The authors developed a method for analyzing single cells under various conditions by tagging cells with small fragments of DNA.

Abstract

The development of high-throughput single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has enabled access to information about gene expression in individual cells and insights into new biological areas. Although the interest in scRNA-seq has rapidly grown in recent years, the existing methods are plagued by many challenges when performing scRNA-seq on multiple samples. To simultaneously analyze multiple samples with scRNA-seq, we developed a universal sample barcoding method through transient transfection with short barcode oligonucleotides. By conducting a species-mixing experiment, we have validated the accuracy of our method and confirmed the ability to identify multiplets and negatives. Samples from a 48-plex drug treatment experiment were pooled and analyzed by a single run of Drop-Seq. This revealed unique transcriptome responses for each drug and target-specific gene expression signatures at the single-cell level. Our cost-effective method is widely applicable for the single-cell profiling of multiple experimental conditions, enabling the widespread adoption of scRNA-seq for various applications.

INTRODUCTION

Unlike conventional bulk measurements, single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) permits analysis of the transcriptomes of individual cells (1–3), and this has shed light on the variations in cell populations, such as tumor heterogeneity. Platforms such as Drop-Seq (4), inDrop (5), and 10X Genomics Chromium (6) provide high-throughput single-cell information over thousands of cells. While the number of cells able to be profiled has increased and per-cell cost has dropped, challenges in scRNA-seq still include high sample preparation cost, ambiguous identification of true single cells, and sample-dependent batch effects (7), limiting the widespread adoption and scope of scRNA-seq. For experiments requiring the analysis of multiple single-cell samples (i.e., numerous samples of various conditions or samples from many patients), a separate scRNA-seq run must be conducted for each sample. Without the use of multiplexing, performing scRNA-seq for multiple samples is labor intensive and is limited by the high sample preparation cost rather than the per-cell cost in sequencing. Therefore, the demand for multiplexing samples in scRNA-seq is continuously increasing, requiring methods in which samples are pooled and subjected to a single scRNA-seq run.

To deal with the challenges stated above, a method has recently been developed for multiplexing samples from diverse patients by their endogenous genetic barcodes (8). In this approach, single-nucleotide polymorphisms in each patient serve as a sample barcode for determining the sample identity of each cell, enabling multiple samples to be pooled and sequenced simultaneously. While this approach can partially deal with multiplexing problems, applicable samples are limited to those that are genetically distinct. Still, multiplexing between samples genetically identical but in diverse conditions remains a challenge, necessitating a universal approach for barcoding and multiplexing samples regardless of the sample identities.

During drug discovery, gene expression profiling can be applied to annotate the function of small molecules (9) and to elucidate the mechanisms underlying a biological pathway (10, 11). While systematic approaches to profile gene expression for a large number of small molecules using microarray technology have been conducted (12, 13), they are limited to bulk measurements. To capture diverse responses of highly heterogeneous samples such as tumor cells, single-cell gene expression profiling is indispensable, although current technologies are not suitable for multiple screening. We envisioned that development of multiplexed scRNA-seq can provide simultaneous expression profiling of various drug perturbations in a very efficient manner.

Here, we designed a multiplexed scRNA-seq method that involved transient transfection of short barcoding oligos (SBOs) to label samples from various experimental conditions. We demonstrated that this method relying on simple transfection can be used for simultaneous single-cell transcriptome profiling for multiple drugs.

RESULTS

Design for transient barcoding method

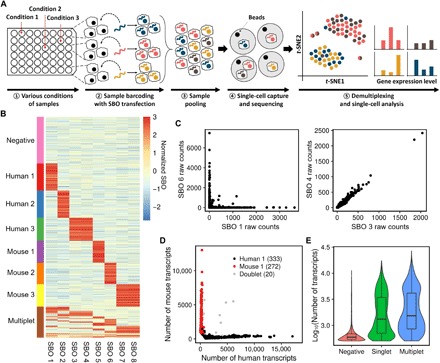

SBO, a single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides, consists of a sample barcode and a poly-A sequence (fig. S1A). Transient transfection of SBO allows a sample to be labeled with a unique barcode. The barcoded samples of various conditions are pooled and simultaneously processed for scRNA-seq (Fig. 1A). The poly-A sequence in the SBOs ensures that the mRNAs and SBOs are captured and reverse-transcribed together during the scRNA-seq process (fig. S1B). Computational analysis of digital count matrices of SBOs allows us to demultiplex and determine sample origins. This universal barcoding method, based on simple transfection, enabled sample multiplexing, identified multiplets and negatives, and reduced the preparation cost per sample.

Fig. 1. Scheme and validation of transient barcoding method.

(A) Scheme of multiplexed scRNA-seq by transient barcoding method using SBOs. (1) Samples with various conditions are prepared. (2) Each sample is transfected with SBO containing a unique sample barcode. (3) Barcoded cells are pooled together and processed for scRNA-seq (e.g., Drop-Seq). (4) Cells are lysed within droplets, and the released mRNAs and SBOs are captured, reverse-transcribed, and sequenced. (5) Cells are demultiplexed and assigned to their origins and processed for further analysis. (B) Heatmap of normalized SBO counts for 6-plex human/mouse species-mixing experiment. Rows represent cells, and columns represent SBOs. Cells are assessed whether they are positive for a particular SBO based on the SBO count matrix (see Materials and Methods). Cells were classified as singlets (positive for a unique SBO), multiplets (positive for more than one SBO), or negatives (not positive for any SBO) and ordered by their classifications. (C) Scatter plot showing raw counts between two SBOs. SBOs 1 and 6 were used to barcode different samples (Human 1, Mouse 2) (left). SBOs 3 and 4 were used to barcode the same sample (Human 3) (right). (D) Species-mixing plot of samples associated with SBOs 1 and 5. Cells were labeled according to their SBO classifications. Black dots indicate Human 1 sample barcoded with SBO 1, red dots indicate Mouse 1 sample barcoded with SBO 5, and gray dots indicate doublets that are positive for both SBOs. (E) Distribution of RNA transcript counts in cells between singlets (green), multiplets (blue), and negatives (red). Negatives, which imply beads exposed to ambient RNA, had the lowest number of transcripts. Multiplets had slightly more transcripts than singlets, indicating more RNA content within a droplet.

Validation of ability and accuracy for transient barcoding method

To demonstrate our method’s ability and accuracy of multiplexing samples, we performed a 6-plex human/mouse species-mixing experiment. Two samples each of HEK293T and NIH3T3 cells carried a single unique SBO, and one sample of each cell line carried a combination of the two SBOs (fig. S1C). We pooled all the samples together in equal proportions and performed a single run of Drop-Seq. Cells were deliberately overloaded during Drop-Seq to increase the chance of multiplets. We obtained 2759 cell barcodes, in which at least 500 transcripts were detected, and the cells were successfully assigned to their sample origins. Multiplets and negative cells were detected on the basis of the SBO count matrix (see Materials and Methods). Cells that were classified as singlets almost exclusively express their sample barcodes, while multiplets and negatives express multiple or no sample barcode, respectively (Fig. 1B). Scatter plots of SBO counts that originated from two different samples showed an exclusive relationship, whereas SBO counts from the same sample showed a strong correlation in their expressions (Fig. 1C and fig. S2A). Species classification using SBOs was consistent with the transcriptome-based species-mixing plot results (Fig. 1D and fig. S2, B and C). We also observed a clear difference in the distribution of RNA transcripts between singlets, multiplets, and negatives as expected, indicating the unambiguous detection of multiplets and negatives (Fig. 1E). These results suggested that our method enabled sample multiplexing in single-cell experiments with high accuracy and specificity, and elimination of multiplets and negatives. We also verified that the SBO barcoding approach could be applied to model heterogeneous samples without cell type–specific bias (fig. S3, A to E). Our data also demonstrate that transient transfection did not affect the gene expression profiles (fig. S3, F and G).

Time-resolved expression profiles in drug perturbations

We envisioned that our method could be used when interested in screening multiple gene expression profiles in single cells subjected to drug perturbations. We performed a 5-plex time-course scRNA-seq in the K562 cell line, which is derived from chronic myeloid leukemia and expresses the Bcr-Abl fusion gene (14). Applying our multiplexing strategy, we investigated the single-cell transcriptional response of K562 cells to imatinib, a BCR–ABL–targeting drug (15), over treatment time (see Materials and Methods). Unlike conventional scRNA-seq, by regressing out technical batch effects, multiplexed scRNA-seq applied here enables the detection of subtle transcriptional changes in the integrated analysis of multiple samples, facilitating more precise analysis. Following the drug treatments, samples were pooled, sequenced, and demultiplexed. After removing doublets and negatives, single cells were subjected to downstream analysis.

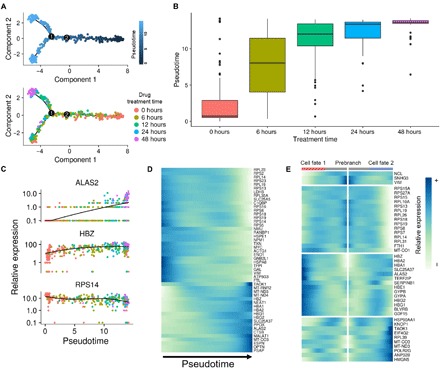

Pseudotime analysis of single cells in multiplexed samples collected from five time points showed a branched gene expression trajectory and a sequential progression in trajectory over drug treatment time (Fig. 2A). The branched trajectory showed that two transition states existed as a result of imatinib treatment. Samples exhibited asynchronous patterns in pseudotime, although the average increased with drug treatment time (Fig. 2B). We noted that even in the zero-time sample, cells were highly heterogeneous in terms of pseudotime. In addition, we observed an accumulation on the upper transition state as the drug treatment time increased. Differential expression analysis over pseudotime identified several gene cohorts that change during the transition (Fig. 2, C and D). Notably, the expression levels of erythroid-related genes such as HBZ and ALAS2 had increased over pseudotime (Fig. 2C). This was consistent with previous studies that have shown increased expression of HBZ in imatinib-treated cells (16, 17). Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between the two transition states were also identified, and different expression patterns between them were observed (Fig. 2E).

Fig. 2. Pseudotime analysis in 5-plex time-course experiment.

(A) Monocle pseudotime trajectory of K562 cells treated with imatinib at different time points. Cells are labeled by pseudotime (top) and drug treatment time (bottom). The 0-, 6-, 12-, 24-, and 48-hour samples consist of 133, 109, 79, 49, 58, 52, and 90 cells, respectively. (B) Boxplot showing the distribution of pseudotime within each sample. (C) Prominent gene expression alterations in 5-plex time-course experiments of imatinib treatment. Note that the cells are labeled by drug treatment time and are not synchronously distributed over pseudotime. (D) Expression heatmap showing 50 genes with the lowest q values. (E) Expression heatmap showing DEGs between two transition states with q < 1 ×10−4. Prebranch refers to the cells before branch 1, Cell fate 1 refers to the cells of upper transition state, and Cell fate 2 refers to the cells in the lower transition state.

Simultaneous expression profiling of K562 subjected to various drug perturbations

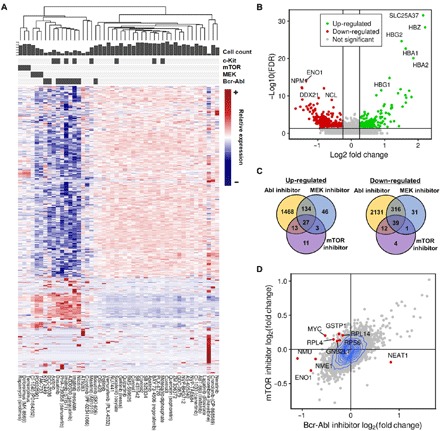

Next, we assessed whether our approach could be used for simultaneous single-cell transcriptome profiling for multiple drugs in K562 cells. We selected 45 drugs, of which most were kinase inhibitors, including several BCR-ABL–targeting drugs. Three dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) samples were used as controls (table S1). A 48-plex single-cell experiment was performed by barcoding and pooling all samples after drug treatments. A total of 3091 cells were obtained and demultiplexed after eliminating multiplets and negatives. The averaged expression profiles of each drug were visualized as a heatmap (Fig. 3A). Each drug exhibited its own expression pattern of responsive genes. Unsupervised hierarchical clustering of the averaged expression data for each drug revealed that the response-inducing drugs clustered together by their protein targets, whereas drugs that induced no response showed similar expression patterns with DMSO controls, indicating our method’s ability to identify drug targets by expression profiles (Fig. 3A and fig. S4). In addition, we could evaluate cell toxicity by examining the cell counts of each drug. Drugs that targeted BCR-ABL or ABL showed the strongest response and toxicity, and drugs that targeted MAPK kinase (MEK) or mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) showed relatively mild response. Differential expression analysis based on the single-cell gene expression data identified DEGs for each drug (Fig. 3B and fig. S5). We note that highly expressed erythroid-related genes such as HBZ, HBA, and HBG were up-regulated, and genes such as DDX21, NCL, ENO1, and NPM1 were down-regulated in the sample treated with imatinib (Fig. 3B). Similar DEGs were identified for other drugs targeting BCR-ABL. Drugs such as vinorelbine and neratinib showed unique gene expression signatures and DEGs. We next grouped the drugs by their protein targets and performed differential expression analysis. The analysis showed different relationships between DEGs of each protein target (Fig. 3C). In addition, comparative analysis between mTOR inhibitors and BCR-ABL inhibitors revealed that ribosomal protein-coding genes including RPL4, RPS2, and RPS3 and regulatory genes such as MYC and GSTP1 are up-regulated in the mTOR inhibitor group (Fig. 3D).

Fig. 3. Gene expression analysis in 48-plex drug treatment experiments.

(A) Hierarchical clustered heatmap of averaged gene expression profiles for 48-plex drug treatment experiments in K562 cells. Each column represents averaged data in a drug, and each row represents a gene. DEGs were used in this heatmap. The scale bar of relative expression is on the right side. The ability of the drugs to inhibit kinase proteins is shown as binary colors (dark gray indicating positive) at the top. The bar plot at the top shows the cell count for each. (B) Volcano plot displaying DEGs of imatinib mesylate compared with DMSO controls. Genes that have a P value smaller than 0.05 and an absolute value of log (fold change) larger than 0.25 are considered significant. Up-regulated genes are colored in green, down-regulated genes are colored in red, and insignificant genes are colored in gray. Ten genes with the lowest P value are labeled. (C) Venn diagram showing the relationship between DEGs of three drug groups. Fourteen drugs are classified into three groups according to their protein targets (see Fig. 2C, top), and differential expression analysis is performed by comparing each group with DMSO controls. Relations of both positively (left) and negatively (right) regulated genes in each group are shown. (D) Plot showing a correlation between fold changes of expression in cells treated with mTOR inhibitors and BCR-ABL inhibitors compared with DMSO controls.

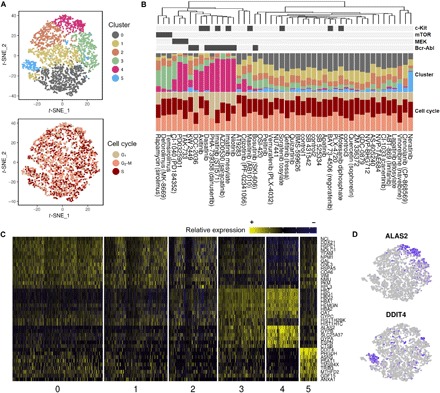

To comprehensively analyze the drug screening data at a single-cell resolution, we performed unsupervised clustering analysis on all the single-cell datasets. We observed six clusters (Fig. 4A), which were not clearly separated possibly due to a highly complex transcriptional space. Nevertheless, for each drug, the relative abundance of cells assigned to each cluster was various (Fig. 4B and fig. S6). Most of the cells affected by BCR-ABL and MEK inhibitors were concentrated in cluster 4, whereas cells affected by mTOR inhibitors were mainly concentrated in cluster 3. Especially, most of the cells in cluster 5 belong to the neratinib-treated sample. Several markers associated with each cluster were verified by differential expression analysis (Fig. 4, C and D). Analysis of cell cycle states revealed no association between cell cycle states and specific clusters (Fig. 4A). The fraction of highly proliferative state (G2 phase) was decreased in samples treated with BCR-ABL–targeting drugs possibly due to drug-induced cell cycle arrest (Fig. 4B) (18).

Fig. 4. Single-cell analysis in 48-plex drug treatment experiments.

(A) The t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) plot of single cells in the 48-plex K562 samples. Plot shows six clusters (top), and additional t-SNE plot is labeled by cell cycle states (bottom). (B) Bar plots for 48-plex drug treatment experiments in K562 cells. The ability of the drugs to inhibit kinase proteins is shown as binary colors at the top (from Fig. 3A). The bar plot in the middle represents a relative fraction of cells in each t-SNE cluster [shown in (A)], and the bottom bar plot displays fractions of cell cycle states for every sample. Drugs are sorted by hierarchical clustering. (C) Expression heatmap showing the markers of the clusters. The numbers at the bottom represent cluster numbers. (D) Scaled expression of representative genes within the t-SNE plot. Intensity of the purple color determines expression levels, with higher intensity correlating with higher gene expression.

To validate the universal applicability of our methods, we performed a 48-plex drug screening experiment on the A375 cell line [BRAF V600E positive (19)] with an identical drug set. Similar to K562 cells, response-inducing drugs were clustered together in a target-specific manner in A375 cells (fig. S7). Our results showed that multiplexed scRNA-seq could be used to screen single-cell transcriptional responses to drugs in a high-throughput manner and drug targets could be estimated by their transcriptional patterns.

DISCUSSION

We have developed a novel method for multiplexing samples in scRNA-seq, in which samples were transiently transfected through SBOs containing their own barcodes, pooled, and simultaneously sequenced. This method offers several advantages over currently available scRNA-seq. Our barcoding approach has several advantages in terms of time and cost compared to running multiple individual scRNA-seq experiments. Except for the next-generation sequencing (NGS) cost, we believe that cost constraints occur in the scRNA-seq procedures and NGS preparation steps for each sample. For each sample, the cost of one Drop-Seq run and the corresponding NGS preparation process is approximately $160. In comparison, our SBO transfection method costs approximately $5 (e.g., oligos, transfection reagents, and SBO NGS preparation costs) for each additional sample. If multiple scRNA-seqs are individually processed, then each additional sample could consume an additional cost more than 30 times the barcoding approach of scRNA-seq with multiple samples. This cost saving in library preparation becomes substantial as the size of samples increases. In addition, “batch effect” is one of the major challenges in scRNA-seq (7). These technical noises can be critical and obscure true signals in integrated analysis for multiple samples from different preparations. By pooling and running all samples together, batch effects can be substantially reduced, enabling more precise analysis between single-cell samples.

We demonstrated that our method could also eliminate multiplets and negatives based on SBO count matrix, enabling filtering of true single cells. Identifying expression profiles of true single cells improves data quality and is advantageous for downstream single-cell analysis. In addition, the ability to eliminate multiplets and negatives has potential to increase throughput of scRNA-seq by using a high concentration of cells as an input and filtering single cells subjected to downstream analysis. Throughput of scRNA-seq can be increased beyond the experimental limit by the multiplexed RNA-seq.

Recently, a method for multiplexing samples using genetically natural barcodes has been developed (8). Genetically diverse samples are required in multiplexing by the demuxlet algorithm. Our method offers several advantages over the previous published methods for scRNA-seq (fig. S8). Particularly, our method is capable of multiplexing samples genetically identical but in different experimental conditions, whereas the method using the demuxlet algorithm is not capable of doing. More recently, a method for sample multiplexing using an antibody tagging has been reported (20). However, the method requires expensive reagents and surface markers, limiting the number of samples that can be practically applied.

Our method presented here is very simple and readily applicable to individual laboratories because of the easily accessible reagents and simple experimental process. In addition, because our method is based on liposomal transfection, it has a potential to be applied to nucleus samples. In addition, by using different combinations of SBOs, our method offers a high capacity for multiplexing. We expect that our multiplexing strategy will widely contribute to the adoption of scRNA-seq.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines and cell culture

All cell lines were obtained from the Korean Cell Line Bank (KCLB) and maintained at 37°C with 5% CO2. The human embryonic kidney HEK293T, the mouse embryo fibroblast NIH3T3, and the human malignant melanoma A375 cell lines were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Gibco, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco, USA) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). The human chronic myelogenous leukemia K562 cell line and the human colorectal adenocarcinoma SW480 cell line were cultured in RPMI 1640 (Gibco, USA) supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin.

Barcode design and transfection

The SBO contains a unique 8–base pair (bp) sample barcode, an amplification handle, and a poly-A tail. 5′-TCCAAGGTACAGACCTCTGACGNNNNNNNN(A)30-3′ is the full SBO sequence. “TCCAAGGTACAGACCTATATCTGACG” is the amplification handle sequence, “NNNNNNNN” is the sample barcode sequence, and (A)30 is the poly-A tail sequence. All SBOs were prepared by IDT (Integrated DNA Technologies, USA) without any modifications. Four hours before Drop-Seq, SBO (28 pmol/ml) was transfected per well using Lipofectamine 3000 (Life Technologies, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Drop-Seq: NGS preparation of mRNA and SBOs

For each experiment, samples of various conditions were pooled together. The pooled cells were passed through a 40-μm filter and diluted at a final combined concentration of 100 to 400 cells/μl according to Drop-Seq protocol instructions (4). Droplets were generated and processed as previously described. Droplets were collected, and the recovered beads were processed for immediate reverse transcription, followed by exonuclease I treatment. The resulting complementary DNA (cDNA) was divided into appropriate number of tubes, amplified using the KAPA HiFi HotStart PCR Kit (Kapa Biosystems Inc., Switzerland). cDNA amplification was performed in 50 μl of polymerase chain reaction (PCR), which included 4 μl of 10 μM SMART PCR primer, 25 μl of KAPA HiFi DNA polymerase, and up to 21 μl of nuclease-free water. Then, PCR was performed using the following protocol: 3 min at 95°C; four cycles of 20 s at 98°C, 45 s at 65°C, 3 min at 72°C; nine cycles of 20 s at 98°C, 20 s at 67°C, 3 min s at 72°C; 5 min at 72°C. The PCR products were purified twice using 0.6× AMPure (Beckman Coulter, USA) beads according to the manufacturer’s instructions. To obtain reverse-transcribed SBOs that are much shorter than cDNA, the first supernatant from AMPure purification step was further purified adding 1.4× homemade AMPure beads [using Sera-Mag SpeedBeads (Thermo Scientific, USA), hereafter Serapure beads (21)]. The cDNA products were fragmented and further amplified using the Nextera XT DNA Library Preparation Kit (Illumina, USA).

The SBO library preparation was performed using a two-step PCR protocol. One nanogram of the SBO cDNA product was loaded into 20 μl of the first adaptor PCR, which included 1 μl of 10 μM forward and reverse primers, 10 μl of KAPA HiFi DNA polymerase, and up to 8 μl of nuclease-free water. PCR was performed using the following protocol: 3 min at 95°C; eight cycles of 20 s at 95°C, 20 s at 64°C, 20 s at 72°C; 5 min at 72°C using the following primers: SMART+AC; P7-SBO hybrid. After 1.8× Serapure bead purification, 8 μl of the first PCR product was loaded into 20 μl of the second index PCR, which included 1 μl of 10 μM forward and reverse primers, and 10 μl of KAPA HiFi DNA polymerase. PCR was performed using the following protocol: 3 min at 95°C; six cycles of 20 s at 95°C, 20 s at 60°C, 20 s at 72°C; 5 min at 72°C using the following primers: New-P5-SMART PCR hybrid; Nextera index oligo. The second PCR product was purified using 1.2× Serapure beads. All primers were prepared by IDT. Sequencing was performed on an Illumina NextSeq 500 system using a NextSeq 500/550 High Output v2 kit (75 cycles) (Illumina, USA). The sequences of primers were provided in table S1. The sequencing depth and number of cells of each experiment are provided in fig. S9.

6-Plex human/mouse species-mixing experiment

HEK293T and NIH3T3 cells were prepared 1 day before Drop-Seq and plated on six-well plates (Techno Plastic Products, Switzerland) at approximately 70% confluency. Transfection of SBO (28 pmol/ml) was performed 4 hours before Drop-Seq, as described above. All cell samples were trypsinized using trypsin-EDTA (0.25%) and phenol red (Gibco, USA), pooled together, and washed four times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Gibco, USA). The cells were then resuspended in 0.01% bovine serum albumin (BSA) + PBS, passed through a 40-μm filter, counted using the LUNA Automated Cell Counter (Logos Biosystems, Korea), and diluted at a final combined concentration of 400 cells/μl. The diluted sample library was run once in Drop-Seq, and sample preparation and sequencing were performed as above. From one Drop-Seq run, about 77,000 beads were obtained and divided into 24 PCRs for cDNA amplification. Sample preparation was completed using two reactions of the Nextera XT DNA Library Preparation Kit (Illumina, USA).

SBO transfection efficiency and its effect on mixed cultures

To mimic heterogeneous samples, cell lines with different transfection efficiencies were mixed and then SBOs were transfected into the mixed cell line cultures to observe the transfection efficiency and effect on the gene expression profile. HEK293T, NIH3T3, A375, and SW480 cell lines were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. All cell lines were prepared 1 day before SBO transfection and plated into six-well plates at approximately 70% confluency with the same number of cells for each cell line. All subsequent steps were the same as described above in the 6-plex human/mouse species-mixing experiment. After the Drop-Seq run, the pooled beads were divided into 24 PCRs for cDNA amplification. Sample preparation was completed using three reactions of the Nextera XT DNA Library Preparation Kit.

We performed the same experiment to examine the effect of SBO transfection on the gene expression profile of K562 cells at the bulk level. These cells were cultured in six-well plates at approximately 30% confluency. After 4 hours of SBO transfection, total RNA of control and transfected K562 cells was extracted using an RNA extraction kit (RNeasy Mini Kit, Qiagen, USA). Total RNA (2 μg) of control and transfected K562 cells was used for cDNA synthesis. Then, sample preparation was completed using the Nextera XT DNA Library Preparation Kit.

5-Plex time-course experiment of drug treatment

K562 cells were plated on six-well plates at approximately 30% confluency. Imatinib (1 μM) was treated to K562 for five time points (0, 6, 12, 24, and 48 hours after treatment). Transfection of SBO (28 pmol/ml) was performed 4 hours before Drop-Seq, as described above, and the cells of each condition were pooled, washed four times with PBS, and resuspended with 0.01% BSA + PBS. After filtering and counting, the pooled cells were diluted at a final combined concentration of 100 cells/μl. The diluted sample library was run once in Drop-Seq. Sample preparation and sequencing were performed as above. From one Drop-Seq run, the pooled beads were divided into 24 PCRs for cDNA amplification. Sample preparation was completed using two reactions of the Nextera XT DNA Library Preparation Kit.

48-Plex drug screening experiment in K562 cells

K562 cells were plated on 24-well plates at approximately 30% confluency and treated with 1 μM of each drug. After 44 hours, transfection of SBO (28 pmol/ml) was performed. Four hours after the transfection, the cell samples from each drug treatment were pooled. The diluted sample library was run three times in Drop-Seq. All subsequent steps were the same as described above in the 5-plex time-course experiment. After three Drop-Seq runs, the pooled beads were divided into 48 PCRs for cDNA amplification. Sample preparation was completed using three reactions of the Nextera XT DNA Library Preparation Kit.

48-Plex drug screening experiment in A375 cells

A375 cells were prepared 1 day before drug screening and plated on 24-well plates at approximately 30% confluency. All subsequent steps were the same as described above in the 48-plex drug treatment experiment. After three Drop-Seq runs, the pooled beads were divided into 48 PCRs for cDNA amplification. Sample preparation was completed using three reactions of the Nextera XT DNA Library Preparation Kit.

Single-cell transcriptome data processing

For each NextSeq sequencing run, raw sequencing data were converted to FASTQ files using bcl2fastq2 software (Illumina). Each sequencing sample was demultiplexed using Nextera N7xx indices. Tagging, trimming, alignment, and adding annotation tags were performed according to the standard Drop-Seq pipeline (http://mccarrolllab.org/dropseq/). Briefly, reads were first tagged according to the 12-bp cell barcode sequence and the 8-bp unique molecular identifier (UMI) in “read 1.” Then, reads in “read 2” were aligned with the hg19 or hg19-mm10 concatenated reference depending on the experiments and collapsed onto 12-bp cell barcodes that corresponded to individual beads. A Hamming distance of 1 was used to collapse UMI within each transcript. Digital expression matrix was obtained by collapsing filtered and mapped reads for each gene by UMI sequence within each cell barcode.

Sample barcode (SBOs) processing

FASTQ files of SBOs were generated as described above. Raw sequencing reads were trimmed to remove PCR handles. Cell barcodes and UMIs were extracted from read 1, and sample barcodes were extracted from read 2. Reads were assigned to 8-mer of sample barcode reference (table S1) with a single-base error tolerance (Hamming distance = 1), and cell barcodes × sample barcodes count matrix (hereinafter referred to as SBO matrix) was generated with consideration to UMI de-duplication. All the processes were made by our homemade python scripts.

Merging sample barcode and transcriptome data

Independently obtained cell barcodes from the two matrices (SBO matrix and transcriptome matrix) were compared and merged on the basis of the cell barcodes from the transcriptome matrix. When merging, a Hamming distance of 1 was allowed. Last, the columns of the SBO and the transcriptome matrix consisted of the same cell barcodes.

Demultiplexing and classification of samples using SBO matrix

SBO matrix was normalized using a modified version of centered log ratio (CLR) transformation (22)

xi′ denotes the normalized count for a specific SBO in cell i, xi denotes the raw count, and D is the total cell number. In CLR transformation, the raw counts of SBO are divided by the geometric mean of individual SBO across cells and are log-transformed. We added the raw counts of SBO to 1 to avoid infinite values. We hypothesized that we can discriminate positive signals from negative (background) signals by fitting the distribution of negative signals of each SBO and thresholding the normalized counts to a specific value of each SBO. Following the normalization, for each SBO, we excluded the cells with the highest expression of the SBO among all SBOs. We fitted a negative binomial distribution to the remaining cells to obtain a distribution of negative signals. Next, we calculated a quantile with 0.99 probability to get the threshold value of each SBO. Cells that have higher SBO counts than the threshold value were considered as positives for that SBO. Cells were demultiplexed and classified into singlets, multiplets, and negatives based on the above results.

6-Plex human-mouse species-mixing experiment analysis

Transcriptome and SBO data processing were performed as described above. We obtained 2759 of cell barcodes after filtering out cells with less than 500 transcripts. After the SBO matrix normalization and classification, we classified singlets as positive for one of SBOs, multiplets as positive for more than one SBO, and negatives as positive for none of SBOs. For species-mixing plots in Fig. 1D and fig. S4, only singlets and doublets of the two specified SBOs were used.

Pseudotime analysis

For pseudotime analysis of 5-plex time-course experiment, we applied the R package “Monocle 2” (23). After removing multiplets and negatives, samples were demultiplexed, quality-controlled, and analyzed. A single-cell trajectory was constructed by Discriminative Dimensionality Reduction with Trees (DDRTree) (24) algorithm using genes differentially expressed at different time points. Cells were ordered across the trajectory by setting the state containing 0-hour sample as a time zero, and pseudotime was calculated. To identify DEGs over pseudotime, a likelihood ratio test in the negative binomial model was performed and genes with a q value less than 0.01 were selected as DEGs. When drawing the heatmap, genes were clustered by their pseudotime expression patterns. Differential expression analysis between two transition states in branch 1 was performed using BEAM function in Monocle package.

48-Plex drug screening data analysis

Following the alignment of sequencing reads, downstream analysis of the 48-plex drug screening experiment was performed using the R package “Seurat” (25). After demultiplexing and removing multiplets and negatives, cells were quality-controlled on the basis of the mitochondrial reads fraction, number of UMI, and number of genes. We identified 3091 cells in which at least 500 transcripts and 300 genes were detected. RNA expression matrix was log-normalized and processed for the further analysis. To cluster the single cells, we ran principal components analysis (PCA) using the expression matrix of variable genes and then performed t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) using the first six PCA components. We identified six clusters using FindClusters function in Seurat with resolution = 0.6. We assigned cell cycle phase scores using cell cycle markers (26) and classified each cell to G2-M, S, or G1 phase. To draw a hierarchical clustered heatmap, we first identified DEGs for each drug with adjusted P < 0.05 by Wilcoxon rank-sum test and obtained 469 responsive genes by merging the DEGs altogether. Expression levels of each drug for the responsive genes were normalized, averaged, and scaled and were used for drawing the heatmap. To construct the dendrogram at the heatmap, hierarchical clustering was performed on the basis of correlations among the expression levels across drugs. Normalized and scaled gene expression data were used in the heatmap. To identify DEGs in Fig. 2D and fig. S7, we performed likelihood ratio test between single cells in each drug and single cells in DMSO controls. To analyze samples by their protein targets, 14 drugs were classified into three groups (BCR-ABL inhibitors, MEK inhibitors, and mTOR inhibitors). Differential expression analysis between cells in each group and cells in DMSO controls was performed as described above. The analysis of drug screening experiment of A375 was performed in the same manner as K562.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank W. Namkung (Department of Pharmacy, Yonsei University) for contributing the kinase inhibitor library (catalog no. L1200, Selleck Chemicals). Funding: This work was supported by the following sources: (i) the Mid-career Researcher Program (NRF-2018R1A2A1A05079172) through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT and Future Planning; (ii) the Bio & Medical Technology Development Program of the National Research Foundation (NRF) funded by the Korean government (MSIT; NRF-2016M3A9B6948494); (iii) the Bio & Medical Technology Development Program of the National Research Foundation (NRF) funded by the Korean government (MSIT; NRF-2018M3A9H3024850); and (iv) by the Ministry of Science, ICT and Future Planning (grant no. NRF-2018R1A2B2001322). Author contributions: D.S., W.L., J.H.L., and D.B. developed the concepts and designed the study. D.S. and W.L. performed the experiments. D.S. performed bioinformatic analysis and analyzed the data. D.S. and W.L. wrote the manuscript with feedback from all authors. J.H.L. and D.B. supervised the project. Competing interests: D.B., W.L., and D.S. are inventors on a provisional patent application with Yonsei University Industry-Academic Cooperation Foundation (no. 10-2018-0075669, filed on 29 June 2018). The authors declare no other competing interests. Data and materials availability: Full sequencing data were deposited in the Sequence Reads Archive (PRJNA493658). All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article. Additional data related to this paper will be provided by the corresponding authors upon request.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/5/5/eaav2249/DC1

Fig. S1. Schematic figure of transient transfection using SBO.

Fig. S2. Additional data for the species-mixing experiment.

Fig. S3. SBO barcoding in heterogeneous cell samples and the effect of transient transfection.

Fig. S4. Correlation heatmap of average gene expression across the drugs.

Fig. S5. Volcano plots showing DEGs for each drug.

Fig. S6. Cell cycle analysis and t-SNE at a single-cell resolution.

Fig. S7. Expression heatmap for A375 drug screening experiment.

Fig. S8. Comparison between previous methods and our method.

Fig. S9. Cell numbers and sequencing depth for each experiment.

Table S1. Oligos and drugs used in the drug screening experiment.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Shalek A. K., Satija R., Adiconis X., Gertner R. S., Gaublomme J. T., Raychowdhury R., Schwartz S., Yosef N., Malboeuf C., Lu D., Trombetta J. J., Gennert D., Gnirke A., Goren A., Hacohen N., Levin J. Z., Park H., Regev A., Single-cell transcriptomics reveals bimodality in expression and splicing in immune cells. Nature 498, 236–240 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tang F., Lao K., Surani M. A., Development and applications of single-cell transcriptome analysis. Nat. Methods 8, S6–S11 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deng Q., Ramsköld D., Reinius B., Sandberg R., Single-cell RNA-seq reveals dynamic, random monoallelic gene expression in mammalian cells. Science 343, 193–196 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Macosko E. Z., Basu A., Satija R., Nemesh J., Shekhar K., Goldman M., Tirosh I., Bialas A. R., Kamitaki N., Martersteck E. M., Trombetta J. J., Weitz D. A., Sanes J. R., Shalek A. K., Regev A., McCarroll S. A., Highly parallel genome-wide expression profiling of individual cells using nanoliter droplets. Cell 161, 1202–1214 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klein A. M., Mazutis L., Akartuna I., Tallapragada N., Veres A., Li V., Peshkin L., Weitz D. A., Kirschner M. W., Droplet barcoding for single-cell transcriptomics applied to embryonic stem cells. Cell 161, 1187–1201 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zheng G. X. Y., Terry J. M., Belgrader P., Ryvkin P., Bent Z. W., Wilson R., Ziraldo S. B., Wheeler T. D., McDermott G. P., Zhu J., Gregory M. T., Shuga J., Montesclaros L., Underwood J. G., Masquelier D. A., Nishimura S. Y., Schnall-Levin M., Wyatt P. W., Hindson C. M., Bharadwaj R., Wong A., Ness K. D., Beppu L. W., Deeg H. J., McFarland C., Loeb K. R., Valente W. J., Ericson N. G., Stevens E. A., Radich J. P., Mikkelsen T. S., Hindson B. J., Bielas J. H., Massively parallel digital transcriptional profiling of single cells. Nat. Commun. 8, 14049 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hicks S. C., Townes F. W., Teng M., Irizarry R. A., Missing data and technical variability in single-cell RNA-sequencing experiments. Biostatistics 19, 562–578 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kang H. M., Subramaniam M., Targ S., Nguyen M., Maliskova L., McCarthy E., Wan E., Wong S., Byrnes L., Lanata C. M., Gate R. E., Mostafavi S., Marson A., Zaitlen N., Criswell L. A., Ye C. J., Multiplexed droplet single-cell RNA-sequencing using natural genetic variation. Nat. Biotechnol. 36, 89–94 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hughes T. R., Marton M. J., Jones A. R., Roberts C. J., Stoughton R., Armour C. D., Bennett H. A., Coffey E., Dai H., He Y. D., Kidd M. J., King A. M., Meyer M. R., Slade D., Lum P. Y., Stepaniants S. B., Shoemaker D. D., Gachotte D., Chakraburtty K., Simon J., Bard M., Friend S. H., Functional discovery via a compendium of expression profiles. Cell 102, 109–126 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Middleton F. A., Mirnics K., Pierri J. N., Lewis D. A., Levitt P., Gene expression profiling reveals alterations of specific metabolic pathways in schizophrenia. J. Neurosci. 22, 2718–2729 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang Y., de Reyniès A., de Leval L., Ghazi B., Martin-Garcia N., Travert M., Bosq J., Brière J., Petit B., Thomas E., Coppo P., Marafioti T., Emile J.-F., Delfau-Larue M.-H., Schmitt C., Gaulard P., Gene expression profiling identifies emerging oncogenic pathways operating in extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type. Blood 115, 1226–1237 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lamb J., Crawford E. D., Peck D., Modell J. W., Blat I. C., Wrobel M. J., Lerner J., Brunet J.-P., Subramanian A., Ross K. N., Reich M., Hieronymus H., Wei G., Armstrong S. A., Haggarty S. J., Clemons P. A., Wei R., Carr S. A., Lander E. S., Golub T. R., The Connectivity Map: Using gene-expression signatures to connect small molecules, genes, and disease. Science 313, 1929–1935 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Subramanian A., Narayan R., Corsello S. M., Peck D. D., Natoli T. E., Lu X., Gould J., Davis J. F., Tubelli A. A., Asiedu J. K., Lahr D. L., Hirschman J. E., Liu Z., Donahue M., Julian B., Khan M., Wadden D., Smith I. C., Lam D., Liberzon A., Toder C., Bagul M., Orzechowski M., Enache O. M., Piccioni F., Johnson S. A., Lyons N. J., Berger A. H., Shamji A. F., Brooks A. N., Vrcic A., Flynn C., Rosains J., Takeda D. Y., Hu R., Davison D., Lamb J., Ardlie K., Hogstrom L., Greenside P., Gray N. S., Clemons P. A., Silver S., Wu X., Zhao W.-N., Read-Button W., Wu X., Haggarty S. J., Ronco L. V., Boehm J. S., Schreiber S. L., Doench J. G., Bittker J. A., Root D. E., Wong B., Golub T. R., A next generation connectivity map: L1000 platform and the first 1,000,000 profiles. Cell 171, 1437–1452.e17 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Melo J. V., The diversity of BCR-ABL fusion proteins and their relationship to leukemia phenotype. Blood 88, 2375–2384 (1996). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mahon F. X., Deininger M. W. N., Schultheis B., Chabrol J., Reiffers J., Goldman J. M., Melo J. V., Selection and characterization of BCR-ABL positive cell lines with differential sensitivity to the tyrosine kinase inhibitor STI571: Diverse mechanisms of resistance. Blood 96, 1070–1079 (2000). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Espadinha A.-S., Prouzet-Mauléon V., Claverol S., Lagarde V., Bonneu M., Mahon F.-X., Cardinaud B., A tyrosine kinase-STAT5-miR21-PDCD4 regulatory axis in chronic and acute myeloid leukemia cells. Oncotarget 8, 76174–76188 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xiong L., Zhang J., Yuan B., Dong X., Jiang X., Wang Y., Global proteome quantification for discovering imatinib-induced perturbation of multiple biological pathways in K562 human chronic myeloid leukemia cells. J. Proteome Res. 9, 6007–6015 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gambacorti-Passerini C., le Coutre P., Mologni L., Fanelli M., Bertazzoli C., Marchesi E., Di Nicola M., Biondi A., Corneo G. M., Belotti D., Pogliani E., Lydon N. B., Inhibition of the ABL kinase activity blocks the proliferation of BCR/ABL+ leukemic cells and induces apoptosis. Blood Cells Mol. Dis. 23, 380–394 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davies H., Bignell G. R., Cox C., Stephens P., Edkins S., Clegg S., Teague J., Woffendin H., Garnett M. J., Bottomley W., Davis N., Dicks E., Ewing R., Floyd Y., Gray K., Hall S., Hawes R., Hughes J., Kosmidou V., Menzies A., Mould C., Parker A., Stevens C., Watt S., Hooper S., Wilson R., Jayatilake H., Gusterson B. A., Cooper C., Shipley J., Hargrave D., Pritchard-Jones K., Maitland N., Chenevix-Trench G., Riggins G. J., Bigner D. D., Palmieri G., Cossu A., Flanagan A., Nicholson A., Ho J. W. C., Leung S. Y., Yuen S. T., Weber B. L., Seigler H. F., Darrow T. L., Paterson H., Marais R., Marshall C. J., Wooster R., Stratton M. R., Futreal P. A., Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer. Nature 417, 949–954 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stoeckius M., Zheng S., Houck-Loomis B., Hao S., Yeung B. Z., Mauck W. M. III, Smibert P., Satija R., Cell hashing with barcoded antibodies enables multiplexing and doublet detection for single cell genomics. Genome Biol. 19, 224 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rohland N., Reich D., Cost-effective, high-throughput DNA sequencing libraries for multiplexed target capture. Genome Res. 22, 939–946 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aitchison J., Measures of location of compositional data sets. Math. Geol. 21, 787–790 (1989). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trapnell C., Cacchiarelli D., Grimsby J., Pokharel P., Li S., Morse M., Lennon N. J., Livak K. J., Mikkelsen T. S., Rinn J. L., The dynamics and regulators of cell fate decisions are revealed by pseudotemporal ordering of single cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 32, 381–386 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Q. Mao, L. Wang, S. Goodison, Y. Sun, paper presented at the Proceedings of the 21th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Sydney, NSW, Australia, 10 to 13 August 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Satija R., Farrell J. A., Gennert D., Schier A. F., Regev A., Spatial reconstruction of single-cell gene expression data. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 495–502 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tirosh I., Izar B., Prakadan S. M., Wadsworth M. H. II, Treacy D., Trombetta J. J., Rotem A., Rodman C., Lian C., Murphy G., Fallahi-Sichani M., Dutton-Regester K., Lin J.-R., Cohen O., Shah P., Lu D., Genshaft A. S., Hughes T. K., Ziegler C. G. K., Kazer S. W., Gaillard A., Kolb K. E., Villani A.-C., Johannessen C. M., Andreev A. Y., Van Allen E. M., Bertagnolli M., Sorger P. K., Sullivan R. J., Flaherty K. T., Frederick D. T., Jané-Valbuena J., Yoon C. H., Rozenblatt-Rosen O., Shalek A. K., Regev A., Garraway L. A., Dissecting the multicellular ecosystem of metastatic melanoma by single-cell RNA-seq. Science 352, 189–196 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/5/5/eaav2249/DC1

Fig. S1. Schematic figure of transient transfection using SBO.

Fig. S2. Additional data for the species-mixing experiment.

Fig. S3. SBO barcoding in heterogeneous cell samples and the effect of transient transfection.

Fig. S4. Correlation heatmap of average gene expression across the drugs.

Fig. S5. Volcano plots showing DEGs for each drug.

Fig. S6. Cell cycle analysis and t-SNE at a single-cell resolution.

Fig. S7. Expression heatmap for A375 drug screening experiment.

Fig. S8. Comparison between previous methods and our method.

Fig. S9. Cell numbers and sequencing depth for each experiment.

Table S1. Oligos and drugs used in the drug screening experiment.