta LS, Beckie TM, DeVon HA, et al. American Heart Association cardiovascular disease in women and special populations Committee of the Council on clinical Cardiology, Council on epidemiology and prevention, Council on cardiovascular and stroke Nursing, and Council on quality of care and outcomes research. acute myocardial infarction in women: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2016;133:916–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alabas OA, Gale CP, Hall M, et al. Sex differences in treatments, relative survival, and excess mortality following acute myocardial infarction: national cohort study using the SWEDEHEART registry. J Am Heart Assoc 2017;6:e007123 10.1161/JAHA.117.007123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Canali E, Masci P, Bogaert J, et al. Impact of gender differences on myocardial salvage and post-ischaemic left ventricular remodelling after primary coronary angioplasty: new insights from cardiovascular magnetic resonance. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2012;13:948–53. 10.1093/ehjci/jes087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mehilli J, Ndrepepa G, Kastrati A, et al. Gender and myocardial salvage after reperfusion treatment in acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005;45:828–31. 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.11.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tomey MI, Mehran R, Brener SJ, et al. Sex, adverse cardiac events, and infarct size in anterior myocardial infarction: an analysis of intracoronary abciximab and aspiration thrombectomy in patients with large anterior myocardial infarction (INFUSE-AMI). Am Heart J 2015;169:86–93. 10.1016/j.ahj.2014.06.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eitel I, Desch S, de Waha S, et al. Sex differences in myocardial salvage and clinical outcome in patients with acute reperfused ST-elevation myocardial infarction: advances in cardiovascular imaging. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2012;5:119–26. 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.111.965467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kosmidou I, Redfors B, Selker HP, et al. Infarct size, left ventricular function, and prognosis in women compared to men after primary percutaneous coronary intervention in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: results from an individual patient-level pooled analysis of 10 randomized trials. Eur Heart J 2017;38:1656–63. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bugiardini R, Ricci B, Cenko E, et al. Delayed care and mortality among women and men with myocardial infarction. J Am Heart Assoc 2017;6:e005968 10.1161/JAHA.117.005968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.D'Onofrio G, Safdar B, Lichtman JH, et al. Sex differences in reperfusion in young patients with ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction: results from the VIRGO study. Circulation 2015;131:1324–32. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.012293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lichtman JH, Leifheit EC, Safdar B, et al. Sex differences in the presentation and perception of symptoms among young patients with myocardial infarction: evidence from the VIRGO study (variation in recovery: role of gender on outcomes of young AMI patients). Circulation 2018;137:781–90. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.031650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khera S, Kolte D, Gupta T, et al. Temporal Trends and Sex Differences in Revascularization and Outcomes of ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction in Younger Adults in the United States. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;66:1961–72. 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.08.865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, et al. 2017 ESC guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: the task Force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2018;39:119–77. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eitel I, Desch S, Fuernau G, et al. Prognostic significance and determinants of myocardial salvage assessed by cardiovascular magnetic resonance in acute reperfused myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;55:2470–9. 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.01.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carrick D, Haig C, Ahmed N, et al. Comparative prognostic utility of indexes of microvascular function alone or in combination in patients with an acute ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction. Circulation 2016;134:1833–47. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.022603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keeley EC, Mehran R, Brener SJ, et al. Impact of multiple complex plaques on short- and long-term clinical outcomes in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (from the Harmonizing Outcomes With Revascularization and Stents in Acute Myocardial Infarction [HORIZONS-AMI] Trial). Am J Cardiol 2014;113:1621–7. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.02.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schoos MM, Mehran R, Dangas GD, et al. Gender differences in associations between intraprocedural thrombotic events during percutaneous coronary intervention and adverse outcomes. Am J Cardiol 2016;118:1661–8. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2016.08.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Verhaert D, Thavendiranathan P, Giri S, et al. Direct T2 quantification of myocardial edema in acute ischemic injury. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2011;4:269–78. 10.1016/j.jcmg.2010.09.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carrick D, Haig C, Rauhalammi S, et al. Pathophysiology of LV Remodeling in Survivors of STEMI: Inflammation, Remote Myocardium, and Prognosis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2015;8:779–89. 10.1016/j.jcmg.2015.03.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kellman P, Arai AE, McVeigh ER, et al. Phase-sensitive inversion recovery for detecting myocardial infarction using gadolinium-delayed hyperenhancement. Magn Reson Med 2002;47:372–83. 10.1002/mrm.10051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ann SH, De Jin C, Singh GB, et al. Gender differences in plaque characteristics of culprit lesions in patients with ST elevation myocardial infarction. Heart Vessels 2016;31:1767–75. 10.1007/s00380-016-0806-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bolognese L, Carrabba N, Parodi G, et al. Impact of microvascular dysfunction on left ventricular remodeling and long-term clinical outcome after primary coronary angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction. Circulation 2004;109:1121–6. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000118496.44135.A7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dargie HJ. Effect of carvedilol on outcome after myocardial infarction in patients with left-ventricular dysfunction: the Capricorn randomised trial. Lancet 2001;357:1385–90. 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04560-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Biondi-Zoccai GGL, Abate A, Bussani R, et al. Reduced post-infarction myocardial apoptosis in women: a clue to their different clinical course? Heart 2005;91:99–101. 10.1136/hrt.2003.018754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosmini S, Bulluck H, Captur G, et al. Myocardial native T1 and extracellular volume with healthy ageing and gender. Eur Heart J Cardiovascular Imaging 2018;19:615–21. 10.1093/ehjci/jey034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carrick D, Haig C, Carberry J, et al. Microvascular resistance of the culprit coronary artery in acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction. JCI Insight 2016;1:e85768 10.1172/jci.insight.85768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O'Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: Executive summary: a report of the American College of cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. Circulation 2013;127:529–55. 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182742c84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eindhoven DC, Hilt AD, Zwaan TC, et al. Age and gender differences in medical adherence after myocardial infarction: Women do not receive optimal treatment - The Netherlands claims database. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2018;25:181–9. 10.1177/2047487317744363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ottani F, Galvani M, Ferrini D, et al. Prodromal angina limits infarct size. A role for ischemic preconditioning. Circulation 1995;91:291–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

openhrt-2018-000979supp001.docx (71.4KB, docx)