Abstract

In the context of NHS workforce shortages, providers are increasingly looking to new models of care, diversifying the workforce and introducing new roles such as physician associates (PAs) into clinical teams. The current study used qualitative methods to investigate how PAs are integrated into a workforce in a region largely unfamiliar with the profession. We conducted an observational study examining factors that facilitated and challenged PA integration.

Findings suggest that the factors influencing PA integration relate to attributes of the individual, interpersonal relationships and organisational elements. From these, five key considerations have been derived which may aid organisations when planning to integrate new roles into the clinical workforce: prior to introducing PAs organisations should consider how to fully inform current staff about the PA profession; how to define the role of the PA within teams including clinical supervision arrangements; investment in educational and career development support for PAs; communication of remuneration to existing staff and conveying an organisational vision of PAs within the future workforce. Through consideration of these areas, organisations can facilitate role integration, maximising the potential of the workforce to contribute to sustainable healthcare provision.

KEYWORDS: Physician associate, workforce

Introduction

The shortage of qualified staff is widely recognised as the most significant issue facing the NHS today.1,2 Various approaches to addressing the workforce gap have been proposed and any comprehensive solution is likely to combine several strategies including improving retention, incentivising training into existing roles, maximising the efficiency of current staff and creating new roles to expand the workforce.1

The UK is not unique in facing healthcare workforce challenges. A variety of approaches have been taken worldwide with many countries embracing non-medical generalist roles to support care delivery as part of a multi-disciplinary team.3 Physician associates (PAs; known as physician assistants in many countries) have gained prominence as one of these new roles that may help to address the workforce gap.4,5 Physician associates are defined as ‘healthcare professionals with a generalist medical education who work alongside doctors, physicians, GPs and surgeons to provide medical care as an integral part of the multidisciplinary team’.6 Within the US they are well established with a workforce of over 100,000 PAs working across a range of specialties and providers.7,8

The Department of Health has invested in developing the PA profession to help to address NHS workforce deficits and it was projected that 38 PA training courses will be running across the UK by the end of 2018.4,9 Although already embedded in some regions of the country, much of the UK has, until recently, had no local PA graduates and therefore NHS providers in most areas have little experience of training and employing qualified PAs.10 This lack of experience of working with an entire profession presents unique challenges which have not been faced by the NHS at such scale in recent times.11 Furthermore, experience from other countries suggests that integration of newly qualified PAs (NQPAs) poses a number of challenges, many of which are related to the context and structure of individual healthcare systems.12 Research into the integration of new groups such as advanced practitioners into existing healthcare teams also reveals a multifaceted process involving issues of role definition and identity at an individual and team level.13–16 As such, the factors that influence integration of NQPAs in the UK are likely to be multiple and complex. Achieving a better understanding of these issues will allow us to maximise the future potential of this workforce.17

The work presented here is part of a wider exploratory study into the work of NQPAs. This paper specifically defines and explores the factors that impact role integration, aiming to describe how healthcare providers can positively influence the integration of NQPAs into clinical teams.

Methods

Study design

This exploratory study was conducted using mixed methods based on a constructivist approach. Study design was informed by the principles of grounded theory with no a priori assumption of themes.18 The process was iterative with themes emerging and evolving from data throughout the course of the study informing the process of data collection. Data collection was deemed complete when data saturation was achieved.

Setting

The study was carried out across five hospital sites affiliated to one of two acute NHS hospital trusts in a region that has traditionally employed very few PAs. All sites were planning to employ NQPAs during the study period in the context of a recent expansion in student PA numbers within the region.

Participants

Participants were identified by the nature of their role and employer. All PAs working at the five sites were invited to participate in a focus group or an interview (18 NQPAs and two established PAs).

Consultants, junior doctors and senior nurses were identified by virtue of their role in departments planning to employ an NQPA. They were invited via email to participate in an initial survey. In total 197 survey invitations were sent according to purposive maximum variation sampling, aiming to involve co-workers across a breadth of specialties working with different PAs. Participants indicating further interest when completing the survey, were invited to focus groups. In addition, an email was sent to all junior doctors at each trust inviting them to participate in focus groups. Those responding to this email were also invited to participate in focus groups.

Data collection

Fieldwork

Initial fieldwork was collected from written notes and discussion with stakeholders from organisations planning NQPA roles, PA educators, and individuals with leadership roles in workforce development. Observations of workplace environment and organisational structures were recorded throughout the study.

Surveys

A survey was developed based on initial fieldwork and was disseminated 2–4 weeks prior to the NQPAs starting, gathering understanding of the expectations of NQPAs and their role.

Focus groups and interviews

Focus groups and interviews were held in the workplace between 2 and 6 months from the start of the PA employment and lasted 30–60 minutes. These were audio recorded with transcription verbatim and immediately analysed. Focus groups were the preferred data collection tool as group interaction was utilised to enrich discussion and data acquisition. Interviews were held when participants could not attend focus groups. Both focus group and interviews were semi-structured using an iteratively developing topic guide in keeping with the principles of grounded theory.18 One clinical researcher (Sam Roberts (SR)) facilitated all focus groups and interviews with field notes kept by another (Sarah Howarth (SH)) in the two larger focus groups. Participant structure is outlined in Table 1.

Table 1.

Focus group and interview participants

| Method | Participants | Female (n) | Participant Base Site |

|---|---|---|---|

| Focus group 1 | 8 PAs | 6 | Hospital 1 and 2 |

| Focus group 2 | 6 PAs | 5 | Hospital 3 and 4 |

| Focus group 3 | 3 CTs, 1 Senior nurse | 4 | Hospital 3 |

| Focus group 4 | 3 FTs, 1 ST | 3 | Hospital 4 |

| Focus group 5 | 2 Consultant supervisors | 1 | Hospital 1 |

| Focus group 6 | 2 FTs, 1 CT, 1 ST | 3 | Hospital 1 and 2 |

| Interview 1 | Consultant supervisor | 1 | Hospital 1 and 2 |

| Interview 2 | Consultant | 1 | Hospital 1 |

| Interview 3 | Consultant | 0 | Hospital 5 |

| Interview 4 | Consultant supervisor | 1 | Hospital 5 |

| Interview 5 | PA | 1 | Hospital 1 |

| Interview 6 | PA | 1 | Hospital 3 |

| Interview 7 | Consultant supervisor | 1 | Hospital 3 |

| Interview 8 | Senior nurse | 1 | Hospital 5 |

CT = core trainee doctor; FT = foundation year doctor; PA = physician associate; ST = specialty trainee doctor

Quotes are tagged with the participant's role (consultant, senior nurse, foundation year doctor (FT), core trainee doctor (CT), specialty trainee doctor (ST) or PA) followed by a numerical indicator.

Data analysis

This paper reports only on the results of the fieldwork, interviews and focus groups as survey data is to be explored elsewhere.

Data analysis was performed based on the thematic analysis approach described by Braun and Clarke.19 A qualitative data analysis tool was used to assist this process (NVIVO version 11 QSR International (UK) Ltd). After completion of the initial thematic analysis, themes were explored, compared and contrasted independently by three investigators (SH, Helen Millott (HM) and SR) following which these were discussed and adapted. This process continued until investigators were satisfied that the themes obtained reflected participant experiences.

Ethics

Ethical approval was granted by the University of Leeds School of Medicine Research and Ethics Committee (MREC17-001). Research was conducted in line with the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research.20

Results

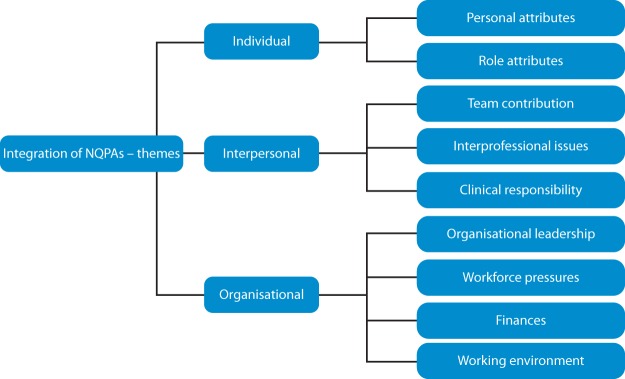

Three key groups of themes influencing the integration of NQPAs were identified (Fig 1). Based on these, the processes that influenced integration are explored.

Fig 1.

Initial thematic analysis results – factors influencing physician associate integration.

Individual themes included both personal and role related issues. The attributes of the NQPA as an individual including their training, ability and attitude were identified as promoting integration. The PA role itself was viewed positively in terms of potential for future development and flexibility however a number of issues were raised around role uncertainty and professional limitations.

Interpersonal themes were powerful, describing how NQPAs contributed to clinical teams and also highlighting interprofessional issues raised by the presence of PAs. Most participants reported positive experiences of the way in which individual NQPAs worked within teams although role restrictions were seen prevent maximisation of potential contributions. Interprofessional issues raised by the presence of PAs included salary, blurred professional boundaries and access to training opportunities across all professions. These emerged as potential barriers to integration. Uncertainty around responsibility for clinical supervision of NQPAs was identified as a specific theme potentially limiting integration.

Organisational themes exerted a strong influence over integration. The perception of participants regarding organisational investment in the PA role had a significant bearing on integration. Working environment, particularly rota patterns and job plan emerged as a distinct theme impacting integration. External pressures such as workforce shortages and funding were also considered as organisational themes influencing PA integration both positively and negatively.

Informing the existing workforce about PAs

Participants reported that a lack of understanding about the abilities and training of NQPAs was a barrier to their integration. Although trained in medicines management and patient investigation, UK PAs are currently unable to prescribe or request ionising radiation.6 PAs identified that a lack of information about their role and their limitations influenced the way they were treated; PA (5):

When I introduced myself on my first day on the ward, one of the nurses was like, ‘Oh, what can you do then?’ and so I explained and I said, ‘I can’t prescribe though,’ and she just turned around and she was like, ‘Well that's what I need you for, what good are you if you don’t do that?’

and ST (1):

Nobody really knows what training they’ve had and what level we should be expecting them to really work at.

The impact of practical strategies to address role limitations were described, for example, consultants requesting radiological investigations on the ward round rather than delegating this task, or interprofessional working with prescribing pharmacists; FT (4):

If they’ve gone around with a consultant, that consultant should be putting the drugs on the drug chart.

NQPAs identified the positive impact of organisational efforts to inform colleagues about PA training and abilities; PA (5):

I think there's been a lot of education prior to us joining which has helped and although not everybody knows what we can do, people are willing to ask questions.

Defining an initial role and arrangements for clinical supervision

Participants indicated that in some cases the role of the PA was poorly defined resulting in uncertainty about how they integrated into existing teams; PA (13):

I think the challenge has been still not knowing where I fit. I don’t have a definitive job plan.

Many participants, particularly junior doctors reported uncertainty about responsibility for supervising NQPAs potentially inhibiting collaborative working; CT (4):

With the physician associates, you don’t know if you should be making decisions for them. Is that my responsibility? If I say yes to something that they do, and that wasn’t right, then was that my fault?

Consultants were often better able to explicitly define roles and responsibilities. In terms of clinical supervision, many drew analogies with other groups such as junior doctors; consultant (5):

No matter what happened with any of our trainees or juniors, of course, the responsibility lies with the consultant always.

Where specific roles had been defined, it was clear that NQPAs were integrating as a valued member of the team; CT (3):

In terms of helping the ward and the ward round run smoothly it's fantastic because there's an extra pair of hands to prep notes, to write down plans … which is always going to be helpful because it means you get stuff done quicker and you can do other things.

Planning continuing professional development and career development support

PAs are expected to record lifelong continuing professional development (CPD) and undertake workplace based assessments during their first year post qualification.6,21 In some cases, NQPAs perceived a lack of opportunity for CPD; PA (9):

I don’t know if it would be possible now that we’re working and everything but I’d still quite like a bit of training every now and again.

Many participants identified the key role of dedicated supervisors in promoting integration, particularly in acting as an advocate, facilitating training and planning career development.21 Responses implicitly aligned this role to educational supervision of doctors. However, most dedicated supervisors reported being unprepared for supervising PAs; consultant (4):

I certainly feel there wasn’t a huge amount of information about what they could and couldn’t do and what their expectations were going to be. I’m still not quite sure that we are meeting or will continue to meet their expectations or how we need to achieve that.

NQPAs recognised the value of training and saw this as a facilitator to integration where it was provided for them, relating formal training provision to a sense of organisational investment in their role; PA (12):

There's quite a lot of training … yeah, they’ve been lovely with teaching.

Positive experiences were reported by both NQPAs and supervisors where career planning was co-defined. Many saw the lack of formal career progression framework as an opportunity rather than a barrier; consultant (1):

You can get them in the right mould which we are liking … all your training, and once they know the system, they stick to the system and I find that's a very good thing.

and PA (2):

There are a lot of avenues that you can take with the role, you’re not limited to a training pathway so you can gain experience in lots of different areas if you want to.

Considering and communicating remuneration decisions

The basic pay for most PAs in the UK is more than that of a nurse or a doctor at the point of qualification.6,22,23 This was identified as a point of contention which risked becoming a barrier to integration; PA (9):

I’ve had quite a few times when people have brought up salary so I’ve tried to just avoid it. I don’t know, I find it a bit awkward because it's not down to us how much we get paid.

Although this was an issue beyond the scope of individual organisations to directly address, participants reported examples of this being considered in ways that did not adversely impact integration; senior nurse (2):

I don’t necessarily deem that the banding for the PA is wrong, it's just that the way that the banding is done for the nurses is not right.

Providing organisational leadership and vision

All participants discussed an awareness of the organisational investment in employing NQPAs and the impact of this; consultant (6):

I think it was [Clinical Director] who seemed to have the overall lead, but I haven’t heard a word. [Senior Clinical Director] sends an email about them [PAs] but doesn’t even mention us. … I have to say, trust support has been zero.

In other cases, clinical leaders had been identified as PA champions, promoting the role within the organisation and encouraging colleague engagement. This resulted in positive outcomes; PA (5):

I think from the very start of us starting here, the consultants and the [clinical] lead they were very supportive and they were aware of the things that were going through our mind and trying to reassure us.

Discussion

We identified a number of challenges to incorporating NQPAs into the workforce and described the practical measures found to facilitate role integration to the benefit of new and existing team members alike.

These findings emphasise that preparation of the existing workforce prior to NQPAs starting is vital. Access to information about the PA role, limitations and supervision arrangements along with communication of a positive organisational vision of the role was reported to facilitate integration. Whilst these considerations may appear self-evident, a number of participants described examples of negative impact when existing staff were not prepared for working with NQPAs. Lack of information about new roles is known to be detrimental to teams and individuals, with negative emotional responses emerging when a lack of recognition is perceived as devaluing individual contributions, potentially resulting in a feeling of isolation.15,24 Leading on from this concept, role clarity is associated with staff retention therefore investing in informing staff about PAs is of benefit to employers and healthcare teams alike.25 We observed a number of communication platforms used to disseminate information about PAs including departmental meetings, trust wide meetings, email newsletters, trust-wide screensavers and distribution of written information.26 We would suggest that other organisations consider these methods and more when planning to introduce new roles into teams.

It is also clear that recognising and planning CPD and career progression positively impacted the experience of NQPAs and their colleagues. In order to achieve this, organisations needed to plan both the formal training opportunities for NQPAs and also the dedicated supervisor role. Participants reported a mixture of formal training opportunities available including multi-professional departmental teaching, foundation doctor training and dedicated PA educational programmes. All PAs in this study had a dedicated supervisor who was a consultant with experience of supervising doctors. PAs on the whole found that the relationship with their dedicated supervisor was valuable. Some reported that this relationship was of increased importance given the lack of formal career progression pathway. In the absence of an external structure, career progression was co-defined between the NQPA and the supervisor. However, very few dedicated supervisors had prior experience of working with PAs and this was repeatedly highlighted as a challenge. Defining a vision of career development for the PA profession has been identified elsewhere as a barrier to integration into the workforce.27 The PA role is relatively unique in that the career progression is conceptualized as being horizontal as opposed to the traditional model of vertical career progression seen in medicine.8 Whilst this is seen by many as a positive attribute affording flexibility to the role, it conflicts with traditional training models and as such creates a barrier to initial integration, particularly for supervisors used to vertical career progression. Organisations planning NQPA roles need to prepare dedicated supervisors for this tension. Since the completion of the study, formal regional training for NQPA supervisors has been implemented. We would encourage any organisation planning to integrate new roles into the workforce to consider supervisor development needs.

Internationally, PAs are making a valuable contribution to the global healthcare workforce, particularly in underserved areas and specialties, increasing access to medical services.28,29 The PA role in the UK has been repeatedly shown to complement that of doctors and nurses without detracting from either quality or efficiency of care.30–33 The flexibility of the PA role is a key benefit allowing this group to be considered as a potential workforce solution across a range of providers.6,10 With the rapid expansion in UK PA training in the context of a national healthcare workforce shortfall, the impetus is on all healthcare providers to maximise the potential of NQPAs to meet current and future service demands.1,8 Clinical leaders in turn must consider how to integrate new working models and diversified healthcare teams to secure a sustainable workforce.34

We have identified a number of challenges encountered by organisations employing NQPAs and describe the practical measures found to facilitate the integration of NQPAs into healthcare teams. By considering these issues at the time of planning PA roles, healthcare providers can ensure that the PA profession is effectively embedded within their organisation to positively impact patient care in the long term.

References

- 1.There for us. A better future for the NHS workforce. London: NHS Providers, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robertson R, Appleby J, Evans H. Public satisfaction with the NHS and social care in 2017: results and trends from the British Social Attitudes survey. London: Nuffield Trust, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organisation Global strategy on human resources for health: workforce 2030. Geneva: WHO, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 4.General Practice Forward View. NHS England, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ross N, Parle J, Begg P, Kuhns D. The case for the physician assistant. Clin Med 2012;12:200–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Faculty of Physician Associates An employer's guide to physician associates. London: Royal College of Physicians, 2017. www.fparcp.co.uk/employers/guidance. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morgan P, Leach B, Himmerick K, Everett C. Job openings for PAs by specialty. JAAPA 2018;31:45–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aiello M, Roberts KA. Development of the United Kingdom physician associate profession. JAAPA 2017;30:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aiello M, Parle J. Health Education England and UK & Ireland Board of PA Educators: Physician associate training providers - course and incoming student data (January 2018). Health Education England, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ritsema TS. Faculty of Physician Associates census results 2017. London: Royal College of Physicians, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jackson B, Marshall M, Schofield S. Barriers and facilitators to integration of physician associates into the general practice workforce: a grounded theory approach. Br J Gen Pract 2017;67:e785–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ballweg R. Global PA development: Time-consuming, complicated, and worthwhile. JAAPA 2018;31:8–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cummings GG, Fraser K, Tarlier DS. Implementing advanced nurse practitioner roles in acute care: an evaluation of organizational change. J Nurs Adm 2003;33:139–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Webster F, Bremner S, Jackson M, Bansal V, Sale J. The impact of a hospitalist on role boundaries in an orthopedic environment. J Multidiscip Healthc 2012;5:249–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ledger A, Edwards J, Morley M. A change management perspective on the introduction of music therapy to interprofessional teams. J Health Organ Manag 2013;27:714–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.There for us. A better future for the NHS workforce. London: NHS Providers; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holton EF., III New employee development: A review and reconceptualization. Human Resource Development Quarterly 1996;7:233. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Corbin JM, Strauss A. Grounded theory research: Procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qualitative Sociology 1990;13:3–21. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 2006;3:77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 2007;19:349–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Faculty of Physician Associates First year post qualification guidance for physician associates and physician associate employers. London: Royal College of Physicians, 2017. www.fparcp.co.uk/employers/guidance [Accessed 5 May 2018]. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Agenda for change pay scales 2017/18. NHS Employers, 2017. www.nhsemployers.org/your-workforce/pay-and-reward/agenda-for-change/pay-scales/annual [Accessed 5 May 2018]. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Winnard G. Pay and Conditions Circular (M&D) 2/2018. NHS Employers, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Almoayad F, Ledger A. Entering a new profession: Patient educator interns’ struggles for recognition. Journal of Health Specialties 2016;4:262–9. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lyons TF. Role clarity, need for clarity, satisfaction, tension, and withdrawal. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance 1971;6:99–110. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Faculty of Physician Associates Who are physician associates? London: Royal College of Physicians, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 27.van der Biezen M, Derckx E, Wensing M, Laurant M. Factors influencing decision of general practitioners and managers to train and employ a nurse practitioner or physician assistant in primary care: a qualitative study. BMC fam pract 2017;18:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hooker RS. Physician assistants and nurse practitioners: the United States experience. Med J Aust 2006;185:4–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grimes K, Prada G. Value of physician assistants. Ottawa: The Conference Board of Canada, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Drennan VM, Halter M, Joly L, et al. Physician associates and GPs in primary care: a comparison. Br J Gen Pract 2015;65:e344–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Drennan VM, Halter M, Brearley S. et al. Investigating the contribution of physician assistants to primary care in England: a mixed-methods study. Southampton: NIHR Journals Library, 2014. (Health Services and Delivery Research, No. 2.16.). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Halter M, Drennan VM, Joly LM, Gabe J, Gage H, de Lusignan S. Patients’ experiences of consultations with physician associates in primary care in England: A qualitative study. Health Expect 2017;20:1011–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Farmer J, Currie M, West C, Hyman J, Arnott N. Evaluation of physician assistants to NHS Scotland. Inverness: Centre for Rural Health, UHI Milennium Institute, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Health Education England Facing the facts, shaping the future. A draft health and care workforce strategy for England to 2027. London: HEE, 2017. [Google Scholar]