Abstract

We developed a series of small group workshops that aim to facilitate communication during very challenging ethically sensitive scenarios within a Neonatal-Perinatal Medicine (NPM) postgraduate curriculum at the University of Ottawa. These workshops are called Scenario-Oriented Learning in Ethics (SOLE). This educational intervention aims to focus attention on the learner’s needs and to help them recognize, define, and view each communicative or behavioural mistake as an occasion to achieve a personal-defined learning goal in a controlled environment free of judgement. The goal of this commentary is to describe the importance of timely interruptions during the scenarios allowing mini concurrent-guided debriefing-feedback by focusing upon trainees’ communication mistakes, utilizing them as valuable learning opportunities.

Keywords: Neonatal perinatal medicine, Interactive reflection, Experiential learning, Communication errors, Medical education, Clinical ethics

Many clinical encounters in medicine, and especially in Neonatal-Perinatal Medicine (NPM), are often filled with emotionally demanding interactions between patients and their parents/caregivers and physicians, where both parties face a difficult decision. Positive resolution of the dilemma raised during these encounters—which may reflect a variety of personal values and professional perspectives—requires highly sensitive communication from the health care professionals to engage with the patient and their parents/caregivers in an open and honest dialogue. Achieving high-quality communication during such delicate situations involves the following complex elements: building trust in a relationship, supporting emotional reactions when delivering difficult news, engaging parents/caregivers in a shared decision making process, and adhering to ethical and professionalism concepts (1). While communication strategies such as introducing ourselves to parents/caregivers, using their baby’s first name, shaking hands, sitting down, and acknowledging the mother and father’s role in the care of their baby may help to navigate ethically challenging situations (2,3), they are not sufficient and have the potential to turn artificial (3). In fact, these commonly recognized appropriate strategies could lead to omissions and misunderstandings when used at the wrong time or context during a highly sensitive encounter. Learners and health care professionals are often apprehensive to engage in these situations as they are worried about making mistakes.

We argue that these mistakes must be valued as educational tools, and are in fact precious opportunities to genuinely reflect, learn, and adjust communication and actions. We also defend timely interruptions when communicative laps occur; this pause may better support learning by using the vivid memory of the behaviour/emotion attached to what happened, rather than waiting for when—at the end of the encounter—memory fades. Learning from these opportunities and tailoring communication to the needs of others is a key defining factor in the communication style of excellent NPM professionals. Such in-depth commitment cannot be feigned and includes open-mindedness to the whole reality of the parents/caregivers and their child (4). We emphasize the reconceptualization of mistakes into valuable learning opportunities, using short in-action debriefing and concurrent feedback moments compared to a final debriefing-feedback session promoted during learning technical skills (5,6). This commentary aims to describe the rationale supporting this method of learning for teaching communication skills.

CONCEPTUALIZING MISTAKES AS PRECIOUS OPPORTUNITIES: A CONSTRUCTIVISM APPROACH

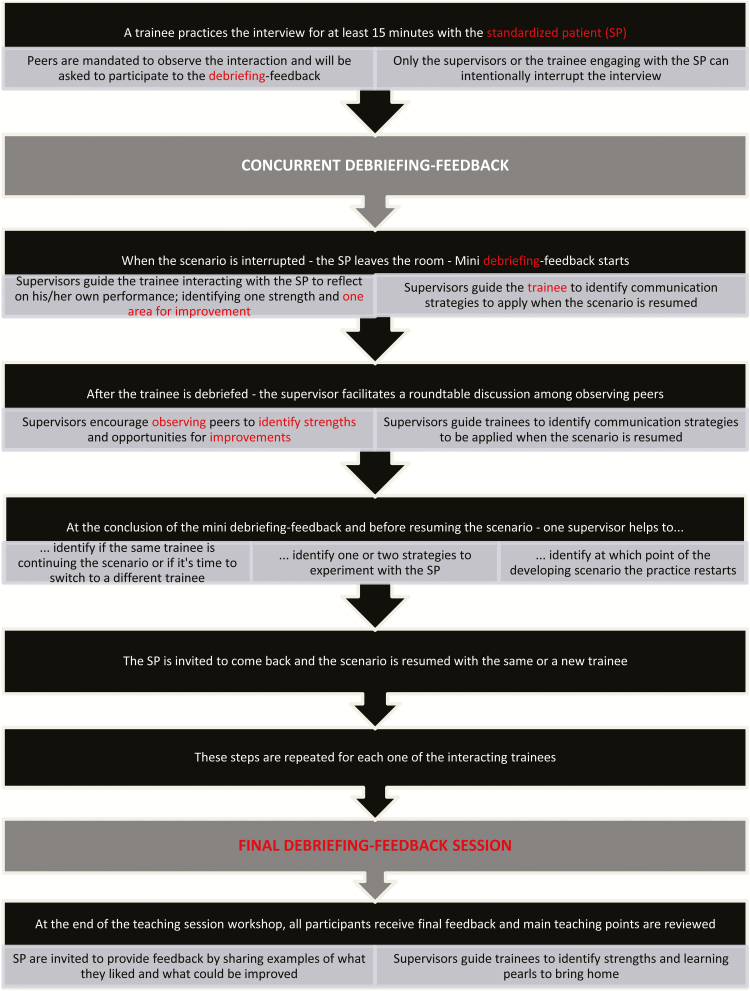

Experiential and relational learning are important to support the crucial ability to adapt our communication to the patient’s or parent’s needs (7,8) and to avoid the devastating effects of improper communication that could have long-term consequences for the parents/caregivers and their infants. To this end, we have created Scenario-Oriented Learning in Ethics (SOLE) workshops based on real-life ethically challenging clinical scenarios to allow NPM trainees to practice with trained standardized patients (SP) (who act as a parent of a newborn), reflect and receive guidance to enhance their learning of ethical communication skills (9). The SOLE small-group workshop is designed to take 3 hours, using two supervisors and one SP for a group of four to six trainees. Each trainee has the opportunity to interact with the SP while being directly observed by peers and supervisors. These sessions mimic an action-oriented flexible real-world setting, and integrate the use of reflective practice. The challenging nature of the scenarios used in these workshops warrants a strategy (via concurrent and final debriefing-feedback) that safely relieves the emotional pressure generated during the interactions while maximizing learning (5,6). Figure 1 illustrates the interaction of observation and mini debriefing-feedback periods within the evolving SOLE workshop.

Figure 1.

Dynamic interaction scheme of the mini debriefing-feedback during a Scenario-Oriented Learning in Ethics (SOLE) workshop.

During the unfolding of the simulated scenarios, we realized that the difficulties experienced by the participants were not just the clinical case itself, but rather the complexity of communication in dealing with the multiple layers of emotions, uncertainty, doubts, and misunderstandings included in these encounters in a constantly evolving situation. During such demanding situations and as it happens in clinical practice, participants were often making ‘errors’ while communicating (10), e.g., displaying subtle imprecise positioning and body language; not detecting and inadequately responding to verbal and nonverbal cues that a parent in distress displays; using inappropriate and judgemental comments in response to a parental action; or, their inability to incorporate multiple perspectives when exploring a newborn’s best interest (1).

In accordance with a constructivist perspective in education (11), we believe that learners’ misinterpretations and inaccuracies can be reconceptualized as the optimal ‘milieu’ to guide learning. By being constructed as opportunities for self-reflection and learning, mistakes represent an innovative way to challenge the classical negative connotation of making errors. When mistakes—often performance-related and independent from previous knowledge—are caught at the right moment, and explored and understood, they become a powerful true source of strength, dynamic knowledge, and ideas (12). Indeed, when an adult trainee makes a communicative error, this may reflect either their inexperience, some preconceived views/values, or their lack of previous established knowledge on the subject. To achieve this important teaching goal, we introduced deliberate interruptions with short concurrent mini debriefing-feedback during the SOLE workshops. They may occur as often as needed, spurred by the trainee to seek support in order to overcome their own difficulty to continue the encounter, or by the supervisor to reinforce a meaningful teaching point. During these short self-reflection interruptions, participants engage in critical thinking and attempt to clarify the meaning of their experiences in relation to self, and then self in relation to the world (4). These reflective pauses require deeper processing than passive participation, and facilitate the retention of effective communication and conflict resolution skills (13). The participant learns to bring the freshly lived unconscious emotional reactions to a conscious level of analysis through reflective reasoning and better acknowledge all the dimensions at play during the encounter.

Although these interruptions may be seen as disruptive for the flow of the scenario, research does not universally validate this concern (14). In fact, the specific nature of the communication skills to be learned calls for these learner-oriented interruptions to maximize the relational and experiential learning (7,8). For learning technical skills, final debriefing-feedback appears to be the method of choice rather than using vivid emotional (but often unconscious) reactions (6). However, when final debriefing-feedback is used for learning communication skills, the power of these precious opportunities is lost: emotional and physical reactions triggered during these challenging interactions are often short lived and often forgotten at the end of a scenario and cannot be used to promote a deeper level of learning.

CONCLUSION

Health care professionals share the constant need to learn how to skillfully communicate during challenging clinical encounters. This article describes our reconceptualized educational method conceived for subspecialty postgraduate trainees in our Neonatal-Perinatal Medicine Program at the University of Ottawa; teachers in many other health care domains and jurisdictions could use these scenario-oriented workshops. The exposure to diverse patients/families’ values and priorities enables participants to reflect and harmonize their communication to the whole reality of each situation they experience. Though some literature has demonstrated advancements in terms of improving technical communication skills taught during unique encounters (10), the focus of our SOLE workshops is on the dynamic human aspect of the parents/caregivers (acted by an SP) and the trainee participants. To err during interpersonal interactions is a common occurrence and we promote the use of these errors as precious learning opportunities for the trainees (12).

For learners experiencing the consequences of their actions directly from the SP’s reaction, and then being expected to pause and reflect to build their own learning from their mistake, the SOLE case can be very demanding emotionally. Nonetheless, we noticed, as described by Boyd, that learners’ acceptance of the constructive criticism ultimately encouraged self-correction (15). Crucial learning occurs when one builds from personal misguided action with tailoring and adapting responses during moments of interaction. Self-understanding error—without shame or embarrassment—is vital to improve clinical practice and quality of care. In order to allow for full accountability, a mishap needs to be carefully analyzed, not underestimated nor justified. The critical yet positive attitude in converting a mistake to a precious opportunity has the potential to improve ethical and professional growth, motivate our daily action, and ultimately have a positive impact on the physician–patient/parent/caregiver interaction and the care provided.

We have reached the final step of developing a validated assessment tool for communication skills to reliably assess trainees’ competency levels and examine whether participation in a SOLE can affect communication skills as well as trainees’ behaviour. The project has been designed according to modern validity principles—content, response process, internal structure, and in relation to other variables and consequences—where evidence that supports a particular interpretation of the results is collected. This is part of a larger process that rigorously evaluates the effect of our longitudinal curriculum in terms of learning and behaviour changes. Our wish is to encourage educators to develop a curriculum integrating a variety of teaching methods including learning from all sorts of errors.

The research work associated with the Neonatal Ethics Teaching Program (NETP) is reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Board at the Children Hospital of Eastern Ontario and the Ottawa Hospital Research Institute.

Financial Disclosure

TD, EF, and GPM were granted funds from the University of Ottawa to implement the Neonatal Ethics Teaching Program in the Neonatal Perinatal Medicine Residency Program.

Declaration of Interest

The authors contributed equally to the genesis, preparation, and critical revision of the manuscript, and do not have any conflicts of interest to declare.

Notes on Contributors

EF is a neonatologist and Associate Professor at the University of Ottawa. She is affiliated with the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario and The Ottawa Hospital Research Institutes; her academic interests revolve around the Neonatal Ethics Teaching Program for NICU postgraduate trainees, with focus on parents-physician communication. KR is a Credentialed Evaluator with the Canadian Evaluation Society having worked in research and evaluation for many years with experience in a variety of medical education contexts. Her work centres primarily on program theory, implementation, quality, and change management. GPM is a neonatologist and Associate Professor at the University of Ottawa. He is a Clinical Investigator with the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario Research Institute and Ottawa Hospital Research Institute; his main areas of academic interest are post-graduate medical education and bioethics with a focus on working with families when their baby may be born at an extremely low gestational age. TD is an Associate Professor of Pediatrics and neonatologist at the University of Ottawa, implemented the Neonatal Ethics Teaching Program in collaboration with EF and GPM. He focuses his research on exploring teaching strategies to help educators to better teach and assess clinical ethics and communication.

References

- 1. Daboval T, Shidler S. Ethical framework for shared decision making in the neonatal intensive care unit: Communicative ethics. Paediatr Child Health 2014;19(6):302–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Janvier A, Lantos J. Ethics and etiquette in neonatal intensive care. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(9):857–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kahn MW. Etiquette-based medicine. N Engl J Med 2008;358(19):1988–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Giussani L. The Risk of Education: Discovering Our Ultimate Destiny. New York:The Crossroad Publishing Company; 2001;144 pp. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sawyer T, Eppich W, Brett-Fleegler M, Grant V, Cheng A. More than one way to debrief: A critical review of healthcare simulation debriefing methods. Simul Healthc 2016;11(3):209–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Walsh CM, Ling SC, Wang CS, Carnahan H. Concurrent versus terminal feedback: It may be better to wait. Acad Med 2009;84 (10 Suppl):S54–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Browning D, Solomon M. Relational learning in pediatric palliative care: Transformative education and the culture of medicine. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin Notrh Am 2006;15:795–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ellman MS, Fortin AH VI. Benefits of teaching medical students how to communicate with patients having serious illness: Comparison of two approaches to experiential, skill-based, and self-reflective learning. Yale J Biol Med 2012;85(2):261–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ferretti E, Rohde K, Moore G, Daboval T. The birth of scenario-oriented learning in ethics. Med Educ 2015;49(5):517–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Stokes TA, Watson KL, Boss RD. Teaching antenatal counseling skills to neonatal providers. Semin Perinatol 2014;38(1):47–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dennick R. Twelve tips for incorporating educational theory into teaching practices. Med Teach 2012;34(8):618–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zunzarren G. The error as a problem or as teaching strategy. Procedia - Soc Behav Sci 2012;46:3209–14. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Butani L, Blankenburg R, Long M. Stimulating reflective practice among your learners. Pediatrics 2013;131(2):204–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gonzalez C. Learning to make decisions in dynamic environments: Effects of time constraints and cognitive abilities. Hum Factors 2004;46(3):449–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Boyd EM, Fales AW. Reflective learning key to learning from experience. J Humanist Psychol 1983;23(2):99–117. [Google Scholar]