Abstract

One of the implicit assumptions in survey research is lower response rates by sexual minorities than non-minorities. With rapidly changing public attitudes towards same-sex marriage, we reconsider this assumption. We used data from the 2013 and 2014 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) that include contact history data for all sample families (n=117,589) as well as sexual orientation information about adults sampled from responding families (n=71,110). We created proxy nonresponse indicators based on contact efforts and reluctance from contact history data and linked them to sexual orientation of the sample adult and simulated nonresponse. The data did not support the assumption: straight adults were more difficult to get cooperation from than non-straights. With female sexual minorities showing higher nonresponse than the male counterpart, special considerations are required. Replication analyses may provide insights into what factors influence study participation decisions, which will inform how nonresponse may impact the accuracy of research findings.

Keywords: Data Interpretation, Statistical, Minority Groups, Public Health Informatics, Vital Statistics, Healthcare Disparities

Introduction

There is an increasing need for collecting health data from sexual minorities in order to understand outcomes and challenges unique to that group (Clift and Kirby 2012; Cochran and Mays 2000; Dahlhamer et al. 2016; Dilley et al. 2010; Fredriksen-Goldsen et al. 2013; Sell and Holliday 2014). In fact, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender (LGBT) health is one of the objectives of Healthy People 2020 (https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/lesbian-gay-bisexual-and-transgender-health). Meanwhile, an implicit yet prevailing assumption in data collection is that sexual minorities are hard to survey due to social stigma, often leading to an expectation of lower participation rates (i.e., higher unit nonresponse rates) (Magnani et al. 2005; Meyer and Wilson 2009; Tourangeau 2014). This assumption appears to be influenced by somewhat dated studies on participation bias in HIV-related sexual behavior research (Catania et al. 1990; Herold and Way 1998).

However, this stigma may no longer be dominant, as the majority of the public now supports same-sex marriage (Flores 2015). According to Pew Research Center (2016), 35% of the population supported same-sex marriage while 57% opposed in 2001; these numbers changed to 55% support and 37% oppose in 2016. With this change in the larger social context, recent studies report lower and decreasing item nonresponse rates on sexual orientation questions, which once were viewed as highly sensitive and difficult to ask (Dahlhamer et al. 2014; Fredriksen-Goldsen and Kim 2015; Jans et al. 2015; Kim and Fredriksen-Goldsen 2014). A study of a HIV positive cohort also offers a point against the assumed stigma noted above: the participation consent rate was reported to be higher for sexual minorities than the counterpart (Raboud et al. 2013). At the same time, an increasing number of large-scale surveys have started to ask sexual orientation questions (e.g., the National Health Interview Survey), allowing comparisons by sexual orientation. If the assumption about sexual minorities’ lower unit response rates holds, these comparisons may be subject to nonresponse biases stemming from differential response rates by sexual orientation. To the best of our knowledge, this assumption does not rest on current evidence. The trends in public opinion towards same-sex marriage reported by Pew Research Center suggest it may be time to reconsider the assumption of lower unit response rates by sexual minorities.

Increasingly, surveys have started to collect paradata, which includes information about the interview process itself (e.g., contact history) (Kreuter, Couper, and Lyberg 2010). This type of data is proven to be useful for understanding nonresponse (Kreuter et al. 2010; Lee et al. 2009). In particular, two major dimensions of nonresponse one can study in contact history are: contactability (e.g., number of contact attempts) and cooperation (e.g., reluctance, refusal), which are theorized to arise due to different reasons (Groves 2006). With paradata, it is possible to identify respondents that are difficult to contact and/or reluctant to the interview request and use these respondents as proxies for true nonrespondents (Curtin, Presser, and Singer 2000; Curtin, Presser, and Singer 2005;Davern, 2013; Johnson and Wislar, 2012; Keeter et al. 2000; Peytchev, Peytcheva, and Groves 2010; U.S. Federal Committee on Statistical Methodology, 2001; Whitman and Halbesleben, 2013). Although this nonresponse assessment method has its advantages over other methods, one should be aware that it does not allow to assess the nonresponse bias with respect to the complete sample (Groves 2006). Therefore, we examine sexual orientation as a correlate of nonresponse using proxy nonresponse indicators from contact history. In other words, this analysis provides first insight about the level of required efforts by sexual orientation among the respondents to investigate whether the nonresponse assumption for sexual minorities has support. To simulate the potential nonresponse bias by sexual orientation, we use the logic is that without intensive efforts, hard to reach and persuade respondents would have been nonrespondents.

This paper uses a health survey that collects sexual orientation as well as contact history data and assess the nonresponse assumption for sexual minorities. Specifically, we examine 1) whether there is a systematic association between proxy nonresponse indicators and respondents’ sexual orientation, 2) the magnitude of potential nonresponse bias, and 3) whether the nonresponse bias differs by sexual orientation.

Methods

Data

Data came from the 2013 and 2014 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2014) for two reasons. First, sexual orientation questions were implemented in NHIS for the first time in 2013. Second, conducting analysis in two different years provides an opportunity to ascertain replicability of the results. The data are used as follows.

Among a number of NHIS data components, four data sets are used: 1) paradata, 2) family data, 3) person data and 4) sample adult (SA) data. NHIS paradata record the interview process, such as the number of contact attempts, contact mode and strategies, interviewers’ assessment of reluctance, and the outcome from the final contact attempt (National Center for Health Statistics 2014; 2015). Paradata are available for all families to whom contact attempts were made, regardless of whether they participated in NHIS. NHIS 2013 paradata indicate that there are 56,115 families eligible for the interview. From among these 56,115 families, contact history information is available for 55,843 families: 42,471 (76.1%) families completed family interviews, 2,277 (4.1%) never been contacted; 9,080 (16.3%) refused; and 2,015 (3.6%) did not participate for other reasons (e.g., language problem). In NHIS 2014, 61,937 families were eligible and 61,746 had contact history data. Among them, 45,768 (74.1%) completed family interview, 2,985 (4.8%) never been contacted, 10,828 (17.5%) refused and 2,165 (3.5%) did not participate for other reasons. Although interviewers made observations on a large proportion of the families who were never contacted in both years, 904 and 919 families in 2013 and 2014, respectively, were without interviewer observation data and, hence, without a reluctance indicator. Family and person data are derived from the family interviews. From responding families (i.e., those completing family interviews), NHIS samples an adult randomly for an extended interview, which includes sexual orientation questions. When combined with family and person data, SA data provide substantive health and socio-demographic information. Of the adults sampled from 42,417 and 45,768 responding families in 2013 and 2014, respectively, 34,459 (81.2%) and 36,651 (80.1%) completed SA interviews.

Measures

Proxy Nonresponse Indicators.

Proxy nonresponse indicators consider two dimensions of nonresponse: contactability and reluctance. First, for contactability, we used the number of total contact attempts. As reported in Table 1, on average, families were contacted 5.1 times in 2013 and 6.4 times in 2014. In our analysis, those in the 4th quartile of the contact attempt numbers (equating to 7 or more attempts for 2013 and 8 or more for 2014) were categorized as low contactability, and the rest as high contactability. In both years, responding families were associated with fewer contact attempt numbers than nonresponding families (4.3 vs. 7.7 for 2013; 5.9 vs. 7.8 for 2014). Naturally, the proportion of low contactability cases were lower for responding than nonresponding families (19.2% vs. 49.6% for 2013; 24.6% vs. 43.1% for 2014).

Table 1.

Contactability and Reluctance Measures for All Eligible Families, Families Completing Family Interviews and Families Not Completing Family Interviews in National Health Interview Survey 2013 and 2014a

| All eligible families | Families completing family interviews | Families not completing family interviews | ||||

| 2013 | 2014 | 2013 | 2014 | 2013 | 2014 | |

| n contact attempted | 55,843 | 61,746 | 42,471 | 45,768 | 13,372 | 15,978 |

| Contactability | ||||||

| Avg. no. contact attempts | 5.1 | 6.4 | 4.3 | 5.9 | 7.7 | 7.8 |

| Low contactability b | 26.5% | 29.4% | 19.2% | 24.6% | 49.6% | 43.1% |

| n at least one contact made | 54,939 | 60,827 | 12,652 | 45,628 | 42,287 | 15,199 |

| Reluctance | 58.8% | 58.0% | 50.7% | 49.6% | 85.7% | 83.1% |

| Contactability & Reluctance | ||||||

| Reluctant & Low contact. | 20.9% | 22.0% | 14.7% | 17.7% | 42.0% | 34.9% |

| Reluctant & High contact. | 37.8% | 36.0% | 36.1% | 31.9% | 43.7% | 48.2% |

| Not reluctant & Low contact. | 5.3% | 7.2% | 4.5% | 6.9% | 8.1% | 8.3% |

| Not reluctant & High contact. | 35.9% | 34.8% | 44.8% | 43.5% | 6.2% | 8.6% |

| Total | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% |

Data Source: CDC/NCHS, National Health Interview Survey, 2013, 2014

Unweighted estimates

7 or more attempts for 2013; 8 or more attempts for 2014

Second, the reluctance measure was created based on interviewer observation across all contact attempts per family. When interviewer observation indicated that families expressed lack of interest, too busy or not having time, privacy or anti-government concerns, hostility, or uncertainty about the survey or that interviewers experienced difficulties scheduling interview appointments or respondents’ breaking scheduled appointments, we considered these as reluctant and the remainder as not reluctant. Overall, Table 1 shows that a little less than 60% of the families showed some sign of reluctance. This rate was lower for responding than nonresponding families by over 30 percent point in both years (50.7% vs. 85.7% for 2013; 49.6% vs. 83.1% for 2014).

Third, we combined these two indicators into one with the following categories: 1) reluctant and low contactability; 2) reluctant and high contactability, 3) not reluctant and low contactability; 4) not reluctant and high contactability, with the first category considered as the most difficult to obtain a response and the last as the least difficult. When reflecting these proxy nonresponse indicators with the actual response status of family interviews, they appear as imperfect yet reasonable measures for true nonresponse. Table 1 shows that the rate of most difficult cases was two to three times larger for nonresponding than responding families (14.7% vs. 42.0% for 2013; 17.7% vs. 34.9% for 2014). Moreover, while almost half of the responding families were classified as least difficult, less than one of ten nonresponding families were classified so.

Sexual Orientation.

The sexual orientation question in NHIS asks SAs, “Which of the following best represents how you think of yourself?” with five response options: (1) gay/lesbian, (2) straight, that is, not gay, (3) bisexual, (4) something else, and (5) I don’t know (National Center for Health Statistics 2014). This study combines gay/lesbian, bisexual and something else as non-straight. Those who chose “I don’t know” or refused to answer and those whose sexual orientation was not ascertained due to interview break-offs were excluded as item nonresponse. Item nonresponse rates on sexual orientation were similar between 2013 and 2014 at 3.3% and 3.1%. Combined with gender data, each SA was further classified as straight male, non-straight male, straight female or non-straight female. A total of 1,806 SAs were identified as non-straight, roughly evenly split between males and females (see Appendix Table S1).

Health Characteristics.

We assessed nonresponse bias on health status, behaviors and care utilization. For health status, we used self-rated health (combined fair/poor health); having any of the following chronic conditions: diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, cancer, arthritis, ulcer or epilepsy; limited in any ways; experiencing sleep problems last week; moderate or high psychological distress in the past 30 days based on the Kessler-6 inventory (Kessler et al. 2002); and obesity. Any moderate or vigorous activities last week, current smoking status and binge drinking in the past year were used as health risk behaviors. For health care and utilization, we considered current health insurance coverage; whether visiting doctor’s office 4 or more times in the past 12 months; whether stayed at ER in the past 12 months; and whether not being able to afford needed care (prescription medicine, mental health care, dental care, eyeglasses, seeing a specialist, and follow-up care) in the past 12 months.

Appendix Table S1 includes sexual orientation, other socio-demographic characteristics as well as health characteristics SAs from NHIS 2013 and 2014 used in this study. The sample compositions are similar between these two years.

Analysis Steps

Analysis is conducted using SAS 9.2 at the SA level using the combined paradata, family, person and SA data. It should be noted that nonresponse below is based on proxy indicators which reflect true nonresponse shown in Table 1, not on true nonresponse itself.

First, proxy nonresponse indicators were examined by respondents’ sexual orientation and by its interactions with age and race/ethnicity. This association between sexual orientation and nonresponse was further examined in logistic regression that controlled for well-known correlates of nonresponse, including age, race/ethnicity, family structure, education, employment status, poverty status, home ownership and the place of residence (Kreuter et al. 2009). The second step examined potential nonresponse bias first by comparing SAs from the least difficult families against SAs from other families with Rao-Scott χ2 test and also by the relative bias calculated as: , where y1 is the health outcome estimates based on the least difficult families and y on all families. The idea behind relative bias is whether not making extensive efforts, such as increased contact attempts and/or refusal conversion, would have affected the substantive health characters. Hence, a positive relative bias means that not making the efforts results incorrectly producing estimates higher than what should be. Last, we compared the relative bias by sexual orientation.

Given that NHIS data are designed to represent the population, appropriate weights and sample design variables were incorporated in analysis. Because the results from 2013 and 2014 were consistent, we pooled 2013 and 2014 data for a higher level of statistical power.

Results

Sexual Orientation as a Correlate of Nonresponse

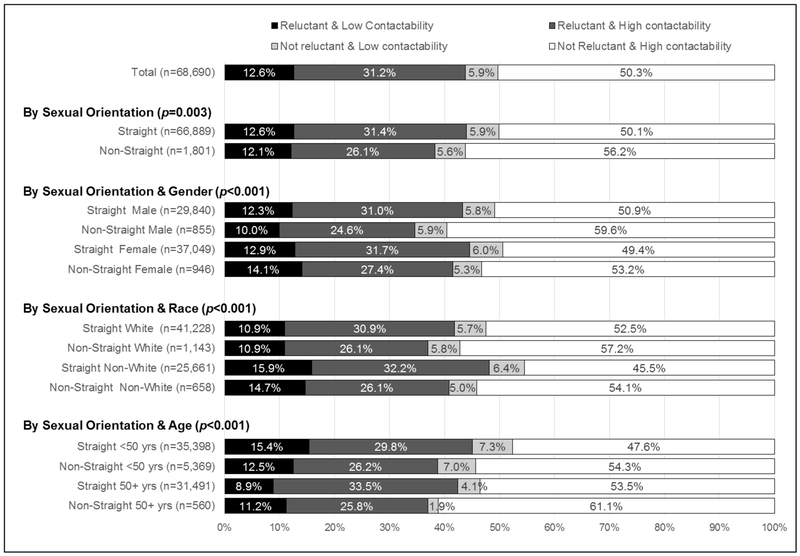

About 2.5% (SE: 0.1%) SAs were identified with non-straight, roughly evenly split between nonstraight males and females in both years. On average, 4.7 contacts were made to the families with SAs with little to no difference by SAs’ sexual orientation (F=0.78, df=3, P=0.505): 4.7, 4.5, 4.7, and 4.7 contacts made to families with straight male, non-straight male, straight female and non-straight female SAs. The low contactability did not differ by sexual orientation (Rao-Scott χ2=5.5, df=3, P=0.138). However, reluctance differed significantly (Rao-Scott χ2=20.7, df=3, P<0.001; also as seen in Figure 1, where the two dark shades indicate reluctant cases). Families with straight SAs were more reluctant than those with non-straight SAs: the highest reluctance rate at 43.4% (= 12.1 %+31.4%) from families with straight female SAs, followed by straight males (43.3%), non-straight females (41.5%) and non-straight males (34.6%) (Rao-Scott χ2=32.5, df=3, P<0.001).

Figure 1. Contactability and Reluctance by Sexual Orientation and Combinations of Sexual Orientation, Gender, Race and Age for Sample Adults a,b.

Data Source: CDC/NCHS, National Health Interview Survey, 2013, 2014

aWeighted estimates

b Reported p-values based on Rao-Scott χ2 test

This differential reluctance pattern persisted when interacting sexual orientation with race and age. While non-Whites and those ages less than 50 years old showed a higher level of reluctance compared to their counterparts, non-straight SAs were consistently associated with a lower level of reluctance than straight SAs within each race group and within each age group. From Figure 1, it appeared that, overall, non-straight SAs were easier to contact and less reluctant than straight SAs, older non-straight SAs and non-straight White SAs being the least difficult groups. The association between these proxy nonresponse indicators and sexual orientation was examined controlling for well-known correlates of nonresponse in multinomial logistic regression in Table 2. We used the least difficult cases (high contactability and not reluctant) in the nonresponse indicator as a reference category. Hence, the odds ratios in Table 2 can be understood as indicating potential nonresponse.

Table 2.

Multinomial Logistic Regression Model of Combined Reluctance and Contactability (Reluctant & Low Contactability, Reluctant & High Contactability and Not Reluctant & Low Contactability Respectively Compared to Not Reluctant & High Contactability)a

| Dependent

Variable: Combined Reluctance and Contactability (Ref: Not Reluctant & High Contactability) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reluctant & Low Contactability | Reluctant & High Contactability | Not Reluctant & Low Contactability | ||||

| OR [95%CI] | OR [95%CI] | OR [95%CI] | ||||

| Predictor: Sexual orientation (Ref: Non-straight male) | ||||||

| Straight male | 1.50 | [1.06-2.12] | 1.36 | [1.06-1.74] | 1.31 | [0.90-1.92] |

| Straight female | 1.66 | [1.18-2.34] | 1.45 | [1.14-1.85] | 1.52 | [1.04-2.21] |

| Non-straight female | 1.68 | [1.08-2.59] | 1.30 | [0.95-1.79] | 1.11 | [0.68-1.81] |

| Control Variables | ||||||

| Age (Ref: 71 years old or older) | ||||||

| 18-30 years old | 1.84 | [1.55-2.19] | 0.87 | [0.78-0.96] | 2.74 | [2.15-3.49] |

| 31-40 years old | 1.94 | [1.65-2.27] | 1.02 | [0.92-1.14] | 2.72 | [2.10-3.53] |

| 41-50 years old | 2.03 | [1.72-2.39] | 1.12 | [1.01-1.24] | 2.53 | [1.97-3.24] |

| 51-60 years old | 1.67 | [1.43-1.94] | 1.04 | [0.94-1.15] | 2.14 | [1.65-2.78] |

| 61-70 years old | 1.23 | [1.03-1.46] | 1.03 | [0.95-1.12] | 1.36 | [1.06-1.76] |

| Race/ethnicity/interview language (Ref: Non-Hispanic White) | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 1.74 | [1.57-1.93] | 1.23 | [1.14-1.34] | 1.45 | [1.23-1.70] |

| Non-Hispanic Other | 1.43 | [1.23-1.65] | 1.31 | [1.18-1.45] | 1.25 | [1.04-1.51] |

| Hispanic Interviewed in English | 1.51 | [1.34-1.70] | 1.13 | [1.02-1.25] | 1.27 | [1.08-1.50] |

| Hispanic Interviewed in Spanish | 1.83 | [1.56-2.14] | 1.45 | [1.28-1.65] | 1.16 | [0.93-1.45] |

| Family structure (Ref: 1 adult without child) | ||||||

| 1 adult with child | 1.35 | [1.18-1.55] | 1.04 | [0.93-1.17] | 1.02 | [0.84-1.24] |

| 2+ adult with child | 1.32 | [1.19-1.47] | 1.14 | [1.06-1.23] | 0.88 | [0.79-0.88] |

| 2+ adult without child | 0.92 | [0.84-1.01] | 1.11 | [1.05-1.18] | 0.74 | [0.66-0.83] |

| Education: Some college vs. Less |

1.13 | [1.05-1.23] | 1.02 | [0.96-1.08] | 1.10 | [0.99-1.22] |

| Income: <200% vs. 200%+ FPL |

0.80 | [0.73-0.87] | 0.92 | [0.86-0.98] | 0.73 | [0.64-0.83] |

| Work status last week: Work vs. Not work |

1.46 | [1.35-1.57] | 1.10 | [1.04-1.16] | 1.66 | [1.47-1.86] |

| Home ownership: Own vs. Not own | 0.85 | [0.78-0.92] | 1.04 | [0.97-1.11] | 0.90 | [0.80-1.01] |

| Place of residence: Region (Ref: Northeast) | ||||||

| Midwest | 1.08 | [0.91-1.29] | 0.90 | [0.79-1.03] | 1.07 | [0.88-1.29] |

| South | 0.80 | [0.71-0.91] | 0.97 | [0.87-1.07] | 0.82 | [0.70-0.97] |

| West | 0.80 | [0.69-0.91] | 0.96 | [0.86-1.07] | 0.81 | [0.69-0.97] |

Data Source: CDC/NCHS, National Health Interview Survey, 2013, 2014

Weighted estimates

Sexual orientation was associated with nonresponse. Notably, when compared to non-straight male SAs, straight females showed significantly higher odds of being reluctant and/or difficult to contact with odds ratios ranging from 1.45 to 1.66. Odds ratios for being reluctant with low contactability as well as for being reluctant with high contactability were significantly higher for straight males, compared to non-straight males. Non-straight females were also significantly more likely to be reluctant and difficult to contact than non-straight males.

When examining control variables, younger SAs were associated with significantly higher reluctance and/or lower contactability than older SAs. All racial and ethnic minority groups showed significantly higher odds of any combinations of reluctance and low contactability. SAs with higher education or higher income, who worked last week or who did not own home were associated with higher nonresponse odds than their respective counterparts. SAs from families with child tended to have higher odds of reluctance and/or low contactability than those without. Compared to Northeast region, South and West regions were associated with lower nonresponse odds.

Sexual Orientation and Nonresponse Bias in Health Characteristics

We examined the estimates of health characteristics by nonresponse indicators and further by sexual orientation (see Appendix Table S2). Overall, 12.9% of SAs reported fair or poor health. The rate was 13.9% for those from the least difficult families and 11.9% for the rest, significantly different at P<0.001. The relative bias was 7.6%. This means that if NHIS had not made contact or persuasion efforts, the results would have overstated negative health. Similar observations can be made for chronic conditions and limitations. Overall, there were statistically significant differences, but the differences were small, ranging 0-2%. However, on doctor’s visit and ER stays, SAs from least difficult families were more likely to have visited 4 or more times and stayed at ER in the past 12 months than other SAs.

When examining nonresponse bias by respondents’ sexual orientation, different patterns emerged. Overall, non-straight males and females were associated with larger relative biases than their counterparts. On self-rated health, the relative bias was largest for non-straight males at 19.5%. On psychological distress, it was non-straight females with the largest relative bias at 6.1%. Non-straight females also showed a positive relative bias on obesity, a negative bias on physical activities and a very large positive bias on current smoking. Unlike other groups, non-straight males showed a negative relative bias on binge drinking. While relative biases were smaller for non-straights than straights on doctor’s visit, it was large for non-straight females on ER stay. Both non-straight males and females showed a large bias on not affording health care but in the opposite direction: positive for males and negative for females.

Discussion

The assumption about sexual minorities’ low participation rates did not hold in our analysis. In fact, straights were associated with higher nonresponse than non-straights. This pattern held true for both non-straight males and females. Straight females were the most difficult group in terms of contactability and reluctance. Perhaps, the stigma for the sexual minorities is not as high as it once was, and the survey contact history data used in this study reflected this change.

Had the contact and persuasion efforts been reduced, the results would have portrayed the population differently, and this difference would have been larger for non-straights than straights. Among non-straight males, nonrespondents were likely to report better health (higher self-rated health, lower chronic condition prevalence rates, and lower rates of limitations), be binge drinkers and have less issues with health care affordability than respondents. For non-straight females, nonresponse was associated with being less obese, more physically active and non-smokers and having more issues with affording health care than respondents.

In sum, nonresponse rates may be comparable between sexual minorities and non-minorities or lower for sexual minorities than non-minorities; however, potential nonresponse bias may be larger for sexual minorities than non-minorities. Although not explicitly elaborated, sexual minorities as a group experience unique health challenges: sleep problems, psychological distress, smoking, binge drinking and health care affordability, compared to the counterparts (see Appendix Table S2). Therefore, special considerations are required for surveying sexual minorities.

While this study offers new insights into the nonresponse mechanisms by introducing sexual orientation as a potential correlate, there are a number of limitations. First, we used those who required more intensive contact attempts and refusal conversion efforts used as a proxy for nonrespondents. These people were in fact respondents at the end. Although used in other studies (Curtin et al. 2000; Kreuter et al. 2010; Lee et al. 2009), the weakness of this approach is that it does not assess true nonresponse. In fact, some suggest its unclear utility (Groves 2006; Lin and Schaeffer 1995), a reason why we examined sexual orientation as a correlate, not a cause, of nonresponse. However, as shown in Table 1, while not perfect, the proxies differentiated true response patterns. Moreover, unless we start with a list of people whose sexual orientation is fully known, we cannot assess nonresponse with sexual orientation. To our knowledge, such data do not exist. Second, this study used publicly available paradata, which did not include detailed contact history, such as the time, mode and outcome of each contact attempt. Third, SAs were not necessarily the first person to whom contact attempts were made. To address this, we carried out a separate analysis with family respondents using their sexual orientation (obtained from SA data, if they were completed for adult interviews) and same-sex coupledness (obtained from family and person data, if not sampled for adult interview). Note that family respondents in the NHIS can be regarded as “gate keepers.” Essentially, results were the same as those reported in this study. Fourth, by nature, the analysis relied on self-reports of sexual orientation. If some sexual minority respondents masked their orientation and if a higher level of efforts was needed for them, then sexual minorities would be associated with higher nonresponse than what this study reported. However, low item nonresponse rates of the sexual orientation questions suggest this an unlikely case.

Despite the limitations, we believe replicating studies of this nature will benefit our understanding of sexual orientation as a correlate of nonresponse and associated nonresponse biases. Studies may consider expanding the scope of paradata so that detailed contact history as described above can be assessed by the sampled family characteristics (e.g., housing type), obtained through interviewer observations, the neighborhood characteristics linked to Census data as well as the characteristics of interviewers, for both respondents and nonrespondents alike. We expect these data, in conjunction with sexual orientation data, to provide rich context of how a family or person arrives at the decision on whether to participate in a survey and what factors, including sexual orientation, are related to such a decision.

Acknowledgement

This work was partially supported by a grant from the National Institute of Aging (grant number: R01AG026526-03A1,PI: Fredriksen-Goldsen). The funders played no role in the study design, analysis and interpretation of the data, writing the manuscript, or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Appendix

Table SI.

Characteristics of Sample Adults in 2013 and 2014 National Health Interview Survey§

| 2013 | 2014 | 2013 | 2014 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sexual orientation: | n=33,311 | n=35,509 |

Self-rated

health: Fair or poor |

n=34,444 | n=36,628 |

| Straight male | 43.4% | 43.5% | 15.3% | 14.6% | |

| Non-straight male | 1.3% | 1.2% |

Chronic

condition: ≥ 1 conditions |

n=34,452 | n=36,644 |

| Straight female | 54.1% | 53.8% | 51.4% | 52.7% | |

| Non-straight female | 1.3% | 1.5% |

Limited: Any way |

n=34,411 | n=36,577 |

| Age: | n=34,459 | n=36,651 | 37.3% | 37.3% | |

| 18-35 years old | 29.5% | 28.4% |

Sleep problem: Any last week |

n=33,373 | n=35,571 |

| 36-50 years old | 24.6% | 24.0% | 51.5% | 51.8% | |

| 51-65 years old | 25.3% | 25.7% |

Psychological distress: Moderate or high past 30 days |

n=33,184 | n=35,345 |

| 65 years old or older | 20.6% | 21.8% | 18.4% | 16.5% | |

| Race, ethnicity: | n=34,458 | n=36,651 | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 60.2% | 62.9% | Obese | n=33,292 | n=35,330 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 15.4% | 13.8% | 29.0% | 29.9% | |

| Non-Hispanic Other | 7.2% | 6.9% |

Physical

activity: Any moderate or vigorous activities last week |

n=34,229 | n=36.345 |

| Hispanics | 17.2% | 16.7% | 65.3% | 65.6% | |

| Family structure: | n=34,459 | n=36,651 | |||

| Without child, 1 Adult | 34.4% | 34.0% | |||

| Without child, >1 Adult | 34.8% | 35.9% |

Smoking

status: Current smoker |

n=34,349 | n=36,464 |

| With child | 30.9% | 30.6% | 18.1% | 17.5% | |

|

Education: Some college or more |

n=34,296 | n=36,488 |

Drinking: Binge past 12 months |

n=33,609 | n=35,730 |

| 58.6% | 59.0% | 21.7% | 23.9% | ||

|

Income: <200% Federal poverty level |

n=31,542 | n=34,723 |

Health

insurance: Currently insured |

n=34,340 | n=36,510 |

| 38.3% | 38.7% | 82.8% | 86.5% | ||

| n=34,443 | n=36,633 | n=33,918 | n=36,054 | ||

|

Work status: Worked

last week |

55.9% | 56.4% |

Doctor

visit: ≥ 4 times past 12 months |

23.9% | 23.0% |

| Region: | n=34,459 | n=36,651 | |||

| Northeast | 16.3% | 16.1% |

ER stay: Any past 12 months |

n=34,063 | n=36,176 |

| Midwest | 20.5% | 21.3% | 20.0% | 19.5% | |

| South | 37.1% | 35.2% |

Not afford care: Any past 12 months |

n=34,212 | n=36,310 |

| West | 26.1% | 27.4% | 19.7% | 17.9% |

Data Source: CDC/NCHS, National Health Interview Survey, 2013, 2014

Unweighted; Base sample sizes differ by item due to differential item nonresponse rates in the source data.

Table S2.

| A. Health Status | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health Characteristics | All Sample Adults | Sexual Orientation | |||||||||||||

| Straight Males | Non-Straight Males | Straight Females | Non-Straight Females |

||||||||||||

| n | % | SE | n | % | SE | n | % | SE | n | % | SE | n | % | SE | |

| Self-rated health: Fair or poor | |||||||||||||||

| Total | 68,656 | 12.9 | 0.2 | 29,831 | 12.3 | 0.3 | 855 | 12.3 | 1.1 | 37,026 | 13.4 | 0.3 | 944 | 14.7 | 1.3 |

| 1. Not reluctant & High contact | 35,479 | 13.9 | 0.3 | 15,591 | 13.4 | 0.4 | 489 | 14.8 | 1.5 | 18,881 | 14.2 | 0.3 | 518 | 15.2 | 1.8 |

| 2. Others | 33,177 | 11.9 | 0.2 | 14,240 | 11.2 | 0.3 | 366 | 8.8 | 1.3 | 18,145 | 12.5 | 0.3 | 426 | 14.2 | 1.8 |

| Relative bias (%) | 7.6 | 8.8 | 19.5 | 6.4 | 3.3 | ||||||||||

| Diff (1-2, percent point) | 2.0 (p<.001) | 2.2 (p<.001) | 6.0 (p=.021) | 1.7 (p<.001) | 1.0 (p=.755) | ||||||||||

| Chronic condition: 1 or more condition | |||||||||||||||

| Total | 68,679 | 48.9 | 0.3 | 29,835 | 47.2 | 0.4 | 855 | 47.6 | 1.7 | 37,043 | 50.8 | 0.4 | 946 | 44.3 | 1.8 |

| 1. Not reluctant & High contact | 35,488 | 51.7 | 0.4 | 15,590 | 50.3 | 0.6 | 489 | 51.0 | 2.4 | 18,889 | 53.3 | 0.6 | 520 | 45.1 | 2.8 |

| 2. Others | 33,191 | 46.1 | 0.4 | 14,245 | 44.0 | 0.6 | 366 | 42.5 | 3.2 | 18,154 | 48.3 | 0.5 | 426 | 43.4 | 2.4 |

| Relative bias (%) | 5.7 | 6.6 | 7.2 | 5.1 | 1.8 | ||||||||||

| Diff (1-2, percent point) | 5.6 (p<.001) | 6.3 (p<.001) | 8.4 (p=.049) | 5.1 (p<.001) | 1.7 (p=.653) | ||||||||||

| Limited: Any way | |||||||||||||||

| Total | 68,655 | 33.9 | 0.3 | 29,819 | 28.6 | 0.4 | 855 | 32.4 | 1.6 | 37,037 | 38.7 | 0.4 | 944 | 41.5 | 1.8 |

| 1. Not reluctant & High contact | 35,480 | 36.2 | 0.4 | 15,589 | 31.2 | 0.6 | 489 | 36.1 | 2.4 | 18,883 | 40.9 | 0.5 | 519 | 42.4 | 2.4 |

| 2. Others | 33,175 | 31.5 | 0.4 | 14,230 | 25.9 | 0.5 | 366 | 26.8 | 2.9 | 18,154 | 36.6 | 0.5 | 425 | 40.4 | 2.4 |

| Relative bias (%) | 6.9 | 9.2 | 11.6 | 5.6 | 2.3 | ||||||||||

| Diff (1-2, percent point) | 4.7 (p<.001) | 5.4 (p<.001) | 9.3 (p=.031) | 4.3 (p<.001) | 2.0 (p=.539) | ||||||||||

| Sleeping problem: Any last week | |||||||||||||||

| Total | 68,177 | 50.7 | 0.3 | 29,620 | 44.7 | 0.4 | 853 | 58.2 | 1.9 | 36,763 | 55.7 | 0.4 | 941 | 66.1 | 1.8 |

| 1. Not reluctant & High contact | 35,332 | 52.0 | 0.4 | 15,524 | 46.1 | 0.6 | 487 | 58.6 | 2.6 | 18,804 | 56.9 | 0.5 | 517 | 68.7 | 2.3 |

| 2. Others | 32,845 | 49.3 | 0.4 | 14,096 | 43.2 | 0.6 | 366 | 57.7 | 3.4 | 17,959 | 54.4 | 0.5 | 424 | 63.2 | 2.7 |

| Relative bias (%) | 2.6 | 3.3 | 0.7 | 2.3 | 3.9 | ||||||||||

| Diff (1-2, percent point) | 2.6 (p<.001) | 3.0 (p<.001) | 1.0 (p=.837) | 2.5 (p<.001) | 5.5 (p=.122) | ||||||||||

| Psychological distress: Moderate or high past 30 days | |||||||||||||||

| Total | 67,790 | 16.3 | 0.2 | 29,440 | 13.7 | 0.3 | 846 | 28.1 | 1.8 | 36,568 | 18.1 | 0.3 | 936 | 32.3 | 1.8 |

| 1. Not reluctant & High contact | 35,248 | 16.7 | 0.3 | 15,487 | 13.9 | 0.4 | 484 | 27.8 | 2.4 | 18,762 | 18.5 | 0.4 | 515 | 34.3 | 2.4 |

| 2. Others | 32,542 | 16.0 | 0.3 | 13,953 | 13.4 | 0.4 | 362 | 28.4 | 3.1 | 17,806 | 17.7 | 0.5 | 421 | 30.1 | 2.4 |

| Relative bias (%) | 2.1 | 1.9 | −0.9 | 2.2 | 6.1 | ||||||||||

| Diff (1-2, percent point) | 0.7 (p=.091) | 0.5 (p=.375) | −0.6 (p=. 883) | 0.8 (p=.176) | 4.2 (p=.194) | ||||||||||

| B. Health Risk and Risk Behaviors | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health Characteristics | All Sample Adults | Sexual Orientation | |||||||||||||

| Straight Males | Non-Straight Males | Straight Females | Non-Straight Females |

||||||||||||

| n | % | SE | n | % | SE | n | % | SE | n | % | SE | n | % | SE | |

| Obese | |||||||||||||||

| Total | 66,796 | 29.0 | 0.3 | 29,541 | 29.2 | 0.4 | 852 | 24.0 | 1.6 | 35,484 | 28.7 | 0.4 | 919 | 37.5 | 2.0 |

| 1. Not reluctant & High contact | 34,695 | 29.9 | 0.4 | 15,477 | 30.0 | 0.5 | 486 | 24.7 | 1.8 | 18,222 | 29.6 | 0.5 | 510 | 41.9 | 2.9 |

| 2. Others | 32,101 | 28.0 | 0.4 | 14,064 | 28.3 | 0.5 | 366 | 23.0 | 3.0 | 17,262 | 27.7 | 0.5 | 409 | 32.3 | 2.3 |

| Relative bias (%) | 3.2 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 3.3 | 11.9 | ||||||||||

| Diff (1-2, percent point) | 1.9 (p<.001) | 1.7 (p=.013) | 1.6 (p=.649) | 1.9 (p=.005) | 9.6 (p=.004) | ||||||||||

| Physical activities: Any moderate or vigorous activities any last week | |||||||||||||||

| Total | 68,466 | 67.0 | 0.4 | 29,713 | 68.7 | 0.5 | 854 | 76.5 | 1.8 | 36,959 | 65.1 | 0.4 | 940 | 73.5 | 1.8 |

| 1. Not reluctant & High contact | 35,397 | 65.9 | 0.5 | 15,535 | 67.3 | 0.6 | 489 | 76.7 | 2.0 | 18,856 | 64.1 | 0.6 | 517 | 69.1 | 2.7 |

| 2. Others | 33,069 | 68.2 | 0.4 | 14,178 | 70.1 | 0.6 | 365 | 76.2 | 2.8 | 18,103 | 66.1 | 0.6 | 423 | 78.6 | 2.0 |

| Relative bias (%) | −1.8 | −2.0 | 0.3 | −1.6 | −6.0 | ||||||||||

| Diff (1-2, percent point) | −2.4 (p<.001) | −2.8 (p<.001) | 0.6 (p=.853) | −2.1 (p=.008) | −9.5 (p=.002) | ||||||||||

| Smoking status: Current smoker | |||||||||||||||

| Total | 68,602 | 17.3 | 0.2 | 29,800 | 19.5 | 0.3 | 854 | 24.6 | 1.6 | 37,002 | 14.8 | 0.3 | 946 | 25.7 | 1.8 |

| 1. Not reluctant & High contact | 35,462 | 18.1 | 0.3 | 15,579 | 20.1 | 0.4 | 489 | 26.1 | 2.3 | 18,874 | 15.5 | 0.4 | 520 | 30.9 | 2.3 |

| 2. Others | 33,140 | 16.4 | 0.3 | 14,221 | 18.8 | 0.5 | 365 | 22.4 | 2.5 | 18,128 | 14.1 | 0.4 | 426 | 19.7 | 2.0 |

| Relative bias (%) | 4.7 | 3.4 | 6.0 | 4.8 | 20.5 | ||||||||||

| Diff (1-2, percent point) | 1.6 (p<.001) | 1.4 (p=.029) | 3.6 (p=.323) | 1.4 (p=.010) | 11.3 (p<.001) | ||||||||||

| Drinking: Binge past 12 months | |||||||||||||||

| Total | 67,448 | 24.0 | 0.3 | 29,128 | 31.5 | 0.5 | 839 | 39.3 | 2.0 | 36,550 | 16.5 | 0.3 | 931 | 30.6 | 1.8 |

| 1. Not reluctant & High contact | 35,025 | 24.0 | 0.4 | 15,323 | 31.0 | 0.6 | 484 | 36.2 | 2.4 | 18,706 | 16.8 | 0.4 | 512 | 32.3 | 2.5 |

| 2. Others | 32,423 | 24.0 | 0.4 | 13,805 | 32.1 | 0.6 | 355 | 43.9 | 3.7 | 17,844 | 16.3 | 0.4 | 419 | 28.8 | 2.6 |

| Relative bias (%) | 0.0 | −1.6 | −7.8 | 1.3 | 5.3 | ||||||||||

| Diff (1-2, percent point) | 0.0 (p=.974) | −1.1 (p=. 142) | −7.7 (p=.080) | 0.4 (p=.457) | 3.5 (p=.331) | ||||||||||

| C. Access to and Utilization of Health Care | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health Characteristics | All Sample Adults | Sexual Orientation | |||||||||||||

| Straight Males | Non-Straight Males | Straight Females | Non-Straight Females | ||||||||||||

| n | % | SE | n | % | SE | n | % | SE | n | % | SE | n | % | SE | |

| Health insurance: Currently insured | |||||||||||||||

| Total | 68,449 | 85.0 | 0.2 | 29,726 | 83.4 | 0.3 | 847 | 82.7 | 1.4 | 36,936 | 86.7 | 0.2 | 940 | 81.1 | 1.4 |

| 1. Not reluctant & High contact | 35,397 | 85.4 | 0.3 | 15,550 | 83.6 | 0.5 | 486 | 81.7 | 2.0 | 18,844 | 87.3 | 0.3 | 517 | 82.1 | 2.2 |

| 2. Others | 33,052 | 84.7 | 0.3 | 14,176 | 83.1 | 0.5 | 361 | 84.3 | 2.7 | 18,092 | 86.2 | 0.4 | 423 | 80.0 | 1.7 |

| Relative bias (%) | 0.4 | 0.3 | −1.3 | 0.7 | 1.2 | ||||||||||

| Diff (1-2, percent point) | 0.7 (p=.071) | 0.5 (p=.464) | −2.6 (p=.486) | 1.2 (p=.019) | 2.1 (p=.463) | ||||||||||

| Doctor visit: 4 times or more past 12 months | |||||||||||||||

| Total | 68,464 | 22.4 | 0.2 | 29,768 | 17.3 | 0.3 | 854 | 22.4 | 1.6 | 36,902 | 27.1 | 0.3 | 940 | 30.2 | 1.5 |

| 1. Not reluctant & High contact | 35,400 | 23.8 | 0.3 | 15,567 | 18.8 | 0.5 | 488 | 22.4 | 2.4 | 18,828 | 28.6 | 0.5 | 517 | 29.1 | 2.2 |

| 2. Others | 33,064 | 21.0 | 0.3 | 14,201 | 15.7 | 0.4 | 366 | 22.5 | 3.0 | 18,074 | 25.6 | 0.4 | 423 | 31.5 | 2.2 |

| Relative bias (%) | 6.3 | 8.9 | −0.2 | 5.6 | −3.7 | ||||||||||

| Diff (1-2, percent point) | 2.8 (p<.001) | 3.1 (p<.001) | −0.1 (p=. 981) | 3.0 (p<.001) | −2.4 (p=.445) | ||||||||||

| ER stay: Any past 12 months | |||||||||||||||

| Total | 68,635 | 18.6 | 0.2 | 29,816 | 16.6 | 0.3 | 854 | 19.4 | 1.5 | 37,022 | 20.3 | 0.3 | 943 | 27.0 | 1.5 |

| 1. Not reluctant & High contact | 35,462 | 19.4 | 0.3 | 15,579 | 17.4 | 0.4 | 488 | 19.8 | 1.9 | 18,876 | 21.0 | 0.4 | 519 | 29.7 | 2.5 |

| 2. Others | 33,173 | 17.9 | 0.3 | 14,237 | 15.8 | 0.4 | 366 | 19.0 | 2.4 | 18,146 | 19.6 | 0.4 | 424 | 24.1 | 2.1 |

| Relative bias (%) | 4.1 | 4.9 | 1.7 | 3.5 | 9.7 | ||||||||||

| Diff (1-2, percent point) | 1.5 (p<.001) | 1.7 (p=.005) | 0.8 (p=.798) | 1.4 (p=.026) | 5.6 (p=.117) | ||||||||||

| Not afford health care: Any past 12 months | |||||||||||||||

| Total | 68,683 | 17.5 | 0.3 | 29,837 | 14.5 | 0.3 | 854 | 24.1 | 1.7 | 37,047 | 19.9 | 0.4 | 945 | 30.5 | 1.7 |

| 1. Not reluctant & High contact | 35,485 | 17.2 | 0.3 | 15,588 | 14.1 | 0.4 | 488 | 27.9 | 2.5 | 18,889 | 19.5 | 0.4 | 520 | 27.7 | 2.2 |

| 2. Others | 33,198 | 17.9 | 0.4 | 14,249 | 14.9 | 0.4 | 366 | 18.5 | 2.2 | 18,158 | 20.3 | 0.5 | 425 | 33.6 | 2.8 |

| Relative bias (%) | −2.1 | −2.7 | 15.9 | −1.9 | −9.1 | ||||||||||

| Diff (1-2, percent point) | −0.8 (p=.115) | −0.8 (p=.189) | 9.4 (p=.005) | −0.8 (p=.228) | −5.9 (p=.104) | ||||||||||

Data Source: CDC/NCHS, National Health Interview Survey, 2013, 2014

Weighted estimates

Reported p-values for the difference based on Rao-Scott χ2 test

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest:

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. This work was partially supported by a grant from the National Institute of Aging (grant number: R01AG026526-03A1,PI: Fredriksen-Goldsen).

Financial Disclosures: None to declare.

References

- Catania Joseph A., Gibson David R., Chitwood Dale D., and Coates Thomas J.. 1990. “Methodological Problems in AIDS Behavioral Research: Influences on Measurement Error and Participation Bias in Studies of Sexual Behavior.” Psychological Bulletin 108(3):339–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2014. 2014 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS). Retrieved (http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/nhis_2014_data_release.htm Accessed March 1, 2016).

- Clift Joseph B. and Kirby James. 2012. “Health Care Access and Perceptions of Provider Care Among Individuals in Same-Sex Couples: Findings From the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS).” Journal of Homosexuality 59(6):839–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran Susan D. and Mays Vickie M.. 2000. “Relation between Psychiatric Syndromes and Behaviorally Defined Sexual Orientation in a Sample of the US Population.” American Journal of Epidemiology 151(5):516–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtin Richard, Presser Stanley, and Singer Eleanor. 2000. “The Effects of Response Rate Changes on the Index of Consumer Sentiment.” Public Opinion Quarterly 64(4):413–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtin Richard, Presser Stanley and Singer Eleanor. (2005). “Changes in Telephone Survey Nonresponse over the Past Quarter Century.” Public Opinion Quarterly, 69(1): 87–98. [Google Scholar]

- Dahlhamer James M., Galinsky Adena M., Joesti Sarah S., and Ward Brian W.. 2016. “Barriers to Health Care Among Adults Identifying as Sexual Minorities: A US National Study.” American Journal of Public Health 106(6):1116–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlhamer James M., Galinsky Adena M., Joesti Sarah S., and Ward Brian W.. 2014. Sexual Orientation in the 2013 National Health Interview Survey: A Quality Assessment. Retrieved (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_02/sr02_169.pdf). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davern M 2013. “Nonresponse Rates are a Problematic Indicator of Nonresponse Bias in Survey Research.” Health Services Research 48(3): 905–912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dilley Julia A., Simmons Katrina Wynkoop, Boysun Michael J. Pizacani Barbara A., and Stark Mike J.. 2010. “Demonstrating the Importance and Feasibility of Including Sexual Orientation in Public Health Surveys: Health Disparities in the Pacific Northwest.” American Journal of Public Health 100(3):460–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores Andrew R. 2015. “Examining Variation in Surveying Attitudes on Same-Sex Marriage: A Meta-Analysis.” Public Opinion Quarterly 79(2):580–93. [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen Karen I. and Kim Hyun-Jun. 2015. “Count Me in: Response to Sexual Orientation Measures among Older Adults.” Research on Aging 37(5):464–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen Karen I. et al. 2013. “Health Disparities among Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Older Adults: Results from a Population-Based Study.” American Journal of Public Health 103(10):1802–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groves Robert M. 2006. “Nonresponse Rates and Nonresponse Bias in Household Surveys.” Public Opinion Quarterly 70:646–75. [Google Scholar]

- Herold Edward S. and Way Leslie. 1998. “Sexual Self-Disclosure among University Women.” Journal of Sex Research 24(1):1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jans Matt et al. 2015. “Trends in Sexual Orientation Missing Data over a Decade of the California Health Interview Survey.” America Journal of Public Health 105(5):e43–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson Tim P. and Wislar Joseph. 2012. “Response Rates and Nonresponse Errors in Surveys.” JAMA 307(17): 1805–1806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeter Scott, Miller Carolyn, Kohut Andrew, Groves Robert M., and Presser Stanley. 2000. “Consequences of Reducing Nonresponse in a National Telephone Survey.” Public Opinion Quarterly 64(2):125–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler Ronald C. et al. 2002. “Short Screening Scales to Monitor Population Prevalences and Trends in Nonspecific Psychological Distress.” Psychological Medicine 32(6):959–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Hyun-Jun and Fredriksen-Goldsen Karen I.. 2012. “Hispanic Lesbians and Bisexual Women at Heightened Risk for [Corrected] Health Disparities.” America Journal of Public Health 102(1):e9–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreuter Frauke et al. 2010. “Using Proxy Measures and Other Correlates of Survey Outcomes to Adjust for Nonresponse: Examples from Multiple Surveys.” Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series A (Statistics in Society) 173(2):389–407. [Google Scholar]

- Kreuter Frauke, Couper Mick P., and Lyberg Lars E.. 2009. “The Use of Paradata to Monitor and Manage Survey Data Collection.” Pp. 282–96 in Proceedings of the Joint Statistical Meetings Alexandria, VA: American Statistical Association. [Google Scholar]

- Lee Sunghee, Brown E. Richard, Grant David, Belin Thomas R., and Brick J. Michael 2009. “Exploring Nonresponse Bias in a Health Survey Using Neighborhood Characteristics.” America Journal of Public Health 99(10):1811–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin I-Fen, and Schaeffer Nora Cate. 1995. “Using Survey Participants to Estimate the Impact of Nonparticipation.” Public Opinion Quarterly 59:236–58 [Google Scholar]

- Magnani Robert, Sabin Keith, Saidel Tobi, and Heckathorn Douglas D.. 2005. “Review of Sampling Hard-to-Reach and Hidden Populations for HIV Surveillance.” AIDS 19(2):S67–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer Ilan H., and Wilson Patrick A.. 2009. “Sampling Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Populations.” Journal of Counseling Psychology 56(1):23–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Health Statistics. 2014. A Brief Quality Assessment of the NHIS Sexual Orientation Data. Retrieved (http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhis/qualityso2013508.pdf Accessed March 1, 2016).

- National Center for Health Statistics. 2015. Paradata File Description, National Health Interview Survey, 2014. Retrieved (ftp://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/Health_Statistics/NCHS/Dataset_Documentation/NHIS/2014/srvydesc_paradata.pdf Accessed March 1, 2016).

- Pew Research Center. 2016. Changing Attitudes on Gay Marriage. Retrieved (http://www.pewforum.org/2016/05/12/changing-attitudes-on-gay-marriage/ (accessed May 17, 2017))

- Peytchev Andy, Peytcheva Emilia, and Groves Robert M.. 2010. “Measurement Error, Unit Nonresponse, and Self-Reports of Abortion Experiences.” Public Opinion Quarterly 74(2):319–27. [Google Scholar]

- Raboud Janet et al. 2013. “Representativeness of an HIV Cohort of the Sites from Which It Is Recruiting: Results from the Ontario HIV Treatment Network (OHTN) Cohort Study.” BMC Medical Research Methodology 13(31). Retrieved (http://bmcmedresmethodol.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2288-13-31). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sell Randall L., and Holliday Michelle L.. “Sexual Orientation Data Collection Policy in the United States: Public Health Malpractice.” 104(6): 967–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tourangeau Roger. 2014. “Defining Hard-to-Survey Populations” Pp. 3–20 in Hard-to-survey Populations, edited by Tourangeau R, Edwards B, Johnson TP, Wolter KM, and Bates N. Cambridge, England: University Press. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Federal Committee on Statistical Methodology (2001). Measuring and Reporting Sources of Errors in Surveys. Washington D.C.: Office of Management and Budget; (Statistical Policy Working Paper 31). Retrieved from https://s3.amazonaws.com/sitesusa/wp-content/uploads/sites/242/2014/04/spwp31.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Whitman Jonathan R. B. and Halbesleben Marilyn V. (2013). “Evaluating Survey Quality in Health Services Research: A Decision Framework for Assessing Nonresponse Bias.” Health Research and Educational Trust 48(3): 913–930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]